Abstract

Introduction

Multiple comorbidities among HIV‐positive individuals may increase the potential for polypharmacy causing drug‐to‐drug interactions and older individuals with comorbidities, particularly those with cognitive impairment, may have difficulty in adhering to complex medications. However, the effects of age‐associated comorbidities on the treatment outcomes of combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) are not well known. In this study, we investigated the effects of age‐associated comorbidities on therapeutic outcomes of cART in HIV‐positive adults in Asian countries.

Methods

Patients enrolled in the TREAT Asia HIV Observational Database cohort and on cART for more than six months were analysed. Comorbidities included hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidaemia and impaired renal function. Treatment outcomes of patients ≥50 years of age with comorbidities were compared with those <50 years and those ≥50 years without comorbidities. We analysed 5411 patients with virological failure and 5621 with immunologic failure. Our failure outcomes were defined to be in‐line with the World Health Organization 2016 guidelines. Cox regression analysis was used to analyse time to first virological and immunological failure.

Results

The incidence of virologic failure was 7.72/100 person‐years. Virological failure was less likely in patients with better adherence and higher CD4 count at cART initiation. Those acquiring HIV through intravenous drug use were more likely to have virological failure compared to those infected through heterosexual contact. On univariate analysis, patients aged <50 years without comorbidities were more likely to experience virological failure than those aged ≥50 years with comorbidities (hazard ratio 1.75, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.31 to 2.33, p < 0.001). However, the multivariate model showed that age‐related comorbidities were not significant factors for virological failure (hazard ratio 1.31, 95% CI 0.98 to 1.74, p = 0.07). There were 391 immunological failures, with an incidence of 2.75/100 person‐years. On multivariate analysis, those aged <50 years without comorbidities (p = 0.025) and age <50 years with comorbidities (p = 0.001) were less likely to develop immunological failure compared to those aged ≥50 years with comorbidities.

Conclusions

In our Asia regional cohort, age‐associated comorbidities did not affect virologic outcomes of cART. Among those with comorbidities, patients <50 years old showed a better CD4 response.

Keywords: HIV, cART, age‐associated comorbidity, immunological failure, virological failure, TAHOD (TREAT Asia HIV Observational Database)

1. Introduction

Combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) has dramatically improved the survival and quality of life for people living with HIV 1, 2, 3. A growing proportion of patients are over the age of 50 years, and by the end of 2013, over four million individuals older than 50 years were living with HIV infection worldwide 4. For instance, in Canada the number of older adults with HIV has doubled over the past 20 years, and in Western Europe the estimated number of people living with HIV aged 50 years and over has almost quadrupled over the past decade 5, 6. Despite successful cART, many ageing HIV‐positive patients have developed age‐associated comorbidities such as cardiovascular, metabolic, pulmonary, renal, bone and malignant diseases, and these are often more prevalent compared with HIV‐negative individuals 7, 8. Risk and management of comorbidities in ageing adults with HIV will continue to evolve as treatment improves and life expectancy increases 5, 6.

Polypharmacy is also common in the HIV‐positive older adult population 9, 10. The Swiss HIV cohort study comparing HIV‐positive adults aged ≥50 years with HIV‐positive patients aged <50 years on cART found that older patients were more likely to receive one or more co‐medications compared with younger patients 11. This study also determined that older patients had more frequent potential for drug‐to‐drug interactions when compared to younger patients. The effects of polypharmacy may be more substantial in older HIV‐positive persons because of the increased chance of drug‐to‐drug interactions 9, 12. It has been shown that older HIV‐positive patients have better adherence to cART than younger patients 13, 14, and this can increase the likelihood of potential drug interactions. Drug interactions might be associated with a substantial risk for toxicity, decreased efficacy and subsequent emergence of drug resistance.

Another paper with the Swiss HIV cohort study investigated the prevalence of comedications and potential drug‐to‐drug interactions within a large HIV cohort, and their effect on ART efficacy and tolerability 15. They found potential drug‐to‐drug interactions increase with complex ART and comorbidities, but no adverse effect was noted on ART efficacy or tolerability.

Previous studies showed older HIV‐positive individuals have a less robust immune response but, likely due to better adherence, a better virologic response 16, 17, 18. However, multiple comorbidities among HIV‐positive individuals may increase the potential for polypharmacy and older individuals with comorbidities, particularly those with cognitive impairment, may have difficulty in adhering to complex medication regimens 13. However, the effects of age‐associated comorbidities on the treatment outcomes of cART are not well known. In this study, we investigated the effects of age‐associated comorbidities on therapeutic outcomes of cART in HIV‐positive adults in Asian countries.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design and data collection

We analysed data from the TREAT Asia HIV Observational Database (TAHOD), a prospective, observational cohort study of HIV‐positive adults enrolled from 21 clinical sites, which is a contributing cohort to IeDEA Asia‐Pacific 19. We selected eligible subjects for this analysis among patients who were enrolled in TAHOD from 2003 to 2015. The TAHOD database and methods have been previously described 20. Due to the observational nature of the cohort, viral load (VL) and CD4 testing are not performed on a predefined basis but depend on the site's local practices and the patient's financial circumstances. Institutional review board approvals were obtained at all participating sites, the data management and analysis centre (Kirby Institute, University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia), and the coordinating centre (TREAT Asia/amfAR, Bangkok, Thailand). Patients provided written informed consent to participate in the TAHOD where required by local institutional review boards.

2.2. Definitions

Patients were included in the analysis if they had been on cART for more than 6 months. Our failure outcomes were defined to be in‐line with the World Health Organization (WHO) 2016 guidelines 21 as follows: (i) virological failure was defined as a single VL >1000 copies/mL; (ii) immunological failure was defined as CD4 count falling below 250 cells/μL after a clinical failure, or persistent CD4 levels below 100 cells/μL (two consecutive CD4 counts below 100 cells/μL within six months). We assumed no treatment failure had occurred if there was an absence of VL or CD4 count. We utilized a single VL measurement, rather than a second confirmatory testing, as the median VL testing frequency in our cohort was 1 (interquartile range (IQR) 1 to 2) per patient per year. Patients were included in the virological failure analysis if they had at least one VL measurement available after six months on cART. Immunological failure analysis included patients with pre‐cART CD4 count available and at least one CD4 measurement after six months from cART initiation. Both analyses were censored at four years from cART initiation.

Comorbidities evaluated included hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidaemia and impaired renal function. Hypertension was defined as a diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg and/or systolic blood pressure ≥140 mmHg 22; diabetes was defined as a fasting blood glucose level ≥7.0 mmol/L or 126 mg/dL 23; dyslipidaemia was defined using any one of the following four criteria: total cholesterol ≥240 mg/dL, triglyceride ≥200 mg/dL, high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol <40 mg/dL, low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol ≥160 mg/dL according to National Cholesterol Education Programme ATP‐III guidelines; impaired renal function was defined as an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) <60 mL/minute by CKD EPI equation 24.

Patients were grouped into four categories according to their age and comorbidities: (i) age <50 years with no comorbidities, (ii) age <50 years with comorbidities, (iii) age ≥50 years without comorbidities, and (iv) age ≥50 years with comorbidities. Age‐associated comorbidity and cART adherence were included as time‐varying variables. Time‐fixed covariates included in the analyses were sex, HIV‐1 exposure risks, baseline CD4 cell count, baseline viral load, cART regimen, prior AIDS‐defining illness, hepatitis co‐infection and smoking history. Ethnicity was reported descriptively but not included in the regression analyses due to the inclusion of site as a stratification variable. Year of cART initiation was not included in the multivariate model selection due to collinearity with cART adherence, as our cohort began collecting adherence data from 2011 onwards. However, we assessed the direction of the hazard ratios (HRs) by adjusting with other significant covariates in the absence of the adherence variable.

2.3. Statistical analysis

Cox regression analysis was used to analyse time to first virological and immunological failure, stratified by clinical site. Risk time started six months from cART initiation. Patients who did not fail in either category were censored on the last date of VL testing for the virological failure analysis, and of CD4 testing for immunological failure analysis, all within four years from cART initiation. Sensitivity analyses were performed disaggregating by sex. Data management and statistical analyses were conducted using SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) and STATA software version 14 (STATA Corp., College Station, TX, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Patient characteristics

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of patients included in both the virological and immunological analyses. In the virological failure analysis, a total of 5411 patients were included from Cambodia, China, Hong Kong SAR, India, Indonesia, Japan, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan, Thailand and Vietnam. The median age at cART initiation was 35 years (IQR 29 to 41), with 66% being aged <50 years without the presence of co‐morbidities prior to cART initiation. Most patients were male (71%) and the majority were Thai (33%) and Chinese (27%). Heterosexual mode of HIV exposure was predominant (62%) and the median CD4 cell count at cART initiation was 130 cells/μL (IQR 40 to 228). Of the 5411 patients, there were 912 (17%) with virological failure. The median age was slightly lower at 34 years (IQR 29 to 40) and the median CD4 cell count was 97 cells/μL (IQR 25 to 200).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Virological failure | Immunological failure | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total patients included = 5411 (100%) | Total patients with VL failures = 912 (17%) | Total patients included = 5621 (100%) | Total patients with immunological failures = 391 (7%) | |

| Age at cART initiation (years) | Median = 35, IQR (29 to 41) | Median = 34, IQR (29 to 40) | Median = 35, IQR (29 to 41) | Median = 35, IQR (30 to 42) |

| ≤30 | 1616 (30) | 317 (35) | 1692 (30) | 105 (27) |

| 31 to 40 | 2302 (43) | 388 (43) | 2417 (43) | 168 (43) |

| 41 to 50 | 1040 (19) | 143 (16) | 1065 (19) | 71 (18) |

| >50 | 453 (8) | 64 (7) | 447 (80) | 47 (12) |

| Year of cART initiation | ||||

| <2003 | 699 (13) | 204 (22) | 627 (11) | 87 (22) |

| 2003 to 2005 | 1167 (22) | 221 (24) | 1186 (21) | 113 (29) |

| 2006 to 2009 | 2077 (38) | 279 (31) | 2207 (39) | 139 (36) |

| 2010 to 2014 | 1468 (27) | 208 (23) | 1601 (28) | 52 (13) |

| Pre‐cART age‐related comorbidities | ||||

| Age <50 years without comorbidities | 3559 (66) | 623 (68) | 3653 (65) | 260 (66) |

| Age <50 years with comorbidities | 1335 (25) | 219 (24) | 1449 (26) | 81 (21) |

| Age ≥50 years without comorbidities | 305 (6) | 41 (4) | 285 (5) | 27 (7) |

| Age ≥50 years with comorbidities | 212 (4) | 29 (3) | 234 (5) | 23 (6) |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 3839 (71) | 679 (74) | 3886 (69) | 316 (81) |

| Female | 1572 (29) | 233 (26) | 1735 (31) | 75 (19) |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Caucasian | 19 (0.4) | 2 (0.2) | 16 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) |

| Chinese | 1448 (27) | 312 (34) | 1284 (23) | 112 (29) |

| Filipino | 211 (4) | 24 (3) | 241 (4) | 8 (2) |

| Indian | 503 (9) | 87 (10) | 734 (13) | 55 (14) |

| Indonesian | 236 (4) | 68 (7) | 405 (7) | 53 (14) |

| Japanese | 222 (4) | 11 (1) | 68 (1) | 2 (10 |

| Khmer | 218 (4) | 22 (2) | 436 (8) | 50 (13) |

| Korean | 241 (4) | 60 (7) | 216 (4) | 12 (3) |

| Malay | 96 (2) | 29 (3) | 80 (1) | 8 (2) |

| Thai | 1788 (33) | 193 (21) | 1613 (29) | 59 (15) |

| Vietnamese | 401 (7) | 103 (11) | 502 (9) | 31 (8) |

| Other | 28 (1) | 1 (0.1) | 26 (0.5) | 0 (0) |

| HIV Exposure | ||||

| Heterosexual contact | 3355 (62) | 514 (56) | 3736 (66) | 290 (74) |

| Homosexual contact | 1385 (26) | 218 (24) | 1125 (20) | 39 (10) |

| Injecting drug use | 289 (5) | 103 (11) | 335 (6) | 38 (10) |

| Other/Unknown | 382 (7) | 77 (8) | 425 (8) | 24 (6) |

| Pre‐cART Viral Load (copies/mL) | Median = 98,000, IQR (27,700 to 290,000) | Median = 110,000, IQR (33,739 to 390,000) | Median = 99,180, IQR (27,574 to 290,000) | Median = 150,000, IQR (42,089 to 400,000) |

| <100,000 | 1570 (29) | 226 (25) | 1583 (28) | 68 (17) |

| ≥100,000 | 1529 (28) | 263 (29) | 1561 (28) | 99 (25) |

| Missing | 2312 (43) | 423 (46) | 2477 (44) | 224 (57) |

| Pre‐cART CD4 (cells/μL) | Median = 130, IQR (40 to 228) | Median = 97, IQR (28 to 200) | Median = 127, IQR (40 to 223) | Median = 30, IQR (12 to 73) |

| ≤50 | 1329 (25) | 266 (29) | 1642 (29) | 254 (65) |

| 51 to 100 | 636 (12) | 108 (12) | 801 (14) | 56 (14) |

| 101 to 200 | 1143 (21) | 177 (19) | 1456 (26) | 53 (14) |

| >200 | 1463 (27) | 182 (20) | 1722 (31) | 28 (7) |

| Missing | 840 (16) | 179 (20) | 0 | 0 |

| Initial cART category | ||||

| NRTI+NNRTI | 4389 (81) | 712 (78) | 4845 (86) | 343 (88) |

| NRTI+PI | 930 (17) | 182 (20) | 701 (12) | 45 (12) |

| Other combination | 92 (2) | 18 (2) | 75 (1) | 3 (1) |

| Hepatitis B co‐infection | ||||

| Negative | 3897 (72) | 622 (68) | 3903 (69) | 287 (73) |

| Positive | 457 (8) | 76 (8) | 463 (8) | 38 (10) |

| Not tested | 1057 (20) | 214 (23) | 1255 (22) | 66 (17) |

| Hepatitis C co‐infection | ||||

| Negative | 3635 (67) | 555 (61) | 3599 (64) | 272 (70) |

| Positive | 513 (9) | 126 (14) | 532 (9) | 49 (13) |

| Not tested | 1263 (23) | 231 (25) | 1490 (27) | 70 (18) |

| Prior AIDS diagnosis | ||||

| No | 3478 (64) | 534 (59) | 3571 (64) | 177 (45) |

| Yes | 1933 (36) | 378 (41) | 2050 (36) | 214 (55) |

| Ever smoked cigarettes | ||||

| No | 2138 (40) | 302 (33) | 2103 (37) | 106 (27) |

| Yes | 1535 (28) | 275 (30) | 1454 (26) | 109 (28) |

| Unknown | 1738 (32) | 335 (37) | 2064 (37) | 176 (45) |

| cART adherence | ||||

| Always ≥95% | 2357 (44) | 211 (23) | 2598 (46) | 60 (15) |

| Ever <95% | 253 (5) | 53 (6) | 270 (5) | 16 (4) |

| Not reported | 2801 (52) | 648 (71) | 2753 (49) | 315 (81) |

cART, combination antiretroviral therapy; IQR, interquartile range; VL, viral load.

The immunological failure analysis included 5621 patients in total, with a similar distribution of characteristics to the virological failure analysis. The median CD4 testing was two per patient per year (IQR 1 to 2). There were 391 patients (7%) who had an immunological failure. For each of the comorbidity groups, the median CD4 cell count at cART initiation was 116 cells/μL IQR (40 to 209) for age <50 without comorbidities, 157 cells/μL IQR (47 to 245) for age <50 with comorbidities, 116 cells/μL IQR (37 to 217) for age ≥50 years without comorbidities, and 164 cells/μL IQR (61 to 239) for age ≥50 years with comorbidities. Of the total patients in each comorbidity group, the number of patients initiating cART at CD4 cell count ≤200 cells/μL were 2662/3653 (73%), 894/1449 (62%), 198/285 (69%) and 145/234 (62%) respectively.

3.2. Virological failure

Of the 5411 patients included, 1858 (34%) had hypertension, 570 (11%) had diabetes mellitus, 2689 (50%) had dyslipidaemia and 353 (7%) had impaired renal function. There were 912 (17%) virological failures reported during 11,814.84 person‐years of follow‐up, with an incidence rate of 7.72 per 100 person‐years (/100PYS) (Table 2). The median time from cART initiation up to date of first virological failure or date of last VL test was three years (IQR 1.7 to 3.7). In the univariate analyses, having age‐related comorbidities (p < 0.001), cART adherence (p < 0.001), mode of HIV exposure (p < 0.001), pre‐ART VL (p = 0.029), pre‐ART CD4 (p < 0.001), initial ART regimen (p = 0.097), hepatitis C co‐infection (p = 0.055), prior AIDS diagnosis (p = 0.018) and ever smoked (p = 0.051) were associated with virological failure, and were thus entered into the multivariate model. Those with adherence <95% (HR = 0.15, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.10 to 0.21, p < 0.001) compared to adherence ≥95% and a higher CD4 count at start of cART (CD4 101 to 200 cells/μL, HR = 0.70, 95% CI 0.57 to 0.85; CD4 > 200 cells/μL, HR = 0.61, 95% CI 0.50 to 0.74, p < 0.001) were less likely to have virological failure. Those who acquired HIV through intravenous drug use were more likely to fail compared to a heterosexual mode of exposure (HR = 1.47, 95% CI 1.14 to 1.88, p = 0.003). Although not statistically significant, patients aged ≥50 years with comorbidities performed slightly better than the other three groups.

Table 2.

Factors associated with virological failure

| No patients | Follow‐up (years) | No of failures | Failure rate (per 100 person‐years) | Univariate | Multivariate | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | p‐value | HR | 95% CI | p‐value | |||||

| Total | 5411 | 11,814.84 | 912 | 7.72 | ||||||

| Age‐related comorbidities | <0.001 | 0.089 | ||||||||

| Age <50 years without comorbidities | ~ | 4420.08 | 441 | 9.98 | 1.75 | (1.31, 2.33) | <0.001 | 1.31 | (0.98, 1.74) | 0.070 |

| Age <50 years with comorbidities | ~ | 5883.95 | 381 | 6.48 | 1.19 | (0.90, 1.58) | 0.216 | 1.10 | (0.83, 1.45) | 0.514 |

| Age ≥50 years without comorbidities | ~ | 375.20 | 32 | 8.53 | 1.54 | (0.99, 2.40) | 0.054 | 1.11 | (0.71, 1.73) | 0.645 |

| Age ≥50 years with comorbidities | ~ | 1135.40 | 58 | 5.11 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| cART adherence | ||||||||||

| <95% | ~ | 175.01 | 42 | 24.00 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥95% | ~ | 5923.81 | 267 | 4.51 | 0.14 | (0.10, 0.20) | <0.001 | 0.15 | (0.10, 0.21) | <0.001 |

| Missing | ~ | 5716.03 | 603 | 10.55 | ||||||

| Sex | ||||||||||

| Male | 3839 | 8291.98 | 679 | 8.19 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Female | 1572 | 3522.86 | 233 | 6.61 | 0.97 | (0.83, 1.14) | 0.727 | 1.04 | (0.87, 1.23) | 0.686 |

| HIV exposure | <0.001 | 0.019 | ||||||||

| Heterosexual contact | 3355 | 7614.28 | 514 | 6.75 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Homosexual contact | 1385 | 3016.02 | 218 | 7.23 | 0.80 | (0.65, 0.99) | 0.041 | 1.01 | (0.81, 1.25) | 0.931 |

| Injecting drug use | 289 | 494.11 | 103 | 20.85 | 1.57 | (1.22, 2.01) | <0.001 | 1.47 | (1.14, 1.88) | 0.003 |

| Other/Unknown | 382 | 690.43 | 77 | 11.15 | 1.08 | (0.83, 1.42) | 0.550 | 1.19 | (0.90, 1.56) | 0.217 |

| Pre‐cART viral load (copies/μL) | ||||||||||

| <100,000 | 1570 | 3627.15 | 226 | 6.23 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥100,000 | 1529 | 3369.37 | 263 | 7.81 | 1.22 | (1.02, 1.46) | 0.029 | 1.05 | (0.87, 1.26) | 0.630 |

| Missing | 2312 | 4818.32 | 423 | 8.78 | ||||||

| Pre‐cART CD4 (cells/μL) | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| ≤50 | 1329 | 2804.11 | 266 | 9.49 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 51 to 100 | 636 | 1388.94 | 108 | 7.78 | 0.84 | (0.67, 1.06) | 0.139 | 0.83 | (0.66, 1.04) | 0.111 |

| 101 to 200 | 1143 | 2546.00 | 177 | 6.95 | 0.69 | (0.57, 0.84) | <0.001 | 0.70 | (0.57, 0.85) | <0.001 |

| >200 | 1463 | 3136.82 | 182 | 5.80 | 0.55 | (0.45, 0.67) | <0.001 | 0.61 | (0.50, 0.74) | <0.001 |

| Missing | 840 | 1938.96 | 179 | 9.23 | ||||||

| Initial cART category | 0.097 | 0.667 | ||||||||

| NRTI+NNRTI | 4389 | 9408.65 | 712 | 7.57 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| NRTI+PI | 930 | 2193.97 | 182 | 8.30 | 1.24 | (1.00, 1.52) | 0.048 | 0.98 | (0.79, 1.21) | 0.839 |

| Other combination | 92 | 212.22 | 18 | 8.48 | 1.34 | (0.83, 2.18) | 0.230 | 1.23 | (0.76, 1.99) | 0.409 |

| Hepatitis B co‐infection | ||||||||||

| Negative | 3897 | 8672.08 | 622 | 7.17 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Positive | 457 | 1023.49 | 76 | 7.43 | 0.98 | (0.77, 1.24) | 0.850 | 0.89 | (0.70, 1.14) | 0.355 |

| Not tested | 1057 | 2119.27 | 214 | 10.10 | ||||||

| Hepatitis C co‐infection | ||||||||||

| Negative | 3635 | 8261.66 | 555 | 6.72 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Positive | 513 | 980.51 | 126 | 12.85 | 1.24 | (1.00, 1.54) | 0.055 | 0.99 | (0.77, 1.25) | 0.908 |

| Not tested | 1263 | 2572.67 | 231 | 8.98 | ||||||

| Prior AIDS diagnosis | ||||||||||

| No | 3478 | 7593.57 | 534 | 7.03 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 1933 | 4221.28 | 378 | 8.95 | 1.18 | (1.03, 1.36) | 0.018 | 0.95 | (0.81, 1.10) | 0.490 |

| Ever smoked cigarettes | ||||||||||

| No | 2138 | 4891.63 | 302 | 6.17 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 1535 | 3466.78 | 275 | 7.93 | 1.18 | (1.00, 1.40) | 0.051 | 1.05 | (0.88, 1.24) | 0.597 |

| Unknown | 1738 | 3456.43 | 335 | 9.69 | ||||||

~ age‐related comorbidity and cART adherence are time‐updated variables. Missing values were included in the regression analyses; however, global p‐values were tested for heterogeneity excluding missing categories. Significant p‐values are highlighted in bold. Variables not associated with significant p‐values are presented in the final table adjusted for the variables with significant p‐values. CI, confidence interval; HR, Hazard ratio; NRTI, Nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; NNRTI, Non‐nucleoside reverse‐transcriptase inhibitor; PI, Protease inhibitor.

To determine the effects of the year of cART initiation on virological failure and to avoid collinearity with the adherence variable, we included year of cART initiation in the multivariate model without adjusting for adherence. As expected, later years of cART initiation were associated with decreased hazard for failure (2003 to 2005: HR = 0.82, 95% CI 0.67 to 1.00, p = 0.052; 2006 to 2009: HR = 0.50, 95% CI 0.41 to 0.62, p < 0.001; and 2010 to 2014: HR = 0.38, 95% CI 0.29 to 0.49, p < 0.001) compared to years prior to 2003.

3.3. Immunological failure

The rate of immunological failure was 2.75/100 PYS (Table 3). Of the 5621 patients included, there were 391 (7%) patients who experienced immunological failure during 14,196 person‐years of follow‐up. The median time from cART initiation was 3.5 years (IQR 2.5 to 3.8). There were 2105 (37%) patients with hypertension, 607 (11%) with diabetes, 2748 (49%) with dyslipidaemia and 404 (7%) with impaired renal function.

Table 3.

Factors associated with immunological failure

| No patients | Follow‐up (years) | No of failures | Failure rate (per 100 person‐years) | Univariate | Multivariate | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | p‐value | HR | 95% CI | p‐value | |||||

| Total | 5621 | 14,196 | 391 | 2.75 | ||||||

| Age‐related comorbidities | 0.003 | 0.005 | ||||||||

| Age <50 years without comorbidities | ~ | 5310 | 185 | 3.48 | 0.88 | (0.62, 1.25) | 0.480 | 0.66 | (0.46, 0.95) | 0.025 |

| Age <50 years with comorbidities | ~ | 7243 | 152 | 2.10 | 0.62 | (0.43, 0.88) | 0.007 | 0.54 | (0.38, 0.76) | 0.001 |

| Age ≥50 years without comorbidities | ~ | 365 | 13 | 3.56 | 1.01 | (0.54, 1.91) | 0.968 | 0.74 | (0.39, 1.40) | 0.354 |

| Age ≥50 years with comorbidities | ~ | 1279 | 41 | 3.21 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| cART adherence | ||||||||||

| <95% | ~ | 222 | 14 | 6.30 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥95% | ~ | 7232 | 80 | 1.11 | 0.15 | (0.09, 0.28) | <0.001 | 0.16 | (0.09, 0.29) | <0.001 |

| Missing | ~ | 6742 | 297 | 4.41 | ||||||

| Sex | ||||||||||

| Male | 3886 | 9644 | 316 | 3.28 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Female | 1735 | 4552 | 75 | 1.65 | 0.51 | (0.40, 0.67) | <0.001 | 0.60 | (0.46, 0.79) | <0.001 |

| HIV exposure | <0.001 | 0.022 | ||||||||

| Heterosexual contact | 3736 | 9654 | 290 | 3.00 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Homosexual contact | 1125 | 2764 | 39 | 1.41 | 0.36 | (0.24, 0.55) | <0.001 | 0.52 | (0.34, 0.79) | 0.002 |

| Injecting drug use | 335 | 761 | 38 | 5.00 | 1.12 | (0.75, 1.67) | 0.570 | 0.86 | (0.57, 1.31) | 0.490 |

| Other/Unknown | 425 | 1017 | 24 | 2.36 | 0.69 | (0.44, 1.08) | 0.106 | 0.76 | (0.48, 1.21) | 0.248 |

| Pre‐cART viral load (copies/mL) | ||||||||||

| <100,000 | 1583 | 4023 | 68 | 1.69 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥100,000 | 1561 | 3944 | 99 | 2.51 | 1.37 | (1.00, 1.87) | 0.051 | 0.84 | (0.61, 1.16) | 0.293 |

| Missing | 2477 | 6229 | 224 | 3.60 | ||||||

| Pre‐cART CD4 (cells/μL) | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| ≤50 | 1642 | 3974 | 254 | 6.39 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 51 to 100 | 801 | 2046 | 56 | 2.74 | 0.44 | (0.33, 0.59) | <0.001 | 0.45 | (0.34, 0.60) | <0.001 |

| 101 to 200 | 1456 | 3810 | 53 | 1.39 | 0.21 | (0.16, 0.29) | <0.001 | 0.24 | (0.17, 0.32) | <0.001 |

| >200 | 1722 | 4366 | 28 | 0.64 | 0.09 | (0.06, 0.14) | <0.001 | 0.11 | (0.07, 0.17) | <0.001 |

| Initial cART category | 0.614 | 0.923 | ||||||||

| NRTI+NNRTI | 4845 | 12,163 | 343 | 2.82 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| NRTI+PI | 701 | 1851 | 45 | 2.43 | 1.20 | (0.82, 1.77) | 0.343 | 0.93 | (0.63, 1.36) | 0.708 |

| Other combination | 75 | 183 | 3 | 1.64 | 0.91 | (0.28, 2.90) | 0.872 | 0.89 | (0.28, 2.86) | 0.845 |

| Hepatitis B co‐infection | ||||||||||

| Negative | 3903 | 10,022 | 287 | 2.86 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Positive | 463 | 1209 | 38 | 3.14 | 1.20 | (0.86, 1.69) | 0.286 | 1.01 | (0.71, 1.42) | 0.977 |

| Not tested | 1255 | 2965 | 66 | 2.23 | ||||||

| Hepatitis C co‐infection | ||||||||||

| Negative | 3599 | 9324 | 272 | 2.92 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Positive | 532 | 1306 | 49 | 3.75 | 1.11 | (0.79, 1.55) | 0.555 | 0.90 | (0.61, 1.34) | 0.613 |

| Not tested | 1490 | 3565 | 70 | 1.96 | ||||||

| Prior AIDS diagnosis | ||||||||||

| No | 3571 | 9083 | 177 | 1.95 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 2050 | 5113 | 214 | 4.19 | 1.78 | (1.44, 2.19) | <0.001 | 0.85 | (0.68, 1.07) | 0.164 |

| Ever smoked cigarettes | ||||||||||

| No | 2103 | 5531 | 106 | 1.92 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 1454 | 3845 | 109 | 2.84 | 1.23 | (0.93, 1.61) | 0.142 | 0.87 | (0.65, 1.17) | 0.366 |

| Unknown | 2064 | 4820 | 176 | 3.65 | ||||||

~ age‐related comorbidity and cART adherence are time‐updated variables. Missing values were included in the regression analyses, however global p‐values were tested for heterogeneity excluding missing categories. Significant p‐values are highlighted in bold. Variables not associated with significant p‐values are presented in the final table adjusted for the variables with significant p‐values. CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; NRTI, Nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; NNRTI, Non‐nucleoside reverse‐transcriptase inhibitor; PI, Protease inhibitor.

In the multivariate analyses, those aged <50 years without comorbidities (HR = 0.66, 95% CI 0.46 to 0.95, p = 0.025) and aged <50 years with comorbidities (HR = 0.54, 95% CI 0.38 to 0.76, p = 0.001) were less likely to develop immunological failure compared to those patients aged ≥50 years with comorbidities. Other factors associated with a reduction in hazard for failure were cART adherence ≥95% (HR = 0.16, 95% CI 0.09 to 0.29, p < 0.001) compared to adherence <95%, female sex (HR = 0.60, 95% CI 0.46 to 0.79, p < 0.001), homosexual mode of exposure (HR = 0.52, 95% CI 0.34 to 0.79, p = 0.002) compared to heterosexual mode of exposure, and higher CD4 count (CD4 51 to 100 cells/μL: HR = 0.45, 95% CI 0.34 to 0.60; CD4 101 to 200 cells/μL: HR = 0.24, 95% CI 0.17 to 0.32; and CD4 > 200 cells/μL: HR = 0.11, 95% CI 0.07 to 0.16, all p < 0.001) compared to CD4 ≤ 50 cells/μL.

When year of cART initiation was included in the final multivariate model in place of the adherence variable, we saw decreasing hazard for failure in later years (2003 to 2005: HR = 0.74, 95% CI 0.54 to 1.01, p = 0.058; 2006 to 2009: HR = 0.56, 95% CI 0.41 to 0.77, p < 0.001; and 2010 to 2014: HR = 0.28 95% CI 0.18 to 0.44, p < 0.001) compared to years prior to 2003.

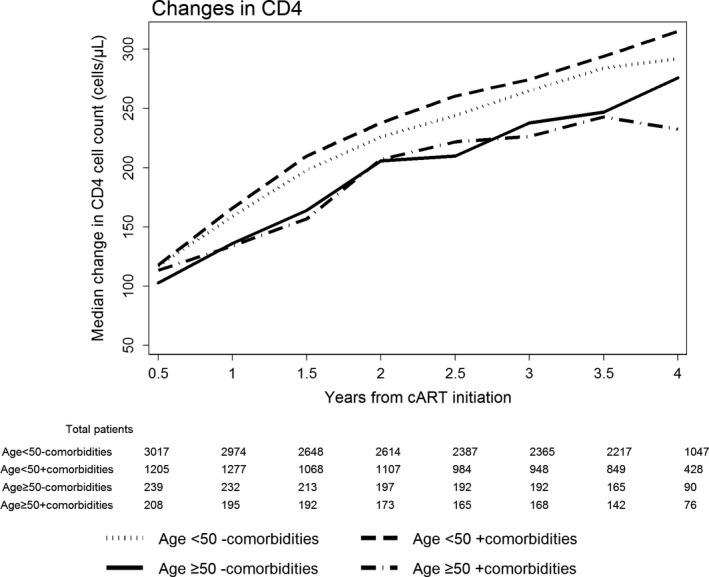

To examine patterns of CD4 changes in our patient group, we plotted the median change in CD4 cell count for each of our comorbidities group. Figure 1 shows median CD4 increases at each six‐month interval, categorized by comorbidity and age at cART initiation. Patients aged ≥50 years were shown to have slower increases in CD4 cell counts compared to patients <50 years. At four years from cART initiation, patients aged <50 years with comorbidities showed the biggest median change in CD4 cell count, while the median change in the CD4 cell count was the smallest for patients aged ≥50 years with comorbidities. The small decrease in CD4 count in the age ≥50 years with the comorbidities group at the fourth year could be attributed to the small sample size present at that time point (76 patients).

Figure 1. Median changes in CD4 cell count from cART initiation.

3.4. Sensitivity analyses

Factors associated with virological failure in males and females are shown in Table S1. cART adherence <95% was associated with failure in both sexes; however, higher CD4 cell count at cART initiation was associated with reduced hazard for failure in males, but this was not statistically significant in females. Table S2 reports risk factors for immunological failure in males and females. Age <50 with or without comorbidities, cART adherence ≥95%, and higher pre‐cART CD4 cell count were associated with reductions in HRs in both males and females. Females who have never smoked were less likely to develop immunological failure, however this association was not evident in males. Overall the effects of the age‐related comorbidity variable in the main analyses and in the sensitivity analyses remained similar suggesting that regardless of sex, those aged ≥50 years with comorbidities had worse immunological outcomes than their younger counterpart either with or without comorbidities.

4. Discussion

We hypothesized that age‐associated comorbidities may worsen therapeutic outcomes of cART, because of the risk of polypharmacy and additive negative effects of these health conditions. However, our results showed that presence of age‐associated comorbidities did not affect virological outcomes of cART, and patients <50 years with comorbidities had better immunological outcomes compared with patients ≥50 years with comorbidities.

The prevalence of age‐related comorbidities in this study population was similar to the results from other studies. The prevalence of dyslipidaemia among HIV‐positive populations differs depending on the methodology and patient population studied, ranging from 20% to 80% 25. According to the Swiss HIV Cohort study, the prevalence of hypertension and diabetes mellitus were 56.3% and 4.1% respectively 1. In that study, the eGFR (calculated by the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study equation) of older HIV‐positive participants was lower than that of younger HIV‐positive patients. HIV‐positive patients may have greater risk of non‐infectious comorbidities than the general population, because of the effects of HIV itself, prevalent risk factors, and antiretroviral medications 26. The treatment of older HIV‐positive patients is complicated by pre‐existing comorbid conditions, including cardiovascular, hepatic and metabolic complications that may be exacerbated by the effects of HIV infection per se, immunodeficiency and metabolic and other adverse effects of combination antiretroviral therapy 27, 28. Synergistic deleterious effects of chronic immune activation on the course of HIV infection with the immune senescence of ageing may promote this accelerated course 27.

A study from Italy showed that age‐related non‐infectious comorbidities were more common among HIV‐positive patients than in the general population 26. They performed a case–control study involving ART‐experienced HIV‐positive patients treated from 2002 through to 2009. These patients were compared with age‐, sex‐ and race‐matched adult controls from the general population. The prevalence of hypertension, renal failure and diabetes mellitus of the HIV group <50 years were 13.2%, 3.78% and 6.17% respectively. The rates were greater than the general population.

Multiple studies have demonstrated that, despite successful ART and viral suppression, immune recovery is less robust with increasing age, highlighting the importance of early diagnosis and treatment of HIV 16, 29, 30, 31, 32. Consistent with previous studies, patients aged ≥50 years with comorbidities in our study had a greater rate of immunological failure compared to patients <50 years with comorbidities. As shown in Figure 1, patients aged ≥50 years were shown to have slower increases in CD4 cell counts compared to patients <50 years. This is consistent with previous studies as well. The poorer immune recovery in older populations could be caused in part by decreased thymic function in these groups 31. In addition, late diagnosis can be more frequent in older populations, and low baseline CD4 cells might affects the immunological responses. However, in our study cohort, the highest proportion of those who initiated ART late was in the age <50 years without co‐morbidities group, and the median CD4 cell count at baseline was lowest for those age <50 years without co‐morbidities and those age ≥50 years without co‐morbidities. Nevertheless, older patients derive substantial benefit from cART despite having a less robust immunological response than expected given their adherence to therapy and excellent virological responses 27. cART provides substantial benefit for older and younger HIV‐positive patients 33, and older patients are more likely to achieve virological control of HIV replication 34, 35 and less likely to develop subsequent virological breakthrough 34, findings that correlate with better adherence to therapy by older patients 35. Consistent with previous studies, our study showed that older patients had similar virological outcomes compared with younger patients.

Overall, the effects of the age‐related comorbidity variables in the main analyses and in the sensitivity analyses remained similar, suggesting that regardless of sex, those aged ≥50 years with comorbidities had worse immunological outcomes than their younger counterparts either with or without comorbidities.

The limitations of the study included the presence missing data. As TAHOD is an observational cohort, data collection depends entirely on the standard of care at each individual site. Patients with good clinic attendance may have more frequent comorbidity testing which may lead to earlier or more frequent diagnosis of a comorbidity. Patients with poor clinic attendance may also have these comorbidities present but not detected. As the cohort does not impose specific study procedures or treatment interventions, the study results should be interpreted with this in mind. The cutoff points for virologic and immunologic failures may not necessarily be relevant for individual patient management, but the failure definition is in line with current WHO guidelines for general clinical practice. In addition, the comorbidity variable was defined according to the availability of our data. We were not able to assess the effects of other comorbidities, as we were limited to the data variables being captured in our cohort. Furthermore, our cohort sites are generally urban referral centres. Patients are selected for enrolment based on the likelihood of remaining in care. Therefore, the generalizability of the reported findings is limited.

5. Conclusions

Age associated comorbidities did not affect virological outcomes of cART, and older patients with comorbidities were more likely to experience immunological failure compared to those aged <50 years.

Competing interests

The authors do not have any competing interest to declare.

Authors’ contributions

MYA, AJ and JYC contributed to the concept development. SK, VK, TTP, RC, AA, NK, WWW, SK, SP, KVN, MPL, AK, FJ, RD, TPM, EY, OTN, BLHS, JT, WR and JYC contributed data for the analysis. AJ performed the statistical analysis. MYA wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors commented on the draft manuscript and approved of the final manuscript.

TAHOD Study members

PS Ly* and V Khol, National Centre for HIV/AIDS, Dermatology & STDs, Phnom Penh, Cambodia; FJ Zhang* †, HX Zhao and N Han, Beijing Ditan Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing, China; MP Lee*, PCK Li, W Lam and YT Chan, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Hong Kong SAR; N Kumarasamy*, S Saghayam and C Ezhilarasi, Chennai Antiviral Research and Treatment Clinical Research Site (CART CRS), YRGCARE Medical Centre, VHS, Chennai, India; S Pujari*, K Joshi, S Gaikwad and A Chitalikar, Institute of Infectious Diseases, Pune, India; S Sangle*, V Mave and I Marbaniang, BJ Government Medical College and Sassoon General Hospital, Pune, India; TP Merati*, DN Wirawan and F Yuliana, Faculty of Medicine Udayana University & Sanglah Hospital, Bali, Indonesia; E Yunihastuti*, D Imran and A Widhani, Faculty of Medicine Universitas Indonesia ‐ Dr. Cipto Mangunkusumo General Hospital, Jakarta, Indonesia; J Tanuma*, S Oka and T Nishijima, National Center for Global Health and Medicine, Tokyo, Japan; JY Choi*, Na S and JM Kim, Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Internal Medicine, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, South Korea; BLH Sim*, YM Gani, and R David, Hospital Sungai Buloh, Sungai Buloh, Malaysia; A Kamarulzaman*, SF Syed Omar, S Ponnampalavanar and I Azwa, University Malaya Medical Centre, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia; R Ditangco*, MK Pasayan and ML Mationg, Research Institute for Tropical Medicine, Muntinlupa City, Philippines; WW Wong*, WW Ku and PC Wu, Taipei Veterans General Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan; OT Ng* ‡, PL Lim, LS Lee and Z Ferdous, Tan Tock Seng Hospital, Singapore; A Avihingsanon*, S Gatechompol, P Phanuphak and C Phadungphon, HIV‐NAT/Thai Red Cross AIDS Research Centre, Bangkok, Thailand; S Kiertiburanakul*, A Phuphuakrat, L Chumla and N Sanmeema, Faculty of Medicine Ramathibodi Hospital, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand; R Chaiwarith*, T Sirisanthana, W Kotarathititum and J Praparattanapan, Research Institute for Health Sciences, Chiang Mai, Thailand; S Khusuwan*, P Kantipong and P Kambua, Chiangrai Prachanukroh Hospital, Chiang Rai, Thailand; W Ratanasuwan* and R Sriondee, Faculty of Medicine, Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand; KV Nguyen*, HV Bui, DTH Nguyen and DT Nguyen, National Hospital for Tropical Diseases, Hanoi, Vietnam; CD Do*, AV Ngo and LT Nguyen, Bach Mai Hospital, Hanoi, Vietnam; AH Sohn*, JL Ross* and B Petersen, TREAT Asia, amfAR ‐ The Foundation for AIDS Research, Bangkok, Thailand; MG Law*, A Jiamsakul* and D Rupasinghe, The Kirby Institute, UNSW Sydney, NSW, Australia.

* TAHOD Steering Committee member; † Steering Committee Chair; ‡ co‐Chair

Supporting information

Table S1. Multivariate analyses for factors associated with virological failure in males and females

Table S2. Multivariate analyses for factors associated with immunological failure in males and females

Acknowledgements

Funding

The TREAT Asia HIV Observational Database is an initiative of TREAT Asia, a programme of amfAR, The Foundation for AIDS Research, with support from the U.S. National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, the National Cancer Institute, the National Institute of Mental Health, and the National Institute on Drug Abuse, as part of the International Epidemiology Databases to Evaluate AIDS (IeDEA; U01AI069907). The Kirby Institute is funded by the Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing, and is affiliated with the Faculty of Medicine, UNSW Sydney. The content of this publication is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of any of the governments or institutions mentioned above.

Ahn, M. Y. , Jiamsakul, A. , Khusuwan, S. , Khol, V. , Thuy, T. P. , Chaiwarith, R. , Avihingsanon, A. , Kumarasamy, N. , Wong, W. W. , Kiertiburanakul, S. , Pujari, S. , Nguyen, K. V. , Lee, M. P. , Kamarulzaman, A. , Zhang, F. , Ditangco, R. , Merati, T. P. , Yunihastuti, E. , Ng, O. T. , Sim, B. L. H. , Tanuma, J. , Ratanasuwan, W. , Ross, J. and Choi, J. Y. on behalf of IeDEA Asia‐Pacific . The influence of age‐associated comorbidities on responses to combination antiretroviral therapy in older people living with HIV. J Int AIDS Soc. 2019;22:e25228

References

- 1. Weber R, Ruppik M, Rickenbach M, Spoerri A, Furrer H, Battegay M, et al. Decreasing mortality and changing patterns of causes of death in the Swiss HIV Cohort Study. HIV Med. 2013;14(4):195–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wada N, Jacobson LP, Cohen M, French A, Phair J, Munoz A. Cause‐specific life expectancies after 35 years of age for human immunodeficiency syndrome‐infected and human immunodeficiency syndrome‐negative individuals followed simultaneously in long‐term cohort studies, 1984‐2008. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;177(2):116–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Eyawo O, Franco‐Villalobos C, Hull MW, Nohpal A, Samji H, Sereda P, et al. Changes in mortality rates and causes of death in a population‐based cohort of persons living with and without HIV from 1996 to 2012. BMC Infect Dis. 2017;17(1):174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS . The Gap Report. 2014. Sep [cited 2015 May 20]. Available from: http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/UNAIDS_Gap_report_en.pdf

- 5. Chastain DB, Henderson H, Stover KR. Epidemiology and management of antiretroviral‐associated cardiovascular disease. Open AIDS J. 2015;9:23–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Maggi P, Di Biagio A, Rusconi S, Cicalini S, D'Abbraccio M, d'Ettorre G, et al. Cardiovascular risk and dyslipidemia among persons living with HIV: a review. BMC Infect Dis. 2017;17(1):551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Schouten J, Wit FW, Stolte IG, Kootstra NA, van der Valk M, Geerlings SE, et al. Cross‐sectional comparison of the prevalence of age‐associated comorbidities and their risk factors between HIV‐infected and uninfected individuals: the AGEhIV cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(12):1787–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Francesco D, Verboeket SO, Underwood J, Bagkeris E, Wit FW, Mallon PWG, et al. Patterns of co‐occurring comorbidities in people living with HIV. Open Forum Infect Dis 2018;5(11):ofy272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gleason LJ, Luque AE, Shah K. Polypharmacy in the HIV‐infected older adult population. Clin Interv Aging. 2013;8:749–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ware D, Palella FJ, Chew KW, Friedman MR, D'Souza G, Ho K, et al. Prevalence and trends of polypharmacy among HIV‐positive and ‐negative men in the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study from 2004 to 2016. PLoS One. 2018;13(9):e0203890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Marzolini C, Back D, Weber R, Furrer H, Cavassini M, Calmy A, et al. Ageing with HIV: medication use and risk for potential drug‐drug interactions. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66(9):2107–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Park MS, Yang YM, Kim JS, Choi EJ. Comparative study of antiretroviral drug regimens and drug‐drug interactions between younger and older HIV‐infected patients at a tertiary care teaching hospital in South Korea. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2018;14:2229–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hinkin CH, Hardy DJ, Mason KI, Castellon SA, Durvasula RS, Lam MN, et al. Medication adherence in HIV‐infected adults: effect of patient age, cognitive status, and substance abuse. AIDS. 2004;18 Suppl 1:S19–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Barclay TR, Hinkin CH, Castellon SA, Mason KI, Reinhard MJ, Marion SD, et al. Age‐associated predictors of medication adherence in HIV‐positive adults: health beliefs, self‐efficacy, and neurocognitive status. Health Psychol. 2007;26(1):40–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Marzolini C, Elzi L, Gibbons S, Weber R, Fux C, Furrer H, et al. Prevalence of comedications and effect of potential drug‐drug interactions in the Swiss HIV cohort study. Antivir Ther. 2010;15(3):413–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Althoff KN, Justice AC, Gange SJ, Deeks SG, Saag MS, Silverberg MJ, et al. Virologic and immunologic response to HAART, by age and regimen class. AIDS. 2010;24(16):2469–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ghidei L, Simone MJ, Salow MJ, Zimmerman KM, Paquin AM, Skarf LM, et al. Aging, antiretrovirals, and adherence: a meta analysis of adherence among older HIV‐infected individuals. Drugs Aging. 2013;30(10):809–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sheppard DP, Weber E, Casaletto KB, Avci G, Woods SP, Program HNR. Pill burden influences the association between time‐based prospective memory and antiretroviral therapy adherence in younger but not older HIV‐infected adults. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2016;27(5):595–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Duda SN, Farr AM, Lindegren ML, Blevins M, Wester CW, Wools‐Kaloustian K, et al. Characteristics and comprehensiveness of adult HIV care and treatment programmes in Asia‐Pacific, sub‐Saharan Africa and the Americas: results of a site assessment conducted by the International epidemiologic Databases to Evaluate AIDS (IeDEA) Collaboration. J Int AIDS Soc. 2014;17:19045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zhou J, Kumarasamy N, Ditangco R, Kamarulzaman A, Lee CK, Li PC, et al. The TREAT Asia HIV observational database: baseline and retrospective data. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;38(2):174–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. WHO . Consolidated guidelines on THE USE OF ANTIRETROVIRAL DRUGS FOR TREATING AND PREVENTING HIV INFECTION recommndations for a public health approach 2016; second edition. 2016. [cited 2018 March 1]. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/208825/1/9789241549684_eng.pdf?ua=1 [PubMed]

- 22. Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL Jr, et al. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA. 2003;289(19):2560–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus . Diabetes Care. 2010;33 Suppl 1:S62–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation 2002;106(25):3143–421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Troll JG. Approach to dyslipidemia, lipodystrophy, and cardiovascular risk in patients with HIV infection. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2011;13(1):51–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Guaraldi G, Orlando G, Zona S, Menozzi M, Carli F, Garlassi E, et al. Premature age‐related comorbidities among HIV‐infected persons compared with the general population. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53(11):1120–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kirk JB, Goetz MB. Human immunodeficiency virus in an aging population, a complication of success. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(11):2129–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pelchen‐Matthews A, Ryom L, Borges AH, Edwards S, Duvivier C, Stephan C, et al. Aging and the evolution of comorbidities among HIV‐positive individuals in a European cohort. AIDS. 2018;32(16):2405–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Vinikoor MJ, Joseph J, Mwale J, Marx MA, Goma FM, Mulenga LB, et al. Age at antiretroviral therapy initiation predicts immune recovery, death, and loss to follow‐up among HIV‐infected adults in urban Zambia. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2014;30(10):949–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Grabar S, Kousignian I, Sobel A, Le Bras P, Gasnault J, Enel P, et al. Immunologic and clinical responses to highly active antiretroviral therapy over 50 years of age. Results from the French hospital database on HIV. AIDS 2004;18(15):2029–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Viard JP, Mocroft A, Chiesi A, Kirk O, Roge B, Panos G, et al. Influence of age on CD4 cell recovery in human immunodeficiency virus‐infected patients receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy: evidence from the EuroSIDA study. J Infect Dis. 2001;183(8):1290–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Semeere AS, Lwanga I, Sempa J, Parikh S, Nakasujja N, Cumming R, et al. Mortality and immunological recovery among older adults on antiretroviral therapy at a large urban HIV clinic in Kampala, Uganda. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;67(4):382–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Perez JL, Moore RD. Greater effect of highly active antiretroviral therapy on survival in people aged > or =50 years compared with younger people in an urban observational cohort. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36(2):212–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mussini C, Manzardo C, Johnson M, Monforte A, Uberti‐Foppa C, Antinori A, et al. Patients presenting with AIDS in the HAART era: a collaborative cohort analysis. AIDS. 2008;22(18):2461–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Silverberg MJ, Leyden W, Horberg MA, DeLorenze GN, Klein D, Quesenberry CP Jr. Older age and the response to and tolerability of antiretroviral therapy. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(7):684–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Multivariate analyses for factors associated with virological failure in males and females

Table S2. Multivariate analyses for factors associated with immunological failure in males and females