Abstract

Purpose

Submandibular salivary glands (SMGs) dysfunction contributes to xerostomia after radiotherapy (RT) of head and neck (HN) cancer. We assessed SMG dose-response relationships and their implications for sparing these glands by intensity modulated radiotherapy (IMRT).

Patients and Methods

148 HN cancer patients underwent unstimulated and stimulated SMG salivary flow rate measurements selectively from Wharton’s duct orifices, before RT and periodically through 24 months after RT. Correlations of flow rates and mean SMG doses were modeled throughout all time points. IMRT re-planning in eight patients whose contralateral level I was not a target incorporated the results in a new cost function aiming to spare contralateral SMGs.

Results

Stimulated SMG flow rates decreased exponentially by (1.2%)Gy as mean doses increased up to 39 Gy threshold, and then plateaued near zero. At mean doses ≤39 Gy, but not higher, flow rates recovered over time at 2.2%/month. Similarly, the unstimulated salivary flow rates decreased exponentially by (3%)Gy as mean dose increased and recovered over time if mean dose was <39 Gy. IMRT re-planning reduced mean contralateral SMG dose by average 12 Gy, achieving ≤39 Gy in 5/8 patients, without target under-dosing, increasing the mean doses to the parotid glands and swallowing structures by average 2–3 Gy.

Conclusions

SMG salivary flow rates depended on mean dose with recovery over time up to a threshold of 39 Gy. Substantial SMG dose reduction to below this threshold and without target under-dosing is feasible in some patients, at the expense of modestly higher doses to some other organs.

Introduction

Following conventional radiotherapy (RT) of head and neck (HN) cancer, permanent xerostomia has been the most prevalent late sequela, cited by patients as a major cause of reduced quality of life (1). In recent years, many studies utilized intensity modulated radiotherapy (IMRT) to reduce xerostomia by partially sparing the parotid salivary glands (2). These studies demonstrated higher parotid and whole-mouth saliva flows compared with conventional RT. Moreover, saliva production from the spared glands increased significantly over time, unlike conventional RT (3). It had been predicted that parallel improvements in the symptoms of xerostomia would follow. However, this issue was found to be much more complex and uncertain.

Xerostomia is primarily a quality of life (QOL) issue, and similar to other QOL items, patient-reported scores are likely to be more valid and reliable than observer-rated ones like the RTOG/EORTC or Common Toxicity Criteria scores (4, 5). Several studies showed significant correlations between patient-reported xerostomia scores and salivary output (4, 6–9) while others did not (10, 11). Even in the studies which demonstrated statistically significant correlations, the correlation coefficients were modest and a substantial variability in the QOL scores could not be explained by the salivary flow rates alone. Two recent randomized studies comparing IMRT to conventional RT for nasopharyngeal cancer demonstrated the dichotomy between the preserved parotid saliva and xerostomia symptoms: Kam et al found that salivary flows, but not patient-reported xerostomia scores, were significantly better following IMRT compared with conventional RT (12), and Pow et al reported substantially higher salivary flow rates in the IMRT group, however, the improvement in symptoms, while statistically significant, was modest (6).

The likely explanation for the discrepancy between the preserved parotid salivary output and patient-reported xerostomia is that sparing of the parotid glands alone is not sufficient to prevent symptoms of dry mouth. This explanation is based on both the important role of the submandibular glands (SMGs) in secreting saliva in the non-stimulated state (13), and, perhaps most importantly, on the relative lack of mucins in the parotid saliva. Mucins serve as mucosal lubricants and selective permeability barrier of the mucosal membranes and their presence helps maintain these tissues in hydrated state and contribute to patient’s subjective sense of hydration (14). Mucin-secreting glands include the SMGs and the minor salivary glands (15). The important role of the mucin-producing glands has been demonstrated in studies which correlated RT doses to these glands and patient-reported xerostomia (3, 16–17), and in studies which transferred surgically the contralateral SMG to the non-irradiated sub-mental space, resulting in a significant improvement of both SMG salivary flow rates and patient-reported dry mouth symptoms (18).

An increasing body of data has been published in recent years about dose-response relationships for the parotid glands, but no such data exists for the SMGs. An understanding of these relationships is an initial step in the efforts to spare effectively the mucin-producing glands and further improve the modest gains in xerostomia achieved to date by the sparing of the parotid glands alone. We have prospectively measured selective SMG salivary output at the same time points at which we measured parotid gland output, in patients participating in our xerostomia and dysphagia-reducing studies (3, 19). This paper reports the dose-response relationships for the SMGs based on these measurements. In addition, we have examined the potential implications of these data on the sparing of the SMGs by IMRT.

Patients and Methods

Patients

The study involved patients with head and neck cancer treated at the University of Michigan between 1995 and 2005 with primary or postoperative RT, who participated in prospective protocols aiming to spare the major salivary glands (primarily the parotid glands), and recently also aiming to reduce dysphagia. These patients were included in previous publications which analyzed parotid gland dose-effect relationships, the relationships between the parotid and submandibular salivary flows and xerostomia and QOL, or dysphagia-specific endpoints (3–4, 19–23). All patients signed an informed consent approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Michigan.

The techniques employed to achieve parotid gland sparing in patients receiving bilateral neck irradiation evolved over time and have previously been detailed. 3D RT was employed between 1995–1996 (12 patients) (24), multi-segmental IMRT between 1996–2002 (68 patients)(25), and beamlet IMRT since 2002 (36 patients) (19, 26). In addition, 32 patients receiving unilateral neck RT were treated with multi-segmental IMRT. Efforts to reduce the doses to the noninvolved SMGs were made only in recent years, using a low-weight optimization cost function aiming to reduce their doses as much as possible.

SMG Salivary flow measurements

The collected saliva is referred to as submandibular, although it represents the combined submandibular and sublingual secretions that frequently exit through a common orifice, because the sublingual flows represent only 2–5% of the combined flows (27). Samples were collected according to a method introduced by Fox et al (28) and as previously described by our group (3) at a standardized time of day (9 a.m.–12 p.m.) due to diurnal variations in flow. Subjects refrained from eating, drinking and oral hygiene for 90 min. prior to saliva collection. Wharton’s duct orifices at the floor of the mouth were isolated with cotton rolls and saliva was collected with a micropipet attached to gentle suction while blocking other oral secretions by cotton gauzes placed in the buccal and lingual vestibules (Figure 1). Due to the very close proximity of the orifices, measurements were made from both orifices and represent the combined output of the bilateral submandibular glands in each patient. Unstimulated samples were collected first, followed by collection of the stimulated secretions by swabbing 2% citric acid on the dorsolateral surfaces of the tongue at 30 second intervals for two minutes, followed by evacuation of the accumulated saliva, and then a two-minute collection period during which the gustatory stimulation was maintained. The volume of saliva was determined gravimetrically assuming a specific gravity of 1.0, and the flow rate (ml/min) was recorded. Measurements were made before RT started and at 1, 3, 6, 12, 18, and 24 months after the completion of therapy.

Fig. 1.

Selective collection of submandibular/sublingual saliva from Wharton’s duct orifices.

Dosimetry

The SMGs only were contoured for dosimetric purposes because the relative volume of the sublingual secretions is very small, as detailed above. In cases where the SMGs had not been outlined in the planning CT datasets, they were contoured for the purpose of this study. The mean doses were derived from the 3D dose distributions across the glands, which were re-calculated for the purposes of this study using the archived treatment plans. The mean doses were calculated for the whole glands (including the parts encompassed by the targets).

In order to take into account the potential effects of different fraction doses on gland output, the biologically equivalent mean SMG doses normalized for 2.0 Gy/fraction (BED2) were calculated by converting the 3D dose distributions to normalized effective doses, using the linear-quadratic model, assuming α/β ratio of 3 Gy for late effects, without taking treatment time into account (29). The mean BED2s were then calculated for each patient.

IMRT Re-Planning

IMRT re-planning incorporating the new dose-response data was performed in eight patients with stage III/IV oropharyngeal (6 patients) or nasopharyngeal (2 patients) cancer in whom the contralateral neck levels II–IV or II–V, but not contralateral level I, were defined as targets. The original IMRT planning aimed to spare the parotid glands as well as the swallowing structures (pharyngeal constrictors and glottic/supraglottis larynx) while retaining strict target coverage (99% of the PTVs covered by the prescribed dose) and dose homogeneity criteria, as previously detailed (19, 26). Also, the optimization cost function in these plans included a low-weight cost for reducing as much as possible the doses to the parts of the SMGs which were not encompassed by the targets (“reduce dose to 0”). The prescribed doses to gross disease PTV and to the high- and low-risk sub-clinical PTVs were 70 Gy, 60–63 Gy, and 56–59 Gy, respectively, all in 35 fractions, at daily fraction doses of 2.0, 1.8, and 1.6–1.7 Gy, respectively (19). For the purposes of the current study, re-planning included an additional optimization cost function aiming to reduce mean SMG doses to below a threshold found in the current study. This cost function had the same weight as reducing the mean parotid gland doses to ≤ 26 Gy and reducing the mean swallowing structure doses to ≤50 Gy. In both initial plans and replanning, the weights of the optimization goals for the PTVs were higher than the weights of the organ sparing goals (except for the spinal cord maximal dose) to avoid their under-dosage while attempting organ sparing.

Statistical Analysis

Because the SMG saliva flow rates were measured from the orifices of both glands’ ducts, the pre-therapy flow rate was halved to represent the output per gland, unless the patient had pre-therapy ipsilateral neck dissection (which removed the ipsilateral SMG). For the post-RT measurements, if the ipsilateral gland had been removed during neck dissection, or if the mean dose to one gland had been >50 Gy (typically the ipsilateral gland), all measured SMG saliva was regarded to be produced by the contralateral gland, and the mean dose to that gland was used in the dose-response analysis and modeling. In cases where both glands had received >50 Gy, if there was any measured post-RT saliva it was assumed to be produced by the gland receiving the lowest dose. In the few cases where the mean doses to both SMGs had been <50 Gy, the post-treatment saliva was assumed to be produced by both glands and the average of the mean doses of the two SMGs was used for analysis.

When percent saliva and log-transformed percent saliva output relative to base-line were plotted against mean dose by each measurement time, the output decreased with increasing mean dose, but once the dose was greater than a threshold, the output remained close to nil and did not recover over time. To identify objectively the threshold we used a segmented regression model (30) with log transformed percent saliva output as the dependent variable, and mean dose, baseline saliva output, and threshold indicator, as predictors. The threshold indicator separated the glands into two groups of high versus low dose using a mean dose threshold. The model was then iteratively fit using a sequence of indicator variables created using m possible unique values of potential threshold mean dose and the threshold was identified from the indicator variable used in the model that gave the highest R-squared value of the m candidates. In order to find the threshold and to ensure that it did not vary across time, the iterative steps were repeated separately for data at each measurement time.

Once the threshold was identified, a multivariate modeling was done using the indicator variable from the identified threshold and saliva output data from all measurement times to describe the relationship between mean preserved saliva output and dose and to describe the changes in output over time after RT. This was done using the generalized linear model (31) with log link and generalized estimating equation (to account for potential correlation in repeatedly measured saliva output from same patient). The final model included mean dose (Dose), baseline saliva output (Baseline), time since radiation (Time) and the threshold indicator (Ind) as predictors, according to the equation: , where Ind is = 1 if mean dose > threshold; 0 if mean dose ≤ threshold, and β’s are parameters relating each predictor to the mean saliva output multiplicatively.

Results

148 patients participated in the study, of whom 116 had stage III–IV squamous cell carcinoma of the oropharynx, larynx, hypopharynx, oral cavity, or nasopharynx, and received bilateral neck RT. 32 patients had early, well-lateralized tumors (buccal mucosa, retromolar trigone, alveolar ridge, major salivary glands cancer, small tonsillar tumors, or skin cancer with unilateral neck metastasis), and received ipsilateral neck RT. 97 patients received primary RT, and 51 received post-operative RT, all of whom had had ipsilateral neck dissection which included resection of the ipsilateral SMG. Seventy patients (47%) received concurrent chemotherapy. No patient received salivary stimulants or radioprotectors.

The average (SD) and the median of the mean doses to the ipsilateral SMGs were 59 (15) Gy and 65 Gy, respectively. The nominal doses and the BED2 to the ipsilateral SMGs were identical. The contralateral SMG mean doses were lower than the ipsilateral ones in all cases. Average (SD) and median contralateral mean SMG doses were 47 (22) Gy and 57 Gy, respectively. The average (SD) and the median of the mean BED2 to the contralateral SMGs were 42 (21) Gy and 51 Gy, respectively.

Of the 148 patients with post-therapy saliva measurements, 124 had pre-RT measurements. The median post-RT salivary collection times per patient during the 2-year study period was four (range, 1–6). Descriptive statistics of the salivary flow rates at the various measurement time points (for all patients), and their percentages of the pre-therapy flow rates (for the patients with pre-therapy measurements), are detailed in Tables 1 for the stimulated and Table 2 for the unstimulated flows. The majority of the glands produced very little or no saliva after RT, therefore the median output was near zero in most time points, while the mean output was higher due to salivary flows measured in the minority of patients.

Table 1.

Stimulated SMG salivary flow rates at base line and after RT.

| Time* | No. Patients | Flow Rates (cc/min/gland) | % of Baseline | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Mean (SD) | Median | Mean (SD) | Median | ||

| Pre-RT | 124 | 0.24 (0.24) | 0.17 | 100 (0) | 100 |

| 1 | 112 | 0.04 (0.15) | 0.01 | 23 (62) | 1.2 |

| 3 | 108 | 0.04 (0.13) | 0.00 | 25 (63) | 1.3 |

| 6 | 100 | 0.06 (0.11) | 0.00 | 42 (114) | 2.2 |

| 12 | 91 | 0.07 (0.12) | 0.01 | 40 (79) | 5.0 |

| 18 | 62 | 0.06 (0.10) | 0.00 | 48 (108) | 2.1 |

| 24 | 46 | 0.12 (0.26) | 0.01 | 51 (105) | 2.3 |

Months after RT completed

Table 2.

Unstimulated SMG salivary flow rates at base line and after RT

| Time* | No. Patients | Flow Rates (cc/min/gland) | % of Baseline | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Mean (SD) | Median | Mean (SD) | Median | ||

| Pre-RT | 124 | 0.08 (0.10) | 0.05 | 100 (0) | 100 |

| 1 | 112 | 0.01 (0.03) | 0.00 | 28 (672) | 0.0 |

| 3 | 108 | 0.01 (0.03) | 0.00 | 62 (351) | 0.0 |

| 6 | 100 | 0.01 (0.03) | 0.00 | 53 (169) | 0.1 |

| 12 | 91 | 0.02 (0.04) | 0.00 | 84 (251) | 0.4 |

| 18 | 62 | 0.01 (0.03) | 0.00 | 87 (269) | 0.3 |

| 24 | 46 | 0.03 (0.07) | 0.00 | 72 (412) | 2.0 |

Months after RT completed

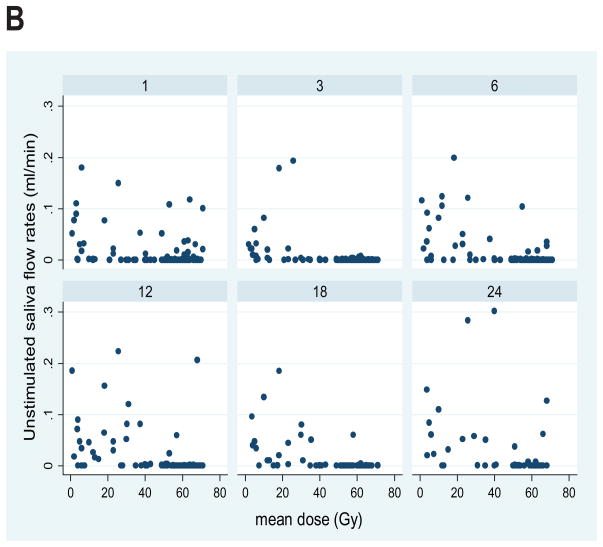

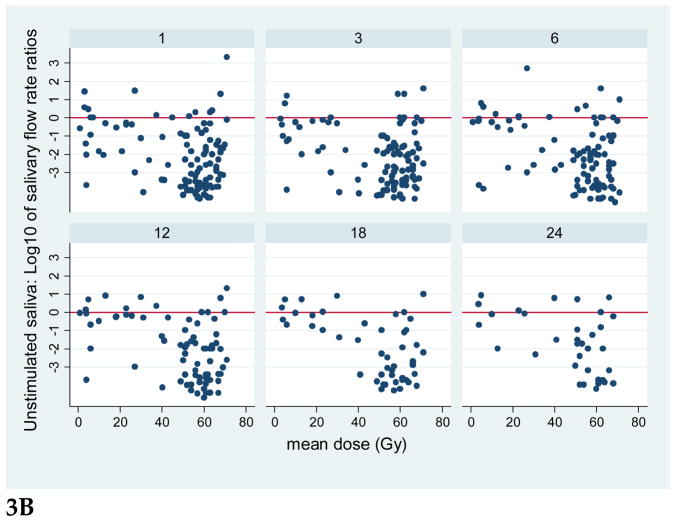

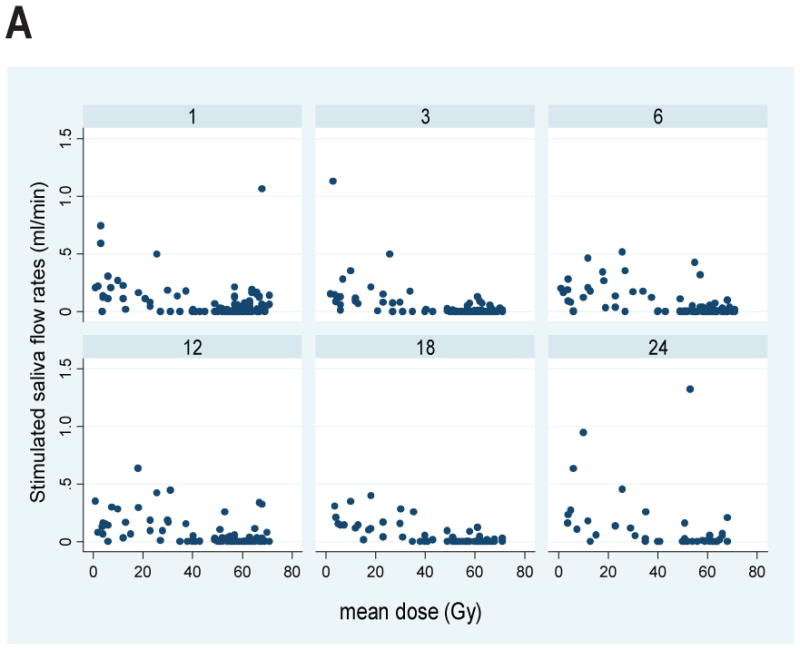

Plots for all patients of the stimulated and unstimulated flow rates at each post-RT time point are provided in Figure 2, and plots of the flow rates relative to the pre-RT values are presented in Figure 3. Graphical exploration of the longitudinal data showed that for both stimulated and unstimulated saliva, the patterns in pre- and post-therapy output/gland over time were very similar between the 51 patients who had had previous ipsilateral neck dissection and had only one (contralateral) gland, or the 86 patients with two glands in whom the ipsilateral gland had received >50 Gy (data not shown). Further exploration of the percent output relative to pre-RT output showed that in patients with one gland, and in patients whose ipsilateral gland received >50 Gy, the output decreased as mean dose to the contralateral gland increased to near 40 Gy, and then it plateaued at no or very little output. Also, the data for the small number of patients (11) whose both SMGs received <50 Gy showed a similar trend (data not shown). Therefore, further analyses combined the data for all patients.

Fig. 2.

Plots of SMG saliva flow rates vs. mean SMG doses at various post-RT time points (1, 3,6,12,18, and 24 months). A. Stimulated, B. Unstimulated salivary flow rates.

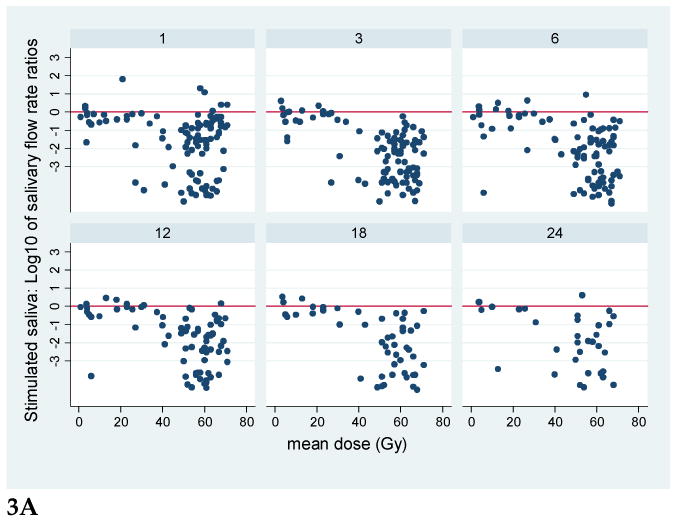

Fig. 3.

Plots of the ratios of SMG saliva flow rates relative to pre-therapy base-line flow rates, vs. mean SMG doses, at various post-RT time points (1.3.6.12, 18, and 24 months). Note the logarithmic scale of the flow rate ratios; the horizontal line at 0 represents values near base-line. A. Stimulated, B. Unstimulated salivary flow ratios.

Modeling of the stimulated saliva flow rates through all post-RT time points showed that the post-RT flow rates tended to decrease exponentially with increasing mean dose, at (1.2%)Gy ( 95% C.I.: 0.2%– 2.6 %; p = 0.09), through 39 Gy, and at higher doses they plateaued at an average of 0.03 ml/min. There was an increase of flow over time (2.2% per month, p = 0.001) when the mean dose was ≤ 39 Gy, but not when the dose was higher. For the relationships between the BED2 and the stimulated saliva, the threshold and trends were similar, with a different coefficient for the reduction in output vs. dose. The threshold for BED2 was found to be 38 Gy, the rate of exponential reduction in flow rates as BED2 increased up to 38 Gy was statistically significant at (4%)Gy (95% C.I. 1.6%–6%; p = 0.001), and the increase in flow over time for glands receiving BED2 ≤38 Gy was 1.9% per month (p=0.03).

The results for the unstimulated saliva flow rates were very similar to those of the stimulated saliva. Post-RT unstimulated salivary flow rates decreased exponentially with the nominal mean dose at (3%)Gy (95% C.I. 1.8%–4.3%; p < 0.001) and increased over time at 3% per month (p = 0.001) if the mean dose was ≤ 39 Gy. At mean doses >39 Gy, the salivary output plateaued to average 0.005 ml/min and did not recover over time. For the BED2, the threshold was the same as that for the nominal dose (39 Gy). Also, for the BED2, the rate of exponential decrease in unstimulated saliva output/Gy increase in dose, and the rate of recovery over time in glands which had received ≤ 39 Gy, were almost identical to the respective estimates for the nominal doses. Both were statistically significant (p = 0.001 and p < 0.001, respectively).

Chemotherapy was associated with high target and SMG doses, therefore its potential effect could not be assessed in this series.

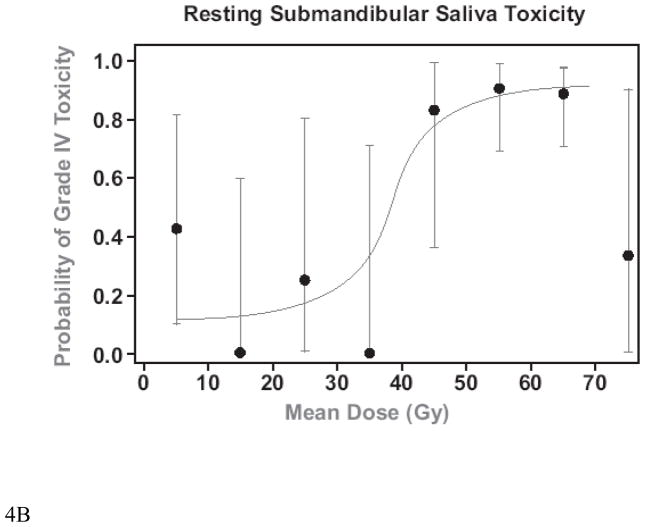

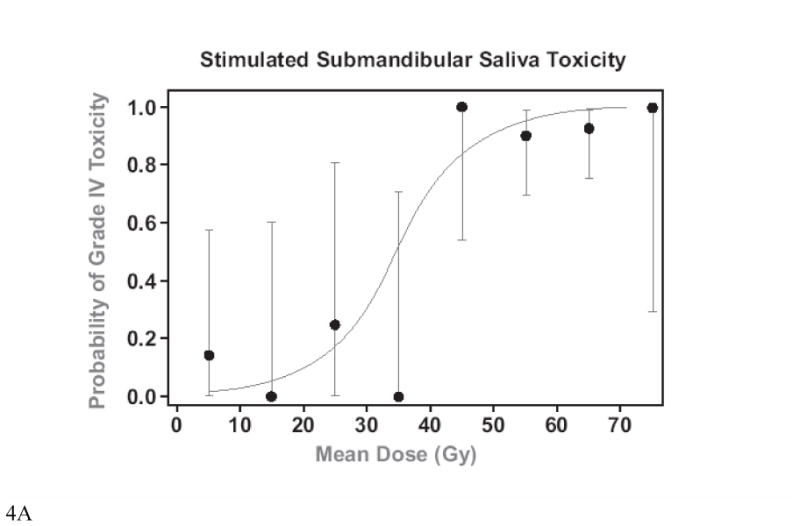

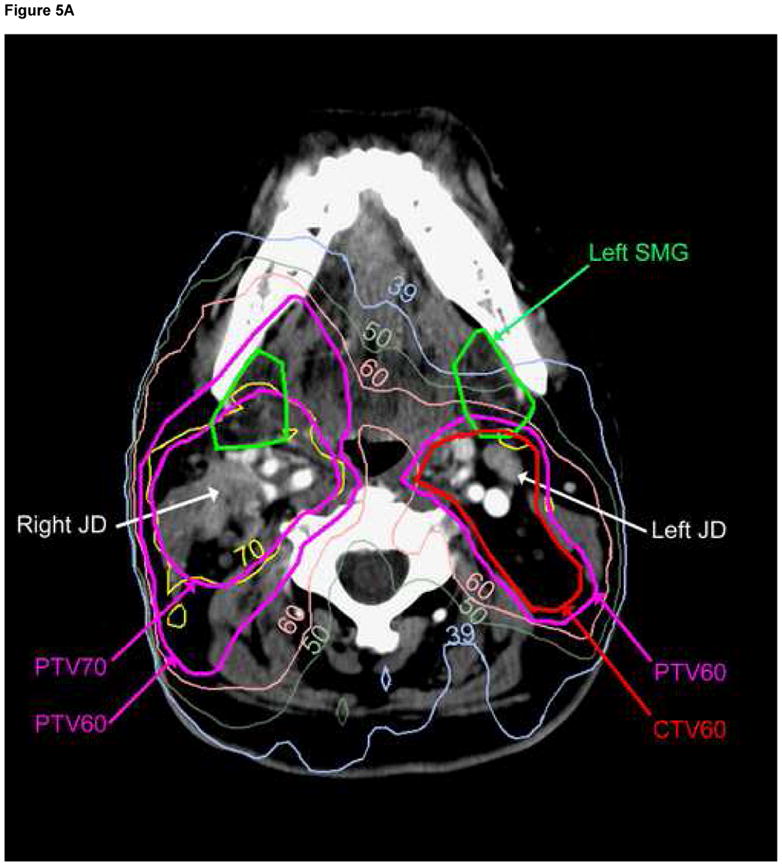

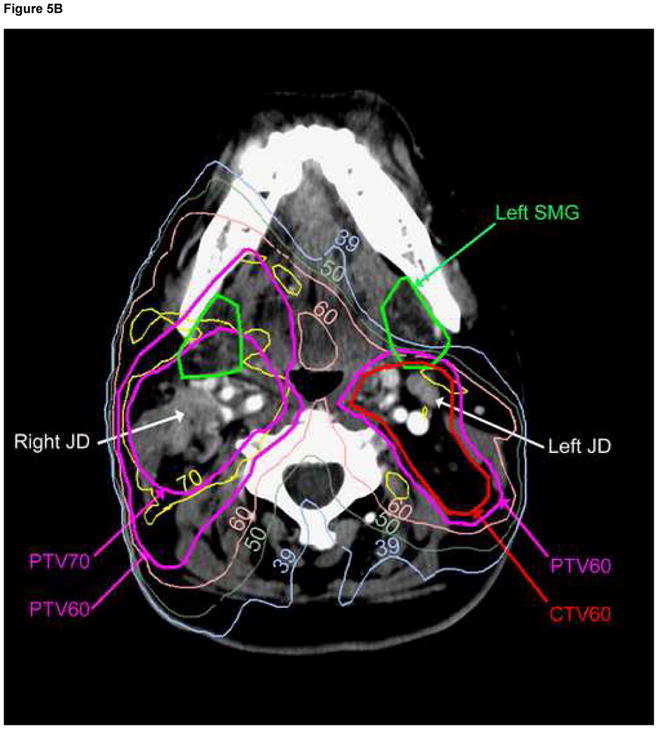

Plots of the mean doses vs. the probability of grade IV toxicity (post-RT SMG saliva flow rate/gland <25% of baseline) (32) at 12 months are presented in Figure 4. A comparison of IMRT cases whose optimization cost function did not include (Original Plans) or included (Re-Planning) the goal of reducing SMG mean dose to <39 Gy is provided in Table 3, and a comparison of the dose distributions for one of the cases is provided in Figure 5. The inclusion of the threshold SMG dose in the optimization cost function reduced the mean doses to the contralateral SMGs by 12 Gy on average. They were reduced to < 39 Gy in 4 of 7 patients whose contralateral SMG mean dose was above that dose level in the original plans, and reduced the dose even further in the single patient whose contralateral SMG mean dose was initially <39 Gy. In almost all patients, ipsilateral level IB was included in the targets, therefore mean ipsilateral SMG doses were only marginally reduced. The reduction in the contralateral SMG mean doses was achieved at the expense of modest increases (average increase of 2–3 Gy) in the mean doses to the parotid glands and the swallowing structures but not in the doses to the esophagus or oral cavity. Also, there were no differences between the original plans and re-planning in the minimal PTV doses, maximal spinal cord, or mandibular doses, whose cost function weights were higher than SMG sparing.

Fig. 4.

Mean SMG doses vs. grade IV toxicity at 12 months (salivary flow rate <25% of baseline pre-RT). A. Stimulated, B. Unstimulated. The dots are the average observed toxicities of patients grouped in mean dose clusters at 10 Gy intervals. The bars represent 95% C.I.

Table 3.

Comparison of mean organ doses (Gy) between the original IMRT plans and replanning with an additional cost function aiming to reduce mean SMG dose to <39 Gy. The doses include organ parts encompassed by the PTVs.

| Organ | Original Plan | Re-Plan | P* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Mean (SD) | Median | Range | Mean (SD) | Median | Range | ||

| Ipsilateral SMG | 68 (2) | 67 | 67–71 | 66 (1) | 66 | 64–68 | 0.02 |

| Contralateral SMG | 48 (8) | 47 | 37–59 | 36 (10) | 32 | 28–52 | <0.001 |

| Ipsilateral Parotid | 39 (9) | 40 | 30–52 | 42 (8) | 41 | 32–54 | 0.007 |

| Contralateral Parotid | 23 (6) | 25 | 14–30 | 25 (7) | 26 | 16–36 | 0.03 |

| Larynx¶ | 40 (6) | 42 | 27–48 | 42 (7) | 43 | 30–50 | 0.11 |

| Pharyngeal Constrictors | 56 (6) | 57 | 46–66 | 59 (5) | 60 | 51–66 | 0.008 |

| Esophagus | 12 (7) | 11 | 4–23 | 12 (7) | 11 | 5–23 | 0.20 |

| Oral Cavity | 48 (6) | 49 | 36–53 | 47 (6) | 49 | 35–53 | 0.44 |

Paired t-test comparing the means in original versus re-plan.

Glottic & Supraglottic Larynx

Fig. 5.

Comparison of dose distributions in the original plan (A), and re-planning (B) containing a cost function to reduce mean contralateral (Lt) SMG dose to<39 Gy. Note that the contralateral jugulodigastric (subdigastric, JD) lymph node lies immediately posterior to the contralateral SMG; no PTV under-dosage was therefore allowed while sparing the gland. The ipsilateral (Rt) JD node is involved with gross metastasis.

Discussion

This is the first study reporting dose-response relationships for the SMGs based on selective measurements of their output and their 3D dose distributions. Some earlier studies grouped these glands into few dose ranges, concluding that glands in high-dose groups had reduced function compared with glands in low-dose groups (33–34). The only study which detailed continuous dose-response relationships for a large number of patients was the study of Tsujii (35). They used 99mTc-pertechnetate scintigraphy to measure salivary glands function and reported an unexpected improvement in SMG function as the doses increased from 0 through 30 Gy, followed with a steep decline through 50 Gy. No evidence was found in our study for such an improvement in function as the dose increased. Modern studies assessing scintigraphic SMG function could not reach conclusions because almost all the glands received high doses (36–37). Saarilahti et correlated unstimulated whole mouth saliva measurements with SMG doses, assuming that these measurements are primarily of SMG origin (17). However, data from healthy individuals (13), as well as combining the pre-RT parotid gland output in HN cancer patients, reported previously (3), and the pre-RT SMG output reported in the current paper, demonstrate that only two thirds of the unstimulated major salivary gland output is provided by the SMGs. Furthermore, the relative flows from the various glands differ depending on the intensity of the stimulation (39). Thus, standardized and selective SMG measurements, as was done in the present study, are important for accurate estimations of their dose-response relationships.

Limitations of this study include a modest number of data point in the low SMG dose range. Also, the output of both SMGs together was measured in each patient. However, substantial number of patients had previous ipsilateral neck dissection that removed the ipsilateral SMG, and their output measurements were consistent with the model developed for all patients, increasing the robustness of the results.

The dose-response relationships for the SMGs were characterized by an exponential decrease of function vs. mean dose up to a threshold of 39 Gy, and SMG function increased over time if the mean dose was less than the threshold, similar to our previous findings for the parotid glands (3). The threshold for the SMGs is higher than the threshold we have previously reported for the parotid glands (26 Gy) in a study which included many of the patients who participated in the current study and which used similar statistical analysis methods (20). Also, the steepness of the dose-response curve for the SMG at doses below the threshold [(1.2%)Gy for the stimulated and (3%)Gy for the non-stimulated flow rates] is lower than the steepness reported for the parotid glands (7). Notwithstanding the wide range of reported mean parotid gland doses causing significant gland dysfunction (7, 20, 36, 39–40), the findings of the current study suggest that the SMGs are less sensitive to radiotherapy than the parotid glands.

A review of the literature for direct comparisons of parotid vs. SMG radiation sensitivity in humans supports a lesser sensitivity of the SMGs compared with the parotid glands ( 35, 41–43). Also, lower sensitivity of mucinous compard with serous cells was reported (44–45). These findings are compatible with the common symptoms of thick and sticky saliva during and shortly after the completion of RT, related to the faster decline in the watery content of the saliva produced by the serous parotid glands, compared with the decline of the mucinous component produced predominantly by the SMGs and the minor salivary glands.

In a previous study of dose-volume-effect relationships for the parotid glands we analyzed the correlations between fractional gland volumes receiving various doses and the mean doses, and concluded that they were highly correlated, therefore the mean dose was an adequate metric (20). Such an analysis was not performed in the current study assuming that the SMGs are similar in this regard to the parotid glands. However, the mean doses may not be the best measure of RT effect in the salivary glands. Substantial regional-anatomical differences in sensitivity to radiation were reported for the rat parotid glands, suggesting that the spatial dose distribution is important (46). Whether or not these results are relevant to the human salivary glands requires further research. Also, our results relate to the mean SMG doses calculated from the planning CT. A medial shift of the parotid glands during therapy in some patients may increase their mean doses compared with the treatment plans (47–48). No comparable data exists for the SMGs.

Our results showed no substantial differences between the dose-response relationships for the nominal mean doses or for the BED2s. The α/β ratio we have tested in this study (3 Gy) is characteristic of late effects in many organs. However, while the α/β ratio for early effects for the salivary glands is high (49), the ratio for late effects is disputed (50–51). Using a higher α/β ratio in our study would have reduced even further the differences between the BED2s and the nominal doses. A study in which most glands receive low fraction doses may clarify this issue.

The identification of a threshold dose of 39 Gy facilitated the assignment of a higher weight for SMG sparing in the re-optimization exercise, resulting in a substantial reduction of the mean doses to glands in the contralateral neck where level I was not included in the targets. The improvement in the doses to the non-involved SMGs was achieved at the expense of modest rise in the mean doses to some other neighboring structures like the parotid glands and the swallowing structures, while some other structures were not affected. It is possible that these dosimetric trade-offs will differ or even be reduced if different IMRT cost functions or techniques are used. However, these trade-offs are not likely to be completely eliminated. The best balance between the competing optimization goals requires further clinical investigation.

Lastly, we have not allowed under-dosage of the PTVs, neither in the actual treatment plans nor in the re-planning aiming to spare the SMGs. Saarilahti et al seem to have relaxed contralateral neck level II CTV doses in order to facilitate sparing of the SMGs (17, 52). The under-dosed part of level II would likely include the jugulodigastric (subdigastric, JD) lymph nodes, which lie immediately posterior to the SMGs in the anterior part of level II (Figure 5). The JD nodes have been described by Rouviere as the primary nodes draining the lymphatics from almost all HN mucosal sites, therefore they should be included as an essential part of the neck CTV, as previously detailed (53). Thus, when bilateral neck RT is indicated, partial sparing of the contralateral SMG should only be tried as long as the dose to the contralateral neck level II is not compromised.

In conclusion, selective SMG salivary flow rate measurements before and after RT have demonstrated an exponential reduction in salivary output as mean dose increased through a threshold of 39 Gy, improving gradually over the 2-year observation time period if the mean dose did not exceed the threshold. Incorporating this data facilitated substantial reduction of the SMG mean doses in some patients whose IMRT was re-planned, without compromising target doses. Reduced SMG doses resulted in modest trade-offs in the doses to some other organs. The clinical benefits associated with these trade-offs need to be assessed.

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIH K12 Award RR017607, NIH grant PO1-CA59827, and the Duke Family Head and Neck Research Fund.

Footnotes

Presented at the 49th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology (ASTRO), Oct. 27–30, Los Angeles, CA.

Conflict of Interest: None

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Bjordal K, Kaas S. Psychometric validation of the EORTC core quality of life questionnaire. Acta Oncol. 1992;31:311–321. doi: 10.3109/02841869209108178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eisbruch A. Reducing xerostomia by IMRT: What may, and may not, be achieved. J Clin Oncol. 2007:4863–4. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.4874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eisbruch A, Kim HM, Terrell JE, et al. Xerostomia and its predictors following parotid-sparing irradiation of head and neck cancer. Int J Rad Onc Biol Phys. 2001;50:695–704. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(01)01512-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meirovitz A, Murdoch-Kinch CA, Scipper M, et al. Grading xerostomia by physicians or by patients after IMRT. Int J Rad Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;66:445–453. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jensen K, Jensen AB, Grau C. The relationship between observer-based and patient assessed symptom severity after treatment for head and neck cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2006;78:298–305. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2006.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pow EH, Kwong DL, McMillan AS, et al. Xerostomia and quality of life after intensity modulated or conventional radiotherapy: randomized study. IJROBP. 2006;66:981–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blanco AI, Chao KSC, El Naqa I, et al. Dose-volume modeling of salivary function in patients with head and neck cancer receiving radiotherapy. Int J Rad Onc Biol Phys. 2005;62:1055–1069. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.12.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parliament MB, Scrimger RA, Anderson SG, et al. Preservation of oral health-related quality of life and salivary flow rates after IMRT. Int J Rad onc Biol Phys. 2004;58:663–673. doi: 10.1016/S0360-3016(03)01571-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brizel DM, Wasserman TH, Henke M, et al. Phase III randomized trial of amifostine in head and neck cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:3339–3345. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.19.3339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fox PC, Busch KA, Baum BJ. Subjective reports of xerostomia and objective measures of salivary gland performance. J Am Dent Assoc. 1987;115:581–584. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8177(87)54012-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Franzen L, Funegard U, Ericson T, Henriksson R. Parotid gland function during and following radiotherapy. Eur J Cancer. 1992;28:457–462. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(05)80076-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kam MK, Leung SF, Zee B, et al. Prospective randomized study of IMRT on salivary gland function in early-stage nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4873–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.5501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ship JA, Fox PC, Baum BJ. How much saliva is enough? J Am Dent Assoc. 1991;122:63–69. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1991.0098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tabak LA. In defense of the oral cavity: salivary mucins. Annual Rev Physiol. 1995;57:547–564. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.57.030195.002555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Milne RW, Dawes C. The relative contributions of different salivary glands to the blood group activity of whole saliva. Vox Sang. 1973;25:298–307. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.1973.tb04377.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jellema AP, Doornaert P, Slotman B, et al. Does radiation dose to the salivary glands and oral cavity predict patient-rated xerostomia? Radiother Oncol. 2005;77:164–171. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saarilanti K, Kouri M, Collan J, et al. Sparing of the submandibular glands by IMRT in head and neck cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2006;78:270–275. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2006.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seikaly H, Jha N, Harris JR, et al. Long-term outcomes of submandibular gland transfer for prevention of postradiation xerostomia. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130:956–961. doi: 10.1001/archotol.130.8.956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feng FY, Kim HM, Lyden TH, et al. IMRT of head and neck cancer aiming to reduce dysphagia: early dose-effect relationships for the swallowing structures. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;68:1289–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.02.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eisbruch A, Ten Haken RK, Kim HM, et al. Dose, volume, and function relationships in parotid salivary glands following conformal and intensity-modulated irradiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1999;45:577–87. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(99)00247-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin A, Kim HM, Terrell JE, et al. Quality of life after parotid-sparing IMRT for head and neck cancer. Int J Rad Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;57:61–70. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(03)00361-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Malouf JG, Aragon C, Henson BS, et al. Influence of parotid-sparing radiotherapy on xerostomia. Cancer Detection Prevention. 2003;27:305–310. doi: 10.1016/s0361-090x(03)00095-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jabbari S, Kim HM, Feng M, et al. Matched case-control study of quality of life and xerostomia after IMRT. Int J Rad Onc Biol Phys. 2005;63:725–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.02.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eisbruch A, Ship JA, Martel MK, et al. Parotid gland sparing in patients undergoing bilateral head and neck irradiation: techniques and early results. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1996;36:469–80. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(96)00264-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eisbruch A, Marsh LH, Martel MK, et al. Comprehensive irradiation of head and neck cancer using conformal multisegmental fields. Int J Rad Oncol Biol Phys. 1998;41(3):559–68. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(98)00082-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vineberg KA, Eisbruch A, Coselmon MN, et al. Is uniform target dose possible in IMRT? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;52:1159–72. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(01)02800-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lavelle CLB. Applied oral physiology. 2. Boston: Wright; 1988. pp. 128–41. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fox P, van derv en BC, Sonis JM, et al. Xerostomia: evaluation of a symptom with increasing significance. J Am Dent assoc. 1985;10:519–525. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1985.0384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bentzen SM, Overgaard J. Clinical normal-tissue radiobiology. In: Tobias JS, Thomas PRM, editors. Current Radiation Oncology. Vol. 2. London: Arnold; 1995. pp. 37–67. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chapell R. Fitting bent lines to data, with application to allometry. J Theor Biol. 1989;138:235–256. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5193(89)80141-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liang KY, Zeger SL. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrica. 1986;73:13–22. [Google Scholar]

- 32.LENT SOMA Tables. Radiother Oncol. 1995;35:17–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Valdes Olmos RA, Keus RB, Takes RP, et al. Scintigraphic assessment of salivary function. Cancer. 1994;73:2886–93. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19940615)73:12<2886::aid-cncr2820731203>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Valdez IH, Atkinson JC, Ship JA, Fox PC. Major salivary gland function in patients with radiation-induced xerostomia. Int J Rad Onc Biol Phys. 1993;25:41–7. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(93)90143-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tsujii H. Quantitative dose-response analysis of salivary function following radiotherapy using sequential RI-sialography. Int J Rad Onc Biol Phys. 1985;11:1603–12. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(85)90212-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Munter MW, Hoffner S, Hof H, et al. Changes in salivary gland function after radiotherapy. Int J Rad Onc Biol Phys. 2007;67:651–659. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu WS, Kuo HC, Lin JC, et al. Assessment of salivary function change in nasopharyngeal carcinoma treated by parotid-sparing radiotherapy. Cancer J. 2006;12:494–500. doi: 10.1097/00130404-200611000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dawes C, Jenkins GN. The effects of different stimuli on the composition of saliva. J Physiol (London) 1964;170:86–100. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1964.sp007315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roesink JM, Moerland MA, Batterman JJ, et al. Quantitative dose volume response analysis in parotid gland after radiotherapy. Int J Rad Onc Biol Phys. 2001;51:938–946. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(01)01717-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bussels B, Maes A, Flamen P, et al. Dose-response relationships within the parotid glands after radiotherapy. Radiother Oncol. 2004;73:297–306. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2004.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bagesund M, Richter S, Ringden O, Dahllof G. Longitudinal scintigraphic study of parotid and submandibular gland function after total body irradiation. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2007;17:34–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2006.00786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Malpani BL, Samuel AM, Ray S, et al. Differential kinetics of parotid and submandibular gland function as demonstrated by scintigraphic means. Nucl Med Commun. 1995;16:706–9. doi: 10.1097/00006231-199508000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Raza H, Khan AU, Hameed A, Khan A. Quantitative evaluation of salivary gland dysfunction after radioiodine therapy using salivary gland scintigraphy. Nucl Med Commun. 2006;27:495–9. doi: 10.1097/00006231-200606000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kashima HK, Kirkman WR, Andrews JR. Postradiation sialadenitis: a study following irradiation of human salivary glands. Am J Roentgenol. 1965;94:271–91. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stephens LC, King GK, Peters LJ, et al. Acute and late radiation injury in rhesus parotid glands. Am J Pathol. 1986;124:469–78. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Konings AWT, Cotteleer F, Faber H, et al. Volume effects and region-dependent radiosensitivity of the parotid gland. Int J Rad Onc Biol Phys. 2005;62:1090–1095. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barker JL, Garden AS, Ang KK, et al. Quantification of volumetric and geometric changes during fractionated radiotherapy. Int J Rad Onc Biol Phys. 2004;59:960–970. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2003.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Robar JL, Day A, Clancey J, et al. Spatial and dosimetric variability of organs at risk in head and neck IMRT. Int J Rad Onc Biol Phys. 2007;68:1121–1130. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Franzen L, Sundstrom S, Karlsson M, et al. Fractionated irradiation and early changes in rat parotids. Acta Oncol. 1992;31:359–364. doi: 10.3109/02841869209108186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Leslie MD, Dische S. The early changes in salivary gland function during and after radiotherapy for head neck cancer. Radiother Oncol. 1994;30:26–32. doi: 10.1016/0167-8140(94)90006-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Price RE, Ang KK, Stephens LC, et al. Effects of continuous hyperfractionated accelerated and conventionall RT on salivary glands of rhesus monkeys. Radiother Oncol. 1995;34:39–46. doi: 10.1016/0167-8140(94)01491-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Saibishkumar EP, Jha N. Sparing submandibular gland by IMRT. Radiother Oncol. 2006;80:106. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2006.06.006. (Letter) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Eisbruch A, Marsh LH, Dawson LA, et al. Recurrences near base of skull after IMRT for head-neck cancer: implications for target delineation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;59:28–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2003.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]