Abstract

Synaptotagmins (syts) are a family of membrane proteins present on a variety of intracellular organelles. In vertebrates, 16 isoforms of syt have been identified. The most abundant isoform, syt I, appears to function as a Ca2+ sensor that triggers the rapid exocytosis of synaptic vesicles from neurons. The functions of the remaining syt isoforms are less well understood. The cytoplasmic domain of syt I binds membranes in response to Ca2+, and this interaction has been proposed to play a key role in secretion. Here, we tested the Ca2+-triggered membrane-binding activity of the cytoplasmic domains of syts I–XII; eight isoforms tightly bound to liposomes that contained phosphatidylserine as a function of the concentration of Ca2+. We then compared the disassembly kinetics of Ca2+·syt·membrane complexes upon rapid mixing with excess Ca2+ chelator and found that syts can be classified into three distinct kinetic groups. syts I, II, and III constitute the fast group; syts V, VI, IX, and X make up the medium group; and syt VII exhibits the slowest kinetics of disassembly. Thus, isoforms of syt, which have much slower disassembly kinetics than does syt I, might function as Ca2+ sensors for asynchronous release, which occurs after Ca2+ domains have collapsed. We also compared the temperature dependence of Ca2+·syt·membrane assembly and disassembly reactions by using squid and rat syt I. These results indicate that syts have diverged to release Ca2+ and membranes with distinct kinetics.

Keywords: Ca2+ sensor, kinetics, liposome, disassembly, isoform

Ca2+ triggers the release of neurotransmitters from presynaptic nerve terminals (1) and plays crucial roles in various forms of short-term plasticity (2, 3). Therefore, a detailed understanding of presynaptic Ca2+ dynamics has been the focus of considerable research over the last few decades (4–7). Presynaptic [Ca2+]i (intracellular Ca2+ concentration) rises and falls very rapidly during synaptic transmission, and these dynamics are shaped by a wide range of factors, including the spacing between Ca2+ channels and release sites, the buffering capacity of presynaptic cytosol, the rate of Ca2+ clearance after an action potential, and myriad additional factors (2, 7, 8). Because [Ca2+]i changes so quickly, the occupancy of a Ca2+ sensor, and the ensuring response, will depend critically on the kinetics of Ca2+ association and dissociation.

In a variety of synapses, two components of Ca2+-triggered neurotransmitter release have been resolved: a rapid component often termed “synchronous release” and a slower, delayed component sometimes called “asynchronous release” (9, 10). The molecular basis that underlies these two components remains unknown and, in principle, could be dictated by complex changes in Ca2+ dynamics, differences in the intrinsic Ca2+-sensing ability of the release machinery, or persistent activation ofaCa2+ sensor·effector complex, which could linger even after Ca2+ has dissociated. These last two possibilities have not yet been addressed experimentally and are the subject of the current study. Simply put, does the Ca2+ sensor that mediates asynchronous or delayed release “hang onto” Ca2+ and/or effectors longer than the synaptotagmin (syt) isoform that mediates rapid release?

For these studies, we have focused on the syts, some isoforms of which appear to function as Ca2+ sensors that couple Ca2+ to membrane fusion in vivo (11–14) and in vitro (15). Sixteen isoforms of syt have been identified (16). We hypothesize that after the collapse of Ca2+ microdomains, some isoforms of syt retain bound Ca2+ for different lengths of time, thus driving different levels of delayed release. It is also possible that different isoforms of syt “switch off” (i.e., release effectors) with distinct kinetics after Ca2+ has dissociated.

Here, we begin to test this hypothesis by comparing the kinetics of different syt isoforms. syts are thought to trigger exocytosis, at least in part, by binding to membranes in response to Ca2+ (17, 18). We therefore analyzed the kinetics of each isoform of syt that is capable of interacting with membranes and report that syts fall into three distinct kinetic groups with strikingly different kinetic properties. Our time-resolved studies demonstrated that steady-state measurements cannot reveal the identity of the “fast,” “medium,” and “slow” syts. These findings highlight the need to study, in the time domain, the biochemistry of the molecules that mediate rapid exocytosis.

Materials and Methods

Recombinant Proteins. cDNA encoding rat syts I (19), III (20), and IV (21) was provided by T.C. Südhof (University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas), S. Seino (Chiba University, Chiba, Japan), and H. Herschman (University of California, Los Angeles), respectively. cDNA encoding mouse syts II and V–XI (22) and squid syt I was provided by M. Fukuda (Institute of Physical and Chemical Research, Saitama, Japan). cDNA encoding syt XII (23) was provided by C. Thompson (The Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore). The cytoplasmic domain, containing both C2 domains (C2A and C2B), of each isoform was subcloned into pGEX-2T or 4T-1 (Amersham Biosciences) as described in ref. 24. The amino acid residues encoding these cytoplasmic domains are as follows: I, 96–421; II, 139–423; III, 290–569; IV, 152–425; V, 218–491; VI, 143–426; VII, 134–403; VIII, 97–395; IX, 104–386; X, 223–501; XI, 150–430; and XII, 114–421. For liposome-binding assays and Ca2+ dose responses, constructs were expressed in Escherichia coli as GST fusion proteins. For stopped-flow experiments, cytoplasmic domains were subcloned into pTrcHisA vector (Invitrogen) generating an N-terminal His-6 tag. GST-fusion and His-6-tagged proteins were purified on glutathione-Sepharose beads (Amersham Biosciences) and Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid-agarose (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), respectively, as described in ref. 25. Recombinant syts harbor tightly bound contaminants that may affect their properties (26). These bacterial contaminants were removed by using DNase/RNase and high-salt washes as described in ref. 27. His-6-tagged proteins were eluted from the beads by using imidazole (28).

Lipids. Synthetic 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-l-serine (phosphatidylserine, PS), 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (phosphatidylcholine, PC), 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-(5-dimethylamino-1-naphthalenesulfonyl) (dansyl-PE), and N-(lissamine rhodamine B sulfonyl)-1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids. l-1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho[N-methyl-3H]choline was purchased from Amersham Biosciences.

Liposomes. Lipids were dried under a stream of nitrogen and suspended in Hepes buffer (50 mM Hepes/150 mM NaCl, pH 7.4). For fluorescence studies and rhodamine-labeled liposomebinding assays, large (100-nm) unilamellar liposomes were prepared by extrusion as described in ref. 29. For 3H-labeled liposome-binding assays (Fig. 1C), liposomes were prepared by sonication with a Microson ultrasonic cell disruptor (Misonix, Farmingdale, NY), and binding assays were carried out as described in ref. 29 in 150 μl of Hepes buffer by using 6 μg of immobilized protein and 22 nM liposomes per data point. Rhodamine-labeled liposome-binding assays (Fig. 1B) were carried out in the same manner as the 3H-labeled liposome-binding assays. However, bound liposomes were eluted in Hepes buffer by using 1% Triton X-100. The solubilized lipids were collected, and binding was quantified by measuring the fluorescence intensity of rhodamine at 580 nm. Data were normalized, plotted, and fitted with sigmoidal dose-response curves (variable slope) by using prism 2.0 software (GraphPad, San Diego). In all experiments, error bars represent the SDs from triplicate determinations.

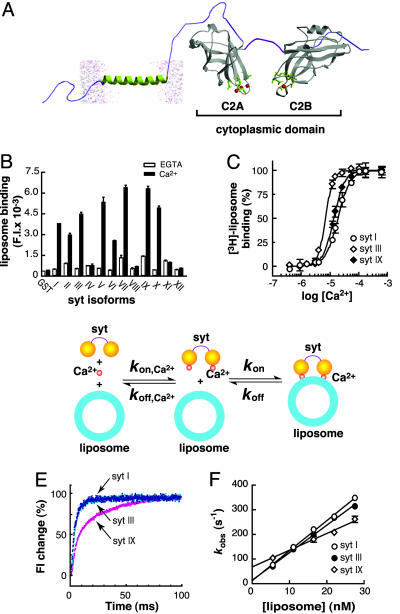

Fig. 1.

Interaction of syt isoforms with PS/PC liposomes. (A) Molecular model depicting the cytoplasmic domain (containing the C2A and C2B domains) of syt. The crystal structure of the cytoplasmic domain of syt III (45) was used as the template, and the membrane anchor and lipid bilayer were added by using a drawing program. For all experiments described in this study, syt refers to the intact cytoplasmic domain lacking the membrane-anchoring domain. (B) Screening syts I–XII for Ca2+-triggered PS/PC liposome-binding activity. syt·PS/PC liposome interactions were studied by using fluorescently labeled liposome pull-down assay. The cytoplasmic domains of syts I–XII were immobilized on glutathione-Sepharose beads and assayed for binding of PS/PC liposome in the presence of 2 mM EGTA (open bars) or 0.2 mM Ca2+ (filled bars), as described in Materials and Methods. Liposomes were composed of 1% N-(lissamine rhodamine B sulfonyl)-1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine, 25% PS, and 74% PC. (C) syt III exhibits a higher apparent affinity for Ca2+ than does syt I or IX. Immobilized GST-syt I, GST-syt III, and GST-syt IX were assayed for 3H-labeled liposome (25% PS/75% PC)-binding activity as a function of [Ca2+] as described in ref. 29. The [Ca2+]1/2 values for syts I, III, and IX were 18.8 ± 2.2, 7.0 ± 0.8, and 13.6 ± 1.3 μM, respectively; the Hill slopes for syts I, III, and IX were 2.0 ± 0.3, 2.3 ± 0.3, and 3.5 ± 0.3, respectively. (D) Model describing the assembly of Ca2+·syt·liposome complexes. The rate constants measured in these experiments correspond to the on-rate (kon) and off-rate (koff) for the second step; Ca2+ binding in the first step is too fast to measure in these experiments because of the need to use micromolar levels of Ca2+ to trigger binding (29). (E and F) Comparison of the on- and off-rates for interactions of syts I, III, and IX with PS/PC liposomes in the presence of Ca2+. Stopped-flow rapid-mixing experiments were carried out at 14.5°C as described in Materials and Methods. (E) Representative kinetics traces of syts I, III, and IX are shown. Liposomes (22 nM, 5% dansyl-PE/25% PS/70% PC) were premixed with 0.2 mM Ca2+ and then rapidly mixed (1:1) with 4 μM syt I, III, or IX. Single exponential functions were used to determine the observed rates (kobs) of Ca2+-dependent syt I and syt III·liposome interactions; a double exponential was needed to fit the data for syt IX·liposome interactions. (F) kobs was plotted as a function of [liposome]. In the case of syt IX, the fast component was used. The y intercept yields koff, and the slope yields kon for the interaction of syt with membranes in the presence of Ca2+. Error bars represent SDs of three independent experiments. The dissociation constants (Kd) for syt·liposome interactions in the presence of Ca2+ were calculated as koff/kon. Values of Kd, kon, and koff are summarized in Table 1. Note that the rate constants of the slower component for syt IX·liposomes interactions were not dependent on the [liposome], suggesting that this component reports a postbinding conformational change in syt IX.

Stopped-Flow Rapid-Mixing Experiments. FRET was used to monitor the time course of Ca2+-dependent syt·PS/PC liposome interactions by using an SX.18MV stopped-flow spectrometer (Applied Photophysics, Surrey, U.K.) as described in ref. 30. Native Trp residue(s) in syt and dansyl groups attached to phospholipids in the liposomes served as energy donors and acceptors, respectively. The Trps in the cytoplasmic domain of each isoform of syt were excited at 285 nm, and the emission from the dansyl-PE acceptor was collected by using a 470-nm cutoff filter. The dead time was ≈1 ms.

Results

The cytoplasmic domain of syt is largely composed of tandem C2 domains that are connected by means of a flexible linker (19) (Fig. 1 A). In some isoforms, each C2 domain functions as a Ca2+-sensing module that interacts with a number of effectors in response to rapid changes in intracellular Ca2+ concentration (31). Current evidence indicates that syt operates by binding, in response to Ca2+, anionic lipids (e.g., PS) and the t-SNAREs syntaxin and SNAP-25 (15, 18, 32). To measure the kinetics of syt·t-SNARE interactions, we must use micromolar concentrations of protein; these conditions result in complete binding within 1 msec, which falls within the dead time of our stopped-flow instrument (32). Thus, we were unable to compare syt kinetics by using t-SNAREs as the effector. However, the kinetics of syt·liposome interactions, using membranes that contain PS, can be readily monitored in real time in the stopped-flow device (27, 29, 33) because low concentrations (i.e., nanomolar range) of liposomes are used. Therefore, we compared the kinetics of different isoforms of syt by using PS-harboring liposomes as the effector.

We first screened the membrane-binding activity of syts I–XII by using liposomes that contained 25% PS, 74% PC, and 1% rhodamine-labeled phosphatidylethanolamine as the tracer. With the exception of syts IV, VIII, XI, and XII, most members of the syt family bound to the PS-harboring liposomes in a Ca2+-dependent manner (Fig. 1B). We note that a recent study also addressed the ability of each isoform of syt to bind PS/PC liposomes (34). However, binding was assayed by the cosedimentation of syt with liposomes because syts also oligomerize and precipitate in the presence of Ca2+ and membranes. The cosedimentation assay is not an accurate method to measure syt·membrane interaction (35).

We then picked three representative isoforms of syt (from the kinetic analysis presented below), I, III, and IX, to resolve the question of whether they have the same or different Ca2+ requirements for binding to membranes. For example, the C2A domains of syt I and III have been reported to have virtually identical [Ca2+]1/2 values in some studies (36–38) and distinct [Ca2+]1/2 values in another study (39). The [Ca2+]1/2 values and Hill slopes for syt I were 18.8 ± 2.2 μM and 2.0, respectively; for syt III the values were 7.0 ± 0.8 μM and 3.6, respectively; for syt IX the values were 13.6 ± 1.3 μM and 2.3, respectively. Among these isoforms, syt III has the lowest [Ca2+]1/2 value, followed by syt IX and syt. In these experiments, the [Ca2+] was measured by using a Ca2+-sensitive electrode. The data concerning syt I are consistent with previous reports (29, 33).

To investigate further the properties of syts, we determined the affinities of the same three syt isoforms (I, III, and IX) for PS-harboring liposomes (5% dansyl-PE/25% PS/70% PC) by measuring the assembly kinetics of the Ca2+·syt·liposome complex, using a stopped-flow rapid-mixing approach. FRET was used to monitor the time course of complex formation (30). The native Trp residues in each syt isoform were used as the energy donors, and a dansyl group that was incorporated into the liposomes (as dansyl-PE) served as the energy acceptor. Rapid mixing of liposome/Ca2+ mixtures with syt resulted in a rapid increase in the emission of the acceptor (Fig. 1E). The kinetics traces were well fitted with exponential functions to determine the observed rate constant, kobs. We then measured kobs as a function of [liposome]; these data are plotted in Fig. 1F. The slope yields kon, and the y intercept yields koff. These values are listed in Table 1. The dissociation constants (Kd) were then calculated by koff/kon, and the values for syts I, III, and IX were 1.0, 1.1, and 9.8 nM, respectively (Table 1). The Ca2+-dependent liposome-binding affinity for syts I and III are similar; that for syt IX is significantly lower. Together, these experiments indicate that, at least in these three syt isoforms, the affinity of the Ca2+·protein complex for membranes is not necessarily related to the affinity of the membrane·protein complex for Ca2+.

Table 1. Kinetics of Ca2+ syt liposome assembly.

| syt isoform | kon, 1010 M-1·sec-1 | koff, sec-1 | Kd, nM |

|---|---|---|---|

| syt I | 1.21 ± 0.03 | 12.0 ± 5.2 | 1.0 |

| syt III | 0.03 ± 1.12 | 12.8 ± 6.2 | 1.1 |

| syt IX | 0.68 ± 0.06 | 66.6 ± 10.3 | 9.8 |

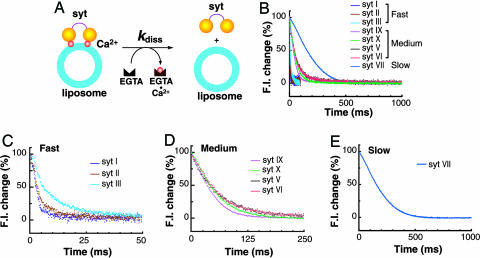

We extended our study to the disassembly kinetics of Ca2+·syt·liposome complexes, again using stopped-flow rapid mixing and FRET. We expected that in these kinetics experiments, the isoforms with higher apparent affinity for Ca2+ would retain bound Ca2+ longer upon rapid mixing with excess Ca2+ chelator, thus yielding slower rates of disassembly. For example, based on the measurements above, we expected that syt III would release Ca2+, and hence liposomes, more slowly than would syts I or IX. Moreover, from the measurements above, we anticipated that syts I and IX would exhibit similar disassembly kinetics. Surprisingly, these predications were not borne out by the experimental data (detailed below).

To carry out these experiments, liposomes (5% dansyl-PE/25% PS/70% PC) were premixed with syt in the presence of Ca2+ and then rapidly mixed with Hepes buffer containing excess EGTA. The chelation of Ca2+ by EGTA resulted in a rapid loss of the fluorescent signal (Fig. 2B). All of the kinetic traces could be well fitted by exponential functions to estimate the rate constants for disassembly (Table 2). According to the overall rate of disassembly, we divided syts into three kinetic groups: fast, medium, and slow. syts I, II, and III fell into the fast group, which disassembled within 50 msecs; syts V, VI, IX, and X belonged to the medium group, which disassembled within 250 msec. For syt VII, the only member in the slow group, disassembly required almost 500 msec. Surprisingly, these groupings do not appear to be correlated with the Ca2+ sensitivities as measured under steady-state conditions. As noted above, syt III has the highest apparent affinity for Ca2+ (among syts I, III, and IX), yet it dissociated from liposomes upon chelation of Ca2+ almost as rapidly as syt I. However, syt IX, which has a lower apparent affinity for Ca2+ than does syt III (Fig. 1C), disassembled from liposomes upon mixing with chelator much more slowly than did syt III. These results suggest that Ca2+ sensitivities for liposome binding in the steady state might not provide information regarding the ability of the protein·membrane complex to “hold onto” Ca2+ upon removal of free Ca2+ with chelator. However, it remains possible that some isoforms of syt release Ca2+ quickly but dissociate from membrane more slowly. This latter model can be viewed as the persistent activation of a syt·effector complex, as alluded to in the introduction.

Fig. 2.

syts are released from liposomes upon chelation of Ca2+ with distinct kinetics. Disassembly of Ca2+·syt·liposome complexes was monitored by using FRET as shown in Fig. 1E. All experiments were carried out at 14.5°C. Liposomes (44 nM) were premixed with syt (4 μM) in the presence of Ca2+ (0.2 mM) and then rapidly mixed with an equal volume of Hepes buffer containing 2 mM EGTA. The rate constants for disassembly (kdiss), determined by fitting the kinetics traces with single or double exponential functions, are provided in Table 2. (A) Model depicting the disassembly of Ca2+·syt·liposome complexes upon rapid mixing with EGTA. (B) Representative traces of disassembly reactions. Based on the disassembly kinetics, syt isoforms are divided into three kinetic groups: fast, medium, and slow. (C) syts I, II, and III exhibit fast disassembly kinetics. (D) syts IX, X, V, and VI disassemble from liposomes at intermediate rates. (E) syt VII disassembles from liposomes with the slowest kinetics.

Table 2. Disassembly kinetics of Ca2+·syt·liposome complexes.

| syt isoform | Fitting equation | k1, sec-1 | Amplitude 1, % | k2, sec-1 | Amplitude 2, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| syt I | Single exponential | 378 ± 11 | — | — | — |

| syt II | Single exponential | 333 ± 32 | — | — | — |

| syt III | Double exponential | 244 ± 16 | 73.2 ± 8.6 | 53.7 ± 1.9 | 26.6 ± 8.6 |

| syt V | Single exponential | 15.9 ± 1.4 | — | — | — |

| syt VI | Single exponential | 15.7 ± 0.1 | — | — | — |

| syt VII | Double exponential | 19.7 ± 5.4 | 28.6 ± 9.6 | 8.0 ± 2.5 | 71.4 ± 9.6 |

| syt IX | Single exponential | 28.1 ± 12 | — | — | — |

| syt X | Single exponential | 20.9 ± 6.4 | — | — | — |

k1, rate constant of the first exponential component; k2, rate constant of the second exponential component; —, no data.

In contrast to earlier reports based on steady-state measurements (37), the kinetics data reported here reveal that syt III is unlikely to function as the “high-affinity” Ca2+ sensor that mediates slow asynchronous release; this isoform is too fast. The best candidates for the high-affinity Ca2+ sensor that drives asynchronous transmission are members of the slow or medium-speed group: syt V, VI, VII, IX, or X.

We note that for syt VII, the kinetics traces of the disassembly reactions can only be well fitted with double, rather than single, exponential functions, and the first exponential component has a negative amplitude (Table 2). These data indicate that the disassembly reaction is more complex for this isoform than for the others, perhaps owing to the propensity of this isoform to avidly oligomerize (40), which, in turn, could retard the rate of disassembly.

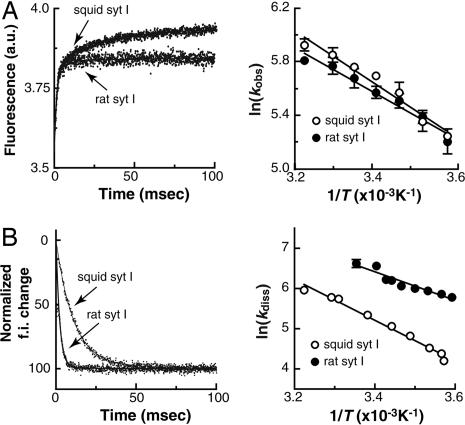

In the final series of experiments, we explored the effect of temperature on the kinetics of assembly and disassembly of Ca2+·syt·liposome complexes. For these studies, we compared syt I from two species with distinct internal body temperatures: rat and squid. The squid protein was of particular interest, because this animal's body temperature changes with the environment. Thus, the squid protein might be expected to be less temperature-dependent. We carried out assembly and disassembly assays as described above. For Ca2+·syt·liposome assembly reactions, the kinetics traces of rat syt I were single exponentials, whereas those for squid syt I were double exponentials (Fig. 3A Left). The observed rate constants (kobs) for the assembly of rat syt I and squid syt I with Ca2+ and liposomes were very similar over the range of temperatures tested. These data are presented as Arrhenius plots in Fig. 3A Right.

Fig. 3.

The temperature dependence of the kinetics of rat and squid syt I interactions with PS/PC liposomes. For these experiments, FRET was used to monitor the time course of assembly (kobs) and disassembly (kdiss) of syt·liposome complexes, as shown in Fig. 1E. (A) Temperature dependence of the kinetics of Ca2+-triggered syt·liposome interactions. (Left) Representative kinetics traces of squid and rat syt I binding to liposomes in response to Ca2+ at 25°C. The FRET signal for rat Ca2+·syt·liposome assembly was a single exponential. The traces obtained by using squid syt were best fitted by double exponentials; the slower component might represent postbinding conformational changes or molecular rearrangements [e.g., oligomerization (35)] because it is not dependent on [liposome]. (Right) Arrhenius plot of ln(kobs) versus 1/T for the interaction of rat and squid (the fast component) syt with liposomes. The activation energy (Ea) was calculated from the slope, and this value was 15.8 ± 1.4 kJ/mol for squid syt I and 13.5 ± 1.2 kJ/mol for rat syt I. (B) Temperature dependence of the disassembly kinetics of syt·liposome complexes upon removal of Ca2+. (Left) Kinetic traces of squid and rat syt I unbinding from liposomes upon rapid mixing with excess EGTA at 10°C. Disassembly traces were well fitted with single exponential functions. The disassembly of squid syt·liposome complexes is much slower than that for the complex containing rat syt I. (Right) Arrhenius plot of ln(kdiss) versus 1/T for the disassembly of rat and squid (the fast component) syt I from liposomes. Ea was 42.1 ± 1.2 kJ/mol for squid syt I and 29.9 ± 2.2 kJ/mol for rat syt I. The disassembly of rat syt·liposome complexes was too fast to monitor when at temperatures > 25°C (i.e., the reaction was complete within the 1-msec dead time of the stopped-flow setup).

Results from the Ca2+·syt·liposome disassembly reactions, carried out at different temperatures, yielded a different conclusion. The kinetics traces for both rat syt I and squid syt I were best fitted with single exponential functions, but, at the same temperature, disassembly of squid Ca2+·syt·liposome complexes is much slower than for the rat protein (Fig. 3B Left). Moreover, kdiss (the rate of disassembly) of rat syt I became too fast to observe at temperatures > 25°C. These differences in the disassembly rates between squid and rat syt point to differences in the manner in which these orthologs release Ca2+. The temperature dependencies for disassembly of both the rat and squid protein are also presented as Arrhenius plots in Fig. 3B Right. The overall temperature dependencies were similar, although the squid protein had a somewhat higher energy of activation; Ea for squid syt I was 42 kJ/mol, and for rat syt I this value was 30 kJ/mol (Fig. 3B Right).

Discussion

In this study, we observed that Ca2+·syt·liposome complexes disassemble in response to rapid mixing with excess Ca2+ chelator with distinct kinetics, depending on the syt isoform under study. These experiments were intended to mimic the collapse of local Ca2+ microdomains (4, 41) and determine whether complexes with distinct isoforms of syt bound to liposomes respond to drops in [Ca2+] with the same or distinct kinetics. The observation that some syts release Ca2+, and hence membranes, quickly, whereas other isoforms of syt remain in complexes for longer lengths of time, has ramifications for presynaptic function. For example, the slow isoforms of syt (syts V, VI, VII, X, and IX) are good candidates to serve as Ca2+ sensors during asynchronous or delayed release, which is a component of exocytosis that persists tens to hundreds of milliseconds after Ca2+ domains have collapsed, presumably because Ca2+ stays bound to a Ca2+ sensor (e.g., a syt isoform) that is capable of driving exocytosis. In contrast, syts I, II, and III released Ca2+ and membranes with very rapid kinetics, and thus are good candidates for mediating the rapid phasic component of transmission. Indeed, genetic studies demonstrated that rat and fly syt I is essential for rapid transmission (14, 42–44). In the absence of syt I, delayed release was enhanced, perhaps owing to the action of a syt isoform with slow kinetics. In this model, expression of syt I would, in principle, titrate out the slow sensor at release sites to give rise to rapid transmission. Thus, an essential issue is to establish the subcellular localization of each isoform of syt. At present, syt I has been unambiguously localized to synaptic and dense-core vesicles, but the subcellular distribution of the other isoforms is the subject of much debate (reviewed in ref. 31).

The distinct kinetics at which syt isoforms release Ca2+ and membranes might also underlie aspects of synaptic plasticity, such as paired-pulse facilitation, in which bound Ca2+ is thought to enhance the exocytosis in response to another rise in local [Ca2+] (2). A test of these hypotheses will involve experimental manipulation of syt isoforms in neurons. For example, the ratio of slow to fast syts could be increased or decreased. Detailed electrophysiological experiments will reveal whether these changes impact the relative levels of fast versus delayed release and/or whether these manipulations impact aspects of short-term synaptic plasticity.

Acknowledgments

We thank Meyer Jackson and members of E.R.C.'s laboratory for critical discussions. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Institute of General Medical Sciences Grant GM 56827 (to E.R.C), NIH National Institute of Mental Health Grant MH61876 (to E.R.C.), NIH National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Grant 13742 (to R.R.L.), and American Heart Association Grant 0440168N (to E.R.C.).

Author contributions: E.H., J.B., M.S., R.R.L., and E.R.C. designed research; E.H., J.B., P.W., M.S., R.R.L., and E.R.C. performed research; J.B., M.S., R.R.L., and E.R.C. analyzed data; and E.H. and E.R.C. wrote the paper.

Abbreviations: syt, synaptotagmin; PS, phosphatidylserine; PC, phosphatidylcholine; dansyl-PE, 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-(5-dimethylamino-1-naphthalenesulfonyl).

References

- 1.Katz, B. (1969) The Release of Neural Transmitter Substances (Thomas, Springfield, IL).

- 2.Zucker, R. S. & Regehr, W. G. (2002) Annu. Rev. Physiol. 64, 355–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zengel, J. E. & Magleby, K. L. (1982) J. Gen. Physiol. 80, 583–611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Llinas, R., Sugimori, M. & Silver, R. B. (1992) Science 256, 677–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Llinas, R., Steinberg, I. Z. & Walton, K. (1981) Biophys. J. 33, 323–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Augustine, G. J. & Neher, E. (1992) Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2, 302–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Neher, E. (1998) Neuron 20, 389–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meinrenken, C. J., Borst, J. G. & Sakmann, B. (2002) J. Neurosci. 22, 1648–1667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goda, Y. & Stevens, C. F. (1994) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91, 12942–12946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Atluri, P. P. & Regehr, W. G. (1998) J. Neurosci. 18, 8214–8227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nonet, M. L., Grundahl, K., Meyer, B. J. & Rand, J. B. (1993) Cell 73, 1291–1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Littleton, J. T., Stern, M., Perin, M. & Bellen, H. J. (1994) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91, 10888–10892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DiAntonio, A. & Schwarz, T. L. (1994) Neuron 12, 909–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Geppert, M., Goda, Y., Hammer, R. E., Li, C., Rosahl, T. W., Stevens, C. F. & Sudhof, T. C. (1994) Cell 79, 717–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tucker, W. C., Weber, T. & Chapman, E. R. (2004) Science 304, 435–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Craxton, M. (2004) BMC Genomics 5, 43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brose, N., Petrenko, A. G., Sudhof, T. C. & Jahn, R. (1992) Science 256, 1021–1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bai, J. & Chapman, E. R. (2004) Trends Biochem. Sci. 29, 143–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perin, M. S., Fried, V. A., Mignery, G. A., Jahn, R. & Sudhof, T. C. (1990) Nature 345, 260–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mizuta, M., Inagaki, N., Nemoto, Y., Matsukura, S., Takahashi, M. & Seino, S. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 11675–11678. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vician, L., Lim, I. K., Ferguson, G., Tocco, G., Baudry, M. & Herschman, H. R. (1995) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92, 2164–2168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fukuda, M., Kanno, E. & Mikoshiba, K. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 31421–31427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Potter, G. B., Facchinetti, F., Beaudoin, G. M., III, & Thompson, C. C. (2001) J. Neurosci. 21, 4373–4380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tucker, W. C., Edwardson, J. M., Bai, J., Kim, H. J., Martin, T. F. & Chapman, E. R. (2003) J. Cell Biol. 162, 199–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chapman, E. R., Hanson, P. I., An, S. & Jahn, R. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 23667–23671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ubach, J., Lao, Y., Fernandez, I., Arac, D., Sudhof, T. C. & Rizo, J. (2001) Biochemistry 40, 5854–5860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bai, J., Tucker, W. C. & Chapman, E. R. (2004) Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 11, 36–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chapman, E. R., An, S., Edwardson, J. M. & Jahn, R. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 5844–5849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Davis, A. F., Bai, J., Fasshauer, D., Wolowick, M. J., Lewis, J. L. & Chapman, E. R. (1999) Neuron 24, 363–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang, P., Wang, C. T., Bai, J., Jackson, M. B. & Chapman, E. R. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 47030–47037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tucker, W. C. & Chapman, E. R. (2002) Biochem. J. 366, 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bai, J., Wang, C. T., Richards, D. A., Jackson, M. B. & Chapman, E. R. (2004) Neuron 41, 929–942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bai, J., Wang, P. & Chapman, E. R. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 1665–1670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rickman, C., Craxton, M., Osborne, S. & Davletov, B. (2004) Biochem. J. 378, 681–686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wu, Y., He, Y., Bai, J., Ji, S. R., Tucker, W. C., Chapman, E. R. & Sui, S. F. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 2082–2087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li, C., Ullrich, B., Zhang, J. Z., Anderson, R. G., Brose, N. & Sudhof, T. C. (1995) Nature 375, 594–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li, C., Davletov, B. A. & Sudhof, T. C. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 24898–24902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ullrich, B., Li, C., Zhang, J. Z., McMahon, H., Anderson, R. G., Geppert, M. & Sudhof, T. C. (1994) Neuron 13, 1281–1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sugita, S., Shin, O. H., Han, W., Lao, Y. & Sudhof, T. C. (2002) EMBO J. 21, 270–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fukuda, M., Katayama, E. & Mikoshiba, K. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 29315–29320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Augustine, G. J., Santamaria, F. & Tanaka, K. (2003) Neuron 40, 331–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nishiki, T. & Augustine, G. J. (2004) J. Neurosci. 24, 6127–6132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nishiki, T. & Augustine, G. J. (2004) J. Neurosci. 24, 8542–8550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yoshihara, M. & Littleton, J. T. (2002) Neuron 36, 897–908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sutton, R. B., Ernst, J. A. & Brunger, A. T. (1999) J. Cell Biol. 147, 589–598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]