Abstract

Following endocytosis and entry into the endosomal network, integral membrane proteins undergo sorting for lysosomal degradation or are alternatively retrieved and recycled back to the cell surface. Here we describe the discovery of an ancient and conserved multi-protein complex which orchestrates cargo retrieval and recycling and importantly, is biochemically and functionally distinct to the established retromer pathway. Composed of a heterotrimer of DSCR3, C16orf62 and VPS29, and bearing striking similarity with retromer, we have called this complex ‘retriever’. We establish that retriever associates with the cargo adaptor sorting nexin 17 (SNX17) and couples to the CCC and WASH complexes to prevent lysosomal degradation and promote cell surface recycling of α5β1-integrin. Through quantitative proteomic analysis we identify over 120 cell surface proteins, including numerous integrins, signalling receptors and solute transporters, which require SNX17-retriever to maintain their surface levels. Our identification of retriever establishes a major new endosomal retrieval and recycling pathway.

Central to the biogenesis and homeostasis of all eukaryotic organelles is the controlled delivery and removal of integral membrane proteins. A major nexus for determining the correct and efficient transport of integral membrane proteins is the endosomal network1. Here the fate of integral membrane proteins and their associated proteins and lipids (together termed ‘cargos’) is determined. Either cargo are trafficked to the lysosome for degradation or recycled to organelles that include the plasma membrane, the trans-Golgi network, lysosome-related organelles, and the autophagosome2. Consistent with the fundamental role of the endosomal network in establishing and maintaining organelle function, perturbations in the network are increasingly being associated with human disease3.

Sorting of cargo for lysosomal degradation is mediated by the ESCRT complexes, a series of multi-protein assemblies that co-ordinate cargo recognition with the formation of cargo-enriched intraluminal vesicles that are ultimately delivered to the lysosome4. Conversely, retromer is a major controller of retrieving cargo from a lysosomal degradative fate and promoting subsequent recycling back to the cell surface5. Formed by the stable association of VPS26, VPS35 and VPS296, this ancient and evolutionary conserved complex recognises sorting signals within the intracellular cytosolic domain of cargo proteins either directly or indirectly via the cargo adaptor sorting nexin-27 (SNX27)7–19. Retromer coordinates sequence-dependent cargo capture with the recruitment of the pentameric WASH complex, an activator of Arp2/3-dependent actin polymerisation20–24. This drives the formation of endosomal actin-enriched sub-domains that corral captured cargo and couples this with biogenesis of transport carriers to allow for cargo recycling25.

Numerous cargo, including α5β1 integrin, do not depend on retromer for their retrieval from lysosomal degradation and recycling back to the cell surface26.How these cargo are retrieved in a retromer-independent manner remains unclear. Given that mechanistic analysis of endosomal cargo retrieval and recycling is allowing a greater understanding of the patho-etiology of human diseases27–31, we have sought to identify and characterise evolutionary conserved retromer-independent cargo sorting machinery(s).

Here we report the discovery of an ancient multi-protein complex that is essential for retromer-independent retrieval and recycling of cargo which include α5β1 integrin. This complex shares similarities with retromer and assembles as a heterotrimer consisting of DSCR3, C16orf62 and VPS29. We have termed this complex ‘retriever’. We establish that retriever associates with the cargo-adaptor sorting nexin 17 (SNX17) as well as a protein complex termed the CCC complex that is composed of CCDC22, CCDC93 and various COMMD proteins39. The CCC complex in turn associates with the WASH complex39 and both are required to orchestrate the SNX17-retriever dependent retrieval and recycling of α5β1 integrin. Through unbiased quantitative proteomic analysis we identify multiple integral membrane proteins with roles in cell migration and adhesion, signalling, solute and nutrient transport which require SNX17-retriever for maintenance of their cell surface levels. Furthermore, we also establish that the SNX17-retriever pathway is hijacked during cellular infection by human papillomavirus. Our discovery of retriever establishes an ancient and conserved retromer-independent cargo sorting pathway that regulates the endosomal sorting of a multitude of integral cell surface proteins.

RESULTS

Proteomic identification of retromer-independent endosomal sorting machinery

Recently we, and others, have established that the endosomal retrieval and recycling of internalised β1-integrin is mediated through the evolutionary conserved cargo adaptor SNX1726, 32. SNX17 contains a 4.1/ezrin/radixin/Moesin (FERM)-like domain which binds to the NPxY/NxxY (where x donates any amino acid) sorting motif present within the intracellular cytosolic domain of hundreds of integral membrane proteins, including the cytosolic domain of β1-integrin and LDL receptor family members26, 32–37. Importantly, SNX17-mediated recycling of β1-integrin occurs independently of retromer26, suggesting that it is linked to an alternative recycling pathway.

To identify components of this unknown pathway we turned to unbiased quantitative proteomics. We have previously used GFP-nanotrap immuno-capture coupled with SILAC (stable isotope labelling with amino acids in culture)-based quantitative proteomics to provide molecular insight into the assembly of endosomal sorting complexes18, 27, 38. To establish this methodology for SNX17, we first validated that GFP-tagging of SNX17 did not adversely affect its function. GFP-SNX17 (a fusion with a ten amino acid linker between the GFP and the amino terminus of SNX17) and SNX17-GFP (a fusion with a seven amino acid linker between the carboxy-terminus of SNX17 and GFP) both localised to early endosomes and bound to the NPxY motif-containing SNX17 cargo, LRP135, 36 (Figure 1A-C). In rescues of a SNX17 loss-of-function phenotype26, 32, GFP-SNX17 fully rescued the α5β1-integrin sorting while SNX17-GFP failed to rescue (Figure 1D and supplementary figure 1A). Since localisation and cargo binding of SNX17-GFP was unperturbed, we hypothesized that the carboxy-terminal GFP tag uncouples the SNX17 cargo adaptor from downstream endosomal sorting machineries. We therefore designed a comparative proteomic analysis in human RPE-1 cells, transduced to express at equivalent levels GFP-SNX17 or SNX17-GFP (Figure 1E-F). This unbiased and quantitative approach identified a sub-set of proteins that associated with GFP-SNX17 but failed to bind to SNX17-GFP (Figure 1G and Table S1). Among these proteins were CCDC22, CCDC93, and seven of the ten human COMMDs. These form the CCC complex39, shown to be required for the endosomal recycling of certain cargos, including copper transporters39, Notch family members39, 40 and LDLR41. Additional proteins identified from our proteomics included the CCC complex associated C16orf6239, DSCR3 and the retromer subunit VPS29. Associations (with the exception of VPS29) were validated by Western analysis of immunoprecipiates from exogenously expressed (GFP-SNX17 and SNX17-GFP) and endogenous SNX17 (Figure 1H-I). Importantly, C16orf62, DSCR3, CCDC22 and CCDC93 did not associate with retromer or its adaptor SNX27, leading us to hypothesise that they form a retromer-independent protein sorting machine(s) (Figure 1H).

Figure 1. Comparative GFP-SNX17 and SNX17-GFP proteomics identifies the retromer-independent sorting machinery.

(A, B) GFP-SNX17 and SNX17-GFP localise to early endosomes in RPE-1 transduced cells. Representative field of view from n=3. EEA1 is an early endosomal marker, LAMP1 is a late endosome/lysosomal marker. (C) GFP-SNX17 and SNX17-GFP were expressed in HEK 293 cells and GFP traps were performed. Western blot analysis verified that these constructs bind LRP1, an established SNX17 cargo. Representative blot of n=3. (D) SNX17 was suppressed in HeLa cells by siRNA before re-expression of GFP or siRNA resistant versions of GFP-SNX17 or SNX17-GFP. Representative images from n=3. See supplementary figure 1 for zoomed out images. (E) Schematic of SILAC proteomics. (F) GFP-SNX17 and SNX17-GFP transduced cells were lysed and the expression of SNX17 was analysed. GFP-SNX17 or SNX17-GFP band intensities were measured using Odyssey software and normalised to loading control and compared to endogenous SNX17 (set to 1). Differences between GFP-SNX17 and SNX17-GFP levels were tested with t-test. Quantification from n=3. Ns = non-significant. (G) Filtered proteomic data plotted as logScore versus log(SNX17-GFP enrichment/GFP-SNX17 enrichment). Each circle represents a protein of the SNX17 interactome. Proteins with a large negative log(SNX17-GFP enrichment/GFP-SNX17 enrichment) are specifically lost in the SNX17-GFP condition. The protein highlighted in red is a member of the retromer complex (VPS29), orange circles indicate proteins of the CCC complex, the purple circle represents a CCC complex associated protein (C16orf62) and a blue circle represents a protein of unknown function (DSCR3). (H) The proteomic data was validated by GFP traps and Western analysis from HEK 293 cells transiently transfected with GFP, GFP-SNX17, SNX17-GFP, GFP-VPS35 or GFP-SNX27. Representative blot of n=3. (I) Endogenous SNX17 was immunoprecipitated and the recovered material was immunoblotted for the indicated proteins. Representative blot of n=3

Depletion of the CCC complex, C16orf62, DSCR3 and VPS29 phenocopies α5β1-integrin missorting observed upon suppression of SNX17

To investigate whether DSCR3, C16orf62, VPS29 and CCC complex components CCDC22 and CCDC93 have a phenotypic relationship with SNX17 in the context of α5β1-integrin endosomal sorting we performed a targeted siRNA screen. Like the suppression of SNX1726, 32, siRNA suppression of CCDC22, CCDC93, C16orf62 and DSCR3 led to a pronounced loss of cell surface α5β1-integrin and enrichment in LAMP1 positive late endosomes/lysosomes due to lysosomal missorting instead of recycling (Figure 2A). This phenotype was also observed in a CRISPR/Cas9 VPS29 KO HeLa line and could be rescued by re-expression of VPS29 (Figure 2B). Furthermore, biochemical analysis of the stability of α5β1-integrin showed that in VPS29 KO HeLa cells α5β1-integrin had an increased rate of degradation. This phenotype was rescued by re-expression of VPS29 (Supplementary Figure 1B-D). In contrast, VPS35 KO cells (targeting the retromer complex) did not show this phenotype (Supplementary Figure 1B-D). VPS29 is therefore involved in the retrieval and recycling of α5β1 integrin in a manner distinct to its role in retromer. Suppression of CCDC22, CCDC93 and C16orf62 also phenocopied a loss of SNX17 as defined by decreased recycling of internalized β1-integrin, reduced cell surface level of α5β1-integrin and enhanced rate of lysosomal-mediated integrin degradation (Figure 2C-F). These data establish a clear functional link between these proteins and SNX17-mediated sorting of α5β1-integrin.

Figure 2. Suppression of SNX17, CCDC22, CCDC93, C16orf62 and DSCR3 or deletion of VPS29 but not VPS35 leads to miss-sorting of α5β1 integrin.

(A) HeLa cells were transfected with siRNA targeting the indicated proteins and were fixed 72 hours post transfection. Cells were stained for α5 integrin and the lysosomal marker LAMP1. Representative fields of view from n=3. Quantification of the Pearson’s coefficient, colocalisation coefficient and significance were calculated across three independent knockdown experiments. Coefficients were compared to scramble control values by t-test. *** p<0.001, ** p<0.01. (B) VPS29 knock out results in lysosomal missorting α5β1 integrin. Parental, VPS29 KO and VPS29 KO rescue (where VPS29 was re-expressed in VPS29 KO) HeLa cells were fixed and stained for α5 integrin and the lysosomal marker LAMP1. Pearson’s and colocalization coefficients were calculated from 3 independent experiments. Coefficients were compared to parental HeLa values by t-test. *** p<0.001, ns = non-significant. (C) HeLa cells transfected with the indicated siRNA were incubated with a monoclonal antibody against β1 integrin for 30 min at 37°C. Surface bound antibody was acid stripped and followed by further incubation at 37°C for the indicated time before fixation. (D) HeLa cells were transfected with siRNA targeting the indicated proteins. Cells were biotinylated with a membrane-impermeable biotin conjugate. Cells were lysed and biotinylated proteins isolated with streptavidin sepharose followed by Western blotting. Quantification from n=3. Band intensities of cell surface proteins were measured and calculated as a % of scrambled control band intensity. Knock-down conditions were compared to scrambled control using t-test. *** p<0.001, ** p<0.01, * p<0.05. Error bars represent s.d. Quantification of band intensities was done using Odyssey software. (E) HeLa cells were knocked-down with indicated siRNA. Cells were incubated with the lysosomal inhibitor leupeptin prior to lysis. Protein levels were then analysed by Western blotting. Representative blots taken from one of three independent experiments (F) HeLa cells transfected with the indicated siRNAs were treated with the ribosomal inhibitor cycloheximide for 3, 6 and 9 hours followed by Western blot based quantification of total α5β1 integrin levels. Quantification from n=3. Quantification of Western blot was achieved on Odyssey software. Protein amounts are represented as a % of protein present at 0 hours per condition. % of protein in knock-down conditions was compared to protein % in scramble control per time point using t-test. *** p<0.001, ** p<0.01, * p<0.05.

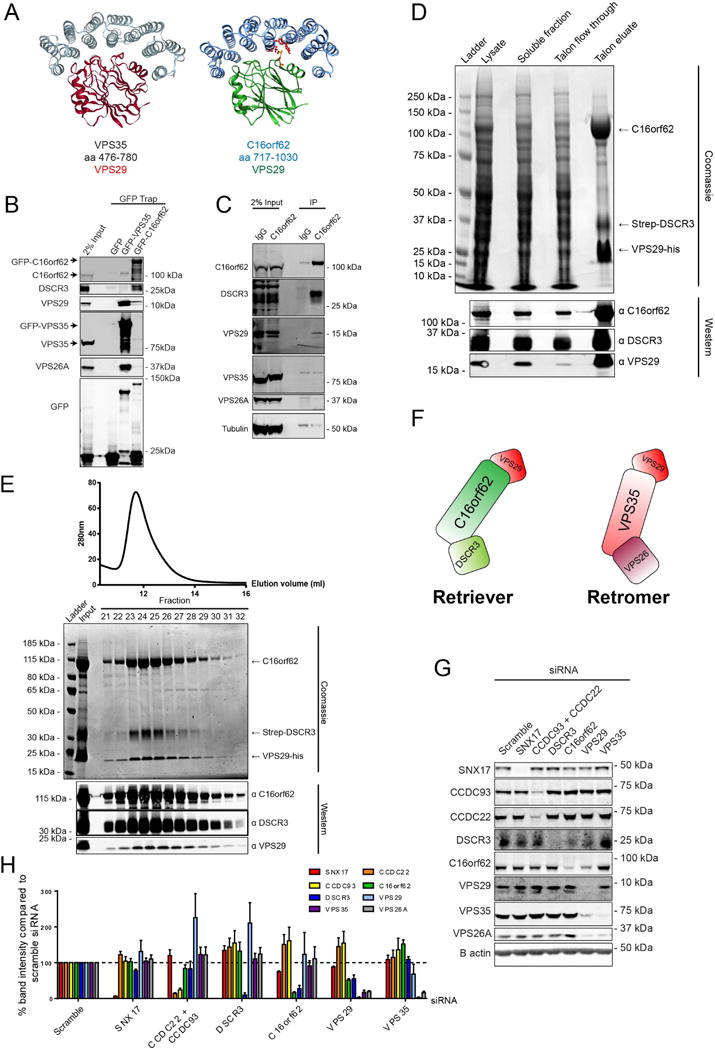

DSCR3, C16orf62 and VPS29 form a heterotrimer with similarity to retromer

Our proteomic data and functional analysis is consistent with C16orf62, DSCR3 and VPS29 being required for retromer-independent endosomal sorting of SNX17 cargo. We next sought to establish the relationship between these proteins. Using HHPred, we noted that the carboxy-terminal region (residues 717-1030) of human C16orf62 is predicted, with 99.8% probability, to contain a HEAT-repeat protein fold similar to that observed in VPS3542. Indeed, using the published structure of the carboxy-terminus of VPS3542, we were able, with minor deletions and insertions, to model the carboxy-terminus of C16orf62 (Figure 3A). The structural similarity between C16orf62 and VPS35, taken with the functional and physical link with the retromer subunit VPS29 and DSCR3, which is considered to be a paralogue of VPS2643, led us to speculate that C16orf62 may be part of an alternative retromer-like assembly along with DSCR3 and VPS29. Immuno-isolation of GFP tagged VPS35 or C16orf62 established that DSCR3 associated with C16orf62 but not with retromer and that VPS29 associated with both retromer and C16orf62 (Figure 3B). Immunoprecipitation of endogenous C16orf62 confirmed the specific nature of the association with DSCR3 and VPS29 (Figure 3C).

Figure 3. C16orf62, DSCR3 and VPS29 form a retromer-like heterotrimer.

(A) A homology model of C16orf62, residues 717-1030, was constructed, using the published VPS35 structure as a template. For modelling details see (van Weering et al., 2012). (B) C16orf62 interacts with DSCR3 and VPS29 but not the other retromer subunits VPS35 and VPS26A. GFP traps of GFP-VPS35 or GFP-C16orf62 followed by Western analysis in HEK 293 cells. Representative blot of n=3. (C) Endogenous C16orf62 interacts with endogenous VPS29 and DSCR3. Endogenous C16orf62 immuno-precipitations in HEK 293 cells. Representative blot from n=3. (D) C16orf62, Strep-DSCR3 and VPS29-his form a complex. C16orf62, Strep-DSCR3 and VPS29-his were expressed in Sf21 insect cells using the MultiBac system (see supplementary figure 2 for details). Following lysis by sonication, cleared insect lysate was added to a column filled with Talon resin. Bound proteins were eluted with imidazole. Samples from each step of the purification were collected and analysed by SDS-PAGE followed by either Coomassie staining or Western analysis. For Coomassie staining, the lysate, soluble fraction and talon flow through lanes represent 0.05% of total protein input in the Talon column. Eluate represents 1% of eluted protein. For Western analysis, a smaller amount of protein was loaded; 0.025% from the same lysate, soluble and flow through samples were loaded and 0.5% of the total talon eluate. Representative images from n=3. (E) C16orf62, Strep-DSCR3 and VPS29-his co-elute following size exclusion chromatography. Following the VPS29-his purification shown in D, the eluate was concentrated and injected into a superdex200 size exclusion column. Fractions were collected and then analysed by SDS-PAGE followed by either Coomassie staining or Western blotting. (F) Schematic model of retriever and retromer minimal protein assemblies (G and H) Retriever is distinct to the CCC complex and retromer. HeLa cells were transfected with siRNA targeting the indicated proteins and Western blot analysis was subsequently performed. Representative blot of n=3. Band intensities were measured using the Odyssey software and normalised to their respective loading control (β-actin) before calculating the percentage protein compared to the non-targeting (scramble) siRNA control. Bars represent the average of three independent experiments. Error bars represent S.E.M.

To establish whether DSCR3, C16orf62 and VPS29 form a heterotrimeric complex we turned to MultiBac technology for the expression and isolation of multi-protein assemblies from insect cells44. Through design of a single bacmid for the co-expression of amino–terminal Strep tagged DSCR3, untagged C16orf62 and VPS29 tagged with 6xHis at its carboxy-terminus (see Supplementary Figure 2A for schematic of the MultiBac system) we observed the expression of all three proteins in a crude insect cell lysate (Figure 3D). On application of the cell lysate to Talon resin (to affinity capture the VPS29-6xHis) followed by rounds of washes and a bulk elution of bound proteins, we observed, by Coomassie staining, the co-elution of C16orf62 and Strep-DSCR3 together with VPS29-6xHis (Figure 3D). We confirmed the identity of each protein by Western analysis (Figure 3D). Application of the concentrated eluate from the Talon resin to a size-exclusion column established that Strep-DSCR3, C16orf62 and VPS29-6xHis co-eluted as a complex of an apparent size of 325 kDa (Figure 3E and Supplementary Figure 2B-C). As the predicted molecular weight of the C16orf62, DSCR3 and VPS29 heterotrimeric complex is 171 kDa this suggests that the heterotrimer assembly may form a dimeric complex under these conditions. This is reminiscent of retromer, which also displays an ability to form a dimeric complex that has been proposed to aid retromer coat assembly14, 45. Overall, these data establish that DSCR3, C16orf62 and VPS29 assemble into a heterotrimeric complex. We propose to call this new complex ‘retriever’ (Figure 3F).

As an additional level of validation, we analysed the effects of selected protein suppression on the stability of retriever (Figure 3G-H). RNAi-mediated silencing of SNX17 had no effect on the levels of retriever, retromer or the CCC complex. Similarly, suppression of the CCC complex did not result in reduction of either retriever or retromer, suggesting that the retriever assembly is distinct from the CCC complex. Suppression of C16orf62 led to a reduction in DSCR3 levels but had no effect on retromer levels. VPS35 suppression led to reduced protein expression of the retromer partner VPS26A and a 32% reduction in the levels of VPS29 while DSCR3 and C16orf62 expression were unaffected. While VPS29 suppression resulted in a reduction of both retriever and retromer, consistent with its shared presence in these complexes, the relative levels of reduction were distinct: retromer was consistently more reduced (only 17% of VPS35 and 19% of VPS26 remained) than retriever (51% of C16orf62 and 55% of DSCR3) upon VPS29 suppression (Figure 3E-F). Together these data further support a DSCR3, C16orf62 and VPS29 retriever complex.

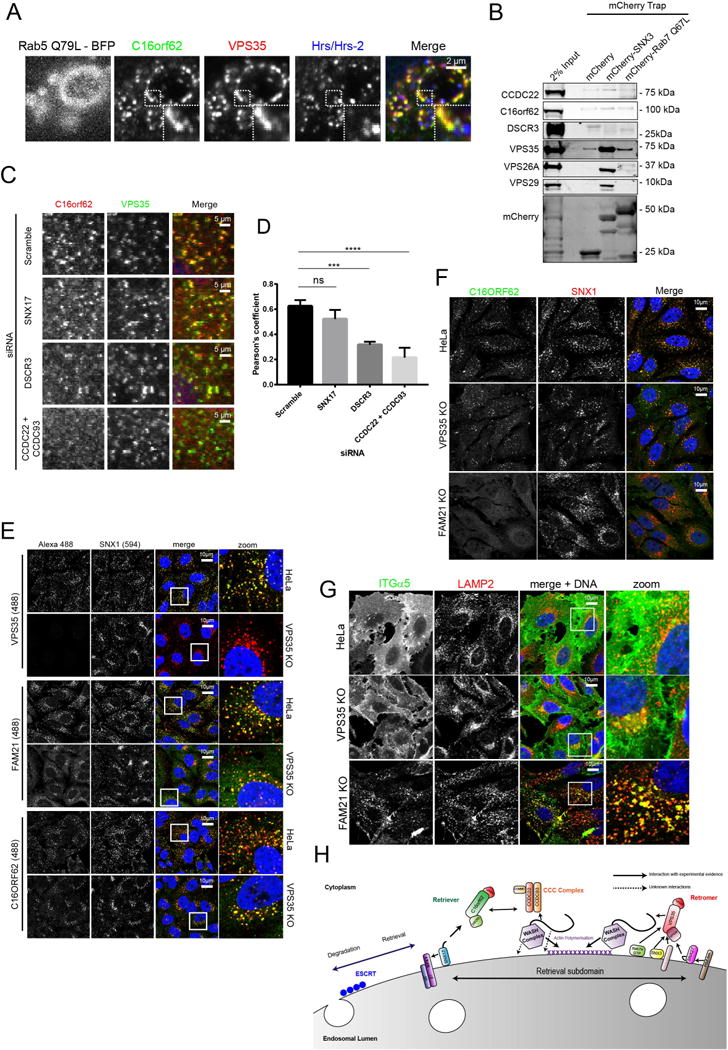

Retriever and retromer utilise distinct targeting mechanisms to reside on the same endosomal sub-domain

To probe the distinction between retriever and retromer further we examined the localisation of retriever. Using an antibody against endogenous C16orf62 we observed co-localisation with the other retriever components on SNX17-labelled endosomes (Figure S3A-C). These endosomes were positive for retromer and the WASH complex (Figure S3A-C). Swelling of individual endosomes through expression of a constitutively active Rab5 (Rab5(Q79L))46 established that endogenous retriever and retromer resided on the same endosomal sub-domain, and that this ‘retrieval’ sub-domain was distinct to the ESCRT sub-domain (Figure 4A).

Figure 4. The retriever complex requires the CCC and WASH complexes for endosomal localisation.

(A) Retriever and retromer co-localise on a retrieval subdomain distinct from the ESCRT subdomain. HeLa cells transiently transfected with Rab5 Q79L–BFP were methanol fixed and stained for the indicated endogenous proteins. A representative fields of view from n=3. For clarity the BFP channel has been excluded from the merged images and Hrs/Hrs-2 has been false coloured in blue. (B) Retriever or the CCC complex do not interact with proteins involved in endosomal recruitment of retromer. mCherry traps from HEK293 cells. Representative Western blot from n=2. (C) Retriever requires the CCC complex for endosomal localisation. HeLa cells were transfected with siRNA targeting the indicated proteins. Endogenous C16orf62 and VPS35 localisation were analysed by confocal microscopy. Representative field of view from n=3. See supplementary figure4A for lower magnification images. (D) Quantification of C. Pearson’s coefficient between C16orf62 and VPS35 under the indicated suppressions. 3 independent experiments were analysed. Total cell numbers analysed; Scr=144 cells, SNX17 =140 cells, DSCR3=146 cells, CCDC22+CCDC93=134 cells. Pearson’s coefficient values were compared to scramble control using one-way ANOVA and Dunnett test. **** p<0.0001, *** p<0.001, ns non-significant. Error bars represent s.d. (E) Endosomal localisation of retriever is independent of retromer. Parental HeLa cells along with VPS35 KO HeLa cells were fixed and stained for endogenous SNX1 as well as VPS35, FAM21 or C16orf62. Representative field of view. (F) Retriever requires FAM21 for its localisation to endosomes. Parental HeLa or KO HeLa cells for VPS35 or FAM21 were fixed and stained for endogenous localisation of C16orf62 and SNX1. Representative field of view. (G) FAM21 KO HeLa cells display a α5-integrin miss-sorting phenotype. Distribution of α5-integrin was analysed in parental HeLa cells, VPS35 KO or FAM21 KO HeLa cells. LAMP2 was used as a marker of lysosomes. Representative field of view. (H) Working model for the endosomal localisation of retriever.

Like retromer, the proteins that comprise retriever are not predicted to contain intrinsic membrane binding domains. Retromer is recruited to endosomes through association with SNX3 and Rab7-GTP12, 13, 47, 48. mCherry traps of mCherry tagged SNX3 and a constitutively active GTP loaded Rab7a (Rab7(Q67L)) established that these recruitment factors do not associate with retriever or the CCC complex (Figure 4B).

SNX17 associates with the endosomal membrane through avidity based interactions with phosphoinositides and cargo37. However, suppression of SNX17 did not perturb retriever endosome association (Figure 4C-D and Supplementary Figure 4A). Suppression of DSCR3 partially reduced, the association of C16orf62 with retromer positive endosomes (Figure 4C-D and Supplementary Figure 4A), suggesting that the interaction between DSCR3 and C16orf62 may be important but not essential for retriever recruitment to endosomes. Suppression of the CCC complex however perturbed the localisation of retriever to endosomes without affecting retromer (Figure 4C-D and Supplementary Figure 4A). The CCC complex is therefore required for targeting retriever to endosomes.

Targeting of the CCC complex to endosomes requires the WASH complex component FAM2139. FAM21 is recruited to endosomes through binding to retromer20–22. To establish if retromer is needed for localisation of retriever we used VPS35 KO cells (Supplementary Figure 1B-D). In these cells, retriever retained association with endosomes (as defined by the retromer binding SNX-BAR protein SNX1) although at slightly reduced levels (Figure 4E). This is consistent with VPS35 not being essential for SNX17 and retriever dependent sorting of α5β1-integrin (Supplementary Figure 1B-D). Interestingly, even though FAM21 became more cytosolic in our VPS35 KO cells, a significant pool of FAM21 retained association with SNX1-labelled endosomes (Figure 4E). FAM21 and the WASH complex are therefore recruited to endosomes through retromer-dependent20, 21 and retromer-independent mechanism(s).

The CCC complex requires the WASH complex for its localisation to endosomes39 so we asked if the WASH complex is required for the endosomal association of retriever. In a FAM21 KO HeLa cell line, the retriever subunit C16orf62 was completely cytosolic while the localisation of the retromer SNX-BAR SNX1 was unaffected (Figure 4F, Supplementary Figure 4B). Moreover, the loss of retriever localisation translated into a functional phenotype, as FAM21 KO cells displayed α5β1-integrin mis-sorting into lysosomes (Figure 4G, Supplementary Figure 4C). Again, only minor lysosomal mis-sorting was observed in the corresponding VPS35 KO HeLa cells (Figure 4G, Supplementary Figure 4C). This minor phenotype may arise from the partial loss of FAM21 from endosomes and hence a partial loss of retriever endosome association.

From these data, we propose a working model (Figure 4H) where the WASH complex is localised to endosomes via a retromer-independent mechanism that may, in part, rely on the direct ability of the WASH complex to bind lipids21, 23. WASH recruits the CCC complex through direct interactions of CCDC93 with the WASH complex component FAM2139. In turn, the CCC complex aids the recruitment of retriever to the endosomal membrane where it can engage the SNX17 cargo adaptor (see below). In this way, the endosomal sorting of SNX17 cargo proteins is achieved independent of retromer via a WASH-dependent pathway that relies on retriever and the CCC complex.

Evolutionary analysis suggests that retriever, the CCC and WASH complexes have co-evolved

Retromer is present in all eukaryotes and DSCR3 duplicated from VPS26 before the VPS26 duplication into VPS26A and VPS26B43. However some species, including fungi, have not retained DSCR343. We used the CLIME computational algorithm49 to map the evolutionary conservation of retriever. This algorithm identifies species in which the gene of interest is conserved and generates evolutionary conserved modules of genes that are inferred to have co-evolved with the target gene. When C16orf62 was used, the CCC and the WASH complexes were strongly inferred to have co-evolved with retriever (Supplementary Figure 4C). This agrees with the WASH complex being essential for the recruitment and function of the CCC complex and retriever (Figure 4F-G)39. These complexes also have an ancient origin, being present in the last common eukaryotic ancestor. However, retriever, the CCC and WASH complexes are selectively lost in some species, including all fungi, which have retained retromer7. The retention of retriever in metazoans suggests a fundamental role for retriever, alongside retromer, in orchestrating endosomal cargo retrieval and recycling.

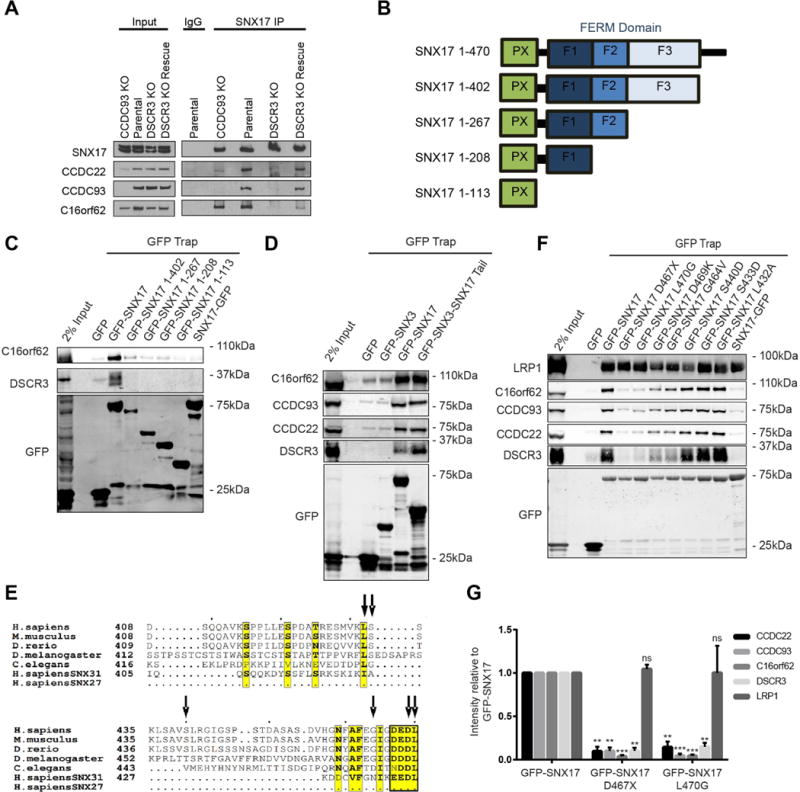

Retriever interacts with the evolutionary conserved carboxy-tail of SNX17

An outstanding question relates to precisely where within the WASH-CCC-retriever axis SNX17 associates to provide sequence-dependent cargo recognition and entry into the pathway. To answer this we performed SNX17 immunoprecipitations in CCDC22 and CCDC93 (core components of the CCC complex) KO HeLa cell lines (Figure 5A and Supplementary Figure 5). In agreement with our prior observations39, this resulted in a substantial reduction in the other component of the stable CCDC22:CCDC93 heterodimer. Under these conditions, the association of endogenous SNX17 with retriever was unaffected (Figure 5A and Supplementary Figure 5A).

Figure 5. The evolutionary conserved carboxy-terminal tail of SNX17 interacts with DSCR3.

(A) Endogenous SNX17 immunoprecipitation and Western blot analysis in HeLa cells, including either CCDC93 or DSCR3 KO lines and DSCR3 KO cells following DSCR3 re-expression (DSCR3 KO Rescue). Representative of n=3. (B) Schematic of the domain organisation of SNX17 and truncation mutants. (C) The carboxy-terminal tail of SNX17 is required for binding to retriever. Western analysis of GFP traps from tagged SNX17 truncation mutants expressed in HEK 293 cells. Representative blot from n=3 (D) The carboxy-terminal tail of SNX17 is sufficient to engage retriever and the CCC complex. GFP traps of GFP-SNX3-SNX17 tail chimeras expressed in HEK 293 cells. Representative blot of n=3 (E) Sequence alignment of the SNX17 tail from across species. Yellow indicates high levels of sequence homology. Arrows indicate residues mutated and the black box represents the four amino acids deleted in the D467X mutant. (F) A SNX17 L470G mutation abrogates binding to retriever and the CCC complex. GFP traps and Western analysis of tagged SNX17 site-directed mutants (indicated in E) expressed in HEK 293 cells. Representative blot from n=3. (G) Quantification of (F). Band intensities were measured from n=3 using Odyssey software. Band intensities were normalised to GFP expression and are presented as the average fraction of the GFP-SNX17 control. Error bars represent S.E.M. Mutants were compared to WT using one-way ANOVA and Dunnett test. *** p<0.001, ** p<0.01, ns non-significant.

In contrast, CRISPR/Cas9 mediated deletion of DSCR3 (Supplementary Figure 5B) abrogated the interaction of SNX17 with retriever and the CCC complex, which could be rescued by DSCR3 re-expression (Figure 5A). Importantly, DSCR3 deficiency did not affect the expression of CCDC22, CCDC93 or C16orf62, neither did it affect their subcellular localization or their ability to form the CCC complex (Figure 5A, Supplementary Figure 5 B-E). Consistent with DSCR3 siRNA suppression (Figure 2A), DSCR3 null cells displayed defective recycling of α5β1-integrin (Supplementary Figure 5 F-G). These results establish that SNX17 likely associates with retriever via DSCR3 and not through the CCC complex.

To further evaluate the mechanism of SNX17 association with retriever, we re-focused on our initial observation that occlusion of the carboxy-terminal tail of SNX17 has a pronounced functional effect on α5β1-integrin sorting (Figure 1D). Indeed, this tail was necessary for SNX17 to associate with retriever (Figure 5B-C, Supplementary Figure 6A). Fusion of the last 68 amino acids of SNX17 (residues 402-470) onto SNX3, an unrelated sorting nexin that we have shown does not associate with these proteins (Figure 4B), resulted in the complete transfer of retriever binding (Figure 5D).

The tail of SNX17 contains a number of highly conserved residues (Figure 5E) and deletion of the extreme carboxy-terminus (last 4 amino acids, 467-470), or a point mutation of the terminal residue of human SNX17(L470G) was sufficient to abrogate binding (Figure 5F-G). These mutants retained endosomal association and the ability to bind to NPxY cargo such as LRP1 (Figure 5F-G, Supplementary Figure 6B). Finally, SNX31, a closely related protein to SNX17 that is functionally involved in integrin trafficking50, associates with retriever through a similar carboxy-terminal motif (Supplementary Figure 6C).

The association between SNX17 and retriever is highly conserved and essential for retrieval of NPxY/NxxY motif containing cargos

SNX17 null HeLa cell lines, generated by CRISPR-Cas9, displayed a strong α5β1-integrin phenotype, identical to that seen using siRNA suppression (Supplementary Figure 7A-E). In these cells, only re-expression of wild type SNX17 rescued α5β1-integrin recycling, while the SNX17(L470G) mutant completely failed to rescue (Figure 6A-D). The association of SNX17 with retriever is therefore essential for endosomal retrieval and recycling of α5β1-integrin.

Figure 6. The interaction between SNX17 and DSCR3 is evolutionary conserved and essential for the endosomal sorting α5β1-integrin.

(A) WT SNX17 but not SNX17 L470G can rescue the α5β1 phenotype observed in SNX17 null cells. Protein lysates from parental HeLa cells, SNX17 KO or SNX17 KO cells transduced to express untagged SNX17 or SNX17(L470G) at endogenous levels were subjected to Western blot analysis. Representative blot from n=3. (B) Total levels of α5β1-integrin from A were quantified from n=3. (C) SNX17 L470G can not rescue the lysosomal localisation of α5β1 observed in SNX17 null cells. SNX17 KO HeLa cells were transduced with untagged SNX17 or SNX17(L470G). Untransduced KO cells were used as a control. Cells were fixed and stained with DAPI and against the lysosomal marker LAMP1 and α5-integrin. Representative field of view. (D) Quantification of C. (E) The interaction between SNX17 and retriever is evolutionary conserved. GFP trap of GFP-SNX3-Drosophila-SNX17 tail and equivalent carboxy-terminal mutation (L490G) expressed in human HEK 293 cells. Representative blot of n=3.

As discussed previously, retriever and the CCC complex are highly evolutionarily conserved (Supplementary figure 4D), and SNX17 is conserved in Drosophila melanogaster (Figure 5E). We therefore generated a fusion protein comprising human SNX3 linked to the last 99 amino acids of Drosophila Snx17 (CG5734). When expressed in human HEK293 cells this chimera displayed the ability to bind to human retriever, an interaction that was lost with the terminal Drosophila Snx17(L490G) mutant (Figure 6E). The mechanism of SNX17 association with retriever is therefore highly conserved.

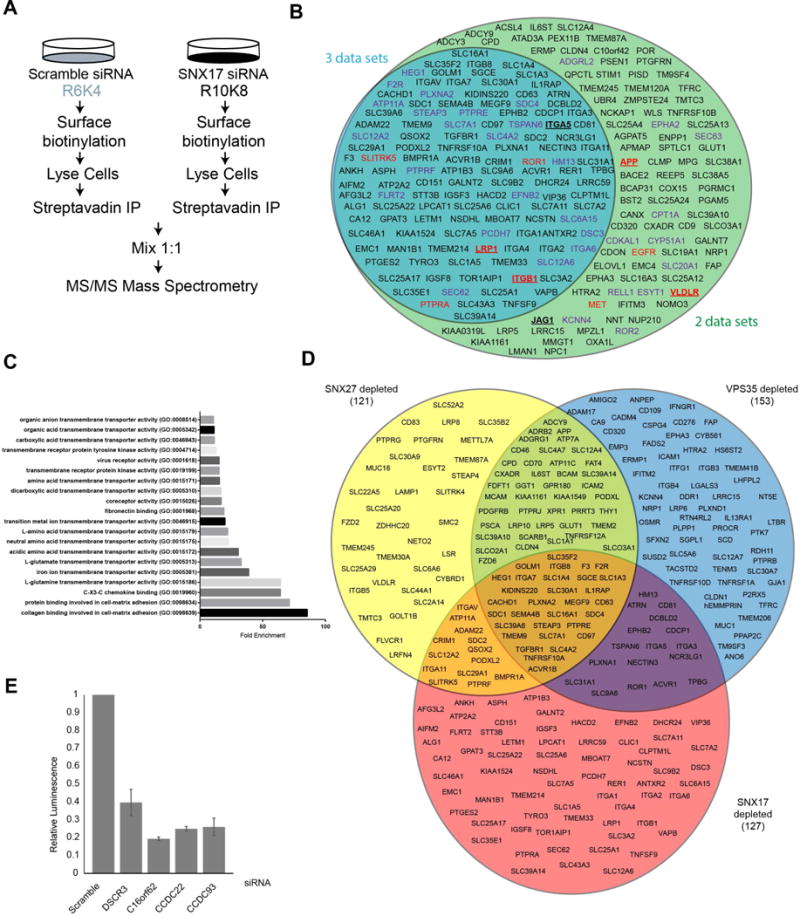

SNX17 and the retriever pathway are required for the endosomal retrieval and recycling of numerous cell surface cargo proteins

Previously, we have used unbiased global proteomics to quantify the remodelling of the cell surface proteome upon the perturbation of the SNX27-retromer endosomal retrieval and recycling pathway18. We therefore applied this methodology to achieve a more global, system level view of the SNX17-retriever pathway, for the homeostatic regulation of the cell surface proteome. In three independent experiments, using siRNA to knock-down SNX17 in SILAC-labelled HeLa cells, we biotinylated the cell surface and isolated biotinylated proteins through streptavidin-affinity capture (Figure 7A). Of a total of over 3,300 quantified proteins, 225 membrane proteins were lost by more than 1.4-fold from the surface of SNX17 depleted cells compared to control cells in at least 2 independent experiments (Figure 7B, Supplementary Figure 7F and Table S2). Among proteins decreased from the surface were established SNX17 cargoes β1-integrin, LRP1, APP, JAG1 and VLDLR, which validated our experimental approach26, 32, 33, 51, 52. Gene ontology analysis indicated that this data set was enriched in integral proteins required for cell adhesion, such as numerous integrins and a variety of other cellular adhesion molecules, including protocadherin-7 and plexin A1. A wide array of functionally distinct nutrient transporters including SLC7A11 (cysteine/glutamate transporter), SLC9A6 (sodium/hydrogen exchanger), SLC6A15 (a neutral amino acid transporter) and a plethora of signalling receptors such as TYRO3, ROR1 and MET were also decreased (Figure 7B-C). Some of these proteins contain NxxY motifs previously shown in vitro to bind to SNX1737, providing supporting evidence of a role for SNX17 in the recycling of these cargos (Figure 7B). To validate the role of the retriever in the sorting of these cargos we analysed LRP1, an established SNX17 cargo protein33. This revealed that the steady-state cell surface level of LRP1 was dependent upon SNX17 and a functional retriever complex (Supplementary Figure 7G).

Figure 7. Global, quantitative analysis of the cell surface proteome reveals that SNX17 dependent retrieval of cargo regulates integrins, cell adhesion molecules, nutrient transporters and signalling receptors.

(A) Schematic of surface biotinylation coupled to SILAC based proteomics. (B) Integral proteins lost more than 1.4-fold and identified by 2 or more unique peptides. Blue circle represents integral proteins reduced in three independent experimental replicates, green circle represents proteins reduced in two. Bold and underlined proteins: established SNX17 cargo, Red proteins: cargo with NPxY motifs known to be engaged by SNX17, Purple: proteins which contain an NxxY motif in a cytosolic region. (C) Gene ontology search of (B) using Panther59. (D) Comparison of integral proteins lost from the surface following SNX17 suppression in 3 independent experiments and from published studies following SNX27 or VPS35 suppression18. (E) Knock-down of retriever reduces HPV infection. HPV pseudovirions, containing a luciferase reporter, were added to HaCaT cells which were suppressed for the indicated proteins. Infection was monitored 48 hours later by analysing firefly luciferase activity in cell lysates.

We next compared the cell surface proteome of SNX17 depleted cells with our published cell surface proteomes in VPS35 or SNX27 suppressed cells (Figure 7E). SNX17 cargo such as β1-integrin are only reduced at the cell surface following SNX17 suppression but not VPS35 or SNX27 suppression, consistent with the SNX17-retriever pathway not needing retromer for its function. However, a population of SNX17-dependent integral proteins do have reduced plasma membrane levels under SNX27 or retromer suppression, suggesting that for these cargoes their recycling may be mediated by both retriever and retromer pathways (Figure 7E and 4A).

Finally, the L2 capsid proteins of various HPV types contain a highly conserved NPxY motif, through which it can engage SNX17, an interaction that is necessary for viral DNA to avoid lysosomal degradation and reach the nucleus53. Consistent with this, suppression of retriever and the CCC complex reduced the number of HPV pseudovirions reaching the nucleus, thus indicating the essential role of retriever in HPV infection (Figure 7F and Supplementary Figure 7G). Together these data implicate that the newly discovered SNX17-retriever endosomal recycling pathway is essential for regulating the cell surface expression of many integral proteins and is exploited by at least one viral pathogen.

DISCUSSION

We have discovered an evolutionary conserved multi-protein complex that is structurally and functionally related to retromer. Composed of a heterotrimer of DSCR3, C16orf62 and VPS29 we have called this complex ‘retriever’. In associating with the CCC and the WASH complexes, retriever localises to endosomes to drive the retrieval and recycling of NPxY/NxxY motif-containing cargo proteins by coupling to SNX17 (and SNX31), a cargo adaptor essential for the homeostatic maintenance of numerous cell surface proteins associated with processes which include cell migration, cell adhesion, nutrient supply and cell signalling. This evolutionary ancient transport route is distinct from the retromer pathway (Figure 4H). The discovery of retriever constitutes a significant step toward achieving a thorough molecular understanding of those mechanisms that regulate sequence-dependent endosomal cargo retrieval and recycling.

Retriever draws many parallels with retromer. The most obvious being that the two complexes share a similar composition and architecture; retriever and retromer are heterotrimers that contain a VPS29 subunit, a protein with an arrestin-like fold (either DSCR3 or VPS26A/B respectively) and a protein containing a series of HEAT-repeats (C16orf62 or VPS35 respectively). In addition, each complex associates with a cargo specific adaptor; SNX17 interacts with retriever and SNX27 interacts with retromer, thereby providing sequence selective cargo entry into these retrieval and recycling pathways.

SNX17 along with SNX27 and SNX31 are classified as members of the SNX-FERM family of sorting nexins defined by a FERM-like domain54. Of these, SNX17 and SNX31 are the most closely related (although SNX31 expression is restricted, with high expression in the urinary tract) and both are important in the recycling of various integrins50, 55. Consistently both SNX17 and SNX31 possess the conserved carboxy-terminal motif that is necessary and sufficient to bind to retriever. Conversely, SNX27 interacts with retromer through its PDZ domain17 and lacks the tail sequence to associate with retriever. Although SNX27 possesses a FERM-like domain which has the ability to bind to NPxY/NxxY sequence motifs37, it is apparent in our assays for β1-integrin recycling, that the SNX27-retromer pathway cannot compensate for the loss of the SNX17-retriever pathway. Whether this is the case for all NPxY/NxxY motif-containing cargos or whether some cargo can be sorted by either of the two pathways remains to be established. In this regard, the phosphorylation state of the tyrosine within the NPxY/NxxY sorting motif may influence the relative binding between SNX17 and SNX27, with SNX27 preferring a phosphorylated tyrosine54. Post-translational modifications may therefore play an important role in the sorting between lysosomal degradation and retrieval, as for ubiquitination in the ESCRT pathway, and in the sorting between the retromer and retriever pathways.

A further similarity between retriever and retromer is that both complexes depend upon the WASH complex for endosomal cargo sorting. The retromer subunit VPS35 binds to multiple LFa repeats in the FAM21 tail and this interaction is suggested to be sufficient and essential to recruit the WASH complex to endosomes20, 21. We have shown however that in a VPS35 KO cell line a significant proportion of FAM21 remains associated with the endosomal network. This clearly establishes that in human cells the endosomal association of FAM21 and WASH is mediated through both retromer-dependent and retromer-independent mechanisms, a conclusion that is in agreement with work in Dictyostelium describing the retromer-independent recruitment of the WASH complex56. While the mechanism for retromer-independent association of the WASH complex to endosomes remains to be established it is perhaps worth noting that the WASH complex has an inherent ability to bind to phospholipids21, 23.

Our data is consistent with retriever interacting with FAM21 through its interactions with the CCC complex39. We have established that the WASH-FAM21-CCC axis is essential for the localisation of retriever to endosomes, an observation that is consistent with these complexes having co-evolved. Importantly, the identification of the WASH-FAM21-CCC-retriever-SNX17 pathway provides a mechanism to account for several studies that have shown a role for the WASH complex in α5β1-integrin recycling even though the sorting of this cargo is known to be retromer-independent26, 56–58. WASH dependent α5β1-integrin recycling requires retriever in order to couple sequence-dependent cargo recognition through SNX17 with actin polymerisation necessary for subsequent recycling. In addition, the establishment of functionally distinct retriever-WASH and retromer-WASH cargo sorting pathways serves to further highlight the essential role that the WASH complex plays in the organisation and function of the endosomal network. Interestingly WASH, CCC complex, retriever and retromer are all spatially overlapping in an endosomal ‘retrieval’ sub-domain.

We have highlighted the importance of SNX17 in sequence-dependent selection of cargo for inclusion into the retriever pathway and through quantifying the global effect of SNX17 suppression on the cell surface proteome we have implicated this pathway in the regulation of cell adhesion, nutrient supply and cell signalling. In demonstrating that the NPxY/NxxY motif - containing L2 capsid protein of HPV hijacks the retriever pathway, we have also provided initial evidence of the importance of this pathway in the infectivity of at least one viral pathogen.

In conclusion, we have identified an evolutionary conserved, retromer-independent pathway that drives endosomal retrieval and recycling of a wide range of cell surface proteins. Analogous to retromer, retriever likely functions as a central scaffold that serves as a recruiting hub to establish a cargo selective retrieval sub-domain that prevents cargo from entering the ESCRT lysosomal pathway. Based upon our data we propose that C16orf62 should be renamed VPS35-like (VPS35L) and DSCR3 should be renamed to VPS26C as there is evidence that this gene duplicated from the original VPS26 gene 43. Therefore the retriever becomes VPS26C:VPS35L:VPS29. So, while retriever and retromer clearly play distinct roles in endosomal recycling, their shared basic design suggests a conserved underlying principle that governs their function.

METHOD DETAILS

Antibodies

The following antibodies were used in this study (WB: Western blot, IF: Immuno-fluorescence): rabbit anti-SNX17 (Proteintech, 10275-1-AP, WB), rabbit anti-SNX17 (Atlas antibodies, HPA043867, IF), mouse anti-EEA1 (BD Biosciences, 610457, IF), mouse anti-LAMP1 (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, H4A3, IF), mouse anti-GFP (Roche, 11814460001, WB), rabbit anti-CCDC22, (Proteintech, 16636-1-AP, WB), rabbit anti-CCDC93, (Proteintech, 20861-1-AP, WB), rabbit anti-C16orf62 (Abcam, ab97889, WB), rabbit anti-C16orf62 (Pierce, PA5-28553, IF), rabbit anti-DSCR3 (Merck Millipore, ABN87, WB), rabbit anti-integrin α5 (Abcam, ab150361, IF), rabbit anti-integrin α5 (Santa Cruz, SC-10729, WB), rabbit anti-integrin β1 (Abcam, ab52971, WB), rabbit anti-VPS35 (Abcam, ab157220, IF/WB), goat anti-VPS35 (Abcam, ab10099, IF), rabbit anti-VPS29 (Abcam, ab98929, WB), rabbit anti-VPS26A (Abcam, ab137447, WB), rabbit anti-FAM21 (as previously described22, IF/WB), mouse anti-β actin (Sigma, A1978, WB), rabbit anti-LRP1 (Abcam, ab92544, WB), mouse anti-Hrs/Hrs-2 (Enzo, ALX-804-382-C050, IF), mouse anti-TfnR (Invitrogen, 13-6890, WB), mouse anti-rabbit IgG conformational specific (Cell Signalling Technology, #3678). Antibodies against COMMD proteins were generated by immunising animals with recombinant protein as previously described39, 40. For Odyssey detection of Western blots, the following secondary antibodies were used; donkey anti-mouse 680 (Life Technologies), donkey anti-rabbit 680 (Life Technologies), donkey anti-rabbit 800 (Life Technologies).

SILAC interactome proteomics

SILAC based interactomes were generated as previously described26. Briefly, GFP, GFP-SNX17 and SNX17-GFP transduced RPE-1 cells were grown in light (R0K0), medium (R6K4) or heavy (R10K8) SILAC media respectively for at least 6 doublings. Cells were lysed in lysis buffer (40 mM Tris-HCl, 0.5% NP40, 1x protease inhibitor cocktail, pH 7.5). Cell lysates were cleared before GFP was immunoisolated using Chromotek GFP nanotrap beads at 4oC for 1 hour. Beads were thoroughly washed with lysis buffer and then beads from the three conditions were pooled. GFP and interacting proteins were eluted from beads in 2X NuPAGE® LDS Sample Buffer (Life Technologies). Proteins were then separated by SDS-PAGE and analysed by LC-MS/MS mass spectrometry.

Quantitative cell surface proteomics

HeLa cells were labelled with medium (R6K4) or heavy (R10K8) SILAC media for at least 6 doublings to allow for full labelling. After full labelling was achieved, medium or heavy labelled cells were suppressed using either non-targeting or SNX17 targeting siRNA respectively and HiPerfect (Qiagen) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were surface biotinylated 72 hours post siRNA transfection with membrane impermeable biotin (Thermo) at 4oC to prevent endocytosis. Post-biotinylation, cells were lysed (1% Triton X-100, PBS, 1x protease inhibitor cocktail tablet (Roche) pH 7.5) and lysates cleared by centrifugation. Some lysate was retained to assess knock-down of SNX17 by Western blot. Equal amounts of protein from control and SNX17 knockdown were then added to streptavidin sepharose to capture biotinylated proteins. Streptavidin beads and lysates were incubated for 30mins at 4oC before washing in PBS containing 1.2 M NaCl and 1% Triton X-100. Beads were then pooled and proteins eluted in 2X NuPAGE® LDS Sample Buffer (Life Technologies) by boiling at 95oC for ten minutes. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and analysed by mass-spectroscopy as previously reported18.

Overlap PCR

SNX3-SNX17 and SNX3-Drosophila-SNX17 chimeras were generated using overlap PCR. SNX3 and tail regions of SNX17/Drosophila SNX17 were amplified using PCR and subsequently purified. The PCR primers were designed so that the antisense SNX3 primer and the sense SNX17 tail primer contained a DNA sequence encoding a glycine-serine linker (3X GS, ggtagcggcagcggtagc) at the 5′. A second round of PCR then occurred using SNX3 sense and SNX17 antisense primers and the purified SNX3 and SNX17 fragments from the previous PCR reactions as DNA templates. The 3X GS linker linked to the fragments in the first PCR reaction were then annealed to each other during the annealing stage of a second PCR. This enabled the DNA polymerase to extend the DNA sequence from the annealed linker as well as from the 5′ and 3′ ends of the fragments using the primers added thus generating a chimeric PCR product which contained SNX3 linked to SNX17 tail via the 3X GS amino acid linker.

Site Directed Mutagenesis (SDM)

Point mutations of various constructs were generated using site directed mutagenesis. PCR primers that contain desired mutations were designed using the Aligent Technologies QuikChange Primer Design Programme (https://www.genomics.agilent.com/primerDesignProgram.jsp). After PCR, non-mutated template vector was removed from the PCR mixture through digestion for 1 hour at 37°C by the enzyme Dpn1. Following digestion by Dpn1, 1 μl of the mixture was transformed into chemically competent E. coli and plated on suitable antibiotic-containing agar plates. Several colonies were picked, cultured overnight and plasmid DNA purified. Sequencing of purified plasmid DNA established whether the desired mutation had been introduced.

Cell culture

Cells were grown in incubators at 37°C, 5% CO2. All tissue culturing materials were sterile and tissue culture was performed in Class II vertical laminar flow cabinets.

Transfection of constructs

HEK cells for GFP immunoprecipiation were transfected using a PEI transfection agent. HEK cells were split a day before transfection so that they would be 80-90% confluent on the day of transfection. For a 10 cm dish, 2.5 ml Optimen was added to 0.5 μl PEI and this mixture was filtered. 7.5 μg of DNA was added to 2.5 ml Optimen in a separate tube. Then the two tubes were mixed and incubated at room temperature for 20 minutes. Media was removed from the cell dishes, cells washed in PBS and the DNA PEI mixture added to the dish. The transfection mixture was removed 6 hours later and media was replaced on the cells. Cells were then left for 48 hours.

HeLa cells for imaging analysis were transfected using FuGene. For cells which had been seeded onto coverslips in a 12 well dish, 1 μg DNA was added to 100 μl Optimen and 3 μl FuGene HD.

This mixture was incubated for five minutes at room temperature. After incubation the mixture was added dropwise to wells and cells were left 24 hours before fixing for image analysis.

siRNA suppression

Cells were subjected to reverse siRNA suppression using Dharmafect (Dharmacon) according to manufacturer’s instructions. After 48 hours cells were then subjected to fast forward siRNA suppression using Dharmafect according to manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were then left another 48 hours before processing for respective experiments. The following siRNA oligos were used (5′-3′): SNX17 (ccagugauguccacggcaa), C16orf62 (acaaugccuugcuguugaa, auagucauccaguguuca, aucguuccuucuggaauuc), DSCR3 (guaacaaaguucuguauga, caaacugugucaucacgca), VPS29 (augugaaaguagaacgaau, caagugaaacuacggauau, ugagaggagacuucgauga, auauuaaaguggacgagau), CCDC22 (ccacugagcugguuguaga, ccaagacuggugcuccuaa), CCDC93 (ccguauaucaccuacaaga, gauuguguccgaguaugca), VPS35 (guuguuaugugcuuagua, aaauaccacuugacacuua), scramble (Dharmacon ON-TARGETplus non-targeting siRNA #2).

For SNX17 rescue experiments, cells were transfected with a siRNA resistant GFP-SNX17 or SNX17-GFP construct 24 hours prior to fixation. FuGene was used for the transfection according to manufacturer’s protocol. The siRNA resistant constructs were created by site directed mutagenesis and generated silent mutations in SNX17 from 1359-CAGT-1362 to 1359-ATCC-1362.

Lentiviral Lines

For lentiviral production, required constructs were cloned into the pXLG3 vector and transfected into HEK cells along with Pax2 and pMDG2 plasmids. Virus was harvested 72 hours post transfection. Virus was then filtered before titrating the virus with RPE-1/HeLa cells for 48 hours.

CRISPR/Cas-9 gene editing

VPS35, FAM21, SNX17 and DSCR3 knock-out cells were generated using CRISPR-Cas9 as previously reported39.

Integrin recycling assay and degradation kinetics

For the integrin recycling assay, control, SNX17 or CCDC93 knock-down cells were labelled as previously described26. Briefly, cells were incubated with antibody against integrin β1 for 1 hour at 37oC. Cell surface antibody was then stripped (PBS, pH 2.5). Cells were then incubated at 37oC for the indicated time points at which cells were fixed and processed for imaging. Cell surface labelling in siRNA suppressed cells was achieved as for SILAC based cell surface proteomics. However, beads were not pooled and instead different conditions were analysed separately by Western blot analysis. Lysosomal degradation of α5β1 was rescued through the addition of leupeptin to cells which have been transfected with siRNA for 72 hours, as previously described26. To assess α5β1 integrin degradation, cells which had been incubated with siRNA oligos for 72 hours were then treated with 10 μg/ml cycloheximide for 0, 3, 6 or 9 hours. Cells were lysed (PBS, 1% Triton X-100, protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche), pH 7.5) and protein levels analysed by Western blotting.

Immunofluorescence staining

Cells were seeded onto sterile 13 mm coverslips. Media was removed from the dish containing the coverslips and coverslips were washed once with PBS prior to fixing with 4% ice-cold PFA (paraformaldehyde) for 25 minutes. Following fixation, coverslips were washed three times with ice-cold PBS and permeabilised with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 6 minutes. Alternatively, cells were fixed with ice cold methanol for five minutes. Coverslips were then washed again three times with PBS and then blocked with 1% BSA in PBS for 15 minutes. Primary antibody was diluted to the required concentration in 1% PBS and 60 μl was dotted onto a clean piece of parafilm. Coverslips were placed onto the droplets containing primary antibody in an orientation such that the cells were immersed into the liquid. Incubation for one hour at room temperature then occurred. Coverslips were then washed again with PBS three times before placing on a second droplet containing fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibody and DAPI stain diluted in 1% BSA in PBS. Coverslips were then incubated at room temperature for one hour in the dark, to prevent quenching of the fluorophores. Following incubation, coverslips were washed three times in PBS and washed a final time in water before mounting with Fluoromount (Sigma) onto glass slides. Slides were left to dry overnight prior to imaging.

Confocal microscopy

A Leica confocal scanning laser (Leica SP5) microscope with a 63× oil immersive objective was used to obtain confocal images of fixed cells.

Cell lysis and GFP traps

Cells transfected with GFP or GFP tagged protein constructs were lysed 48 hours post transfection. Dishes containing the cells were placed on ice, the media was removed and the cells were washed three times with ice cold PBS (Sigma). 500 μl or 1 ml immunoprecipitation lysis buffer (20 mM Hepes pH 7.2, 50 mM potassium acetate, 1 mM EDTA, 200 mM D-sorbitol, 0.1% Triton X-100, 1x protease cocktail inhibitor, pH7.5) was added to 10 cm and 15 cm dishes respectively. The lysates were cleared by centrifugation at 13,200 rpm for ten minutes at 4°C. 15 μl of GFP-trap beads (Chromotek, catalogue number gta-20) were equilibrated prior to adding cell lysate supernatants. Beads and lysates were incubated on a rocker at 4°C for 1 hour. Following incubation GFP-trap beads were pelleted and the supernatant removed. Beads were then washed by resuspending in lysis buffer, pelleting and removal of lysis buffer. This washing process was repeated three times in total. Once the final lysis buffer wash had been removed, beads were resuspended in 2X NuPAGE® LDS Sample Buffer (Life Technologies), 2.5% β-mercaptoethanol and boiled at 95°C for 10 minutes. The samples were then suitable for SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analysis.

Endogenous immunoprecipitation

HEK 293 cells were washed with cold PBS prior to lysis (20 mM Hepes pH 7.2, 50 mM potassium acetate, 1 mM EDTA, 200 mM D-sorbitol, 0.1% Triton X-100, 1x protease cocktail inhibitor, pH7.5). Lysates were cleared by centrifugation for 10 minutes at 13,000 rpm at 4 °C. Lysates were then incubated with either rabbit IgG control antibody or rabbit C16orf62/SNX17 overnight at 4°C on a roller. 2μg or 5μg antibody was used for C16orf62 or SNX17 immunoprecipitations respectively. Pre-washed protein G beads (GE Healthcare) were added to the lysates and these were further incubated for 1 hour at 4°C on a roller. The beads were then pelleted by centrifugation at 4 °C for 30 seconds at 4000 rpm. The beads were then washed 3 times in lysis buffer before resuspending the beads in 2X NuPAGE® LDS Sample Buffer (Life Technologies), 2.5% β-mercaptoethanol and boiled at 95°C for 10 minutes.

Western blotting

Nu-PAGE® 4-12% gradient Bis-Tris pre-cast gels (Life Technologies) were used to run protein samples. Gels were assembled into tanks and Nu-PAGE® MOPS running buffer was added. Protein samples were loaded into wells and 6 μl of All Blue Precision Plus Protein™ Prestained Standard (Bio-Rad) was loaded as a molecular weight ladder. Gels were ran at 100 V until the samples had migrated to the bottom of the gel, as indicated by the Bromophenol Blue dye in the sample buffer. Immediately after SDS-PAGE, proteins were transferred from gels to PVDF membranes for immunoblotting. PVDF membrane (Immobilion-FL, pore size 0.45 μm, Millipore, catalogue number IPFL00010) was activated in methanol (Sigma) for 5 minutes. Transfer occurred in transfer buffer (25 mM Tris, 192 mM glycine, 10% methanol) at 100 V for 70 minutes. Prior to antibody incubation, membranes were subjected to a blocking stage consisting of a 1 hour incubation at room temperature with 5% milk in TBS-TWEEN to prevent unspecific antibody binding. Primary antibodies were diluted in 2% milk TBS-TWEEN, added to the membranes after the blocking stage and incubated at 4°C overnight. Primary antibodies were then removed and the membranes washed with TBS-TWEEN for at least 5 minutes, repeated three times in total. Secondary antibodies were diluted in 2% milk TBS-TWEEN and incubated with the membranes at room temperature for 1 hour. Following incubation with secondary antibodies, membranes were washed once with TBS-TWEEN for 5 minutes and then washed twice, for at least 5 minutes each time, with 0.1% SDS in TBS-TWEEN. To detect the secondary antibodies the LI-COR Odyssey® system was used. This allows detection of secondary antibodies conjugated to fluorophores 800 or 680. Intensity of protein bands were generated using the LI-COR Odyssey® software.

When analysing endogenous immunoprecipitations a mouse anti-rabbit conformational specific antibody was incubated with the membranes in 2% milk TBS-TWEEN for 1 hour at room temperature after incubation with the primary antibody and prior to the addition of an anti-mouse secondary antibody. This was done to reduce background from the heavy and light chains of the IgG antibody used for the immunoprecipitation.

All Western quantification was done using the Odyssey software. Experiments where multiple gels were ran for protein detection, including load controls, the quantification was done on samples processed in parallel from the same independent experiment.

Recombinant protein expression using the MultiBac system

Human Strep-DSCR3, C16orf62 and VPS29-6xHis were expressed in Sf21 insect cells using MultiBac44. Briefly, Strep-DSCR3, untagged C16orf62 and VPS29-6XHis were cloned into pACEBac1, pIDC and pIDK respectively. For further details of these plasmids please see60. The expression constructs were then recombined by Cre/loxP reaction into a fused plasmid expressing Strep-DSCR3, C16orf62 and VPS29-6XHis. This plasmid was then transformed into DH10EMBacY E.coli cells carrying the MultiBac baculoviral genome in form of a bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC).The Strep-DSCR3/C16orf62/VPS29-6xHis co-expression construct was insertedinto the BAC by Tn7 transposition,. Composite bacmid was extracted, virus prepared and Sf21 insect cell cultures transfected as described44

Retriever complex purification

2L of Sf21 insect cells transfected with Strep-DSCR3/C16orf62/VPS29-6xHis baculovirus and harvested 48 hours post fater cell proliferation arrest44. Cells were harvested by centrifugation 4000 rpm for 20 minutes and resuspended in 70 ml lysis buffer (25mM HEPES pH 7.5, 300mM NaCl, 5mM β-mercaptoethanol) followed by sonication (Soniprep 150). Lysates were cleared by centrifugation at 20,000 rpm for 1 h at 4°C. Cleared lysates were added to a HisGraviTrap TALON column (GE Healthcare) preequilibrated in binding buffer (25mM HEPES pH7.5, 300mM NaCl, 5mM β-mercaptoethanol). Subsequently. the column was washed with wash buffer (25mM HEPES pH7.5, 300mM NaCl, 5mM β-mercaptoethanol, 20mM imidazole) followed by elution in 3ml elution buffer (25mM HEPES pH7.5, 300mM NaC, 5mM β-mercaptoethanol, 200mM imidazole). Eluted protein was concentrated and imidazole removed using a 3kDa Amicon centrifugal filter unit. Concentrated protein was injected into a Superdex200 size exclusion column pre-equilibrated in SEC buffer (25mM HEPES pH 7.5, 300mM NaCl, 5mM β-mercaptoethanol). Fractions corresponding to peaks were analysed by SDS-PAGE followed with Coomassie staining or Western blot analysis, respectively.

Pseudovirion production and infectivity assays

Pseudovirions (PsVs) with a packaged Luciferase reporter were generated by transfecting HEK 293TT cells with constructs expressing the various papillomavirus L1 and L2 open reading frames in codon-optimised bicistronic plasmid constructs along with luciferase reporter pCiLuci, as previously described61.For infectivity assays, HaCaT cells were seeded in a 12-well plate at a density 3 × 104/well. After adherence, siRNAs targeting SNX17, retriever, CCC complex and non-targeting siRNA were added to cells using Lipofectamine RNAiMax (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturers’s instructions. After 48 h, HPV-16 PsVs were added at a concentration of approximately 12 ng/mL. Infection was monitored 48 h later by luminometric analysis of firefly luciferase activity using a Luciferase Assay System kit (Promega) on cell lysates, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Efficiency of siRNA knockdown was confirmed by SDS-PAGE. Visualisation was carried out using an Amersham ECL Western blotting detection kit (GE Healthcare).

Supplementary Material

GFP-linker-SNX17 versus SNX17-GFP comparative triple SILAC proteomics. Related to figure 1.

Table S1 A Triple SILAC raw data

Table S1 B Filtered triple SILAC data

Table S1 C logScore and log(Heavy/Medium) of filtered SILAC data

Supplementary Table 2: Surface proteomics in SNX17 knock-down cells

Table S2 A Raw n of 1 data

Table S2 B Filtered n of 1 data

Table S2 C Integral proteins in n of 1

Table S2 D Raw n of 2 data

Table S2 E Filtered n of 2 data

Table S2 F Integral proteins in n of 2

Table S2 G Raw n of 3 data

Table S2 H Filtered n of 3 data

Table S2 I Integral proteins in n of 3

Table S2 J Integral proteins reduced in 2 independent experiments

Table S2 K Integral proteins reduced in 3 independent experiments

Supplementary Figure 1: SNX17 and VPS29 rescue experiments (A) Lower magnification images of Figure 1D. (B) Parental, VPS35 KO, VPS29 KO and VPS29 KO HeLa cells where VPS29 has been re-expressed (VPS29 KO rescue), were treated with 10 μg/ml cycloheximide for 0, 4 or 8 hours before lysis. Lysates were then analysed by Western blot for the indicated proteins. Representative blot n=3. (C and D) Quantification of B. Band intensities were measured using the Odyssey software. Band intensities of integrin alpha 5 or integrin beta 1 are represented as a % of the band intensity at 0 hours cycloheximide treatment for each of the four conditions. % of integrin in KO cells were compared to parental HeLa at each time point using t-test. Error bars represent s.d. ** p<0.01, * p<0.05.

Supplementary Figure 2: Production of recombinant human retriever complex using MultiBac44 (A) Strep-DSCR3, untagged C16orf62 and VPS29-6xHis were cloned into MultiBac plasmids pACEBac1, pIDC and pIDK, respectively. The resulting expression constructs were conjoined by Cre/loxP reaction44, giving rise to a co-expression construct combining all three genes. This construct was inserted into the EMBacY baculoviral genome and virus prepared as described44. Expression in Sf21 insect cells was followed by protein purification using immobilized metal affinity chromatography IMAC) and size exclusion chromatography (SEC), resulting in highly purified retriever complex. (B) SEC rofile of the recombinant retriever complex. (C) Analysis of the second peak in SEC by Coomeassie-stained SDS-PAGE evidences excess VPS29-6xHis.

Supplementary Figure 3: DSCR3, C16orf62 and VPS29 localise on retromer positive endosomes. (A) GFP-SNX17 transduced RPE-1 cells were fixed and stained for endogenous VPS35 and either C16orf62 or FAM21. Representative field of view from 3 independent experiments. (B) RPE-1 cells were transduced with GFP-VPS29. Antibodies against endogenous SNX17 or C16orf62 stained endosomes which were positive for GFP and VPS35. Images are a representative field from 3 independent experiments. (C) RPE-1 cells were transduced to express low levels of GFP-DSCR3. GFP labelled endosomes stained positive for endogenous C16orf62 and VPS35.

Supplementary Figure 4: The WASH complex co-evolved with retriever and is required for its endosomal localisation.

(A) Lower magnification images of figure 4C. (B) Validation of FAM21 knock-out in HeLa cells by immunofluorescence. (C) Quantification of Figure 4F. (D) The evolutionary conservation of C16orf62 was mapped using the CLIME algorithm (Li et al., 2014). The pattern of C16orf62 conservation created an evolutionary conserved module. All genes in the genome were then compared to this evolutionary conserved module, searching for genes which share similar patterns of conservation and are therefore in inferred to have co-evolved with C16orf62. Proteins which are inferred to have co-evolved with C16orf62 have a LLR higher than 0, with a higher score indicating increased likeliness of co-evolution. PG = paralogue group, LLR = log-likelihood ratio scale.

Supplementary Figure 5: Characterisation of DSCR3 knock-out HeLas. (A) Endogenous SNX17 IPs were performed in parental or CCDC22 knock-out HeLa cells. (B) Lysates from DSCR3 knock-out HeLas were analysed by Western blotting for knockout and effects on the levels of other proteins. (C) Endogenous CCDC22 immunoprecipitations (D) Immunofluorescence of indicated endogenous proteins in parental HeLa cells (E) Same as (D) but staining performed in DSCR3 knock-out HeLas. (F) Parental HeLas and knock-out DSCR3 HeLa cells were analysed by immunofluorescence for their distribution of integrin α5. Bottom panels represent zoomed images of the white boxes. (G) Parental or knock-out DSCR3 HeLa cells were either untransfected or transfected with Bafilomycin A to prevent lysosomal acidification. Lysates were then analysed by Western blotting against the indicated proteins.

Supplementary Figure 6: The C terminal leucine of SNX17 and SNX31 is essential in engaging retriever and the CCC complex. (A) GFP traps of HEK 293 cells expressing SNX17 mutants indicated in figure 4B. Representative Western blot from three independent experiments. (B) GFP-SNX17 or the indicated mutants were transiently transfected into RPE-1 cells. Cells were fixed and stained for EEA1 and DAPI. Representative fields of cells. (C) GFP traps and Western analysis of GFP-SNX17 or GFP-SNX31 and their equivalent loss of function mutations (L470G and L490G). Representative blot from three independent experiments.

Supplementary Figure 7: Characterisation of SNX17 knock-out HeLa cells, SNX17 knock-downs for cell surface proteomics and pseudo-virion infection.

(A) Parental HeLa cells or populations of SNX17 cells which have been targeted by CRISPR-Cas9 against either exon 1 or exon 2. Cells were fixed and stained for integrin α5 and the lysosomal marker LAMP1. (B) Cells in (A) were lysed and analysed by Western blot for knock-out of SNX17 and total levels of integrin α5. (C) Clonal selection of cells in (A and B). Cells grown from individual knock-out events were fixed and stained for integrin α5, LAMP1 and DAPI. E1C = Exon 1 Clone, E2C = Exon 2 Clone. (D) Total protein levels in parental or clonal SNX17 HeLa cells, where CRISPR-Cas9 activity has been targeted at exon 2, were analysed by Western blotting. (E) Same as in (D) but with HeLa cells which have had CRISPR-Cas9 targeted against exon 1 of SNX17. (F) Knockdowns of SNX17 in SILAC labelled HeLa cells used for cell surface proteomics. n=3 on one blot. (G) Steady-state cell surface analysis of indicated cargo proteins and their dependency on SNX17, retriever and retromer. HeLa cells were knocked-out for the indicated proteins using CRISPR/Cas9. Cell surface proteins were randomly biotinylated with a membrane-impermeable biotin conjugate. Cells were lysed and biotinylated proteins isolated with streptavidin sepharose followed by Western blotting. (H) siRNA knockdowns of cells used in pseudovirion infection assay.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Wolfson Bioimaging Facility at the University of Bristol and also the Life Imaging Center (LIC) of the University of Freiburg for their support.

P.J.C. is supported by the Medical Research Council (MR/K018299/1 and MR/P018807/1) and the Wellcome Trust (089928 and 104568). Funding to B.M.C. from the Australian Research Council (ARC) (DP160101743) and National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) (APP1058734). The NIH (R01DK073639, R01DK107733) supported E.B and (R01AI65474) D.D.B. LB gratefully acknowledges research support from the Associazione italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro. Wellcome Trust PhD Studentships from the Dynamic Cell Biology program (083474) supported K.E.M. and M.G. An NHMRC Dementia Fellowship (APP1097185) supported R.G., and B.M.C. is supported by an NHMRC Career Development Fellowship (APP1061574). F.S. is funded by the German Research Council (DFG) Emmy Noether grant (STE2310/1-1).

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Initial conceptualization, K.E.M., F.S. and P.J.C.; Evolution of conceptualization, K.E.M., F.S., I.B., D.D.B., E.B. and P.J.C.; Formal analysis, R.S.; Investigation, K.E.M., F.S., R.F., M.G., K.J.H., D.P. and R.G. Writing – Original Draft, K.E.M. and P.J.C.; Writing – Review and Editing, all authors; Funding Acquisition, F.S., L.B., B.M.C., D.D.B., E.B. and P.J.C.; Resources, P.L., N.P., C.M.D., L.M.M., B.L.O., A.S. and H.N.; Supervision, F.S., L.B., B.M.C., D.D.B., E.B. and P.J.C.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Huotari J, Helenius A. Endosome maturation. EMBO J. 2011;30:3481–3500. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gallon M, Cullen PJ. Retromer and sorting nexins in endosomal sorting. Biochem Soc Trans. 2015;43:33–47. doi: 10.1042/BST20140290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schreij AM, Fon EA, McPherson PS. Endocytic membrane trafficking and neurodegenerative disease. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2016;73:1529–1545. doi: 10.1007/s00018-015-2105-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Henne WM, Buchkovich NJ, Emr SD. The ESCRT pathway. Dev Cell. 2011;21:77–91. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burd C, Cullen PJ. Retromer: a master conductor of endosome sorting. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2014;6 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a016774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seaman MN, Marcusson EG, Cereghino JL, Emr SD. Endosome to Golgi retrieval of the vacuolar protein sorting receptor, Vps10p, requires the function of the VPS29, VPS30, and VPS35 gene products. J Cell Biol. 1997;137:79–92. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.1.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seaman MN, McCaffery JM, Emr SD. A membrane coat complex essential for endosome-to-Golgi retrograde transport in yeast. J Cell Biol. 1998;142:665–681. doi: 10.1083/jcb.142.3.665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arighi CN, Hartnell LM, Aguilar RC, Haft CR, Bonifacino JS. Role of the mammalian retromer in sorting of the cation-independent mannose 6-phosphate receptor. J Cell Biol. 2004;165:123–133. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200312055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seaman MN. Cargo-selective endosomal sorting for retrieval to the Golgi requires retromer. J Cell Biol. 2004;165:111–122. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200312034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seaman MN. Identification of a novel conserved sorting motif required for retromer-mediated endosome-to-TGN retrieval. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:2378–2389. doi: 10.1242/jcs.009654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Canuel M, Lefrancois S, Zeng J, Morales CR. AP-1 and retromer play opposite roles in the trafficking of sortilin between the Golgi apparatus and the lysosomes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;366:724–730. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harterink M, et al. A SNX3-dependent retromer pathway mediates retrograde transport of the Wnt sorting receptor Wntless and is required for Wnt secretion. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:914–923. doi: 10.1038/ncb2281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang P, Wu Y, Belenkaya TY, Lin X. SNX3 controls Wingless/Wnt secretion through regulating retromer-dependent recycling of Wntless. Cell Res. 2011;21:1677–1690. doi: 10.1038/cr.2011.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lucas M, et al. Structural Mechanism for Cargo Recognition by the Retromer Complex. Cell. 2016;167:1623–1635 e1614. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.10.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lauffer BE, et al. SNX27 mediates PDZ-directed sorting from endosomes to the plasma membrane. J Cell Biol. 2010;190:565–574. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201004060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Temkin P, et al. SNX27 mediates retromer tubule entry and endosome-to-plasma membrane trafficking of signalling receptors. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:715–721. doi: 10.1038/ncb2252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gallon M, et al. A unique PDZ domain and arrestin-like fold interaction reveals mechanistic details of endocytic recycling by SNX27-retromer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1410552111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steinberg F, et al. A global analysis of SNX27-retromer assembly and cargo specificity reveals a function in glucose and metal ion transport. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15:461–471. doi: 10.1038/ncb2721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clairfeuille T, et al. A molecular code for endosomal recycling of phosphorylated cargos by the SNX27-retromer complex. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2016;23:921–932. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harbour ME, Breusegem SY, Seaman MN. Recruitment of the endosomal WASH complex is mediated by the extended ‘tail’ of Fam21 binding to the retromer protein Vps35. Biochem J. 2012;442:209–220. doi: 10.1042/BJ20111761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jia D, Gomez TS, Billadeau DD, Rosen MK. Multiple repeat elements within the FAM21 tail link the WASH actin regulatory complex to the retromer. Mol Biol Cell. 2012;23:2352–2361. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E11-12-1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gomez TS, Billadeau DD. A FAM21-containing WASH complex regulates retromer-dependent sorting. Dev Cell. 2009;17:699–711. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Derivery E, et al. The Arp2/3 activator WASH controls the fission of endosomes through a large multiprotein complex. Dev Cell. 2009;17:712–723. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harbour ME, et al. The cargo-selective retromer complex is a recruiting hub for protein complexes that regulate endosomal tubule dynamics. J Cell Sci. 2010;123:3703–3717. doi: 10.1242/jcs.071472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Puthenveedu MA, et al. Sequence-dependent sorting of recycling proteins by actin-stabilized endosomal microdomains. Cell. 2010;143:761–773. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Steinberg F, Heesom KJ, Bass MD, Cullen PJ. SNX17 protects integrins from degradation by sorting between lysosomal and recycling pathways. J Cell Biol. 2012;197:219–230. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201111121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McMillan KJ, et al. Atypical parkinsonism-associated retromer mutant alters endosomal sorting of specific cargo proteins. J Cell Biol. 2016;214:389–399. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201604057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]