While both type I and type II IFNs are involved in the control of herpesvirus infections in the human host, to our knowledge, their relative contributions to the restriction of viral replication and spread have not been assessed. We report that IFN-γ has more potent activity than IFN-α against VZV. Findings from this comparative analysis show that the IFN-α–IRF9 axis functions as a first line of defense to delay the onset of viral replication and spread, whereas the IFN-γ–IRF1 axis has the capacity to block the infectious process. Our findings underscore the importance of IRFs in IFN regulation of herpesvirus infection and account for the clinical experience of the initial control of VZV skin infection attributable to IFN-α production, together with the requirement for induction of adaptive IFN-γ-producing VZV-specific T cells to resolve the infection.

KEYWORDS: IRF1 mediates the inhibitory effects of interferon gamma on VZV, IRF9 mediates the action of interferon alpha on VZV, interferon gamma abrogates VZV replication, VZV innate immune control, interferon alpha delays onset of VZV spread

ABSTRACT

Both type I and type II interferons (IFNs) have been implicated in the host defense against varicella-zoster virus (VZV), a common human herpesvirus that causes varicella and zoster. The purpose of this study was to compare their contributions to the control of VZV replication, to identify the signaling pathways that are critical for mediating their antiviral activity, and to define the mechanisms by which the virus counteracts their effects. Gamma interferon (IFN-γ) was much more potent than IFN-α in blocking VZV infection, which was associated with a differential induction of the interferon regulatory factor (IRF) proteins IRF1 and IRF9, respectively. These observations account for the clinical experience that while the formation of VZV skin lesions is initially controlled by local immunity, adaptive virus-specific T cell responses are required to prevent life-threatening VZV infections.

IMPORTANCE While both type I and type II IFNs are involved in the control of herpesvirus infections in the human host, to our knowledge, their relative contributions to the restriction of viral replication and spread have not been assessed. We report that IFN-γ has more potent activity than IFN-α against VZV. Findings from this comparative analysis show that the IFN-α–IRF9 axis functions as a first line of defense to delay the onset of viral replication and spread, whereas the IFN-γ–IRF1 axis has the capacity to block the infectious process. Our findings underscore the importance of IRFs in IFN regulation of herpesvirus infection and account for the clinical experience of the initial control of VZV skin infection attributable to IFN-α production, together with the requirement for induction of adaptive IFN-γ-producing VZV-specific T cells to resolve the infection.

INTRODUCTION

Herpesviruses are large DNA viruses that infect both vertebrates and nonvertebrates and that can cause a wide spectrum of diseases in susceptible hosts. Among the human herpesviruses, varicella-zoster virus (VZV) differs from the other alphaherpesviruses, herpes virus 1 (HSV-1) and HSV-2, in its ability to infect tonsillar lymphocytes for transport of the virus to the skin (1). All three viruses establish latency in sensory ganglion neurons. The life cycle of VZV in the individual and its persistence in the human population depend on cutaneous lesion formation and the release of infectious virus from sites of replication in skin during primary infection (varicella) and reactivations from latency (zoster). Like other viruses, the capacity of VZV to infect the human host requires evasion and manipulation of innate and adaptive immune mechanisms. Type I and II interferons (IFNs) have been widely investigated for their roles as agents interfering with viral pathogens. Our studies of VZV have documented the dynamic interaction between the type I interferon (alpha-beta interferon [IFN-αβ]) responses of dermal and epidermal cells and the progression of skin lesions using human tissue xenografts in the severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) mouse model of VZV pathogenesis (2). Many reports have demonstrated that deficiencies of VZV-specific CD4 T cell responses, which impair the production of type II interferon (IFN-γ) and other cytokines, are associated with progressive varicella (3) and susceptibility to zoster (4).

Signal transduction by IFN-αβ and IFN-γ is mediated by distinct multiprotein complexes of interferon regulatory factor (IRF) and signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) family proteins that play a critical role in the immune regulation of many DNA and RNA viral pathogens (5–7). Typically, signaling by IFN-αβ, secreted by most somatic cells, triggers formation of the ISGF3 complex, made up of IRF9, phosphorylated STAT1 (pSTAT1), and pSTAT2 (8). This complex elicits the transcription of hundreds of different IFN-stimulated genes (ISGs) and the synthesis and secretion of their respective gene products (9). In contrast, signaling via IFN-γ, secreted most commonly by cells of the immune system as part of the adaptive immune response, requires IRF1 and pSTAT1 (8, 10).

Here, we identify quantitative differences in the host defense provided by type I and II IFNs against VZV infection of primary human fibroblasts. While exposure to IFN-α delayed VZV replication and spread, IFN-γ completely inhibited virus replication. Stimulation by IFN-α and IFN-γ created unique intracellular environments, as shown by RNA transcriptome profiles. In investigating the mechanisms involved in the differential effects of type I and type II IFNs, we found that IRF9 is critical for the IFN-α-mediated host cell defense against VZV, whereas the antiviral activity of IFN-γ depends on IRF1. The potent inhibition of VZV by IFN-γ compared to the level of inhibition by IFN-α accounts for the clinical experience that while the formation of skin lesions is initially controlled by local immunity, adaptive VZV-specific T cell responses are required to prevent life-threatening VZV infections.

RESULTS

Differential effects of type I and type II IFNs on VZV infection.

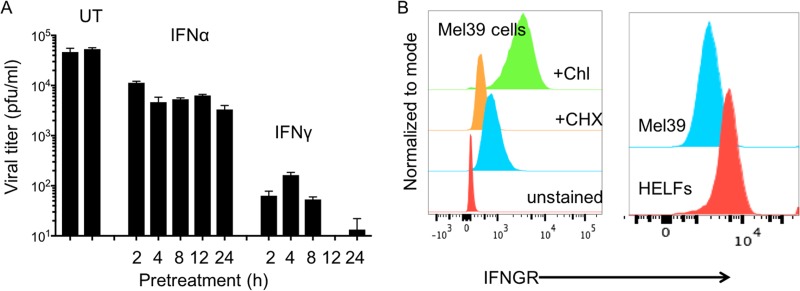

VZV replication and cell-cell spread were compared in human embryonic lung fibroblasts (HELFs) that were treated with IFN-α and IFN-γ prior to or after VZV inoculation. Although IFN-α pretreatment (104 U/ml) inhibited replication, VZV titers were only 1 log lower than the titers in untreated HELFs, and increasing the duration of IFN-α pretreatment from 2 h to 24 h did not further diminish virus recovery (Fig. 1A). In contrast, IFN-γ pretreatment (200 U/ml) dramatically reduced VZV titers by 3 to 4 logs compared to those in IFN-α-pretreated and untreated control HELFs. IFN-γ pretreatment also had a duration-related effect, progressing from a 2-log reduction in VZV titers with 2 h of exposure to low or undetectable titers when cell responses were induced for 12 h or 24 h before VZV inoculation. Expression of IFN-γ receptor (IFNGR) on HELFs and melanoma (Mel39) cells was shown by flow cytometry analysis (Fig. 1B).

FIG 1.

Type I and type II IFNs differentially regulate the onset of VZV infection. (A) HELFs were pretreated with either IFN-α (104 U/ml) or IFN-γ (200 U/ml) for the indicated times, IFNs were removed, and monolayers were inoculated with VZV (400 PFU/ml). The bar graph shows the viral titers in samples collected at 10 days from wells that were untreated (UT) or exposed to IFN-α or IFN-γ for 2 to 24 h before inoculation. Virus titers were assayed in triplicate, and the error bars demonstrate the standard error of the mean. The data are representative of those from two similar independent experiments. (B) Determination of IFN-γ receptor (IFNGR) expression on primary fibroblasts (HELFs) and melanoma (Mel39) cells. Single-cell suspensions of the two cell types were incubated with phycoerythrin-IFNGR antibody and tested by flow cytometry. To confirm antibody specificity, Mel39 cells were treated with cycloheximide (CHX) to block protein synthesis and chloroquine (Chl) to block the lysosomal degradation of IFNGR.

Removing IFN-α after 2 h or 24 h of pretreatment, at the time of VZV inoculation, reversed its inhibitory effect on replication and allowed more cell-cell spread, as shown by the formation of larger plaques, visible when the monolayers were directly stained with the anti-VZV antibody reagent (Fig. 2A and B). In contrast, VZV spread remained blocked when IFN-γ was removed after 2 h or 24 h of pretreatment prior to inoculation (Fig. 2A). In addition, increasing the VZV inoculum from low (400 PFU/ml) to high (2,000 PFU/ml) enhanced the capacity of the virus to infect cells that were pretreated with IFN-α for 2 h but not those that were pretreated with IFN-γ (Fig. 2A and C). The effect of IFN-α pretreatment was dose dependent, with 103 U/ml having less of an effect than 104 and 105 U/ml, whereas no plaque formation was detected when HELFs were pretreated with IFN-γ at a low dose of 20 U/ml compared to a higher dose of 100 or 200 U/ml (Fig. 2D). In contrast, when IFNs were added 48 h after VZV inoculation, some viral replication was detected at 72 h and 96 h in both IFN-α- and IFN-γ-treated cells. Nevertheless, VZV titers were reduced compared to those in untreated cells if replication was allowed to progress for 48 h before adding IFN-α or IFN-γ, and VZV replication was even more restricted by IFNs added posttreatment when the inoculum was low (400 PFU/ml) than when the inoculum was high (2,000 PFU/ml) (Fig. 2E). We also investigated IFN-γ effects when the time of addition was varied from 3, 6, 12, or 24 h after VZV inoculation. VZV replication at a titer in the range of 0.5 log higher than the inoculum titer was detected when IFN-γ was added at time points up to 12 h and viral titers were measured at 96 h (Fig. 2F). Adding IFN-γ at 24 h had a modest inhibitory effect on VZV replication, with titers being 1 × 103.8 in treated cells and 1 × 104.4 in untreated control cells. These observations indicate that antiviral control depends on the early initiation of type I and or type II IFN signaling and that the ISG-mediated host cell defense against VZV infection induced by IFN-γ exposure was more potent than that induced by IFN-α, as shown by irreversible inhibition, independent of the dose and duration of exposure or the VZV inoculum. The differential effects of IFN-α and IFN-γ on VZV replication were also observed in melanoma (Mel39) cells, which expressed IFNGR1, as shown in Fig. 1B). These data suggest that IFN-γ has similar effects on VZV infection, regardless of cell type, if the target cell expresses the IFN-γ receptor.

FIG 2.

Spatiotemporal effects of IFN-α and IFN-γ on VZV replication and spread. (A) Plaque formation in IFN-pretreated HELFs with or without continued IFN treatment. HELFs were pretreated with either IFN-α or IFN-γ for 2 h or 24 h before inoculation using VZV at a low (400 PFU/ml) or a high (2,000 PFU/ml) inoculum titer. Infection was allowed to proceed for 10 days either in the continued presence of the IFNs or when IFNs were withdrawn after the pretreatment period, just before VZV inoculation. Plaques were visualized by immunohistochemistry staining with anti-VZV antibodies. (B) High-magnification plaque images in IFN-α-pretreated HELFs with or without continued IFN-α treatment. The 2× magnification images of a well at 10 days are shown on the left; the 5× magnification images of four representative plaques at 10 days are shown on the right. (C) High-magnification plaque images after IFN-α or IFN-γ pretreatment for 2 h without continued IFN treatment in monolayers under conditions of a low (400 PFU/ml) or a high (2,000 PFU/ml) inoculum titer. The 2× magnification images of a well at 10 days are shown on the left; the 5× magnification images of four representative plaques are shown on the right. The data shown in panels A to C are representative of those from 12 similar independent experiments. (D) Dose effect of IFN-α and IFN-γ. HELFs were pretreated for 2 h with increasing doses of IFN-α or IFN-γ, as indicated, IFNs were removed, monolayers were inoculated with VZV (400 PFU/ml), and plaque formation was detected by immunohistochemistry at 10 days. (E) Effect of IFN treatment at 48 h after VZV inoculation. HELFs were infected with VZV (WT) and treated with either IFN-α or IFN-γ at 48 h after inoculation, and samples were collected at 72 h and 96 h to measure viral titers by VZV plaque assay, performed in triplicate. The data are representative of those from three similar independent experiments. The error bars show the standard error of the mean. (F) HELFs infected with VZV (WT) were treated with IFN-γ at the indicated times during (0 h) or after (3 to 24 h) virus inoculation. Samples were collected at 96 hpi to measure the viral titers by VZV plaque assay, performed in triplicate. The results are shown as a scatter plot, generated using Prism software. The error bars show the standard error of the mean. The data are representative of those from two similar independent experiments.

Comparative transcriptome analysis of fibroblasts treated with IFN-α and IFN-γ.

To identify differences in the host cell environment induced by type I and type II IFNs that might point to differences in the mechanisms of VZV inhibition, we profiled the RNA transcriptomes in HELFs that were treated with IFN-α or IFN-γ, mock treated for 24 h, or infected with VZV. The Illumina NextSeq platform was used to test three biological replicates for each of the four experimental conditions, yielding paired-end/single-end reads that were aligned to the human hg19 genome in the Illumina BaseSpace platform. Since coverage was low in one IFN-γ-treated sample, the data analysis was done with two IFN-γ replicates.

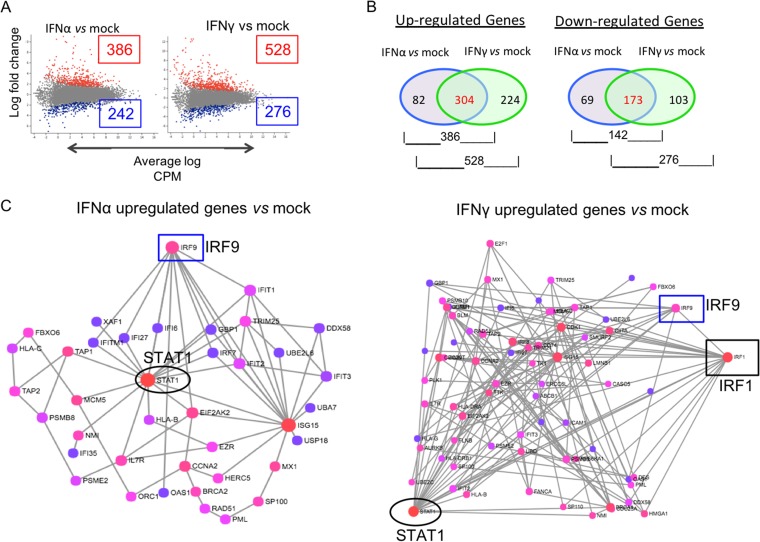

The patterns of differential gene expression between HELFs at 24 h after treatment with IFN-α or IFN-γ and mock-treated HELFs at the same time point are shown in scatter plots of the log fold change (Fig. 3A). IFN-α treatment significantly upregulated 386 genes in HELFs compared to their expression in mock-treated HELFs, whereas 528 genes were upregulated in IFN-γ-treated cells (P ≤ 0.05) (Fig. 3B). Each of the upregulated gene sets was analyzed based on the interaction database of the International Molecular Exchange (IMEx) Consortium using the NetworkAnalyst tool (11). Functional enrichment analyses using the Reactome database identified genes involved in IFN signaling that were detected when HELFs were treated with IFN-α or IFN-γ and compared to mock-treated HELFs, which were then plotted on the network maps shown in Fig. 3C. For example, STAT1 and IRF9 were among the 304 genes that were upregulated in both IFN-α- and IFN-γ-treated cells. Both IFNs also led to the downregulation of 173 genes compared to their expression in untreated HELFs, while 69 and 103 genes were downregulated uniquely in the presence of IFN-α or IFN-γ, respectively (Fig. 3B). Overall, IFN-γ exposure induced or diminished the expression of substantially more cell genes than IFN-α when their basal levels of transcription in HELFs were compared at 24 h posttreatment.

FIG 3.

Comparative transcriptome analysis of IFN-α- and IFN-γ-treated HELFs and uninfected HELFs. (A) Each scatter plot represents a summary of the differential expression of cell gene transcripts, showing genes from the IFN-α- or IFN-γ-treated cells that were upregulated (red dots) or downregulated (blue dots) in reference to their expression in the mock-treated group. The x axis is the average log CPM, with larger values representing higher average expression levels of a gene across all samples. The y axis is the log fold change in expression between the two treatment groups. (B) Venn diagrams showing the numbers of common and exclusive up- and downregulated genes at 24 h after IFN-α and IFN-γ treatment. (C) Gene interaction networks for genes involved in immune regulation that were upregulated in the IFN-α- or IFN-γ-treated cells compared to mock-treated HELFs. The network maps were generated by the NetworkAnalyst tool using the IMEx database for gene interactions. The color of the nodes indicates the gene topology, with red showing maximum interactions and purple indicating minimum interactions. The boxed and circled genes indicate the transcriptional status of the STATs and IRFs, respectively, under each condition.

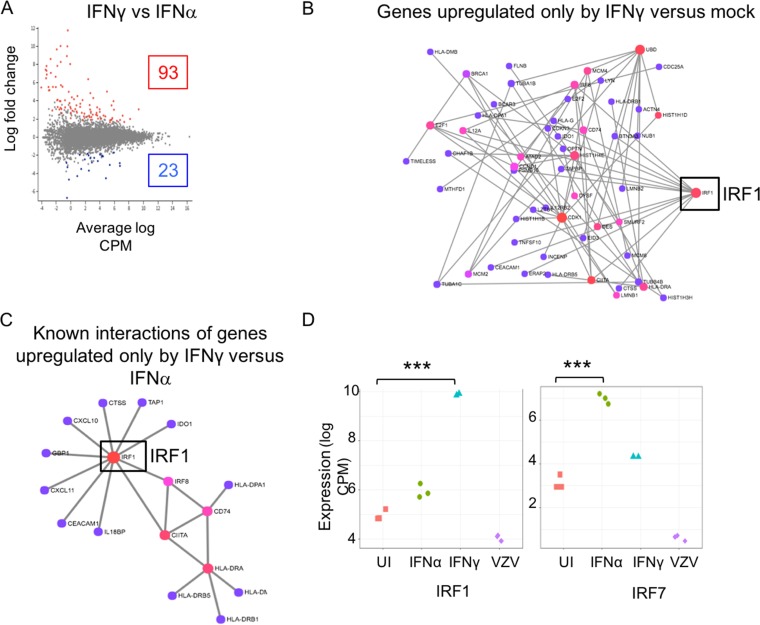

Given the differences between the effects of type I and type II IFNs on VZV infection, we next focused on the cell genes that were differentially regulated by IFN-α and IFN-γ pretreatment for 24 h (Fig. 4A). When we examined the network map generated using the 224 genes that were exclusively upregulated in the IFN-γ-treated cells, we found that among the STAT and IRF family proteins, only IRF1 was differentially expressed (Fig. 4B). Of these, the transcript levels of 23 genes were significantly higher after IFN-α exposure than after IFN-γ exposure, and the transcript levels of 93 were significantly higher after IFN-γ exposure than after IFN-α exposure (P ≤ 0.05). Seventeen of the 93 genes were found to have a direct interaction, based on the network map (Fig. 4C), and IRF1 displayed maximum connectivity in the map, again indicating its central role in the regulation of other genes triggered by IFN-γ. For example, it is well established that IRF1 transcriptionally regulates genes like IDO1 and CD74. The expression levels of the subset of transcripts that were significantly up- or downregulated in IFN-α- versus IFN-γ-treated cells as well as their levels in mock-treated and VZV-infected HELFs are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. Examples are IRF1, which showed significantly a higher level of induction by IFN-γ than by IFN-α (P = 0.000001), and IRF7, which had a higher level of induction after IFN-α treatment than after IFN-γ treatment (P = 0.0003) (Fig. 4D). VZV infection did not affect IRF1 transcripts, but IRF7 transcripts were significantly lower in infected cells than in uninfected HELFs (P < 0.005). Therefore, based on the bioinformatics analyses of the transcriptome sequencing (RNA-seq) data, we hypothesized that IRF1 and its downstream transcriptional programming of the cell are likely a key cellular regulator of VZV replication by IFN-γ signaling.

FIG 4.

Comparative transcriptome analysis of IFN-α- versus IFN-γ-treated HELFs. (A) The scatter plot represents a summary of the differential expression of cell gene transcripts in IFN-α- versus IFN-γ-treated cells. The red dots indicate the genes that were significantly upregulated in the IFN-γ-treated cells, while the blue dots represent those that were upregulated in the IFN-α-treated cells. (B) A gene network map was constructed for genes that were exclusively upregulated in the IFN-γ-treated cells and not by IFN-α treatment compared to their expression in mock-treated HELFs. (C) Network map of the 17 of 93 genes that had significantly higher transcript levels in IFN-γ-treated cells than in IFN-α-treated cells. (D) Mean difference plots using IRF1 and IRF7 as examples of significant differences in expression levels between experimental groups, where the y axis is the log CPM expression level (***, P < 0.0005). UI, uninfected.

IRF1 is critical for the IFN-γ-mediated host cell defense against VZV.

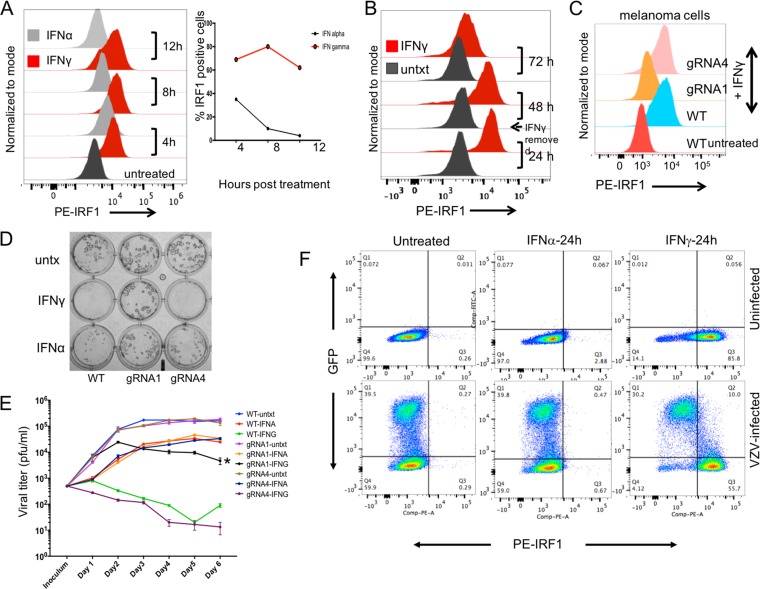

As the first step in assessing the role of IRF1 in the IFN-γ versus the IFN-α response, we used flow cytometry to evaluate IRF1 protein expression in IFN-stimulated cells. Since IRF1 is proteasomally regulated, cells were treated with 50 μM MG132 for 4 to 6 h before analysis. At 4 h after IFN treatment, activated IRF1 was expressed in ∼40% of IFN-α-treated cells, whereas it was expressed in ∼70% of IFN-γ-treated cells. IRF1 protein expression after IFN-α treatment declined to ∼10% of cells by 8 h and <5% by 12 h (Fig. 5A). In contrast, IRF1 expression was sustained in IFN-γ-treated cells throughout the 24-h period, with >80% of the cells expressing IRF1. In addition, >65% of the IFN-γ-treated cells continued to express IRF1 protein 24 h after IFN-γ was removed, declining to ∼10% only at 48 h (Fig. 5B). Thus, the higher IRF1 transcript levels induced by IFN-γ than by IFN-α at 24 h posttreatment resulted in sustained IRF1 protein expression in most IFN-γ-treated cells.

FIG 5.

IRF1 is critical for the IFN-γ-mediated host cell defense against VZV. (A) HELFs were stimulated with either IFN-α or IFN-γ for the indicated times and then analyzed for IRF1 expression compared to that in the untreated HELFs. Data were collected on an LSR II.UV analyzer using a 561-nm green laser for excitation of the phycoerythrin (PE)-IRF1 antibody. Data analysis was done using FlowJo (version 10.0.5) software, and data are represented as a histogram (left) showing IRF1 expression (x axis). The line graph (right) shows the proportion of cells expressing IRF1 at the indicated time points in IFN-α- and IFN-γ-treated cells. (B) HELFs were stimulated with IFN-γ for 24 h, following which cells were grown in the absence of any stimulation and subsequently analyzed for IRF1 expression. Data were collected and analyzed as described above. (C to E) IRF1-knockout (IRF1KO) stable Mel39 cells (gRNA1) were generated using the CRISPR-Cas9 system; gRNA4 Mel39 cells expressing the empty pLentiCRISPRv2 vector were used as a control. (C) The gRNA1, gRNA4, and wild-type (WT) cell lines were treated with IFN-γ for 24 h and evaluated for IRF1 expression knockdown by flow cytometry. (D) The gRNA1, gRNA4, and WT cell lines were inoculated with 50 PFU/ml of VZV after 24 h of IFN-γ pretreatment, and virus detection was done by immunohistochemistry at day 5 postinfection. (E) Growth curve analysis of VZV replication was carried out in the IRF1KO, control, and WT cells treated with either IFN-γ or IFN-α or untreated for 24 h prior to inoculation with VZV (500 PFU/ml). IFNs were withdrawn at the time of inoculation, and cells were harvested from replicate wells for each of the nine test conditions at days 1 to 6; virus titers were assessed using WT Mel39 cells. The data are representative of those from two similar independent experiments. (F) HELFs were infected with VZV-GFP for 48 hpi or mock infected and exposed to IFN-α or IFN-γ for 24 h or left untreated. Prior to fixation, cells were treated with 50 μM MG132 for 6 h. IRF1 expression was evaluated by flow cytometry using the phycoerythrin-IRF1 antibody followed by analysis with FlowJo software. The data are representative of those from five similar independent experiments. untxt and untx, untreated.

Next, we tested the hypothesis that IRF1 is critical for the host cell defense against VZV by using a CRISPR-Cas9 lentivirus system. Stable IRF1 knockout (IRF1-KO) HELFs, melanoma (Mel39) cells, and controls were generated using lentiviruses prepared from the transfection of three guide RNAs (gRNAs; gRNAs 1 to 3) targeting IRF1 or a pLentiCRISPRv2 empty vector (gRNA4) (GenScript). When interference with IRF1 expression was evaluated by flow cytometry, only 10 to 15% of the gRNA1-transfected melanoma cells (gRNA1 melanoma cells) expressed IRF1 at 24 h after IFN-γ treatment in the presence of MG132 (Fig. 5C). IRF1 expression in the control gRNA4-transfected cells was similar to that in wild-type (WT) melanoma cells. Since IRF1 knockdown HELFs were difficult to expand in tissue culture and the two IFNs had similar effects on VZV infection in melanoma cells, IRF1-KO melanoma cells were used to evaluate the effects of inhibiting IFN-stimulated expression of IRF1 on VZV replication.

When gRNA1, gRNA4, and WT melanoma cells were untreated or pretreated with either IFN-γ or IFN-α for 24 h and then inoculated with VZV, infection was detected in untreated gRNA1, gRNA4, and WT cells by 48 h postinfection (hpi) (Fig. 5D). While VZV plaques were not detected in IFN-γ-treated WT melanoma cells, VZV replication was observed in IRF1 knockdown gRNA1 cells pretreated with IFN-γ. These effects on VZV replication were evaluated further in untreated and IFN-treated WT cells, gRNA1 knockdown cells, and control gRNA4 cells in a growth curve analysis (Fig. 5E). Cells were treated with either IFN-α or IFN-γ for 24 h prior to VZV inoculation (500 PFU/ml); IFN stimulation was withdrawn at the time of inoculation. VZV titers were similar in untreated WT, gRNA1, and gRNA4 cells. IFN-α pretreatment led to a marginal decrease in viral titers throughout the 6-day period, and a lack of IRF1 expression did not provide any significant advantage to VZV replication in IFN-α-treated cells. As expected, VZV did not replicate in WT or gRNA4 cells pretreated with IFN-γ. In contrast, VZV replication was detected in IFN-γ-pretreated gRNA1 cells. However, titers were 1.5 logs lower in IFN-γ-pretreated gRNA1 cells than in untreated WT or gRNA4 cells, attributable to the residual expression of IRF1 in 10 to 15% of these cells, allowing a limited IFN-γ effect. This restoration of VZV replication in IRF1KO cells, despite IFN-γ pretreatment, implicated IRF1 as being necessary for mediating the antiviral activity of IFN-γ against VZV.

To complete this analysis of the role of IRF1 in regulating VZV-host cell interactions, we investigated whether VZV interferes with IRF1 protein expression. Consistent with the transcriptional analysis, only a small percentage of uninfected HELFs treated with IFN-α expressed IRF1, while most IFN-γ-treated cells expressed IRF1 at the indicated time point (Fig. 5F). In parallel, HELFs inoculated with VZV-green fluorescent protein (GFP) for 24 h were either untreated or stimulated with IFN-α or IFN-γ for an additional 24 h (Fig. 5F). IRF1 protein expression was evaluated in the uninfected and VZV-infected, untreated cells and IFN-treated cells at 48 h postinfection (hpi) and 24 h posttreatment with either IFN-α or IFN-γ in the presence of MG132. Under all conditions, ∼40% of the cells were infected by VZV. As in the uninfected cells, IFN-α did not induce IRF1 expression after 24 h of treatment in either the bystanders or the VZV-infected cells. Of the ∼40% of cells that were infected in the IFN-γ-treated population, ∼10% had low levels of GFP expression, indicating early VZV infection, and expressed IRF1 protein. IRF1 was not detected in ∼30% of cells with high GFP expression levels, indicating that the more heavily infected cells were refractory to IRF1 induction by IFN-γ. In contrast, IRF1 was induced quite markedly in uninfected bystander cells by IFN-γ, which indicates that reduced IRF1 expression was due to a specific block of its induction in VZV-infected cells. These observations are consistent with the finding that replication can occur if IFN-γ is added following VZV inoculation, since the virus is equipped to block IRF1 induction if it enters the cell prior to IFN-γ exposure (Fig. 2E), and suggest that VZV proteins expressed later in the infectious cycle are likely to mediate IRF1 inhibition.

IRF9 is critical for the IFN-α-mediated host cell defense against VZV.

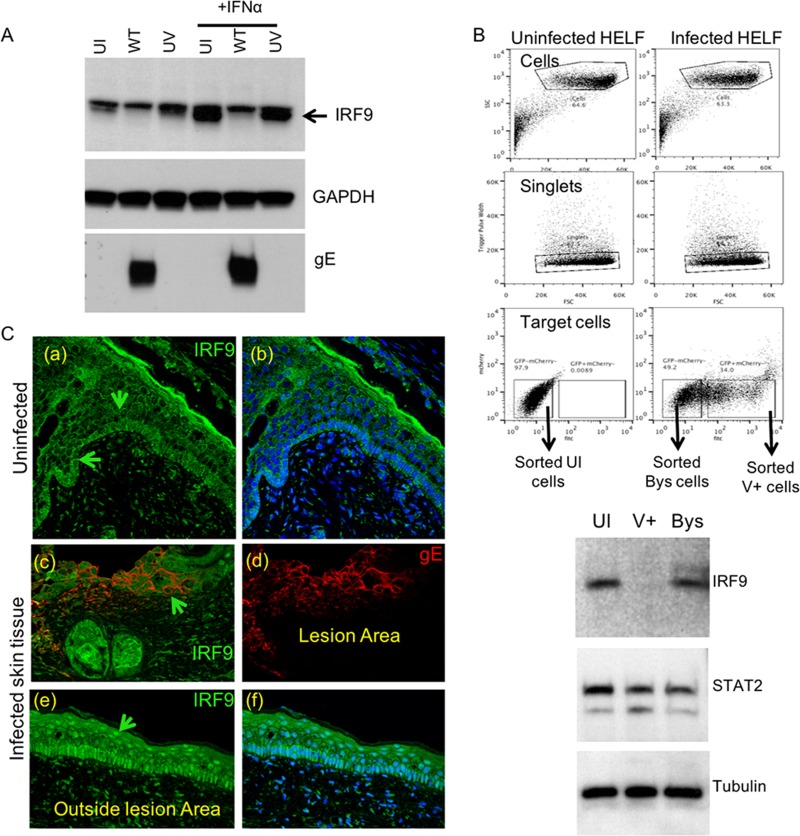

Although the effect of IFN-α was less potent than that of IFN-γ, IFN-α delayed the spread of VZV infection (Fig. 2). However, since both transcriptome and protein analyses showed minimal IRF1 induction by IFN-α at 24 h posttreatment, we sought to define an alternative host defense pathway for the IFN-α-mediated control of VZV. The tripartite ISGF3 complex, consisting of IRF9, pSTAT1, and pSTAT2, is critical for ISG signaling by IFN-α, and the transcription of several ISGs known to depend on this complex was upregulated in IFN-α-treated HELFs (Fig. 3C). Therefore, we examined protein expression and the activation state of the three ISGF3 components in uninfected and VZV-infected HELFs with or without IFN-α treatment. The IRF9 protein was constitutively expressed in uninfected HELFs and was increased by IFN-α stimulation (Fig. 6A). In contrast, basal IRF9 levels were reduced substantially by VZV infection, and the IRF9 response to IFN-α was blocked in VZV-infected cells. The increase in IRF9 expression induced by IFN-α was not inhibited in cells inoculated with nonreplicating, UV-inactivated VZV, and the constitutive expression of IRF9 was not reduced (Fig. 6A), indicating that the inhibition of IFN-α signaling might require the de novo synthesis of VZV proteins in infected cells.

FIG 6.

IRF9 is critical for the IFN-α-mediated host cell defense against VZV. (A) HELFs inoculated with WT or UV-treated virus at an equivalent multiplicity of infection were analyzed for IRF9 expression by Western blotting (top). Western blotting for GAPDH (middle) and gE (bottom) was done to determine protein loading and confirm VZV infection, respectively. IFN-α was added as indicated at 8 hpi, and cells were lysed in RIPA buffer at 24 hpi. The data are representative of those from five similar independent experiments. (B) For fluorescence-activated cell sorting, the inoculum cells were stained using the CellTracker red CMTPX, which allowed sorting of newly infected cells. The dot plots show the sorting scheme that was used to isolate uninfected, bystander, and infected cells. Equal numbers of cells from each of the three populations were then used for Western blotting using the indicated antibodies. The data are representative of those from two similar cell sorting experiments. SSC, side scatter; FSC, forward scatter; fitc, fluorescein isothiocyanate; Bys, bystander cells; V+, VSV-infected cells. (C) Immunofluorescence detection of IRF9 (indicated by the green arrows) in uninfected (a to b) and VZV-infected (c to f) skin xenografts. Sections were stained for gE (Alexa Fluor 594; red) and IRF9 (Alexa Fluor 488; green) expression. The data are representative of those from three similar independent experiments.

In order to determine if the VZV regulation of IRF9 was specific for infected as opposed to bystander cells, HELFs were inoculated with recombinant VZV expressing GFP for 48 h. IRF9 levels were assessed in the viable infected and uninfected cells sorted by GFP expression and in an uninfected HELF control. The IRF9 protein was reduced only in infected cells, indicating that inhibition of the IFN-α signaling pathway was not secondary to secreted factors made in response to VZV infection (Fig. 6B).

Since the type I IFN response is necessary to restrict VZV lesion formation, we investigated the potential relevance of IRF9 for IFN-α-mediated control using the SCID mouse model of VZV skin pathogenesis. Human skin xenografts were recovered 14 days after mock inoculation or VZV infection and stained for IRF9 and VZV glycoprotein E (Fig. 5C). In mock-infected skin, IRF9 was detected in the cytoplasm of most cells within the basal epithelium and cells lining the hair follicles; nuclear IRF9 was detected in a few cells within the granule and prickle cell layers of the epidermis (Fig. 6C, panels a and b). In contrast, IRF9 expression was increased dramatically in the nuclei of uninfected cells adjacent to VZV lesions in infected xenografts. Nuclear IRF9 expression was prominent both in the basal epithelium and in the hair follicles of these bystander cells, whereas IRF9 was not detected in VZV lesions (Fig. 6C, panels c to f). The pattern of IRF9 nuclear localization in bystander cells was consistent with the activation of IFN-α signaling in VZV-infected skin tissue (2), and the findings show that viral interference with IRF9 expression within infected skin cells occurs during VZV lesion formation in vivo.

STAT1 and STAT2 phosphorylation, nuclear localization, and heterodimerization are not inhibited during VZV infection.

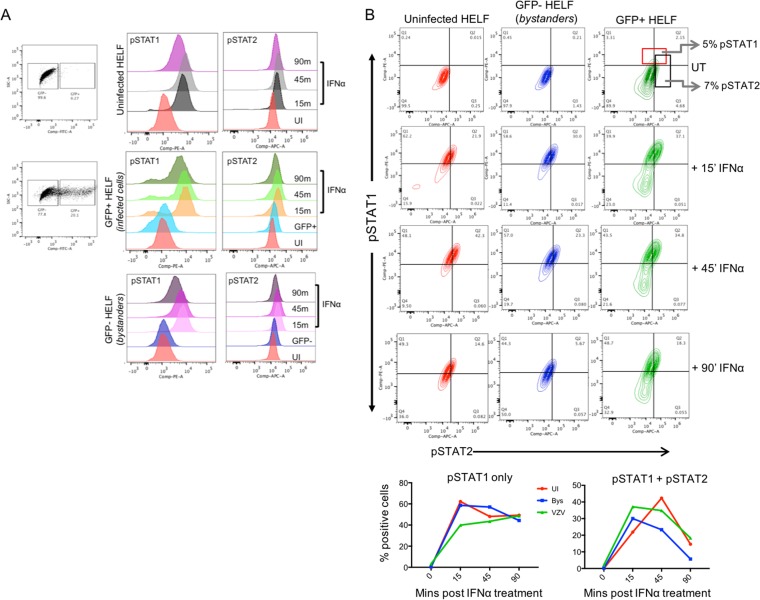

To further document the critical role of IRF9 in the IFN-α-mediated host cell defense, we next investigated VZV effects on the STAT1 and STAT2 components of the ISGF3 complex. Since both STATs are expressed constitutively in most cells and both must be phosphorylated for functional activation during IFN stimulation, we evaluated the phosphorylation status of the two proteins in the presence of VZV infection. As expected, IFN-α induced the phosphorylation of STAT1 and STAT2 in uninfected HELFs, as shown using flow cytometry to detect pSTAT1-Y701 and pSTAT2-Y689 (Fig. 7A). The kinetics of STAT1 and STAT2 phosphorylation in response to IFN-α in VZV-infected cells did not differ from that in uninfected bystander cells or the uninfected HELF control, showing that VZV did not interfere with STAT1 or STAT2 activation (Fig. 7B). In fact, ∼5% of VZV-infected cells expressed pSTAT1 or pSTAT1/2 without IFN-α stimulation.

FIG 7.

STAT1 and STAT2 phosphorylation is not inhibited during VZV infection. (A) HELFs were mock or VZV infected for 24 h, followed by stimulation with 104 U of IFN-α or no treatment for the indicated times. Cells were fixed, permeabilized, and stained for pSTAT1-Y701-phycoerythrin and pSTAT2-Y689, detected by the Alexa Fluor 647-rabbit IgG secondary antibody, and analyzed by flow cytometry. The histograms show pSTAT1 (left) and pSTAT2 (right) expression in uninfected, bystander, and GFP-positive populations. (B) The contour plots show the frequency of cells in uninfected, bystander, and infected cell groups that were pSTAT1, pSTAT2, and pSTAT1 plus pSTAT2 positive following IFN-α stimulation. The line graphs show STAT1 and STAT1 plus STAT2 phosphorylation kinetics for each of the three sorted groups of cells. The data are representative of those from two similar independent experiments. SSC-A, side scatter area; FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate; PE, phycoerythrin; APC, allophycocyanin; Comp, compensated; Q1 to Q4, quadrants 1 to 4, respectively.

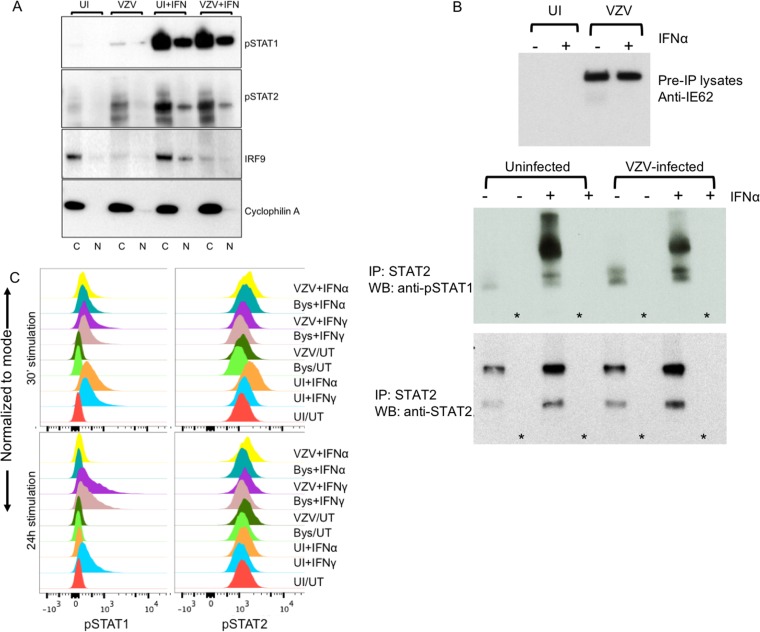

To determine whether VZV infection interfered with the nuclear transport of pSTAT1-Y701 and pSTAT2-Y689, cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions were prepared from HELFs that were untreated or treated with IFN-α and mock infected or infected with VZV. As shown in Fig. 8A, IFN-α-treated HELFs showed increased levels of pSTAT1 and pSTAT2 both in the cytoplasm and in the nucleus. The levels of nuclear pSTAT1 and pSTAT2 in VZV-infected cells treated with IFN-α did not differ from those in the controls, indicating that VZV did not block the nuclear translocation of phosphorylated STAT proteins. Low levels of pSTAT1 were also detected in the cytoplasm of infected cells in the absence of IFN-α, confirming the flow cytometry data (Fig. 7B). Finally, pSTAT1-pSTAT2 heterodimers were formed in VZV-infected cells as well as in uninfected cells in response to IFN-α, shown using antibody to total STAT2 for immunoprecipitation and probing for pSTAT1 (Fig. 8B); further analysis by mass spectrometry confirmed the presence of STAT1 in the STAT2 complex in both uninfected and VZV-infected cells treated with IFN-α.

FIG 8.

STAT1 and STAT2 nuclear localization and heterodimerization are not inhibited during VZV infection. (A) Western blot analysis of IRF9, pSTAT1, and pSTAT2 expression in the cytoplasmic fractions (lanes C) and nuclear fractions (lanes N) purified from VZV-infected and uninfected HELFs that were treated with 104 U of IFN-α or mock treated. Cyclophilin was used as a loading control and for determination of the fractionation purity. The data are representative of those from two similar independent experiments. (B) Immunoblot analysis of mock- and VZV-infected HELF lysates that were treated with IFN-α (lanes +) or mock treated (lanes −) before (top panel) and after (middle and bottom panels) coimmunoprecipitation. The lysates were immunoprecipitated with STAT2 antibody and probed with antibodies to pSTAT1 and pSTAT2. The lanes marked with an asterisk indicate the bead-only (no-antibody) control lanes. The data are representative of those from two similar independent experiments. IP, immunoprecipitation; WB, Western blotting. (C) Flow cytometry analysis of pSTAT1 (phycoerythrin) and pSTAT2 (allophycocyanin) expression in mock- or VZV-infected HELFs treated with IFN-α or IFN-γ for 30 min or 24 h. Cells were analyzed at 48 hpi. The infected and the bystander populations from the VZV-infected samples were distinguished (gated) based on GFP expression during analysis with FlowJo software. The histograms represent the expression of pSTAT1 and pSTAT2 detected in uninfected, bystander (GFP-negative), and infected (GFP-positive) cells treated with either IFN-α or IFN-γ for 30 min or 24 h or left untreated. The data are representative of those from two similar independent experiments.

Since pSTAT1 homodimers act as transcriptional units to initiate the primary ISG response to IFN-γ signaling, which includes IRF1 upregulation, and IRF1 is part of the secondary response that triggers the upregulation of IRF1-dependent transcripts in response to IFN-γ, we evaluated the phosphorylation state of STAT1 and STAT2 at early (30 min) and late (24 h) time points after IFN-α and IFN-γ exposure. The effect of VZV infection on their activation state was also evaluated (Fig. 8C). As expected, STAT2 was not activated by IFN-γ at the early or late time points, while pSTAT1 was upregulated by both IFNs at 30 min but only by IFN-γ at 24 h. As was observed with IFN-α, VZV did not interfere with STAT1 phosphorylation in the presence of IFN-γ at the early or late time point.

IRF9 is transcriptionally regulated by the VZV IE62 protein.

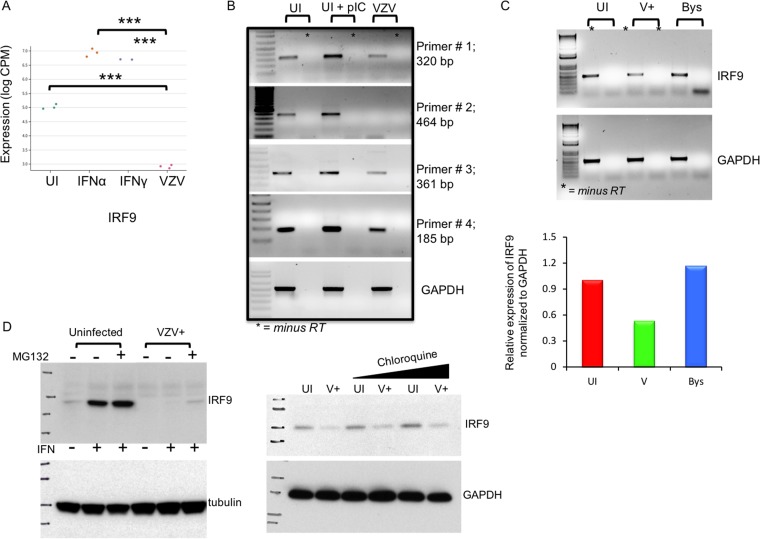

IRF9 transcripts were reduced significantly in VZV-infected cells compared to uninfected cells, as determined by RNA-seq (P < 0.001) (Fig. 9A). When measured by reverse transcription (RT)-PCR using four primer pairs spanning different regions of the 1,182-bp IRF9 transcript, low basal levels of IRF9 transcripts were detected in uninfected HELFs, as expected, since the IRF9 protein was constitutively expressed in the cytoplasm (Fig. 6A). While IRF9 transcripts were increased in HELFs treated with poly(I·C) as a positive control, IRF9 transcript levels were reduced in VZV-infected cells (Fig. 9B). When the levels of IRF9 transcripts were evaluated in sorted cell populations, IRF9 transcripts were present at levels 50% lower in VZV-infected cells than in bystander or uninfected cells (Fig. 9C). IRF9 expression did not differ in uninfected and VZV-infected cells, when the proteasomal and lysosomal inhibitors MG132 and chloroquine, respectively, were used to interfere with protein degradation, indicating that IRF9 expression was not regulated by accelerated protein turnover in infected cells (Fig. 9D). These results indicate that the impaired IRF9 protein expression in VZV-infected cells was due to reduced IRF9 gene transcription.

FIG 9.

IRF9 is transcriptionally downregulated by VZV during infection. (A) Mean difference plot illustrating significant differences in the expression level of IRF9 (***, P < 0.0001) between experimental groups, where the y axis is the log CPM expression level. (B) Semiquantitative RT-PCR analysis of IRF9 transcripts, amplified from different regions of the 1,182-bp-long full-length RNA, in uninfected and VZV-infected HELFs. Poly(I·C) was used as a positive control for IRF9 induction in HELFs; GAPDH was the housekeeping gene control. The data are representative of those from two similar independent experiments. (C) Semiquantitative RT-PCR analysis of IRF9 transcripts in flow cytometry-sorted uninfected, bystander, and VZV-infected (V or V+) HELFs. The PCR products were run on a 1% agarose gel and imaged using a GelDoc system. The image was analyzed by ImageJ software to quantify the relative expression of IRF9 under each condition, as shown in the bar graph. The data are representative of those from two similar independent experiments. (D) Western blot analysis of IRF9 expression in unfractionated mock- and VZV-infected HELF lysates that were treated with proteasome (MG132) and lysosome (chloroquine) inhibitors or mock treated, as indicated. The data are representative of those from two similar independent experiments.

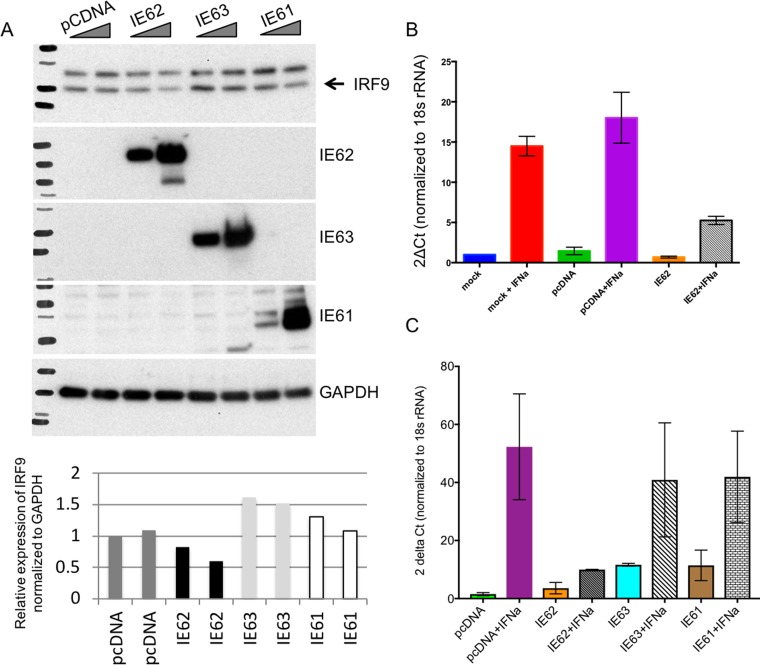

Since countering IFN-α signaling is likely to be important at the initial phase of infection, VZV proteins with transactivating functions that are expressed very early in infected cells were evaluated as candidates for IRF9 regulation. These included IE62, the major VZV-transactivating factor; the ORF61 protein; and IE63, which has been proposed to control IRF9 expression in VZV-infected cells (12). IRF9 protein expression was determined after IFN-α treatment of HEK293 cells transfected with plasmids expressing IE62, the IE61 (ORF61) protein, or IE63 and the controls. IE62-transfected cells showed a >60% reduction in the levels of the IRF9 protein compared to cells transfected with IEF61, IE63, and the cDNA control (Fig. 10A). Further, IE62 inhibited the IFN-α-mediated upregulation of IRF9 transcripts in HEK293 cells (Fig. 10B), supporting its contribution to blocking IRF9 expression. When the effects of each of the three immediate early proteins on IRF9 transcription were assessed, only IE62 reduced IRF9 transcription in response to IFN-α (Fig. 10C). Nevertheless, comparing these effects with changes in IRF9 expression in VZV-infected cells indicates that other viral or host factors also contribute to interference with IRF9.

FIG 10.

IRF9 is transcriptionally downregulated by the VZV-encoded IE62 protein. (A) Western blot analysis of IRF9 expression in HEK293 cells treated with IFN-α and transfected with control and IE62-, IE61-, and IE63-expressing plasmids. The relative expression of IRF9 in the presence of IFN-α and each of the three immediate early proteins was quantified using ImageJ software. IRF9 expression was normalized to GAPDH expression. (B) Quantitative PCR analysis of IRF9 transcript levels in HEK293 cells transfected with control and IE62-expressing plasmids. (C) Quantitative PCR analysis of IRF9 transcript levels in HEK293 cells transfected with control and IE62-, IE61-, and IE63-expressing plasmids. The quantitative PCR data analyses whose results are shown in panels B and C were done in Prism software. Each experiment was done in triplicate, and the error bars denote the standard error of the mean. The data shown are representative of those from three independent experiments. Ct, threshold cycle.

Taken together, these experiments show that the IRF9 component of the ISGF3 complex is critical for the IFN-α-mediated host cell response to VZV, which is further supported by the finding that VZV targets IRF9 protein expression for inhibition by IE62.

DISCUSSION

While the clinical patterns of primary and recurrent VZV infections are well-known, the molecular mechanisms that achieve the usual control of these infections in the human host are not yet well-defined. Here, we show that IFN-α has a limited and reversible effect on VZV replication and cell-cell spread in human fibroblasts and melanoma cells, whereas IFN-γ inhibition is irreversible. At the molecular level, these differential effects reflect signaling through alternative host cell IRF-modulated pathways, mediated by IRF9 for IFN-α and IRF1 for IFN-γ responses. Conversely, if infection is initiated before the IFN-α- or IFN-γ-induced antiviral state is established, VZV is armed with mechanisms that efficiently inhibit IRF9 and IRF1 expression, further underscoring their importance for VZV control.

These findings support a critical role for cellular IRFs in the innate IFN-α response as the first line of defense when VZV is delivered to skin by infected T cells during varicella or by retrograde axonal transport from neurons during reactivation and in the resolution of these infections by adaptive IFN-γ-producing VZV-specific T cells. The importance of these first- and second-line IRF-dependent defenses for regulating VZV pathogenesis is evident in immunocompromised children, who have typical varicella skin lesions for the first few days after onset but who develop progressive varicella associated with a failure to develop IFN-γ-producing VZV-specific CD4 T cells (3). Administering IFN-α has only a modest effect on the duration of new lesion formation, consistent with a requirement for IFN-γ control mediated through IRF1 (13). Similarly, zoster is significantly more common when VZV-specific T cells that produce IFN-γ are diminished and the formation of skin lesions within the affected dermatome is more extensive, even though local immune responses are intact (14). T cells are also prominent within the affected ganglia during and after zoster (15). It is possible that resident T cells in ganglia play a role in controlling VZV reactivation from latency through their capacity to produce IFN-γ.

IRF1 is one of the nine members of the IRF protein family with a common N-terminal helix-turn-helix motif that facilitates DNA binding, thereby allowing transcriptional activation of several hundred downstream genes (16), as illustrated by our network map. IRF1 is an ISG which is upregulated severalfold either by the ISGF3 complex formed during IFN-α receptor stimulation or by the pSTAT1 homodimeric complex made as a result of IFN-γ receptor (IFNGR) stimulation. In seeking a molecular basis for the differential effects of type I and type II IFNs on VZV replication, we demonstrated that the robust induction of IRF1 by IFN-γ produces a highly potent antiviral effect not achieved by IFN-α signaling. The central role of IRF1 in the IFN-γ response against VZV was shown at the level of gene transcription and protein expression and by IRF1 gene knockout experiments. Although both IFN-α and IFN-γ triggered IRF1 protein synthesis, the kinetics of IRF1 expression differed markedly. Whereas the IRF1 protein was detected transiently after IFN-α exposure, with its level peaking at 4 h and then declining, IRF1 expression was sustained in IFN-γ-treated cells for >24 h after treatment was withdrawn. This differential effect was also evident from the distinct mRNA transcriptomes detected in cells treated with IFN-α and those treated with IFN-γ. At 24 h, IRF1 and many downstream IRF1-dependent genes were transcriptionally upregulated in IFN-γ-treated cells. Conversely, CRISPR knockdown of IRF1 led to robust VZV replication, despite prior exposure of the cells to IFN-γ. While the transient induction of IRF1 by IFN-α might contribute to the limited control of VZV observed in IFN-α-treated cells, the role is minor since VZV replication did not differ between WT and IRF1KO cells exposed to IFN-α. IRF1 was not induced by IFN-γ in cells infected with VZV prior to treatment, indicating that VZV has the capacity to block synthesis or rapidly degrade the IRF1 protein.

IRF9, which was central to the host cell defense against VZV triggered by IFN-α signaling, confers a DNA binding capacity to several multimeric transcriptional complexes and thus plays a pivotal role in the signal transduction of multiple cytokine-triggered pathways, including the type I IFN pathway (17, 18). The significance of IRF9 for IFN-α-dependent protection was demonstrated by the finding that VZV inhibited the expression of IRF9 but not that of pSTAT1 or pSTAT2, the other two components of the ISGF3 complex. Targeting a critical junctional molecule like IRF9 has predicted modulatory effects on multiple signaling pathways in VZV-infected cells, as indicated by our network analysis. The presence of pSTAT1 and pSTAT2 in the nucleus of VZV-infected cells despite the absence of IRF9 was unexpected, based on the canonical requirement for all three proteins for nuclear translocation. However, our data provide experimental support for the bipartite complex theory which proposes that the pSTAT1-pSTAT2 complex can be transported to the nucleus independently of IRF9 (19). We note that the detection of nuclear pSTAT in VZV-infected cells differs from our early report on STAT1 expression in VZV-infected skin xenografts (2). These skin sections were stained with an anti-STAT1 antibody, and nuclear translocation was used as a marker of STAT1 phosphorylation in the absence of a pSTAT1 antibody. We did not detect nuclear STAT1 within infected skin cells, but this was a relatively insensitive method, given the cytopathic effects of VZV, and further study with improved reagents and methods is warranted.

Importantly, although both the IFN-α and IFN-γ signaling pathways depend on the activation of STAT1 by phosphorylation to initiate signal transduction and the upregulation of IRFs, VZV did not block STAT1 activation in response to either type I or type II IFNs. Blocking pSTAT1 is an effective strategy to evade IFN-dependent cellular defenses, as shown by HSV-1 ICP27 interference with STAT1 phosphorylation and the inhibition of IFN-γ-mediated STAT1 activation by Kaposi's sarcoma herpesvirus (KSHV) (20, 21). Instead, VZV relies on inhibition of IRF1 and IRF9 in fibroblasts, which are otherwise the critical barrier to replication. Of interest, the target cell type may influence this process since VZV reduced IFN-γ-mediated STAT1 phosphorylation in infected T cells (22). It may be important for VZV to avoid inhibiting phosphorylation of the STAT family proteins in cells other than T cells where cell-cell spread does not occur, since we found that STAT3 activation was necessary for VZV lesion formation and replication in skin xenografts (23).

More generally, while IRF1 has been shown to play a role in other virus infections, including vesicular stomatitis virus, hepatitis C virus, HSV-1, and murine herpesvirus 68 infections (24–27), IRF9 has not been well studied. Our observations suggest that IRF9 has essential functions that can be targeted by viruses that do not disrupt ISG3 formation via interference with the pSTAT1 and pSTAT2 components. Notably, since the ISGF3 complex is also necessary for type III IFNs, IRF9 could be important in this antiviral host defense mechanism and may be disrupted by viruses that must evade type III IFN signaling.

These observations about the roles of IRF1 and IRF9 in the intrinsic host cell defense and the effects of VZV on their expression extend our previous finding that VZV blocks IRF3. While IRF3 is critical for initiating type I IFN signaling by binding the IFN-αβ receptor, IRF9 amplifies the expression of genes triggered via the IFN-αβ pathway. Of interest, both IRF3 and IRF9 are regulated by IE62, which is a promiscuous VZV regulatory protein that enters the cell as a component of the virion tegument and is produced in infected cells at the immediate early time point (28) Although IE63 has been suggested to degrade IRF9 in infected cells, IRF9 degradation was not observed and IE63 alone did not affect IRF9 protein levels when its expression was upregulated by IFN-α signaling. While IRF3 was inhibited by replication-deficient VZV, blocking IRF9 expression required virus replication, indicating that other viral and/or cellular cofactors are necessary for IRF9 inhibition.

Placing these findings in the context of the pathogenesis of VZV infection of skin during primary or recurrent infection, we propose a hierarchy of interactions between the virus and IRF-mediated host defenses. First, infection of a few cells must be established by blocking IRF3 activation to disarm the autocrine IFN-β receptor-dependent induction of IFN-α responses, which occurs when virion entry delivers IE62 into a resting cell. When replication is initiated, amplification of the IFN-α response is impaired by blocking IRF9 expression, allowing some cell-cell spread, despite local IFN-α upregulation. Our studies of lesion formation in skin xenografts show that this is a slow process, requiring at least 7 days after infection. VZV interference with IRF1 expression makes actively infected cells refractory to the IFN-γ secreted by natural killer cells first and then by VZV-specific T cells in the immunocompetent host. This remodeling of cytokine pathways achieved by inhibiting the production of IRF9- and IRF1-dependent ISGs gives the advantage to the virus for a period of time sufficient to create virus-filled lesions at skin surfaces, necessary for VZV transmission to susceptible hosts. However, because of the potency of the IRF1-mediated response, uninfected skin cells are highly resistant to VZV infection, and new lesion formation is halted when IFN-γ is delivered to lesion sites by VZV-specific T cells. As a consequence of this hierarchy of virus-host interactions, severe complications of infection are rare, transmission to other susceptible individuals occurs, and VZV persists in the population.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture.

Human embryonic lung fibroblasts (HELFs) were maintained in Eagle's minimum essential medium (Corning, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) and an antibiotic cocktail of penicillin G and streptomycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) and amphotericin (Corning, USA). Melanoma (Mel39) cells were propagated in the above-described medium supplemented with nonessential amino acids (Corning, USA). Human embryonic kidney (HEK293) cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Corning, USA) supplemented with 10% FCS and 100 U/ml each of penicillin G and streptomycin. All cells were maintained and grown at 37°C with a 5% CO2 concentration.

Virus infection and UV inactivation.

The wild-type pOka strain of VZV (28) and the GFP recombinant VZV (GFP-ORF10) (23) were used in the study. For UV inactivation, VZV-infected HELFs were UV irradiated for 25 min under sterile conditions. Virus inactivation was confirmed by virus titration. A duplicate infected plate prepared in parallel was left untreated and used as a control.

VZV plaque assay.

VZV titers were determined by counting the plaques formed in Mel39 cell monolayers. Infected cells were harvested and resuspended in 1 ml of medium. Tenfold serial dilutions of the infected cells were prepared; subsequently, each serial dilution was added to triplicate wells of a 24-well plate and VZV infection was allowed to proceed for 4 days. On day 4, the cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA), followed by immunohistochemical detection of VZV proteins using an antibody cocktail (Table 1). Plaques from triplicate wells were counted to determine the VZV titer.

TABLE 1.

Antibodies used in the study

| Antibodya | Source | Application |

|---|---|---|

| Rabbit anti-IFNGR1 (EPR7866) | Abcam | Western blotting |

| Mouse anti-ISGF-3γ p48 (H-10) (IRF9) | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Western blotting |

| Rabbit anti-IRF1 (C-20) | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Western blotting |

| Mouse anti-GAPDH (G-9) | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Western blotting |

| Rabbit anti-STAT1 (42H3) | Cell Signaling Technology | Western blotting |

| Rabbit anti-STAT2 | Cell Signaling Technology | Western blotting |

| Rabbit anti-phospho-STAT1 (Tyr701)(D4A7) | Cell Signaling Technology | Western blotting |

| Rabbit anti-cyclophilin A | Cell Signaling Technology | Western blotting |

| Mouse anti-VZV glycoprotein I | Millipore Sigma | Immunofluorescence |

| Rabbit anti-phospho-STAT2 (Tyr689) | Millipore Sigma | Western blotting |

| Flag-M2 | Agilent | Western blotting |

| IE62 | See reference 37 | Western blotting |

| IE63 | See reference 38 | Western blotting |

| Amersham ECL rabbit IgG, HRP-linked whole antibody (from donkey) | GE Healthcare Life Sciences | Western blotting |

| Amersham ECL mouse IgG, HRP-linked whole antibody (from sheep) | GE Healthcare Life Sciences | Western blotting |

| Phospho-STAT1 (Tyr701), PE | eBioscience | Flow cytometry |

| Human phospho-STAT2 (Y689) | R&D Systems | Flow cytometry |

| Donkey anti-rabbit IgG (H+L), Alexa Fluor 647 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Flow cytometry |

| PE mouse anti-human IRF1 | BD Biosciences | Flow cytometry |

| PE mouse anti-human IFNGR1 | BD Biosciences | Flow cytometry |

| ISGF-3γ p48 (H143) (IRF9) | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | |

| Donkey anti-rabbit IgG (H+L), Alexa Fluor 488 | Invitrogen | Immunofluorescence |

| Goat anti-mouse IgG (H+L), Alexa Fluor 594 | Invitrogen | Immunofluorescence |

| Anti-VZV polyclonal serum | Meridian Life Science | Immunohistochemistry-plaque assay |

HRP, horseradish peroxidase; PE, phycoerythrin.

Antibodies and reagents.

The antibodies for immunohistochemistry, Western blotting, and flow cytometry analysis used in the study are listed in Table 1. For cell stimulation using purified recombinant interferons, IFN-α and IFN-γ were purchased from PBL Assay Science and used at the concentrations indicated above. MG132 and chloroquine were purchased from Calbiochem.

Transfection, Western blotting, and coimmunoprecipitation.

For transient-transfection experiments, HEK293 cells were plated 24 h prior to transfection. Two micrograms of each of the plasmids expressing VZV proteins IE62, IE63, and ORF61 was transfected using the Fugene6 reagent (Promega, USA). Whole-cell lysates from transfected cells were prepared by lysing cells in radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer supplemented with a protease inhibitor (Millipore Sigma, USA). The protein lysates were separated on a 4 to 20% SDS-PAGE gel (Bio-Rad, USA), followed by immunoblotting using the antibodies (Table 1) indicated in the figures. For coimmunoprecipitation, cells were lysed from 10-cm culture dishes at 48 h posttransfection and assayed using a Pierce coimmunoprecipitation kit following the manufacturer's instructions (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA).

Immunofluorescence (IF).

Uninfected and VZV-infected skin sections were prepared from skin xenografts engrafted in SCID mice as described previously (23). Animal use was approved by the Stanford University Administrative Panel on Laboratory Animal Care. Paraffin-embedded skin sections were deparaffinized and rehydrated, followed by antigen retrieval using the citrate method. The sections were probed for VZV infection using anti-gE antibody (Millipore Sigma, USA) and IRF9-H143 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, USA). The primary antibodies were detected using donkey anti-rabbit immunoglobulin-Alexa Fluor 488 and goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin-Alexa Fluor 594 (Invitrogen, USA). Images were captured using a Leica SP2 confocal microscope at the Stanford Cell Sciences Imaging Facility, Stanford University.

Flow cytometry and cell sorting.

For flow cytometry analysis of uninfected and VZV-infected HELFs, the cells were trypsinized, washed, and resuspended in fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) buffer (0.5% bovine serum albumin plus 0.02% sodium azide in phosphate-buffered saline). The cells were fixed in 1.6% PFA (Electron Microscopy Sciences, USA) for 10 min, washed, and permeabilized for assaying intracellular proteins by incubation in cold methanol on ice for 30 min. Relevant fluorophore-tagged antibodies (Table 1) were added to a final volume of 100 μl, and the cells were stained for 30 min on ice. The cells were then washed in ice-cold FACS buffer and resuspended in 200 μl of 1:5,000 DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) diluted in FACS buffer for viability staining. Data acquisition was done on a BD LSR II.UV instrument (BD Biosciences, USA) at the Stanford Shared FACS Facility, Stanford University. BD CompBeads were used to normalize spectral overlap (BD Biosciences, USA). Data analysis was done using FlowJo software (version 10.0.5).

For sorting, uninfected and GFP-expressing VZV-infected cells were trypsinized, washed, and resuspended in FACS buffer containing DAPI to sort viable infected cells. Cells were sorted on the Carmen apparatus at the Stanford Shared FACS Facility, Stanford University. Equal numbers of cells from uninfected, bystander (GFP-negative), and infected (GFP-positive) populations were used for RNA and protein analysis.

RNA isolation and RT-PCR assay.

RNA was isolated from infected and uninfected HELFs using the TRIzol reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) per the manufacturer's instructions. Total RNA (1 μg) was used for DNase I (Invitrogen, USA) digestion, and reverse transcription was done using a first-strand cDNA synthesis kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Five percent of the first-strand reaction mixture was used for PCR analysis to detect IRF9 and GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) transcripts. The sequences for the IRF9 primers (ELIM Biopharm, USA) used were as follows: for primer pair 1, forward primer TGA GAG GGG CAT CCT AGT GG and reverse primer TCT GCT CCA GCA AGT ATC GG; for primer pair 2, forward primer TAC AGA CAC AAC TGA GGC CC and reverse primer TTA CCT GGA ACT TCG GTG GG; for primer pair 3, forward primer GCT GAG CCC TAC AAG GTG TAT and reverse primer AGA TGA AGG TGA GCA GCA GTG; and for primer pair 4, forward primer GAG CTC TTC AGA ACC GCC T and reverse primer GTC TGC TCC AGC AAG TAT CGG. The GAPDH primers have been described previously (28).

CRISPR-Cas9 IRF1KO using lentivirus.

The IRF1 knockout and control cell lines were generated by transfecting IRF1 CRISPR guide RNA (Table 2) cloned in the pLentiCRISPR vector (GenScript, USA) into HEK293 cells using the Lipofectamine 3000 reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Transfected cells were incubated for 48 h at 37°C in 5% CO2, following which the supernatant containing lentivirus particles was harvested. Target cells (HELFs or Mel39 cells) were transduced in the presence of 4 μg Polybrene (Millipore Sigma, USA) by spinoculation at 1,800 rpm for 45 min at room temperature. The transduced cells were selected by puromycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) at 10 μg/well of a 6-well plate, and gene knockout was confirmed by FACS analysis for IRF1 expression.

TABLE 2.

IRF1 guide RNA sequences

| Guide RNA | Sequence |

|---|---|

| gRNA1 | TCTTTCACCTCCTCGATATC |

| gRNA2 | CCTCTAGGCCGATACAAAGC |

| gRNA3 | GTGTAGCTGCTGTGGTCATC |

RNA-seq analysis.

Three biological replicates of four conditions including uninfected and untreated HELFs (control), IFN-α- and IFN-γ-treated HELFs, and VZV-infected HELFs were prepared for RNA sequencing. RNA was purified using the TRIzol reagent per the manufacturer's instructions (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). RNA library preparation and sequencing on the Illumina NextSeq (Illumina, USA) platform were performed at the Stanford Functional Genomics Facility at Stanford University. The resulting RNA-seq counts per gene were analyzed by closely following the RNAseq123 work flow (29), using tools from the Bioconductor project (30). Filtering, normalization, and modeling were done using methods from edgeR (31) and limma (32). Filtering was performed on log count per million (log CPM)-transformed data to remove low-expression genes across samples. Subsequently, the samples were trimmed mean of M values (TMM) normalized to account for batch effects and the different RNA compositions between the samples (33). The mean variance independence condition for linear modeling was achieved using precision weights, calculated by the voom method (34). Finally, empirical Bayes moderation was used to calculate gene-wise variance estimates by borrowing information from across all genes, yielding the moderated t test statistics used to determine differential expression (35). In addition to meeting the Benjamini-Hochberg-adjusted P value threshold of 0.05, differentially expressed genes from the linear model were considered significant under conservative conditions of a minimum of a 2-fold change in expression between two experimental conditions (36).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Bianca Gomez for her technical assistance in FACS analysis and sorting at the Stanford Shared FACS Facility, Stanford University, and John Coller and Vida Shokohi for their technical assistance in carrying out RNA sequencing at the Stanford Functional Genomics Facility, Stanford University. We thank Adrish Sen and Gourab Mukherjee for their advice about conceptualization of the project and data analysis and Mohamed Khalil for providing the VZV IE62-expressing plasmids.

This work was supported by NIH grant AI20459.

We declare no competing interest.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.01151-18.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zerboni L, Sen N, Oliver SL, Arvin AM. 2014. Molecular mechanisms of varicella zoster virus pathogenesis. Nat Rev Microbiol 12:197–210. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ku CC, Zerboni L, Ito H, Graham BS, Wallace M, Arvin AM. 2004. Varicella-zoster virus transfer to skin by T cells and modulation of viral replication by epidermal cell interferon-alpha. J Exp Med 200:917–925. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arvin AM, Koropchak CM, Williams BR, Grumet FC, Foung SK. 1986. Early immune response in healthy and immunocompromised subjects with primary varicella-zoster virus infection. J Infect Dis 154:422–429. doi: 10.1093/infdis/154.3.422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weinberg A, Levin MJ. 2010. VZV T cell-mediated immunity. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 342:341–357. doi: 10.1007/82_2010_31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Samuel CE. 2001. Antiviral actions of interferons. Clin Microbiol Rev 14:778–809. doi: 10.1128/CMR.14.4.778-809.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schindler C, Levy DE, Decker T. 2007. JAK-STAT signaling: from interferons to cytokines. J Biol Chem 282:20059–20063. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R700016200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yanai H, Negishi H, Taniguchi T. 2012. The IRF family of transcription factors: inception, impact and implications in oncogenesis. Oncoimmunology 1:1376–1386. doi: 10.4161/onci.22475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Platanias LC. 2005. Mechanisms of type-I- and type-II-interferon-mediated signalling. Nat Rev Immunol 5:375–386. doi: 10.1038/nri1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheon H, Holvey-Bates EG, Schoggins JW, Forster S, Hertzog P, Imanaka N, Rice CM, Jackson MW, Junk DJ, Stark GR. 2013. IFNbeta-dependent increases in STAT1, STAT2, and IRF9 mediate resistance to viruses and DNA damage. EMBO J 32:2751–2763. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Varinou L, Ramsauer K, Karaghiosoff M, Kolbe T, Pfeffer K, Muller M, Decker T. 2003. Phosphorylation of the Stat1 transactivation domain is required for full-fledged IFN-gamma-dependent innate immunity. Immunity 19:793–802. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(03)00322-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xia J, Gill EE, Hancock RE. 2015. NetworkAnalyst for statistical, visual and network-based meta-analysis of gene expression data. Nat Protoc 10:823–844. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2015.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Verweij MC, Wellish M, Whitmer T, Malouli D, Lapel M, Jonjic S, Haas JG, DeFilippis VR, Mahalingam R, Fruh K. 2015. Varicella viruses inhibit interferon-stimulated JAK-STAT signaling through multiple mechanisms. PLoS Pathog 11:e1004901. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arvin AM, Kushner JH, Feldman S, Baehner RL, Hammond D, Merigan TC. 1982. Human leukocyte interferon for the treatment of varicella in children with cancer. N Engl J Med 306:761–765. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198204013061301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park HB, Kim KC, Park JH, Kang TY, Lee HS, Kim TH, Jun JB, Bae SC, Yoo DH, Craft J, Jung S. 2004. Association of reduced CD4 T cell responses specific to varicella zoster virus with high incidence of herpes zoster in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol 31:2151–2155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Steain M, Sutherland JP, Rodriguez M, Cunningham AL, Slobedman B, Abendroth A. 2014. Analysis of T cell responses during active varicella-zoster virus reactivation in human ganglia. J Virol 88:2704–2716. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03445-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Honda K, Taniguchi T. 2006. IRFs: master regulators of signalling by Toll-like receptors and cytosolic pattern-recognition receptors. Nat Rev Immunol 6:644–658. doi: 10.1038/nri1900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martinez-Moczygemba M, Gutch MJ, French DL, Reich NC. 1997. Distinct STAT structure promotes interaction of STAT2 with the p48 subunit of the interferon-alpha-stimulated transcription factor ISGF3. J Biol Chem 272:20070–20076. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.32.20070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fink K, Grandvaux N. 2013. STAT2 and IRF9: beyond ISGF3. JAKSTAT 2:e27521. doi: 10.4161/jkst.27521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Banninger G, Reich NC. 2004. STAT2 nuclear trafficking. J Biol Chem 279:39199–39206. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400815200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson KE, Song B, Knipe DM. 2008. Role for herpes simplex virus 1 ICP27 in the inhibition of type I interferon signaling. Virology 374:487–494. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li Q, Means R, Lang S, Jung JU. 2007. Downregulation of gamma interferon receptor 1 by Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus K3 and K5. J Virol 81:2117–2127. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01961-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schaap A, Fortin JF, Sommer M, Zerboni L, Stamatis S, Ku CC, Nolan GP, Arvin AM. 2005. T-cell tropism and the role of ORF66 protein in pathogenesis of varicella-zoster virus infection. J Virol 79:12921–12933. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.20.12921-12933.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sen N, Che X, Rajamani J, Zerboni L, Sung P, Ptacek J, Arvin AM. 2012. Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) and survivin induction by varicella-zoster virus promote replication and skin pathogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109:600–605. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1114232109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ciccaglione AR, Stellacci E, Marcantonio C, Muto V, Equestre M, Marsili G, Rapicetta M, Battistini A. 2007. Repression of interferon regulatory factor 1 by hepatitis C virus core protein results in inhibition of antiviral and immunomodulatory genes. J Virol 81:202–214. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01011-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mboko WP, Mounce BC, Emmer J, Darrah E, Patel SB, Tarakanova VL. 2014. Interferon regulatory factor 1 restricts gammaherpesvirus replication in primary immune cells. J Virol 88:6993–7004. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00638-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nair S, Michaelsen-Preusse K, Finsterbusch K, Stegemann-Koniszewski S, Bruder D, Grashoff M, Korte M, Koster M, Kalinke U, Hauser H, Kroger A. 2014. Interferon regulatory factor-1 protects from fatal neurotropic infection with vesicular stomatitis virus by specific inhibition of viral replication in neurons. PLoS Pathog 10:e1003999. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ru J, Sun H, Fan H, Wang C, Li Y, Liu M, Tang H. 2014. MiR-23a facilitates the replication of HSV-1 through the suppression of interferon regulatory factor 1. PLoS One 9:e114021. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sen N, Sommer M, Che X, White K, Ruyechan WT, Arvin AM. 2010. Varicella-zoster virus immediate-early protein 62 blocks interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3) phosphorylation at key serine residues: a novel mechanism of IRF3 inhibition among herpesviruses. J Virol 84:9240–9253. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01147-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Law CW, Alhamdoosh M, Su S, Smyth GK, Ritchie ME. 2016. RNA-seq analysis is easy as 1-2-3 with limma, Glimma and edgeR. F1000Res 5:1408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huber W, Carey VJ, Gentleman R, Anders S, Carlson M, Carvalho BS, Bravo HC, Davis S, Gatto L, Girke T, Gottardo R, Hahne F, Hansen KD, Irizarry RA, Lawrence M, Love MI, MacDonald J, Obenchain V, Oles AK, Pages H, Reyes A, Shannon P, Smyth GK, Tenenbaum D, Waldron L, Morgan M. 2015. Orchestrating high-throughput genomic analysis with Bioconductor. Nat Methods 12:115–121. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK. 2010. edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 26:139–140. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ritchie ME, Phipson B, Wu D, Hu Y, Law CW, Shi W, Smyth GK. 2015. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res 43:e47. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Robinson MD, Oshlack A. 2010. A scaling normalization method for differential expression analysis of RNA-seq data. Genome Biol 11:R25. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-3-r25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Law CW, Chen Y, Shi W, Smyth GK. 2014. voom: precision weights unlock linear model analysis tools for RNA-seq read counts. Genome Biol 15:R29. doi: 10.1186/gb-2014-15-2-r29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smyth GK. 2004. Linear models and empirical Bayes methods for assessing differential expression in microarray experiments. Stat Appl Genet Mol Biol 3:Article3. doi: 10.2202/1544-6115.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK. 2009. Testing significance relative to a fold-change threshold is a TREAT. Bioinformatics 25:765–771. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lynch JM, Kenyon TK, Grose C, Hay J, Ruyechan WT. 2002. Physical and functional interaction between the varicella zoster virus IE63 and IE62 proteins. Virology 302:71–82. doi: 10.1006/viro.2002.1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stevenson D, Xue M, Hay J, Ruyechan WT. 1996. Phosphorylation and nuclear localization of the varicella-zoster virus gene 63 protein. J Virol 70:658–662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.