Abstract

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is a risk factor for chronic kidney disease and death. Despite progress made in understanding cellular and molecular basis of AKI pathogenesis there has been no improvement in the high mortality from this disease in decades. Epigenetics is one of the most intensively studied filed of biology today and represents a new paradigm for understanding the pathophysiology of disease. Although epigenetics of AKI is a nascent field the available information is already providing compelling evidence that chromatin biology plays a critical role in this disease. In this review article we explore what is known about contribution of epigenetic mechanisms to pathophysiology of AKI and how this knowledge is already guiding the development of new diagnostic tools and epigenetic therapies.

Keywords: epigenetics, acute kidney injury, chromatin, histone modification, DNA methylation

Introduction

Acute kidney injury (AKI), previously called acute renal failure (ARF), is manifested by an acute decline in renal function followed by structural changes [1]. AKI is associated with increased mortality, length of hospital stay and costs [2]. AKI mortality has been estimated to be in the 30%–70% range depending on severity of kidney damage. AKI puts patients at risk of chronic kidney disease and increases the likelihood of end-stage renal disease [3]. Despite progress made in understanding cellular and molecular basis of AKI pathogenesis there has been no improvement in the high mortality from this disease in decades [1,4]. It is estimated that each year there are 2 million people worldwide that die of AKI [5], approximately the same as from AIDS (World Health Organization data). Pathogenesis of any disease is not simple and AKI is no exception. Given the elaborate microanatomy of the kidney composed of nephrons intertwined with unique meshwork of microvessels, AKI affecting these structures is a complex disease. Different forms of insults cause injury to the vascular endothelial and/or tubular epithelial cells. As a result there is renal tubule necrosis and apoptosis with shedding of the cells and cellular debris into the tubule lumen causing intratubular obstruction and back-leak. Besides vascular and tubular cells, other cell types are also involved in pathogenesis of AKI including invading leukocytes, and dendritic resident cells. Inflammation is the major sequel of tissue injury characterized by release of cytokines/chemokines by renal tubular, vascular endothelial, resident dendritic cells and invading leukocytes. The list of these mediators is fairly well defined. The most commonly implicated pro-inflammatory mediators include cytokines (e.g. TNF-α, IL-6, IL-10), chemokines (e.g. MCP-1, RANTES), adhesion molecules (e.g. ICAM-1) and complement (C3A)[6]. The kidney has a remarkable ability to repair itself following AKI and recover most if not all renal function. The healing process involves repopulation of damaged renal tubules by proliferation of surviving tubular epithelial cells. Renal stem cells also proliferate and contribute to repopulation of the renal tubular epithelium [1].

Although pathogenesis of AKI has been explored on many levels, the epigenetic studies of this disease have merely just begun. Based on what we know from other model systems, epigenetic processes are likely to be involved in all important stages of AKI, including priming and tolerance [7,8,9,10].

In this article we provide an overview of general epigenetic mechanisms, review studies that explored epigenetic mechanisms of AKI in human disease and animal models and discuss potential diagnostic and therapeutic implications and challenges for the future epigenetic field of AKI.

Chromatin and epigenetics

The classical definition of epigenetics refers to changes in gene expression states that are preserved through mitosis and meiosis but do not involve changes in DNA sequence. Although some objection have been raised [11], today the term epigenetics refers to studies of chromatin events with or without known heritability features [12]. Epigenetic information is encoded through covalent modifications of histones and DNA, nucleosome position and substitution by histone variants.

Chromatin

Chromatin is a complex of DNA and proteins found inside the nuclei of eukaryotic cells. Its remarkably dynamic structure plays a critical role in transcription, DNA replication and repair [13]. It is made of nucleosome arrays that are packed into higher order structures by accessory factors. Two main functional states of chromatin, hetero- and eu-chromatin, are defined by microscopically dense, closed for transcription and by transparent actively transcribed structures respectively. A nucleosome consists of ~147 base pairs of DNA wrapped 1.7 times around a core histone octamer (two of each of H2A, H2B, H3 and H4). Mammalian genome has ~1.5x107 nucleosomes that are not only structural elements but also appear to act as information microprocessors through diversity of protein-protein interactions [14]. Here, the richly modified histone N-and C-termini protrude outside the nucleosome particle like “antennas” to serve as communication portals. Similar to the core histones, the linker histone H1 is also modified and is interactive [15]. Chromatin modifying enzymes (for histones and DNA) and associated factors are grouped into three conceptual classes: writers, erasers and readers [16]. Writers and erasers are enzymes that catalyze addition and removal of post-translational modifications respectively. Readers recognize and bind histone/DNA modifications, and cause structural transitions within chromatin and associated changes of expression of target genes.

Methods to study chromatin

Powerful methods have been developed to study chromatin biology. These include chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays for transcription and histone changes [17], sodium bisulfite conversion [18] and methylated DNA immunoprecipitation (MeDIP) [19] for DNA methylation analysis, chromosome conformation capture (3C) to study 3D topology [20], and genetic manipulations for functional studies [21,22]. ChIP is a potent method used to study the interactions of proteins (or specific modified forms of proteins) with DNA in vitro and in vivo. ChIP allows not only to detect binding of a protein with a specific region of the genome but also to give a relative density of this interaction. The ChIP assay represents a major advancement in the study of chromatin processes and its use has increased dramatically over the last few years. ChIP DNA can be tested with one of several detection methods including, dot/slot blot, PCR or qPCR [23], hybridization to a DNA microarray (ChIP-chip) [24], or sequenced using a rapid sequencing technology (ChIPseq) [25]. Enrichment of a sequence of interest over other sequences where the factor is not expected to bind, provides a measure of protein factor interaction with the sequence. A similar approach, designated MeDIP can be used to assay DNA methylation using antibodies to either 5mC or 5hmC [19]. Introduction of 3C techniques provided important insights how chromatin looping could juxtapose distal enhancers with promoters to regulate transcription [20].

Chromatin changes in AKI

We present the review of epigenetic changes in AKI in the following order: chromatin organization, DNA methylation, histone modifications and variants. Epigenetic studies in AKI are listed in Table 1. Epigenetic drugs tested in AKI models are included in Table 2.

Table 1.

Chromatin alterations in acute kidney injury.

| Chromatin | Renal injury mark | Compartment | Assay(s) use | Chromatin response to AKI | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3D structure | Rhabdomyolysi Cisplatin | Mouse kidney Human HEK 293 | 3C ChIP | HO-1 gene promoter-enhancer looping | [22] |

| Remodeling | I/R ATP depletion | Mouse cortex Human HK-2 | ChIP | BRG1 remodeler activates Tnf-α and MCP-1 gene transcription | [21,36] |

| DNA methylation | I/R | Rat kidney | NaHSO3 sequencing | ↓5mC IFNγ-responsive element in C3 complemen promoter | [50,] |

| Transplant | Human urine | Meth-PCR | ↑5mC CALCA promoter | [51] | |

| I/R | Mouse kidneys | HMeDIP Immunoblot | ↓5hmC global and Cxcl10 and Ifngr2 promoters | [52] | |

| Acetyl-histone | I/R ATP depletion | Mouse kidneys Rat NRK-52E | IHC Immunoblot | ↓ then ↑ Acetyl H3 ↓HDAC5 & ↑BMT7 | [61] |

| I/R | Mouse cortex | ChIP | ↑H3K9Ac at HMGCR gene | [35] | |

| I/R | Mouse kidney Rat NRK-52E | ChIP Immunoblot HDAC activity | ↑H4Ac IL-6 and IL-12b promoters ATF3&HDAC1 bind to IL-6 and IL-12b promoters ATF3 protects against AKI | [62] | |

| Endotoxin | Mouse kidney Rat NRK-52E | Immunoblot | ↓H3Ac, ↑HDAC2 & ↑HDAC5 | [63] | |

| UUO | Mouse kidney | Immunoblot IHC | ↓H3Ac ↑HDAC2 & ↑HDAC5 | [64] | |

| I/R | Mouse kidney H1299, HeLa, 292T/17 | IHC Immunoblot | ↓H4K5, ↓H3K12 and ↑H3K14 ↓HATs (JADE15, JADE1L and HBO1) | [65] | |

| UUO | Mouse kidney | IHC Immunoblot | No effect acetyl-histone H3 | [71] | |

| I/R | Mouse cortex | ELISA | ↑H3Ac in whole cortex | ||

| Methyl-histone | ChIP | ↑H3K9/14Ac at Tnf-α, MCP-1, TGFβ, IL-10, HO-1, ColII, NGAL, HMGCR genes | [66] | ||

| Maleate Endotoxin UUO | Mouse cortex Human HK-2 | ChIP | ↑H3K4m3 at Tnf-α, MCP-1, HMGCR genes | 21,34,35 | |

| I/R | |||||

| Azotemia | Human urine | ChIP | ↑H3K4m3 at MCP-1 gene | [93] | |

| Histone variants | I/R | Mouse cortex Human HK-2 | ChIP | ↑H2A.Z at Tnf-α, MCP-1 HMGCR genes | 21,35,36 |

Table 2.

Epigenetic agents tested in acute kidney injury models.

| Drug | Molecular target | Model | Response/Effect | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAHA Valproic acid | Class HDACi | Rat model of hemorrhagic shock | ↑Acetyl-histone Protected kidney cells from apoptosis | [69] |

| Valproic acid | HDACi | Mouse adriamycin-induced nephropathy | ↑Acetyl-histone Renoprotective | [70] |

| MS-275 | Class I HDACi | Mouse UUO | ↑Acetyl-histone Renoprotective through ↓TGFβ | [71] |

| TSA | HDACi | Mouse renal I/R Mouse UUO | ↑Acetyl-histone Renoprotective through ↑BMP7 | 61,63,72 |

| Dexmedetomidine | alpha2-adrenoceptor agonist | Mouse cecal ligation and puncture (sepsis) | ↓HDAC2, ↓HDAC5, ↓Tnf-α, ↓MCP-1, ↑BMP-7 Renoprotective | [63] |

| Resveratrol SRT-2183 | Sirt1 (HDAC) activator | Mouse UUO | ↑Cox2 Renoprotective | [73] |

| SRT-1720 | Sirt1 (HDAC) activator | Mouse renal I/R | Renoprotective | [75] |

| Curcumin | p300/CBP (HAT) inhibitor | Rat cisplatin | Renoprotective ↓Tnf-αsynthesis | [82] |

| Rat endotoxemia | Renoprotective | [81] | ||

| Rat renal I/R | Renoprotective | [83] |

Topology of higher-order chromatin organization

The first level of chromatin organization is the nucleosomal “beads-on-a-string” chromatin fiber with diameter measuring 11-nm compared to 2-nm DNA double-helix. The second structural organization level is the 30-nm packed nucleosomal fiber that has been modeled as either one-start helix or solenoid or two-start helix or zig-zag [26]. The equilibrium between the 11-nm and 30-nm states is dependent on the extent of histone acetylation and density of histone variants such as H2A.Z. Deposition of the linker histone H1 and its modification/variants is also playing a role. The processes that pack the chromatin into higher order structure including the most compact 1400-nm metaphase chromosome involve long-range interactions and chromatin looping mediated by architectural protein scaffolds and interactions with nuclear matrix [26]. Dynamics of higher-order chromatin structure is emerging as one of the major determinants of gene regulation.

Higher-order structural alterations of chromatin in AKI

There is little known about alterations of higher-order chromatin structure in AKI. In other systems it has been shown that hypoxia, one of the causes of AKI, induces condensation of chromatin [27].

Heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) is an anti-inflammatory cytoprotective enzyme induced in various forms of AKI. Kim et.al. generated a transgenic mouse expressing human HO-1 which they used to study regulation of this gene in AKI induced by either glycerol or cisplatin [22]. Using 3C assay the authors demonstrated for the first time that AKI-induced long range interaction between the HO-1 enhancer and promoter is associated with transcriptional activation of this gene. Looping also involves insulator protein CTCF [28]. The authors showed that in their model looping involved not only CTCF but also transcription factors USF1 and Sp1[22].

ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling

The compact structure of chromatin represents a physical obstacle to molecular interactions that drive transcription. Several processes were described that open-up, or relax, chromatin structure, thereby exposing docking sites for the binding of transcription factors, and providing RNA polymerase II (Pol II) with access to the DNA template. ATPase-catalyzed nucleosome moving, ejecting or restructuring are referred to as nucleosome remodeling [29]. The arrangement of nucleosomes with respect to the transcription start site (TSS) plays an important role in regulating transcription. Genome-wide studies have revealed that nucleosomes are specifically positioned (phased) relative to the TSS at transcribed but not silent genes [30]. Control of such phasing provides a way to regulate accessibility of promoters/enhancers to transcription factors [30]. Elongation of Pol II through natural templates also depends on nucleosome remodeling activity of FACT complex (facilitates chromatin transcription) which destabilizes nucleosomes by H2A-H2B dimer removal during polymerase passage [31].

Besides FACT, there are several other highly conserved multi-protein chromatin remodeling complexes, which include SWI/SNF, NURF and NuRD [29]. Although they have different subunit compositions; however, all depend on helicase-like ATPase activity that regulates chromatin structure in similar fashion. The general view is that the ATPases of these complexes act as molecular “motors” that facilitate dynamic changes in chromatin structure at both active and inactive genes. For example, the human SWI/SNF complex contains ATPase activity, and is capable to slide nucleosomes along DNA to make transcription start sites more accessible. The human SWI/SNF complex contains either the BRG1 or BRM ATPase catalytic chromatin remodeling subunit. In the mouse, BRG1 but not BRM is pivotal in nucleosome remodeling complexes [32]. Given that looping and long-range interactions require physical flexibility of nucleosome arrays, it is not surprising that chromatin remodelers such as BRG1 also play an essential role in the formation of specific chromatin loops [33].

Nucleosome remodeling during AKI

Expression of a host of pro-inflammatory cytokines/chemokines such as TNF-α and MCP-1 is increased in AKI. Expression of these genes in AKI is, at least in part, transcriptionally mediated as evidenced by increased recruitment and elongation of Pol II at these genes [21,34,35]. AKI stimulates BRG1 expression in the renal cortex [36]. Naito et.al. used a renal ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) mouse model of AKI to examine the role of chromatin remodeling in the activation of pro-inflammatory genes TNF-α and MCP-1 (Fig. 1)[21]. I/R induced sustained (up to 7 days) expression of TNF-α and MCP-1 mRNA in renal cortex, changes that were matched by increased Pol II recruitment to the genes implicating transcription control. These studies revealed higher levels of BRG1 at the 5′ and 3′ ends of TNF-α gene in injured kidneys, compared to controls. These effects were observed as early as 2hrs post I/R and were sustained for a week. The BRG1 levels in the intergenic 3′ 5kb flanking region were low and not different between the clamped and contralateral kidney. Similar results were obtained along the MCP-1 gene locus. The time-course profiles of increases of BRG1 levels along the TNF-α and MCP-1 loci were similar to that observed for Pol II. These observations suggest that the inducible recruitment of BRG1 plays a role in the induction of these genes in response to renal ischemia.

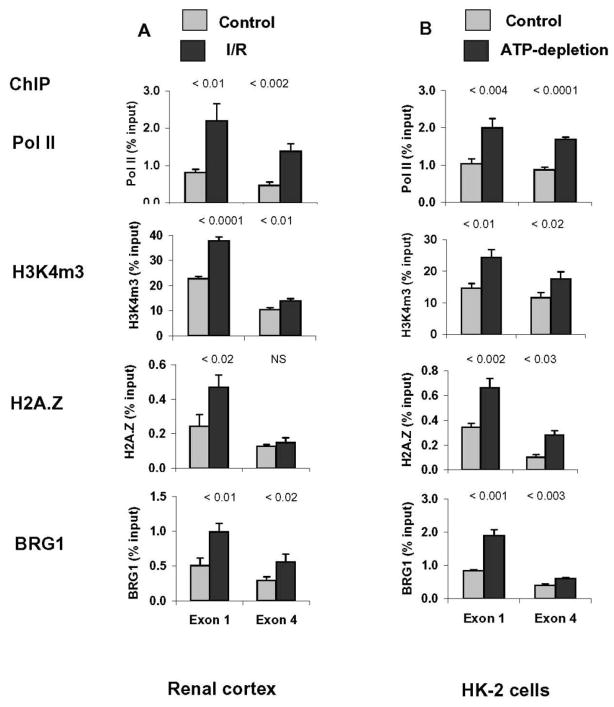

Fig. 1. Comparison of Pol II, H3K4m3, H2AZ and BRG1 along the TNF-α gene in renal cortex following ischemia/reperfusion (A) and in proximal tubule HK-2 culture following reversible ATP depletion.

A, Renal cortical chromatin was prepared from mice subjected to unilateral ischemia/reperfusion (I/R). Renal cortical chromatin from the contralateral kidney of the same animal was used as control (Control). A, Levels at the TNF-α first (Exon 1) and the last (Exon 4) exons were assessed using Matrix ChIP assays. Results are expressed as % input DNA, mean ± 1 SD, n=3 mice. B, Cells were subjected to 4 hrs of ATP depletion using antimycin A plus 2-deoxyglucose treatment, and 2 hrs of recovery (ATP depletion). Simultaneously treated cells, subjected to the same experimental protocol but without a prior ATP depletion served as controls (Control). Chromatin was isolated and sheared. Density of given factors and marks at the first and the last exons of TNF-α and were assessed using Matrix ChIP assays. Results are expressed as % input DNA, mean ± 1 SD, n=3. Adapted from Naito et.al. [21] with publisher’s permission.

The combination of antimycin A (AA) and 2-deoxyglucose depletes intracellular ATP, mimicking oxygen deprivation in cultured cells [8]. AA treatment stimulates TNF-α mRNA and protein syntheses in proximal tubule HK-2 cells [8] recapitulating the in vivo expression of this gene in response to ischemia (Fig. 1). ATP depletion in HK-2 cells also increased Pol II density along both the TNF-α and MCP-1 genes (Fig. 1). This observation suggested that the induction of pro-inflammatory genes in vitro, at least in part, was also transcription-dependent. Like in vivo, the ATP-depletion mediated recruitment of BRG1 to these genes was similar to Pol II profile. The fact that BRG1 was recruited to TNF-α and MCP-1 genes in vivo and in vitro provided evidence that BRG1 plays an essential role in inducible expression of these genes in AKI. This notion was confirmed by decreased expression of TNF-α (Fig. 2) and MCP-1 in BRG1 knockdown experiments in HK-2 cells [21].

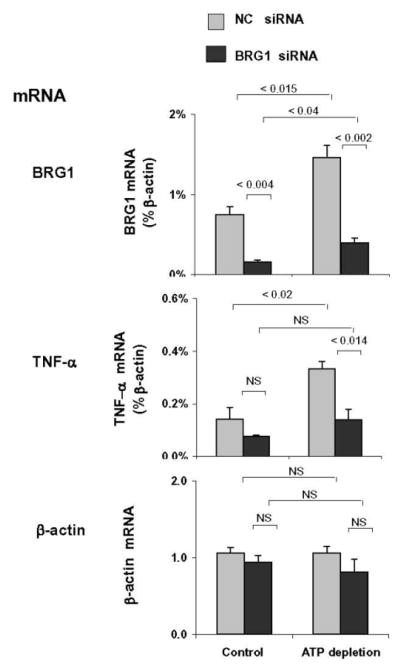

Fig. 2. Effects of siRNA BGR1 knock-down on the ATP-depletion induced expression of TNF-α in proximal tubule HK-2 cell culture.

After transfection with either BRG1 siRNA (BRG1 siRNA) or non-complementary siRNA (NC siRNA), HK-2 cells were treated either without (Control) or with AA/DOG (ATP depletion). Total RNA was extracted, reverse transcribed and transcript levels were assessed by real-time PCR done in triplicates using specific primers. mRNA levels are expressed as a ratio to beta-actin transcript. Results are shown as mean ± 1 SD, n=3. Adapted from Naito et.al. [21] with publisher’s permission.

DNA methylation

The epigenetic role of 5mC, so called the fifth base, has been clearly established [37]. DNA methylation in mammals is the transfer of methyl groups from S-adenosyl methionine (SAM-CH3) to cytosines in the CpG dinucleotides, 5mCpG also designated as 5mC [38]. The majority of CpGs within the mammalian genome are methylated. The mammalian genome is overall depleted of CpGs except for regions in the vicinity of promoters where CpGs can stretch over few hundred bases. These long regions of CpGs are referred to as CpG islands and can be found in intragenic as well as gene body regions. CpG islands located near transcription start sites are less methylated that those found in other regions. Moreover, nearly half of all the CpG islands contain TSS reflecting their importance in transcription initiation. Recently regions of CpGs designated as CpG shores have been identified and are present outside CpG islands as far as 2kb [37]. Methylation of CpG islands and CpG shores is highly correlated with transcriptional repression. This is thought to result from a blockade of transcription factor binding to genomic targets [39]. There is evidence that in some cases methylation of CpG within gene bodies is associated with higher levels of transcription but the mechanism for this phenomenon is unknown [37].

DNA methylation is catalyzed by a family of DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) [40]. Replication of DNA methylation patterns through cell division is maintained by DNMT1 [41]. De novo methylation is catalyzed by structurally related DNMT3a and DNMT3b [42]. DNMTs are recruited to specific genome sites through their association with transcription and chromatin factors. Depending on the context, they interact with multiple other proteins that connect DNA methylation to other chromatin processes, such as histone deacetylation, methylation and ATPase-dependent remodeling [43].

Methylated CpGs are specifically bound by methyl-CpG binding proteins (MBP). Three families of mammalian MBPs have been identified: MBD, UHRF, and zinc-finger proteins. After binding to methylated DNA, MBPs recruit DNMT1 and other proteins that function in maintaining the DNA methylation, heterochromatinization and transcriptional repression [44].

DNA demethylation can take place either passively or actively. Passive demethylation takes place during cell division when newly synthesized DNA strands are not methylated due to inactivation of corresponding DNA-methyltransferase. Active demethylation in mammalian cells takes place through a series of alternative chemical reactions that involve deamination and/or oxidation of 5-methyl-cytosine to a substrate that is recognized by the base excision repair (BER) pathway which replaces the modified base with unmodified cytosine [45,46]. One of the recently discovered pathways involves ten-eleven translocation proteins (Tet1, Tet2 and Tet3). Tet enzymes add a hydroxyl group to the methyl group of 5mC to yield 5hydroxymethyl cytosine, 5hmC. There are two pathways that can then covert 5hmC into unmethylated cytosine [47]. Despite their seemingly circuitous routes, 5mC demethylation can be readily induced and as in the case of estrogen treatment DNA methylation-demethylation processes can rapidly cycle at some promoters [46].

Discovery of 5hmC in 2009 made it the sixth base [48]. The emerging evidence suggests that 5hmC control gene expression and its levels are altered in disease. The total levels of 5hmC in different tissues are ten times lower than 5mC. While the relative quantity of 5mC is the same in all tissues examined, the amount of 5hmC is highest in the brain, intermediate in the kidney but low in liver [49].

DNA methylation alterations in AKI

There are only few studies that examined changes in DNA methylation in AKI. First evidence that AKI causes changes in DNA methylation was published in 2006 by Pratt et.al. [50]. Expression of complement C3 in the kidney is induced by renal ischemia-reperfusion. Using bisulfite sequencing they demonstrated demethylation of a cytosine residue in the INF γ-responsive element within the C3 promoter in response to cold ischemia in rat kidney. There was further demethylation during subsequent warm reperfusion. In a follow up study the same authors demonstrated that in transplanted rat kidneys demethylation of the C3 promoter persisted for at least six months. At the time, the authors suggested that I/R causes progressive oxidation of 5mC as a mechanism of C3 promoter demethylation. Given what we know today about active demethylation and the role of Tet proteins their suggestion was quite prophetic [48].

Mehta et.al. used quantitative methylation-specific PCR to examine DNA methylation of gene promoters in urines of kidney transplant patients [51]. They found that urines of kidney transplant recipients had higher DNA methylation levels in calcitonin (CALCA) promoter compared to healthy controls. There was a trend for the DNA methylation levels to be higher in patients with biopsy-proven acute tubular necrosis compared to those that had acute rejection and slow or prompt graft function. These results suggested that the increased 5mC levels were the result of ischemic injury. Moreover, the levels of CALCA promoter methylation were higher in patients that received cadaveric compared to living donors. Given the observation that cadaveric kidneys suffer injury from procurement and cold ischemia provides further evidence that the aberrant CALCA promoter methylation results from ischemia [51].

The above studies demonstrated that AKI can cause changes in promoter DNA methylation but the effects may be such that for some genes there is 5mC increase while for others there could be a decrease. This is not unexpected given the fact that 5mC levels are regulated by multiple pathways involving activities of DNA methylation writers and erasers.

Huang et.al recently demonstrated that global levels of renal 5hmC were decreased in a mouse model of I/R-induced AKI [52]. In sharp contrast, there were no changes in global levels of 5mC. These changes were associated with decreased levels of Tet1, Tet2 but not Tet3 mRNA, providing possible explanation for the lower 5hmC levels. Given that cellular 5hmC amounts are ~10X lower than 5mC it would be difficult to detect any increase in 5mC due to lower conversion rates to 5hmC after Tet enzyme levels dropped. Furthermore, using hydroxy-methylated DNA immunoprecipitations (hMeDIP) they identified Cxcl10 and Ifngr2 genes whose promoters exhibited also lower 5hmC levels following I/R. This change was associated with increased expression of these genes. The causal relationship, between the lower 5hmC levels and gene expression changes was not reported.

In sum, there is emerging evidence that AKI is associated with changes in DNA methylation similar to other diseases such as cancer. Given that DNA in the urine has been used to report changes in 5mC and 5hmC levels, this approach may be used to develop novel AKI biomarkers. Advantage of using DNA is superior sensitivity of detection.

Histone post-translational modifications (PTMs)

More than 100 different histone amino acid residues have been shown to be modified [13]. Covalent modifications of histones serve as docking sites for transcriptional regulators that change chromatin structure into open (activated) or closed (repressed) transcriptional states. Specific PTMs do not necessarily specify by themselves that a given region is transcribed or not. Rather, enrichment of repressive marks is associated with low rates of transcription and vice versa higher levels of activating modifications are found in transcribed regions.

Many enzymes that modify specific histone amino acid residues have already been identified. The list continues to expand, and a new nomenclature for classifying these changes has recently been adopted [13,53]. Key enzymes include histone methyltransferases, demethylases, acetyltransferases, deacetylases, kinases, phosphatases, and other [13,53]. Many, if not most of these enzymes, are directly recruited to specific genomic regions. Several histone-binding domains of these regulators have been identified: as examples, the chromodomain of HP1 binds to histone H3 methylated at Lys9 (H3K9m3) [54] and the bromodomain, such as that found in BRG1[55], recognizes acetylated histone (H3K9Ac).

Histone acetylation

The compact repressive chromatin structure is in part maintained by the electrostatic interaction of the positively charged histone amino acid residues and the negatively charged DNA. Acetylation of histone lysines eliminates their positive charge which alters structure of chromatin, essentially making it more open for transcription. In addition, acetylated histone residues serve as docking sites for factors that facilitate transcription. All four histones that compose the nucleosome are acetylated [14]. Multiple acetyl transferases are known that exhibit promiscuous activity towards histone amino acid residue substrates [56]. Histone acetylation can change rapidly in response to a host of extracellular signals to generate permissive chromatin structures [57].

Histone acetylation is catalyzed by histone acetyltransferases (HAT). Five classes of HATs are known; p300/CBP, GCN5/PCAF, MYST/MOF, general transcription factors (e.g. TAF1) and nuclear hormone receptor-related [56]. As most of these factors bind to gene promoters, histone acetylation is enriched at the 5′-ends of genes.

Histone deacetylases (HDACs) tighten chromatin structure and repress gene expression through the removal of acetyl groups from histone tails. HDACs are divided into three classes according to homology to founding proteins in yeast, Rpd3p (Class I), Hda1p (Class II), and NAD-dependent enzymes that are similar to the yeast Sir2p (Class III) [58]. There are several available pharmacologic agents that target these enzymes [59] and some of them are already being used therapeutically [60].

Histone acetylation alterations in AKI

In 2008 Marumo et.al. first reported changes in histone acetylation in response to renal ischemia. Clamping of the renal pedicle for 40min decreased levels of histone acetylation in the proximal tubule cells of the outer medulla, a region that showed most severe injury [61]. 24hrs after reperfusion there was total recovery of acetylated histone levels indicating the transient nature of these changes. The authors recapitulated the mouse observations in vitro with transient energy depletion using antimycin. The recovery of histone acetylation following energy repletion resulted from decreased HDAC5 expression. Interestingly, HDAC1-4, and HDAC7 levels did not change indicating selective inhibition of HDAC5. The authors suggested that HDAC5 acts as a sensor that transmits signals to chromatin in response to changes in cell energy state.

Renal injury increases transcription of HMG CoA reductase (HMGCR) resulting in increased cholesterol synthesis, a process thought to contribute to cytoprotection. Naito et.al demonstrated that in I/R model of AKI, up regulation of the HMGCR gene expression was associated with increased levels of H3K9Ac along this locus, a change that might contribute to increased transcription of this gene [35].

Different forms of AKI, including I/R, induce expression of the transcriptional repressor ATF3. This factor is thought to play a protective role in AKI by down-regulating inflammatory cytokine gene expression. Li et.al. examined transcriptional mechanisms of ATF3 action [62]. They demonstrated that hypoxia followed by reoxygenation in vitro increased recruitment of ATF3 to pro-inflammatory IL-6 and IL-12b gene promoters, an effect that suppressed expression of these genes. I/R increased renal HDAC activity that was associated with increased expression of HDAC1 but not HDAC3 protein. Renal I/R increased levels of histone H4 acetylation at the IL-6 and IL-12b promoters, an effect that was greater in ATF3-KO mice. HDAC1 and ATF3 interacted in vivo and vitro and recruitment of HDAC1 to IL-6 and IL-12b promoters was ATF3-dependent. HDAC1 knockdown using lentivirus short-hairpin RNA injection into renal arteries worsened outcomes of I/R-induced injury. In sum, this study demonstrated that ATF3 mediated recruitment of HDAC1 to promoters of pro-inflammatory genes limits I/R-mediated renal injury [62].

Several other studies have examined AKI-induced histone acetylation changes in the kidney (Table 1). Hsing et.al. showed that in kidneys from septic mice total acetyl-histone H3 levels assessed by Western blot analysis decreased, changes associated with increased expression of HDAC2 and HDAC5 [63]. Similarly, Marumo et.al. found that in mouse unilateral ureteral obstruction (UUO) model, acetylated histone H3 levels in the injured kidney also decreased, a change associated with increased HDAC1 and HDAC2 but decreased HDAC7 levels [64]. Havasi et.al. using mouse I/R AKI model reported time-dependent decrease in the levels of acetylation of H4K5 and H3K12 and increase in H3K14 [65]. These observations are consistent with the notion that like most epigenetic changes histone acetylation is a dynamic process. Zager et.al. using ELISA assay of renal cortex samples found increased renal acetylated histone H3 levels post I/R, changes seen 1 day post injury that persisted for up to 3weeks [66]. The apparent discrepancies between the different studies that examined changes in total acetylated histone levels in injured kidney may reflect different forms of renal injuries and/or the time points when the measurements were carried out.

Although there are relatively few studies, the evidence is compelling that histone acetylation plays an important role in acute kidney injury (Table 1). Given that increased renal histone acetylation in some models of kidney injury can persist for weeks [66], this epigenetic change is likely to play an important role in progression to chronic kidney disease. This notion is supported by renal protection effects of some acetylation drugs discussed below.

The disease induced changes in acetylation have been an impetus to test small molecules that target HDACs in models of AKI (Table. 2). There is a substantial list of available HDAC inhibitors, some of them have been used clinically to treat cancer and other diseases, but none so far have been used specifically to ameliorate AKI in patients. Sodium butyrate and trichostatin A (TSA) were discovered 40 and 20 year ago, respectively, as inhibitors of cell proliferation. Valproic acid, discovered serendipitously nearly 50 years ago, is one of the most prescribed antiepileptic drug worldwide [67]. Later on these compounds were found to have HDAC inhibitor properties. Suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA or vorinostat), structurally-related to TSA, is clinically approved agent for treatment of refractory cutaneous T-cell lymphoma [68]. Zacharias et.al. demonstrated the SAHA and valproic acid increased histone H3 acetylation and protected kidney cells from apoptosis in a rat model of hemorrhagic shock [69]. The valproic acid effectiveness in elevating histone H3 acetylation has also been shown to be renoprotective in a mouse model of adriamycin-induced nephropathy [70]. Similarly, using class I HDAC inhibitor, MS-275, Liu et.al. described increases in the total levels of acetyl-histone H3 and renoprotective effects in a UUO mouse model of renal injury[71]. There is evidence that HDAC inhibitors, such as TSA, may exert renal protective actions by increasing expression of BMP7 driven by increased histone acetylation [61,72]. Thus, BMP7 might be a key factor mediating the renoprotective action of the HDAC inhibitor class of agents.

The mammalian ortholog of yeast Sir2 NAD+ -dependent deacetylase sirtuin 1 (Sirt1) is a widely expressed enzyme including the kidney. Sirt1 is found bound to chromatin where it suppresses expression of stress and aging-related genes. Like most deacetylases Sirt1 targets histone and non-histone proteins. He et.al. demonstrated that in UUO mouse model of kidney injury Sirt1 knock-down increased renal apoptosis and fibrosis [73]. Sirt1 activators, resveratrol or SRT-2183, improved cell survival in primary mouse renal medullary culture. In this model Sirt1 appears to exert its beneficial effect by maintaining Cox2 gene expression to protect from oxidative injury. Using ChIP assays the authors demonstrated constitutive binding of Sirt1 to Cox2 promoter but the target(s) of the deacetylase action were not determined [73].

Younger mice are less susceptible to develop AKI [74,75]. Fan et.al. found that kidneys from younger mice (2-month-old) expressed higher Sirt1 levels compared to older animals (4-month-old). Sirt1 activator SRT-1720 protected the renal tubules and function following I/R in adult mice. Sirt1 heterozygotes (Sirt +/−) were more susceptible to renal I/R injury compared to wild-type mice (Sirt +/+). Examining various markers of apoptosis the authors concluded that Sirt1 enhances resistance to I/R induced AKI by suppressing cell death [75].

Members of the bromodomain and extraterminal (BET) subfamily of human bromodomain proteins (BRD2, BRD3, and BRD4) associate with acetylated chromatin and facilitate transcriptional activation by increasing recruitment of complexes that stimulate transcription elongation (e.g. p-TEFb) [76]. Small cell permeable molecules have been introduced that selectively inhibit BET proteins preventing them from binding to histone acetyl-lysine residues [77,78]. One of these histone-mimicking compounds, I-BET, protected mice from endotoxin shock by blocking synthesis of cytokines [78]. Although not tested yet, it seems likely that this new class of bromodomain inhibitors will similarly protect the kidney from injury when increased histone acetylation plays a role.

Turmeric is an Indian ginger spice that has been used for centuries in the treatment of many maladies including arthritis. The principal active compound found in turmeric is the hydrophobic polyphenol curcumin [79]. Given that it is well tolerated, curcumin has shown promise in treatment of arthritis and other inflammatory diseases. Curcumin has targets among different classes of factors and enzymes including the histone acetyltransferase p300/CBP [79,80]. In animal studies curcumin was shown to be renoprotective in models of endotoxemia [81], and AKI caused by cisplatin [82] and ischemia/reperfusion [83]. The protective effects were associated with decreased production of pro-inflammatory mediators such as TNF-α [79,82]. Although in these studies the authors did not examine transcription of target genes, it seems plausible that favorable effects of curcumin on chromatin structure played a role.

Histone lysine methylation

Unlike acetylation, methylation does not change lysine charge, and it alters transcription by providing docking sites for chromatin modifiers. Lysine moiety can be mono- di- and trimethylated. The known methylated sites include six lysine residues in H3 (K4, K9, K23, K27, K36, K56 and K79), K20 of histone H4 and K26 of histone H1. All are located within the histone tails except for H3K79 which is located within the nucleosome core. Modifications of histone tails are critical for gene expression but modifications of residues within the histone core are also thought to play a role in gene expression [84].

H3 lysine 4 methylation

H3K4m1, H3K4m2 and H3K4m3 are generally marks of active transcription. H3K4me2 and H3K4me3 are distributed within the promoters and 5′ regions with H3K4me3 slightly more upstream than H3K4m2, whereas H3K4me1 is mostly located within the transcribed regions and enhancers [85,86]. These modifications have been attributed to mammalian homologs of the yeast Set1 methyltransferase, a component of the COMPASS complex (KMT2A) [87]. Histone lysine methylation is reversed by specific demethylases (KDMs). There are several KDMs that demethylate H3K4m2/3 and participate in transcriptional repression [53,86].

H3 lysine 36 methylation

Higher levels of H3K36m3 have been correlated with enhanced transcription elongation rates [13]. H3K36m3 is thought to facilitate elongation by preventing ectopic transcription initiation within the transcribed region of the gene [88,89]. H3K36m3 mark is enriched towards the 3′-end of genes [86]. This modification is catalyzed by the Set2 methyltransferase which is associated with the CTD of elongating Pol II [90].

H3 lysine 79 methylation

H3K79 methylation has been reported throughout euchromatin regions [91]. This modification is mediated by DOT1L [92].

Silencing methyl histone marks

Levels of di- and trimethylation of lysines 9 and 27 of histone H3, and lysine 20 of histone H4 are enriched at transcriptionally repressed genes [53]. H3K9, H3K27, and H4K20 methylations are mediated by the histone-lysine N-methyltransferases Suv39h1 (KMT1), Ezh2 (KMT6) (part of Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 (PRC2) complex), and Suv4 20h1(KMT5) respectively [53].

Histone methylation alterations in AKI

Increases in level of H3K4m3 were found along TNF –α, MCP-1 and HMGCR genes in mouse models of AKI including those induced by I/R, maleate, endotoxin and UUO [21,34,35](Table 1). These changes were associated with increased expression of Set1 and its recruitment to altered genes suggesting that this enzyme catalyzes H3K4m3 increase [36]. Interestingly, following I/R in a mouse model increased levels of H3K4m3 at these genes were not sustained [21]. The finding that renal cortical H3Km3 levels were increased in mouse model of AKI prompted Munshi et.al. to examine chromatin shed in urines of patients with azotemia where they found increased H3K4m3 mark at the MCP-1 genes [93]. Although of limited scope, this study suggests that urine can be used as a source of histone epigenetic markers not only in AKI but other kidney diseases as well.

We have found in mouse AKI models that at the times when there are changes in H3K4m3 and H3K9/14Ac at TNF –α and MCP-1 genes there were no changes in chromatin repressive marks (unpublished observations). It is possible that changes in these marks become manifested at later times following AKI.

Histone phosphorylation

There are 16 histone residues known to be phosphorylated in mammals [94]. The histone phosphorylation is involved in all aspects of chromatin function including transcription activation and repression, chromatin condensation and DNA repair. Emerging evidence suggests that histone phosphorylation plays a role in cross-talk with other histone modifications (e.g. acetylation) [95]. Given that histone phosphorylation is catalyzed by kinases that are components of signaling cascade, this PTM is likely to play a key role in linking signal transduction pathways to chromatin.

Phosphorylation of histone H3 serine10 (H3S10) is thought to play an important role in initiating transcriptional elongation which together with histone acetylation brings p-TEFb elongation complex to transcribed loci [95]. Several kinases are thought to phosphorylate H3S10 residue (H3pS10), including members of the Aurora, IKKα, MSK1/2, and p90Rsk kinase families [94]. The histone variant H3.3 is specifically enriched at actively transcribed genes. H3.3 differs from the canonical histone H3 by single replacement of alanine 31 to serine residue [96]. H3.3 S31 phosphorylation is mediated by some of the same kinases as H3S10, and it is also associated with higher transcription. [94]. We have found increased H3S10 and H3.3S31 phosphorylation levels at upregulated TNF-α gene in a mouse model of AKI (unpublished observations). Other than these findings, there is no other information available about the role of histone phosphorylation in AKI.

Histone arginine methylation

Histones are known to be arginine methylated on H3R2, H3R8, H3R17, H3R26, H4R3, H2AR11 and H2AR29. Although compared to histone lysine methylation little is known about the functional role of histone arginine methylation there is evidence that this PTMs regulates transcription [97]. There is no information about the role of histone arginine methylation in AKI.

Other histone modifications

Other histone modifications include ubiquitylation, sumoylation, ADP ribosylation, deimination, proline isomerization [13]. More is known about these modifications in yeast rather than mammals. There is no information available about alterations in these modifications in AKI.

Histone variants

Each histone is known to have variants: changes of a few amino acid residues in these variants can evoke profound changes in histone activity, which can up or down regulate genes [98]. Histone variants are generally encoded by different genes and they can differ by as few as one amino acid residue. They are incorporated into nucleosomes to support transcriptional repression and activation. The list of known histone variants is growing and unified nomenclature for histone variants has recently been adapted [99]. The H2A.Z histone variant is highly enriched at sites of active transcription [100], and the substitution of H2A.Z for the canonical H2A histone is increased with stimulation of transcription [101]. At transcribed loci, H2A.Z levels are highest at the transcription start site [100]. Similar to H2A.Z, histone H3.3 is a variant that has been found to replace conventional histone H3 at active genes [102].

Histone variants alterations in AKI

Knowledge about histone variants in organ injury is limited. Nonetheless, it has been shown that different forms of AKI, including I/R (Fig. 1), cause deposition of H2A.Z along pro-inflammatory TNF α, MCP-1 as well as cytoprotective genes [21,35,36].

Relationship between DNA methylation and histone changes in control of gene expression

Given that AKI causes alteration in both DNA methylation and histone modifications, knowledge of the interaction between these two types of epigenetic changes seems important. It is widely agreed that DNA methylation and histone modifications interact closely to control gene expression [103]. Whether DNA methylation controls histone modifications, or vice versa may depend on the specific gene and context. Finally, H2A.Z histone variant and DNA methylation are mutually antagonistic chromatin marks [104]. There is no information available about the interaction of DNA methylation and histone changes in AKI. This is an important issue as defining the hierarchy of DNA and histone modification events will allow us to design better AKI biomarkers [19] and more specific epigenetic therapies [105].

Summary and future directions

Epigenetics has emerged as one of the most intensively studied fields of biology today. The amount of knowledge acquired in the last few years has been spectacular. The rich chromatin landscape and epigenetic alterations in disease are providing unique opportunities for development of novel epigenetic biomarkers and introduction of fundamentally new types of therapies. Yet, compared to, for example, cancer research, AKI has not kept up with the pace of the field. One of the likely reasons for the relatively slow progress in the epigenetic research of kidney injury, is that application of epigenetic tools to study the kidney has until now been challenging. Recent advances in these methods and computational tools make such studies in the kidney considerably more efficient [19,22]. Moreover, the recent technological achievement of single cell analysis of epigenetic marks at specific gene loci in histological sections [106] will surely advance epigenetic studies in an organ as intricate and multicellular as the kidney. Thus the emerging epigenetic field of kidney injury is not only exciting and wide open but is promising to yield new discoveries with unprecedented translational applications.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: Work in authors laboratory was supported by NIH R01 DK083310, R37 DK45978, R21 DK09881, JDRF 42-2009-779 and an anonymous private donation to UW Medicine Research.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: none

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Bonventre JV, Yang L. Cellular pathophysiology of ischemic acute kidney injury. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:4210–4221. doi: 10.1172/JCI45161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chertow GM, Burdick E, Honour M, Bonventre JV, Bates DW. Acute kidney injury, mortality, length of stay, and costs in hospitalized patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:3365–3370. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004090740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coca SG. Long-term outcomes of acute kidney injury. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2010;19:266–272. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e3283375538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kelly KJ. Acute renal failure: much more than a kidney disease. Semin Nephrol. 2006;26:105–113. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2005.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murugan R, Kellum JA. Acute kidney injury: what’s the prognosis? Nat Rev Nephrol. 2011;7:209–217. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2011.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akcay A, Nguyen Q, Edelstein CL. Mediators of inflammation in acute kidney injury. Mediators Inflamm. 2009;2009:137072. doi: 10.1155/2009/137072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nath KA. Renal response to repeated exposure to endotoxin: implications for acute kidney injury. Kidney Int. 2007;71:477–479. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zager RA, Johnson AC, Hanson SY, Lund S. Ischemic proximal tubular injury primes mice to endotoxin-induced TNF-alpha generation and systemic release. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2005;289:F289–297. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00023.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zager RA, Johnson AC, Hanson SY, Lund S. Acute nephrotoxic and obstructive injury primes the kidney to endotoxin-driven cytokine/chemokine production. Kidney Int. 2006;69:1181–1188. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zager RA, Johnson AC, Lund S. ‘Endotoxin tolerance’: TNF-alpha hyper-reactivity and tubular cytoresistance in a renal cholesterol loading state. Kidney Int. 2007;71:496–503. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ptashne M. On the use of the word ‘epigenetic’. Curr Biol. 2007;17:R233–236. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berger SL, Kouzarides T, Shiekhattar R, Shilatifard A. An operational definition of epigenetics. Genes Dev. 2009;23:781–783. doi: 10.1101/gad.1787609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kouzarides T. Chromatin modifications and their function. Cell. 2007;128:693–705. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Musselman CA, Lalonde ME, Cote J, Kutateladze TG. Perceiving the epigenetic landscape through histone readers. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2012;19:1218–1227. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McBryant SJ, Lu X, Hansen JC. Multifunctionality of the linker histones: an emerging role for protein-protein interactions. Cell Res. 2010;20:519–528. doi: 10.1038/cr.2010.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Belkina AC, Denis GV. BET domain co-regulators in obesity, inflammation and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:465–477. doi: 10.1038/nrc3256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nelson JD, Denisenko O, Bomsztyk K. Protocol for the fast chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) method. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:179–185. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Millar DS, Warnecke PM, Melki JR, Clark SJ. Methylation sequencing from limiting DNA: embryonic, fixed, and microdissected cells. Methods. 2002;27:108–113. doi: 10.1016/s1046-2023(02)00061-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu J, Feng Q, Ruan Y, Komers R, Kiviat N, et al. Microplate-based platform for combined chromatin and DNA methylation immunoprecipitation assays. BMC Mol Biol. 2011;12:49. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-12-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dekker J, Rippe K, Dekker M, Kleckner N. Capturing chromosome conformation. Science. 2002;295:1306–1311. doi: 10.1126/science.1067799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Naito M, Zager RA, Bomsztyk K. BRG1 increases transcription of proinflammatory genes in renal ischemia. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:1787–1796. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009010118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim J, Zarjou A, Traylor AM, Bolisetty S, Jaimes EA, et al. In vivo regulation of the heme oxygenase-1 gene in humanized transgenic mice. Kidney Int. 2012;82:278–291. doi: 10.1038/ki.2012.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nelson JD, Denisenko O, Sova P, Bomsztyk K. Fast chromatin immunoprecipitation assay. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:e2. doi: 10.1093/nar/gnj004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huebert DJ, Kamal M, O’Donovan A, Bernstein BE. Genome-wide analysis of histone modifications by ChIP-on-chip. Methods. 2006;40:365–369. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2006.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnson DS, Mortazavi A, Myers RM, Wold B. Genome-wide mapping of in vivo protein-DNA interactions. Science. 2007;316:1497–1502. doi: 10.1126/science.1141319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li G, Reinberg D. Chromatin higher-order structures and gene regulation. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2011;21:175–186. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2011.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnson AB, Barton MC. Hypoxia-induced and stress-specific changes in chromatin structure and function. Mutat Res. 2007;618:149–162. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2006.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bell AC, West AG, Feisenfeld G. The protein CTCF is required for the enhancer blocking activity of vertebrate insulators. Cell. 1999;98:387–396. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81967-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mellor J. Dynamic nucleosomes and gene transcription. Trends Genet. 2006;22:320–329. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2006.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schones DE, Cui K, Cuddapah S, Roh TY, Barski A, et al. Dynamic regulation of nucleosome positioning in the human genome. Cell. 2008;132:887–898. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Belotserkovskaya R, Oh S, Bondarenko VA, Orphanides G, Studitsky VM, et al. FACT facilitates transcription-dependent nucleosome alteration. Science. 2003;301:1090–1093. doi: 10.1126/science.1085703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bultman S, Gebuhr T, Yee D, La Mantia C, Nicholson J, et al. A Brg1 null mutation in the mouse reveals functional differences among mammalian SWI/SNF complexes. Mol Cell. 2000;6:1287–1295. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00127-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim SI, Bresnick EH, Bultman SJ. BRG1 directly regulates nucleosome structure and chromatin looping of the {alpha} globin locus to activate transcription. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009 doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Naito M, Bomsztyk K, Zager RA. Endotoxin mediates recruitment of RNA polymerase II to target genes in acute renal failure. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:1321–1330. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007121368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Naito M, Bomsztyk K, Zager RA. Renal ischemia-induced cholesterol loading: transcription factor recruitment and chromatin remodeling along the HMG CoA reductase gene. Am J Pathol. 2009;174:54–62. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zager RA, Johnson AC. Renal ischemia-reperfusion injury upregulates histone-modifying enzyme systems and alters histone expression at proinflammatory/profibrotic genes. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2009;296:F1032–1041. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00061.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Portela A, Esteller M. Epigenetic modifications and human disease. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28:1057–1068. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Berger SL. The complex language of chromatin regulation during transcription. Nature. 2007;447:407–412. doi: 10.1038/nature05915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Patra SK, Patra A, Rizzi F, Ghosh TC, Bettuzzi S. Demethylation of (Cytosine-5-C-methyl) DNA and regulation of transcription in the epigenetic pathways of cancer development. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2008;27:315–334. doi: 10.1007/s10555-008-9118-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rhee I, Bachman KE, Park BH, Jair KW, Yen RW, et al. DNMT1 and DNMT3b cooperate to silence genes in human cancer cells. Nature. 2002;416:552–556. doi: 10.1038/416552a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yoo CB, Jones PA. Epigenetic therapy of cancer: past, present and future. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5:37–50. doi: 10.1038/nrd1930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen ZX, Riggs AD. DNA methylation and demethylation in mammals. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:18347–18353. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R110.205286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ooi SK, Qiu C, Bernstein E, Li K, Jia D, et al. DNMT3L connects unmethylated lysine 4 of histone H3 to de novo methylation of DNA. Nature. 2007;448:714–717. doi: 10.1038/nature05987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fournier A, Sasai N, Nakao M, Defossez PA. The role of methyl-binding proteins in chromatin organization and epigenome maintenance. Brief Funct Genomics. 2012;11:251–264. doi: 10.1093/bfgp/elr040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kangaspeska S, Stride B, Metivier R, Polycarpou-Schwarz M, Ibberson D, et al. Transient cyclical methylation of promoter DNA. Nature. 2008;452:112–115. doi: 10.1038/nature06640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Metivier R, Gallais R, Tiffoche C, Le Peron C, Jurkowska RZ, et al. Cyclical DNA methylation of a transcriptionally active promoter. Nature. 2008;452:45–50. doi: 10.1038/nature06544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Williams K, Christensen J, Pedersen MT, Johansen JV, Cloos PA, et al. TET1 and hydroxymethylcytosine in transcription and DNA methylation fidelity. Nature. 2011;473:343–348. doi: 10.1038/nature10066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Guo JU, Su Y, Zhong C, Ming GL, Song H. Emerging roles of TET proteins and 5-hydroxymethylcytosines in active DNA demethylation and beyond. Cell Cycle. 2011;10:2662–2668. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.16.17093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Globisch D, Munzel M, Muller M, Michalakis S, Wagner M, et al. Tissue distribution of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine and search for active demethylation intermediates. PLoS One. 2010;5:e15367. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pratt JR, Parker MD, Affleck LJ, Corps C, Hostert L, et al. Ischemic epigenetics and the transplanted kidney. Transplant Proc. 2006;38:3344–3346. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2006.10.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mehta TK, Hoque MO, Ugarte R, Rahman MH, Kraus E, et al. Quantitative detection of promoter hypermethylation as a biomarker of acute kidney injury during transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2006;38:3420–3426. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2006.10.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Huang N, Tan L, Xue Z, Cang J, Wang H. Reduction of DNA hydroxymethylation in the mouse kidney insulted by ischemia reperfusion. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;422:697–702. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.05.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Allis CD, Berger SL, Cote J, Dent S, Jenuwien T, et al. New nomenclature for chromatin-modifying enzymes. Cell. 2007;131:633–636. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cheutin T, McNairn AJ, Jenuwein T, Gilbert DM, Singh PB, et al. Maintenance of stable heterochromatin domains by dynamic HP1 binding. Science. 2003;299:721–725. doi: 10.1126/science.1078572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Trotter KW, Archer TK. The BRG1 transcriptional coregulator. Nucl Recept Signal. 2008;6:e004. doi: 10.1621/nrs.06004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yuan H, Marmorstein R. Histone acetyltransferases: Rising ancient counterparts to protein kinases. Biopolymers. 2013;99:98–111. doi: 10.1002/bip.22128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Flanagin S, Nelson JD, Castner DG, Denisenko O, Bomsztyk K. Microplate-based chromatin immunoprecipitation method, Matrix ChIP: a platform to study signaling of complex genomic events. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:e17. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Thiagalingam S, Cheng KH, Lee HJ, Mineva N, Thiagalingam A, et al. Histone deacetylases: unique players in shaping the epigenetic histone code. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;983:84–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb05964.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Li HL, Liu C, de Couto G, Ouzounian M, Sun M, et al. Curcumin prevents and reverses murine cardiac hypertrophy. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:879–893. doi: 10.1172/JCI32865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 60.Hellebrekers DM, Griffioen AW, van Engeland M. Dual targeting of epigenetic therapy in cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1775:76–91. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Marumo T, Hishikawa K, Yoshikawa M, Fujita T. Epigenetic regulation of BMP7 in the regenerative response to ischemia. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:1311–1320. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007091040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Li HF, Cheng CF, Liao WJ, Lin H, Yang RB. ATF3-mediated epigenetic regulation protects against acute kidney injury. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21:1003–1013. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009070690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hsing CH, Lin CF, So E, Sun DP, Chen TC, et al. alpha2-Adrenoceptor agonist dexmedetomidine protects septic acute kidney injury through increasing BMP-7 and inhibiting HDAC2 and HDAC5. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2012;303:F1443–1453. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00143.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Marumo T, Hishikawa K, Yoshikawa M, Hirahashi J, Kawachi S, et al. Histone deacetylase modulates the proinflammatory and -fibrotic changes in tubulointerstitial injury. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2010;298:F133–141. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00400.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Havasi A, Haegele JA, Gall JM, Blackmon S, Ichimura T, et al. Histone Acetyl Transferase (HAT) HBO1 and JADE1 in Epithelial Cell Regeneration. Am J Pathol. 2013;182:152–162. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zager RA, Johnson AC, Becker K. Acute unilateral ischemic renal injury induces progressive renal inflammation, lipid accumulation, histone modification, and “end-stage” kidney disease. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2011;301:F1334–1345. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00431.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Perucca E. Pharmacological and therapeutic properties of valproate: a summary after 35 years of clinical experience. CNS Drugs. 2002;16:695–714. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200216100-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Brilli LL, Swanhart LM, de Caestecker MP, Hukriede NA. HDAC inhibitors in kidney development and disease. Pediatr Nephrol. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s00467-012-2320-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zacharias N, Sailhamer EA, Li Y, Liu B, Butt MU, et al. Histone deacetylase inhibitors prevent apoptosis following lethal hemorrhagic shock in rodent kidney cells. Resuscitation. 2011;82:105–109. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2010.09.469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Van Beneden K, Geers C, Pauwels M, Mannaerts I, Verbeelen D, et al. Valproic acid attenuates proteinuria and kidney injury. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22:1863–1875. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010111196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Liu N, He S, Ma L, Ponnusamy M, Tang J, et al. Blocking the Class I Histone Deacetylase Ameliorates Renal Fibrosis and Inhibits Renal Fibroblast Activation via Modulating TGF-Beta and EGFR Signaling. PLoS One. 2013;8:e54001. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Imai N, Hishikawa K, Marumo T, Hirahashi J, Inowa T, et al. Inhibition of histone deacetylase activates side population cells in kidney and partially reverses chronic renal injury. Stem Cells. 2007;25:2469–2475. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.He W, Wang Y, Zhang MZ, You L, Davis LS, et al. Sirt1 activation protects the mouse renal medulla from oxidative injury. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:1056–1068. doi: 10.1172/JCI41563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zager RA, Johnson AC, Naito M, Lund SR, Kim N, et al. Growth and development alter susceptibility to acute renal injury. Kidney Int. 2008;74:674–678. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Fan H, Yang HC, You L, Wang YY, He WJ, et al. The histone deacetylase, SIRT1, contributes to the resistance of young mice to ischemia/reperfusion-induced acute kidney injury. Kidney Int. 2013 doi: 10.1038/ki.2012.394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hargreaves DC, Horng T, Medzhitov R. Control of inducible gene expression by signal-dependent transcriptional elongation. Cell. 2009;138:129–145. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Filippakopoulos P, Qi J, Picaud S, Shen Y, Smith WB, et al. Selective inhibition of BET bromodomains. Nature. 2010;468:1067–1073. doi: 10.1038/nature09504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Nicodeme E, Jeffrey KL, Schaefer U, Beinke S, Dewell S, et al. Suppression of inflammation by a synthetic histone mimic. Nature. 2010;468:1119–1123. doi: 10.1038/nature09589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zhou H, Beevers CS, Huang S. The targets of curcumin. Curr Drug Targets. 2011;12:332–347. doi: 10.2174/138945011794815356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Balasubramanyam K, Varier RA, Altaf M, Swaminathan V, Siddappa NB, et al. Curcumin, a novel p300/CREB-binding protein-specific inhibitor of acetyltransferase, represses the acetylation of histone/nonhistone proteins and histone acetyltransferase-dependent chromatin transcription. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:51163–51171. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409024200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Memis D, Hekimoglu S, Sezer A, Altaner S, Sut N, et al. Curcumin attenuates the organ dysfunction caused by endotoxemia in the rat. Nutrition. 2008;24:1133–1138. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2008.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kuhad A, Pilkhwal S, Sharma S, Tirkey N, Chopra K. Effect of curcumin on inflammation and oxidative stress in cisplatin-induced experimental nephrotoxicity. J Agric Food Chem. 2007;55:10150–10155. doi: 10.1021/jf0723965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bayrak O, Uz E, Bayrak R, Turgut F, Atmaca AF, et al. Curcumin protects against ischemia/reperfusion injury in rat kidneys. World J Urol. 2008;26:285–291. doi: 10.1007/s00345-008-0253-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mueller D, Garcia-Cuellar MP, Bach C, Buhl S, Maethner E, et al. Misguided transcriptional elongation causes mixed lineage leukemia. PLoS Biol. 2009;7:e1000249. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Heintzman ND, Stuart RK, Hon G, Fu Y, Ching CW, et al. Distinct and predictive chromatin signatures of transcriptional promoters and enhancers in the human genome. Nat Genet. 2007;39:311–318. doi: 10.1038/ng1966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kooistra SM, Helin K. Molecular mechanisms and potential functions of histone demethylases. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:297–311. doi: 10.1038/nrm3327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Santos-Rosa H, Schneider R, Bannister AJ, Sherriff J, Bernstein BE, et al. Active genes are tri-methylated at K4 of histone H3. Nature. 2002;419:407–411. doi: 10.1038/nature01080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Keogh MC, Kurdistani SK, Morris SA, Ahn SH, Podolny V, et al. Cotranscriptional set2 methylation of histone H3 lysine 36 recruits a repressive Rpd3 complex. Cell. 2005;123:593–605. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Venkatesh S, Smolle M, Li H, Gogol MM, Saint M, et al. Set2 methylation of histone H3 lysine 36 suppresses histone exchange on transcribed genes. Nature. 2012;489:452–455. doi: 10.1038/nature11326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kizer KO, Phatnani HP, Shibata Y, Hall H, Greenleaf AL, et al. A novel domain in Set2 mediates RNA polymerase II interaction and couples histone H3 K36 methylation with transcript elongation. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:3305–3316. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.8.3305-3316.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Shilatifard A. Chromatin Modifications by Methylation and Ubiquitination: Implications in the Regulation of Gene Expression. Annu Rev Biochem. 2006 doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.103004.142422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Okada Y, Feng Q, Lin Y, Jiang Q, Li Y, et al. hDOT1L links histone methylation to leukemogenesis. Cell. 2005;121:167–178. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Munshi R, Johnson A, Siew ED, Ikizler TA, Ware LB, et al. MCP-1 gene activation marks acute kidney injury. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22:165–175. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010060641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Banerjee T, Chakravarti D. A peek into the complex realm of histone phosphorylation. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31:4858–4873. doi: 10.1128/MCB.05631-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Zippo A, Serafini R, Rocchigiani M, Pennacchini S, Krepelova A, et al. Histone crosstalk between H3S10ph and H4K16ac generates a histone code that mediates transcription elongation. Cell. 2009;138:1122–1136. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Hake SB, Allis CD. Histone H3 variants and their potential role in indexing mammalian genomes: the “H3 barcode hypothesis”. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:6428–6435. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600803103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kirmizis A, Santos-Rosa H, Penkett CJ, Singer MA, Vermeulen M, et al. Arginine methylation at histone H3R2 controls deposition of H3K4 trimethylation. Nature. 2007;449:928–932. doi: 10.1038/nature06160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Workman JL. Nucleosome displacement in transcription. Genes Dev. 2006;20:2009–2017. doi: 10.1101/gad.1435706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Talbert PB, Ahmad K, Almouzni G, Ausio J, Berger F, et al. A unified phylogeny-based nomenclature for histone variants. Epigenetics Chromatin. 2012;5:7. doi: 10.1186/1756-8935-5-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Barski A, Cuddapah S, Cui K, Roh TY, Schones DE, et al. High-resolution profiling of histone methylations in the human genome. Cell. 2007;129:823–837. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.John S, Sabo PJ, Johnson TA, Sung MH, Biddie SC, et al. Interaction of the glucocorticoid receptor with the chromatin landscape. Mol Cell. 2008;29:611–624. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Wirbelauer C, Bell O, Schubeler D. Variant histone H3.3 is deposited at sites of nucleosomal displacement throughout transcribed genes while active histone modifications show a promoter-proximal bias. Genes Dev. 2005;19:1761–1766. doi: 10.1101/gad.347705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Burgers WA, Fuks F, Kouzarides T. DNA methyltransferases get connected to chromatin. Trends Genet. 2002;18:275–277. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(02)02667-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Conerly ML, Teves SS, Diolaiti D, Ulrich M, Eisenman RN, et al. Changes in H2A.Z occupancy and DNA methylation during B-cell lymphomagenesis. Genome Res. 2010;20:1383–1390. doi: 10.1101/gr.106542.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Azmi AS, Wang Z, Philip PA, Mohammad RM, Sarkar FH. Proof of concept: network and systems biology approaches aid in the discovery of potent anticancer drug combinations. Mol Cancer Ther. 2010;9:3137–3144. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-0642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Gomez D, Shankman LS, Nguyen AT, Owens GK. Detection of histone modifications at specific gene loci in single cells in histological sections. Nat Methods. 2013;10:171–177. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]