SUMMARY

Understanding the relative contributions of genetic and epigenetic abnormalities to acute myeloid leukemia (AML) should assist integrated design of targeted therapies. In this study, we generated induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) from AML patient samples harboring MLL rearrangements and found that they retained leukemic mutations but reset leukemic DNA methylation/gene expression patterns. AML-iPSCs lacked leukemic potential, but when differentiated into hematopoietic cells, they reacquired the ability to give rise to leukemia in vivo and reestablished leukemic DNA methylation/gene expression patterns, including an aberrant MLL signature. Epigenetic reprogramming was therefore not sufficient to eliminate leukemic behavior. This approach also allowed us to study the properties of distinct AML subclones, including differential drug susceptibilities of KRAS mutant and wild-type cells, and predict relapse based on increased cytarabine resistance of a KRAS wild-type subclone. Overall, our findings illustrate the value of AML-iPSCs for investigating the mechanistic basis and clonal properties of human AML.

INTRODUCTION

Epigenetic dysregulation is an established feature of human acute myeloid leukemia (AML) that is implicated in disease pathogenesis (Melnick, 2010; Shih et al., 2012). Aberrant DNA methylation, histone modifications, and chromatin accessibility are observed in AML both in the presence and absence of mutations in key epigenetic regulatory factors (Ntziachristos et al., 2016; Wouters and Delwel, 2016). These observations suggest that epigenetic dysregulation may independently contribute to leukemogenesis, a concept broadly proposed in cancer and referred to as epigenetic stochasticity (reviewed in Timp and Feinberg, 2013). This model proposes that oncogenic mutations act within the context of an epigenetic setting conducive to cancer development, often with epigenetic dysregulation establishing the context. For example, in several human cancers including Wilms’ tumor and colorectal cancer, loss of imprinting of insulin-like growth factor 2 (IGF2) leads to increased activity of this mitogen and promotes cancer development and progression upon acquisition of additional mutations (Leick et al., 2011; Sakatani et al., 2005; Steenman et al., 1994). Mechanistic studies in immortalized fibroblasts demonstrated that DNA methylation patterns are heterogeneous and polymorphic, generated through a stochastic process that eventually results in deterministic epigenetic remodeling that may be critical for the emergence of cancer-specific epigenetic patterns (Landan et al., 2012).

In leukemogenesis, several recent studies have indicated that the nature of the resulting disease is dependent on the cellular context in which mutations occur. For example, in the commonly employed retroviral MLL-AF9 model, transduced HSCs developed more aggressive, chemoresistant disease compared to GMP-derived leukemias (Krivtsov et al., 2013). Using this same model, AML failed to develop when myeloid differentiation of HSCs to GMPs was blocked, even though the oncogene was expressed in HSCs (Ye et al., 2015). These studies demonstrate that the epigenetic context is critical to the development and characteristics of the resulting AML.

Given the importance of the epigenome, a number of epigenetic targeted therapies have been used to treat AML, but thus far with limited efficacy (Stein and Tallman, 2016). Despite this recent focus, the reversibility of epigenetic modifications and relative contributions of leukemic genetic and epigenetic programs to pathogenesis in AML are poorly understood. To investigate these questions, we sought to reprogram primary AML leukemic blasts into induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) and assess the effect of epigenetic reprogramming on leukemic behavior.

Epigenetic reprogramming of somatic human cells to a pluripotent stem cell state has been achieved through the expression of defined sets of transcription factors (Takahashi et al., 2007), while leaving underlying genetic abnormalities intact. The ability to globally modulate and reverse epigenetic alterations separate from underlying genetic abnormalities has broad applications to studying the interactions between genetic and epigenetic drivers of oncogenesis.

Like many cancers, genome sequencing in AML has demonstrated that most cases are composed of a mixture of disease subclones defined by variable mutation composition (Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network, 2013; Ding et al., 2012; Walter et al., 2012). Indeed, the presence of subclones has major implications for disease pathogenesis and relapse and more importantly, for the development of targeted therapies (Alizadeh et al., 2015). One major barrier to investigation of cancer sub-clones is that reliable methods to separate disease subclones to permit detailed characterization do not yet exist. Notably, because iPSCs are derived from single cells and passaged as clones, subclones can be separated to permit such detailed characterization.

Here, we sought to reprogram primary human AML leukemic blasts into iPSCs to facilitate investigation of a number of key questions. First, can AML cells with multiple karyotypic and genetic abnormalities be successfully reprogrammed into iPSCs? Second, if reprogramming is possible, are leukemia-specific epigenetic abnormalities reversed? Third, does the reprogramming process suppress leukemic behavior, and can these AML-derived iPSCs give rise to leukemia when forced to differentiate? Finally, can iPSCs from distinct subclones serve as a model to therapeutically target individual subclones within an AML patient?

RESULTS

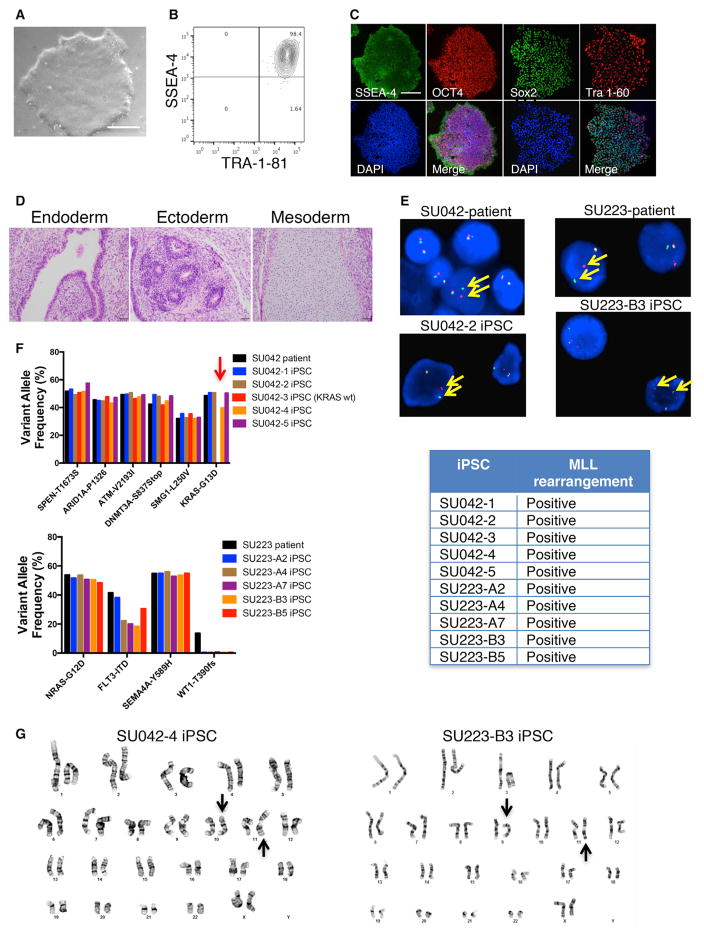

Human AML Cells Can Be Reprogrammed into iPSCs while Retaining the Original Patient Mutations and Cytogenetic Abnormalities

We identified two cases of AML (SU042 and SU223) harboring 11q23/MLL rearrangements and used targeted sequencing to identify additional somatic mutations in the leukemic blasts (Figure S1A). Using non-integrating Sendai virus, we transduced blasts with iPSC reprogramming factors (Sox-2, Klf4, Oct4, and Myc) to attempt pluripotent reprogramming (Figure S1B). Reprogrammed AML cells gave rise to iPSCs as indicated by classic pluripotency features including iPSC morphology and expression of pluripotency markers (Figures 1A–1C and S1C–S1E). When transplanted into immunodeficient mice, these cells formed teratomas indicative of successful iPSC formation (Figures 1D and S1F). Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis demonstrated presence of the MLL rearrangement in multiple iPSC clones derived from each patient (Figure 1E). Targeted sequencing identified the presence of the leukemia-specific mutations in each case (Figure 1F). Notably, in case SU042, one clone (SU042-3) harbored all the leukemia-specific mutations except for KRAS-G13D, indicating it was derived from a KRAS wild-type subclone. In case SU223, a frameshift mutation in WT1 was found to be subclonal, and all iPSC clones were derived from WT1 wild-type leukemic cells. Cytogenetic analysis of AML-derived iPSCs (AML-iPSCs) demonstrated the MLL rearrangement without additional chromosomal abnormalities (Figures 1G and S1G). These data demonstrate that AML cells can be successfully reprogrammed into iPSCs that retain the original genetic abnormalities.

Figure 1. Human AML Cells Can Be Reprogrammed into iPSCs while Retaining the Original Patient Mutations and Cytogenetic Abnormalities.

(A) SU042 AML patient cells were transduced with SKOM factors via Sendai virus. Resulting clones were assessed by light microscopy (clone SU042-2 is shown). Scale bar, 200 μm.

(B and C) Candidate iPSC clone SU042-2 was analyzed for pluripotency markers by flow cytometry (B) and immunofluorescence (C). Scale bar, 500 μm.

(D) SU042-2 cells were transplanted subcutaneously into NSG mice and resulting tumors were assessed for teratoma formation by H&E staining. Scale bar, 50 μm.

(E) AML patient cells and iPSC clones were assessed for MLL rearrangement by FISH using break apart probes of the 5′ and 3′ ends of MLL (arrows).

(F) The variant allele frequencies of leukemia mutations in AML patient cells and AML-iPSC clones were determined by DNA sequencing. Note that clone SU042-3 (arrow) harbored all leukemic mutations except KRAS-G13D.

(G) Karyotypic analysis of AML-iPSCs was performed, and arrows denote t(10;11) for SU042 and t(9;11) for SU223.

AML-iPSCs Differentiated into Non-hematopoietic Lineages Exhibit Normal Cellular Morphology and Function

AML-iPSCs from both cases possessed mutations known to be oncogenic drivers in multiple cancer types, including CNS tumors, such as MLL, ARID1A, ATM, and RAS (Choi et al., 2016; Knobbe et al., 2004; Parsons et al., 2011; Prior et al., 2012; Sausen et al., 2013). To investigate whether AML-iPSCs give rise to normal, non-tumorigenic cell types in the presence of these oncogenes, we differentiated them into the neural and cardiomyocyte lineages (Figure S2). Neuronal cells differentiated from AML-iPSCs demonstrated normal neuronal morphology with expression of the pan-neuronal marker Map2 and presynaptic marker synapsin similar to control iPSC line C6-a (Figure S2B). These neurons fired spontaneous and current-induced action potentials and demonstrated the presence of voltage-gated Na+/K+ channels and AMPAR-mediated excitatory postsynaptic currents similar to control (Figure S2C). Next, AML-iPSCs were differentiated into cardiomyocytes (CMs) through culture in CM-specific support media (Figure S2D). AML-iPSCs yielded similar percentages of cardiac troponin T (cTnT) expressing cells compared to a control iPSC line (Figure S2E). Differentiated CMs demonstrated typical cardiomyocyte morphology and expression of cardiac-specific markers cardiac troponin T type 2 (Tnnt2) and actinin (Figure S2F). Both contractile stress and contractility rates were similar between CMs differentiated from AML-iPSCs and control (Figure S2G), with no difference in several parameters assessing calcium handling (Figure S2H). In summary, despite the presence of several oncogenic driver mutations in AML-iPSCs, normal differentiation occurred down non-hematopoietic lineages without evidence of tumor formation.

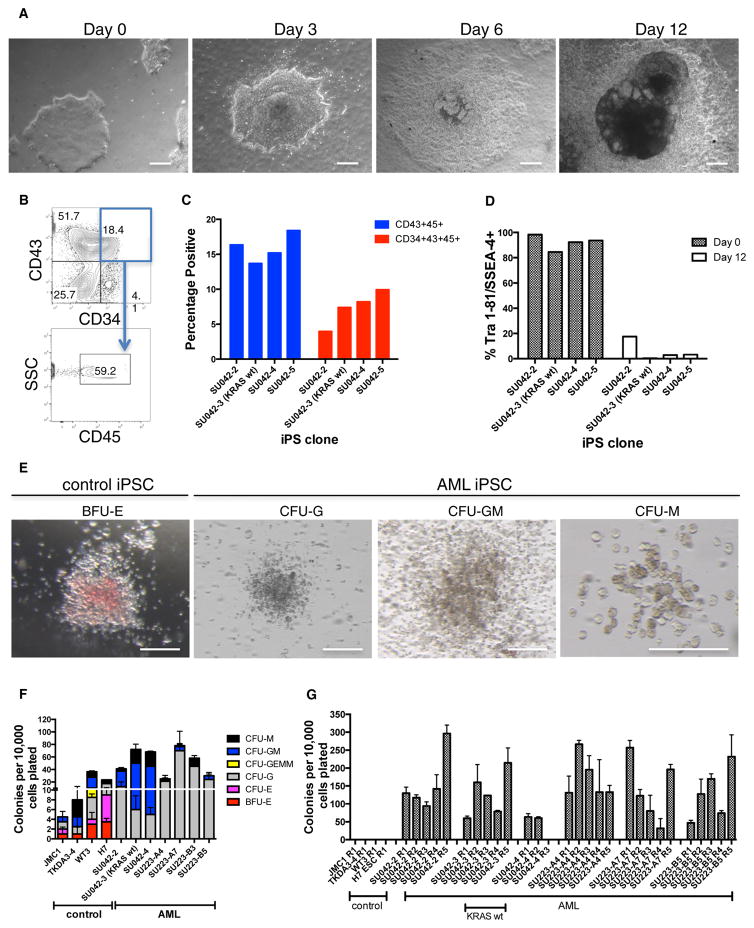

Hematopoietic Cells Differentiated from AML-iPSCs Demonstrate an Aberrant Myeloid-Restricted Phenotype and Serially Replate In Vitro

We next differentiated AML-iPSCs into hematopoietic progenitors using a co-culture feeder system with the mesenchymal mouse embryo stromal cell line C3H/10T1/2 (modified from Takayama and Eto, 2012). After 12 days, AML-iPSCs transitioned from classic iPSC morphology to sac-like structures with single cell formation (Figure 2A), typical of hematopoietic progenitors (Choi et al., 2011; Mills et al., 2014). A population of cells co-expressing CD34, CD43, and CD45 was observed, indicative of hematopoietic progenitor formation (Figures 2B, 2C, and S3C) (Choi et al., 2011; Mills et al., 2014). This population was composed of a mixture of primitive and definitive hematopoietic cells with an average of 88.1% (range 84%–92.1%) definitive hematopoietic cells when evaluated by lack of expression of the primitive hematopoietic markers CD41a and CD235a (Doulatov et al., 2013). Simultaneously, AML-iPSCs downregulated expression of pluripotent markers, demonstrating loss of pluripotency (Figures 2D and S3A). CD43+CD45+-differentiated AML-iPSCs were isolated by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) and in parallel bulk cells, and CD34+CD43− cells (that enrich for endothelial cells) (Choi et al., 2011) were plated in methylcellulose to evaluate hematopoietic colony forming potential (Figure S3B). Compared to bulk cells and CD34+CD43− cells, which failed to produce colonies, CD43+CD45+ cells were enriched for hematopoietic colony forming potential (Figures S3D and S3E). Colony formation was then compared between CD43+CD45+ cells differentiated from AML-iPSCs and control iPSCs and ESCs. CD43+CD45+ cells differentiated from controls gave rise to both myeloid and erythroid colonies (Figures 2E and 2F) while those from AML-iPSCs predominantly formed myeloid colonies. Hematopoietic colonies from AML-iPSCs demonstrated a significantly higher myeloid:erythroid cell ratio compared to controls (Figure S3F). Lastly, through serial replating assays, AML-iPSC colonies replated across multiple passages in contrast to controls, suggesting more extensive proliferative potential (Figure 2G).

Figure 2. Hematopoietic Cells Differentiated from AML-iPSCs Demonstrate an Aberrant Myeloid-Restricted Phenotype and Serially Replate In Vitro.

(A) Morphologic changes by light microscopy are shown for AML-iPSCs differentiated into hematopoietic cells. Scale bar, 100 μm.

(B and C) On day 12, cells were harvested and analyzed by flow cytometry for the presence of CD34+CD43+CD45+ hematopoietic cells as shown for SU042-2 (B) and summarized across multiple iPSC clones (C).

(D) Pluripotency marker expression was determined by flow cytometry on day 0 and 12 of differentiation.

(E and F) Differentiated CD43+CD45+ cells derived from AML-iPSCs were assessed for hematopoietic colony formation in methylcellulose. Representative colony morphology is shown (E) with results quantified (F). Scale bar, 100 μm.

(G) Serial replating of cells from (F) is shown. BFU-E, burst-forming unit erythroid; CFU-E, colony-forming unit-erythroid; G, granulocyte; GM, granulocyte, monocyte/macrophage; GEMM, granulocyte, erythroid, monocyte/macrophage, megakaryocyte; M, macrophage. Error bars represent SD.

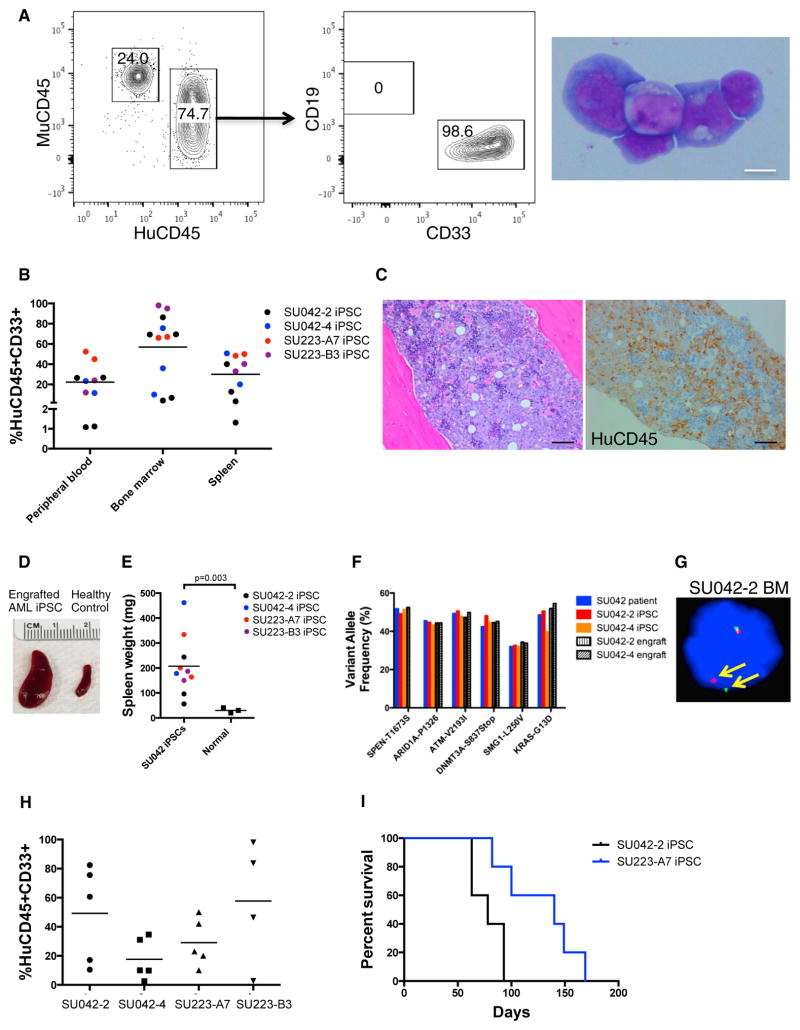

Hematopoietic Cells Differentiated from AML-iPSCs Give Rise to an Aggressive Myeloid Leukemia In Vivo

We next transplanted CD43+CD45+ hematopoietic cells from AML-iPSCs into immunodeficient NSG mice to evaluate leukemia formation in vivo. Cells were transplanted either intravenously into sublethally irradiated NSG mice or orthotopically into NSG mice harboring human ossicles, a model that gives rise to a humanized hematopoietic niche and enables efficient human hematopoietic cell engraftment (Reinisch et al., 2016). Transplantation of AML-iPSC-derived CD43+CD45+ cells from both AML patients led to an aggressive myeloid leukemia as indicated by robust human CD33+ myeloid-restricted engraftment in the peripheral blood, bone marrow, and spleen (Figures 3A and 3B). Human CD33+CD45+ cells isolated from mouse bone marrow demonstrated classic AML blast morphology (Figure 3A, right panel), and human CD45+ leukemic infiltrates were observed in mouse marrows (Figure 3C). Mice engrafted with differentiated AML-iPSCs had significantly enlarged spleens compared to non-transplanted mice (Figure 3D). Mutational analysis of engrafted cells demonstrated that they harbored mutations present in the original patient blasts and iPSC clones (Figures 3F, 3G, and S4A). Transplantation of engrafted cells into secondary recipients resulted in robust engraftment for all AML-iPSC clones (Figure 3H) and led to death from fulminant leukemia (Figure 3I), as evidenced by progressive cytopenias (Figures S4E and S4F). Notably, the engrafted leukemia cells derived from the AML-iPSCs exhibited a similar cell surface immunophenotype as the patients’ original blasts (Figures S4C and S4D). Ex vivo hematopoietic differentiation of AML-iPSCs was required for leukemia formation as undifferentiated AML-iPSCs failed to give rise to hematopoietic engraftment (Figure S4B).

Figure 3. Hematopoietic Cells Differentiated from AML-iPSCs Give Rise to an Aggressive Myeloid Leukemia In Vivo.

(A) Differentiated CD43+CD45+ cells derived from AML-iPSCs were transplanted intravenously (IV) into sublethally irradiated NSG mice or directly into humanized ossicle-bearing NSG mice with human leukemic engraftment in the bone marrow shown at 8 weeks. May-Grunwald-Giemsa staining of CD45+CD33+ cells from engrafted mouse bone marrow is demonstrated (right). Scale bar, 10 μm.

(B) Engraftment of CD43+CD45+ cells derived from the indicated AML-iPSCs is shown.

(C) H&E staining (left) and human CD45 immunohistochemistry (right) of engrafted bone marrow demonstrated leukemic infiltrates. Scale bar, 50 μm.

(D and E) Gross representative images of spleens from engrafted and non-engrafted mice are shown (D), with quantification of spleen weights (E).

(F and G) Cells isolated from the bone marrow of engrafted mice were analyzed for leukemia-associated mutations by DNA sequencing (F) and FISH for MLL rearrangement (G).

(H) Human CD45+CD33+ cells isolated from the bone marrow of engrafted mice were transplanted into secondary NSG recipients. Bone marrow evaluation for leukemia is shown at 8 weeks.

(I) Overall survival of secondary transplants is indicated with Kaplan-Meier analysis (n ≥ 5 per group).

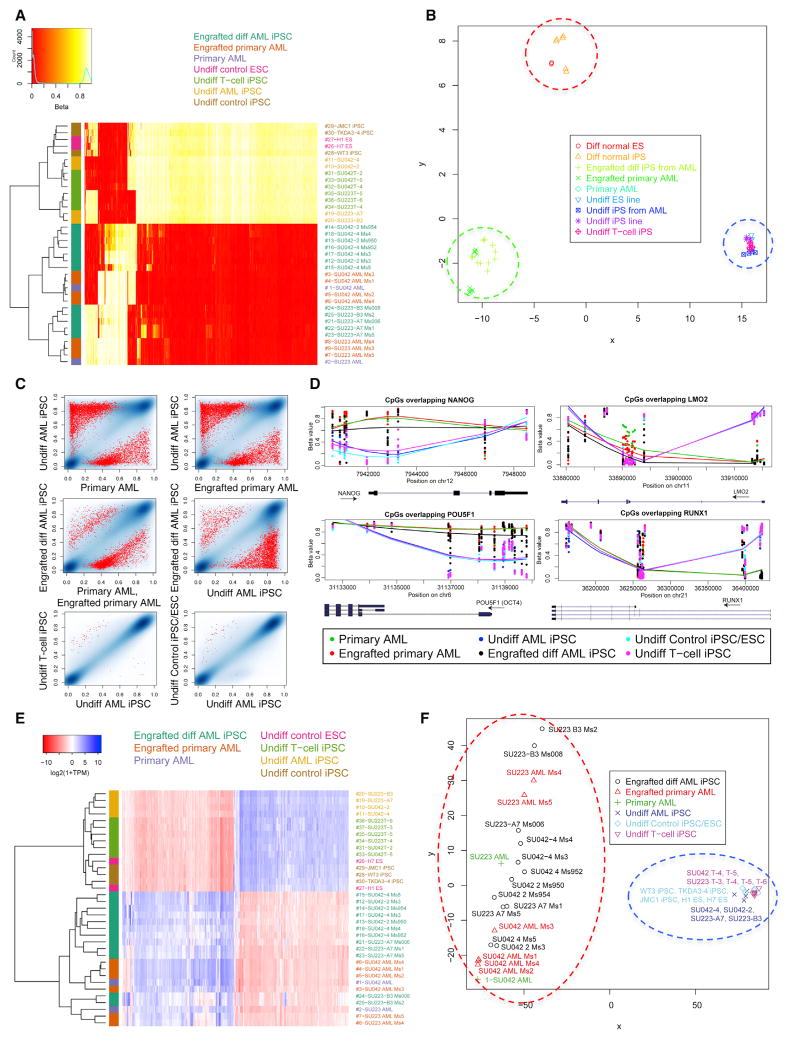

Reprogramming AML Blasts into iPSCs Resets AML-Associated DNA Methylation and Gene Expression Changes that Are Reacquired upon Hematopoietic Differentiation

Next, we sought to determine the effects of reprogramming and re-differentiation on the global epigenetic DNA methylation (Infinium 450K arrays) and gene expression (RNA-sequencing [RNA-seq]) profiles by comparing AML blasts both directly from patients and engrafted in mice, undifferentiated AML-iPSCs, engrafted leukemia cells derived from AML-iPSCs, and iPSCs and ES cells from normal controls. We additionally generated patient-matched germline controls by deriving iPSCs from T cells of both AML patients (Figure S5). Resulting T cell-iPSCs formed teratomas (Figure S5C) and did not harbor somatic leukemic mutations from patient AML cells, demonstrating that these T cell-iPSCs were not derived from the leukemic clone (Figures S5D and S5E). T cell-iPSCs harbored clonal T cell receptor rearrangements confirming that these cells were derived from T cells (Figure S5F; Table S1).

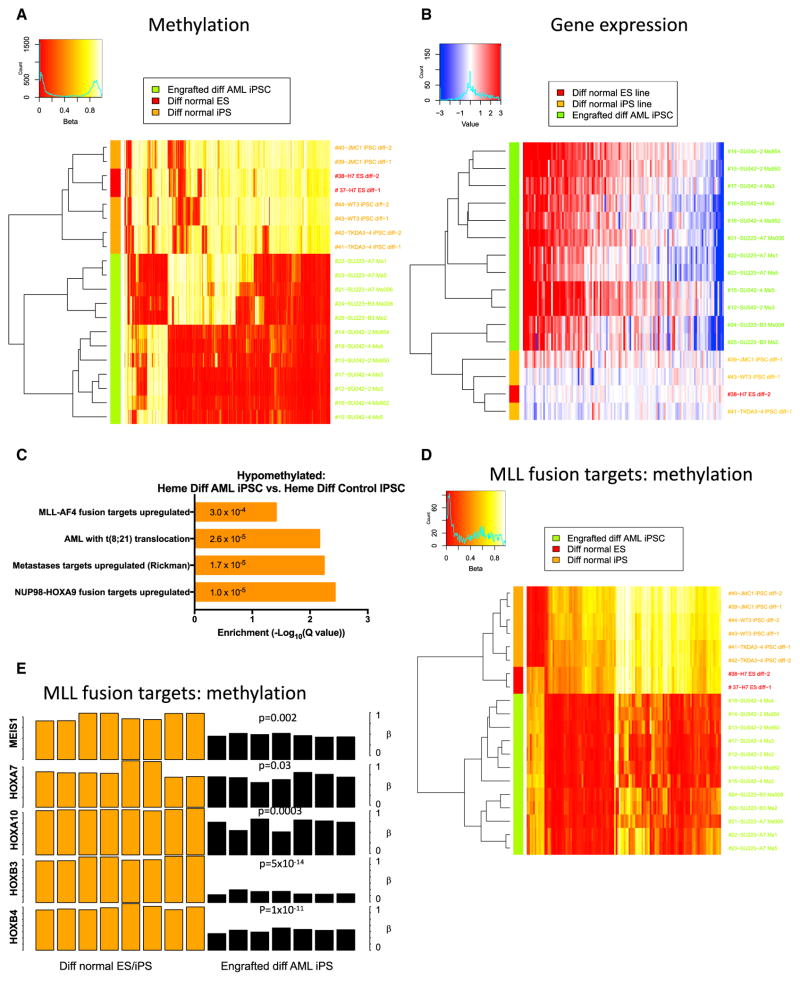

Unsupervised hierarchical clustering using the 1,000 most variable CpG sites from DNA methylation arrays demonstrated clustering of undifferentiated AML-iPSCs with T cell-iPSCs and control iPSCs/ESCs, indicating the similarity of all pluripotent populations (Figure 4A). Hematopoietic cells differentiated from AML-iPSCs clustered with primary AML cells and engrafted patient AML blasts, indicating the similarity of all leukemic populations (Figure 4A). Moreover, multi-dimensional scaling analysis separated undifferentiated iPSCs/ESCs from hematopoietic cells (first coordinate) and leukemic from non-leukemic hematopoietic cells (second coordinate) (Figure 4B). Again, differentiated AML-iPSCs grouped with primary AML cells. When assessing absolute methylation differences, undifferentiated iPSC populations were globally hypermethylated compared to primary AML and differentiated AML-iPSCs (Figure S6A). Hypermethylation mostly occurred in CpG islands and shores, while hypomethylation occurred mainly in open seas (Table S2A).

Figure 4. Reprogramming AML Blasts into iPSCs Resets AML-Associated DNA Methylation Changes that Are Reacquired upon Hematopoietic Differentiation.

(A) Methylation arrays (Infinium 450K BeadChip) were conducted on undifferentiated AML-iPSCs (undiff AML iPSC), CD43+CD45+ hematopoietic cells differentiated from AML-iPSCs and engrafted into NSG mice (engrafted diff AML iPSC), CD33+ primary AML cells (primary AML), primary AML cells engrafted into NSG mice (engrafted primary AML), undifferentiated healthy control ESC (undiff control ESC), undifferentiated healthy control iPSC (undiff control iPSC), and germline control undifferentiated iPSCs derived from AML patient T cells (undiff T cell iPSC). The 1,000 most variable CpG sites across all samples are displayed in heatmap form with unsupervised hierarchical clustering. Beta value signifies degree of methylation (red, hypomethylated; white, hypermethylated).

(B) Multi-dimensional scaling analysis (MDS) plot of methylation data demonstrates clustering according to the two most impactful coordinates. Patient-specific SNPs were filtered from this analysis.

(C) Pairwise comparisons of methylation values show individual CpGs and highlight significant DMRs. The density of blue regions is proportional to the density of individual CpG sites. Red dots represent the average β-value of CpGs within statistically significant (p < 0.01) DMRs between the sample types being compared, as identified by Bumphunter analysis.

(D) The degree of methylation (beta value) at CpG sites overlapping selected pluripotent (left) and hematopoietic (right) genes is shown comparing iPSC and AML samples. Symbols represent individual CpG loci positions; lines are smoothed Loess fits across loci for the sample types indicated by color.

(E) The 1,000 most variably expressed genes determined by RNA-seq were used for unsupervised clustering and are displayed in heatmap form. TPM, transcripts per million.

(F) Multi-dimensional scaling analysis plot of gene expression data demonstrates clustering according to the two most impactful coordinates (pluripotent versus non pluripotent axis and samples according to patient axis).

We next investigated the differentially methylated regions (DMRs) between the various populations. First, undifferentiated AML-iPSCs demonstrated significant DMRs when compared to primary AML samples (Figure 4C, top row). Distinct DMRs were also observed between undifferentiated and differentiated hematopoietic cells from AML-iPSCs (Figure 4C, right middle panel). In contrast, minimal differences were observed between all undifferentiated iPSC/ESC lines (Figure 4C, bottom row). Virtually no significant differences in DMRs were observed comparing primary AML to primary engrafted AML (data not shown).

We then characterized the specific gene regions encompassing the DMRs, focusing on genes associated with pluripotency and hematopoietic differentiation. Relative hypomethylation was seen at promoter regions of several pluripotency genes in undifferentiated AML-iPSCs in contrast to differentiated AML-iPSCs and primary AML (Figures 4D and S6B). In contrast, hematopoietic gene promoter regions were hypermethylated in undifferentiated AML-iPSCs compared to differentiated AML-iPSCs and primary AML cells (Figures 4D and S6B). Furthermore, gene ontology analysis demonstrated that undifferentiated AML-iPSCs were enriched for hypomethylation of gene sets involved in pluripotency and hypermethylation of gene sets involved in hematopoietic differentiation and leukemogenesis, including upregulated MLL gene targets (Figures S6C and S6D). Differentiated AML-iPSCs, similar to primary AML, demonstrated relative hypermethylation of pluripotency gene sets but hypomethylation of hematopoietic and leukemic gene sets.

We next performed RNA-seq analyses to determine the effect of AML reprogramming on gene expression. As with the DNA methylation profiles, all pluripotent samples possessed similar gene expression profiles, regardless of whether they were derived from AML patients or normal controls (Figures 4E and 4F). In contrast, hematopoietic cells differentiated from AML-iPSCs possessed similar gene expression profiles to primary AML samples. These findings were confirmed when all samples were analyzed by unsupervised clustering (Figure 4E) and multidimensional scaling analysis (Figure 4F). Pluripotency genes were upregulated in undifferentiated AML-iPSCs similar to control iPSCs/ESCs, while hematopoietic differentiation genes were upregulated in AML-iPSCs differentiated into hematopoietic cells, similar to primary AML samples (Figure S6E). Taken together, these results demonstrate that pluripotent reprogramming of AML samples led to global resetting of both leukemic DNA methylation and gene expression patterns that were reacquired upon hematopoietic differentiation into transplantable leukemia.

Residual Epigenetic Memory Is Not Present in AML-iPSCs and Does Not Contribute to Re-acquisition of the Leukemic Phenotype

To investigate the possibility of residual epigenetic memory contributing to the re-acquisition of the leukemic phenotype upon differentiation of AML-iPSCs, we conducted two comparisons. First, we evaluated the DMRs between undifferentiated healthy control iPSCs and AML-iPSCs. Notably, only six DMRs were found in this comparison mostly corresponding to pseudogenes or intronic regions (Table S2B). No differential expression of these genes was found by RNA-seq (Table S2C). Second, we evaluated epigenetic and gene expression differences between patient AML cells and the leukemia cells re-derived from AML-iPSCs. In this comparison, we found 716 DMRs overlapping gene promoter regions (at 1% false discovery rate [FDR]), with 659 hypomethylated and 57 hypermethylated in the re-derived leukemia. The only significant gene annotations were for sets that acquire differential H3K27me3 methylation marks during ES cell differentiation (Meissner et al., 2008). Nine of the genes with DMRs in their promoter regions were differentially expressed (Table S2D), and in only two cases was there concurrence with the changes in expression that would be anticipated based on the difference in CpG methylation—for PVT1 (a long non-coding RNA) and ADAMTS3 (ADAM metallopeptidase with thrombospondin type 1 motif 3). Thus, although the samples derived by differentiation from AML-iPSCs retained some differences in methylation from the original leukemia cells, these did not appear to significantly impact gene expression at the RNA level. These results suggest that no residual epigenetic memory was present upon AML reprogramming to iPSCs.

Differentiated Hematopoietic Cells from AML-iPSCs Display Activation of a Myeloid-Specific Aberrant MLL Gene Signature

In order to explore how AML-iPSCs reacquired the leukemic phenotype, we determined whether AML-iPSCs reactivated leukemic target genes upon hematopoietic differentiation. We performed additional methylation and gene expression analyses comparing differentiated hematopoietic cells from AML-iPSCs to differentiated hematopoietic cells from control iPSCs. Hematopoietic cells from AML-iPSCs clustered separately from control iPSC-derived cells in both methylation (Figures 4B and 5A) and gene expression analyses (Figure 5B), consistent with the idea that the mutations present in AML-iPSCs drive the leukemic phenotype only upon differentiation to hematopoietic cells. As both cases harbored MLL rearrangements that drive leukemogenesis, we investigated the activation of MLL fusion target genes. First, we found significant differences in DMRs with hypomethylation of MLL fusion targets in differentiated AML-iPSCs compared to differentiated control iPSCs (Figure 5C), whereas no difference was detected in the undifferentiated state (Table S2B). Second, when restricted to MLL fusion targets (Ross et al., 2004), differentiated AML-iPSCs exhibited hypomethylation and clustered separately when compared to differentiated control iPSCs (Figure 5D). Third, differentiated AML-iPSCs specifically exhibited hypomethylation of MLL target genes known to play key roles in leukemic pathogenesis mediated by MLL fusions, including MEIS1 and HOX family proteins (Afonja et al., 2000; Argiropoulos and Humphries, 2007) (Figure 5E). This suggests that the genetic mutations in AML-iPSCs reactivate leukemia target genes upon hematopoietic differentiation leading to the leukemic phenotype.

Figure 5. Differentiated Hematopoietic Cells from AML iPSCs Display Activation of an Aberrant MLL Gene Signature.

(A) Methylation arrays were conducted on hematopoietic cells differentiated from healthy control iPSC/ESCs and compared against hematopoietic cells differentiated from AML-iPSCs. The 1,000 most variable CpG sites across all samples are displayed in heatmap form with unsupervised hierarchical clustering.

(B) The 1,000 most variably expressed genes determined by RNA-seq were used for unsupervised clustering and are displayed in heatmap form. Expression levels were adjusted so that the mean across normal-derived samples was zero for each gene, to facilitate comparison to AML-derived samples.

(C) Gene set enrichment analyses were conducted for gene sets that were hypomethylated in the indicated pairwise comparison according to q values.

(D) CpG sites overlapping MLL fusion signature genes from Ross et al. (2004) were used for unsupervised clustering of hematopoietic cells differentiated from control and AML-iPSCs.

(E) Mean methylation values are presented for CpG sites within target genes known to be aberrantly activated by MLL fusions in leukemia for differentiated hematopoietic cells from normal iPSC/ESCs and AML-iPSCs. P values are shown for each indicated gene comparing the two populations by t test.

Lastly, while MLL rearrangements can lead to both myeloid and lymphoid leukemias, we observed an exclusively myeloid leukemic phenotype with our AML-iPSCs. We hypothesized that this could be attributed to hypomethylation and expression of myeloid-specific MLL targets. We compared differentiated AML-iPSCs to control iPSCs and found that differentiated AML-iPSCs exhibited hypomethylation and upregulation of MLL myeloid target genes (Figure S7D) (Alharbi et al., 2013; Kohlmann et al., 2005) but not lymphoid genes that were repressed. In an alternative approach, we utilized methylation data from normal human hematopoietic cell populations (Reinius et al., 2012) and demonstrated that they could be separated into lymphoid and myeloid clusters, with the majority of DMRs exhibiting hypermethylation in lymphoid cells (Figures S7A and S7B). Unsupervised clustering based on these lymphoid-hypermethylated DMRs resulted in clustering of differentiated control iPSCs separately from differentiated AML-iPSCs (Figure S7C). This myeloid-specific methylation pattern was only observed upon hematopoietic differentiation of AML-iPSCs, because no significant DMRs were found comparing undifferentiated control to AML-iPSCs (Table S2B). These results demonstrate that hematopoietic differentiation of AML-iPSCs leads to a myeloid-biased epigenetic profile.

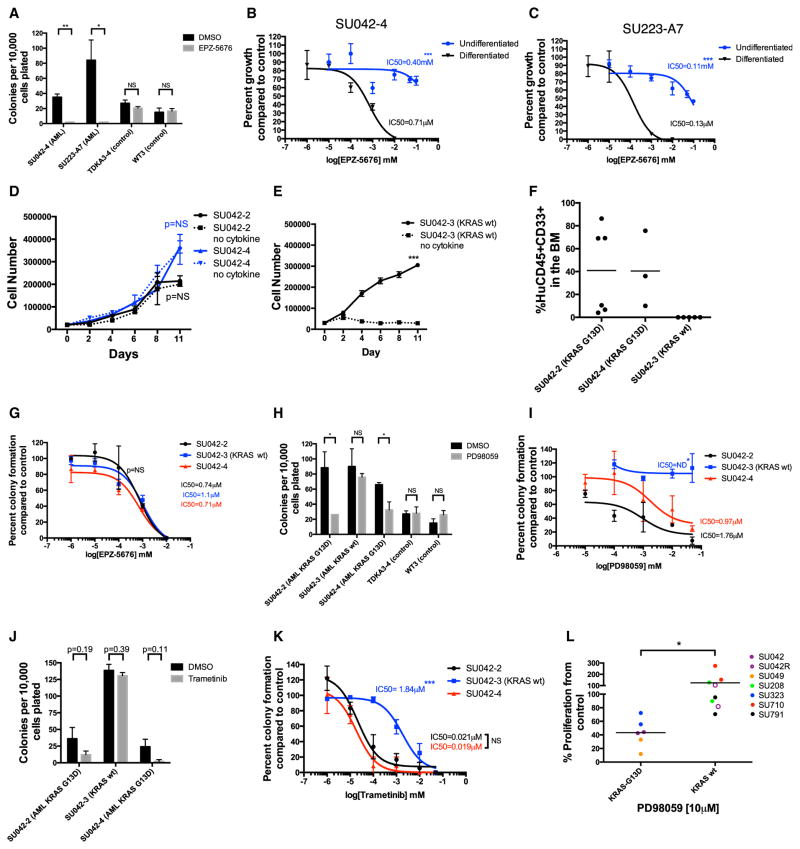

Effective Therapeutic Targeting of Genetic Mutations in AML-iPSCs Is Dependent on Differentiation Status

In vitro pharmacologic studies are difficult to conduct with primary AML cells as patient samples are often limited in quantity and leukemic blasts rapidly undergo apoptosis when placed into culture. AML-iPSCs provided an opportunity to investigate pharmacologic targeting of leukemia-specific mutations. We identified two clinically actionable mutations in our AML-iPSC lines: rearranged MLL (by DOT1L inhibitor) (Bernt et al., 2011) and KRAS G13D (by MEK inhibitors) (Irving et al., 2014). EPZ-5676 is a small molecule inhibitor of DOT1L that has demonstrated selective killing of MLL-rearranged leukemias and is in clinical trials (Daigle et al., 2011, 2013). Treatment of hematopoietic cells differentiated from MLL-rearranged AML-iPSCs with EPZ-5676 led to a dose-dependent inhibition of hematopoietic colony formation, replating potential, and nanomolar IC50s (Figures 6A–6C and S7E). In contrast, EPZ-5676 treatment had no effect on hematopoietic cells derived from normal iPSC controls (Figure 6A). Interestingly, when undifferentiated AML-iPSCs were treated with EPZ-5676, minimal growth inhibition was observed (Figures 6B and 6C), indicating that the therapeutic effect of EPZ-5676 was dependent on the differentiation state of AML-iPSCs.

Figure 6. AML-iPSCs Enable Mutation-Specific Targeting of AML Blasts and Leukemic Subclones.

(A) Differentiated CD43+CD45+ cells derived from AML-iPSCs were plated in methylcellulose in the presence of 10 μM EPZ-5676 or DMSO control and analyzed on day 14.

(B and C) Undifferentiated AML-iPSCs from SU042-4 (B) and SU223-A7 (C) were cultured in iPSC medium in the presence of increasing concentrations of EPZ-5676 or DMSO and assessed for proliferation by trypan blue staining exclusion. Differentiated CD43+CD45+ cells derived from the same AML-iPSC clone were plated in methylcellulose with similar concentrations of EPZ-5676 or DMSO.

(D and E) Hematopoietic colonies derived from AML-iPSCs were incubated in myeloid expansion media with or without cytokine (GM-CSF) for KRAS wild-type (D) and KRAS mutant clones (E). Total cell number was determined over 11 days of culture by trypan blue exclusion.

(F) CD43+CD45+ cells differentiated from AML-iPSCs from KRAS mutant and wild-type clones were transplanted intravenously into NSG mice and assessed for leukemic engraftment 8–12 weeks later.

AML-iPSCs Enable Characterization and Therapeutic Targeting of Distinct AML Subclones within an Individual Patient

Because AML-iPSCs are derived from single cells, we investigated their utility as a model for characterizing and therapeutically targeting distinct AML subclones present in an individual patient. In case SU042 (Figure 1F), we identified two distinct sub-clones that shared all leukemia-associated mutations except for KRAS-G13D, leading to generation of KRAS mutant (SU042-2, SU042-4) and KRAS wild-type (SU042-3) AML-iPSC clones. First, we observed no differences in colony formation or serial re-plating between KRAS mutant and wild-type clones (Figures 2F and 2G). Second, as GM-CSF is required for expansion of myeloid cells differentiated from normal iPSCs (Choi et al., 2009, 2011), we assessed the possibility of differential cytokine dependence. We found that KRAS mutant clones proliferated independently of GM-CSF (Figure 6D), while the KRAS wild-type clone was dependent on GM-CSF (Figure 6E). Third, we assessed whether KRAS mutant and wild-type clones displayed distinct leukemogenic properties in vivo. In contrast to KRAS mutants, hematopoietic cells differentiated from the KRAS wild-type clone failed to engraft in immunodeficient mice (Figure 6F). Fourth, we investigated the sensitivity of these clones to targeted therapies, starting with EPZ-5676. As expected, because all clones harbored the MLL rearrangement, EPZ-5676 treatment inhibited hematopoietic colony formation for both KRAS mutant and wild-type clones at similar IC50s (Figure 6G). We then investigated sensitivity to targeted KRAS pathway inhibition using MEK inhibitors that have demonstrated either pre-clinical efficacy in RAS mutant AML (PD98059) (Case et al., 2008; Hähnel et al., 2014) or clinical activity (trametinib) (Borthakur et al., 2012; Burgess et al., 2014). PD98059 inhibited colony formation, replating potential, and exhibited dose-dependent growth inhibition of KRAS mutant clones compared to controls, but had no effect on the KRAS wild-type clone (Figures 6H, 6I, and S7F). Trametinib also inhibited colony formation of KRAS mutant clones, but not the KRAS wild-type clone in a dose-dependent manner (Figures 6J and 6K). To investigate the relevance of these findings in a broader cohort of AML patients (Table S3), we treated MLL-rearranged AML patient samples, both KRAS G13D mutant and wild-type, in vitro with PD98059. KRAS G13D mutant MLL-rearranged AML cells were sensitive to PD98059, in contrast to KRAS wild-type MLL-rearranged patient samples (Figure 6L).

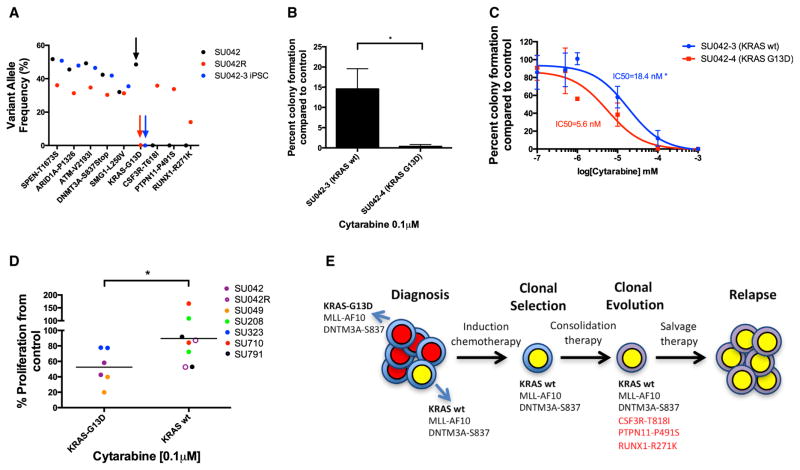

Finally, to determine the clinical relevance of these subclones, we sequenced a sample from patient SU042 obtained at relapse. Strikingly, the KRAS mutant clone, which was dominant at diagnosis, was absent at disease relapse (Figures 7A and S1A), implying relative chemotherapy resistance and competitive outgrowth of the KRAS wild-type subclone. Indeed, the KRAS wild-type clone demonstrated increased resistance to cytarabine in colony assays compared to KRAS mutant clones (Figures 7B and 7C). We then confirmed this finding in our cohort of MLL-rearranged AML patient samples; KRAS wild-type samples were more resistant to cytarabine than KRAS G13D mutant samples (Figure 7D). Thus, for patient SU042, AML-iPSCs predicted that the KRAS wild-type subclone was refractory to induction chemotherapy and underwent clonal selection and clonal evolution, leading to frank relapse (Figure 7E). In summary, AML-iPSCs facilitated the investigation of AML subclones that are both clinically relevant and have implications for development of targeted therapies for AML.

Figure 7. AML iPSCs Model Clonal Evolution and Relapse in an AML Patient.

(A) Variant allele frequencies of leukemic mutations were determined for primary SU042 patient blasts at diagnosis (SU042, black arrow), SU042-3 iPSC clone lacking the KRAS-G13D mutation from diagnosis (blue arrow), and primary SU042 patient blasts at relapse (SU042R, red arrow).

(B and C) CD43+CD45+ cells derived from AML-iPSCs were plated in methylcellulose in the presence of 0.1 μM of cytarabine, and colony formation (B) and IC50 values (C) were determined.

(D) KRAS G13D and wild-type MLL-rearranged AML patient samples were treated in liquid culture with cytarabine or DMSO control.

(E) Schematic is shown of the clonal evolution of AML patient SU042 across disease course. New mutations present at relapse are shown in red. Student’s t test was conducted for (B) and (D). Error bars represent SD. Two-way ANOVA analyses were conducted for (C). *p < 0.05

(G–I) CD43+CD45+ cells differentiated from KRAS mutant or wild-type AML-iPSCs were plated in methylcellulose in the presence of 10 μM EPZ-5676, PD98059 (a MEK inhibitor). DMSO control and colony formation (G and H) and IC50 values (I) were determined.

(J and K) CD43+CD45+ cells differentiated from AML-iPSCs were plated in methylcellulose in the presence of 0.1 μM of the MEK inhibitor trametinib, and colony formation (J) and IC50 values (K) were determined.

(L) KRAS G13D and wild-type MLL-rearranged AML patient samples were treated in liquid culture with PD98059 or DMSO control. Student’s t test was conducted for (A), (H), (J), and (L). Error bars represent SD. Two-way ANOVA analyses were conducted for (B)–(E), (G), (I), and (K). NS, non-significant. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.005.

DISCUSSION

Here, we report the successful reprogramming of primary AML patient blasts from cases with MLL rearrangements into iPSCs and demonstrate that epigenetic reprogramming resets AML-associated DNA methylation changes. The generation of AML-iPSCs that retain patient-specific leukemia mutations enables unique opportunities to model and investigate leukemic disease through the epigenetic reprogramming of AML cells. In particular, this approach allows investigation of the relative contribution and interdependence of leukemic genetic and epigenetic programs. Reprogramming AML cells to pluripotency resets AML-associated DNA methylation changes. However, our findings suggest that epigenetic resetting of leukemic behavior is dependent on the differentiation context of the cell. First, differentiation of AML-iPSCs into hematopoietic cells led to leukemic reacquisition (Figures 2 and 3), while non-hematopoietic lineages did not form tumors (Figure S2). Second, hematopoietic cells differentiated from AML-iPSCs exhibited similar DNA methylation and gene expression profiles to the primary AML blasts but distinct from control iPSCs (Figure 4). It should be noted that hematopoietic differentiation of our AML-iPSCs yielded primarily definitive hematopoietic cells, however, phenotypic primitive hematopoietic cells were also present. Because primitive hematopoietic cells are often observed upon iPSC differentiation, our results should be interpreted in this context when comparing iPSC-derived hematopoietic cells to primary hematopoietic cells. Nevertheless, these findings in MLL-rearranged AML demonstrate that epigenetic resetting is not sufficient to override the leukemic genetic program when AML-iPSCs are differentiated into the hematopoietic lineage, indicating that leukemic mutations are sufficient to drive leukemogenesis.

While reprogramming AML cells to pluripotency is not necessarily unexpected, the finding that leukemic behavior is reacquired during hematopoietic differentiation, but not differentiation to other tissue types is striking. Our findings demonstrate that the presence of genetic mutations in combination with the appropriate differentiation context and cell type drives pluripotent cells to malignant transformation. Indeed, despite the presence of known panoncogenic driver mutations (e.g., MLL, ARID1A, and RAS), oncogenesis was only initiated upon hematopoietic differentiation of AML-iPSCs. What factors drive this leukemic re-emergence? One explanation is that residual epigenetic memory is present upon reprogramming AML cells to iPSCs. However, methylation profiles were virtually identical between undifferentiated AML-iPSCs and control iPSCs (Figures 4B and 4C; Table S2B), suggesting this is not the case. A second explanation is that the genetic mutations present in AML-iPSCs reactivate mutation-specific target genes upon hematopoietic differentiation. Supporting this hypothesis, we found that reactivation of aberrant, myeloid-specific MLL target genes in AML-iPSCs was associated with reacquisition of leukemic behavior upon hematopoietic differentiation (Figure 5).

While MLL rearrangements can drive both myeloid and lymphoid leukemogenesis, only myeloid leukemias with upregulation of myeloid MLL target genes were generated from these AML-iPSCs (Figures S7C and S7D). The absence of lymphoid leukemias is likely explained by two observations. First, it is well known that certain MLL rearrangements (e.g., MLL-AF9 or MLL-AF10, found in both AML samples here) are predominantly found in AML, as compared to acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) (Collins and Rabbitts, 2002). Second, in addition to MLL rearrangements, both AML-iPSC lines harbored other mutations that are primarily associated with myeloid leukemias and drive aberrant myeloid differentiation. For example, SU223 cells harbored a FLT3 internal tandem duplication (ITD), which is highly prevalent in AML, and has not been observed in B cell ALL (Armstrong et al., 2004; Levis and Small, 2003). SU042 cells harbored a nonsense mutation in DNMT3A, which is found in 20%–30% of all AML patients (Ley et al., 2010) and is known to drive myeloid leukemogenesis (Yang et al., 2015). Thus, it is likely that these additional mutations contribute to myeloid leukemic development in these AML-iPSCs.

Indeed, iPSCs have been successfully derived from several human cancers (Amabile et al., 2015; Kotini et al., 2015; Lee et al., 2015; Miyoshi et al., 2010; Stricker et al., 2013; Suvà et al., 2014). In glioblastomas, pluripotent reprogramming led to resetting of cancer-specific methylation marks (Stricker et al., 2013). However, differentiated neural progenitors from glioblastoma iPSCs retained malignant potential, implying that epigenetic reprogramming was insufficient to override the genetic mutations in this tumor type. In contrast, iPSCs generated from chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) led to reversal of leukemia-specific DNA methylation marks and normal hematopoietic differentiation in vitro despite the presence of the BCR-ABL oncogene (Amabile et al., 2015). Lastly, recent attempts have been made to generate iPSCs from B cell ALL patients, of which several harbored MLL rearrangements (Muñoz-López et al., 2016). Despite use of multiple modalities, B-ALL cells were unable to be reprogrammed to pluripotency. The successful generation of AML-iPSCs from MLL-rearranged samples here is likely due to differences in the genetic and chromosomal composition between the AML and B-ALL samples utilized. These studies and our current work suggest that epigenetic reprogramming may be dependent on tumor type and the specific mutations present.

Lastly, our work highlights a novel application of cancer-derived iPSCs: the ability to study the properties and therapeutic targeting of distinct genetic subclones. To our knowledge, this is the first report demonstrating the use of iPSCs to investigate clonal heterogeneity and cancer evolution. Moreover, while previous studies have investigated and modeled clonal progression in AML, the major limitation of these studies is that they were primarily descriptive. The physical separation and functional characterization of individual subclones in AML patients is essential to design rational therapies that are able to eradicate subclones that evolve after therapy. Here, we demonstrate in a proof of concept study that AML-iPSCs can capture the clonal heterogeneity of an individual patient and predict clonal response to therapy and disease evolution. Through iPSC reprogramming, we identified two distinct subclones (KRAS mutated and KRAS wild-type) in one AML patient, enabling their separation and functional characterization. These subclones demonstrated distinct cytokine dependence in vitro, differential engraftment in vivo, and differential sensitivity to MEK inhibitors (Figure 6). Interestingly, in this patient, therapeutic interrogation of iPSC subclones predicted the pattern (KRAS wild-type clonal outgrowth) and mechanism (cytarabine resistance) of clonal relapse (Figure 7). While isogenic AML-iPSC lines were utilized, these conclusions could be further supported by demonstrating similar findings through engineering the KRAS mutation into the KRAS wild-type cells.

Generation of patient-specific AML-iPSCs for personalized profiling of genetic subclones is not likely to be practical for real-time clinical decision-making given the time needed to generate iPSCs and the potential for some AML patient cells to be refractory to reprogramming. However, therapeutic discoveries using AML-iPSCs can be explored in AML patients with similar mutation profiles yielding novel insights that can be applicable to a larger subset of patients. Here, we identified differential sensitivity to cytarabine in AML-iPSC subclones and expand these findings into KRAS wild-type MLL-rearranged AML patients (Figure 7D). This finding has not previously been reported and has potential clinical implications for this subgroup. In summary, these observations highlight the need for consideration of clonal heterogeneity in selecting targeted therapies and the utility of this AML-iPSC approach to facilitate subclone analysis, targeting, and prediction of subclonal relapse.

STAR★METHODS

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Anti-human CD3 PE | BD Biosciences | Cat# 555340, clone HIT3a; RRID: AB_395746 |

| Anti-human CD19 APC | BD Biosciences | Cat# 555415, clone HIB19; RRID: AB_398597 |

| Anti-human CD33 PE | BD Biosciences | Cat# 555450, clone WM53; RRID: AB_395843 |

| Anti-human CD34 BV421 | BD Biosciences | Cat# 562577, clone 8G12 |

| Anti-human CD43 APC | BD Biosciences | Cat# 560198, clone IG10; RRID: AB_1645460 |

| Anti-human CD45 PeCy7 | BD Biosciences | Cat# 557748, clone H13; RRID: AB_396854 |

| Anti-human CD235a PeCy5 | BD Biosciences | Cat# 559944, clone GA-R2; RRID: AB_397387 |

| Anti-human SSEA-4 V450 | BD Biosciences | Cat# 561156, clone MC813-70; RRID: AB_10896140 |

| Anti-human Tra 1-81 A488 | Biolegend | Cat# 330710; RRID: AB_2561742 |

| Anti-mouse CD45.1 PeCy7 | BD Biosciences | Cat#560578, clone A20; RRID: AB_1727488 |

| Anti-MAP2 | Sigma | Cat# M9942, clone HM-2; RRID: AB_477256 |

| Anti-synapsin | Sigma | Cat# S193, polyclonal; RRID: AB_261457 |

| Biological Samples | ||

| Human AML cells (SU042, SU042R, SU223, SU049, SU208, SU323, SU710, SU791) | Majeti lab tissue bank | N/A |

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| EPZ-5676 | Selleckchem | Cat# S7062 |

| PD98059 | Selleckchem | Cat# S1177 |

| Trametinib | Selleckchem | Cat# S2673 |

| Thiazovivin | Selleckchem | Cat# S1459 |

| CHIR99021 | Selleckchem | Cat# S1263 |

| IWR-1 | Sigma | Cat# I0161 |

| Y-27632 | StemCell Technologies, Inc. | Cat# 72302 |

| Methocult H4435 | StemCell Technologies, Inc. | Cat# 04435 |

| Essential 8 medium | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# A1517001 |

| Critical Commercial Assays | ||

| Cytotune iPS 2.0 Sendai Reprogramming Kit | ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat# 16517 |

| PSC 4-marker immunocytochemistry kit | ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat# A24881 |

| T cell clonality assay | Invivoscribe | 12000010 |

| Deposited Data | ||

| Raw and analyzed DNA methylation and RNA-seq data | This paper | GEO: GSE89778 |

| Experimental Models: Cell Lines | ||

| C3H/10T1/2 cells | American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) | Cat# CCL-226 |

| H1 cells | Vittorio Sebastiano lab, via WiCell | N/A |

| H7 cells | Vittorio Sebastiano lab, via WiCell | N/A |

| M2-10B4 cells | ATCC | Cat# CRL-1972 |

| JMC1 cells | Joseph Wu lab, Stanford Cardiovascular Institute Biobank, this publication | N/A |

| WT3 cells | Joseph Wu lab, Stanford Cardiovascular Institute Biobank, Ebert et al., 2014 | N/A |

| HEK293T cells | ATCC | Cat# CRL-3216 |

| TKDA3-4 cells | Takayama et al., 2010 | |

| Experimental Models: Organisms/Strains | ||

| Mouse: NOD.Cg-Prkdcscid Il2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ (NSG) mice | Jackson Laboratory | Cat# 005557 |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| Ngn2 plasmid (pTet-O-Ngn2-puro) | Zhang et al., 2013 | Addgene #52047 |

| rtTA plasmid (FUW-M2rtTA) | Hockemeyer et al., 2008 | Addgene #20342 |

| pRSV-REV plasmid | Standard plasmid | Addgene #12253 |

| pVSVG plasmid (pMD2.G) | Standard plasmid | Addgene #12259 |

| pMDLg/pRRE | Standard plasmid | Addgene #12251 |

| Sequence-Based Reagents | ||

| Primers for targeted amplicon sequencing of leukemia-associated mutations | Corces-Zimmerman and Majeti, 2014 | N/A |

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| GraphPad Prism version 6.0 | GraphPad Software | N/A |

| CytoVision® imaging software | Leica | N/A |

| Sailfish (gene expression algorithm) | Patro et al., 2014 | N/A |

| Bioconductor version 3.0 | R version 3.2.3 | N/A |

| Minfi version 1.12.0 | Aryee et al., 2014 | N/A |

| Bumphunter version 1.6.0 | Jaffe et al., 2012 | N/A |

| GenomicRanges version 1.18.4 | Lawrence et al., 2013 | N/A |

| Qvalue version 1.43 | Storey and Tibshirani, 2003 | N/A |

| Other | ||

| Sequence data, analyses, and resources related to DNA methylation and RNA-seq analysis of AML/control iPSCs and AML primary samples | This paper | GEO: GSE89778 |

| Gene annotations: TxDb.Hsapiens.UCSC.hg19.knownGene annotation package | UC Santa Cruz knownGene tables (human genome hg19 assembly) | N/A |

| Illumina iGenomes reference transcriptome (based on UCSC known genes annotation and hg19 human genome reference | UC Santa Cruz known genes annotation | ftp://igenome:G3nom3s4u@ussd-ftp.illumina.com/Homo_sapiens/UCSC/hg19/Homo_sapiens_UCSC_hg19.tar.gz |

CONTACT FOR REAGENT AND RESOURCE SHARING

The Lead Contact (Mark Chao at Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA; mpchao@stanford.edu) holds responsibility for responding to requests and providing reagents and information.

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Primary human samples

AML samples were obtained according to Institutional Review Board (IRB)-approved protocols (Stanford IRB no. 18329 and 6453) after informed consent and reprogramming of AML samples conducted under Stanford IRB no. 28197. Sample description is found in Figure S1A and Table S3.

Animal models: transplantation of AML iPSCs into immunodeficient mice for teratoma and leukemic formation

For teratoma formation, 5×105 to 1×106 undifferentiated AML-iPSCs were injected subcutaneously into healthy, previously untreated adult female NOD.Cg-Prkdcscid Il2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ (NSG) mice age 6–10 weeks (Jackson Laboratory, ME). Subcutaneous masses were excised 8–12 weeks later, fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for 3 days and then transferred to 100% ethanol. Masses were then processed for hematoxylin and eosin staining and teratoma formation assessed by a qualified veterinary pathologist at the Stanford University Veterinary Service Center. These samples were blinded from the pathologist. For leukemic transplantation, AML-iPSCs were differentiated into CD43+CD45+ hematopoietic cells. On day 12, 3×105 to 1×106 hematopoietic cells differentiated from AML-iPSCs with carrier C3H/10T1/2 cells were transplanted intravenously into adult NSG mice sublethally irradiated with 200 rads (Faxitron, X-ray irradiation). Primary patient AML cells were also transplanted intravenously into sublethally irradiated adult NSG mice. Assessment of AML-iPSC or primary AML engraftment was performed 8–12 weeks post-transplantation. For the majority of in vivo experiments, at least five mice were used per experimental group. For sample sizes less than five, individual data points are displayed. Randomization of mouse studies was not employed. Blinding was not performed with the exception of teratoma analysis as above. All animal studies were conducted in compliance with ethical regulations under the IACUC protocol no. 28337 and conform to the relevant regulatory standards.

METHOD DETAILS

Cell lines and media

C3H/10T1/2, H1, H7, and M2-10B4 cells were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (VA). Normal control wild-type iPSCs were generated using Sendai virus containing human SKOM (Sox2, Klf4, Oct3/4, and c-Myc) reprogramming factors. These wild-type iPSCs include WT3 (derived from fibroblasts of a 20 year old male) (Ebert et al., 2014) and JMC1 (derived from peripheral blood mononuclear cells of a 30 year old male). TKDA3-4 iPSCs were generated via retrovirus containing SKOM factors from fibro-blasts of a 36-year-old male (Takayama et al., 2010). Regarding cell line authentication, all cell lines and AML-iPSCs used have been tested negative for mycoplasma by PlasmoTest (InvivoGen). M2-10B4 conditioned medium: M2-10B4 cells were cultured in Myelocult H5100 media (StemCell Technologies, Canada) for 3–5 days under full confluency. Supernatant was harvested and supplemented with 100ng/ml recombinant human FLT3 ligand, 100ng/ml stem cell factor, 20ng/ml IL-3, 20ng/ml IL-6, and 1nM StemReginin 1 for use. All cytokines were purchased from Peprotech (NJ) with the exception of StemReginin 1 (Cellagen Technology, CA). Hematopoietic differentiation medium: IMDM media (Life Technologies, CA) with 15% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 10% insulin/transferrin/selenite solution (Life Technologies), 50mg/ml ascorbic acid (Sigma-Aldrich, United Kingdom), 450 μM α-monothioglycerol (Sigma-Aldrich), and 20ug/ml recombinant human VEGF (Peprotech).

C3H/10T1/2 feeder cell medium: Alpha MEM media prepared from powder (Life Technologies) with 10% FBS, and 100U/ml penicillin/streptomycin (Life Technologies).

Myeloid expansion medium: Alpha MEM media with 10% FBS, 0.1mM monothioglycerol (Sigma-Aldrich) and 200ng/ml human GM-CSF (Peprotech).

Antibodies and inhibitors

The following antibodies were purchased from BD Biosciences (CA): Anti-human CD3 PE (clone HIT3a), CD19 APC (clone HIB19), CD33 PE (clone WM53), CD34 BV421 (clone 8G12), CD43 APC (clone IG10), CD45 PeCy7 (clone H130), CD235a PeCy5 (clone GA-R2), SSEA-4 V450 (clone MC813-70), anti-mouse CD45.1 PeCy7 (clone A20). Anti-human Tra 1-81 A488 was purchased from Biolegend (CA). EPZ-5676, PD98059, and trametinib were purchased from Selleck Chemicals (TX).

Generation of iPSCs from patient AML cells

Primary AML cells were cultured in M2-10B4 conditioned medium for several days at 37°C at 5% O2 to ensure active proliferation. In our experience, a doubling time of 24–48 hr is an ideal proliferation rate for reprogramming. Cell viability should be greater than 90% prior to proceeding with reprogramming. Cells were then transduced with Sendai virus containing the Yamanaka reprogramming factors human Klf4, Oct3/4, Sox2, and c-Myc under the manufacturer’s protocol (Cytotune 2.0, reprogramming PBMCs, ThermoFisher Scientific) with additional modifications described. Primary AML cells were cultured in M2-10B4 conditioned medium at a density of 2×106 cells/mL (2×105 cells per 100 μl) in a 96 well plate. On day 0, cytotune sendai virus was added at an MOI of 2 with cells kept at 37°C at 5% O2 for 6–12 hr. On day 1, 200 μL of fresh M2-10B4 conditioned medium was added and the cells were centrifuged at 1250 RPM for 5 min at room temperature. Cells were then resuspended in 400 μL of M2-10B4 conditioned medium in a 24 well plate coated with matrigel (Corning, NY). On day 2, media was changed with the addition of 250 μM sodium butyrate (Sigma-Aldrich) in a total volume of 400 μl. On day 4, 50% of medium was replaced with M2-10B4 medium without cytokines. On day 7, media was changed to 1:1 ratio of M210B4 medium to E7 reprogramming media (Life technologies) with 250 μM sodium butyrate. Media was changed every 2–3 days (with 50% fresh E7 medium) until formation of colonies with iPSC morphology was observed (day 12–25). Upon formation of colonies, media was changed to E8 media (Life technologies) without sodium butyrate and resulting colonies were expanded for downstream applications. IPSC colonies were passaged with 0.5mM EDTA. Once iPSC colonies were expanded, subsequent cultures were maintained at 37°C in normal O2 conditions. Timing of media changes is described in Figure S1B.

Generation of T cell iPSCs

CD3+CD45+side scatter low T cells were isolated by FACS and stimulated with CD3/28 beads (Life Technologies) and transduced with reprogramming factors via Sendai virus vectors as previously described (Nishimura et al., 2013). As noted, transduced cells were seeded onto murine embryonic fibroblasts (MEF) feeder cells and cultured in T cell medium (RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% human AB Serum, 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 ng/ml streptomycin), which was gradually replaced with human iPSC medium (Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium/F12 supplemented with 20% knockout serum replacement, 2 mM L-glutamine, 1% nonessential amino acids, 10 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, and 5 ng/ml basic fibroblast growth factor). Formed iPSC colonies were picked up and maintained in Essential 8 medium.

Hematopoietic differentiation of iPSCs

Control and AML-derived iPSCs, as well as control ESCs, were differentiated into hematopoietic progenitors through co-culture of iPSCs/ESCs with the mesenchymal mouse embryo stromal cell line C3H/10T1/2 modified from (Takayama and Eto, 2012) in the presence of hematopoietic differentiation medium. Modifications to this protocol are as described. Notably, undifferentiated iPSCs were co-cultured at 37°C in 5% O2 conditions for six days onto 10cm petry dishes with fully confluent adherent C3H/10T1/2 cells in hematopoietic differentiation media with successive media changes on days 3 and 6. On day 6 cells were then transferred to normal O2 conditions with an additional media change on day 9. On day 12, differentiated cells were harvested first with 100U/ml collagenase II solution (GIBCO, Gaithersburg, MD) at 37°C for 45 min and then 0.05% trypsin/EDTA at 37°C for 15 min. Cells were then vigorously pipetted to create a cell suspension, passed through a 25 gauge needle, and filtered through a 100 μm sterile filter and allowed to incubate for one hour at 37°C at normal O2. Detached cells were then utilized for downstream experiments including in vivo transplantation or cell sorting of hematopoietic progenitors.

Cardiac Differentiation of Human iPSCs

Human iPSC-CMs were generated as described in detail previously (Lian et al., 2012) with the following modifications. Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC) were grown to 90% confluency in E8 medium, after which iPSCs were treated with 6 μM CHIR99021 (Selleck Chemicals) for 2 days, recovered in insulin-minus RPMI+B27 for 24 hr, treated with 5 μM IWR-1 (Sigma) for 2 days, then insulin minus medium for another 2 days, and finally switched to RPMI+B27 plus insulin medium. Beating cells were observed at day 9–11 after differentiation. iPSC-CMs were re-plated and purified with glucose-free medium treatment for two to three rounds. Typically, cultures were more than 80% pure by FACS assessment of TNNT2+ cells after purification. Cultures were maintained in a 5% CO2/air environment.

Neuronal differentiation of iPSCs

Human iPSCs were dissociated using accutase (Innovative Cell Technologies, CA) and plated as single cells in E8 medium supplemented with ROCK inhibitor Y-27632 (10μM, StemCell Technologies, Inc.) on matrigel to a final density of density of 20,000–30,000 cells per cm2. Immediately after attachment, cells were infected with lentivirus for Ngn2-puro and rtTA expression. After 24 hr (day 0), transgene expression was induced by replacing half of the medium with N2/B27 medium (DMEM/F12, N2 supplement (Life Technologies), B27 supplement (Life Technologies), 10 μg/ml insulin (Life Technologies), and 2 mg/l Doxycycline). Selection was carried out for 48 hr (day 1 and 2) in N2/B27 medium with 2 μg/ml puromycin. On day 4, induced neuronal (iN) cells were washed with 0.5 mM EDTA in PBS and harvested with accutase. Dissociated cells were then re-plated on primary glia cultures in neurobasal/B27 medium (DMEM/F12, B27 supplement, 2mM Glutamax (Life Technologies), 200ng/ml mouse laminin (Sigma-Aldrich), 10 ng/ml NT3 (Prepro-Tech), 2 mg/l Doxycycline (Sigma-Aldrich), and 2 μM cytosine arabinose (Ara-C, Sigma-Aldrich). After day 4, iN/glia co-cultures were maintained in neurobasal/B27 medium with 1/2 medium changes every 2–4 days.

Hematopoietic colony formation

CD43+CD45+ hematopoietic cells differentiated from iPSCs or ESCs were plated in cytokine-enriched Methocult H44435 (StemCell Technologies, Inc., Canada) and analyzed for colony formation after 14 days at 37°C. For serial replating of cells, Methocult was solubilized with PBS and 10,000 cells were plated into Methocult and analyzed after 14 days at 37°C.

Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization

Cell cultures were harvested by standard cytogenetic methodologies including mitotic arrest, hypotonic shock and fixation. In brief, cells were incubated with hypotonic solution (0.075M KCL) at 37°C in a water bath for 20 min. Fixative solution (3:1 parts methanol: glacial acetic acid) at a 1:10 dilution was then added, spun down, resuspended in fixative solution, and incubated at room temperature for 30 min. Cytospin slides were then prepared with the cell suspension and centrifuged for 5 min at 500 RPM. Metaphase slide preparations were then analyzed and karyotyped by the GTW banding method. Interphase fluorescence in situ hybridization was performed either on cells prepared by standard cytogenetic harvest or on Cytospin cell preparations using an MLL breakapart probe (Abbott Molecular, IL), which identifies rearrangement of the MLL gene at chromosomal band 11q23. Slides were analyzed by CytoVision® imaging software (Leica, Germany) by the Stanford Hospital Cytogenetics Laboratory.

May Gruenwald-Giemsa Staining

Cells were prepared on glass microscope slides by cytospin and fixed in absolute methanol for 5 min at room temperature and then stained for 20 min with 1:1 ratio of May Gruenwald solution (Sigma-Aldrich):phosphate buffer pH 6.4, washed in H2O and transferred to 1:9 ratio of Giemsa solution (Sigma-Aldrich): phosphate buffer for 20 min and then washed.

Virus production

Lentiviruses for exogenous transcription factor expression were produced in HEK293T cells by co-transfection of the Ngn2 plasmid (Zhang et al., 2013) (pTet-O-Ngn2-puro, 12.5 μg) or the reverse tetracycline-controlled transactivator (rtTA) plasmid (Hockemeyer et al., 2008) (FUW-M2rtTA, 12.5μg) with the helper plasmids pRSV-REV (3.125μg), pMDLg/pRRE (6.25 μg), and vesicular stomatitis virus G protein expression vector (pVSVG, 3.125 μg) in poly-L-ornithine-coated 10 cm dishes using 75 μl linear polyethylenimine (PEI, 1 μg/μl, Polyscience Inc., PA). Plasmid DNA and PEI were separately pre-diluted in 500 μl DMEM each, mixed, incubated for 15 min, and added dropwise to the cells cultured in DMEM supplemented with non-essential amino acids (100μM each), sodium pyruvate (1mM), and 10% cosmic calf serum (CCS, Healthcare, UT). After 6–8 hr the complete media was changed and virus particles were concentrated from the supernatant at 24 and 48 hr after infection by ultracentrifugation.

Immunofluorescence

Immunofluorescence staining of iPSCs with pluripotent markers was performed exactly according to manufacturer instructions using the PSC 4-marker immunocytochemistry kit (ThermoFisher Scientific). Immunofluorescence staining was performed on iN/glia co-cultures using the following antibodies mouse anti-MAP2 (Sigma-Aldrich, 1:500, E028 rabbit anti-synapsin (E028, 1:1000), Alexa 488- and Alexa 555-conjugated secondary antibodies (Invitrogen, 1:5000). Briefly, cultured iN cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 10 min, washed two times with PBS, and permeabilized in 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS for 5 min. Cells were blocked in PBS containing 5% CCS, 0.5% BSA, and 0.02% NaN3 for 1 hr. Primary antibodies were applied over night at 4°C and cells were subsequently washed in PBS for three times. Secondary antibodies were applied for 1 hr at room temperature washed in PBS for three times. Cell nuclei were counterstained with 0.1μg/ml DAPI (Thermo Scientific) in PBS for 10 min. Immunostaining of differentiated iPSC-CMs was performed using cardiac troponin T (cTnT, Thermo Scientific), sarcomeric α-actinin (Clone EA-53, Sigma), and DAPI (Thermo Scientific) as previously described(Sun et al., 2012). Labeled cells were examined and imaged by confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss, LSM 510 Meta) at 20 × to 63 × objectives as appropriate.

Electrophysiology

For studies on induced neurons, whole-cell patches were established at room temperature using MPC-200 manipulators (Sutter Instrument) and a Multiclamp 700B amplifier (Molecular Devices) controlled by Clampex 10 Data Acquisition Software (Molecular Devices). Pipettes were pulled using a PC-10 puller (Narishige) from borosilicate glass (o.d. 1.5 mm, i.d. 0.86 mm; Sutter Instrument) to a resistance of 2–3 MOhm and were filled with internal solution for voltage-clamp containing 135mM CsCl2, 10mM HEPES, 1mM EGTA, 1mM Na-GTP, and 1mM QX-314 (pH adjusted to 7.4, 310 mOsm) or, for current-clamp containing 130mM KMeSO3, 10mM NaCl, 10mM HEPES, 2mM MgCl2, 0.5mM EGTA, 0.16mM CaCl2, 4mM NaATP, 0.4mM NaGTP, and 14mM Tris-creatine phosphate (pH adjusted with NaOH to 7.3, 310 mOsm). The bath solution contained 140mM NaCl, 5mM KCl, 2mM CaCl2, 1mM MgCl2, 10mM glucose, and 10mM HEPES-NaOH (pH 7.4). An extracellular concentric bipolar electrode (FHC) was placed on the culture monolayer at a distance of approximately 80 μm from the recording cell. Evoked responses were induced by injecting a 1-ms, 1-mA current through an Isolated Pulse Stimulator 2100 (A-M Systems) connected to the stimulating electrode. For voltage-clamp experiments, the holding potential was −70 mV. The AP-generation experiments on iN cells were performed at approximately −60 mV by using a small holding current to adjust the membrane potential accordingly.

Cardiomyocyte contractility and calcium handling

Contractility and calcium handling studies performed on differentiated cardiomyocytes from wild-type and AML iPSCs were conducted as previously described (Wu et al., 2015). Briefly, for spontaneous calcium transient analysis, beating iPSC-CMs around day 30 of differentiation were dissociated with accutase and replated on matrigel (BD bioscience) pre-coated imaging chambers. After recovery, cells were loaded with 5 μM Fluo-4 AM in Tyrode’s solution (140 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 5.4 mM KCl, 1.8 mM CaCl2, 10 mM glucose, and 10 mM HEPES pH = 7.4 with NaOH at RT) for 10 min at 37°C. Loaded cells were then rinsed 3X with Tyrode’s solution, and calcium transient were recorded by a Carl Zeiss LSM 510 Meta confocal with 63X oil immersed objective (Plan-APO 63x/1.40 Oil DIC) in line-scanning mode. Calcium imaging data were further analyzed with a custom-made IDL script. For traction force microscopy, single beating iPSC-CMs were plated on hydrogel coated imaging chambers embedded with fluores-cent microspheres (Life Technology). The displacement of the fluorescent beads were recorded as videos at 30 fps with 60X oil immersed objective (Plan-APO 63x/1.40 Oil DIC) on a Nikon Spinning Disk confocal microscope. The videos were further analyzed using a particle image velocimetry script in MATLAB (MathWorks) as previously described (del Álamo et al., 2013).

Targeted Sequencing of Leukemia Mutations

Targeted Amplicon Sequencing was performed as previously described to identify leukemic mutations (Corces-Zimmerman and Majeti, 2014). The variant allele frequency was defined as (mutant read #)/(germline read # + mutant read #). Read counts and primer pairs from all assays are available upon request. Each locus was sequenced to high depth (> 500 fold coverage for all assays). To determine the approximate threshold of detection for each PCR assay, control experiments were conducted on admixtures of gDNA from the given leukemia patient and from normal control DNA from unrelated individuals. Admixtures of 2%, 1%, and 0.5% were used. Primer pairs that did not closely follow a linear increase in variant allele frequency in these assays were redesigned.

Humanized ossicle formation and transplantation

Human BM samples were obtained according to Institutional Review Board (IRB)-approved protocol (MUG Graz IRB no. 19–252). BM-mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) were isolated and expanded in α-modified minimum essential medium (α-MEM; Sigma-Aldrich) exchanging FBS with 10% pooled human platelet lysate (pHPL) (Reinisch et al., 2015; Schallmoser et al., 2007). Purity of isolated MSC was routinely tested by flow-cytometry following suggested guidelines (Dominici et al., 2006). Humanized ossicles were formed as previously described (Reinisch et al., 2015). Briefly, 2×106 BM-MSC were admixed with 300 μL of matrigel-equivalent matrix (Angiogenesis assay kit, Millipore, MA) and injected subcutaneously (4 injections per mouse) into the flanks of 6–12 week old female NSG mice. For 28 consecutive days (starting at day +3) mice were treated with daily injections of human parathyroid hormone (PTH [1–34]; R&D Systems, MN); 40 μg/kg body weight; dorsal neck fold) to further promote bone marrow niche formation. 8–10 weeks post BM-MSC application, mice bearing humanized ossicles were conditioned with 200 rads and hematopoietic cells differentiated from AML-iPSCs with carrier C3H/10T1/2 cells were injected directly intra-ossicle into 1–2 humanized ossicle-niches per mouse (20μl). Assessment of AML-iPSC engraftment was performed 8–12 weeks post-transplantation.

TCR clonality assay

TCR clonality of CD3+ T cells isolated from AML patients or T cell iPSCs was determined by capillary electrophoresis of PCR products mapping the TCR-β and TCR-γ regions exactly as described by the T cell clonality assay (Invivoscribe, CA).

DNA methylation array generation and analysis

Genomic DNA was isolated from the indicated iPSC and AML cell populations through standard methods (QIAGEN). Samples were processed and run at the University California San Diego Institute for Genomic Medicine Genomics Center using the Infinium human methylation 450 beadchip array which interrogates over 485,000 methylation sites at single-nucleotide resolution.

Data normalization, processing, and statistical analyses were performed in Bioconductor v 3.0 with R v. 3.2.3. Ilumina 450k methylation data were processed using Minfi v 1.12.0(Aryee et al., 2014). Preprocessing was done using the preprocessIllumina function with background correction enabled. Methylation β-values which range from 0 (unmethylated) to 1 (methylated) were computed for each CpG position using getBeta as β = Meth/(Meth + Unmeth + offset), with offset set to the standard Illumina value of 100. CpGs on the Y chromosome were discarded, but we retained the X chromosome locations since all patient samples were female. The relationship between samples was calculated by Multidimensional Scaling using the base R cmdscale function with default parameters and Euclidean distance applied to the 1000 most variable CpG sites based on the variance of their β values across all samples. Heatmaps were produced using the heatmap.2 function of gplots. For plots of CpGs across gene loci, smoothed fits were estimated by Loess regression.

Differentially methylated regions (DMRs) were computed using Bumphunter v.1.6.0(Jaffe et al., 2012). DMR analysis was based on a cutoff (minimal difference in β between sample comparisons) of 0.2. This cutoff allowed consideration of many potential DMRs (based on the observed distribution of β values in QC plots), while making sufficient bootstrap iterations (n = 1000) computationally tractable for estimation of the statistical significance of DMRs. The design matrix was defined by the comparison being conducted (e.g., AML versus AML iPSC), with patient identifier included as a confounding covariate. We report DMRs with boostrap p values < 0.01.

CpG islands locations were downloaded from the UCSC Table Browser for hg19. From these, we defined CpG shores as the regions 2kb either side of CpG islands, and CpG shelves as the next 2kb on each side. At each stage, features were merged into one if they “collided” with regions from an adjacent gene. Finally, remaining unannotated genomic regions were defined as CpG “open seas.” Overlaps between DMRs and CpG features (islands, shores, shelves) were computed using %over% from the GenomicRanges package v1.18.4 (Lawrence et al., 2013). Hence, a single DMR could overlap more than one feature if, for example, it spanned the junction of a CpG island and one of its shores. Detailed gene annotations were derived from the TxDb.Hsapiens.UCSC.hg19.knownGene annotation package, which is based on the UC Santa Cruz knownGene tables for the human genome hg19 assembly. Overlaps with DMRs were determined via the matchGenes function of Bumphunter, with the promoterDist parameter set to 1000. We defined a DMR to be associated with a promoter region if it was explicitly annotated as “promoter” or “overlaps 5′ end.”

For gene set analyses, lists of genes whose promoters were associated with significant DMRs were compared to known sets of genes by hypergeometric test. Hypergeometric p values were corrected for multiple hypothesis testing using qvalue v 1.43 (Storey and Tibshirani, 2003). Only the top 500 most differentially methylated significant DMRs were included in these analyses, since hypergeometic comparisons are not statistically well-defined if gene sets are too large. We report genesets with Q < 0.25 and at least 5 genes overlapping between compared sets.

Based on the observed distribution of β-values in QC plots, we defined CpG sites with β < 0.2 to be “hypo-methylated” and β > 0.7 to be “hyper-methylated.” Overlap of shared hypo- and hyper-methylated sites between sample types was obtained by averaging β across all samples of that type at each position. For all analyses, R code is available on request.

RNaseq library generation and analysis

Total RNA from different cell populations was isolated using RNAeasy Micro kit (QIAGEN) as per manufacturers recommendations. 300 ng of purified total RNA was treated with 10 units of RQ1 RNase-free DNase (Promega) at 37°C for 1 hr to remove trace amounts of genomic DNA. The DNase-treated total RNA was cleaned-up using RNeasy micro kit (QIAGEN). 50 ng of total RNA was used as input for cDNA preparation and amplification using Ovation RNA-Seq System V2 (NuGEN). Amplified cDNA was sheared using Covaris S2 (Covaris) using the following settings: total volume 120 μl, duty cycle 10%, intensity 5, cycle/burst 100, total time 2 min. The sheared cDNA was cleaned up using Agencourt Ampure XP (Beckman Coulter) to obtain cDNA fragments ≥ 400 base pairs (bp). 500 ng of sheared and size-selected cDNA were used as input for library preparation using NEBNext Ultra DNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (New England BioLabs) as per manufacturer’s recommendations. Resulting libraries (fragment distribution: 300–700 bp; peak 500–550 bp) were sequenced using HiSeq 4000 (Illumina) to obtain 2×150 base pair paired-end reads.

Expression levels of genes were quantified using Sailfish(Patro et al., 2014), with Illumina iGenomes reference transcriptome based on the UCSC known genes annotation, and hg19 as the reference human genome (ftp://igenome:G3nom3s4u@ussd-ftp.illumina.com/Homo_sapiens/UCSC/hg19/Homo_sapiens_UCSC_hg19.tar.gz). Transcript level expression levels were measured in transcripts per million (TPM), and summed for gene-level quantification. TPM values were transformed using a moderated log function: log2(1+TPM). For clustering and visualization purposes, expression levels were centered so that the average of each gene across all samples was zero. MDS and clustering were performed on the top 1000 most variable genes, as for methylation analysis.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Statistical analyses for all experiments are described in the figure legends or above sections where appropriate. P values comparing two means were calculated using the two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test or non-parametric two-tailed Mann-Whitney in Prism version 6.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc. La Jolla, CA). IC50 values were determined using the dose response (inhibition) function in Prism version 6.0. All error bars are defined as s.d. unless otherwise indicated.

DATA AND SOFTWARE AVAILABILITY

The accession number for the methylation data, including normalized b-values, and raw scan (.idat) files, and the processed RNA-seq data (TPM, transcripts per million) reported in this paper is GEO: GSE89778.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Feifei Zhao for excellent lab management, Melissa Stafford for animal husbandry, the Stanford Hospital Cytogenetics Laboratory, Stanford Neuroscience Microscopy Service, and Mingxia Gu for technical assistance. M.P.C. is supported by grants from the A.P. Giannini Foundation, Helen Hay Whitney Foundation, and Stanford Translational Research and Applied Medicine. R.M. is a New York Stem Cell Foundation Robertson Investigator and Leukemia and Lymphoma Society Scholar. This research was supported by the New York Stem Cell Foundation (R.M.), NIH grants R01CA188055 (R.M.) and R24 HL11756 (J.C.W.), and funding from the Ludwig Cancer Institute (R.M.). M.P.C. and R.M. are co-founders of and own equity in Forty Seven, Inc. M.P.C. is an employee and R.M. is a consultant to Forty Seven, Inc. R.M. serves on the Board of Directors for Forty Seven, Inc.

Footnotes

Supplemental Information includes seven figures and three tables and can be found with this article online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.stem.2016.11.018.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

M.P.C., M.W., J.C.W., and R.M. designed experiments. M.P.C. and R.M. wrote the manuscript. M.P.C., A.J.G., S.C., A.R., M.R.C., J.S., F.L., S.X., D.H., M.A., S.C., R.S., R.M.M., T.N., and H.W. performed experiments and analyzed data. All authors endorse the full content of this work. Materials and correspondence should be addressed to M.P.C. and R.M.

References