Abstract

Exendin-4 is an agonist of the glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor (GLP-1R) and is used in the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Since human GLP-1R has been identified in various cells besides pancreatic cells, exendin-4 is expected to exert extrapancreatic actions. It has also been suggested to affect gene expression through epigenetic regulation, such as DNA methylation and/or histone modifications. Furthermore, the expression of extracellular-superoxide dismutase (EC-SOD), a major SOD isozyme that is crucially involved in redox homeostasis, is regulated by epigenetic factors. In the present study, we demonstrated that exendin-4 induced the demethylation of DNA in A549 cells, which, in turn, affected the expression of EC-SOD. Our results showed that the treatment with exendin-4 up-regulated the expression of EC-SOD through GLP-1R and demethylated some methyl-CpG sites (methylated cytosine at 5'-CG-3') in the EC-SOD gene. Moreover, the treatment with exendin-4 inactivated DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs), but did not change their expression levels. In conclusion, the results of the present study demonstrated for the first time that exendin-4 regulated the expression of EC-SOD by reducing the activity of DNMTs and demethylation of DNA within the EC-SOD promoter region in A549 cells.

Keywords: exendin-4, extracellular-superoxide dismutase, epigenetics, DNA demethylation

Introduction

Superoxide dismutase (SOD) is an antioxidative enzyme that protects cells against oxidative stress induced by the excessive production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), and a SOD deficiency has been shown to increase the risk of developing various diseases, such as type 2 diabetes, atherosclerosis, and asthma.(1–3) Extracellular-SOD (EC-SOD), one of the three SOD isozymes in mammals, is secreted into the extracellular space and widely distributed in tissues.(4) EC-SOD is highly expressed in the lung and kidney, and is localized to specific cells in these tissues.(5–7) However, it currently remains unclear why the expression of EC-SOD is different among cells and/or tissues. EC-SOD was previously reported to be expressed at very low levels in the human lung adenocarcinoma epithelial cell line A549, but at very high levels in normal airway epithelial cells.(8) EC-SOD modulates oxidative stress in the tumor microenvironment and inhibits tumor growth.(9) Therefore, pharmacological therapy that induces the expression of EC-SOD may represent a useful therapeutic approach for cancer chemotherapy.

Epigenetics have been defined as mitotically heritable changes in gene expression that do not change the DNA sequence, and include DNA methylation and histone modifications.(10) DNA methylation, occurring at the 5' carbon of cytosine within CpG, plays a pivotal role in tissue-specific gene regulation.(11) Regions with a high density of CpG sites are referred to as CpG islands, and are mostly unmethylated. However, gene expression is suppressed by the methylation of some CpG islands, and DNA methylation is involved in the development, differentiation, or canceration of their cells.(12–14) The methylation of DNA is initiated by the transmethylation of S-adenosylmethionine (SAM), a methyl group donor, which is catalyzed by DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs), including DNMT1, DNMT3A, and DNMT3B in mammals.(15,16)

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) is an incretin hormone secreted by L-cells located in the distal small intestine. The plasma concentration of GLP-1 rapidly increases within a few minutes of food intake. GLP-1 stimulates the secretion of insulin from pancreatic β-cells, but suppresses that of glucagon from α-cells by binding to the GLP-1 receptors (GLP-1R) on these cells, thereby lowering blood glucose concentrations. However, the biological activity of GLP-1 is tightly regulated because once it is secreted into plasma, it is rapidly cleaved by dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP-4). GLP-1R agonists that are resistant to DPP-4 cleavage have recently been developed and generally enable the strong and steady activation of GLP-1R signaling. Exendin-4 a GLP-1 receptor agonist, was initially discovered in the saliva of the Gila monster, Heloderma suspectum, and shares 53% sequence homology with GLP-1.(17,18) It was approved as a treatment for type 2 diabetes, called “exenatide”, in Japan in 2010. GLP-1 and its receptor agonists have been shown to directly exert extrapancreatic actions because GLP-1R is also expressed in the heart, intestines, kidney, and brain.(19)

Previous studies reported that EC-SOD activity was decreased in type 2 diabetes.(20–22) Moreover, EC-SOD expression is known to be suppressed by cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-α, which plays a role in diabetes. On the other hand, the enhanced expression of EC-SOD has been shown to mitigate streptozotocin-induced diabetic cardiomyopathy by attenuating oxidative stress.(23) As described above, EC-SOD is expressed at very low levels in A549 cells. DNA methylation has been implicated in the low expression of EC-SOD because DNA methylation within the EC-SOD promoter region inhibits binding of the Sp1/3 transcriptional factor to the EC-SOD promoter.(24,25) Exendin-4 was previously shown to epigenetically regulate (DNA methylation and histone modification) gene expression.(26) This finding prompted us to elucidate the contribution of exendin-4 to the induction of EC-SOD expression in A549 cells because GLP-1R is expressed in this cells, whereas EC-SOD expression is very low. In the present study, we investigated whether exendin-4 regulated the expression of EC-SOD via an epigenetic mechanism.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture

A549 cells, a human lung adenocarcinoma epithelial cell line, were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified eagle medium (DMEM) containing 10% (v/v) fetal calf serum (FCS), 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 µg/ml streptomycin. Cells were maintained at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator. The culture medium was replaced every 2 days.

Real-time reverse transcriptional-polymerase chain reaction (real-time RT-PCR) analysis

A549 cells (seeded at 4.5 × 105 cells/ml in 60-mm culture dishes) were cultured overnight and treated with exendin-4 (AnaSpec, Fremont, CA), 5-azacytidine (Aza, Wako Pure Chem. Ind., Ltd., Osaka, Japan) or exendin-(9-39) (GenScript, Piscataway, NJ). After the treatment for 24 h, the cells were washed with cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and total RNA was extracted from cells with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The preparation of cDNA was performed by the method described in our previous study.(27) Real-time RT-PCR was carried out using ThunderbirdTM SYBR qPCR Mix (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The EC-SOD primers were used QuantiTect® Primer Assay Hs_SOD3_2_SG (Qiagen, Chatsworth, CA). The other primer sequences used in real time RT-PCR were as follows: Cu,Zn-SOD, sense 5'-GCG ACG AAG GCC GTG TGC GTG-3'; antisense 5'-TGT GCG GCC AAT GAT GCA ATG-3': Mn-SOD, sense 5'-CGA CCT GCC CTA CGA CTA CGG-3'; antisense 5'-CAA GCC AAC CCC AAC CTG AGC-3': DNMT 1, sense 5'-ACC GCT TCT ACT TCC TCG AGG CCT A-3'; antisense 5'-GTT GCA GTC CTC TGT GAA CAC TGT GG-3': DNMT 3A, sense 5'-CAC ACA GAA GCA TAT CCA GGA GTG-3'; antisense 5'-AGT GGA CTG GGA AAC CAA ATA CCC-3': DNMT 3B, sense 5'-AAT GTG AAT CCA GCC AGG AAA GGC-3'; antisense 5'-ACT GGA TTA CAC TCC AGG AAC CGT-3': 18S rRNA, sense 5'-CGG CTA CCA CAT CCA AGG AA-3'; antisense 5'-GCT GGA ATT ACC GCG GCT-3'. mRNA levels were normalized to those of 18S rRNA mRNA in each sample.

McrBC digestion of genomic DNA

Genomic DNA was isolated from A549 cells using a Puregene Core kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Genomic DNA was cleaved with EcoRI at 37°C for 2 h followed by phenol-chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation. Cleaved genomic DNA (500 ng) was further cleaved with McrBC (New England BioLabs, Beverly, MA), an endonuclease that cleaves DNA containing methylcytosine, in a final reaction volume of 10 µl at 37°C for 1 h followed by an incubation at 65°C for 20 min. The cleaved genomic DNA was diluted 10-fold with water, and 2 µl of the DNA was used as a template for the real-time RT-PCR analysis. The primer pairs were as follows: sense 1 (–1,208 bp from transcription start site) 5'-GCT GGT AAC TAA GTC ACC CA-3' and sense 2 (–278 bp) 5'-CTG AAG GTC ACT GGC TAC AA-3' ; antisense 1 (–764 bp) 5'-TGT TGT CTG GGA GAA CTA GG-3' and antisense 2 (+51 bp) 5'-TAG CAC CCA CCT TTC CAG C-3'. Real-time RT-PCR was carried out using ThunderbirdTM SYBR qPCR Mix according to the manufacturer’s protocols.

Methylation-specific PCR (MSP) analysis

The bisulfite modification of genomic DNA was carried out using an EZ DNA Methylation-Gold kit (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. An aliquot of bisulfate-treated DNA (500 ng) was subjected to MSP amplification. The primer sequences used in MSP of the EC-SOD promoter (MSP1) and coding region (MSP2) were designed for the sodium bisulfate-modified template using MethPrimer software, and these MSP primer pairs were as follows: MSP1-methylated (M) sense 5'-TGG AGG CGA AGT AAT TTT ATA ATT C-3', MSP1-M antisense 5'-CCT AAA ACC TAA ACT ATT AAC GCG A-3', MSP1-unmethylated (U) sense 5'-GGA GGT GAA GTA ATT TTA TAA TTT GG-3', MSP1-U antisense 5'-CCT AAA ACC TAA ACT ATT AAC ACA AA-3', MSP2-M sense 5'-TCG AGA TAT GTA CGT TAA GGT TAC G-3', MSP2-M antisense 5'-ACT AAA ACT ATT CGA CTC GAT CGA A-3', MSP2-U sense 5'-TGA GAT ATG TAT GTT AAG GTT ATG G-3', MSP2-U antisense 5'-ACT AAA ACT ATT CAA CTC AAT CAA A-3'. After amplification, aliquots of the PCR mixtures were separated on a 2% (w/v) agarose gel and stained with ethidium bromide. These were visualized using FLA5100 (Takara, Otsu, Japan).

Bisulfite sequencing of the EC-SOD promoter region

Bisulfite sequencing to analyze the methylation pattern of CpG sites within the EC-SOD promoter was carried out as described previously(24) with minor modifications. An aliquot of bisulfite-treated genomic DNA (500 ng) was subjected to PCR amplification. The primer sequences used in bisulfate sequencing to amplify the promoter region of EC-SOD were designed using MethPrimer software, and these primers were as follows: sense 5'-TTT TTT GTT GTG TGT TGA AGG TTA T-3', antisense 5'-AAC TCC TCC AAA AAA ACT TTC TCT C-3'. The PCR fragments were subcloned using the pGEM-T Easy Vector System (Promega, Madison, WI) and at least 10 individual plasmid clones were sequenced using CEQ 8000 (Beckman Coulter, Tokyo, Japan).

DNMT activity analysis

Nuclear proteins were isolated from A549 cells using EpiQuikTM Nuclear Extraction kit I (Epigentek Group, Farmingdale, NY) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. After nuclear extraction, the protein concentration of the supernatant was assayed using a Bio-Rad protein assay reagent. An aliquot of the nuclear extract (10 µg) was subjected to the measurement of DNA methyltransferase (DNMT) activity. DNMT activity was measured using the EpiQuikTM DNMT Activity/Inhibition Assay Ultra kit (Colorimetric) (Epigentek Group) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Data analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± SD from at least three experiments. Data were analyzed by the Mann-Whitney U test. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Effects of exendin-4 on EC-SOD expression in A549 cells

The treatment of A549 cells with exendin-4 for 24 h significantly induced the expression of EC-SOD, but not that of Cu,Zn-SOD or Mn-SOD, the other SODs isozymes (Fig. 1A). Furthermore, the treatment with Aza, a DNA methyltransferase inhibitor, also increased the expression of EC-SOD, but not that of Cu,Zn-SOD or Mn-SOD (Fig. 1A). These results suggested that exendin-4 acted as a DNA demethylation agent. Moreover, the up-regulation of EC-SOD by exendin-4 was significantly suppressed by the addition of exendin-(9-39), an antagonist of GLP-1R(18,28) (Fig. 1B), suggesting that exendin-4 induced the expression of EC-SOD by binding to GLP-1R.

Fig. 1.

Effects of exendin-4 on EC-SOD expression in A549 cells. (A) A549 cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of exendin-4 or 1 µM Aza for 24 h, followed by the measurement of SODs mRNA levels. (B) A549 cells were pretreated with (+) or without (–) 200 nM exendin-(9-39) for 1 h, and then treated with (+) or without (–) 100 nM exendin-4 for 24 h. Real-time RT-PCR data were normalized using 18S rRNA levels. Data are shown as the mean ± SD (n = 3). *p<0.01 vs vehicle, #p<0.05 vs exendin-4-treated cells.

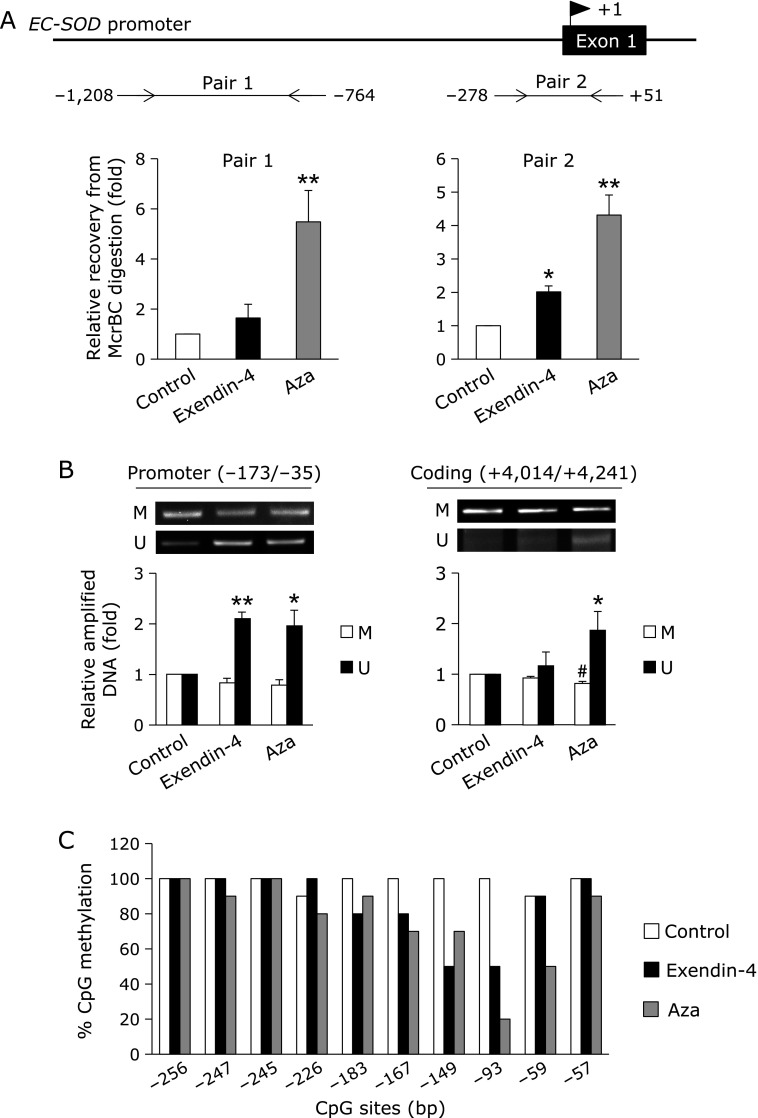

DNA demethylation within the EC-SOD promoter region by the exendin-4 treatment

Exendin-4 was previously reported to potentially regulate DNA methylation for gene expression.(26) On the other hand, low expression of EC-SOD in A549 cells is known to be due to DNA methylation. The DNA methylation within EC-SOD promoter region attenuates Sp1/3 transcriptional factor binding to EC-SOD promoter.(24,25) Therefore, we investigated the involvement of DNA demethylation in the exendin-4-induced up-regulated expression of EC-SOD. The DNA methylation status was analyzed using methylation-requiring nuclease McrBC. PCR amplification of EC-SOD promoter regions from –1,208 to –764 (Pair 1) and –278 to +51 (Pair 2) showed that genomic DNA in untreated A549 cells was digested by McrBC, while genomic DNA in Aza-treated A549 cells was resistant to McrBC in the Pair 1 and Pair 2 regions (Fig. 2A). Genomic DNA in exendin-4-treated A549 cells was digested by McrBC in the Pair 1 region, but it in the Pair 2 region resisted McrBC digestion (Fig. 2A). We then determined whether DNA methylation in the promoter (–173 to –35) and coding regions (+4,014 to +4,241) was changed by exendin-4. The genomic DNA of A549 cells was treated with bisulfate, and followed by MSP amplification with methylation (M) and non-methylation (U) site primers. As shown in Fig. 2B, the MSP analysis revealed that the treatment with Aza demethylated DNA in the EC-SOD promoter and coding regions. When cells were treated with exendin-4, DNA demethylation was observed in the EC-SOD promoter region, but not in the coding region. We investigated DNA demethylation in the EC-SOD promoter region in exendin-4-treated A549 cells in more detail. We determined that the treatment with exendin-4 or Aza was more likely to demethylate the –149 and –93 CpG sites in the region from –291 to +36 in A549 cells (Fig. 2C). These results suggested that the up-regulated expression of EC-SOD with exendin-4 was induced by DNA demethylation in a narrow range of CpG sites in the EC-SOD promoter region of A549 cells.

Fig. 2.

Involvement of DNA demethylation in exendin-4-inducible EC-SOD expression in A549 cells. A549 cells were treated with 100 nM exendin-4 or 1 µM Aza for 24 h. (A) After these treatments, genomic DNA from A549 cells was purified, and followed by McrBC digestion-real-time RT-PCR. Data are shown as the mean ± SD (n = 3). *p<0.05, **p<0.01 vs vehicle. (B) The genomic DNA of A549 cells was purified and treated with bisulfite, followed by methylation-specific PCR (MSP) amplification with methylation (M) and non-methylation (U) site primers. Data are shown as the mean ± SD (n = 3). *p<0.05, **p<0.01 vs control (U). #p<0.01 vs control (M). (C) Amplified sequences were subjected to a DNA sequence analysis. At least 10 individual clones were sequenced for both cell types.

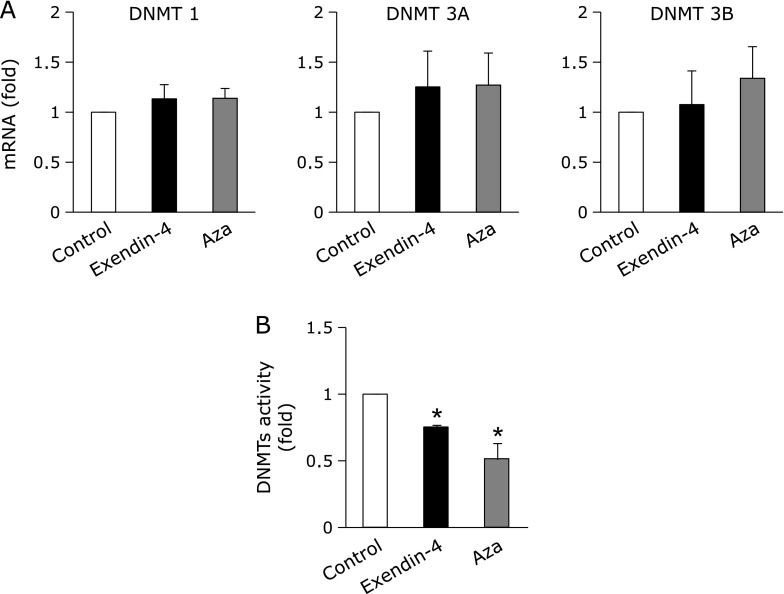

Effects of exendin-4 on DNMTs in A549 cells

DNA methylation is known to be mediated by DNMTs.(5,16) The treatment with exendin-4 or Aza for 24 h did not change the expression of DNMTs (Fig. 3A). We next investigated changes in the activities of DNMTs in exendin-4-treated A549 cells. As shown in Fig. 3B, exendin-4 and Aza both significantly reduced the enzymatic activity of DNMT.

Fig. 3.

Effects of exendin-4 on DNMTs in A549 cells. A549 cells were treated with 100 nM exendin-4 or 1 µM Aza for 24 h. mRNA expression levels of DNMTs (A) and DNMT activity (B) were then assayed. (A) Real-time RT-PCR data were normalized using 18S rRNA levels. (B) The activity of DNMT in nuclear extracts was determined by the method described in the Materials and Methods. Data are shown as the mean ± SD (n = 3). *p<0.01 vs vehicle.

Discussion

Various cancer genes and cancer suppressor genes induce genetic alterations during carcinogenesis. DNA methylation in a gene promoter region represents an inactivating mechanism for cancer suppressor genes as well as gene mutations and chromosomal deletions. EC-SOD was previously shown to inhibit tumor growth in pancreatic cancer.(9) However, EC-SOD is known to be expressed at very low levels in the human lung adenocarcinoma epithelial cell line A549 due to the hypermethylation of CpG islands in the EC-SOD promoter region.(8) The main results of the present study is that exendin-4 up-regulated the expression of EC-SOD by its binding to GLP-1R in A549 cells. Pinney et al.(26) recently demonstrated that exendin-4 regulated gene expression through an epigenetic mechanism. They showed that the administration of exendin-4 induced pancreatic and duodenal homobox-1 (Pdx1) transcriptional factor in intrauterine growth retardation (IUGR) pancreatic islets in an in vivo experiment. Exendin-4 induced the histone acetylation and demethylation of promoter DNA in the Pdx1 gene. The GLP-1 receptor is widely expressed in various tissues/organs besides the pancreas, suggesting that GLP-1 analogues regulate various genes through an epigenetic mechanism. We herein found that exendin-4 induced the expression of EC-SOD in the A549 lung cancer cell line through the demethylation of DNA in its promoter region.

To elucidate the epigenetic mechanism associated with DNA methylation within the EC-SOD promoter region in A549 cells, we investigated whether the expression and activities of DNMTs were changed by exendin-4. DNA methylation has been classified into maintenance methylation and de novo methylation. DNMT1 (maintenance DNMT) has been shown to copy methylation to the daughter strand by selectively methylating hemi-methylated DNA following semiconservative DNA replication. DNMT1 is characterized by higher enzyme activity against hemi-methylated DNA than unmodified DNA.(29) A previous study reported that Aza irreversibly bound DNMT1, and DNMT1 then became a DNA adduct and was degraded.(30) In the present study, the treatment with Aza and also exendin-4 significantly demethylated DNA within the EC-SOD promoter and induced the expression of EC-SOD (Fig. 1A and 2) with a significant decrease enzymatic activity of DNMT (Fig. 3B). The basal and inducible transcription of human EC-SOD is regulated by Sp1/Sp3 transcriptional factors, which bind to the proximal promoter.(24,31) However, a CpG site only exists downstream of the Sp1/Sp3 binding region. As shown in Fig. 2C, the treatment with exendin-4 was more likely to demethylate the –149 and –93 CpG sites in this region, indicating that the expression of EC-SOD may be susceptible to the methylation of CpG sites downstream of the Sp1/Sp3 binding region.

The principle structure of eukaryotic chromatin is the core nucleosome, which consists of an octamer of histones. Chromatin exists in two different states, an open and closed configuration, and these are closely associated with the acetylation/deacetylation of histones by histone acetyltransferase (HAT) and histone deacetylase (HDAC). The acetylation of histone neutralizes the positive charge and facilitates the binding of transcription factors to nucleosomal DNA, thereby enhancing its transcription. We previously reported that the 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA)-induced expression of EC-SOD in monocytic THP-1 cells was positively related with the acetylation status of histone H3 and H4.(32) Moreover, a treatment with the HDAC inhibitor trichostatin A (TSA) significantly induced the expression of EC-SOD. However, the expression of EC-SOD in A549 cells was not induced by the TSA treatment (data not shown), suggesting that histone modifications did not contribute to the regulation of EC-SOD expression in A549 cells.

In conclusion, the results of the present study suggest that exendin-4-inducible EC-SOD expression in A549 cells was regulated by DNA demethylation through the reduction in the activity of DNMTs. We were unable to clarify the mechanisms by which DNMTs were reduced in the activity by exendin-4. Therefore, additional studies are needed to determine the precise molecular mechanism underlying DNA demethylation within the EC-SOD promoter region. Exendin-4 has been widely approved as a treatment for type 2 diabetes and exerts its pancreatic and extrapancreatic effects by binding to GLP-1R, which is distributed in many tissues. GLP-1 and its analogues may function to maintain physiological homeostasis by epigenetically regulating various genes.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 25460654 (TA).

Abbreviations

- Aza

5-azacytidine

- DNMT

DNA methyltransferase

- DPP-4

dipeptidyl peptidase 4

- EC-SOD

extracellular-superoxide dismutase

- GLP-1

glucagon-like peptide 1

- GLP-1R

glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor

- HAT

histone acetyltransferase

- HDAC

histone deacetylase

- IUGR

intrauterine growth retardation

- MSP

methylation-specific polymerase chain reaction

- Pdx1

pancreatic and duodenal homobox-1

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SAM

S-adenosylmethionine

- TPA

12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate

- TSA

trichostatin A

Conflict of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- 1.Cave AC, Brewer AC, Narayanapanicker A, et al. NADPH oxidases in cardiovascular health and disease. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2006;8:691–728. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wright E, Jr, Scism-Bacon JL, Glass LC. Oxidative stress in type 2 diabetes: the role of fasting and postprandial glycaemia. Int J Clin Pract. 2006;60:308–314. doi: 10.1111/j.1368-5031.2006.00825.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vachier I, Chanez P, Le Doucen C, Damon M, Descomps B, Godard P. Enhancement of reactive oxygen species formation in stable and unstable asthmatic patients. Eur Respir J. 1994;7:1585–1592. doi: 10.1183/09031936.94.07091585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ookawara T, Imazeki N, Matsubara O, et al. Tissue distribution of immunoreactive mouse extracellular superoxide dismutase. Am J Physiol. 1998;275 (3 Pt 1):C840–C847. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.275.3.C840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Folz RJ, Guan J, Seldin MF, Oury TD, Enghild JJ, Crapo JD. Mouse extracellular superoxide dismutase: primary structure, tissue-specific gene expression, chromosomal localization, and lung in situ hybridization. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1997;17:393–403. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.17.4.2826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Strålin P, Marklund SL. Vasoactive factors and growth factors alter vascular smooth muscle cell EC-SOD expression. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;281:H1621–H1629. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.281.4.H1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heistad DD. Oxidative stress and vascular disease: 2005 Duff lecture. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:689–695. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000203525.62147.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Teoh-Fitzgerald ML, Fitzgerald MP, Jensen TJ, Futscher BW, Domann FE. Genetic and epigenetic inactivation of extracellular superoxide dismutase promotes an invasive phenotype in human lung cancer by disrupting ECM homeostasis. Mol Cancer Res. 2012;10:40–51. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-11-0501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sibenaller ZA, Welsh JL, Du C, et al. Extracellular superoxide dismutase suppresses hypoxia-inducible factor-1α in pancreatic cancer. Free Radic Biol Med. 2014;69:357–366. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2014.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kristensen LS, Nielsen HM, Hansen LL. Epigenetics and cancer treatment. Eur J Pharmacol. 2009;625:131–142. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reik W. Stability and flexibility of epigenetic gene regulation in mammalian development. Nature. 2007;447:425–432. doi: 10.1038/nature05918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Illingworth RS, Bird AP. CpG islands--‘a rough guide’. FEBS Lett. 2009;583:1713–1720. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chatterjee R, Vinson C. CpG methylation recruits sequence specific transcription factors essential for tissue specific gene expression. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1819:763–770. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2012.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pellacani D, Kestoras D, Droop AP, et al. DNA hypermethylation in prostate cancer is a consequence of aberrant epithelial differentiation and hyperproliferation. Cell Death Differ. 2014;21:761–773. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2013.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen T, Li E. Structure and function of eukaryotic DNA methyltransferase. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2004;60:55–89. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(04)60003-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jones PA, Liang G. Rethinking how DNA methylation patterns are maintained. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:805–811. doi: 10.1038/nrg2651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buse JB, Henry RR, Han J, Kim DD, Fineman MS, Baron AD, ; Exenatide-113 Clinical Study Group Effects of exenatide (exendin-4) on glycemic control over 30 weeks in sulfonylurea-treated patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:2628–2635. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.11.2628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thorens B, Porret A, Bühler L, Deng SP, Morel P, Widmann C. Cloning and functional expression of the human islet GLP-1 receptor. Demonstration that exendin-4 is an agonist and exendin-(9-39) an antagonist of the receptor. Diabetes. 1993;42:1678–1682. doi: 10.2337/diab.42.11.1678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ban K, Noyan-Ashraf MH, Hoefer J, Bolz SS, Drucker DJ, Husain M. Cardioprotective and vasodilatory actions of glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor are mediated through both glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor-dependent and -independent pathways. Circulation. 2008;117:2340–2350. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.739938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fattman CL, Schaefer LM, Oury TD. Extracellular superoxide dismutase in biology and medicine. Free Radic Biol Med. 2003;35:236–256. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(03)00275-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adachi T, Inoue M, Hara H, Maehata E, Suzuki S. Relationship of plasma extracellular-superoxide dismutase level with insulin resistance in type 2 diabetic patients. J Endocrinol. 2004;181:413–417. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1810413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fujita H, Fujishima H, Chida S, et al. Reduction of renal superoxide dismutase in progressive diabetic nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:1303–1313. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008080844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Call JA, Chain KH, Martin KS, et al. Enhanced skeletal muscle expression of extracellular superoxide dismutase mitigates streptozotocin-induced diabetic cardiomyopathy by reducing oxidative stress and aberrant cell signaling. Circ Heart Fail. 2015;8:188–197. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.114.001540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zelko IN, Mueller MR, Folz RJ. CpG methylation attenuates Sp1 and Sp3 binding to the human extracellular superoxide dismutase promoter and regulates its cell-specific expression. Free Radic Biol Med. 2010;48:895–904. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zelko IN, Mueller MR, Folz RJ. Transcription factors Sp1 and Sp3 regulate expression of human extracellular superoxide dismutase in lung fibroblasts. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2008;39:243–251. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2007-0378OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pinney SE, Jaeckle Santos LJ, Han Y, Stoffers DA, Simmons RA. Exendin-4 increases histone acetylase activity and reverses epigenetic modifications that silence Pdx1 in the intrauterine growth retarded rat. Diabetologia. 2011;54:2606–2614. doi: 10.1007/s00125-011-2250-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adachi T, Teramachi M, Yasuda H, Kamiya T, Hara H. Contribution of p38 MAPK, NF-κB and glucocorticoid signaling pathways to ER stress-induced increase in retinal endothelial permeability. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2012;520:30–35. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2012.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Skoglund G, Hussain MA, Holz GG. Glucagon-like peptide 1 stimulates insulin gene promoter activity by protein kinase A-independent activation of the rat insulin I gene cAMP response element. Diabetes. 2000;49:1156–1164. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.7.1156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mohan KN, Chaillet JR. Cell and molecular biology of DNA methyltransferase 1. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 2013;306:1–42. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-407694-5.00001-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ghoshal K, Datta J, Majumder S, et al. 5-Aza-deoxycytidine induces selective degradation of DNA methyltransferase 1 by a proteasomal pathway that requires the KEN box, bromo-adjacent homology domain, and nuclear localization signal. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:4727–4741. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.11.4727-4741.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 31.Zelko IN, Folz RJ. Sp1 and Sp3 transcription factors mediate trichostatin A-induced and basal expression of extracellular superoxide dismutase. Free Radic Biol Med. 2004;37:1256–1271. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kamiya T, Machiura M, Makino J, Hara H, Hozumi I, Adachi T. Epigenetic regulation of extracellular-superoxide dismutase in human monocytes. Free Radic Biol Med. 2013;61:197–205. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]