Abstract

A foremost challenge for the neurons, which are among the most oxygenated cells, is the genome damage caused by chronic exposure to endogenous reactive oxygen species (ROS), formed as cellular respiratory byproducts. Strong metabolic activity associated with high transcriptional levels in these long lived post-mitotic cells render them vulnerable to oxidative genome damage, including DNA strand breaks and mutagenic base lesions. There is growing evidence for the accumulation of unrepaired DNA lesions in the central nervous system (CNS) during accelerated ageing and progressive neurodegeneration. Several germ line mutations in DNA repair or DNA damage response (DDR) signaling genes are uniquely manifested in the phenotype of neuronal dysfunction and are etiologically linked to many neurodegenerative disorders. Studies in our lab and elsewhere revealed that pro-oxidant metals, ROS and misfolded amyloidogenic proteins not only contribute to genome damage in CNS, but also impede their repair/DDR signaling leading to persistent damage accumulation, a common feature in sporadic neurodegeneration. Here, we have reviewed recent advances in our understanding of the etiological implications of DNA damage vs. repair imbalance, abnormal DDR signaling in triggering neurodegeneration and potential of DDR as a target for the amelioration of neurodegenerative diseases.

Keywords: DNA damage, DNA damage response, DNA repair defects, Neurodegeneration

1. Introduction

The term neurodegeneration is broadly used to describe a diverse array of >600 neurodegenerative diseases (NDDs), characterized by the loss of specific groups of neurons in brain/spinal cord. Although, the majority of NDDs are sporadic, about 10–20% are driven by specific inherited mutations that accelerate the phenotype in the presence of various environmental factors. Common NDDs including Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Parkinson’s disease (PD), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), Huntington’s disease (HD), multiple sclerosis (MS), and prion diseases are not only ageing-associated but also involve diverse etiology like de novo as well as somatic mutations, epigenetic changes, environmental factors (stress, infection and nutrition) and genomic instability [1]. A common feature of majority of the NDDs emerging in the recent studies, is the accumulation of various types of genome damage together with specific repair inhibition/defects in the affected central nervous system (CNS) region. Genome damage has also been linked to hemin or iron mediated neuronal dysfunction after brain injury and stroke [2, 3]. Mutations in the genes of specific DNA repair pathways are uniquely manifested in early onset NDDs, e.g. nucleotide excision repair (NER) defects in xeroderma pigmentosum (XP) and Cockayne syndrome (CS), defective base excision/single-strand break repair (BER/SSBR) in ataxia-oculomotor apraxia-1 (AOA1) and spinocerebellar ataxia with axonal neuropathy (SCAN1), and defective DNA double-strand break repair (DSBR) and DNA damage response (DDR) signaling in ataxia telangiectasia (A-T) [4] and Nijmegen breakage syndrome [5]. Recent studies have highlighted the importance of DDR in post-mitotic neurons and the role of its chronic/abnormal activation triggering neuro-inflammation and transcriptional arrest [6–8]. Here, we have reviewed the critical roles of endogenous and exogenous factors underlying genome damage accumulation and repair deficiency as a common feature of NDDs, and discussed the possibility of targeting DDR signaling to counter genome damage mediated neuronal death.

2. Genome damage and repair responses in central nervous system

The sequence fidelity of the genome, particularly in aerobic cells, is continuously challenged because of DNA’s inherent instability due to spontaneous chemical reactions, exposure to endogenous ROS and other reactive pro-oxidant molecules [9]. The CNS consists of post-mitotic neurons as well as several fold more neuro-glial cells (astrocytes, oligodendrocytes and microglia). A distinct feature of terminally differentiated neurons, unlike the glial cells, is the lack of replication-associated DNA repair [10]. Recent studies have illuminated some unique features of neuronal versus glial cell responses to various types of genome damage, however, a comprehensive understanding of DNA repair mechanisms and CNS region-specific damage responses in various neurodegenerative conditions remain elusive. A number of studies in patients and rodent models with AD, PD, ALS, HD, ataxia and stroke show significantly elevated DNA damage together with defects in the repair of both nuclear DNA (nuDNA) and mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) in the affected CNS regions [11–15].

2.1. Endogenous causes of genome damage in the CNS

Due to the protection by blood brain barrier from external genotoxins, endogenous reactive oxygen species (ROS) -induced damage is the most critical threat to the CNS genome. In the brain, constitutively expressed enzymes such as the neuronal isoform of nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) contribute to the production of nitric oxide (NO°) radicals, which react with superoxide (O2·−) to produce peroxynitrite (ONOO−), a reactive nitrogen species (RNS) [16]. Trace levels of ROS/RNS are required for the normal functioning of the CNS, and serve as signaling molecules for regulating synaptic plasticity and adult neurogenesis [17]. Excessive ROS and other pro-oxidant species induce a variety of damage in DNA that include, oxidized and alkylated base lesions, abasic (AP) sites, inter-strand cross links, and single strand breaks (SSBs) [18]. The most common oxidized DNA lesion is 8-oxoguanine (8-oxoG), derived from guanine. Highly mutagenic/toxic but less common oxidized bases are formamidopyrimidines (FapyG and FapyA), 7,8-dihydro-8-oxoadenine (8-oxoA), 5-Hydroxyuridine (5-OHU), thymine glycol, 5-hydroxycytosine (5-OHC) etc [18]. SSBs may be induced directly by ROS or as intermediates during oxidized lesion repair. It is likely that persistent unrepaired bi-stranded oxidative damage in close proximity could result in secondary double strand breaks (DSBs) [18]. This phenomenon could be more prevalent in promoter sequences of actively transcribing genes, where a localized generation of ROS due to CpG demethylation-mediated promoter activation has been recently shown to generate transient strand breaks [19]. DSBs may also be generated in neuronal genome from accidental or diagnostic/therapeutic exposure to ionizing radiation (IR) and chemotherapeutic drugs [20]. A recent study reveals that DSBs occur in mouse brain cells during normal physiological/metabolic processes involving gene expression and chromosome remodelling associated with learning and memory [21]. Endogenous metabolic by-products such as homocysteine (Hcy), a non-essential sulfur-containing amino acid derived from methionine metabolism, has been implicated in CNS disorders with cystathionine beta synthase deficiency in AD. Elevated Hcy level disturbs the DNA methylation/demethylation cycle [22] and contributes to DNA damage by inducing thymidine depletion and promoting uracil mis-incorporation [23].

2.2. Excision repair pathways in the CNS genome

Excision repair pathways, which resolve the majority of endogenous genome damage including modified base or large bulky lesions are the most versatile among DNA repair processes. Small base lesions including oxidized or alkylated bases and AP sites are repaired via BER while larger bulky lesions like inter-strand cross-links are repaired via NER, both of which are conserved from bacteria to humans and are ubiquitous in most tissues including the CNS [24].

2.2.1. Base excision repair

BER mainly resolves alkylation and oxidative DNA damage (including SSB). Depending on the nucleotide length of the gap filling synthesis, BER is subdivided as short-patch BER (or single-nucleotide BER) (SP- or SN-BER) and long-patch BER (LP-BER), involving synthesis of one or 2–10 nucleotides, respectively [25]. BER involves four basic reactions: (a) repair initiation by base lesion excising DNA glycosylases (e.g., 8-oxoguanine glycosylase (OGG1), and endonuclease III homologue (NTH1), (Nei-Like DNA glycosylases) NEIL1, NEIL2 and NEIL3 for oxidized bases); (b) processing of blocked 3′ P (generated by NEILs) or 3′ dRP (also named 3′ PUA; generated by OGG1 and NTH1) termini at the SSB intermediate by polynucleotide kinase 3′ phosphatase (PNKP) or AP endonuclease 1 (APE1), respectively. The 5′dRP group generated during AP site cleavage by APE1 is processed by DNA polymerase β (Pol β); (c) SN-BER or LP-BER gap filling by a DNA polymerase and (d) final nick sealing by a DNA ligase [26].

Given that BER is the major pathway for repairing oxidative DNA damage, the most common damage in CNS genome, the deficiency of BER is frequently linked to aging and neurodegeneration. For example, among the DNA glycosylases, OGG1 expression is decreased during ageing in rat brain [27], whereas NEIL1 and NEIL2 levels are highly increased, consistent with the role of NEILs’ in transcription-associated repair and high transcriptional activity in the brain [26, 28–30]. The activity of APE1 is reduced in the frontal/parietal cortex, cerebellum, brainstem, midbrain and hypothalamus in aged rats [31]. Among DNA polymerases, Polβ is highly and ubiquitously expressed in brain regions [32] while its activity decreases in the brain upon aging [33]. The linkage of BER deficiency with neurodegeneration will be discussed in the later section.

2.2.2. Nucleotide excision repair

NER, requiring higher energy consumption than BER, was shown to be active in post-mitotic neurons in repairing lesions that cause substantial DNA helical distortions. These include ultraviolet (UV) induced cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers, 6–4 photoproducts, intra-strand crosslinks, DNA-protein crosslinks and DNA adducts caused by oxidative damage [34]. Two NER sub-pathways, global genome NER (GG-NER) and transcription-coupled NER (TC-NER), first described by Bohr et al. [35], can be distinguished based on the difference in the initial DNA damage recognition, but utilizing the same excision and repair synthesis steps subsequently. GG-NER recognizes and repairs DNA lesions throughout the genome while TC-NER resolves lesions present in the actively transcribing DNA regions. The sequential steps in NER include, (i) lesion sensing by the heterotrimeric complex of XPC/hHR23B/centrin 2 (for GG-NER) or RNA polymerase II/CS factors, CSA and CSB (for TC-NER); (ii) unwinding of the DNA; (iii) dual-incision of the DNA strand on the 3′ and 5′ sides of the lesion, leading to the excision of the lesion-containing single-stranded segment; (iv) repair synthesis of DNA to fill the nucleotide gap, and (v) final ligation to seal the nick. It is important to note that both neurons and astrocytes show lower activities of NER compared with the other cell types [36]. However, no data are available on NER in microglia, in either healthy or NDD patients.

2.3. DNA strand break repair

Repair of DNA strand breaks in a timely and error-free manner is vital for the preservation of genomic integrity. The importance of neuronal SSBR is evident in several NDDs, namely, AOA1, SCAN1 and microcephaly with early-onset, intractable seizures and developmental delay, which are caused by inherited mutations in SSB end processing factors [26, 37]. SSBR, which includes many overlapping sub-pathways, share the later steps of repair with BER such as end processing of damaged termini, gap-filling, and nick ligation [26, 38]. However, in addition to the 3′ P and 3′ dRP groups generated at SSB termini during BER, SSBR could involve diverse end processing enzymes to remove a variety of blocked termini generated by ROS [26]. Specifically, APE1 removes the most common block at ROS-induced SSB like 3′ phosphoglycolate or 3′ phosphoglycolaldehyde, another 3′ end-processing enzyme tyrosyl DNA phosphodiesterase 1 (TDP1) cleaves Top1(Tyr)-crosslinked to 3′ P generated by an aborted DNA topoisomerase 1 (TOP1) reaction. The resulting 3′ P is then removed by PNKP [39, 40], which also phosphorylates the 5′OH generated at SSB. Furthermore, abortive DNA ligation could form a unique type of 5′ blocking group, namely, adenylate linked via 5′-5′ bond at the 5′P terminus, which is processed by aprataxin (APTX) to restore the 5′ P terminus at the SSB [41, 42]. Two other key SSBR components include poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 (PARP-1) and X-ray repair cross-complementing protein 1 (XRCC1), which not only serve as scaffolding factors for recruiting and stabilizing other SSBR proteins, but also play a structural and regulatory role as damage sensors [43–45].

The repair of DNA DSBs in mammalian genomes could occur via three sub pathways: error-free pathway homology directed recombination (HDR) that occurs in only S/G2 cells requiring homologous DNA sequence (sister chromatid) as templates; and error-prone pathway non-homologous end-joining (NHEJ) or short microhomology-dependent alternative end-joining (Alt-EJ) throughout cell cycle. Although HDR may be critical during neurodevelopment, NHEJ has been suggested as the predominant DSBR pathway in mature neurons [46, 47]. Besides, it is likely that Alt-EJ may step into repair these secondary DSBs (generated from unrepaired bi-stranded SSBs) since elevated Alt-EJ activity has been observed in neuroblastoma cell lines [48], whereas its role in primary neurons has not been established.

NHEJ primarily requires DNA-PK holoenzyme (DNA-PKcs/Ku70/Ku80) and XRCC4/DNA LigIV complex, while Alt-EJ requires a distinct set of components including PARP-1, XRCC1/DNA LigIII (co-opted from SSBR) to initiate the repair [49, 50]. In any case, mutations in key DSBR proteins (e.g., ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM) in A-T, NBS1 in Nijmegen breakage syndrome, and meiotic recombination 11 (MRE11) in ataxia-telangiectasia-like disorder (A-TLD) have been shown to predispose humans to various neurodegenerative phenotypes, suggesting that DSBR is critical for post-mitotic neurons [47, 51–54].

2.4. DNA Damage Response (DDR) signaling in the CNS

DDR consists of a kinase cascade based network of coordinated signaling pathways, activated primarily in response to DSBs. In dividing cells (including neural progenitor cells during development, trace number of neural stem cells and dividing glial cells in adult CNS, the cell cycle is arrested at critical stages, particularly in response to DSBs, which is termed as cell cycle or DNA damage checkpoint activation, to provide sufficient time for optimal DNA damage repair and to prevent replication or segregation of DNA with unrepaired damages [55]. DNA strand breaks in mammalian genome typically activate phosphoinositide-3-kinase related (PIKK) family of serine/threonine kinases, ATM and ATM/RAD3-related (ATR), that play a central role in signal amplification by phosphorylating multiple downstream proteins to regulate checkpoint activation, DNA repair or cell death. ATM is predominantly activated in response to DSB-induced by radiation and other genotoxins, while ATR is activated by DNA replication stress, SSBs and UV-mediated damage, besides playing a back-up role to ATM [56].

As a central component of DDR cascade, ATM also plays an essential role in maintaining genomic stability in neuronal cells, and the loss of ATM associated DNA repair deficiency has been linked to neuronal dysfunction or neurodevelopmental defects as in A-T patients. A number of unique regulators of ATM and p53 in neurons have been identified. Tian et al. have demonstrated that cyclin-dependent kinase 5 (Cdk5) directly phosphorylates ATM at Ser794, which is required for the activation of its kinase activity and the phosphorylation of its substrates- p53 and histone H2A.X [57]. Another factor involved in DDR regulation, NAD+-dependent lysine deacetylase sirtuin 1 (SIRT1), is recruited at DNA break sites in an ATM dependent manner to stimulate ATM auto-phosphorylation and its activity. Phosphorylation of H2A.X (γH2AX) is significantly reduced in SIRT1 knockout neurons, which indicates the importance of SIRT1-initiated DNA damage signaling in neurons [58]. Furthermore, an RNA/DNA binding protein, fused in sarcoma/translocated in liposarcoma (FUS/TLS), whose toxicity has been implicated in motor neuron diseases, was identified as a substrate of ATM in response to DNA damage and has been shown to participate in both HDR- and NHEJ- mediated DSB repair pathways [13, 59]. The coordination between ATM and p53 appears to be critical for DNA damage signaling in neurons as in cycling cells. ATM and p53 are also involved in triggering persistent damage-induced neuro-inflammation via nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) activation, which is discussed in section 5.2. Herzog et al. showed that the p53 level is upregulated in wild type mouse neurons but significantly reduced in some brain regions of ATM−/− mouse in response to irradiation and post-mitotic neurons in ATM−/− mouse showed resistance to p53-mediated irradiation induced apoptosis [60], which provided some insight in to the possibility of preventing DNA damage related neuronal cell death by targeting the ATM-p53 pathway.

2.5. Mitochondrial DNA repair in the CNS

It has long been demonstrated that the increase of oxidative mtDNA damage is associated with neurodegenerative diseases and normal aging process [61]. Compared with nuDNA, human mtDNA is more susceptible to oxidative damage in a variety of tissues including brain [62], since mitochondria generates the majority of energy for cells through oxidative phosphorylation, producing abundant ROS [63, 64] and lacks protection from histones, [65]. SN-BER is recognized as a major pathway for mtDNA damage repair [66], although growing evidence shows that LP-BER, mismatch repair, HDR and NHEJ are also involved in mtDNA damage processing [67–69]. As in nuclear genome, the BER in mitochondria is initiated by DNA glycosylase including OGG1, Uracil DNA glycosylase (UNG), Muty Homologue (MYH), NTH1 and NEILs, followed by the processing of AP site by the only endonuclease in mitochondria, APE1. The knockout of APE1 is embryonic lethal in mouse [70, 71], while another study demonstrated that the loss of APE1 in mitochondria but not in nucleus is believed to trigger cellular apoptosis [72]. The final step of the mitochondrial BER is the ligation of the DNA nick by Ligase III but independent of XRCC1 [73, 74], unlike in nucleus. Interestingly, Gao et al. developed a mouse model in which the Ligase III or XRCC1 was conditionally inactivated in the developing neurons, and revealed that the Ligase III is important for mtDNA integrity but not for XRCC1 dependent, H2O2 or irradiation induced nuDNA damage repair in astrocytes [75, 76], which underscores the critical role of Ligase III mediated mtDNA repair in neuroprotection. Finally, human mtDNA encodes only 13 proteins, and mitochondria BER is highly dependent on nuclear encoded proteins [77].

The mtDNA repair capacity varies among different CNS cell types. For example, the oxidative mtDNA damage repair capacity was observed to be significantly decreased in cultured oligodendrocytes and microglia compared with astrocytes, and the difference is correlated with the apoptosis induction [78, 79].

3. Link between CNS genome damage and the neurodegenerative disease severity

Progressive accumulation of various unrepaired genome damage appears to be a unifying feature of many NDDs with diverse pathology, and correlates with symptomatic severity in most cases, including AD, PD and ALS [80, 81]. Recent studies have also linked unrepaired genome damage to several neuropsychiatric diseases including schizophrenia and bipolar disorders, where extensively higher levels of DNA/RNA oxidation have been observed [82, 83]. We have summarized below the salient features of the common CNS diseases and their association with various genome damage.

3.1. DNA damage accumulation in AD, PD and ALS

AD, the most common progressive NDD and the major cause of dementia in adults, is strongly age-associated and characterized by progressive loss of memory and cognitive capacity. AD is histopathologically associated with extracellular deposition of amyloid β (Aβ) peptide, intracellular aggregates of hyper-phosphorylated tau and neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) [84]. It was hypothesized around 30 years ago that increased DNA damage may be associated with AD due to the observation of specific chromatin structure alteration in AD patients [85, 86] and Mullart et al. subsequently quantified at least 2-fold increase in DNA breaks in cortex of AD patients [87], underscoring the contribution of accumulated genome damage. Other studies suggested strong association between the extent of oxidative damage in the neuronal genomes in affected brain regions with severity and progression of dementia in AD patients [11, 88–94]. Among the oxidized bases, increased levels of 8-OHA and Hcy were observed in DNA from AD parietal lobe, whereas increased thymine glycol, FapyA and FapyG, and 5-OHU were found in other affected brain regions [95]. Hippocampal DNA from late stage AD was shown to have a 2-fold acrolein/guanosine DNA adducts compared to that from unaffected brain, the repair implications of which are unknown [96]. Aβ seems to elicit DNA damage directly. In addition to the stimulation of ROS production [97–99], Aβ42 was shown to have DNA nicking activities similar to nucleases [100]. A recent study indicated that pathologically elevated level of Aβ increases neuronal DSB at baseline in mouse brain sections and cultured primary neurons, and enhanced the DSB that physiologic brain activity caused by eliciting aberrant synaptic activity [21].

As the most frequent neurodegenerative movement disorder, PD is characterized by the loss of dopaminergic (DAergic) neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNpc) [101–104] as well as the presence of proteinaceous cytoplasmic inclusions known as Lewy bodies in the brain of patient with either sporadic or familial form [105]. Although the pathological mechanisms underlining PD are complex and remains largely unknown, oxidative DNA damage (specifically, the production of 8-oxo-dG) has been demonstrated to be extensively generated in PD patients compared with age-matched control [106, 107]. PD-linked α-Synuclein (α-Syn) expressed transgenic mice show accumulation DNA damage within neurons [108]. Our later study also showed that both SSB and DSB accumulate in postmortem midbrain region of PD patients and the isolated DNA exhibited increased susceptibility to DNAse I treatment compared to control DNA [103]. Additionally, DNA damage-dependent activation of p53 and PARP-1 was shown to play a role in the death of DAergic neurons [109]. The MPTP (1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine)-induced PD mouse model shows DNA damage together with the activation of PARP1, which correlated with SNpc neuronal degeneration [110].

ALS or Lou Gehrig’s disease is an adult onset motor neuron disease, about 10% of which are inherited while ~90% occurs sporadically. Mutations in genes like superoxide dismutase (SOD-1) [111, 112], TAR-DNA binding protein-43 (TDP-43) [113, 114], FUS/TLS [115, 116], ubiquilin 2 (UBQLN2) [117], optineurin [118], valosin-containing protein (VCP) [119], C9orf72 [120], profilin1 (PFN1) [121] and matrin 3 (MATR 3) [122] have been identified in ALS patients. Similar to AD and PD pathologies, ALS affected motor neurons (frontal cortex, motor cortex, spinal cord, striatum) accumulate oxidized DNA bases in both nuclear and mitochondrial genomes [123]. For instance, ALS linked SOD1 G93A mutant expressed transgenic mice, consistently showed higher DNA damage compared to mice with wild type SOD1 [124]. In ALS patients harboring FUS/TLS mutations, increased DSBs were observed, and FUS/TLS knockdown in cultured human and rodent neurons leads to significant accumulation of DSBs [13]. TDP-43 is functionally similar with FUS, while its involvement in genome damage accumulation has not been investigated yet, although substantial increase in DNA damage has been observed in ALS patients with TDP-43 pathology [125].

3.2. DNA damage accumulation in Stroke

Stroke results from sudden interruption of blood supply to the brain, which could be due to abrupt blockage of arteries leading to the brain (ischemic stroke) or due to bleeding into brain tissue when a blood vessel bursts (hemorrhagic stroke). There is substantial evidence for the formation of oxidative genome damage after hypoxia followed by ischemic reperfusion and the release of iron and toxic hemoglobin by-products in brain parenchyma following hemorrhagic stroke [126–128]. Lesions including oxidative bases and strand breaks have been reported to remain unrepaired in post-stroke brain tissue, which could chronically predispose neurons to damage-mediated dysfunction or defective damage repair. It appears that BER is particularly important in protecting neuronal oxidative DNA damage after stroke. A mouse study indicated that activation of the BER pathway protects ischemic induced injury in brain by enhancing the endogenous oxidative DNA damage repair [129]. OGG1−/− mouse exhibited elevated oxidative DNA base lesions under ischemic conditions [130]. NEIL1 deficiency results in increased brain damage in a focal ischemia/reperfusion model of stroke [126]. While APE1 was shown to be greatly reduced specifically in rat hippocampus after ischemic insult, which suggests that the specific APE1 deficiency may involve in the extent of cellular apoptosis in response to ischemia [131]. During ischemia, damage to nucleic acids may also be caused by nucleases causing DNA fragmentation [132]. Extensive oxidative damage was detected in the mtDNA and nuDNA of astrocytes, neurons and vascular endothelial cells within 15–30 min of ischemia/reperfusion [133]. In intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH), hemin and iron promotes accumulation of DNA strand breaks and base oxidation in the affected cell genomes [134]. This is supported by the observation that intra-hippocampal injection of iron or hemoglobin in rats induces significant genome damage and neuronal death [135].

4. DNA repair defects and neuronal phenotypes

DNA repair defects have been observed extensively in patients with NDDs. BER deficiencies were shown in brains from AD patients [136] and in fibroblasts from CS patients [137, 138]. Deficient NER was shown in XP [139] and CS [140]. DNA mismatch repair (MMR) is deficient in HD [141]. SSBR is inefficient in AOA1 and SCAN1 [39, 142]. DSBR deficiencies were observed in AD [143], A-T and ataxia telangiectasia-like disorder (ATLD) [52, 144, 145]. Evidence linking the DNA repair deficiency with initiation and progression of NDDs is supported by studies in mouse models as well as in patient derived CNS tissue. For example, mouse with global or neuron-specific mutations in the excision repair cross-complementing groop1 (Ercc1), a factor functions in multiple DNA repair pathways involved in DNA crosslink or strand breaks repair, exhibits an age-dependent cognitive decline and neurodegeneration [146]. Another study revealed that the reduction of Pol β is sufficient to enhance the AD features in AD mouse model by inducing neuronal dysfunction, cell death, memory impairment and synaptic plasticity [147]. XRCC1 deficiency leads to persistent DNA strand breaks associated with the loss of cerebellar interneurons as well as abnormal hippocampal function [148]. Inherited and induced DNA repair defects and their specific predisposition to neurodegenerative phenotypes is discussed in the following sections.

4.1. Inherited DDR defects

A substantial subset of familial NDDs have been found to be inherited or acquired from defects in one or more key genes involved in DDR signaling. Mutation of DSBR proteins involved in the predisposition to familial NNDs include ATM, NBS1 and MRE11. For example, neurodegeneration is a syndrome of A-T patient carrying ATM mutation [149]. Mutations in another DSBR factor MRE11 is associated with ATLD phenotype [150]. In Nijmegen breakage syndrome, a 657Δ5 frameshift mutation of NBS1 results in the formation of truncated product, affecting its ability to act as a scaffold between γH2AX, and MRE11, which is required for DNA damage signaling in HDR, NHEJ and telomere maintenance [144]. While some syndromes characterized by ataxia are deficient in SSBR, for example, SCAN1 and AOA1 are caused by mutations in TDP1 and APTX, respectively [37, 151, 152]. TDP1 is required for efficient SSBR in mouse neurons and in lymphoblastoid cells from SCAN1 patient [153], [39]. Homozygous mutation in TDP1 (H493R), causes 25-fold reduction in its activity, leading to the accumulation of covalent Tdp1-DNA intermediates, thereby, inhibiting SSBR [39, 154]. While APTX was shown to protect DNA damage by interacting PARP-1, APE1, XRCC1 and XRCC4 [155, 156]. Caglayan et al. demonstrated that APEX coordinates with Polβ and flap endonuclease 1 (FEN1) in processing of the 5′-adenylated dRP-containing BER intermediate [157]. Interestingly, mouse models lacking both of TDP1 and APTX shows synergistic decrease in SSBR [158]. Homozygous mutation in PNKP with reduced SSBR capacity was demonstrated in progressive polyneuropathy characterized by underdevelopment and neurodegeneration [159]. Mutation in ATR in Seckel syndrome leads to reduced DNA repair capacity [160]. Other rare syndromes like LigIV, and NHEJ syndromes are directly linked to repair defects; mutations in LigIV affects its ability to interact with XRCC4 [161] whereas mutations in the NHEJ-associated gene encoding XRCC4-like factor (XLF) affects its ability to form a scaffold essential for XRCC4 and LigIV [162]. Taken together, familial NDDs are predominantly associated with DNA repair defects, or with compromised DDR signaling. We have listed various CNS diseases associated with inherited DDR defects and associated DNA repair proteins in Table 1.

Table 1.

Linkage of inherited DDR defects to CNS Diseases.

| Affected DNA Repair Pathway/Gene | Defect(s) | Associated Disease |

|---|---|---|

| BER Pathway | ||

| OGG1 | Ser 326 polymorphism (activity reduced) and genetic variants of OGG1. | Weakly associated with HD, ALS, Schizoprenia [258–260] |

| XRCC1 | Associated with defective TDP1 and aprataxin. Polymorphisms may lead to altered DNA repair. Genetic variants of XRCC1. |

Inherited spinocerebellar ataxias [261] Schizophrenia [262] PD [263] |

| Pol β | Deficiency in Pol β (Haploinsufficiency) | Exacerbates AD Pathology [147] |

| PCNA | Homozygous missense (p.Ser228Ile) | Hearing loss, Premature ageing, Telangiectasia, Neurodegeneration [264] |

| APE1 | Genetic variants of APE1 | PD [263] |

| FEN1 | Reduced FEN1 favors hairpin loop formation | HD [265] |

| NER Pathway | ||

| XPA | XPA gene mutations (c.288delT and c.349_353del). | XP [266] |

| XPB | Mutations in XPB (T119P) | XP [267] |

| XPD | Polymorphisms may lead to altered DNA repair. Mutations of XPD gene in XP61OS, Mutation in XPD (R112 loop or at the C-terminal end of the protein). |

Schizophrenia [260] skin symptoms of XP without CS, TTD, or other neurological complications [268–270] |

| SSBR | ||

| PNKP | c.1250_1266dup, Frameshift p.Thr424GlyfsX48. | Cerebellar atrophy, Polyneuropathy [159] |

| APTX | Mutations in APTX gene (K153E and S242N). | AOA1 [271–273] |

| TDP1 | Mutations in TDP1 (H493R). | SCAN1 [154, 274, 275] |

| DSBR-HR | ||

| NBS1 | 675Δ5 frameshift mutation or Hypomorphic mutations in NBS1. | Nijmegen break syndrome, A-T [276–278] |

| ATM/MRE1 | Mutations in MRE11, ATM. | A-T [52, 279, 280] |

| Rad50 | Mutations (c.3277C→T; p.R1093X), (c.3939A→T). | Nijmegen breakage syndrome [5] |

| XRCC3 | Polymorphisms may lead to altered DNA repair. | Schizophrenia [260] |

| DSBR-NHEJ | ||

| LIG4 | Hypomorphic Ligase IV mutations, defective NHEJ. | Ligase IV syndrome [161] |

| BRCA1 | Reduced BRCA1 levels. | AD [166] |

AD-Alzheimer’s Disease, ALS-Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, APTX- Aprataxin, APE1-apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease 1, ATM-Ataxia telangiectasia mutated, AOA1-Ataxia-oculomotor apraxia 1, BER-Base excision repair, BRCA1-Breast cancer associated gene 1, CSB-Cockayne syndrome B genes, DDR-DNA damage response, FEN1 - Flap Structure-Specific Endonuclease 1, HR-Homologous recombination, LIG4-Ligase IV, MRE11-Meiotic recombination 11, NHEJ-Non-homologous end joining, OGG1-8-Oxoguanine glycosylase, PD-Parkinson’s disease, PCNA-Proliferating Cell Nuclear Antigen, PNPK-Polynucleotide kinase 3′-phosphatase, Polβ-Polymerase β, Rad50-radiation sensitive 50, SSBR-Single strand break repair, TDP-1-Tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase 1, TFIIH-Transcription factor IIH, XRCC1-X-ray repair cross-complementing protein 1, XP-Xeroderma pigmentosum.

4.2. Neurodegeneration-linked etiological factors contribute to DNA damage/repair imbalance: A common basis for sporadic NDDs?

Reduced DNA repair is increasingly linked to a number of sporadic NDDs. General reduction in DNA repair capacity during ageing and in sporadic NDDs could involve multiple mechanisms including, (i) altered transcriptional regulation causing reduced expression of a repair protein (e.g., reduced levels of MRN, DNA-PKcs [143, 163] in CS; reduced OGG1 (in mitochondria) [164] and Polβ in AD [165], reduced breast cancer associated gene 1 (BRCA1) in AD brain [166]); (ii) inhibition of catalytic activity of repair proteins, whose levels are otherwise comparable to healthy neurons in the CNS, primarily by NDD-linked etiological factors like exposure to excessive pro-oxidant metals and ROS (e.g., metal and ROS-mediated inhibition of NEIL1, NEIL2, LigIII, APE1 etc., in AD and PD [167, 168]; reduced catalytic activity of OGG1 in AD [136, 169] and reduced Polβ activity in AD [136, 165] and (iii) abnormal degradation and/or mis-localization of repair proteins (e.g., degradation of ATM and PARP1 by caspases/Matrix-Metallo-Proteinases (MMPs) [170], nuclear to cytoplasmic mis-localization of FUS in ALS [13]. Most of the NDDs have complex etiologies including oxidative stress, pro-oxidant metal and other toxic free radicals, and the misfolded/aggregating protein response, together with extensive accumulation of various types of DNA damages [18]. However, the relative contribution of these factors towards progressive neurodegeneration and their precise mechanistic role in causing persistent genome damage in specific CNS regions remains unclear. Here, we present the cumulative evidence regarding the interplay among these etiologies in inducing genome damage, in inhibiting genome damage repair, affecting the dynamics of DDR signaling, and thereby causing damage-repair imbalance in neuronal genomes (Figure 1, 2).

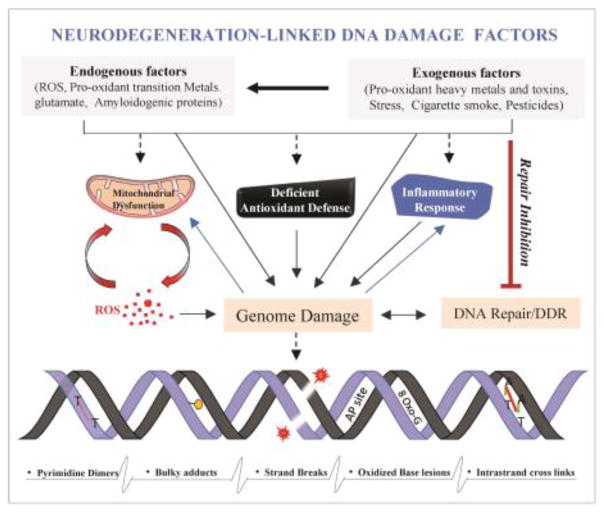

Figure 1.

A double whammy of genome damage induction and repair defects in neurodegeneration. Common etiological factors linked to neurodegeneration not only inducing genome damage but also inhibits DNA repair or cause defective DNA repair. Both endogenous and exogenous factors cause various types of DNA damage directly or via mitochondrial dysfunction, deficient antioxidant defence and inflammatory response. While cells have evolved proficient DNA repair machinery to cope such damage, defective repair influenced by the neurodegenerative etiologies leads to imbalance in damage vs. repair and persistent accumulation of unrepaired genome damage.

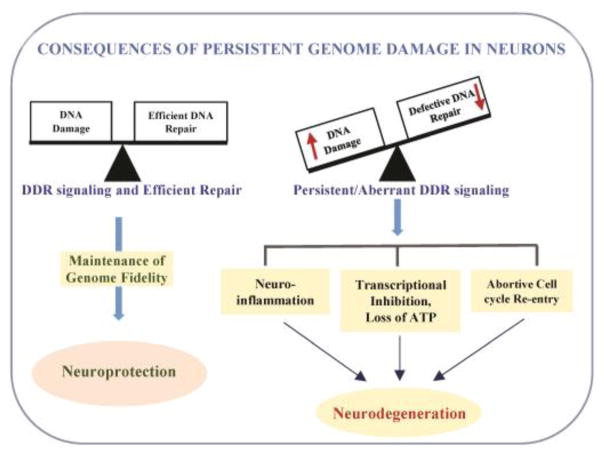

Figure 2.

Schematic illustration of implications of persistent genome damage/deficient DNA repair in neurodegeneration. Persistent presence of genome damage, together with deficient/defective DNA repair in long lived neurons leads to aberrant DNA damage response (DDR) signaling that triggers neuro-inflammation, transcriptional inhibition, and/or abnormal cell cycle regulation, resulting in neuronal cell death. Implications of chronic DDR signaling in neuronal dysfunction and its potential as a target for ameliorating neuronal death is discussed in this review.

4.2.1. ROS and pro-oxidant metal ions

A key connection among most NDDs is the impairment of redox homeostasis in brain primarily involving excessive ROS and pro-oxidant metal ions, many of which are essential in trace levels [32, 171–173]. Altered homeostasis of essential transition metals like Cu, Fe, Zn and Mn, and excessive accumulation of Al, Cr, Pb, and Ni in the CNS have been implicated in the onset/progression of AD, PD, ALS, Wilson’s disease and stroke [174]. Although, a common mechanism of metal toxicity in CNS is the generation of ROS via Fenton reaction, excess free metals also cause neuronal genotoxicity in multiple ways including, (i) direct DNA binding leading to oxidative damage as well as strand breaks, altered DNA methylation and localized chromatin condensation, interference with transcription factors’ binding at promotor sequences [134, 175], which together impact gene expression; (ii) functional inhibition of proteins associated with various DNA transactions and anti-oxidant machinery, which could involve the displacement of essential metal cofactors by toxic metal ions (e.g., Zn from Zn finger proteins) and metal ion binding to redox sensitive amino acid residues (e.g., thiol groups) in proteins to alter protein conformation [176]. For example, Cu binding could cause localized chromatin condensation in neurons both directly and via altered DNA methylation [177], which could lead to altered gene expression. Al ions, together with amyloid peptide alters DNA conformation and super helicity [178]. Further, elevated levels of Fe, Cu, Zn inhibit the proteins of BER pathway via changes in protein conformation and cysteine oxidation [134, 179], whereas excess Pb, Fe, Cd cause inhibition of APE1’s nuclease activity, and exposure to Cd also inhibits OGG1 activity, and down-regulates DNA polymerase δ (Polδ) expression, thereby, impairing BER pathway [180]. Furthermore, during pathological conditions like ischemic stroke, oxidative stress activates nuclear metal-dependent proteases leading to nuclear proteolysis of ATM, XRCC1, and PARP1, and thereby affecting repair. This cleavage of DDR proteins could also be a direct cause of oxidative stress-mediated activation of caspase-3 to promote neuronal apoptosis [181]. Together, these studies reveal that pro-oxidant metal and other redox species serve as major contributors of genomic instability during the etiology of neurodegenerative pathologies [182].

4.2.2. Misfolded amyloidogenic proteins contribute to DNA damage

The major hallmark of ~ 95% of NDDs is the aberrant folding and aggregation of amyloidogenic proteins, which typically sequester as intra- (cytoplasmic) or extracellular inclusion bodies [183]. The presence of Aβ peptide fragments-positive extracellular plaques and intracellular tau protein-positive NFTs in the AD brain, α-Syn rich Lewy bodies in PD, prion proteins in prion diseases, misfolded TDP-43, FUS/TLS, or SOD1 in different subsets of the ALS group of diseases, expanded polyglutamine (polyQ) proteins’ containing inclusions in ataxia or HD, etc., are considered as the hallmark pathological characteristics of these respective diseases, although the measure of aggregates/plaques may not always be correlated with the disease severity [184]. Neuronal cells treated with Aβ or α-Syn develops characteristics of apoptosis, including membrane blebbing, compaction of nuclear chromatin, and DNA fragmentation. It was shown that the production of Aβ is increased approximately two to four fold in human primary neuronal cells induced to undergo apoptosis by serum deprivation [185]. Treatment with synthetic Aβ peptides has been shown to trigger the degeneration of cultured neurons through the activation of apoptotic pathway preceding accumulation of unrepaired DNA strand breaks (133). In addition, Aβ (25–35) fragment also induces the expression of DNA damage-inducible gene (Gadd45) implicated in the DNA excision-repair process [186]. Aurintricarboxylic acid, a nuclease inhibitor, was shown to prevent apoptotic DNA fragmentation and delays cell death caused by Aβ [187]. Sub-lethal doses of Aβ contribute to loss of DNA-PK activity, thereby, leading to delayed DNA repair [188]. Furthermore, J20 mice expressing high level of hAPP showed the presence of DSB marker γH2AX in brain, suggesting a possible link between Aβ accumulation and increased DSBs formation [21]. Similarly, the presence of toxic α-Syn aggregates inhibits the mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway, alters axonal trafficking and induces oxidative stress [189], leading to the accumulation of 8-oxoG in both the mtDNA and nuDNA of DAergic neurons in PD. While Aβ and α-Syn toxicity could cause genome damage via multiple mechanisms, some studies have indicated that misfolded amyloid proteins could interfere with the repair process due to their DNA binding activity. Furthermore, the Aβ peptides were shown to acquire DNA nicking activity, particularly in the presence of pro-oxidant metal ions in vitro [190]. Aβ (1-42) and Aβ (1–16) fragments, misfolded α-Syn and tau bind to GC-rich DNA and also alter the conformation of DNA, which could impact gene expression patterns [191, 192]. Studies have shown that prion proteins also have DNA-binding properties [193], which in turn induces structural changes in prion peptides by forming stable complexes causing further polymerization [194]. From the above lines of evidences, it appears that most amyloid proteins (α-Syn, Aβ, prions) possess intrinsic DNA-binding property. In SCA3, the PNKP is inactivated due to its interaction with mutant ATXN3 (encodes expanded polyQ sequences), resulting in defective DNA repair, persistent accumulation of DNA damage/strand breaks, and subsequent chronic activation of the DDR signaling pathway [195, 196].

4.3. CNS mitochondrial DNA damage and repair defects

Mitochondrial dysfunction, one of key events contributing to NDDs and aging, can result from mtDNA point mutations or deletions [197]. For example, mutations in the subunits of mitochondrial respiratory chain Complex I occurs in approximately 95% of Leber Hereditary Optic Neuropathy [198]. Some mtDNA mutations have also been associated with AD [199, 200] and PD [201–203], although no clear causative mtDNA mutations are linked with these diseases.

Consistently, studies have revealed elevated mtDNA damage accumulation or mtDNA repair defects in patients with NDDs. In AD, a three-fold increase in 8-oxoG lesion in mtDNA from frontal, temporal, and parietal lobes and cerebellar brain tissues have been observed compared to age matched controls [204]. Increased DNA fragmentation and reduced DNA content/mass in brain mitochondria have been linked to the extent of hippocampal degeneration in AD [205]. In HD, mutant huntingtin is associated with elevated mtDNA oxidation [206], as well as higher levels of 8-oxoG in the striatum of HD patients and in a transgenic mouse model (R6/2) [207, 208]. mtDNA damage was suggested as an early biomarker for HD-associated neurodegeneration [209]. Patients with XP group C (XPC), accumulate pyrimidine dimers, 8-oxoG, and thymine glycol in the mtDNA of CNS [210]. In children with autism, elevated mtDNA damage was observed [211]. Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) with somatic mitochondrial mutations [212], Spinal and Bulbar muscular atrophy or Kennedy disease, (a motor neuron disorders) also exhibit mtDNA damage [213]. Somatic mutations in neuronal mtDNA causes ATP depletion, increased oxidative stress, and in turn leading to nuclear genome damage [214]. Patients with XP accumulate pyrimidine dimers, 8-oxoG, and thymine glycol in the mtDNA of CNS tissue. These observations provide important insights into the impact of mtDNA somatic mutations in neuronal mitochondria.

Elevated mtDNA AP sites were observed in nigral dopamine neurons in PD patients, suggesting persistent BER defects [215]. A transgenic mouse model expressing Mito-PstI, an endonuclease targeted exclusively into DAergic neuronal mitochondria to generate mtDNA DSBs, demonstrates strong patterns of SN degeneration similar to that observed in PD patients [12]. In support of the above, mtDNA in DAergic neurons possesses higher oxidized base lesions [106, 216] together with unrepaired strand breaks, AP sites, and deletions in SN of PD brain [217]. Presence of unrepaired SSBs and DSBs in the mitochondrial genome of familial α-Syn mutant (A53T) transgenic mice correlated with mitochondrial degeneration and PD like pathology [108].

As previously mentioned, mtDNA repair is highly dependent on nuclear encoded proteins, indicating that a continuous interplay between nuDNA and mtDNA is essential. Nuclear encoded proteins are imported into mitochondria through mitochondria membrane translocases: translocase of the mitochondrial outer (TOM) and inner (TIM) membrane protein complex. Brain regions such as hippocampus, SN, and cortex which are significantly affected in AD, PD, and HD show altered levels of TOM and TIM [218]. Mid brain tissue studies from PD patients and wild type and mutant (A53T) α-Syn transgenic mice model revealed that the protein level of TOM40, an important transmembranous domain of the TOM complex involve in the import of nuclear encoded proteins, is significantly reduced along with high level of oxidative damage and deletions in mtDNA, which could be rescued by overexpressing of TOM40 [218]. Although accumulated mtDNA damage may be induced by elevated ROS observed in α-Syn accumulating cells, reduction of TOM40 levels may also contribute to the mtDNA damage by inefficient import of nuclear encoded mtDNA repair proteins. These studies opened up new avenues towards understanding the mitochondrial protein import defects in NDDs as well as search for novel biomarkers of degraded TOM/TIM peptide fragments.

The regulation of brain mitochondrial BER varies through the lifespan. DNA glycosylases (UNG1, OGG1, and NTH1), are upregulated in the cortical mitochondria of brain tissues from young mice, but downregulated in the brain tissues from ageing mice [219, 220].

5. Pathological response to persistent genome damage in neurons

In contrast to the early school of thought that non-cycling cells such as mature neurons may be more resistant to genome damage induced mortality, cumulative evidences indicate that the persistent presence of unrepaired damage particularly DNA strand breaks, could have highly deleterious effect on neurons, including transcriptional arrest at the damage sites, formation of RNA-DNA hybrids or R-loops at the stalled transcriptional sites, DDR-mediated activation of neuro-inflammatory signaling, possible damage-induced deregulation of cell cycle machinery and abortive cell cycle-mediated cell death initiation and brain atrophy [221]. Persistent DNA damage in neurons during neurodevelopment as well as in adults may also cause defective neurogenesis, which is associated with many NDDs [6]. Unlike proliferating cells in which DNA damage induces cell cycle arrest, unrepaired DNA damage in post-mitotic neurons could trigger cell-cycle re-entry but usually leads to neuronal cell death [222].

5.1. DNA damage induced transcriptional inhibition

With about three to five times more actively transcribing genes than elsewhere in the body [6], damage and repair at transcriptional sites are critical for neuronal survival. Neuronal transcription machinery has been shown to closely collaborate with DNA damage sensing and repair as well as chromatin organization [223]. Many DNA lesions (e.g., 5′, 8-purine cyclo-deoxynucleosides, purine dimers, 8-oxoG, thymine glycol and DNA strand breaks) stall RNA polymerase II in transcribing genes. Furthermore, it has been proposed that the inhibition of RNA polymerase II can be via ATM dependent or DNA-PK dependent pathways [224]. The accumulation of 8-oxoG in redox-sensitive transcribing genes containing GC-rich promoter sequences renders them particularly vulnerable to oxidative modification-mediated transcriptional inhibition [225]. Consistently, recent studies have reported the accumulation of R-loop structures (presumably formed by damage-induced inhibition of transcription) in AD and ALS affected brain tissues [226–228]. Transcriptional stalling together with DNA repair inhibition is a recipe for exacerbating genomic instability and enhancing the hyper-methylation of gene promoters leading to gene silencing [229]. Taken together, these recent developments underscore the implications of defective DNA repair and DDR in neuronal cell death.

5.2. DDR and neuro-inflammation

The activation of the neuro-inflammatory response has been linked to ageing and NDDs, and its connection to unrepaired genome damage has been recently postulated [230]. Several studies have shown that factors like NF-κB are activated in response to stroke [231], kainite-induced seizures [232] and Aβ-treated fetal rat cortical neurons [233]; however, the functional role of RelA/NF-κB in neuronal death/survival remains unclear [234]. As mentioned before, DDR-induced signaling activates the ATM-p53 and ATM-IKKα/β-interferon (IFN)-β signaling pathways. The latter involves the expression of IFN-inducible IFI16 gene, which stimulates STING-dependent activation of IFN-β, activation of IFI16 inflammasome, and the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-1β and IL-18). Because DDR activates the expression of the IFI16 gene, thereby, increased levels of the IFI16 protein enhances p53-mediated transcriptional activation of many genes including the ones involved in DNA repair. At the same time, persistent DDR-mediated neuro-inflammation contributes to ageing-associated progressive neuronal dysfunctions. However, a complete understanding of how the accumulation of DNA damage, and DDR in various NDDs contribute to inflammation requires further investigations.

5.3. Cell cycle re-entry of neurons – role of unrepaired DNA strand breaks?

Neuronal cycle re-activation was first linked to DNA damage in 2004, when Kruman et al. [235] found that DNA damage causing agents including irradiation, etoposide, Hcy, methotrexate and Aβ1-42 were able to induce cell cycle re-entry followed by neuronal apoptosis, in which p53 played a critical regulatory role [235]. Post-mitotic neurons remain in a quiescent G0 state and are normally incapable of re-entering cell cycle. However, aberrant cell cycle re-entry has been extensively observed in several NDDs, supported by the expression of cyclins (e.g., Cyclin B1 and D), cyclin-dependent kinases (e.g., CDK3 and 4) and other cell cycle mediators (e.g., Cdc2) in AD, PD, ALS and HD [58, 236–238]. Growing evidence indicate that the re-entry into the cell cycle leads to cell death instead of neuronal proliferation. The cell cycle-regulated protein kinase Cdc2 expressed in rat post-mitotic granular neurons mediates apoptosis, suggesting that cell cycle re-entry may function as a common pathological basis for neuronal cell death [239]. Despite the mystery of how cell cycle re-entry induces neuronal apoptosis, DNA damage has been recognized as a trigger of unscheduled cell cycle re-entry. Consistently, an aberrant cell cycle with accumulated DNA damage is frequently observed in cultured cells or mouse models of neurodegeneration [240]. However, the mechanism of DNA damage-activated cell cycle in post-mitotic neuronal cells remains unclear. It has been proposed that neurons re-enter the cell cycle in order to repair DSBs via HDR [235].

6. Concluding remarks

It is clear that there exists strong evidence for correlation between unrepaired DNA damage, persistent DDR signaling and neuronal dysfunction or cell death in various NDDs as well as in ageing. However, the direct role of genome damage in initiation and progression of neurodegeneration needs to be further established. Furthermore, how the specific CNS cell types respond to DNA damage and communicate to ensure homeostasis needs to be investigated. In addition, the consequences of neuronal DNA damage could significantly impact the homeostasis of mitochondrial–nuclear cross-talk and the post-mitotic status of neurons. It is important to investigate whether DDR signaling mediated cell cycle deregulation, transcriptional defects and neuro-inflammation substantially contribute to neuronal loss in NDDs, it is also critical to understand the relative toxicity of NDD-linked etiological factors in causing nuclear vs. mitochondrial genome damage/repair defects.

Tight regulation of DDR is important for the genomic integrity and survival of cells in the CNS. Persistent and aberrant activation of DDR could lead to increased genome instability and susceptibility to neurodegeneration. Consistently, preliminary evidences suggest that modulating DDR signaling could be beneficial in attenuating the neurodegeneration. Suberbielle et al. showed that Aβ oligomer-induced increases of neuronal DSB could be prevented by blocking the activation of extra-synaptic NMDA (N-methyl-D-aspartate) -type glutamate receptors in cultured primary neurons, which indicates that the inhibition of these receptors may contribute to protecting and stabilizing neuronal genome in pathological conditions [21]. Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) was demonstrated to be neuroprotective by attenuating Aβ induced 8-oxo-dG, AP sites, SSB as well as DSB in rat primary cortical neurons [241]. Studies reported that Ku-mediated DNA repair is impaired in mutant huntingtin expressed neurons while supplementation of exogenous Ku70 rescues pathological phenotypes in mouse [242], and Drosophila models of HD [243]. In a recent study, a neuroprotective role of BER machinery was demonstrated in mouse model. Martin et al. enforced expression of human APE1 and OGG1 in vulnerable neurons and found that the expression significantly suppressed the axotomy and target deprivation induced apoptosis of thalamic neurons and motor neurons, which indicates that the modulation of DNA repair could be a potential therapeutic target for DNA damage related neuronal apoptosis [244]. Another study revealed that, overexpression of sirtuin 6 (SIRT6), which is down-regulated in brains of AD patients as well as 5XFAD mice, likely regulated by Aβ42, prevents Aβ42-induced DNA damage in a p53-depedent manner [244, 245].

Furthermore, ATM has been proposed as a promising therapeutic target for NDDs. Partial genetic reduction or pharmacological inhibition of ATM using small molecule inhibitor KU-60019 was shown to be protective in HD cells and animal models [246]. Although the precise mechanism of ATM’s neuroprotection role has not been fully understood and multiple signaling pathways may overlap, targeting the DNA damage induced, ATM mediated p53/E2F1 dependent apoptosis could be one of the major aspects. ATM was shown to be required for IR induced, p53 mediated cell death in mouse developing CNS [60]. E2F transcription factor 1 (E2F-1), a transcription factor that regulates cell cycle in cycling progenitor [247] and post-mitotic cells [248], and the dysregulation of which is linked with neuronal cell death [249–254]. E2F-1 is stabilized by ATM in response to DNA damage [255]. A study focused on targeting ATM-p53-E2F1 pathway demonstrated that the ATM inhibitor, caffeine, shows protection against complex I inhibition-induced apoptosis by inhibiting p53 activation and E2F1 related cell-cycle reentry in cerebellar granule neurons [256].

Targeting mtDNA repair also could be a viable approach for neuronal protection against oxidative lesions. Oligodendrocytes are one of the primary types of glial cells and are extremely sensitive to oxidative stress associated with decreased mtDNA repair capacity, and the dysfunction of which leads to severe neurological deficits. Druzhyna et al. transfected mitochondrial targeting sequence fused human OGG1 gene into rat oligodendrocyte and found that the increased oxidative mtDNA repair by OGG1 expression significantly resists oligodendrocyte to the lethal effects of menadione mediated oxidative stress [257].

Future studies should explore other DDR targets such as NF-κB, components of BER, damage-induced cell cycle regulation, and transcriptional signaling as avenues to prevent neuronal death, a first priority in NDD patients, while simultaneously exploring ways to improve back-up genome repair capacity.

Highlights.

Persistent genome damage is linked to accelerated ageing and age-associated neurodegeneration.

Inherited DNA repair defect is uniquely manifested in neurodegenerative phenotype.

DNA repair capacity is compromised in most sporadic neurodegenerative conditions.

Varied etiological factors contribute to genome damage and their repair defect.

Imbalance in genome damage and repair may be the common basis for diverse diseases involving neurodegeneration.

Acknowledgments

The research in the Hegde laboratory is supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health USPHS R01 NS 088645, Muscular Dystrophy Association (MDA 294842), ALS Association (15-IIP-204), Alzheimer’s Association (NIRG-12-242135) to M.L.H. and Melo Brain Funds (M.L.H. and K.S.R.). S.M. is supported by USPHS grants R01 CA CA158910 and I.B. is supported by NIEHS R01 ES018948. V.V. is supported by a Doctoral Scholarship granted by the Institute for Training and Development of Human resources of Panama (IFARHU) and the National Secretariat for Science, Technology, and Innovation of Panama (SENACYT). K.S.R. is supported by the National System on Investigation (SNI) grant of SENACYT. T.K is supported by National Institutes of Health R01NS094535. The authors thank other members of the Hegde laboratory for their assistance.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kerner B. Psychiatric genetics, neurogenetics, and neurodegeneration. Front Genet. 2014;5:467. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2014.00467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gu Y, et al. Iron accumulation and DNA damage in a pig model of intracerebral hemorrhage. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2011;111:123–8. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-0693-8_20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee JY, et al. Hemoglobin and iron handling in brain after subarachnoid hemorrhage and the effect of deferoxamine on early brain injury. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2010;30(11):1793–803. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2010.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McKinnon PJ. DNA repair deficiency and neurological disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10(2):100–12. doi: 10.1038/nrn2559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Waltes R, et al. Human RAD50 deficiency in a Nijmegen breakage syndrome-like disorder. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;84(5):605–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hetman M, Vashishta A, Rempala G. Neurotoxic mechanisms of DNA damage: focus on transcriptional inhibition. J Neurochem. 2010;114(6):1537–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06859.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nakanishi H, Hayashi Y, Wu Z. The role of microglial mtDNA damage in age-dependent prolonged LPS-induced sickness behavior. Neuron Glia Biol. 2011;7(1):17–23. doi: 10.1017/S1740925X1100010X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barzilai A, Biton S, Shiloh Y. The role of the DNA damage response in neuronal development, organization and maintenance. DNA Repair (Amst) 2008;7(7):1010–27. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2008.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hegde ML, Izumi T, Mitra S. Oxidized base damage and single-strand break repair in mammalian genomes: role of disordered regions and posttranslational modifications in early enzymes. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 2012;110:123–53. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-387665-2.00006-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iyama T, Wilson DM., 3rd DNA repair mechanisms in dividing and non-dividing cells. DNA Repair (Amst) 2013;12(8):620–36. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2013.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang J, et al. Increased oxidative damage in nuclear and mitochondrial DNA in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurochem. 2005;93(4):953–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pickrell AM, et al. Striatal dysfunctions associated with mitochondrial DNA damage in dopaminergic neurons in a mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. J Neurosci. 2011;31(48):17649–58. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4871-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang WY, et al. Interaction of FUS and HDAC1 regulates DNA damage response and repair in neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16(10):1383–91. doi: 10.1038/nn.3514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moore N, et al. Homogeneous repair of nuclear genes after experimental stroke. J Neurochem. 2002;80(1):111–8. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-3042.2001.00680.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jonson I, et al. Oxidative stress causes DNA triplet expansion in Huntington’s disease mouse embryonic stem cells. Stem Cell Res. 2013;11(3):1264–71. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2013.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thanan R, et al. Oxidative stress and its significant roles in neurodegenerative diseases and cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16(1):193–217. doi: 10.3390/ijms16010193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Massaad CA, Klann E. Reactive oxygen species in the regulation of synaptic plasticity and memory. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;14(10):2013–54. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hegde ML, et al. Oxidative genome damage and its repair in neurodegenerative diseases: function of transition metals as a double-edged sword. J Alzheimers Dis. 2011;24(Suppl 2):183–98. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2011-110281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clark DW, et al. Promoter G-quadruplex sequences are targets for base oxidation and strand cleavage during hypoxia-induced transcription. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012;53(1):51–9. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shiwaku H, Okazawa H. Impaired DNA damage repair as a common feature of neurodegenerative diseases and psychiatric disorders. Curr Mol Med. 2015;15(2):119–28. doi: 10.2174/1566524015666150303002556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Suberbielle E, et al. Physiologic brain activity causes DNA double-strand breaks in neurons, with exacerbation by amyloid-beta. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16(5):613–21. doi: 10.1038/nn.3356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kruman II, et al. Homocysteine elicits a DNA damage response in neurons that promotes apoptosis and hypersensitivity to excitotoxicity. J Neurosci. 2000;20(18):6920–6. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-18-06920.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vanzin CS, et al. Homocysteine contribution to DNA damage in cystathionine beta-synthase-deficient patients. Gene. 2014;539(2):270–4. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2014.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Subba Rao K. Mechanisms of disease: DNA repair defects and neurological disease. Nat Clin Pract Neurol. 2007;3(3):162–72. doi: 10.1038/ncpneuro0448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krokan HE, Bjoras M. Base excision repair. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2013;5(4):a012583. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a012583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hegde ML, Hazra TK, Mitra S. Early steps in the DNA base excision/single-strand interruption repair pathway in mammalian cells. Cell Res. 2008;18(1):27–47. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen D, et al. Age-dependent decline of DNA repair activity for oxidative lesions in rat brain mitochondria. J Neurochem. 2002;81(6):1273–84. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.00916.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dou H, Mitra S, Hazra TK. Repair of oxidized bases in DNA bubble structures by human DNA glycosylases NEIL1 and NEIL2. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(50):49679–84. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308658200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dou H, et al. Interaction of the human DNA glycosylase NEIL1 with proliferating cell nuclear antigen. The potential for replication-associated repair of oxidized bases in mammalian genomes. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(6):3130–40. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709186200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilson DM, 3rd, McNeill DR. Base excision repair and the central nervous system. Neuroscience. 2007;145(4):1187–200. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kisby GE, et al. Effect of caloric restriction on base-excision repair (BER) in the aging rat brain. Exp Gerontol. 2010;45(3):208–16. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rao KS, et al. Loss of base excision repair in aging rat neurons and its restoration by DNA polymerase beta. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2000;85(1–2):251–9. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(00)00266-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vyjayanti VN, Swain U, Rao KS. Age-related decline in DNA polymerase beta activity in rat brain and tissues. Neurochem Res. 2012;37(5):991–5. doi: 10.1007/s11064-011-0694-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kulkarni A, Wilson DM., 3rd The involvement of DNA-damage and -repair defects in neurological dysfunction. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82(3):539–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bohr VA, et al. DNA repair in an active gene: removal of pyrimidine dimers from the DHFR gene of CHO cells is much more efficient than in the genome overall. Cell. 1985;40(2):359–69. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90150-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yamamoto A, et al. Neurons and astrocytes exhibit lower activities of global genome nucleotide excision repair than do fibroblasts. DNA Repair (Amst) 2007;6(5):649–57. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2006.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Takashima H, et al. Mutation of TDP1, encoding a topoisomerase I-dependent DNA damage repair enzyme, in spinocerebellar ataxia with axonal neuropathy. Nat Genet. 2002;32(2):267–72. doi: 10.1038/ng987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Caldecott KW. Single-strand break repair and genetic disease. Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9(8):619–31. doi: 10.1038/nrg2380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.El-Khamisy SF, et al. Defective DNA single-strand break repair in spinocerebellar ataxia with axonal neuropathy-1. Nature. 2005;434(7029):108–13. doi: 10.1038/nature03314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pouliot JJ, et al. Yeast gene for a Tyr-DNA phosphodiesterase that repairs topoisomerase I complexes. Science. 1999;286(5439):552–5. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5439.552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rass U, Ahel I, West SC. Actions of aprataxin in multiple DNA repair pathways. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(13):9469–74. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611489200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.el-Khamisy SF, Caldecott KW. DNA single-strand break repair and spinocerebellar ataxia with axonal neuropathy-1. Neuroscience. 2007;145(4):1260–6. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.08.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Caldecott KW, et al. XRCC1 polypeptide interacts with DNA polymerase beta and possibly poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase, and DNA ligase III is a novel molecular ’nick-sensor’ in vitro. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24(22):4387–94. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.22.4387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Masson M, et al. XRCC1 is specifically associated with poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase and negatively regulates its activity following DNA damage. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18(6):3563–71. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.6.3563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.El-Khamisy SF, et al. A requirement for PARP-1 for the assembly or stability of XRCC1 nuclear foci at sites of oxidative DNA damage. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31(19):5526–33. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vyjayanti VN, Rao KS. DNA double strand break repair in brain: reduced NHEJ activity in aging rat neurons. Neurosci Lett. 2006;393(1):18–22. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.09.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Orii KE, et al. Selective utilization of nonhomologous end-joining and homologous recombination DNA repair pathways during nervous system development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(26):10017–22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602436103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Newman EA, et al. Alternative NHEJ Pathway Components Are Therapeutic Targets in High-Risk Neuroblastoma. Mol Cancer Res. 2015;13(3):470–82. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-14-0337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mahaney BL, Meek K, Lees-Miller SP. Repair of ionizing radiation-induced DNA double-strand breaks by non-homologous end-joining. Biochem J. 2009;417(3):639–50. doi: 10.1042/BJ20080413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dobbs TA, Tainer JA, Lees-Miller SP. A structural model for regulation of NHEJ by DNA-PKcs autophosphorylation. DNA Repair (Amst) 2010;9(12):1307–14. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2010.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shen J, et al. Mutations in PNKP cause microcephaly, seizures and defects in DNA repair. Nat Genet. 2010;42(3):245–9. doi: 10.1038/ng.526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McKinnon PJ. ATM and ataxia telangiectasia. EMBO reports. 2004;5(8):772–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wyman C, Kanaar R. DNA double-strand break repair: all’s well that ends well. Annu Rev Genet. 2006;40:363–83. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.40.110405.090451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Carney JP, et al. The hMre11/hRad50 protein complex and Nijmegen breakage syndrome: linkage of double-strand break repair to the cellular DNA damage response. Cell. 1998;93(3):477–86. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81175-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Polo SE, Jackson SP. Dynamics of DNA damage response proteins at DNA breaks: a focus on protein modifications. Genes Dev. 2011;25(5):409–33. doi: 10.1101/gad.2021311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Abraham RT. Cell cycle checkpoint signaling through the ATM and ATR kinases. Genes Dev. 2001;15(17):2177–96. doi: 10.1101/gad.914401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tian B, Yang Q, Mao Z. Phosphorylation of ATM by Cdk5 mediates DNA damage signalling and regulates neuronal death. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11(2):211–8. doi: 10.1038/ncb1829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dobbin MM, et al. SIRT1 collaborates with ATM and HDAC1 to maintain genomic stability in neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16(8):1008–15. doi: 10.1038/nn.3460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gardiner M, et al. Identification and characterization of FUS/TLS as a new target of ATM. Biochem J. 2008;415(2):297–307. doi: 10.1042/BJ20081135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Herzog KH, et al. Requirement for Atm in ionizing radiation-induced cell death in the developing central nervous system. Science. 1998;280(5366):1089–91. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5366.1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.LeDoux SP, et al. Mitochondrial DNA repair: a critical player in the response of cells of the CNS to genotoxic insults. Neuroscience. 2007;145(4):1249–59. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mecocci P, et al. Oxidative damage to mitochondrial DNA shows marked age-dependent increases in human brain. Ann Neurol. 1993;34(4):609–16. doi: 10.1002/ana.410340416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wallace DC. A mitochondrial paradigm of metabolic and degenerative diseases, aging, and cancer: a dawn for evolutionary medicine. Annu Rev Genet. 2005;39:359–407. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.39.110304.095751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Richter C, Park JW, Ames BN. Normal oxidative damage to mitochondrial and nuclear DNA is extensive. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85(17):6465–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.17.6465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cha MY, Kim DK, Mook-Jung I. The role of mitochondrial DNA mutation on neurodegenerative diseases. Exp Mol Med. 2015;47:e150. doi: 10.1038/emm.2014.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Stierum RH, Dianov GL, Bohr VA. Single-nucleotide patch base excision repair of uracil in DNA by mitochondrial protein extracts. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27(18):3712–9. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.18.3712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Liu P, Demple B. DNA repair in mammalian mitochondria: Much more than we thought? Environ Mol Mutagen. 2010;51(5):417–26. doi: 10.1002/em.20576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yang JL, et al. Mitochondrial DNA damage and repair in neurodegenerative disorders. DNA Repair (Amst) 2008;7(7):1110–20. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2008.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Boesch P, et al. DNA repair in organelles: Pathways, organization, regulation, relevance in disease and aging. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1813(1):186–200. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ludwig DL, et al. A murine AP-endonuclease gene-targeted deficiency with post-implantation embryonic progression and ionizing radiation sensitivity. Mutat Res. 1998;409(1):17–29. doi: 10.1016/s0921-8777(98)00039-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Xanthoudakis S, et al. The redox/DNA repair protein, Ref-1, is essential for early embryonic development in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93(17):8919–23. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.17.8919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Li MX, et al. Targeting truncated APE1 in mitochondria enhances cell survival after oxidative stress. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;45(5):592–601. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lakshmipathy U, Campbell C. Mitochondrial DNA ligase III function is independent of Xrcc1. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28(20):3880–6. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.20.3880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Simsek D, et al. Crucial role for DNA ligase III in mitochondria but not in Xrcc1-dependent repair. Nature. 2011;471(7337):245–8. doi: 10.1038/nature09794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gao Y, et al. DNA ligase III is critical for mtDNA integrity but not Xrcc1-mediated nuclear DNA repair. Nature. 2011;471(7337):240–4. doi: 10.1038/nature09773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Katyal S, McKinnon PJ. Disconnecting XRCC1 and DNA ligase III. Cell Cycle. 2011;10(14):2269–75. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.14.16495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kaniak-Golik A, Skoneczna A. Mitochondria-nucleus network for genome stability. Free Radic Biol Med. 2015;82:73–104. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ledoux SP, et al. Glial cell-specific differences in response to alkylation damage. Glia. 1998;24(3):304–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hollensworth SB, et al. Glial cell type-specific responses to menadione-induced oxidative stress. Free Radic Biol Med. 2000;28(8):1161–74. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00214-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ellwanger JH, et al. Selenium reduces bradykinesia and DNA damage in a rat model of Parkinson’s disease. Nutrition. 2015;31(2):359–65. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2014.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Deng Q, et al. FUS is phosphorylated by DNA-PK and accumulates in the cytoplasm after DNA damage. J Neurosci. 2014;34(23):7802–13. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0172-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Markkanen E, Meyer U, Dianov GL. DNA Damage and Repair in Schizophrenia and Autism: Implications for Cancer Comorbidity and Beyond. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17(6) doi: 10.3390/ijms17060856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Raza MU, et al. DNA Damage in Major Psychiatric Diseases. Neurotox Res. 2016;30(2):251–67. doi: 10.1007/s12640-016-9621-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mao P, Reddy PH. Aging and amyloid beta-induced oxidative DNA damage and mitochondrial dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease: implications for early intervention and therapeutics. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1812(11):1359–70. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2011.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.McLachlan DR, et al. Chromatin structure in dementia. Ann Neurol. 1984;15(4):329–34. doi: 10.1002/ana.410150405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Cotman CW, Su JH. Mechanisms of neuronal death in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Pathol. 1996;6(4):493–506. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1996.tb00878.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Mullaart E, et al. Increased levels of DNA breaks in cerebral cortex of Alzheimer’s disease patients. Neurobiol Aging. 1990;11(3):169–73. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(90)90542-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Bradley MA, et al. Elevated 4-hydroxyhexenal in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) progression. Neurobiol Aging. 2012;33(6):1034–44. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bradley MA, Markesbery WR, Lovell MA. Increased levels of 4-hydroxynonenal and acrolein in the brain in preclinical Alzheimer disease. Free Radic Biol Med. 2010;48(12):1570–6. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Gabbita SP, Lovell MA, Markesbery WR. Increased nuclear DNA oxidation in the brain in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurochem. 1998;71(5):2034–40. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.71052034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lovell MA, Gabbita SP, Markesbery WR. Increased DNA oxidation and decreased levels of repair products in Alzheimer’s disease ventricular CSF. J Neurochem. 1999;72(2):771–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0720771.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lovell MA, Soman S, Bradley MA. Oxidatively modified nucleic acids in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease (PCAD) brain. Mech Ageing Dev. 2011;132(8–9):443–8. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]