Abstract

Conventional myosin II is an essential protein for cytokinesis, capping of cell surface receptors, and development of Dictyostelium cells. Myosin II also plays an important role in the polarization and movement of cells. All conventional myosins are double-headed molecules but the significance of this structure is not understood since single-headed myosin II can produce movement and force in vitro. We found that expression of the tail portion of myosin II in Dictyostelium led to the formation of single-headed myosin II in vivo. The resultant cells contain an approximately equal ratio of double- and single-headed myosin II molecules. Surprisingly, these cells were completely blocked in cytokinesis and capping of concanavalin A receptors although development into fruiting bodies was not impaired. We found that this phenotype is not due to defects in myosin light chain phosphorylation. These results show that single-headed myosin II cannot function properly in vivo and that it acts as a dominant negative mutation for myosin II function. These results suggest the possibility that cooperativity of myosin II heads is critical for force production in vivo.

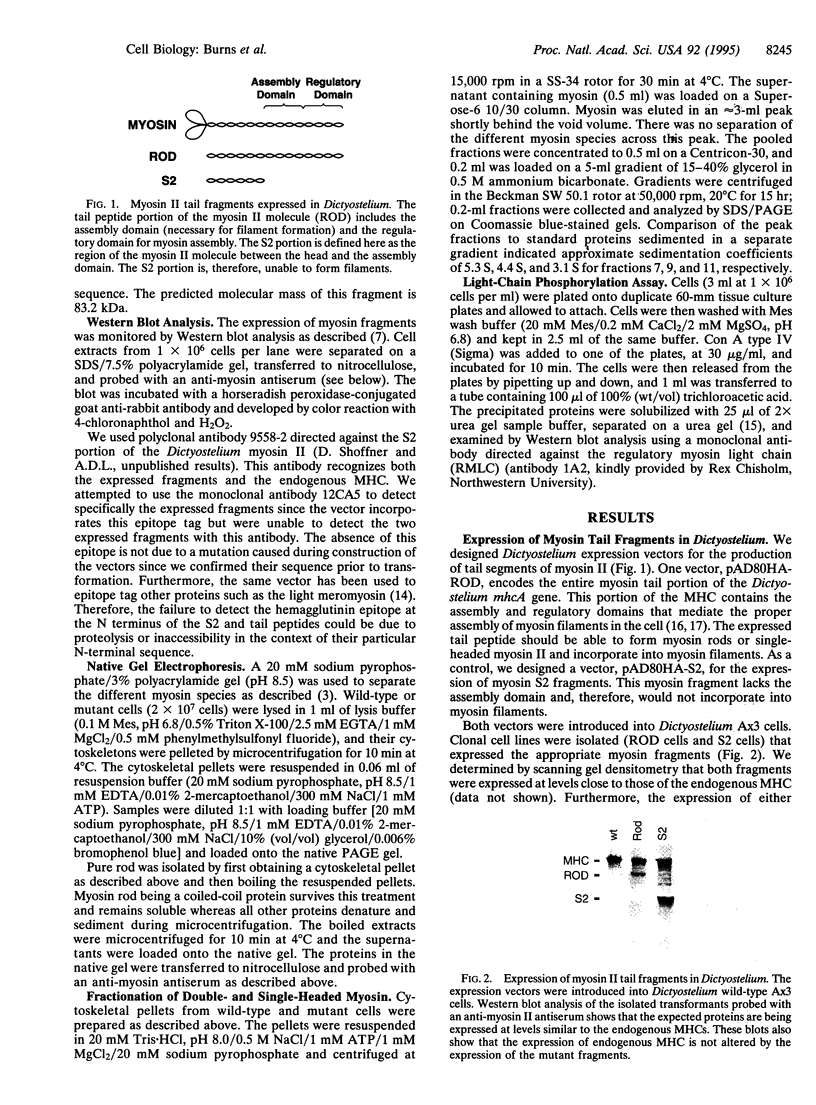

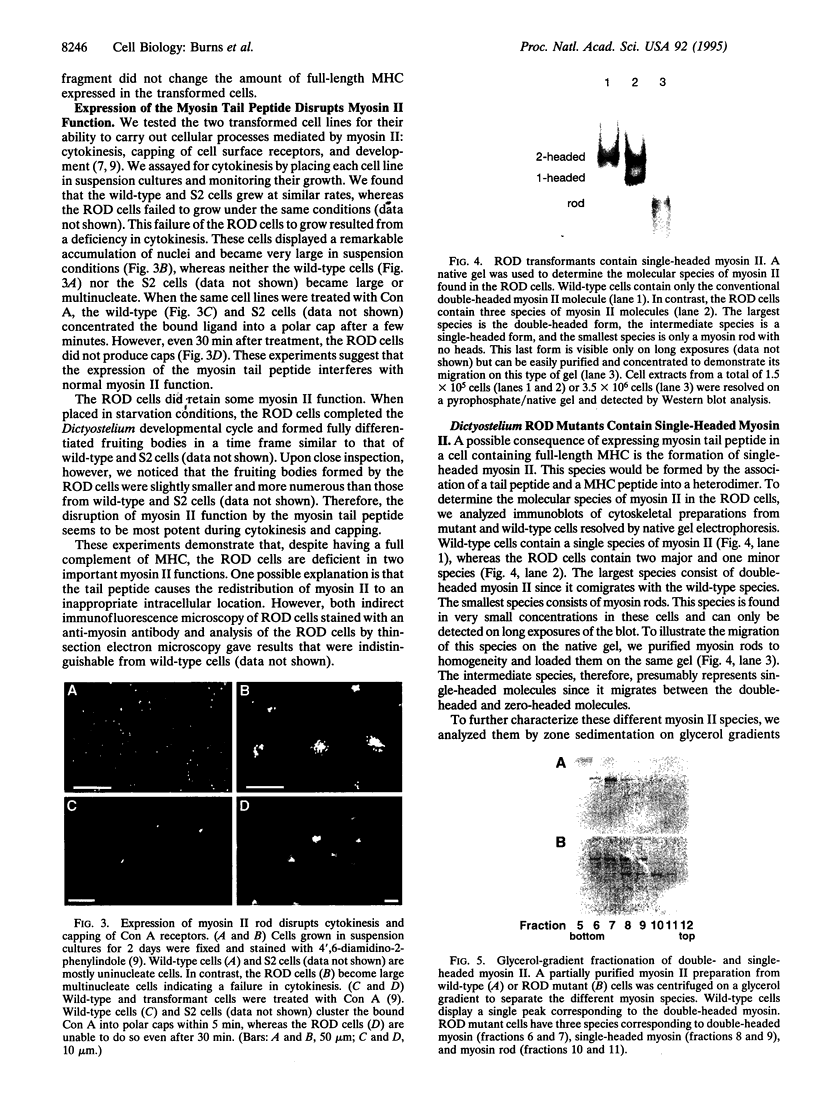

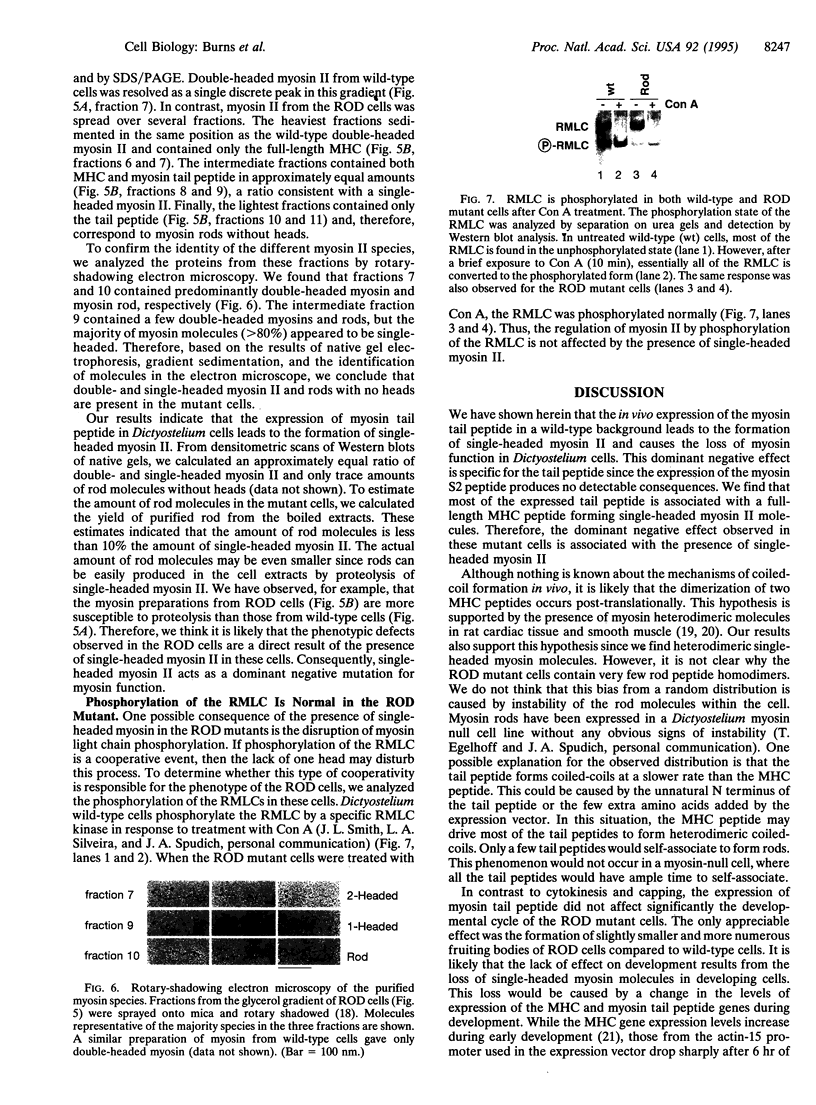

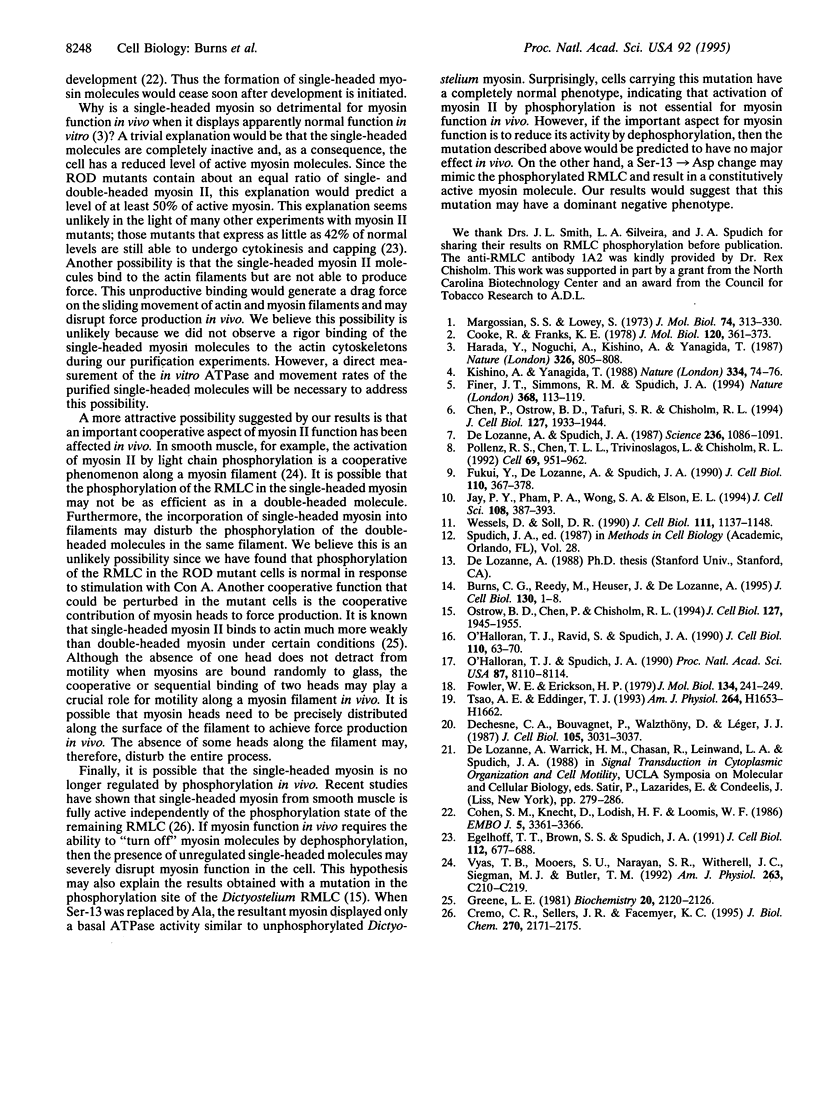

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Chen P., Ostrow B. D., Tafuri S. R., Chisholm R. L. Targeted disruption of the Dictyostelium RMLC gene produces cells defective in cytokinesis and development. J Cell Biol. 1994 Dec;127(6 Pt 2):1933–1944. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.6.1933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S. M., Knecht D., Lodish H. F., Loomis W. F. DNA sequences required for expression of a Dictyostelium actin gene. EMBO J. 1986 Dec 1;5(12):3361–3366. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04651.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke R., Franks K. E. Generation of force by single-headed myosin. J Mol Biol. 1978 Apr 15;120(3):361–373. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(78)90424-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cremo C. R., Sellers J. R., Facemyer K. C. Two heads are required for phosphorylation-dependent regulation of smooth muscle myosin. J Biol Chem. 1995 Feb 3;270(5):2171–2175. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.5.2171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Lozanne A., Spudich J. A. Disruption of the Dictyostelium myosin heavy chain gene by homologous recombination. Science. 1987 May 29;236(4805):1086–1091. doi: 10.1126/science.3576222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dechesne C. A., Bouvagnet P., Walzthöny D., Léger J. J. Visualization of cardiac ventricular myosin heavy chain homodimers and heterodimers by monoclonal antibody epitope mapping. J Cell Biol. 1987 Dec;105(6 Pt 2):3031–3037. doi: 10.1083/jcb.105.6.3031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egelhoff T. T., Brown S. S., Spudich J. A. Spatial and temporal control of nonmuscle myosin localization: identification of a domain that is necessary for myosin filament disassembly in vivo. J Cell Biol. 1991 Feb;112(4):677–688. doi: 10.1083/jcb.112.4.677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finer J. T., Simmons R. M., Spudich J. A. Single myosin molecule mechanics: piconewton forces and nanometre steps. Nature. 1994 Mar 10;368(6467):113–119. doi: 10.1038/368113a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler W. E., Erickson H. P. Trinodular structure of fibrinogen. Confirmation by both shadowing and negative stain electron microscopy. J Mol Biol. 1979 Oct 25;134(2):241–249. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(79)90034-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukui Y., De Lozanne A., Spudich J. A. Structure and function of the cytoskeleton of a Dictyostelium myosin-defective mutant. J Cell Biol. 1990 Feb;110(2):367–378. doi: 10.1083/jcb.110.2.367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene L. E. Comparison of the binding of heavy meromyosin and myosin subfragment 1 in F-actin. Biochemistry. 1981 Apr 14;20(8):2120–2126. doi: 10.1021/bi00511a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada Y., Noguchi A., Kishino A., Yanagida T. Sliding movement of single actin filaments on one-headed myosin filaments. Nature. 1987 Apr 23;326(6115):805–808. doi: 10.1038/326805a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jay P. Y., Pham P. A., Wong S. A., Elson E. L. A mechanical function of myosin II in cell motility. J Cell Sci. 1995 Jan;108(Pt 1):387–393. doi: 10.1242/jcs.108.1.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishino A., Yanagida T. Force measurements by micromanipulation of a single actin filament by glass needles. Nature. 1988 Jul 7;334(6177):74–76. doi: 10.1038/334074a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korioth F., Gieffers C., Maul G. G., Frey J. Molecular characterization of NDP52, a novel protein of the nuclear domain 10, which is redistributed upon virus infection and interferon treatment. J Cell Biol. 1995 Jul;130(1):1–13. doi: 10.1083/jcb.130.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margossian S. S., Lowey S. Substructure of the myosin molecule. IV. Interactions of myosin and its subfragments with adenosine triphosphate and F-actin. J Mol Biol. 1973 Mar 5;74(3):313–330. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(73)90376-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Halloran T. J., Ravid S., Spudich J. A. Expression of Dictyostelium myosin tail segments in Escherichia coli: domains required for assembly and phosphorylation. J Cell Biol. 1990 Jan;110(1):63–70. doi: 10.1083/jcb.110.1.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Halloran T. J., Spudich J. A. Genetically engineered truncated myosin in Dictyostelium: the carboxyl-terminal regulatory domain is not required for the developmental cycle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990 Oct;87(20):8110–8114. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.20.8110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostrow B. D., Chen P., Chisholm R. L. Expression of a myosin regulatory light chain phosphorylation site mutant complements the cytokinesis and developmental defects of Dictyostelium RMLC null cells. J Cell Biol. 1994 Dec;127(6 Pt 2):1945–1955. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.6.1945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollenz R. S., Chen T. L., Trivinos-Lagos L., Chisholm R. L. The Dictyostelium essential light chain is required for myosin function. Cell. 1992 Jun 12;69(6):951–962. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90614-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsao A. E., Eddinger T. J. Smooth muscle myosin heavy chains combine to form three native myosin isoforms. Am J Physiol. 1993 May;264(5 Pt 2):H1653–H1662. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1993.264.5.H1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vyas T. B., Mooers S. U., Narayan S. R., Witherell J. C., Siegman M. J., Butler T. M. Cooperative activation of myosin by light chain phosphorylation in permeabilized smooth muscle. Am J Physiol. 1992 Jul;263(1 Pt 1):C210–C219. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1992.263.1.C210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wessels D., Soll D. R. Myosin II heavy chain null mutant of Dictyostelium exhibits defective intracellular particle movement. J Cell Biol. 1990 Sep;111(3):1137–1148. doi: 10.1083/jcb.111.3.1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]