Abstract

Transgenic (Tg) mouse models overexpressing amyloid precursor protein (APP) develop senile plaques similar to those found in Alzheimer's disease in an age-dependent manner. Recent reports demonstrated that immunotherapy is effective at preventing or removing amyloid-β deposits in the mouse models. To characterize the mechanisms involved in clearance, we used antibodies of either IgG1 (10d5) or IgG2b (3d6) applied directly to the brains of 18-month-old Tg2576 or 20-month-old PDAPP mice. Both 10d5 and 3d6 led to clearance of 50% of diffuse amyloid deposits in both animal models within 3 d. Fc receptor-mediated clearance has been shown to be important in an ex vivo assay showing antibody-mediated clearance of plaques by microglia. We now show, using in vivo multiphoton microscopy, that FITC-labeled F(ab′)2 fragments of 3d6 (which lack the Fc region of the antibody) also led to clearance of 45% of the deposits within 3 d, similar to the results obtained with full-length 3d6 antibody. This result suggests that direct disruption of plaques, in addition to Fc-dependent phagocytosis, is involved in the antibody-mediated clearance of amyloid-β deposits in vivo. Dense-core deposits that were not cleared were reduced in size by ∼30% with full-length antibodies and F(ab′)2 fragments 3 d after a topical treatment. Together, these results indicate that clearance of amyloid deposits in vivo may involve, in addition to Fc-dependent clearance, a non-Fc-mediated disruption of plaque structure.

Keywords: amyloid, transgenic, Alzheimer, multiphoton, imaging, senile plaque, microglia, immunotherapy, antibody

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a debilitating neurodegenerative disease characterized by the presence of senile plaques in the brain (Hyman and Trojanowski, 1997; Markesbery, 1997; Powers, 1997). Amyloid-β, a 40–42 amino acid peptide, is the primary component of these plaques, and genetic causes of AD lead to dramatically increased amyloid-β plaque deposition (Selkoe, 1996;Rubinsztein, 1997). Although the exact role of amyloid-β deposits in AD is unknown, senile plaques remain a primary target for drug development aimed at prevention or reversal of the disease. Transgenic (Tg) mouse models overexpressing amyloid precursor protein (APP) develop senile plaques in an age-dependent manner, similar to those found in the human disease (Games et al., 1995; Hsiao et al., 1996). The transgenic mice are valuable as a model system for evaluating therapeutic approaches toward removing or preventing formation of amyloid-β deposits.

Recently, an approach involving immunization of PDAPP mice with amyloid-β was shown to be effective at prevention of plaque deposition (Schenk et al., 1999). In these experiments, a peripheral immune response resulted in an alteration of amyloid-β deposition in the brain. A subsequent report demonstrated that anti-amyloid-β antibodies, given peripherally, were also effective at prevention of amyloid-β deposition in these mice (Bard et al., 2000). This result, using a “passive” immunotherapeutic approach, suggests that an active T-cell-mediated immune response is not necessary for alterations of amyloid-β deposits in the brain. Moreover, we showed recently that a single application of anti-amyloid-β antibodies to the surface of the brain in these mice led to clearance of existing senile plaques in the remarkably short time frame of 3–8 d (Bacskai et al., 2001). Together, these results demonstrated that immunotherapy prevents formation of new plaques in PDAPP mice and can lead to their clearance. The mechanism of this antibody-mediated clearance of plaques appears to be mediated, at least in part, by Fc receptor-mediated phagocytosis; however, additional mechanisms might also be involved.

Specifically, ex vivo experiments demonstrated that Fc receptor-mediated phagocytosis is at least one mechanism involved in removing the amyloid-β in the brain (Bard et al., 2000). F(ab′)2 fragments were unable to stimulate microglial cells, and the process was blocked by anti-Fc receptor antibodies, demonstrating that clearance was mediated by Fc. The close association of microglial cells with dense-core plaques, as well as results showing activation of these cells after topical antibody treatment (Bacskai et al., 2001), supports this idea. Similarly, a recent report in double transgenics expressing APP and TGF-β demonstrated clearance of amyloid-β deposits via upregulation of microglia (Wyss-Coray et al., 2001). Together, clearance of amyloid-β deposits by an Fc-mediated mechanism involving active cellular removal seems likely. On the other hand, in vitro experiments have shown that antibodies binding to amyloid-β deposits may disrupt β-pleated sheet conformation and lead to plaque disaggregation directly (Solomon et al., 1997). Finally, an additional possibility for plaque clearance involves activation of complement systems that could enhance degradation or clearance. Our current experiments used anin vivo approach to examine these possible mechanisms.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal preparation. Eighteen-month-old Tg2576 mice (Hsiao et al., 1996) or 20-month-old homozygous PDAPP mice (Games et al., 1995) were used for in vivo imaging, as described previously (Bacskai et al., 2001). Briefly, the animals were anesthetized with avertin (1.3% tribromoethanol and 0.8% tert-pentylalcohol in distilled water; 250 mg/kg, i.p.). and immobilized in custom-built stage-mounted ear bars and a nosepiece, similar to a stereotaxic apparatus. A 2–3 cm incision was made between the ears, and the scalp was reflected to expose the skull. Four circular craniotomies (∼1–1.2 mm in diameter; on either side of sagittal suture and just posterior to coronal suture) were made using a high-speed drill (Fine Science Tools, Foster City, CA) and a dissecting microscope (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) for gross visualization. Heat and vibration artifacts were minimized during drilling by frequent application of artificial CSF (ACSF) (in mm: 125 NaCl, 26 NaHCO3, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 2.5 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 1 CaCl2, and 25 glucose). The dura was carefully removed from each site with fine forceps. An ACSF reservoir was created within the opened scalp over the open skull preparations to accommodate the long working distance, water immersion dipping objectives (Olympus Optical, Tokyo, Japan) of anOlympus Optical BX-50 microscope. Texas Red dextran [0.05 ml; 35 mg/ml; 70,000 molecular weight (MW); Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR] was injected into a lateral tail vein to create a fluorescent angiogram used to facilitate image alignment from session to session. Thioflavin S (thioS) (0.005% in ACSF; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and 8 μl of 1 mg/ml fluorescein-labeled antibody was then applied to the surface of the brain for 20 min. Sites were washed with ACSF and imaged. After imaging, the animals were sutured and allowed to recover. Three days later, the animals were reanesthetized and prepared for imaging. Thioflavin S and Texas Red dextran were reapplied. A different, noncompeting labeled antibody was used in the second imaging session to ensure that the original epitopes of amyloid-β were not simply masked at the second session.

In vivo imaging. Two-photon fluorescence was generated with 750 nm excitation from a mode-locked Ti:Sapphire laser Tsunami (Spectra-Physics, Mountain View, CA), mounted on a commercially available multiphoton imaging system (Bio-Rad 1024ES; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Custom-built external detectors containing three photomultiplier tubes (Hamamatsu Photonics, Bridgewater, NJ) collected emitted light in the range of 380–480, 500–540, and 560–650 nm. Thioflavin S, FITC-labeled antibody, and Texas Red angiograms were separated spectrally into the three imaging channels. At the end of the experiment, the animal was killed, and the brain fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde.

Image analysis. Three-dimensional imaging volumes were analyzed using custom macros written for Scion Image (Scion, Frederick, MD) or rendered in three-dimension using Voxblast (VayTek, Fairfield, IA). Stacks of two-dimensional images were projected using maximal intensity and aligned from one imaging session to another using blood vessels as independent fiduciary markers. Thioflavin S-positive plaques were measured as described previously (Christie et al., 2001). Local image quality was assessed using the angiogram fluorescence as a positive control. A threshold was applied to the images, and diameters were obtained from the maximal cross-section of each plaque. Plaques were identified by thioflavine S staining and morphological appearance. Ambiguous deposits <5 μm in diameter were not counted. This technique allowed us to determine whether the thioflavine S deposit present in the original imaging session was cleared in the second imaging session. If the plaque was not cleared, the size of the identified plaque before and after treatment was compared. Diffuse deposits were analyzed by measuring antibody-positive, thioflavine S-negative amyloid-β in projections of the three-dimensional imaging volumes from each animal. Clearance was expressed as a percentage of amyloid burden within each site from each animal after 3 d.

RESULTS

Our previous report demonstrated antibody-mediated clearance of existing amyloid-β deposits (Bacskai et al., 2001) in PDAPP transgenic mice, which overexpress a minigene containing the human APPV717F mutation (Games et al., 1995). In vivo imaging of the brain in an intact animal is achieved with multiphoton microscopy, which offers significant advantages over other modes of fluorescence or confocal fluorescence, particularly in thick biological specimens (Denk et al., 1990; Christie et al., 2001). Multiphoton fluorescence microscopy achieves spatial resolution that is comparable with visible light confocal microscopy, i.e., on the order of 1 μm. This resolution is at least two orders of magnitude superior to other imaging modalities, such as magnetic resonance imaging or positron emission tomography scanning (Yang et al., 1998) and allows discrimination of single cells, as well as subcellular structures. This technology permits highly sensitive visualization of microscopic structures deep within biological tissue. Chronic imaging of the live mice with multiphoton microscopy showed that antibody application to the surface of the brain led to clearance of plaques within a few days. To generalize the efficacy of such a treatment in different transgenic mouse models, a similar approach was used in the Tg2576 mouse. This mouse overexpresses the Swedish mutation of the human APP695 gene driven by the hamster prion protein promoter (Hsiao et al., 1996). Mice were surgically prepared as described in Materials and Methods. A craniotomy was performed, and the dura was removed in up to four sites per animal. FITC-labeled antibody (10d5; Elan Pharmaceuticals, South San Francisco, CA) as well as thioS were applied to the exposed brain in ACSF for 20 min and then washed off. Texas red dextran (70,000 MW; Molecular Probes) was injected into a tail vein of each animal to permit simultaneous recording of a fluorescent angiogram. Three-dimensional image volumes of 615 × 615 μm and up to 200 μm deep to the surface of the brain were obtained in each of the cranial sites using a 20× water immersion objective (Olympus Optical; numerical aperture of 0.5). Dense-core plaques were defined as those plaques labeled with thioS (fluorescence in channel 1), whereas the labeled antibody (channel 2) binds to both dense-core and diffuse plaques. Both thioS and antibody label amyloid angiopathy. The angiogram (channel 3) is recorded to facilitate alignment of volumes from sequential imaging sessions within each cranial site, independent of plaque location. Figure 1 illustrates an example of antibody-mediated clearance of existing amyloid deposits in a Tg2576 mouse. The initial imaging session reveals dense-core and diffuse plaques, as well as amyloid angiopathy labeled with the fluorescent antibody. The subsequent imaging session of the same volume of brain obtained 3 d later shows a marked diminution of diffuse deposits. Figure 2 compares the clearance of amyloid deposits with a single 10d5 application at 3 d in Tg2576 and PDAPP mice. This antibody is remarkably effective at mediating removal of plaques in both transgenic mouse models within 3 d. The Tg2576 and PDAPP mouse models differ in their expression of diffuse versus dense-core plaques. The Tg2576 mouse exhibits more frequent and larger dense-core plaques, with comparatively sparse diffuse amyloid deposits. The PDAPP mouse model develops ∼10-fold more diffuse deposits than the Tg2576 mouse at comparable ages. Our imaging approach allows us to measure identified amyloid deposits within the same animal before and after treatment, permitting direct measurement of clearance of existing amyloid deposits regardless of their prevalence. These results demonstrate that clearance is independent of the genetic strain of animal, the specific mutation in the APP gene, or the promoter-driving expression of the transgene. These results are consistent with recent reports using different transgenic mouse models in which immunization with amyloid-β peptides prevented behavioral deficits (Janus et al., 2000; Morgan et al., 2000).

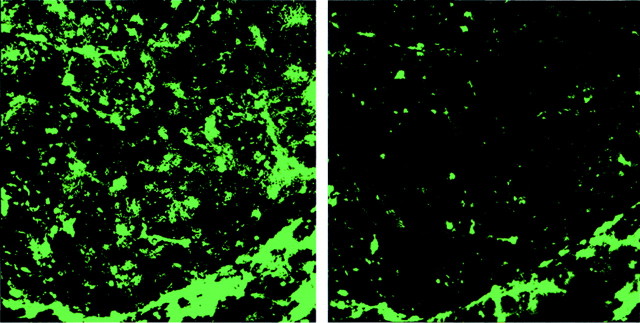

Fig. 1.

Topical antibody application leads to clearance of diffuse amyloid-β in Tg2576 mice. These images are projections of three-dimensional volumes from the cortex of a representative Tg2576 mouse treated with FITC-labeled 10d5 antibody. The images were acquired in the anesthetized mouse using multiphoton microscopy. Theleft shows labeled amyloid deposits at the initial application of antibody. Numerous diffuse deposits as well as amyloid angiopathy can be seen. The right is the same volume 3 d later, labeled with 3d6 antibody, which recognizes amyloid-β independently of 10d5. A majority of the amyloid-β deposits have been cleared in this 3 d period.

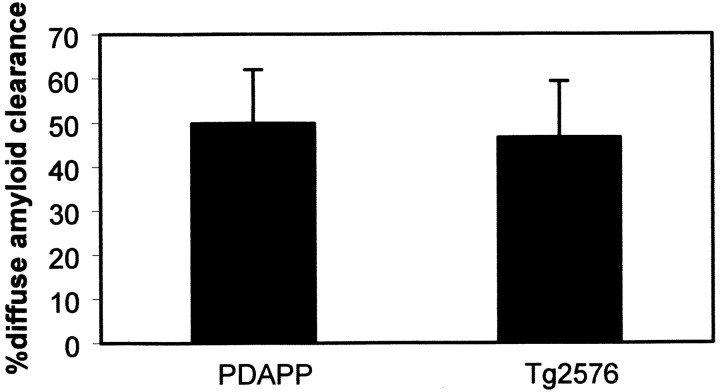

Fig. 2.

10d5 antibody is equally effective at clearing diffuse amyloid-β deposits in both PDAPP and Tg2576 transgenic mouse models. These plots represent the percentage of amyloid clearance in 3 d from paired volumes of cortex within the same animals after 3 d. A single application of antibody to the cortex was given at day 0. Approximately one-half of the diffuse deposits are cleared under these conditions. These results are the means ± SE forn = 9–15 sites from at least three animals in each group. Percentage of clearance ranged from 91.2 to −7.9% in PDAPP mice and 82.9 to 4.5% in Tg2576 mice. Not statistically different; Student's t test.

The determination of clearance of diffuse amyloid deposits in vivo depends on the addition of a second labeled antibody after treatment with the initial labeled antibody. When using 10d5 as the treatment antibody, 3d6 was used to detect remaining amyloid deposits that were not cleared. These antibodies have neighboring epitopes on amyloid-β but do not compete with each other at the concentrations used here, as described by Bacskai et al. (2001) and shown in Figure3. In this experiment, paraformaldehyde-fixed tissue sections were first treated with FITC-labeled 10d5 at 1 mg/ml for 20 min, washed, and then subsequently incubated with rhodamine-labeled 3d6 at 1 mg/ml for 20 min. Confocal microscopy shows that both labeled antibodies are bound to amyloid deposits in these sections, and they colocalize identically. Similar results are obtained in cryostat sections and in vivo.

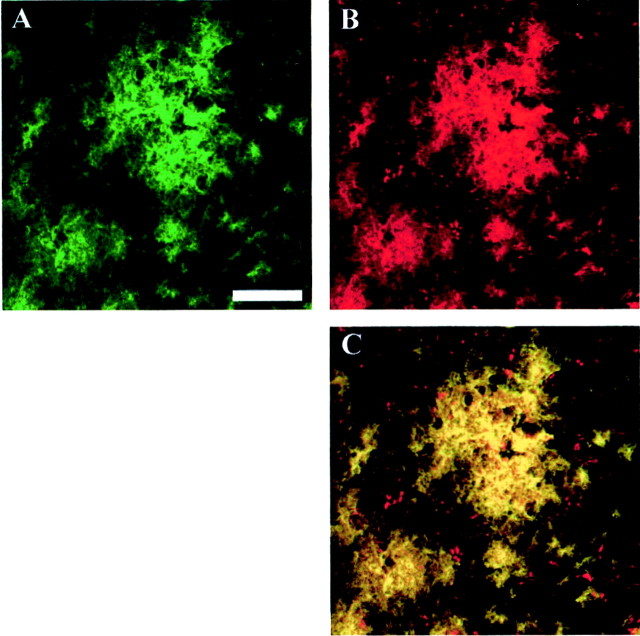

Fig. 3.

10d5 and 3d6 antibodies colocalize at noncompetitive binding sites on amyloid-β plaques. Paraformaldehyde-fixed tissue sections from an 18-month-old Tg2576 mouse brain were treated sequentially with FITC-labeled 10d5 antibodies, followed by rhodamine-labeled 3d6 antibodies. Images were obtained with a Bio-Rad confocal microscope using 488 nm excitation for FITC (A) and 568 nm excitation for rhodamine (B). A color-merged image (C) shows that 10d5 (green) and 3d6 (red) are both able to bind to the plaques and colocalize everywhere, producing a yellow color. Scale bar, 50 μm.

The following experiments were performed to determine whether the mechanism of amyloid-β clearance in vivo was specific to the 10d5 antibody. 3d6 monoclonal antibody, which recognizes amino acids 1–5 of amyloid-β, was compared with 10d5 antibody, which recognizes a close but distinct epitope of amyloid-β, residues 3–6. As can be seen in Figure 4, each of these antibodies was similarly effective after 3 d when applied topically to the PDAPP mouse. Diffuse amyloid burdens were measured in the identical volumes within each site before and after a single treatment. The amyloid burdens were decreased with 10d5 and 3d6 by 50 and 48%, respectively, with each antibody treatment. These results suggest that the mechanism of clearance is not dependent on a single antibody but can be generalized to other antibodies directed toward the N terminus of amyloid-β. Likewise, 10d5 is of the IgG1 isotype, whereas 3d6 is an IgG2b. Therefore, antibody-mediated clearance is not dependent on any one specific IgG subtype. Because IgG1 antibodies do not activate complement in the mouse, this result demonstrates that activation of the complement cascade is not necessary for clearance of amyloid-β in vivo.

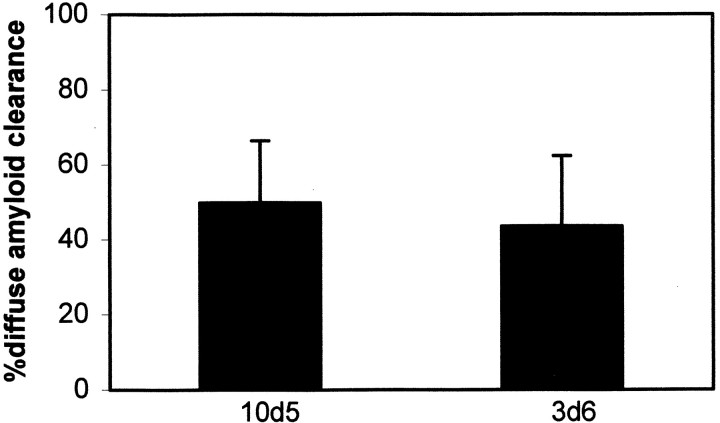

Fig. 4.

10d5 and 3d6 antibodies are equally effective at clearing diffuse amyloid-β deposits in the PDAPP mouse model after 3 d. 10d5 and 3d6 recognize the N-terminus residues 3–6 and 1–5, respectively, but their epitopes do not physically overlap. 10d5 (IgG1) and 3d6 (IgG2b) are different isotypes as well, suggesting that clearance in vivo is not specific to any one class of antibody. These data represent n = 9 sites from four animals. Not statistically different; Student's ttest.

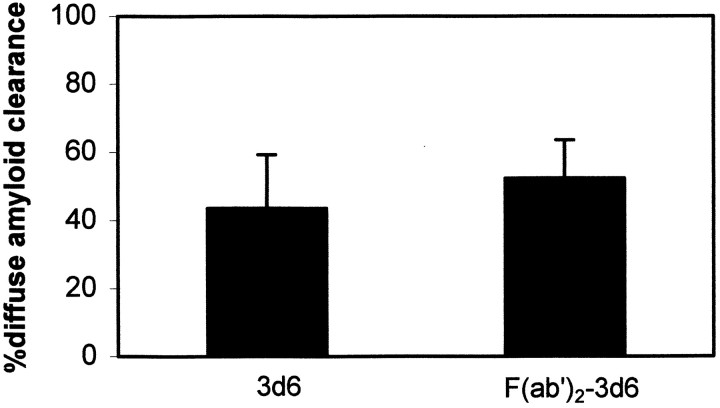

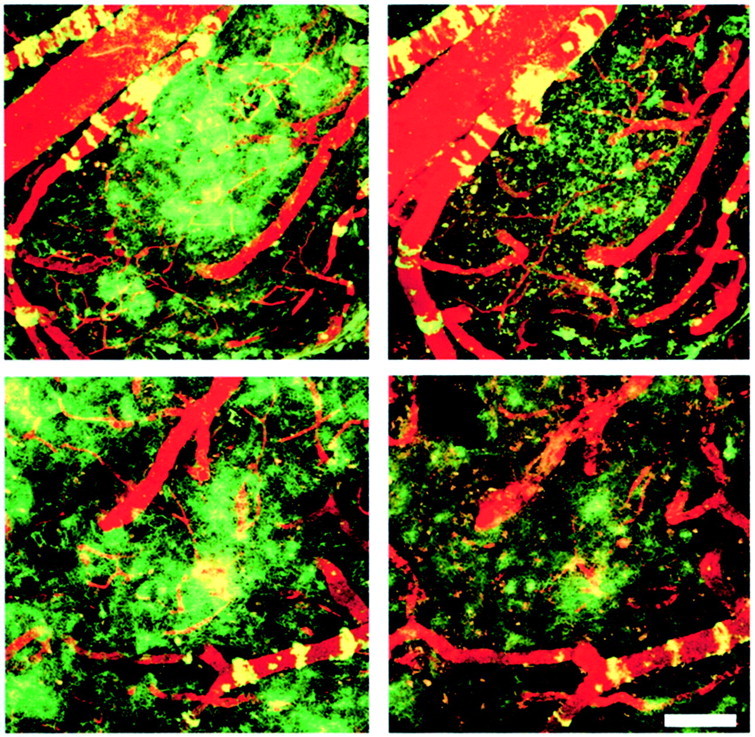

Previous reports have shown that amyloid-β clearance in an ex vivo assay proceeds through Fc-mediated phagocytosis by microglial cells, because F(ab′)2 fragments that lack the Fc portion of the antibody were ineffective (Bard et al., 2000). To evaluate this mechanism in vivo, we treated animals with FITC-labeled F(ab′)2 fragments of 3d6 and measured the clearance of amyloid-β deposits. The quantitative results are presented in Figure 5. F(ab′)2 fragments of 3d6 were as effective as full-length antibodies at clearing diffuse amyloid-β deposits in the PDAPP mice. The FITC-labeled F(ab′)2 fragments labeled amyloid-deposits in vivo, as shown in Figure6, and, within 3 d, over one-half of the labeled deposits were cleared, similar to the results obtained with full-length 3d6 or 10d5. The F(ab′)2 preparation was examined by Western blot, and no Fc could be detected. Moreover, sections of animals treated with F(ab′)2 were immunostained for the presence of Fc on plaques, and none could be detected. Histological examination of the tissue after the experiments showed some activation of microglia in all cases, probably resulting from the surgical preparation, and no difference between F(ab′)2 and 16b5-treated animals. These results demonstrate that, in addition to mechanisms involving Fc-mediated phagocytosis of antibody-labeled amyloid deposits, an alternative and efficacious mechanism exists for clearance of amyloid deposits that does not depend on Fc. Direct biophysical interaction of antibodies with amyloid-β deposits may be responsible for clearance by direct disaggregation of the deposits. Prevention of fibril formation, disaggregation, and inhibition of toxicity with antibodies has been demonstrated in vitro(Solomon et al., 1996, 1997; Frenkel et al., 2000), and our current results indicate that antibody-mediated disaggregation may occurin vivo. The F(ab′)2 results demonstrate that a mechanism not requiring receptor-mediated cellular activation is involved in clearance by immunotherapy with topical application in vivo.

Fig. 5.

F(ab′)2 fragments of 3d6 antibody are equally effective at leading to clearance of diffuse amyloid-β deposits after 3 d in the PDAPP mouse model. F(ab′)2fragments were purified and analyzed for Fc contamination by Western blot analysis and immunohistochemistry. No evidence for trace Fc was detected with either assay. Approximately one-half of the diffuse amyloid-β deposits were cleared 3 d after a single topical application to the cortex of the transgenic mice. Error bars represent means ± SE from n = 15 or 11 sites from four animals from each group. Not statistically different; Student's t test.

Fig. 6.

F(ab′)2 fragments of 3d6 antibody are equally effective at leading to clearance of diffuse amyloid-β deposits after 3 d in the PDAPP mouse model. These images are projections of three-dimensional volumes from the cortex of a representative PDAPP mouse treated with FITC-labeled 3d6 or 3d6-F(ab′)2 antibodies. The images were acquired in the anesthetized mouse using multiphoton microscopy. The left images shows labeled amyloid deposits at the initial application of antibody. Numerous diffuse deposits as well as amyloid angiopathy can be seen, pseudocolored green. A fluorescent angiogram (red) fills the blood vessels in each imaging session to facilitate image alignment. The right images are the same volumes 3 d later, immediately after application of labeled 10d5 antibody, which recognizes amyloid-β independently of 3d6. A majority of the amyloid-β deposits have been cleared in this 3 d period with both full-length (top row) and F(ab′)2 fragments (bottom row) of antibody. Scale bar, 100 μm.

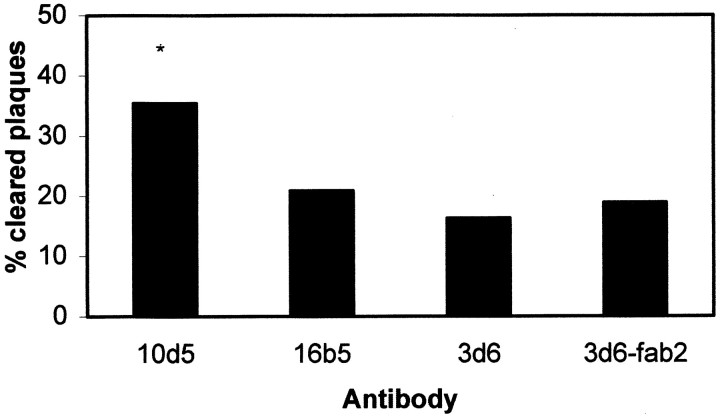

The results above focus on clearance of diffuse amyloid-β deposits. We also tested the ability of antibodies to lead specifically to the clearance of dense-core deposits in PDAPP mice. All plaques labeled with thioS were considered “dense-core” plaques. Animals were imaged with thioS, treated topically with antibody, and then imaged again with thioS 3 d later. thioS-positive plaques present in the initial imaging session were identified in the subsequent imaging session. If a plaque could not be found, then it was scored as “not found.” The fluorescent angiogram was used as a positive control for the quality of the imaging in the immediate volume of the plaque. The angiogram also permitted identifying the relative three-dimensional location of each plaque within the brain. The number of plaques not found divided by the total number of plaques identified in the initial imaging session was used to establish the percentage of cleared plaques, as shown in Figure 7. The ability of antibodies to lead to rapid clearance of thioS plaques is more variable. 10d5 was able to clear nearly 35% of identified dense-core plaques compared with control antibodies and 3d6 and 3d6-F(ab′)2, which showed ∼20% of plaques that could not be found at the second imaging session.

Fig. 7.

Dense-core plaques are cleared with 10d5 after 3 d in PDAPP mice. thioS-positive plaques were identified and counted in animals at the initial imaging–treatment session. In the subsequent session, after 3 d, the presence or absence of the individual plaques was scored in the identical locations within each animal, using the fluorescent angiogram as both a three-dimensional fiduciary marker, as well as a positive control for imaging quality. Two independent observers scored the presence or absence of identifiable plaques in the PDAPP mice. 16b5 is a fluorescently labeled control antibody that recognizes human tau. 3d6 and F(ab′)2fragments of 3d6 did not lead to appreciable clearance of thioS plaques after 3 d, whereas 10d5 led to the removal of 35% of identified plaques. Bars represent the percentage of identified plaques that were not found after 3 d. At least 45 plaques from 8–12 sites in four animals were scored for each group. *p < 0.05 indicates statistically significant byt test.

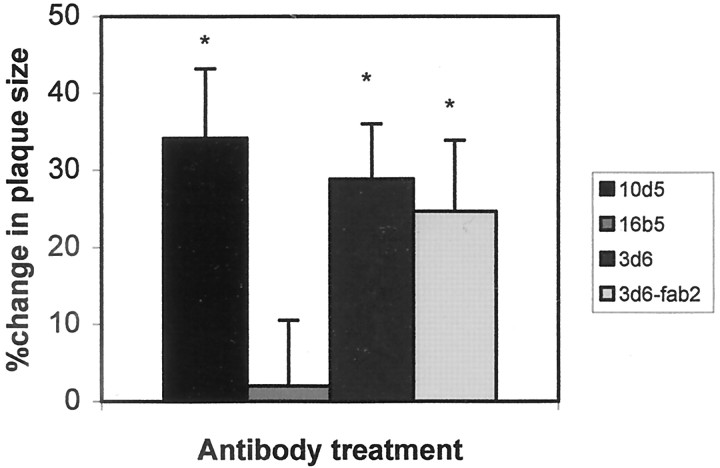

We wondered whether the 20% of plaques scored as “not found” in the control treatment reflected technical difficulties in reimaging plaques from session to session or a true change in plaques attributable to nonspecific stimuli associated with preparing a craniotomy and imaging. We reasoned that remaining plaques would shrink between the first and second imaging if affected by a process that ultimately would lead to their removal, whereas their size would remain constant if a failure to reimage the same plaques was attributable to technical issues. We therefore measured the size of the identified plaques that were not cleared. The results are shown in Figure8 and demonstrate that the plaques that were not cleared were reduced in size by ∼30% for 10d5, 3d6, and F(ab′)2 fragments of 3d6, but the measured plaque size was unchanged with the control antibody, 16b5. These results demonstrate that different antibodies and F(ab′)2fragments of 3d6 are effective at clearing or reducing the size of dense-core plaques, as well as clearing diffuse amyloid-β deposits within 3 d in vivo.

Fig. 8.

Remaining dense-core plaques in PDAPP mice are reduced in size 3 d after treatment with anti-amyloid-β antibodies. The identified plaques that were imaged in the first imaging session and remained after 3 d after a single antibody treatment were measured as described previously (Christie et al., 2001). Plaques that were cleared completely would have been measured as 100% change in size but are not included in this analysis. 10d5, 3d6, and F(ab′)2 fragments of 3d6 were equally effective at reducing the size of remaining dense-core plaques compared with control antibody 16b5. Error bars are mean ± SE from at least 12 plaques in four animals from each group. *p < 0.05 indicates statistically significant by Student's ttest.

DISCUSSION

Transgenic mouse models that overexpress APP develop senile plaques over time that resemble those found in human Alzheimer's disease. These animals are a valuable tool toward understanding the physiology and pathology of senile plaques in living tissue and are ideal for evaluating therapeutics aimed at clearance of amyloid-β deposits in the brain. With the recent success using immunotherapy for prevention of amyloid-β deposits in these animals (Schenk et al., 1999; Bard et al., 2000), as well as clearance of existing plaques (Bacskai et al., 2001), this treatment seems very promising. Recent reports have also indicated that immunotherapy may have positive effects on behavioral deficits exhibited in transgenic mouse models (Janus et al., 2000; Morgan et al., 2000). These findings are important for predicting whether anti-amyloid therapies will prove beneficial not just in arresting deposition of amyloid-β but also in prevention of the associated dementia. Microglial cells were implicated in the alterations of amyloid-β deposition by immunotherapy. Clearance of amyloid-β deposits in tissue sections by cultured microglia in anex vivo system was shown to be Fc receptor dependent (Bard et al., 2000). However, additional or alternative mechanisms for clearance of amyloid-β peptide are possible in vivo. Activation of the complement cascade may play a role in clearance. Direct interaction of antibodies with amyloid-β may lead to disruption of aggregates, as has been shown in vitro(Solomon et al., 1997), and this process should not depend on Fc receptor activation. A combination of Fc-dependent and Fc-independent mechanisms may be involved.

We used in vivo imaging using multiphoton microscopy to study the mechanisms of immunotherapeutic approaches toward removal of amyloid-β deposits in the brains of transgenic mice overexpressing APP. Our current results extend our observations showing antibody-mediated clearance of plaques in PDAPP mice (Bacskai et al., 2001) in several ways. First, the direct demonstration of clearance of amyloid-β deposits in vivo with anti-amyloid-β antibodies in another mouse model, Tg2576, was shown. This result suggests that the previous work in PDAPP mice can be extended to other animal models and is not dependent on the strain of animal, specific mutation in APP, or the specific patterns of expression of the transgene; behavioral studies in other mouse models in which immunotherapy proved beneficial also support this conclusion (Janus et al., 2000; Morgan et al., 2000). Second, an additional mouse monoclonal antibody of a different IgG isotype also led to effective clearance of previously deposited amyloid-β plaques in vivo. This result complements the observation that both of these antibodies can prevent deposition of amyloid-β after passive administration over a 6 month period in PDAPP mice (Bard et al., 2000), as well as both of the efficacy of the antibodies for the targeted digestion of plaques in an ex vivo preparation (Bard et al., 2000). The direct demonstration of clearance of existing, identified plaques in vivo with different antibodies is important in determining the specificity of the response. IgG1s do not activate complement in the mouse and may exhibit other specific differences that provide insight into the mechanism of clearance, particularly in the short time frame of 3 d. The difference in isotype may contribute to the effectiveness of the two antibodies at clearing dense-core plaques in the mice. Although both 3d6 and 10d5 were equally effective at clearing diffuse deposits in the animals and both antibodies led to similar decreases in size of remaining, identified dense-core plaques, 10d5 was more effective at completely clearing dense-core plaques in 3 d. It is possible that this subtle difference in efficacy is dependent on either the dose or time course of the treatment. Although both antibodies were added at the same dose for the same duration, they may have unequal affinities or effective actions at this concentration. Nonetheless, it is possible that complement activation or other differences between IgG1 and IgG2b contribute to the apparently enhanced rate of 10d5 clearance of dense-core plaques. This result suggests that even very similar antibodies may have subtly different efficacy.

Surprisingly, the F(ab′)2 fragments of 3d6 were as effective at clearance of diffuse amyloid-β deposits as full-length 3d6. F(ab′)2s lack the Fc portion of the antibody and therefore prohibit Fc-mediated phagocytosis of amyloid-β by microglia. Previous work with primary cultures of microglial cells and frozen tissue sections has demonstrated that this Fc-mediated mechanism is dominant in removal of amyloid-β deposits (Bard et al., 2000). The current results suggest that an alternative mechanism besides Fc-mediated phagocytosis can be involved in the clearance of amyloid-β deposits after topical administration in vivo. Other cellular mechanisms include activation of scavenger receptors (Huang et al., 1999; Bornemann et al., 2001) or receptors for advanced glycation end products (Munch et al., 1997; Tabaton et al., 1997; Bornemann et al., 2001). However, neither of these receptor-dependent mechanisms would be activated with F(ab′)2 fragments. Direct biophysical interaction of antibodies with amyloid-β may have led to disaggregation and removal of deposits in vivo, similar to results shownin vitro (Solomon et al., 1997). Likewise, a recent report demonstrated that peripheral antibodies may act as a sink for amyloid-β, removing it from the CNS and preventing plaque deposition in the brain (DeMattos et al., 2001).

Clearance may depend on multiple mechanisms, one involving direct interaction of antibodies [or F(ab′)2fragments] with the deposits resulting in disaggregation and the second involving cell-mediated clearance, possibly involving Fc receptor activation. The two mechanisms may occur independently, or may operate in tandem, with cellular removal of amyloid-β after disaggregation. Passive redistribution of soluble amyloid-β in CSF or plasma after disaggregation may occur (DeMattos et al., 2001). Characterization of these mechanisms will lead to an optimized therapeutic plan for efficient clearance of amyloid-β deposits.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institute on Aging Grants AG08487, P01 AG15453, and T32GM07753, as well as the Fidelity Foundation and the Walters Family Foundation.

Correspondence should be addressed to Dr. Bradley T. Hyman, Alzheimer's Disease Research Unit, Charlestown Navy Yard 2450, Massachusetts General Hospital, 114 16th Street, Charlestown, MA 02129. E-mail: bhyman@partners.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bacskai BJ, Kajdasz ST, Christie RH, Carter C, Games D, Seubert P, Schenk D, Hyman BT. Imaging of amyloid-beta deposits in brains of living mice permits direct observation of clearance of plaques with immunotherapy. Nat Med. 2001;7:369–372. doi: 10.1038/85525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bard F, Cannon C, Barbour R, Burke RL, Games D, Grajeda H, Guido T, Hu K, Huang J, Johnson-Wood K, Khan K, Kholodenko D, Lee M, Lieberburg I, Motter R, Nguyen M, Soriano F, Vasquez N, Weiss K, Welch B, Seubert P, Schenk D, Yednock T. Peripherally administered antibodies against amyloid beta-peptide enter the central nervous system and reduce pathology in a mouse model of Alzheimer disease. Nat Med. 2000;6:916–919. doi: 10.1038/78682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bornemann KD, Wiederhold KH, Pauli C, Ermini F, Stalder M, Schnell L, Sommer B, Jucker M, Staufenbiel M. Abeta-induced inflammatory processes in microglia cells of APP23 transgenic mice. Am J Pathol. 2001;158:63–73. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)63945-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Christie RH, Bacskai BJ, Zipfel WR, Williams RM, Kajdasz ST, Webb WW, Hyman BT. Growth arrest of individual senile plaques in a model of Alzheimer's disease observed by in vivo multiphoton microscopy. J Neurosci. 2001;21:858–864. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-03-00858.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeMattos RB, Bales KR, Cummins DJ, Dodart JC, Paul SM, Holtzman DM. Peripheral anti-A beta antibody alters CNS and plasma A beta clearance and decreases brain A beta burden in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:8850–8855. doi: 10.1073/pnas.151261398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Denk W, Strickler JH, Webb WW. Two-photon laser scanning fluorescence microscopy. Science. 1990;248:73–76. doi: 10.1126/science.2321027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frenkel D, Solomon B, Benhar I. Modulation of Alzheimer's beta-amyloid neurotoxicity by site-directed single-chain antibody. J Neuroimmunol. 2000;106:23–31. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(99)00232-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Games D, Adams D, Alessandrini R, Barbour R, Berthelette P, Blackwell C, Carr T, Clemens J, Donaldson T, Gillespie F, Guido T, Hagoplan S, Johnson-Wood K, Khan K, Lee M, Leibowitz P, Lieberburg I, Little S, Masliah E, McConlogue L. Alzheimer-type neuropathology in transgenic mice overexpressing V717F beta-amyloid precursor protein. Nature. 1995;373:523–527. doi: 10.1038/373523a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hsiao K, Chapman P, Nilsen S, Eckman C, Harigaya Y, Younkin S, Yang F, Cole G. Correlative memory deficits, Abeta elevation, and amyloid plaques in transgenic mice. Science. 1996;274:99–102. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5284.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang F, Buttini M, Wyss-Coray T, McConlogue L, Kodama T, Pitas RE, Mucke L. Elimination of the class A scavenger receptor does not affect amyloid plaque formation or neurodegeneration in transgenic mice expressing human amyloid protein precursors. Am J Pathol. 1999;155:1741–1747. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65489-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hyman BT, Trojanowski JQ. Consensus recommendations for the postmortem diagnosis of Alzheimer disease from the National Institute on Aging and the Reagan Institute Working Group on diagnostic criteria for the neuropathological assessment of Alzheimer disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1997;56:1095–1097. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199710000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Janus C, Pearson J, McLaurin J, Mathews PM, Jiang Y, Schmidt SD, Chishti MA, Horne P, Heslin D, French J, Mount HT, Nixon RA, Mercken M, Bergeron C, Fraser PE, St George-Hyslop P, Westaway D. A beta peptide immunization reduces behavioural impairment and plaques in a model of Alzheimer's disease. Nature. 2000;408:979–982. doi: 10.1038/35050110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Markesbery WR. Neuropathological criteria for the diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging. 1997;18 [Suppl 4]:S13–S19. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(97)00064-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morgan D, Diamond DM, Gottschall PE, Ugen KE, Dickey C, Hardy J, Duff K, Jantzen P, DiCarlo G, Wilcock D, Connor K, Hatcher J, Hope C, Gordon M, Arendash GW. A beta peptide vaccination prevents memory loss in an animal model of Alzheimer's disease. Nature. 2000;408:982–985. doi: 10.1038/35050116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Munch G, Thome J, Foley P, Schinzel R, Riederer P. Advanced glycation endproducts in ageing and Alzheimer's disease. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1997;23:134–143. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(96)00016-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Powers JM. Diagnostic criteria for the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging. 1997;18 [Suppl 4]:S53–S54. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(97)00070-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rubinsztein DC. The genetics of Alzheimer's disease. Prog Neurobiol. 1997;52:447–454. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(97)00014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schenk D, Barbour R, Dunn W, Gordon G, Grajeda H, Guido T, Hu K, Huang J, Johnson-Wood K, Khan K, Kholodenko D, Lee M, Liao Z, Lieberburg I, Motter R, Mutter L, Soriano F, Shopp G, Vasquez N, Vandevert C, Walker S, Wogulis M, Yednock T, Games D, Seubert P. Immunization with amyloid-beta attenuates Alzheimer-disease-like pathology in the PDAPP mouse. Nature. 1999;400:173–177. doi: 10.1038/22124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Selkoe DJ. Cell biology of the beta-amyloid precursor protein and the genetics of Alzheimer's disease. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1996;61:587–596. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Solomon B, Koppel R, Hanan E, Katzav T. Monoclonal antibodies inhibit in vitro fibrillar aggregation of the Alzheimer beta-amyloid peptide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:452–455. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.1.452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Solomon B, Koppel R, Frankel D, Hanan-Aharon E. Disaggregation of Alzheimer beta-amyloid by site-directed mAb. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:4109–4112. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.4109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tabaton M, Perry G, Smith M, Vitek M, Angelini G, Dapino D, Garibaldi S, Zaccheo D, Odetti P. Is amyloid beta-protein glycated in Alzheimer's disease? NeuroReport. 1997;8:907–909. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199703030-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wyss-Coray T, Lin C, Yan F, Yu G-Q, Rohde M, McConlogue L, Masliah E, Mucke L. TGF-B1 promotes microglial amyloid-beta clearance and reduces plaque burden in transgenic mice. Nat Med. 2001;7:612–618. doi: 10.1038/87945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang X, Renken R, Hyder F, Siddeek M, Greer CA, Shepherd GM, Shulman RG. Dynamic mapping at the laminar level of odor-elicited responses in rat olfactory bulb by functional MRI. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:7715–7720. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.13.7715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]