Abstract

Purpose

We report five cases of optic neuropathy (ON) identified over a 2-year period within an island population of 140 000. These cases display characteristics possibly related to long-term treatment with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs).

Methods

Retrospective analysis of casenotes. Each case has been assessed using the Naranjo algorithm to indicate likelihood of adverse drug reaction (ADR).

Results

Clinical assessment and investigation confirmed ON in all cases with a vascular origin suspected. SSRI cessation may help protect the unaffected eye and in some cases recovery of vision seems possible. The Naranjo scores indicated possible ADR in four cases and probable ADR in one case.

Conclusions

In 2004, ~7% of the UK adult population was receiving SSRI treatment for a range of 4.8–7.7 years. The most common ophthalmic side effect is acute glaucoma. Currently, there remain no reports of SSRI associated ON, although papilloedema has been reported. A potential mechanism for ischaemic optic neuropathy (ION) has been described in relation to raised serotonin levels. A single case of central retinal vein occlusion exists along with reports of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and ischaemic stroke. We recommend a review of SSRI treatment in cases of acute ON.

Case reports

The following cases were diagnosed as optic neuropathy based on clinical history, physical signs, and following extensive investigation including MRI scan, CXR, FBC, U and E, serum B12, coagulopathies, autoimmune serology, ESR, CRP, serum ACE, fundus fluorescein angiography (FFA), optical coherence tomography, visual fields (VF), electroretinogram (ERG), and visual evoked potentials (VEPs). Leber's mutation and serology for lyme, syphilis and bartonella were also performed where appropriate. Each case has been assessed using the Naranjo algorithm to indicate likelihood of adverse drug reaction.1 Many additional components from the following case histories have also been summarised in Table 1.

Table 1. Summary of demographic and clinical data for cases 1–5.

| Age (years) | Sex | SSRI | Duration | Side | Clinical presentation | Vascular risk factors | Outcome | Naranjo score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1 | 54 | M | Sertraline Citalopram | 6 months 6 months | R+L | Anterior ION | Smoker | Partial recovery | 3 |

| Case 2 | 51 | F | Citalopram | 3 years | R+L | Posterior ION | NIDDM | No recovery | 3 |

| Case 3 | 54 | F | Fluoxetine | 5 years | R+L | Posterior ION | Smoker | Full recovery | 4 |

| Case 4 | 40 | F | Citalopram | 10 years | R | Posterior ION | — | No recovery | 5 |

| Case 5 | 47 | F | Paroxetine | 14 years | L | Posterior ION | NIDDM Smoker | No recovery | 3 |

Case 1

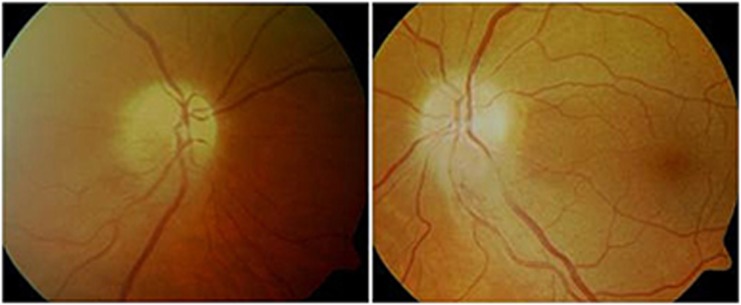

A 54-year-old male smoker presented with sudden bilateral loss of vision (LOV) associated with segmental disc swelling (Figure 1) and altitudinal VF defects. His snellen visual acuities (VAs) were 6/36 in both eyes. This was his second episode within 6 months. He had also recently suffered a DVT. This patient stopped the SSRI that he had been taking for 12 months. His vision at the final visit was stable.

Figure 1.

Colour disc photographs of Case 1 during acute presentation with segmental swelling.

Naranjo score of 3 indicating possible ADR.

Case 2

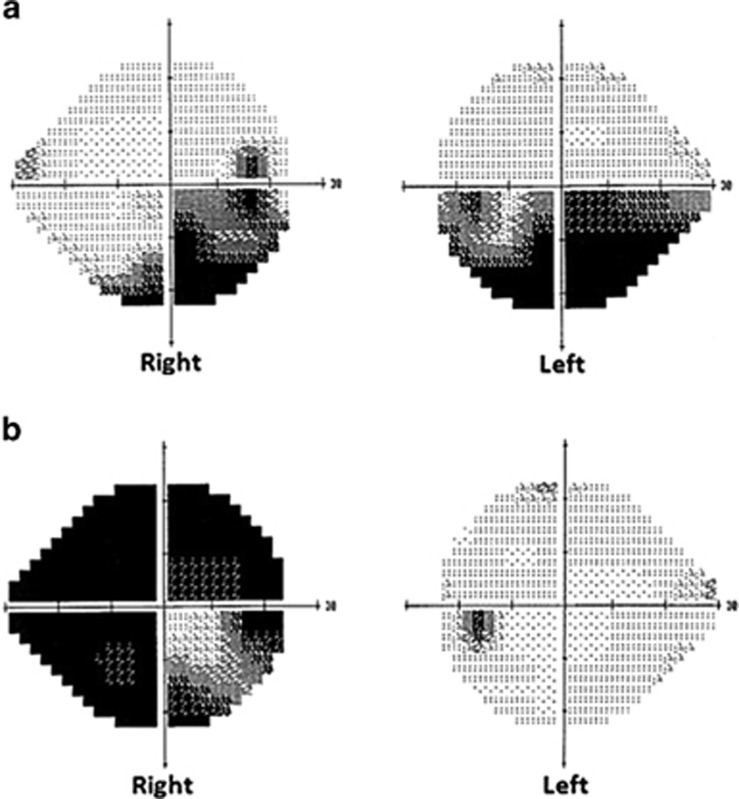

A 51-year-old NIDDM female presented with right temporal scotoma followed by gradual progressive inferior altitudinal VF loss (Figure 2a) and reduced VAs over 6 months to 6/18 in both eyes. She also developed a supranuclear vertical gaze palsy. The SSRI was stopped with resolution of her gaze palsy and stabilisation of VAs and VF.

Figure 2.

Visual fields demonstrating bilateral altitudinal defects in case 2 (a) and severe unilateral loss in case 4 (b).

Naranjo score of 3 indicating possible ADR.

Case 3

A 54-year-old female smoker experienced gradual LOV in both eyes, right VA 6/24 and left VA 6/60, associated with severe bilateral VF constriction. She was taking daily SSRI and quinine 300 mg for nocturnal cramps. Pattern VEPs were degraded and broadened on the left to smaller checks. The ERG was normal. These findings were inconsistent with demyelination, tobacco, or quinine amblyopia. This patient stopped the SSRI with subsequent improvement in visual function over 18 months to full VF and VAs R 6/5 and L 6/6.

Naranjo score of 4 indicating possible ADR.

Case 4

A 40-year-old female presented with sudden painless right LOV, no disc changes but RAPD and VA 1/60. VEPs indicated degraded and broadened waveforms to smaller checks but normal latency indicating post-retinal dysfunction (inconsistent with demyelination). The right temporal half field VEP was degraded consistent with the VF test. She stopped the SSRI that she had been taking for 10 years. Her left eye remained unaffected.

Naranjo score of 5 indicating probable ADR.

Case 5

A 47-year-old NIDDM female smoker presented with sudden left painless LOV and RAPD with normal disc appearance. She was followed for 6 months without recovery from hand movements vision. This patient had taken a daily SSRI for 14 years.

Naranjo score of 3 indicating possible ADR.

Discussion

In 2004, approximately 7% of UK adults were recieving SSRI treatment for a range of 4.8–7.7 years.2 Currently there are no reports of SSRI associated ON, although papilloedema has been reported.3 A potential mechanism for ION has been previously described in relation to raised serotonin levels.4, 5 A single case of central retinal vein occlusion exists along with reports of deep vein thrombosis and ischaemic stroke.6, 7, 8

Four out of five cases summarised in Table 1 presented with visual loss from suspected posterior ION (PION). Two cases experienced progressive bilateral VF loss, one altitudinal, the other severe constriction. Two cases presented with sudden severe unilateral LOV. All patients were relatively young with a long history of SSRI treatment. One patient had a typical appearance of bilateral simultaneous anterior ION (AION).

All the cases were able to stop SSRIs without any further deterioration (Table 1). One patient with bilateral progressive LOV recovered all of her vision over 18 months. Two patients with unilateral SLOV did not recover function in the affected eye but retained normal vision in the second eye.

A ‘non-arteritic' ischaemic origin was suspected in all cases. Toxicity was felt to be unlikely as three cases were of sudden onset. Toxic ON is typically characterised by central or cecocentral scotomas. In this series, two cases were unilateral and of those with bilateral involvement, two had altitudinal VF loss and one experienced constricted VF. AION (involving short posterior ciliary arteries) presents with optic disc swelling, often segmental and sudden, associated with altitudinal VF loss.9 The clinical features of PION (involving pial branches of central retinal artery) are typically normal disc appearance at the outset with acute, painless LOV in one or both eyes; however, in some cases it can be progressive.9 PION in young healthy patients is uncommon accounting for only 2.5% of cases.9, 10, 11 Systemic risk factors for ION include cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and hypertension.12

The ocular pharmacology of SSRIs and their potential vascular side effects have been published.4, 5 Costagliola et al described a mechanism for vasospasm in the optic nerve, postulating that increased plasma serotonin levels may be a factor, or a cofactor, in the development of optic nerve perfusion disorders. With long-term SSRI treatment it was suggested that multiple transient vasospasms could progressively induce a manifest ischaemic optic neuropathy. In atherosclerotic individuals, the susceptibility to this disorder becomes higher due to serotonin-enhancing platelet aggregation on the atheromata of ocular arteries.4, 5, 9

Recovery of vision is rare following nonvasculitic ischaemic optic neuropathy and therefore the question of a toxic aetiology remains open. These patients had been taking SSRIs for a mean of 7 years (range 1–14 years). These side effects may result from cumulative risk of prolonged treatment. In our series, we have identified smoking and diabetes as potentially synergistic risk factors in 4/5 cases.

Awareness of these potentially blinding vascular side effects is important. We advise caution when prescribing SSRIs in conjunction with known systemic vascular risk factors or pre-existing vascular eye disease until the origin of this neuropathy becomes clearer.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, Sandor P, Ruiz I, Roberts EA, et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1981;30 (2:239–245. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1981.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petty R, House A, Knapp P, Raynor T, Zermansky A. Prevalence, duration and indications for prescribing of antidepressants in primary care. Age Ageing. 2006;35 (5:523–526. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afl023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutcheon ML. An unexpected case of swollen optic nerves. Am J Ther. 2011;18 (4:e126–e129. doi: 10.1097/MJT.0b013e318207ec20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costagliola C, Parmeggiani F, Semeraro F, Sebastiani A. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: a review of its effects on intraocular pressure. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2008;6:293–310. doi: 10.2174/157015908787386104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayreh SS. Retinal and optic nerve head ischemic disorders and atherosclerosis: role of serotonin. Prog Retin Eye Res. 1999;18:191–221. doi: 10.1016/s1350-9462(98)00016-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardisty A, Hemmerdinger C, Say A. Citalopram-associated central retinal vein occlusion. Int Ophthalmol. 2009;29:303–304. doi: 10.1007/s10792-008-9231-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurn A, et al. Venous thromboembolism and escilatopram. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2004;26:481–483. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2004.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aggarwal A, Ramish K, Sharma R, Sharma D. Escitalopram and ischaemic stroke: causal or chance association. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2011;23:E38–E39. doi: 10.1176/jnp.23.2.jnpe38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayreh SS. Posterior ischaemic optic neuropathy:clinical features, pathogenesis, and management. Eye. 2004;18:1188–1206. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6701562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein R, Klein BE, Moss SE, Meuer SM. The epidemiology of retinal vein occlusion: the Beaver Dam Eye Study. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 2000;98:133–143. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preechawat P, Bruce BB, Newman NJ, Biousse V. Anterior ischemic optic neuropathy in patients younger than 50 years. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;144:953–960. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2007.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayreh SS. Management of ischemic optic neuropathies. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2011;59 (2:123–136. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.77024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]