Abstract

Objective:

To classify and compare US nationwide opioid-related hospital inpatient discharges over time by discharge type: 1) opioid use disorder (OUD) diagnosis without opioid overdose, detoxification, or rehabilitation services, 2) opioid overdose, 3) OUD diagnosis or opioid overdose with detoxification services, and 4) OUD diagnosis or opioid overdose with rehabilitation services.

Methods:

Survey-weighted national analysis of hospital discharges in the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project National Inpatient Sample yielded age-adjusted annual rates per 100,000 population. Annual percentage change (APC) in the rate of opioid-related discharges by type during 1993–2016 was assessed.

Results:

The annual rate of hospital discharges documenting OUD without opioid overdose, detoxification, or rehabilitation services quadrupled during 1993–2016, and at an increased rate (8% annually) during 2003–2016. The discharge rate for all types of opioid overdose increased an average 5–9% annually during 1993–2010; discharges for non-heroin overdoses declined 2010–2016 (3–12% annually) while heroin overdose discharges increased sharply (23% annually). The rate of discharges including detoxification services among OUD and overdose patients declined (−4% annually) during 2008–2016 and rehabilitation services (e.g., counselling, pharmacotherapy) among those discharges decreased (−2% annually) during 1993–2016.

Conclusions:

Over the past two decades, the rate of both OUD diagnoses and opioid overdoses increased substantially in US hospitals while rates of inpatient detoxification and rehabilitation services identified by diagnosis codes declined. It is critical that inpatients diagnosed with OUD or treated for opioid overdose are linked effectively to substance use disorder treatment at discharge.

Keywords: Analgesics, Opioid, Substance-related disorders, Health services research

1. Introduction

Previous national reports on US inpatient opioid-related care have not differentiated overdose discharges from those during which a patient was diagnosed with opioid use disorder (OUD) without overdose, nor indicated whether detoxification (therapeutically supervised withdrawal over multiple days) or rehabilitation (clinical treatment and recovery support) services were provided (Hsu, McCarthy, Stevens, & Mukamal, 2017; Tedesco et al., 2017; Weiss, Elixhauser, Barrett, Steiner, & Bailey, 2016). Differentiating opioid-related hospital-based inpatient care in this way can provide a more complete picture of the impact of the opioid epidemic on US hospitals and illuminate hospitals’ role in direct provision of OUD treatment-related services.

Opioid overdose discharges are a measure of the epidemic’s direct impact on hospitals, while data on hospital-based inpatients diagnosed with OUD in the absence of overdose—that is, inpatients whose presenting symptom is not opioid overdose—can illustrate how hospitals services are more widely affected (Peterson, Xu, Mikosz, Florence, & Mack, 2018). Although regulatory, insurance reimbursement, and other issues mean that drug detoxification and rehabilitation are most commonly provided outside of hospitals, documenting the prevalence of such inpatient services is relevant as policymakers, clinicians, and public health officials identify ways to reduce epidemic levels of drug overdose deaths in the United States (D’Onofrio, McCormack, & Hawk, 2018; Hedegaard, Minino, & Warner, 2018; Sharma et al., 2017; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2018; Suzuki et al., 2015). Inpatient substance use disorder detoxification and rehabilitation began to decline in the 1990s, and research has indicated that outpatient options have a higher benefit-cost ratio (Florida Alcohol and Drug Abuse Association; Mark, Dilonardo, Chalk, & Coffey, 2002). However, it has long been clear that hospitals treat a large number of patients in need of such services; inpatients have a high prevalence of current and lifetime substance use disorders (Brown, Leonard, Saunders, & Papasouliotis, 1998). The gap between opioid treatment need and treatment received is immense—less than one in five people with OUD receive treatment services in any setting (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2017)—and population opioid overdose mortality is presumably correlated with that gap.

In the context of an ongoing opioid overdose epidemic, it is relevant to understand more about the people at risk of opioid overdose mortality that are treated in US hospitals. This brief report aimed to classify US nationwide opioid-related hospital-based inpatient discharges over time by discharge type: 1) opioid use disorder (OUD) diagnosis without opioid overdose, detoxification, or rehabilitation services provided, 2) opioid overdose, 3) OUD diagnosis or opioid overdose with detoxification services, and 4) OUD diagnosis or opioid overdose with rehabilitation services.

2. Methods

2.1. Data

This study used publicly available 1993–2016 survey-weighted annual national estimates of US hospital discharges from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project National Inpatient Sample (HCUP-NIS) and no human subjects. HCUP-NIS is a 20% stratified sample of community hospital discharges—excluding long-term acute care and rehabilitation (e.g., recovery following stroke or brain injury) hospitals—from participating states, which in 2016 represented over 97% of the US population (Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project, 2018). Standard HCUP-NIS survey weighting and Census population data made the discharges sample representative of all US discharges for age-adjusted estimates (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017).

Table 1 demonstrates International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision/Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9/10-CM) and other codes that defined each opioid-related discharge category. Transition to ICD-10-CM occurred October 1, 2015. These codes are consistent with recent studies on OUD, overdoses, and drug detoxification and rehabilitation (counselling and pharmacotherapy) services (Heslin et al., 2017; Peterson et al., 2018; Tedesco et al., 2017; Zhu & Wu, 2018). This study followed physician coding guidance (Providers Clinical Support System, 2018) indicating the use of ICD-CM codes for both opioid dependence and opioid use disorder to identify problematic opioid use, and assumed that these codes would not appear on inpatient records for patients with acceptable opioid use. In Table 1, the OUD category (#1) comprised unique discharges, while 25% of discharges in the opioid overdose category (#2, All) included OUD diagnosis codes (i.e., overlap with category #1), and just 2% of opioid overdose discharges (#2, All) included inpatient drug detoxification or rehabilitation services (i.e., overlap with categories #3 or #4) (data not shown).

Table 1.

Opioid-related discharge definitions.

| 1. Opioid use disorder (OUD) discharges, excluding overdose, detoxification, rehabilitation services | 1. Include discharges with any value a. Diagnosis code: 304.0, 304.7, 305.5, F11.1, F11.2 |

| 2. Exclude discharges with any value a. Diagnosis code: 304.03, 304.73, 305.53, F11.11, F11.21, 965.00–02, 965.09, 965.8, E850.0–2, E850.8, T40.0X1–4, T40.1X1–4, T40.2X1–4, T40.3X1–4, T40.4X1–4, T40.6X1–4 b. Procedure code: 94.45, 94.64–9, HZ2–6, HZ81–2, HZ84–6, HZ88–9, HZ91–2, HZ94–6, HZ98–9 c. Diagnostic Related Group code: 895 | |

| 2. Opioid overdose discharges | 1. All: Include discharges with any value a. Diagnosis code: 965.00–02, 965.09, 965.8, E850.0–2, E850.8, T40.0X1–4, T40.1X1–4, T40.2X1–4, T40.3X1–4, T40.4X1–4, T40.6X1–4 |

| 2. Heroin: Include discharges with any value a. Diagnosis code: 965.01, E850.0, T40.1X1–4 | |

| 3. OUD or opioid overdose discharges with drug detoxification services | 1. Include discharges with any value a. Procedure code: 94.65, 94.66, 94.68, 94.69, HZ2 |

| 2. Discharges must also include any value a. Diagnosis code: 304.0, 304.7, 305.5, F11.1, F11.2, 965.00–02, 965.09, 965.8, E850.0–2, E850.8, T40.0X1–4, T40.1X1–4, T40.2X1–4, T40.3X1–4, T40.4X1–4, T40.6X1–4 | |

| 3. Exclude discharges with any value a. Diagnosis code: 304.03, 304.73, 305.53, F11.11, F11.21 | |

| 4. OUD or opioid overdose discharges with drug rehabilitation servicesss | 1. Include discharges with any value a. Procedure code: 94.45, 94.64, 94.66–7, 94.69, HZ3–6, HZ81–2, HZ84–6, HZ88–9, HZ91–2, HZ94–6, HZ98–9 b. Diagnostic Related Group code: 895 |

| 2. Discharges must also include any value a. Diagnosis code: 304.0, 304.7, 305.5, F11.1, F11.2, 965.00–02, 965.09, 965.8, E850.0–2, E850.8, T40.0X1–4, T40.1X1–4, T40.2X1–4, T40.3X1–4, T40.4X1–4, T40.6X1–4 | |

| 3. Exclude discharges with any value a. Diagnosis code: 304.03, 304.73, 305.53, F11.11, F11.21 |

2.2. Analysis

Authors report the US age-adjusted annual rate per 100,000 population of opioid-related discharges by type during 1993–2016 and the average annual percentage change (APC) in the rate of discharges by type using Joinpoint regression analysis. HCUP-NIS discharge records with missing patient age were not included, nor were those indicating patient transfer to short-term hospitals (to avoid double-counting discharges). Authors used SAS 9.4 (Cary, North Carolina) for survey dataset weighting and descriptive analysis, and Joinpoint Regression Program 4.5.0.1 (National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD) for analysis of population discharge rate APC by discharge type.

3. Results

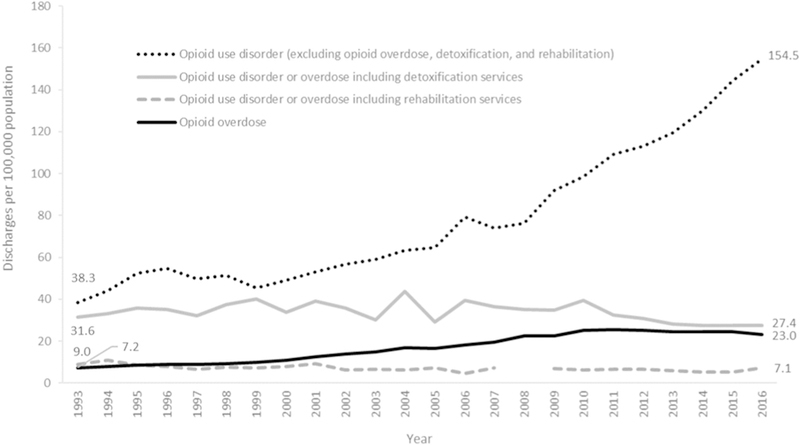

The age-adjusted annual rate per 100,000 population for hospital discharges documenting OUD (excluding opioid overdose, detoxification, or rehabilitation services) was over four times higher in 2016 than in 1993 (154.5 versus 38.3) (Fig. 1). During 1993–2003, the discharge rate increased an average of 2.8% (95% CI: 0.5–5.1) per year, then increased in a statistically significant way—based on non-overlapping 95% CI—to an average 8.0% (7.4–8.6) per year during 2003–2016 (Table 2).

Fig. 1. Annual US age-adjusted opioid-related hospital inpatient discharge rates by type.

Data not reported if relative standard error was > 30% or standard error = 0.

Data source: Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project National Inpatient Sample.

Table 2.

Average annual percentage change in the discharge rate (per 100,000 population) for US age-adjusted opioid-related hospital inpatient discharges by type.

| Discharge type | Perioda | Annual percentage change, average for period (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Opioid use disorder without overdose, detoxification, or rehabilitation services | 1993–2003 2003–2016 |

2.8 (0.5 to 5.1) 8.0 (7.4 to 8.6) |

|

| Opioid overdose | All | 1993–1998 1998–2010 2010–2016 |

5.3 (2.1 to 8.6) 8.6 (7.8 to 9.4) −1.4 (−2.6 to −0.2) |

| Heroin | 1993–2010 2010–2016 |

1.0 (−0.1 to 2.1) 23.3 (20.0 to 26.7) |

|

| Non-heroin | 1993–1999 1999–2002 2002–2010 2010–2014 2014–2016 |

5.2 (3.1 to 7.3) 15.6 (5.0 to 27.3) 8.4 (7.1 to 9.7) −3.0 (−6.4 to 0.4) −12.1 (−17.2 to −6.7) |

|

| OUD or overdose with detoxification services | 1993–2008 2008–2016 |

0.3 (−1.1 to 1.8) −3.9 (−6.2 to −1.6) |

|

| OUD or overdose with rehabilitation services | 1993–2016 | −1.7 (−2.5 to −0.9) | |

Notes. OUD = opioid use disorder.

See Table 1 for discharge definitions by administrative code (e.g., ICD-9/10-CM).

Data source: Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project National Inpatient Sample.

Year clusters for each discharge type were empirically derived through Joinpoint regression analysis.

The discharge rate for any type of opioid overdose was over three times higher in 2016 compared to 1993 (23.0 versus 7.2 per 100,000 population) (Fig. 1). The average APC in the opioid overdose discharge rate increased from 5.3% per year during 1993–1998 to 8.6% during 1998–2010, and then began to decline at an average of 1.4% per year during 2010–2016 (Table 2). This decline, as previously reported using HCUP-NIS data through 2014 (Tedesco et al., 2017), was due to fewer non-heroin opioid overdose discharges (Table 2), which comprised a large proportion of all opioid overdose discharges. In contrast, the APC in the discharge rate for heroin overdoses increased at an average 23.3% per year during 2010–2016 (Table 2).

The rate of opioid-related discharges including detoxification or rehabilitation services was relatively low throughout the study period (Fig. 1). The rate of opioid-related discharges including detoxification services was lower in 2016 compared to 1993 (27.4 versus 31.6 per 100,000 population, or − 13%) (Fig. 1), and there was a significant average APC decline (−3.9%) in the rate of those discharges during 2008–2016 (Table 2). The rate of opioid-related discharges that included any rehabilitation services was 21% lower in 2016 compared to 1993 (7.1 versus 9.0 per 100,000 population) (Fig. 1) and there was a steady average APC decline (−1.7%) in that discharge rate over the entire study period (Table 2).

4. Discussion

Over nearly the past quarter century, the rate of US community hospital inpatient discharges indicating patients’ OUD or opioid overdose increased while rates at which those hospitals provided detoxification or rehabilitation services to those populations appears to have declined. The relatively high prevalence of discharges documenting patients’ OUD without overdose over the past 24 years provides further evidence that the number of people affected by opioid use disorder is many times greater than the number of opioid-related deaths or medically-treated opioid overdoses suggests. For example, in 2016, there were 42,249 opioid-related deaths (Seth, Scholl, Rudd, & Bacon, 2018). The same year, this study documented an estimated 78,345 hospital discharges for opioid overdose (including fatalities in the hospital) and 520,185 discharges documenting OUD without overdose (data not shown; population rate, but not number of discharges, is demonstrated in Fig. 1).

Previous research has indicated that patients with substance use disorders are often discharged without specific treatment plans—an analysis of among patients hospitalized with injection drug use-associated infective endocarditis reported just 8% of discharge summaries included a plan for medication-assisted treatment (MAT) (Rosenthal, Karchmer, Theisen-Toupal, Castillo, & Rowley, 2016). A low proportion (an estimated 17%) of discharged inpatients with OUD or opioid overdose subsequently engage in outpatient substance use disorder treatment (Naeger, Mutter, Ali, Mark, & Hughey, 2016). Failing to engage inpatients with OUD or opioid overdose in a treatment plan has serious consequences; even among patients who go through inpatient opioid detoxification, one study reported 27% relapsed on the day of discharge (Bailey, Herman, & Stein, 2013). Discussion continues about the optimal approach to OUD pharmacotherapy (Stotts, Dodrill, & Kosten, 2009) and barriers to treatment initiation are complex (Timko, Schultz, Britt, & Cucciare, 2016). Many inpatients with substance use disorders face multiple comorbid conditions and risk factors for ill-health such as homelessness (Raven et al., 2010). Despite such challenges, research has also shown that discharged patients have better outcomes when their substance use disorder is addressed during inpatient care (Suzuki et al., 2015; Trowbridge et al., 2017; Wakeman, Metlay, Chang, Herman, & Rigotti, 2017).

Inpatients with substance use disorder are frequently readmitted within the first few months following discharge (Nordeck et al., 2018; Walley et al., 2012), presumably at substantial cost. Fee-for-service reimbursement means that hospital readmissions and other health care costs attributable to patients’ substance use disorder are paid by health care payers (e.g., insurance companies, employers, and public payers like Medicare), and not hospitals; therefore, fee-for-service does not provide an explicit financial incentive for hospitals to invest in programs and services that transition patients to treatment. Health care payment reforms, such as episode-based payment—or, bundled payments for multiple related health care services provided to treat a clinical condition within a specified time period—aim to incentivize providers’ participation in patients’ health outcomes beyond a single clinical contact (US Centers for Medicaid & Medicare Services, 2016).

4.1. Limitation

This study classified opioid-related health care contacts in one clinical setting—hospital inpatient. It was not possible to observe how many patients were, at the time of admission, engaged in outpatient treatment services. Given that less than one in five people with OUD report receiving treatment services in any setting, this circumstance may have affected a low number of patients (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2017). This analysis could not observe how many discharges occurred for the same patients; prevalence estimates presented here refer to number of discharges, not people. The 24 years of HCUP-NIS data analyzed for this study included an increasing number of states contributing data over time; therefore, it is possible that trends among states drove some of the observed variation in the national rate data presented.

This study examined the prevalence of ICD-CM codes that identify detoxification and rehabilitation services, but notably—based on data available in HCUP-NIS—this study was not able to directly examine receipt of MAT by observing patients’ inpatient medications nor referrals to services following discharge. Each of those measures would provide meaningful data to more thoroughly examine the contribution of inpatient care to OUD detoxification and rehabilitation efforts, and reduce reliance on ICD-CM codes to identify the services this study sought to analyze. This study assumed that administrative codes (e.g., ICD-CM) in the analyzed discharge records accurately described inpatient opioid-related services as the study intended, although authors are not aware of validation studies. Moreover, it is possible that ICD-CM coding among the examined discharge records prioritized reimbursement considerations in a way that could have obscured the true prevalence of the services this study intended to capture. Procedure and DRG codes in hospital discharge records that identify drug detoxification and rehabilitation services are not opioid-specific. HCUP-NIS does not include data from long-term acute care and rehabilitation programs nor indicate whether patients were discharged to substance use rehabilitation programs.

Owing to available ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes, this did not distinguish among opioid-related discharges further by opioid type, which has been important for understanding the nature of the opioid overdose mortality—in particular, due to fentanyl (Scholl, Seth, Kariisa, Wilson, & Baldwin, 2018). Substance use disorder in general is underdiagnosed (Morasco & Dobscha, 2008); therefore, this study’s estimates of OUD discharges are likely lower than the actual rate of hospital discharges that include OUD. It was not possible to assess what proportion of OUD diagnoses represent true increased incidence as opposed to increased clinician awareness and documentation of OUD as publicity has grown about the opioid epidemic. This study did not assess non-opioid substance use; opioids might be one of multiple substances misused by patients whose discharges this study has categorized only in terms of opioids. The US opioid epidemic is dynamic and evolving. Important issues have been documented in previous research studies that focused on recent year-to-year changes (Scholl et al., 2018; Seth et al., 2018). This study, on the other hand, prioritized a longer-term historic perspective to describe broad trends in opioid-related hospital discharge categories.

ICD-10-CM classification was implemented in October 2015 and affected only the last one year and three months of the study’s 24-year analysis period. Recent research from some US states comparing 2015 and 2016 data has reported that transition to ICD-10-CM coding was associated with a substantially increased number of opioid-related discharges (Heslin et al., 2017). One relevant finding from that research with respect to this study’s results is that diagnoses for OUD decreased and diagnoses for opioid-related adverse events increased after the ICD-10-CM transition. Future analysis of opioid-related discharges after October 2015 can provide more information.

5. Conclusions

It is critical to continue to monitor health service data sources for insight into opioid and all substance use disorder trends and build the capacity for health care systems to implement evidence-based substance use disorder treatments that provide affected individuals, families, and communities relief from the devastating effects of substance use disorder morbidity and mortality. Analysis of longitudinal data including all clinical settings is important to identify substance use disorder treatment services with the greatest probability of patient success and value for health care investments.

Acknowledgements

Authors thank Mark Faul of the CDC for comments on an early draft. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Funding source

No external funding.

Abbreviations:

- APC

annual percentage change

- CI

Confidence interval

- DRG

Diagnosis Related group

- HCUP-NIS

Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project National Inpatient Sample

- ICD-9/10-CM

International Classification of Diseases, Ninth/Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification

- MAT

medication-assisted treatment

- OUD

opioid use disorder

Footnotes

Financial disclosures

The authors have no relevant financial relationships interest to disclose.

References

- Bailey GL, Herman DS, & Stein MD (2013). Perceived relapse risk and desire for medication assisted treatment among persons seeking inpatient opiate detoxification. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 45(3), 302–305. 10.1016/j.jsat.2013.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RL, Leonard T, Saunders LA, & Papasouliotis O (1998). The prevalence and detection of substance use disorders among inpatients ages 18 to 49: An opportunity for prevention. Preventive Medicine, 27(1), 101–110. 10.1006/pmed.1997.0250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2017, Jun 26, 2017). Bridged-race population estimates -Data files and documentation Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/bridged_race/data_documentation.htm

- D’Onofrio G, McCormack RP, & Hawk K (2018). Emergency departments -a 24/7/ 365 option for combating the opioid crisis. New England Journal of Medicine, 379(26), 2487–2490. 10.1056/NEJMp1811988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florida Alcohol & Drug Abuse Association Cost-benefit analyses: Substance abuse treatment is a sound investment. Retrieved from https://www.fadaa.org/.

- Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (2018). Introduction to the HCUP National Inpatient Sample (NIS) 2016 Retrieved from https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/nation/nis/nisdbdocumentation.jsp.

- Hedegaard H, Minino AM, & Warner M (2018). Drug overdose deaths in the United States, 1999–2017. NCHS Data Brief, 329, 1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heslin KC, Owens PL, Karaca Z, Barrett ML, Moore BJ, & Elixhauser A (2017). Trends in opioid-related inpatient stays shifted after the US transitioned to ICD-10-CM diagnosis coding in 2015. Medical Care, 55(11), 918–923. 10.1097/mlr.0000000000000805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu DJ, McCarthy EP, Stevens JP, & Mukamal KJ (2017). Hospitalizations, costs and outcomes associated with heroin and prescription opioid overdoses in the United States 2001–12. Addiction, 112(9), 1558–1564. 10.1111/add.13795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mark TL, Dilonardo JD, Chalk M, & Coffey RM (2002). Trends in inpatient detoxification services, 1992–1997. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 23(4), 253–260. 10.1016/S0740-5472(02)00271-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morasco BJ, & Dobscha SK (2008). Prescription medication misuse and substance use disorder in VA primary care patients with chronic pain. General Hospital Psychiatry, 30(2), 93–99. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naeger S, Mutter R, Ali MM, Mark T, & Hughey L (2016). Post-discharge treatment engagement among patients with an opioid-use disorder. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 69, 64–71. 10.1016/j.jsat.2016.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordeck CD, Welsh C, Schwartz RP, Mitchell SG, Cohen A, O’Grady KE, & Gryczynski J (2018). Rehospitalization and substance use disorder (SUD) treatment entry among patients seen by a hospital SUD consultation-liaison service. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 186, 23–28. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.12.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson C, Xu L, Mikosz CA, Florence C, & Mack KA (2018). US hospital dis-charges documenting patient opioid use disorder without opioid overdose or treatment services, 2011–2015. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 92, 35–39. doi:doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2018.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Providers Clinical Support System (2018). Opioid Use Disorder Diagnostic Criteria Retrieved from http://pcssnow.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/5B-DSM-5-Opioid-Use-Disorder-Diagnostic-Criteria.pdf.

- Raven MC, Carrier ER, Lee J, Billings JC, Marr M, & Gourevitch MN (2010). Substance use treatment barriers for patients with frequent hospital admissions. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 38(1), 22–30. 10.1016/j.jsat.2009.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal ES, Karchmer AW, Theisen-Toupal J, Castillo RA, & Rowley CF (2016). Suboptimal addiction interventions for patients hospitalized with injection drug use-associated infective endocarditis. American Journal of Medicine, 129(5), 481–485. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholl L, Seth P, Kariisa M, Wilson N, & Baldwin G (2018). Drug and opioid-in-volved overdose deaths-United States, 2013–−2017. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 67(5152), 1419–1427. 10.15585/mmwr.mm675152e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seth P, Scholl L, Rudd RA, & Bacon S (2018). Overdose deaths involving opioids, cocaine, and psychostimulants-United States, 2015–2016. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 67(12), 349–358. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6712a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma A, Kelly SM, Mitchell SG, Gryczynski J, O’Grady KE, & Schwartz RP (2017). Update on barriers to pharmacotherapy for opioid use disorders. Current Psychiatry Reports, 19(6), 35 10.1007/s11920-017-0783-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stotts AL, Dodrill CL, & Kosten TR (2009). Opioid dependence treatment: options in pharmacotherapy. Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy, 10(11), 1727–1740. 10.1517/14656560903037168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (2017). Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. SMA 17–5044, NSDUH Series H-52) Retrieved from Rockville, MD: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2018, September 28, 2015). Medication and counseling treatment Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/medication-assisted-treatment/treatment

- Suzuki J, DeVido J, Kalra I, Mittal L, Shah S, Zinser J, & Weiss RD (2015). Initiating buprenorphine treatment for hospitalized patients with opioid dependence: A case series. American Journal on Addictions, 24(1), 10–14. 10.1111/ajad.12161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tedesco D, Asch SM, Curtin C, Hah J, McDonald KM, Fantini MP, & Hernandez-Boussard T (2017). Opioid abuse and poisoning: Trends in inpatient and emergency department discharges. Health Affairs, 36(10), 1748–1753. 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timko C, Schultz NR, Britt J, & Cucciare MA (2016). Transitioning from detox-ification to substance use disorder treatment: Facilitators and barriers. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 70, 64–72. 10.1016/j.jsat.2016.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trowbridge P, Weinstein ZM, Kerensky T, Roy P, Regan D, Samet JH, & Walley AY (2017). Addiction consultation services -linking hospitalized patients to out-patient addiction treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 79, 1–5. 10.1016/j.jsat.2017.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Centers for Medicaid & Medicare Services. (2016, November 28, 2016). Frequently asked questions regarding the 2015 supplemental quality and resource use reports Retrieved from https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/PhysicianFeedbackProgram/Episode-Costs-and-Medicare-Episode-Grouper.html [Google Scholar]

- Wakeman SE, Metlay JP, Chang Y, Herman GE, & Rigotti NA (2017). Inpatient addiction consultation for hospitalized patients increases post-discharge abstinence and reduces addiction severity. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 32(8), 909–916. 10.1007/s11606-017-4077-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walley AY, Paasche-Orlow M, Lee EC, Forsythe S, Chetty VK, Mitchell S, & Jack BW (2012). Acute care hospital utilization among medical inpatients dis-charged with a substance use disorder diagnosis. Journal of Addiction Medicine, 6(1), 50–56. 10.1097/ADM.0b013e318231de51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss AJ, Elixhauser A, Barrett ML, Steiner CA, Bailey MK, & O’Malley L (2016). Opioid-related inpatient stays and emergency department visits by state, 2009–2014: Statistical brief #219. Healthcare cost and utilization project (HCUP) statistical briefs Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US; ). [Google Scholar]

- Zhu H, & Wu L-T (2018). National trends and characteristics of inpatient detoxification for drug use disorders in the United States. BMC Public Health, 18(1), 1073 10.1186/s12889-018-5982-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]