Significance

In recent years, the κ-opioid receptor (κOR) has become an attractive therapeutic target for the treatment of a number of disorders including depression, visceral pain, and drug addiction. A search for natural products with novel scaffolds targeting κOR has been intensive. Here, we report the discovery of a natural product (Colly) from the fungus Collybia maculata as a novel scaffold that contains a furyl-δ-lactone core structure similar to that of Salvinorin A, another natural product isolated from the mint Salvia divinorum. We show that Colly functions as a κOR agonist with antinociceptive and antipruritic activity. Interestingly, Colly exhibits biased agonistic activity, suggesting that it could be used as a backbone for the generation of novel therapeutics targeting κOR with reduced side effects.

Keywords: G-protein–coupled receptors, natural compounds, salvinorin A, dynorphin, antinociception

Abstract

Among the opioid receptors, the κ-opioid receptor (κOR) has been gaining considerable attention as a potential therapeutic target for the treatment of complex CNS disorders including depression, visceral pain, and cocaine addiction. With an interest in discovering novel ligands targeting κOR, we searched natural products for unusual scaffolds and identified collybolide (Colly), a nonnitrogenous sesquiterpene from the mushroom Collybia maculata. This compound has a furyl-δ-lactone core similar to that of Salvinorin A (Sal A), another natural product from the plant Salvia divinorum. Characterization of the molecular pharmacological properties reveals that Colly, like Sal A, is a highly potent and selective κOR agonist. However, the two compounds differ in certain signaling and behavioral properties. Colly exhibits 10- to 50-fold higher potency in activating the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway compared with Sal A. Taken with the fact that the two compounds are equipotent for inhibiting adenylyl cyclase activity, these results suggest that Colly behaves as a biased agonist of κOR. Behavioral studies also support the biased agonistic activity of Colly in that it exhibits ∼10-fold higher potency in blocking non–histamine-mediated itch compared with Sal A, and this difference is not seen in pain attenuation by these two compounds. These results represent a rare example of functional selectivity by two natural products that act on the same receptor. The biased agonistic activity, along with an easily modifiable structure compared with Sal A, makes Colly an ideal candidate for the development of novel therapeutics targeting κOR with reduced side effects.

Opioid receptors, members of family A of G-protein–coupled receptors (GPCRs), and their ligands have been extensively studied for their involvement in analgesia and sedation (1, 2). Among the different subtypes of opioid receptors, the κ opioid receptor (κOR) displays a repertoire of physiological actions distinct from μ (μOR) and δ (δOR) receptors (3). κOR activation leads to antinociception without the side effects associated with μOR activation such as physical dependence, respiratory depression, or inhibition of gastrointestinal transit (4, 5). In addition, κOR agonists have antipruritic effects and can block the effects of psychostimulants (6–8). Thus, κOR agonists could be potential therapeutics to treat addiction, visceral pain, pruritus, or pain killers with low abuse potential (9–12). However, in vivo κOR activation is associated with side effects like anxiety, stress, diuresis, dysphoria/aversion, and psychomimetic effects (6–8). Also, activation of the κOR system has been implicated in relapse to drugs of abuse; this limits the use of κOR agonists in the treatment of drug addiction (13, 14). Studies correlating the dysphoric effects of κOR agonists to the G-protein–independent activation of the p38 MAPK pathway (8, 13, 15) suggest that identification of κOR agonists biased to G-protein–mediated signaling could lead to the development of therapeutics with reduced side effects. This suggestion has spurred the search for novel κOR ligands or scaffolds that could provide novel treatment strategies for a variety of disorders where κOR involvement has been implicated (16, 17).

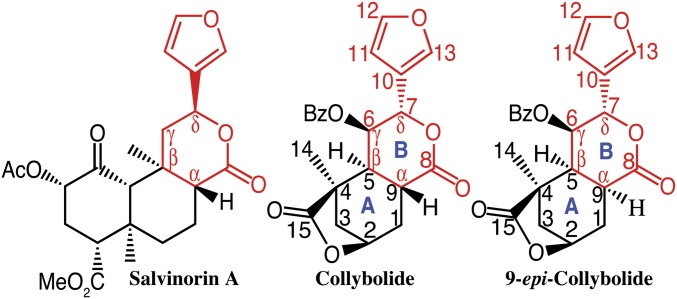

Previously identified synthetic κOR ligands were mostly nitrogenous compounds with a tertiary amine group (16). However, about a decade ago, Salvinorin A (Sal A), a nonnitrogenous diterpene extracted from the Mexican mint Salvia divinorum and characterized by the presence of a furyl-δ-lactone motif (Fig. 1), was identified as a potent and highly selective κOR agonist (18). The structural novelty of Sal A led to extensive structure–activity relationship (SAR) studies through hemisynthetic approaches (19). The furyl-δ-lactone group of Sal A (Fig. 1; motif highlighted in red) is present in other members of the terpene families (20) and appears as a highly oxygenated motif in the diterpene scaffold that is involved in ligand binding to κOR in conjunction with other oxygenated groups (esters) in the molecule.

Fig. 1.

Structures of salvinorin A, collybolide, and 9-epi-collybolide. Chemical structures of the naturally occurring Sal A (from the Mexican mint S. divinorum) and of collybolide and 9-epi-collybolide (from the fungus C. maculata) shown with the common furyl-δ-lactone motif highlighted in red. The absolute configurations of collybolide (2R,4R,5S,6R,7S,9R) and 9-epi-collybolide (2R,4R,5S,6R,7S,9S) were determined by the Bijvoet’s method using the oxygen atoms as anomalous scattering centers (SI Materials and Methods).

In this study, we focused on the sesquiterpene Colly and its diastereoisomer 9-epi-Colly, extracted from the fungus Collybia maculata, because they represent the first examples, to our knowledge, of sesquiterpene structures with the furyl-δ-lactone motif (21). For molecular pharmacological characterization, we used heterologous cells individually expressing the three human opioid receptor types and show that Colly and 9-epi-Colly function as selective and potent κOR agonists. Furthermore, we show that, although Colly and Sal A activate some signal transduction pathways to the same extent and have comparable behavior effects in some assays, they exhibit substantial differences in other pathways and behavioral assays suggesting biased agonism. Finally, taken with our finding that Colly exhibits potent antipruritic activities, these results demonstrate that Collys represent a novel class of κOR-selective agonists that could be used for further explorations of the molecular pharmacology and functioning of this important therapeutic target.

Results

Collybolides Exhibit Structural Similarity to Sal A.

Colly and 9-epi-Colly share the common furyl-δ-lactone motif (i.e., a δ-lactone with its Cδ carbon substituted by the furyl group) present in Sal A (Fig. 1). A bicyclic core with rings A (cyclohexane) and B (δ-lactone) is a common feature of these terpene compounds. Colly has a trans-ring A/B junction, as in Sal A, whereas 9-epi-Colly has a cis junction. Besides the δ-lactone, the central ring A is substituted by an additional ring, a highly oxygenated cyclohexane with two esters and a ketone in Sal A, and a γ-lactone in the Collys. In contrast to Sal A, Collys have a bulky C-6 benzoyl ester in ring B (Fig. 1). In this study, we report the absolute configurations of both sesquiterpenes using single crystal X-ray diffraction analysis in the absence of any chemical transformation (SI Materials and Methods) and establish the epimeric nature of Colly and 9-epi-Colly at the level of C-9 (Fig. 1). Interestingly, the absolute configuration of the asymmetric Cδ carbon (furyl-bearing carbon) in the δ-lactone (Fig. 1) is inverse in Sal A and Collys. The presence of the furyl-δ-lactone motif in Collys, as well as their novel stereochemical features led us to examine whether they could function as κOR selective agonists.

Collybolides Exhibit High Affinity Binding to Human κOR.

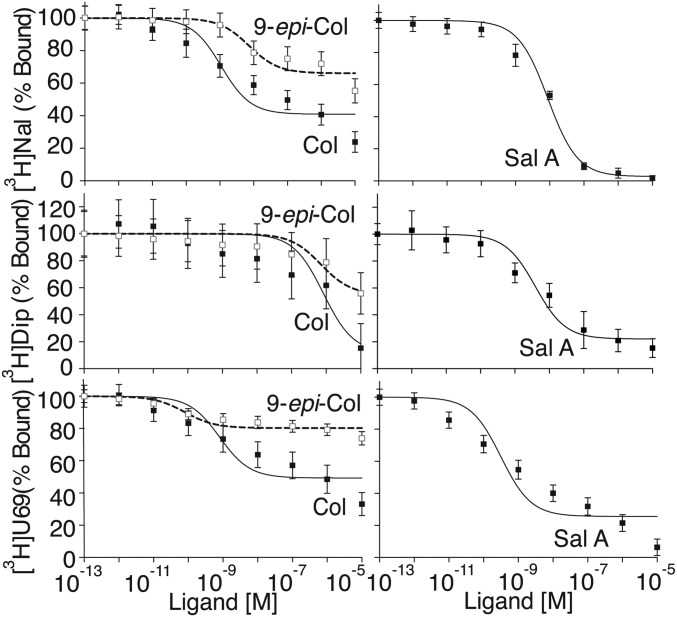

Ligand binding assays using whole cells or membrane preparations expressing human κOR (hκOR) and [3H]Naloxone, a nonselective opioid receptor antagonist, as the radiolabeled ligand show that Colly exhibits a dose-dependent displacement profile with a Ki ∼10−10 M in membrane preparations (Fig. 2 and Table S1) and ∼10−7 M in whole cells (Fig. S1). Sal A, the synthetic κOR agonist U69,593, and the peptidic κOR agonist dynorphin A8 (Dyn A8) displace [3H]Naloxone binding with affinities in the nanomolar range (Ki ∼ 1–7 × 10−9 M) in membrane preparations (Table S1), and 10−8–10−9 M in whole cells (Table S2). Interestingly, epimerization at position 9 (9-epi-Colly) decreases the ability of the compound to displace [3H]Naloxone binding to hκOR (Fig. 2, Table S1, and Fig. S1). The displacement profile of receptor-bound [3H]Naloxone by Colly and 9-epi-Colly is not probe specific or dependent on the assay buffer conditions used, because a similar profile is seen with [3H]Diprenorphine or [3H]U69,593 or when using different assay buffer conditions (Fig. 2, Table S1, and Fig. S1). Together these results indicate that Collys bind to hκOR.

Fig. 2.

Displacement of radiolabeled ligand binding to human κOR. Membranes (200 μg) from HEK-293 cells expressing hκOR were incubated with [3H]Naloxone (Nal), [3H]Diprenorphine (Dip), or [3H]U69,493 (U69) (3 nM) in 50 mM Tris⋅Cl, pH 7.8, containing 1 mM EGTA, 5 mM MgCl2, and protease inhibitor mixture in the absence or presence of Colly (Col), 9-epi-Colly (9-epi-Col), or Sal A (10−13–10−5 M). Values at 10−13 M cold ligand were taken as 100%. Data represent mean ± SEM; n = 6.

Table S1.

Displacement binding by collybolides in membranes expressing hκOR

| Ligands | [3H]Naloxone | [3H]Diprenorphine | [3H]U69,593 | |||

| Ki [M] | % bound* | Ki [M] | % bound* | Ki [M] | % bound* | |

| Collybolide | 9 ± 2 E−10 | 24 ± 6 | 4 ± 2 E−7 | 15 ± 18 | 7 ± 2 E−10 | 33 ± 7 |

| 9-epi-Collybolide | 6 ± 2 E−9 | 55 ± 7 | 3 ± 2 E−7 | 56 ± 15 | 7 ± 2 E−11 | 74 ± 4 |

| Sal A | 7 ± 3 E−9 | 1 ± 2 | 2 ± 0.2 E−9 | 15 ± 7 | 3 ± 0.3 E−10 | 6 ± 5 |

| U69,593 | 1 ± 0.3 E−9 | 8 ± 5 | 3 ± 1 E−10 | 1 ± 4 | 2 ± 0.5 E−10 | 6 ± 2 |

| DynA8 | 1 ± 0.2 E−9 | 12 ± 5 | 6 ± 0.3 E−10 | 1 ± 3 | 2 ± 0.5 E−10 | 10 ± 2 |

| Diprenorphine | ND | ND | 3 ± 2 E−9 | 18 ± 2 | ND | ND |

| Naloxone | 1 ± 0.2 E−9 | 1 ± 1 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

Membranes were incubated with [3H]Naloxone, [3H]Diprenorphine, or [3H]U69,593 (3 nM) in 50 mM Tris⋅Cl buffer, pH 7.8, containing 1 mM EGTA, 5 mM MgCl2, and protease inhibitor mixture in the presence of κOR ligands (10−13–10−5 M). Values obtained at 10−13 M were taken as 100%. Data represent mean ± SEM; n = 6. ND, not done.

Percentage counts bound in the presence of 10 μM cold ligand.

Fig. S1.

Displacement of radiolabeled ligand binding to human κOR. (A) HEK-293 cells (2 × 105) expressing human κOR were incubated with [3H]Naloxone, [3H]Diprenorphine, or [3H]U69,493 (3 nM) in 50 mM Tris⋅Cl buffer, pH 7.8, containing 1 mM EGTA, 5 mM MgCl2, and protease inhibitor mixture in presence of either collybolide (Col), 9-epi-collybolide (9-epi-Col), or Sal A (Sal) (10−13–10−5 M). (B–D) Membranes (200 μg) from HEK-293 cells expressing hκOR were incubated with [3H]Naloxone (3 nM) in 50 mM Tris⋅Cl buffer, pH 7.8, containing protease inhibitor mixture (B), 50 mM Tris⋅Cl, pH 7.4, containing 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM EGTA, and protease inhibitor mixture (C), or 50 mM Tris⋅Cl buffer, pH 7.8, containing 1 mM EGTA, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 μM GTPγS, and protease inhibitor mixture (D) in the presence of collybolide (10−13–10−5 M). Values obtained at 10−13 M ligand were taken as 100%. Data represent mean ± SEM; n = 6.

Table S2.

Displacement of radiolabeled binding by collybolides in cells expressing hκOR

| Ligands | [3H]Naloxone | [3H]Diprenorphine | [3H]U69,593 | |||

| Ki [M] | % bound* | Ki [M] | % bound* | Ki [M] | % bound* | |

| Collybolide | 1 ± 0.2 E−7 | 34 ± 3 | 6 ± 1 E−9 | 35 ± 2 | 9 ± 2 E−9 | 24 ± 7 |

| 9-epi-Collybolide | 2 ± 1 E−9 | 76 ± 1 | 7 ± 2 E−9 | 75 ± 2 | 4 ± 2 E−11 | 63 ± 5 |

| Sal A | 4 ± 1 E−9 | 1 ± 1 | 7 ± 1 E−9 | 1 ± 3 | 4 ± 1 E−8 | 4 ± 1 |

| U69,593 | ND | ND | 8 ± 3 E−9 | 18 ± 1 | 6 ± 1 E−9 | 14 ± 5 |

| Dyn A8 | 1 ± 0.2 E−8 | 14 ± 5 | 8 ± 2 E−9 | 14 ± 6 | 4 ± 1 E−9 | 37 ± 4 |

| Diprenorphine | ND | ND | 2 ± 1 E−9 | 9 ± 3 | ND | ND |

| Naloxone | 5 ± 2 E−9 | 2 ± 1 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

HEK-293 cells (2 × 105) expressing human κOR were incubated with [3H]Naloxone, [3H]Diprenorphine, or [3H]U69,593 (3 nM) in 50 mM Tris⋅Cl buffer, pH 7.8, containing 1 mM EGTA, 5 mM MgCl2, and protease inhibitor mixture in the presence of either Collybolide, 9-epi-Collybolide, Sal A, U69,593, DynA8, diprenorphine, or naloxone (10−13–10−5 M). Values obtained at 10−13 M ligand concentration were taken as 100%. Data represent mean ± SEM; n = 6. ND, not done.

Percentage counts bound in the presence of 10 μM cold ligand.

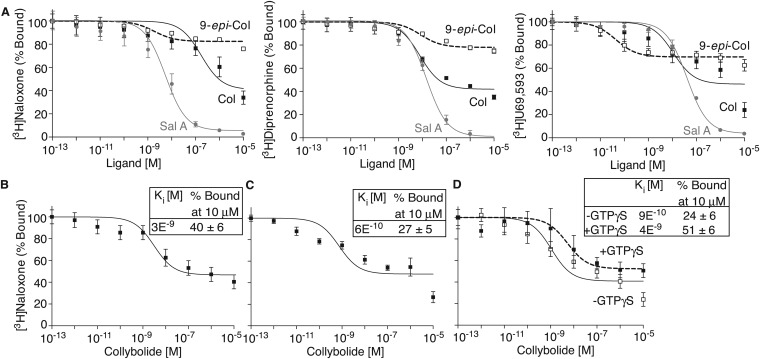

Collybolides Exhibit Selectivity to hκOR.

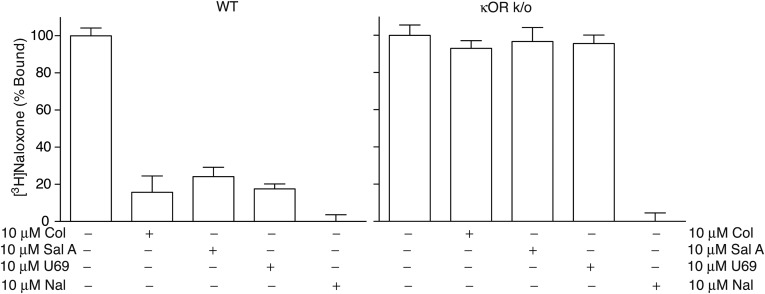

We examined the selectivity of Collys for hκOR by comparing their ability to displace [3H]Naloxone binding to hμOR or hδOR and to signal through these receptors. We find that neither Colly nor 9-epi-Colly displace [3H]Naloxone binding to hμOR or hδOR (Fig. 3). Also, Collys do not elicit changes in [35S]GTPγS binding or ERK1/2 phosphorylation in cells expressing hμOR or hδOR (Fig. S2) nor do they block DAMGO (μOR agonist) or deltorphin II (δOR)-mediated increases in phospho ERK1/2 (Fig. S2). These results indicate that Collys exhibit selectivity toward hκOR. This selectivity is supported by the ability of Colly to displace [3H]Naloxone binding to membranes from WT mice but not from mice lacking κOR (Fig. 3 and Fig. S3).

Fig. 3.

Collybolides bind to human κOR but not μOR or δOR. Membranes (200 μg) from HEK-293 cells expressing hκOR, hδOR, or hμOR were incubated with [3H]Naloxone (3 nM) in 50 mM Tris⋅Cl, pH 7.8, containing 1 mM EGTA, 5 mM MgCl2, and protease inhibitor mixture in the presence of collybolide (A) or 9-epi-collybolide (B) (10−13–10−5 M). Data represent mean ± SEM; n = 6. (C) Cerebral cortex membranes (100 μg) from WT or κOR KO mice (κOR k/o) were incubated with [3H]Naloxone (3 nM) in the presence of collybolide (10−13–10−5 M). Data represent mean ± SEM; n = 3 individual animals. Values at 10−13 M cold ligand were taken as 100%. n.d., not detected.

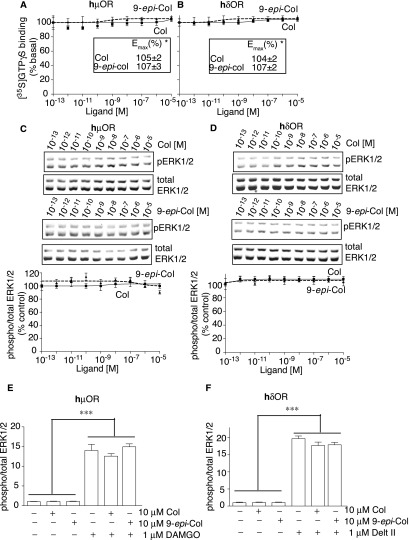

Fig. S2.

Signaling properties of collybolides at human μOR or δOR. (A and B) Membranes (20 μg) from HEK-293 cells expressing hμOR (A) or hδOR (B) were subjected to a [35S]GTPγS binding assay in the presence of either Colly (Col) or 9-epi-Colly (9-epi-Col) (10−13–10−5 M). * represents values obtained at 10−5 M. (C and D) HEK-293 cells expressing hμOR (C) or hδOR (D) were treated for 3 min at 37 °C with either Col or 9-epi-Col (10−13–10−5 M) and phosphorylated ERK1/2 levels measured as described in Materials and Methods. Values (A–D) obtained at 10−13 M ligand were taken as 100%. (E and F) HEK-293 cells expressing hμOR (E) or hδOR (F) were treated for 3 min at 37 °C with either 1 μM DAMGO ± 10 μM Col or 9-epi-Col (E) or 1 μM deltorphin II (Delt II) ± 10 μM Col or 9-epi-Col (F) and phosphorylated ERK1/2 levels measured as described in Materials and Methods. Data represent mean ± SEM; n = 3.

Fig. S3.

Selectivity of collybolide for κOR. Membranes from the brain of WT and from κOR KO mice were treated with [3H]Naloxone (3 nM) in the absence or presence of 10 μM of either collybolide (Col), Sal A, U69,593 (U69), or naloxone (Nal). Data represent mean ± SEM; n = 3.

Collybolide Is a High Affinity Agonist of hκOR.

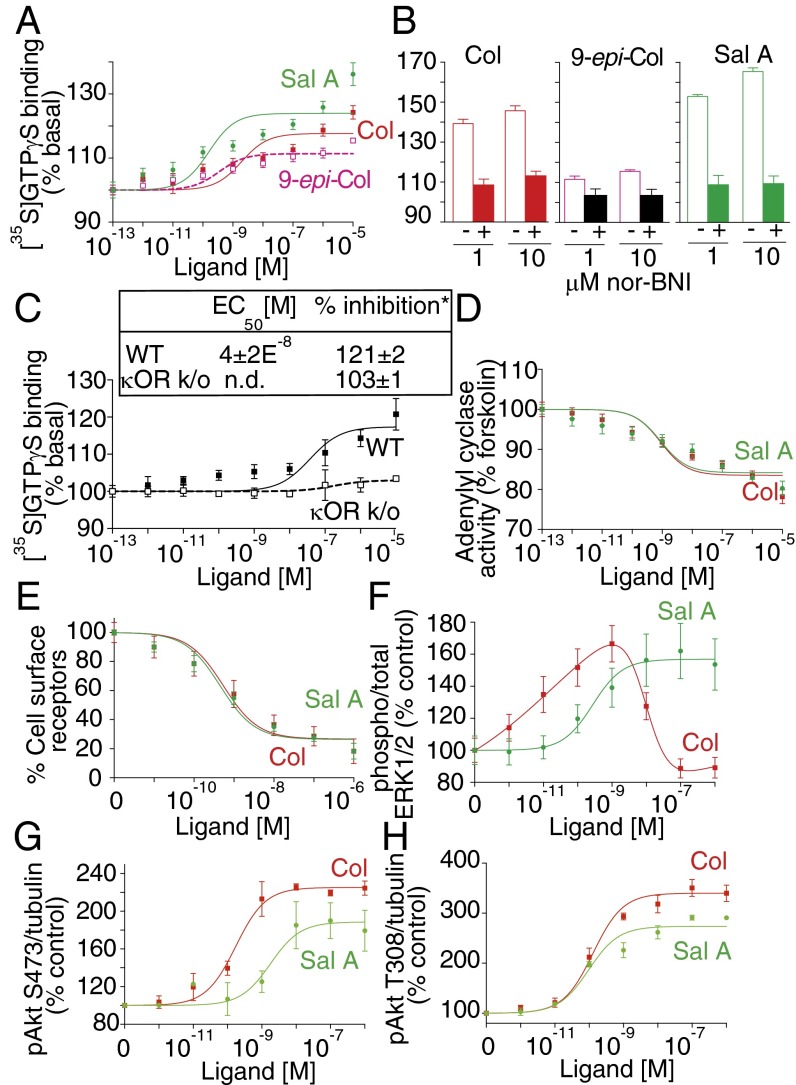

Next we examined signaling by Colly using [35S]GTPγS binding assays. Colly dose-dependently increases [35S]GTPγS binding with an EC50 of ∼10−9 M (Fig. 4A), a potency similar to that of 9-epi-Colly, Sal A, U69,593, and Dyn A8 (Fig. 4A and Table 1). Interestingly, 9-epi-Colly exhibits substantial lower efficacy suggesting partial agonism (Fig. 4A). The increase in [35S]GTPγS binding mediated by both Collys is blocked by a κOR antagonist, nor-BNI (Fig. 4B). Moreover, Colly dose-dependently increases [35S]GTPγS binding to WT but not κOR KO membranes (Fig. 4C), supporting Collys as κOR selective agonists.

Fig. 4.

Signaling by collybolides in membranes expressing hκOR. Membranes (20 μg) from HEK-293 cells expressing hκOR were subjected to a [35S]GTPγS binding assay in the presence of Colly (Col), 9-epi-Colly (9-epi-Col), or Sal A (10−13–10−5 M) (A) without or with preincubation (30 min) with nor-BNI (B). (C) [35S]GTPγS binding using cerebral cortex membranes from WT and κOR KO mice and Col (10−13–10−5 M). (D) Membranes (2 μg) from HEK-293 cells expressing hκOR were treated with Col or Sal A (10−13–10−5 M), and cAMP levels were measured. Values (A–D) at 10−13 M ligand were taken as 100%. (E) Receptor internalization in HEK-293 cells expressing hκOR treated with Col or Sal A (0–1 μM) for 30 min at 37 °C; percent internalized receptors were calculated as described in SI Materials and Methods. (F–H) HEK-293 cells expressing hκOR were treated for 3 min at 37 °C with either Col or Sal A (10−13–10−6 M) and phosphorylated levels of ERK1/2 (F), Akt at S473 (G), or Akt at T308 (H) measured. Data (A–H) represent mean ± SEM; n = 3–6. *Values obtained with 10 μM ligand. n.d., not detected.

Table 1.

Signaling with collybolides

| Ligands | [35S]GTPγS binding | AC activity | phospho ERK1/2 | phospho Akt S473 | phospho Akt T308 | Internalization | ||||||

| EC50 [M] | % Emax* | EC50 [M] | % Inhibition* | EC50 [M] | % Emax | EC50 [M] | % Emax | EC50 [M] | % Emax | EC50 [M] | % Emax* | |

| Colly | 2 ± 1 E−9 | 124 ± 2 | 9 ± 2 E−10 | 22 ± 2 | 9 ± 2 E−12 | 167 ± 11† | 2 ± 1 E−10 | 225 ± 8 | 1 ± 1 E−10 | 350 ± 9‡ | 5 ± 1 E−10 | 18 ± 8 |

| 9-epi-Colly | 3 ± 2 E−10 | 115 ± 1 | 4 ± 2 E−6 | 10 ± 3 | 4 ± 1 E−9 | 141 ± 7* | 4 ± 2 E−10 | 160 ± 17 | 6 ± 2 E−11 | 190 ± 31 | 8 ± 3 E−11 | 79 ± 10 |

| Sal A | 2 ± 1 E−10 | 136 ± 4 | 9 ± 1E−10 | 20 ± 2 | 3 ± 1 E−10 | 162 ± 17‡ | 3 ± 2 E−9 | 190 ± 19‡ | 1 ± 1 E−10 | 291 ± 3‡ | 5 ± 2 E−10 | 18 ± 5 |

| U69,593 | 6 ± 2 E−8 | 132 ± 1 | 2 ± 1 E−9 | 30 ± 2 | 2 ± 1 E−10 | 274 ± 39‡ | 2 ± 1 E−10 | 156 ± 9 | 3 ± 2 E−10 | 271 ± 8 | 2 ± 1 E−9 | 15 ± 5 |

| DynA8 | 2 ± 1 E−10 | 133 ± 3 | 2 ± 1 E−9 | 16 ± 1 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 1 ± 1 E−9 | 26 ± 5 |

HEK-293 membranes expressing hκOR were subjected to a [35S]GTPγS binding assay (20 μg) or to an adenylyl cyclase (AC) activity assay (2 μg) with κOR ligands (10−13–10−5 M). HEK-293 cells expressing hκOR (2 × 105 cells per well) were treated with κOR ligands, phosphorylation of ERK1/2, Akt S473, or T308 measured after 3 min or receptor internalized after 30 min. Values obtained at 10−13 M ligand were taken as 100%. Data are mean ± SEM; n = 6. ND, not done.

Values obtained with 10 μM ligand concentration.

Values obtained with 1 nM ligand concentration.

Values obtained with 100 nM ligand concentration.

Because κOR activation leads to inhibition of adenylyl cyclase activity and consequently decreases in cAMP levels (22), we examined effects of Colly on adenylyl cyclase activity. We find that Colly dose-dependently decreases adenylyl cyclase activity with a nanomolar potency comparable to that of Sal A (Fig. 4D and Table 1) but markedly lower than that of 9-epi-Colly that exhibits a potency in the micromolar range (Table 1). Together these results indicate that Collys exhibit agonistic activity at hκOR.

Collybolide Induces Robust Endocytosis of hκOR.

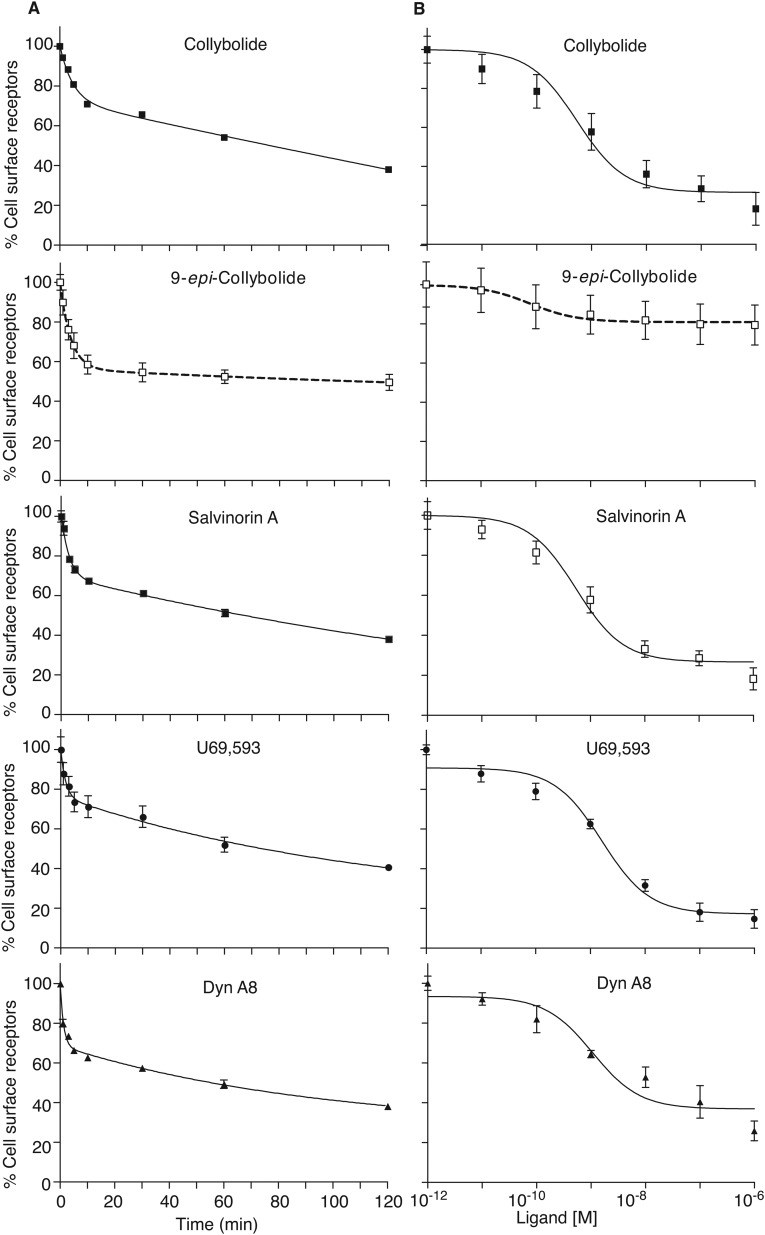

Because treatment with agonists can induce rapid and robust internalization of hκOR (23), we examined the ability of Colly to induce κOR endocytosis. A time course analysis reveals rapid and robust endocytosis (Fig. S4), and the dose–response analysis reveals an EC50 for Colly ∼5 × 10−10 M that is comparable to that of Sal A and much greater than that of 9-epi-Colly (Fig. 4E and Table 1). These results show that Colly, like other high potency hκOR agonists, induces rapid and robust receptor internalization.

Fig. S4.

Trafficking properties of human κOR. HEK-293 cells expressing hκOR were incubated at 4 °C for 1 h with 1:1,000 anti-HA antibody in media to label cell surface κOR, washed three times to remove unbound antibody, and then treated without or with 100 nM κOR ligands for different time intervals (0–120 min) (A) or with different concentrations (0–1 μM) of κOR ligands for 30 min (B) at 37 °C. Receptors present at the cell surface were determined as described in Materials and Methods. The percent internalized receptors was calculated by taking total cell surface receptors before agonist treatment for each individual experiment as 100% and subtracting percent surface receptors following agonist treatment. Data represent mean ± SEM; n = 6.

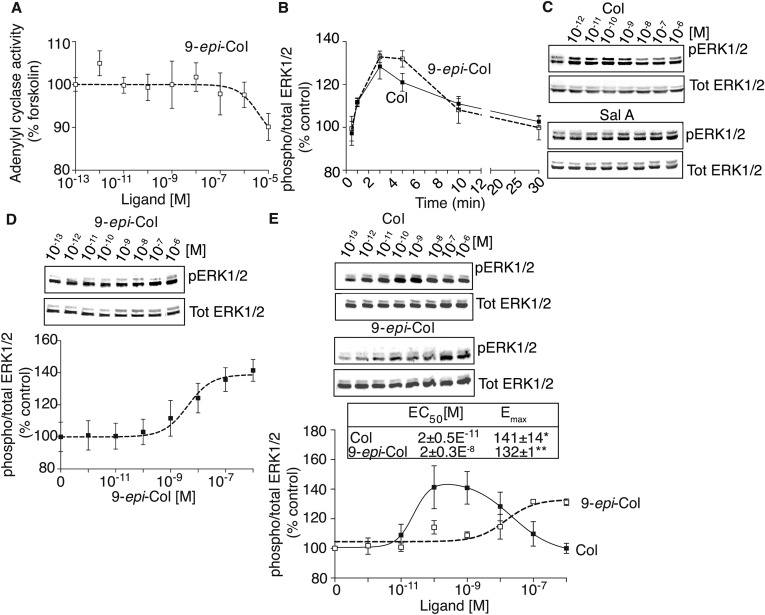

Collybolide Exhibits Biased Agonism at hκOR.

Next, we examined the ability of Collys to induce ERK1/2 phosphorylation. We find that Collys exhibit peak ERK1/2 phosphorylation at ∼3–5 min (Fig. S5). Interestingly, Colly exhibits an inverted “U-shape” profile with maximal stimulation at ∼10−9 M; at higher concentrations, Colly-mediated signaling is rapidly desensitizing both in HEK or CHO cells expressing hκOR (Fig. 4F and Fig. S5). In contrast, Sal A (like 9-epi-Colly and U69,593) exhibits a sigmoidal dose–response curve with maximal ERK1/2 phosphorylation at ∼10−7–10−6 M (Fig. 4F and Table 1). To ascertain whether the inverted U-shaped profile for ERK1/2 phosphorylation by Colly is also seen with other signaling pathways, we examined the profile for phosphorylation of Akt at S473 and at T308. We find that Colly exhibits a sigmoidal dose (and not an inverted U-shaped) response curve for Akt both at S473 and T308 (Fig. 4 G and H). Interestingly, Colly appears to be more efficacious than Sal A at phosphorylating Akt at both sites (Table 1). These observations suggest that Colly exhibits differences in signaling from Sal A at hκOR.

Fig. S5.

Signaling properties of collybolides. (A) Membranes (2 μg) from HEK-293 cells expressing hκOR were treated with 9-epi-Col (10−13–10−5 M) and cAMP levels measured as described in Materials and Methods. Values obtained at 10−13 M ligand were taken as 100%. (B) HEK-293 cells expressing hκOR were treated for different time intervals (30 s to 30 min) at 37 °C with vehicle, Col, or 9-epi-Col (100 nM) and phosphorylated ERK1/2 levels measured as described in Materials and Methods. (C) Representative Western blots for Col and Sal A data presented in Fig. 4F. (D) HEK-293 cells expressing hκOR were treated for 3 min at 37 °C with 9-epi-Col (10−13–10−6 M) and phosphorylated ERK1/2 levels measured as described in Materials and Methods. Representative blot is shown. (E) CHO cells expressing hκOR were treated for 3 min at 37 °C with either Col or 9-epi-Col (10−13–10−6 M) and phosphorylated ERK1/2 levels measured as described in Materials and Methods. Data (A–E) represent mean ± SEM; n = 3–6.

Collybolide Exhibits κOR Agonist Activity in Mice.

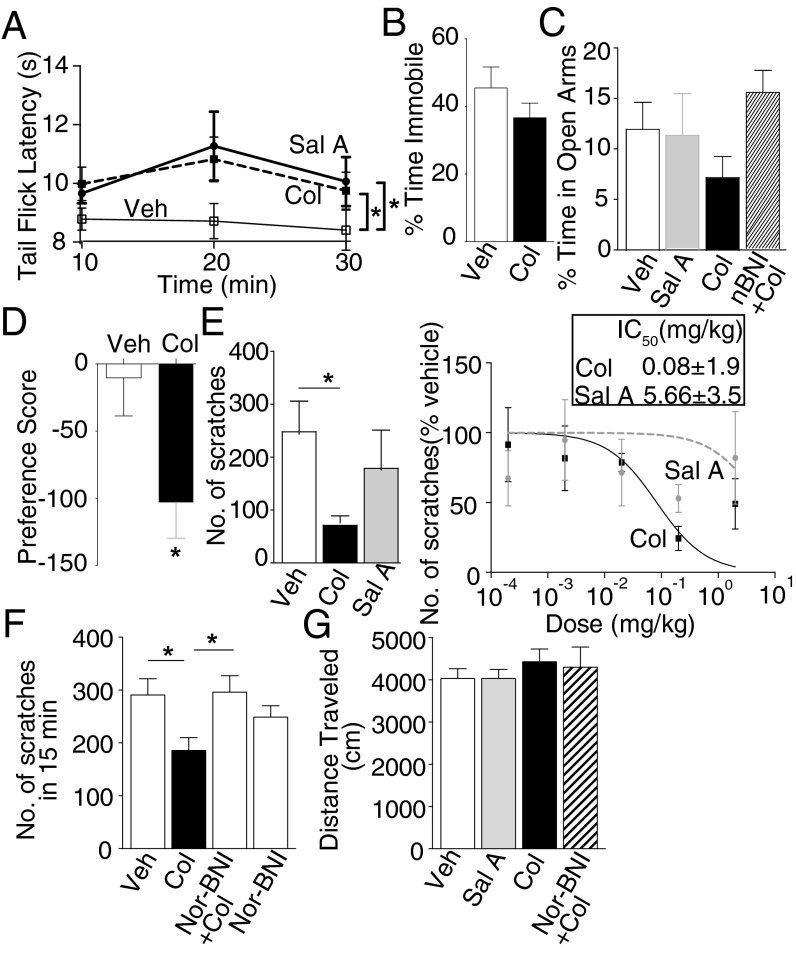

Next, we focused on Colly and evaluated its behavioral effects in mice. We find that the antinociceptive activity of Colly is similar to that of Sal A with peak activity at 20 min following drug administration (Fig. 5A). We did not find significant differences between Colly and vehicle-treated controls in the forced swim test, although Colly-treated mice tended to spend less time being immobile (Fig. 5B). In the elevated plus maze test, Colly and Sal A did not exhibit significant differences, although Colly-treated animals showed a higher tendency to spend less time in the open arms (i.e., tend to exhibit a higher level of anxiety), and this was blocked in animals treated with nor-BNI (Fig. 5C). The effect of Colly in the conditioned place preference/aversion assay shows that single daily injections for 4 d leads to significant (*P < 0.05) conditioned place aversion (Fig. 5D); this has been shown for κOR agonists including Sal A (3, 24). In contrast to these assays where Colly behaves in a manner similar to Sal A, Colly differs remarkably from Sal A when examined for its ability to block pruritus (non–histamine-mediated itch). Colly (2 mg/kg) significantly attenuates chloroquine-mediated scratching behavior; this is not seen with the same dose of Sal A (Fig. 5E). In addition, Colly exhibits dose-dependent inhibition of pruritus with a high potency (IC50 = 0.08 mg/kg), and this effect is desensitized at higher doses (Fig. 5E). Also, Colly-mediated attenuation of pruritus can be reversed by the κOR antagonist nor-BNI (Fig. 5F). We also find that Colly treatment has no effect on animal movement in an open field test (Fig. 5G). These results indicate that Colly is a novel, high-potency hκOR agonist with behavioral properties distinct from that of Sal A that taken with its biased agonistic activity makes it an attractive candidate for further studies exploring the molecular pharmacology of κOR.

Fig. 5.

Behavioral effects of collybolide. (A) Mice were administered with vehicle (Veh), Sal A (Sal), or Colly (Col) (2 mg/kg), and antinociception was measured at different time intervals using the tail flick assay. Two-way ANOVA: time, F(2,42) = 1.486, P = 0.238; drug, F(2,21) = 4.199, P = 0.029; Bonferroni post hoc: *P < 0.05 vehicle vs. Sal A/Col. (B) Forced swim test with mice administered with Veh or Col (2 mg/kg). (C) Mice administered with Veh, Sal, Col (2 mg/kg), or nor-BNI (10 mg/kg) + Col were placed in the elevated plus maze, and time spent in the open arms was measured. (D) Mice were administered with Veh or Col (2 mg/kg) for 4 d, and place preference was measured. t test: *P < 0.05. (E) Mice were administered with chloroquine-phosphate (20 mg/kg) in the absence or presence of Sal or Col (2–2,000 μg/kg), and number of scratches was measured for 15 min. Veh vs. Col 2,000 μg/kg, unpaired t test: *P < 0.05. (F) Assessment of the effect of nor-BNI (10 mg/kg) on Col-mediated attenuation of itch. *P < 0.05; one-way ANOVA. (G) Mice were injected i.p. with Veh, Col (2 mg/kg), Sal A (2 mg/kg), or nor-BNI (10 mg/kg) + Col (2 mg/kg) 20 min before subjecting them to the open field test. Data (A–G) represent mean ± SEM; n = 7–10 mice per group.

SI Materials and Methods

Natural Compounds, Materials, and Analytical Data.

Sal A was obtained from In Solve Scientific; the analytical report (HPLC, MS, UV, and 1H NMR) with 95.9% purity (HPLC) was in agreement with the reported data for C23H28O8, i.e., 432.47 g/mol (40): (i) ESI(+) MS: m/z = 455.25 (exptl) for 455.17 (theor) C23H28O8Na+; (ii) UV absorption at 210 nm (max) for furan; (iii) a comparison of the 1H NMR spectrum (400 MHz; CDCl3; TMS internal reference) with the graphical 1H NMR spectrum (800 MHz, CDCl3) of Sal A (with revised assignments) in the PhD thesis of Munro (41) was carried out in full conformity with: 1.11 ppm (s,3H): CH3-19; 1.45 ppm (s, 3H): CH3-20; 2.16 ppm (s, 3H): CH3-22; 3.72 ppm (s, 3H): CH3-23; 5.14 ppm (1H): C2-H; 5.52 ppm (1H): C12-H; 6.37 ppm (1H): furyl-H14; ∼7.4 ppm (2H): furyl-H15+H16. The two sesquiterpenes of fungal origin extracted from C. maculata (for a review on the phylogeny of C. maculata, see ref. 42), collybolide and 9-epi-collybolide, were part of the collection of two of the coauthors (A.C. and J.P.) after their discovery (21). The structures of collybolide and 9-epi-collybolide were reassessed by X-ray crystallography using monocrystals of collybolide and 9-epi-collybolide. Absolute configurations were determined using the Hooft method, which uses the Bijvoet-pair intensities measured in reciprocal space from anomalous dispersion of the atoms collected (43–45). 1H and 13C NMR spectra for both the natural compounds were found to be in agreement as reported in the literature (21, 46); 10 mM stock solutions of Sal A, collybolide, and 9-epi-collybolide in DMSO were used for all pharmacological assays. U69,593 (34), the arylacetamide κOR agonist [(5α,7α,8β)-(+)-N-methyl-N-[7-(1-pyrrolidinyl)-1-oxaspiro[4,5]dec-8-yl]benzenacetamide], Dyn A8, H-Tyr-Gly-Gly-Phe-Leu-Arg-Arg-Ile-OH, and protease inhibitor mixture were obtained from Sigma. The radioligands, [3H]Diprenorphine, [3H]Naloxone, and [3H]U69,593, with specific radioactivities of 42.3, 61.1, and 37.4 Ci/mmol, respectively, and [35S]GTPγS with a specific radioactivity of 1,250 Ci/mmol were from Perkin-Elmer. κOR KO mice brains were a gift from Charles Chavkin (University of Washington, Seattle).

Cell Culture.

HEK-293 cells were grown in DMEM containing 10% (vol/vol) FBS and penicillin-streptomycin. CHO cells were grown in F12 media containing 10% FBS and penicillin-streptomycin. Cells were transfected with human μOR (hμOR), δOR (hδOR), or hκOR cDNAs using lipofectamine as per manufacturer’s protocol (Invitrogen). Forty-eight hours after transfection cells were used to prepare membranes for receptor binding and signaling assays as described below. Saturation binding assays using [3H]Naloxone (0–10 nM) in 50 mM Tris⋅Cl buffer, pH 7.8, containing 1 mM EGTA, 5 mM MgCl2, and protease inhibitor mixture in the absence or presence of 10 μM U69,593, deltorphin II, or DAMGO show that the cells express similar amounts of hμOR, hδOR, or hκOR (874 ± 240 fmol/mg protein for hμOR, 837 ± 171 for hδOR, and 816 ± 253 for hκOR).

Membrane Preparation.

Membranes were prepared from HEK-293 cells expressing either hκOR, hδOR, hμOR, or from cerebral cortex or whole brains of WT or κOR KO mice as described previously (35).

Receptor Displacement Binding Assays.

Assays were carried out in glass tubes treated with 0.1% (vol/vol) aquaSil-siliconizing fluid in double distilled water (DDW) for 10 min. Tubes were rinsed once in DDW and air dried. Competition binding assays were carried out as described previously (35, 36). Briefly, membranes (200 μg) from HEK cells expressing either hμOR, hδOR, or hκOR (200 μg/tube) were incubated with [3H]Diprenorphine, [3H]Naloxone, or [3H]U69,593 (3 nM final concentration) in the presence of different concentrations (10−13–10−5 M) of κOR ligands for 2 h at 30 °C in a buffer comprising of 50 mM Tris⋅Cl buffer, pH 7.8, containing 1 mM EGTA, 5 mM MgCl2, and protease inhibitor mixture. Other buffers used in binding assays included (i) 50 mM Tris⋅Cl buffer, pH 7.8, containing protease inhibitor mixture; (ii) 50 mM Tris⋅Cl, pH 7.4, containing 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM EGTA, and protease inhibitor mixture; and (iii) 50 mM Tris⋅Cl buffer, pH 7.8, containing 1 mM EGTA, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 μM GTPγS, and protease inhibitor mixture. Nonspecific binding was determined using [3H]Naloxone (3 nM final concentration) and 10 μM cold naloxone. Bound radioactivity was collected by filtration under reduced pressure using GF/B filters presoaked in 50 mM Tris⋅Cl, pH 7.4, containing 0.1 mg/mL BSA and 0.2% (wt/vol) polyethylenimine. Values obtained with 10−13 M cold ligand were taken as 100%.

In a separate set of experiments, cerebral cortex membranes or whole brain membranes (100 μg) from WT or κOR KO mice were incubated with [3H]Naloxone (3 nM) and specific bound counts determined in the presence of 10 μM of either collybolide, Sal A, U69,593, or naloxone as described above.

[35S]GTPγS Binding Assays.

Assays were carried out in glass tubes treated as described above for receptor binding assays. Membranes (20 μg) from HEK-293 cells expressing hκOR, hμOR, or hδOR were subjected to a [35S]GTPγS binding assay in 50 mM Tris⋅Cl buffer, pH 7.8, containing 1 mM EGTA, 5 mM MgCl2, and protease inhibitor mixture in the absence or presence of either collybolide, 9-epi-collybolide, Sal A, U69,593, or Dyn A8 (10−13–10−5 M) as described previously (35, 36). Nonspecific binding was determined in the presence of 10 μM cold GTPγS. Values obtained with 10−13 M ligand were taken as 100%. In a separate set of experiments, membranes were preincubated with nor-BNI (10 μM) for 30 min before carrying out [35S]GTPγS binding as described above. In another set of experiments, membranes (20 μg) from the cerebral cortex of WT mice or from κOR KO mice were subjected to a [35S]GTPγS binding assay with collybolide (10−13–10−5 M) as described above.

Measurement of Adenylyl Cyclase Activity.

Membranes from HEK-293 cells expressing hκOR (2 μg/well) were incubated with either collybolide, 9-epi-collybolide, Sal A, U69,593, or Dyn A8 (10−13–10−5 M) for 30 min at 37 °C in 50 mM Hepes buffer, pH 7.4, containing 20 μM forskolin, 10 mM MgCl2, 100 mM NaCl, 200 μM ATP, 10 μM GTP, and 100 μM IBMX. cAMP levels were determined using the HitHunter cAMP MEM chemiluminescence detection kit from DiscoveRx. Values obtained at 10−13 M ligand were taken as 100%.

Measurement of ERK1/2 Phosphorylation.

CHO or HEK-293 cells expressing hκOR (2 × 105 cells per well) were seeded into a 24-well polylysine-coated plate. Cells were grown for 16 h in growth media without FBS. Cells were treated with either vehicle, collybolide, 9-epi-collybolide, Sal A, or U69,593 (10−13–10−6 M) for 3 min at 37 °C. For time course studies, cells were treated with either vehicle, collybolide, or 9-epi-collybolide (100 nM) for different time periods (30 s to 30 min). ERK1/2 phosphorylation was measured as described (36, 37) using antibodies to phospho ERK1/2 (1:1,000; cat. no. 4370S; Cell Signaling Technology) and to total ERK1/2 (1:1,000; cat. no. 4696S; Cell Signaling Technology) as primary antibodies. Anti-rabbit IRDye 800 (1:10,000; cat. no. 926-32211; Li-Cor) and anti-mouse IRDye 680 (1:10,000; cat. no. 926-68070; Li-Cor) were used as secondary antibodies.

In a separate set of experiments, hμOR or hδOR cells were treated with collybolide, 9-epi-collybolide (10−13–10−6 M), with 1 μM DAMGO ± 10 μM collybolide/9-epi-collybolide or with 1 μM deltorphin II ± 10 μM collybolide/9-epi-collybolide as described above.

Measurement of Akt Phosphorylation.

CHO or HEK-293 cells expressing hκOR (2 × 105 cells per well) were seeded into a 24-well polylysine-coated plate. Cells were grown for 16 h in growth media without FBS. Cells were treated with either vehicle, collybolide, 9-epi-collybolide, Sal A, or U69,593 (10−13–10−6 M) for 3 min at 37 °C. Akt phosphorylation at S473 or T308 was measured by Western blotting as described (36, 37) using rabbit anti-phospho Akt S473 (1:1,000; cat no. 4060S; Cell Signaling Technology), rabbit anti-phospho Akt T308 (1:1,000; cat no. 2965S; Cell Signaling Technology), and mouse anti-tubulin antibodies (1:50,000; cat. no. T5168; Sigma-Aldrich) as primary antibodies. Anti-rabbit IRDye 800 (1:10,000; cat. no. 926–32211; Li-Cor) and anti-mouse IRDye 680 (1:10,000; cat. no. 926-68070; Li-Cor) were used as secondary antibodies.

Receptor Internalization.

HEK-293 cells expressing hκOR (2 × 105 cells per well) were seeded into a 24-well polylysine-coated plate. The following day, the plate was kept on ice, and cells were incubated at 4 °C for 1 h with 1:1,000 anti-HA antibody in media to label cell surface κOR. Cells were washed three times and then treated without or with 100 nM collybolide, Sal A, U69,593, and Dyn A8 for different time intervals (0–120 min) at 37 °C to facilitate receptor internalization. At the end of the incubation period, cells were briefly fixed (3 min) with 4% (wt/vol) paraformaldehyde followed by three washes (5 min each) with PBS. Receptors present at the cell surface were determined using 1:1,000 dilution (in PBS containing 1% BSA) of anti-rabbit IgG coupled to HRP (Vector Laboratories) as described previously (47, 48). The percent internalized receptors was calculated by taking total cell surface receptors before agonist treatment for each individual experiment as 100% and subtracting percent surface receptors following agonist treatment. In a separate set of experiments, the effects of different doses (0–1 μM) of agonists for 30 min on hκOR-mediated internalization was examined.

Animal Studies.

Male C57BL/6J mice, 10–12 wk of age (Jackson Laboratories), were used in these studies. Mice were housed in groups of three to five mice per cage in a humidity- and temperature-controlled room with a 12-h light/dark cycle (lights on: 07:00–19:00 hours) and given free access to food and water throughout the experiment. All behavioral procedures were conducted according to ethical guidelines/regulations approved by the Icahn School of Medicine Animal Care and Use Committee. Animal care and all experimental procedures were in accordance with guidelines from the National Institutes of Health.

Tail Flick Assay.

Mice (7–10/group) were injected i.p. with either vehicle [6% DMSO (vol/vol) in saline], Sal A, or collybolide (2 mg/kg), and antinociception was measured using the tail-flick assay (38). The intensity of the heat source was set to 10 (this results in a basal tail-flick latency of 5–7 s for most animals) and the tail-flick latency was recorded at the indicated time period (0–60 min) after vehicle or drug administration. Cutoff latency was set at 20 s to minimize tissue damage.

CPP/Aversion.

The CPP chambers were housed within a sound attenuating room with red light and contained three distinct sensory environments. The conditioning chambers were differentiated on the basis of wall color and flooring, with the gray conditioning chamber containing a steel mesh floor, the black and white striped conditioning chamber containing a floor made of large steel mesh, and the center white chamber containing a floor made of steel rods. Guillotine doors connect each side compartment to the center compartment. On day 1, mice were placed in the white center compartment and allowed to freely roam the entire apparatus for 20 min. The amount of time spent in each compartment (gray or striped) was recorded to assess the unconditioned preference and then animals were returned to their home cages. Any mouse showing a strong unconditioned preference (>70%) to either chamber was excluded from the experiment. Animals (7–10/group) were administered i.p. with vehicle in one chamber and 8 h later with vehicle/collybolide (2 mg/kg, i.p.) in the other chamber for 45 min. These injections were repeated for 4 d using an unbiased, counterbalanced design in which half the animals had gray and half had striped chambers as the drug-paired side. On the test day (day 6), animals were placed in the central white chamber and allowed to freely roam the entire apparatus. Time spent in each test compartment was recorded separately for each animal for 20 min. The change of preference was calculated as the difference (in seconds) between the time spent in the drug-paired compartment on the testing day and the time spent in this compartment in the preconditioning session.

Forced Swim Test.

Mice (7–10/group) were injected i.p. with either vehicle [6% DMSO (vol/vol) in saline] or collybolide (2 mg/kg), individually placed inside a glass beaker (height 44 cm, diameter 22 cm) filled with water at a depth of 30 cm, at 25 ± 2 °C and behavior recorded for 6 min. At the end of the test mice were removed, dried, and returned to their home cages. Mice were scored blind for the treatment conditions for time spent immobile.

Elevated Plus Maze.

Mice (7–10 per group) were injected i.p. with either vehicle [6% DMSO (vol/vol) in saline], Sal A, or collybolide (2 mg/kg) placed onto the center of the elevated plus maze and the number of open- and closed-arm entries and the time spent in open arms recorded. Percent time spent in open arms was used as a measure of anxiety. A separate group of animals was administered with nor-BNI (10 mg/kg, i.p.) 20 min before collybolide administration.

Open Field.

Mice were injected with vehicle [6% DMSO (vol/vol) in saline], Colly (2 mg/kg, i.p.), Sal A (2 mg/kg, i.p.), or nor-BNI (10 mg/kg i.p.) + Colly (2 mg/kg, i.p.) 20 min before open field test. Distance traveled (in centimeters) over 10 min was quantified using Ethovision XT tracking system (Noldus).

Chloroquine-Mediated Itch Behavior.

Mice were habituated to an acrylic chamber for 1 h before testing. Ten minutes before inducing itch mice were injected i.p. with vehicle [0.9% saline +2% DMSO (vol/vol)], collybolide, or Sal A (2, 20, 200, and 2,000 µg/kg) over the course of 4 d starting with the lowest dose on day 1. Each mouse was assigned to one group consistently throughout the experiment. To induce itch mice were injected s.c. with chloroquine-phosphate (20 mg/kg) into the base of the neck and were placed into the recording chamber. For experiments involving nor-BNI, on day 1 mice were habituated to the chamber for 1 h and 10 min before inducing itch mice were treated with vehicle to obtain a baseline amount of chloroquine-induced itch. On the next day, this procedure was repeated with mice receiving 200 µg/kg collybolide 10 min before inducing itch. The same cohort of mice were injected i.p. with nor-BNI (10 mg/kg) and 48 h later mice received 200 µg/kg collybolide 10 min before inducing itch. Because nor-BNI’s effects are stable for weeks following injection (49), these mice were assessed for itch 72 h later following a vehicle injection 10 min before inducing itch to examine whether i.p. nor-BNI has an impact on itch. All mice were videotaped for 15 min. The total number of scratches in 5-min intervals were scored by experimenters blinded to the drug treatments. A scratch was defined as hind paw movements directed to the site of injection (30, 39).

Statistical Analysis.

Data were analyzed using Prism 6.0 (Graph Pad) and statistical analysis carried out using t test or one-way ANOVA.

Discussion

Sal A was the first described naturally occurring nonnitrogenous furyl-δ-lactone diterpene agonist of κOR (18). In this study, we show that Collys are potent and selective hκOR agonists, thereby extending the repertoire of naturally occurring furyl-δ-lactone terpenes that function as κOR ligands. It is interesting to note that most κOR ligands, particularly Sal A, exhibit nanomolar affinity for κOR. Interestingly, docking studies using the crystal structure of hκOR bound to the antagonist JDTic suggest that different chemotypes of κOR ligands bind to the same pocket in the receptor (25). We find that epimerization of Colly at C9 reduces agonist binding and signaling. These results suggest that the C9 position makes significant contributions to full binding and signaling at hκOR. The generation of novel ligands based on the Colly structure that could be used in cocrystallization studies with hκOR would help elucidate how Collys bind to κOR.

An observation in this study is that, although Sal A completely displaces radiolabeled binding to hκOR Collys, in particular 9-epi-Colly, do not. This partial displacement of radiolabeled binding could be because (i) Collys exhibit poor solubility in aqueous solutions such that at high concentrations lesser amounts are available for displacement of bound radiolabel; (ii) at high concentrations, Collys bind to a second site in hκOR functioning as an allosteric modulator of bound radiolabeled ligand; (iii) the radiolabeled ligands used in this study stabilize different conformations of the receptor some of which are not accessible for displacement by Collys; and (iv) it is possible that hκOR is complexed with different proteins, and Collys are able to recognize and bind to hκOR only in some of these complexes. Among these possibilities the most probable one particularly in the case of 9-epi-Colly would be poor solubility in aqueous solution. Thus, further studies are needed to explore in detail how Collys bind to hκOR in comparison with naloxone, Dip, and U69 and generation of water-soluble analogs of Collys could help address some of these questions.

Behavioral studies report that Sal A exhibits antinociceptive activity (26), is aversive in rodents (24), dose-dependently increases immobility in the forced swim test (27), is anxiolytic in the elevated plus maze test (28), and can attenuate cocaine-induced drug seeking behavior (29). In this study, we find that Colly, like Sal A, exhibits antinociception and is aversive in mice. However, unlike Sal A, a 2-mg/kg dose of Colly tends to decrease immobility time in the forced swim test, suggesting that Colly may exhibit antidepressant activity. Interestingly, evaluation of the effects of Colly in the open field test suggests that at a dose of 2 mg/kg it tends to be anxiogenic, whereas Sal A has been reported to be anxiolytic (28). Studies examining the effects of Sal A on compound 48/80-induced itch behavior (30) reported low and inconsistent effects in attenuation of scratching behavior. We find that the Sal A-mediated antipruritic effect on chloroquine-mediated itch is low and inconsistent (Fig. 5), whereas Colly-mediated antipruritic effect is consistent and robust (Fig. 5). These properties make Colly an ideal candidate for further studies exploring molecular and behavioral properties of κOR, as well as for the development of novel therapeutics for the treatment of itch and other κOR-mediated pathologies.

A hallmark characteristic of Sal A is that it is a potent hallucinogen. Thus, administration of vaporized Sal A to human volunteers leads to intense psychotropic effects including hallucinations, disconnection from external reality, and altered interoceptive abilities (31). To date, it is not known if Collys exhibit hallucinogenic effects. An extensive web search for information about the fungus C. maculata did not reveal any reports of hallucinogenic properties: only that the fungus is bitter to taste. If it holds true that Collys are not hallucinogenic, this would rule out the involvement of the furyl-δ-lactone motif in the hallucinogenic effects of Sal A. Structure–activity studies comparing modifications in Sal A and Colly structures could help elucidate the motifs required for the hallucinogenic properties. In addition, it would be important to examine the contribution of biased signaling toward the differences in the behavioral effects of Sal A and Colly. Such studies are particularly important given reports that biased signaling at κOR can distinguish the aversive effects of κOR agonists from the antinociceptive effects (8). Consistent with this, studies have shown that, whereas Sal A appears to be an unbiased ligand based on G-protein activation and β-arrestin recruitment assays, a structural derivative, RB-64, appears to exhibit G-protein–biased activity (32). Studies with this compound argue for a contribution of the G-protein pathway in κOR-mediated analgesia and aversion and of other pathways on κOR-mediated motor coordination, sedation, and anhedonia (33). In the present study, we show that Colly exhibits biased agonistic activity and differs from Sal A in blocking chloroquine-mediated itch. This observation makes Colly an ideal compound for further studies. The amenability of the structure of Colly to modifications provides a platform for generation of analogs, thus expanding the repertoire of biased κOR ligands; this could help delineate the signaling pathways in κOR-mediated behaviors and side effects. In sum, our studies show that collybolides represent novel κOR selective agonists. These compounds could be used to further investigate the molecular pharmacology of κOR, explore the role of κOR in vivo, and develop novel therapeutics (agonists, antagonists, and partial agonists) that could be clinically used to treat disorders involving the κOR system.

Materials and Methods

Natural Compounds, Materials, and Analytical Data.

Sal A was from In Solve Scientific, Colly and 9-epi-Colly were from the collection of two of the coauthors (A.C. and J.P.) after their discovery (21) (analytical details in SI Materials and Methods); 10 mM stock solutions of Sal A, Colly, and 9-epi-Colly in DMSO were used in all assays. U69,593 (34), Dyn A8, and protease inhibitor mixture were from Sigma. [3H]Diprenorphine, [3H]Naloxone, [3H]U69,593, and [35S]GTPγS with specific radioactivities of 42.3, 61.1, 37.4, and 1250 Ci/mmol, respectively, were from Perkin-Elmer. κOR KO mice brains were a gift from Charles Chavkin (University of Washington, Seattle).

Cell Culture.

HEK-293 or CHO cells were grown in DMEM or F12 media, respectively, that contained 10% (vol/vol) FBS and penicillin-streptomycin. Cells were transfected with hμOR, hδOR, or hκOR cDNAs using lipofectamine as per the manufacturer’s protocol (Invitrogen). Saturation binding assays using [3H]Naloxone (0–10 nM) show that the cells express similar amounts of receptors (874 ± 240 fmol/mg protein for hμOR, 837 ± 171 for hδOR, and 816 ± 253 for hκOR).

Membrane Preparation.

Membranes were prepared from HEK-293 cells expressing hκOR, hδOR, and hμOR, from cerebral cortex or whole brains of WT or κOR KO mice as described previously (35).

Receptor Displacement Binding Assays.

Glass tubes treated for 10 min with 0.1% (vol/vol) aquaSil-siliconizing fluid in double distilled water were used. Membranes from HEK-cells expressing hμOR, hδOR, or hκOR (200 μg/tube), cerebral cortex, or whole brains (100 μg/tube) of WT or κOR KO mice were incubated with [3H]Diprenorphine, [3H]Naloxone, or [3H]U69,593 (3 nM final concentration) in the presence of different concentrations (10−13–10−5 M) of κOR ligands for 2 h at 30 °C as described previously (35, 36). Details of buffers used are given in SI Materials and Methods.

[35S]GTPγS Binding Assays.

Assays were carried out in glass tubes treated as described above. Membranes (20 μg) were subjected to a [35S]GTPγS binding assay with κOR ligands (10−13–10−5 M) as described previously (35, 36). nor-BNI (10 μM) was added 30 min before the assay.

Measurement of Adenylyl Cyclase Activity.

Membranes (2 μg) were treated with 20 μM forskolin in the absence or presence of κOR ligands (10−13–10−5 M) for 30 min at 37 °C. cAMP levels were determined using the HitHunter cAMP MEM chemiluminescence detection kit from DiscoveRx.

Measurement of ERK1/2 and Akt Phosphorylation.

CHO or HEK-293 cells expressing hκOR, hμOR, or hδOR (2 × 105 cells per well) were treated with vehicle or κOR ligands (10−13–10−6 M) for 3 min at 37 °C. ERK1/2 phosphorylation and Akt phosphorylation at S473 or T308 were measured by Western blot as previously described (36, 37).

Receptor Internalization.

HEK-293 cells expressing hκOR (2 × 105 cells per well) were incubated at 4 °C for 1 h with 1:1,000 anti-HA antibody to label cell surface κOR. Cells were treated without or with 100 nM of κOR ligands for different time intervals (0–120 min) or with different doses (0–1 μM) of κOR ligands for 30 min at 37 °C. Cells were fixed and cell surface receptors determined by ELISA using 1:1,000 dilution (in PBS containing 1% BSA) of anti-rabbit IgG coupled to HRP (Vector Laboratories).

Animal Studies.

Male C57BL/6J mice, 10–12 wk of age (Jackson Laboratories) were housed in groups of three to five per cage in a humidity- and temperature-controlled room with a 12-h light/dark cycle (lights on 07:00–19:00 hours) and given free access to food and water throughout the experiment. Behavioral procedures were according to ethical guidelines/regulations approved by the Icahn School of Medicine Animal Care and Use Committee. Animal care and all experimental procedures were in accordance with guidelines from the National Institutes of Health.

Tail Flick Assay.

Mice (7–10/group) were injected i.p. with vehicle [6% (vol/vol) DMSO in saline], Sal A, or Colly (2 mg/kg), and antinociception was measured using the tail-flick assay (38).

Conditioned Place Preference/Aversion.

Animals (7–10/group) were administered i.p. with vehicle in one chamber and 8 h later with vehicle/Colly (2 mg/kg, i.p.) in the other chamber. These injections were repeated for 4 d using an unbiased, counterbalanced design. On the test day (day 6), animals were placed in the central white chamber, and place preference/aversion was measured for 20 min. Change in preference (seconds) = time spent in drug-paired compartment on test day − time spent in this compartment in the preconditioning session.

Forced Swim Test.

Mice (7–10/group) were injected i.p. with vehicle or Colly (2 mg/kg) and placed inside a glass beaker (height 44 cm, diameter 22 cm) filled with water at a depth of 30 cm, at 25 ± 2 °C, and behavior was recorded for 6 min. Mice were scored blind for the treatment conditions for time spent immobile.

Elevated Plus Maze.

Mice (7–10/group) were injected i.p. with vehicle, Sal A, or Colly (2 mg/kg) and placed onto the center of the elevated plus maze, and the number of open- and closed-arm entries and time spent in open arms were recorded. Percentage time spent in open arms was used as a measure of anxiety. A separate set of animals was given nor-BNI (10 mg/kg, i.p.) 20 min before Colly administration.

Open Field.

Mice were injected with i.p. with vehicle, Colly (2 mg/kg), Sal A (2 mg/kg), or nor-BNI (10 mg/kg) + Colly (2 mg/kg) 20 min before the open field test. Distance traveled (cm) over 10 min was quantified using Ethovision XT tracking system (Noldus).

Chloroquine-Mediated Itch Behavior.

Mice (7–10/group) were injected i.p. with vehicle (0.9% saline + 2% DMSO), Colly, or Sal A (2–2,000 µg/kg) 10 min before inducing itch. To induce itch, mice were injected s.c. with chloroquine-phosphate (20 mg/kg) into the base of the neck, placed into the recording chamber, and videotaped for 15 min. Total number of scratches in 5-min intervals were scored by experimenters blinded to the drug treatments. A scratch was defined as hind paw movements directed to the site of injection (30, 39). Another set of animals was evaluated for the effect of nor-BNI on collybolide-mediated itch attenuation.

Statistical Analysis.

Data were analyzed using Prism 6.0 (Graph Pad), and statistical analysis was carried out using t test or one-way ANOVA.

Acknowledgments

We thank Darlene Pena, Andrei Jeltyi, and Lindsay Lueptow for help with behavioral studies, members of the L.A.D. laboratory for active scientific discussions, Prof. Charles Chavkin for the gift of κOR KO mouse brains, Drs. Susan Nimmo and Markus Voehler for NMR, Drs. Douglas R. Powell and Brice Kauffmann for X-ray crystallographic analyses, and Robert Chartier (Association des Botanistes et Mycologues Amateurs de la Région de Senlis) for his contribution in collecting C. maculata. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants DA008863 and NS026880 (to L.A.D.). E.N.B. is supported by National Institutes of Health Grant T32 DA007135, and I.S. is supported by a startup grant from University of Oklahoma. This work is dedicated to the memory of Prof. Pierre Potier, co-discoverer of collybolide.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1521825113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Kieffer BL, Gavériaux-Ruff C. Exploring the opioid system by gene knockout. Prog Neurobiol. 2002;66(5):285–306. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(02)00008-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gavériaux-Ruff C. Opiate-induced analgesia: Contributions from mu, delta and kappa opioid receptors mouse mutants. Curr Pharm Des. 2013;19(42):7373–7381. doi: 10.2174/138161281942140105163727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Waldhoer M, Bartlett SE, Whistler JL. Opioid receptors. Annu Rev Biochem. 2004;73:953–990. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.073940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dykstra LA, Gmerek DE, Winger G, Woods JH. Kappa opioids in rhesus monkeys. I. Diuresis, sedation, analgesia and discriminative stimulus effects. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1987;242(2):413–420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pasternak GW. Multiple opiate receptors: [3H]ethylketocyclazocine receptor binding and ketocyclazocine analgesia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1980;77(6):3691–3694. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.6.3691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu-Chen LY. Agonist-induced regulation and trafficking of kappa opioid receptors. Life Sci. 2004;75(5):511–536. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2003.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hang A, Wang YJ, He L, Liu JG. The role of the dynorphin/κ opioid receptor system in anxiety. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2015;36(7):783–790. doi: 10.1038/aps.2015.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bruchas MR, Chavkin C. Kinase cascades and ligand-directed signaling at the kappa opioid receptor. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2010;210(2):137–147. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-1806-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tao YM, et al. LPK-26, a novel kappa-opioid receptor agonist with potent antinociceptive effects and low dependence potential. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008;584(2-3):306–311. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wee S, Koob GF. The role of the dynorphin-kappa opioid system in the reinforcing effects of drugs of abuse. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2010;210(2):121–135. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-1825-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prevatt-Smith KM, et al. Potential Drug Abuse Therapeutics Derived from the Hallucinogenic Natural Product Salvinorin A. MedChemComm. 2011;2(12):1217–1222. doi: 10.1039/C1MD00192B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rivière PJ. Peripheral kappa-opioid agonists for visceral pain. Br J Pharmacol. 2004;141(8):1331–1334. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Land BB, et al. Activation of the kappa opioid receptor in the dorsal raphe nucleus mediates the aversive effects of stress and reinstates drug seeking. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(45):19168–19173. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910705106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bruchas MR, Land BB, Chavkin C. The dynorphin/kappa opioid system as a modulator of stress-induced and pro-addictive behaviors. Brain Res. 2010;1314:44–55. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.08.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pradhan AA, Smith ML, Kieffer BL, Evans CJ. Ligand-directed signalling within the opioid receptor family. Br J Pharmacol. 2012;167(5):960–969. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.02075.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carlezon WA, Jr, Béguin C, Knoll AT, Cohen BM. Kappa-opioid ligands in the study and treatment of mood disorders. Pharmacol Ther. 2009;123(3):334–343. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Redila VA, Chavkin C. Stress-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking is mediated by the kappa opioid system. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2008;200(1):59–70. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1122-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roth BL, et al. Salvinorin A: A potent naturally occurring nonnitrogenous kappa opioid selective agonist. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99(18):11934–11939. doi: 10.1073/pnas.182234399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prisinzano TE, Rothman RB. Salvinorin A analogs as probes in opioid pharmacology. Chem Rev. 2008;108(5):1732–1743. doi: 10.1021/cr0782269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Connolly J, Hill RA. Dictionary of Terpenoids. Chapman & Hall; London: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bui AM, Cave A, Janot MM, Parello J, Potier P. Isolation and structural-analysis of Collybolide: New sesquiterpene extracted from Collybia maculata Alb and Sch Ex Fries (Basidiomycetes) Tetrahedron. 1974;30(11):1327–1336. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lawrence DM, Bidlack JM. The kappa opioid receptor expressed on the mouse R1.1 thymoma cell line is coupled to adenylyl cyclase through a pertussis toxin-sensitive guanine nucleotide-binding regulatory protein. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1993;266(3):1678–1683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DiMattio KM, Ehlert FJ, Liu-Chen LY. Intrinsic relative activities of κ opioid agonists in activating Gα proteins and internalizing receptor: Differences between human and mouse receptors. Eur J Pharmacol. 2015;761:235–244. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2015.05.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang Y, Butelman ER, Schlussman SD, Ho A, Kreek MJ. Effects of the plant-derived hallucinogen salvinorin A on basal dopamine levels in the caudate putamen and in a conditioned place aversion assay in mice: Agonist actions at kappa opioid receptors. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2005;179(3):551–558. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-2087-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vardy E, et al. Chemotype-selective modes of action of κ-opioid receptor agonists. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(48):34470–34483. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.515668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McCurdy CR, Sufka KJ, Smith GH, Warnick JE, Nieto MJ. Antinociceptive profile of salvinorin A, a structurally unique kappa opioid receptor agonist. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2006;83(1):109–113. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2005.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carlezon WA, Jr, et al. Depressive-like effects of the kappa-opioid receptor agonist salvinorin A on behavior and neurochemistry in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;316(1):440–447. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.092304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Braida D, et al. Potential anxiolytic- and antidepressant-like effects of salvinorin A, the main active ingredient of Salvia divinorum, in rodents. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;157(5):844–853. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00230.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morani AS, Kivell B, Prisinzano TE, Schenk S. Effect of kappa-opioid receptor agonists U69593, U50488H, spiradoline and salvinorin A on cocaine-induced drug-seeking in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2009;94(2):244–249. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang Y, et al. Comparison of pharmacological activities of three distinct kappa ligands (Salvinorin A, TRK-820 and 3FLB) on kappa opioid receptors in vitro and their antipruritic and antinociceptive activities in vivo. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;312(1):220–230. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.073668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maqueda AE, et al. Salvinorin-A induces intense dissociative effects, blocking external sensory perception and modulating interoception and sense of body ownership in humans. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2015;18(12):pyv065. doi: 10.1093/ijnp/pyv065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.White KL, et al. Identification of novel functionally selective κ-opioid receptor scaffolds. Mol Pharmacol. 2014;85(1):83–90. doi: 10.1124/mol.113.089649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.White KL, et al. The G protein-biased κ-opioid receptor agonist RB-64 is analgesic with a unique spectrum of activities in vivo. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2015;352(1):98–109. doi: 10.1124/jpet.114.216820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tomasiewicz HC, Todtenkopf MS, Chartoff EH, Cohen BM, Carlezon WA., Jr The kappa-opioid agonist U69,593 blocks cocaine-induced enhancement of brain stimulation reward. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;64(11):982–988. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.05.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gomes I, Filipovska J, Jordan BA, Devi LA. Oligomerization of opioid receptors. Methods. 2002;27(4):358–365. doi: 10.1016/s1046-2023(02)00094-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gomes I, Filipovska J, Devi LA. Opioid receptor oligomerization. Detection and functional characterization of interacting receptors. Methods Mol Med. 2003;84:157–183. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-379-8:157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Trapaidze N, Gomes I, Cvejic S, Bansinath M, Devi LA. Opioid receptor endocytosis and activation of MAP kinase pathway. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2000;76(2):220–228. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(00)00002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gomes I, et al. Identification of a μ-δ opioid receptor heteromer-biased agonist with antinociceptive activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(29):12072–12077. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1222044110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morgenweck J, Frankowski KJ, Prisinzano TE, Aubé J, Bohn LM. Investigation of the role of βarrestin2 in kappa opioid receptor modulation in a mouse model of pruritus. Neuropharmacology. 2015;99:600–609. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2015.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Valdes LJ, Butler WM, Hatfield GM, Paul AG, Koreeda M. Divinorin-a, a psychotropic terpenoid, and divinorin-B from the hallucinogenic Mexican mint Salvia divinorum. J Org Chem. 1984;49(24):4716–4720. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Munro TA. 2006. The chemistry of Salvia divinorum. PhD thesis (The University of Melbourne, Parkville, Australia), pp 91–92.

- 42.Moncalvo JM, Lutzoni FM, Rehner SA, Johnson J, Vilgalys R. Phylogenetic relationships of agaric fungi based on nuclear large subunit ribosomal DNA sequences. Syst Biol. 2000;49(2):278–305. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/49.2.278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sheldrick GM. SHELXT - integrated space-group and crystal-structure determination. Acta Crystallogr A Found Adv. 2015;71(Pt 1):3–8. doi: 10.1107/S2053273314026370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sheldrick GM. Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL. Acta Crystallogr C Struct Chem. 2015;71(Pt 1):3–8. doi: 10.1107/S2053229614024218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hooft RWW, Straver LH, Spek AL. Determination of absolute structure using Bayesian statistics on Bijvoet differences. J Appl Cryst. 2008;41(Pt 1):96–103. doi: 10.1107/S0021889807059870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Castronovo F, Clericuzio M, Toma L, Vidari G. Fungal metabolites. Part 45: The sesquiterpenes of Collybia maculata and Collybia peronata. Tetrahedron. 2001;57(14):2791–2798. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gupta A, Gomes I, Wardman J, Devi LA. Opioid receptor function is regulated by post-endocytic peptide processing. J Biol Chem. 2014;289(28):19613–19626. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.537704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gupta A, Fujita W, Gomes I, Bobeck E, Devi LA. Endothelin-converting enzyme 2 differentially regulates opioid receptor activity. Br J Pharmacol. 2015;172(2):704–719. doi: 10.1111/bph.12833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bruchas MR, et al. Long-acting kappa opioid antagonists disrupt receptor signaling and produce noncompetitive effects by activating c-Jun N-terminal kinase. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(41):29803–29811. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705540200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]