Abstract

Long non-coding (lnc)RNAs are emerging key factors in the regulation of various cellular processes. In the nucleus, these include the organization of nuclear sub-structures, the alteration of chromatin state, and the regulation of gene expression through the interaction with effector proteins and modulation of their activity. Collectively, lncRNAs form the core of attractive models explaining aspects of structural and dynamic regulation in the nucleus across time and space. Here we review recent studies that characterize the molecular function of a subset of these molecules in the regulation and fine-tuning of nuclear state.

Introduction

The nucleus is a highly structured cellular compartment that most prominently serves the organization and regulation of chromatin-associated processes, including DNA replication, transcription, RNA processing and RNA export (for recent review, see [1–4]). Assembly and organization of nuclear sub-structures, and the spatio-temporal coordination of nuclear processes, need to be tightly controlled to ensure efficient cellular function and metabolism, yet allow for sufficient plasticity so as to integrate changing external and internal cues.

While the catalytic and structural function of nuclear proteins has been the center of research for several decades, relatively recent studies provide increasing evidence that long non-coding (lnc)RNAs may assume roles in mediating processes typically known to be exerted by protein complexes, ranging from the fine-tuning of developmental programs to key regulatory aspects of cellular function. LncRNAs are arbitrarily defined as RNA molecules of greater than 200 nucleotides in length that do not contain any apparent protein-coding potential, as determined largely by bioinformatic means. These comprise both unspliced or multi-exonic transcripts that may or may not be poly-adenylated. The majority of lncRNAs are expressed at low levels, largely precluding their discovery prior to the advent of RNA deep sequencing approaches. Furthermore, their low expression level has fueled concerns about how and to which extent some of these molecules are biologically functional (discussed in [5]). Broadly, lncRNAs can be classified into small RNA hosts or precursor transcripts, enhancer-associated RNAs (eRNAs), transcripts overlapping annotated genes in sense or anti-sense direction (including intronic lncRNAs), as well as lncRNAs that are self-contained transcription units falling in between known protein-coding genes and also referred to as long “intergenic” non-coding (linc)RNAs [6–9]. This coarse classification is dwarfed by the range of biological processes lncRNAs have been implicated in [10,11]. Furthermore, the latter likely only represents the tip of the iceberg given the minute fraction of lncRNAs functionally characterized to date.

In several cases, in particular those where the lncRNA is implicated in transcriptional regulation or the modulation of chromatin state in cis, it is frequently difficult to assess if the effect of a given lncRNA is mediated by the mature RNA molecule itself, or by the local activity of RNA polymerases and their associated proteins, as reviewed in Kornienko et al. [12]. Here, we will highlight recent studies supporting a direct involvement of individual lncRNA molecules as the functional entity in the regulation of transcriptional activity and chromatin state, as well as the architectural role of lncRNAs within nuclear bodies.

A case for RNA

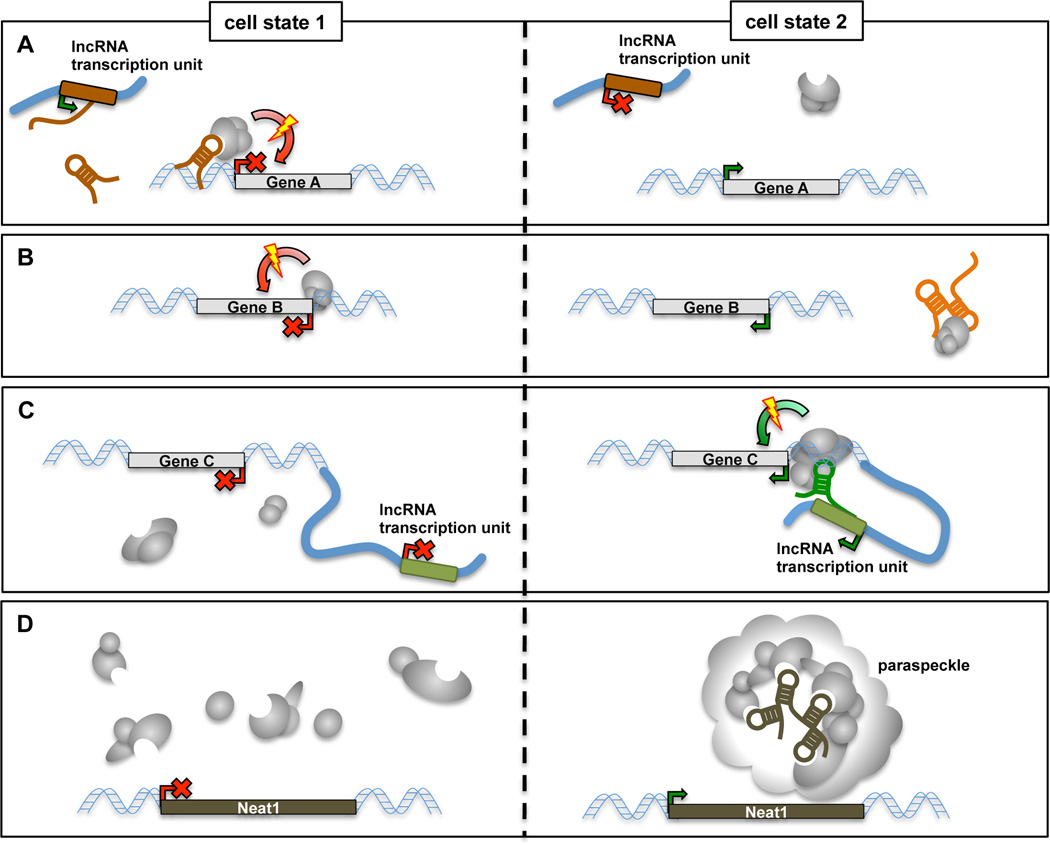

The majority of the thousands of lncRNAs identified to date are transcribed in a highly cell- and tissue-specific manner [8,13,14]. These molecules thus provide an exciting prospect of forming molecular layers contributing towards the vast range of functional diversity found across different cell types. As discussed below, the currently promoted hypotheses of lncRNA function largely revolve around interaction of lncRNAs with specific proteins, so as to modulate their dynamics and localization, or the compositional structure of multi-protein complexes (Figure 1) [10,15,16]. In fact, it has been known for decades that ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes incorporating non-coding RNAs, such as ribosomes and some RNA processing components including snRNPs and snoRNPs, actively participate in cellular function. Their biochemical features render lncRNAs tantalizing molecules as potential key elements regulating cellular function.

Figure 1. Recent insight into the molecular functions of nuclear lncRNAs.

Cell-state specific expression of individual lncRNAs can modulate the targeting of interacting proteins, their activity, or the structural composition of multi-protein complexes. A) Transcriptional regulation can occur in trans through the targeting of silencing (or activating, not pictured) chromatin-modifying complexes. Examples discussed in the main text include HOTAIR, Fendrr and Braveheart. B) LncRNAs can act as “decoys”, sequestering transcription repressors away from their cognate target gene promoters. Examples include Gas5, PANDA and Lethe. C) Transcriptional modulation of neighboring genes in cis involves lncRNA-mediated recruitment of chromatin factors (ANRIL and Mistral) and may involve lncRNA-dependent intra-chromosomal contact to gene promoters (HOTTIP and several lncRNAs with enhancer-like function [30,64]). D) Neat1 lncRNA serves to assemble and maintain paraspeckle nuclear bodies.

Both primary transcript sequence as well as secondary structure motifs allow an RNA to selectively interact with proteins [17–20]. In mammalian cells, in excess of 800 proteins associate with the poly-adenylated transcript fraction alone, creating a diverse multi-dimensional RNP network [21,22]. Besides facilitating the proximity of individual RNA-binding proteins with each other, alternative splicing of lncRNAs resulting in the inclusion or exclusion of individual structural elements can further modulate the composition and thus potentially regulate the functional output of an RNP [23].

The primary sequence of lncRNAs may not only determine RNP composition, but also hold the clue towards localization of the associated proteins, which frequently lack apparent DNA binding motifs, to their target sites in the genome. Recent data has shown that certain lncRNAs in mammalian as well as Drosophila cells occupy hundreds of genomic sites, and that these sites contain sequence motifs specific for the given lncRNA [24,25]. RNA can form triple-helices with DNA, and several lines of evidence indicate that these structures can be functional in vivo (reviewed in [26]). Indeed, lncRNA:DNA:DNA triplexes were shown to mediate local targeting of the DNA methyltransferase DNMT3b to or displacement of TFIIB from rRNA genes and the DHFR promoter, respectively [27,28].

Lastly, the comparatively rapid process of transcriptional induction is well suited to accommodate and relay time-sensitive alterations of intrinsic or extrinsic cues through lncRNAs. In support of this, estrogen signaling in MCF-7 cells was recently shown to result in the rapid change in expression of a large number of lncRNAs [29–31], suggesting they may perform an early functional role in this pathway. Indeed, knockdown of a subset of enhancer-associated lncRNAs in this system resulted in an impaired induction of the adjacent protein-coding genes [30]. With a wide range of transcript half lives that are globally lower than those of proteins [32–34], cellular effectiveness of lncRNA function can consequently be tightly regulated. This temporal control of cellular lncRNA levels could thus result in an equally tight control of lncRNP functional output, as illustrated above.

Dynamic regulation of transcription and chromatin state by lncRNAs

Perhaps the most dramatic case of transcriptional regulation mediated by a lncRNA known to date occurs during dosage compensation through the inactivation of one of the two female X-chromosomes (Xi) during mammalian differentiation. In this process, nearly all genes on the Xi become permanently repressed. Xist is specifically transcribed from and coats the Xi in somatic cells [35]. Xist was recently shown to directly interact with Ezh2, the catalytic subunit of the Polycomb repressive complex (PRC)2, through the Repeat A motif on Xist, resulting in recruitment of PRC2 to the chromosome [36]. Initial targeting of PRC2 through Xist occurs at a “nucleation center”, by tethering of Xist through the YY1 protein, which binds to the Repeat C motif on Xist [37]. PRC2 subsequently spreads across and silences genes along the Xi through catalyzing the repressive trimethylation of lysine 27 on histone H3 (H3K27) [38]. A recent study proposed that during this process, Xist alters the three-dimensional architecture of Xi to facilitate repositioning of active genes into the repressive compartment [39]. Remarkably, an inducible Xist cDNA construct inserted on one copy of human chromosome 21 in tri-somic Down syndrome stem cells results in the coating of the chromosome by XIST RNA associated with chromosome-wide gene repression and chromatin modification [40]. Regulation of endogenous Xist expression and its impact on the X-chromosome is complex and controlled by additional lncRNAs including long interspersed elements, as well as their protein interactors [41–43] (for comprehensive review, see Augui et al. [44]). Of note, a recent study identified another lncRNA, XACT, which is expressed in human cells and at least partially associates with the active X-chromosome as determined by RNA-DNA in situ hybridization, although the functional role of this RNA has yet to be elucidated [45].

Over the past several years, other lncRNAs have been identified that can modulate chromatin state and transcriptional activity in cis (affecting neighboring genes) or in trans (affecting distant genes on different chromosomes). Indeed, many lncRNAs are enriched in the nucleus and interact with a range of chromatin-modifying complexes [46–49]. Among the first lncRNAs implicated in the modulation of chromatin state in trans (Figure 1A), and perhaps the most thoroughly studied representative of this class of lncRNAs, is HOTAIR [50]. HOTAIR is transcribed within the human HOXC locus on chromosome 12, and interacts with the catalytic subunit of PRC2, Ezh2 [47,50–52]. Depletion of HOTAIR transcripts by siRNA does not have an impact on transcription of genes within its host locus HOXC, but was instead found to cause a reduction of PRC2 occupancy, local decrease in H3K27 trimethylation, and the activation of genes within the HOXD locus on chromosome 2 [50]. Subsequent genome-wide analysis identified hundreds of sites on different chromosomes that are associated with HOTAIR [25]. Binding of HOTAIR was independent of the presence of Ezh2, indicating that HOTAIR may act upstream in PRC2 recruitment. In concordance, forced over-expression of HOTAIR is sufficient to cause ectopic mis-localization of PRC2 to several genomic regions [53]. While the 5’ end of HOTAIR is required for interaction with PRC2, its 3’ end was shown to interact with the H3K4-demethylase LSD1 in vitro [51]. This interaction results in the physical bridging of a small sub-fraction of PRC2 and LSD1-containing repressive complexes, with HOTAIR knock-down causing loss of either or both complexes at a subset of target genes [51]. Interestingly, knocking out mouse Hotair does not impact Hoxd gene expression or chromatin state [54], suggesting functional differences between mouse and human HOTAIR activity.

Similar to HOTAIR, two other lncRNAs have recently been implicated in regulating developmental gene expression programs through the interaction of chromatin modifiers and the modulation of local chromatin state in trans. The lncRNA Fendrr is required for heart and body wall development in the mouse, and its homozygous disruption causes embryonic lethality [55]. Pull-downs using antibodies against either PRC2 components or WDR5, a member of the MLL histone methyl-transferase complex, retrieved Fendrr RNA, and loss of Fendrr correlated with reduced occupancy of PRC2 at the promoters of Foxf1, Pitx2 and Irx3, paralleled by an up-regulation of these genes. Notably, RNA oligomers corresponding to Fendrr were able to bind Pitx2 and Foxf1 promoter DNA fragments in vitro, together suggesting that Fendrr might facilitate targeting of PRC2 to these sites through triple helix interaction in vivo.

Analogously, Braveheart is a lncRNA most prominently expressed in the mouse heart, and shRNA-mediated depletion of Braveheart in different stem- and progenitor cell culture systems indicates Braveheart expression to be required for the commitment of cells to the cardiac lineage [56]. Reduction of Braveheart levels correlated with an altered occupancy of PRC2 at cardiac gene promoters, and pull-down experiments in vitro and in vivo indicate that Braveheart can interact with the PRC2 subunit Suz12. However, it remains to be determined if Braveheart directly mediates the functional targeting of PRC2 to these promoters.

A different mechanism for a lncRNA to mediate transcriptional output in trans is exemplified by Gas5 (Figure 1B). Gas5 accumulates in growth-arrested cells and was shown to bind to the glucocorticoid receptor (GR), preventing it from binding to glucocorticoid response elements and impairing GR-mediated transcriptional induction [57]. Similarly, the p53-induced lncRNA PANDA has been reported to interact with the nuclear transcription factor NF-YA both in vitro and in RNA immuno-precipitation assays [58]. PANDA knock-down upregulated pro-apoptotic NF-YA target genes, paralleled by an increase of NF-YA occupancy at target promoters, combined suggesting that this lncRNA acts as a decoy to sequester or displace NF-YA from its genomic binding sites. Recently, another lncRNA has been suggested to act as transcription factor decoy: In mouse embryonic fibroblasts, Lethe regulates NFκB activity by binding to its subunit RelA and preventing its association with DNA [59].

Akin to the modulation of chromatin state at distant sites, several lncRNAs are implicated in regulating chromatin function in their genomic vicinity. Notable cis effects are exerted by lncRNAs such as ANRIL, an antisense transcript overlapping the INK4b/ARF/INK4a locus. ANRIL was found to bind both, PRC1 and PRC2 complexes and to be required for the repression of gene transcription at this locus [60,61]. Conversely, other lncRNAs were shown to recruit transcriptional activators to facilitate local target gene transcription. In mouse, Mistral was found to recruit the histone methyl-transferase MLL1 via a short stem loop, facilitating conformational association and inducing expression of the neighboring Hoxa6 and Hoxa7 genes during embryonic stem cell differentiation [62]. Similarly, the lncRNA HOTTIP was suggested to promote transcription of genes within the HOXA locus in human fibroblasts through chromosomal looping and an interaction with WDR5/MLL complexes (Figure 1C) [63].

Chromosomal looping between loci of lncRNAs originally found to comprise enhancer-like activity and their target gene promoters has also been observed. This contact, as well as modulation of target gene transcription, was abrogated when cells were treated with siRNA against the lncRNA, while the interaction between these loci was further dependent on the Mediator complex [64,65]. Analogously, estrogen signaling-induced looping between a subset of enhancer-associated lncRNA loci and their target promoters in MCF-7 cells was reduced upon knock-down of the lncRNA, paralleled by a reduced recruitment of the cohesin complex to the enhancer and diminished target gene expression [30].

LncRNAs at the core of nuclear bodies

The nucleus harbors a range of sub-structures, collectively referred to as “nuclear bodies”. Although the biological function of many of these structures remains to be elucidated, it is apparent that they are complex associations comprising many distinct proteins that in part interchange at these bodies in a highly dynamic manner [66].

Several independent studies have demonstrated that the abundant lncRNA Neat1 (also called Men ε/β) is essential for the maintenance of a nuclear sub-structure termed the paraspeckle (Figure 1D) [67–69]. Time-lapse imaging studies in cells harboring an inducible Neat1 construct further demonstrate that expression of Neat1 is sufficient for the co-transcriptional assembly of paraspeckles at the ectopic Neat1 locus [70]. Likewise, tethering of Neat1 RNA to a genomic region comprising a reporter array is sufficient for the local nucleation of a paraspeckle [71]. Consistent with the integral role of Neat1 RNA for paraspeckle formation, human embryonic stem cells, which do not express NEAT1, do not form paraspeckles [68]. As these cells differentiate, NEAT1 expression is induced, and paralleled by the formation of paraspeckles. Similarly, upon mouse myotube differentiation, Neat1 transcription is up-regulated resulting in an increase in the number and size of paraspeckles [69]. These examples provide a striking case of how regulation of lncRNA expression can be linked to the modulation of a specific nuclear body.

Other lncRNAs are known to display distinct nuclear localization patterns. Most prominently, Malat1 (also called Neat2) is associated with nuclear speckles [67,72], although as discussed below, the transcript is non-essential for speckle formation and integrity. Also notable with respect to nuclear sub-structures is the lncRNA Gomafu (alternatively called Miat or RNCR2), which is mostly expressed in the mouse nervous system [73,74]. Gomafu is non-uniformly distributed in the nucleus of neuronal cells and associates with the insoluble nuclear matrix fraction, but does not co-localize with markers for known nuclear sub-structures [73]. Knock-down of Gomafu in post-natal retina cells indicates a role for the transcript in cellular specification [75], although the underlying molecular mechanism remains to be determined. Recent studies found that Gomafu is bound by different splicing factors [76,77], and suggest that this interaction has an impact on alternative splicing in neurons [76].

Malat1: enigma or multi-tasking?

Malat1 was originally identified amongst several genes upregulated in metastatic non-small cell lung cancer [78]. A host of recent studies identified mis-expression and mutations of Malat1 in several other cancers, rendering Malat1 a tumor marker with potential as a prognostic or therapeutic target (reviewed by Gutschner et al. [79]). Through sequential RNAse P and RNAse Z mediated processing, the 3’ end of Malat1 yields a 61 nucleotide tRNA-like small RNA termed mascRNA, which is exported into the cytoplasm [80], while the ~6,700 nucleotide Malat1 transcript is retained in the nucleus where it is concentrated in nuclear speckles but also diffusely present throughout the nucleoplasm [67,72,80].

Within the poly-adenylated fraction, Malat1 represents the most abundant lncRNA [81]. Furthermore, in contrast to most other lncRNAs, Malat1, and in particular its 3’ mascRNA module, is highly conserved in vertebrates [72,82]. Expression level, evolutionary conservation and its mis-regulation in various cancers suggest that Malat1 is involved in important cellular processes and has consequently been a major focus of research. While the function of mascRNA has yet to been elucidated, several studies have aimed to assess the cellular role of Malat1. As mentioned above, despite its prominent localization to nuclear speckles, Malat1 is not required for speckle formation or maintenance [72,81,83,84]. However, transient knock-down of Malat1 in different cell types was reported to cause a series of phenotypic changes, including impaired cell cycle progression [83,85,86], apoptosis [83], reduced cell motility [87,88] and diminished synapse formation in cultured neurons [89]. On the molecular level, Malat1 knock-down resulted in altered splicing patterns [83,85] or changes in gene expression [85–89]. Its impact on splicing may be associated with the reported interaction of Malat1 with different SR-type splicing factors, which appears to modulate their nuclear distribution [83,89] and, at least in certain cell types, their phosphorylation state [83]. The regulation of gene expression through Malat1 was recently suggested to be mediated in part through p53 pathway activation, although the molecular mode of this effect has not yet been determined [85]. Another study found MALAT1 to bind to unmethylated Polycomb 2 (Pc2) protein, and in in vitro pull-down conditions to other transcriptional co-activators [86]. Here, MALAT1 was furthermore essential for the re-location of growth control genes from Polycomb bodies to nuclear speckles, paralleled by their activation in HeLa cells.

In light of the above studies, perhaps the biggest surprise came from three recent Malat1 knock-out studies, which collectively failed to identify marked Malat1 phenotypes, including any of the defects observed in previous knock-down studies [81,84,90]. Two of these reports noted a mild impact of Malat1 knock out on the expression of the neighboring lncRNA Neat1 (see above). Furthermore, while in one knock-out system Neat1 is down-regulated in intestine, colon and embryonic fibroblasts [84], the other system displays a mild up-regulation of Neat1 expression in brain and liver [81]. The lack of a strong phenotype in Malat1−/− mice may well be attributed to functional compensation during development. Alternatively, and in line with the diverse defects seen in different cell lines in Malat1 knock-down studies, Malat1 might act as a more subtle sentinel of cellular state, mediating relevant responses under specific stress conditions such as malignant transformation. Clearly, despite the intensive research efforts to date, many open questions remain to be addressed and additional work is needed to investigate the function of Malat1 in different physiological backgrounds.

Future directions

The field of “modern” lncRNA research is comparatively young, but from the few examples studied to date, it is clear that lncRNAs have revealed exciting new layers in the control of cellular function and metabolism. In addition, lncRNAs already are of great interest as disease biomarkers or potential targets for novel therapeutic approaches (discussed in [91,92]). However, the comparatively short time since discovering the thousands of lncRNAs also reflects the major challenges ahead in studying these molecules:

We currently lack the necessary information to predict the function of a given lncRNA based on their sequence alone. In fact, we cannot even exclude the possibility that any one of the presently uncharacterized lncRNAs may be coding for a small protein or peptide, rather than acting as a non-coding entity. This is exemplified by “polished rice”, a Drosophila transcript originally thought to be non-coding, but subsequently shown to produce a short peptide [93]. In this respect, ribosome profiling studies in mouse embryonic stem cells found that the majority of lncRNAs are associated with ribosomes [94], although subsequent computational analyses suggest that these interactions may not result in productive protein biosynthesis [95].

Essentially, what is presently needed to propel this field forward is to investigate in depth, on a one-by-one basis, uncharacterized lncRNAs so as to probe their functional roles. Molecular and biochemical assays should be complemented with studying lncRNA localization and expression on the subcellular level, ideally employing RNA fluorescence in situ hybridization protocols with single molecule sensitivity. Besides assessing their enrichment in the nucleus, these data will furthermore allow to determine cell to cell variability as well as cell cycle-specific patterns of lncRNA expression and localization. These efforts need to be paralleled by the development of advanced molecular tools to study RNAs, their structure, and their functional interactions. Indeed, several recent efforts have generated valuable approaches both for a more global analysis as well as for specific sub-classes of lncRNAs. Of particular note are methods aiming to determine the folding of lncRNA molecules [96–98] and the functional principles of these structures [17]. Other important approaches aim to identify the in vivo complement of cellular RNA interactors comprising both proteins [21,22] and other RNA molecules [99], and the mapping of binding sites of individual RNA-binding proteins at nucleotide resolution [20]. Of interest with respect to lncRNAs implicated in targeting effector proteins to genomic sites is a series of analogous procedures providing genome-wide data sets of RNP occupancy, termed CHART (Capture Hybridization Analysis of RNA Targets) [24], ChIRP (Chromatin Isolation by RNA Purification) [25] or RAP (RNA Antisense Purification) [39]. Keeping in mind the impact of these lncRNAs on local chromatin state, it will furthermore be of great interest to apply established chromosome conformation capture technologies (recently reviewed in [100]) to lncRNA loss- or gain-of-function systems, so as to investigate the impact of these molecules on global genome structure and chromatin organization.

Combined, these data should allow for the assembly of a database analogous to for example Pfam [101], containing lncRNA sequence features such as binding sites for specific effector proteins, functional secondary structure elements or “zip codes” directing the targeting to distinct cellular domains or genomic sites, that will aid in more rapid movement towards functional characterization as well as high-throughput analyses of newly identified lncRNAs.

Acknowledgements

We thank Gayatri Arun in the Spector lab for critical reading and discussion of the manuscript. JHB is supported by a DAAD postdoctoral fellowship. D.L.S. is funded by NCI 5P01CA013106, NCI 2P30CA45508 and NIGMS 42694.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

References of special interest

We consider these references of special [••] interest:

- 1.Alabert C, Groth A. Chromatin replication and epigenome maintenance. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:153–167. doi: 10.1038/nrm3288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grünwald D, Singer RH, Rout M. Nuclear export dynamics of RNAprotein complexes. Nature. 2011;475:333–341. doi: 10.1038/nature10318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spitz F, Furlong EEM. Transcription factors: from enhancer binding to developmental control. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13:613–626. doi: 10.1038/nrg3207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kornblihtt AR, Schor IE, Alló M, Dujardin G, Petrillo E, Muñoz MJ. Alternative splicing: a pivotal step between eukaryotic transcription and translation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2013;14:153–165. doi: 10.1038/nrm3525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ponting CP, Oliver PL, Reik W. Evolution and Functions of Long Noncoding RNAs. Cell. 2009;136:629–641. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim T-K, Hemberg M, Gray JM, Costa AM, Bear DM, Wu J, Harmin DA, Laptewicz M, Barbara-Haley K, Kuersten S, et al. Widespread transcription at neuronal activity-regulated enhancers. Nature. 2010;465:182–187. doi: 10.1038/nature09033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guttman M, Amit I, Garber M, French C, Lin MF, Feldser D, Huarte M, Zuk O, Carey BW, Cassady JP, et al. Chromatin signature reveals over a thousand highly conserved large non-coding RNAs in mammals. Nature. 2009;458:223–227. doi: 10.1038/nature07672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Djebali S, Davis CA, Merkel A, Dobin A, Lassmann T, Mortazavi A, Tanzer A, Lagarde J, Lin W, Schlesinger F, et al. Landscape of transcription in human cells. Nature. 2012;489:101–108. doi: 10.1038/nature11233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.ENCODE Project Consortium. Dunham I, Kundaje A, Aldred SF, Collins PJ, Davis CA, Doyle F, Epstein CB, Frietze S, Harrow J, et al. An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature. 2012;489:57–74. doi: 10.1038/nature11247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rinn JL, Chang HY. Genome Regulation by Long Noncoding RNAs. Annual review of biochemistry. 2012;81:145–166. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-051410-092902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilusz JE, Sunwoo H, Spector DL. Long noncoding RNAs: functional surprises from the RNA world. Genes & Development. 2009;23:1494–1504. doi: 10.1101/gad.1800909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kornienko AE, Guenzl PM, Barlow DP, Pauler FM. Gene regulation by the act of long non-coding RNA transcription. BMC Biology. 2013;11:1–14. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-11-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hangauer MJ, Vaughn IW, McManus MT. Pervasive Transcription of the Human Genome Produces Thousands of Previously Unidentified Long Intergenic Noncoding RNAs. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003569. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cabili MN, Trapnell C, Goff L, Koziol M, Tazon-Vega B, Regev A, Rinn JL. Integrative annotation of human large intergenic noncoding RNAs reveals global properties and specific subclasses. Genes & Development. 2011;25:1915–1927. doi: 10.1101/gad.17446611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Batista PJ, Chang HY. Long Noncoding RNAs: Cellular Address Codes in Development and Disease. Cell. 2013;152:1298–1307. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee JT. Epigenetic Regulation by Long Noncoding RNAs. Science. 2012;338:1435–1439. doi: 10.1126/science.1231776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martin L, Meier M, Lyons SM, Sit RV, Marzluff WF, Quake SR, Chang HY. Systematic reconstruction of RNA functional motifs with high-throughput microfluidics. Nat Meth. 2012;9:1192–1194. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hogan DJ, Riordan DP, Gerber AP, Herschlag D, Brown PO. Diverse RNA-Binding Proteins Interact with Functionally Related Sets of RNAs, Suggesting an Extensive Regulatory System. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e255. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ray D, Kazan H, Chan ET, Castillo LP, Chaudhry S, Talukder S, Blencowe BJ, Morris Q, Hughes TR. Rapid and systematic analysis of the RNA recognition specificities of RNA-binding proteins. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27:667–670. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hafner M, Landthaler M, Burger L, Khorshid M, Hausser J, Berninger P, Rothballer A, Ascano M, Jungkamp A-C, Munschauer M, et al. Transcriptome-wide identification of RNA-binding protein and microRNA target sites by PAR-CLIP. Cell. 2010;141:129–141. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baltz AG, Munschauer M, Schwanhäusser B, Vasile A, Murakawa Y, Schueler M, Youngs N, Penfold-Brown D, Drew K, Milek M, et al. The mRNA-Bound Proteome and Its Global Occupancy Profile on Protein-Coding Transcripts. Molecular Cell. 2012;46:674–690. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Castello A, Fischer B, Eichelbaum K, Horos R, Beckmann BM, Strein C, Davey NE, Humphreys DT, Preiss T, Steinmetz LM, et al. Insights into RNA biology from an atlas of mammalian mRNA-binding proteins. Cell. 2012;149:1393–1406. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maamar H, Cabili MN, Rinn J, Raj A. linc-HOXA1 is a noncoding RNA that represses Hoxa1 transcription in cis. Genes & Development. 2013;27:1260–1271. doi: 10.1101/gad.217018.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simon MD, Wang CI, Kharchenko PV, West JA, Chapman BA, Alekseyenko AA, Borowsky ML, Kuroda MI, Kingston RE. The genomic binding sites of a noncoding RNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:20497–20502. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1113536108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chu C, Qu K, Zhong FL, Artandi SE, Chang HY. Genomic maps of long noncoding RNA occupancy reveal principles of RNA-chromatin interactions. Molecular Cell. 2011;44:667–678. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.08.027. A novel technique to probe the genome-wide binding of chromatin-associated lncRNAs, ChIRP-Seq, reveals DNA sequence motifs for HOTAIR binding at target promoters, suggesting that lncRNAs can function in a manner analogous to transcription factors.

- 26.Buske FA, Mattick JS, Bailey TL. Potential in vivo roles of nucleic acid triple-helices. RNA Biol. 2011;8:427–439. doi: 10.4161/rna.8.3.14999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schmitz K-M, Mayer C, Postepska A, Grummt I. Interaction of noncoding RNA with the rDNA promoter mediates recruitment of DNMT3b and silencing of rRNA genes. Genes & Development. 2010;24:2264–2269. doi: 10.1101/gad.590910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martianov I, Ramadass A, Serra Barros A, Chow N, Akoulitchev A. Repression of the human dihydrofolate reductase gene by a noncoding interfering transcript. Nature. 2007;445:666–670. doi: 10.1038/nature05519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hah N, Murakami S, Nagari A, Danko CG, Kraus WL. Enhancer transcripts mark active estrogen receptor binding sites. Genome Research. 2013 doi: 10.1101/gr.152306.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Li W, Notani D, Ma Q, Tanasa B, Nunez E, Chen AY, Merkurjev D, Zhang J, Ohgi K, Song X, et al. Functional roles of enhancer RNAs for oestrogen-dependent transcriptional activation. Nature. 2013;498:516–520. doi: 10.1038/nature12210. A large set of enhancer-lncRNAs are identified that mediate the transcriptional output of estrogen signalling in MCF7 cells. A subset of these lncRNAs is shown to mediate the chromosomal looping between enhancer and target promoter concomitant with local stabilization of the association of the cohesin complex.

- 31. Hah N, Danko CG, Core L, Waterfall JJ, Siepel A, Lis JT, Kraus WL. A Rapid, Extensive, and Transient Transcriptional Response to Estrogen Signaling in Breast Cancer Cells. Cell. 2011;145:622–634. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.03.042. Global run-on sequencing in MCF-7 cells shows a rapid and wide-spread transcriptional induction within 10 minutes of estradiol treatment. LncRNAs represent a large fraction of these transcripts.

- 32.Schwanhäusser B, Busse D, Li N, Dittmar G, Schuchhardt J, Wolf J, Chen W, Selbach M. Global quantification of mammalian gene expression control. Nature. 2011;473:337–342. doi: 10.1038/nature10098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Clark MB, Johnston RL, Inostroza-Ponta M, Fox AH, Fortini E, Moscato P, Dinger ME, Mattick JS. Genome-wide analysis of long noncoding RNA stability. Genome Research. 2012;22:885–898. doi: 10.1101/gr.131037.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tani H, Mizutani R, Salam KA, Tano K, Ijiri K, Wakamatsu A, Isogai T, Suzuki Y, Akimitsu N. Genome-wide determination of RNA stability reveals hundreds of short-lived noncoding transcripts in mammals. Genome Research. 2012 doi: 10.1101/gr.130559.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Clemson CM, McNeil JA, Willard HF, Lawrence JB. XIST RNA paints the inactive X chromosome at interphase: evidence for a novel RNA involved in nuclear/chromosome structure. The Journal of Cell Biology. 1996;132:259–275. doi: 10.1083/jcb.132.3.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhao J, Sun BK, Erwin JA, Song J-J, Lee JT. Polycomb Proteins Targeted by a Short Repeat RNA to the Mouse X Chromosome. Science. 2008;322:750–756. doi: 10.1126/science.1163045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Jeon Y, Lee JT. YY1 tethers Xist RNA to the inactive X nucleation center. Cell. 2011;146:119–133. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.026. YY1 protein bridges XIST RNA and the X-chromosome and facilitates the loading of XIST onto the Xi.

- 38.Pinter SF, Sadreyev RI, Yildirim E, Jeon Y, Ohsumi TK, Borowsky M, Lee JT. Spreading of X chromosome inactivation via a hierarchy of defined Polycomb stations. Genome Research. 2012;22:1864–1876. doi: 10.1101/gr.133751.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Engreitz JM, Pandya-Jones A, McDonel P, Shishkin A, Sirokman K, Surka C, Kadri S, Xing J, Goren A, Lander ES, et al. The Xist lncRNA Exploits Three-Dimensional Genome Architecture to Spread Across the X Chromosome. Science. 2013 doi: 10.1126/science.1237973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Jiang J, Jing Y, Cost GJ, Chiang J-C, Kolpa HJ, Cotton AM, Carone DM, Carone BR, Shivak DA, Guschin DY, et al. Translating dosage compensation to trisomy 21. Nature. 2013 doi: 10.1038/nature12394. Induction of XIST cDNA ectopically inserted on chromosome 21 in tri-somic stem cells is sufficient to coat the chromosome with XIST, paralleled by chromosomewide gene repression and heterochromatinization.

- 41.Chow JC, Ciaudo C, Fazzari MJ, Mise N, Servant N, Glass JL, Attreed M, Avner P, Wutz A, Barillot E, et al. LINE-1 activity in facultative heterochromatin formation during X chromosome inactivation. Cell. 2010;141:956–969. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.04.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hasegawa Y, Brockdorff N, Kawano S, Tsutui K, Tsutui K, Nakagawa S. The Matrix Protein hnRNP U Is Required for Chromosomal Localization of Xist RNA. Developmental Cell. 2010;19:469–476. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sun S, Del Rosario BC, Szanto A, Ogawa Y, Jeon Y, Lee JT. Jpx RNA Activates Xist by Evicting CTCF. Cell. 2013;153:1537–1551. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Augui S, Nora EP, Heard E. Regulation of X-chromosome inactivation by the X-inactivation centre. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12:429–442. doi: 10.1038/nrg2987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vallot C, Huret C, Lesecque Y, Resch A, Oudrhiri N, Bennaceur-Griscelli A, Duret L, Rougeulle C. XACT, a long noncoding transcript coating the active X chromosome in human pluripotent cells. Nat Genet. 2013;45:239–241. doi: 10.1038/ng.2530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Guil S, Soler M, Portela A, Carrère J, Fonalleras E, Gómez A, Villanueva A, Esteller M. Intronic RNAs mediate EZH2 regulation of epigenetic targets. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2012;19:664–670. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhao J, Ohsumi TK, Kung JT, Ogawa Y, Grau DJ, Sarma K, Song JJ, Kingston RE, Borowsky M, Lee JT. Genome-wide Identification of Polycomb-Associated RNAs by RIP-seq. Molecular Cell. 2010;40:939–953. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Guttman M, Donaghey J, Carey BW, Garber M, Grenier JK, Munson G, Young G, Lucas AB, Ach R, Bruhn L, et al. lincRNAs act in the circuitry controlling pluripotency and differentiation. Nature. 2011;477:295–300. doi: 10.1038/nature10398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Khalil AM, Guttman M, Huarte M, Garber M, Raj A, Rivea Morales D, Thomas K, Presser A, Bernstein BE, van Oudenaarden A, et al. Many human large intergenic noncoding RNAs associate with chromatinmodifying complexes and affect gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:11667–11672. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904715106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rinn JL, Kertesz M, Wang JK, Squazzo SL, Xu X, Brugmann SA, Goodnough LH, Helms JA, Farnham PJ, Segal E, et al. Functional Demarcation of Active and Silent Chromatin Domains in Human HOX Loci by Noncoding RNAs. Cell. 2007;129:1311–1323. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Tsai M-C, Manor O, Wan Y, Mosammaparast N, Wang JK, Lan F, Shi Y, Segal E, Chang HY. Long noncoding RNA as modular scaffold of histone modification complexes. Science. 2010;329:689–693. doi: 10.1126/science.1192002. Evidence is presented to show that HOTAIR lncRNA acts as molecular scaffold to connect PRC2 and LSD1 complexes.

- 52.Kaneko S, Li G, Son J, Xu C-F, Margueron R, Neubert TA, Reinberg D. Phosphorylation of the PRC2 component Ezh2 is cell cycleregulated and up-regulates its binding to ncRNA. Genes & Development. 2010;24:2615–2620. doi: 10.1101/gad.1983810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Gupta RA, Shah N, Wang KC, Kim J, Horlings HM, Wong DJ, Tsai M-C, Hung T, Argani P, Rinn JL, et al. Long non-coding RNA HOTAIR reprograms chromatin state to promote cancer metastasis. Nature. 2010;464:1071–1076. doi: 10.1038/nature08975. Over-expression of HOTAIR is sufficient for the genomic mis-localization of PRC2 and can confer increased invasiveness of breast carcinoma cells.

- 54.Schorderet P, Duboule D. Structural and functional differences in the long non-coding RNA hotair in mouse and human. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002071. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Grote P, Wittler L, Hendrix D, Koch F, Währisch S, Beisaw A, Macura K, Bläss G, Kellis M, Werber M, et al. The Tissue-Specific lncRNA Fendrr Is an Essential Regulator of Heart and Body Wall Development in the Mouse. Developmental Cell. 2013;24:206–214. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Klattenhoff CA, Scheuermann JC, Surface LE, Bradley RK, Fields PA, Steinhauser ML, Ding H, Butty VL, Torrey L, Haas S, et al. Braveheart, a long noncoding RNA required for cardiovascular lineage commitment. Cell. 2013;152:570–583. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kino T, Hurt DE, Ichijo T, Nader N, Chrousos GP. Noncoding RNA gas5 is a growth arrest- and starvation-associated repressor of the glucocorticoid receptor. Sci Signal. 2010;3:ra8. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hung T, Wang Y, Lin MF, Koegel AK, Kotake Y, Grant GD, Horlings HM, Shah N, Umbricht C, Wang P, et al. Extensive and coordinated transcription of noncoding RNAs within cell-cycle promoters. Nat Genet. 2011;43:621–629. doi: 10.1038/ng.848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rapicavoli NA, Qu K, Zhang J, Mikhail M, Laberge RM, Chang HY. A mammalian pseudogene lncRNA at the interface of inflammation and anti-inflammatory therapeutics. eLife. 2013;2:e00762–e00762. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kotake Y, Nakagawa T, Kitagawa K, Suzuki S, Liu N, Kitagawa M, Xiong Y. Long non-coding RNA ANRIL is required for the PRC2 recruitment to and silencing of p15(INK4B) tumor suppressor gene. Oncogene. 2011;30:1956–1962. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yap KL, Li S, Muñoz-Cabello AM, Raguz S, Zeng L, Mujtaba S, Gil J, Walsh MJ, Zhou M-M. Molecular Interplay of the Noncoding RNA ANRIL and Methylated Histone H3 Lysine 27 by Polycomb CBX7 in Transcriptional Silencing of INK4a. Molecular Cell. 2010;38:662–674. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bertani S, Sauer S, Bolotin E, Sauer F. The noncoding RNA Mistral activates Hoxa6 and Hoxa7 expression and stem cell differentiation by recruiting MLL1 to chromatin. Molecular Cell. 2011;43:1040–1046. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 63.Wang KC, Yang YW, Liu B, Sanyal A, Corces-Zimmerman R, Chen Y, Lajoie BR, Protacio A, Flynn RA, Gupta RA, et al. A long noncoding RNA maintains active chromatin to coordinate homeotic gene expression. Nature. 2011;472:120–124. doi: 10.1038/nature09819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Lai F, Orom UA, Cesaroni M, Beringer M, Taatjes DJ, Blobel GA, Shiekhattar R. Activating RNAs associate with Mediator to enhance chromatin architecture and transcription. Nature. 2013;494:497–501. doi: 10.1038/nature11884. A representative lncRNA with enhancer-like function is shown to be essential for Mediator-dependent intra-chromosomal contact with its target gene promoter to facilitate fine-tuning of target gene expression.

- 65.Ørom UA, Derrien T, Beringer M, Gumireddy K, Gardini A, Bussotti G, Lai F, Zytnicki M, Notredame C, Huang Q, et al. Long Noncoding RNAs with Enhancer-like Function in Human Cells. Cell. 2010;143:46–58. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mao YS, Zhang B, Spector DL. Biogenesis and function of nuclear bodies. Trends Genet. 2011;27:295–306. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2011.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Clemson CM, Hutchinson JN, Sara SA, Ensminger AW, Fox AH, Chess A, Lawrence JB. An architectural role for a nuclear noncoding RNA: NEAT1 RNA is essential for the structure of paraspeckles. Molecular Cell. 2009;33:717–726. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chen L-L, Carmichael GG. Altered Nuclear Retention of mRNAs Containing Inverted Repeats in Human Embryonic Stem Cells: Functional Role of a Nuclear Noncoding RNA. Molecular Cell. 2009;35:467–478. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.06.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sunwoo H, Dinger ME, Wilusz JE, Amaral PP, Mattick JS, Spector DL. MEN epsilon/beta nuclear-retained non-coding RNAs are upregulated upon muscle differentiation and are essential components of paraspeckles. Genome Research. 2009;19:347–359. doi: 10.1101/gr.087775.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Mao YS, Sunwoo H, Bin Zhang, Spector DL. Direct visualization of the co-transcriptional assembly of a nuclear body by noncoding RNAs. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;13:95–101. doi: 10.1038/ncb2140. Live cell imaging demonstrates the spatio-temporal relationship between Neat1 and paraspeckle formation, showing that nascent Neat1 RNA acts as a seed for the assemply of this nuclear sub-structure.

- 71.Shevtsov SP, Dundr M. Nucleation of nuclear bodies by RNA. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:167–173. doi: 10.1038/ncb2157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hutchinson JN, Ensminger AW, Clemson CM, Lynch CR, Lawrence JB, Chess A. A screen for nuclear transcripts identifies two linked noncoding RNAs associated with SC35 splicing domains. BMC Genomics. 2007;8:39. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-8-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sone M, Hayashi T, Tarui H, Agata K, Takeichi M, Nakagawa S. The mRNA-like noncoding RNA Gomafu constitutes a novel nuclear domain in a subset of neurons. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:2498–2506. doi: 10.1242/jcs.009357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mercer TR, Dinger ME, Sunkin SM, Mehler MF, Mattick JS. Specific expression of long noncoding RNAs in the mouse brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:716–721. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706729105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rapicavoli NA, Poth EM, Blackshaw S. The long noncoding RNA RNCR2 directs mouse retinal cell specification. BMC Dev Biol. 2010;10:49. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-10-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Barry G, Briggs JA, Vanichkina DP, Poth EM, Beveridge NJ, Ratnu VS, Nayler SP, Nones K, Hu J, Bredy TW, et al. The long non-coding RNA Gomafu is acutely regulated in response to neuronal activation and involved in schizophrenia-associated alternative splicing. Mol. Psychiatry. 2013 doi: 10.1038/mp.2013.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tsuiji H, Yoshimoto R, Hasegawa Y, Furuno M, Yoshida M, Nakagawa S. Competition between a noncoding exon and introns: Gomafu contains tandem UACUAAC repeats and associates with splicing factor-1. Genes Cells. 2011;16:479–490. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2011.01502.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ji P, Diederichs S, Wang W, Böing S, Metzger R, Schneider PM, Tidow N, Brandt B, Buerger H, Bulk E, et al. MALAT-1, a novel noncoding RNA, thymosin beta4 predict metastasis and survival in early stage non-small cell lung cancer. Oncogene. 2003;22:8031–8041. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gutschner T, Hämmerle M, Diederichs S. MALAT1 - a paradigm for long noncoding RNA function in cancer. J. Mol. Med. 2013;91:791–801. doi: 10.1007/s00109-013-1028-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wilusz JE, Freier SM, Spector DL. 3' end processing of a long nuclearretained noncoding RNA yields a tRNA-like cytoplasmic RNA. Cell. 2008;135:919–932. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zhang B, Arun G, Mao YS, Lazar Z, Hung G, Bhattacharjee G, Xiao X, Booth CJ, Wu J, Zhang C, et al. The lncRNA Malat1 is dispensable for mouse development but its transcription plays a cis-regulatory role in the adult. CellReports. 2012;2:111–123. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Ulitsky I, Shkumatava A, Jan CH, Sive H, Bartel DP. Conserved Function of lincRNAs in Vertebrate Embryonic Development despite Rapid Sequence Evolution. Cell. 2011;147:1537–1550. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.11.055. This study demonstrates that the mammalian orthologue of the lncRNA Cyrano can rescue zebrafish development in Cyrano-depleted embryos.

- 83.Tripathi V, Ellis JD, Shen Z, Song DY, Pan Q, Watt AT, Freier SM, Bennett CF, Sharma A, Bubulya PA, et al. The nuclear-retained noncoding RNA MALAT1 regulates alternative splicing by modulating SR splicing factor phosphorylation. Molecular Cell. 2010;39:925–938. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Nakagawa S, Ip JY, Shioi G, Tripathi V, Zong X, Hirose T, Prasanth KV. Malat1 is not an essential component of nuclear speckles in mice. RNA. 2012;18:1487–1499. doi: 10.1261/rna.033217.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Tripathi V, Shen Z, Chakraborty A, Giri S, Freier SM, Wu X, Zhang Y, Gorospe M, Prasanth SG, Lal A, et al. Long noncoding RNA MALAT1 controls cell cycle progression by regulating the expression of oncogenic transcription factor B-MYB. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003368. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Yang L, Lin C, Liu W, Zhang J, Ohgi KA, Grinstein JD, Dorrestein PC, Rosenfeld MG. ncRNA- and Pc2 Methylation-Dependent Gene Relocation between Nuclear Structures Mediates Gene Activation Programs. Cell. 2011;147:773–788. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.08.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Tano K, Mizuno R, Okada T, Rakwal R, Shibato J, Masuo Y, Ijiri K, Akimitsu N. MALAT-1 enhances cell motility of lung adenocarcinoma cells by influencing the expression of motility-related genes. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:4575–4580. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Gutschner T, Hämmerle M, Eißmann M, Hsu J, Kim Y, Hung G, Revenko A, Arun G, Stentrup M, Groß M, et al. The noncoding RNA MALAT1 is a critical regulator of the metastasis phenotype of lung cancer cells. Cancer Research. 2013;73:1180–1189. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bernard D, Prasanth KV, Tripathi V, Colasse S, Nakamura T, Xuan Z, Zhang MQ, Sedel F, Jourdren L, Coulpier F, et al. A long nuclearretained non-coding RNA regulates synaptogenesis by modulating gene expression. The EMBO Journal. 2010;29:3082–3093. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Eißmann M, Gutschner T, Hämmerle M, Günther S, Caudron-Herger M, Groß M, Schirmacher P, Rippe K, Braun T, Zörnig M, et al. Loss of the abundant nuclear non-coding RNA MALAT1 is compatible with life and development. RNA Biol. 2012;9:1076–1087. doi: 10.4161/rna.21089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sánchez Y, Huarte M. Long non-coding RNAs: challenges for diagnosis and therapies. Nucleic Acid Ther. 2013;23:15–20. doi: 10.1089/nat.2012.0414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Qureshi IA, Mehler MF. Long Non-coding RNAs: Novel Targets for Nervous System Disease Diagnosis and Therapy. Neurotherapeutics. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s13311-013-0199-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kondo T, Plaza S, Zanet J, Benrabah E, Valenti P, Hashimoto Y, Kobayashi S, Payre F, Kageyama Y. Small peptides switch the transcriptional activity of Shavenbaby during Drosophila embryogenesis. Science. 2010;329:336–339. doi: 10.1126/science.1188158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ingolia NT, Lareau LF, Weissman JS. Ribosome Profiling of Mouse Embryonic Stem Cells Reveals the Complexity and Dynamics of Mammalian Proteomes. Cell. 2011;147:789–802. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Guttman M, Russell P, Ingolia NT, Weissman JS, Lander ES. Ribosome Profiling Provides Evidence that Large Noncoding RNAs Do Not Encode Proteins. Cell. 2013;154:240–251. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Watts JM, Dang KK, Gorelick RJ, Leonard CW, Bess JW, Swanstrom R, Burch CL, Weeks KM. Architecture and secondary structure of an entire HIV-1 RNA genome. Nature. 2009;460:711–716. doi: 10.1038/nature08237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Novikova IV, Hennelly SP, Sanbonmatsu KY. Structural architecture of the human long non-coding RNA, steroid receptor RNA activator. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:5034–5051. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Spitale RC, Crisalli P, Flynn RA, Torre EA, Kool ET, Chang HY. RNA SHAPE analysis in living cells. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2013;9:18–20. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Yoon J-H, Srikantan S, Gorospe M. MS2-TRAP (MS2-tagged RNA affinity purification): tagging RNA to identify associated miRNAs. Methods. 2012;58:81–87. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2012.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.de Wit E, de Laat W. A decade of 3C technologies: insights into nuclear organization. Genes & Development. 2012;26:11–24. doi: 10.1101/gad.179804.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Punta M, Coggill PC, Eberhardt RY, Mistry J, Tate J, Boursnell C, Pang N, Forslund K, Ceric G, Clements J, et al. The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D290–D301. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]