Abstract

Muscle development, growth, and regeneration takes place throughout vertebrate life. In amniotes myogenesis takes place in four successive, temporally distinct, although overlapping phases. Understanding how embryonic, fetal, neonatal, and adult muscle are formed from muscle progenitors and committed myoblasts is an area of active research. In this review we examine recent expression, genetic loss-of-function, and genetic lineage studies that have been conducted in the mouse, with a particular focus on limb myogenesis. We synthesize these studies to present a current model of how embryonic, fetal, neonatal, and adult muscle are formed in the limb.

Keywords: Pax3, Pax7, Myf5, MyoD, Myogenin, Mrf4, myogenesis, muscle regeneration

INTRODUCTION

Muscle development, growth, and regeneration take place throughout vertebrate life. In amniotes myogenesis takes place in successive, temporally distinct, although overlapping phases. Muscle produced during each of these phases is morphologically and functionally different, fulfilling different needs of the animal (reviewed in Biressi et al., 2007a; Stockdale, 1992). Of intense interest is understanding how these different phases of muscle arise. Because differentiated muscle is post-mitotic, muscle is generated from myogenic progenitors and committed myoblasts, which proliferate and differentiate to form muscle. Therefore research has focused on identifying myogenic progenitors and myoblasts and their developmental origin, defining the relationship between different progenitor populations and myoblasts, and determining how these progenitors and myoblasts give rise to different phases of muscle. In this review we will give an overview of recent expression, genetic loss-of-function, and genetic lineage studies that have been conducted in mouse, with particular focus on limb myogenesis, and synthesize these studies to present a current model of how different populations of progenitors and myoblasts give rise to muscle throughout vertebrate life.

MYOGENESIS OVERVIEW

In vertebrates all axial and limb skeletal muscle derives from progenitors originating in the somites (Emerson and Hauschka, 2004). These progenitors arise from the dorsal portion of the somite, the dermomyotome. The limb muscle originates from limb-level somites, and cells delaminate from the ventrolateral lip of the dermomyotome and migrate into the limb, by embryonic day (E) 10.5 (in forelimb, slightly later in hindlimb). Once in the limb these cells proliferate and give rise to two types of cells: muscle or endothelial (Hutcheson et al., 2009; Kardon et al., 2002). Thus the fate of these progenitors only becomes decided once they are in the limb. Those cells destined for a muscle fate then undergo the process of myogenesis. During myogenesis, the progenitors become specified and determined as myoblasts, which in turn differentiate into post-mitotic mononuclear myocytes, and these myocytes fuse to one another to form multinucleated myofibers (Emerson and Hauschka, 2004).

Myogenic progenitors, myoblasts, myocytes, and myofibers critically express either Pax or Myogenic Regulatory Factor (MRF) transcription factors. A multitude of studies have shown that progenitors in the somites and in the limb express the paired domain transcription factors Pax3 and Pax7 (reviewed in Buckingham, 2007). Subsequently, determined myoblasts, myocytes, and myofibers in the somite and in the limb express members of the MRF family of bHLH transcription factors. The MRFs consist of four proteins: Myf5, MyoD, Mrf4 (Myf6), and Myogenin. These factors were originally identified by their in vitro ability to convert 10T1/2 fibroblasts to a myogenic fate (Weintraub et al., 1991). Myf5, MyoD, and Mrf4 are expressed in myoblasts (Biressi et al., 2007b; Kassar-Duchossoy et al., 2005; Ontell et al., 1993a; Ontell et al., 1993b; Ott et al., 1991; Sassoon et al., 1989), while Myogenin is expressed in myocytes (Ontell et al., 1993a; Ontell et al., 1993b; Sassoon et al., 1989). In addition, MyoD, Mrf4, and Myogenin are all expressed in the myonuclei of differentiated myofibers (Bober et al., 1991; Hinterberger et al., 1991; Ontell et al., 1993a; Ontell et al., 1993b; Sassoon et al., 1989; Voytik et al., 1993). Identification of these molecular markers of the different stages of myogenic cells has been essential for reconstructing how myogenesis occurs.

In amniotes there are four successive phases of myogenesis (Biressi et al., 2007a; Stockdale, 1992). In the limb, embryonic myogenesis occurs between E10.5 and 12.5 in mouse and establishes the basic muscle pattern. Fetal (E14.5-P0; P, post natal day) and neonatal (P0–P21) myogenesis are critical for muscle growth and maturation. Adult myogenesis (after P21) is necessary for post-natal growth and repair of damaged muscle. Each one of these phases involves proliferation of progenitors, determination and commitment of progenitors to myoblasts, differentiation of myocytes, and fusion of myocytes into multinucleate myofibers. The progenitors in embryonic and fetal muscle are mononuclear cells lying interstitial to the myofibers. After birth, the neonatal and adult progenitors adopt a unique anatomical position and lie in between the plasmalemma and basement membrane of the adult myofibers and thus are termed satellite cells (Mauro, 1961). During embryonic myogenesis, embryonic myoblasts differentiate into primary fibers, while during fetal myogenesis fetal myoblasts both fuse to primary fibers and fuse to one another to make secondary myofibers. During fetal and neonatal myogenesis, myofiber growth occurs by a rapid increase in myonuclear number, while in the adult myofiber hypertrophy can occur in the absence of myonuclear addition (White et al., 2010).

Embryonic, fetal, and adult myoblasts and myofibers are distinctive. The different myoblast populations were initially identified based on their in vitro characteristics. Embryonic, fetal, and adult myoblasts differ in culture in their appearance, media requirements, response to extrinsic signaling molecules, drug sensitivity, and morphology of myofibers they generate (summarized in Table 1; Biressi et al., 2007a; Stockdale, 1992). Recent microarray studies also demonstrate that embryonic and fetal myoblasts differ substantially in their expression of transcription factors, cell surface receptors, and extracellular matrix proteins (Biressi et al., 2007b). It presently is unclear whether neonatal myoblasts differ substantially from fetal myoblasts. Differentiated primary, secondary, and adult myofibers also differ, primarily in their expression of muscle contractile proteins, including isoforms of myosin heavy chain (MyHC), myosin light chain, troponin, and tropomyosin, as well as metabolic enzymes (MyHC differences are summarized in Table 1; Agbulut et al., 2003; Biressi et al., 2007b; Gunning and Hardeman, 1991; Lu et al., 1999; Rubinstein and Kelly, 2004; Schiaffino and Reggiani, 1996).

Table 1.

Summary of characteristics of embryonic, fetal, and adult myoblasts and myofibers.

| Culture appearance and clonogenicity | Signaling molecule response | Drug sensitivity | Myofiber morphology in culture | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Embryonic myoblasts | Elongated, prone to differentiate and form small colonies, do not spontaneously contract in culture | Differentiation insensitive to TGFβ–1 or BMP4 | Differentiation insensitive to phorbol esters (TPA), sensitive to merocynine 540 | Mononucleated myofibers or myofibers with few nuclei |

| Fetal myoblasts | Triangular, proliferate (to limited extent) in response to growth factors, spontaneously contract in culture | Differentiation blocked by TGFβ–1 and BMP4 | Differentiation sensitive to phorbol esters (TPA) | Large, multinucleated myofibers |

| Satellite cells/Adult myoblasts | Round, clonogenic, but undergo senescence after a limited number of passages, spontaneously contract in culture | Differentiation blocked by TGFβ–1 and BMP4 | Differentiation sensitive to phorbol esters (TPA) | Large, multinucleated myofibers |

| MyHCemb | MyHCperi | MyHCI | MyHCIIa | MyHCIIx | MyHCIIb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Embryonic myofibers | + | − | + | − | − | − |

| Fetal myofibers | + | + | +/− | +/− | +/− | +/− |

| Adult myofibers | − | − | − | + | + | + |

All from Biressi (2007b) or review of Biressi et al. (2007a).

The finding that myogenesis occurs in successive phases and that embryonic, fetal, neonatal, and adult muscle are distinctive raises the question of how these different types of muscle arise. Potentially, these muscle types arise from different progenitors or alternatively from different myoblasts. Another possibility is that the differences in muscle arise during the process of differentiation of myoblasts into myocytes and myofibers. In addition, there is the overlying question of whether differences arise because of intrinsic changes in the myogenic cells or whether changes in the extrinsic environment are regulating myogenic cells.

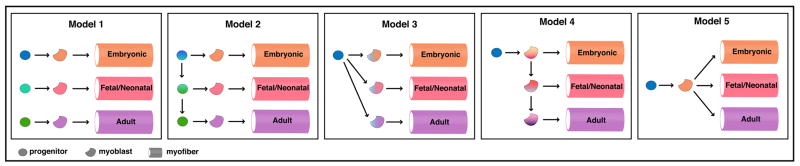

Five theoretical, simplistic models could explain how these different types of muscle arise (Figure 1). In these models, we have combined fetal and neonatal muscle into one group. While embryonic and adult muscle are clearly distinct, the distinction between fetal and neonatal muscle is not so clear. Other than birth of the animal, fetal and neonatal muscle appear not to be discrete, but rather to be a gradually changing population of myogenic cells. In the first theoretical model, three different progenitor populations give rise to three distinct myoblast populations and these myoblasts, in turn, give rise to the different types of muscle. In this model, all differences in muscle could simply reflect initial intrinsic heterogeneities in the original progenitor populations, and it will be critical to understand the mechanisms that generate different types of progenitors. A second model is that all muscle derives from a progenitor population that changes over time to give rise to three different populations of myoblasts, and these different myoblast populations give rise to different types of muscle. In this model, the interesting question is understanding what intrinsic or extrinsic factors regulate changes in the progenitor population. In the third model there is a single invariant progenitor population which gives rise to three initially similar myoblast populations. These myoblast populations change over time such that they give rise to different muscle types. In this scenario, understanding the intrinsic or extrinsic factors that lead to differences in myoblasts will be important. In the fourth model there is a single invariant progenitor population which gives rise to an initial myoblast population. This initial myoblast population both gives rise to embryonic muscle and gives rise to a successive series of myoblast populations. These gradually differing myoblasts then give rise to different types of muscle. Here differences in muscle arise entirely from differences in the myoblast populations, and so it will be critical to ascertain the intrinsic and extrinsic factors altering the myoblasts. In the final model a single invariant progenitor population give rise to a single myoblast population. Subsequently, in the process of myoblast differentiation differences arise so that different muscle types are generated. However, this final model is unlikely to be correct because, as described above, it is well established that different myoblast populations are present and identifiable. It should be noted that a common component of all of these models is the assumption, currently made by most muscle researchers, that progenitors give rise to myoblasts and that myoblasts give rise to differentiated muscle and that this progression is irreversible. In all likelihood, myogenesis is considerably more complex than these five models. We present these models simply as a starting point to evaluate current data.

Figure 1.

Five theoretical models describing derivation of embryonic, fetal/neonatal, and adult limb muscle in mouse.

In this review, we will discuss what is known about the Pax3/7 and MRF family of transcription factors and how these data allow us to construct a model of muscle development. We focus on Pax3 and 7 and the MRFs because these both mark different myogenic populations and are functionally critical for myogenesis. We will limit our discussion to studies conducted in mouse, largely because of the availability of genetic tools available to conduct lineage, cell ablation, and conditional mutagenesis experiments (Hutcheson and Kardon, 2009). In addition, we will concentrate on myogenesis in the limb because all phase of myogenesis – embryonic, fetal/neonatal, and adult – have been studied in the limb. For discussions of myogenic progenitors in other model organisms, such as chick and zebrafish, and in the head and trunk, we refer the reader to several excellent recent reviews (Buckingham and Vincent, 2009; Kang and Krauss, 2010; Otto et al., 2009; Relaix and Marcelle, 2009; Tajbakhsh, 2009)

EXPRESSION ANALYSES OF PAX3/7 AND MRF TRANSCRIPTION FACTORS

Multiple expression studies have established that Pax3 and Pax7 label muscle progenitors (summarized in Table 2). Both Pax3 and Pax7 are initially expressed in the somites. Pax3 is first expressed (beginning at E8) in the presomitic mesoderm as somites form, but is progressively restricted, first to the dermomyotome and later to dorsomedial and ventrolateral dermomyotomal lips (Bober et al., 1994; Goulding et al., 1994; Horst et al., 2006; Schubert et al., 2001; Tajbakhsh and Buckingham, 2000). Pax7 expression initiates later (beginning at E9) in the somites and is expressed in the dermomyotome, with highest levels in the central region of the dermomyotome (Horst et al., 2006; Jostes et al., 1990; Kassar-Duchossoy et al., 2005; Relaix et al., 2004). In the limb, Pax3+ progenitors are transiently present between E10.5 and E12.5 (Bober et al., 1994). Although Pax3 is generally not expressed in association with muscle after E12.5, some adult satellite cells have been reported to express Pax3 (Conboy and Rando, 2002; Relaix et al., 2006). Unlike Pax3 (and unlike in the chick), Pax7+ progenitors are not present in the limb until E11.5 and continue to be present in fetal and neonatal muscle (Relaix et al., 2004). In the adult, Pax7 labels all satellite cells (Seale et al., 2000). Much of this analysis of Pax3 and Pax7 expression has been based on RNA in situ hybridization and immunofluorescence. In addition, a variety reporter alleles (both “knock-ins” and transgenes) have been developed to genetically mark Pax3+ and Pax7+ cells: Pax3IRESnLacZ, Pax3GFP, Pax7LacZ, Pax7nGFP, Pax7nLacZ (Mansouri et al., 1996; Relaix et al., 2003; Relaix et al., 2005; Sambasivan et al., 2009). These alleles have been extremely useful, as they can increase the sensitivity of detection of Pax3+ and Pax7+ cells. Nevertheless, these reporters should be used with care because, as has been often noted, the stability of the reporter does necessarily not match the stability of the endogenous protein. For instance, the Pax3 protein is tightly regulated by ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation (Boutet et al., 2007), and it has been shown that the GFP from the Pax3GFP allele is expressed similarly to Pax3, but perdures longer than the endogenous Pax3 protein (Relaix et al., 2004).

Table 2.

Summary of Pax3, Pax7, Myf5, MyoD, Myogenin, and Mrf4 expression in embryonic, fetal/neonatal, and adult progenitors, myoblasts, and myofibers.

The MRFs are expressed in myoblasts, myocytes, and myofibers in different phases of limb myogenesis (summarized in Table 2). Myf5, MyoD, Mrf4, and Myogenin are all first expressed in somitic cells (Bober et al., 1991; Ott et al., 1991; Sassoon et al., 1989; Tajbakhsh and Buckingham, 2000). However, somitic cells migrating into the limb do not initially express the MRFs (Tajbakhsh and Buckingham, 1994). Myf5 and MyoD are the earliest MRFs expressed in the developing limb. Myf5 is expressed at E10.5 in embryonic myoblasts and continues to be expressed in fetal and adult myoblasts (Biressi et al., 2007b; Cornelison and Wold, 1997; Kassar-Duchossoy et al., 2005; Kuang et al., 2007; Ott et al., 1991). Myf5 is also expressed in many, but not all adult quiescent satellite cells (Beauchamp et al., 2000; Cornelison and Wold, 1997; Kuang et al., 2007). Unlike the other MRFs, Myf5 expression is limited to myoblasts (or adult progenitors), as it is down-regulated in differentiated myogenic cells. MyoD also begins to be expressed in the limb at E10.5 in embryonic myoblasts and myofibers (Ontell et al., 1993a; Sassoon et al., 1989), and subsequently is also expressed in fetal and adult myoblasts and myofibers (Cornelison and Wold, 1997; Hinterberger et al., 1991; Kanisicak et al., 2009; Ontell et al., 1993b; Voytik et al., 1993; Yablonka-Reuveni and Rivera, 1994). Unlike Myf5, MyoD rarely appears to be expressed in quiescent satellite cells (Cornelison and Wold, 1997; Yablonka-Reuveni and Rivera, 1994; Zammit et al., 2002). Myogenin is expressed in the limb by E11.5 5 (Ontell et al., 1993a; Sassoon et al., 1989) and is primarily found in differentiated myocytes and myofibers of embryonic, fetal, and adult muscle (Cornelison and Wold, 1997; Hinterberger et al., 1991; Ontell et al., 1993a; Ontell et al., 1993b; Sassoon et al., 1989; Voytik et al., 1993; Yablonka-Reuveni and Rivera, 1994). Mrf4 is the last MRF to be expressed in the limb. It is first expressed in the limb at E13.5, with stronger expression in fetal myofibers by E16.5, and continues to be expressed as the predominant MRF in adult myofibers (Bober et al., 1991; Gayraud-Morel et al., 2007; Haldar et al., 2008; Hinterberger et al., 1991; Voytik et al., 1993). Similar to Pax3 and Pax7, expression analyses of the MRFs have been facilitated by the generation of reporter alleles Myf5nLacz, Myf5GFP-P, and Mrf4nLacZ-P (Kassar-Duchossoy et al., 2004; Tajbakhsh et al., 1996). These “knock-in” alleles have allowed for increased sensitivity in tracking Myf5+ and Mrf4+ cells. However, these alleles must be used with caution as Myf5 and Mrf4 are genetically linked, and the reporter constructs disrupt the expression of the linked gene to varying degrees (Kassar-Duchossoy et al., 2004).

These expression studies are important both for establishing which myogenic populations are labeled by Pax3, Pax7 and MRF genes and also for describing the temporal-spatial relationship between the expression of these transcription factors and the cell populations they label. Most significantly, these studies are critical for generating testable hypotheses about gene function and cell lineage relationships. In terms of gene function, the expression of Pax3 and Pax7 in progenitors suggests that these genes are important for specification or maintenance of progenitors. The expression of MyoD and Myf5 in myoblasts suggests that these MRFs may be critical for myoblast determination. Finally, the expression of MyoD, Myogenin, and Mrf4 in myocytes or myofibers suggests that these MRFs play a role in differentiation. Thus gene expression studies strongly implicate Pax and MRF as playing roles in myogenesis and are a good starting point for designing appropriate functional experiments. However, as will be described in the following section, gene expression does not necessarily indicate critical gene function. For instance, Pax7 is strongly expressed in adult satellite cells, but is not functionally important for muscle regeneration by satellite cells (Lepper et al., 2009). In terms of lineage, the finding that Pax3 is expressed before Pax7 in muscle progenitors in the limb suggests that Pax3+ cells may give rise to Pax7+ cells. In addition, the demonstration that MRFs are expressed after Pax3 also suggests that Pax3+ cells give rise to MRF+ myoblasts. However, gene expression data is not sufficient to allow us to reconstruct cell lineage. For instance, because Pax3 is only transiently expressed in progenitors, but not in myoblasts or differentiated myogenic cells, it is impossible to trace the fate of these Pax3+ progenitors. Conversely, continuity of gene expression, e.g. the expression of MyoD in both myoblasts and myofibers, does not necessarily indicate continuity of cell lineage because new cells may initiate gene expression de novo while other cells may down-regulate gene expression.

FUNCTIONAL ANALYSIS OF PAX3/7 AND MRF TRANSCRIPTION FACTORS

Mouse genetic loss-of-function studies not only demonstrate that Pax3 is required for limb myogenesis, but also indicate that Pax3+ progenitors are essential to generate all the myogenic cells in the limb (Table 3). Pax3 function has been studied for over 50 years because of the availability of a naturally occurring functional null allele of Pax3, the Splotch mutant (Auerbach, 1954; Epstein et al., 1993). In Pax3Sp Splotch mutants (which generally die by E14.5), as well as other splotch mutants such as Pax3SpD (which die at E18.5), no embryonic or fetal muscle forms in the limb (Bober et al., 1994; Franz et al., 1993; Goulding et al., 1994; Vogan et al., 1993). There is a complete lack of myoblasts, myocytes, and myofibers, as indicated by the lack of expression of MRFs and muscle contractile proteins. Functional Pax3 is required for multiple aspects of somite development and limb myogenesis. In the somite, Pax3 regulates somite segmentation and formation of the dorsomedial and ventrolateral dermomyotome (Relaix et al., 2004; Schubert et al., 2001; Tajbakhsh and Buckingham, 2000). For limb myogenesis, Pax3 is required for maintenance of the ventrolateral somitic precursors, delamination (via activation of Met expression) from the somite of limb myogenic progenitors, migration of progenitors into the limb, and maintenance of progenitor proliferation (Relaix et al., 2004). Interestingly, in the adult conditional deletion of Pax3 in satellite cells revealed that, despite observed expression of Pax3 in satellite cells of some muscles (Relaix et al., 2006), Pax3 is not required for muscle regeneration (Lepper et al., 2009). Together these data show that Pax3 is required for embryonic myogenesis in the limb, but is not subsequently required in the adult. Whether Pax3 is required for fetal limb myogenesis has not been explicitly tested. These functional data also elucidate the nature of the progenitors which give rise to limb muscle. The complete absence of muscle in the limb in Pax3 mutants, in combination with the early transient (E10.5–12.5) expression of Pax3 in limb muscle progenitors, suggests that these early Pax3+ progenitors (present up to E12.5) give rise to all embryonic and fetal myoblasts, myocytes, and myofibers in the limb. This suggests that our theoretical Model 1, in which multiple distinct progenitors give rise to different myoblasts and myofibers, is unlikely to be correct. Instead Models 2–4 (or some variant of them), in which all muscle ultimately derives from one initial progenitor population, are more likely representations of limb myogenesis.

Table 3.

Summary of phenotypes with loss of function in mouse of Pax3, Pax7, Myf5, MyoD, Myogenin, Mrf4, and combinations of Pax3, Pax7 and MRFs. It should be noted that some Myf5 null and Mrf4 null alleles affected the expression of Mrf4 and Myf5, respectively. Thus, for instance, the Myf5nlacZ/nlacZ mice, originally described as Myf5 null mice (Tajbakhsh et al., 1997), are also null for Mrf4 (Kassar-Duchossoy et al., 2004). Only the Myf5loxP/loxP allele leaves Mrf4 intact (Kassar-Duchossoy et al., 2004). In this table phenotypes described for both Myf5 null and compound Myf5 and MyoD null are based on Myf5loxP/loxP mice. Similarly, while three Mrf4 null alleles were generated (Braun and Arnold, 1995; Patapoutian et al., 1995; Zhang et al., 1995), only one Mrf4 null allele leaves Myf5 intact (Olson et al., 1996; Zhang et al., 1995). The phenotype described here for the Mrf4 null is based on this allele from the Olson lab (Zhang et al., 1995).

| Pax3 (Lepper et al., 2009; Relaix et al., 2004 and references therein) |

Pax7 (Kuang et al., 2006; Lepper et al., 2009; Oustanina et al., 2004; Relaix et al., 2006; Seale et al., 2000) |

Pax3/ Pax7 (Relaix et al., 2005) |

Pax3/ Myf5/ Mrf4 (Tajbakhsh et al., 1997) |

Myf5 (Gayraud- Morel et al., 2007; Kassar- Duchossoy et al., 2004) |

MyoD (Gayraud- Morel et al., 2007; Kablar et al., 1997; Megeney et al., 1996; Rudnicki et al., 1992; White et al., 2000; Yablonka- Reuveni et al., 1999) |

Mrf4 (Zhang et al., 1995) |

Myogenin or Myogenin/Myf5 or Myogenin/Myo D or Myogenin/Mrf4 (Hasty et al., 1993; Nabeshima et al., 1993; Rawls et al., 1995; Rawls et al., 1998; Venuti et al., 1995) |

Myf5/ MyoD (Kassar- Duchossoy et al., 2004; Kassar- Duchossoy et al., 2005) |

Myf5/ Mrf4 (Braun and Arnold, 1995; Kassar- Duchossoy et al., 2004; Tajbakhsh et al., 1997) |

MyoD/ Mrf4 (Rawls et al., 1998) |

Myf5/ MyoD/ Mrf4 (Kassar- Duchossoy et al., 2004; Rudnicki et al., 1993) |

MyoD/Mrf4/ Myogenin (Valdez et al., 2000) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Axial | Defects in somite segmentation, epaxial and hypaxial dermo-myotome, trunk muscle | No phenotype observed | Only form primary myotome. No embryonic or fetal axial muscle. | Defective primary myotome. No embryonic or fetal axial muscle | Delay of primary myotome formation, lack of some epaxial muscles in adult. | Normal primary myotome and epaxial muscles, delay in hypaxial muscles | No phenotype observed | Embryonic axial muscle normal, no MyHCperi+ fetal axial muscle | Delay of primary myotome, embryonic axial muscle at E12.5, no fetal axial muscle | Delayed primary myotome, lack of some epaxial muscle | Embryonic axial muscle normal, no axial fetal muscle | No myotome or axial muscle | Only Myf5+ myoblasts, no myofibers |

| Embryonic Limb E11.5–E14.5 | No limb muscle due to defects in delamination, migration, maintenance of limb progenitors | No phenotype observed | No limb muscle (see Pax3 phenotype) | No limb muscle (see Pax3 phenotype) | No phenotype observed | 2.5 day delay in limb myogenesis, no limb muscle until E13.5 | No phenotype observed | Normal embryonic limb myoblasts and MyHCemb+ myofibers | No limb muscle at E12.5 (MyoD phenotype), a few myofibers at E14.5 | No phenotype observed | Normal embryonic limb myoblasts and myofibers | No limb muscle | Not explicitly tested |

| Fetal Limb E14.5–E18.5 | No limb muscle (see above) | No phenotype observed | No limb muscle (see Pax3 phenotype) | No limb muscle (see Pax3 phenotype) | No phenotype observed | No phenotype observed | No phenotype observed | No MyHCperi+ fetal limb myofibers, a few residual myofibers, myoblasts present | Few myofibers at E14.5, no fetal myofibers by birth | No phenotype observed | Myoblasts present, but few residual myofibers | No limb muscle | No differentiated myofibers, no MyHCemb |

| Neonatal Limb P0–P21 | Dead | Defects in satellite cell survival, proliferation, and differentiation (as tested by conditional deletion) | Dead | Dead | No phenotype observed | No phenotype observed | No phenotype observed | Few residual myofibers, perinatal death | No muscle at birth, perinatal death | No phenotype observed, perinatal death | Few residual myofibers, perinatal death | No limb muscle, perinatal death | No differentiated myofibers, no MyHCemb, perinatal death |

| Adult/Regeneration | Dead (Pax3 null mice) Not required (as tested by conditional deletion) | No effect on adult muscle regeneration (as tested by conditional deletion) | Dead | Dead | Impaired regeneration with delayed differentiation, fiber hypertrophy, increased fat and fibrosis | Delayed and impaired regeneration with increased number of satellite cells and fewer differentiated myofibers | Not explicitly tested | Dead | Dead | Dead | Dead | Dead | Dead |

Functional analysis of Pax7 has established that Pax7 regulates neonatal progenitors and also reveals that there are at least two genetically distinct populations of progenitors (Table 3). Analysis of Pax7 loss-of-function alleles has been complicated. Although no muscle phenotypes were initially recognized in null Pax7LacZ/LacZ (Mansouri et al., 1996), subsequent analysis suggested that no satellite cells were specified in the absence of Pax7 (Seale et al., 2000). Then a series of papers (Kuang et al., 2006; Oustanina et al., 2004; Relaix et al., 2006) determined that, in fact, satellite cells were present in Pax7 null mice. However, Pax7 was found to be critical for maintenance, proliferation, and function of satellite cells. More recently, conditional deletion of Pax7 in satellite cells, via a tamoxifen-inducible Pax7CreERT2 allele and a Pax7fl allele, has surprisingly shown that Pax7 is not required after P21 (the end of neonatal myogenesis) for effective muscle regeneration (Lepper et al., 2009). However, consistent with the previous studies (Kuang et al., 2006; Oustanina et al., 2004; Relaix et al., 2006), conditional deletion of Pax7 between P0 and P21 did show a requirement for Pax7 in neonatal satellite cells for proper proliferation and myogenic differentiation (Lepper et al., 2009). Thus, this study demonstrates that Pax7 is dispensable in the adult, but required in neonatal satellite cells for their maintenance, proliferation, and differentiation. Prior to birth, myogenesis appears not to require Pax7, as gross muscle morphology is normal (Oustanina et al., 2004; Seale et al., 2000). However, the reduced number of satellite cells just after birth (Oustanina et al., 2004; Relaix et al., 2006) suggests that proliferation and/or maintenance of fetal progenitors may be functionally dependent on Pax7. In total, these functional studies reveal that there are at least two populations of progenitors: Pax7-functionally dependent neonatal satellite cells and Pax7-functionally independent adult satellite cells. Thus a model of myogenesis in which there is only one invariant progenitor population (as seen in Models 3, 4, and 5) is unlikely to be correct.

Compound mutants of Myf5, MyoD, and Mrf4 demonstrate that embryonic and fetal myoblasts have different genetic requirements for their determination (Table 3). Over the past twenty years, multiple loss-of-function alleles of all four MRFs have been generated and allowed for detailed characterization of their function. However, analysis of Myf5 and Mrf4 function has been complicated because these two genes are genetically linked, and so many of the original Myf5 and Mrf4 loss-of-function alleles also affected the expression of the neighboring gene (see discussion in Kassar-Duchossoy et al., 2004; Olson et al., 1996).

Single loss-of-function mutants of Myf5 or Mrf4 (in which genetically linked Mrf4 and Myf5 expression remain intact) show no defects in embryonic or fetal limb myogenesis (Kassar-Duchossoy et al., 2004; Zhang et al., 1995), and MyoD mutants have only a minor phenotype, a 2–2.5 day delay in embryonic limb myogenesis (Kablar et al., 1997; Rudnicki et al., 1992). Compound Myf5 and Mrf4 null mutants have normal embryonic and fetal limb muscle (Braun and Arnold, 1995; Kassar-Duchossoy et al., 2004; Tajbakhsh et al., 1997). Compound MyoD and Mrf4 mutants (in which Myf5 expression remains intact) have normal embryonic myoblasts and myofibers (but with a 2 day delay in development, reflecting the MyoD null phenotype) and fetal myoblasts (although fetal myofibers are absent, see below; Rawls et al., 1998). Compound Myf5 and MyoD loss-of-function mutants (in which Mrf4 expression is intact) contain no fetal myoblasts or myofibers. However, a few residual embryonic myofibers are present and therefore indicate the presence of some embryonic myoblasts (Kassar-Duchossoy et al., 2004). In triple Myf5, MyoD, and Mrf4 loss-of-function mutants, no embryonic or fetal myoblasts or myofibers are present (Kassar-Duchossoy et al., 2004; Rudnicki et al., 1993). Together these genetic data indicate that embryonic myoblasts require either Myf5, MyoD, or Mrf4 for their determination, although these MRFs differ somewhat in their function. MyoD can most efficiently determine embryonic myoblasts, as embryonic myogenesis is normal in compound Myf5 and Mrf4 mutants. While Myf5 can determine embryonic myoblasts, the inability of Myf5 to act as a differentiation factor leads to a delay in limb myogenesis in compound MyoD and Mrf4 mutants. Mrf4 can only poorly substitute for Myf5 or MyoD as a determination factor, and so in the absence of Myf5 and MyoD, limb embryonic myogenesis is only partially rescued by Mrf4. Unlike embryonic myoblasts, fetal myoblasts require either Myf5 or MyoD for their determination, and Mrf4 is not able to rescue this function. These data argue that embryonic and fetal myoblasts have different genetic requirements for their determination, and therefore concurs with previous culture data showing that that embryonic and fetal myoblasts are distinct. The presence of at least two classes of myoblasts therefore excludes Model 5, in which one myoblast population gives rise to different types of myofibers, and argues in favor of Models 1–4, in which multiple myoblast populations are important for generating different types of myofibers. It is likely that embryonic, fetal, and adult myoblasts are distinct populations. However, the genetic requirements of adult myoblasts has not been completely tested. Loss of either Myf5 or MyoD leads to delayed or impaired muscle regeneration (Gayraud-Morel et al., 2007; Megeney et al., 1996; White et al., 2000; Yablonka-Reuveni et al., 1999). The role of Mrf4 in regeneration has not been explicitly tested, although the lack of Mrf4 expression in adult myoblasts suggests Mrf4 may not be required (Gayraud-Morel et al., 2007). To test whether Myf5, MyoD, or Mrf4 may be acting redundantly in the adult will require conditional deletion of these MRFs in adult progenitors since compound mutants die at birth.

Compound mutants of MyoD, Mrf4, and Myogenin reveal that embryonic and fetal myoblasts have different genetic requirements for their differentiation (Table 3). Loss of Mrf4 results in no muscle phenotype in the limbs, while loss of MyoD results in only a delay in embryonic limb myogenesis (Kablar et al., 1997; Rudnicki et al., 1992; Zhang et al., 1995). Formation of embryonic myofibers (MyHCemb+) is largely unaffected with loss of Myogenin (although myosin levels appear lower and myofibers are less organized); however differentiation of fetal myofibers (MyHCperi+) is completely impaired (Hasty et al., 1993; Nabeshima et al., 1993; Venuti et al., 1995). This lack of fetal muscle is due to a defect in differentiation in vivo; myoblasts are still present in Myogenin mutant limbs and can differentiate in vitro (Nabeshima et al., 1993). A similar phenotype is seen in compound Myogenin/MyoD, Myogenin/Mrf4, Myogenin/Myf5, and Mrf4/MyoD null mutants. In all of these mutants, embryonic muscle differentiates, but fetal muscle does not (Rawls et al., 1995; Rawls et al., 1998; Valdez et al., 2000). Also, myoblasts from these compound mutants are present and in vitro can differentiate. In triple Myogenin/Mrf4/MyoD animals, no embryonic or fetal myofibers differentiate and myoblasts from these animals can not differentiate in vitro (Valdez et al., 2000). Together these genetic data argue that differentiation of embryonic myofibers requires either Myogenin, MyoD, or Mrf4. Myf5, which is not normally expressed in differentiating myogenic cells, is not sufficient to support myofiber differentiation. The genetic requirement of fetal myofiber differentiation is more stringent and requires Myogenin and either Mrf4 or MyoD. Thus the differentiation of embryonic and fetal myofibers has different genetic requirements and argues that the embryonic and fetal myoblasts (from which the myofibers derive) are genetically different. Therefore these data support Models 1–4, in which different embryonic and fetal myoblast populations are important for the generation of embryonic and fetal myofibers.

CRE-MEDIATED LINEAGE AND ABLATION ANALYSES OF PAX3, PAX7, AND MRF+ CELLS

Cre-mediated lineage analysis in mice has provided the most direct method to test the lineage relationship of progenitors and myoblasts giving rise to embryonic, fetal, neonatal, and adult muscle. These lineage studies have been enabled by the development of Cre/loxP technology (Branda and Dymecki, 2004; Hutcheson and Kardon, 2009). To genetically label and manipulate different populations of muscle progenitors or myoblasts, Cre lines have been created in which Cre is placed under the control of the promoter/enhancers sequences of Pax3/7 or MRFs. Several strategies have been used to create these Cre lines. For Pax3Cre, Myf5Cre, and MyoDCre lines, Cre has been placed into the ATG of the endogenous locus (Engleka et al., 2005; Kanisicak et al., 2009; Tallquist et al., 2000). For Pax7Cre, Mrf4Cre, and another Myf5Cre line an IRESCre cassette was placed at the transcriptional stop (Haldar et al., 2008; Keller et al., 2004). MyogeninCre was created as a transgene, by placing Cre under the control of a 1.5kb Myogenin promoter and a 1 kb MEF2C enhancer (Li et al., 2005). Recently, tamoxifen-inducible Cre alleles have also been created, and these CreERT2 alleles allow for temporal control of labeling and manipulation because Cre-mediated recombination only occurs after the delivery of tamoxifen. A tamoxifen-inducible Pax7CreERT2 allele has been created by placing a CreERT2 cassette into the ATG of Pax7 (Lepper et al., 2009; Lepper and Fan, 2010). For each of these alleles, the ability to label and manipulate the appropriate cell requires that the Cre be faithfully expressed wherever the endogenous gene is expressed. Placing the Cre or CreERT2 cassette at the endogenous ATG is the most likely strategy for ensuring that Cre expression recapitulates endogenous gene expression. However, these alleles are all “knock-in/knock-out” alleles in which the Cre disrupts expression of the targeted genes. If there is any potential issue of haplo-insufficiency, such a targeting strategy may be problematic. For the Pax3Cre, Myf5Cre, and MyoDCre lines, haplo-insufficiency has not been found to be an issue. For Cre alleles generated by targeted IRESCre to the stop or by transgenics, the fidelity of the Cre needs to be carefully verified. The advantage of such Cre lines, of course, is that the endogenous gene remains intact.

To follow the genetic lineage of the Pax3+, Pax7+, or MRF+ cells, these Cre lines have been crossed to various Cre-responsive reporter mice. In the reporter mice, reporters such as LacZ or YFP are placed under the control a ubiquitous promoter. In the absence of Cre, these reporters are not expressed because of the presence of a strong transcriptional stop cassette flanked by loxP sites, while the presence of Cre causes recombination of the loxP sites and the permanent expression of the reporter. Therefore in mice containing both the Cre and the reporter, cells expressing the Cre and their progeny permanently express the reporter, thus allowing the fate of Pax3+, Pax7+, or MRF+ cells to be followed. The number of cells genetically labeled in response to Cre can be dramatically affected by the reporter lines used, and the utility of each reporter must be verified for each tissue and age of animal being tested. The R26RLacZ and R26RYFP reporters (Soriano, 1999; Srinivas et al., 2001) are commonly used with good success in the embryo to label myogenic cells. In the adult, the endogenous R26R locus may not be sufficient to drive high levels of reporter expression, and so reporters such as R26RmTmG (Muzumdar et al., 2007) or R26RNZG (Yamamoto et al., 2009) in which a CMV β-actin enhancer promoter additionally drives reporter expression, may be necessary.

The Cre/loxP system can also be used to test the requirement of particular cell populations for myogenesis, by crossing Cre lines with Cre-responsive ablater lines (Hutcheson and Kardon, 2009). In these ablater lines, Cre activates the expression of cell-death-inducing toxins, such as diptheria toxin (Brockschnieder et al., 2006; Wu et al., 2006). The lack of receptor for diphteria toxin in mice and the expression of only the diptheria toxin fragment A (DTA, which can not be transferred to other cells without the diptheria toxin fragment B) ensures that only cells expressing Cre, and therefore DTA, will be cell-autonomously killed. Analogous to gene loss-of-function experiments, cell ablation experiments enable the researcher to test the necessity of particular genetically-labeled progenitors and myoblasts for myogenesis.

The expression and functional studies of Pax3 strongly suggested that Pax3+ progenitors give rise to all embryonic, fetal, neonatal, and adult muscle. Particularly because Pax3 is only transiently expressed in progenitors in the early limb bud, tracing the lineage of Pax3+ progenitors required that the cells be genetically labeled via Pax3Cre. These Pax3 lineage studies reveal that Pax3+ cells entering the limb are initially bipotential and able to give rise to both endothelial cells and muscle (Hutcheson et al., 2009). Moreover, Pax3+ cells give rise to all embryonic, fetal, and adult myoblasts and myofibers (Engleka et al., 2005; Hutcheson et al., 2009; Schienda et al., 2006). Thus these early Pax3+ progenitors give rise to all limb muscle and excludes Model 1 of limb myogenesis, in which multiple distinct progenitors give rise to embryonic, fetal, neonatal, and adult myofibers. Of course, it is formally possible that the Pax3+ cells migrating into the limb are a heterogeneous population in which subpopulations give rise to embryonic, fetal, and adult myoblasts (and so Model 1 might be correct). However, to test this possibility early markers of these subpopulations would be required. The necessity of Pax3+ progenitors is demonstrated by the lack of any embryonic or fetal muscle when these cells are genetically ablated (Hutcheson et al., 2009). Although not formally demonstrated (because of the P0 death of Pax3Cre/+;R26RDTA mice), it is likely that the Pax3+ progenitors are also required for the formation of all adult limb muscle. In addition, these lineage studies demonstrated that all Pax7+ progenitors in the embryo and Pax7+ satellite cells in the adult are derived from the Pax3+ progenitors (Hutcheson et al., 2009; Schienda et al., 2006). This finding thus supports Model 2 of limb myogenesis, in which an initial progenitor population gives rise to other progenitor populations.

Genetic lineage studies of Pax7+ progenitors have established that, unlike Pax3+ progenitors, Pax7+ progenitors in the limb are restricted to a myogenic fate (Hutcheson et al., 2009; Lepper and Fan, 2010). Consistent with the later expression of Pax7 (beginning at E11.5), Pax7+ progenitors do not give rise to embryonic muscle, but do give rise to all fetal and adult myoblasts and myofibers in the limb (Hutcheson et al., 2009; Lepper and Fan, 2010). Pax7+ cells labeled in the early limb (via tamoxifen delivery to E11.5 Pax7CreERT2/+;R26RLacZ/+ mice) also give rise to Pax7+ adult satellite cells, although it is unclear whether these labeled cells directly become satellite cells or whether their progeny give rise to satellite cells (Lepper and Fan, 2010). The loss of fetal limb muscle when Pax7+ cells are genetically ablated demonstrates that these Pax7+ progenitors are required for fetal myogenesis in the limb (Hutcheson et al., 2009). The test of whether Pax7+ progenitors are necessary for adult myogenesis awaits the generation of Pax7CreERT2/+;R26RDTA/+ mice, in which Pax7+ progenitors are genetically ablated after birth.

Recent lineage analyses of Myf5+ and MyoD+ cells have unexpectedly revealed that two populations of myoblasts may give rise to muscle. Analysis of Myf5 lineage, using two different Myf5Cre lines, shows that Myf5+ cells are not restricted to a muscle fate, as cells in the axial skeleton and ribs are derived from Myf5+ cells (Gensch et al., 2008; Haldar et al., 2008). This likely reflects early transient expression of Myf5 in the presomitic mesoderm. In contrast, MyoD+ cells appear to be restricted to a muscle fate (Kanisicak et al., 2009). Interestingly, analysis of the Myf5 lineage shows that Myf5+ cells give rise to many, but not all embryonic, fetal, and adult myofibers (Gensch et al., 2008; Haldar et al., 2008). The distribution of Myf5-derived myofibers appears to be stochastic, as epaxial and hypaxial, slow and fast, and different anatomical muscles are randomly Myf5-derived. Unlike Myf5, analysis of MyoD lineage reveals that MyoD+ cells give rise to all embryonic and adult myofibers (fetal myofibers were not explicitly examined; Kanisicak et al., 2009). Consistent with these lineage studies, ablation of Myf5+ cells did not lead to any dramatic defects in embryonic or fetal muscle (the Myf5CreERT2/+;R26RDTA/+ mice die at birth from rib defects), as presumably Myf5-myoblasts compensated for the loss of Myf5+ myoblasts (Gensch et al., 2008; Haldar et al., 2008). Ablation of the MyoD lineage has not yet been published, but based on the lineage studies a complete loss of muscle would be expected. Together, these lineage and ablation studies argue that there are at least two populations of myoblasts, one Myf5-dependent and one Myf5-independent, thus excluding Model 5, in which only one myoblast population generates all limb muscle. It is not yet clear whether there may, in fact, be three populations of myoblasts: Myf5+MyoD−, Myf5+MyoD+, and Myf5−MyoD+. The finding that all muscle is MyoD-derived would suggest that there are no myoblasts that are Myf5+MyoD−. However, because MyoD is strongly expressed in embryonic and fetal myofibers, the finding that all muscle is YFP+ in MyoDCre/+;R26RYFP/+ mice may simply reflect MyoD expression in all myofibers, and not MyoD expression in all myoblasts. Another question yet to be resolved is whether multiple myoblast populations are present during embryonic, fetal, and neonatal myogenesis.

Analysis of the Myf5 and MyoD lineages has also revealed interesting insights about adult satellite cells. The great majority of quiescent satellite cells have been shown to be YFP labeled in Myf5Cre/+;R26RYFP/+ mice (Kuang et al., 2007). Given that most quiescent satellite cells express Myf5 (Beauchamp et al., 2000; Cornelison and Wold, 1997), it is likely that the Myf5 lineage in satellite cells is simply reflecting active Myf5 transcription in satellite cells. However, the finding that all quiescent satellite cells are YFP labeled in MyoDCre/+;R26RYFP/+ mice was quite surprising (Kanisicak et al., 2009). Multiple studies have shown that quiescent satellite cells do not express MyoD, although activated satellite cells do express MyoD (Cornelison and Wold, 1997; Yablonka-Reuveni and Rivera, 1994). Thus the finding that quiescent satellite cells are YFP+ in MyoDCre/+;R26RYFP/+ mice suggests that all quiescent satellite cells are derived from previously activated, MyoD+ satellite cells (as suggested by Zammit et al., 2004). Alternatively, all quiescent satellite cells may be derived from MyoD+ myoblasts. To definitively test whether satellite cells indeed are derived from MyoD+ myoblasts, MyoDCreERT2/+;R26RYFP/+ mice will need to be induced with tamoxifen in the embryo or fetus, before satellite cells are present. It will also be interesting to test using Myf5CreERT2/+;R26RYFP/+ mice whether Myf5+ myoblasts in the embryo or fetus give rise to satellite cells. Such a finding that MyoD+ or Myf5+ myoblasts give rise to satellite cells would profoundly change current models of myogenesis (excluding all five Models presented) because this would demonstrate that myoblasts can return to a more progenitor-like state.

Lineage analysis using MyogeninCre and Mrf4Cre mice demonstrates that by birth all myofibers have expressed both Myogenin and Mrf4 (Gensch et al., 2008; Haldar et al., 2008; Li et al., 2005). A closer examination of the Myogenin lineage reveals that all embryonic and fetal muscle has derived from Myogenin+ myocyctes and/or myofibers (Gensch et al., 2008; Li et al., 2005). It would be worthwhile to similarly determine to what extent embryonic muscle has expressed Mrf4 since expression studies have found Mrf4 to be expressed in at least some embryonic limb muscle (Hinterberger et al., 1991). Consistent with the finding that all fetal muscle has expressed Myogenin and Mrf4, ablation of Myogenin+ or Mrf4+ cells leads to a complete loss of all muscle by birth (Gensch et al., 2008; Haldar et al., 2008).

MOLECULAR SIGNALS DISTINGUISHING BETWEEN DIFFERENT PHASES OF MYOGENESIS

Layered on top of these expression, functional, and lineage studies concentrating on Pax3, Pax7, and MRFs, are functional studies demonstrating that embryonic, fetal, and adult myogenic cells show differential sensitivity to signaling molecules. Recent microarray studies demonstrated that members of the Notch, FGF, and PDGF signaling pathways are differentially expressed in embryonic versus fetal myoblasts (Biressi et al., 2007b). In addition, fetal myoblasts show up-regulation of components of the TGFβ and BMP signaling pathways compared to embryonic myoblasts (Biressi et al., 2007b). Such findings are consistent with in vitro studies demonstrating that embryonic myoblast differentiation is insensitive to treatment with TGFβ or BMP, while fetal myoblast differentiation is blocked in the presence of TGFβ or BMP (Biressi et al., 2007b; Cusella-De Angelis et al., 1994). Interestingly, studies examining adult myogenesis also demonstrate that BMP signaling is active in activated satellite cells and proliferating myoblasts (Ono et al., 2010). Furthermore, inhibition of BMP signaling results in an increase in differentiated myocytes at the expense of proliferating myoblasts in vitro and smaller diameter regenerating myofibers in vivo (Ono et al., 2010). Therefore, in mouse TGFβ and BMP signaling appear to have no effect on embryonic myoblasts, whereas they inhibit differentiation of both fetal and adult myoblasts. Thus, with respect TGFβ and BMP signaling, fetal and adult myoblasts behave similarly. It is interesting to note that in the chick limb BMP signaling has also been shown to differentially regulate embryonic versus fetal and adult myogenesis, although BMP effects were different from those found in the mouse (Wang et al., 2010).

The Wnt/β-catenin pathway also differentially regulates embryonic versus fetal and adult myogenesis. The role of β-catenin in embryonic and fetal myogenesis was tested by conditionally inactivating or activating β-catenin in embryonic muscle via Pax3Cre or in fetal muscle via Pax7Cre (Hutcheson et al., 2009). After myogenic cells enter the limb, embryonic myogenic cells were found to be insensitive to perturbations in β-catenin. However, during fetal myogenesis β-catenin critically determines the number of Pax7+ progenitors and the number and fiber type of myofibers. β-catenin has also been found to positively regulate the number of Pax7+ satellite cells in the adult (Otto et al., 2008; Perez-Ruiz et al., 2008; but see Brack et al., 2008). Thus similar to the findings for TGFβ and BMP signaling, embryonic myogenesis is insensitive to β-catenin signaling, while fetal and adult myogenesis is regulated by β-catenin.

These studies demonstrate that during embryonic myogenesis Pax3+ progenitors are insensitive to TGFβ, BMP, and Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Yet during fetal and adult myogenesis, TGFβ, BMP, and Wnt/β-catenin signaling are important for positively regulating and maintaining the population of Pax7+ progenitors. During development, post-mitotic myofibers must differentiate, while proliferating progenitors must be maintained for growth. Therefore, in the same environment some progenitors must differentiate, while others must continue to proliferate. It has been hypothesized that embryonic, fetal, and adult progenitors and/or myoblasts are intrinsically different so that these cells will respond differently to similar environmental signals (Biressi et al., 2007a; Biressi et al., 2007b). Thus, differential sensitivity to TGFβ, BMP, and Wnt/β-catenin signaling may be a molecular mechanism to allow embryonic progenitors to differentiate, but maintain a fetal and adult progenitor population.

The above examples demonstrate that embryonic, fetal, and adult myogenesis are differentially regulated by different signaling pathways. Until recently, what signals regulate the transitions from embryonic to fetal, neonatal, and adult myogenesis have been unknown. The expression of Pax7 in progenitors demarcates progenitors as being fetal/neonatal/adult progenitors, as opposed to Pax3+ embryonic progenitors. Now elegant in vitro and in vivo studies demonstrate that that the transcription Nfix is expressed in fetal and not embryonic myoblasts, and Pax7 directly binds and activates the expression Nfix (Messina et al., 2010). Moreover, Nfix is critical for regulating the transition from embryonic to fetal myogenesis. Nfix both represses genes highly expressed in embryonic muscle, such as MyHCI, and activates the expression of fetal-specific genes, such as α7-integrin, β-enolase, muscle creatine kinase, and muscle sarcomeric proteins. Thus Nfix functions as an intrinsic transcriptional switch which mediates the transition from embryonic to fetal myogenesis. Recent studies have also demonstrated that extrinsic signals from the connective tissue niche, within which muscle resides, are also important for regulating muscle maturation (Mathew et al., in press). The connective tissue promotes the switch from the fetal to adult muscle by repressing developmental isoforms of myosin and promoting formation of large, multinucleate myofibers. Determining the full range of intrinsic and extrinsic factors that regulate the transitions from embryonic to fetal, neonatal, and adult myogenesis will be important areas for future research.

CURRENT MODEL OF MYOGENESIS

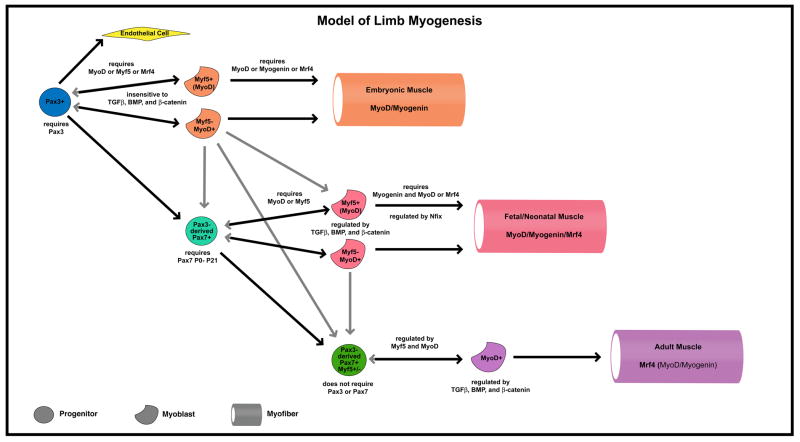

From these expression, functional, and lineage studies, a current model of myogenesis in the limb emerges that is a variant of our theoretical Models 2 and 4 (Figure 2). Embryonic, fetal, neonatal, and adult muscle derive from three related, but distinct populations of progenitors. From the somite, Pax3+ progenitors migrate into the limb and are bipotential, giving rise to either endothelial cells or muscle. Myogenic Pax3+ cells require Pax3 function for their delamination from the somites, migration, and maintenance. Pax3+ cells give rise to and are required for embryonic myogenesis. In addition, Pax3+ cells give rise to Pax7+ progenitors. In turn, these Pax3-derived, Pax7+ progenitors give rise to and are required for fetal myogenesis. These Pax7+ progenitors also appear to give rise to neonatal muscle, but whether the fetal and neonatal progenitors are exactly the same population is unclear. Unlike fetal Pax7+ progenitors, neonatal Pax7+ progenitors may reside underneath the basal lamina of myofibers, similar to satellite cells. Also, while it has been shown that neonatal Pax7+ cells require Pax7 for their maintenance and proper function, it has not been explicitly tested whether fetal Pax7+ cells require Pax7. Adult muscle derives from Pax7+ progenitors, satellite cells, which reside under the myofiber basal lamina. Unlike Pax7+ neonatal progenitors, Pax7+ satellite cells do not require Pax7 for their maintenance and function. Also, the great majority of quiescent Pax7+ satellite cells express Myf5. Pax7+ satellite cells are likely to directly derive from fetal or neonatal Pax7+ progenitors. However, the finding that all quiescent Pax7+ satellite cells have expressed MyoD in their lineage suggests that satellite cells may derive indirectly from Pax7+ fetal or neonatal myogenic progenitors via MyoD+ (or potentially Myf5+) myoblasts (gray arrows in Figure 2). Also, some Pax7+ satellite cells may derive from adult myoblasts, generated by activated Pax7+ satellite cells. Both scenarios would suggest that the progression from progenitor to myoblasts may not be irreversible, and myoblasts may give rise to Pax7+ progenitors.

Figure 2.

Summary of current model of embryonic, fetal/neonatal, and adult limb myogenesis in the mouse.

There are multiple distinct populations of myoblasts that give rise to embryonic, fetal/neonatal, and adult muscle. Embryonic myoblasts are distinct from fetal/neonatal myoblasts. Embryonic limb myoblasts require either MyoD, Myf5, or Mrf4 for their determination, while fetal myoblasts require either MyoD or Myf5 (Mrf4 can not support fetal myoblasts). Adult myoblast function is regulated by Myf5 and MyoD, but whether Myf5 and MyoD are required has not been formally tested. Within embryonic and fetal myoblasts there appear to be at least two subpopulations, Myf5-independent and Myf5-dependent. Differentiation of embryonic and fetal myoblasts into differentiated myocytes and myofibers is differentially regulated by MRFs and signaling. Embryonic myoblasts require either MyoD, Myogenin, or Mrf4 for their differentiation, while fetal myoblasts require Myogenin and Mrf4 or MyoD. Also, while embryonic myogenesis is insensitive to TGFβ, BMP, and β-catenin signaling, fetal myogenesis is regulated by these signaling pathways. The expression of Nfix within fetal myoblasts is critical for their differentiation into fetal myofibers. Once differentiated, embryonic, fetal/neonatal, and adult myofibers express different combinations of MRFs, muscle contractile proteins (including MyHC isoforms), and metabolic enzymes.

From this model, it is clear that amniote myogenesis is complex. Multiple related, although distinct progenitor and myoblast populations give rise to embryonic, fetal, neonatal, and adult muscle. In the future, it will be important to resolve the relationships between myogenic progenitors and myoblasts and definitively answer whether myoblasts ever give rise to progenitors. Also, the extrinsic cell populations and molecular signals differentially regulating the different phases of myogenesis are largely unknown. Finally, a critical question is the identification of the intrinsic and extrinsic factors that maintain the populations of myogenic progenitors, particularly in the embryo and fetus where progenitors reside alongside actively differentiating myogenic cells.

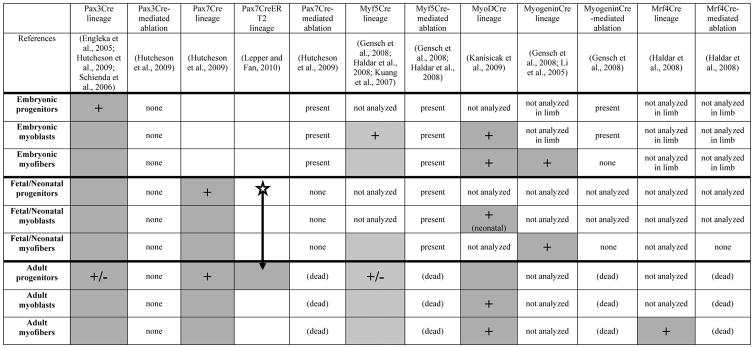

Table 4.

Summary of genetic lineage and ablation studies in mouse. “+” show cells actively transcribing the gene of interest (e.g. transcribing Pax3). Gray boxes denote progenitors, myoblasts and myofibers entirely derived from the genetically labeled cell population (e.g. Pax3+ cells). Hatched boxes show progenitors, myoblasts, and myofibers where only some of the cells are derived from the genetically labeled cell population. Star denotes timing of tamoxifen delivery in Pax7CreERT2 mice.

Engleka, K.A., Gitler, A.D., Zhang, M., Zhou, D.D., High, F.A., and Epstein, J.A. (2005). Insertion of Cre into the Pax3 locus creates a new allele of Splotch and identifies unexpected Pax3 derivatives. Dev Biol 280, 396–406.

Gensch, N., Borchardt, T., Schneider, A., Riethmacher, D., and Braun, T. (2008). Different autonomous myogenic cell populations revealed by ablation of Myf5-expressing cells during mouse embryogenesis. Development 135, 1597–1604.

Haldar, M., Karan, G., Tvrdik, P., and Capecchi, M.R. (2008). Two cell lineages, myf5 and myf5-independent, participate in mouse skeletal myogenesis. Dev Cell 14, 437–445.

Hutcheson, D.A., Zhao, J., Merrell, A., Haldar, M., and Kardon, G. (2009). Embryonic and fetal limb myogenic cells are derived from developmentally distinct progenitors and have different requirements for beta-catenin. Genes Dev 23, 997–1013.

Kanisicak, O., Mendez, J.J., Yamamoto, S., Yamamoto, M., and Goldhamer, D.J. (2009). Progenitors of skeletal muscle satellite cells express the muscle determination gene, MyoD. Dev Biol 332, 131–141.

Kuang, S., Kuroda, K., Le Grand, F., and Rudnicki, M.A. (2007). Asymmetric self-renewal and commitment of satellite stem cells in muscle. Cell 129, 999–1010.

Lepper, C., and Fan, C.M. (2010). Inducible lineage tracing of Pax7-descendant cells reveals embryonic origin of adult satellite cells. genesis 48, 424–436.

Li, S., Czubryt, M.P., McAnally, J., Bassel-Duby, R., Richardson, J.A., Wiebel, F.F., Nordheim, A., and Olson, E.N. (2005). Requirement for serum response factor for skeletal muscle growth and maturation revealed by tissue-specific gene deletion in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102, 1082–1087.

Schienda, J., Engleka, K.A., Jun, S., Hansen, M.S., Epstein, J.A., Tabin, C.J., Kunkel, L.M., and Kardon, G. (2006). Somitic origin of limb muscle satellite and side population cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103, 945–950.

Acknowledgments

We thank DD Cornelison, D Goldhamer, F Relaix, and S Tajbakhsh for discussion and review of the manuscript. We also thank members of the Kardon lab (particularly DA Hutcheson), S Biressi, and G Messina for many helpful discussions. Research in the Kardon lab is supported by the Pew Foundation, MDA, and NIH R01 HD053728.

Contributor Information

Malea Murphy, Department of Human Genetics, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT, 801 585-7365 ph, 801 581-7796 fax.

Gabrielle Kardon, Department of Human Genetics, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT, 801 585-6184, 801 581-7796 fax.

References

- Agbulut O, Noirez P, Beaumont F, Butler-Browne G. Biol Cell. 2003;95:399–406. doi: 10.1016/s0248-4900(03)00087-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auerbach R. J Exper Zool. 1954;127:305–329. [Google Scholar]

- Beauchamp JR, Heslop L, Yu DS, Tajbakhsh S, Kelly RG, Wernig A, Buckingham ME, Partridge TA, Zammit PS. J Cell Biol. 2000;151:1221–34. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.6.1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biressi S, Molinaro M, Cossu G. Dev Biol. 2007a;308:281–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biressi S, Tagliafico E, Lamorte G, Monteverde S, Tenedini E, Roncaglia E, Ferrari S, Cusella-De Angelis MG, Tajbakhsh S, Cossu G. Dev Biol. 2007b;304:633–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bober E, Franz T, Arnold HH, Gruss P, Tremblay P. Development. 1994;120:603–12. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.3.603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bober E, Lyons GE, Braun T, Cossu G, Buckingham M, Arnold HH. The Journal of Cell Biology. 1991;113:1255–1265. doi: 10.1083/jcb.113.6.1255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutet SC, Disatnik MH, Chan LS, Iori K, Rando TA. Cell. 2007;130:349–62. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brack AS, Conboy IM, Conboy MJ, Shen J, Rando TA. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:50–9. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branda CS, Dymecki SM. Dev Cell. 2004;6:7–28. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00399-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun T, Arnold HH. EMBO J. 1995;14:1176–86. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07101.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brockschnieder D, Pechmann Y, Sonnenberg-Riethmacher E, Riethmacher D. Genesis. 2006;44:322–7. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckingham M. C R Biol. 2007;330:530–3. doi: 10.1016/j.crvi.2007.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckingham M, Vincent SD. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2009;19:444–53. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conboy IM, Rando TA. Dev Cell. 2002;3:397–409. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00254-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelison DD, Wold BJ. Dev Biol. 1997;191:270–83. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cusella-De Angelis MG, Molinari S, Le Donne A, Coletta M, Vivarelli E, Bouche M, Molinaro M, Ferrari S, Cossu G. Development. 1994;120:925–33. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.4.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emerson CP, Jr, Hauschka SD. Embryonic origins of skeletal muscles. In: Engel AG, Franzini-Armstrong C, editors. Myology. McGraw-Hill; New York: 2004. pp. 3–44. [Google Scholar]

- Engleka KA, Gitler AD, Zhang M, Zhou DD, High FA, Epstein JA. Dev Biol. 2005;280:396–406. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein DJ, Vogan KJ, Trasler DG, Gros P. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1993;90:532–536. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.2.532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franz T, Kothary R, Surani MA, Halata Z, Grim M. Anat Embryol (Berl) 1993;187:153–60. doi: 10.1007/BF00171747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gayraud-Morel B, ChrÈtien F, Flamant P, GomËs D, Zammit PS, Tajbakhsh S. Developmental Biology. 2007;312:13–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.08.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gensch N, Borchardt T, Schneider A, Riethmacher D, Braun T. Development. 2008;135:1597–604. doi: 10.1242/dev.019331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goulding M, Lumsden A, Paquette AJ. Development. 1994;120:957–71. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.4.957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunning P, Hardeman E. FASEB J. 1991;5:3064–70. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.5.15.1835946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haldar M, Karan G, Tvrdik P, Capecchi MR. Dev Cell. 2008;14:437–45. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasty P, Bradley A, Morris JH, Edmondson DG, Venuti JM, Olson EN, Klein WH. Nature. 1993;364:501–6. doi: 10.1038/364501a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinterberger TJ, Sassoon DA, Rhodes SJ, Konieczny SF. Dev Biol. 1991;147:144–56. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(05)80014-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horst D, Ustanina S, Sergi C, Mikuz G, Juergens H, Braun T, Vorobyov E. Int J Dev Biol. 2006;50:47–54. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.052111dh. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutcheson DA, Kardon G. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:3675–8. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.22.9992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutcheson DA, Zhao J, Merrell A, Haldar M, Kardon G. Genes Dev. 2009;23:997–1013. doi: 10.1101/gad.1769009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jostes B, Walther C, Gruss P. Mech Dev. 1990;33:27–37. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(90)90132-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kablar B, Krastel K, Ying C, Asakura A, Tapscott SJ, Rudnicki MA. Development. 1997;124:4729–4738. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.23.4729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang JS, Krauss RS. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2010;13:243–8. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e328336ea98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanisicak O, Mendez JJ, Yamamoto S, Yamamoto M, Goldhamer DJ. Dev Biol. 2009;332:131–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.05.554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kardon G, Campbell JK, Tabin CJ. Dev Cell. 2002;3:533–45. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00291-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassar-Duchossoy L, Gayraud-Morel B, Gomes D, Rocancourt D, Buckingham M, Shinin V, Tajbakhsh S. Nature. 2004;431:466–71. doi: 10.1038/nature02876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassar-Duchossoy L, Giacone E, Gayraud-Morel B, Jory A, Gomes D, Tajbakhsh S. Genes Dev. 2005;19:1426–31. doi: 10.1101/gad.345505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller C, Hansen MS, Coffin CM, Capecchi MR. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2608–13. doi: 10.1101/gad.1243904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuang S, Charge SB, Seale P, Huh M, Rudnicki MA. J Cell Biol. 2006;172:103–13. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200508001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuang S, Kuroda K, Le Grand F, Rudnicki MA. Cell. 2007;129:999–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepper C, Conway SJ, Fan CM. Nature. 2009;460:627–31. doi: 10.1038/nature08209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepper C, Fan CM. Genesis. 2010;48:424–36. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Czubryt MP, McAnally J, Bassel-Duby R, Richardson JA, Wiebel FF, Nordheim A, Olson EN. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:1082–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409103102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu BD, Allen DL, Leinwand LA, Lyons GE. Dev Biol. 1999;216:312–26. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansouri A, Stoykova A, Torres M, Gruss P. Development. 1996;122:831–8. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.3.831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathew SJ, Hansen JM, Merrell AJ, Lawson JA, Hutcheson DA, Hansen MS, Angus-Hill M, Kardon G. Development. doi: 10.1242/dev.057463. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauro A. J Biophys Biochem Cytol. 1961;9:493–5. doi: 10.1083/jcb.9.2.493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Megeney LA, Kablar B, Garrett K, Anderson JE, Rudnicki MA. Genes & Development. 1996;10:1173–1183. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.10.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messina G, Biressi S, Monteverde S, Magli A, Cassano M, Perani L, Roncaglia E, Tagliafico E, Starnes L, Campbell CE, Grossi M, Goldhamer DJ, Gronostajski RM, Cossu G. Cell. 2010;140:554–66. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muzumdar MD, Tasic B, Miyamichi K, Li L, Luo L. Genesis. 2007;45:593–605. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nabeshima Y, Hanaoka K, Hayasaka M, Esumi E, Li S, Nonaka I. Nature. 1993;364:532–5. doi: 10.1038/364532a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson EN, Arnold HH, Rigby PWJ, Wold BJ. Cell. 1996;85:1–4. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81073-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono Y, Calbaheu F, Morgan JE, Katagiri T, Amthor H, Zammit PS. Cell Death Differ. 2010 doi: 10.1038/cdd.2010.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ontell M, Ontell MP, Sopper MM, Mallonga R, Lyons G, Buckingham M. Development. 1993a;117:1435–44. doi: 10.1242/dev.117.4.1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ontell MP, Sopper MM, Lyons G, Buckingham M, Ontell M. Dev Dyn. 1993b;198:203–13. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001980306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ott MO, Bober E, Lyons G, Arnold H, Buckingham M. Development. 1991;111:1097–1107. doi: 10.1242/dev.111.4.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto A, Collins-Hooper H, Patel K. J Anat. 2009;215:477–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2009.01138.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto A, Schmidt C, Luke G, Allen S, Valasek P, Muntoni F, Lawrence-Watt D, Patel K. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:2939–50. doi: 10.1242/jcs.026534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oustanina S, Hause G, Braun T. Embo J. 2004;23:3430–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patapoutian A, Yoon JK, Miner JH, Wang S, Stark K, Wold B. Development. 1995;121:3347–58. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.10.3347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Ruiz A, Ono Y, Gnocchi VF, Zammit PS. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:1373–82. doi: 10.1242/jcs.024885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawls A, Morris JH, Rudnicki M, Braun T, Arnold HH, Klein WH, Olson EN. Dev Biol. 1995;172:37–50. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1995.0004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawls A, Valdez MR, Zhang W, Richardson J, Klein WH, Olson EN. Development. 1998;125:2349–58. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.13.2349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Relaix F, Marcelle C. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2009;21:748–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Relaix F, Montarras D, Zaffran S, Gayraud-Morel B, Rocancourt D, Tajbakhsh S, Mansouri A, Cumano A, Buckingham M. J Cell Biol. 2006;172:91–102. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200508044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Relaix F, Polimeni M, Rocancourt D, Ponzetto C, Schafer BW, Buckingham M. Genes Dev. 2003;17:2950–65. doi: 10.1101/gad.281203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Relaix F, Rocancourt D, Mansouri A, Buckingham M. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1088–105. doi: 10.1101/gad.301004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Relaix F, Rocancourt D, Mansouri A, Buckingham M. Nature. 2005 doi: 10.1038/nature03594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubinstein NA, Kelly AM. The Diversity of Muscle Fiber Types and Its Origin During Development. In: Engel AG, Franzini-Armstrong C, editors. Myology. McGraw-Hill; 2004. pp. 87–103. [Google Scholar]

- Rudnicki MA, Braun T, Hinuma S, Jaenisch R. Cell. 1992;71:383–90. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90508-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudnicki MA, Schnegelsberg PN, Stead RH, Braun T, Arnold HH, Jaenisch R. Cell. 1993;75:1351–9. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90621-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambasivan R, Gayraud-Morel B, Dumas G, Cimper C, Paisant S, Kelly RG, Tajbakhsh S. Dev Cell. 2009;16:810–21. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sassoon D, Lyons G, Wright WE, Lin V, Lassar A, Weintraub H, Buckingham M. Nature. 1989;341:303–7. doi: 10.1038/341303a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiaffino S, Reggiani C. Physiol Rev. 1996;76:371–423. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1996.76.2.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schienda J, Engleka KA, Jun S, Hansen MS, Epstein JA, Tabin CJ, Kunkel LM, Kardon G. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:945–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510164103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schubert FR, Tremblay P, Mansouri A, Faisst AM, Kammandel B, Lumsden A, Gruss P, Dietrich S. Dev Dyn. 2001;222:506–21. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seale P, Sabourin LA, Girgis-Gabardo A, Mansouri A, Gruss P, Rudnicki MA. Cell. 2000;102:777–86. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00066-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soriano P. Nat Genet. 1999;21:70–1. doi: 10.1038/5007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivas S, Watanabe T, Lin CS, William CM, Tanabe Y, Jessell TM, Costantini F. BMC Dev Biol. 2001;1:4. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-1-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockdale FE. Dev Biol. 1992;154:284–98. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(92)90068-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajbakhsh S. J Intern Med. 2009;266:372–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2009.02158.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajbakhsh S, Bober E, Babinet C, Pournin S, Arnold H, Buckingham M. Developmental Dynamics. 1996;206:291–300. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199607)206:3<291::AID-AJA6>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajbakhsh S, Buckingham M. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2000;48:225–68. doi: 10.1016/s0070-2153(08)60758-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajbakhsh S, Buckingham ME. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:747–51. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.2.747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajbakhsh S, Rocancourt D, Cossu G, Buckingham M. Cell. 1997;89:127–38. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80189-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tallquist MD, Weismann KE, Hellstrom M, Soriano P. Development. 2000;127:5059–70. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.23.5059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdez MR, Richardson JA, Klein WH, Olson EN. Dev Biol. 2000;219:287–98. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venuti JM, Morris JH, Vivian JL, Olson EN, Klein WH. J Cell Biol. 1995;128:563–76. doi: 10.1083/jcb.128.4.563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogan KJ, Epstein DJ, Trasler DG, Gros P. Genomics. 1993;17:364–9. doi: 10.1006/geno.1993.1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voytik SL, Przyborski M, Badylak SF, Konieczny SF. Dev Dyn. 1993;198:214–24. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001980307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Noulet F, Edom-Vovard F, Le Grand F, Duprez D. Dev Cell. 2010;18:643–54. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weintraub H, Davis R, Tapscott S, Thayer M, Krause M, Benezra R, Blackwell TK, Turner D, Rupp R, Hollenberg S, et al. Science. 1991;251:761–766. doi: 10.1126/science.1846704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White JD, Scaffidi A, Davies M, McGeachie J, Rudnicki MA, Grounds MD. J Histochem Cytochem. 2000;48:1531–44. doi: 10.1177/002215540004801110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White RB, Bierinx AS, Gnocchi VF, Zammit PS. BMC Dev Biol. 2010;10:21. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-10-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu S, Wu Y, Capecchi MR. Development. 2006;133:581–90. doi: 10.1242/dev.02236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yablonka-Reuveni Z, Rivera AJ. Dev Biol. 1994;164:588–603. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1994.1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yablonka-Reuveni Z, Rudnicki MA, Rivera AJ, Primig M, Anderson JE, Natanson P. Dev Biol. 1999;210:440–55. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto M, Shook NA, Kanisicak O, Yamamoto S, Wosczyna MN, Camp JR, Goldhamer DJ. Genesis. 2009;47:107–14. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zammit PS, Golding JP, Nagata Y, Hudon V, Partridge TA, Beauchamp JR. J Cell Biol. 2004;166:347–57. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200312007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zammit PS, Heslop L, Hudon V, Rosenblatt JD, Tajbakhsh S, Buckingham ME, Beauchamp JR, Partridge TA. Exp Cell Res. 2002;281:39–49. doi: 10.1006/excr.2002.5653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Behringer RR, Olson EN. Genes Dev. 1995;9:1388–99. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.11.1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]