Abstract

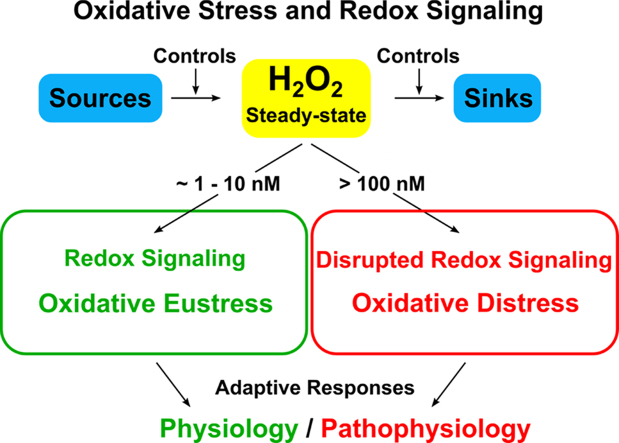

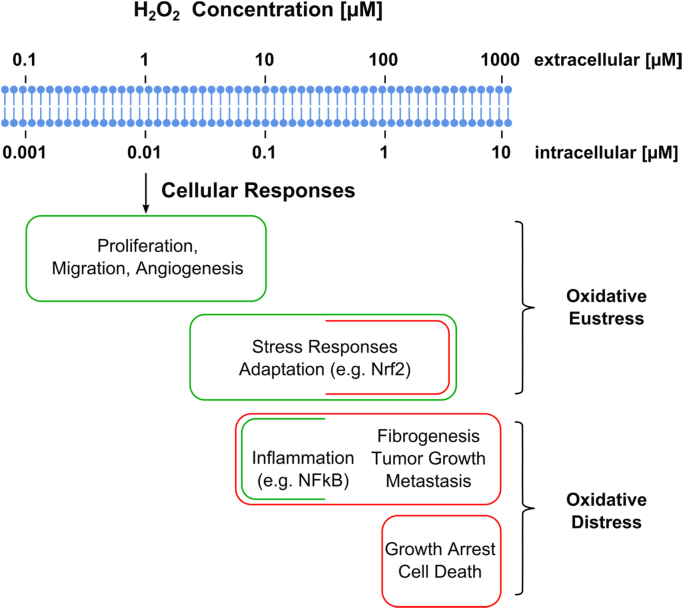

Hydrogen peroxide emerged as major redox metabolite operative in redox sensing, signaling and redox regulation. Generation, transport and capture of H2O2 in biological settings as well as their biological consequences can now be addressed. The present overview focuses on recent progress on metabolic sources and sinks of H2O2 and on the role of H2O2 in redox signaling under physiological conditions (1–10 nM), denoted as oxidative eustress. Higher concentrations lead to adaptive stress responses via master switches such as Nrf2/Keap1 or NF-κB. Supraphysiological concentrations of H2O2 (>100 nM) lead to damage of biomolecules, denoted as oxidative distress. Three questions are addressed: How can H2O2 be assayed in the biological setting? What are the metabolic sources and sinks of H2O2? What is the role of H2O2 in redox signaling and oxidative stress?

Keywords: Oxidative stress, NADPH oxidases, Mitochondria, Peroxiporins, Redox regulation, H2O2

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

H2O2 is operative in redox sensing and redox signaling.

-

•

H2O2 reacts with metal centers and with sulfur/selenium compounds.

-

•

H2O2 links redox biology to phosphorylation/dephosphorylation.

-

•

Physiological (low-level, nM) steady-state of H2O2 is maintained in oxidative eustress.

-

•

Supraphysiological (pathological) level of H2O2 leads to oxidative distress.

1. Introduction

Surprisingly (or unsurprisingly, in hindsight) hydrogen peroxide emerged as the major redox metabolite operative in redox sensing, signaling and redox regulation (see [1] for recent review)·H2O2 is recognized as being in the forefront of transcription-independent signal molecules, in one line with Ca2+ and ATP [2], [3]. As a messenger molecule, H2O2 diffuses through cells and tissues to initiate immediate cellular effects, such as cell shape changes, initiation of proliferation and recruitment of immune cells. It became clear that H2O2 serves fundamental regulatory functions in metabolism beyond the role as damage signal [4]. The metabolic and regulatory role of this oxygen metabolite has been increasingly recognized [5]. It serves as a key molecule in the Third Principle of the Redox Code, which is: “Redox sensing through activation/deactivation cycles of H2O2 production linked to the NAD and NADP systems to support spatiotemporal organisation of key processes” [6]·H2O2 occurs in normal metabolism in mammalian cells [7] and is a key metabolite in oxidative stress (see [8]). The term “oxidative eustress” [9], [10], which denotes physiological oxidative stress, may serve in the distinction from excessive load, “oxidative distress”, causing oxidative damage (see also [11], [12], [13], [14]). The general concept of eustress vs. distress was formulated in Refs. [15], [16].

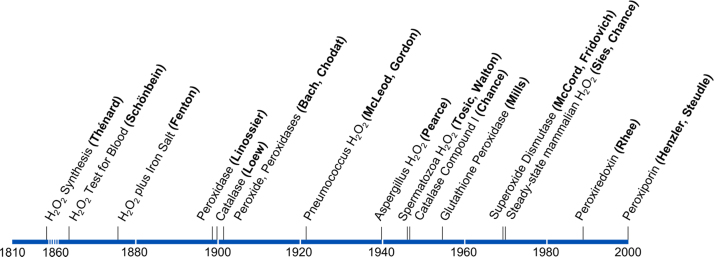

2. Timeline: hydrogen peroxide in chemistry and biology

Shortly after the discovery of oxygen by Lavoisier, Scheele and Priestley in the late 18th century it was Thénard who, in 1818, first synthesized H2O2 and found that blood disintegrates it. The role of H2O2 in cellular respiration was a matter of intense debate between Otto Warburg and Heinrich Wieland in the 1920's. The early detection of H2O2 efflux from pneumococcus or from aspergillus focused on cell-killing properties. It took until 1970 that the physiological occurrence of H2O2 as a normal attribute of mammalian metabolism was demonstrated. The timeline (Fig. 1) also shows the appearance, on the horizon of research, of the Fenton reaction and the naming of peroxidases and catalase in the 19th century. Glutathione peroxidase (Mills), superoxide dismutase (McCord and Fridovich) and peroxiredoxins (Rhee) were further milestones. The transport of H2O2 across membranes by water channels (Henzler and Steudle), by specific aquaporins designated as peroxiporins, concluded that development in the 20th century.

Fig. 1.

Timeline of hydrogen peroxide in chemistry and biology.

3. How can H2O2 be assayed in the biological setting?

3.1. Steady-state of catalase Compound I

Hydrogen peroxide is now well-known as a normal metabolite of oxygen in aerobic metabolism of cells and tissues. As mentioned, this was first shown in 1970 by the detection, in the near-infrared, of catalase Compound I in the intact perfused liver [7]. Catalase Compound I is the product of the reaction of H2O2 with catalase hame, denoted here in a simplified manner (Reaction (1)) [17], [18]. It can decompose upon reaction with a second H2O2 molecule in the catalatic reaction, releasing oxygen (Reaction (2)), or it can decompose in the peroxidatic reaction with a hydrogen donor AH2, e.g. methanol (Reaction 3):

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

The charge-transfer band of catalase Compound I at 660 nm [17] is useful for spectrophotometry of cells or organs because of low light-scattering and practically no optical interference by other pigments in the near-infrared region of the spectrum. Unequivocal proof of the existence of H2O2 in normally respiring liver cells was provided by noninvasive organ spectroscopy: Catalase Compound I was shown to decrease rapidly when the oxygen concentration was lowered and, importantly, when a hydrogen donor (e.g. methanol) for the peroxidatic reaction (Reaction (iii)) of catalase was infused [7]. Using stepwise ‘titration’ with low methanol concentrations, the rate of cellular H2O2 production was determined to be 50 nmol H2O2 per gram of liver wet weight per min, which corresponds to 2–3% of total oxygen uptake [19]. That rate was increased in several metabolic conditions (Table 1) [19]. The method has also been used with isolated hepatocytes, also shown in Table 1 [20]. The steady-state concentration of H2O2 in the intact cell, overall, was calculated to be of the order of 10 nM [19], [21]. Early methods to quantify H2O2 formation included assays of the peroxidatic reaction, e.g. the use of [14C]-methanol, and others [22], [23].

Table 1.

H2O2 production rate in intact liver or in isolated hepatocytes.

Intact hemoglobin-free perfused liver [19] or isolated hepatocyte [20] data were obtained by methanol titration of catalase Compound I. For discussion, see [4], [21].

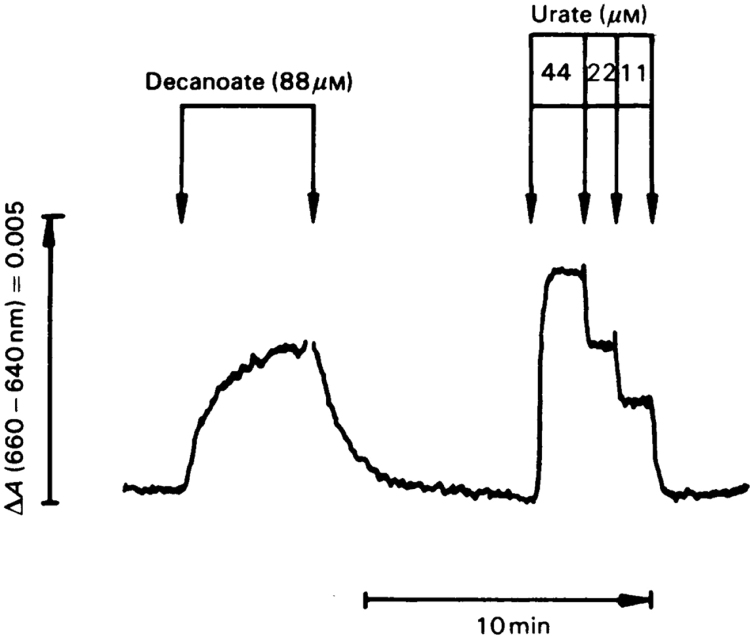

Another method of quantification of extra H2O2 production in intact cells is illustrated in Fig. 2. Upon infusion of decanoate as a fatty-acid substrate for H2O2 production, there is an increase in the catalase Compound I signal at 660–640 nm, which can be calibrated against that obtained with infusion of urate, a substrate producing known amounts of H2O2 by urate oxidase [22], [23]. In isolated hepatocytes, a comparison of endogenous H2O2 production rates with the catalatic evolution of O2 from infused H2O2 provided another means to analyse Compound I steady-states [24].

Fig. 2.

Quantification of H2O2 production in intact perfused rat liver during decanoate oxidation. Catalase Compound I is monitored at 660–640 nm continuously against time by organ spectrophotometry. Calibration of the decanoate response is performed against the urate response. With the 1:1 stoichiometry of urate:H2O2 and measurement of the rate of urate removal in the effluent perfusate, the decanoate response is quantified to indicate an extra H2O2 production of 80 nmol H2O2/min per gram liver wet weight in this experiment. For details, see [22], [23].

3.2. Genetically encoded fluorescent protein indicators of H2O2

The development of the HyPer probe as genetically encoded fluorescent indicator for H2O2 in intact cells and tissues was a landmark [25]. This new type of probe provided insight into spatiotemporal organisation [26]. Thus, it became possible to examine the dynamics of H2O2 in subcellular compartments [27]. HyPer is also sensitive to pH. Dissection of pH responses from responses in H2O2 is possible with the SypHer [28] and SypHer2 probes [29].

Probes such as roGFP2-Orp1 provide another type of tool for assaying H2O2, exhibiting kinetics of oxidation and reduction similar to HyPer [30], [31]. Real-time monitoring of basal H2O2 levels has been used with peroxiredoxin-based probes [32].

3.3. Exomarkers,’nonredox’ exogenous probes;small molecule fluorescent markers

A variety of other approaches for H2O2 detection is available, not to be discussed here in detail (e.g. [33], [34], [35]).

4. What are the metabolic sources and sinks of H2O2?

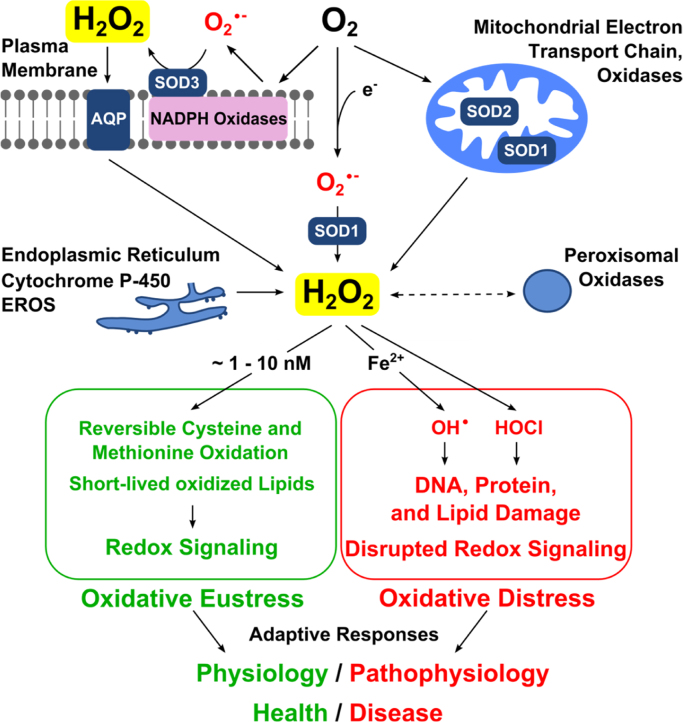

4.1. Sources: NAD(P)H oxidases, mitochondrial respiratory chain, diverse oxidases

Numerous one- or two-electron reduction reactions have been identified as sources of H2O2 (Fig. 3). The major enzymatic generators are the NADPH oxidases (Nox) [36], [37] and the mitochondrial respiratory chain [38], [39], [40], as well as a considerable number of oxidases. A total of 31 human cellular hydrogen peroxide generating enzymes has been compiled [41]. The one-electron reduction sources are functionally tightly linked to the superoxide dismutases, SOD1, SOD2, SOD3, with their cytosolic, mitochondrial matrix and extracellular locations, respectively. Other cell compartments also contribute to H2O2 production, e.g. the endoplasmic reticulum and the peroxisomes.

Fig. 3.

Role of hydrogen peroxide in oxidative stress. Top: Endogenous H2O2 sources include NADPH oxidases and other oxidases (membrane-bound or free) as well as the mitochondria. The superoxide anion radical is converted to hydrogen peroxide by the three superoxide dismutases (SODs 1,2,3). Hydrogen peroxide diffusion across membranes occurs by some aquaporins (AQP), known as peroxiporins. Bottom: In green, redox signaling comprises oxidative eustress (physiological oxidative stress). In red, excessive oxidative stress leads to oxidative damage of biomolecules and disrupted redox signaling, oxidative distress. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

4.2. Sinks: catalases, peroxidases, peroxiredoxins

While the catalatic reaction of catalase (Reactions (i) and (ii)) is a dismutation reaction, regenerating one molecule of oxygen, the other sinks of H2O2 lead to water by reduction. Certain cysteinyl residues in peroxiredoxins or selenocysteinyl residues in glutathione peroxidases are highly reactive, the second-order rate constants for the reaction with H2O2 being of the order of 107 M-1s-1 (see [42]). A number of important peroxidases utilize H2O2 as substrate, e.g. myeloperoxidase, eosinophil peroxidase, lactoperoxidase.

The relative contributions of catalase and glutathione peroxidase in H2O2 removal depend on the site of generation and the enzymatic equipment [43], [44], [45], [46]. Catalase is a predominantly peroxisomal enzyme. Therefore, it is either a localized sink for H2O2 produced by peroxisomal oxidases, or peroxisomes can be a sink at the cell-scale level (see comment further below). An overall assay for the rate of removal of extracellular hydrogen peroxide has been developed for cell culture experiments [47].

4.3. H2O2 Compartmentation: role of aquaporins as peroxiporins

Aquaporins (AQP) facilitate H2O2 to cross membranes [48]. Specific AQPs play a functional role in H2O2 translocation, for which they are called peroxiporins [49], [50].

4.4. Spatiotemporal control, H2O2 nanodomains

Spatial distribution of H2O2 in cells and tissues is not uniform. There are substantial gradients, both from extracellular to intercellular and between subcellular spaces [51], [52], [53]. It appears from a search of the available literature that H2O2 concentration in blood plasma is about 1–5 µM [54], which would be more than 100-fold higher than that estimated to occur within cells (see Fig. 4). Interestingly, even within subcellular organelles, there are H2O2 gradients·H2O2 in the mitochondrial cristae space originates largely from mitochondrial Complex III, whereas mitochondrial Complexes I and II contribute to mitochondrial matrix H2O2 [55]. In the cristae subspace “redox nanodomains” have been described, which are induced by and control calcium signaling at the ER-mitochondrial interface [56]·H2O2 transients sensitize calcium ion release to maintain calcium oscillations [56].

Fig. 4.

Estimated ranges of hydrogen peroxide concentration in oxidative stress with regard to cellular responses. The intracellular physiological range likely spans between 1 and 10 up to approx. 100 nM H2O2; the arrow indicates data from normally metabolizing liver. Stress and adaptive stress responses occur at higher concentrations. Even higher exposure leads to inflammatory response, growth arrest and cell death by various mechanisms. Green and red coloring denotes predominantly beneficial or deleterious responses, respectively. An estimated 100-fold concentration gradient from extracellular to intracellular is given for rough orientation; this gradient will vary with cell type, location inside cells and the activity of enzymatic sinks (see text). (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

There are also circadian redox oscillations, and these are likely to comprise oscillations in H2O2 concentration. Peroxiredoxins exhibit pronounced circadian rhythmicity [57], [58]. There is reciprocal control of the circadian clock and the cellular redox state (see [59]).

The thioredoxin reductase-1/thioredoxin [60] and glutathione reductase/glutathione systems [61] appear to control the actions of H2O2 on master switches such as Nrf2/Keap1. Nuclear and cytosolic peroxiredoxin-1 differentially regulate NF-κB activities, indicating that the balance in subcellular H2O2 metabolism provides specificity in redox signaling [62].

For orientation on H2O2 concentration ranges, Fig. 4 presents physiological ranges, spanning from normal processes to adaptive ones (stress responses), denoted as “oxidative eustress”. Higher concentrations evoking inflammatory responses and others, ultimately leading to growth arrest and cell death, are denoted as “oxidative distress”. It may be mentioned that it is difficult to conceptually discern between these ranges, because inflammation, for example, certainly includes elements positive for the organism, such as phagocyte activity. So does autophagy [63], [64], mitophagy [65] and cell death in the forms of apoptosis, ferroptosis and necroptosis [66]. Assignment of a given H2O2 concentration to the category of eustress or of distress may vary with cell type, with the level of complexity (comparison of isolated cell/tissue and the whole organism), or with the duration of the exposure to H2O2. Considering the level of the whole organism, mucosal barrier tissues participate in immune defense against infection. The release of nano- to submicromolar H2O2 was shown to disrupt the tyrosine phosphorylation network in several bacterial pathogens as a host-initiated antivirulence strategy [67].

Estimations of kinetic parameters of H2O2 interactions have been performed, and models were established to improve our understanding of the complex processes in redox signaling [68], [69], [70], [71].

In Fig. 4, the gradient between extracellular and intracellular H2O2 concentrations is indicated, as rough orientation, to be about 100-fold, which is 10-fold higher than previous estimations [5]. Recent calculations based on results obtained with genetically encoded H2O2 probes came to even higher values, 200- to 500-fold [72] or 650-fold [52]; these rely on the information from the intracellular subspace where the detector probe is located. It is conceivable, of course, that there are spaces with even zero H2O2 concentration, which would make the gradient tend toward infinity.

5. What is the role of H2O2 in redox signaling and oxidative stress?

5.1. Mechanism

Because of its physicochemical properties, H2O2 is capable of serving as messenger to carry a redox signal from the site of its generation to a target site. Among the various oxygen metabolites, H2O2 is considered most suitable for redox signaling [1], [73]. Redox regulation can take place via control of single enzymatic activity or at the transcriptional level. Hydrogen peroxide modulates the activity of transcription factors: in bacteria (OxyR and PerR) (see [74]), in lower eukaryotes (Yap1, Maf1, Hsf1 and Msn2/4) and in mammalian cells (AP-1, NRF2, CREB, HSF1, HIF-1, TP53, NF-κB, NOTCH, SP1 and SCREB-1) (see [1]).

The major impact on redox regulation occurs via the thiol peroxidases (see Sinks above) [75], which involves, to a large degree, reversible protein cysteine oxidation to the sulfenylated form (Fig. 3) [76], [77], [78]. According to the Second Principle of the Redox Code, “the redox proteome is organized through kinetically controlled sulfur switches linked to NAD and NADP systems” [6], and H2O2 plays a central role in it as an oxidant.

The linkage of redox reactions to protein phosphorylation/dephosphorylation is given by the redox sensitivity of proteine tyrosine phosphatases (PTP). Thus, oxidation and thereby inactivation of PTPs would increase steady-state protein phosphorylation. Examples are PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homolog), Cdc25 phosphatases, and PTP1B (protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B) (see [79]).

Protein phosphatase 1 (PP1) is redox-inhibited by oxidation of its metal center [80]. The intracellular labile iron pool is a determinant of H2O2-induced redox signaling [81], [82].

5.2. Targets

It follows that specificity and fine-tuning is exerted through control of sources and sinks. Regarding sources, the fine-control of NADPH oxidases by physical and chemical cues is pivotal (see [83]). Mitochondrial control by redox switches coordinates protein activity, localization and stability (see [84], [85]). The cysteine redox proteome has been studied thoroughly [41], [86], [87]. The median percentage oxidation of cysteine residues in the proteome is between 5% and 12%, and this can be increased to >40% by adding oxidants [86]. Regarding sinks, much interest has focused on the peroxiredoxins [88]. For example, peroxiredoxin-2 acts as highly sensitive primary H2O2 receptor which specifically transmits oxidative equivalents to the redox-regulated transcription factor STAT3, forming a redox relay for H2O2 redox signaling [89].

5.3. Processes

As many fundamental biological processes have a component of redox control, exhaustive coverage is beyond the scope of the present article. Major such processes are hypoxia, inflammation (“inflammasome“), autophagy, apoptosis, wound healing, proliferation, muscle contraction, circadian rhythm, stem cell self-renewal, tumorigenesis and aging (see above and Refs. [8], [90]).

Here, just a few recent aspects may be mentioned which illustrate the growing recognition of H2O2 in direct involvement: Laminar shear-stress mediates H2O2 formation in bovine aortic endothelial cells [91]. NADPH oxidase 4 (Nox4) has a protective vascular function, its deletion causes apoptosis [92]. Nox4 contributes considerably, by about one-third, to cellular H2O2 formation in vascular endothelium [92]. The redox inhibition of protein phosphatase 1, mentioned above, by Nox4 regulates elF2-alpha-mediated stress signaling [80]. Specialized cell-types such as vascular smooth muscle cells are good examples of the complex nature of the role of H2O2 in pathophysiology [93].

In injured zebrafish larvae, a newly generated H2O2 gradient mediates rapid leukocyte recruitment [94]. Cell proliferation subsequent to amputation of the tail of tadpoles involves increases in H2O2 concentration, as indicated by the HyPer probe (assuming that pH effects do not contribute significantly to the signal) [95]. The transients in H2O2 are embedded in concerted action with other signals in the process of wound responses mentioned in the Introduction above [96]·H2O2 controls axon pathfinding of retinal ganglion cells projecting towards the tectum in zebrafish [97].

The control of H2O2 gradients by peroxiporins (see above) allows for further possibilities of fine-tuning with impact on cell signaling and survival, as shown for AQP8 [98]. AQP3 is required for Nox-derived H2O2 signaling upon growth factor stimulation [99]. AQP3 was also shown to mediate H2O2 uptake to regulate downstream signaling in tumor necrosis factor-dependent activation of NF-κB [100]. The endoplasmic reticulum membrane is recognized as another important site of modulation of H2O2 traffic by aquaporins, notably by AQP11 [101].

6. Outlook

While encouraging progress has been made in understanding the biological significance of low levels of H2O2 in cells and tissues, much is yet to be discovered. New tools with improved sensitivity, specificity and selectivity promise better insight into spatiotemporal organisation by dynamic imaging [102], [103].

6.1. Quantification and imaging: the “H2O2 landscape”

The detailed description of the spatial and temporal pattern of H2O2 concentrations in cells and tissues is a major challenge. Overall intracellular H2O2 production rates as given in Table 1 can serve as a first approximation. Clearly, substantial subcellular gradients exist, from practically zero H2O2 concentration to localized high concentrations e.g. in vesicles. The use of catalase Compound I for assaying H2O2 steady-states rests on a number of conditions, not elaborated here in detail; it could be argued that there is overestimation or, conversely, underestimation of total cellular rates and subcellular concentrations of H2O2, depending e.g. on the activity of peroxiredoxins. While it is uncontested that catalase is located in the peroxisomal matrix, other locations of catalase activity are also relevant, such as the mitochondria [104] and even the extracellular space [105]. Using D-amino acid oxidase as genetically encoded producer of H2O2, in conjunction with the fused HyPer probe, it becomes possible to examine intracellular H2O2 dynamics quantitatively [106]·H2O2 microdomains in receptor tyrosine kinase signaling are now amenable to imaging [107].

Mitochondrial dynamics in terms of fusion and fission is subjected to short-term regulation by redox signaling [108]. Conversely, the assembly of mitochondrial Complex I into supercomplexes determines, for example, the differential production of reactive oxygen species in neurons and astrocytes [109]. Addressing specific sites of mitochondrial H2O2 production may have therapeutic potential [110].

6.2. Broader context: relation to Ca2+

The distinction of oxidative eustress and oxidative distress may occur at a fine borderline, embedded in other fundamental control systems regulated by ion signals, notably calcium ions [111], [112], [113]. The H2O2 nanodomains mentioned above [56] support the emerging concept that Ca2+ signaling and the luminal redox state of the endoplasmic reticulum are intertwined, especially at the mitochondria-associated membranes (MAM) [114], [115]. Associated pH transients are accessible as well [29].

Modulation and propagation of H2O2 signals is also subject to intercellular communication. The microenvironment surrounding particular cells, notably the extracellular matrix (ECM), modifies the signal [116]. Gap junctional communication via connexin channels between cells may lead to “local oxidative stress expansion” [117].

6.3. Note

This article focused on H2O2 as a central redox signaling molecule. Other reactive oxygen species and reactive nitrogen species, not treated here, also have a role in redox regulation. For example, the superoxide anion radical reacts with FeS-centers, e.g. in aconitase, and by its reaction with nitric oxide peroxynitrite is formed which, in turn, modifies proteins by tyrosine nitration. S-Glutathionylation processes as well as reactions of hydrogen sulfide and its congeners are also important. This is illustrated by the secretion of S-glutathionylated proteins under oxidative stress [118].

6.4. Upshot

The concept of constitutive cellular low-level H2O2 steady-states is gaining increasing recognition. The localized function in modulating and maintaining key target functions by redox reactions is the essence of physiological oxidative stress, called oxidative eustress. Localized high levels of H2O2 occur in oxidative distress, exemplified by cell-killing in the respiratory burst of neutrophils [119] or in toxicity studies [120] involving H2O2 generation. A challenge for refined analysis will be the spatiotemporal and functional dissection of these two extremes in cells and tissues.

Acknowledgements

Fruitful discussions with Wilhelm Stahl and Carsten Berndt in Düsseldorf as well as helpful comments by Fernando Antunes, Vsevolod Belousov, Victor Darley-Usmar, Dean Jones, Wim Koppenol and Santiago Lamas are gratefully acknowledged. H.S. is a Fellow of the National Foundation for Cancer Research (NFCR), Bethesda.

Footnotes

This article is based, in part, on a lecture entitled “Oxidative Stress and Redox Signaling: Role of Hydrogen Peroxide”, which was presented at the XI Reunion del Grupo Espanol de Investigacion en Radicales Libres (GEIRLI), September 13, 2016, at Granada, Spain.

References

- 1.Marinho H.S., Real C., Cyrne L., Soares H., Antunes F. Hydrogen peroxide sensing, signaling and regulation of transcription factors. Redox. Biol. 2014;2:535–562. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2014.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cordeiro J.V., Jacinto A. The role of transcription-independent damage signals in the initiation of epithelial wound healing. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2013;14:249–262. doi: 10.1038/nrm3541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van der Vliet A., Janssen-Heininger Y.M. Hydrogen peroxide as a damage signal in tissue injury and inflammation: murderer, mediator, or messenger? J. Cell Biochem. 2014;115:427–435. doi: 10.1002/jcb.24683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sies H. Role of metabolic H2O2 generation: redox signaling and oxidative stress. J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289:8735–8741. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R113.544635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stone J.R., Yang S. Hydrogen peroxide: a signaling messenger. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2006;8:243–270. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones D.P., Sies H. The Redox Code. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2015;23:734–746. doi: 10.1089/ars.2015.6247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sies H., Chance B. The steady state level of catalase compound I in isolated hemoglobin-free perfused rat liver. FEBS Lett. 1970;11:172–176. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(70)80521-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sies H., Berndt C., Jones D.P. Oxidative stress. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2017;86 doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-061516-045037. (xxx-xxx) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sarsour E.H., Kalen A.L., Goswami P.C. Manganese superoxide dismutase regulates a redox cycle within the cell cycle. Antioxid. Redox. Signal. 2014;20:1618–1627. doi: 10.1089/ars.2013.5303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Niki E. Oxidative stress and antioxidants: distress or eustress? Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2016;595:19–24. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2015.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aschbacher K., O'Donovan A., Wolkowitz O.M., Dhabhar F.S., Su Y., Epel E. Good stress, bad stress and oxidative stress: insights from anticipatory cortisol reactivity. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013;38:1698–1708. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2013.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li G., He H. Hormesis, allostatic buffering capacity and physiological mechanism of physical activity: a new theoretic framework. Med. Hypotheses. 2009;72:527–532. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2008.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lushchak V.I. Free radicals, reactive oxygen species, oxidative stress and its classification. Chem Biol. Interact. 2014;224C:164–175. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2014.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ursini F., Maiorino M., Forman H.J. Redox homeostasis: the golden mean of healthy living. Redox. Biol. 2016;8:205–215. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2016.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lazarus R.S. McGraw-Hill; New York: 1966. Psychological stress and the coping process. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Selye H. Lippincott; Philadelphia: 1974. Stress without distress. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brill A.S., Williams R.J. Primary compounds of catalase and peroxidase. Biochem. J. 1961;78:253–262. doi: 10.1042/bj0780253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chance B., Schonbaum G.R. The nature of the primary complex of catalase. J. Biol. Chem. 1962;237:2391–2395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oshino N., Chance B., Sies H., Bücher T. The role of H2O2 generation in perfused rat liver and the reaction of catalase compound I and hydrogen donors. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1973;154:117–131. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(73)90040-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jones D.P., Thor H., Andersson B., Orrenius S. Detoxification reactions in isolated hepatocytes. Role of glutathione peroxidase, catalase, and formaldehyde dehydrogenase in reactions relating to N-demethylation by the cytochrome P-450 system. J. Biol. Chem. 1978;253:6031–6037. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chance B., Sies H., Boveris A. Hydroperoxide metabolism in mammalian organs. Physiol Rev. 1979;59:527–605. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1979.59.3.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Foerster E.C., Fährenkemper T., Rabe U., Graf P., Sies H. Peroxisomal fatty acid oxidation as detected by H2O2 production in intact perfused rat liver. Biochem. J. 1981;196:705–712. doi: 10.1042/bj1960705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sies H. Measurement of hydrogen peroxide formation in situ. Methods Enzymol. 1981;77:15–20. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(81)77005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jones D.P. Intracellular catalase function: analysis of the catalatic activity by product formation in isolated liver cells. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1982;214:806–814. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(82)90087-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Belousov V.V., Fradkov A.F., Lukyanov K.A., Staroverov D.B., Shakhbazov K.S. Genetically encoded fluorescent indicator for intracellular hydrogen peroxide. Nat. Methods. 2006;3:281–286. doi: 10.1038/nmeth866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ermakova Y.G., Bilan D.S., Matlashov M.E., Mishina N.M., Markvicheva K.N. Red fluorescent genetically encoded indicator for intracellular hydrogen peroxide. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:5222. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Malinouski M., Zhou Y., Belousov V.V., Hatfield D.L., Gladyshev V.N. Hydrogen peroxide probes directed to different cellular compartments. PLoS. One. 2011;6:e14564. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Poburko D., Santo-Domingo J., Demaurex N. Dynamic regulation of the mitochondrial proton gradient during cytosolic calcium elevations. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:11672–11684. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.159962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matlashov M.E., Bogdanova Y.A., Ermakova G.V., Mishina N.M., Ermakova Y.G. Fluorescent ratiometric pH indicator SypHer2: applications in neuroscience and regenerative biology. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2015;1850:2318–2328. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2015.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Albrecht S.C., Barata A.G., Grosshans J., Teleman A.A., Dick T.P. In vivo mapping of hydrogen peroxide and oxidized glutathione reveals chemical and regional specificity of redox homeostasis. Cell Metab. 2011;14:819–829. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gutscher M., Sobotta M.C., Wabnitz G.H., Ballikaya S., Meyer A.J. Proximity-based protein thiol oxidation by H2O2-scavenging peroxidases. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:31532–31540. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.059246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morgan B., Van L.K., Owusu T.N., Ezerina D., Pastor-Flores D. Real-time monitoring of basal H2O2 levels with peroxiredoxin-based probes. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2016;12:437–443. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brewer T.F., Garcia F.J., Onak C.S., Carroll K.S., Chang C.J. Chemical approaches to discovery and study of sources and targets of hydrogen peroxide redox signaling through NADPH oxidase proteins. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2015;84:765–790. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060614-034018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Logan A., Cocheme H.M., Li Pun P.B., Apostolova N., Smith R.A. Using exomarkers to assess mitochondrial reactive species in vivo. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2014;1840:923–930. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2013.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Winterbourn C.C. The challenges of using fluorescent probes to detect and quantify specific reactive oxygen species in living cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2014;1840:730–738. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2013.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bedard K., Krause K.H. The NOX family of ROS-generating NADPH oxidases: physiology and pathophysiology. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:245–313. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00044.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lassègue B., San M.A., Griendling K.K. Biochemistry, physiology, and pathophysiology of NADPH oxidases in the cardiovascular system. Circ. Res. 2012;110:1364–1390. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.243972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brand M.D. Mitochondrial generation of superoxide and hydrogen peroxide as the source of mitochondrial redox signaling. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2016;100:14–31. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2016.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mailloux R.J. Teaching the fundamentals of electron transfer reactions in mitochondria and the production and detection of reactive oxygen species. Redox. Biol. 2015;4:381–398. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2015.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Murphy M.P. How mitochondria produce reactive oxygen species. Biochem. J. 2009;417:1–13. doi: 10.1042/BJ20081386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Go Y.M., Chandler J.D., Jones D.P. The cysteine proteome. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2015;84:227–245. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Winterbourn C.C. The biological chemistry of hydrogen peroxide. Methods Enzymol. 2013;528:3–25. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-405881-1.00001-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Antunes F., Han D., Cadenas E. Relative contributions of heart mitochondria glutathione peroxidase and catalase to H2O2 detoxification in in vivo conditions. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2002;33:1260–1267. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)01016-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jones D.P., Eklöw L., Thor H., Orrenius S. Metabolism of hydrogen peroxide in isolated hepatocytes: relative contributions of catalase and glutathione peroxidase in decomposition of endogenously generated H2O2. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1981;210:505–516. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(81)90215-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sies H., Gerstenecker C., Menzel H., Flohé L. Oxidation in the NADP system and release of GSSG from hemoglobin-free perfused rat liver during peroxidatic oxidation of glutathione by hydroperoxides. FEBS Lett. 1972;27:171–175. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(72)80434-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sies H., Summer K.H. Hydroperoxide-metabolizing systems in rat liver. Eur. J. Biochem. 1975;57:503–512. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1975.tb02325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wagner B.A., Witmer J.R., van 't Erve T.J., Buettner G.R. An assay for the rate of removal of extracellular hydrogen peroxide by cells. Redox. Biol. 2013;1:210–217. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2013.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Henzler T., Steudle E. Transport and metabolic degradation of hydrogen peroxide in Chara corallina: model calculations and measurements with the pressure probe suggest transport of H2O2 across water channels. J. Exp. Bot. 2000;51:2053–2066. doi: 10.1093/jexbot/51.353.2053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bienert G.P., Schjoerring J.K., Jahn T.P. Membrane transport of hydrogen peroxide. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2006;1758:994–1003. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bienert G.P., Moller A.L., Kristiansen K.A., Schulz A., Moller I.M. Specific aquaporins facilitate the diffusion of hydrogen peroxide across membranes. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:1183–1192. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603761200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Antunes F., Cadenas E. Estimation of H2O2 gradients across biomembranes. FEBS Lett. 2000;475:121–126. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01638-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Huang B.K., Sikes H.D. Quantifying intracellular hydrogen peroxide perturbations in terms of concentration. Redox. Biol. 2014;2:955–962. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2014.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Marinho H.S., Cyrne L., Cadenas E., Antunes F. The cellular steady-state of H2O2: latency concepts and gradients. Methods Enzymol. 2013;527:3–19. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-405882-8.00001-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Forman H.J., Bernardo A., Davies K.J. What is the concentration of hydrogen peroxide in blood and plasma? Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2016;603:48–53. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2016.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bleier L., Wittig I., Heide H., Steger M., Brandt U., Dröse S. Generator-specific targets of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2015;78:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2014.10.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Booth D.M., Enyedi B., Geiszt M., Varnai P., Hajnoczky G. Redox nanodomains are induced by and control calcium signaling at the ER-mitochondrial interface. Mol. Cell. 2016;63:240–248. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.05.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Edgar R.S., Green E.W., Zhao Y., van O.G., Olmedo M. Peroxiredoxins are conserved markers of circadian rhythms. Nature. 2012;485:459–464. doi: 10.1038/nature11088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kil I.S., Lee S.K., Ryu K.W., Woo H.A., Hu M.C. Feedback control of adrenal steroidogenesis via H2O2-dependent, reversible inactivation of peroxiredoxin III in mitochondria. Mol. Cell. 2012;46:584–594. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Putker M., O'Neill J.S. Reciprocal control of the circadian clock and cellular redox state - a critical appraisal. Mol. Cells. 2016;39:6–19. doi: 10.14348/molcells.2016.2323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cebula M., Schmidt E.E., Arnér E.S. TrxR1 as a potent regulator of the Nrf2-Keap1 response system. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2015;23:823–853. doi: 10.1089/ars.2015.6378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Espinosa-Diez C., Miguel V., Mennerich D., Kietzmann T., Sanchez-Perez P. Antioxidant responses and cellular adjustments to oxidative stress. Redox Biol. 2015;6:183–197. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2015.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hansen J.M., Moriarty-Craige S., Jones D.P. Nuclear and cytoplasmic peroxiredoxin-1 differentially regulate NF-kappaB activities. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2007;43:282–288. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.04.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lee J., Giordano S., Zhang J. Autophagy, mitochondria and oxidative stress: cross-talk and redox signalling. Biochem. J. 2012;441:523–540. doi: 10.1042/BJ20111451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Scherz-Shouval R., Elazar Z. Regulation of autophagy by ROS: physiology and pathology. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2011;36:30–38. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2010.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Frank M., Duvezin-Caubet S., Koob S., Occhipinti A., Jagasia R. Mitophagy is triggered by mild oxidative stress in a mitochondrial fission dependent manner. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2012;1823:2297–2310. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2012.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhang L., Wang K., Lei Y., Li Q., Nice E.C., Huang C. Redox signaling: potential arbitrator of autophagy and apoptosis in therapeutic response. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2015;89:452–465. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Alvarez L.A., Kovacic L., Rodriguez J., Gosemann J.H., Kubica M. NADPH oxidase-derived H2O2 subverts pathogen signaling by oxidative phosphotyrosine conversion to PB-DOPA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2016;113:10406–10411. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1605443113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Altintas A., Davidsen K., Garde C., Mortensen U.H., Brasen J.C. High-resolution kinetics and modeling of hydrogen peroxide degradation in live cells. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2016;101:143–153. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2016.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Brito P.M., Antunes F. Estimation of kinetic parameters related to biochemical interactions between hydrogen peroxide and signal transduction proteins. Front Chem. 2014;2:82. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2014.00082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lim J.B., Langford T.F., Huang B.K., Deen W.M., Sikes H.D. A reaction-diffusion model of cytosolic hydrogen peroxide. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2016;90:85–90. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Treberg J.R., Munro D., Banh S., Zacharias P., Sotiri E. Differentiating between apparent and actual rates of H2O2 metabolism by isolated rat muscle mitochondria to test a simple model of mitochondria as regulators of H2O2 concentration. Redox Biol. 2015;5:216–224. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2015.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bilan D.S., Pase L., Joosen L., Gorokhovatsky A.Y., Ermakova Y.G. HyPer-3: a genetically encoded H(2)O(2) probe with improved performance for ratiometric and fluorescence lifetime imaging. ACS Chem. Biol. 2013;8:535–542. doi: 10.1021/cb300625g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Forman H.J., Maiorino M., Ursini F. Signaling functions of reactive oxygen species. Biochemistry. 2010;49:835–842. doi: 10.1021/bi9020378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Imlay J.A. Transcription factors that defend bacteria against reactive oxygen species. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2015;69:93–108. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-091014-104322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Flohé L. The impact of thiol peroxidases on redox regulation. Free Radic. Res. 2016;50:126–142. doi: 10.3109/10715762.2015.1046858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Garcia-Santamarina S., Boronat S., Hidalgo E. Reversible cysteine oxidation in hydrogen peroxide sensing and signal transduction. Biochemistry. 2014;53:2560–2580. doi: 10.1021/bi401700f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Poole L.B., Karplus P.A., Claiborne A. Protein sulfenic acids in redox signaling. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2004;44:325–347. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.44.101802.121735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Poole L.B. The basics of thiols and cysteines in redox biology and chemistry. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2015;80:148–157. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2014.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Cho S.H., Lee C.H., Ahn Y., Kim H., Kim H. Redox regulation of PTEN and protein tyrosine phosphatases in H2O2 mediated cell signaling. FEBS Lett. 2004;560:7–13. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(04)00112-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Santos C.X., Hafstad A.D., Beretta M., Zhang M., Molenaar C. Targeted redox inhibition of protein phosphatase 1 by Nox4 regulates eIF2alpha-mediated stress signaling. EMBO J. 2016;35:319–334. doi: 10.15252/embj.201592394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Petrat F., de Groot H.,, Sustmann R., Rauen U. The chelatable iron pool in living cells: a methodically defined quantity. Biol. Chem. 2002;383:489–502. doi: 10.1515/BC.2002.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mantzaris M.D., Bellou S., Skiada V., Kitsati N., Fotsis T., Galaris D. Intracellular labile iron determines H2O2-induced apoptotic signaling via sustained activation of ASK1/JNK-p38 axis. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2016;97:454–465. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2016.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Nauseef W.M. Detection of superoxide anion and hydrogen peroxide production by cellular NADPH oxidases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2014;1840:757–767. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2013.04.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Reczek C.R., Chandel N.S. ROS-dependent signal transduction. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2015;33:8–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2014.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Riemer J., Schwarzländer M., Conrad M., Herrmann J.M. Thiol switches in mitochondria: operation and physiological relevance. Biol. Chem. 2015;396:465–482. doi: 10.1515/hsz-2014-0293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Go Y.M., Jones D.P. The redox proteome. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:26512–26520. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R113.464131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Yang J., Carroll K.S., Liebler D.C. The expanding landscape of the thiol redox proteome. Mol. Cell Proteom. 2016;15:1–11. doi: 10.1074/mcp.O115.056051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Rhee S.G., Woo H.A. Multiple functions of peroxiredoxins: peroxidases, sensors and regulators of the intracellular messenger H2O2, and protein chaperones. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2011;15:781–794. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sobotta M.C., Liou W., Stocker S., Talwar D., Oehler M. Peroxiredoxin-2 and STAT3 form a redox relay for H2O2 signaling. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2015;11:64–70. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Holmström K.M., Finkel T. Cellular mechanisms and physiological consequencesof redox-dependent signalling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2014;15:411–421. doi: 10.1038/nrm3801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sanchez-Gomez F.J., Calvo E., Breton-Romero R., Fierro-Fernandez M., Anilkumar N. NOX4-dependent hydrogen peroxide promotes shear stress-induced SHP2 sulfenylation and eNOS activation. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2015;89:419–430. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Schröder K., Zhang M., Benkhoff S., Mieth A., Pliquett R. Nox4 is a protective reactive oxygen species generating vascular NADPH oxidase. Circ. Res. 2012;110:1217–1225. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.267054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Byon C.H., Heath J.M., Chen Y. Redox signaling in cardiovascular pathophysiology: a focus on hydrogen peroxide and vascular smooth muscle cells. Redox Biol. 2016;9:244–253. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2016.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Niethammer P., Grabher C., Look A.T., Mitchison T.J. A tissue-scale gradient of hydrogen peroxide mediates rapid wound detection in zebrafish. Nature. 2009;459:996–999. doi: 10.1038/nature08119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Love N.R., Chen Y., Ishibashi S., Kritsiligkou P., Lea R. Amputation-induced reactive oxygen species are required for successful Xenopus tadpole tail regeneration. Nat. Cell Biol. 2013;15:222–228. doi: 10.1038/ncb2659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Niethammer P. The early wound signals. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2016;40:17–22. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2016.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Gauron C., Meda F., Dupont E., Albadri S., Quenech'Du N. Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) controls axon pathfinding during zebrafish development. Dev. Biol. 2016;414:133–141. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2016.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Medrano-Fernandez I., Bestetti S., Bertolotti M., Bienert G.P., Bottino C. Stress regulates aquaporin-8 permeability to impact cell growth and survival. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2016;24:1031–1044. doi: 10.1089/ars.2016.6636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Miller E.W., Dickinson B.C., Chang C.J. Aquaporin-3 mediates hydrogen peroxide uptake to regulate downstream intracellular signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2010;107:15681–15686. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005776107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Hara-Chikuma M., Satooka H., Watanabe S., Honda T., Miyachi Y. Aquaporin-3-mediated hydrogen peroxide transport is required for NF-kappaB signalling in keratinocytes and development of psoriasis. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:7454. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Appenzeller-Herzog C., Banhegyi G., Bogeski I., Davies K.J., Delaunay-Moisan A. Transit of HO across the endoplasmic reticulum membrane is not sluggish. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2016;94:157–160. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2016.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Schwarzländer M., Dick T.P., Meyer A.J., Morgan B. Dissecting redox biology using fluorescent protein sensors. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2016;24:680–712. doi: 10.1089/ars.2015.6266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Bilan D.S., Belousov V.V. HyPer family probes: state of the art. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2016;24:731–751. doi: 10.1089/ars.2015.6586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Rindler P.M., Cacciola A., Kinter M., Szweda L.I. Catalase-dependent H2O2 consumption by cardiac mitochondria and redox-mediated loss in insulin signaling. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2016;311:H1091–H1096. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00066.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Böhm B., Heinzelmann S., Motz M., Bauer G. Extracellular localization of catalase is associated with the transformed state of malignant cells. Biol. Chem. 2015;396:1339–1356. doi: 10.1515/hsz-2014-0234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Matlashov M.E., Belousov V.V., Enikolopov G. How much H2O2 is produced by recombinant D-amino acid oxidase in mammalian cells? Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2014;20:1039–1044. doi: 10.1089/ars.2013.5618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Mishina N.M., Markvicheva K.N., Fradkov A.F., Zagaynova E.V., Schultz C. Imaging H2O2 microdomains in receptor tyrosine kinases signaling. Methods Enzymol. 2013;526:175–187. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-405883-5.00011-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Willems P.H., Rossignol R., Dieteren C.E., Murphy M.P., Koopman W.J. Redox homeostasis and mitochondrial dynamics. Cell Metab. 2015;22:207–218. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Lopez-Fabuel I., Le D.J., Logan A., James A.M., Bonvento G. Complex I assembly into supercomplexes determines differential mitochondrial ROS production in neurons and astrocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2016;113:13063–13068. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1613701113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Brand M.D., Goncalves R.L., Orr A.L., Vargas L., Gerencser A.A. Suppressors of superoxide-H2O2 production at site IQ of mitochondrial complex I protect against stem cell hyperplasia and ischemia-reperfusion injury. Cell Metab. 2016;24:582–592. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Finkel T., Menazza S., Holmström K.M., Parks R.J., Liu J. The ins and outs of mitochondrial calcium. Circ. Res. 2015;116:1810–1819. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.305484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Görlach A., Bertram K., Hudecova S., Krizanova O. Calcium and ROS: a mutual interplay. Redox. Biol. 2015;6:260–271. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2015.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Carafoli E., Krebs J. Why calcium? How calcium became the best communicator. J. Biol. Chem. 2016;291:20849–20857. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R116.735894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Krols M., Bultynck G., Janssens S. ER-Mitochondria contact sites: a new regulator of cellular calcium flux comes into play. J. Cell Biol. 2016;214:367–370. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201607124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Raturi A., Gutierrez T., Ortiz-Sandoval C., Ruangkittisakul A., Herrera-Cruz M.S. TMX1 determines cancer cell metabolism as a thiol-based modulator of ER-mitochondria Ca2+ flux. J. Cell Biol. 2016;214:433–444. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201512077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Bagulho A., Vilas-Boas F., Pena A., Peneda C., Santos F.C. The extracellular matrix modulates H2O2 degradation and redox signaling in endothelial cells. Redox Biol. 2015;6:454–460. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2015.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Feine I., Pinkas I., Salomon Y., Scherz A. Local oxidative stress expansion through endothelial cells--a key role for gap junction intercellular communication. PLoS. One. 2012;7:e41633. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Ghezzi P., Chan P. Redox proteomics applied to the thiol secretome. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2016 doi: 10.1089/ars.2016.6732. (PMID:27139336) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Nathan C., Cunningham-Bussel A. Beyond oxidative stress: an immunologist's guide to reactive oxygen species. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2013;13:349–361. doi: 10.1038/nri3423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Huang B.K., Stein K.T., Sikes H.D. Modulating and measuring intracellular H2O2 using genetically encoded tools to study its toxicity to human cells. ACS Synth. Biol. 2016 doi: 10.1021/acssynbio.6b00120. (PMID:27428287) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]