Abstract

Chlamydia spp. are important causes of human disease for which no effective vaccine exists. These obligate intracellular pathogens replicate in a specialized membrane compartment and use a large arsenal of secreted effectors to survive in the hostile intracellular environment of the host. In this Review, we summarize the progress in decoding the interactions between Chlamydia spp. and their hosts that has been made possible by recent technological advances in chlamydial proteomics and genetics. The field is now poised to decipher the molecular mechanisms that underlie the intimate interactions between Chlamydia spp. and their hosts, which will open up many exciting avenues of research for these medically important pathogens.

Chlamydiae are Gram-negative, obligate intracellular pathogens and symbionts of diverse organisms, ranging from humans to amoebae1. The best-studied group in the Chlamydiae phylum is the Chlamydiaceae family, which comprises 11 species that are pathogenic to humans or animals1. Some species that are pathogenic to animals, such as the avian pathogen Chlamydia psittaci, can be transmitted to humans1,2. The mouse pathogen Chlamydia muridarum is a useful model of genital tract infections3. Chlamydia trachomatis and Chlamydia pneumoniae, the major species that infect humans, are responsible for a wide range of diseases2,4 and will be the focus of this Review. Strains of C. trachomatis are divided into three biovars and are further subtyped by serovar. The trachoma biovar (serovars A–C) is the leading cause of non-congenital blindness in developing nations, whereas the genital tract biovar (serovars D–K) is the most prevalent sexually transmitted bacterium. In women, 70–80% of genital tract infections with C. trachomatis are asymptomatic, but 15–40% ascend to the upper genital tract, which can lead to serious sequelae, including pelvic inflammatory disease, infertility and ectopic pregnancy4. The lympho granuloma venereum (LGV) biovar (serovars L1–L3) causes invasive urogenital or anorectal infection, and in the past 10 years, the incidence of LGV in HIV-infected men who have sex with men has increased5. Infection with C. trachomatis also facilitates the transmission of HIV and is associated with cervical cancer4. C. pneumoniae causes respiratory infections, accounting for ~10% of community-acquired pneumonia, and is linked to a number of chronic diseases, including asthma, atherosclerosis and arthritis1,2. Although chlamydial infection is treatable with antibiotics, no drug is sufficiently cost-effective for the elimination of the bacterium in developing nations, and an effective vaccine has thus far been elusive6.

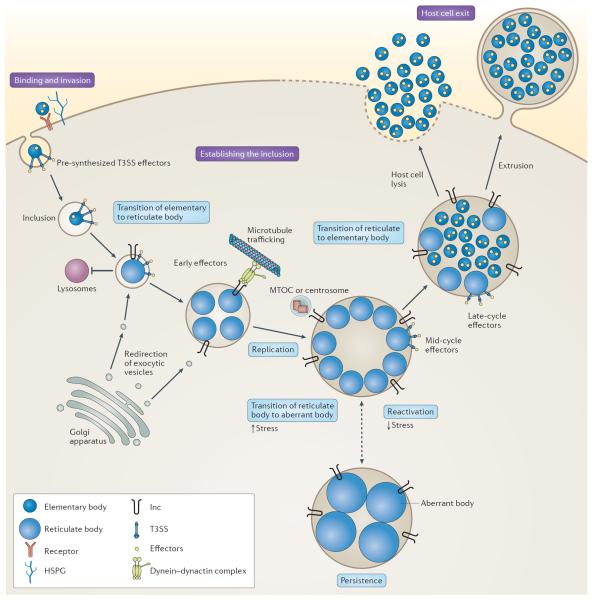

All chlamydiae share a developmental cycle in which they alternate between the extracellular, infectious elementary body and the intracellular, non-infectious reticulate body7 (FIG. 1). Elementary bodies enter mucosal cells and differentiate into reticulate bodies in a membrane bound compartment — the inclusion. After several rounds of replication, reticulate bodies re-differentiate into elementary bodies and are released from the host cell, ready to infect neighbouring cells.

Figure 1. The life cycle of Chlamydia trachomatis.

The binding of elementary bodies to host cells is initiated by the formation of a trimolecular bridge between bacterial adhesins, host receptors and host heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs). Next, pre-synthesized type III secretion system (T3SS) effectors are injected into the host cell, some of which initiate cytoskeletal rearrangements to facilitate internalization and/or initiate mitogenic signalling to establish an anti-apoptotic state. The elementary body is endocytosed into a membrane-bound compartment, known as the inclusion, which rapidly dissociates from the canonical endolysosomal pathway. Bacterial protein synthesis begins, elementary bodies convert to reticulate bodies and newly secreted inclusion membrane proteins (Incs) promote nutrient acquisition by redirecting exocytic vesicles that are in transit from the Golgi apparatus to the plasma membrane. The nascent inclusion is transported, probably by an Inc, along microtubules to the microtubule-organizing centre (MTOC) or centrosome. During mid-cycle, the reticulate bodies replicate exponentially and secrete additional effectors that modulate processes in the host cell. Under conditions of stress, the reticulate bodies enter a persistent state and transition to enlarged aberrant bodies. The bacteria can be reactivated upon the removal of the stress. During the late stages of infection, reticulate bodies secrete late-cycle effectors and synthesize elementary-body-specific effectors before differentiating back to elementary bodies. Elementary bodies exit the host through lysis or extrusion.

Chlamydiae have substantially reduced genomes (1.04 Mb encoding 895 open reading frames for C. trachomatis) that lack many metabolic enzymes8, which makes these bacteria reliant on the host for many of their metabolic requirements. Approximately two-thirds of predicted proteins are shared across species, which reflects genetic conservation and the evolutionary constraints that are imposed by their intracellular lifestyle and conserved developmental cycle1,9. One exception is a region of high genomic diversity termed the `plasticity zone', which encodes an array of virulence factors, including cytotoxin, membrane attack complex/perforin protein (MACPF) and phospholipase D, which may have a role in host tropism and niche specificity1,9. Chlamydiae encode a large number of virulence effectors, which comprise ~10% of their genome10. These effectors are delivered through specialized secretion systems to the bacterial surface (by a type V secretion system (T5SS)), the inclusion lumen (by a type II secretion system (T2SS)), or into the host cell cytosol or inclusion membrane (by a type III secretion system (T3SS))11 (BOX 1). In addition, most strains carry a plasmid that contributes to virulence12. In this Review, we summarize the current understanding of chlamydial biology, highlighting recent advances in host and bacterial cell biology, proteomics and chlamydial genetics, and areas that we expect to progress substantially in the coming decade.

Box 1 | Inclusion membrane proteins: a unique set of T3SS effectors.

The type III secretion system (T3SS) is a needle-like molecular syringe that enables the direct injection of bacterial effector molecules across host membranes150. Chlamydia spp. use the T3SS at various stages of infection, including during initial host cell contact with the plasma membrane and during the intracellular phase, in which effectors are injected into the cytosol of the host cell and can access other intracellular compartments, such as the nucleus11. The T3SS is spatially restricted in chlamydiae, with needle complexes localized to one pole of the elementary body39 or concentrated at the site at which reticulate bodies contact the inclusion membrane93. Chlamydiae produce a unique family of T3SS effectors termed inclusion membrane proteins (Incs)16,20, of which there are 36–107 depending on the species151,152. These effectors are translocated across, and inserted into, the inclusion membrane, in which they are ideally positioned to mediate host–pathogen interactions20. The defining feature of Incs is one or more bilobed hydrophobic domains composed of two closely spaced membrane-spanning regions that are separated by a short hairpin loop, with their amino terminus and/or carboxyl terminus predicted to extend into the cytoplasm of the host cell16. Incs are primarily expressed early during infection, when they may be important in the establishment of the inclusion, and at mid-cycle, when they may be involved in the maintenance of the inclusion and the acquisition of nutrients20. Genome-wide comparisons reveal a core set of Incs that are shared across Chlamydia spp. as well as diverse species-specific Incs that may be key determinants of host tropism and site-specific disease151,152. Incs share little homology to each other or to other known proteins, with the exception of coiled-coil or soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment protein receptor (SNARE)-like domains, which provides limited insight into their functions16. Incs are hypothesized to recruit host proteins to the inclusion membrane to promote fusion with nutrient-rich compartments, inhibit fusion with degradative compartments, hijack host machinery or organelles, disrupt normal host pathways, or assemble novel complexes with new functions20. The Inc–host interactions identified thus far indicate that Incs participate in numerous processes, including the rearrangement of the host cell cytoskeleton, membrane dynamics, centrosome tethering, lipid acquisition and resistance to apoptosis20 (FIG 2a,b). In addition, Incs form homotypic or heterotypic complexes on the surface of the inclusion65,116. Finally, Incs may provide structural stability to the growing inclusion membrane153. A large-scale proteomic screen of Incs in Chlamydia trachomatis has revealed putative host binding partners for approximately two-thirds of Incs67. Together with the recent description of the proteome of purified mid-cycle inclusions68, a comprehensive landscape of Inc–host interactions is developing.

The developmental cycle

Elementary bodies and reticulate bodies are morphologically and functionally distinct. Elementary bodies survive in the harsh extracellular environment; their spore-like cell wall is stabilized by a network of proteins that are crosslinked by disulfide bonds, termed the outer membrane complex, which confers resistance to osmotic stress and physical stress13. Although they were once considered to be metabolically inactive, studies using a host-free (axenic) system indicate that elementary bodies have high metabolic and biosynthetic activities and depend on d-glucose-6-phosphate as a source of energy14. Indeed, quantitative proteomics reveal that elementary bodies contain an abundance of proteins that are required for central metabolism and glucose catabolism15, which might be used for a burst of metabolic activity on host cell entry and drive differentiation into reticulate bodies. During this differentiation, the crosslinked complexes are reduced, which provides the membrane fluidity that is required for replication13. Reticulate bodies specialize in nutrient acquisition and replication7; they highly express proteins that are involved in the generation of ATP, protein synthesis and nutrient transport, such as V-type ATP synthases, ribosomal proteins and nucleotide transporters15. They probably rely on ATP scavenged from the host as an energy source, which indicates that the two developmental forms have distinct metabolic requirements14.

Binding to the host cell involves several bacterial ligands and host receptors16–18 (FIG. 1). On contact, pre-synthesized T3SS effectors are injected15 and the elementary body is internalized into the inclusion. In a few hours (6–8 hours post-infection for C. trachomatis), the transition to reticulate body takes place and early genes are transcribed19. Early effectors remodel the inclusion membrane, redirect exocytic vesicles to the inclusion and facilitate host–pathogen interactions20. Next, (~8–16 hours post-infection for C. trachomatis) mid-cycle genes are expressed, which include effectors that mediate nutrient acquisition and maintain the viability of the host cell. The bacteria divide by binary fission and the inclusion substantially expands. For some species, such as C. trachomatis, the infection of a single cell by several elementary bodies generates individual inclusions that fuse with each other by homotypic fusion16,21. At late stages (~24–72 hours post-infection for C. trachomatis), reticulate bodies transition to elementary bodies in an asynchronous manner, which might be stimulated by their detachment from the inclusion membrane11. Late-cycle genes encode the outer membrane complex and the DNA binding histone H1-like and H2-like proteins, Hc1 and Hc2, which condense DNA and switch off the transcription of many genes19. Some late-cycle effectors that are generated at this time are packaged in progeny elementary bodies to be discharged in the next cycle of infection11,15.

This developmental cycle requires the finely tuned temporal expression of stage-specific factors, which involves alternative sigma factors, transcriptional activators and repressors, response regulators, small RNAs and regulators of DNA supercoiling19. The temporal classes of chlamydial genes mirror the stages of development. Although it is unclear how incoming elementary bodies become transcriptionally competent, early genes may be constitutively active or transcribed from supercoiling-insensitive promoters, as the level of supercoiling is low during the early stages of development19. Mid-cycle gene expression is driven by promoters that are responsive to increased DNA supercoiling, which is probably mediated by DNA gyrases that are expressed early during development19. The expression of mid-cycle genes may also be regulated by the atypical response regulator ChxR19,22. Late genes are regulated either by a stage-specific sigma factor (σ28)19 or through the relief of transcriptional repression of σ66-dependent promoters by the repressor early upstream open reading frame (EUO)19,23. Transcriptional regulation is also coupled to the T3SS24–26. Much of this insight comes from in vitro studies; advances in chlamydial genetics (BOX 2) will enable the analysis of current models in vivo.

Box 2 | Advances in the genetic manipulation of Chlamydia spp.

After intensive efforts that have spanned decades, the genetic manipulation of chlamydiae has finally been successful. In retrospect, nature has provided numerous clues that genetic exchange with non-self DNA is limited in chlamydiae. The elementary body is relatively impermeable, whereas the reticulate body, which readily exchanges DNA, is separated from the external environment13. Chlamydiae lack genes that encode restriction and modification enzymes and harbour few, if any, vestiges of horizontal gene transfer, which is consistent with a lack of genetic exchange with other organisms8. Although chlamydial phages have been identified, they have not proven useful for the transduction of foreign DNA thus far154. Early attempts to transform Chlamydia spp. with shuttle vectors based on the Chlamydia `cryptic' plasmid resulted in only transient transformation155, possibly owing to the truncation of a gene that is essential for the maintenance of the plasmid146. Several recent breakthroughs have changed the landscape. First, gene replacement at the single rRNA locus in Chlamydia psittaci was achieved using classic allelic exchange combined with the elegant use of rRNA-specific drug-resistance markers156. This was a remarkable feat considering the inherent inefficiencies of a procedure that requires both transformation and homologous recombination. Second, a more efficient transformation protocol, using calcium chloride treatment of elementary bodies, was used to transform Chlamydia trachomatis with a shuttle vector that was derived from the naturally occurring C. trachomatis plasmid157. This shuttle vector also expresses the β-lactamase gene, which enables the selection of stable transformants with penicillin157. There is now an increasing number of shuttle vectors that enable the plasmid-based expression of genes that are fused to epitope tags, fluorescent proteins or secretion system reporters for the identification of effectors that are either under the control of inducible or native promoters75,158–162. Third, conventional chemical mutagenesis combined with whole-genome sequencing was used to construct a library of mapped C. trachomatis mutants45,81,98,163. By taking advantage of natural intra-inclusion genetic exchange between reticulate bodies164, mutants can be backcrossed with the parental strain to link genotype and phenotype. This approach, together with libraries that are generated by targeted mutagenesis165, will be useful for forward genetic screens and for identifying essential genes. Finally, several new strategies for creating targeted gene knockouts, including TILLING (targeting induced local lesions in genomes) and type II intron-mediated gene insertion, have been successfully used in Chlamydia spp.166,167. These recent successes will enable investigators to link genotypes with phenotypes and pave the way to test Koch's postulates with this obligate intracellular bacterium.

The developmental cycle can be reversibly arrested by environmental factors and stresses, such as nutrient deprivation, exposure to host cytokines and antibiotics that target cell wall synthesis27 (FIG. 1). Under these conditions, reticulate bodies transition to aberrantly enlarged, non-dividing `persistent' forms. Persistence may represent a stealthy approach to evade the immune system of the host. Although persistence might contribute to chronic inflammation and scarring, hallmarks of chlamydial disease, it remains controversial as to whether persistence occurs in vivo3.

Binding and invasion

The adhesion and invasion of Chlamydia spp. relies on numerous host and bacterial factors16–18 (FIGS 1,2a). The diversity in binding and internalization mechanisms between species probably contributes to differences in tropism for specific hosts and tissues. The adhesion of C. trachomatis, C. pneumoniae and C. muridarum is a two-step process that is mediated by a low-affinity interaction with heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs) followed by high-affinity binding to host cell receptors17. OmcB (also known as CT443) from C. trachomatis L1 or C. pneumoniae mediates attachment to HSPGs17. The level and position of sulfation in HSPGs have important roles in the binding of C. muridarum and C. trachomatis L2 (REFS 17,28,29) and may contribute to tissue tropism. Other adhesins include lipopolysaccharide (LPS) in C. trachomatis, which is proposed to bind to the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator17,30, major outer membrane protein (MOMP; also known as CT681), which binds to the mannose receptor and the mannose 6-phosphate receptor18, and CT017 (also known as Ctad1) in C. trachomatis, which binds to β1 integrin31. The polymorphic membrane protein (Pmp) family in C. trachomatis and C. pneumoniae also mediates adhesion32. Pmp21 (also known as Cpn0963) binds to the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and functions as both an adhesin and an invasin32,33.

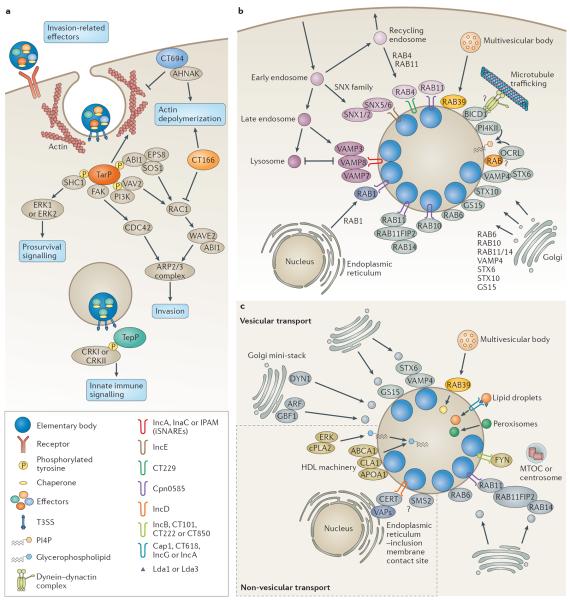

Figure 2. Chlamydia–host interactions.

a | Elementary bodies contain pre-synthesized type III secretion system (T3SS) effectors along with their respective chaperones. On contact with host cells, invasion-related effectors are injected through the T3SS to induce cytoskeletal rearrangements and host signalling. In Chlamydia trachomatis, translocated actin-recruiting phosphoprotein (TarP), CT166 and CT694 are secreted first followed by TepP. TarP and TepP are tyrosine phosphorylated by host kinases. Phosphorylated TarP interacts with SRC homology 2 domain-containing transforming protein C1 (SHC1) to activate extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1 (ERK1; also known as MAPK3) and ERK2 (also known as MAPK1) for pro-survival signalling, whereas other phosphorylated TarP residues mediate interactions with two RAC guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs), VAV2 and son of sevenless homologue 1 (SOS1). SOS1 is part of a multiprotein complex with ABL interactor 1 (ABI1) and epidermal growth factor receptor kinase substrate 8 (EPS8) in which ABI1 is thought to mediate the interaction of the complex with phosphorylated TarP, which leads to the activation of RAS-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate 1 (RAC1) and the host actin-related protein 2/3 (ARP2/3) complex. Phosphorylated TarP binds to the p85 subunit of phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K), producing phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-triphosphate PI(3,4,5)P3, which may activate VAV2. TarP also directly mediates the formation of actin filaments. TarP orthologues in Chlamydia caviae (which do not contain phosphorylation sites) bind to focal adhesion kinase (FAK) through a mammalian leucine–aspartic acid (LD2)-like motif and activate cell division control protein 42 (CDC42)-related actin assembly. CT694 contains a membrane-binding domain and interacts with the AHNAK protein, which links the membrane to the rearrangement of actin. CT166 glycosylates and inactivates RAC1. TarP activates the polymerization of actin, whereas CT694 and CT166 promote the depolymerization of actin. Phosphorylated TepP interacts with CRKI and CRKII to initiate innate immune signalling. b | The chlamydial inclusion is actively remodelled by host proteins and bacterial inclusion membrane proteins (Incs). Incs may regulate fusion with intracellular compartments and modulate membrane dynamics. Several RAB GTPases localize to the inclusion, including RAB4 and RAB11, which are recruited from recycling endosomes soon after entry by CT229 in C. trachomatis and Cpn0585 in Chlamydia pneumoniae, respectively. RAB11 is also recruited from the Golgi apparatus and binds to RAB11 family-interacting protein 2 (RAB11FIP2) to promote the recruitment of RAB14. RAB1 is recruited from the endoplasmic reticulum, whereas RAB6 and RAB10 relocalize from the Golgi apparatus. The RAB effector bicaudal-D homologue 1 (BICD1) may link the inclusion to dynein for transport along microtubules. The phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate (PI4P)-producing enzymes OCRL1 and phosphatidylinositol-4-kinase type IIα (PI4KIIα) are recruited and may generate PI4P. Sorting nexin 5 (SNX5) and SNX6 are recruited from early endosomes by IncE to remodel the inclusion membrane and potentially inhibit retromer trafficking. RAB39a regulates the interaction between multivesicular bodies and the inclusion. Several soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment protein receptors (SNAREs) are recruited, including the Golgi-specific SNAREs vesicle-associated membrane protein 4 (VAMP4), syntaxin 6 (STX6) and GS15. In addition, the endocytic SNAREs, VAMP 3, VAMP 7 and VAMP 8, are recruited by IncA, InaC and inclusion protein acting on microtubules (IPAM), and are thought to act as inhibitory SNAREs (iSNAREs) to block the fusion with lysosomes. c | Chlamydia spp. interact with several subcellular compartments to acquire essential lipids. Sphingomyelin and cholesterol are incorporated into reticulate body membranes by intercepting vesicles from fragmented Golgi mini-stacks and multivesicular bodies. The trafficking of lipid-containing vesicles from Golgi mini-stacks is regulated by the GBF1-dependent activation of ADP-ribosylation factor (ARF) GTPases, by dynein heavy chain (DYN1) GTPase, and by Golgi-associated SNAREs and RABs. RAB39 mediates the interaction between the inclusion and multivesicular bodies. Lipid droplets and peroxisomes are translocated into the inclusion. Lipid droplets may be intercepted by Lda1 or Lda3, or by the Incs: Cap1, CT618, IncG and IncA. FYN kinase signalling from Inc microdomains that contain IncB, CT101, CT222 and CT850, contributes to lipid acquisition, possibly through the positioning of the inclusion at the microtubule-organizing centre (MTOC) or centrosome. Non-vesicular mechanisms of lipid acquisition involve the formation of endoplasmic reticulum–inclusion membrane contact sites (mediated by vesicle-associated membrane proteins (VAPs), the lipid transporter ceramide endoplasmic reticulum transport protein (CERT), and IncD), the recruitment of members of the high-density lipoprotein (HDL) machinery, and ERK signalling. The sphingomyelin biosynthetic enzyme, sphingomyelin synthase 2 (SMS2), may convert ceramide to sphingomyelin directly on the inclusion. ABCA1, ATP-binding cassette transporter 1; APOA1, apolipoprotein A1; CLA1, CD36 and LIMPII analagous 1; cPLA2, cytosolic phospholipase A2; WAVE2, Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome protein family member 2.

In addition to the β1 integrin subunit31 and EGFR33, receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) contribute to binding, invasion and signalling during entry. C. trachomatis and C. muridarum interact with the fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR) and its ligand FGF as well as platelet derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR)34,35. C. trachomatis also binds to ephrin receptor A2 (EPHA2) to activate downstream signalling36, whereas apolipoprotein E4 may be a receptor for C. pneumoniae37. Finally, protein disulfide isomerase (PDI), a component of the oestrogen receptor complex, is implicated in the attachment and entry of many Chlamydia spp.16,18. PDI may also reduce the disulfide bonds in adhesins, host receptors and/or the T3SS13,38.

On contact with host cells, Chlamydia spp. induce actin remodelling, which promotes rapid internalization16,39 (FIG. 2a). RHO-family GTPases, which are regulators of actin polymerization, are required for internalization, but the specific GTPase, or GTPases, differs between species7; RAS-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate 1 (RAC1) is required for the entry of C. trachomatis, whereas cell division control protein 42 (CDC42) and ADP-ribosylation factor 6 (ARF6) contribute to the entry of Chlamydia caviae18. The activation of RAC1 results in the recruitment of the actin regulators, Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome protein family member 2 (WAVE2; also known as WASF2), ABL interactor 1 (ABI1), actin-related protein 2 (ARP2) and ARP3, which are necessary for the reorganization of actin18. Actin polymerization is accompanied by extensive membrane remodelling16,39,40, which is driven by several host factors, including caveolin, clathrin and cholesterol-rich microdomains7,41.

Pre-packaged effectors are injected through the T3SS to induce cytoskeletal rearrangements that promote invasion and activate host signalling42 (FIG. 2a). Translocated actin-recruiting phosphoprotein (TarP; also known as CT456) is a multidomain protein that nucleates and bundles actin through its own globular actin (G-actin) and filamentous actin (F-actin) domains and is thought to synergize with the host ARP2/3 complex16,43. In addition, TarP in C. caviae contains a mammalian leucine–aspartic acid (LD2)-like motif that subverts focal adhesion kinase (FAK) signalling44. Some TarP orthologues contain an amino-terminal domain with 1–9 tyrosine-containing repeats, which are phosphorylated by ABL and SRC-family tyrosine kinases (SFKs)16. These phosphorylated residues participate in signalling for RAC-mediated actin rearrangements through VAV2 and son of sevenless homologue 1 (SOS1) and promote host cell survival through SRC homology 2 domain-containing transforming protein C1 (SHC1)16,18. TepP (also known as CT875), another T3SS effector that is phosphorylated by host tyrosine kinases, recruits the eukaryotic adaptor proteins CRKI and CRKII to the inclusion45. Both TarP and TepP, together with CT694 and CT695, use the chaperone Slc1 (also known as CT043) for secretion. The differential binding of TarP and TepP to Slc1 may explain the order of effector secretion, with TarP being secreted before TepP45,46. The T3SS effector CT694 is a multidomain protein that includes a membrane localization and an actin-binding AHNAK domain, which is thought to disrupt actin dynamics by interacting with the actin-binding protein AHNAK11,47. C. psittaci contains a weak orthologue of CT694, secreted inner nuclear membrane protein in Chlamydia (SINC; also known as G5Q_0070), which targets a conserved component of the nuclear `lamina' (REF. 48) and may reflect pathogenic diversity between C. trachomatis and C. psittaci. The cytotoxin CT166, which resides in the plasticity zone of C. trachomatis genital strains, C. muridarum and C. caviae, inactivates the RHO GTPase RAC1 by glycosylation, which may reverse actin polymerization after entry7,11.

Establishing an intracellular niche

Migration to the microtubule organizing centre

Nascent inclusions of some Chlamydia spp., including C. trachomatis and C. pneumoniae, are transported along microtubules to the microtubule-organizing centre (MTOC), which requires microtubule polymerization, the motor protein dynein and SFKs16,49 (FIG. 1). This facilitates interactions with nutrient-rich compartments and homotypic fusion50. Although some components of the dynactin complex are recruited, transport along micro tubules does not require p50 dynamitin16,49, which usually links cargo to microtubules. This suggests that bacterial effectors mimic the cargo-binding activity and possibly tether the inclusion to dynein and/or centrosomes. Four inclusion membrane proteins (Incs) in C. trachomatis (IncB (also known as CT232), CT101, CT222 and CT850) reside in cholesterol-rich microdomains at the point of centrosome–inclusion contact and colocalize with active SFKs16,49, which makes it likely that these Incs participate in transport. CT850 from C. trachomatis can directly bind to dynein light chain 1 (DYNLT1) to promote the positioning of the inclusion at the MTOC51. IncB from C. psittaci binds to Snapin, a protein that associates with host SNARE proteins (soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment protein receptor proteins)52. As Snapin can bind to both IncB and to dynein, it is possible that IncB–Snapin interactions connect the inclusion to the dynein motor complex for transport.

Regulation of fusion and membrane dynamics

The intracellular survival of Chlamydia spp. depends on the ability of the inclusion to inhibit fusion with some compartments (for example, with lysosomes) while promoting fusion with others (for example, with nutrient-rich exocytic vesicles). Chlamydia spp. achieve selective fusion by recruiting specific members of at least three families of fusion regulators (FIG. 2b): RAB GTPases and their effectors, phosphoinositide lipid kinases and SNARE proteins.

RAB GTPases are master regulators of vesicle fusion and particular RABs are recruited to inclusions, some of them in a species-specific manner53. RAB1, RAB4, RAB11 and RAB14 were recruited to all of the species tested, whereas RAB6 was recruited only to C. trachomatis and RAB10 was recruited only to C. pneumoniae. RAB4 and RAB11 mediate the interactions of the inclusion with the transferrin slow-recycling pathway to acquire iron7 and may also contribute to transport along microtubules53. RAB6, RAB11 and RAB14 facilitate lipid acquisition from the Golgi apparatus53, whereas RAB39 participates in the delivery of lipids from multivesicular bodies54. The recruitment of RAB proteins is probably driven by species-specific Inc–RAB interactions. CT229 from C. trachomatis binds to RAB4, whereas Cpn0585 from C. pneumoniae binds to RAB1, RAB10 and RAB11 (REF. 53). The RAB11 effector, RAB11 family-interacting protein 2 (RAB11FIP2), also localizes to the inclusion and, together with RAB11, promotes the recruitment of RAB14 (REF. 55). Bicaudal-D homologue 1 (BICD1), a RAB6-interacting protein, is recruited to the inclusions of C. trachomatis L2 independently of RAB6, which reveals direct serovar-specific interactions53. Although the role of BICD1 is unclear, it may also contribute to transport to the MTOC, as this RAB effector family has been reported to link cargo to dynein56. RABs also promote vesicle fusion by recruiting lipid kinases, such as the inositol polyphosphate 5-phosphatase OCRL1 (also known as Lowe oculocerebrorenal syndrome protein), a Golgi-localized enzyme that produces the Golgi-specific lipid phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate (PI4P)53. Another enzyme that produces PI4P, phosphatidylinositol-4-kinase type IIα (PI4KIIα), is also recruited to the inclusion. The enrichment of PI4P might disguise the inclusion as a specialized compartment of the Golgi apparatus57.

In addition, Chlamydia spp. control vesicle fusion by interacting with SNARE proteins (FIG. 2b). These include the trans-Golgi SNARE proteins syntaxin 6 (STX6)58,59 and STX10 (REF. 60), vesicle-associated membrane protein 4 (VAMP4), a STX6 binding partner61, and GS15 (also known as BET1L)62, which regulates the acquisition of nutrients from the Golgi exocytic pathway. The recruitment of STX6 requires a Golgi-targeting signal (YGRL) and VAMP4 (REFS 59,61). In an example of molecular mimicry, at least three Incs contain SNARE-like motifs (IncA (also known as CT119), InaC (also known as CT813) and inclusion protein acting on microtubules (IPAM; also known as CT223)), which act as inhibitory SNARE proteins to limit fusion with compartments that contain VAMP3, VAMP7 or VAMP8 (REFS 49,63,64). In addition, the dimerization of SNARE-like domains facilitates homotypic fusion63–65. Although the function of homotypic fusion is unclear, naturally occurring non-fusogenic strains of C. trachomatis produce fewer infectious progeny and milder infections66.

Finally, C. trachomatis recruits members of the sorting nexin (SNX) family67,68, which are involved in trafficking from the endosome to the Golgi apparatus69. The recruitment of SNX5 and SNX6 is mediated by a direct interaction with IncE (also known as CT116)67 and may consequently disrupt this host trafficking pathway to promote bacterial growth.

Nutrient acquisition

Chlamydiae scavenge nutrients from various sources, for example, from the lysosomal-mediated degradation of proteins7, using various transporters53,70. Although chlamydiae can synthesize common bacterial lipids, the membrane of C. trachomatis contains eukaryotic lipids, including phosphatidylcholine, phosphatidylinositol, sphingomyelin and cholesterol21. These lipids are required for replication, homotypic fusion, growth and stability of the inclusion membrane, reactivation from persistence, and reticulate body to elementary body re-differentiation21,71. As Chlamydia spp. lack the required biosynthetic enzymes8, they have evolved sophisticated mechanisms to acquire lipids21 that involve both vesicular and non-vesicular pathways (FIG. 2c). Sphingomyelin and cholesterol are acquired from the Golgi apparatus and multivesicular bodies7. Host proteins that are implicated in this vesicle-dependent acquisition include ARF GTPases57,72,73, the ARF guanine nucleotide exchange factor GBF1 (REFS 72,73), RAB GTPases (specifically, RAB6, RAB11, RAB14 and RAB39)53,54, RAB11FIP2 (REF. 55), VAMP4 (REF. 61), dynamin71 and FYN kinase21. Non-vesicular mechanisms involve lipid transporters, including the ceramide endoplasmic reticulum transport protein (CERT; also known as COL4α3BP)73,74, which directly binds to IncD (also known as CT115)74,75, and members of the high-density lipoprotein (HDL) biogenesis machinery, which deliver host phosphatidylcholine76. The acquisition of glycerophospholipids requires the activation of phospholipase A2 and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK; also known as ERK)21. Sphingomyelin synthase 2 (SMS2; also known as SGMS2) is recruited to the inclusion, where it probably converts ceramide to sphingomyelin73. C. trachomatis also scavenges saturated fatty acids for de novo membrane synthesis77 and can produce a unique phospholipid species through its own fatty acid and phospholipid biosynthetic machinery78. In fact, bacterial type II fatty acid synthesis is essential for the proliferation of chlamydiae79.

Golgi fragmentation

During the mid-cycle stages of infection with C. trachomatis, the Golgi apparatus is fragmented into mini-stacks that surround the inclusion, which is thought to increase the delivery of lipids80. Several host proteins have been implicated in this process, including RAB6 and RAB11, ARF GTPases, dynamin and inflammatory caspases49,71,81. At least one bacterial factor, InaC, is required for the redistribution of the fragmented Golgi apparatus, possibly through the action of ARF GTPases and 14-3-3 proteins81. Fragmentation requires remodelling of stable detyrosinated microtubules, which may function as mechanical anchors for the Golgi stacks at the surface of the inclusion82. The evaluation of the role of dynamin revealed that fragmentation is dispensable for the growth of C. trachomatis and for lipid uptake71. Similarly, the trafficking of sphingolipids in a mutant that is deficient in InaC is normal, which indicates that the acquisition of lipids from the Golgi apparatus does not require fragmentation81. Additional studies will be required to establish the role of Golgi fragmentation.

Interactions of the inclusion with other organelles

Chlamydia spp. establish close contact with numerous other organelles (FIG. 2b). Although many organelles and markers have been visualized inside the inclusion, some of these observations may have been exaggerated by fixation-induced translocation83. Lipid droplets49 and peroxisomes84 translocate into the lumen of the C. trachomatis inclusion and are a possible source of triacylglycerides and metabolic enzymes, respectively. Indeed, proteomic analysis of cells infected with C. trachomatis revealed an increase in lipid droplet content and an enrichment of proteins that are involved in lipid metabolism and biosynthesis, including long-chain-fatty-acid-CoA ligase 3 (ACSL3) and lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase 1 (LPCAT1)85. Interestingly, these proteins can also be found on, or in, the inclusion86. Some proteins that are associated with lipid droplets or peroxisomes may affect bacterial processes. For example, the human acyl-CoA carrier, acyl-CoA-binding domain-containing protein 6 (ACBD6), modulates the bacterial acyltransferase activity of CT775 in C. trachomatis and the formation of phophatidylcholine86,87. Whereas the mechanism of peroxisome uptake is unclear, the capture of lipid droplets may involve the chlamydial proteins Lda1, Lda3, Cap1 (also known as CT529) and CT618, as these proteins associate with lipid droplets when ectopically expressed in host cells49,85.

Mitochondria closely associate with the inclusion, and depletion of the translocase of the inner membrane–translocase of the outer membrane (TIM–TOM) complex, which imports mitochondrial proteins, disrupts infection with C. caviae and C. trachomatis49,71. The consequence of this interaction is unclear; however, it is possible that Chlamydia spp. acquire energy metabolites or dampen pro-apoptotic signals.

Finally, the inclusion membrane establishes close contact with the smooth endoplasmic reticulum88. These contact sites are enriched in host proteins that are usually found at endoplasmic reticulum–Golgi contact sites (CERT and its binding partners, and vesicle-associated membrane proteins (VAPs))73,74 and at endoplasmic reticulum–plasma membrane contact sites (the calcium sensor stromal interaction molecule 1 (STIM1))89, and at least one bacterial protein, IncD in C. trachomatis74. This close contact may facilitate lipid transport73,74 and the construction of signalling platforms89. Membrane contact sites participate in stimulator of interferon genes (STING)-dependent pathogen sensing90 and could also modulate the endoplasmic reticulum stress response91,92. In addition, the inclusion is also juxtaposed to the rough endoplasmic reticulum, forming a `pathogen synapse' (REF. 93). T3SS effectors may be specifically injected into the rough endoplasmic reticulum and/or the rough endoplasmic reticulum may help fold T3SS effectors40.

Stabilizing the inclusion

The inclusion membrane seems to be very fragile, as attempts to purify inclusions were only recently successful68. Consistent with this notion, the growing inclusion becomes encased in F-actin and intermediate filaments that form a dynamic scaffold, which provides structural stability and limits the access of bacterial products to the host cytosol7,49. The recruitment and assembly of F-actin involves RHO-family GTPases49, septins94, EGFR signalling95 and at least one bacterial effector, InaC81. Microtubules are also actively reorganized around the inclusion by IPAM in C. trachomatis, which hijacks a centrosome protein, the centrosomal protein of 170 kDa (CEP170)96. This interaction initiates the organization of microtubules at the inclusion surface, which leads to the formation of a microtubule superstructure that is necessary for preserving membrane integrity96,49.

Exiting the host cell

The release of elementary bodies involves two mutually exclusive mechanisms: host cell lysis or the extrusion of the inclusion, which is a process that resembles exocytosis97 (FIG. 1). Lytic exit results in the death of the host cell and involves the permeabilization of the inclusion membrane, followed by permeabilization of the nuclear membrane, and lastly calcium-dependent lysis of the plasma membrane97. Live-cell imaging of a mutant that is deficient in a T2SS effector, Chlamydia protease-like activity factor (CPAF; also known as CT858), suggests that CPAF may have roles in dismantling the host cell and preparing elementary bodies for exit98. This report inferred that cytosolic CPAF was active only following lysis of the inclusion98, whereas other data suggest that the translocation of CPAF to the cytosol occurs before lysis and correlates with CPAF activity99. Further research is required to resolve when this T2SS effector reaches the cytosol of host cells.

By contrast, the extrusion pathway leaves the host cell intact and involves membrane pinching followed by expulsion of the inclusion. This process requires actin polymerization, the RHOA GTPase, neural Wiskott–Aldrich Syndrome protein (N-WASP), myosin II97 and components of the myosin phosphatase pathway, such as myosin phosphatase-targeting subunit 1 (MYPT1; also known as PPP1R12A), which binds to the early transcribed Inc effector CT228 in C. trachomatis100. Some septin family members (septin 2, septin 9, septin 11 and possibly septin 7) have been implicated in egress of the inclusion, possibly through the recruitment or stabilization of F-actin94. In fact, the recruitment of actin may be required for the extrusion of the inclusion101. Extrusion prevents the release of inflammatory contents and protects elementary bodies from host immunity, and it could also contribute to persistence, as some bacteria remain in the host cell. To prevent re-infection, C. trachomatis induces the surface shedding of glycoprotein 96, resulting in the loss of PDI, which is involved in binding and invasions102.

Modifying the host response

Controlling host cell survival and death

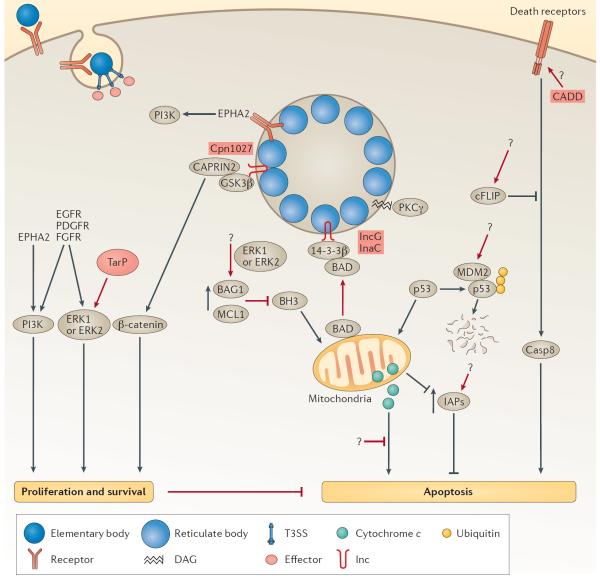

Correctly timed cell death is important for intracellular pathogens, as premature host cell death can limit replication. Chlamydia spp. activate pro-survival pathways and inhibit apoptotic pathways7 (FIG. 3). At least three Chlamydia spp. bind to RTKs that in turn activate MEK–ERK and phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) survival pathways: MEK–ERK signalling is activated through the interaction of C. trachomatis and C. muridarum with FGFR35 or through the binding of Pmp21 from C. pneumoniae to EGFR33. C. trachomatis also binds to EPHA2, which activates the PI3K pathway. These receptors are internalized with elementary bodies and, in the case of EPHA2, continue eliciting long-lasting survival signals, which are required for bacterial replication36. The upregulation of ERK also increases the level of EPHA2, which results in the activation of a feed-forward loop that is involved in host survival36. Finally, the Inc Cpn1027 from C. pneumoniae binds to members of the β-catenin–WNT pathway, cytoplasmic activation/proliferation-associated protein 2 (CAPRIN2) and glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β)103, which may enable β-catenin to activate the transcription of pro-survival genes.

Figure 3. Modulation of host cell survival and death.

Chlamydial infection promotes host cell proliferation and survival through the activation of phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) and mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase (MAPKK, also known as MEK)–mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK, also known as ERK) signalling cascades by binding to receptor tyrosine kinases or through the secretion of the early effector translocated actin-recruiting phosphoprotein (TarP). Chlamydia pneumoniae sequesters cytoplasmic activation/proliferation-associated protein 2 (CAPRIN2) and glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β), members of the β-catenin destruction complex, to the inclusion membrane possibly through their interaction with Cpn1027, which leads to increased stabilization of β-catenin and transcriptional activation of survival genes by β-catenin. Infected host cells are resistant to various apoptotic stimuli and apoptosis is blocked both upstream and downstream of the permeabilization of the outer membrane of mitochondria by numerous mechanisms. The upregulation of the anti-apoptotic proteins BAG family molecular chaperone regulator 1 (BAG1) and myeloid leukaemia cell differentiation protein 1 (MCL1) inhibits the ability of BH3-only proteins to destabilize the mitochondrial membrane. The BH3-only protein BCL-2-associated agonist of cell death (BAD) is also sequestered at the inclusion membrane by binding to the host protein 14-3-3β. The degradation of p53 by MDM2-mediated ubiquitylation and sequestration of protein kinase Cγ (PKCγ) also prevents the depolarization of the mitochondrial membrane. Downstream of the release of cytochrome c, Chlamydia spp. are still able to prevent apoptosis through unknown mechanisms. Infection also leads to the upregulation of inhibitors of apoptosis (IAPs), which contributes to the anti-apoptotic phenotype. The chlamydial protein CADD is implicated in the modulation of apoptosis by binding to the death domains of tumour necrosis factor (TNF) family receptors. C. trachomatis can block the activation of caspase 8 through the regulator cellular FLICE-like inhibitory protein (cFLIP) by an unknown mechanism. The text in the red boxes denotes the individual steps in which Chlamydia spp. are proposed to modulate host cell function and the bacterial effector that is involved, if it is known. Casp8, caspase 8; DAG, diacylglycerol; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; EPHA2, ephrin receptor A2; ERK, extracellular signal-regulated kinase; FGFR, fibroblast growth factor receptor; Inc, inclusion membrane protein; PDGFR, platelet derived growth factor receptor.

Cells that are infected with Chlamydia spp. show resistance to the stimuli of intrinsic and extrinsic apoptosis104 (FIG. 3). Resistance to apoptosis is cell-autonomous and requires bacterial protein synthesis104. Chlamydia spp. can block intrinsic apoptosis through numerous mechanisms including the MDM2-mediated ubiquitylation and proteasomal degradation of the tumour suppressor p53 (REFS 105,106), the sequestration of pro-apoptotic protein kinase Cδ (PKCδ) or BCL-2-associated agonist of cell death (BAD) to the inclusion membrane through diacylglcerol or 14-3-3β-binding Incs, respectively49,81, and the upregulation or stabilization of anti-apoptotic proteins including BAG family molecular chaperone regulator 1 (BAG1), myeloid leukaemia cell differentiation protein 1 (MCL1) or cIAP2 (also known as BIRC3)7,107. C. trachomatis inhibits extrinsic apoptosis by blocking the activation of caspase 8 through the master regulator cellular FLICE-like inhibitory protein (cFLIP; also known as caspase 8-inhibitory protein)108. Proteomic analysis of intact C. trachomatis inclusions68 and Inc binding partners67 reveals additional host proteins and effectors that may regulate host cell survival.

Modulating the host cell cycle

Studies using immortalized cell lines reveal that infection with Chlamydia spp. modulates host progression through the cell cycle using several mechanisms49. Although these studies provide important insights, their physiological relevance should be viewed with caution as Chlamydia spp. replicate in terminally differentiated non-cycling cells in vivo.

Cell lines that are infected with C. trachomatis progress slower through the cell cycle, which was originally attributed to the degradation of cyclin B1; however, the observed degradation was probably an artefact of sample preparation109. The early expressed cytotoxin CT166 in C. trachomatis has also been implicated in slowing the progression of the cell cycle, as ectopic expression of CT166 delays G1-phase to S-phase transition by inhibiting MEK–ERK and PI3K signalling110. The mid-cycle effector CT847 in C. trachomatis interacts with host GRB2-related adapter protein 2 (GRAP2) and GRAP2 and cyclin-D-interacting protein (GCIP; also known as CCNDBP1); however, whether this interaction regulates progression through the cell cycle during infection is unclear49. Chlamydia spp. induce early mitotic exit by bypassing the spindle assembly checkpoint111. C. pneumoniae may mediate the arrest of the cell cycle through the T3SS effector, CopN, which has been reported to bind to microtubules and perturb their assembly in vitro; however, whether this occurs during infection is unclear112,113. It is likely that Chlamydia spp. finely tune cell cycle progression to maximize nutrient acquisition at specific stages of development114.

C. trachomatis disrupts both centrosome duplication and clustering, but through independent mechanisms. CPAF is required for the induction of centrosome amplification, potentially through the degradation of one or more proteins that control centrosome duplication111. C. trachomatis also prevents centrosome clustering during mitosis in a CPAF-independent manner, presumably through the Inc-mediated tethering of centrosomes to the inclusion51,111,115,116. The cumulative effect of centro some amplification, early mitotic exit and errors in centrosome-positioning, halts cytokinesis, which results in multinucleated cells111,114. Multinucleation increases the contents of the Golgi apparatus, which enables Chlamydia spp. to easily acquire Golgi-derived lipids114. Other effectors that are implicated in multinucleation include IPAM, CT224, CT225 and CT166, as the ectopic expression of these proteins in uninfected cells blocks cytokinesis49,110, although their mechanism of action is unclear. In the case of IPAM, it will be interesting to determine whether the regulation of cytokinesis is mediated through binding to VAMPs and/or CEP170 and whether these observations represent three independent functions of IPAM.

Although infection induces double-strand breaks in the host DNA, chlamydiae dampen the host DNA-damage response117. C. trachomatis inhibits the binding of the DNA-damage response proteins MRE11, ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM) and p53-binding protein 1 (53BP1) to double-strand breaks117, and blocks the arrest of the cell cycle through the degradation of p53 (REF. 106). By perturbing cell survival pathways, the regulation of the cell cycle, the repair of DNA damage, and centrosome duplication and positioning, chlamydiae favour malignant transformation. As the loss of the tumour suppressor p53 can produce extra centrosomes118, it will be interesting to determine whether the degradation of p53 is driving this process. Furthermore, Chlamydia spp. induce anchorage- independent growth in mouse fibroblasts, a phenotype that correlates closely with tumorigenicity119. These phenotypes seem to be relevant in vivo as infection of the mouse cervix increases cervical cell proliferation, signs of cervical dysplasia and chromosome abnormalities119. Even eukaryotic cells that are cleared of Chlamydia spp. show increased resistance to apoptosis and decreased responsiveness to p53 signalling120, which may increase sensitivity to malignant transformation.

Immune recognition and subversion of immunity

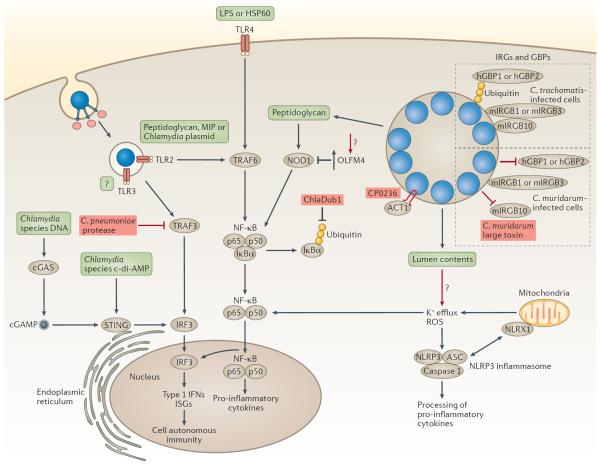

Epithelial cells recognize chlamydial antigens through cell surface receptors, endosomal receptors and cytosolic innate immune sensors (FIG. 4). Activation of these receptors triggers the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, which recruit inflammatory cells7,121. However, this inflammatory response, which is required for bacterial clearance, is also responsible for immunopathology, such as tissue damage and scarring6.

Figure 4. Modulation of the innate immune response.

The recognition of chlamydial infection by pattern-recognition receptors leads to cell-autonomous immunity and the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Chlamydial antigens (green boxes) can be recognized by cell surface, endosomal or cytosolic pathogen sensors. Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) recognizes lipopolysaccharide (LPS) or the 60 kDa heat shock protein (HSP60), whereas TLR2 recognizes peptidoglycan, macrophage inhibitory protein (MIP) and/or plasmid-regulated ligands. Both TLR2 and TLR4 signalling require the adaptors myeloid differentiation primary response protein 88 (MYD88) and tumour necrosis factor (TNF) receptor-associated factor 6 (TRAF6), and lead to the nuclear translocation of nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) and the induction of innate immune responses. The activation of the cytosolic sensor STING (stimulator of interferon genes) by the bacterial second messenger cyclic di-AMP (c-di-AMP) or through the host secondary messenger cyclic GMP–AMP (cGAMP) leads to the phosphorylation of interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3), nuclear translocation and induction of type I interferon (IFN) genes (encoding IFNα and IFNβ) and IFN-stimulated genes (ISG). The peptidoglycan sensor nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-containing 1 (NOD1) is activated during chlamydial infection and induces the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines through NF-κB signalling. The activation of the NOD-, LRR- and pyrin domain-containing 3 (NLRP3)–apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a CARD (ASC) inflammasome (NLRP3–ASC inflammasome) requires reactive oxygen species (ROS) and K+ efflux. The production of ROS is amplified by the mitochondrial NOD-like receptor X1 (NLRX1), which augments the production of ROS, creating a feed-forward loop. Some innate immune molecules that recognize vacuolar pathogens, such as human guanylate-binding protein 1 (hGBP1) and hGBP2, mouse immunity-related GTPase family M protein 1 (mIRGM1) and mIRGM3, and mouse IRGB10 (mIRGB10), localize to Chlamydia trachomatis inclusions and promote bacterial clearance. Chlamydia muridarum prevents the recognition of inclusions by these receptors. Chlamydial virulence factors (depicted in red) can disrupt or augment the innate immune response. During infection with Chlamydia pneumoniae, an unknown protease cleaves TRAF3, which blocks the phosphorylation of IRF3 and the production of type 1 IFNs. The deubiquitinase Dub1 removes ubiquitin from NF-κB inhibitor-α (IκBα), which stabilizes the p65–p50–IκBα complex and prevents the nuclear translocation of NF-κB. The C. pneumonia protein CP0236 sequesters NF-κB activator 1 (ACT1) to the inclusion membrane. Chlamydial infection also leads to the upregulation of olfactomedin 4 (OLFM4), which potentially blocks NOD1-mediated signalling. cGAS, cGAMP synthase.

On binding, chlamydiae activate the Toll-like receptors (TLRs) — TLR2, TLR3 and TLR4 — to varying degrees, depending on the species and the infection model6,7,121,122. TLR2 can recognize peptidoglycan, although other ligands, such as macrophage inhibitory protein (MIP) or plasmid-regulated ligands, have been suggested121. TLR2 and the downstream TLR adaptor myeloid differentiation primary response protein 88 (MYD88) have been reported to localize on, and potentially signal from, the inclusion, and mouse models of infection with C. pneumoniae and C. trachomatis suggest key roles for TLR2 and MYD88 in bacterial recognition and clearance121,123. The recognition of chlamydial LPS and/or 60 kDa heat shock protein (HSP60) by TLR4 may also contribute to bacterial clearance, but the relative importance of TLR4 compared with TLR2 remains to be determined121,123. Chlamydial infection is also detected by the intracellular nucleotide sensors cyclic GMP–AMP (cGAMP) synthase (cGAS) and STING124. On binding DNA, cGAS catalyses the production of the cyclic di-nucleotide second messenger cGAMP, which activates STING, inducing the expression of type I interferons (IFNs)125. Chlamydia spp. also synthesize the secondary messenger cyclic di-AMP, which, on release into the cytoplasm of the host cell, activates STING independently of cGAS, and may contribute to the production of type I IFNs90. The intracellular peptidoglycan-binding molecule nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-containing 1 (NOD1) is also activated in response to infection with C. pneumoniae, C. trachomatis and C. muridarum, which reveals that chlamydial peptidoglycan gains access to the host cytosol (BOX 3). During chlamydial infection, caspase 1 is activated through the NOD-, LRR- and pyrin domain-containing 3 (NLRP3)-apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a CARD (ASC) inflammasome (NLRP3–ASC inflammasome)121. Activation of the NLRP3–ASC inflammasome requires K+ efflux and the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which is amplified through the mitochondrial NOD-like receptor X1 (NLRX1)126. Intriguingly, activation of the inflammasome promotes infection under some conditions121,127, maybe owing to an increase in lipid acquisition or utilization127. Finally, maintaining the integrity of the inclusion membrane is probably another mechanism used to prevent the cytosolic sensing of bacterial components121.

Box 3 | Solving the chlamydial peptidoglycan `anomaly'.

Peptidoglycan forms a lattice-like sheet that surrounds the cytoplasmic membrane of bacterial cells, where it has crucial functions in binary fission and in maintaining structural strength against osmotic pressure168. It is expected that chlamydiae, similarly to other Gram-negative pathogens, have peptidoglycan in their cell walls. Chlamydiae encode functional peptidoglycan biosynthetic enzymes, are sensitive to β-lactam antibiotics that target peptidoglycan biosynthesis, and activate the host cytosolic sensor of peptidoglycan — nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-containing 1 (NOD1)168. Despite these observations, peptidoglycan was not detectable using conventional methods; a dilemma that was termed the `chlamydial anomaly' (REF. 168). Furthermore, chlamydiae lack FtsZ8, which, together with peptidoglycan, coordinates cell division and cell shape in nearly all other bacterial species168. Therefore, chlamydiae must use alternative strategies to coordinately orchestrate peptidoglycan synthesis and cell division. Several new studies have helped to resolve these discrepancies. First, an intact peptidoglycan-containing sacculus was extracted from the ancestral Protochlamydiae, and was found to contain a novel peptidoglycan modification169. Second, using a new technique that is based on the incorporation of click-chemistry-modified d-amino acid probes, newly assembled peptidoglycan was visualized at the septum of dividing reticulate bodies in a ring-like structure, which indicated that peptidoglycan may have a role in cell division170. Third, MreB, an actin homologue, was found to localize at the septum in a manner that was dependent on peptidoglycan precursors and its conserved regulator RodZ (also known as CT009)171–173, where it is thought to functionally compensate for the lack of FtsZ. Fourth, muramyl peptides and larger muropeptide fragments in Chlamydia trachomatis were isolated from fractionated infected cell lysates using a NOD-activated reporter cell line as a sensitive read-out174. Mass spectrometry analysis of these peptides provided the first structural confirmation of chlamydial peptidoglycan and demonstrated that chlamydiae can carry out transpeptidation and transglycosylation reactions174. Fifth, the amidase A homologue (AmiA) in Chlamydia pneumoniae was shown to use lipid II, the peptidoglycan building block comprised of N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) and N-acetylmuramic acid (MurNAc)-pentapeptide, as a substrate175. AmiA is unusual in that it has dual enzymatic activity, functioning both as an amidase and as a penicillin-sensitive carboxypeptidase that is crucial for the complete biosynthesis of lipid II, the remodelling of peptidoglycan and for maintaining coordinated cell division175,176. Finally, C. pneumoniae and Waddlia chondrophila each encode a functional homologue of Escherichia coli NlpD, which localizes to the septum where it probably acts on peptide crosslinks175,176. Together, these studies provide strong evidence that chlamydiae express classical peptidoglycan, which is probably required for cell division.

Chlamydiae have evolved several mechanisms to manipulate immune responses, and under some conditions, prevent clearance. Chlamydial infection can mitigate the production of IFN or counteract downstream gene products that are involved in cell-autonomous immunity121. C. pneumoniae suppresses the production of IFNβ by degrading the signalling molecule tumour necrosis factor (TNF) receptor-associated factor 3 (TRAF3), possibly through the activity of a protease that is specific to C. pneumoniae128. C. pneumoniae also evades the production of nitric oxide (NO) by downregulating the transcription of inducible NO synthase (iNOS) through the induction of an alternative polyamine pathway129. C. trachomatis downregulates the expression of interferon- induced protein with tetratricopeptide repeats 1 (IFIT1) and IFIT2 through the T3SS effector TepP45. The production of IFNγ induces the expression of host indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO), which depletes host cells of tryptophan, thereby inhibiting the replication of Chlamydia strains that are tryptophan auxotrophs27. Genital serovars encode a tryptophan synthase that enables the synthesis of tryptophan from indole that is provided by the local microbiota, thus evading this host response. IFNγ also induces the expression of immunity-related GTPases (IRGs) or guanylate binding proteins (GBPs)49. These dynamin-like molecules aid in the recognition of the inclusion, directly damage the inclusion and/or modulate the fusion of the inclusion with lysosomes. Defining the role of IRGs and GBPs in chlamydial infection has been complex, as the anti-chlamydial effects of IFNγ are specific to the host, the cell-type and the Chlamydia spp. Mouse cells recognize C. trachomatis inclusions through the IFN-inducible GTPases IRGM1, IRGM3 and IRGB10, but the recruitment of IRGB10 to the inclusions is prevented by an unknown mechanism49. Human GBP1 and GBP2 recognize and localize to C. trachomatis inclusions and contribute to the effects of IFNγ, possibly through the recruitment of the autophagic machinery130. Recent studies suggest that the ubiquitylation of the C. trachomatis inclusion is important for the recruitment of GBPs131,132, which enable the rapid activation of the inflammasome in infected macrophages133. This process may be important for distinguishing between self-vacuoles and Chlamydia-containing vacuoles134.

Chlamydiae use various strategies to evade or dampen nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) transcription7,16. The T3SS effector ChlaDub1 (also known as CT868) deubiquitylates and stabilizes NF-κB inhibitor-α (IκBα) in the cytosol, whereas the C. pneumoniae Inc CP0236 binds to and sequesters NF-κB activator 1 (ACT1; also known as CIKS) to the inclusion membrane135, thereby blocking NF-κB signalling. Infection with C. trachomatis also upregulates olfactomedin 4 (OLFM4), a glycoprotein that may suppress the NOD1-mediated activation of NF-κB136. These redundant mechanisms highlight the importance of blocking NF-κB.

Alterations in the host cell transcriptome and proteome

Similar to other intracellular pathogens, Chlamydia spp. cause substantial changes in gene expression and protein production in the host, at the transcriptional, translational and post-translational levels. In addition to affecting transcriptional regulators, such as NF-κB121 (FIG. 4), Chlamydia spp. markedly alter histone post-translational modifications117, which can change the structure of chromatin and gene expression. The T3SS effector CT737 (also known as NUE) encodes a putative histone methyltransferase that associates with host chromatin during infection with C. trachomatis and may have a role in the observed global histone modification137. C. trachomatis also induces widespread changes in protein stability, and at least a subset of these altered proteins is required for replication138. Chlamydia spp. secrete T3SS effectors that modulate host ubiquitylation and protein stability, including the deubiquitinase Cpn0483 (also known as ChlaOTU) produced by C. pneumoniae139 and the deubiquitinases ChlaDub1 and ChlaDub2 (also known as CT867) produced by C. trachomatis140,141. Furthermore, Incs that are produced by C. trachomatis may interact with the host ubiquitylation machinery67, which reveals additional routes to target protein stability. Historically, CPAF was a strong candidate for reshaping the host proteome, as CPAF can cleave numerous and diverse substrates in vitro and its activity has been attributed to several phenotypes in vivo109,142. However, the interpretation of CPAF activity and its substrates is complicated by artefactual proteolysis during sample preparation109,143, which has triggered intense discussion142,144. Consistent with the results of Chen et al.109, a CPAF-null mutant reveals that this protease is not required for some of the phenotypes that were previously suggested, including Golgi fragmentation, the inhibition of NF-κB activation and resistance to apoptosis98,145. Future genetic studies will determine how Chlamydia spp. induce global changes in the host proteome in vivo and the role and physiologically relevant substrates of CPAF.

Conclusions and future directions

Understanding how Chlamydia spp. survive in the intracellular environment reveals the finely nuanced `arms race' between pathogens and their hosts. Despite its reduced genome size, this wily pathogen uses its arsenal of effectors to establish an intracellular niche and modulate the host immune response. New techniques in host and bacterial cell biology, proteomics and host genetics have provided vital insights into the molecular underpinnings of these events. Recent breakthroughs in chlamydial genetics146 (BOX 2) have opened the possibility of delineating gene functions in vivo, including the roles of specific bacterial adhesins and effectors, to test the current models of temporal gene expression, and to help resolve questions regarding the function of CPAF98,99,144. Further technological advances will eventually lead to efficient and versatile genome editing. Finally, recent improvements in cell culture147–149 and animal models3 will continue to increase our understanding of pathogenic processes, as these models more closely recapitulate the pathology of human genital tract infections, and will probably be useful in investigating the effects of clinically important co-infecting pathogens, such as HIV or herpes simplex virus. We are entering a new golden age in understanding the pathogenic mechanisms commandeered by this medically important and fascinating obligate intracellular pathogen.

Acknowledgements

The authors apologize to those colleagues in the field whose work could not be included owing to space constraints. The authors gratefully acknowledge financial support from the US National Institutes of Health (R01 AI073770, AI105561 and AI122747) to J.E., and from the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF)-Gladstone Institute for Virology and Immunology, and the Center for AIDS Research to C.E.

Glossary

- Biovars

Variants that differ physiologically and/or biochemically from other strains of a particular species.

- Serovar

A subdivision of a species or subspecies that is distinguished by a characteristic set of antigens.

- Type V secretion system (T5SS)

A system that exports autotransporters that are composed of a carboxy-terminal β-barrel translocator domain and an amino-terminal passenger domain that passes through the interior of the barrel to face the external environment.

- Type II secretion system (T2SS)

A system that exports proteins across the bacterial inner membrane through the general secretory (Sec) pathway and across the outer membrane through secretin. In chlamydiae, T2SS effectors are secreted into the inclusion lumen, but can access the host cytosol through outer membrane vesicles.

- Type III secretion system (T3SS)

A needle-like apparatus found in Gram-negative bacteria that delivers proteins, called effectors, across the inner and outer bacterial membranes and across eukaryotic membranes to the host membrane or the cytosol.

- Homotypic fusion

The fusion between cells or vesicles of the same type. For cells that are infected with some Chlamydia spp., several inclusions undergo fusion with each other to form one, or a few, larger inclusions.

- Sigma factors

Bacterial proteins that direct the binding of RNA polymerase to promoters, which enables the initiation of transcription.

- Response regulators

Subunits of bacterial two-component signal transduction pathways that regulate output in response to an environmental stimulus.

- Polymorphic membrane protein (PMP)

A member of a diverse group of surface-localized, immunodominant proteins that are secreted by the type V secretion system (T5SS) of Chlamydia spp.

- ADP ribosylation factor 6 (ARF6)

A member of the GTPase family of small GTPases that regulates vesicular transport, in which they function to recruit coat proteins that are necessary for the formation of vesicles.

- Dynactin

A multisubunit complex found in eukaryotic cells that binds to the motor protein dynein and aids in the microtubule-based transport of vesicles.

- SNARE proteins

Soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor (NSF) attachment protein receptor proteins). Soluble NSF attachment proteins are a large superfamily of proteins that mediate vesicle fusion by pairing with each other on adjacent membranes through SNARE domains.

- RAB GTPases

Small GTPases that localize to the cytosolic face of specific intracellular membranes, where they regulate intracellular trafficking and membrane fusion. Different RABs are specific for distinct subcellular compartments.

- Phosphoinositide lipid kinases

A family of enzymes that generates phosphorylated variants of phosphatidylinositols (secondary messengers), which are important for signalling and membrane remodelling. Organelles are, in part, identified by the specific lipid species that they contain.

- Multivesicular bodies (MVBs)

A specialized set of late endosomes that contains internal vesicles formed by the inward budding of the outer endosomal membrane. MVBs are involved in protein sorting and are rich in lipids, including sphingolipids and cholesterol.

- Dynamin

A large GTPase that is involved in the scission of newly formed vesicles from the cell surface, endosomes and the Golgi apparatus.

- Ceramide endoplasmic reticulum transport protein (CERT)

A cytosolic protein that mediates the non-vesicular transport of ceramide from the endoplasmic reticulum to the Golgi apparatus where it is converted to sphingomyelin.

- Type II fatty acid synthesis

A type of fatty acid synthesis in which the enzymes that catalyse each step in the synthesis pathway exist as distinct, individual proteins rather than as a multi-enzyme complex as in type I fatty acid synthesis.

- Caspases

A family of cysteine proteases that has essential roles in apoptosis, necrosis and inflammation.

- 14-3-3 proteins

A family of conserved regulatory molecules that usually binds to a phosphoserine or phosphothreonine residue found in functionally diverse signalling proteins in eukaryotic cells.

- Stimulator of interferon genes (STING)

A signalling molecule that recognizes cytosolic cyclic dinucleotides and activates the production of type I interferons.

- Endoplasmic reticulum stress response

A stress pathway that is activated by perturbations in protein folding, lipid and steroid biosynthesis, and intracellular calcium stores.

- Septins

A family of GTP-binding proteins that assembles into oligomeric complexes to form large filaments and rings that act as scaffolds and diffusion barriers

- Chlamydia protease-like activity factor (CPAF)

A type II secreted broad-spectrum protease produced by Chlamydia spp. that may have a role in cleaving host proteins on release into the host cell cytosol late in infection or extracellularly following the lysis of the host cell.

- BH3-only proteins

Members of the B cell lymphoma 2 (BCL-2) protein family, which are essential initiators of programmed cell death and are required for apoptosis that is induced by cytotoxic stimuli.

- β-catenin–WNT pathway

A eukaryotic signal transduction pathway that signals through the binding of the WNT protein ligand to a frizzled family cell surface receptor, which results in changes to gene transcription, cell polarity or intracellular calcium levels.

- Intrinsic and extrinsic apoptosis

A programmed form of cell death that involves the degradation of cellular constituents by caspases that are activated through either the intrinsic (mitochondria-mediated) or extrinsic (death receptor-mediated) apoptotic pathways.

- p53

A eukaryotic tumour suppressor that maintains genome integrity by activating DNA repair, arresting the cell cycle or initiating apoptosis.

- Cytokinesis

The physical process of cell division, which divides the cytoplasm of a parental cell into two daughter cells.

- Toll-like receptors (TLRs)

Transmembrane proteins that have a key role in the innate immune system by recognizing pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), which are structurally conserved molecules derived from microorganisms.

- Type I interferons (Type I IFNs)

A subgroup of interferon proteins produced as part of the innate immune response against intracellular pathogens.

- Nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-containing 1 (NOD1)

A cytosolic pattern-recognition receptor that recognizes bacterial peptidoglycan.

- NLRP3–ASC inflammasome

A multiprotein complex, consisting of caspase1, NOD-, LRR- and PYD domain-containing protein 3 (NLRP3) and apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a CARD (ASC), that processes the pro-inflammatory cytokines interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and IL-18 into their mature forms.

- Cell-autonomous immunity

The ability of a host cell to eliminate an invasive infectious agent, which relies on microbial proteins, specialized degradative compartments and programmed host cell death.

- Nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB)

A protein complex that is translocated from the cytosol to the nucleus and regulates DNA transcription, cytokine production and cell survival in response to harmful cellular stimuli.

Footnotes

Competing interests statement The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Bachmann NL, Polkinghorne A, Timms P. Chlamydia genomics: providing novel insights into chlamydial biology. Trends Microbiol. 2014;22:464–472. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2014.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R, editors. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 7th edn Vol. 2. Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rank RG. In: Intracellular Pathogens 1: Chlamydiales. Tan M, Bavoil PM, editors. Vol. 1. ASM Press; 2012. pp. 285–310. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malhotra M, Sood S, Mukherjee A, Muralidhar S, Bala M. Genital Chlamydia trachomatis: an update. Indian J. Med. Res. 2013;138:303–316. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Vrieze NH, de Vries HJ. Lymphogranuloma venereum among men who have sex with men. An epidemiological and clinical review. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 2014;12:697–704. doi: 10.1586/14787210.2014.901169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murthy AK, Arulanandam BP, Zhong G. In: Intracellular Pathogens 1: Chlamydiales. Tan M, Bavoil PM, editors. Vol. 1. ASM Press; 2012. pp. 311–333. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bastidas RJ, Elwell CA, Engel JN, Valdivia RH. Chlamydial intracellular survival strategies. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2013;3:a010256. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a010256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stephens RS, et al. Genome sequence of an obligate intracellular pathogen of humans: Chlamydia trachomatis. Science. 1998;282:754–759. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5389.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Myers GSA, Crabtree J, Creasy HH. In: Intracellular Pathogens 1: Chlamydiales. Tan M, Bavoil PM, editors. Vol. 1. ASM press; 2012. pp. 27–50. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Betts-Hampikian HJ, Fields KA. The chlamydial type III secretion mechanism: revealing cracks in a tough nut. Front. Microbiol. 2010;1:114. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2010.00114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fields KA. In: Intracellular Pathogens 1: Chlamydiales. Tan M, Bavoil PM, editors. Vol. 1. ASM press; 2012. pp. 192–216. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lei L, et al. Reduced live organism recovery and lack of hydrosalpinx in mice infected with plasmid-free Chlamydia muridarum. Infect. Immun. 2014;82:983–992. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01543-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nelson DE. In: Intracellular Pathogens 1: Chlamydiales. Tan M, Bavoil PM, editors. Vol. 1. ASM Press; 2012. pp. 74–96. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Omsland A, Sixt BS, Horn M, Hackstadt T. Chlamydial metabolism revisited: interspecies metabolic variability and developmental stage-specific physiologic activities. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2014;38:779–801. doi: 10.1111/1574-6976.12059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saka HA, et al. Quantitative proteomics reveals metabolic and pathogenic properties of Chlamydia trachomatis developmental forms. Mol. Microbiol. 2011;82:1185–1203. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07877.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hackstadt T. In: Intracellular Pathogens 1: Chlamydiales. Tan M, Bavoil PM, editors. Vol. 1. ASM press; 2012. pp. 126–148. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hegemann JH, Moelleken K. In: Intracellular Pathogens 1: Chlamydiales. Tan M, Bavoil PM, editors. Vol. 1. ASM press; 2012. pp. 97–125. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mehlitz A, Rudel T. Modulation of host signaling and cellular responses by Chlamydia. Cell Commun. Signal. 2013;11:90. doi: 10.1186/1478-811X-11-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tan M. In: Intracellular Pathogens 1: Chlamydiales. Tan M, Bavoil PM, editors. Vol. 1. ASM press; 2012. pp. 149–169. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moore ER, Ouellette SP. Reconceptualizing the chlamydial inclusion as a pathogen-specified parasitic organelle: an expanded role for Inc proteins. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2014;4:157. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2014.00157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elwell CA, Engel JN. Lipid acquisition by intracellular Chlamydiae. Cell. Microbiol. 2012;14:1010–1018. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2012.01794.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barta ML, et al. Atypical response regulator ChxR from Chlamydia trachomatis is structurally poised for DNA binding. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e91760. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0091760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]