Abstract

The incidence and mortality of gastric cancer have fallen dramatically in US and elsewhere over the past several decades. Nonetheless, gastric cancer remains a major public health issue as the fourth most common cancer and the second leading cause of cancer death worldwide. Demographic trends differ by tumor location and histology. While there has been a marked decline in distal, intestinal type gastric cancers, the incidence of proximal, diffuse type adenocarcinomas of the gastric cardia has been increasing, particularly in the Western countries. Incidence by tumor sub-site also varies widely based on geographic location, race, and socio-economic status. Distal gastric cancer predominates in developing countries, among blacks, and in lower socio-economic groups, whereas proximal tumors are more common in developed countries, among whites, and in higher socio-economic classes. Diverging trends in the incidence of gastric cancer by tumor location suggest that they may represent two diseases with different etiologies. The main risk factors for distal gastric cancer include Helicobacter pylori (H pylori) infection and dietary factors, whereas gastroesophageal reflux disease and obesity play important roles in the development of proximal stomach cancer. The purpose of this review is to examine the epidemiology and risk factors of gastric cancer, and to discuss strategies for primary prevention.

Keywords: Epidemiology, Gastric cancer

INTRODUCTION

Overall, gastric cancer incidence and mortality have fallen dramatically over the past 70 years[1]. Despite its recent decline, gastric cancer is the fourth most common cancer and the second leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide[2,3]. In 2000, about 880 000 people were diagnosed with gastric cancer and approximately 650 000 died of the disease[4].

The two main tumor sites of gastric adenocarcinoma are proximal (cardia) and distal (noncardia). Despite a decline in distal gastric cancers, proximal tumors have been increasing in incidence since the 1970s, especially among males in the Western countries[5,6]. These gastric tumor types predominate in populations from different geographic locations, racial and socio-economic groups. They may also differ in genetic susceptibility, pathologic profile, clinical presentation, and prognosis. The observed differences between gastric cancers by anatomic site suggest that they are distinct diseases with different etiologies. Detailed epidemiological analyses of their demographic trends and risk factors will help guide future cancer control strategies.

PATHOLOGIC CONSIDERATIONS

About 90% of stomach tumors are adenocarcinomas, which are subdivided into two main histologic types: (1) well-differentiated or intestinal type, and (2) undifferentiated or diffuse type. The intestinal type is related to corpus-dominant gastritis with gastric atrophy and intestinal metaplasia, whereas the diffuse type usually originates in pangastritis without atrophy.

The intestinal type is more common in males, blacks, and older age groups, whereas the diffuse type has a more equal male-to-female ratio and is more frequent in younger individuals[7,8]. Intestinal type tumors predominate in high-risk geographic areas, such as East Asia, Eastern Europe, Central and South America, and account for much of the international variation of gastric cancer[9]. Diffuse type adenocarcinomas of the stomach have a more uniform geographic distribution[10]. A decline in the incidence of the intestinal type tumors in the corpus of the stomach accounts for most of the recent decrease in gastric cancer rates worldwide[11]. In contrast, the incidence of diffuse type gastric carcinoma, particularly the signet ring type, has been increasing[12].

DEMOGRAPHIC TRENDS

Time trends

In the 1930s, gastric cancer was the most common cause of cancer death in US and Europe. During the past 70 years, mortality rates have fallen dramatically in all developed countries largely due to unplanned prevention. However, in the past 30 years, the incidence of gastric cardia adenocarcinoma rose by five- to six-fold in developed countries[13-19]. Gastric cardia tumors now account for nearly half of all stomach cancers among men from US and UK[6,20]. There has also been a rising trend in esophageal adenocarcinoma, in which obesity, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), and Barrett’s esophagus are major etiologic factors. Gastric cardia cancers share certain epidemiologic features with adenocarcinomas of the distal esophagus and gastroesophageal (GE) junction, suggesting that they represent a similar disease entity.

Geographic variation

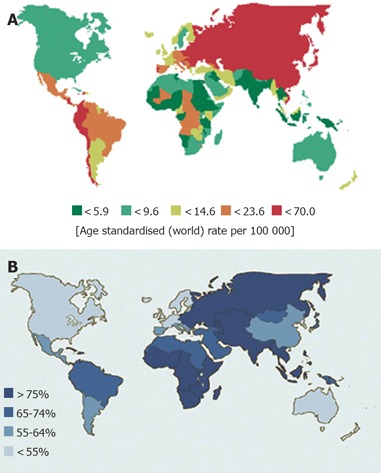

Gastric cancer incidence rates vary by up to ten-fold throughout the world. Nearly two-thirds of stomach cancers occur in developing countries[4]. Japan and Korea have the highest gastric cancer rates in the world[21,22]. High-incidence areas for noncardia gastric adenocarcinoma include East Asia, Eastern Europe, and Central and South America[20,23]. Low incidence rates are found in South Asia, North and East Africa, North America, Australia, and New Zealand (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

(A) Incidence of stomach cancer in males. (B) Prevalence of H pylori infection in asymptomatic adults. (Data adopted from Parkin et al[3].)

In Japan, gastric cancer remains the most common type of cancer among both men and women. Age-standardized incidence rates in Japan are 69.2 per 100 000 in men and 28.6 per 100 000 in women[3]. In contrast to the increasing incidence of proximal tumors in the West, distal tumors continue to predominate in Japan. However, even in Japan, the proportion of proximal stomach cancers has increased among men[24].

Migrant populations from high-risk areas such as Japan show a marked reduction in risk when they move to low-incidence regions such as the US[25]. Subsequent generations acquire risk levels approximating those of the host country[20,23].

Sex, race, and age distribution

Noncardia gastric cancer has a male-to-female ratio of approximately 2:1[20,23]. Incidence rates are significantly higher among blacks and lower socio-economic groups, and in developing countries[20]. Incidence rises progressively with age, with a peak incidence between 50 and 70 years.

In contrast, for gastric cardia carcinomas, men are affected five times more than women and whites twice as much as blacks[26]. In addition, the incidence rates of proximal gastric cancers are relatively higher in the professional classes[27]. Different rates of genetic polymorphisms according to tumor sub-site suggest variation in susceptibility to stomach cancer by tumor location[28]. These findings suggest that noncardia and cardia adenocarcinomas are distinct biological entities.

SURVIVAL

For the past few decades, gastric cancer mortality has decreased markedly in most areas of the world[29,30]. However, gastric cancer remains a disease of poor prognosis and high mortality, second only to lung cancer as the leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide. In general, countries with higher incidence rates of gastric cancer show better survival rates than countries with lower incidence[31]. This association is largely due to a difference in survival rates based on tumor location within the stomach. Tumors located in the gastric cardia have a much poorer prognosis compared to those in the pyloric antrum, with lower 5-year survival and higher operative mortality[32].

In addition, the availability of screening for early detection in high-risk areas has led to a decrease in mortality. In Japan where mass screening programs are in place, mortality rates for gastric cancer in men have more than halved since the early 1970s[33]. When disease is confined to the inner lining of the stomach wall, 5-year survival is on the order of 95%. In contrast, few gastric cancers are discovered at an early stage in US, leading to 5-year relative survival rates of less than 20%[34]. Similarly in European countries, the 5-year relative survival rates for gastric cancer vary from 10% to 20%[35,36]. Host-related factors may also affect prognosis, as a US study demonstrated that gastric cancers in persons of Asian descent had a better prognosis compared to non-Asians[37].

RISK FACTORS

Gastric cancer is a multifactorial disease. The marked geographic variation, time trends, and the migratory effect on gastric cancer incidence suggest that environmental or lifestyle factors are major contributors to the etiology of this disease.

Helicobacter pylori infection

H pylori is a gram-negative bacillus that colonizes the stomach and may be the most common chronic bacterial infection worldwide[38]. Countries with high gastric cancer rates typically have a high prevalence of H pylori infection, and the decline in H pylori prevalence in developed countries parallels the decreasing incidence of gastric cancer[39,40] (Figure 1B). In US, the prevalence of H pylori infection is <20% at the age 20 years and 50% at 50 years[41]. In Japan, it is also <20% at 20 years, but increases to 80% over the age of 40 years[42] and in Korea, 90% of asymptomatic adults over the age of 20 years are infected by H pylori[43]. The increase in prevalence with age is largely due to a birth cohort effect rather than late acquisition of infection. H pylori infection is mainly acquired during early childhood, likely through oral ingestion, and infection persists throughout life[44]. Prevalence is closely linked to socio-economic factors, such as low income and poor education, and living conditions during childhood, such as poor sanitation and overcrowding[45-49].

The association between chronic H pylori infection and the development of gastric cancer is well established[50-53]. In 1994, the International Agency for Research on Cancer classified H pylori as a type I (definite) carcinogen in human beings[54]. In Correa’s model of gastric carcinogenesis, H pylori infection triggers the progressive sequence of gastric lesions from chronic gastritis, gastric atrophy, intestinal metaplasia, dysplasia, and finally, gastric adenocarcinoma[55]. Several case-control studies have shown significant associations between H pylori seropositivity and gastric cancer risk, with about a 2.1- to 16.7-fold greater risk compared to seronegative individuals[56-62]. Prospective studies have also supported the association between H pylori infection and gastric cancer risk[50-52,63]. Perhaps the most compelling evidence for the link between H pylori and gastric cancer comes from a prospective study of 1 526 Japanese participants in which gastric cancers developed in 2.9% of infected people and in none of the uninfected individuals[64]. Interestingly, gastric carcinomas were detected in 4.7% of H pylori-infected individuals with non-ulcer dyspepsia.

The vast majority of H pylori-infected individuals remain asymptomatic without any clinical sequelae. Cofactors, which determine that H pylori-infected people are at particular risk for gastric cancer, include bacterial virulence factors and proinflammatory host factors. Gastric cancer risk is enhanced by infection with a more virulent strain of H pylori carrying the cytotoxin-associated gene A (cagA)[65,66]. Compared to cagA- strains, infection by H pylori cagA+ strains was associated with an increased risk of severe atrophic gastritis and distal gastric cancer[67-70]. In the Western countries, about 60% of H pylori isolates are cagA+[71], whereas in Japan, nearly 100% of the strains possess functional cagA[72,73]. Host factors associated with an increased risk of gastric cancer include genetic polymorphisms which lead to high-level of expression of the proinflammatory cytokine, interleukin-1β[74,75].

The effects of H pylori on gastric tumor development may vary by anatomical site. The falling incidence of H pylori infection and noncardia gastric cancer in developed countries has been diametrically opposed to the rapid increase in the incidence of gastric cardia adenocarcinoma[76]. Based on a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies, H pylori infection was associated with the risk of noncardia gastric cancer, but not cardia cancer[77]. Other studies demonstrated a significant inverse association between H pylori infection, particularly cagA+ strains, and the development of gastric cardia and esophageal adenocarcinomas[78,79]. In the Western countries, where the prevalence of H pylori infection is falling, GERD and its sequelae are increasing. Studies have shown that severe atrophic gastritis and reduced acid production associated with H pylori infection significantly reduced the risk of GERD[80-83]. However, recent studies have found conflicting results on whether H pylori eradication therapy increases the risk of esophagitis and gastric cardia adenocarcinoma[84-91]. Thus, the protective effect of H pylori against cardia tumors remains controversial.

Dietary factors

It is unlikely that H pylori infection alone is responsible for the development of gastric cancer. Rather, H pylori may produce an environment conducive to carcinogenesis and interact with other lifestyle and environmental exposures. There is evidence that consumption of salty foods and N-nitroso compounds and low intake of fresh fruits and vegetables increases the risk of gastric cancer. H pylori gastritis facilitates the growth of nitrosating bacteria, which catalyze the production of carcinogenic N-nitroso compounds[92]. In addition, H pylori infection is known to inhibit gastric secretion of ascorbic acid, which is an important scavenger of N-nitroso compounds and oxygen free radicals[93].

Salt-preserved foods and dietary nitrite found in preserved meats are potentially carcinogenic. Intake of salted food may increase the risk of H pylori infection and act synergistically to promote the development of gastric cancer. In animal models, ingestion of salt is known to cause gastritis and enhance the effects of gastric carcinogens[94,95]. Mucosal damage induced by salt may increase the possibility of persistent infection with H pylori[96]. Several case-control studies have shown that a high intake of salt and salt-preserved food was associated with gastric cancer risk[97-103], but evidence from prospective studies is inconsistent[104-107]. N-nitroso compounds are carcinogenic in animal models and are formed in the human stomach from dietary nitrite. However, case-control studies have shown a weak, nonsignificant increased risk of gastric cancer for high vs low nitrite intake[97,108-110]. Prospective studies have reported significant reductions in gastric cancer risk arising from fruit and vegetable consumption[111-114]. The worldwide decline in gastric cancer incidence may be attributable to the advent of refrigeration, which led to decreased consumption of preserved foods and increased intake of fresh fruits and vegetables.

Animal studies have shown that polyphenols in green tea have antitumor and anti-inflammatory effects. In preclinical studies, polyphenols have antioxidant activities and the ability to inhibit nitrosation, which have been implicated as etiologic factors of gastric cancer[115-117]. Although various case-control studies have shown a reduced risk of gastric cancer in relation to green tea consumption[118-121], recent prospective cohort studies found no protective effect of green tea on gastric cancer risk[122-125].

Tobacco

Prospective studies have demonstrated a significant dose-dependent relationship between smoking and gastric cancer risk[126,127]. The effect of smoking was more pronounced for distal gastric cancer, with adjusted rate ratios of 2.0 (95% CI, 1.1-3.7) and 2.1 (95% CI, 1.2-3.6) for past and current smokers, respectively[128]. There is little support for an association between alcohol and gastric cancer[129].

Obesity

Obesity is one of the main risk factors for gastric cardia adenocarcinoma[130,131]. Obesity can promote GE reflux disease which predisposes to Barrett’s esophagus, a metaplastic precursor state for adenocarcinoma of the esophagus and GE junction[132,133]. A Swedish study found that the heaviest quarter of the population had a 2.3-fold increased risk for gastric cardia adenocarcinoma compared to the lightest quartile of the population[134]. A recent prospective study from US found that body mass index was significantly associated with higher rates of stomach cancer mortality among men[135]. Thus, risk factors positively associated with adenocarcinoma of the esophagus and gastric cardia include obesity, GE reflux, and the presence of Barrett’s esophagus. A summary of the main differences between cardia and noncardia gastric cancer can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Epidemiologic differences between cardia and noncardia gastric cancer

| Cardia | Noncardia | |

| Incidence | Increasing | Decreasing |

| Geographic location | ||

| Western countries | + | - |

| East Asia | - | + |

| Developing countries | - | + |

| Age | ++ | ++ |

| Male gender | ++ | + |

| Caucasian race | + | - |

| Low socio-economic status | - | + |

| H pylori infection | ? | + |

| Diet | ||

| Preserved foods | + | + |

| Fruits/vegetables | - | - |

| Obesity | + | ? |

| Tobacco | + | + |

NOTE: ++, strong positive association; +, positive association; -, negative association; ?, ambiguous studies.

Other

Less common risk factors for gastric cancer include radiation[136], pernicious anemia[137], blood type A[138], prior gastric surgery for benign conditions[139], and Epstein-Barr virus[140-142]. In addition, a positive family history is a significant risk factor, particularly with genetic syndromes such as hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer and Li-Fraumeni syndrome[143-145].

PREVENTION OF GASTRIC CANCER

Lifestyle modifications

Because gastric cancer is often associated with a poor prognosis, the main strategy for improving clinical outcomes is through primary prevention. Reduction in gastric cancer mortality is largely due to unplanned prevention. The widespread introduction of refrigeration has led to a decrease in the intake of chemically preserved foods and increased consumption of fresh fruits and vegetables[98,146]. A decline in the prevalence of H pylori infection may be due to improvements in sanitary and housing conditions, as well as the use of eradication therapy[54]. In addition, reduced tobacco smoking at least in males may have contributed to the decline in gastric cancer incidence[147]. Therefore, modifiable risk factors, such as high salt and nitrite consumption, low fruit and vegetable intake, cigarette smoking, and H pylori infection, may be targeted for prevention.

Helicobacter pylori eradication

Public health measures to improve sanitation and housing conditions are the key factors in reducing the worldwide prevalence of H pylori infection. H pylori eradication therapy is another potential strategy for gastric cancer chemoprevention. A 7 to 14 d course of two antibiotics and an antisecretory agent has a cure rate of about 80% with durable responses[148]. However, higher reinfection rates are seen in developing countries after people have had effective eradication therapy[149]. In Japanese patients treated for early gastric cancer, H pylori eradication therapy resulted in a significantly lower rate of gastric cancer recurrence[150]. A randomized controlled chemoprevention trial showed that antimicrobial therapy directed against H pylori or dietary supplementation with antioxidants increased the regression rate of gastric atrophy and intestinal metaplasia compared to placebo[151]. In a randomized, placebo-controlled primary prevention trial conducted in a high-risk region of China, 1 630 healthy carriers of H pylori infection were randomized to a 2-wk course of eradication treatment or placebo[152]. Although the incidence of gastric cancer was similar in both groups after 7.5 years of follow-up, post hoc analysis of a subgroup of H pylori carriers without precancerous lesions at baseline showed a significant decrease in the development of gastric cancer with eradication therapy.

Several large-scale chemoprevention trials of H pylori eradication therapy with gastric cancer endpoints are ongoing. Potential downsides of widespread eradication therapy in asymptomatic carriers include developing antibiotic-resistant strains of H pylori and perhaps increasing the risk of GERD and adenocarcinoma of the esophagus and gastric cardia.

Antioxidants

High intake of antioxidants, such as vitamins C and E and β-carotene, may have a protective effect on the risk of gastric cancer. High serum levels of α-carotene, β-carotene, lycopene, and vitamin C were significantly associated with reduced risk of gastric cancer in a cohort from Shanghai, China[153]. A randomized trial in Linxian, China showed a reduced risk of both cardia and noncardia gastric cancers in individuals supplemented with a combination of selenium, β-carotene, and α-tocopherol[154]. However, a randomized trial from Finland showed no association between α-tocopherol or β-carotene supplementation and the prevalence of gastric cancer in elderly men with atrophic gastritis[155]. Another prospective study from the US Cancer Prevention Study II cohort found that vitamin supplementation did not significantly reduce the risk of stomach cancer mortality[156]. Therefore, dietary supplementation may only play a preventive role in populations with high rates of gastric cancer and low intake of micronutrients.

COX-2 inhibitors

Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) plays a role in cell proliferation, apoptosis, and angiogenesis, and may be involved in gastric carcinogenesis[157,158]. Increasing levels of COX-2 are present in the progression from atrophic gastritis to intestinal metaplasia and adenocarcinoma of the stomach[159]. Exposure to cigarette smoke, acidic conditions, and H pylori infection all induce COX-2 expression[160-162]. Furthermore, McCarthy et al. showed that COX-2 expression in the antral mucosa was reduced in the epithelium after successful eradication of H pylori[163].

Aspirin and other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are thought to inhibit cancer cell growth primarily through the inhibition of COX-2, and evidence is mounting that COX-2 inhibitors may be beneficial in preventing upper gastrointestinal malignancies. Compared to colorectal cancer, the association between NSAID use and the development of gastric cancer has been studied less extensively[164-166]. A recent meta-analysis showed that NSAID use was associated with a reduced risk of noncardia gastric adenocarcinoma[167]. Thus, COX-2 inhibitors may provide a chemopreventive strategy against gastric carcinogenesis.

Endoscopic screening and surveillance

Because of the high risk of gastric cancer in Japan, there has been a national endoscopic surveillance program within the commercial workforce. Annual screening with a double-contrast barium technique and endoscopy is recommended for persons over the age of 40 years[168]. With mass screening, about half of gastric tumors are being detected at an early stage in asymptomatic individuals and the mortality rate from gastric cancer has more than halved since the early 1970s[33]. An intervention study in China is underway which involves a comprehensive approach to gastric cancer prevention, including H pylori eradication, nutritional supplements, and aggressive screening with double contrast X-ray and endoscopic examination. In the first four years after intervention, the relative risk of overall mortality with this intervention for a high-risk group was 0.51 (95% CI, 0.35-0.74)[169]. This study suggests that targeting high-risk populations for aggressive screening and prevention may decrease gastric cancer mortality.

CONCLUSION

In summary, cardia and noncardia gastric cancers exhibit unique epidemiologic features characterized by marked geographic variation, diverging time trends, and differences based on race, sex, and socio-economic status. H pylori infection and dietary factors appear to be the main causative agents for distal gastric cancer, whereas GERD and obesity play a primary role in proximal gastric cancer. Future directions in primary prevention should target modifiable risk factors in high-risk populations. In the planning and evaluation of gastric cancer control activities, detailed demographic analyses will inform future screening and intervention studies.

Footnotes

S- Editor Xia HHX and Guo SY L- Editor Elsevier HK E- Editor Liu WF

References

- 1.Parkin DM, Pisani P, Ferlay J. Estimates of the worldwide incidence of eighteen major cancers in 1985. Int J Cancer. 1993;54:594–606. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910540413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parkin DM, Bray FI, Devesa SS. Cancer burden in the year 2000. The global picture. Eur J Cancer. 2001;37 Suppl 8:S4–66. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(01)00267-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parkin DM. International variation. Oncogene. 2004;23:6329–6340. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stewart BW, Kleihues P. World Cancer Report. Lyon: IARC Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blot WJ, Devesa SS, Kneller RW, Fraumeni JF. Rising incidence of adenocarcinoma of the esophagus and gastric cardia. JAMA. 1991;265:1287–1289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown LM, Devesa SS. Epidemiologic trends in esophageal and gastric cancer in the United States. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2002;11:235–256. doi: 10.1016/s1055-3207(02)00002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lauren P. The two histological main types of gastric carcinoma: diffuse and so-called intestinal-type carcinoma. An attempt at a histo-clinical classification. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand. 1965;64:31–49. doi: 10.1111/apm.1965.64.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Correa P, Sasano N, Stemmermann GN, Haenszel W. Pathology of gastric carcinoma in Japanese populations: comparisons between Miyagi prefecture, Japan, and Hawaii. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1973;51:1449–1459. doi: 10.1093/jnci/51.5.1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Munoz N. Gastric Carcinogenesis. In: Reed PI, Hill MJ, eds , editors. Gastric carcinogenesis: proceedings of the 6th Annual Symposium of the European Organization for Cooperation in Cancer Prevention Studies (ECP) Amsterdam: Elsevier Science; 1988. pp. 51–69. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muñoz N, Correa P, Cuello C, Duque E. Histologic types of gastric carcinoma in high- and low-risk areas. Int J Cancer. 1968;3:809–818. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910030614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaneko S, Yoshimura T. Time trend analysis of gastric cancer incidence in Japan by histological types, 1975-1989. Br J Cancer. 2001;84:400–405. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Henson DE, Dittus C, Younes M, Nguyen H, Albores-Saavedra J. Differential trends in the intestinal and diffuse types of gastric carcinoma in the United States, 1973-2000: increase in the signet ring cell type. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2004;128:765–770. doi: 10.5858/2004-128-765-DTITIA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pera M, Cameron AJ, Trastek VF, Carpenter HA, Zinsmeister AR. Increasing incidence of adenocarcinoma of the esophagus and esophagogastric junction. Gastroenterology. 1993;104:510–513. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(93)90420-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hansen S, Wiig JN, Giercksky KE, Tretli S. Esophageal and gastric carcinoma in Norway 1958-1992: incidence time trend variability according to morphological subtypes and organ subsites. Int J Cancer. 1997;71:340–344. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19970502)71:3<340::aid-ijc5>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Møller H. Incidence of cancer of oesophagus, cardia and stomach in Denmark. Eur J Cancer Prev. 1992;1:159–164. doi: 10.1097/00008469-199202000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harrison SL, Goldacre MJ, Seagroatt V. Trends in registered incidence of oesophageal and stomach cancer in the Oxford region, 1974-88. Eur J Cancer Prev. 1992;1:271–274. doi: 10.1097/00008469-199204000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levi F, La Vecchia C, Te VC. Descriptive epidemiology of adenocarcinomas of the cardia and distal stomach in the Swiss Canton of Vaud. Tumori. 1990;76:167–171. doi: 10.1177/030089169007600203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Armstrong RW, Borman B. Trends in incidence rates of adenocarcinoma of the oesophagus and gastric cardia in New Zealand, 1978-1992. Int J Epidemiol. 1996;25:941–947. doi: 10.1093/ije/25.5.941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thomas RJ, Lade S, Giles GG, Thursfield V. Incidence trends in oesophageal and proximal gastric carcinoma in Victoria. Aust N Z J Surg. 1996;66:271–275. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1996.tb01183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parkin DM, Whelan SL, Ferlay J. Cancer Incidence in Five Continents. Vol VII. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 1997. pp. 822–823. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yamamoto S. Stomach cancer incidence in the world. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2001;31:471. doi: 10.1093/jjco/31.9.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ahn YO, Park BJ, Yoo KY, Kim NK, Heo DS, Lee JK, Ahn HS, Kang DH, Kim H, Lee MS. Incidence estimation of stomach cancer among Koreans. J Korean Med Sci. 1991;6:7–14. doi: 10.3346/jkms.1991.6.1.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nomura A. Stomach Cancer. In: Schottenfeld D, Fraumeni JF, eds , editors. Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 1996. pp. 707–724. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu Y, Kaneko S, Sobue T. Trends in reported incidences of gastric cancer by tumour location, from 1975 to 1989 in Japan. Int J Epidemiol. 2004;33:808–815. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyh053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McMichael AJ, McCall MG, Hartshorne JM, Woodings TL. Patterns of gastro-intestinal cancer in European migrants to Australia: the role of dietary change. Int J Cancer. 1980;25:431–437. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910250402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.El-Serag HB, Mason AC, Petersen N, Key CR. Epidemiological differences between adenocarcinoma of the oesophagus and adenocarcinoma of the gastric cardia in the USA. Gut. 2002;50:368–372. doi: 10.1136/gut.50.3.368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Powell J, McConkey CC. The rising trend in oesophageal adenocarcinoma and gastric cardia. Eur J Cancer Prev. 1992;1:265–269. doi: 10.1097/00008469-199204000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shen H, Xu Y, Qian Y, Yu R, Qin Y, Zhou L, Wang X, Spitz MR, Wei Q. Polymorphisms of the DNA repair gene XRCC1 and risk of gastric cancer in a Chinese population. Int J Cancer. 2000;88:601–606. doi: 10.1002/1097-0215(20001115)88:4<601::aid-ijc13>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jemal A, Thomas A, Murray T, Thun M. Cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin. 2002;52:23–47. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.52.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ries LA, Kosary CL, Hankey BF. SEER Cancer Statistics Review 1973-1995. Bethesda: U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Verdecchia A, Corazziari I, Gatta G, Lisi D, Faivre J, Forman D. Explaining gastric cancer survival differences among European countries. Int J Cancer. 2004;109:737–741. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fielding JWL, Powell J, Allum WH. Cancer of the Stomach. London: The Macmillan Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 33.IARC Unit of Descriptive Epidemiology: WHO cancer mortality databank. Cancer Mondial, 2001. Available from: http://www-dep.iarc.fr/ataava/globocan/who.htm.

- 34.Ries LAG, Kosary CL, Hankey BF, Miller BA, Harras A, Edwards BK. SEER Cancer Statistics Review 1973-1994, National Cancer Institute, NIH Publication No. 97-2789. Bethesda: Department of Health and Human Services; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Faivre J, Forman D, Estève J, Gatta G. Survival of patients with oesophageal and gastric cancers in Europe. EUROCARE Working Group. Eur J Cancer. 1998;34:2167–2175. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(98)00329-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Berrino F, Capocaccia R, Esteve J. Survival of Cancer Patients in Europe: The EUROCARE-2 Study. IARC Scientific Publications No. 151. Lyon: IARC; 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Theuer CP, Kurosaki T, Ziogas A, Butler J, Anton-Culver H. Asian patients with gastric carcinoma in the United States exhibit unique clinical features and superior overall and cancer specific survival rates. Cancer. 2000;89:1883–1892. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20001101)89:9<1883::aid-cncr3>3.3.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marshall BJ, Warren JR. Unidentified curved bacilli in the stomach of patients with gastritis and peptic ulceration. Lancet. 1984;1:1311–1315. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)91816-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Parsonnet J. The incidence of Helicobacter pylori infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1995;9 Suppl 2:45–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Howson CP, Hiyama T, Wynder EL. The decline in gastric cancer: epidemiology of an unplanned triumph. Epidemiol Rev. 1986;8:1–27. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dooley CP, Cohen H, Fitzgibbons PL, Bauer M, Appleman MD, Perez-Perez GI, Blaser MJ. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection and histologic gastritis in asymptomatic persons. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:1562–1566. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198912073212302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Asaka M, Kimura T, Kudo M, Takeda H, Mitani S, Miyazaki T, Miki K, Graham DY. Relationship of Helicobacter pylori to serum pepsinogens in an asymptomatic Japanese population. Gastroenterology. 1992;102:760. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)90156-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Youn HS, Ko GH, Chung MH, Lee WK, Cho MJ, Rhee KH. Pathogenesis and prevention of stomach cancer. J Korean Med Sci. 1996;11:373–385. doi: 10.3346/jkms.1996.11.5.373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Feldman RA. Epidemiologic observations and open questions about disease and infection caused by Helicobacter pylori. In: Achtman M, Serbaum S, editors. Helicobacter pylori: Molecular and Cellular Biology. Wymondham: Horizon Scientific; 2001. pp. 29–51. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Buckley MJ, O'Shea J, Grace A, English L, Keane C, Hourihan D, O'Morain CA. A community-based study of the epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection and associated asymptomatic gastroduodenal pathology. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998;10:375–379. doi: 10.1097/00042737-199805000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Webb PM, Knight T, Greaves S, Wilson A, Newell DG, Elder J, Forman D. Relation between infection with Helicobacter pylori and living conditions in childhood: evidence for person to person transmission in early life. BMJ. 1994;308:750–753. doi: 10.1136/bmj.308.6931.750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kurosawa M, Kikuchi S, Inaba Y, Ishibashi T, Kobayashi F. Helicobacter pylori infection among Japanese children. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;15:1382–1385. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2000.02360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Olmos JA, Ríos H, Higa R. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in Argentina: results of a nationwide epidemiologic study. Argentinean Hp Epidemiologic Study Group. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2000;31:33–37. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200007000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Goodman KJ, Correa P. Transmission of Helicobacter pylori among siblings. Lancet. 2000;355:358–362. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)05273-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Parsonnet J, Friedman GD, Vandersteen DP, Chang Y, Vogelman JH, Orentreich N, Sibley RK. Helicobacter pylori infection and the risk of gastric carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:1127–1131. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199110173251603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Forman D, Newell DG, Fullerton F, Yarnell JW, Stacey AR, Wald N, Sitas F. Association between infection with Helicobacter pylori and risk of gastric cancer: evidence from a prospective investigation. BMJ. 1991;302:1302–1305. doi: 10.1136/bmj.302.6788.1302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nomura A, Stemmermann GN, Chyou PH, Kato I, Perez-Perez GI, Blaser MJ. Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric carcinoma among Japanese Americans in Hawaii. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:1132–1136. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199110173251604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.An international association between Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric cancer. The EUROGAST Study Group. Lancet. 1993;341:1359–1362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.International Agency for Research on Cancer Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Schistosomes, Liver Flukes, and Helicobacter pylori. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 1994. pp. 177–240. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Correa P. Helicobacter pylori and gastric cancer: state of the art. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1996;5:477–481. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sipponen P, Kosunen TU, Valle J, Riihelä M, Seppälä K. Helicobacter pylori infection and chronic gastritis in gastric cancer. J Clin Pathol. 1992;45:319–323. doi: 10.1136/jcp.45.4.319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hansson LE, Engstrand L, Nyrén O, Evans DJ, Lindgren A, Bergström R, Andersson B, Athlin L, Bendtsen O, Tracz P. Helicobacter pylori infection: independent risk indicator of gastric adenocarcinoma. Gastroenterology. 1993;105:1098–1103. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(93)90954-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hu PJ, Mitchell HM, Li YY, Zhou MH, Hazell SL. Association of Helicobacter pylori with gastric cancer and observations on the detection of this bacterium in gastric cancer cases. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994;89:1806–1810. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kikuchi S, Wada O, Nakajima T, Nishi T, Kobayashi O, Konishi T, Inaba Y. Serum anti-Helicobacter pylori antibody and gastric carcinoma among young adults. Research Group on Prevention of Gastric Carcinoma among Young Adults. Cancer. 1995;75:2789–2793. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19950615)75:12<2789::aid-cncr2820751202>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kokkola A, Valle J, Haapiainen R, Sipponen P, Kivilaakso E, Puolakkainen P. Helicobacter pylori infection in young patients with gastric carcinoma. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1996;31:643–647. doi: 10.3109/00365529609009143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Barreto-Zuñiga R, Maruyama M, Kato Y, Aizu K, Ohta H, Takekoshi T, Bernal SF. Significance of Helicobacter pylori infection as a risk factor in gastric cancer: serological and histological studies. J Gastroenterol. 1997;32:289–294. doi: 10.1007/BF02934482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Miehlke S, Hackelsberger A, Meining A, von Arnim U, Müller P, Ochsenkühn T, Lehn N, Malfertheiner P, Stolte M, Bayerdörffer E. Histological diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori gastritis is predictive of a high risk of gastric carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 1997;73:837–839. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19971210)73:6<837::aid-ijc12>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nomura AM, Stemmermann GN, Chyou PH. Gastric cancer among the Japanese in Hawaii. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1995;86:916–923. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1995.tb03001.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Uemura N, Okamoto S, Yamamoto S, Matsumura N, Yamaguchi S, Yamakido M, Taniyama K, Sasaki N, Schlemper RJ. Helicobacter pylori infection and the development of gastric cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:784–789. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa001999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tomb JF, White O, Kerlavage AR, Clayton RA, Sutton GG, Fleischmann RD, Ketchum KA, Klenk HP, Gill S, Dougherty BA, et al. The complete genome sequence of the gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nature. 1997;388:539–547. doi: 10.1038/41483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Alm RA, Ling LS, Moir DT, King BL, Brown ED, Doig PC, Smith DR, Noonan B, Guild BC, deJonge BL, et al. Genomic-sequence comparison of two unrelated isolates of the human gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nature. 1999;397:176–180. doi: 10.1038/16495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kuipers EJ, Pérez-Pérez GI, Meuwissen SG, Blaser MJ. Helicobacter pylori and atrophic gastritis: importance of the cagA status. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995;87:1777–1780. doi: 10.1093/jnci/87.23.1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Blaser MJ, Perez-Perez GI, Kleanthous H, Cover TL, Peek RM, Chyou PH, Stemmermann GN, Nomura A. Infection with Helicobacter pylori strains possessing cagA is associated with an increased risk of developing adenocarcinoma of the stomach. Cancer Res. 1995;55:2111–2115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Parsonnet J, Friedman GD, Orentreich N, Vogelman H. Risk for gastric cancer in people with CagA positive or CagA negative Helicobacter pylori infection. Gut. 1997;40:297–301. doi: 10.1136/gut.40.3.297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Huang JQ, Zheng GF, Sumanac K, Irvine EJ, Hunt RH. Meta-analysis of the relationship between cagA seropositivity and gastric cancer. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1636–1644. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Vicari JJ, Peek RM, Falk GW, Goldblum JR, Easley KA, Schnell J, Perez-Perez GI, Halter SA, Rice TW, Blaser MJ, et al. The seroprevalence of cagA-positive Helicobacter pylori strains in the spectrum of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:50–57. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70364-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ito Y, Azuma T, Ito S, Miyaji H, Hirai M, Yamazaki Y, Sato F, Kato T, Kohli Y, Kuriyama M. Analysis and typing of the vacA gene from cagA-positive strains of Helicobacter pylori isolated in Japan. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1710–1714. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.7.1710-1714.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Azuma T, Yamakawa A, Yamazaki S, Fukuta K, Ohtani M, Ito Y, Dojo M, Yamazaki Y, Kuriyama M. Correlation between variation of the 3' region of the cagA gene in Helicobacter pylori and disease outcome in Japan. J Infect Dis. 2002;186:1621–1630. doi: 10.1086/345374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.El-Omar EM, Carrington M, Chow WH, McColl KE, Bream JH, Young HA, Herrera J, Lissowska J, Yuan CC, Rothman N, et al. Interleukin-1 polymorphisms associated with increased risk of gastric cancer. Nature. 2000;404:398–402. doi: 10.1038/35006081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.El-Omar EM, Rabkin CS, Gammon MD, Vaughan TL, Risch HA, Schoenberg JB, Stanford JL, Mayne ST, Goedert J, Blot WJ, et al. Increased risk of noncardia gastric cancer associated with proinflammatory cytokine gene polymorphisms. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:1193–1201. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00157-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Blaser MJ. Hypothesis: the changing relationships of Helicobacter pylori and humans: implications for health and disease. J Infect Dis. 1999;179:1523–1530. doi: 10.1086/314785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Helicobacter and Cancer Collaborative Group. Gastric cancer and Helicobacter pylori: a combined analysis of 12 case control studies nested within prospective cohorts. Gut. 2001;49:347–353. doi: 10.1136/gut.49.3.347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hansen S, Melby KK, Aase S, Jellum E, Vollset SE. Helicobacter pylori infection and risk of cardia cancer and non-cardia gastric cancer. A nested case-control study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1999;34:353–360. doi: 10.1080/003655299750026353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chow WH, Blaser MJ, Blot WJ, Gammon MD, Vaughan TL, Risch HA, Perez-Perez GI, Schoenberg JB, Stanford JL, Rotterdam H, et al. An inverse relation between cagA+ strains of Helicobacter pylori infection and risk of esophageal and gastric cardia adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res. 1998;58:588–590. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Warburton-Timms VJ, Charlett A, Valori RM, Uff JS, Shepherd NA, Barr H, McNulty CA. The significance of cagA(+) Helicobacter pylori in reflux oesophagitis. Gut. 2001;49:341–346. doi: 10.1136/gut.49.3.341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.El-Serag HB, Sonnenberg A, Jamal MM, Inadomi JM, Crooks LA, Feddersen RM. Corpus gastritis is protective against reflux oesophagitis. Gut. 1999;45:181–185. doi: 10.1136/gut.45.2.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Koike T, Ohara S, Sekine H, Iijima K, Abe Y, Kato K, Toyota T, Shimosegawa T. Helicobacter pylori infection prevents erosive reflux oesophagitis by decreasing gastric acid secretion. Gut. 2001;49:330–334. doi: 10.1136/gut.49.3.330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Raghunath A, Hungin AP, Wooff D, Childs S. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: systematic review. BMJ. 2003;326:737. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7392.737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Labenz J, Malfertheiner P. Helicobacter pylori in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: causal agent, independent or protective factor. Gut. 1997;41:277–280. doi: 10.1136/gut.41.3.277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bytzer P, Aalykke C, Rune S, Weywadt L, Gjørup T, Eriksen J, Bonnevie O, Bekker C, Kromann-Andersen H, Kjaergaard J, et al. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori compared with long-term acid suppression in duodenal ulcer disease. A randomized trial with 2-year follow-up. The Danish Ulcer Study Group. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2000;35:1023–1032. doi: 10.1080/003655200451135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Vakil N, Hahn B, McSorley D. Recurrent symptoms and gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in patients with duodenal ulcer treated for Helicobacter pylori infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14:45–51. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2000.00677.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.McColl KE, Dickson A, El-Nujumi A, El-Omar E, Kelman A. Symptomatic benefit 1-3 years after H. pylori eradication in ulcer patients: impact of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:101–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.01706.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Manes G, Mosca S, De Nucci C, Lombardi G, Lioniello M, Balzano A. High prevalence of reflux symptoms in duodenal ulcer patients who develop gastro-oesophageal reflux disease after curing Helicobacter pylori infection. Dig Liver Dis. 2001;33:665–670. doi: 10.1016/s1590-8658(01)80042-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Befrits R, Sjöstedt S, Odman B, Sörngård H, Lindberg G. Curing Helicobacter pylori infection in patients with duodenal ulcer does not provoke gastroesophageal reflux disease. Helicobacter. 2000;5:202–205. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5378.2000.00031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sasaki A, Haruma K, Manabe N, Tanaka S, Yoshihara M, Chayama K. Long-term observation of reflux oesophagitis developing after Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:1529–1534. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01643.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Laine L, Sugg J. Effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on development of erosive esophagitis and gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms: a post hoc analysis of eight double blind prospective studies. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2992–2997. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.07116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Sanduleanu S, Jonkers D, De Bruine A, Hameeteman W, Stockbrügger RW. Non-Helicobacter pylori bacterial flora during acid-suppressive therapy: differential findings in gastric juice and gastric mucosa. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15:379–388. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2001.00888.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.O'Connor HJ, Schorah CJ, Habibzedah N, Axon AT, Cockel R. Vitamin C in the human stomach: relation to gastric pH, gastroduodenal disease, and possible sources. Gut. 1989;30:436–442. doi: 10.1136/gut.30.4.436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Tatematsu M, Takahashi M, Fukushima S, Hananouchi M, Shirai T. Effects in rats of sodium chloride on experimental gastric cancers induced by N-methyl-N-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine or 4-nitroquinoline-1-oxide. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1975;55:101–106. doi: 10.1093/jnci/55.1.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Takahashi M, Hasegawa R. Enhancing effects of dietary salt on both initiation and promotion stages of rat gastric carcinogenesis. Princess Takamatsu Symp. 1985;16:169–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Fox JG, Dangler CA, Taylor NS, King A, Koh TJ, Wang TC. High-salt diet induces gastric epithelial hyperplasia and parietal cell loss, and enhances Helicobacter pylori colonization in C57BL/6 mice. Cancer Res. 1999;59:4823–4828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kono S, Hirohata T. Nutrition and stomach cancer. Cancer Causes Control. 1996;7:41–55. doi: 10.1007/BF00115637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.World Cancer Research Fund, American Institute for Cancer Research. Food, Nutrition and the Prevention of Cancer: a Global Perspective. Washington, D.C. American Institute for Cancer Research; 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ward MH, López-Carrillo L. Dietary factors and the risk of gastric cancer in Mexico City. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;149:925–932. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kim HJ, Chang WK, Kim MK, Lee SS, Choi BY. Dietary factors and gastric cancer in Korea: a case-control study. Int J Cancer. 2002;97:531–535. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Lee SA, Kang D, Shim KN, Choe JW, Hong WS, Choi H. Effect of diet and Helicobacter pylori infection to the risk of early gastric cancer. J Epidemiol. 2003;13:162–168. doi: 10.2188/jea.13.162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Joossens JV, Hill MJ, Elliott P, Stamler R, Lesaffre E, Dyer A, Nichols R, Kesteloot H. Dietary salt, nitrate and stomach cancer mortality in 24 countries. European Cancer Prevention (ECP) and the INTERSALT Cooperative Research Group. Int J Epidemiol. 1996;25:494–504. doi: 10.1093/ije/25.3.494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Tsugane S, Tsuda M, Gey F, Watanabe S. Cross-sectional study with multiple measurements of biological markers for assessing stomach cancer risks at the population level. Environ Health Perspect. 1992;98:207–210. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9298207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kato I, Tominaga S, Matsumoto K. A prospective study of stomach cancer among a rural Japanese population: a 6-year survey. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1992;83:568–575. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1992.tb00127.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Kneller RW, McLaughlin JK, Bjelke E, Schuman LM, Blot WJ, Wacholder S, Gridley G, CoChien HT, Fraumeni JF. A cohort study of stomach cancer in a high-risk American population. Cancer. 1991;68:672–678. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19910801)68:3<672::aid-cncr2820680339>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Nomura A, Grove JS, Stemmermann GN, Severson RK. A prospective study of stomach cancer and its relation to diet, cigarettes, and alcohol consumption. Cancer Res. 1990;50:627–631. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Tsugane S, Sasazuki S, Kobayashi M, Sasaki S. Salt and salted food intake and subsequent risk of gastric cancer among middle-aged Japanese men and women. Br J Cancer. 2004;90:128–134. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Buiatti E, Palli D, Decarli A, Amadori D, Avellini C, Bianchi S, Bonaguri C, Cipriani F, Cocco P, Giacosa A. A case-control study of gastric cancer and diet in Italy: II. Association with nutrients. Int J Cancer. 1990;45:896–901. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910450520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.La Vecchia C, Ferraroni M, D'Avanzo B, Decarli A, Franceschi S. Selected micronutrient intake and the risk of gastric cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1994;3:393–398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Hansson LE, Nyrén O, Bergström R, Wolk A, Lindgren A, Baron J, Adami HO. Nutrients and gastric cancer risk. A population-based case-control study in Sweden. Int J Cancer. 1994;57:638–644. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910570505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.McCullough ML, Robertson AS, Jacobs EJ, Chao A, Calle EE, Thun MJ. A prospective study of diet and stomach cancer mortality in United States men and women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2001;10:1201–1205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Hirayama T. A large scale cohort study on cancer risk by diet-with special reference to the risk reducing effects of green-yellow vegetable consumption. In: Hayashi Y, Nagao M, Sugimura T, editors. Diet, nutrition and cancer: proceedings of the 16th International Symposium of the Princess Takamatsu Cancer Research Fund. Utrecht: Tokyo/VNU Science; 1986. pp. 41–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Hertog MG, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB, Fehily AM, Sweetnam PM, Elwood PC, Kromhout D. Fruit and vegetable consumption and cancer mortality in the Caerphilly Study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1996;5:673–677. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Kobayashi M, Tsubono Y, Sasazuki S, Sasaki S, Tsugane S. Vegetables, fruit and risk of gastric cancer in Japan: a 10-year follow-up of the JPHC Study Cohort I. Int J Cancer. 2002;102:39–44. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Wang ZY, Cheng SJ, Zhou ZC, Athar M, Khan WA, Bickers DR, Mukhtar H. Antimutagenic activity of green tea polyphenols. Mutat Res. 1989;223:273–285. doi: 10.1016/0165-1218(89)90120-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Wang ZY, Hong JY, Huang MT, Reuhl KR, Conney AH, Yang CS. Inhibition of N-nitrosodiethylamine- and 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone-induced tumorigenesis in A/J mice by green tea and black tea. Cancer Res. 1992;52:1943–1947. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Xu Y, Ho CT, Amin SG, Han C, Chung FL. Inhibition of tobacco-specific nitrosamine-induced lung tumorigenesis in A/J mice by green tea and its major polyphenol as antioxidants. Cancer Res. 1992;52:3875–3879. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Setiawan VW, Zhang ZF, Yu GP, Lu QY, Li YL, Lu ML, Wang MR, Guo CH, Yu SZ, Kurtz RC, et al. Protective effect of green tea on the risks of chronic gastritis and stomach cancer. Int J Cancer. 2001;92:600–604. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Yu GP, Hsieh CC, Wang LY, Yu SZ, Li XL, Jin TH. Green-tea consumption and risk of stomach cancer: a population-based case-control study in Shanghai, China. Cancer Causes Control. 1995;6:532–538. doi: 10.1007/BF00054162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Ji BT, Chow WH, Yang G, McLaughlin JK, Gao RN, Zheng W, Shu XO, Jin F, Fraumeni JF, Gao YT. The influence of cigarette smoking, alcohol, and green tea consumption on the risk of carcinoma of the cardia and distal stomach in Shanghai, China. Cancer. 1996;77:2449–2457. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19960615)77:12<2449::AID-CNCR6>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Inoue M, Tajima K, Hirose K, Hamajima N, Takezaki T, Kuroishi T, Tominaga S. Tea and coffee consumption and the risk of digestive tract cancers: data from a comparative case-referent study in Japan. Cancer Causes Control. 1998;9:209–216. doi: 10.1023/a:1008890529261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Tsubono Y, Nishino Y, Komatsu S, Hsieh CC, Kanemura S, Tsuji I, Nakatsuka H, Fukao A, Satoh H, Hisamichi S. Green tea and the risk of gastric cancer in Japan. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:632–636. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200103013440903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Hoshiyama Y, Kawaguchi T, Miura Y, Mizoue T, Tokui N, Yatsuya H, Sakata K, Kondo T, Kikuchi S, Toyoshima H, et al. A prospective study of stomach cancer death in relation to green tea consumption in Japan. Br J Cancer. 2002;87:309–313. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Nagano J, Kono S, Preston DL, Mabuchi K. A prospective study of green tea consumption and cancer incidence, Hiroshima and Nagasaki (Japan) Cancer Causes Control. 2001;12:501–508. doi: 10.1023/a:1011297326696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Galanis DJ, Kolonel LN, Lee J, Nomura A. Intakes of selected foods and beverages and the incidence of gastric cancer among the Japanese residents of Hawaii: a prospective study. Int J Epidemiol. 1998;27:173–180. doi: 10.1093/ije/27.2.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Koizumi Y, Tsubono Y, Nakaya N, Kuriyama S, Shibuya D, Matsuoka H, Tsuji I. Cigarette smoking and the risk of gastric cancer: a pooled analysis of two prospective studies in Japan. Int J Cancer. 2004;112:1049–1055. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.González CA, Pera G, Agudo A, Palli D, Krogh V, Vineis P, Tumino R, Panico S, Berglund G, Simán H, et al. Smoking and the risk of gastric cancer in the European Prospective Investigation Into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) Int J Cancer. 2003;107:629–634. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Chao A, Thun MJ, Henley SJ, Jacobs EJ, McCullough ML, Calle EE. Cigarette smoking, use of other tobacco products and stomach cancer mortality in US adults: The Cancer Prevention Study II. Int J Cancer. 2002;101:380–389. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Franceschi S, La Vecchia C. Alcohol and the risk of cancers of the stomach and colon-rectum. Dig Dis. 1994;12:276–289. doi: 10.1159/000171463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Chow WH, Blot WJ, Vaughan TL, Risch HA, Gammon MD, Stanford JL, Dubrow R, Schoenberg JB, Mayne ST, Farrow DC, et al. Body mass index and risk of adenocarcinomas of the esophagus and gastric cardia. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90:150–155. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.2.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Vaughan TL, Davis S, Kristal A, Thomas DB. Obesity, alcohol, and tobacco as risk factors for cancers of the esophagus and gastric cardia: adenocarcinoma versus squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1995;4:85–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Clark GW, Smyrk TC, Burdiles P, Hoeft SF, Peters JH, Kiyabu M, Hinder RA, Bremner CG, DeMeester TR. Is Barrett's metaplasia the source of adenocarcinomas of the cardia. Arch Surg. 1994;129:609–614. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1994.01420300051007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Ishaq S, Jankowski JA. Barrett's metaplasia: clinical implications. World J Gastroenterol. 2001;7:563–565. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v7.i4.563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Lagergren J, Bergström R, Nyrén O. Association between body mass and adenocarcinoma of the esophagus and gastric cardia. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130:883–890. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-130-11-199906010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Calle EE, Rodriguez C, Walker-Thurmond K, Thun MJ. Overweight, obesity, and mortality from cancer in a prospectively studied cohort of U.S. adults. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1625–1638. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Thompson DE, Mabuchi K, Ron E, Soda M, Tokunaga M, Ochikubo S, Sugimoto S, Ikeda T, Terasaki M, Izumi S. Cancer incidence in atomic bomb survivors. Part II: Solid tumors, 1958-1987. Radiat Res. 1994;137:S17–S67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Hsing AW, Hansson LE, McLaughlin JK, Nyren O, Blot WJ, Ekbom A, Fraumeni JF. Pernicious anemia and subsequent cancer. A population-based cohort study. Cancer. 1993;71:745–750. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19930201)71:3<745::aid-cncr2820710316>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Aird I, Bentall HH, Roberts JA. A relationship between cancer of stomach and the ABO blood groups. Br Med J. 1953;1:799–801. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.4814.799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Stalnikowicz R, Benbassat J. Risk of gastric cancer after gastric surgery for benign disorders. Arch Intern Med. 1990;150:2022–2026. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Levine PH, Stemmermann G, Lennette ET, Hildesheim A, Shibata D, Nomura A. Elevated antibody titers to Epstein-Barr virus prior to the diagnosis of Epstein-Barr-virus-associated gastric adenocarcinoma. Int J Cancer. 1995;60:642–644. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910600513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Uemura Y, Tokunaga M, Arikawa J, Yamamoto N, Hamasaki Y, Tanaka S, Sato E, Land CE. A unique morphology of Epstein-Barr virus-related early gastric carcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1994;3:607–611. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Shousha S, Luqmani YA. Epstein-Barr virus in gastric carcinoma and adjacent normal gastric and duodenal mucosa. J Clin Pathol. 1994;47:695–698. doi: 10.1136/jcp.47.8.695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Palli D, Galli M, Caporaso NE, Cipriani F, Decarli A, Saieva C, Fraumeni JF, Buiatti E. Family history and risk of stomach cancer in Italy. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1994;3:15–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.La Vecchia C, Negri E, Franceschi S, Gentile A. Family history and the risk of stomach and colorectal cancer. Cancer. 1992;70:50–55. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19920701)70:1<50::aid-cncr2820700109>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Lissowska J, Groves FD, Sobin LH, Fraumeni JF, Nasierowska-Guttmejer A, Radziszewski J, Regula J, Hsing AW, Zatonski W, Blot WJ, et al. Family history and risk of stomach cancer in Warsaw, Poland. Eur J Cancer Prev. 1999;8:223–227. doi: 10.1097/00008469-199906000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.La Vecchia C, Negri E, D'Avanzo B, Franceschi S. Electric refrigerator use and gastric cancer risk. Br J Cancer. 1990;62:136–137. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1990.245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Trédaniel J, Boffetta P, Buiatti E, Saracci R, Hirsch A. Tobacco smoking and gastric cancer: review and meta-analysis. Int J Cancer. 1997;72:565–573. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19970807)72:4<565::aid-ijc3>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Suerbaum S, Michetti P. Helicobacter pylori infection. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1175–1186. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra020542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Coelho LG, Passos MC, Chausson Y, Costa EL, Maia AF, Brandao MJ, Rodrigues DC, Castro LP. Duodenal ulcer and eradication of Helicobacter pylori in a developing country. An 18-month follow-up study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1992;27:362–366. doi: 10.3109/00365529209000088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Uemura N, Mukai T, Okamoto S, Yamaguchi S, Mashiba H, Taniyama K, Sasaki N, Haruma K, Sumii K, Kajiyama G. Effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on subsequent development of cancer after endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1997;6:639–642. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Correa P, Fontham ET, Bravo JC, Bravo LE, Ruiz B, Zarama G, Realpe JL, Malcom GT, Li D, Johnson WD, et al. Chemoprevention of gastric dysplasia: randomized trial of antioxidant supplements and anti-helicobacter pylori therapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:1881–1888. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.23.1881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Wong BC, Lam SK, Wong WM, Chen JS, Zheng TT, Feng RE, Lai KC, Hu WH, Yuen ST, Leung SY, et al. Helicobacter pylori eradication to prevent gastric cancer in a high-risk region of China: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291:187–194. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.2.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Yuan JM, Ross RK, Gao YT, Qu YH, Chu XD, Yu MC. Prediagnostic levels of serum micronutrients in relation to risk of gastric cancer in Shanghai, China. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13:1772–1780. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Blot WJ, Li JY, Taylor PR, Guo W, Dawsey S, Wang GQ, Yang CS, Zheng SF, Gail M, Li GY. Nutrition intervention trials in Linxian, China: supplementation with specific vitamin/mineral combinations, cancer incidence, and disease-specific mortality in the general population. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:1483–1492. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.18.1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Varis K, Taylor PR, Sipponen P, Samloff IM, Heinonen OP, Albanes D, Härkönen M, Huttunen JK, Laxén F, Virtamo J. Gastric cancer and premalignant lesions in atrophic gastritis: a controlled trial on the effect of supplementation with alpha-tocopherol and beta-carotene. The Helsinki Gastritis Study Group. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1998;33:294–300. doi: 10.1080/00365529850170892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Jacobs EJ, Connell CJ, McCullough ML, Chao A, Jonas CR, Rodriguez C, Calle EE, Thun MJ. Vitamin C, vitamin E, and multivitamin supplement use and stomach cancer mortality in the Cancer Prevention Study II cohort. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002;11:35–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Wong BC, Zhu GH, Lam SK. Aspirin induced apoptosis in gastric cancer cells. Biomed Pharmacother. 1999;53:315–318. doi: 10.1016/S0753-3322(00)88503-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Sawaoka H, Tsuji S, Tsujii M, Gunawan ES, Sasaki Y, Kawano S, Hori M. Cyclooxygenase inhibitors suppress angiogenesis and reduce tumor growth in vivo. Lab Invest. 1999;79:1469–1477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Ristimäki A, Honkanen N, Jänkälä H, Sipponen P, Härkönen M. Expression of cyclooxygenase-2 in human gastric carcinoma. Cancer Res. 1997;57:1276–1280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Kelley DJ, Mestre JR, Subbaramaiah K, Sacks PG, Schantz SP, Tanabe T, Inoue H, Ramonetti JT, Dannenberg AJ. Benzo[a]pyrene up-regulates cyclooxygenase-2 gene expression in oral epithelial cells. Carcinogenesis. 1997;18:795–799. doi: 10.1093/carcin/18.4.795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Shirvani VN, Ouatu-Lascar R, Kaur BS, Omary MB, Triadafilopoulos G. Cyclooxygenase 2 expression in Barrett's esophagus and adenocarcinoma: Ex vivo induction by bile salts and acid exposure. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:487–496. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(00)70254-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Fu S, Ramanujam KS, Wong A, Fantry GT, Drachenberg CB, James SP, Meltzer SJ, Wilson KT. Increased expression and cellular localization of inducible nitric oxide synthase and cyclooxygenase 2 in Helicobacter pylori gastritis. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:1319–1329. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70496-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.McCarthy CJ, Crofford LJ, Greenson J, Scheiman JM. Cyclooxygenase-2 expression in gastric antral mucosa before and after eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:1218–1223. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Farrow DC, Vaughan TL, Hansten PD, Stanford JL, Risch HA, Gammon MD, Chow WH, Dubrow R, Ahsan H, Mayne ST, et al. Use of aspirin and other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and risk of esophageal and gastric cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1998;7:97–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Akre K, Ekström AM, Signorello LB, Hansson LE, Nyrén O. Aspirin and risk for gastric cancer: a population-based case-control study in Sweden. Br J Cancer. 2001;84:965–968. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2001.1702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Coogan PF, Rosenberg L, Palmer JR, Strom BL, Zauber AG, Stolley PD, Shapiro S. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and risk of digestive cancers at sites other than the large bowel. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2000;9:119–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Wang WH, Huang JQ, Zheng GF, Lam SK, Karlberg J, Wong BC. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use and the risk of gastric cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:1784–1791. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djg106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168.Kakizoe T. Cancer Statistics in Japan. Tokyo: Foundation for Promotion of Cancer Research; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 169.Guo HQ, Guan P, Shi HL, Zhang X, Zhou BS, Yuan Y. Prospective cohort study of comprehensive prevention to gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:432–436. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v9.i3.432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]