Abstract

In mammalian urorectal development, the urorectal septum (urs) descends from the ventral body wall to the cloaca membrane (cm) to partition the cloaca into urogenital sinus and rectum. Defective urs growth results in human congenital anorectal malformations (ARMs), and their pathogenic mechanisms are unclear. Recent studies only focused on the importance of urs mesenchyme proliferation, which is induced by endoderm-derived Sonic Hedgehog (Shh). Here, we showed that the programmed cell death of the apical urs and proximal cm endoderm is particularly crucial for the growth of urs during septation. The apoptotic endoderm was closely associated with the tempo-spatial expression of Wnt inhibitory factor 1 (Wif1), which is an inhibitor of Wnt-β-catenin signaling. In Wif1lacZ/lacZ mutant mice and cultured urorectum with exogenous Wif1, cloaca septation was defective with undescended urs and hypospadias-like phenotypes, and such septation defects were also observed in Shh−/− mutants and in endodermal β-catenin gain-of-function (GOF) mutants. In addition, Wif1 and Shh were expressed in a complementary manner in the cloaca endoderm, and Wif1 was ectopically expressed in the urs and cm associated with excessive endodermal apoptosis and septation defects in Shh−/− mutants. Furthermore, apoptotic cells were markedly reduced in the endodermal β-catenin GOF mutant embryos, which counteracted the inhibitory effects of Wif1. Taken altogether, these data suggest that regulated expression of Wif1 is critical for the growth of the urs during cloaca septation. Hence, Wif1 governs cell apoptosis of urs endoderm by repressing β-catenin signal, which may facilitate the protrusion of the underlying proliferating mesenchymal cells towards the cm for cloaca septation. Dysregulation of this endodermal Shh-Wif1-β-catenin signaling axis contributes to ARM pathogenesis.

Urorectal development starts at gestational week-4 in humans and at E10.5 in mice, and is divided into three phases: genital tubercle (GT) outgrowth, cloaca septation and urethra tubularization. GT outgrowth is initiated with a paired genital swellings on either side of the cloaca (caudal end of the rectum), which fuse medially to form the future external genitalia. Cloaca septation is the partitioning of the cloaca by urorectal septum (urs) into the rectum and urogenital sinuses (ugs). Urorectal development is indistinguishable in male and female embryos before urethra tubularization. Defective urorectal development results in a number of congenital anomalies frequently accompany with deficient excretory and copulatory functions, greatly influencing the patients' quality of life. In particular, the anorectal malformations (ARMs) are the most common urorectal defects and affect boys and girls with an incidence of 2–5 in 10 000 live births,1, 2 but its pathogenic mechanisms are poorly understood. ARM phenotypes are also partly included in several diseases, such as Currarino syndromes, Townes Brocks Syndromes and VACTERL complex, and these patients display other anomalies including anal fistula, sacral malformations and renal malformations.3, 4, 5, 6

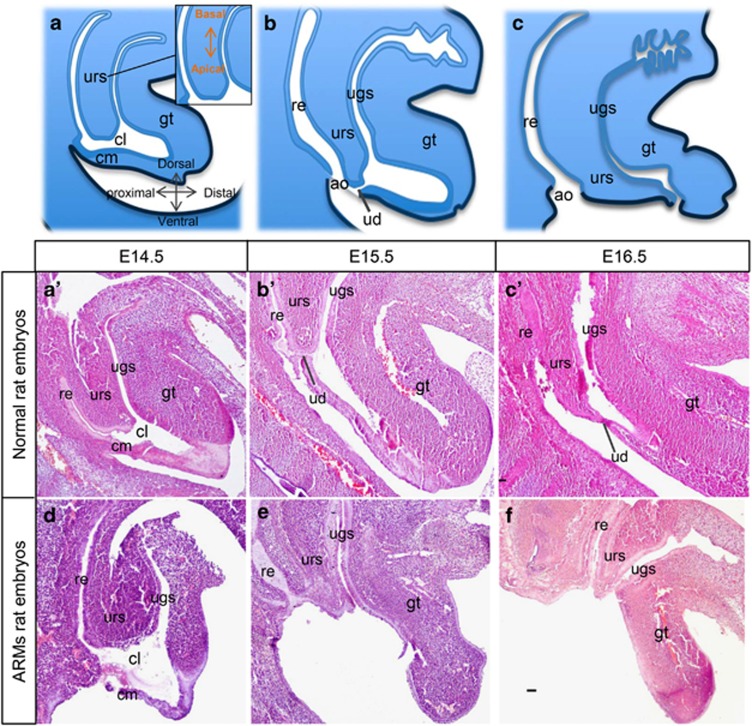

During cloaca septation, the urs, an endoderm-lined mesenchyme, elongates from the ventral body wall to the cloaca membrane (cm) (Figure 1a). The proximal cm is regressing when the apical urs endoderm approximates to the cm leading to the formation of the urethral duct (ud) and the anal opening, which signifies the completion of cloaca septation (Figure 1b). After septation, the cm regression associated with the proximal-to-distal urs elongation coupled with fusion of the preputial fold mesoderm along the ventral midline of the tubercle leads to the formation of urethral opening at the distal end of the GT (Figure 1c).

Figure 1.

Descent of the urorectal septum and regression of the cloaca membrane during cloaca septation. Schematic diagram of cloaca development showing the descent of urs and regression of proximal cm leads to anal opening after cloaca septation (a–c). Normal cloaca development in rat embryos from E14.5 to E16.5 (a′–c′). Rat treated with ethylenethiourea displayed persistent cloaca at E14.5 (d; n=12), hypospadias-like phenotypes with incomplete cloaca septation at E15.5 (e; n=15) and E16.5 (f); n=9). Scale bar: 50 μm

Deletion of Shh, Wnt5a or Bmp7 in mouse embryos resulted in reduced proliferation of the urs mesenchyme, incomplete urs elongation and septation defects.7, 8, 9, 10 In addition, the cm was either disintegrated or remained intact in these null embryos, giving rise to hypospadias-like or persistent cloaca phenotypes (Figure 1). Nonetheless, deletion of these genes not only leads to a decrease in cell proliferation but also affect cell apoptosis.11, 12

Shh and Wnt signaling are indispensable for the septation process. Shh is expressed in the cloaca endoderm and mediates the proliferation of urs mesenchyme through Gli2. Shh and Gli2 mutants displayed persistent cloaca. However, deletion of Shh eradicated the cm, exposing the unseptated cloaca exteriorly, whereas the cm remained intact in the loss of Gli2.7, 13 Wnt5a is crucial for urorectal development and regulates the outgrowth of GT.8, 10 Studies suggest that Wnt-β-catenin signaling activity is tightly regulated in urorectal development.14, 15 Furthermore, β-catenin expression was downregulated in Shh mutants.16 Constitutive activated β-catenin in Shh null background can partially rescue defective development of the GT and the cm.11, 16 All these indicated that Wnt-β-catenin signaling functions downstream of Shh. How Wnt signaling is regulated during cloaca septation has not been investigated.

Wif1 (Wnt inhibitory factor 1) is a secreted Wnt inhibitor, which exerts its inhibitory effect on Wnt signaling by binding directly to Wnt ligands and by preventing the ligands from binding to their cell surface receptors. The presence of Wif1 leads to β-catenin degradation, thereby turning off Wnt-β-catenin signaling.17 Most of the recent studies focused on the impact of epigenetic silencing of Wif1 in various carcinomas,18 and restoration of Wif1 activity in cancer cells induced apoptosis of malignant cancers.19 By contrast, reports on the regulatory functions of Wif1 in embryonic development are limited. Previous study suggested that Wif1 has high affinity to Wnt3a, Wnt4, Wnt5a, Wnt7a, Wnt9a and Wnt11;20 and Wif1 regulated chondrogenesis in cartilage-mesenchyme interfaces via the inhibition of Wnt3a-mediated mesenchyme growth in embryos.21 A recent study revealed that expression of Wif1 is androgen responsive in prostate bud formation. Loss of Wif1 in prostate glands induced ectopic expression of other secretory Wnt inhibitors to compensate for the loss of Wif1 activity in these mutants.22 Furthermore, Smad1 directly targets the Wif1 promoter and controls Wif1 gene expression in lung epithelial cell development.23 Taken all these indicated that Wnt-β-catenin signaling is precisely regulated in a number of embryonic developmental processes, and Wif1 modulates the Wnt-β-catenin signaling activity.

In this study, we discovered that the finely regulated expression of Wif1 is crucial for cloaca septation, and dysregulated Wif1 expression caused septation defects. Shh and Wif1 were expressed in a complementary manner at the cloaca endoderm, and deletion of Shh induced ectopic Wif1 expression, associated with excessive endoderm apoptosis and septation defects. Comparable septation defects were observed in Wif1lacZ/lacZ mutant mice, in cultured urorectum with exogenous Wif1, in Shh−/− mutants and in endodermal β-catenin GOF mutants. In conclusion, this study suggests that Wif1 regulates endodermal cell apoptosis by mediating and regulating Shh-Wnt-β-catenin signaling, thus having an essential role during urorectal development.

Results

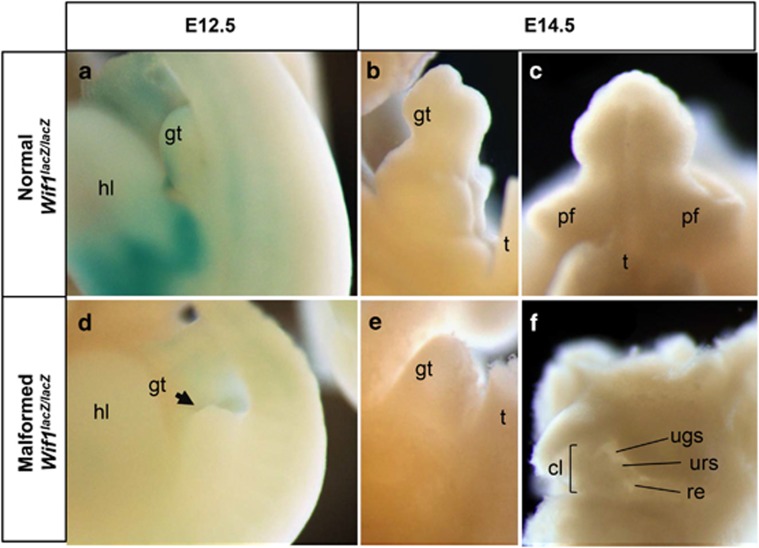

Wif1 is required for urorectal development

To assess the requirement of Wif1 in urorectal development, we examined the urorectal development in a transgenic knock-in mouse Wif1lacZ/lacZ.18 In the crossing of Wif1lacZ/lacZ mice, we repeatedly observed resorption of around 50% of embryos indicative of early embryo lethality (Supplementary Table 1). More importantly, about 5% of Wif1lacZ/lacZ mutants displayed gross anomalies including limb deformities, cranio-facial abnormalities and urorectal defects (Supplementary Figure 1). In Wif1lacZ/lacZ mutants, the external genitalia development was perturbed, and the ventral midline genital tubercle was malformed (Figures 2d and e). An apparent large hollow cloaca existed with cm disintegration (Figure 2f). It is therefore apparent that loss of Wif1 impedes normal urorectal development.

Figure 2.

Wif1 is crucial in urorectal development. Normally developed genital tubercle of Wif1lacZ/lacZ embryos at E12.5 (a) and E14.5 (b, c). Defective Wif1lacZ/lacZ embryos displayed perturbation of GT outgrowth and malformed genital tubercle at E12.5 (d) and E14.5 (e). Ventral view of the malformed GT at E14.5 showed the unseptated cloaca with a large hollow space and degraded ventral cloaca membrane (f)

Wif1 is dynamically expressed in the midline cloaca endoderm and complementary expressed with Shh during septation

To study the expression patterns of Wif1 in the developing cloaca, we performed immunohistochemical (IHC) staining on normal embryos and enzymatic staining for β-galactosidase of Wif1lacZ/lacZ embryos. Wif1 expression was first detected at the apical urs endoderm and cm at E11 (Figure 3a). Its expression level increased sharply in these regions by E12.5 when the urs endoderm was about to fuse with the cm. Apart from the cloaca endoderm, Wif1 was also expressed at the distal GT endoderm and the apical genital mesenchyme (Figure 3b). By E13.5, Wif1 expression decreased markedly after septation and the formation of urethral duct (ud) (Figure 3c). The expression pattern of Wif1 was also reconfirmed by β-galactosidase staining of Wif1lacZ/lacZ embryos (Supplementary Figure S2).

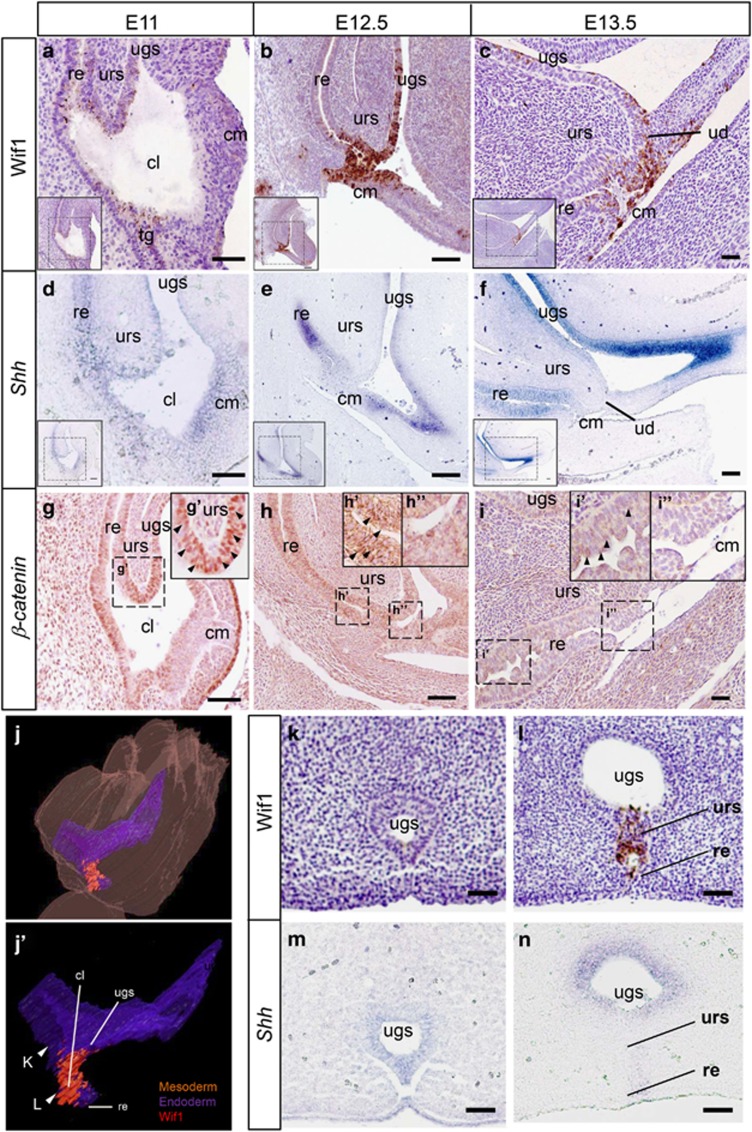

Figure 3.

Complementary expression pattern of Wif1 and Shh in the cloaca endoderm. Wif1 expression (brown) at the tip of the urs endoderm and the proximal cloaca membrane epithelium was increased from E11 (a) to E12.5 (b) before septation but reduced drastically at E13.5 (c). Shh expression (purple) in the cloaca endoderm and rectum endoderm showed a complementary expression pattern with Wif1. Shh was expressed at the entire cloaca endoderm by E11 (d). Shh was expressed at a very low level in urs and cloaca membrane endoderm, whereas Wif1 was expressed strongly at E12.5 (e) and E13.5 (f). Nuclear β-catenin immuno-reactivity (arrowheads) was localized in the apical urs endoderm when Wif1 expressed weak at E11 (g and g′). At E12.5 and E13.5, nuclear β-catenin immuno-reactivity was only detected in the basal urs endoderm (arrowheads) (h, h′ and i, i′) but not in the apical urs endoderm (h′′ and i′′). 3D reconstruction of Wif1 expression domains at E12.5 showed Wif1 expression in the midline of the septating cloaca (j and j′). Coronal sections of the distal and proximal region of the genital tubercle showed that Wif1 was not expressed in the distal midline ugs endoderm (k) but in the proximal midline endoderm (l). Expression of Shh was detected in the entire distal ugs endoderm (m), but its expression was absent in the proximal midline endoderm (n). White arrowheads indicate the plane of coronal sections. Regions highlighted were magnified as shown. Scale bar: 50 μm

Shh-expressing endoderm cells contribute to the entire urethra and hindgut.24 To investigate Shh expression pattern of these endoderm derivatives, we performed ISH and discovered that Shh was differentially expressed in the cloaca endoderm during cloaca septation. Shh was expressed in the cloaca endoderm by E11, whereas only weak Wif1 expression was detected (Figure 3d). By E12.5, Shh was expressed weakly in the apical urs endoderm and proximal cm endoderm, whereas Wif1 was strongly expressed (Figure 3e). After the septation was completed at E13.5, Shh expression remained weak in the apical urs endoderm and in the proximal cm (Figure 3f). In contrast, no Wif1 expression was detected in the endoderm, whereas Shh was strongly expressed. This indicates that Shh and Wif1 were expressed in a complementary manner in the cloaca endoderm from E11.5 to E13.5.

A 3-dimensional expression analysis revealed that the expression domains of Wif1 were localized at the midline cloaca endoderm of the canal connecting the urogenital sinus (ugs) and the rectum (re) of E12.5 urorectum (Figures 3j and j′). Shh was expressed in the entire distal ugs endoderm, whereas Wif1 was not expressed (Compare Figures 3k and m). In the cloaca, Shh was strongly expressed in the bilateral ugs endoderm but weakly at the midline urs endoderm and hg endoderm (Figure 3n). This indicated that there is tight complementary expression of Shh and Wif1 in the midline cloaca endoderm.

Restricted expression of Wif1 in the cloaca endoderm prompted us to examine whether Wnt signaling was suppressed in those Wif1-expressing regions. Immunostaining revealed that nuclear β-catenin was detected in the apical urs endoderm at E11 when Wif1 was weakly expressed (Figures 3g and g′). By E12.5 and E13.5, nuclear β-catenin signals were markedly reduced in the apical urs endoderm and proximal cm endoderm where Wif1 was strongly expressed (Figures 3h, h′′, I, i′). It is highly possible that the reduction in nuclear β-catenin was due to the inhibitory effect of Wif1 during septation.

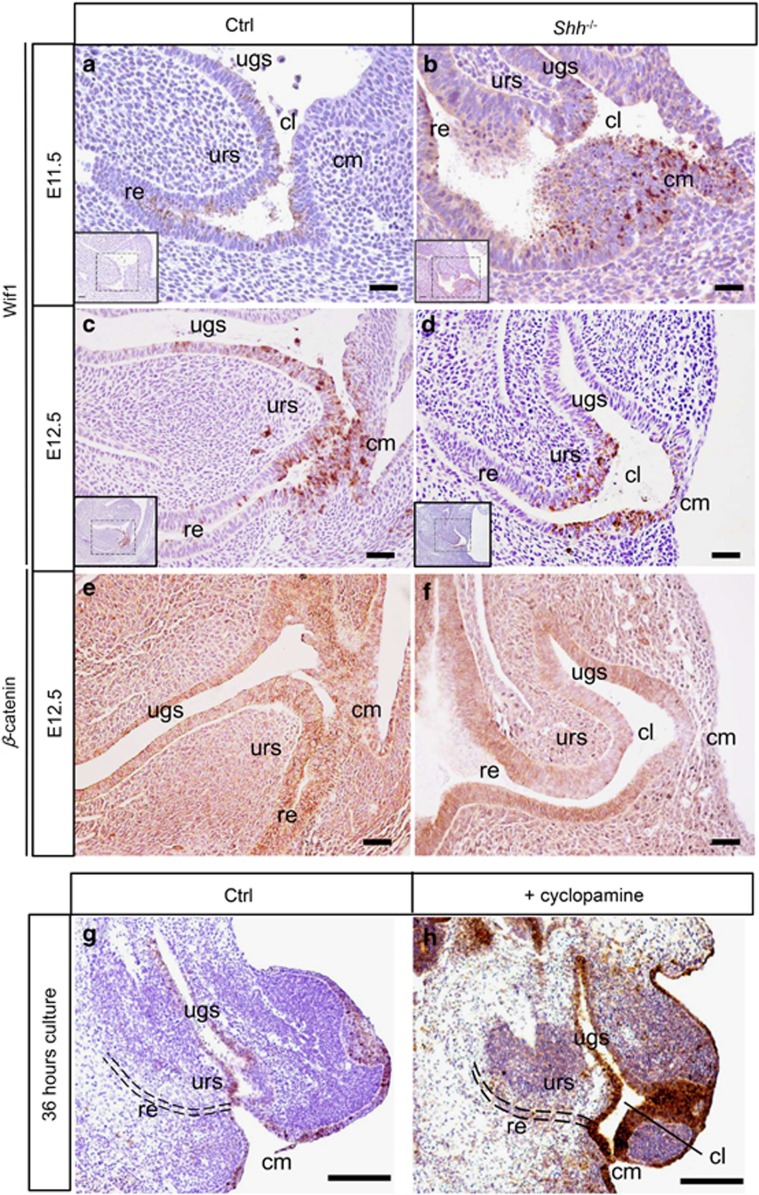

Next, we examined whether a deletion of Shh would affect Wif1 expression in the cloaca endoderm. Staged deletion of Shh in embryos elicited different urorectal defects ranging from external genitalia agenesis, persistent cloaca to hypospadias-like phenotypes.13 Deletion of Shh in embryos induced ectopic and precocious expressions of Wif1 in the urs endoderm and cm endoderm by E11.5 (Figure 4b). Cyclopamine inhibits Hh signaling by inactivating the transmembrane protein, Smoothened (Smo) and blockage of Shh in the GT explant caused GT agenesis.25, 26, 27 We could verify that cyclopamine induced GT outgrowth retardation and unseptated cloaca. More importantly, Wif1 was ectopically expressed in the entire cloaca endoderm and the surface ectoderm of cyclopamine-cultured urorectum (Figure 4h). In addition, both cytoplasmic and nuclear β-catenin immunostaining were further decreased in the Wif1-expressing endoderm in Shh mutant embryos (Figure 4f). Thus, disruption of Shh signaling disturbed the unique temporal spatial pattern of expression of Wif1 in the cloaca endoderm, in associate with defective urorectal development.

Figure 4.

In vivo and in vitro deletion of Shh elevated Wif1 expression. Wif1 was weakly expressed at E11.5 in control littermates (a). Deletion of Shh induced precocious Wif1 expression in the cloaca membrane endoderm and cloaca canal endoderm at E11.5 (b). By E12.5, a similar expression pattern of Wif1 was observed in both control (c) and Shh mutant embryos (d). However, the cm in Shh mutant was much thinner than the control embryo. Both cytoplasmic and nuclear β-catenin immunoreactivity decreased markedly in Shh mutant embryo (f) as compared with the control littermate (e). In vitro inhibition of Shh signaling by cyclopamine induced ectopic expression of Wif1 in the entire cloaca endoderm and surface ectoderm of the GT explant (h; n=5) compared with the control (g). Scale bar: 50 μm

Wif1 inhibited endodermal Wnt-β-catenin signaling and led to cloaca septation defects

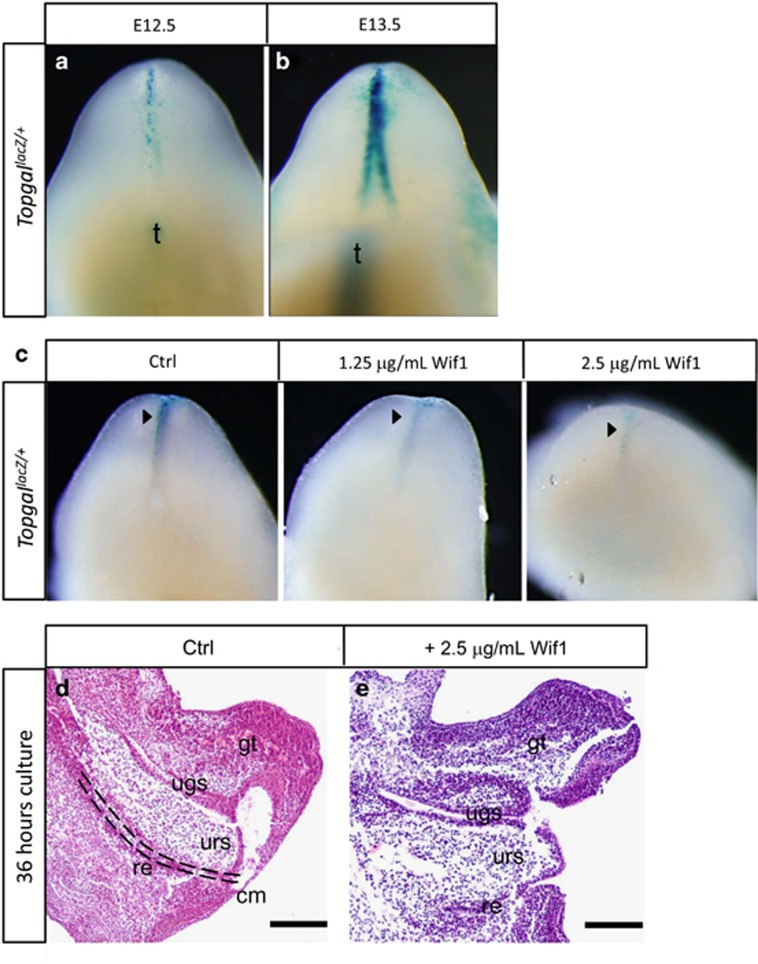

Active Wnt-β-catenin signaling can be localized by using a reporter transgenic mouse TopgallacZ. By E12.5, LacZ-positive cells indicated that Wnt-β-catenin signaling was active in the distal urethral epithelium (dUE). The Wnt-β-catenin signaling was absent in the proximal cm (Figure 5a). After septation was completed by E13.5, LacZ staining was even stronger in the dUE, but the proximal cm still remained LacZ-negative (Figure 5b).

Figure 5.

Exogenous Wif1 suppressed Wnt-β-catenin signaling in the developing midline urorectum. β-gal-positive cells in TopgallacZ/+ embryos were localized at the distal urethral epithelium at E12.5 (a) and E13.5 (b). GT explant from the TopgallacZ/+ embryos at E12 were cultured for 24 h with increasing concentrations of Wif1 protein. The number of β-gal-positive cells (arrowheads) decreased in explants cultured with higher concentration of Wif1 proteins (c). GT from the E12 TopgallacZ/+ embryos cultured for 36 h with exogenous Wif1 (1.5 μg/ml) displayed cloaca membrane disintegration and un-septated cloaca (e) compared with the control (d). Scale bar: 50 μm

To assess the impact of Wif1 on Wnt activity in urorectal epithelium and urorectal development, we cultured the E12 TopgallacZ/+ urorectum with exogenous mouse Wif1 protein for 24 h. Upon increasing doses of Wif1 protein, LacZ-positive cells were reduced in the dUE (Figure 5c). In the titration analysis, 2.5 μg/ml of Wif1 protein induced a marked reduction in LacZ activity in the dUE. We therefore repeated the culture with the Wif1 protein (2.5 μg/ml) and increased the incubation time to 36 h to examine whether exogenous Wif1 protein affected septation. Addition of Wif1 protein to the culture induced cm disintegration (Figure 5e), which was similar to the cm degradation defects in Shh−/− mutant embryos.8

Increased Wif1 expression enhanced cell apoptosis leading to cloaca membrane disintegration

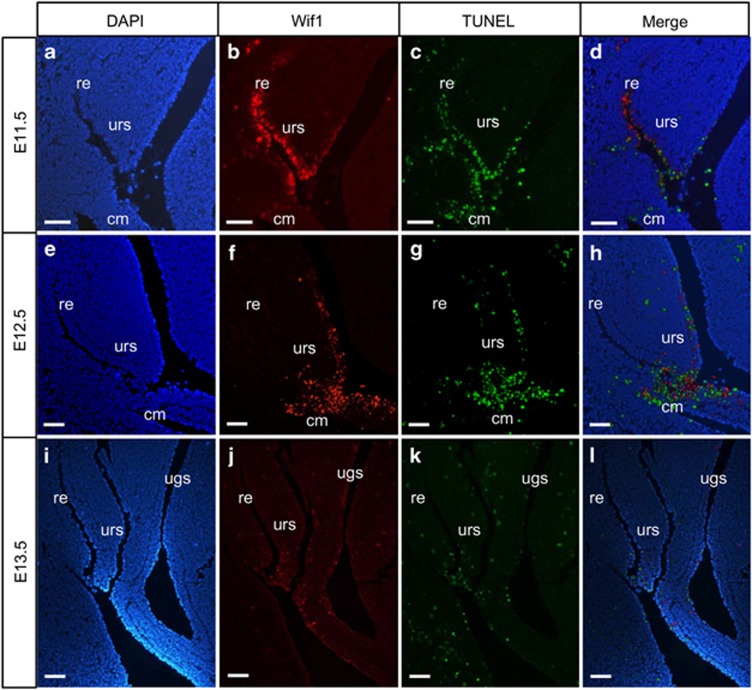

The cm is several cells thick at E10.5-11.5, the regressing proximal cm becomes a one-cell-thick epithelium by E13.5, and subsequently the proximal cm degenerates leading to the formation of the anal opening and the urethral duct. Wif1 expression was detected in the degrading proximal cm. This observation prompted us to study whether programmed cell death was linked to the proximal cm degradation and Wif1 expression. We performed TUNEL staining and immunofluorescence for Wif1 on mid-sagittal sections of the developing urorectum. Apoptotic cells were detected not only in the proximal cm but also in the apical urs endoderm. The number of apoptotic cells increased from E11.5 to E12.5 before septation (Figures 6c and g). Wif1-expressing cells in the cloaca endoderm were also TUNEL positive throughout the septation process from E11.5 to E13.5 (Figures 6d, h and l). Once the rectum was separated from the urogenital sinus, the number of apoptotic cells decreased and fewer cells showed Wif1 expression. These results suggested that Wif1 expression pattern was closely associated with cell apoptosis in the cloaca during septation.

Figure 6.

Wif1 colocalized with apoptotic endoderm cells during cloaca septation. AntiWif1 staining (Red) and TUNEL staining (Green) were colocalized in the urs tip endoderm and proximal cloaca membrane epithelium of the septating cloaca from E11.5 to E12.5 (a–h). The number of apoptotic cells decreased after cloaca septation together with the decrease in Wif1 expression level in the cloaca endoderm at E13.5 (i–l). Scale bar: 50 μm

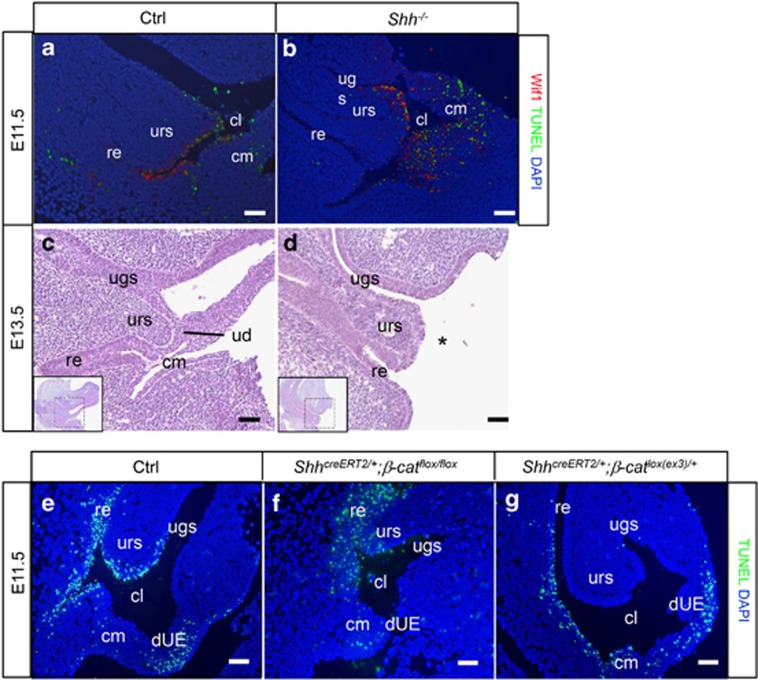

Given that inactivation of Shh and abnormal expression of Wif1 caused disintegration of the cm, we tested whether endodermal apoptosis increased in response to the precocious expression of Wif1 in Shh−/− mutant embryos. TUNEL staining and immunofluorescence staining for Wif1 indicated that cell apoptosis was increased in the cm of Shh−/− mice, where ectopic Wif1 expression was localized (Figures 7a and b). The cm disintegration in Shh−/− mutant embryos at E13.5 could be due to elevated cell apoptosis of the cm at the early stage of urorectal development (Figures 7c and d). This suggested that precocious Wif1 expression in cm led to early cm disintegration resulting in perineal urethra.

Figure 7.

Elevation of Wif1 expression increased cell apoptosis in the cloaca endoderm through Wnt-β-catenin signaling. Wif1 expression (Red) associated with cell apoptosis (Green) in wild-type embryo (a). Ectopic Wif1 expression domain (Red) in the cloaca membrane and at the tip of the urs colocalized with apoptotic cells (Green) in E11.5 ShhcreERT2/− mice (b). The cm was still intact at E13.5 in control embryos (c), whereas the cm was completely degraded at E13.5 resulting in perineal urethra in ShhcreERT2/− embryos (d). Asterisk indicates the absence of cm. Apoptotic cells (Green) in E11.5 wild-type control embryos (e), in mutant embryos with endodermal deletion of β-catenin (f) or with endodermal induction of constitutive active β-catenin (g) were localized by TUNEL. Scale bar: 50 μm

To study whether Wnt-β-catenin activity determines cell apoptosis in the cloaca endoderm, we used the ShhcreERT2/+;β-catflox embryos and ShhcreERT2/+;β-catlox(ex3) to examine the requirement of Wnt-β-catenin signaling on endodermal cell death during septation. β-catflox embryos contain two loxP sites flanking exon 3 and 6, and β-catenin loss-of-function (LOF) mutant was generated upon cre recombination. Constitutive active β-cateninlox(ex3) mutants (β-catenin gain-of-function (GOF)) served as a tool for studying the effects of increased endogenous β-catenin. LOF and GOF mutants were analyzed at E18.5 for urorectal development subsequent to TM treatment at E9.5. TM treatment at E9.5 induced robust Cre-recombination in the urs endoderm and the dUE (co-submitted MS: Miyagawa et al.). Both urs endodermal β-catenin loss-of-function (LOF) and gain-of-function (GOF) mutants induced by TM treatment at E9.5 displayed cleft-like phenotypes in their perineal region, but the growth of urs was not similarly affected in these mutants (co-submitted MS: Miyagawa et al.). The urs descended relatively normally and protruded out of the cloaca in the LOF mutants, but the urs failed completely to descend in the GOF mutants. As revealed by TUNEL staining, the number of apoptotic cells in the urs endoderm of β-catenin LOF mutants was comparable to that of control embryos (Figure 7f). At E11.5, the high level of endogenous Wif1 probably caused degradation of β-catenin and hence a very low level of β-catenin activity in the apical urs endoderm. Therefore, it was not unexpected that further deletion of β-catenin in the endoderm displayed no drastic effect on the apoptosis of these endoderm cells of β-catenin LOF mutants. By contrast, TUNEL-positive apoptotic cell were absent in the urs endoderm of the β-catenin GOF mutants (Figure 7g). Hyperactivation of Wnt-β-catenin signaling in the cloaca endoderm promoted cell survival. This supports our hypothesis that Wif1 inhibits Wnt signaling to induce apoptosis of the apical urs endoderm.

Discussion

Reciprocal interactions between the urs endoderm and the neighboring mesenchyme are critical for the urs development and cloaca septation. Endoderm-derived Shh integrates with Wnt-β-catenin signaling to regulate GT and urs development (co-submitted MS: Miyagawa et al.).14 However, it is not known how these two pathways coordinate to regulate the urs development for cloaca septation.

This study indicates that the elongation of the urs, regression of the cm and the formation of an anal opening depend on the activity of canonical Wnt signaling, which is regulated by Wif1, downstream of Shh in the urs endoderm. Disruption of these activities in mice dysregulates endodermal apoptosis and arrests the septation event causing cloacal defects, resembling human congenital anorectal malformations (ARMs).

Temporal-spatial expression of Wif1 is crucial for cloaca septation

The temporal-spatial expression of Wif1 at the midline cloaca endoderm of the canal linking the urogenital sinus and the rectum closely correlates with key events for cloaca septation including descent of the urs, midline fusion of the urs endoderm with the cm endoderm and degradation of the proximal cm.

Wif1 expression pattern associates with programmed cell death in the apical urs endoderm and the cm during septation. Colocalization of Wif1 expression and apoptosis was also observed in developing vertebrae and interdigit mesenchyme of the developing limb bud (data not shown), suggesting a causal relationship of Wif1 and programmed cell death during embryonic development. Furthermore, pro-apoptotic function of Wif1 has also been reported in cancer cells.19 Thus, ectopic and precocious Wif1 expression in Shh−/− urorectal region and cyclopamine-treated urorectum explant could induce aberrant programmed cell death of the cloaca and contribute to developmental defects of the urs and cm. We also discovered that ETU-induced ARMs rat embryos displayed ectopic Wif1 expression in the cloaca endoderm (Supplementary Figure S3). Taken together, these data indicated that finely regulated Wif1 expression is crucial for cloaca septation, ectopic Wif1 expression was linked to aberrant programmed cell death of the cloaca endoderm and extirpated cm disintegration and mal-developed urs.

Wif1 expression associated with the reduction in nuclear β-catenin of the apical urs endoderm and proximal cm, and Wif1 caused a reduction in the X-gal activity of TopgallacZ urorectum, indicating that Wif1 inhibited Wnt-β-catenin signaling in the developing urorectum. Wnt-β-catenin signaling promotes survival, whereas inhibition of Wnt-β-catenin signaling induced programmed cell death.28, 29, 30 A recent publication also indicated that secreted Wnt inhibitors promote apoptosis in embryonic development.31 Therefore, the ectopic and precocious expression of Wif1 in E11.5 Shh−/− embryos and cyclopamine-treated urorectum explant inhibited the Wnt-β-catenin signaling leading to aberrant cell death of the cloaca endoderm and the cm. The importance of the Wif1-mediated urs endodermal Wnt-β-catenin activity and cell death for cloaca septation was further supported by the lack of urs endodermal cell death and septation defects in β-catenin GOF mutants. Concomitantly with the ectopic induction of endoderm Wif1 expression in Shh−/− mutant, β-catenin signaling has also been shown to be reduced in the endoderm.16 In the E11.5 β-catenin GOF mutant embryos, the apical urs endoderm did not undergo apoptosis, instead the apical urs endoderm proliferated, and the urs failed to elongate to septate the cloaca (this study and co-submitted MS: Miyagawa et al.). The proliferation of the urs mesenchyme was only reduced at the later stage of septation at E13.5 in GOF mutants (co-submitted MS: Miyagawa et al.), suggesting that the proliferating urs mesenchyme per se was not sufficient to drive the early descent of urs. Therefore, midline cloaca endodermal cell death contributed to the septation process, and Wif1 induced programmed cell death by inhibiting Wnt-β-catenin activity.

A proportion of Wif1−/− mutant mice are normal and fertile, but develop bone tumors.18 This study showed that deletion of Wif1 caused early embryo lethality and anomalies in tissues that expressed Wif1 including the urorectum, albeit at incomplete penetrance, which indicated critical functions of Wif1 in embryo development. Wif1lacZ/lacZ mutants are genetically equivalent to the β-catenin GOF in urs, and perineal cleft phenotype of β-catenin GOF mutants are also observed in Wif1lacZ/lacZ mutants. However, around 45% of Wif1lacZ/lacZ mice develop normally, indicating that other Wnt inhibitors may be induced to compensate for the lack of Wif1 function in these normally developed Wif1lacZ/lacZ embryos as suggested elsewhere.22

During GT development, β-catenin expression in the endoderm was suggested as essential for the protrusion and proper morphogenesis.15, 16 The elongation defect of the urs in β-catenin LOF mutants could be attributed to the decreased cell proliferation in the urs mesenchyme (co-submitted MS: Miyagawa et al.). Thus, the cloaca septation defects in ETU-treated rats and in Wif1-treated urorectum could be mainly attributed to the reduced proliferation of the urs mesenchyme.

Our analysis highlights that Wif1 controls canonical Wnt signaling during septation; however, the possibility that Wif1 regulates noncanonical signaling during urorectal development cannot be totally excluded. Indeed, mutation of Ror2, a key component in the noncanonical Wnt signaling, caused defects similar as Wnt5a knockout embryos,32 suggesting a contribution of noncanonical Wnt signaling in urorectal development.

Endodermal patterning by Shh and Wif1

Endoderm-derived Shh promotes the mesenchyme proliferation essential for GT outgrowth and urs elongation, and proliferation defect of the mesenchyme due to defective Shh signaling contributes to urorectal defects in mice.13, 33 This study revealed that the endoderm at the apical urs expressed high level of Wif1 and low level of Shh, whereas the endoderm of the basal urs expressed only Shh and not Wif1. Such distinct endodermal expression patterns of Shh and Wif1 suggest a basal-apical (B-A) patterning of the urs endoderm. Ectopic and precocious expression of Wif1 in Shh−/− E11.5 embryos revealed that Shh negatively regulated Wif1 expression in the endoderm and suggested that B-A patterning defect of the urs endoderm also contributed to the abnormal septation in Shh−/− mice. Shh has been previously shown to repress the expression of Bmp4 at the dUE.15 The promoter of the Wif1 gene has a Smad binding site and phospho-Smad1 (downstream mediator of Bmp signaling) induced Wif1 expression in lung epithelial cells.23 Dorsomorphin selectively inhibits the BMP type I receptors and thus blocks BMP-mediated Smad1/5/8 phosphorylation.34, 35 Dorsomorphin caused a retardation of urs descent and septation defect in mouse urorectum, associated with a reduction of phosphorylation of Smad1 of the urorectal endoderm (Supplementary Figure S4). However, Wif1 expression of the endoderm was unaffected by dorsomorphin, which indicated that Shh regulation of Wif1 expression in the urorectal endoderm was not through Bmp.

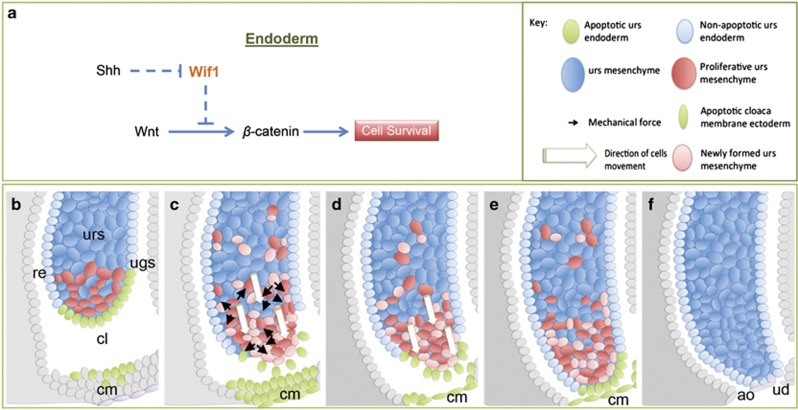

Endoderm-derived Shh modulates Wnt signaling activity by regulating Wif1 expression, and this endoderm Shh-Wif1-Wnt-β-catenin signaling axis may facilitate the descent of the urs for cloaca septation (Figures 8a–f). The urs mesenchyme cells proliferate producing new cells, and the increasing number of mesenchyme cells exerts outward mechanical force within the constrained urs endoderm. The Wif1-expressing apical urs endoderm undergoes apoptosis, which leaves a weaken endoderm boundary for the mesenchyme cells to relief such mechanical force constraint, facilitating the ‘directional elongation' of the urs toward the cm. Wif1 expression in the proximal cm induces cell death and cm regression to one-cell-thick epithelium. The cm is eventually peeled off forming the anal opening and the apical urs is exposed to the exterior forming the perineum, and ud is formed between the urs and the remaining cm.

Figure 8.

A model of signaling crosstalk regulating Wif1 and urs development. Evidence indicated that Wif1 is negatively regulated by Shh in the urs endoderm. The expression of Wif1 modulates the activity of Wnt-β-catenin signaling to control cell survival of the apical urs endoderm and cloaca membrane endoderm (a). A hypothetical mechanistic model to indicate how Wif1 facilitates the urs descent and cm degradation during cloaca septation (b–f)

In summary, both deletion of Wif1 (Wif1−/− mutants) or ectopic induction of Wif1 (Shh−/− mutants and ETU-treated rats) in the urs endoderm causes ARMs, but the differences of phenotypes are likely attributed to different pathogenic causes, which are in line with the complex pathogenic nature of ARMs. The identification of a duplication of another Wnt inhibitor gene DKK4 in patients with ARMs and that excess DKK4 caused ARM phenotype in culture urorectum36 further revealed the significance of the modulation of Wnt signaling by Wnt inhibitors for urorectal development. A synthetic chemical Di-n-butyl phthalate (DBP) is extensively used in industrial products and is also a common environment pollutant in many countries. DBP could be found in urine of women of childbearing age37 as well in blood, breast milk and urine of women undergoing parturition.38 In utero exposure to DBP caused ARMs in rats39, 40, 41 and patterning defects in zebrafish,42 with downregulation of Shh and Wnt signaling pathways. As Wif1 is dysregulated in Shh−/− embryo (curretnt study), it is not unexpected that Wif1 expression is also affected by DBP in rat embryos with ARMs. Taken together, our results indicate that endoderm Shh-Wif1-Wnt-β-catenin signaling must be precisely regulated and its dysregulation contributes to ARMs.

Materials and Methods

Animals

The mutant mice ShhcreERT2,43 Wif1lacZ/lacZ,18 TopgallacZ,44 β-catflox45 and β-catflox(ex3)46 were previously described. C57BL/6N mouse strain was used to maintain the genetic background and littermates were used as the control. Mice were kept under 12-h lights on/12-h dark cycle. For mating, male and female mice were housed together and the appearance of vaginal plugs in the morning was treated as embryonic day 0.5 (E 0.5). The tamoxifen (TM)-inducible Cre recombinase system removes the floxed sequence from the targeted allele.47 TM (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) was dissolved in sesame oil at 10 mg/ml. Four milligrams and 2 mg of TM per 40 g body weight were fed to ShhcreER;β-cateninflox and ShhcreER;β-cateninlox(ex3) pregnant female, respectively. Under these conditions, no overt teratological effect was detected in these embryos.

Urorectum culture

Urorectums of ICR and TopgallacZ/+ mouse embryos at E12 were dissected and cultured as described previously.36 Urorectums were cultured with BGJb medium with or without the addition of exogenous Wif1 protein (2.5 μg/ml; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) or Dorsomorphin (5 mM; Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA) and were incubated at 37 °C, 5% CO2.

Histology

Mouse embryos were fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA; w/v) in PBS, dehydrated through gradient ethanol, embedded in paraffin and 6 μm serial sections were prepared. Hematoxylin and eosin staining was processed according to standard protocol.

Immunohistochemical and Immunofluorescence staining

Embryos were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight and embedded in paraffin wax. Midsagittal sections (6 μm) or coronal sections (8 μm) were deparaffinized in xylene and hydrated in graded ethanol to water. Antigens were retrieved by incubating with 10 mM citrate buffer. Peroxidase was inactivated in 1.5% hydrogen peroxide/methanol. Sections were blocked with 1% BSA/PBS. Sections were then incubated with Goat anti-Wif1 (1:100; Santa Cruz Biotech Inc., Santa Cruz, CA, USA) and Rabbit anti-β-catenin (1 : 100; Cell signaling Tech. Inc., Beverly, MA, USA) at 4 °C overnight. For IHC analysis, sections were incubated with rabbit anti-goat (1 : 200; Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) and Mouse anti-rabbit (Dako) after stringency wash in PBS. Color was developed and then sections were counterstained with hematoxylin. For immunofluorescence, sections were incubated with AlexaFluor 594 Donkey anti-goat (1 : 200, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Sections were mounted in mounting solution containing DAPI (Vectalabs, Burlingame, CA, USA).

In situ hybridization

For section ISH, embryos were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, embedded in paraffin wax and sectioned in 6 μm. ISH was performed as previously described.16

X-gal staining

Embryos were fixed for 15 min in 4% paraformaldehyde and incubated in X-gal staining solution (40 mM potassium ferrocyanide, 40 mM potassium ferricyanide, 4 mM MgCl2, 1 mg/ml X-gal in DMSF) until optimal color developed. Samples were rinsed in PBS and post-fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and imaged under a dissection microscope. Embryos were then cryosectioned and imaged on a Nikon Eclipse E600 microscope.

TUNEL analysis

Hydrated sections were treated in Proteinase K (20 μg/ml) at 37 °C for 10 min. Reaction was stopped by 10 mM glycine solution. The sections were incubated with 50 μl mixture of TUNEL solution (Roche Diagnostic, Basel, Switzerland) at 37 °C for 1 h. Sections were mounted in mounting solution containing DAPI (Vectalabs).

3D-reconstruction

Serial coronal sections of the caudal region of mouse embryos were stained. The background color and color were edited by Adobe Photo element 7.0 Windows PC version. Edited photos were imported into 3D-doctor software (ABLE Software Corporation, Lexington, MA, USA) and aligned in position. 3-Dimension images of the urorectum were rendered by stacking up the serial orientated photos. All the parameters inputted followed the guidelines as described in the manufacturer manual.

ETU (ethylenethiourea) induction of ARMs in rat

ETU was dissolved in distilled water (1% wt/vol). Pregnant rats were fed with 1% ETU (125 mg/kg) at gestational day 11.5. Control rats were given same volume of water. E14.5 embryos were collected for histology or immunostaining for Wif1. The urorectal region of E14.5 embryos (both from control and ETU group) were dissected for mRNA preparation for GeneChip analysis or real-time RT-PCR verification.

Acknowledgments

We thank Igor B. Dawid (Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institute of Health, Bethesada, MD 20892, USA) for the Wif1lacZ/lacZ mice, and CC Hui for the Shh−/− mutant embryos at the initial stage of the study. This work was partly supported by the HKU Seed Funding for Basic Research (201111159048) to VCH Lui.

Glossary

- ARMs

anorectal malformations

- Ao

anal opening

- BMP

bone morphogenetic protein

- Cl

cloaca

- Cm

cloaca membrane

- Dkk

dickopf

- dUE

distal urethral epthelium

- fn

frontal nasal

- GOF

gain of function

- GT

genital tubercle

- Hl

hindlimb

- LOF

loss of function

- Pf

preputial fold

- Re

rectum

- Shh

sonic hedgehog

- T

tail

- Tg

tailgut

- Ud

urethral duct

- Ugs

urogenital sinus

- Urs

urorectal septum

- Wif1

Wnt inhibitory factor I

- Wnt

Wingless

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on Cell Death and Differentiation website (http://www.nature.com/cdd)

Edited by M Piacentini

Supplementary Material

References

- Levitt MA, Pena A. Anorectal malformations. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:33. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-2-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mundt E, Bates MD. Genetics of Hirschsprung disease and anorectal malformations. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2010;19:107–117. doi: 10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2009.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belloni E, Martucciello G, Verderio D, Ponti E, Seri M, Jasonni V, et al. Involvement of the HLXB9 homeobox gene in Currarino syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2000;66:312–319. doi: 10.1086/302723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohlhase J, Taschner PE, Burfeind P, Pasche B, Newman B, Blanck C, et al. Molecular analysis of SALL1 mutations in Townes-Brocks syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;64:435–445. doi: 10.1086/302238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohlhase J, Wischermann A, Reichenbach H, Froster U, Engel W. Mutations in the SALL1 putative transcription factor gene cause Townes-Brocks syndrome. Nat Genet. 1998;18:81–83. doi: 10.1038/ng0198-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Frias ML, Bermejo E, Frias JL. The VACTERL association: lessons from the Sonic hedgehog pathway. Clin Genet. 2001;60:397–398. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0004.2001.600515.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mo R, Kim JH, Zhang J, Chiang C, Hui CC, Kim PC. Anorectal malformations caused by defects in sonic hedgehog signaling. Am J Pathol. 2001;159:765–774. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61747-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seifert AW, Yamaguchi T, Cohn MJ. Functional and phylogenetic analysis shows that Fgf8 is a marker of genital induction in mammals but is not required for external genital development. Development. 2009;136:2643–2651. doi: 10.1242/dev.036830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X, Ferrara C, Shapiro E, Grishina I. Bmp7 expression and null phenotype in the urogenital system suggest a role in re-organization of the urethral epithelium. Gene Expression Patterns. 2009;9:224–230. doi: 10.1016/j.gep.2008.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi TP, Bradley A, McMahon AP, Jones S. A Wnt5a pathway underlies outgrowth of multiple structures in the vertebrate embryo. Development. 1999;126:1211–1223. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.6.1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin C, Yin Y, Veith GM, Fisher AV, Long F, Ma L. Temporal and spatial dissection of Shh signaling in genital tubercle development. Development. 2009;136:3959–3967. doi: 10.1242/dev.039768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu K, Wu X, Shapiro E, Huang H, Zhang L, Hickling D, et al. Bmp7 functions via a polarity mechanism to promote cloacal septation. PloS One. 2012;7:e29372. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seifert AW, Bouldin CM, Choi K-S, Harfe BD, Cohn MJ. Multiphasic and tissue-specific roles of sonic hedgehog in cloacal septation and external genitalia development. Development. 2009;136:3949–3957. doi: 10.1242/dev.042291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin C, Yin Y, Bell SM, Veith GM, Chen H, Huh SH, et al. Delineating a conserved genetic cassette promoting outgrowth of body appendages. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003231. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin C, Yin Y, Long F, Ma L. Tissue-specific requirements of beta-catenin in external genitalia development. Development. 2008;135:2815–2825. doi: 10.1242/dev.020586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyagawa S, Moon A, Haraguchi R, Inoue C, Harada M, Nakahara C, et al. Dosage-dependent hedgehog signals integrated with Wnt/beta-catenin signaling regulate external genitalia formation as an appendicular program. Development. 2009;136:3969–3978. doi: 10.1242/dev.039438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawano Y, Kypta R. Secreted antagonists of the Wnt signalling pathway. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:2627–2634. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kansara M, Tsang M, Kodjabachian L, Sims NA, Trivett M, Ehrich M, et al. Wnt inhibitory factor 1 is epigenetically silenced in human osteosarcoma, and targeted disruption accelerates osteosarcomagenesis in mice. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:837–851. doi: 10.1172/JCI37175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran I, Thavathiru E, Ramalingam S, Natarajan G, Mills WK, et al. Wnt inhibitory factor 1 induces apoptosis and inhibits cervical cancer growth, invasion and angiogenesis in vivo. Oncogene. 2012;31:2725–2737. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh JC, Kodjabachian L, Rebbert ML, Rattner A, Smallwood PM, Samos CH, et al. A new secreted protein that binds to Wnt proteins and inhibits their activities. Nature. 1999;398:431–436. doi: 10.1038/18899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surmann-Schmitt C, Widmann N, Dietz U, Saeger B, Eitzinger N, Nakamura Y, et al. Wif-1 is expressed at cartilage-mesenchyme interfaces and impedes Wnt3a-mediated inhibition of chondrogenesis. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:3627–3637. doi: 10.1242/jcs.048926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keil KP, Mehta V, Branam AM, Abler LL, Buresh-Stiemke RA, Joshi PS, et al. Wnt inhibitory factor 1 (Wif1) is regulated by androgens and enhances androgen-dependent prostate development. Endocrinology. 2012;153:6091–6103. doi: 10.1210/en.2012-1564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu B, Chen C, Chen H, Sheng SG, Bringas P, Xu M, et al. Smad1 and its target gene Wif1 coordinate BMP and Wnt signaling activities to regulate fetal lung development. Development. 2011;138:925–935. doi: 10.1242/dev.062687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seifert AW, Harfe BD, Cohn MJ. Cell lineage analysis demonstrates an endodermal origin of the distal urethra and perineum. Dev Biol. 2008;318:143–152. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JK, Taipale J, Cooper MK, Beachy PS. Inhibition of Hedgehog signaling by direct binding of cyclopamine to Smoothened. Genes Dev. 2002;16:2743–2748. doi: 10.1101/gad.1025302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haraguchi R, Mo R, Hui C, Motoyama J, Makino S, Shiroshi T, et al. Unique functions of Sonic hedgehog signaling during external genitalia development. Development. 2001;128:4241–4250. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.21.4241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima T, Iguchi T, Sato T. Hedgehog signaling plays roles in epithelial cell proliferation in neonatal mouse uterus and vagina. Cell Tissue Res. 2012;348:239–247. doi: 10.1007/s00441-012-1350-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodine PVN. Wnt signaling control of bone cell apoptosis. Cell Res. 2008;18:248–253. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewan KBR, Dale TC. The potential for targeting oncogenic WNT/beta-catenin signaling in therapy. Curr Drug Targets. 2008;9:532–547. doi: 10.2174/138945008784911787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han J, Sridevi P, Ramirez M, Ludwig KL, Wang JYJ. β-Catenin-dependent lysosomal targeting of internalized tumor necrosis factor-α suppresses caspase-8 activation in apoptosis-resistant colon cancer cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2013;24:465–473. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E12-09-0662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grotewold L, Rüther U. The Wnt antagonist Dickkopf-1 is regulated by Bmp signaling and c-Jun and modulates programmed cell death. EMBO J. 2002;21:966–975. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.5.966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwabe GC, Trepczik B, Süring K, Brieske N, Tucker AS, Sharpe P, et al. Ror2 knockout mouse as a model for the developmental pathology of autosomal recessive Robinow syndrome. Dev Dynamics. 2004;229:400–410. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seifert AW, Zheng Z, Ormerod BK, Cohn MJ. Sonic hedgehog controls growth of external genitalia by regulating cell cycle kinetics. Nat Commun. 2010;1:23. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu PB, Deng DY, Lai CS, Hong CC, Cuny GD, Bouxsein ML, et al. BMP type I receptor inhibition reduces heterotopic [corrected] ossification. Nat Med. 2008;14:1363–1369. doi: 10.1038/nm.1888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu PB, Hong CC, Sachidanandan C, Babitt JL, Deng DY, Hoyng SA, et al. Dorsomorphin inhibits BMP signals required for embryogenesis and iron metabolism. Nat Chem Biol. 2008;4:33–41. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2007.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong EHM, Cui L, Ng C-L, Tang CSM, Liu XL, So MT, et al. Genome-wide copy number variation study in anorectal malformations. Hum Mol Genet. 2013;22:621–631. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blount BC, Silva MJ, Caudill SP, Needham LL, Pirkie JL, Sampson EJ, et al. Levels of seven urinary phthalate metabolites in a human reference population. Environ Health Perspect. 2000;108:979–982. doi: 10.1289/ehp.00108979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JA, Liu H, Qiu Z, Shu W. Analysis of di-n-butyl phthalate and other organic pollutants in Chongqing women undergoing parturition. Environ Pollut. 2008;156:849–853. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2008.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang JT, Sun WL, Jing YF, Liu SB, Ma Z, Hong Y, et al. Prenatal exposure to di-n-butyl phthalate induces anorectal malformations in male rat offspring. Toxicology. 2011;290:322–326. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2011.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim TS, Jung KK, Kim SS, Kang IH, Baek JH, Nam HS, et al. Effects of in utero exposure to DI(n-Butyl) phthalate on development of male reproductive tracts in Sprague-Dawley rats. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2010;73:1544–1559. doi: 10.1080/15287394.2010.511579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu YJ, Jiang JT, Ma L, Zhang J, Hong Y, Liao K, et al. Molecular and toxicologic research in newborn hypospadiac male rats following in utero exposure to di-n-butyl phthalate (DBP) Toxicology. 2009;260:120–125. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2009.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairbairn EA, Bonthius J, Cherr GN. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and dibutyl phthalate disrupt dorsal-ventral axis determination via the Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway in zebrafish embryos. Aquat Toxicol. 2012;124–125:188–196. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2012.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harfe BD, Scherz PJ, Nissim S, Tian H, McMahon AP, Tabin CJ. Evidence for an expansion-based temporal Shh gradient in specifying vertebrate digit identities. Cell. 2004;118:517–528. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DasGupta R, Fuchs E. Multiple roles for activated LEF/TCF transcription complexes during hair follicle development and differentiation. Development. 1999;126:4557–4568. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.20.4557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huelsken J, Vogel R, Erdmann B, Cotsarelis G, Birchmeier W. beta-Catenin controls hair follicle morphogenesis and stem cell differentiation in the skin. Cell. 2001;105:533–545. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00336-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada N, Tamai Y, Ishikawa T, Sauer B, Takaku K, Oshima M, et al. Intestinal polyposis in mice with a dominant stable mutation of the beta-catenin gene. EMBO J. 1999;18:5931–5942. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.21.5931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feil R, Wagner J, Metzger D, Chambon P. Regulation of Cre recombinase activity by mutated estrogen receptor ligand-binding domains. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;237:752–757. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.