Abstract

Introduction

Worldwide, more than 20 million patients undergo groin hernia repair annually. The many different approaches, treatment indications and a significant array of techniques for groin hernia repair warrant guidelines to standardize care, minimize complications, and improve results. The main goal of these guidelines is to improve patient outcomes, specifically to decrease recurrence rates and reduce chronic pain, the most frequent problems following groin hernia repair. They have been endorsed by all five continental hernia societies, the International Endo Hernia Society and the European Association for Endoscopic Surgery.

Methods

An expert group of international surgeons (the HerniaSurge Group) and one anesthesiologist pain expert was formed. The group consisted of members from all continents with specific experience in hernia-related research. Care was taken to include surgeons who perform different types of repair and had preferably performed research on groin hernia surgery. During the Group’s first meeting, evidence-based medicine (EBM) training occurred and 166 key questions (KQ) were formulated. EBM rules were followed in complete literature searches (including a complete search by The Dutch Cochrane database) to January 1, 2015 and to July 1, 2015 for level 1 publications. The articles were scored by teams of two or three according to Oxford, SIGN and Grade methodologies. During five 2-day meetings, results were discussed with the working group members leading to 136 statements and 88 recommendations. Recommendations were graded as “strong” (recommendations) or “weak” (suggestions) and by consensus in some cases upgraded. In the Results and summary section below, the term “should” refers to a recommendation. The AGREE II instrument was used to validate the guidelines. An external review was performed by three international experts. They recommended the guidelines with high scores.

Results and summary

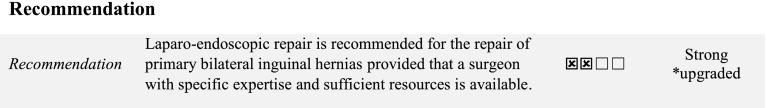

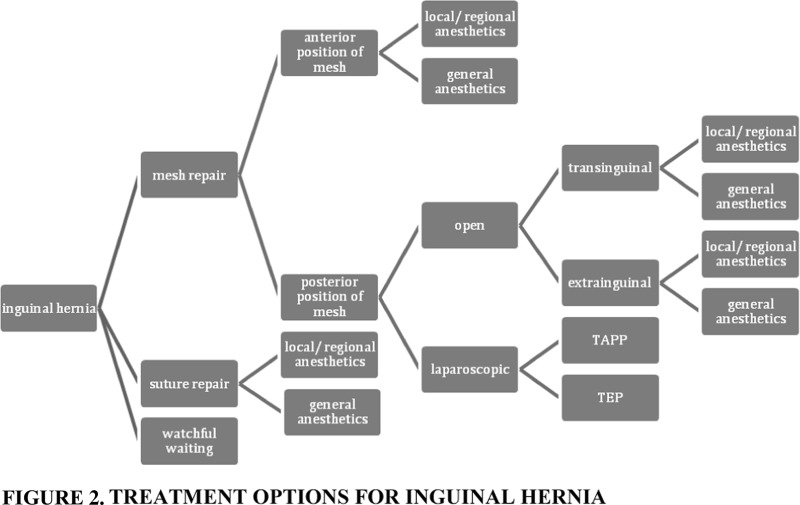

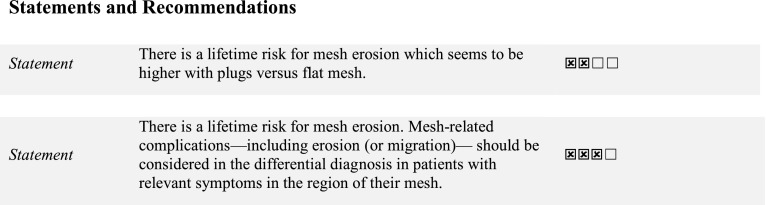

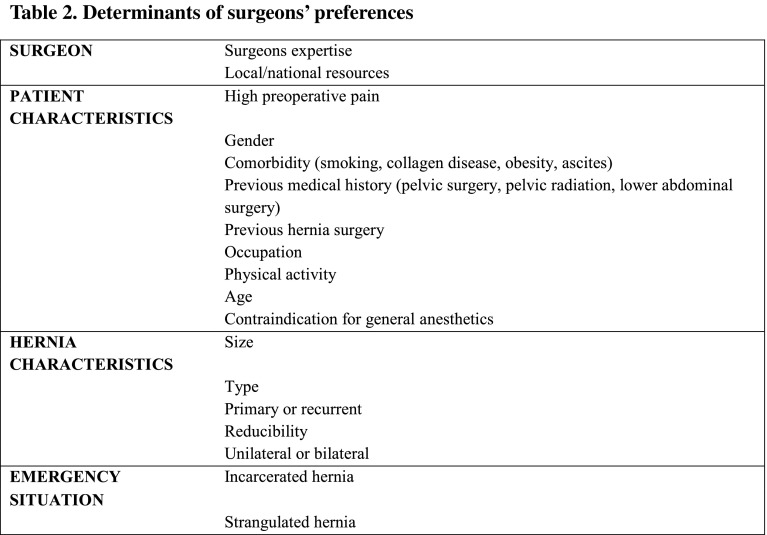

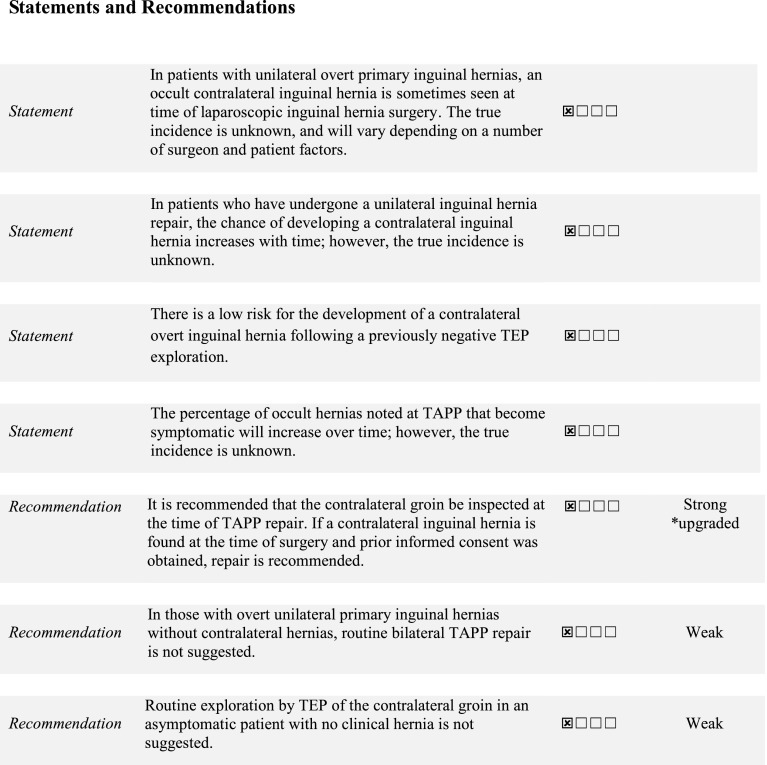

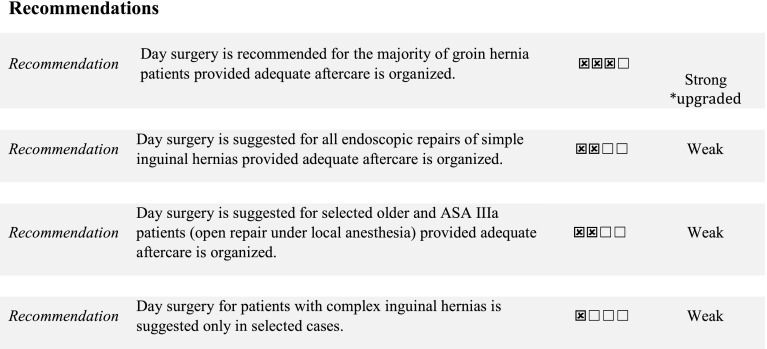

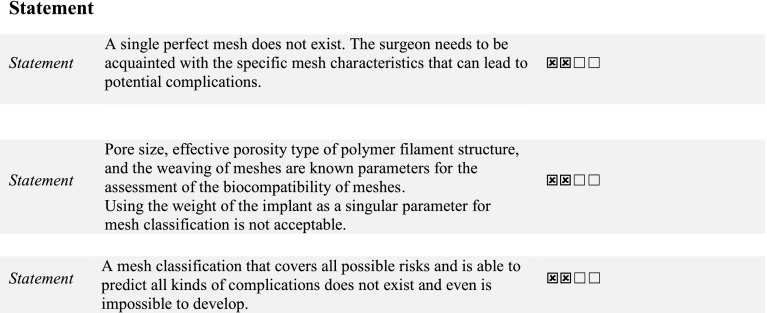

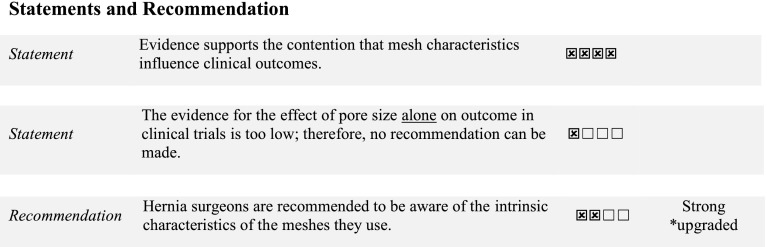

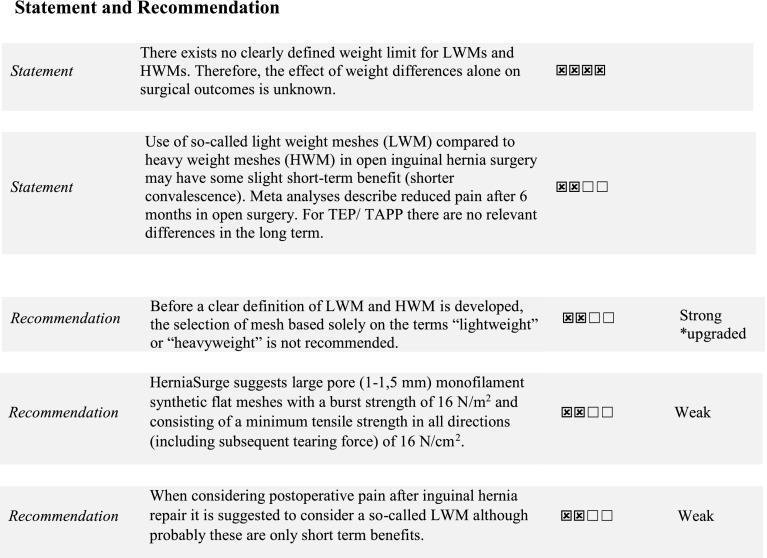

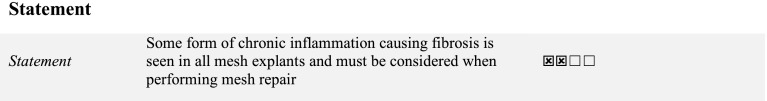

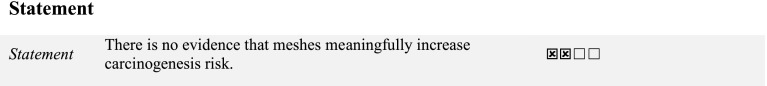

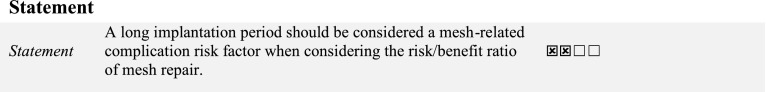

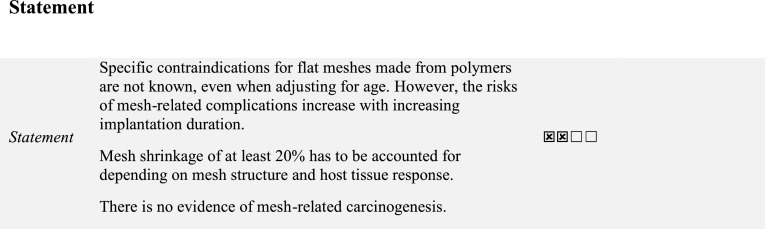

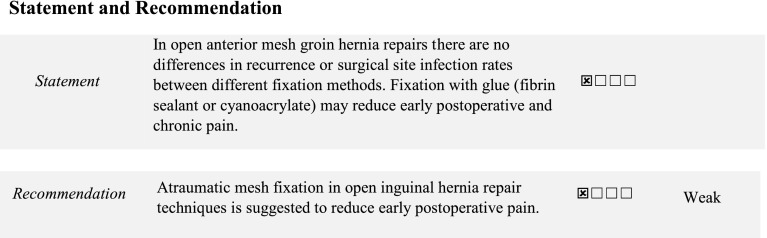

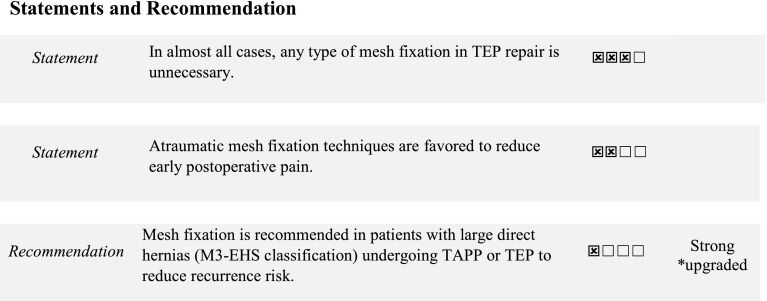

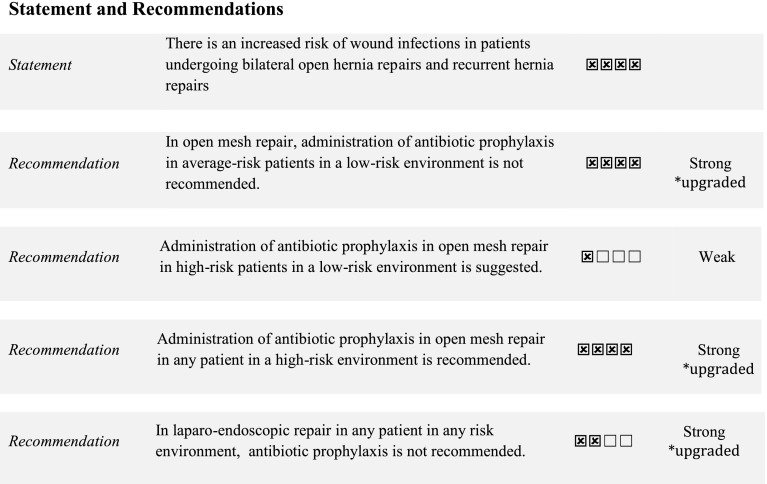

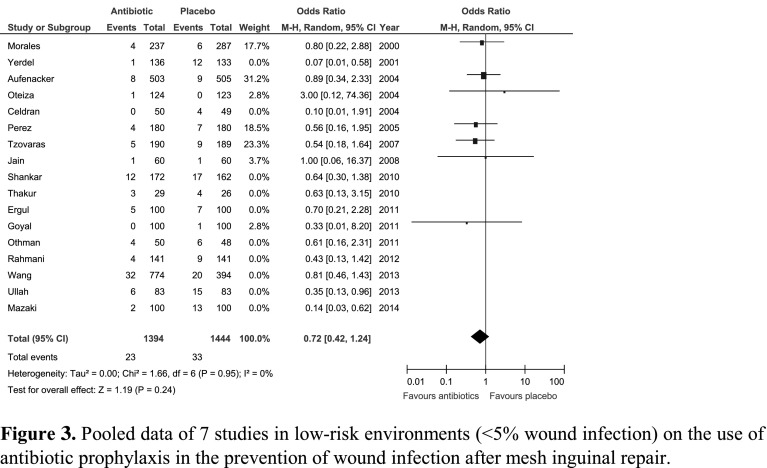

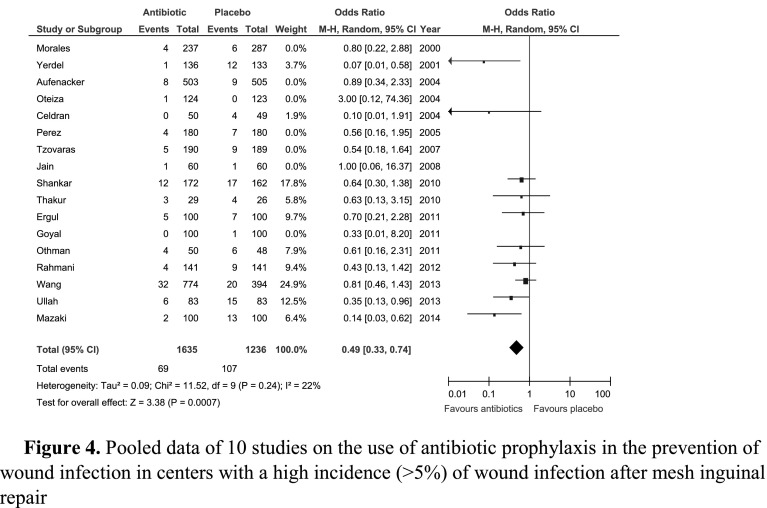

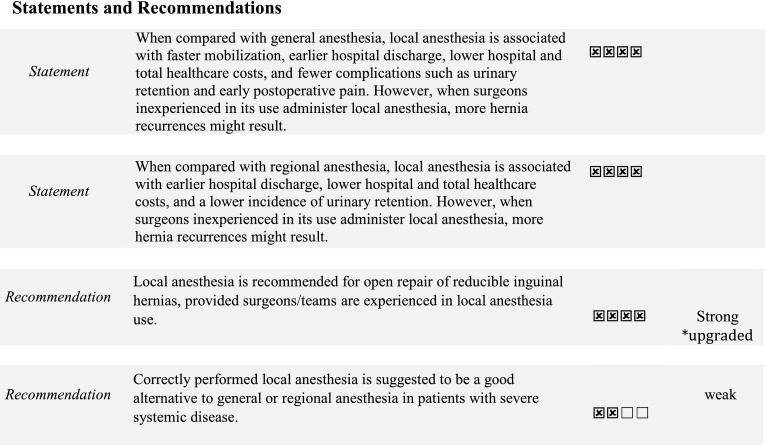

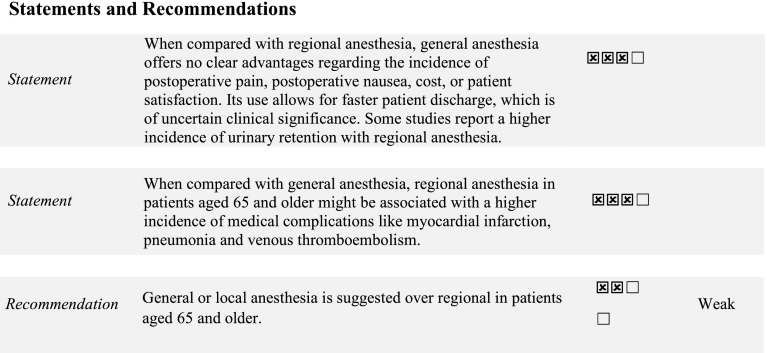

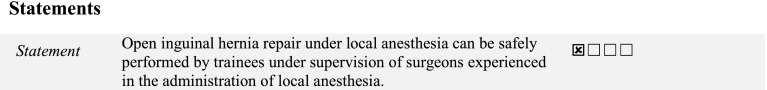

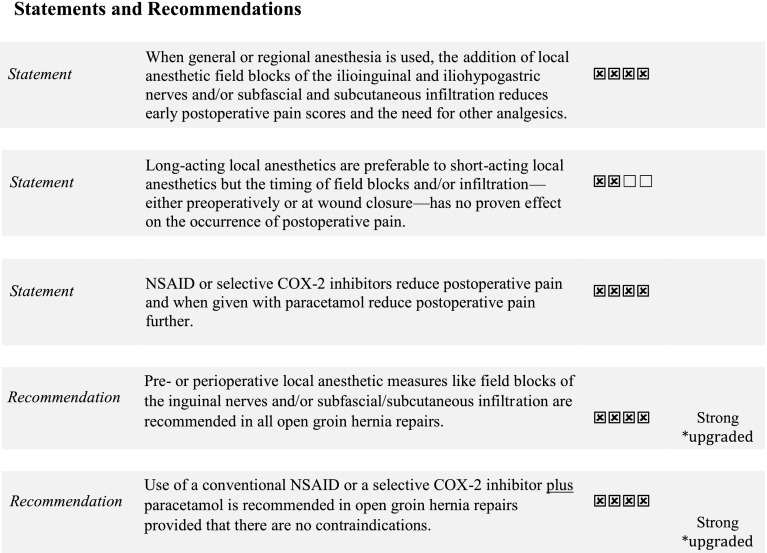

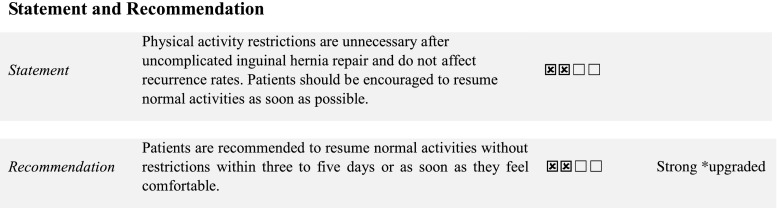

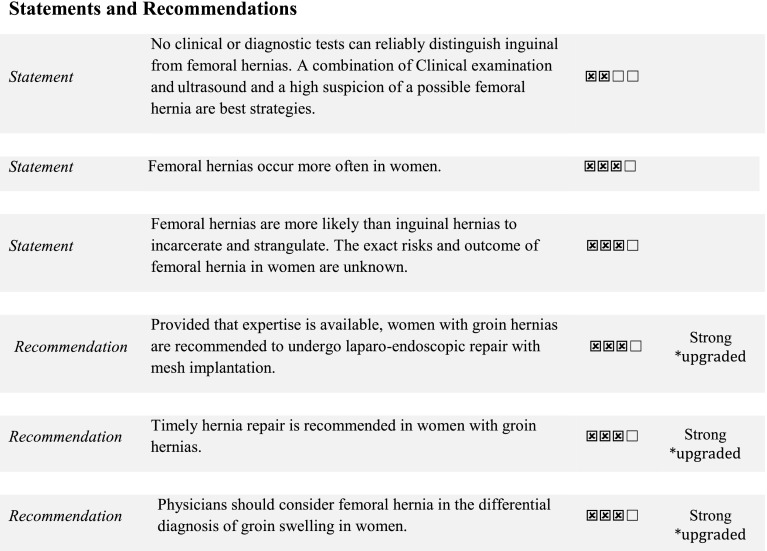

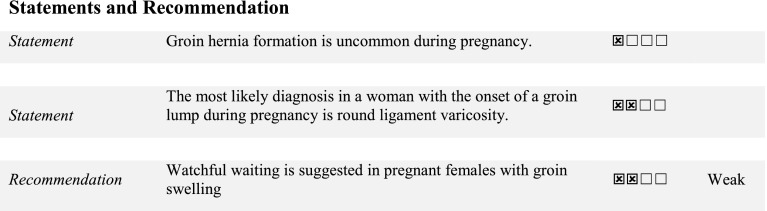

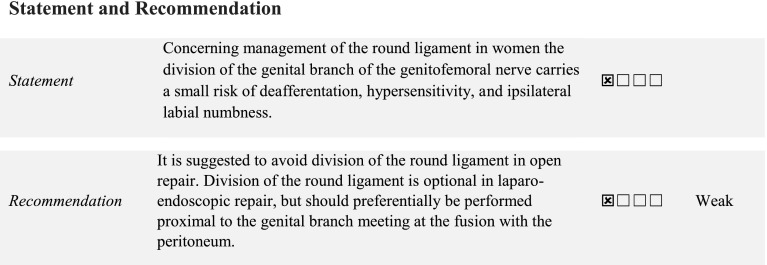

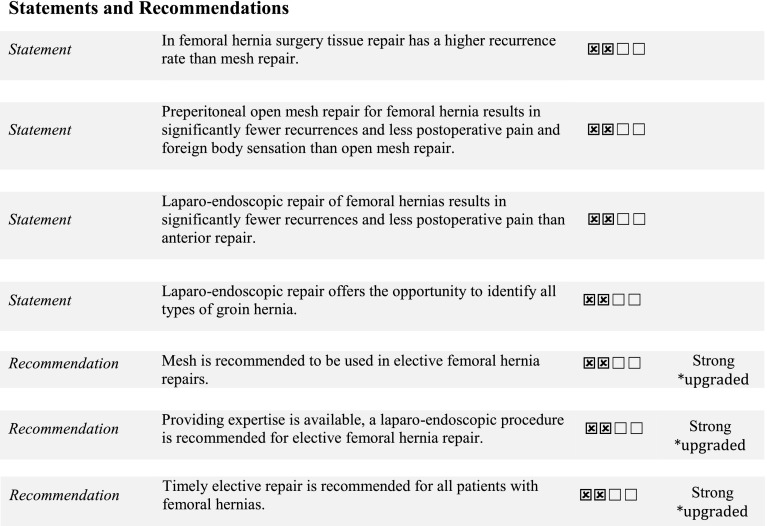

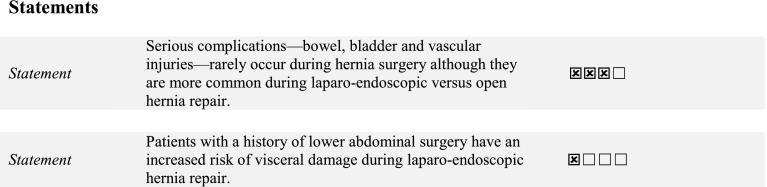

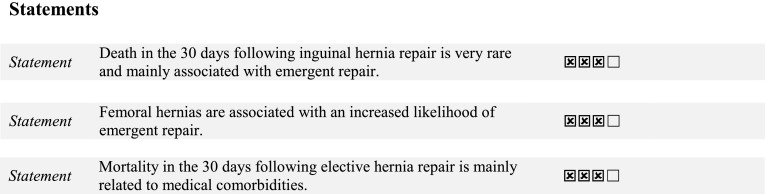

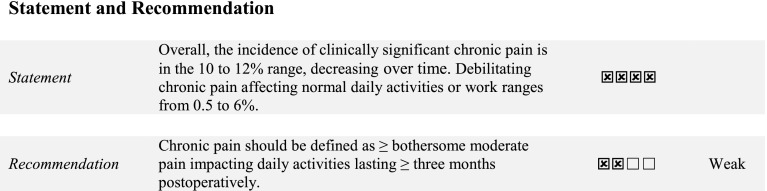

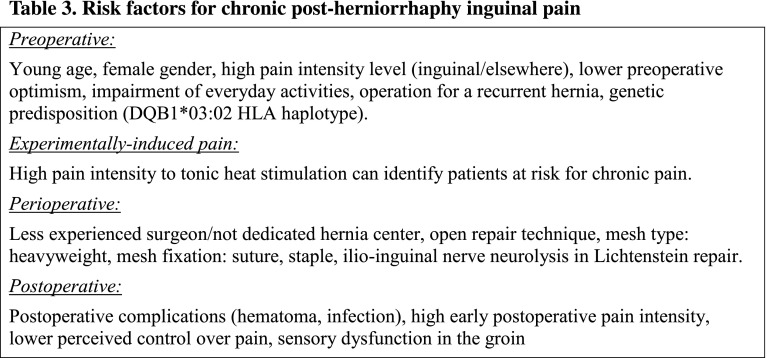

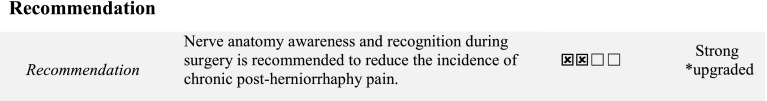

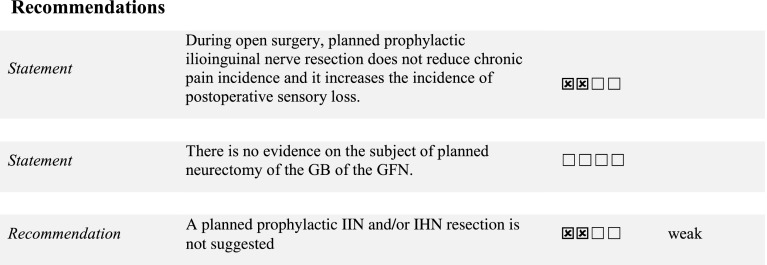

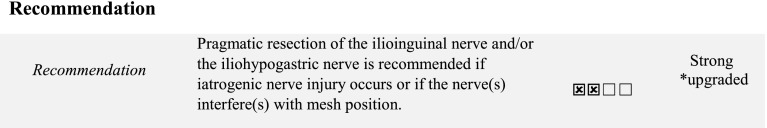

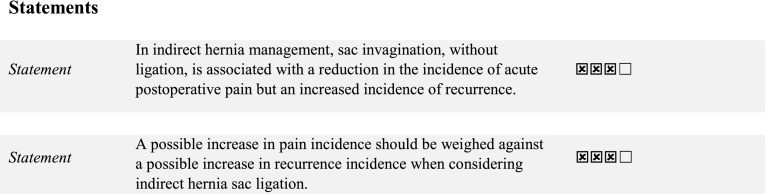

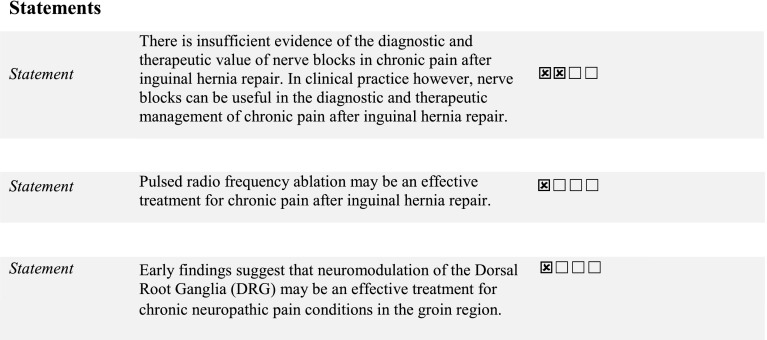

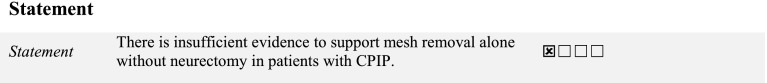

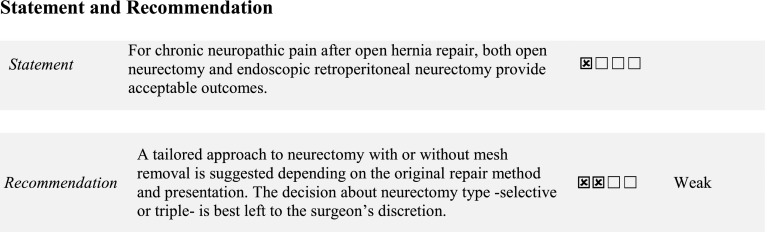

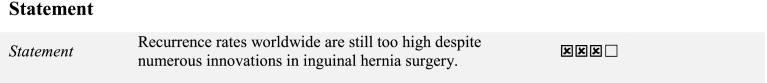

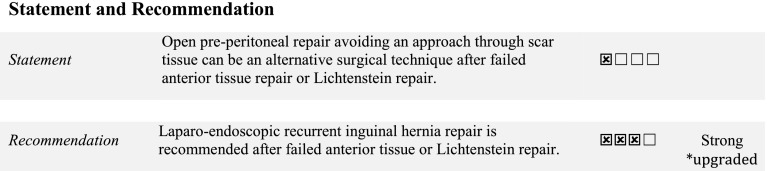

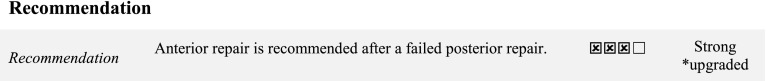

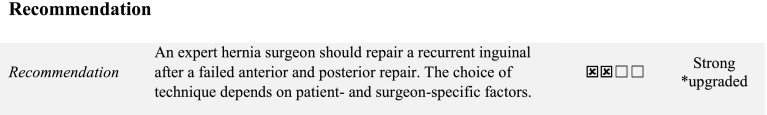

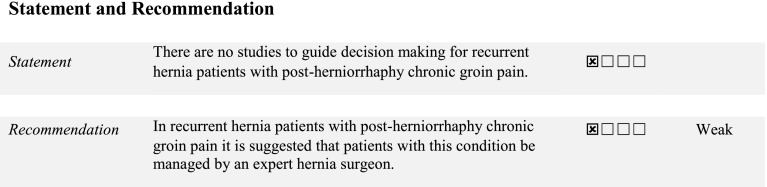

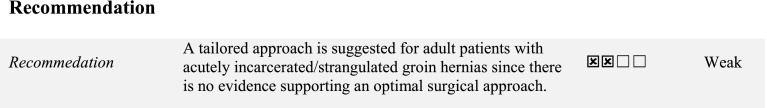

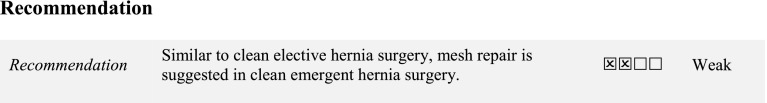

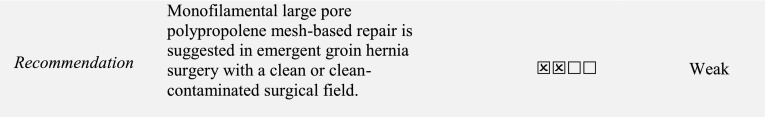

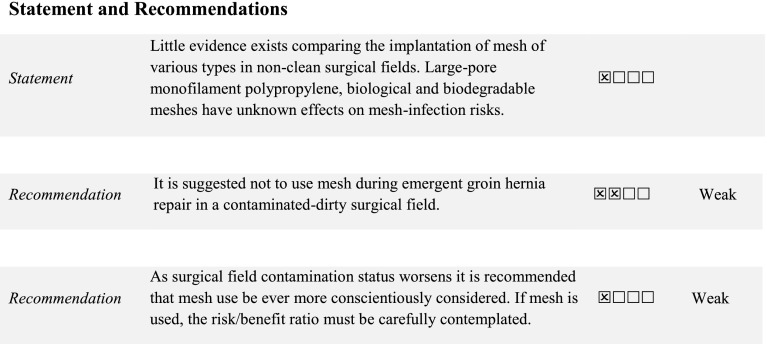

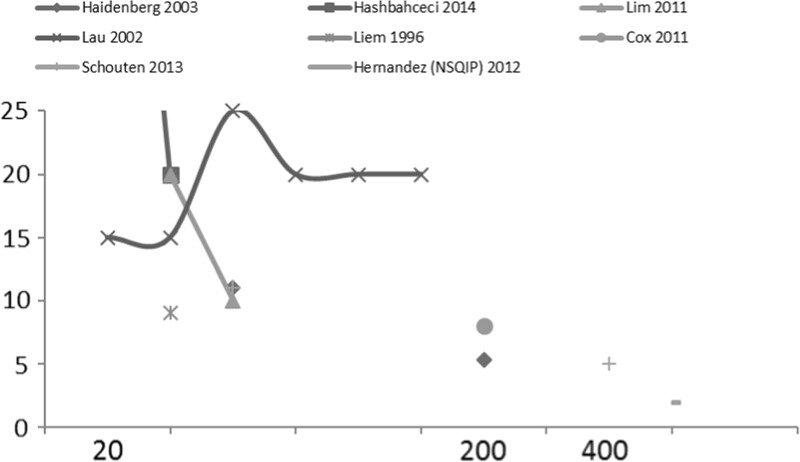

The risk factors for inguinal hernia (IH) include: family history, previous contra-lateral hernia, male gender, age, abnormal collagen metabolism, prostatectomy, and low body mass index. Peri-operative risk factors for recurrence include poor surgical techniques, low surgical volumes, surgical inexperience and local anesthesia. These should be considered when treating IH patients. IH diagnosis can be confirmed by physical examination alone in the vast majority of patients with appropriate signs and symptoms. Rarely, ultrasound is necessary. Less commonly still, a dynamic MRI or CT scan or herniography may be needed. The EHS classification system is suggested to stratify IH patients for tailored treatment, research and audit. Symptomatic groin hernias should be treated surgically. Asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic male IH patients may be managed with “watchful waiting” since their risk of hernia-related emergencies is low. The majority of these individuals will eventually require surgery; therefore, surgical risks and the watchful waiting strategy should be discussed with patients. Surgical treatment should be tailored to the surgeon’s expertise, patient- and hernia-related characteristics and local/national resources. Furthermore, patient health-related, life style and social factors should all influence the shared decision-making process leading up to hernia management. Mesh repair is recommended as first choice, either by an open procedure or a laparo-endoscopic repair technique. One standard repair technique for all groin hernias does not exist. It is recommended that surgeons/surgical services provide both anterior and posterior approach options. Lichtenstein and laparo-endoscopic repair are best evaluated. Many other techniques need further evaluation. Provided that resources and expertise are available, laparo-endoscopic techniques have faster recovery times, lower chronic pain risk and are cost effective. There is discussion concerning laparo-endoscopic management of potential bilateral hernias (occult hernia issue). After patient consent, during TAPP, the contra-lateral side should be inspected. This is not suggested during unilateral TEP repair. After appropriate discussions with patients concerning results tissue repair (first choice is the Shouldice technique) can be offered. Day surgery is recommended for the majority of groin hernia repair provided aftercare is organized. Surgeons should be aware of the intrinsic characteristics of the meshes they use. Use of so-called low-weight mesh may have slight short-term benefits like reduced postoperative pain and shorter convalescence, but are not associated with better longer-term outcomes like recurrence and chronic pain. Mesh selection on weight alone is not recommended. The incidence of erosion seems higher with plug versus flat mesh. It is suggested not to use plug repair techniques. The use of other implants to replace the standard flat mesh in the Lichtenstein technique is currently not recommended. In almost all cases, mesh fixation in TEP is unnecessary. In both TEP and TAPP it is recommended to fix mesh in M3 hernias (large medial) to reduce recurrence risk. Antibiotic prophylaxis in average-risk patients in low-risk environments is not recommended in open surgery. In laparo-endoscopic repair it is never recommended. Local anesthesia in open repair has many advantages, and its use is recommended provided the surgeon is experienced in this technique. General anesthesia is suggested over regional in patients aged 65 and older as it might be associated with fewer complications like myocardial infarction, pneumonia and thromboembolism. Perioperative field blocks and/or subfascial/subcutaneous infiltrations are recommended in all cases of open repair. Patients are recommended to resume normal activities without restrictions as soon as they feel comfortable. Provided expertise is available, it is suggested that women with groin hernias undergo laparo-endoscopic repair in order to decrease the risk of chronic pain and avoid missing a femoral hernia. Watchful waiting is suggested in pregnant women as groin swelling most often consists of self-limited round ligament varicosities. Timely mesh repair by a laparo-endoscopic approach is suggested for femoral hernias provided expertise is available. All complications of groin hernia management are discussed in an extensive chapter on the topic. Overall, the incidence of clinically significant chronic pain is in the 10–12% range, decreasing over time. Debilitating chronic pain affecting normal daily activities or work ranges from 0.5 to 6%. Chronic postoperative inguinal pain (CPIP) is defined as bothersome moderate pain impacting daily activities lasting at least 3 months postoperatively and decreasing over time. CPIP risk factors include: young age, female gender, high preoperative pain, early high postoperative pain, recurrent hernia and open repair. For CPIP the focus should be on nerve recognition in open surgery and, in selected cases, prophylactic pragmatic nerve resection (planned resection is not suggested). It is suggested that CPIP management be performed by multi-disciplinary teams. It is also suggested that CPIP be managed by a combination of pharmacological and interventional measures and, if this is unsuccessful, followed by, in selected cases (triple) neurectomy and (in selected cases) mesh removal. For recurrent hernia after anterior repair, posterior repair is recommended. If recurrence occurs after a posterior repair, an anterior repair is recommended. After a failed anterior and posterior approach, management by a specialist hernia surgeon is recommended. Risk factors for hernia incarceration/strangulation include: female gender, femoral hernia and a history of hospitalization related to groin hernia. It is suggested that treatment of emergencies be tailored according to patient- and hernia-related factors, local expertise and resources. Learning curves vary between different techniques. Probably about 100 supervised laparo-endoscopic repairs are needed to achieve the same results as open mesh surgery like Lichtenstein. It is suggested that case load per surgeon is more important than center volume. It is recommended that minimum requirements be developed to certify individuals as expert hernia surgeon. The same is true for the designation “Hernia Center”. From a cost-effectiveness perspective, day-case laparoscopic IH repair with minimal use of disposables is recommended. The development and implementation of national groin hernia registries in every country (or region, in the case of small country populations) is suggested. They should include patient follow-up data and account for local healthcare structures. A dissemination and implementation plan of the guidelines will be developed by global (HerniaSurge), regional (international societies) and local (national chapters) initiatives through internet websites, social media and smartphone apps. An overarching plan to improve access to safe IH surgery in low-resource settings (LRSs) is needed. It is suggested that this plan contains simple guidelines and a sustainability strategy, independent of international aid. It is suggested that in LRSs the focus be on performing high-volume Lichtenstein repair under local anesthesia using low-cost mesh. Three chapters discuss future research, guidelines for general practitioners and guidelines for patients.

Conclusions

The HerniaSurge Group has developed these extensive and inclusive guidelines for the management of adult groin hernia patients. It is hoped that they will lead to better outcomes for groin hernia patients wherever they live. More knowledge, better training, national audit and specialization in groin hernia management will standardize care for these patients, lead to more effective and efficient healthcare and provide direction for future research.

Keywords: Hernia, Inguinal hernia, Groin hernia, Femoral hernia, Inguinal hernia treatment, Inguinal hernia repair, Open inguinal hernia, Laparoscopic inguinal hernia, Shouldice, Lichtenstein, TEP, TAPP, Standard of care, Guideline, Practice guideline

Chapters

PART 1

Management of inguinal hernias in adults

Introduction

Risk factors for the development of inguinal hernias in adults

Diagnostic modalities

Groin hernia classification

Indications: treatment options for symptomatic and asymptomatic patients

Surgical treatment of inguinal hernias

Individualization of treatment options

Occult hernias and bilateral repair

Day surgery

Meshes

Mesh fixation

Antibiotic prophylaxis

Anesthesia

Postoperative pain: prevention and management

Convalescence

PART 2

Specific aspects of groin hernia management

-

16.

Groin hernias in women

-

17.

Femoral hernia management

-

18.

Complications: prevention and treatment

-

19.

Pain: prevention and treatment

-

20.

Recurrent inguinal hernias

-

21.

Emergency treatment of groin hernia

PART 3

Quality, research and global management

Quality aspects

-

22.

Training and the learning curve

-

23.

Specialized centers and hernia specialists

-

24.

Costs

-

25.

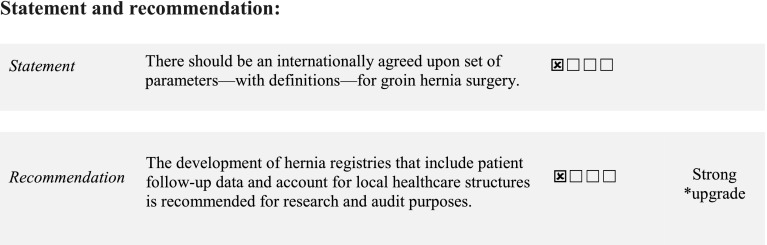

Registries

-

26.

Outcomes and quality assessment

-

27.

Dissemination and implementation

Global groin hernia management

-

28.

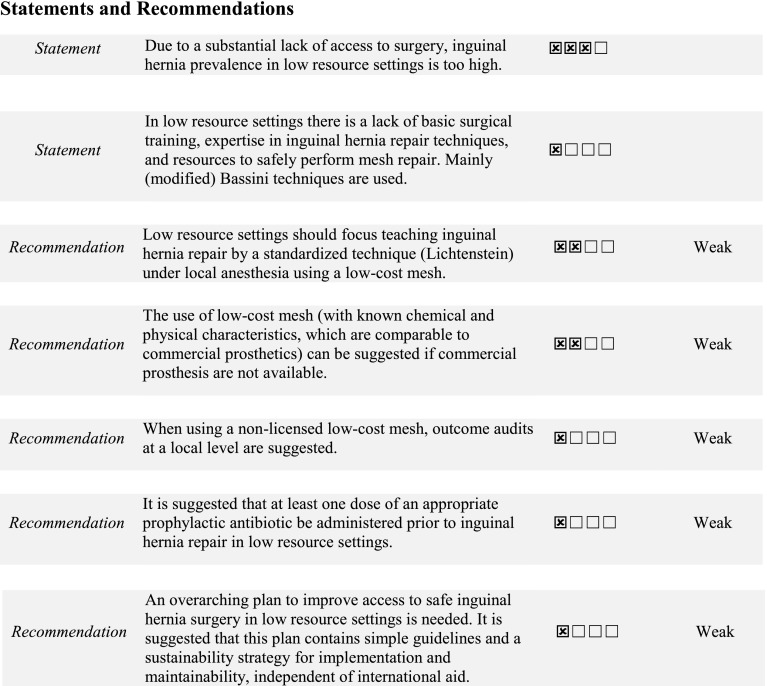

Inguinal hernia surgery in low-resource settings

Research, general practitioner and patient perspectives

-

29.

Questions for research

-

30.

Summary for general practitioners

-

31.

Management of groin hernias from patients’ perspectives

PART 1

Management of inguinal hernias in adults

Chapter 1

HerniaSurge: international guidelines for groin hernia management

Introduction

M. P. Simons, N. van Veenendaal, H. M. Tran, B. van den Heuvel and H. J. Bonjer

Lifetime occurrence of groin hernia—viscera or adipose tissue protrusions through the inguinal or femoral canal—is 27–43% in men and 3–6% in women.1 Inguinal hernias are almost always symptomatic; and the only cure is surgery.2 A minority of patients are asymptomatic but even a watch-and-wait approach in this group results in surgery in approximately 70% within 5 years.2

Worldwide, inguinal hernia repair is one of the most common surgeries, performed on more than 20 million people annually.1 Surgical treatment is successful in the majority of cases, but recurrences necessitate reoperations in 10–15% and long-term disability due to chronic pain (pain lasting longer than 3 months) occurs in 10–12% of patients. Approximately 1–3% of patients have severe chronic pain. This has a tremendous negative effect globally on health and healthcare costs.

However, better outcomes are definitely possible. Our objective is to improve groin hernia patient care worldwide by developing and globally distributing standards of care based on all available evidence and experience.

Currently, groin hernia treatment is not standardized. Three hernia societies have separately published guidelines aimed at both improving treatment and enhancing the education of surgeons involved in groin hernia treatment. In 2009, the European Hernia Society (EHS) published guidelines covering all aspects of inguinal hernia treatment in adult patients.3 The EHS guidelines were updated in 2014.4 The International Endo Hernia Society (IEHS) published guidelines in 2011 covering laparo-endoscopic groin hernia repair.5 In 2013, the European Association for Endoscopic Surgery (EAES) published a consensus document focused on aspects of laparo-endoscopic treatments.5, 6 These three societies began collaborating in 2014, concluding it was both necessary and logical to develop a universal set of guidelines for groin hernia treatment. “Groin Hernia Guidelines” was selected as the name for the collaborative effort since information on femoral hernias was included for the first time. A movement was launched to develop a state-of-the-art series of guidelines spearheaded by passionate hernia experts for all aspects of abdominal wall hernia treatment. The European societies—EHS, IEHS and EAES—invited scientific societies worldwide with a focus on groin hernias to participate. The project was named “HerniaSurge” (http://www.herniasurge.com), forged from the combination of “hernia” and “surge” as a metaphor for waves crossing all continents.

Evolution of groin hernia surgery

The first groin hernia surgeries were done during the end of the sixteenth century. They involved hernia sac reduction and resection and posterior wall reinforcement of the inguinal canal by approximating its muscular and fascial components. Subsequently, many hernia repair variants were introduced. Prosthetic material utilization commenced in the 1960s, initially only in elderly patients with recurrent inguinal hernias. Favorable long-term results of these mesh repairs encouraged adoption of mesh repair in younger patients. Presently, the majority of surgeons in the world favor mesh repair of inguinal hernias. In Denmark, with its complete IH repair statistics in a national database, mesh use is currently close to 100%.7 In Sweden, mesh use is above 99%.8 In the early 1980s, minimally invasive techniques for groin hernia repair were first performed and reported on in the scientific literature, adding another management modality. Laparoscopic Trans Abdominal Pre-Peritoneal (TAPP) and Totally Extra Peritoneal (TEP) endoscopic techniques, collectively, “laparo-endoscopic surgery”, have been developed as well.

The fact that so many different repairs are now done strongly suggests that a “best repair method” does not exist. Additionally, large variations in treatments result from cultural differences amongst surgeons, different reimbursement systems and differences in resources and logistical capabilities.

Surgeons searching for “best” treatment strategies are challenged by a vast diverse scientific literature, much of which is difficult to interpret and apply to one’s local practice environment. As noted, hernia repair techniques vary broadly, dependent upon setting. Mesh use probably varies from 0 to 5% in low-resource settings to 95% in settings with the highest resources. Currently, open mesh repair (mainly Lichtenstein repair) is still most frequently used. There are specialist hernia surgeons and specialized hospitals that promote non-mesh repair especially in patients with a low-risk profile for recurrence. Meshes used in gynecological operations have caused many lawsuits and the spin-off is a justified alertness by media and the public questioning its safety in inguinal hernia repair. There are concerns about influence of insurance companies and industry. There are patients that refuse the use of mesh.

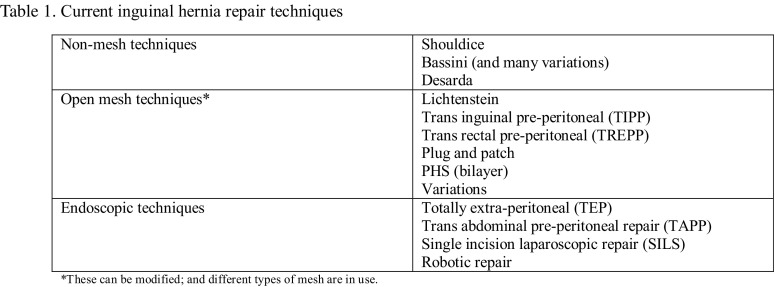

Laparo-endoscopic surgery use varies from zero to a maximum of approximately 55% in some high-resource countries. The average use in high-resource countries is largely unknown except for some examples like Australia (55%),9 Switzerland (40%),10 the Netherlands (45%) and Sweden (28%).8 Sweden has a national registry with complete coverage. Interesting are the following percentages for the year 2015: Lichtenstein 64%, TEP 25%, TAPP 3%, open pre-peritoneal mesh 3.3%, combined open and pre-peritoneal 2.7% and tissue repair in 0.8%. The German Herniamed registry which contains data on about 200,000 patients (not complete national coverage, so possibly biased) contains interesting information confirming that a wide variety of techniques are in use. The percentages over the period 2009–2016 were: TAPP 39%, TEP 25%, Lichtenstein 24%, Plug 3%, Shouldice 2.6%, Gilbert PHS 2.5% and Bassini 0.2%. Other reliable data from Asia and America are lacking and often outdated once published. Table 1 indicates current hernia repair techniques.

Future directions

Standardizing groin hernia repairs and improving outcomes requires that many questions be answered. Best operative techniques should have the following attributes: low incidence of complications (pain and recurrence), relatively easy to learn, fast recovery, reproducible results, and cost effectiveness. Treatment of groin hernia patients will improve if we honor all stakeholders’ interests (patients, hospitals, surgeons and society).

Worldwide, groin hernia surgery outcomes need improvement. Recurrence rates—as measured by the proxy of reoperations—still range from 10 to 15%; although the increasing use of mesh has resulted in falling recurrence rates.11 There are great concerns about the complication of chronic pain which still occurs in 10–12% of patients.

Our process

The HerniaSurge guidelines that follow have been developed to address all questions concerning groin hernia repair in adults, worldwide. They contain recommendations for all groin hernia types, in all kinds of patients and in all parts of the world. It has been written by and endorsed by experts from every continent and from all the major hernia societies—European, Americas, Asia-Pacific, Afro-Middle-East and Australasian. Fifty expert surgeons from 19 countries crafted these state-of-the-art guidelines. We consider this work a “living document”, open to interpretation, modification and improvement over time with increasing experience and knowledge.

The involved experts have extensive clinical and scientific experience and a combined scholarly output of hundreds of publications focused on various aspects of groin hernia management. They are experienced in open non-mesh, open mesh and both TEP and TAPP techniques. The HerniaSurge steering committee has done its best to include and honor all treatment approaches, without prejudice and self-interest. Although evidence in the scientific literature forms the foundation for the guidelines, we searched to incorporate patients’ wishes and surgeon’s expectations. Factors like financial resources and logistics were taken into account as well. Our aim was to offer unbiased guidance to all surgeons and patients wherever they reside.

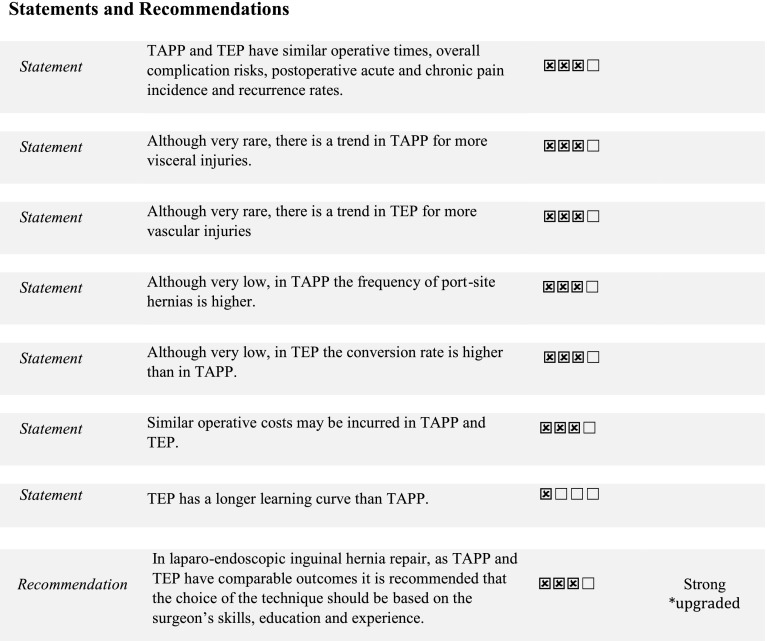

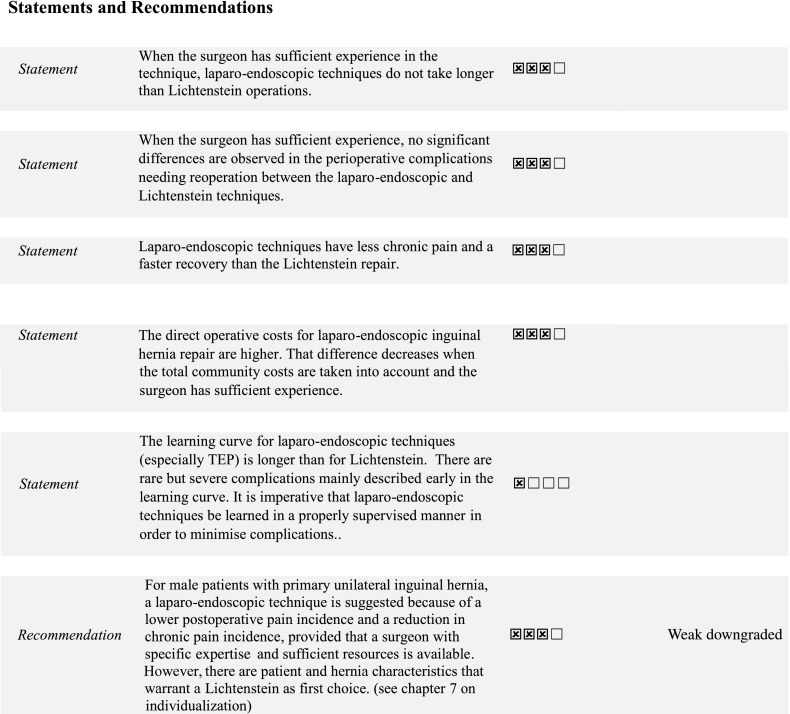

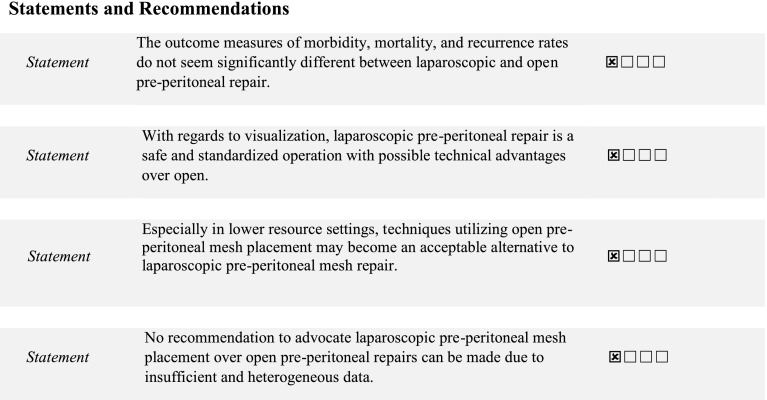

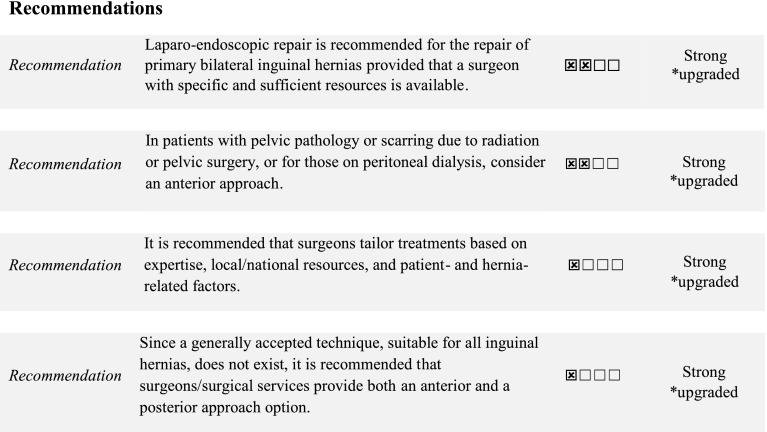

Guideline formulation

The HerniaSurge guidelines are developed according to the AGREE instrument II (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation). They are not a textbook, so extensive background information is not included. However, they represent the results of an extensive literature search spanning to 1 January 2015 for systematic reviews and to 1 July 2015 for randomized controlled trials and best evidence. During five 2-day meetings (Amsterdam April 2014, Edinburgh June 2014, Warsaw October 2014, Cologne February 2015 and Milano April/May 2015) and a 4-day meeting in Amsterdam in September 2015, a standard evidence-based process was rigorously used. Teams of two or three HerniaSurge members performed standard search strategies and scored greater than 3500 articles according to Oxford, SIGN and Grade methodology.12, 13 Level of evidence was first graded up or down by teams and later in all recommendations by the whole committee. Then, the statements and recommendations were developed and these were also graded during three consensus meetings. Statements are scored according to the levels very low, low, moderate or high. The recommendations contain the terms “recommend” when strong and “suggest” when weak. The grading consists of moving up or down in level after discussing the evidence in HerniaSurge meetings (Fig. 1). The first consensus was sought within the committee of 50 surgeons. The second consensus was sought via the internet and the final consensus during the EHS Rotterdam meeting of June 2016. The results of the consensus studies (including further consensus meetings during the APHS in October 2016 and AHS in March 2017 meetings) will be published separately. This strategy of combining evidence and expert opinion by consensus led to some very strong recommendations that not only reflect the evidence in literature, but also truly reflect the opinions of 50 international leaders in groin hernia surgery. Expert opinion in this case is the opinion of the entire committee. For some important recommendations, long and passionate discussions led to the consensus found in these guidelines. Our discussions transcended countries and cultures and withstood pressures from finance and/or industry-motivated opinions. Statements and recommendations sometimes strongly favor certain treatments but are not necessarily suited to use in all parts of the world depending on local tradition, training capabilities and/or resources. The adage applies that any technique, thoroughly taught and frequently performed with good results, is valid. Some techniques are easily learned and offer good results whilst others might be very difficult to master but offer great results. All these techniques are highly dependent on the surgeon’s knowledge of anatomy, caseload and dedication to groin hernia surgery.

HerniaSurge would like to stress the importance of shared decision-making with patients. Type of hernia, patient profile, surgeons’ expertise, patient’s wishes and expectations, logistical possibilities and local resources are all key factors that finally lead to a treatment advice.

All search strategies, tables with articles and background information will be published on HerniaSurge’s website (https://www.herniasurge.com). All articles are filed per chapter in Mendeleyr reference manager.

We would like to emphasize the fact that the “International Guidelines for Groin Hernia Management” is NOT a legal document, merely guidelines. If surgeons choose not to follow strong recommendations, they should do so in consultation with their patients and document this in the medical record.

HerniaSurge encourages the establishment of local and national registries because they are valuable for audit and research. HerniaSurge predicts an increase in training of hernia specialist surgeons and the formation of hernia centers, but acknowledges that training and educating general surgeons who work in general practice in the short-term will have a greater impact on the results of groin hernia surgery. Furthermore, HerniaSurge is committed to develop E-learning modules and a “HerniaSurge App” to aid surgeons and patients around the world.

The HerniaSurge Group has formulated a large number of new research questions. The guidelines will be updated every 2 years as new evidence is published. The expiration date for this document is June 1, 2018.

The guidelines were externally reviewed by professors Jeekel (Europe), Ramshaw (USA) and Sharma (Asia). The Agree scores are published in the website of HerniaSurge (https://www.herniasurge.com).

Chapter 2

Risk factors for the development of inguinal hernias in adults

L. N. Jorgensen, W. W. Hope, and T. Bisgaard

Introduction

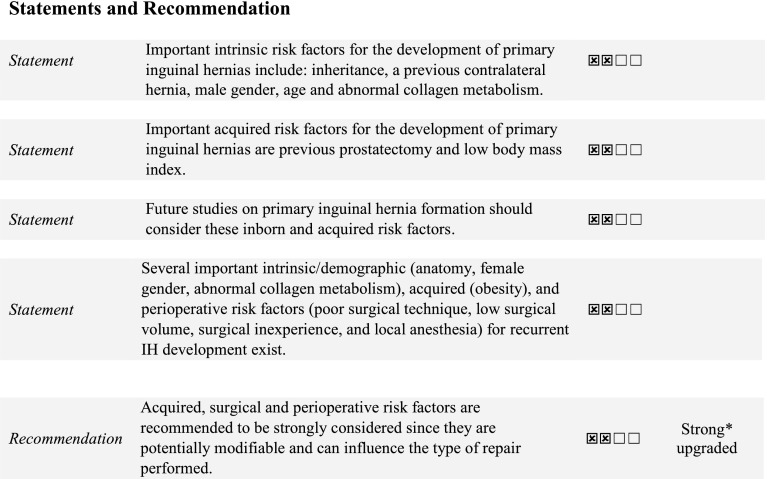

Numerous risk factors exist for the development of primary inguinal hernias (IH) and recurrent inguinal hernias (RIH) in adults, some better studied than others. These risk factors span a range, from acquired to genetic and modifiable to immutable. Some are under the surgeon’s control, but many are not.

For the purposes of this chapter (unless stated otherwise), IH repair is considered synonymous with IH diagnosis. The studies referenced below do not distinguish between open and laparo-endoscopic repairs or between direct and indirect hernias. Femoral hernias are not considered in this review nor are IHs in children except for a brief mention.

Key questions

KQ02.a What are the risk factors for the development of primary inguinal hernias in adults?

KQ02.b What are the acquired, demographic and perioperative risk factors for recurrence after treatment of IH in adults?

Evidence in literature

A medical literature search for primary IH risk factors identified 989 studies. Included are a discussion of one systematic review, two randomized controlled trials (RCTs), 24 cohort or registry studies, five case–control studies and five diagnostic studies in the material below.

A medical literature search for RIH risk factors identified 1191 studies. A discussion follows of two systematic reviews, two RCTs, 31 cohort or registry studies, one case–control study and four diagnostic studies.

Primary inguinal hernia

The lifelong cumulative incidence of IH repair in adults is 27–42.5% for men and 3–5.8% for women.14–17

Risk factors associated with IH formation (evidence level—high):

Inheritance (first degree relatives diagnosed with IH elevates IH incidence, especially in females).18, 19

Gender (IH repair is approximately 8–10 times more common in males).

Age (peak prevalence at 5 years, primarily indirect and 70–80 years, primarily direct).16, 20–22

Collagen metabolism (a diminished collagen type I/III ratio).

Obesity (inversely correlated with IH incidence).19, 21, 36–38

Risk factors associated with IH formation (evidence level—moderate):

Primary hernia type (both indirect and direct subtypes are bilaterally associated).39

Increased systemic levels of matrix metalloproteinase-2.40–43

Rare connective tissue disorders (e.g. Ehlers–Danlos syndrome).44

Risk factors associated with IH formation (evidence level—low):

Race (IHs are significantly less common in black adults).21

Tobacco use (inversely correlated with IH incidence).37

Socio-occupational factors.

There is contradictory evidence that social class, occupational factors and work load affect the risk of IH repair.46, 47 Heavy lifting may predispose to IH formation.48

Risk factors associated with IH formation (evidence level—very low):

Liver disease, renal disease and alcohol consumption have not been properly investigated to determine if they are risk factors for IH formation.

Recurrent inguinal hernia

Risk factors for RIH with a high level of evidence include female gender,49–59 direct versus indirect IH,58, 59 annual IH repair volume of less than five cases60 and limited surgical experience.56, 61–68 However, this last risk factor may be modifiable by surgical coaching.69–72

Risk factors for RIH with a moderate level of evidence include: presence of a sliding hernia,73 a diminished collagen type I/III ratio,40, 74, 75 increased systemic matrix metalloproteinase levels,42, 59, 74, 75 obesity37, 59 (although questioned in two very small studies57, 76) and open hernia repair under local anesthesia by general surgeons.53, 77 A recent meta-analysis examining features of 100,000–200,000 repairs demonstrated that size (< 3 versus ≥ 3 cm) and bilaterality did not affect the risk of recurrence.59

Incorrect surgical technique is likely the most important reason for recurrence after primary IH repair. Within this broad category of poor surgical technique are included: lack of mesh overlap, improper mesh choice, lack of proper mesh fixation, amongst others.

Several other potential risk factors have not been well studied or have low or very low levels of evidence supporting an association. Early postoperative hematoma formation78 and emergent surgery50, 52, 58, 59 may be risk factors for hernia recurrence but the association is not conclusive. Low (1–7 drinks/week) versus no ethanol consumption may protect against hernia recurrence. The effect of high ethanol consumption is unclear.53 Increased age,57, 59, 79, 80 COPD,57, 59, 76–82 prostatectomy,76 surgical site infection,78, 83 cirrhosis,84 chronic constipation,76 a positive family history.80, 85 and smoking.53, 57, 80, 85 have not been consistently shown to be risk factors for RIH. Incompletely studied factors which may impact the risk of IH recurrence are chronic kidney disease, social class, occupation, work load, pregnancy, labor, race and postoperative seroma occurrence.

Conclusion: several demographic (anatomy, female gender, abnormal collagen metabolism), acquired (obesity), and perioperative risk factors (insufficient surgical technique, low surgical volume, surgical inexperience and local anesthesia) for RIH were identified. Risk factors for IH and RIH are not comparable. In daily surgical practice, attention should be paid to perioperative surgical factors as they are modifiable. Allocation arms in future outcome studies should be balanced according to these demographic and acquired risk factors.

Chapter 3

Diagnostic modalities

H. Niebuhr, M. Pawlak and M. Śmietański

Introduction

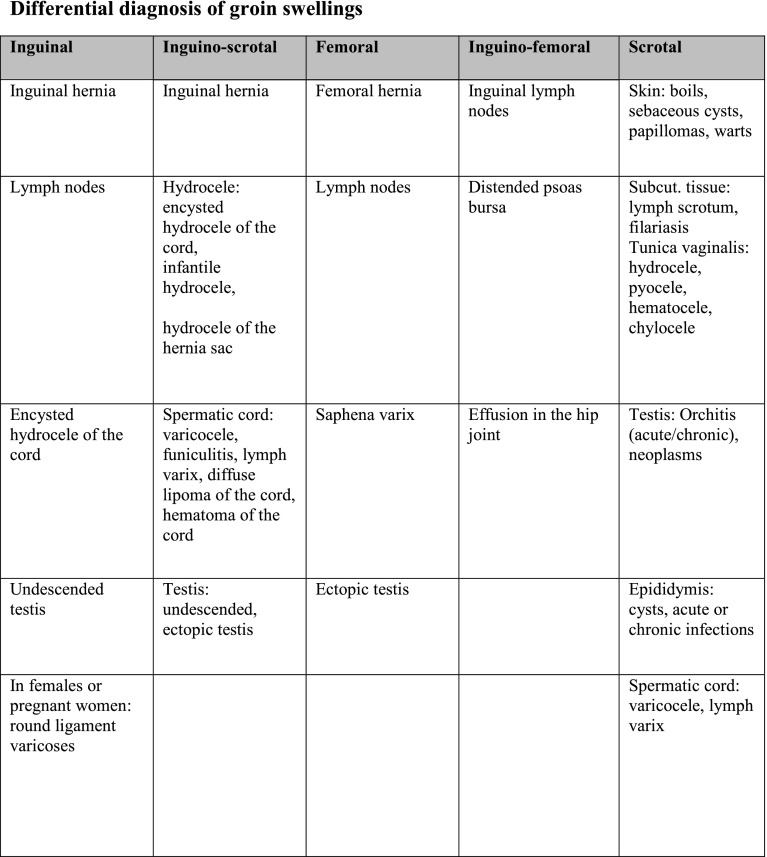

History and clinical examination are usually all that are required to confirm the diagnosis of a clinically evident groin hernia. Imaging may be required if there is vague groin swelling and diagnostic uncertainty, poor localization of swelling, intermittent swelling not present at time of physical examination, and other groin complaints without swelling.

An apparent hernia with clear clinical features such as a reducible groin bulge with local discomfort usually requires no further investigation. However, when patients present with groin complaints and hernia is not clearly the diagnosis, the question arises about which imaging modality to use. Ultrasonography (US) is now widely available but rarely magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computed tomography (CT) and herniography may play a role as well. Laparoscopy is not generally considered part of the diagnostic process for groin complaints and bulges and is not considered further in this chapter.

Key questions

KQ03.a Which diagnostic modality is the most suitable for diagnosing groin hernias?

KQ03.b Which diagnostic modality is the most suitable for diagnosing patients with obscure pain or doubtful swelling?

KQ03.c Which diagnostic modality is the most suitable for diagnosing recurrent groin hernias?

KQ03.d Which diagnostic modality is the most suitable for diagnosing the course of chronic pain after groin hernia surgery?

Evidence in literature

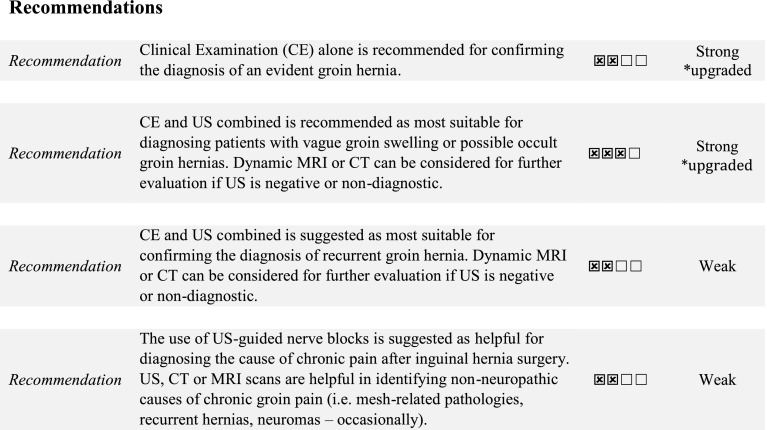

The gold standard for hernia diagnosis is clinical examination (CE) of the groin with a sensitivity of 0.745 and a specificity of 0.963 reported in a prospective cohort study from 1998.86 Three consensus guidelines have been published on groin hernia treatment.3, 6, 87 All published statements on diagnostic workup are weak, mainly focusing on CE alone. Only groin pain that is obscure or groin swelling of unclear origin (possible occult hernia) are noted to require further diagnostic investigation.88, 89 No consensus exists presently on the best imaging modality for these diagnostic dilemmas.

CE alone can miss hernias, especially those that are small (e.g. femoral hernias in obese women and men) and multiple hernias where only some of the hernias are apparent with physical examination.90 US, MRI, CT and herniography have all been studied in various settings in an attempt to close this “diagnostic gap”.88, 91–104

Two studies with a total of 510 patients showed that US is highly sensitive and a useful way to identify hernias.88, 96 Several other studies have echoed this finding.89, 100, 101, 103

The 1999 prospective cohort study showed that US had a specificity of 0.945 and a sensitivity of 0.815 for detecting groin hernias.86 MRI demonstrated a specificity of 0.963 and a sensitivity of 0.945.86 A 2013 meta-analysis revealed that groin US had a specificity of 0.86 and a sensitivity of 0.77.105

Two studies support the use of CE in combination with US to confirm the diagnosis of inguinal hernias. CE plus US was found to be superior to CE alone in both studies.89, 96

Two prospective cohort studies—both of low quality—showed that US performed poorly in the detection of occult groin hernias.106, 107 Both studies did recommend the use of US for interval assessment of patients with equivocal findings since those with equivocal findings seem to have a high incidence of groin hernias.

In conclusion, challenging hernia diagnoses like femoral and clinically occult hernias can be evaluated with US since it is: routinely available, relatively specific, cost effective, repeatable, useful in diagnosing other conditions, delivers no ionizing radiation and well accepted by patients.86, 88–90, 106–114

In pregnant women, colour-duplex US is useful for an entity presenting with an inguinal lump and pain, round ligament varicosity.109, 115, 116

When groin US is negative or non-diagnostic, dynamic MRI, dynamic CT and even herniography may be considered in an attempt to establish a diagnosis.117 Dynamic in this context refers to Valsalva manoeuvre during testing in an attempt to force a possibly occult or small hernia into its abnormal channel and more clearly demonstrate its presence. Herniography can only diagnose hernias, not other pathologies. MRI can diagnose adductor tendonitis, pubic osteitis, hip arthrosis, bursitis iliopectinea, and endometriosis amongst other conditions. If these ailments are part of the differential diagnosis, then MRI is the most suitable diagnostic tool.118, 119 CT can diagnose hernias as well and should be used when US is negative and MRI is not possible.

CE plus US is recommended as most suitable for the evaluation of patients suspected of having recurrent groin hernias. If diagnostic doubt exists after CE and US, MRI or CT should be considered. One prospective study and one retrospective case–control study, both of low quality, have addressed the issue of imaging for groin hernia recurrence.120, 121

US, CT or MRI scans are helpful in identifying non-neuropathic causes of chronic groin pain by identifying mesh-related pathologies, recurrent hernias and occasionally neuromas.122 A tailored, thoughtful approach to imaging is required since each of these imaging modalities possesses certain strengths and weaknesses and is not equally suited to diagnose all the listed conditions.

The use of US-guided nerve blocks is helpful in diagnosing the cause of chronic pain after surgery. A prospective cohort study described that the US-guided transversus abdominis plane block provided better the cause of pain and control than blind ilio-hypogastric nerve block after inguinal hernia repair.123 Considering the much higher number of patients (n = 273) compared to a randomized controlled trial with 24 included patients the quality rating of this Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS) could be determined as “moderate”.124 In another publication, the authors renounced the use of imaging as a helpful way to diagnose the cause of postoperative inguinal pain.104 In short, it seems that US-guided nerve blocks are helpful in pinpointing the cause of chronic pain after groin hernia repair. Due to a lack of new studies and conflicting results in the available literature, the evidence supporting our recommendation on this KQ is considered “weak”.

Chapter 4

Groin hernia classification

D. Cuccurullo and G. Campanelli

Introduction

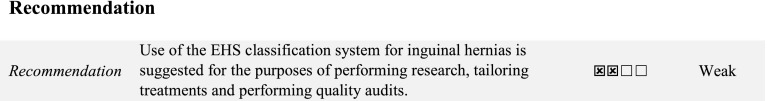

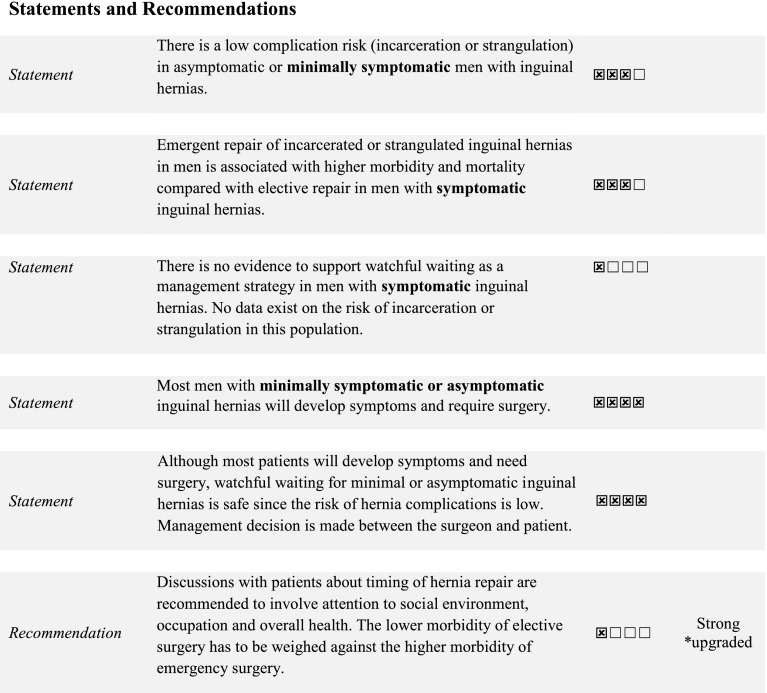

In day-to-day surgical practice a classification system for groin hernias is seldom used other than to describe hernia types in general terms (lateral/indirect, medial/direct, recurrent, and femoral). However, a consensus classification system is needed in order to perform research, tailor treatments to hernia types, and perform quality audits. Presently it is uncertain which hernia classification system is most suited to achieving this purpose.

Key questions

KQ04.a Is a groin hernia classification system necessary, and if so, which classification system is most appropriate?

Evidence in literature

The 2009 EHS guidelines recommended that the EHS classification system be used.3 A 2015 literature review failed to reveal new proposed classification systems or new evidence on the value of the EHS system.125 However, it is the opinion of the HerniaSurge members that one uniform system be adopted.

For inguinal hernia repairs, it is increasingly clear that surgeons tailor techniques to suit various patients and different hernia types. It is also necessary to compare results across different techniques and perform medical audits. More hernia registries are recommended and will require that a consensus classification system be adopted. However, for now there is no consensus amongst general surgeons or hernia specialists on a preferred system.

The primary purpose of any disease classification system is to allow for severity stratification so that reasonable comparisons can be made between treatment strategies.125 Additionally, a classification system must be simple and easy to use. Given the large number of operative techniques and their variations for groin hernia repair, it appears that no one classification system can satisfy all presently. However, an expert panel analyzed the known systems to date (Nyhus, Gilbert, Rutkow, Schumpelick, Harkins, Casten Halverson, McVay, Lichtenstein, Bendavid, Stoppa, Alexandre and Zollinger) and developed the EHS system by consensus.125–132 HerniaSurge suggests this system be used since it fulfills most requirements and is relatively simple to use.

The EHS system was not developed to classify hernia types preoperatively. This is a disadvantage. It is suggested that complex cases be managed by hernia specialists. A classification to inform decision-making about these complex cases would be helpful. However, many complex cases are easy to describe and do not require further classification (e.g. multiple recurrences and chronic pain).

For a detailed explanation please see the publication.125

For now, the classification system for groin hernias is mired in some controversy and disagreement. However, the best available evidence and expert opinion supports the adoption of the EHS system as classification system refinements evolve.

Chapter 5

Indications: treatment options for symptomatic and asymptomatic patients

B. van den Heuvel, A. R. Wijsmuller and R. J. Fitzgibbons

Introduction

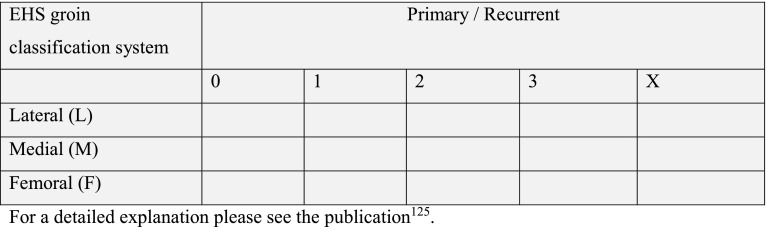

Approximately one-third of inguinal hernia (IH) patients are asymptomatic.133 Until recently, IH management involved surgical repair regardless of the presence of symptoms, the rationale being that surgery for asymptomatic IHs prevents hernia complications (incarceration or strangulation). Surgical management was recommended for any IH, including asymptomatic IHs because it was considered safe, effective, and associated with low morbidity. However, the natural history of untreated IHs—especially the incidence of complications—was unknown. Current literature suggests the possibility of surgical overtreatment of men with asymptomatic IHs. Also, the morbidity of inguinal herniorrhaphy has been re-evaluated over the last two decades and current evidence suggests that the incidence of chronic post-herniorrhaphy pain is much higher than previously realized.134

Inguinal herniorrhaphy is one of the most common operations performed by general surgeons. Therefore, considering the number of IH repairs performed worldwide annually, the consequences of overtreatment are significant. This has spurred recent studies to evaluate a watchful waiting strategy in men with asymptomatic IHs.135, 136 A critical appraisal of these studies and previous assumptions is presented.

Based on the current literature, it is not possible to determine if a watchful waiting management strategy is safe for symptomatic men with IHs. Similarly, it is impossible to determine the hernia complication rate (strangulation or bowel obstruction) in symptomatic patients. Additionally, watchful waiting raises ethical issues about observing symptomatic patients.

Key questions

KQ05.a Is a management strategy of watchful waiting safe for men with symptomatic inguinal hernias?

KQ05.b What is the risk of a hernia complication (strangulation or bowel obstruction) in this population?

KQ05.c Is a management strategy of watchful waiting safe for men with asymptomatic inguinal hernias?

KQ05.d What is the risk of a hernia complication (strangulation or bowel obstruction) in this population?

KQ05.e Are emergent inguinal herniorrhaphies associated with higher morbidity and mortality?

KQ05.f What is the crossover rate from watchful waiting to surgery?

Evidence in literature

The literature search on this topic yielded six randomized controlled trials (RCTs), two systematic reviews and three cohort-controlled studies. Two study groups produced all six RCTs.135, 136

A 2006 trial of 720 men with minimally symptomatic or asymptomatic IHs randomized subjects to either primary surgery or watchful waiting (WW).135 Primary outcomes were pain interfering with normal activities and change in physical function as measured by the physical component score of the SF-36 at 2 years. Secondary outcomes included complications, and patient-reported pain, functional status, activity levels and satisfaction. Pain interfering with daily activity occurred in 5.1% of the WW group and 2.2% in the primary surgery group at 2 years (p = 0.52). SF-36 improvement from baseline was seen in both groups. One hernia incarceration occurred within the 2-year minimum follow-up period and another occurred after 4.5 years (relative risk of 1.8 per 1000 patient years). The crossover rates were high for both groups. At 2 years, 17% crossed over from surgery to WW and 23% from WW to surgery. A WW strategy was deemed safe and acceptable since acute incarcerations rarely occurred. A secondary analysis found that those who developed symptoms had no greater risk of operative complications or recurrence than those undergoing elective hernia repairs.

A cost-effectiveness analysis was performed on the groups, calculating both costs and quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs).137 At 2 years, those in the surgery group had a $1831 higher mean cost per patient when compared with WW group subjects. The cost per additional QALY in the surgery group was $59,065. WW was judged to be a cost-effective management option for men with minimal or absent hernia symptoms.

These same groups were restudied 7 years later.2 Crossover rates, crossover reasons and time to crossover were investigated. The crossover rate from WW to surgery was 50% at 7.3 years from randomization. Median crossover time was 3.7 years in men over 65 and 8.3 years in those 65 and younger (p = 0.001). The estimated crossover rate at 10 years was 68% using Kaplan–Meier analysis. The primary reason for crossover was pain. When patients over 65 at time of original study enrollment were analyzed, the estimated 10-year crossover rate was 79.4%. This compares with a 62% 10-year crossover estimate for those 65 or younger at enrollment. In the 10-year follow-up only three men (2.4%) underwent surgery for a hernia accident. There was no mortality. The incidence of a hernia accident for the entire cohort was 0.2 per 100 person-years. These studies support the idea that men with IHs and minimal or absent symptoms should be counseled that although WW is safe, symptoms will likely progress and an operation may be needed. A follow-up cost analysis has yet to be reported.

Another 2006 study randomized 160 men over the age of 55 with asymptomatic IHs to either WW (80 patients) or surgery (80 patients).136 The primary outcome was pain at 1 year as measured by the SF-36. Cost was a secondary outcome. At 6 months, improvement—in most SF-36 dimensions—was observed in the surgery group compared with the WW group. This effect had dissipated at 12 months and there were no significant inter-group differences in visual analogue pain scores at rest or with activity. Analgesic use between groups did not differ. The only notable inter-group difference at 12 months was in a single SF-36 item indicating perceived change in health. The 1-year crossover rate from surgery to WW was 10 and 19% from WW to surgery. A single hernia incarceration occurred at 574 days. Primary surgical repair added 407.9 GBP in costs per patient (approximately $591 US).

Long-term follow-up data were published in 2011.138 At 5 years, 54% had crossed over from WW to surgery and an estimated 72% crossed over at 7.5 years. The most common crossover reason was pain. The estimated median time between randomization and crossover was 4.6 years. In 7.5 years, two patients required emergent hernia repair. The study’s authors concluded that a WW strategy is of little value since the majority of WW patients will require surgery in the near term.

Two systematic reviews have appraised primary repair versus WW for minimally symptomatic or asymptomatic IHs in men.139, 140 Both reviews included mostly observational studies and pooled data on morbidity and mortality. Morbidity and mortality after elective repair was 8 and 0.2–0.5%, respectively, versus 32 and 4–5.5% following emergent repair (a 10- to 20-fold increase in mortality). Risk factors for the observed increased morbidity and mortality include: age greater than 49 years, symptom duration, the presence of a femoral hernia, ASA class over two and nonviable bowel. Incarceration/strangulation risk factors are: symptom duration, age and hernia site (femoral). However, the reviews acknowledge that the incarceration/strangulation risk is low and that watchful waiting may be justified in selected patients.

Notably, both systematic reviews were published prior to the long-term RCTs cited above demonstrating symptom development over time in most men with minimally symptomatic or asymptomatic IHs. Symptom development (primarily pain) will prompt surgery. While it is true that incarcerations rarely occur in the WW group and are associated with defined risk factors, morbidity and mortality rates increase alarmingly when an IH strangulates.

A 2014 study reported on clinical consequences after the inception of a watchful waiting strategy.141 Regionally, a WW policy was instituted in the United Kingdom for those with asymptomatic IHs. Outcomes of approximately 1000 patients before, and 1000 patients after, the policy’s inception were compared retrospectively. The period following the policy change saw a 59% rise in the incidence of emergent hernia repair (3.6 vs 5.5%). Emergent repair was also associated with significantly more adverse events (4.7 vs 18.5%). Mortality spiked from 0.1 to 5.4%. However, this was a retrospective study and did not report on the prior histories of those requiring emergent herniorrhaphies. Therefore, conclusions should be made with caution.

Discussion, consensus and clarification of grading

The initial results of a WW strategy in men with asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic IHs were promising. Complications occurred uncommonly and WW seemed cost effective in the short term. However, a longer-term view revealed high crossover rates due to symptom development, mostly pain. Whether WW is ultimately cost effective remains to be determined.

Observational studies have shown that emergent herniorrhaphy is associated with increased morbidity and mortality. Unfortunately, it is not possible currently to accurately predict which WW patients will develop symptoms or suffer a hernia complication. This foreknowledge would of course allow more tailored management.

Because of the increased morbidity and mortality associated with emergent herniorrhaphy, the expert group advises that each patient with an asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic inguinal hernia be informed about the expected natural history of their condition, the timing, and the risks of emergency hernia surgery. Although robust support for a WW strategy and timing of surgery is not to be found in the present medical literature the expert group has upgraded its recommendation on this subject. This is because patient health-related, life style and social factors should all influence the shared decision-making process leading up to hernia management.

Chapter 6

Surgical treatment of inguinal hernias

Th. J. Aufenacker, F. Berrevoet, R. Bittner, D. C. Chen, J. Conze, F. Kockerling, J. F. Kukleta, M. Miserez, M. C. Misra, M. P. Simons, H. M. Tran, S. Tumtavitikul

General introduction

Choosing the best or most suitable groin hernia repair technique is a true challenge. The best operative technique should have the following attributes: low risk of complications (pain and recurrence), (relatively) easy to learn, fast recovery, reproducible results and cost effectiveness. The decision is also dependent upon many factors like: hernia characteristics, anesthesia type, the surgeon’s preference, training, capabilities and logistics. The patient’s wishes must be considered. There are cultural differences between surgeons, countries and regions. Emotions may play a role as well.

Accordingly, the HerniaSurge Group had some passionate discussions when developing this chapter. One single standard technique for all hernias does not exist (see also Chapter 7 on individualization).

In most situations a mesh repair is preferred. However, a minority of surgeons hold the opinion that mesh use should be avoided as much as possible. There is an ongoing discussion concerning the results of specialist centers like The Lichtenstein Hernia Clinic and The Shouldice Hospital. There are low-resource settings where mesh cannot be afforded. There are high-volume laparo-endoscopic surgeons who passionately advocate a TEP or TAPP in almost all cases. There are special mesh implants (often expensive) used by surgeons who have been successful with them for many years. How then can one reconcile these opinions and conflicts?

Although accurate and recent facts are not available, in most countries the Lichtenstein repair is probably the first choice in a majority of cases. It is a very good technique, but its outcomes may be bettered by a more difficult technique like the TEP when early postoperative recovery and the occurrence of chronic pain are considered. It is self-evident that a surgeon performing a technique and striving for optimal results should know the technique very well. Excellent training and a high caseload are the foundations of good surgery.

When comparing the best Lichtenstein outcomes with the best TEP/TAPP, it is noted that the differences are very small. It is challenging though when examining results reported in the literature because often the techniques being compared are not performed in a standardized manner by equally skilled and experienced surgeons. Therefore, this might not be true when comparing an average Lichtenstein to an average TEP/TAPP or Shouldice because of the former’s lower complexity. Furthermore, applying research results to the approach for an individual patient is problematic as well. It is often far from clear whether the results of an RCT can be generalized to one’s practice setting or patients within that setting.

In the 2009 European Guidelines, raw data were used to conclude that laparo-endoscopic and open repair were comparable in long-term follow-up of a minimum of 48 months.3, 142

When reading this chapter, we should realize that potential biases exist and these are caused by: lack of a clear chronic pain definition, variations in duration of chronic pain, age differences for the risk of chronic pain, lack of a generally agreed-upon classification system describing the type of hernias, differences in level of surgical expertise, differences in case load needed to maintain a certain technique, safety issues regarding training of the surgeons/residents in the world in difficult techniques like the TEP and TAPP, and costs of procedures, amongst others. In fact, all these factors must be considered when studying the evidence presented in the different chapters.

The chapters were researched and written by different teams, but the statements and recommendations were agreed upon by the whole HerniaSurge Group. Many lively discussions during the meetings and via email led to an internet consensus vote. There are recommendations that have been upgraded. The support for these decisions is at the end of each chapter.

Key questions

KQ06.a Which non-mesh technique is the preferred repair method for inguinal hernias?

KQ06.b Which is the preferred repair method for inguinal hernias: mesh or non-mesh?

KQ06.c Which is the preferred open mesh technique for inguinal hernias: Lichtenstein or other open flat mesh and implants via an anterior approach?

KQ06.d Which is preferred open mesh technique: Lichtenstein versus open pre-peritoneal?

KQ06.e Is TEP or TAPP the preferred laparo-endoscopic technique for inguinal hernias?

KQ06.f When considering recurrence, pain, learning curve, postoperative recovery and costs which is preferred technique for inguinal hernias: best open mesh (Lichtenstein) or a laparo-endoscopic (TEP and TAPP) technique?

KQ06.g In males with unilateral primary inguinal hernias which is the preferred repair technique, laparo-endoscopic (TEP/TAPP) or open pre-peritoneal?

KQ06.h Which is the preferred technique in bilateral inguinal hernias? Open mesh or laparo-endoscopic approach?

Key question

KQ06.a Which non-mesh technique is the preferred repair method for inguinal hernias?

Introduction

The 2009 European Guidelines opined that the Shouldice inguinal hernia repair was the best non-mesh technique.3 Since then, no studies have offered new evidence concerning a comparison between non-mesh techniques. Questions remain concerning the value of a non-mesh technique in certain cases like indirect hernias (EHS L1 and L2) in young male patients. There are questions concerning the results of Shouldice when performed in specialist centers or by specialist hernia surgeons. There are no RCTs performed in these centers. There are also regions (low-resource countries in particular) where mesh is not available and surgeons must use the best non-mesh technique. Also some patients refuse a mesh implant. Which non-mesh technique is best therefore remains an important question.

Evidence in literature

Systematic Review Cochrane 2012

A 2012 review covered all prior RCTs (until September 2011) concerning results of the Shouldice technique versus other open techniques (mesh and non-mesh).142 Eight RCTs with 2865 patients are contained, comparing mesh versus non-mesh IH repair. Most of these trials had inadequate randomization methods, did not mention dropouts and did not blind patients and surgeons to the technique used. Recurrence rate was a primary outcome in all and pain could only be analyzed in three trials. Pain definitions and measurements were not standardized. Studies were heterogeneous, with concerns that techniques were not standardized. The results show that in Shouldice versus other non-mesh (8 studies) the recurrence rate was lower in Shouldice (OR 0.62, 95% 0.45–0.85 NNH 40). Six studies reported an OR in favor of the Shouldice technique. One included study reported the most data and its weight in the analysis was 59.56%.143 The results reflect different degrees of surgeon’s familiarity with the techniques, making it impossible to eliminate the “handcraft” variable from surgical trials. Shouldice also results in less chronic pain (OR 0.3; 95% CI 0.4–1.22) and lower rates of hematoma formation (OR 0.84; 95% CI 0.63–1.13), but slightly higher infection rates (OR 1.34; 95% CI 0.7–2.54). It is more time consuming and leads to a slightly increased hospital stay (WMD 0.25; 95% CI 0.01–0.49). In their discussion, the authors conclude that the review is flawed by: the inclusion of low-quality RCTs, non-blinded outcomes assessments, lack of external validity by patient selection (only healthy patients were included), high lost-to-follow-up rates, no patient-oriented outcomes and the above-mentioned potential bias. Nevertheless, the large number of patients and consistent results do make the results useable in clinical practice. The level of the review with RCTs is downgraded to moderate. Since this systematic review was done, no new RCT comparing Shouldice with other non-mesh techniques has been published.142 The level of recommendation is strong.

Other non-mesh techniques

A 2012 RCT, in which 208 patients were randomized, described the Desarda technique compared with a Lichtenstein technique.144 Follow-up at 36 months found recurrence rates in each group of 1.9% and no significant differences in pain. As this is a new technique with some non-randomized studies showing promising results, it is worthy of mention in the guidelines. The level of the RCT is moderate and no recommendations can be formulated. The Desarda technique needs further investigation.

Large database studies

The large databases from Denmark and Sweden indicate results of non-mesh techniques, but cannot differentiate between different techniques so conclusions cannot be made concerning the quality of the Shouldice technique.145 In a 2004 questionnaire study,11, 145, 146 using results from the Danish database, chronic pain was more common after primary IH repair in young males, but there was no difference in pain when comparing Lichtenstein with non-mesh Marcy and Shouldice repairs. The databases conclude less recurrences after mesh repair, but not at the cost of more chronic pain.

Guidelines

The 2009 European Guidelines concluded that the Shouldice hernia repair technique is the best non-mesh repair method with a 1A level of evidence.3

Discussion, consensus and clarification of grading

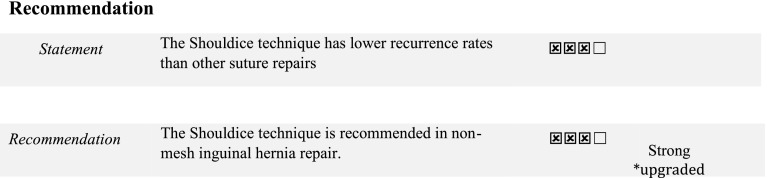

When considering the results from the systematic review, large databases and guideline conclusions, we conclude that Shouldice is superior to other non-mesh techniques especially when considering recurrence rates. In the systematic review the level of evidence was downgraded to moderate. But combining all the evidence, and after consensus by HerniaSurge, we concluded that a recommendation, upgraded to “strong” was supportable. In other words, in non-mesh repair, perform a Shouldice.

Although no studies exist on a comparison of the learning curves of the different non-mesh techniques, the HerniaSurge group agrees that the Shouldice technique is not easy to learn. In The Shouldice Hospital, surgeons are only considered qualified after 300 cases! It is well known that in many (mainly low resource) countries a (modified) Bassini is still performed.

Another matter is a discussion concerning the results of only high ligation and sac resection versus Shouldice in young adults with L1 and L2 IH. HerniaSurge is of the opinion that this issue needs further research. We are unable to formulate a statement on it at this time.

KQ06.b Which is the preferred repair method for inguinal hernias: mesh or non-mesh?

M. P. Simons, J. Conze and M. Miserez

Introduction

The 2009 European Guidelines concluded that all male adults over the age of 30 with a symptomatic IH should be operated on using a mesh-based technique (grade A).3 In most countries, the use of mesh has been accepted by the majority of surgeons as the best approach to decrease risk of recurrence. There are concerns about mesh causing more chronic pain. Other reasons not to use mesh include: higher cost or non-availability of meshes in low-resource settings, lack of surgical expertise with mesh, and patient refusal of a mesh repair. It remains to be seen whether a mesh-based technique is indicated in all cases (see also Chapter 7 on individualization).

Evidence in literature

Systematic Review Cochrane 2012

A 2012 systematic review covered all prior RCTs (until September 2011) concerning results of Shouldice versus other open techniques.142 The review contains 6 RCTs including 1565 patients and compared Shouldice versus open mesh (Lichtenstein in all studies except one with plug and patch) for IH repair. The overall RCT quality is low. Recurrence rates were the primary outcome. Pain definitions and measurements were not standardized. Studies were heterogeneous. There are concerns that techniques were not standardized and no classification was applied.

The results show, that in Shouldice versus mesh Lichtenstein, recurrence rate were higher in Shouldice (5 studies) (OR 3.65, 95% 1.79–7.47, NNH 36). Although not the primary endpoint in most trials, there were no significant differences between Shouldice and Lichtenstein for postoperative stay, chronic pain, seroma/hematoma and wound infection, but operative time was shorter for mesh repair (WMD 9.64 min; 95% CI 6.96–12.32).

The authors concluded that the review is flawed by low-quality RCTs, non-blinded outcomes assessment, external validity concerns due to patient selection (generally healthy patients were studied), high lost-to-follow-up rates, lack of patient-oriented outcomes and the above-mentioned potential bias concerning surgical technique. Nevertheless, the large number of patients and consistent results do make the results useful.

Other RCTs since the systematic review

Since September 2011, three RCTs have been published describing a non-mesh versus mesh repair but they were excluded because they either did not include Shouldice repairs,147–149 Lichtenstein repairs,147, 150 or had a very short follow-up.148–150

One 2012 RCT, in which 208 patients were randomized, compared the Desarda technique with a Lichtenstein technique. At 36-month follow-up, the recurrence rate in each group was 1.9% and no significant differences in pain were found. The Desarda technique is new and the subject of some non-randomized studies showing promising results, but the technique needs further investigation. The 2012 RCT is graded as moderate. No recommendations about its use can be made at this point.

Large database studies

Two publications from the Danish Hernia Database describe recurrence after 96 months following open non-mesh versus Lichtenstein. The recurrence rate after open non-mesh repair was 8 versus 3% for Lichtenstein.11, 151, 152 These studies are flawed because the Shouldice group consisted of only 13% of all suture repairs and that reoperation rather than recurrence rates were used. However, they do offer insights though about outcomes in a general population being treated by general surgeons (see Chapter 25 concerning the value of database studies). A 2004 questionnaire study of the Danish database found that chronic pain occurred more commonly after primary IH repair in young males. But, no differences in pain occurred when comparing Lichtenstein with Marcy and Shouldice non-mesh repair techniques. The database studies also found fewer recurrences after mesh repair.

Guidelines

The European Guidelines concluded that all male adults over the age of 30 years with a symptomatic IH should be operated on using a mesh technique (grade A).3 They also recommend that a mesh technique be used for inguinal hernia correction in young men (18–30 years of age and irrespective of the type of inguinal hernia). The conclusion was based on a lack of evidence that the recurrence risk after L1–2 IH in younger men is acceptably lower than in men above 30. This question is not being researched probably due to the fact that almost all male patients are now treated with mesh techniques.

Cohort studies

There is lower level evidence that the Shouldice technique has a recurrence rate of less than 2% especially when performed in high-volume expert settings like the Shouldice Hospital.153 These data come primarily from expert centers. Often the studies suffer from inadequate follow-up and there is patient selection bias in some. This gives rise to a dispute between open non-mesh surgeons and surgeons advocating mesh repair on the true value of the Shouldice repair. Resolution is unlikely unless an RCT is performed with adequate methods truly comparing techniques by surgeons qualified and experienced in both approaches. This might be possible using large databases provided identification of Shouldice technique is done. It is clear from all high-level studies though that in general practice, mesh is superior to non-mesh especially when measuring recurrence rate. It is absolutely recommended that studies be performed into the value of Shouldice versus mesh in young male patients with lateral (L1) inguinal hernia. One important study with long-term follow-up after Shouldice indicated that hernia type (indirect versus direct) was not an independent risk factor.154 Recurrence after Shouldice after 2 and 5 years was, respectively, 4.3 and 6.7%. Out of 21 recurrences 20 were direct. Out of 20 recurrences 7 were after an indirect hernia with an enlarged internal ring, 6 after indirect with a weakened posterior wall and 7 after a direct hernia (n.s.). There are cohort studies concerning Shouldice that indicate that classification matters and the risk of recurrence is higher after a direct non-mesh repair.80 An analysis of the location of the hernial gap revealed 83 lateral hernias (48.5%) and 88 medial hernias (medial or combined, 51.5%). The recurrence rate was 13.6% for medial or combined hernias and 8.4% for pure lateral hernias. This was not significant. Furthermore, it is unknown whether a high ligation and sac resection (herniotomy) has comparable results to Shouldice in these patient groups.

Discussion, consensus and grading clarification

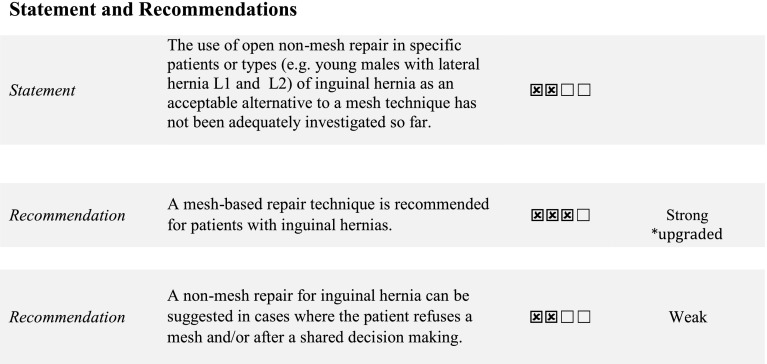

Compared to non-mesh techniques mesh-based techniques have a lower recurrence rate and an equal risk of postoperative pain. Despite the mentioned limitations of the 2012 review, the large number of patients and consistent results make available evidence reliable and useable in practice. There is no conclusive evidence that mesh causes more chronic pain. It remains to be seen whether a mesh-based technique is indicated in all cases such as small lateral hernias (EHS L1 and L2) (see Chapter 7 on individualization).

It is unclear whether it is appropriate to compare the results of the Shouldice technique, usually performed by highly trained surgeons and/or in specialized centers, to the open mesh repair techniques which tend to be performed by generalists. Specialized centers have not published their results in a reliable manner. Many cohort studies contain bias and thus lack external validity. It is necessary to improve knowledge concerning this question concerning the value of non-mesh techniques especially for long-term recurrence rate and chronic pain. Although the level of evidence seems only moderate, by consensus in HerniaSurge the recommendation to use a mesh-based technique in inguinal hernia repair is upgraded to “strong”.

KQ06.c Which is the preferred mesh for open inguinal hernia repair: anterior flat mesh, self-gripping mesh or three-dimensional implants (plug-and-patch and bilayer) via an anterior approach?

M. Miserez, J. Conze and M. Simons

Introduction

The Lichtenstein technique with the onlay placement of a flat mesh is the criterion standard in open IH repair.155 Many alternatives to the original Lichtenstein technique have been described. The plug-and-patch (or mesh-plug) technique was the first,156 followed by the Trabucco technique.157 and the Prolene® Hernia System (PHS).158

In the Trabucco technique, a polypropylene plug is combined with a semi-rigid flat pre-shaped polypropylene mesh. Neither implant is fixed. The spermatic cord is placed subcutaneously. At the time of the first EHS guidelines on the treatment of IH in adults, no long-term comparative follow-up data were available on any of these techniques,3 but this changed at the time of the update with level 1 studies of the 2009 EHS guidelines. In addition, self-gripping meshes have been designed in an attempt to reduce or abandon the need for traumatic mesh fixation in Lichtenstein repair and decrease the risk for acute and chronic pain.

Evidence in literature

Plug-and-patch

The recent 2014 EHS guidelines update,4 with level 1 studies, included data on the comparison between plug-and-patch versus Lichtenstein from two meta-analyses of seven RCTs.159, 160 These showed shorter operative times for the plug-and-patch (by 5–10 min), but otherwise comparable outcomes in the short- and long-term (follow-up ranging from 0.5 to 73 months).

Long-term follow-up data from two of the RCTs were published in 2014. The first study used a questionnaire to assess recurrence rates and chronic pain after a median follow-up of 7.6 years (n = 180, 81% follow-up rate).161 Recurrence rates for Lichtenstein and plug-and-patch were 5.6 and 9.9%, respectively (p = 0.770). Moderate or severe pain was reported in 5.6 and 5.5%, respectively (p = 0.785). The second study—which also included recurrent hernias—evaluated patients by means of physical examination after a 6.5-year median follow-up and had similar findings (n = 528, 76% follow-up rate).162 Recurrence rates for Lichtenstein and plug-and-patch were 8.1 and 7.8%, respectively (OR 0.92 n.s.) and chronic persistent pain (VAS > 3). More reoperations occurred in the Lichtenstein group (OR 0.43, p = 0.016).

Prolene ® Hernia System (PHS)

At the time of the EHS update, two meta-analyses of six RCTs were published comparing PHS and Lichtenstein (follow-up ranging from 12 to 48 months).159, 163 In addition, one long-term follow-up study (5-year follow-up) was available.164 No differences in recurrence or chronic pain were found. The data on operative times and perioperative complications were contradictory in the meta-analyses, although no differences were seen for postoperative wound hematoma formation or infection in either.

A 2014 long-term outcome study (mean follow-up of 7.6 years) also include a PHS arm and these data are reported below,161 confirming earlier results. The recurrence rates for Lichtenstein and PHS were 5.6 and 3.3%, respectively (p = 0.770). The incidence of chronic pain (moderate or severe) was 5.6 and 6.7%, respectively (p = 0.785).

A large-pore version of the PHS, the Ultrapro® Hernia System (UHS), was launched recently. One RCT compares Lichtenstein and the UHS.165 Another RCT compared the plug-and-patch technique with a 4D Dome® device in 95 patients.166 The “dome device” consists of a largely resorbable dome-shaped plug (90% poly-l-lactic acid and 10% polypropylene) associated with a flat lightweight polypropylene mesh. Because of poor methodological quality (according to SIGN criteria), neither paper is further discussed here.

Trabucco

One RCT compared the Lichtenstein with the Trabucco technique in 108 patients under local anesthesia.167 The Trabucco technique was an average of 10 min faster vs. Lichtenstein (p = 0.04). There were no differences in postoperative pain (primary outcome) or groin discomfort at 6 months. At an average follow-up of 8 years (only telephone follow-up after 1 year), there were no recurrent hernias.

Self-gripping mesh

The first study on the use of the self-gripping Parietene Progrip© mesh (large-pore polypropylene with resorbable polylactic acid micro-grips) found less pain on the first postoperative day when compared with the use of another large-pore non-gripping polypropylene mesh.168 Subsequently, four other RCTs comparing self-fixating large-pore mesh vs suture fixation in Lichtenstein have been published up to 2013.169–172 These studies have been evaluated in five different meta-analyses, all published in 2013 and 2014 in different journals.173–177 All confirmed no difference in acute or chronic pain and recurrence rates.

Three additional RCTs were published in 2014,178–180 and another two were published with long-term data from an RCT published earlier.181, 182 All confirmed comparable recurrence rates and acute and chronic pain incidence in both groups. The self-fixation mesh is likely to be more expensive than standard fixation, but the operative time was shorter in the Progrip© group (by a range of 1–12 min).

Since only data on medium-term follow-up are available (range 6–24 months), we advise the authors of the previously mentioned trial data to follow-up their patients at 3–5 years and publish their updated results on chronic pain and recurrence rates.

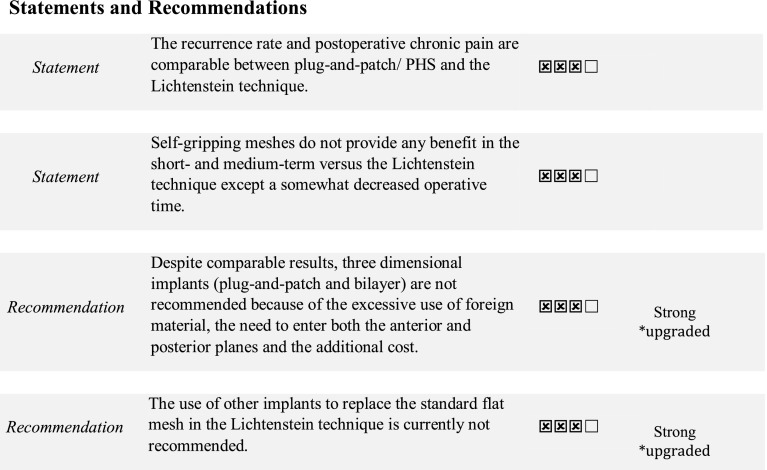

Discussion, consensus and grading clarification

Plug-and-patch and PHS are acceptable treatments for primary IHs, but have no benefit vs. the Lichtenstein technique, except a somewhat shorter operative time for the plug-and-patch technique. However, both the anterior and posterior compartment are entered and scarred, making a subsequent repair for recurrence more difficult. Also, the amount of foreign material is higher than for a simple flat mesh. And—in the case of a combined hernia—the placement strategy for the device or plug is not standardized. The additional cost of the device needs to be taken into account as does the small chance of mesh migration/erosion with the use of plugs. Therefore, the Lichtenstein technique with a flat mesh is considered to be superior. See also Chapter 10 on mesh in which the problems of mesh-plug erosion and migration are described.

Self-gripping mesh is an acceptable form of treatment for primary IHs, although only medium-term data are available and no specific information on the outcome in larger (direct) hernias. It has no benefits over the Lichtenstein technique other than a somewhat shorter operative time. Here also, the device’s additional cost must be considered.

For these reasons, the recommendations to use the Lichtenstein technique with a standard flat mesh vs the use of self-gripping mesh or three-dimensional implants are upgraded to strong by the HerniaSurge Group.

KQ06.d Which is the preferred open mesh technique for inguinal hernias: Lichtenstein or any open pre-peritoneal technique?

F. Berrevoet, Th. Aufenacker and S. Tumtavitikul

Introduction

Open pre-peritoneal mesh techniques have gained more attention in the repair of IHs during the last two decades as a result of technical and commercial considerations. Surgeons should understand that “open pre-peritoneal techniques” as originally described by Nyhus,183 include several different approaches including the trans-inguinal pre-peritoneal repair described by Pélissier (TIPP),184 the posterior Kugel technique,185 transrectus pre-peritoneal approach (TREPP),186 Onstep approach,187 Ugahary technique,188 Wantz technique,189 and Rives’ technique,190 for anterior pre-peritoneal repair. Note that TIPP, Onstep, and Rives’ techniques approach the pre-peritoneal space through an anterior dissection opening the inguinal canal. Kugel, TREPP, Ugahary and Wantz use a posterior approach to open repair without entering the inguinal canal anteriorly.

Onstep is comparable with the PHS/UHS system, although there is only one mesh layer reinforcing the medial side pre-peritoneally, and the lateral side as in the Lichtenstein technique.

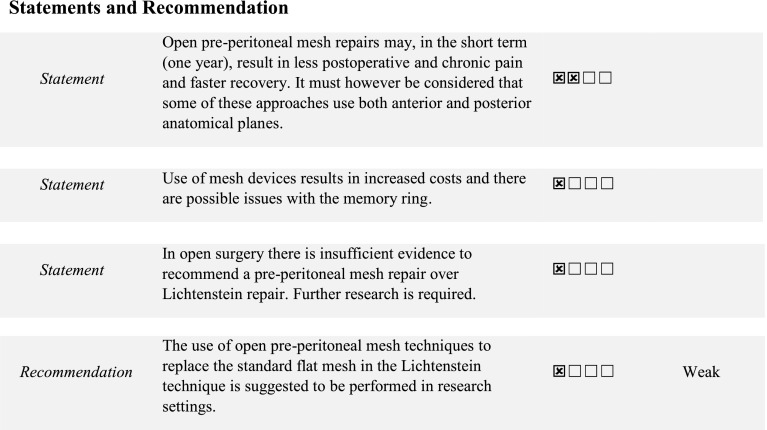

There are no data comparing the open pre-peritoneal techniques with each other, so no recommendation can be made about the preferred open pre-peritoneal technique. However, we are able to make the following statements based on limited data about pre-peritoneal techniques. The use of these techniques is suggested to be performed in research conditions.

Evidence in literature

Two meta-analyses, one systematic review and three RCTs were identified out of 596 publications as suitable for inclusion and analysis below.

Cochrane Systematic Review 2009

A 2009 Cochrane Systematic Review included three eligible trials with 569 patients.191 Due to methodological limitations in the three trials considerable variations were found in acute pain (risk range 38.67–96.51%) and chronic pain (risk range 7.83–40.47%) across control groups. Two trials involving 322 patients found less chronic pain after pre-peritoneal repair (relative risk 0.18). These same two trials also found less acute pain (relative risk 0.17). One study of 247 patients found more chronic pain after pre-peritoneal repair (relative risk 1.17). This study reported that acute pain was nearly omnipresent and thus comparable in both intervention arms (relative risk 0.997, NNT 333). Early and late hernia recurrence rates were similar across the studies. Conflicting results were reported for other early outcomes like infection and hematoma formation.

Both pre-peritoneal and Lichtenstein repairs were seen as reasonable approaches since they resulted in similarly low hernia recurrence rates. There is some evidence that pre-peritoneal repairs cause less, or at least comparable, acute and chronic pain when compared with the Lichtenstein procedure. However, the Systematic Review authors emphasized the need for homogeneous high-quality randomized trials comparing elective pre-peritoneal IH repair techniques with the Lichtenstein repair to assess chronic pain incidence.

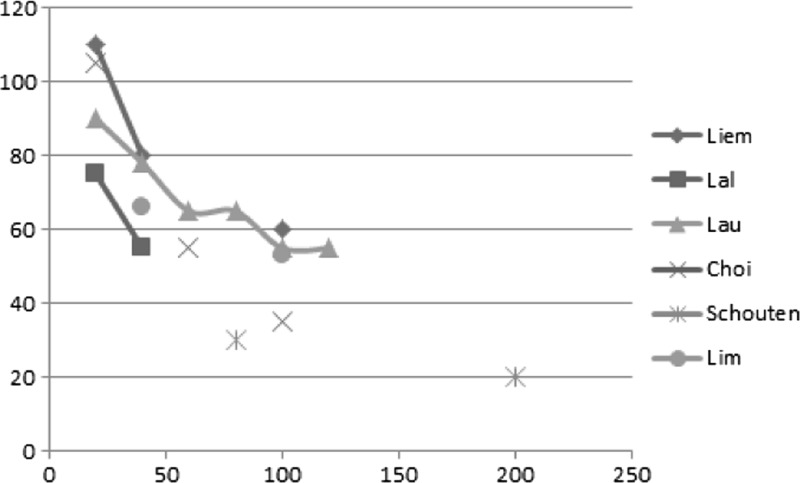

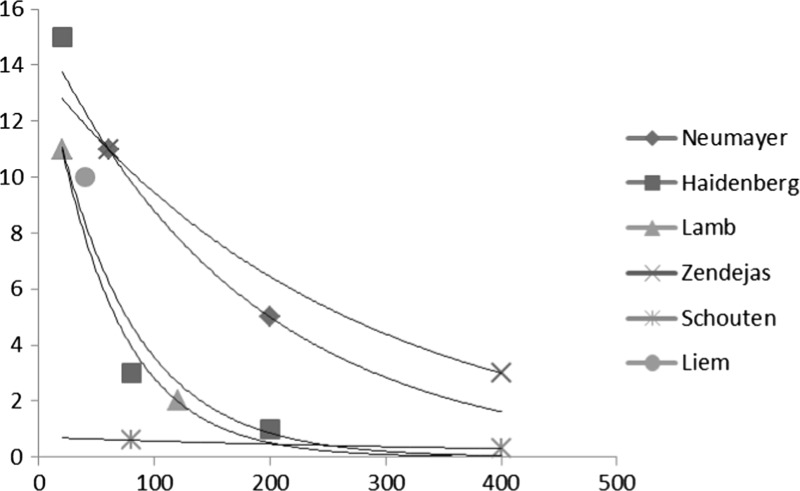

Meta-analysis 2013