Abstract

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a significant global pathogen, infecting more than 240 million people worldwide. While treatment for HBV has improved, HBV patients often require life-long therapies and cure is still a challenging goal. Recent advances in technologies and pharmaceutical sciences have heralded a new horizon of innovative therapeutic approaches that are bringing us closer to the possibility of a functional cure of chronic HBV infection. In this article, we review the current state of science in HBV therapy and highlight new and exciting therapeutic strategies spurred by recent scientific advances. Some of these therapies have already entered into clinical phase and we will likely see more of them moving along the development pipeline. With a growing interest in and effort to developing more effective therapies for HBV, the challenging goal of a cure may be well within reach in the near future.

Despite the availability of effective vaccines for three decades and improvement of treatment, the prevalence of chronic HBV infection worldwide has declined minimally from 4.2% in 1990 to 3.7% in 2005 (1). Moreover, the actual number of persons who are chronically infected is estimated to have increased slightly from 223 million to 240 million during this same period. Treatment for this infection, while advancing to the stage that viral replication can be effectively suppressed and disease successfully controlled, is still handicapped by various limitations and cannot be considered as curative. Recognizing HBV therapeutics is at the cusp of innovations and breakthroughs, this review summarizes new targets among the HBV viral and host immune systems for which drugs are now in late preclinical development and clinical testing. In addition, novel and potentially promising therapeutic strategies that would likely result in more durable and complete responses are highlighted. To put these advances in the context of the current state of the science, we summarize the current HBV therapies and their limitations, and spotlight the continued impact of fundamental scientific discoveries in advancing the research and development of new HBV therapies.

Natural History of Chronic Hepatitis B

The course of chronic HBV infection has been grouped into four phases: the “immune tolerant” phase; the “immune active/HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis” phase; “immune active/HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis” phase; the “immune active/HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis” phase. However these terms may not accurately reflect the immunological status of patients in each phase but are useful for prognosis and determining need for therapy (2, 3). The duration of each phase varies from months to decades. Transitions can occur not only from an earlier to a later phase but regressions back to an earlier phase can also occur (4). It should be noted that not all patients go through all four phases. Furthermore, while the cutoff levels of ALT used to define different phases were traditionally based on upper limits of normal determined by clinical diagnostic laboratories, recent studies suggest that the true normal values are lower (5)

HBV Replication: From Basic Science to Drug Development

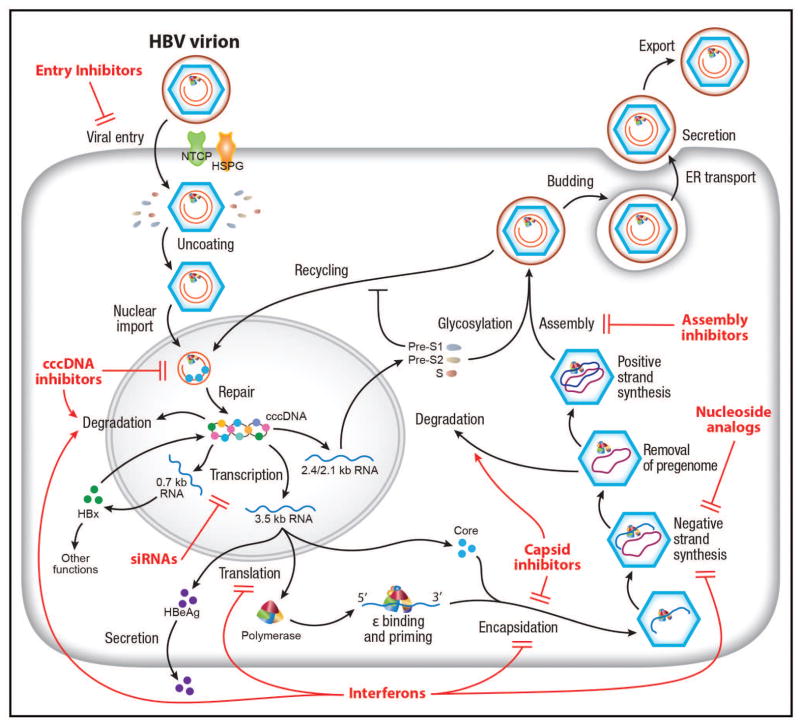

Advances in understanding the molecular biology and replication cycle of HBV have provided unprecedented insight into the mechanisms of action and treatment response of currently available drugs against HBV as well as potential future targets for therapeutic development (Fig. 1). HBV gains entry into hepatocytes initially through a low-affinity interaction between heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPG) on the hepatocytes and the antigenic loop (“a” determinant or antibody neutralization domain) of the HBV envelope proteins (6, 7) and then a high-affinity interaction of the myristoylated pre-S1 domain with the liver-specific receptor, sodium-taurocholate co-transporter (NTCP) (8). NTCP is exclusively expressed on the basolateral/sinusoidal membrane of hepatocytes. Its natural function is to re-transport conjugated bile salts (e.g. taurocholate (TCA)) into hepatocytes as part of the enterohepatic pathway (9). Accordingly, NTCP plays a key role in the liver tropism of HBV (10, 11). NTCP is also crucial for the host specificity of HBV. Two short sequence motifs within NTCP are sufficient to render the respective proteins from cynomolgus monkey and mouse functioning as a HBV receptor (12, 13). Additional host factors are probably required for efficient HBV entry. Fusion of HBV particles and release of nucleocapsids into the cells involves receptor-mediated endocytosis (14, 15).

Figure 1.

HBV life cycle and targets of therapeutic development. The complete HBV life cycle including entry, trafficking, cccDNA formation, transcription, encapsidation, replication, assembly and secretion is shown here. The functions of the HBV gene products are incorporated into the life cycle. Drugs or biologics, in clinical use or development, targeting various steps of the HBV life cycle are illustrated in red. See text for details of these drugs.

The HBV genome-containing nucleocapid is then transported into the nucleus via a yet-undefined pathway, probably involving microtubule and nuclear importin machinery (16). In the nucleus, the relaxed circular, partially double-stranded genome (rcDNA) is then repaired to a full-length, circular DNA by covalently attached viral polymerase (P) and other incompletely understood mechanisms probably involving tyrosyl DNA phosphodiesterase of the topoisomerase and DNA repair pathway (17). The circularized protein-free genome then complexes with host histone and non-histone proteins including various histone-modifying enzymes into a minichromosome that functions as the template for transcription (18). Its transcriptional activity is regulated by epigenetic modifications and specific host transcriptional factors, such as HNF4 (19). HBV core and X proteins are also present on the minichromosome and probably play an important role in HBV transcription (18, 20, 21). The cccDNA is transcribed to three classes of HBV RNAs: genomic-length RNAs (pregenomic and precore RNAs coding for core gene products and P protein), S RNAs (S proteins) and X RNA (HBx protein). The pregenomic RNA transcript is reverse-transcribed by the P protein to rcDNA in the core-containing nucleocapsid. The nucleocapsid can either assemble into an infectious virion with the envelope proteins via the multivesicular body pathway (22) or recycle back to the nucleus for cccDNA amplification in a process probably controlled by the pre-S1 envelope protein and other host factors (23). The steady-state population of cccDNA is about 1–10 molecules per infected hepatocyte (24).

Current Therapies of Hepatitis B and Mechanisms of Actions

There are currently two classes of drugs approved for the treatment of hepatitis B: nucleos(t)ide reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) and interferon-α. The first-line antiviral HBV medications include a nucleoside analogue - entecavir, a nucleotide analogue - tenofovir, and pegylated interferon-α, used as monotherapy. (25–27). Peginterferon is administered for 48–52 weeks. While it has a weaker antiviral activity than NRTIs, it is associated with a higher rate of HBeAg and HBsAg loss, possibly through a combination of direct antiviral and immunomodulatory effects. By contrast, NRTIs target only reverse transcription of pregenomic RNA to HBV DNA and have no direct effect on cccDNA. Long-term treatment with more potent NRTIs can lead to progressive loss of HBeAg and HBsAg with time.

Interferon-α, as a front-line host defense against viral infections, is known to induce interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs), which have promiscuous antiviral functions against a variety of viruses. Depending on the viruses, these ISGs play a diverse and pleiotropic role in targeting various viral functions at different steps of viral replication cycle and potently suppress viral infection and spread. Interferon-α has a direct anti-HBV effect and acts on multiple steps of the HBV replication cycle (Fig. 1) (28, 29). In addition, it has an immunomodulatory effect that can indirectly inhibit HBV replication by affecting cell-mediated immunity in vivo (30). Studies of the HBV kinetics in interferon-α treated patients suggest a more relevant role of the latter mechanism in mediating interferon-α’s anti-HBV effects (31).

Despite targeting multiple steps of HBV replication, the molecular mechanisms underlying interferon-α’s action remain to be fully defined. Interferon-α is thought to induce specific ISGs that inhibit HBV transcription or prevent the formation of nucleocapsid or target it for degradation (28, 29, 32). The responsible ISGs have not been clearly defined. Interferon-α’s effect on HBV transcription is partly mediated by epigenetic modifications of the cccDNA minichromosome (33). Recent development of infectious HBV cell culture systems provided the much-needed tools and models to study the effects of antivirals, including interferon, on HBV replication (33, 34). A recent study demonstrated that interferon-α and another putative antiviral cytokine, lymphotoxin-β (LT-β), induces the degradation of cccDNA in infectious cell culture systems (35). This effect is mediated by induction of the APOBEC3 family of proteins, specifically APOBEC3A by interferon-α and APOBEC3B by lymphotoxin (LT)-β. APOBEC3 functions to restrict foreign DNAs, such as those from invading microbial genomes, which activate the interferon response including induction of APOBEC3s as ISGs (36). The APOBEC3s are DNA editing enzymes and deaminate foreign double-stranded DNA cytidines to uridines (36). This conversion can lead to either C to T mutations or degradation of foreign DNA. In contrast cellular genomic DNA is unaffected. APOBEC3s are known to target HIV, AAV and possibly other DNA viral genomes for degradation (36). For HBV, the role of APOBEC3 has been controversial. APOBEC3G was shown to inhibit HBV replication in cell culture but the mechanism had been attributed to either direct inhibition of HBV replication or hyper-mutations from DNA editing (37–40). All the earlier studies were performed in HBV DNA transfection systems that could not be used to investigate cccDNA. In an HBV infectious culture system, the induced APOBEC3 interacted with the core protein and translocated to the nucleus to target cccDNA (35).

The development of nucleoside analogs owes much of its success to the comprehensive understanding of how HBV replicates. Based on the model of HBV replication, the P protein has been the primary therapeutic target in HBV drug development (Fig 1). While this advance represents a pivotal step in the chronicle of HBV treatment, knowledge of mechanism of action of this class of anti-HBV drugs also exposes its limitation, as discussed above.

While the second-generation NRTIs, such as entecavir and tenofovir, can potently suppress the DNA synthesis step of HBV replication, they have little effect on the level and activity of cccDNA, which has a long half-life and can persist for decades in the infected liver despite successful antiviral treatment (24). This limitation explains the necessity for a prolonged, possibly indefinite, treatment with this class of anti-HBV drugs. The turnover of cccDNA has been the subject of intense research because of its fundamental importance in HBV replication and therapy. Several mechanisms appear to explain the turnover of cccDNA in vivo. First, the direct cytopathic effect of activated HBV-specific T lymphocytes can cause death of infected cells. Second, gradual loss of cccDNA pool by cell proliferation in injured liver can account partly for gradual loss of cccDNA. Finally, non-cytopathic mechanism of eliminating cccDNA from infected cells contributes to the turnover of cccDNA (41). Interferons and other cytokines have been implicated in this “cell cure” mechanism, but the precise mechanism is unknown (41).

Entecavir and tenofovir can decrease the level of HBV DNA by 6 logs within 1 year of treatment and have low rates of antiviral drug resistance (0–1% after 5 years of continued treatment) (42, 43). However, rates of HBeAg seroconversion (~20% after 1 year and 40–50% after 5 years) and HBsAg loss (5–10% after 5 years) are low. Therefore, most patients require many years and often lifelong treatment with associated costs and risks of adverse reactions, drug resistance and non-adherence (44). Despite these limitations, antiviral treatment can reverse liver fibrosis and even cirrhosis, prevent cirrhosis complications, and reduce though not eliminate the risk of HCC (45, 46). Derivatives of tenofovir as prodrugs with improved pharmacological properties are being developed and may be of benefit in certain situation (47).

For patients who do not have cirrhosis or do not require immunosuppressive therapy, professional society guidelines recommend treating those in the immune active phase (25–27), although treatment at an earlier stage has been proposed to minimize unrecognized yet significant liver damage (48). However, treatment during the “immune tolerant” phase is associated with a low rate of HBeAg seroconversion and failure to completely suppress HBV DNA to non-detectable levels (49).

The ultimate goal of antiviral therapy would be to eliminate all forms of potentially replicating HBV but this may not be feasible because even in persons who recover from acute HBV infection with HBsAg to anti-HBs seroconversion, HBV persists in the liver in the form of cccDNA and can be reactivated during immunosuppressive therapy. A more realistic goal is a “functional cure” in which HBV DNA is not detectable after the completion of a finite course of treatment with loss of HBsAg and minimization of HCC risk over time. To accomplish this goal, a combination of antiviral drugs that target different steps in the HBV life cycle or immunomodulatory therapies to restore host immune response to HBV will be needed.

Combination Studies of Current Therapies

Given that only 2 classes of anti-HBV agents are currently available, combination therapy consist of two NRTIs or a NRTI plus peginterferon. In the latter case a NRTI and peginterferon may be combined simultaneously, sequentially, starting with either drug first, or as an add-on strategy with either drug first.

Initially, the clinical need to increase the potency of first-generation antivirals and to prevent emergence of antiviral resistance was the primary reason to test combination therapy with NRTIs. Unfortunately, this approach suffered from the fact that all NRTIs have the same virological target, the HBV polymerase. Thus, the treatment response observed in patients was similar to that of the most potent agent in the combination. The issue of antiviral resistance is now greatly diminished with the development of second-generation NRTIs, such as entecavir and tenofovir. The efficacy and safety of entecavir and tenofovir combination therapy was compared to entecavir monotherapy in previously untreated HBV patients (50). A greater proportion of subjects receiving combination therapy achieved viral suppression compared to entecavir alone, but the difference was not statistically significant (50). However HBeAg-positive subjects with baseline HBV DNA ≥ 08 IU/mL receiving combination therapy had a significantly higher rate of virological response compared to those receiving monotherapy (50).

Conceptually, combination of peginterferon with a NRTI would be more likely to result in synergy because the drugs have different mechanisms of action. The concept being that inhibition of viral replication with a NRTI may augment the immune effects of peginterferon. Unfortunately, while studies of peginterferon in combination with first-generation NRTIs did show synergy in achieving viral suppression and reducing the incidence of antiviral resistance, off-treatment responses were similar to that of peginterferon alone (51, 52). The availability of more potent, second-line NRTIs together with a renewed interest in achieving HBsAg clearance has stimulated interest in combining these agents together or in combination with peginterferon.

Simultaneous peginterferon and tenofovir was evaluated in treatment-naïve patients with HBeAg-positive and -negative chronic hepatitis B (43). Patients receiving peginterferon and tenofovir had a higher rate of HBsAg loss than those receiving either drug along (43). Although these results are encouraging, they represent a small increase (6%) in HBsAg loss over peginterferon monotherapy and a benefit was mainly observed in those with genotype A infection.

Sequential therapy beginning either with a NRTI followed by peginterferon or vice versa for variable durations has been conducted in both HBeAg-positive and -negative subjects. In general these studies have not demonstrated a substantial benefit either in terms of on-treatment or sustained off-treatment HBV DNA suppression or HBeAg and HBsAg loss compared to peginterferon as a historical control (53–55).

Starting with NRTI first and adding peginterferon later would seem to be the most logical approach to combination therapy. The idea being that the NRTI would rapidly lower viral load and restore T-cell responsiveness and then adding peginterferon might hasten the decline of circulating and intrahepatic viral antigens leading to an improvement in the innate immune response (56). Several recent studies seem to support such an approach (57–59). Among HBeAg-positive subjects, higher rates of HBeAg seroconversion were achieved with add-on combination therapy of peginterferon and NRTI (27%) compared to NRTI only (0%) (58). Among HBeAg-negative subjects, HBsAg loss was reported in 6.6% of subjects at the end of therapy in the combination arm vs. 1% in the NRTI-only arm (59). None of these studies included an arm using peginterferon monotherapy and when compared to historical studies of peginterferon monotherapy, the results obtained with combination therapy are comparable.

A recent study compared peginterferon alone to peginterferon followed by add-on entecavir, or entecavir followed by add-on peginterferon (60). Rates of HBeAg seroconversion post-treatment were similar across treatment groups (60). With an add-on strategy, a longer duration of NRTI before add-on peginterferon and longer duration of peginterferon therapy was associated with higher rates of HBeAg and HBsAg loss.

In summary, there is insufficient data at present to recommend the use of combination therapy except in very special circumstances such as in subjects with very high baseline viral levels (>108 IU/ml), or for management of subjects who have failed a first-line agent due to a suboptimal response or the development of multidrug resistance. Further studies are needed to address the benefit of various formats of combination therapy with peginterferon and more potent NRTIs.

HBV Entry Inhibitors

Entry inhibitors have been used successfully in treating viral infections. In particular, small molecules and antibody-based treatments are quite effective in treating acute viral infections (61). For chronic viral infection like HIV, entry inhibitors have also been successfully developed (62). For HBV, entry inhibitors can be applied in two ways. The first is in a preventive setting: entry inhibition blocks de novo HBV infection. This application has been successfully demonstrated in animal models (63) and is clinically a standard of care by using HBsAg-specific immunoglobulins to prevent reinfection after liver transplantation, to avoid vertical transmission of HBV from infected mothers to children, and for post exposure prophylaxis (64). Regarding chronic hepatitis B patients, whether entry inhibition would be a viable therapeutic option is debatable. It is conceivable that potent blockade of HBV reinfection in chronically infected patients can reduce viral load due to the turnover of HBV-infected hepatocytes (65). Previous studies suggested that hepatocyte turnover is indeed much faster in HBV-infected liver than in healthy hepatocytes, because of immune-mediated cytotoxicity (66). As a result, a sustained inhibition of de novo formation of cccDNA in hepatocytes may contribute to the eventual clearance of the virus with prolonged therapy, especially if it is used in combination with other potent anti-HBV drugs. Because hepatitis D virus (HDV) shares the same entry pathway, another potential application of entry inhibitors is in HBV/HDV co-infection.

HBV entry depends on the pre-S1 sequence, more specifically the myristoylated N-terminus of the large envelope protein (LHBsAg). Both the myristoylation and the N-terminal 75 amino acids are required for infectivity of HBV (67, 68). It was shown that synthetic lipopeptides representing this subdomain potently inhibit HBV infection. The mode of action of such peptidic inhibitors (Myrcludex B, for example) could be attributed to specific receptor binding (11). Myrcludex B successfully passed phase I clinical trials (Blank et al, submitted). Moreover, since the natural role of NTCP as a bile salt transporter has been studied in some detail, molecules already known to bind or inhibit the function of NTCP have been tested. Cyclosporine A and its derivatives (e.g. Alisporivir) or approved drugs like Ezetimibe are amongst those that have been demonstrated to inhibit HBV entry (69–71).

Myrcludex B, cyclosporine A and other substrate-analogs inhibit bile salt transport by NTCP. Accordingly, these molecules may elevate bile salts and other transported substrates in the serum of patients. This concern may be a clinically manageable problem. First, people with polymorphisms in NTCP resulting in a functional knockdown show very moderate clinical symptoms and do not develop any specific pathology (72). Second, NTCP knock-out mice are viable, show elevated conjugated bile salt levels without symptoms but have a slight retardation in growth during development (73). Most importantly, the antiviral effect of Myrcludex B and cyclosporin A is already apparent at a much lower concentration than that required for inhibiting bile acid transport (>100-fold difference) (12, 70). Thus, entry inhibition should be clinically achievable without significant interference with the transporter function of the receptor.

Myrcludex B is currently being tested in two ongoing clinical trials (74). Preliminary results suggested that Myrcludex B is safe and well tolerated in HBsAg-positive patients with or without HDV co-infection. A decline in the HBV DNA level (>1 log10) was reported in 87% of patients at 12 weeks of treatment (10 mg/day) and the decline continued with extended treatment beyond 12 weeks. Myrcludex B treatment at high doses was associated with some bile acid elevation.

HBV Capsid Inhibitors

Several classes of inhibitors of pgRNA packaging and HBV capsid assembly have been identified. They function to dysregulate or selectively inhibit either pgRNA encapsidation or nucleocapsid assembly or both. The first of these was the phenylpropenamide derivatives AT-61 and AT-130 (75). These compounds selectively inhibit viral pgRNA packaging (76) and are active against both wild-type and lamivudine-resistant HBV (77, 78). As a class and at the molecular level, these agents have been shown to induce tertiary and quaternary structural changes in HBV capsids. AT-130 binds to a promiscuous pocket at the core dimer-dimer interface (79). This binding decreases viral production by initiating virion assembly prematurely in the replication cycle, resulting in morphologically normal capsids that are empty and non-infectious (76).

The second group of inhibitors are the heteroaryldihydropyrimidines, or B-HAPs, that inhibit HBV virion production in vitro and in vivo by preventing capsid formation (80). The best studied of these B-HAPS, Bay 41-4109, has a dual mechanism of action by inhibiting encapsidation directly and causing a concomitant reduction in the half-life of the core protein. Structural studies of this class of inhibitors revealed that they induce inappropriate capsid assembly at low concentrations, and when in excess, promote a misdirected assembly reaction and decreased capsid stability (81, 82). Like the phenylpropenamides, the B-HAPs are active against NRTI-resistant strains of HBV (78).

Other inhibitors targeting the nucleocapsid are being developed by several biotech companies (83) (Table 1). In vitro studies have demonstrated strong synergy when these inhibitors are used in combination with currently approved NRTIs (77, 78)

Table 1.

Experimental HBV therapeutics in late preclinical or clinical stage*

| Compound | Mechanism/ target† | Stage of Development | Sponsor | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct acting antiviral† | ||||

| GS-7340 (tenofovir alafenamide fumarate | Polymerase (prodrug of tenofovir) | Phase II/III | Gilead Sci | (47); NCT0194047,NCT01940341‡ |

| CMX157 | Polymerase (prodrug of tenofovir) | Phase I/II§ | Contravir (Chimerix) | (144); NCT01080820‡ |

| NVR1221/3778 | Capsid | Phase I/II | Noviro | (83); NCT02112799‡ |

| DVRs | Capsid | Animal | Oncore | (145) |

| Morphothiadine Mesilate (GLS4) | Capsid | Phase I | HEC Pharm Group, China | (146) |

| Bay41-4109 | Capsid | Phase I | AiCuris | (80) |

| REP 2139-Ca | Assembly/HBsAg | Phase I/II | Replicor | NCT02233075‡ |

| ARC-520 | RNAi | Phase I/II | Arrowhead | (93); Sponsor’s website; NCT02065336‡ |

| TKM-HBV | RNAi | Phase I | Tekmira | Sponsor’s website; NCT02041715‡ |

| ALN-HBV | RNAi | Animal | Alnylam | Sponsor’s website |

| ddRNAi | RNAi | Animal | Benitec | Sponsor’s website |

| ISIS HBV | Antisense | Phase I | Isis | Sponsor’s web site |

| Host targeting agent | ||||

| Myrcludex B | Entry/NTCP | Phase I/II | Myr-GmbH | (74) |

| Birinapant | Apoptosis/ Second Mitochondrial Activator of Caspases | Phase I | Tetralogic | Sponsor’s website; NCT02288208‡ |

| Flavonoids | STING agonist (pattern recognition receptor) | Animal | Oncore | (147) |

| NVP018 | Cyclophillins, IRF-9 | Animal | Oncore (NeuroVive) | Sponsor’s website |

| Editope HBV | Glucosidase/ therapeutic vaccine | Animal | Blumberg Institute | (148) |

| Immune modulatory agent | ||||

| GS-9620 | TLR-7 agonist | Phase II | Gilead Sciences | (120); NCT02166047‡ |

| Nivolumab | PD-1 blockade | Phase I†† | BMS | (149); Sponsor’s website NCT01658878‡ |

| SB 9200HBV | RIG-I & NOD2 activation | Phase I/II | INC/Springbank | (150); NCT018033084 |

| GS-4774 | Therapeutic vaccine | Phase II/III | Gilead Sci | (142); NCT02174276‡ |

| ANRS HB02 | Therapeutic vaccine | Phase I/II | French National Agency for Research on AIDS and Viral Hepatitis | (139); NCT02166047‡ |

| Heplisav B Dynavax 601 | Therapeutic vaccine | Phase I | Dynavax | (151); NCT01023230‡ |

| Nasvac | Therapeutic vaccine | Phase II/III | CGEB, Cuba | (152) |

| TG1050 | Therapeutic vaccine | Phase I/Ib | Transgene | NCT02428400 |

| HBIG +GM-CSF + HBV Vaccine | Therapeutic vaccine | Phase I/II | Beijing 302 Hospital | NCT01878565 |

| HBV Vaccine + IFN-α2b + IL2 | Therapeutic vaccine | Phase IV | Tongji Hospital | NCT02360592 |

| HB-Vac activated DC | Therapeutic vaccine | Phase I/II | Third Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-Sen University | NCT01935635 |

| Euvax + PEG IFN-α | Therapeutic vaccine | Phase IV | Seoul National University | NCT02097004 |

| PD-1 mAb | PD1 blockade | Animal | AcadSin | (153) |

| Altravax HBV | Therapeutic Vaccine | Animal | Altravax | Sponsor’s website |

| INO-1800 | Therapeutic Vaccine | Animal | Innovio | Sponsor’s website |

Compounds are organized by names and targets with developmental phase based on authors’ estimates derived from the literature wherever available, or Sponsor website and presentation information.

Mechanisms are characterized as either: Direct Acting Antiviral (DAA) indicating action against a virus specified gene product, immune modulatory agent (IMA) activating host immune response, or host targeting agent (HTA) which targets a host function required for HBV replication cycle.

Identifier for CLINICALTRIAL.GOV

In Phase II for HIV

Trial indication is for treatment of HBV-associated hepatocellular carcinoma

Inhibition of HBV Gene Expression

Persistence of HBV results from an ineffective antiviral immune response against the virus and one of the ways HBV orchestrates this is via excess production of sub-viral particles containing HBsAg. These non-infectious sub-viral particles (SVPs) may act as a decoy for the immune system (84), especially for mopping up potentially neutralizing anti-HBs. High levels of HBsAg, in the range of 400 μg/mL (0.4% of total serum protein), are commonly found in the blood of patients with chronic hepatitis B (85), and may interfere with HBV-specific immune responses (86, 87).

An alternative approach to inhibit HBV gene expression has been successfully achieved in vitro using molecular-based therapies targeting the viral mRNA. Viral mRNA can be directly targeted using anti-sense oligonucleotides, ribozymes, or RNA interference (RNAi) (88). Of these, RNAi appears most promising since efficient in vivo delivery systems have been developed by a number of biotech companies (Table 1).

RNAi is a process by which small interfering RNA molecules of 21–25 nucleotides induce gene silencing at the post-transcriptional level to effectively knock down the expression of the gene(s) of interest. Such short interfering RNA can lead to transcriptional silencing or translational repression (89). These processes are critical in cell growth regulation and tissue differentiation and involve the Drosha and Dicer enzyme complexes, the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) and the nuclease Argo (89). The extensive use of overlapping RNAs and ORFs within the HBV genome, makes for an attractive target for inhibition by RNAi (90). Both cell culture and mouse model studies have shown that RNAi, delivered as an expression plasmid, is able to inhibit all steps of HBV replication (91). In transgenic mice, RNAi expression has been shown to significantly reduce the secretion of HBsAg in serum, reduce both HBV mRNAs and genomic DNA in the liver, and eliminate hepatocytes stained positive for core antigen (92). These mouse studies have been extended to a chronically infected chimpanzee (93). Currently, a phase 2 placebo-controlled dose-escalation study with the DPC-NAG-ARC-520 formulation has been initiated in HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B whose viremia was controlled by entecavir and showed a 50% drop in HBsAg levels in the treated compared to placebo patients (94). Another RNAi platform has demonstrated similar success in its pre-clinical evaluation with a 2.3-log10 reduction in HBsAg in chronically HBV-infected chimpanzees (Alnylam’s company press release). Other RNAi-based regimens are currently being developed and tested (Table 1).

Inhibitors of HBV cccDNA Formation and Stability

Because the cytoplasmic nucleocapsid DNA is the precursor for cccDNA biosynthesis, complete inhibition of viral DNA replication in the nucleocapsids with polymerase inhibitors should preclude de novo cccDNA formation. However, clinical studies demonstrated that although NRTI monotherapy for 48–52 weeks reduced circulating viremia by ~5 log10 and cytoplasmic HBV DNA levels in the hepatocytes by approximately 2 log10, reduction of cccDNA was much less pronounced, only by 0.11 to 1.0 log10 (24, 95). Moreover, sequential analyses of viral DNA replicative intermediates and core antigen-positive hepatocytes in the livers of woodchuck hepatitis virus (WHV)-infected woodchucks before and during clevudine (a NRTI) therapy revealed that after more than 6 weeks of therapy, all WHV DNA replicative intermediates were markedly reduced, with the exception of cccDNA, which remained as the predominant viral DNA species in the liver (96).

Concerning the failure of prolonged NRTI therapy to eradicate cccDNA, one possibility is that the currently available NRTIs do not completely inhibit viral DNA synthesis in every infected hepatocyte in vivo, allowing for continuous replenishment of cccDNA pool via the intracellular amplification pathway. NRTIs are pro-drugs requiring activation by host cellular nucleoside kinases, the expression and function of which may be heterogeneous in the liver. Therefore hepatocytes may have varying abilities to activate the NRTIs, resulting in incomplete inhibition of HBV DNA replication. Emergence of drug-resistance mutations during apparently effective NRTI therapy suggests that residual HBV replication and de novo cccDNA synthesis still occurs at a low level (97).

Alternatively, failure to eradicate cccDNA by prolonged NRTI therapy may also be due to the extraordinary stability of cccDNA (98). cccDNA may persist in a “latent” state amidst the host chromosomes and remain as a reservoir for later HBV replication. Healthy hepatocytes in the absence of immune response or inflammatory reaction have a half-life of over 6 months (99, 100).

What we have learned from NRTI therapy is that eradication of cccDNA is essential for the cure of chronic hepatitis B. Combination therapies with NRTIs and one or multiple novel antiviral drugs targeting different steps of HBV replication may completely inhibit HBV DNA replication and thus accelerate the reduction of cccDNA. The other approach would be to directly purge the pre-existing cccDNA or permanently silence cccDNA transcription.

Recent strategy to cleave cccDNA molecules or inhibit its transcription by generating cccDNA sequence-specific endonucleases with zinc-finger nuclease, transcription activator-like effector nuclease or CRISPR/cas9 technology has been tested in cell culture or mouse model (101, 102) but efficient and targeted delivery of these antiviral genes to all HBV-infected cells in vivo is a major challenge for clinical application. Another approach is to target the other enzymatic function of HBV polymerase, RNaseH, which is required for HBV replication and cccDNA formation. Recent studies have identified potential inhibitors of HBV RNaseH (103).

Further understanding the molecular mechanism of cccDNA metabolism and functional regulation is essential for identifying and validating molecular targets for rational development of antiviral drugs to eradicate or transcriptionally silence cccDNA. As discussed above, recent studies on the molecular mechanism of immune control of HBV infection by IFN-α demonstrated that cccDNA can be specifically targeted for degradation by a cytidine-deamination mechanism (35) and its transcription can be silenced by epigenetic modification (33, 104). These findings raise a potentially exciting possibility of targeting cccDNA via pharmacological activation or augmentation of the host intrinsic antiviral pathways. Moreover, investigation into the role and mechanism of HBx and core protein in cccDNA metabolism and function may reveal viral-host interactions for selective elimination or silencing of cccDNA (20).

Additional efforts have been made to discover cccDNA-targeting compounds via high-throughput cell-based phenotypic screening. This unbiased approach, while attractive, is currently hampered by a lack of efficient HBV infection cell culture systems and convenient assays for high-throughput quantification of HBV replication and cccDNA quantification. Di-substituted sulfonamides had been identified as cccDNA formation inhibitors in a screen of 85,000 small molecular compounds (105). The recent rapid progress in the establishment of efficient HBV infection cell culture system may ultimately allow the development of cell-based assays for high-throughput screening of cccDNA-targeting antivirals.

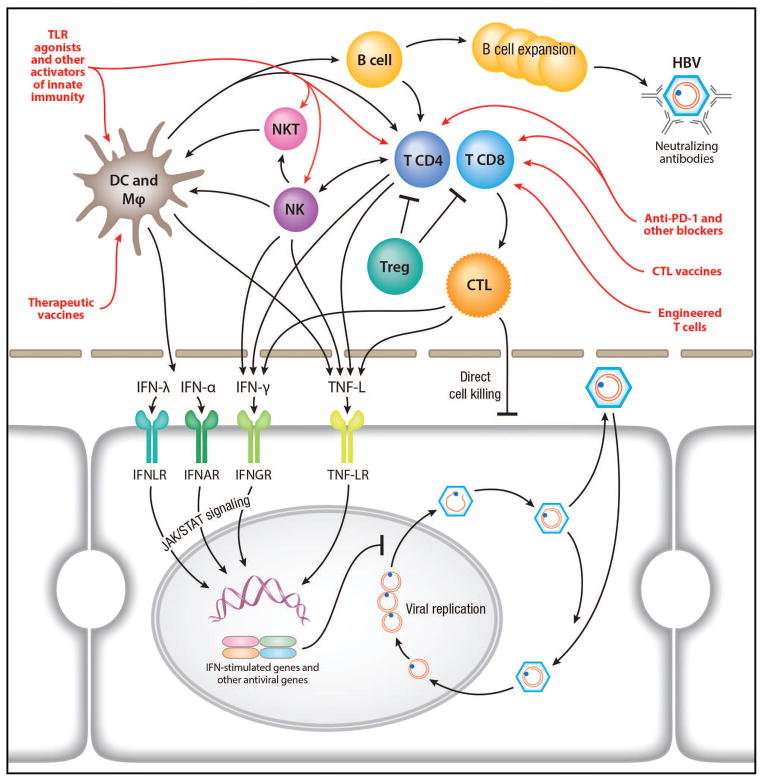

Immune Mechanisms of HBV Control and Implications for Therapy

The pathogenesis of chronic HBV infection involves not only viral mechanisms by which HBV establishes a persistent infection, but also the host responses to infection. The latter includes the response of hepatocytes to HBV infection as well as the interplay of the virus and infected cells with the other parenchymal and non-parenchymal cells in the liver, i.e. Kupffer cells, endothelial cells, fibroblasts, and non-resident immune cells that are recruited to the site of infection. HBV has evolved mechanisms to counteract and escape these different host responses to establish a chronic infection. Recent studies point out a critical role of the liver microenvironment in the elimination or control of HBV (106, 107) (Figure 2). While much has been learned about the HBV-specific adaptive immunity, the early and innate immune response during acute HBV infection remains largely unknown. In addition, few studies have examined intrahepatic immune responses in patients with chronic HBV infection. Available data suggest impaired responses but the mechanism of this impairment is unclear (107).

Figure 2.

Innate and adaptive HBV-specific immune responses and immune-based therapeutic development. Immune cells involved in innate and adaptive immune responses activated by HBV infection and their mechanisms of antiviral actions are shown. They are virus-specific CD8+ T cells that inhibit viral replication by both direct killing of infected hepatocytes and cytokine-mediated antiviral mechanisms; virus-specific CD4+ T cells, which provide essential help for CD8+ T-cell priming and effector functions as well as antiviral cytokines; regulatory T cells, which suppress virus-specific T-cell functions; B cells, which mature to plasma cells producing neutralizing antibodies and potentially participate in antigen presentation; NK cells, which display antiviral but also regulatory activity by eliminating activated virus-specific CD8+ T cells ; NK-T cells that sense viral-infected hepatocytes, produce antiviral cytokines and activate adaptive immune responses; other immune cells in the liver that play important roles in the activation and coordination of the innate and adaptive responses such as Kupffer cells, myeloid and plasmacytoid dendritic cells. TNF-L: TNF-like molecules, e.g., lymphotoxin-β. Therapeutic approaches designed to activate various pathways of the innate and adaptive immunities are illustrated in red. See text for details of these approaches.

In chronic hepatitis B, the antiviral B and T cell responses are quantitatively and/or qualitatively defective. For example, anti-HBsAb is generally undetectable in the setting of excess circulating HBsAg. Furthermore, antiviral T cells show impaired antiviral effector function in vitro. However, this host immune response, despite being dysfunctional, exerts at least partial viral control in vivo since immune suppression with immunosuppressive therapies result in increased viremia (58, 108). HBV persistence with antiviral immune dysfunction is also associated with the induction of immune inhibitory pathways including PD-1, CTLA-4, Bim, arginase and FoxP3+ Tregs (109–114). These pathways, likely induced in response to continued inflammation, viral replication and antigen expression, can dampen both cytopathic inflammatory responses as well as non-cytopathic antiviral effector functions. Thus, the antiviral effector T cell function may be enhanced by blocking one or more of these inhibitory pathways (111, 115), raising the possibility for potential therapeutic application in chronic viral infections such as chronic hepatitis B.

Based on our knowledge of the immune mechanisms of chronic HBV infection, several approaches to restore innate or adaptive immunity or both to control HBV infection in combination with other direct antiviral strategies have been applied (106, 107). These approaches can be broadly divided into viral-nonspecific and – specific modalities. The first involves general immunomodulatory agents and the latter aims to activate HBV-specific immune response by applying the technologies of therapeutic vaccination. As discussed above, the efficacy of interferon-α therapy can be partly attributed to its immunostimulatory effect. A promising approach emerges from the field of Toll-Like Receptors (TLRs). Various TLR agonists with potent immunostimulatory effects have been developed (116). Their administration to HBV patients leads to both intra- and extra-hepatic induction of type I interferons and other cytokines that may contribute directly to antiviral activity or indirectly result in activation of innate and adaptive immune responses. The second approach involves the blockade of negative immunoregulatory pathways (i.e. co-inhibitory signals, inhibitory cytokines, Treg cells), which may induce a partial restoration of HBV-specific T cell. Third, engineering of redirected T cells may result in a de novo reconstitution of functionally active HBV-specific T cells and activation of heterologous T cells. Whether inhibition of suppressive effect(s) of HBV can lead to restoration of HBV-specific innate and adaptive immune responses remains a challenging question. Several lines of evidence suggest that HBV interferes negatively with these host immune responses. A more detailed understanding of the specific mechanisms is mandatory before new ways of restoring immune responses by targeting virus-specific factors can be explored. HBV-specific strategies may prove more effective and safer than virus-nonspecific approaches.

A concern of the various immunotherapies is the potential risk of auto-immunity and/or exacerbation of liver damage by immune-mediated death of hepatocytes in vivo. Careful consideration of benefit versus risk and close clinical monitoring would be needed in these approaches.

HBV-nonspecific Immunomodulatory Agents

Toll-like receptor agonists

The antiviral effect of TLR agonists, particularly TLR-7, via activation of innate immunity has been evaluated in HBV chronically infected chimpanzees and woodchucks. Upon stimulation of TLR-7, pDCs produce IFN-α and other cytokines/chemokines and induce the activation of NK cells and activation of cytotoxic lymphocytes, thereby orchestrating both innate and adaptive immune responses (117). The altered responsiveness of pDCs may contribute to the reduced innate and adaptive immune responses during chronic viral infections. Agonist-induced activation of TLR-7 therefore represents a novel approach for the treatment of chronic viral infections (118). GS-9620, an orally administered agonist of TLR-7, was tested in HBV-infected chimpanzees (119). Short-term administration of the TLR-7 agonist provided long-term suppression of serum and liver HBV DNA. Serum levels of HBsAg and HBeAg, and numbers of HBV antigen-positive hepatocytes, were reduced. In parallel, GS-9620 administration induced the production of IFN-α and other cytokines and chemokines, up-regulated ISGs expression, and activated NK cells and lymphocyte subsets, confirming the activation of TLR-7 signaling. Similar effects were also observed in chronically infected woodchucks. Phase I clinical evaluation was performed and patients are now being enrolled in a phase II trial combining tenofovir and GS-9620 in comparison to tenofovir monotherapy (120).

PD1 and other co-inhibitory blockers

In chronic HBV infection, loss of viral control has been explained by exhausted T-cells. One approach would be to recover existing T-cells by correcting the balance between co-inhibitory (PD1, CTLA-4, Tim-3, Lag-3) and co-stimulating signals (41BB, IL-12) (121). Recent studies in the field of cancer therapy have highlighted the clinical relevance of PD1 blockade to restore anti-tumor immunity to improve survival (122). As chronic HBV infection and tumor immunology share similar characteristics in terms of immune subversion and the role of PD1, PD1 blockade may be an attractive concept for HBV therapy. A recent study in chronically infected woodchucks tested the combination therapy of entecavir and an anti-PD1 ligand monoclonal antibody together with a WHV DNA vaccine. PD1 blockade was shown to synergize with entecavir and therapeutic vaccination to control viral replication and restore WHV-specific T cell responses (123).

HBV-Specific Modified T Cells

As discussed above, HBV-specific T cells are either exhausted or nonresponsive in chronic HBV infection. This therapeutic approach is designed to provide genetically engineered T cells to target and eliminate HBV-infected hepatocytes. The strategy to genetically modify patient’s T cells to express HBV-specific T cell receptors (TCRs) and then infuse them into the same patients with HBV-associated HCC showed some promise (124, 125). But the variable and MHC-restricted nature of the interaction between TCR and its ligand and the skepticism that whether one or two such modified T cells would be sufficient to mount an effective T cell-based immune response may limit the clinical application of this approach. The recent emerging technology of “chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)” in the field of cancer therapeutics has been extended to treatment of persistent viral infections (126). The CAR approach is to generate a chimeric receptor expressing an extracellular target-binding domain, a hinge and membrane-anchoring region, and one or more intracellular signaling domain (126). The target-binding domain is derived from the light and heavy chain sequences of a single chain variable fragment (scFv) of the immunoglobulin. In the case of HBV, the target could be the cell-surface form of HBsAg and the single-chain variable fragment derived from a construct with high-affinity anti-HBs activity (127). The binding of the CAR-modified T cells to HBV-infected hepatocytes can trigger proliferating or activating signals to initiate an effective anti-HBV T-cell response. This strategy has been applied to HBV animal models with some promise (128). It remains to be seen whether CAR-modified T cells can achieve a broadly acting and potent anti-HBV response that is sufficient for viral clearance in chronic HBV-infected patients.

Therapeutic Vaccines

The goal for therapeutic vaccination in chronic hepatitis B is to induce sufficient anti-HBV immune responses to eliminate and/or cure infected hepatocytes without undue host cell damage, prevent viral spread to new hepatocytes and promote long-term viral control. These approaches leverage our accumulating knowledge in the adaptive immune responses of HBV infection and focus on restoring or activating endogenous HBV-specific immune responses that initially targeted HBsAg and later expanded to other HBV antigens by using recombinant proteins, CTL epitope vaccine, viral vectors and DNA vaccination. These vaccines are being combined with antiviral drugs and immune modulators to maximize their effects. An intriguing strategy to personalize antigen presentation to induce anti-HBV immune response involving monocytes has been recently proposed (129).

HBsAg-based vaccine

Since HBsAg-based prophylactic vaccine can induce protective virus-neutralizing antibodies, the initial studies involved the use of HBsAg in small trials, with some virological and serological responses in some patients (130, 131). Combination of an HBsAg vaccine with lamivudine showed promise initially in smaller studies (132). However, no difference in clinical efficacy was shown between vaccinated and control groups despite the induction of vigorous HBsAg-specific cellular and humoral immune responses in a large open-labeled randomized controlled trial of HBV patients receiving 12 doses of rHBsAg and ASO2 adjuvant with 52 weeks of lamivudine (133). Similarly, the use of yeast-derived rHBsAg and Hepatitis B Immune Globulin immune complex showed promise in a phase I/II study (134) that was not reproduced in a larger Phase III study (135).

CTL epitope vaccine

Immunization with recombinant proteins (e.g. HBsAg) can promote antibody and CD4 helper T cell responses, but generally not CD8 T cells, which require endogenously processed viral peptides. Given the relevance of antiviral CD8 T cells in HBV clearance, direct augmentation of HBV-specific CD8 T cells was attempted in a pilot study using a lipopeptide encoding a single immunogenic HLA A2-restricted HBV core 18–27 CTL epitope (136). Despite their immunogenicity in healthy adults, this epitope vaccine was not immunogenic in patients with chronic hepatitis B and did not significantly change the HBV DNA titers or HBeAg status. Inclusion of other epitopes in this approach may be necessary.

DNA vaccination with or without immunomodulators

DNA vaccination can promote antiviral CD8 T cell as well as CD4 T cell and antibody responses (137). In this regard, intramuscular injection of DNA encoding only preS2/S was safe, well-tolerated and at least transiently immunogenic but only marginally effective in reducing HBV DNA levels in a Phase I study of chronic hepatitis B patients who did not respond to IFN-α and/or lamivudine (138, 139). It also did not prevent viremic relapse in a Phase I/II ANRS HB02 VAC-AND trial (139). Another Phase I study using plasmid DNA encoding all HBV open reading frames and human IL-12 in addition to daily lamivudine, showed a 50% HBV DNA suppression at 1 year post-treatment cessation (140). However, in a subsequent larger study, a related HBV plasmid DNA (all HBV ORFs except HBx) and human IL-12 with daily adefovir showed only a tendency for greater HBeAg loss and HBV DNA suppression compared to adefovir alone (141).

Other Therapeutic Vaccine Trials

Currently open therapeutic HBV vaccine trials on clinicaltrials.gov (as of May 2015) include: 1) GS4774, a heat-killed recombinant yeast expressing HBV S, core and HBx fusion protein (142); 2) ABX203 with recombinant HBsAg and HBcAg in the setting of PEG IFN-α and oral antivirals; 3) INO-1800, a multi-antigen DNA vaccine encoding HBsAg and HBcAg electroporated alone or combined with INO-9112 encoding IL-12 in patients on either entecavir or tenofovir; 4) TG1050, a non-replicative E1/E3-deleted human adenovirus encoding a fusion protein combining modified HBV Core, Polymerase and Envelope (143); 5) HBV vaccine with HBIG and GM-CSF; 6) HBV vaccine with IFN-α2b and IL-2; 7) HB-Vac activated dendritic cells combined with PEG IFN-α or NUCs; 8) intensified Euvax (HBV S) vaccination with PEG IFN-α.

Therapeutic Pipeline and Conclusion

Based on the literature, expert input, publicly disclosed information of various pharmaceutical companies, clinicaltrial.gov website, we generated a table summarizing the current status of various anti-HBV drugs or biologics in the development pipeline (Table 1). While many of them are still in preclinical development, several have advanced to clinical trials. As discussed above, some of them showed early promise and will likely advance to the late clinical trial phase for more definitive proof of the preliminary success. In this review, we have summarized the major therapeutic approaches and novel molecular targets for anti-HBV drug development, and provided a knowledge-based rationale behind these various strategies. It is possible that new and additional technologies may emerge as the field advances. To achieve a more sustained and effective control of HBV infection, a combination of the existing HBV therapies and one or more of the above modalities, either small-molecule drugs or biologics, will be necessary. With the concerted efforts of private and public sectors, the next milestone in the therapy of HBV infection – a functional “cure” that has remained elusive - is likely within our grasp within the next decade.

References

- 1.Ott JJ, Stevens GA, Groeger J, Wiersma ST. Global epidemiology of hepatitis B virus infection: new estimates of age-specific HBsAg seroprevalence and endemicity. Vaccine. 2012;30:2212–2219. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.12.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kennedy PT, Sandalova E, Jo J, Gill U, Ushiro-Lumb I, Tan AT, Naik S, et al. Preserved T-cell function in children and young adults with immune-tolerant chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:637–645. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vanwolleghem T, Hou J, van Oord G, Andeweg AC, Osterhaus AD, Pas SD, Janssen HL, et al. Re-evaluation of hepatitis B virus clinical phases by systems biology identifies unappreciated roles for the innate immune response and B cells. Hepatology. 2015 doi: 10.1002/hep.27805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McMahon BJ. The natural history of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Hepatology. 2009;49:S45–55. doi: 10.1002/hep.22898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prati D, Taioli E, Zanella A, Della Torre E, Butelli S, Del Vecchio E, Vianello L, et al. Updated definitions of healthy ranges for serum alanine aminotransferase levels. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:1–10. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-1-200207020-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schulze A, Gripon P, Urban S. Hepatitis B virus infection initiates with a large surface protein-dependent binding to heparan sulfate proteoglycans. Hepatology. 2007;46:1759–1768. doi: 10.1002/hep.21896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Salisse J, Sureau C. A function essential to viral entry underlies the hepatitis B virus “a” determinant. J Virol. 2009;83:9321–9328. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00678-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yan H, Zhong G, Xu G, He W, Jing Z, Gao Z, Huang Y, et al. Sodium taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide is a functional receptor for human hepatitis B and D virus. Elife. 2014;3 doi: 10.7554/eLife.00049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doring B, Lutteke T, Geyer J, Petzinger E. The SLC10 carrier family: transport functions and molecular structure. Curr Top Membr. 2012;70:105–168. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-394316-3.00004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schieck A, Schulze A, Gahler C, Muller T, Haberkorn U, Alexandrov A, Urban S, et al. Hepatitis B virus hepatotropism is mediated by specific receptor recognition in the liver and not restricted to susceptible hosts. Hepatology. 2013;58:43–53. doi: 10.1002/hep.26211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Urban S, Bartenschlager R, Kubitz R, Zoulim F. Strategies to inhibit entry of HBV and HDV into hepatocytes. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:48–64. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ni Y, Lempp FA, Mehrle S, Nkongolo S, Kaufman C, Falth M, Stindt J, et al. Hepatitis B and D viruses exploit sodium taurocholate co-transporting polypeptide for species-specific entry into hepatocytes. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:1070–1083. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yan H, Peng B, He W, Zhong G, Qi Y, Ren B, Gao Z, et al. Molecular determinants of hepatitis B and D virus entry restriction in mouse sodium taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide. Journal of virology. 2013;87:7977–7991. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03540-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang HC, Chen CC, Chang WC, Tao MH, Huang C. Entry of hepatitis B virus into immortalized human primary hepatocytes by clathrin-dependent endocytosis. J Virol. 2012;86:9443–9453. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00873-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Macovei A, Radulescu C, Lazar C, Petrescu S, Durantel D, Dwek RA, Zitzmann N, et al. Hepatitis B virus requires intact caveolin-1 function for productive infection in HepaRG cells. J Virol. 2010;84:243–253. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01207-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schmitz A, Schwarz A, Foss M, Zhou L, Rabe B, Hoellenriegel J, Stoeber M, et al. Nucleoporin 153 arrests the nuclear import of hepatitis B virus capsids in the nuclear basket. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000741. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koniger C, Wingert I, Marsmann M, Rosler C, Beck J, Nassal M. Involvement of the host DNA-repair enzyme TDP2 in formation of the covalently closed circular DNA persistence reservoir of hepatitis B viruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:E4244–4253. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1409986111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bock CT, Schwinn S, Locarnini S, Fyfe J, Manns MP, Trautwein C, Zentgraf H. Structural organization of the hepatitis B virus minichromosome. J Mol Biol. 2001;307:183–196. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pollicino T, Belloni L, Raffa G, Pediconi N, Squadrito G, Raimondo G, Levrero M. Hepatitis B virus replication is regulated by the acetylation status of hepatitis B virus cccDNA-bound H3 and H4 histones. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:823–837. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Belloni L, Pollicino T, De Nicola F, Guerrieri F, Raffa G, Fanciulli M, Raimondo G, et al. Nuclear HBx binds the HBV minichromosome and modifies the epigenetic regulation of cccDNA function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:19975–19979. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908365106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lucifora J, Arzberger S, Durantel D, Belloni L, Strubin M, Levrero M, Zoulim F, et al. Hepatitis B virus X protein is essential to initiate and maintain virus replication after infection. J Hepatol. 2011;55:996–1003. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Watanabe T, Sorensen EM, Naito A, Schott M, Kim S, Ahlquist P. Involvement of host cellular multivesicular body functions in hepatitis B virus budding. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:10205–10210. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704000104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lentz TB, Loeb DD. Roles of the envelope proteins in the amplification of covalently closed circular DNA and completion of synthesis of the plus-strand DNA in hepatitis B virus. J Virol. 2011;85:11916–11927. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05373-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Werle-Lapostolle B, Bowden S, Locarnini S, Wursthorn K, Petersen J, Lau G, Trepo C, et al. Persistence of cccDNA during the natural history of chronic hepatitis B and decline during adefovir dipivoxil therapy. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1750–1758. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lok AS, McMahon BJ. Chronic hepatitis B: update 2009. Hepatology. 2009;50:661–662. doi: 10.1002/hep.23190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.European Association for the Study of the L. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: management of hepatitis C virus infection. J Hepatol. 2011;55:245–264. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liaw YF, Leung N, Kao JH, Piratvisuth T, Gane E, Han KH, Guan R, et al. Asian-Pacific consensus statement on the management of chronic hepatitis B: a 2008 update. Hepatology international. 2008;2:263–283. doi: 10.1007/s12072-008-9080-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu C, Guo H, Pan XB, Mao R, Yu W, Xu X, Wei L, et al. Interferons accelerate decay of replication-competent nucleocapsids of hepatitis B virus. J Virol. 2010;84:9332–9340. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00918-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hao J, Jin W, Li X, Wang S, Zhang X, Fan H, Li C, et al. Inhibition of alpha interferon (IFN-alpha)-induced microRNA-122 negatively affects the anti-hepatitis B virus efficiency of IFN-alpha. J Virol. 2013;87:137–147. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01710-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Micco L, Peppa D, Loggi E, Schurich A, Jefferson L, Cursaro C, Panno AM, et al. Differential boosting of innate and adaptive antiviral responses during pegylated-interferon-alpha therapy of chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol. 2013;58:225–233. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.ter Borg MJ, Hansen BE, Herrmann E, Zeuzem S, Cakaloglu Y, Karayalcin S, Flisiak R, et al. Modelling of early viral kinetics and pegylated interferon-alpha2b pharmacokinetics in patients with HBeag-positive chronic hepatitis B. Antivir Ther. 2007;12:1285–1294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sadler AJ, Williams BR. Interferon-inducible antiviral effectors. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:559–568. doi: 10.1038/nri2314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Belloni L, Allweiss L, Guerrieri F, Pediconi N, Volz T, Pollicino T, Petersen J, et al. IFN-alpha inhibits HBV transcription and replication in cell culture and in humanized mice by targeting the epigenetic regulation of the nuclear cccDNA minichromosome. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:529–537. doi: 10.1172/JCI58847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gripon P, Rumin S, Urban S, Le Seyec J, Glaise D, Cannie I, Guyomard C, et al. Infection of a human hepatoma cell line by hepatitis B virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:15655–15660. doi: 10.1073/pnas.232137699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lucifora J, Xia Y, Reisinger F, Zhang K, Stadler D, Cheng X, Sprinzl MF, et al. Specific and nonhepatotoxic degradation of nuclear hepatitis B virus cccDNA. Science. 2014;343:1221–1228. doi: 10.1126/science.1243462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stenglein MD, Burns MB, Li M, Lengyel J, Harris RS. APOBEC3 proteins mediate the clearance of foreign DNA from human cells. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:222–229. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liang G, Kitamura K, Wang Z, Liu G, Chowdhury S, Fu W, Koura M, et al. RNA editing of hepatitis B virus transcripts by activation-induced cytidine deaminase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:2246–2251. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1221921110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Noguchi C, Hiraga N, Mori N, Tsuge M, Imamura M, Takahashi S, Fujimoto Y, et al. Dual effect of APOBEC3G on Hepatitis B virus. J Gen Virol. 2007;88:432–440. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.82319-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Renard M, Henry M, Guetard D, Vartanian JP, Wain-Hobson S. APOBEC1 and APOBEC3 cytidine deaminases as restriction factors for hepadnaviral genomes in non-humans in vivo. J Mol Biol. 2010;400:323–334. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Turelli P, Mangeat B, Jost S, Vianin S, Trono D. Inhibition of hepatitis B virus replication by APOBEC3G. Science. 2004;303:1829. doi: 10.1126/science.1092066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guidotti LG, Chisari FV. Immunobiology and pathogenesis of viral hepatitis. Annu Rev Pathol. 2006;1:23–61. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.1.110304.100230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yapali S, Talaat N, Lok AS. Management of hepatitis B: our practice and how it relates to the guidelines. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:16–26. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marcellin P, Ahn SA, Ma X, Caruntu FA, Tak WY, et al. HBsAg Loss With Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate Plus Peginterferon Alfa-2a in Chronic Hepatitis B: Results of a Global Randomized Controlled Trial. Hepatology. 2014;60:294A. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chotiyaputta W, Peterson C, Ditah FA, Goodwin D, Lok AS. Persistence and adherence to nucleos(t)ide analogue treatment for chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol. 2011;54:12–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liaw YF, Sung JJ, Chow WC, Farrell G, Lee CZ, Yuen H, Tanwandee T, et al. Lamivudine for patients with chronic hepatitis B and advanced liver disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1521–1531. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa033364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Marcellin P, Gane E, Buti M, Afdhal N, Sievert W, Jacobson IM, Washington MK, et al. Regression of cirrhosis during treatment with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for chronic hepatitis B: a 5-year open-label follow-up study. Lancet. 2013;381:468–475. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61425-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Menendez-Arias L, Alvarez M, Pacheco B. Nucleoside/nucleotide analog inhibitors of hepatitis B virus polymerase: mechanism of action and resistance. Curr Opin Virol. 2014;8:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2014.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zoulim F, Mason WS. Reasons to consider earlier treatment of chronic HBV infections. Gut. 2012;61:333–336. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chan HL, Chan CK, Hui AJ, Chan S, Poordad F, Chang TT, Mathurin P, et al. Effects of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate in hepatitis B e antigen-positive patients with normal levels of alanine aminotransferase and high levels of hepatitis B virus DNA. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:1240–1248. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lok AS, Trinh H, Carosi G, Akarca US, Gadano A, Habersetzer F, Sievert W, et al. Efficacy of entecavir with or without tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for nucleos(t)ide-naive patients with chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:619–628. e611. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.05.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lau GK, Piratvisuth T, Luo KX, Marcellin P, Thongsawat S, Cooksley G, Gane E, et al. Peginterferon Alfa-2a, lamivudine, and the combination for HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B. The New England journal of medicine. 2005;352:2682–2695. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Marcellin P, Lau GK, Bonino F, Farci P, Hadziyannis S, Jin R, Lu ZM, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2a alone, lamivudine alone, and the two in combination in patients with HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B. The New England journal of medicine. 2004;351:1206–1217. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Su W, Hsu CW, Lee CM, Peng CY, Chuang Wl, et al. Combination therapy with peginterferon alfa-2a and a nucleos(t)ide analogue for HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B patients: results of a large, randomised, multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Hepatol. 2014;60:S47. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ning Q, Han M, Sun Y, Jiang J, Tan D, Hou J, Tang H, et al. Switching from entecavir to PegIFN alfa-2a in patients with HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B: a randomised open-label trial (OSST trial) Journal of hepatology. 2014;61:777–784. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.05.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chan HL, Leung NW, Hui AY, Wong VW, Liew CT, Chim AM, Chan FK, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of combination therapy for chronic hepatitis B: comparing pegylated interferon-alpha2b and lamivudine with lamivudine alone. Annals of internal medicine. 2005;142:240–250. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-142-4-200502150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Thimme R, Dandri M. Dissecting the divergent effects of interferon-alpha on immune cells: time to rethink combination therapy in chronic hepatitis B? Journal of hepatology. 2013;58:205–209. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Brouwer WP, Xie Q, Sonneveld MJ, Zhang N, Zhang Q, Tabak F, Streinu A, et al. Adding peginterferon to entecavir for HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B: A multicentre randomized trial (ARES study) Hepatology. 2014 doi: 10.1002/hep.27586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Seto WK, Chan TS, Hwang YY, Wong DK, Fung J, Liu KS, Gill H, et al. Hepatitis B reactivation in patients with previous hepatitis B virus exposure undergoing rituximab-containing chemotherapy for lymphoma: a prospective study. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:3736–3743. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.56.7081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bourliere M, Rabiega P, Ganne-Carrie N, Serfaty L, Marcellin P, et al. HBsAg clearance after addition of 48 weeks of PEGIFN in HBeAg negative CHB patients on Nucleos(t)ide with undetactable HBV DNA for at leat one year: a multicenter randomized controlled pahse III trial ANRS-HB06 PEGAN study: preliminary findings. Hepatology. 2014;60:1094A. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Xie Q, Zhou H, Bai X, Wu S, Chen JJ, Sheng J, Xie Y, et al. A randomized, open-label clinical study of combined pegylated interferon Alfa-2a (40KD) and entecavir treatment for hepatitis B “e” antigen-positive chronic hepatitis B. Clinical infectious diseases. 2014;59:1714–1723. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vanderlinden E, Naesens L. Emerging antiviral strategies to interfere with influenza virus entry. Med Res Rev. 2014;34:301–339. doi: 10.1002/med.21289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Haqqani AA, Tilton JC. Entry inhibitors and their use in the treatment of HIV-1 infection. Antiviral Res. 2013;98:158–170. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2013.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Petersen J, Dandri M, Mier W, Lutgehetmann M, Volz T, von Weizsacker F, Haberkorn U, et al. Prevention of hepatitis B virus infection in vivo by entry inhibitors derived from the large envelope protein. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:335–341. doi: 10.1038/nbt1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Aspinall EJ, Hawkins G, Fraser A, Hutchinson SJ, Goldberg D. Hepatitis B prevention, diagnosis, treatment and care: a review. Occup Med (Lond) 2011;61:531–540. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqr136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Galun E, Eren R, Safadi R, Ashour Y, Terrault N, Keeffe EB, Matot E, et al. Clinical evaluation (phase I) of a combination of two human monoclonal antibodies to HBV: safety and antiviral properties. Hepatology. 2002;35:673–679. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.31867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mason WS, Xu C, Low HC, Saputelli J, Aldrich CE, Scougall C, Grosse A, et al. The amount of hepatocyte turnover that occurred during resolution of transient hepadnavirus infections was lower when virus replication was inhibited with entecavir. J Virol. 2009;83:1778–1789. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01587-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Blanchet M, Sureau C. Infectivity determinants of the hepatitis B virus pre-S domain are confined to the N-terminal 75 amino acid residues. Journal of virology. 2007;81:5841–5849. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00096-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gripon P, Le Seyec J, Rumin S, Guguen-Guillouzo C. Myristylation of the hepatitis B virus large surface protein is essential for viral infectivity. Virology. 1995;213:292–299. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.0002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lucifora J, Esser K, Protzer U. Ezetimibe blocks hepatitis B virus infection after virus uptake into hepatocytes. Antiviral Res. 2013;97:195–197. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2012.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nkongolo S, Ni Y, Lempp FA, Kaufman C, Lindner T, Esser-Nobis K, Lohmann V, et al. Cyclosporin A inhibits hepatitis B and hepatitis D virus entry by cyclophilin-independent interference with the NTCP receptor. J Hepatol. 2014;60:723–731. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Watashi K, Sluder A, Daito T, Matsunaga S, Ryo A, Nagamori S, Iwamoto M, et al. Cyclosporin A and its analogs inhibit hepatitis B virus entry into cultured hepatocytes through targeting a membrane transporter, sodium taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide (NTCP) Hepatology. 2014;59:1726–1737. doi: 10.1002/hep.26982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Vaz FM, Paulusma CC, Huidekoper H, de Ru M, Lim C, Koster J, Ho-Mok K, et al. Sodium taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide (SLC10A1) deficiency: conjugated hypercholanemia without a clear clinical phenotype. Hepatology. 2015;61:260–267. doi: 10.1002/hep.27240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Slijepcevic D, Kaufman C, Wichers CG, Gilglioni EH, Lempp FA, Duijst S, de Waart DR, et al. Impaired uptake of conjugated bile acids and Hepatitis B Virus preS1-binding in Na -taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide knockout mice. Hepatology. 2015 doi: 10.1002/hep.27694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bogomolov P, Voronkova N, Allweiss L, Dandri M, Schwab M, Lempp FA, Haag M, et al. Hepatology. Vol. 2014. WILEY-BLACKWELL; 111 RIVER ST, HOBOKEN 07030-5774, NJ USA: 2014. A proof-of-concept Phase 2a clinical trial with HBV/HDV entry inhibitor Myrcludex B; pp. 1279A–1280A. [Google Scholar]

- 75.King RW, Ladner SK, Miller TJ, Zaifert K, Perni RB, Conway SC, Otto MJ. Inhibition of human hepatitis B virus replication by AT-61, a phenylpropenamide derivative, alone and in combination with (−)beta-L-2′,3′-dideoxy-3′-thiacytidine. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:3179–3186. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.12.3179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Feld JJ, Colledge D, Sozzi V, Edwards R, Littlejohn M, Locarnini SA. The phenylpropenamide derivative AT-130 blocks HBV replication at the level of viral RNA packaging. Antiviral Res. 2007;76:168–177. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2007.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Delaney WEt, Edwards R, Colledge D, Shaw T, Furman P, Painter G, Locarnini S. Phenylpropenamide derivatives AT-61 and AT-130 inhibit replication of wild-type and lamivudine-resistant strains of hepatitis B virus in vitro. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46:3057–3060. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.9.3057-3060.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Billioud G, Pichoud C, Puerstinger G, Neyts J, Zoulim F. The main hepatitis B virus (HBV) mutants resistant to nucleoside analogs are susceptible in vitro to non-nucleoside inhibitors of HBV replication. Antiviral Res. 2011;92:271–276. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2011.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Katen SP, Tan Z, Chirapu SR, Finn MG, Zlotnick A. Assembly-directed antivirals differentially bind quasiequivalent pockets to modify hepatitis B virus capsid tertiary and quaternary structure. Structure. 2013;21:1406–1416. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2013.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Deres K, Schroder CH, Paessens A, Goldmann S, Hacker HJ, Weber O, Kramer T, et al. Inhibition of hepatitis B virus replication by drug-induced depletion of nucleocapsids. Science. 2003;299:893–896. doi: 10.1126/science.1077215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Stray SJ, Bourne CR, Punna S, Lewis WG, Finn MG, Zlotnick A. A heteroaryldihydropyrimidine activates and can misdirect hepatitis B virus capsid assembly. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:8138–8143. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409732102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Stray SJ, Zlotnick A. BAY 41-4109 has multiple effects on Hepatitis B virus capsid assembly. J Mol Recognit. 2006;19:542–548. doi: 10.1002/jmr.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gane E, Schwabe C, Walker K, Flores L, Hartman G, Klumpp K, Liaw S, et al. Phase 1a Safety and Pharmacokinetics of NVR 3-778, a Potential First-In-Class HBV Core Inhibitor. Hepatology. 2014;60:1267A–1290A . [LB-1219. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Prange R. Host factors involved in hepatitis B virus maturation, assembly, and egress. Med Microbiol Immunol. 2012;201:449–461. doi: 10.1007/s00430-012-0267-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Heermann KH, Goldmann U, Schwartz W, Seyffarth T, Baumgarten H, Gerlich WH. Large surface proteins of hepatitis B virus containing the pre-s sequence. J Virol. 1984;52:396–402. doi: 10.1128/jvi.52.2.396-402.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Xu Y, Hu Y, Shi B, Zhang X, Wang J, Zhang Z, Shen F, et al. HBsAg inhibits TLR9-mediated activation and IFN-alpha production in plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Mol Immunol. 2009;46:2640–2646. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2009.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Gehring AJ, Ann D’Angelo J. Dissecting the dendritic cell controversy in chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Cell Mol Immunol. 2015;12:283–291. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2014.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kapoor R, Kottilil S. Strategies to eliminate HBV infection. Future Virol. 2014;9:565–585. doi: 10.2217/fvl.14.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Blazquez LC, Fortes P. Harnessing RNAi for the Treatment of Viral Infections. In: Arbuthnot P, Weinberg MS, editors. Applied RNAi. Caister Academic Press; Norfolk, UK: 2014. pp. 151–180. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Chen Y, Cheng G, Mahato RI. RNAi for treating hepatitis B viral infection. Pharm Res. 2008;25:72–86. doi: 10.1007/s11095-007-9504-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Klein C, Bock CT, Wedemeyer H, Wustefeld T, Locarnini S, Dienes HP, Kubicka S, et al. Inhibition of hepatitis B virus replication in vivo by nucleoside analogues and siRNA. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:9–18. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00720-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.McCaffrey AP, Nakai H, Pandey K, Huang Z, Salazar FH, Xu H, Wieland SF, et al. Inhibition of hepatitis B virus in mice by RNA interference. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:639–644. doi: 10.1038/nbt824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lanford R, Wooddell CI, Chavez D, Oropeza CE, Chu Q, Hamilton HL, McLachlan A, et al. ARC-520 RNAi therapeutic reduces hepatitis B virus DNA, S antigen and e antigen in a chimpanzee with a very high viral titer. Hepatology. 2013;58 (S1):705A–730A. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Yuen M-F, Chan HL-Y, Given B, Hamilton J, Schluep T, Lewis DL, Lai C-L, et al. Phase II, dose ranging study of ARC-520, a siRNA-based therapeutic, in patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Hepatology. 2014;60:1267A–1290A. (LB-1221) [Google Scholar]

- 95.Sung JJ, Wong ML, Bowden S, Liew CT, Hui AY, Wong VW, Leung NW, et al. Intrahepatic hepatitis B virus covalently closed circular DNA can be a predictor of sustained response to therapy. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:1890–1897. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Zhu Y, Yamamoto T, Cullen J, Saputelli J, Aldrich CE, Miller DS, Litwin S, et al. Kinetics of hepadnavirus loss from the liver during inhibition of viral DNA synthesis. J Virol. 2001;75:311–322. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.1.311-322.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Zoulim F, Durantel D, Deny P. Management and prevention of drug resistance in chronic hepatitis B. Liver Int. 2009;29 (Suppl 1):108–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2008.01939.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Moraleda G, Saputelli J, Aldrich CE, Averett D, Condreay L, Mason WS. Lack of effect of antiviral therapy in nondividing hepatocyte cultures on the closed circular DNA of woodchuck hepatitis virus. J Virol. 1997;71:9392–9399. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.12.9392-9399.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.MacDonald RA. “Lifespan” of liver cells Autoradio-graphic study using tritiated thymidine in normal, cirrhotic, and partially hepatectomized rats. Arch Intern Med. 1961;107:335–343. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1961.03620030023003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Magami Y, Azuma T, Inokuchi H, Kokuno S, Moriyasu F, Kawai K, Hattori T. Cell proliferation and renewal of normal hepatocytes and bile duct cells in adult mouse liver. Liver. 2002;22:419–425. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0676.2002.01702.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]