Abstract

Background

The incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) has continued to rise in recent years. This increase has been attributed to alcohol-induced liver diseases, metabolic syndrome, and the rising number of hepatitis B and C viral infections.

Methods

Pertinent publications (2000–2011) were retrieved by a systematic Medline search. In seven different subject areas, 41 key questions were defined; 15 of them were answered on the basis of a primary search. In addition, original-source guidelines that are currently available from around the world were assessed and utilized with the aid of a systematic instrument for the evaluation of guidelines (DELBI).

Results

All patients with chronic liver disease should undergo ultrasonography every six months for the early detection of HCC. Measurement of the alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) concentration is not obligatory, as this test is relatively insensitive when used for early detection. If ultrasonography reveals a mass, a tomographic imaging study with contrast should be obtained; the latter may reveal a characteristic pattern of contrast enhancement that can be accepted as definitive evidence of HCC. Fine-needle biopsy has a sensitivity and specificity of over 90% for the diagnosis of HCC. Any patient in whom HCC has been diagnosed should be referred to a center where potentially curative treatments (surgery, transplantation, local ablation) can be considered. Radiofrequency ablation (RFA) is now performed instead of percutaneous ethanol instillation. For patients with advanced tumors, sorafenib should only be offered to those in Child–Pugh stage A. This drug has been found to prolong mean overall survival from 7.9 to 10.7 months.

Conclusion

HCC poses particular diagnostic and therapeutic challenges that are best met with an interdisciplinary management approach.

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the fifth most frequent tumor worldwide, and the incidence of HCC in western countries has risen considerably in recent years (1). This increase can be attributed on one hand to the growing number of patients with hepatitis B and C, and on the other to the constantly high number of cases of alcohol-related liver disease (2). The epidemic of fatty liver disease, affecting an estimated 10 to 20 million persons in Germany alone, will lead to a further significant increase in the number of patients with HCC (3). These epidemiologic trends, together with the complexity of the treatment of HCC, prompted the German Society for Digestive and Metabolic Diseases (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Verdauungs- und Stoffwechselerkrankungen, DGVS) to take the lead in formulating a German guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of this disease. Alongside the classification of the roles of the various imaging modalities, a significant feature of the new guideline is the reintroduction of tumor biopsy for certain patients. Choice of the appropriate treatment procedure for the individual patient depends on the grade of liver cirrhosis and the stage of the tumor.

Method

Concept and development of guideline

The guideline development process began with determination of seven relevant topics. This was followed by a systematic search for international guidelines. Of 286 publications from the period October 2009 to January 2010, 51 were identified as potential source guidelines. Thirty-two of these publications were then analyzed using the German instrument for systematic guideline evaluation (DELBI). The guidelines of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) were chosen as source guideline (4). Furthermore, the S3 guidelines of the DGVS were used for diagnosis and treatment of hepatitis B and hepatitis C (5, 6).

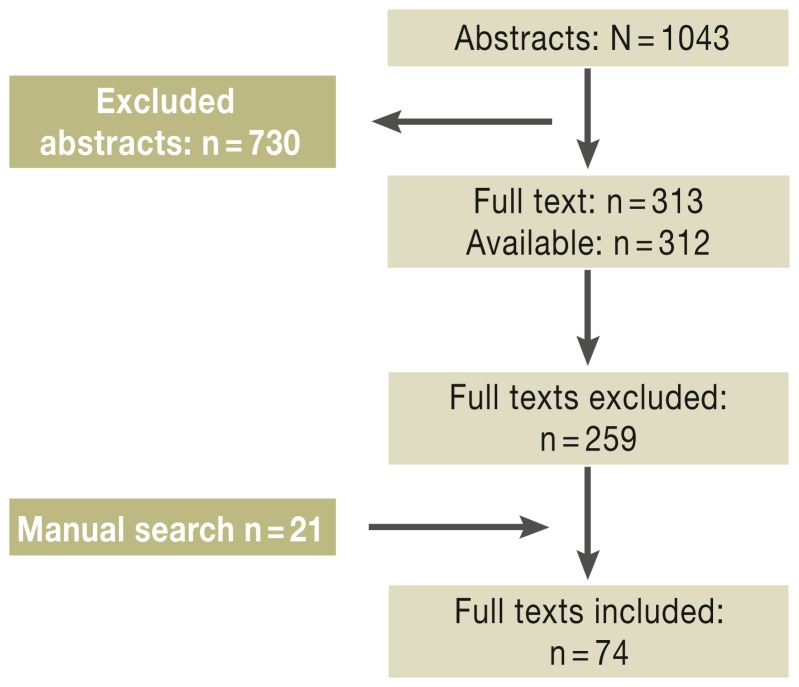

Fifteen of the 41 DELBI key questions were answered with the aid of primary research using the Medline database (survey period 1 January 2000 to 31 March 2011). A further nine publications were admitted on grounds of importance despite being published after 31 March 2011 (Figure 1, eBoxes 1 and 2).

Figure 1.

Survey of the literature. Reproduced by kind permission of Thieme-Verlag, Stuttgart from Greten TF, Malek NP, et al.: Diagnosis of and therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Z Gastroenterol 2013; 51: 1269–326

eBox 1.

More than 20 medical societies and over 100 individual experts cooperated in the development of this guideline between October 2009 and July 2012. The data were evaluated and processed by Dr. Helmut Sitter and his team at the Institute for Surgical Research of the Philipps University of Marburg. The guideline coordinators were Prof. Tim F. Greten (NIH), Prof. Nisar Peter Malek (University Hospital Tübingen), Dr. Sebastian Schmidt and Ms Petra Huber (both Hannover Medical School).

The database used was Medline. Publications in the period 1 January 2000 to 31 March 2011 were evaluated, plus nine studies (e1– e9) that were published after 31 March 2011 but judged too important to exclude.

A systematic survey of the answers to the 15 key questions led to identification of 1043 potentially relevant abstracts. These were then inspected by abstract screening and narrowed down to 313 publications for full-text analysis. Seven meta-analyses and 11 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were included.

eBox 2. Composition of the guideline working groups.

WG 1: Risk factors/screening/risk groups/prevention

Leaders:

Dr. A. Schuler, Geislingen

Prof. Dr. J. Trojan, Frankfurt

Prof. Dr. H. Wedemeyer, Hannover

Members:

PD Dr. T. Bernatik, Erlangen

Prof. Dr. F. Kolligs, Munich

Prof. Dr. C. Niederau, Oberhausen

PD Dr. V. Schmitz, Bonn

WG 2: Diagnosis and Classification

Leaders:

Dr. M. Dollinger, Ulm, Internal Medicine

Prof. Dr. T. Helmberger, Munich, Radiology

Dr. F. Lehner, Hannover, Surgery

Prof. Dr. P. Schirmacher, Heidelberg, Pathology

Members:

Prof. Dr. M. Bitzer, Tübingen, Internal Medicine

Prof. Dr. M. Düx, Frankfurt, Radiology

Dr. A. Schuler, Geislingen, DEGUM

Prof. Dr. D. Strobel, Erlangen, DEGUM

Prof. Dr. A. Tannapfel, Bochum, Pathology

Prof. Dr. C. Wittekind, Leipzig, Pathology

PD Dr. C. Zech, Munich, Radiology

WG 3: Curative procedures/ procedures limited to the liver

Leaders:

Prof. Dr. P. Huppert, Darmstadt, Radiology, transarterial procedures

Prof. Dr. P. Pereira, Heilbronn, Radiology, ablative procedures

Prof. Dr. H.-J. Schlitt, Regensburg, Surgery

PD Dr. S. Farkas, Regensburg, Surgery

Members:

Prof. Dr. P. Bartenstein, Munich

Prof. Dr. A. Chavan, Oldenburg

Prof. Dr. O. Drognitz, Freiburg

Prof. Dr. T. Greten, Bethesda, USA

Dr. D. Habermehl, Heidelberg

Prof. Dr. T. Helmberger, Munich

Prof. Dr. K. Herfarth, Heidelberg

Dr. R. T. Hoffmann, Munich

PD Dr. T. Jakobs, Munich

Prof. Dr. H. Lang, Mainz

PD Dr. A. Lubienski, Minden

Prof. Dr. A. Mahnken, Aachen

PD Dr. C. Mönch, Frankfurt

Prof. Dr. K. Schlottmann, Unna

PD Dr. D. Seehofer, Berlin

Prof. Dr. C. Straßburg, Hannover

Prof. Dr. C. Stroszczynski, Regensburg

Prof. Dr. F. Wacker, Hannover

WG 4: Systemic treatments/treatments not limited to the liver

Leaders:

Prof. Dr. M. Geißler, Esslingen

PD Dr. A. Vogel, Hannover

Members:

Prof. Dr. G. Folprecht, Dresden

Prof. Dr. F. Lordick, Braunschweig

Prof. Dr. N. Malek, Hannover

PD Dr. M. Möhler, Mainz

Prof. Dr. M. Ocker, Marburg

Dr. Schulze-Bergkamen, NCT, Heidelberg

Dr. A. Weinmann, Mainz

Prof. Dr. B. Wörmann, Berlin

WG 5: Supportive treatment (complementing WG 3 and WG 4)

Leader:

Dr. J. Körber, Bad Kreuznach

Members:

Dr. J. Arends, Freiburg

PD Dr. D. Domagk, Münster

PD Dr. M. Holtmann, Datteln

PD Dr. M. Keller, Heidelberg

Prof. Dr. G. Pott, Nordhorn

J. Riemer, Lebertransplantierte Deutschland e.V.

U. Ritterbusch, Konferenz Onkologische Krankenpflege

I. van Thiel, German Liver Aid (Deutsche Leberhilfe e.V.)

Members of the Expert Advisory Council:

Prof. Dr. P. Galle, Mainz

Prof. Dr. G. Gerken, Essen

Prof. Dr. H. Kreipe, Hannover

Prof. Dr. M.P. Manns, Hannover

Prof. Dr. P. Neuhaus, Berlin

Prof. Dr. G. Otto, Mainz

Prof. Dr. E. Rummeney, Munich

PD Dr. H. Wege, Hamburg

Risk factors, epidemiology, prevention

Patients with liver cirrhosis are at increased risk of developing HCC (7). Although the degree of risk varies widely depending on the reason for the cirrhosis (Table 1), the guideline group decided not to differentiate between the various etiologies. All patients with liver cirrhosis therefore constitute a risk group independent of pathogenesis.

Table 1. Regional frequency of risk factors for HCC*.

| Region | Risk factors (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HCV | HBV | Alcohol | Others | |

| Europe | 60–70 | 10–15 | 20 | 10 |

| North America | 50–60 | 20 | 20 | 10 (NASH) |

| Asia and Africa | 20 | 70 | 10 | 10 (aflatoxin) |

| Japan | 70 | 10–20 | 10 | 10 |

| Worldwide | 31 | 54 | 15 | – |

*Modified from Llovet et al. (14)

HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HBV, hepatitis B virus;

NASH, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis

An important new risk group is formed by patients with chronic hepatitis B infection, who have a much higher danger of developing HCC even in the absence of liver cirrhosis (7). The primary preventive role of vaccination against hepatitis B is proven beyond doubt (level of evidence [LoE] 1a). Particularly in endemic areas, hepatitis B vaccination can prevent HCC (4).

Hepatitis C-related liver cirrhosis is also a risk factor for HCC. Worldwide, 25% to 30% of cases of HCC can currently be attributed to hepatitis C virus infection (5).

In Germany, liver cirrhosis caused by drinking alcohol remains a crucial risk factor for the development of HCC. The assumption today is that one third of cases of HCC can be attributed to this cause (6). Men who consume >60 to 80 g alcohol/day over a 10-year period and women whose intake exceeds 20 g/day have a 6% to 41% risk of developing HCC (8, 9).

It is important to monitor patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), because this group has an elevated risk of developing HCC even without cirrhosis (LoE 2b) (10). The recent sharp rise in the number of patients with metabolic syndrome and diabetes mellitus and the associated obesity has already led to an increase in the incidence of HCC. The annual incidence of HCC in NASH patients is estimated at 2.6% (10). Treatment with metformin can reduce the risk of HCC in this group (LoE 3b), as shown by several retrospective and also prospective cohort studies (11, 12). Owing to the synergistic effects of various liver noxae in the genesis of HCC, the DGVS recommends abstention from alcohol, because alcohol consumption can lead to cirrhosis during the course of any kind of liver disease and accelerate the development of HCC (6).

Early detection

The clear connection between the existence of liver cirrhosis and occurrence of HCC means that early detection and monitoring of patients at risk is particularly important. It can be assumed that 90% of all HCC arise in patients with liver cirrhosis (13). At the same time, the prognosis of patients whose HCC was detected on screening is much better than the survival of those in whom HCC was diagnosed after the occurrence of symptoms (14). A randomized controlled study of patients with chronic hepatitis B showed that ultrasound examination lowered the mortality from 80% to 37% (15). In contrast, investigation of at-risk populations with an alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) tumor marker alone had sensitivity of only 55% with specificity of 87% (16). By comparison, ultrasound examination in an HCC screening program led to specificity of over 90% with sensitivity of between 60% and 90% (17). Because of the low sensitivity the guideline does not recommend regular measurement of AFP, but restricts the screening examination to half-yearly ultrasound controls. Abdominal sonography should be performed every 6 months in patients with:

Liver cirrhosis of Child–Pugh stage A or B, regardless of etiology

Chronic viral hepatitis

Steatohepatitis.

The screening examinations of an HCC early detection program should be carried out by suitably qualified physicians.

Diagnosis

A number of imaging procedures can be employed to detect HCC, all of which define the characteristic vascularization pattern of HCC as the essential diagnostic criterion. Particularly arterial hypervascularization with rapid flushing of contrast medium and relative contrast inversion to the surrounding liver parenchyma is considered to constitute sufficient proof of HCC (LoE 2b) in patients with underlying liver cirrhosis, chronic hepatitis B infection, or NASH (18– 20). The contrast-enhanced imaging modalities that can be used include not only CT and MRI but also contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) (Table 2).

Table 2. Comparison of imaging modalities.

| Modality | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Contrast-enhanced ultrasound | 50–86 | 79–100 |

| Contrast-enhanced CT | 44–87 | 95–100 |

| Contrast-enhanced MRI | 44–94 | 85–100 |

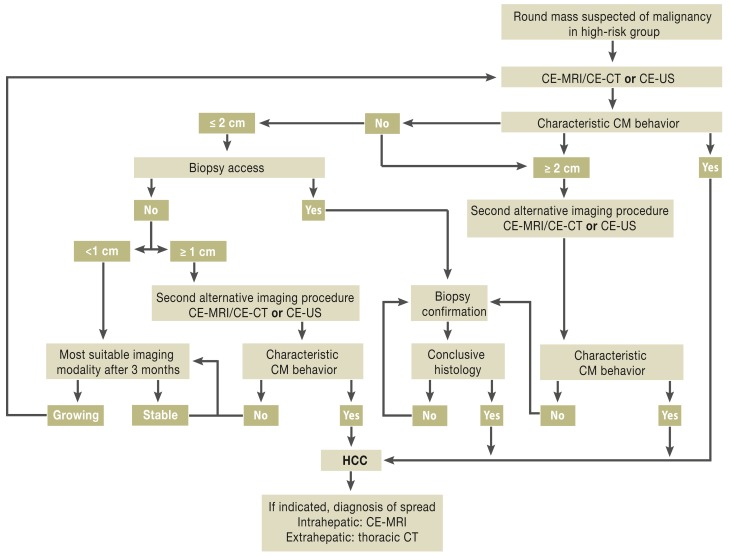

In contrast to the recommendation that AFP not be used for screening high-risk patients, determination of AFP can be useful after diagnosis of HCC (good clinical practice, GCP) (21, 22). If contrast-enhanced cross-sectional imaging detects no characteristic contrast behavior and the hepatic focus is <2 cm in diameter, the guideline recommends fine-needle aspiration biopsy of this round hepatic mass. The reason for this is that in tumors between 1 and 2 cm a second imaging procedure fails to increase the sensitivity and specificity and in 20% of cases leads to false-negative findings (18). Histological confirmation, however, achieves sensitivity and specificity of over 90% (23, 24). The diagnostic algorithm developed by the guideline group is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Diagnostic algorithm for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)

CE, contrast-enhanced; CM, contrast medium; CT, computed tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; US, ultrasound

Reproduced by kind permission of Thieme-Verlag, Stuttgart from Greten TF, Malek NP, et al.: Diagnosis of and therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma.

Z Gastroenterol 2013; 51: 1269–326

To have any prognostic relevance, a classification of HCC must describe not only the tumor stage but also liver function and the patient’s physical capacity. The system used most widely—and followed in preparation of the German guideline—is the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) classification, which integrates the above-mentioned parameters and permits division into various categories of treatment options (25). However, this division hampers direct comparison of individual treatment options.

Treatment options

A number of options are available for the treatment of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. All cases of HCC should be presented at an interdisciplinary tumor conference. It is essential to include discussion of the various forms of surgical treatment, in particular surgical resection and orthotopic liver transplantation. Therefore, patients in whom curative treatment is being considered or whose tumor has not progressed beyond the liver should be presented at a center with sufficient experience of liver surgery or transplantation.

Patients with liver cirrhosis

Liver transplantation is the treatment of choice for HCC in patients with liver cirrhosis who fulfill the Milan criteria (three tumor foci <3 cm or one focus <5 cm) (LoE 3). The 5-year survival rates are around 70%, and fewer than 15% of patients experience local recurrence (4).

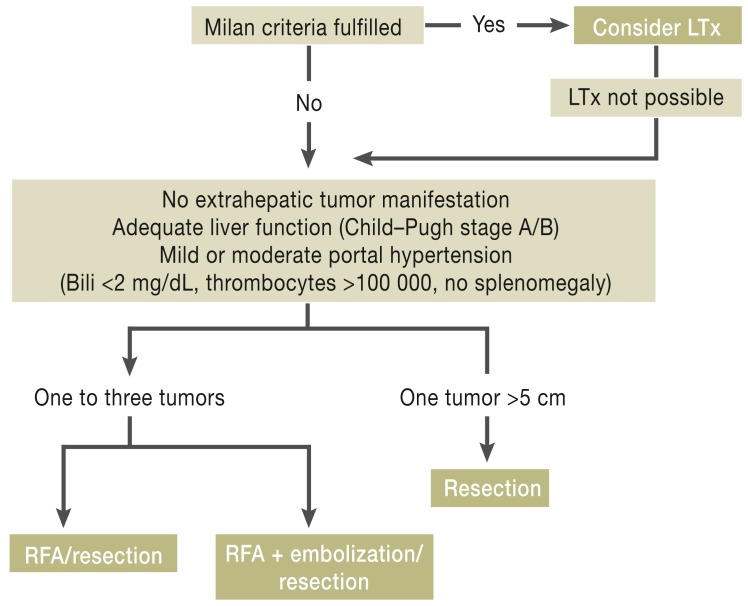

In patients who are not eligible for liver transplantation the treatment plan depends on the number and size of tumors present. Those with one to three tumors <3 cm and adequate liver function (Child–Pugh stage A or B) who have mild to moderate portal hypertension (bilirubin < 2 mg/dL, no splenomegaly, thrombocytes >100 000) can undergo radiofrequency ablation (RFA) or resection (GCP) (26). For patients with one to three tumors 3 to 5 cm in diameter who have adequate liver function and only mild portal hypertension, an interdisciplinary board can decide between RFA and resection. However, RFA should be preceded by embolization of the tumor foci (27). Patients with tumors >5 cm in size but adequate liver function and only mild portal hypertension can be treated by resection after presentation to the tumor board (GCP). In selected groups of patients treated in this way the 5-year survival rate is 30% to 50% (28). Nevertheless, a recurrence rate of up to 50% must be expected after resection of HCC in a cirrhotic liver (29).

With regard to the performance of local ablative procedures, the German guideline exclusively recommends RFA as standard method for percutaneous local ablation of HCC (LoE 2b). RFA has been shown to have overall good efficacy for the treatment of HCC foci in patients who fulfill the Milan criteria and whose liver function is preserved. It is a safe procedure with a low rate of complications and mortality of 0.5%. Bleeding complications, subcapsular hematomas, and injuries of the bile ducts or adjacent organs are very rare (30). Studies have shown 1-, 3-, and 5-year survival rates of 97%, 67%, and 41% with median survival of 49 months (31). Nevertheless, all studies report a higher rate of local recurrence for RFA than for resection. In the individual case, the decision between resection and ablation will be made according to the circumstances prevailing at the treatment center concerned. The recommended options for curative treatment depending on the size and number of tumors and the degree of portal hypertension are summarized in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Treatment algorithm

LTx, liver transplantation; Bili, bilirubin; RFA, radiofrequency ablation

Reproduced by kind permission of Thieme-Verlag, Stuttgart from Greten TF, Malek NP, et al.: Diagnosis of and therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Z Gastroenterol 2013; 51: 1269–326

Transarterial procedures

Transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) is an established component of the treatment algorithm for patients with advanced HCC. The guideline recommends TACE for patients in whom curative treatment is not an option and who display either solitary or multifocal HCC without extrahepatic involvement and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) stage <2 with liver cirrhosis of Child–Pugh stage A or B (LoE 1b) (32, 33).

Systemic metastases are not an absolute contraindication to chemoembolization, because lymph node involvement, for example, has no decisive influence on the patient’s prognosis (34). Segmental portal vein thrombosis is also not necessarily a contraindication to TACE (GCP). In principle, TACE is superior to purely supportive therapy in patients with advanced HCC and adequate liver function. This is not true, however, for patients with Child–Pugh stage C; this group should not be offered treatment other than best supportive care, because the underlying liver function is the sole factor determining the prognosis in these patients.

It obviously makes sense to prescribe antiemetics and analgesics to prevent the occurrence of postembolization syndrome (pain, nausea, vomiting, fever).

To date there is no standardized procedure for chemoembolization. For this reason, the guideline describes the technique in detail and recommends the procedure always be conducted with maximal selectivity and due attention to the vascularization pattern of the tumor foci. In any case, TACE is a procedure that should be carried out as many times as may be necessary to achieve the maximum benefit for the patient (35). Selective intracellular radiotherapy (SIRT) has been adopted at various centers in recent years and a few clinical studies have been published that compared SIRT with conventional TACE, but SIRT is not yet a standard procedure for treatment of HCC.

Systemic treatment

The multikinase inhibitor sorafenib is currently the only licensed treatment for metastasized or locally uncontrollable HCC. In the SHARP study, sorafenib increased the duration of overall survival from 7.9 to 10.7 months compared with placebo. The principal adverse effects of sorafenib treatment are hand–foot syndrome, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, deterioration of liver function, and in rare cases gastrointestinal bleeding. The meta-analyses published to date show that sorafenib prolongs progression-free survival and overall survival. However, no advantage of sorafenib has yet been shown for patients with Child–Pugh stage B liver cirrhosis. Therefore, the guideline recommends treatment with sorafenib only for patients with good liver function (Child–Pugh stage A) and good general health (ECOG 0 to 2) (LoE 1a) (36, 37). Continuation of sorafenib treatment after symptomatic or radiologic disease progression does not seem advisable. There are currently no other options for systemic treatment. Numerous new substances are being tested for treatment of HCC, and high priority should be accorded to inclusion of patients in these studies.

Summary

The new guideline gives wide-reaching recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of HCC. However, a great deal of effort still needs to be invested in the development of new options for systemic treatment, with the aim of improving the survival of patients with advanced disease. The introduction of predictive markers that could lead to personalization of the treatment of patients with HCC represents another important area of future research.

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by David Roseveare.

The preparation of the guideline was funded by German Cancer Aid through its Oncology Guideline Program.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

Prof. Malek has received payments for lectures from Bayer and consultation fees from Lilly.

Prof. Manns has received payments from Boehringer Ingelheim and BMS for his activities as advisory board member. He has benefited from third-party funding of studies by Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, BMS, Novartis, Pfizer, and Transgene.

The remaining authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:2893–2917. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Starley BQ, Calcagno CJ, Harrison SA. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma: a weighty connection. Hepatology. 2010;51:1820–1832. doi: 10.1002/hep.23594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang MH, Chen CJ, Lai MS, et al. Universal hepatitis B vaccination in Taiwan and the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in children. Taiwan Childhood Hepatoma Study Group. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1997;336:1855–1859. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199706263362602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perz JF, Armstrong GL, Farrington LA, Hutin YJ, Bell BP. The contributions of hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus infections to cirrhosis and primary liver cancer worldwide. Journal of Hepatology. 2006;45:529–538. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hassan MM, Hwang LY, Hatten CJ, et al. Risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma: synergism of alcohol with viral hepatitis and diabetes mellitus. Hepatology. 2002;36:1206–1213. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.36780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bruix J, Sherman M. American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases: Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: an update. Hepatology. 2011;53:1020–1022. doi: 10.1002/hep.24199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mandayam S, Jamal MM, Morgan TR. Epidemiology of alcoholic liver disease. Seminars in Liver Disease. 2004;24:217–232. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-832936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lu XL, Luo JY, Tao M, et al. Risk factors for alcoholic liver disease in China. World journal of gastroenterology. WJG. 2004;10:2423–2426. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i16.2423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ascha MS, Hanouneh IA, Lopez R, Tamimi TA, Feldstein AF, Zein NN. The incidence and risk factors of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology. 2010;51:1972–1978. doi: 10.1002/hep.23527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Donadon V, Balbi M, Mas MD, Casarin P, Zanette G. Metformin and reduced risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in diabetic patients with chronic liver disease. Liver International. Official Journal of the International Association for the Study of the Liver. 2010;30:750–758. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2010.02223.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lai SW, Chen PC, Liao KF, Muo CH, Lin CC, Sung FC. Risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in diabetic patients and risk reduction associated with anti-diabetic therapy: a population-based cohort study. The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2012;107:46–52. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.El-Serag HB. Hepatocellular carcinoma. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2011;365:1118–1127. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1001683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Llovet JM, Burroughs A, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet. 2003;362:1907–1917. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14964-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang BH, Yang BH, Tang ZY. Randomized controlled trial of screening for hepatocellular carcinoma. Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology. 2004;130:417–422. doi: 10.1007/s00432-004-0552-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen JG, Parkin DM, Chen QG, et al. Screening for liver cancer: results of a randomised controlled trial in Qidong, China. Journal of Medical Screening. 2003;10:204–209. doi: 10.1258/096914103771773320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bolondi L. Screening for hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhosis. Journal of Hepatology. 2003;39:1076–1084. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(03)00349-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khalili K, Kim TK, Jang HJ, et al. Optimization of imaging diagnosis of 1-2 cm hepatocellular carcinoma: an analysis of diagnostic performance and resource utilization. Journal of Hepatology. 2011;54:723–728. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim JE, Kim SH, Lee SJ, Rhim H. Hypervascular hepatocellular carcinoma 1 cm or smaller in patients with chronic liver disease: characterization with gadoxetic acid-enhanced MRI that includes diffusion-weighted imaging. AJR American Journal of Roentgenology. 2011;196:W758–W765. doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.4394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Forner A, Vilana R, Ayuso C, et al. Diagnosis of hepatic nodules 20 mm or smaller in cirrhosis: Prospective validation of the noninvasive diagnostic criteria for hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2008;47:97–104. doi: 10.1002/hep.21966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.N’Kontchou G, Mahamoudi A, Aout M, et al. Radiofrequency ablation of hepatocellular carcinoma: long-term results and prognostic factors in 235 Western patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2009;50:1475–1483. doi: 10.1002/hep.23181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kobayashi M, Hosaka T, Ikeda K, et al. Highly sensitive AFP-L3% assay is useful for predicting recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma after curative treatment pre- and postoperatively. Hepatol Res. 2011;41:1036–1045. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2011.00858.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Herszenyi L, Farinati F, Cecchetto A, et al. Fine-needle biopsy in focal liver lesions: the usefulness of a screening programme and the role of cytology and microhistology. Ital J Gastroenterol. 1995;27:473–478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Caturelli E, Bisceglia M, Fusilli S, Squillante MM, Castelvetere M, Siena DA. Cytological vs microhistological diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma: comparative accuracies in the same fine-needle biopsy specimen. Digestive Diseases and Sciences. 1996;41:2326–2331. doi: 10.1007/BF02100122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Llovet JM, Bru C, Bruix J. Prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma: the BCLC staging classification. Seminars in Liver Disease. 1999;19:329–338. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1007122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Benson AB, 3rd, Abrams TA, Ben-Josef E, et al. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: hepatobiliary cancers. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. JNCCN. 2009;7:350–391. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2009.0027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peng ZW, Zhang YJ, Liang HH, Lin XJ, Guo RP, Chen MS. Recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma treated with sequential transcatheter arterial chemoembolization and RF ablation versus RF ablation alone: a prospective randomized trial. Radiology. 2012;262:689–700. doi: 10.1148/radiol.11110637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gouillat C, Manganas D, Saguier G, Duque-Campos R, Berard P. Resection of hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhotic patients: longterm results of a prospective study. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 1999;189:282–290. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(99)00142-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eguchi S, Kanematsu T, Arii S, et al. Recurrence-free survival more than 10 years after liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma. The British Journal of Surgery. 2011;98:552–557. doi: 10.1002/bjs.7393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mulier S, Mulier P, Ni Y, et al. Complications of radiofrequency coagulation of liver tumours. The British Journal of Surgery. 2002;89:1206–1222. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2002.02168.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lencioni R, Cioni D, Crocetti L, et al. Early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with cirrhosis: long-term results of percutaneous image-guided radiofrequency ablation. Radiology. 2005;234:961–967. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2343040350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Llovet JM, Real MI, Montana X, et al. Arterial embolisation or chemoembolisation versus symptomatic treatment in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;359:1734–1739. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08649-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lo CM, Ngan H, Tso WK, et al. Randomized controlled trial of transarterial lipiodol chemoembolization for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2002;35:1164–1171. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.33156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huppert PE, Lauchart W, Duda SH, et al. [Chemoembolization of hepatocellular carcinomas: which factors determine therapeutic response and survival?]. RoFo. Fortschritte auf dem Gebiete der Rontgenstrahlen und der Nuklearmedizin. 2004;176:375–385. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-812776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marelli L, Stigliano R, Triantos C, et al. Transarterial therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma: which technique is more effective? A systematic review of cohort and randomized studies. Cardiovascular and interventional radiology. 2007;30:6–25. doi: 10.1007/s00270-006-0062-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cheng AL, Kang YK, Chen Z, et al. Efficacy and safety of sorafenib in patients in the Asia-Pacific region with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a phase III randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. The Lancet Oncology. 2009;10:25–34. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70285-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, et al. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2008;359:378–390. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0708857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e1.Lai SW, et al. Risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in diabetic patients and risk reduction associated with anti-diabetic therapy: a population-based cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:46–52. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e2.Khalili K, et al. Optimization of imaging diagnosis of 1-2 cm hepatocellular carcinoma: an analysis of diagnostic performance and resource utilization. J Hepatol. 2011;54:723–728. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e3.Kim JE, et al. Hypervascular hepatocellular carcinoma 1 cm or smaller in patients with chronic liver disease: characterization with gadoxetic acid-enhanced MRI that includes diffusion-weighted imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;196:758–765. doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.4394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e4.Baek CK, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic liver disease: a comparison of gadoxetic acid-enhanced MRI and multiphasic MDCT. Clin Radiol. 2012;67:148–156. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2011.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e5.Addley HC, et al. Accuracy of hepatocellular carcinoma detection on multidetector CT in a transplant liver population with explant liver correlation. Clin Radiol. 2011;66:349–356. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2010.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e6.Peng ZW, et al. Recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma treated with sequential transcatheter arterial chemoembolization and RF ablation versus RF ablation alone: a prospective randomized trial. Radiology. 2012;262:689–700. doi: 10.1148/radiol.11110637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e7.Kim JH, et al. Medium-sized (31-5.0 cm) hepatocellular carcinoma: transarterial chemoembolization plus radiofrequency ablation versus radiofrequency ablation alone. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18:1624–1629. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-1673-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e8.Pinter M, et al. Prognostic factors in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma treated with sorafenib. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34:949–959. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04823.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e9.Hollebecque A, et al. Safety and efficacy of sorafenib in hepatocellular carcinoma: the impact of the Child-Pugh score. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34:1193–1201. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04860.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]