Abstract

Polyether ionophores represent a large group of natural, biologically active substances produced by Streptomyces spp. They are lipid soluble and able to transport metal cations across cell membranes. Several of polyether ionophores are widely used as growth promoters in veterinary. Polyether antibiotics show a broad spectrum of bioactivity ranging from antibacterial, antifungal, antiparasitic, antiviral, and tumour cell cytotoxicity. Recently, it has been shown that some of these compounds are able to selectively kill cancer stem cells and multidrug-resistant cancer cells. Thus, they are recognized as new potential anticancer drugs. The biological activity of polyether ionophores is strictly connected with their molecular structure; therefore, the purpose of this paper is to present an overview of their formula, molecular structure, and properties.

1. Introduction

Polyether ionophores are very large and important group of naturally occurring compounds. Increased interest in this type of compound has been observed in recent years. There are over 120 naturally occurring ionophores known [1]. Major commercial use of the ionophores is to control coccidiosis. They are also used as growth promoters in ruminants. These compounds specifically target the ruminal bacterial population increasing production efficiency. In 2003, the antimicrobials most commonly used in beef cattle production were ionophores. Lasalocid (Avatec, Bovatec), monensin (Coban, Rumensin, and Coxidin), salinomycin (Bio-cox, Sacox), narasin (Monteban, Maxiban), maduramycin (Cygro), and laidlomycin propionate (Cattlyst) were the ionophores of combined yearly sales of more than $150 million [2]. Ionophores can also be used in the production of ion-selective electrodes [3, 4].

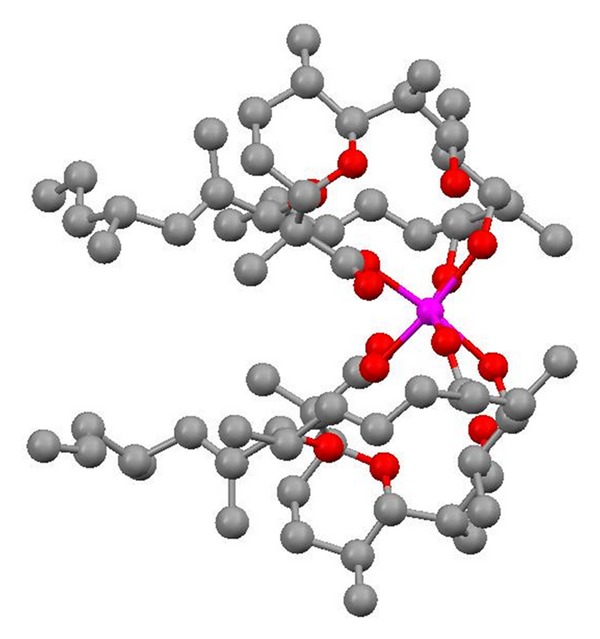

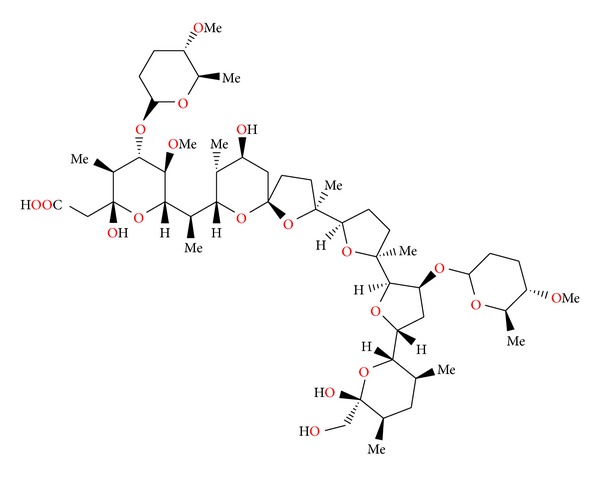

All applications of ionophores mentioned above are closely related to their ability to form complexes with metal cations (host-guest complexes) and transport these complexes across lipid bilayers and cell membranes. According to the results of X-ray studies, the metal cation sites in a cage formed by oxygen atoms of the ionophore. The polyether antibiotics form neutral complexes with monovalent cations (i.e., monensin, salinomycin) or divalent metal cations (i.e., lasalocid, calcimycin) as well as with organic bases (i.e., lasalocid). The neutral complexes with cations are formed more preferably than charged complexes because the carboxylic group is deprotonated at physiological pH. However, recently it has been shown that polyether ionophores can also act as neutral ionophores and transport cations as charged complexes. Typically, the complexation of the cation is connected with formation of a pseudocyclic structure which is stabilized by intramolecular hydrogen bonds formed between the carboxylic group and the hydroxyl groups. The ring of ionophore molecule is wrapped around this hydrophilic cage rendering the whole complex lipophilic. The mechanism of transport of a cation by polyether ionophores is attributed to their ability to exchange protons and cations in an electroneutral process. In this type of transport of the cations (M+), the polyether ionophore anion (I–COO−) binds the metal cation or proton (H+) to give a neutral salt (I–COO−M+) or a neutral polyether ionophore in acidic form (I–COOH), respectively, and only uncharged molecules containing either the metal cation or proton can move through the cell membrane. The whole process leads to changes in Na+/K+ gradient and to an increase in the osmotic pressure inside the cell, causing swelling and vacuolization, and finally death of the bacteria cell. The remarkable selectivity of some ionophores is attributed to the size of the cage. Only cations with an appropriate radius fit the cavity perfectly, larger ones have to deform it, while smaller ones find a nonoptimal coordination geometry [5–10].

Ionophores are most effective against Gram-positive bacteria. The cell of these bacteria is surrounded by the peptidoglycan layer which is porous and allows small molecules to pass through, reaching the cytoplasmic membrane, where the lipophilic ionophore rapidly dissolves into the membrane. Conversely, Gram-negative bacteria are separated from the environment and antimicrobial agents by a lipopolsaccharide layer, outer membrane, and periplasmic space [2]. Escherichia coli, Gram-negative bacteria of significant importance to food safety and human health, is insensitive to ionophore addition, unless the outer membrane is removed [11].

In this paper, we present structure and properties of several naturally occurring polyether antibiotics.

The molecular structures of polyether ionophores presented below are visualized using X-ray data deposited in Cambridge Structural Database.

2. Structures and Biological Properties of Several Ionophores

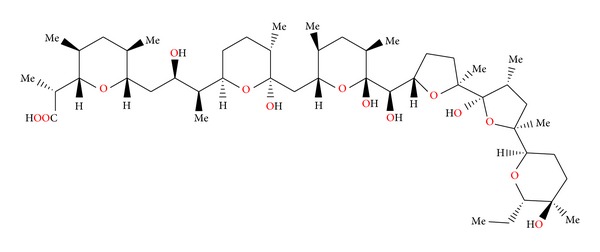

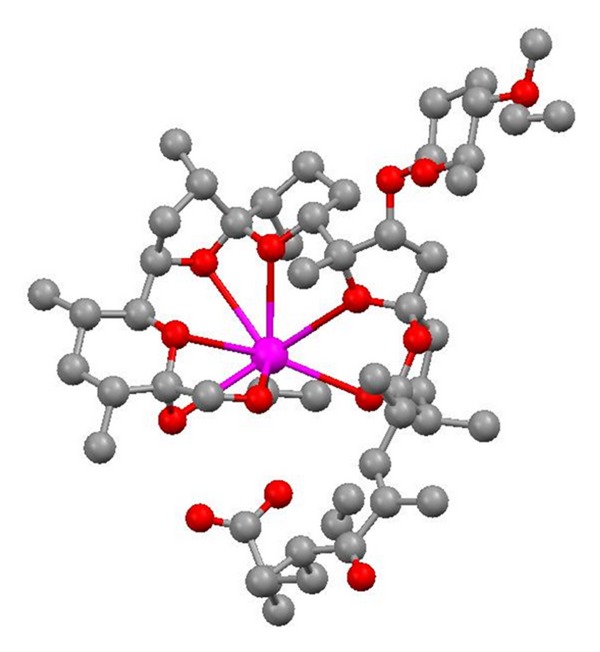

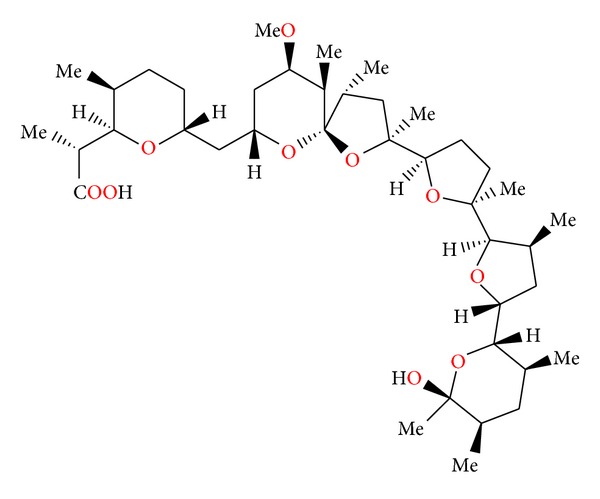

2.1. Alborixin

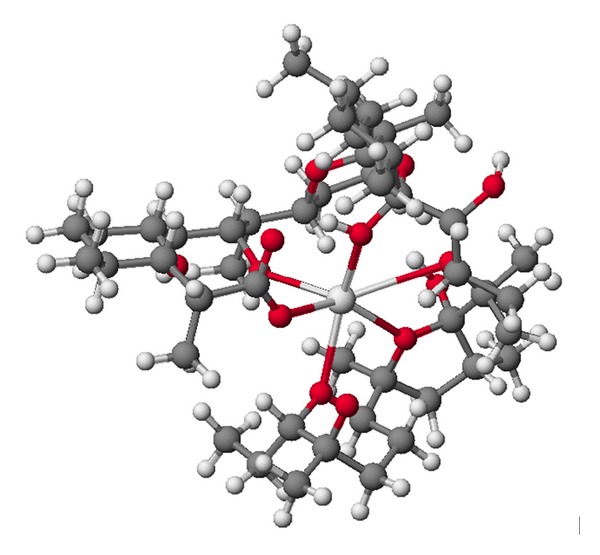

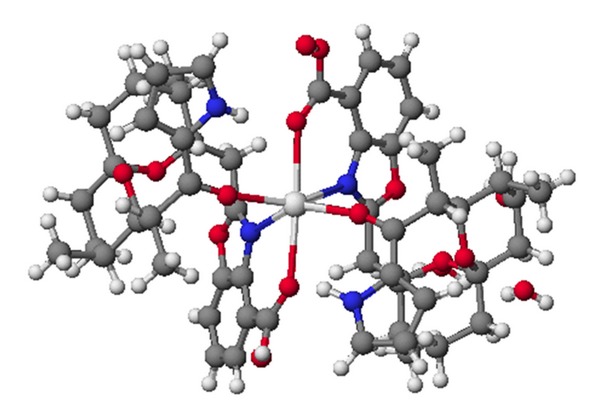

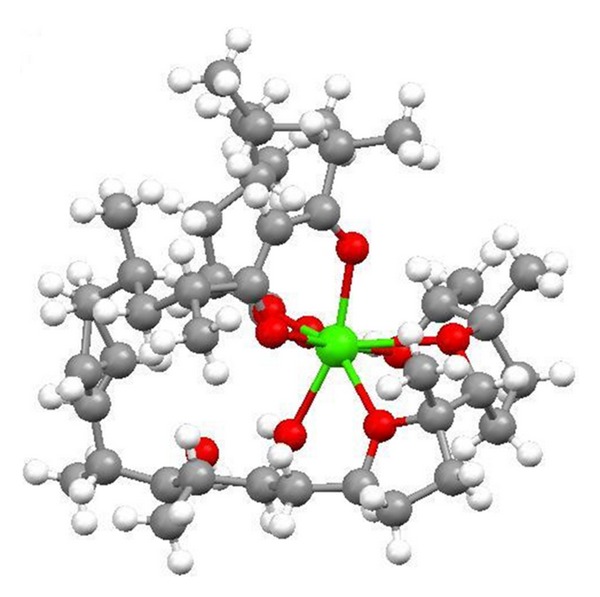

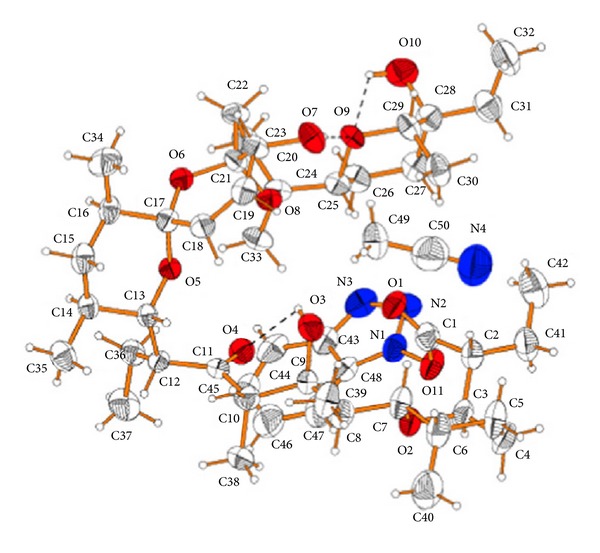

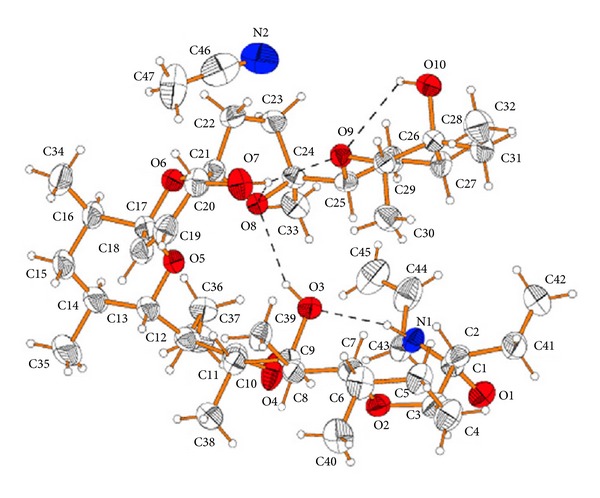

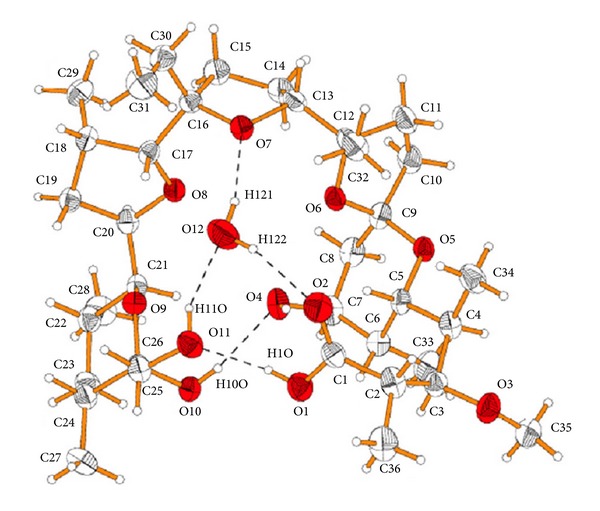

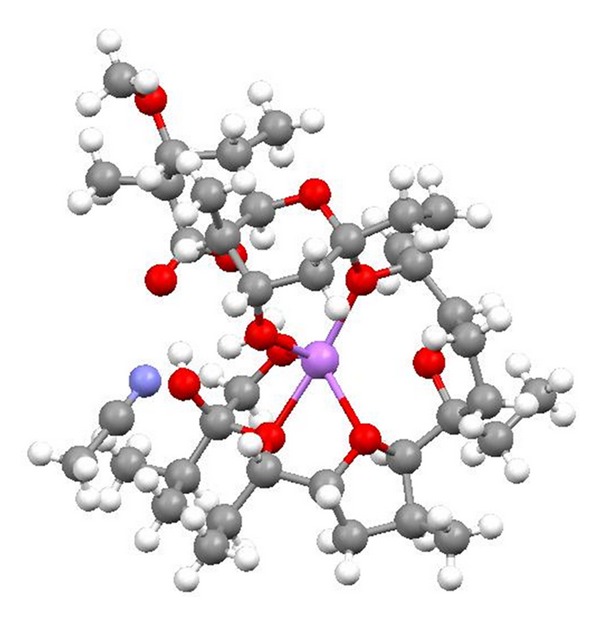

Alborixin (Figure 1) was first isolated from fermenting a fermentation of Streptomyces hygroscopicus [12]. Its structure was determined by X-ray analysis of its potassium salt [13]. A crystal structure of 6-demethyl-alborixin complex with sodium cation (Figure 2) has also been reported [14]. Alborixin is active against Gram-positive bacteria. The value of LD50 of alborixin determined in mice subcutaneously is 150 mg/kg [15].

Figure 1.

Structure of alborixine.

Figure 2.

Structure of 6-demethyl-alborixin complex with sodium cation.

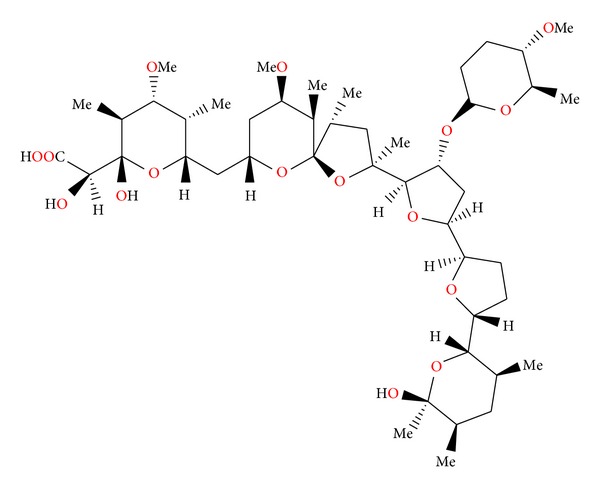

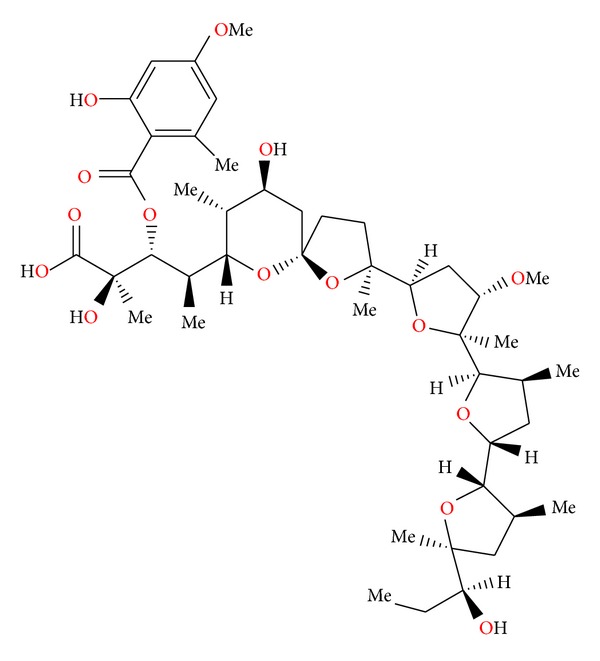

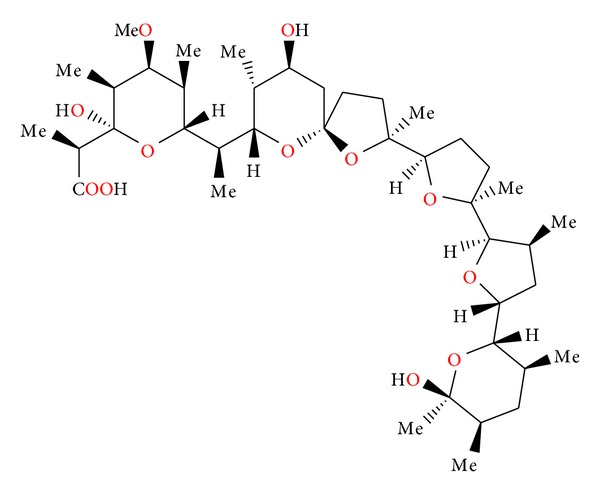

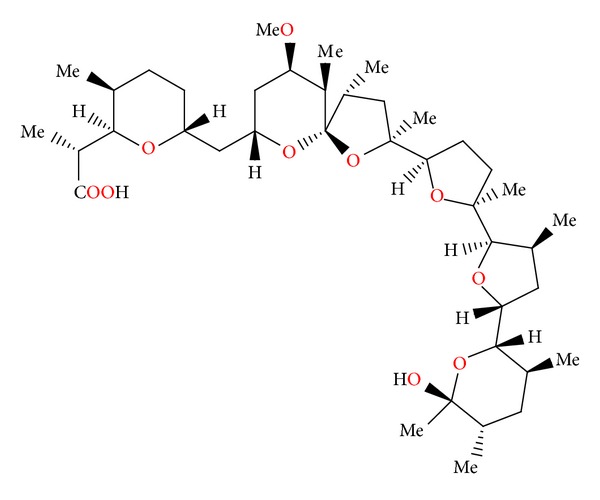

2.2. Antibiotic 6016

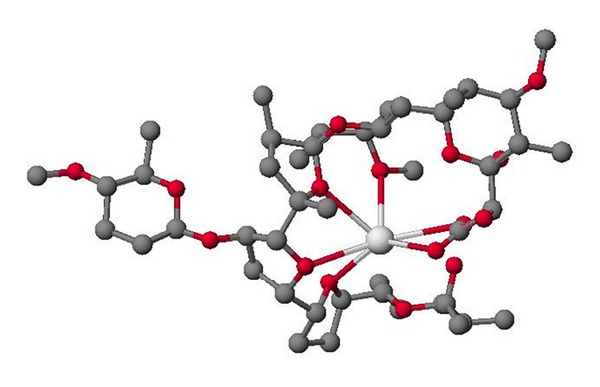

Antibiotic 6016 (Figure 3) was first isolated from the culture of Streptomyces albus strain No. 6016 [16]. Molecular structure (Figure 4) was determined by X-ray analysis of its thalium salt [17]. Antibiotic 6016 is active against Gram-positive bacteria including mycobacteria. No activity was observed against Gram-negative bacteria and fungi. The toxicity of antibiotic 6016 in mice was also examined. The LD50 is 23 mg/kg intraperitoneally and 63 mg/kg orally. The anticoccidial evaluation of antibiotic 6016 was carried out on chickens infected with Eimeria tenella oocyst. It was effective in reducing mortality of chickens and increasing average body weight of treated infected chickens compared to untreated infected controls [16].

Figure 3.

Structure of antibiotic 6016.

Figure 4.

Crystal structure of antibiotic 6016 thallium salt.

2.3. Calcimycin, Cezomycin, and X-14885A

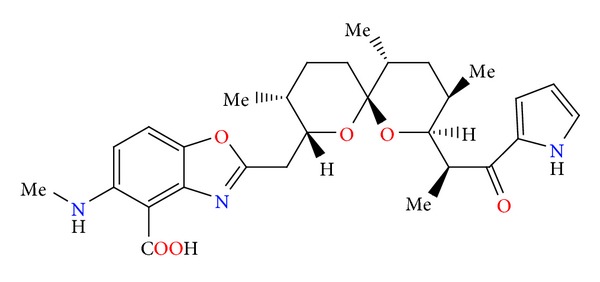

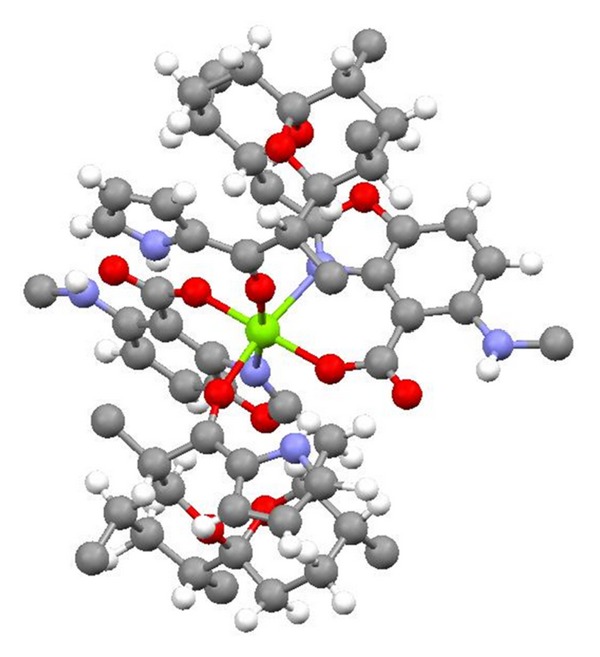

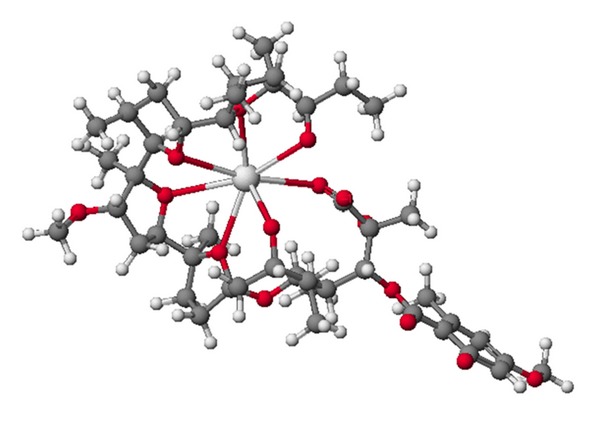

Calcimycin (Figure 5) was first isolated from a fermentation of Streptomyces chartreuses [18]. This antibiotic is able to bind divalent cations with a preference for the complexation of calcium cation [19]. Complexes of calcimycin with Mg2+, Ni2+, and Zn2+ cations on 2 : 1 stoichiometry are also described [20–22]. Structure of complex with Mg2+ is presented in Figure 6.

Figure 5.

Structure of calcimycin.

Figure 6.

Crystal structure of 2 : 1 complex of calcimycin with the magnesium cation.

By equilibrating calcium ion across the inner membrane of mitochondria, calcimycin can uncouple oxidative phosphorylation. Various biological processes which require the presence of a calcium ion, such as thyroid secretion and insulin release, have been stimulated using this ionophore [23, 24]. Because of the fluorescent properties of calcimycin, it has been used also as a probe for divalent cations in artificial and biological membranes and to determine the mode of action of ionophore-mediated divalent cation transport [25].

Calcimycin is an efficient antibiotic against Gram-positive bacteria and inactive towards Gram-negative species. This difference in activity is attributed to the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria which is presumably impermeable to these highly hydrophobic compounds [26].

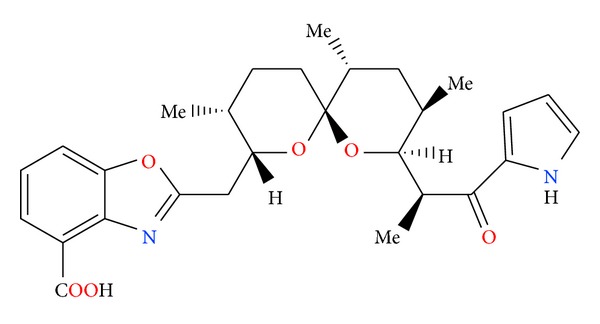

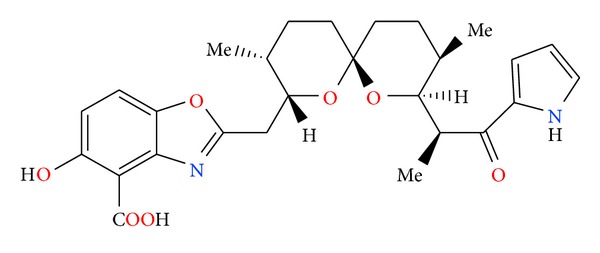

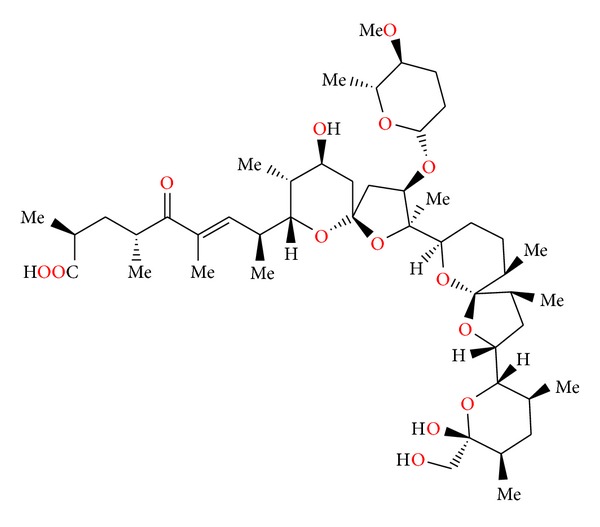

There are two compounds structurally related to calcimycin: cezomycin (Figure 7) also known as demethyloamino-calcimycin and X-14885A (Figure 8), which has one methyl group less on the spiroketal and a hydroxyl group instead of a methyloamino group present in calcimycin. Both compounds are isolated from the same strain as calcimycin. The crystal structure of cezomycin (Figure 9) was determined as its 11-demethyl complex with the sodium cation of the stoichiometry 2 : 1 [27].

Figure 7.

Structure of cezomycin.

Figure 8.

Structure of X-14885A.

Figure 9.

Crystal structure of 2 : 1 complex of 11-demethyl-cezomycin complex with the sodium cation.

Antibiotic X-14885A exhibits in vitro activity at concentrations less than 1 μg/mL against such Gram-positive bacteria as Staphylococcus aureus and Bacillus subtilis and the spirochete responsible for swine dysentery Treponema hyodysenteriae [28].

2.4. Cationomycin

Cationomycin (Figure 10) is an ionophore isolated from Actinomadura azurea. Crystal structure of cationomycin (Figure 11) was determined by X-ray analysis of its thallium salt [29]. Cationomycin contains an unusual aromatic side fragment, which is important for biological activity. When this chain is removed, the activity of cationomycin is reduced. A large group of derivatives was prepared after deacylation, but only anisyl analogue was more active than cationomycin [30, 31].

Figure 10.

Structure of cationomycin.

Figure 11.

Crystal structure of cationomycin thallium salt.

Kinetic studies showed that cationomycin transported the potassium cation more rapidly than the sodium cation, and the more stable complex was formed with potassium at the water/membrane interface [32].

2.5. Endusamycin

Endusamycin (Figure 12) was isolated from Streptomyces endus. The crystal structure (Figure 13) was determined by X-ray analysis of its rubidium salt [33].

Figure 12.

Structure of endusamycin.

Figure 13.

Crystal structure of endusamycin rubidium salt.

Endusamycin has a good spectrum of activity against Gram-positive bacteria and good activity against many anaerobes and organisms such as Treponema hyodysenteriae. Endusamycin was active against Eimeria tenella and Eimeria acervulina coccidia when administrated in feed from 10 to 40 μg/g. Chickens were protected from lesions but showed poor weight gains and feed intake. Endusamycin has LD50 of 7.5 mg/kg orally in male rats [33].

Endusamycin also induced a change in the proportion of volatile fatty acids (acetate, propionate, and butyrate) produced in the rumen by increasing the molar proportion of propionate in the rumen fluids [33].

2.6. Mutalomycin

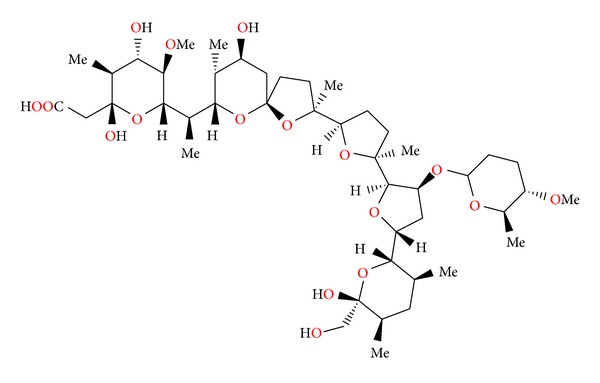

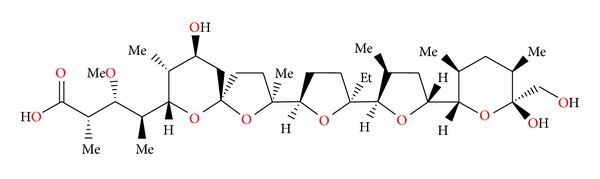

Mutalomycin (Figure 14) was first isolated from a strain of Streptomyces mutabilis [34]. Crystal structure of its epimer, 28-epimutalomycin potassium salt (Figure 15), was reported [35].

Figure 14.

Structure of mutalomycin.

Figure 15.

Crystal structure of 28-epimutalomycin potassium salt.

Mutalomycin possesses antibiotic activity against Gram-positive bacteria and also exhibits an anticoccidial activity in chickens similar to other polyether antibiotics. It is effective in reducing mortality and in increasing the average body weight of chickens infected with Eimeria tenella and other Eimeria species [34].

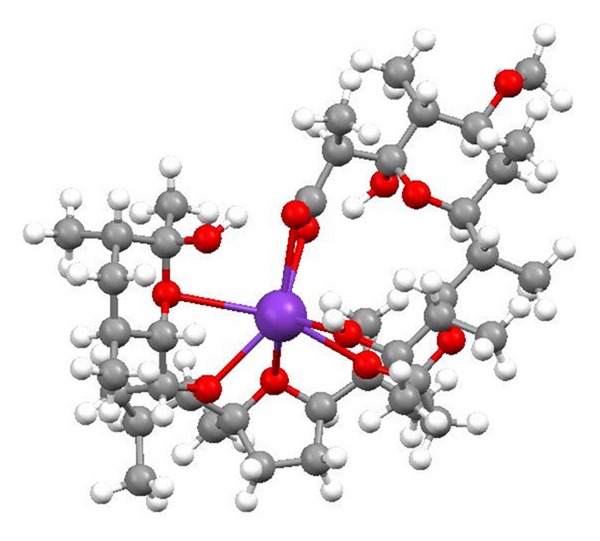

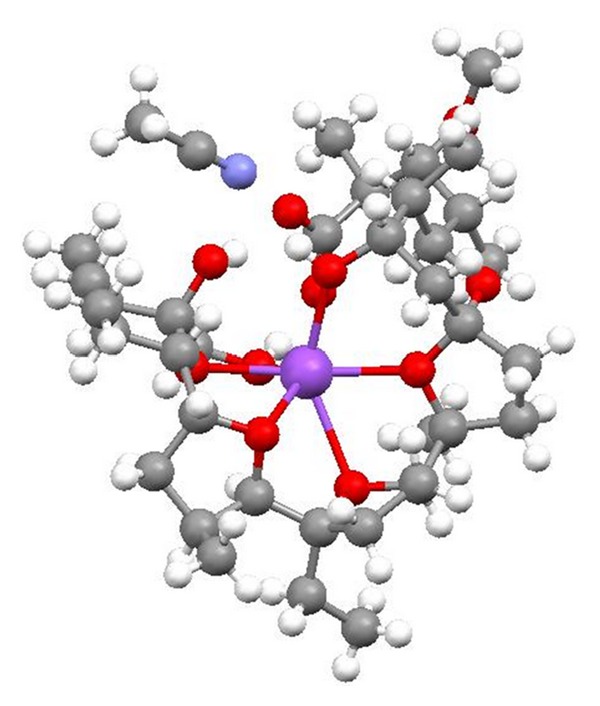

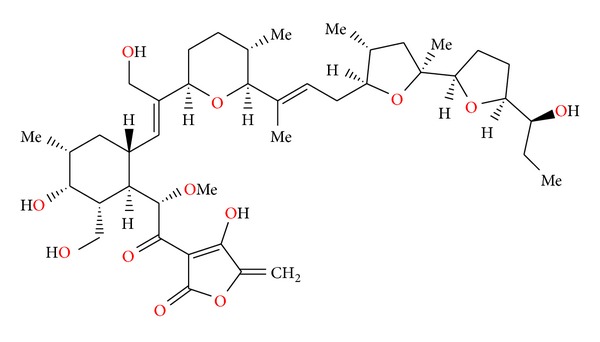

2.7. Ionomycin

Ionomycin (Figure 16) was first isolated from Streptomyces conglobatus [36]. Crystal structure of its complex with the calcium cation (Figure 17) was reported [37].

Figure 16.

Structure of ionomycin.

Figure 17.

Crystal structure of ionomycin complex with the calcium cation.

Ionomycin is capable of extracting calcium ion from the aqueous phase into an organic phase. This antibiotic also acts as a mobile ion carrier transporting the cation across a solvent barrier. The divalent cation selectivity order for ionomycin as determined by ion competition experiments was found to be Ca2+ > Mg2+≫ Sr2+ = Ba2+, where the binding of strontium and barium by the antibiotic is insignificant [36].

Ionomycin, like other polyether antibiotics, is active primarily against Gram-positive bacteria with no demonstrable activity against Gram-negative bacteria. The acute toxicity of ionomycin, LD50, administered subcutaneously to mice is 28 mg/kg [38].

2.8. K-41

K-41 (Figure 18) was first isolated from Streptomyces hygroscopicus [39]. The molecular structure of this antibiotic was established by X-ray analysis of the sodium salt of its p-bromobenzoate [40].

Figure 18.

Structure of K-41.

K-41 is active against Gram-positive bacteria [40]. K-41 showed also antimalarial activity against the drug-resistant strain of Plasmodium falciparum and was more potent than clinically used antimalarial drugs: artemisinin, chloroquine, and pyrimethamine [41].

2.9. Kijimicin

Kijimicin (Figure 19) was found in the culture filtrate of an Actinomadura sp. MI215-NF3. Its crystal structure (Figure 20) was established by X-ray analysis of its rubidium salt [42].

Figure 19.

Structure of kijimicin.

Figure 20.

Crystal structure of kijimicin rubidium salt.

Kijimicin inhibits mainly the growth of Gram-positive bacteria and shows activity against Eimeria tenella. The acute toxicity of the antibiotic in mice is 56 mg/kg [43]. Kijimicin was also examined for its HIV inhibitory activity, was proved to inhibit HIV replication in both T-cell and monocyte lineage cell lines, and was shown to be active in in vitro assays against both acute and chronic infections [43].

2.10. Lasalocid A and Its Analogues

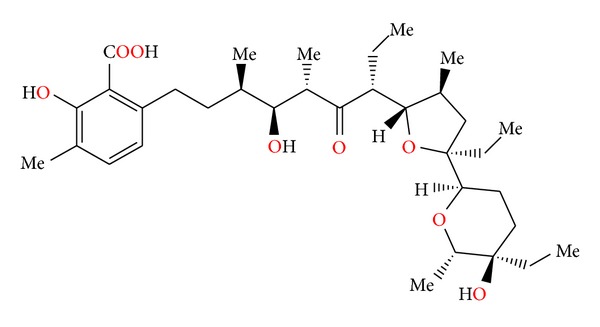

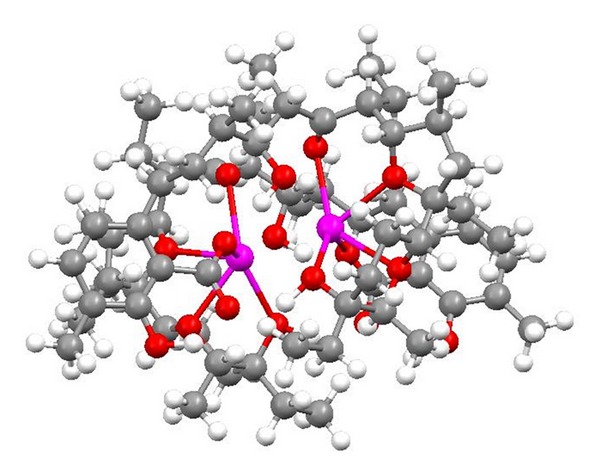

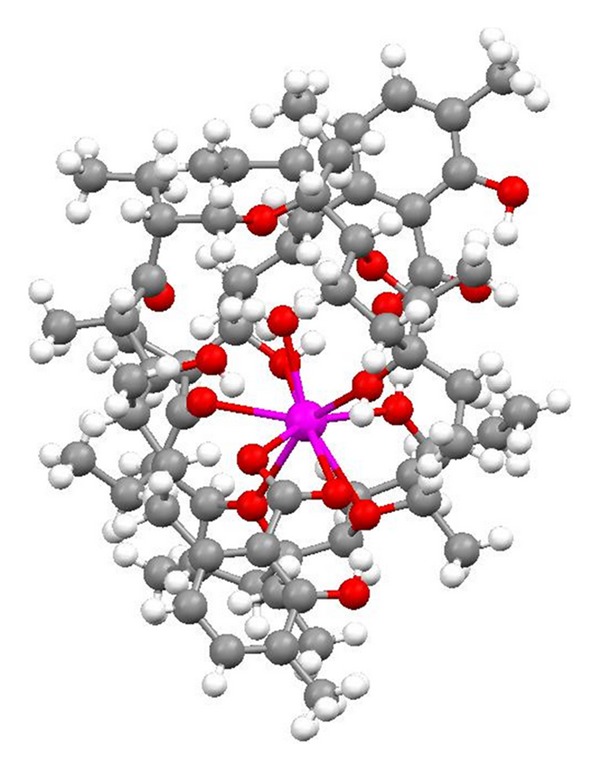

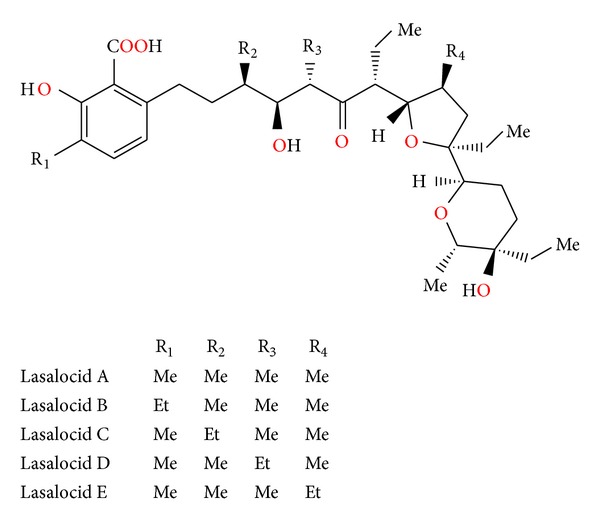

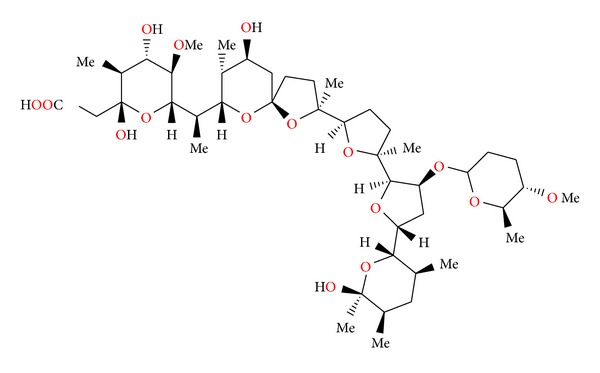

Lasalocid (Figure 21) was first isolated from Streptomyces lasaliensis [44]. Crystal structures of lasalocid acid barium, silver (Figure 22), and strontium (Figure 23) salts were determined [45, 46]. Monomeric unit of Lasalocid thallium salt is stabilized by strong intramolecular aryl-Tl type-metal half sandwich bonding interactions [47]. Homologs of lasalocid (Figure 24) acid were also described [48].

Figure 21.

Structure of lasalocid.

Figure 22.

Crystal structure of lasalocid silver salt on 2 : 2 stoichiometry.

Figure 23.

Crystal structure of 2 : 1 complex of lasalocid with the strontium cation.

Figure 24.

Lasalocid acid analogues.

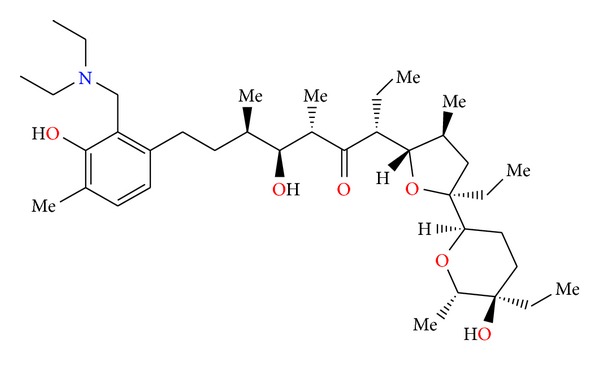

Chemistry of lasalocid was extensively investigated. Treatment of the free acid with diethylamine and paraformaldehyde in toluene, employing Dean—Stark conditions, gave the Mannich base (Figure 25) [49]. Four ester derivatives of lasalocid were obtained (Figure 26), and their crystal structures (Figures 27 and 28) were also reported [50–53].

Figure 25.

Structure of lasalocid acid Mannich base.

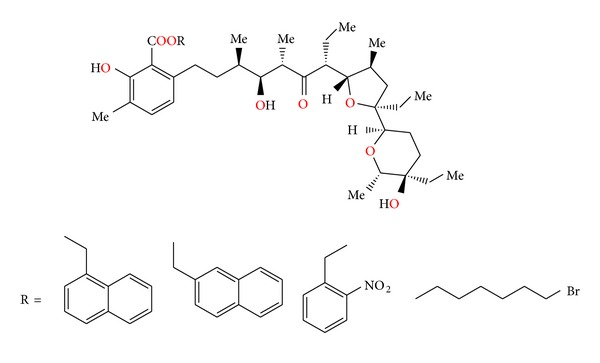

Figure 26.

Structures of lasalocid acid esters.

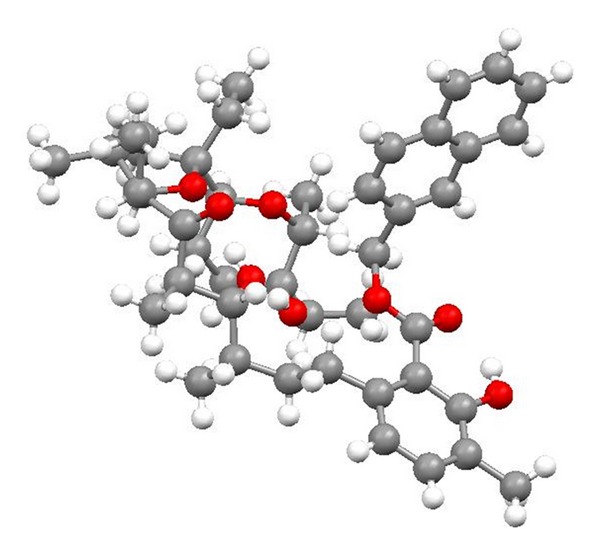

Figure 27.

Structure of lasalocid 2-naphthylmethyl ester.

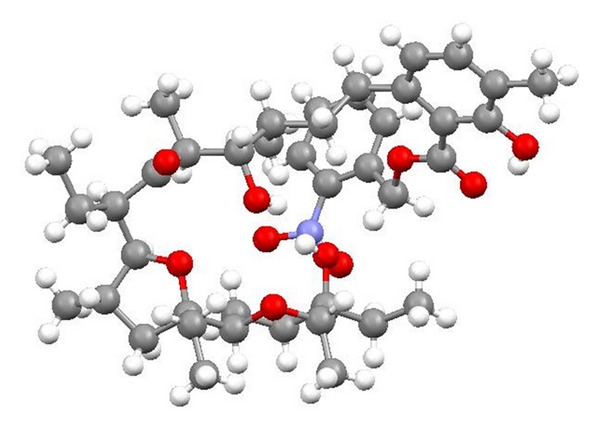

Figure 28.

Crystal structure of lasalocid orthonitrobenzyl ester.

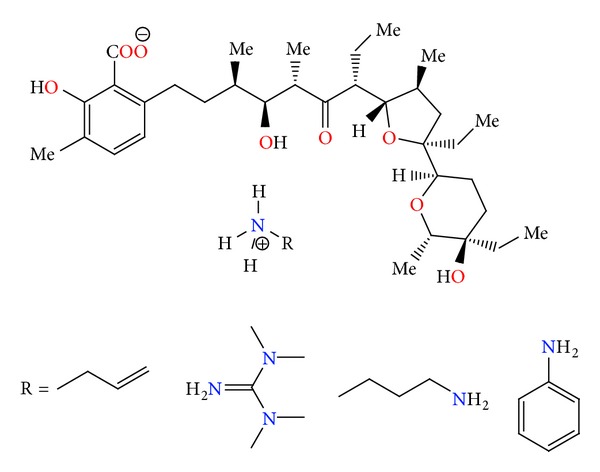

Lasalocid is able to form complexes with amines and its several complexes have been obtained (e.g., with allylamine, 1,1,3,3-tetramethylguanidine, TBD, phenylamine, and N-butylamine) (Figure 29), and their crystal structures (Figures 30 and 31) were reported. Lasalocid is active against Gram-positive bacteria. Complex of lasalocid acid with allylamine is even more active than pure lasalocid acid. Lasalocid sodium salt (Bovatec, Avate) is used in a veterinary to prevent coccidiosis in poultry and to improve nutrient absorption and feed efficiency in ruminants [54–57].

Figure 29.

Lasalocid acid complexes with several amines: allylamine, 1,1,3,3-tetramethylguanidine, N-butylamine, and phenylamine.

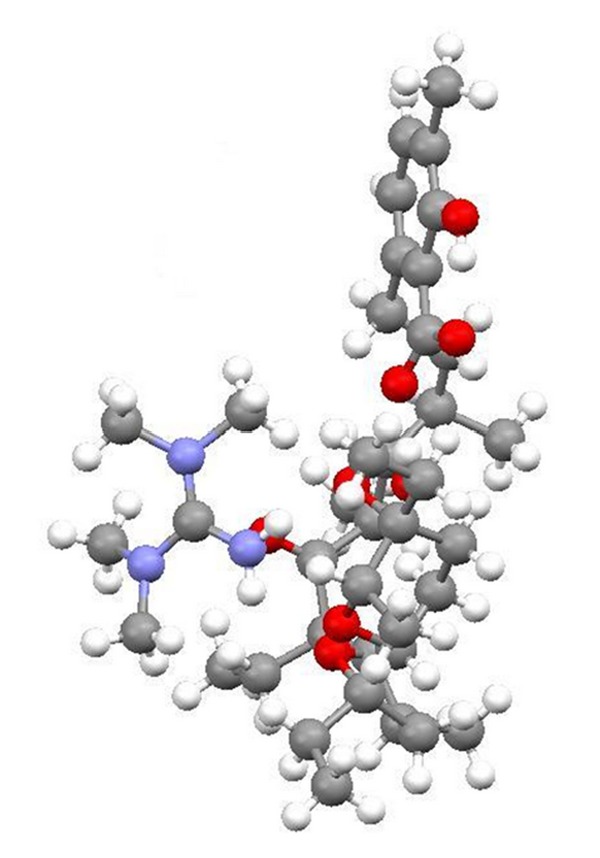

Figure 30.

Crystal structure of lasalocid complex with tetramethylguanidine.

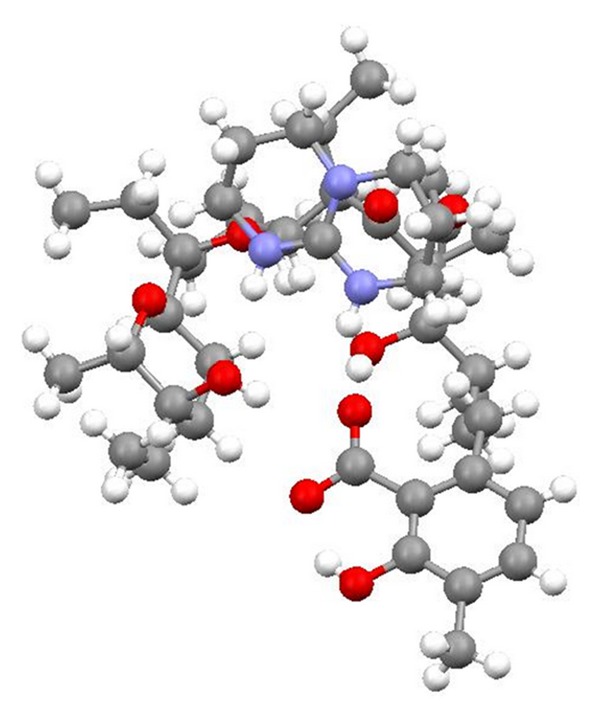

Figure 31.

Crystal structure of lasalocid complex with TBD.

Recently, two complexes of lasalocid (with phenylamine and butylamine) were tested in vitro for cytotoxic activity against human cancer cell lines: A-549 (lung), MCF-7 (breast), HT-29 (colon), and mouse cancer cell line P-388 (leukemia). It was found that lasalocid and its complexes are strong cytotoxic agents towards cell lines. The cytostatic activity of the compounds studied is greater than that of cisplatin, indicating that lasalocid and its complexes are promising candidates for new anticancer drugs [57].

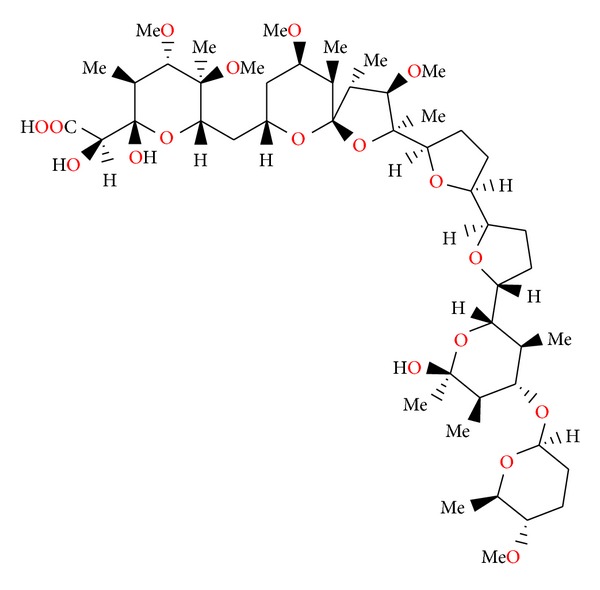

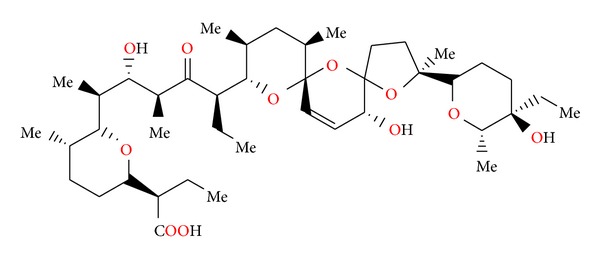

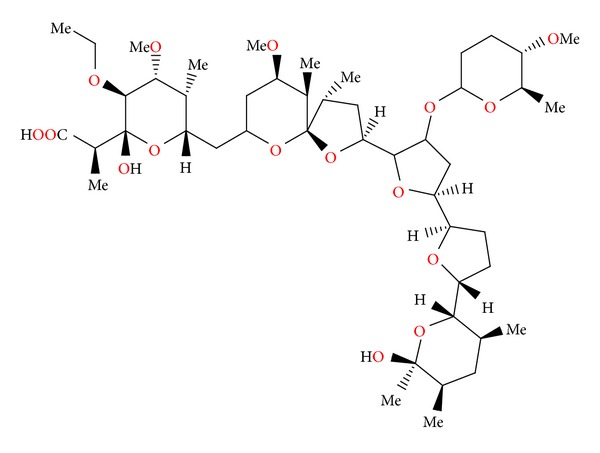

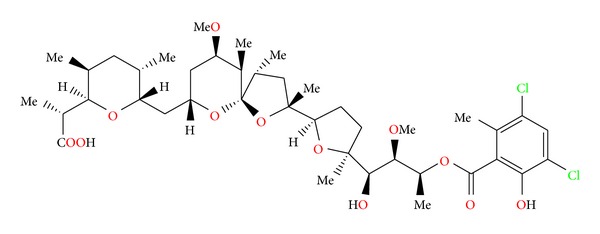

2.11. Semduramicin and CP-120509

Semduramicin (Figure 32) was isolated from Actinomadura roserufa [58]. The anticoccidial activity tests of semduramicin against laboratory isolates of five species of poultry Eimeria have shown that this antibiotic is active from 20 to 30 ppm concentrations. Semduramicin was well tolerated when coadministered with tiamulin [59].

Figure 32.

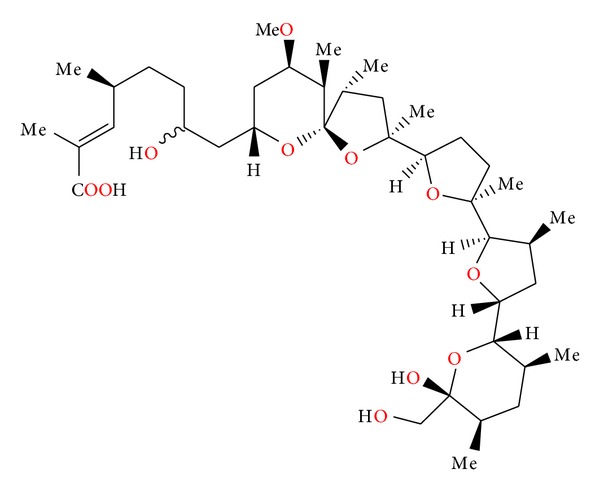

Structure of semduramicin.

Antibiotic CP-120509 (Figure 33) is also isolated from Actinomadura roserufa and is structurally related to semduramicin. Its crystal structure was reported [60]. CP-120509 exhibited in vitro activity against certain Gram-positive bacteria and the spirochete Serpulina hyodysenteriae, the causative agent of swine dysentery, but was inactive against Gram-negative bacteria. It afforded excellent anticoccidial activity against Eimeria acervulina in chickens at levels between 30 and 60 mg/kg in fed [60].

Figure 33.

Structure of CP-120509.

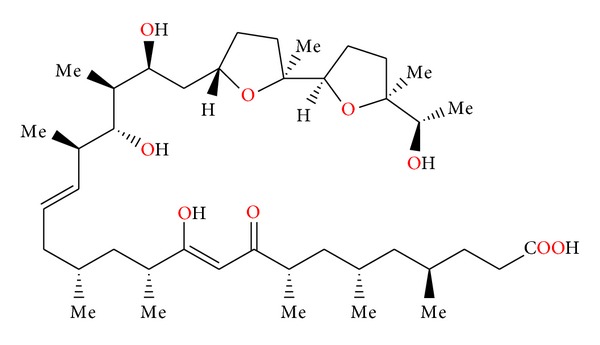

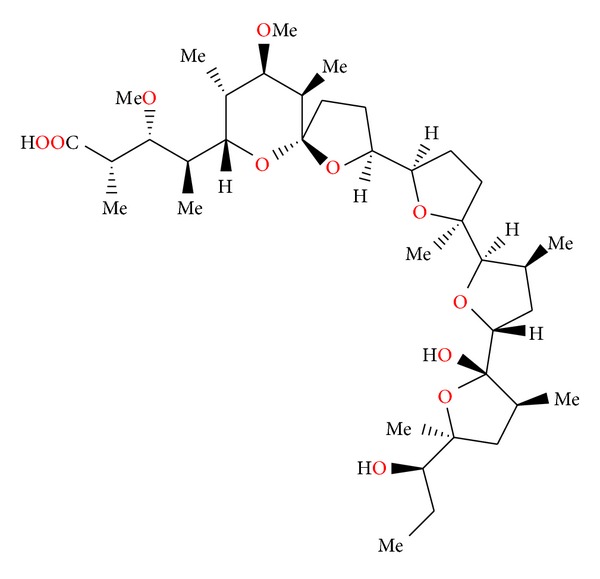

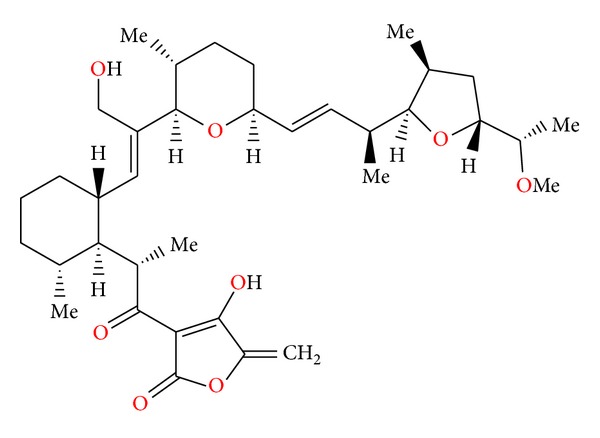

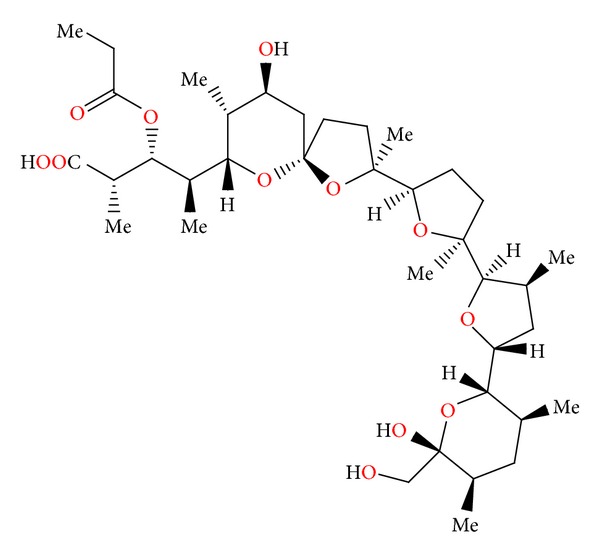

2.12. Tetronasin

Tetronasin (Figure 34) was isolated from Streptomyces longisporoflavus. The structure of this antibiotic has been determined by X-ray analysis of the 4-bromo-3,5-dinitrobenzoyl derivative [61].

Figure 34.

Structure of tetronasin.

Gram-positive bacteria are sensitive to the tetronasin and were unable to adapt to grow in the presence of this antibiotic. Gram-negative bacteria were more resistant. An in vivo trial with cattle and in vitro growth experiments indicated that the effect of tetronasin on ciliate protozoa was minor. In vitro experiments measuring hydrogen production by Neocallimastix frontalis suggested that this fungus would be unable to survive in ruminants receiving tetronasin [62].

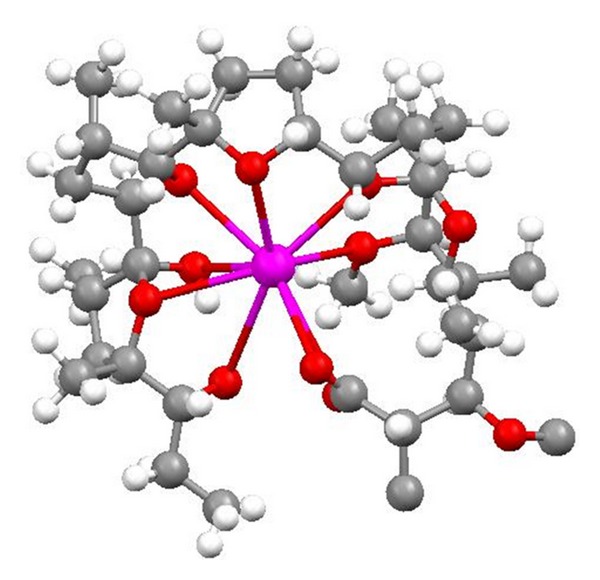

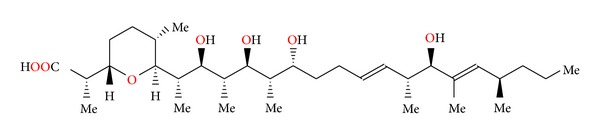

2.13. Zincophorin and CP-78545

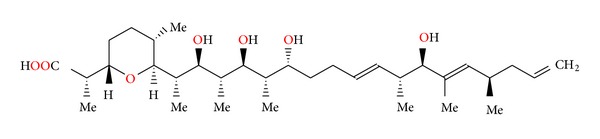

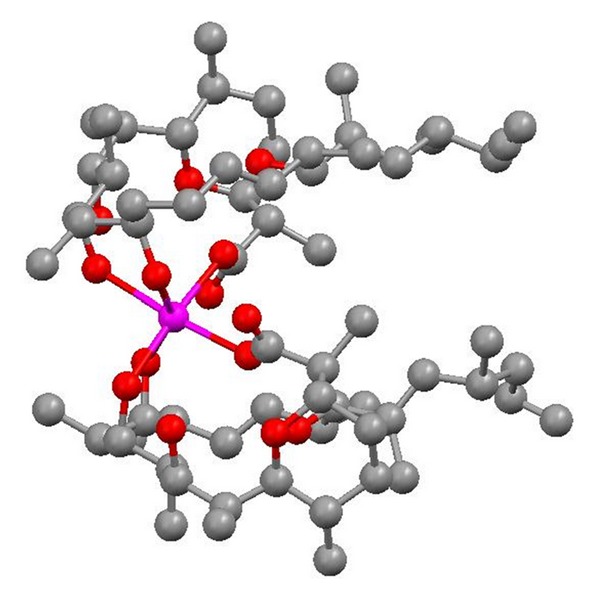

Zincophorin (Figure 35) was first isolated from Streptomyces griseus. Its crystal structure was determined by X-ray analysis of its magnesium salt (Figure 36) [63].

Figure 35.

Structure of zincophorin.

Figure 36.

Crystal structure of zincophorin magnesium salt.

Zincophorin is able to complex divalent cations, with the stability order of zinc ≈ cadmium > magnesium > strontium ≈ barium ≈ calcium.

Zincophorin showed good in vitro activity against Gram-positive bacteria. It also inhibited methane production and favourably altered volatile fatty acid ratios in in vitro rumen fermentations. It showed some anticoccidial activity against Eimeria tenella in chicks [63].

Antibiotic CP-78545 (Figure 37) also isolated from Streptomyces griseus is structurally related to zincophorin. Additional unsaturated bond is present in CP-78545 compared to zincophorin. Crystal structure of CP-78545 was determined by X-ray analysis of its cadmium salt (Figure 38).

Figure 37.

Structure of CP-78545.

Figure 38.

Crystal structure of CP-78545 cadmium salt.

CP-78545 exhibited in vitro antibiotic activity against certain Gram-positive bacteria such as Bacillus, Staphylococcus, and Streptococcus as well as the anaerobe Treponema hyodysenteriae (the causative agent of swine dysentery), but no activity towards Gram-negative bacteria. It was active in vitro against a coccidium Eimeria tenella in a tissue culture assay, but it was inactive in vivo at levels between 100 and 200 mg/kg in feed versus Eimeria tenella coccidial infections in chickens [64].

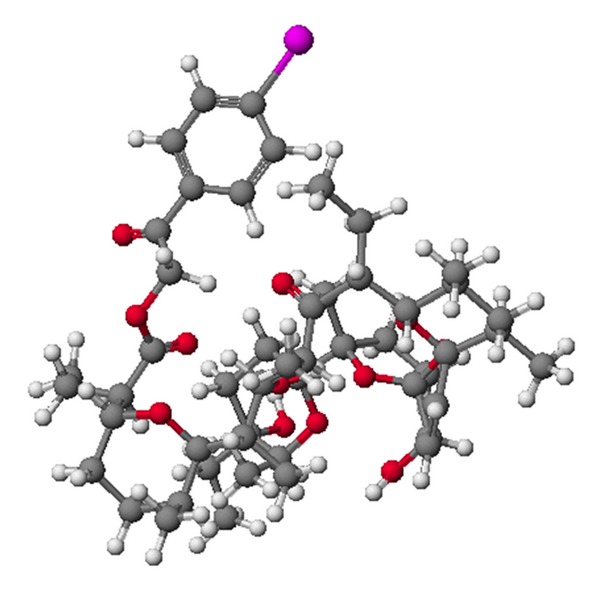

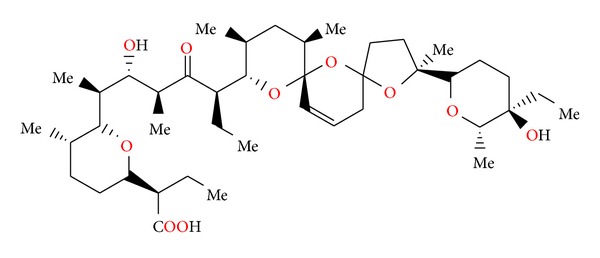

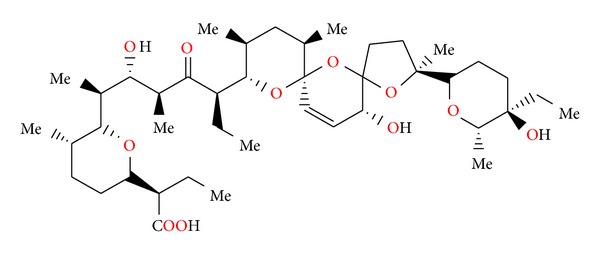

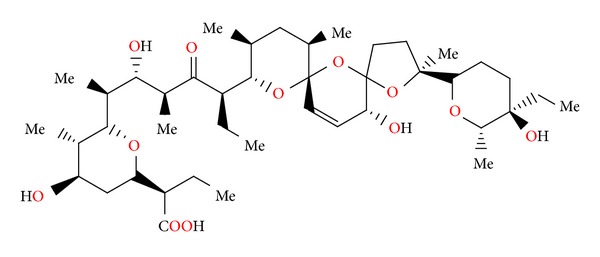

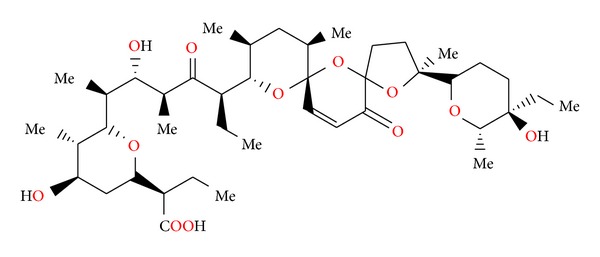

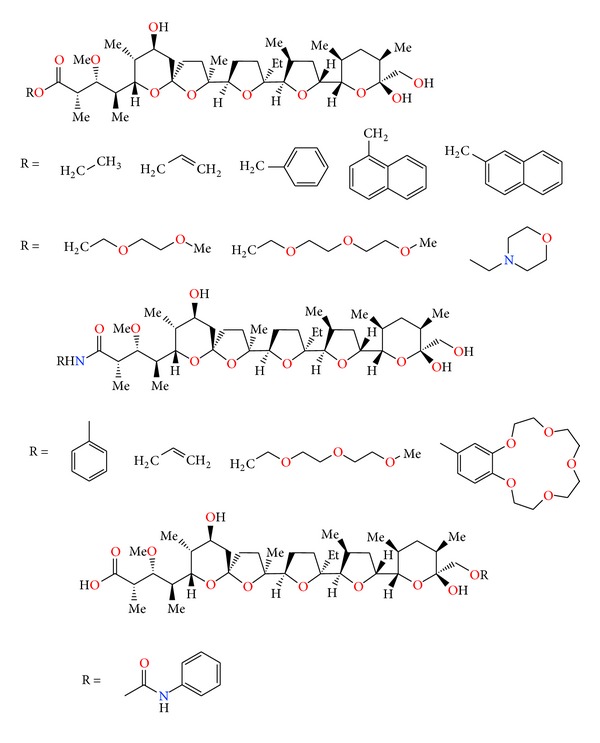

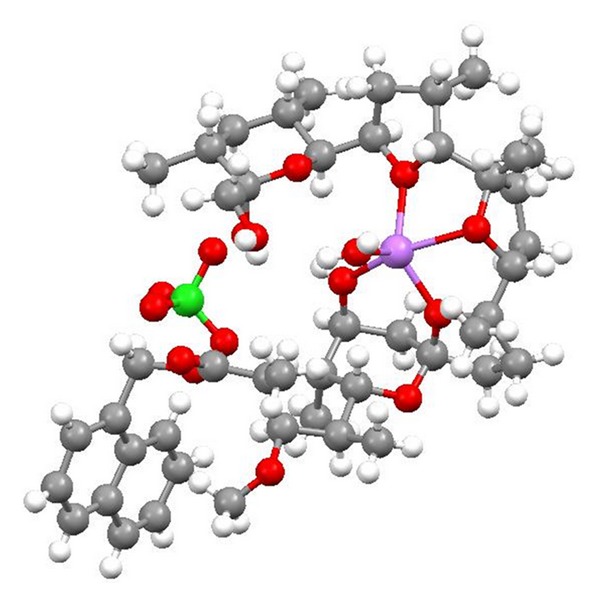

2.14. Salinomycin SY-1, SY-2, SY-4, and SY-9

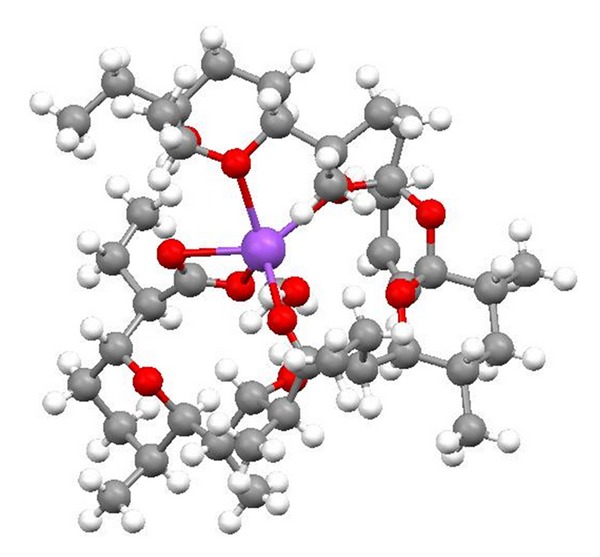

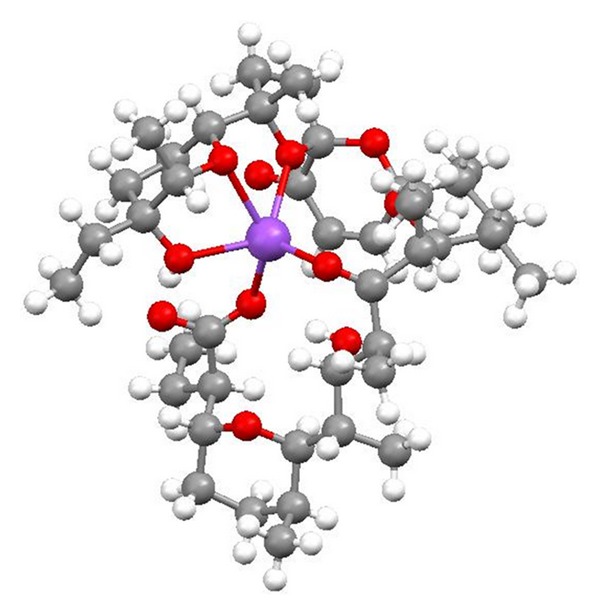

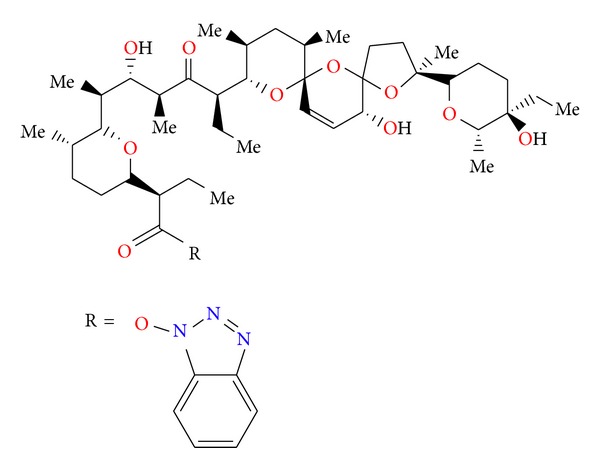

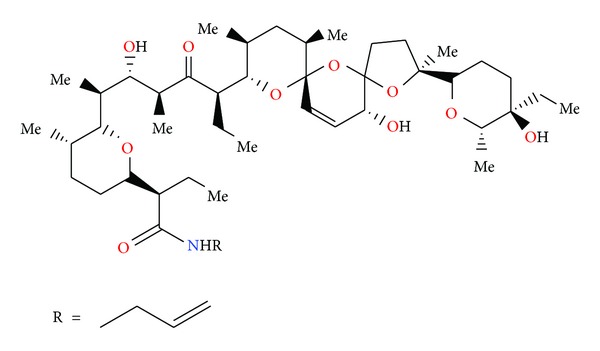

Salinomycin (Figure 39) was isolated from Streptomyces albus. Its crystal structure (Figure 40) has been established by X-ray analysis of its p-iodophenacyl ester [65]. Compounds structurally related to salinomycin have also been obtained and described. SY-1 (Figure 41) is 20-deoxysalinomycin. SY-2 (Figure 42) is C-17 epimer of SY-1 [66]. SY-4 (Figure 43) is 5-hydroxysalinomycin [67], and SY-9 (Figure 44) is 20-oxosalinomycin. Crystal structures of SY-1 (Figure 45) and SY-9 (Figure 46) were reported [68, 69]. Two other ester and amide derivatives of salinomycin (Figures 47 and 48) were obtained, and their crystal structures (Figures 49 and 50) were reported [70, 71].

Figure 39.

Structure of salinomycin.

Figure 40.

Crystal structure of salinomycin p-iodophenacyl ester.

Figure 41.

Structure of SY-1.

Figure 42.

Structure of SY-2.

Figure 43.

Structure of SY-4.

Figure 44.

Structure of SY-9.

Figure 45.

Crystal structure of SY-1 with the sodium cation.

Figure 46.

Crystal structure of SY-9 with the sodium cation.

Figure 47.

Structure of benzotriazole ester of salinomycin.

Figure 48.

Structure of allyl amide of salinomycin.

Figure 49.

Crystal structure of salinomycin benzotriazole ester acetonitrile solvate.

Figure 50.

Crystal structure of salinomycin allyl amide acetonitrile solvate.

The relative affinity of salinomycin for complex formation with various cations decreases in the order K+ > Na+ > Cs+ > Sr2+> Ca2+, Mg2+. Salinomycin has been shown to transport monovalent cations more effectively than divalent cations from an aqueous buffer into an organic solvent [72].

Salinomycin is active against Gram-positive bacteria including mycobacteria and some filamentous fungi. No activity was observed against Gram-negative bacteria and yeast. The acute toxicity of salinomycin in mice was examined, and its LD50 was 18 mg/kg intraperitoneally and 50 mg/kg orally. The anticoccidial estimation of salinomycin was carried out on chickens infected with Eimeria tenella. Salinomycin was effective in reducing mortality of chickens and in increasing the average body weight of treated infected chickens compared to those of untreated infected controls [73].

Very recently, it has been shown that it is possible to selectively kill breast cancer stem cells using salinomycin. Its ability to kill cancer stem cells and apoptosis-resistant cancer cells may define salinomycin as a novel anticancer drug [74].

2.15. Monensin

Monensin (Figure 51) was first isolated from Streptomyces cinnamonensis [75]. Crystal structures of monensin hydrate and its salts with sodium, lithium, and rubidium (Figures 52, 53, and 54) were reported [76–79]. In the last years Pantcheva et al. have shown that monensin (MON) can form two types of salt complex species with divalent metal cations.

Figure 51.

Structure of monensin.

Figure 52.

Crystal structure of monensin sodium salt acetonitrile solvate.

Figure 53.

Structure of monensin hydrate.

Figure 54.

Crystal structure of monensin lithium salt acetonitrile solvate.

In the first type, monensin sodium salt forms complexes with metal dichloride of [M(MON–Na)2]Cl2 ·H2O stoichiometry, where M = Co2+, Mn2+ and Cu2+. In this type of structure, the divalent metal cation is tetrahedrally coordinated by oxygen atoms of two carboxylic groups of two monensin sodium salt molecules and by two chloride anions. The sodium cation remains in the hydrophilic cavity of the ligand and cannot be replaced by the transition metal cation. The second type of monensin complexes with the divalent metal cations is the neutral salt of the [M(MON)2 ·(H2O)2] formula (M = Mg2+, Ca2+, Zn2+, Ni2+, Cd2+, and Hg2+). These salts consist of two monoanionic ligands (monensinates) bound in a bidentate coordination mode to the metal cation. These types of monensin salt complexes with divalent metal cation are untypical, because the etheric oxygen atoms do not play any role in the complexation of the cations. In contrast, in the typical complexes of monensin with monovalent metal cations, the etheric oxygen atoms of the monensin ligand are always involved in the complexation process [80–86]. A large group of monensin ester, amide, and urethane derivatives (Figure 55) was obtained and reported. Crystal structures of several of them (Figures 56 and 57) were also reported [87, 88]. Monensin exhibited in vitro antibiotic activity against certain Gram-positive bacteria such as Bacillus, Staphylococcus, and Streptococcus. No activity was observed against Gram-negative bacteria [89]. It was shown that monensin phenylurethane sodium salt shows a higher antibacterial activity against human pathogenic bacteria, including antibiotic-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis than the parent unmodified antibiotic monensin A [88]. Monensin blocks endocytosis and, therefore, impedes entry of toxic molecules. The drug also inhibits viral proliferation of RNA and DNA viruses such as vesicular stomatitis, influenza, and human polyomaviruses. Monensin also effectively abolishes viral DNA replication of mouse polyomavirus [90].

Figure 55.

Structures of monensin ester amide and urethane derivatives.

Figure 56.

Crystal structure of monensin 1-naphtylmethyl ester with the lithium perchlorate.

Figure 57.

Crystal structure of monensin phenylurethane sodium salt.

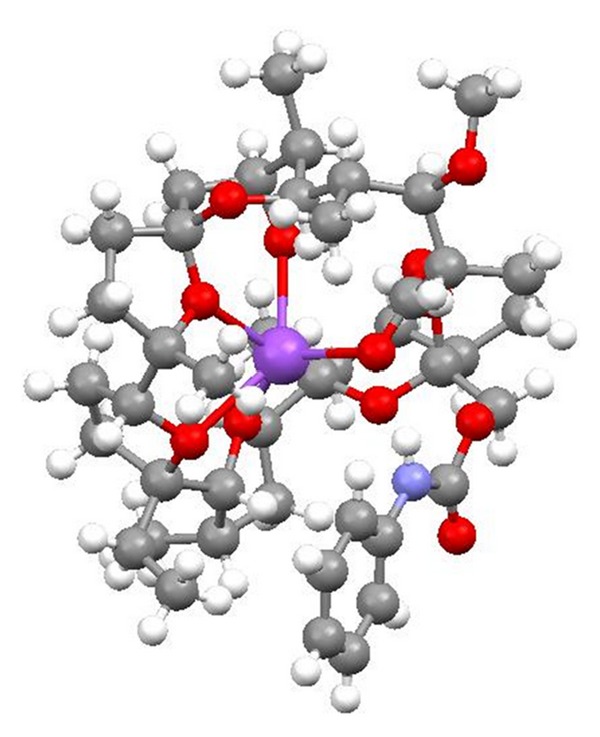

2.16. Ferensimycins A and B

Ferensimycins A and B (Figure 58) were isolated as their sodium salts from the fermentation broth of Streptomyces sp. No. 5057. Both antibiotics are active against Gram-positive bacteria but inactive against Gram-negative bacteria and fungi. The acute toxicity of these compounds in mice was examined, and the LD50 values of ferensimycin A and ferensimycin B were 30–50 mg/kg and 50 mg/kg, respectively [91].

Figure 58.

Structures of ferensimycins A and B.

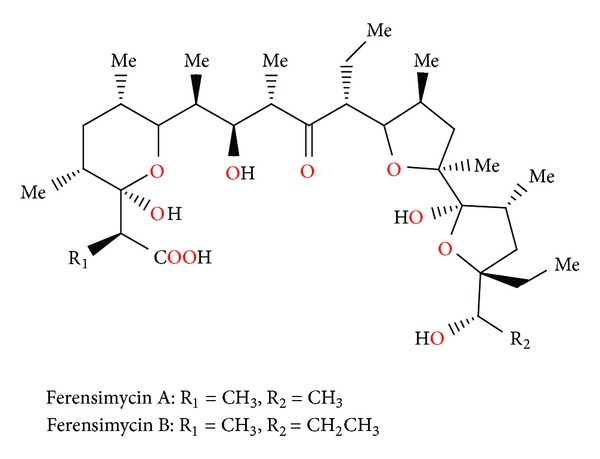

2.17. CP-96797

CP-96797 (Figure 59) was isolated from Sterptomyces sp. ATCC 55028. Crystal structure of the silver salt of this antibiotic was determined by X-ray analysis [92].

Figure 59.

Structure of CP-96797.

CP-96797 sodium salt showed good activity against a number of Gram-positive bacteria, as well as the spirochete Serpulina hyodysenteriae (the causative agent of swine dysentery), but was inactive against Gram-negative bacteria. It afforded anticoccidial activity against Eimeria tenella in chickens at levels between 60 and 90 mg/kg in feed [92].

2.18. Octacyclomycin

Octacyclomycin (Figure 60) was isolated from Streptomyces sp. No. 82. This antibiotic showed cytocidal activity against B16 melanoma cells, and its IC50 value was 0.23 μg/mL when the cells were exposed to the antibiotic for 3 days in vitro. On the other hand, octacyclomycin showed weak antimicrobial activity against Gram-positive bacteria such as Staphylococcus aureus and Micrococcus luteus at the concentration of 100 μg/mL, whereas Bacillus subtilis was not affected at this concentration [93].

Figure 60.

Structure of octacyclomycin.

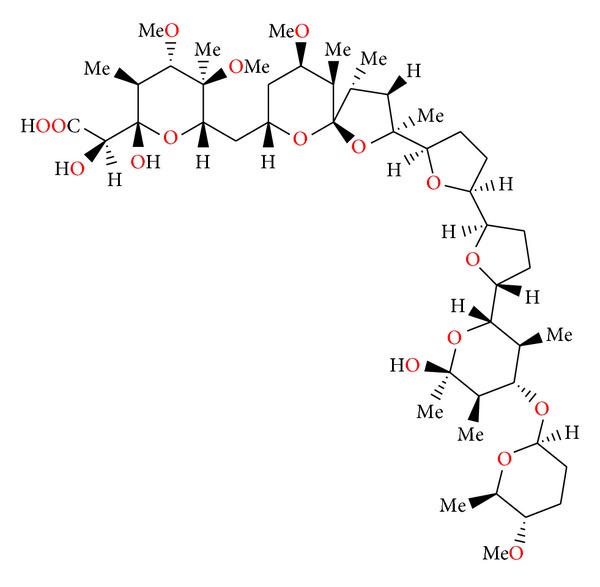

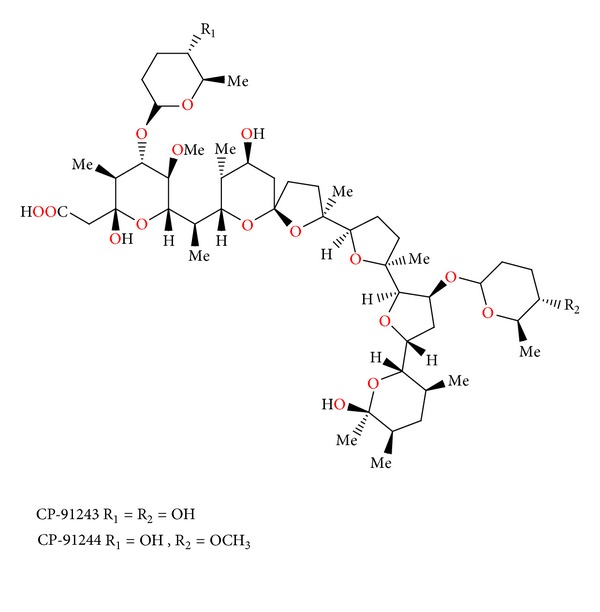

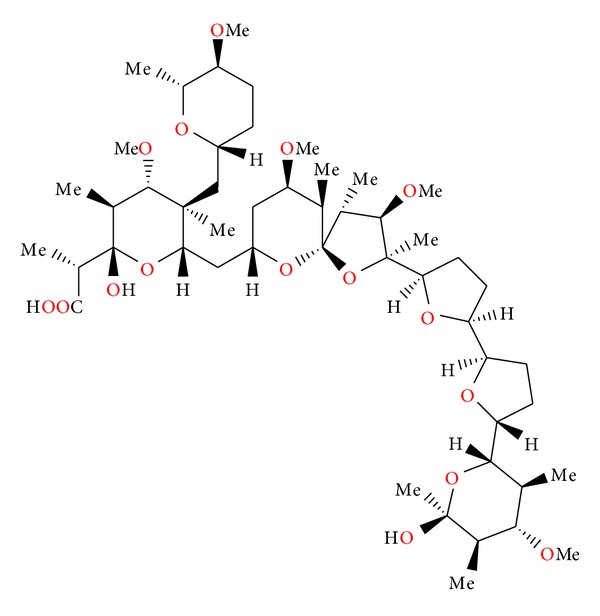

2.19. CP-91243 and CP-91244

CP-91243 and CP-91244 (Figure 61) were isolated from Actinomadura roseorufa. Both compounds exhibited in vitro activity against certain Gram-positive bacteria and the spirochete Treponema hyodysenteriae (the causative agent of swine dysentery), but were not active against Gram-negative bacteria. CP-91243 afforded anticoccidial activity against Eimeria tenella in chickens at 60 mg/kg in feed, and the less polar CP-91244 was about twice as active, 25 mg/kg in feed [94].

Figure 61.

Structures of CP-91243 and CP-91244.

2.20. W341C

W341C (Figure 62) was isolated from strains of Streptomyces W341. This antibiotic is K+-selective ionophore that inhibits mitochondrial substrate oxidation. W341C transported K+ ion at a greater rate than nigericin, but it transported Na+ ion at a lower rate than monensin. W341C is able to induce potassium loss in Bacillus subtilis and Streptococcus lactiae and promote potassium uptake into Escherichia coli [95].

Figure 62.

Structure of W341C.

2.21. Laidlomycin

Laidlomycin (Figure 63) was isolated from Streptomyces eurocidicus. This antibiotic inhibited growth of some Gram-positive bacteria only at high concentrations such as 50–100 mg/mL, but was not active against Gram-negative bacteria, yeast, and fungi. In broth dilution laidlomycin was active against several Mycoplasmas. The acute toxicity of laidlomycin, expressed as LD50, was 5 mg/kg (intraperitoneally) and 2.5 mg/kg (subcutaneously) in mice. Antitumor activity against Sarcoma 180 solid tumours in mice and antiviral activity against several viruses in vitro were examined but showed no significant effect [96].

Figure 63.

Structure of laidlomycin.

2.22. CP-84657

CP-84657 (Figure 64) was isolated from Actinomadura sp. ATCC 53708. Its crystal structure was determined by X-ray analysis of its rubidium salt. CP-84657 was active against Eimeria tenella (major causative agent of chicken coccidiosis) at doses of 5 mg/kg or less in feed. It was also active in vitro against certain Gram-positive bacteria, as well as the spirochete Treponema hyodysenteriae. No activity was observed against Escherichia coli [97].

Figure 64.

Structure of CP-84657.

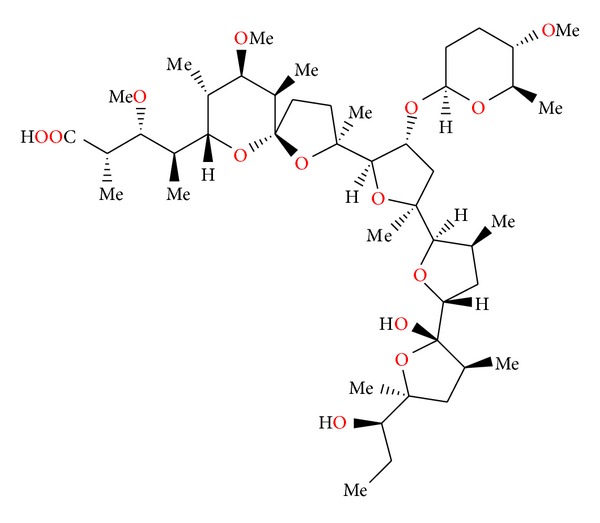

2.23. Grisorixin and Epigrisorixin

Grisorixin (Figure 65) was isolated from Streptomyces griseus [98]. Its crystal structure was determined by X-ray analysis of its thallium and silver salts [99, 100]. Grisorixin showed activity against Gram-positive bacteria, but was shown to be toxic. Determination of the toxicity of grisorixin in mice revealed LD50 of 15 mg/kg when the antibiotic was given subcutaneously [98].

Figure 65.

Structure of grisorixin.

Epigrisorixin (Figure 66) was isolated from Streptomyces hygroscopicus. Antimicrobial study showed that epigrisorixin is less toxic than grisorixin [101].

Figure 66.

Structure of epigrisorixin.

2.24. CP-54883

CP-54883 (Figure 67) was isolated from Actinomadura routienii [102]. Its crystal structure was determined by X-ray analysis of its benzoate derivative [103]. CP-54883 exhibited activity only against Gram-positive bacteria. It was not active against Gram-negative bacteria and yeasts. This antibiotic was active against Eimeria tenella, Eimeria maxima, and Eimeria acervulina coccidian when administrated in feed at 10 to 20 μg/g. Chickens were protected from lesions at the higher levels but suffered from poor weight gains and feed intake [100]. CP-54883 also induced a change in the proportion of volatile fatty acids (acetate, propionate, and butyrate) produced in the rumen by increasing the molar proportion of propionate in the rumen fluids [102].

Figure 67.

Structure of CP-54883.

2.25. SF-2487

SF-2487 (Figure 68) was isolated from a culture broth of Actinomadura sp. SF2487. Its crystal structure was determined by X-ray analysis of its silver salt [104]. SF-2487 showed moderate activity against Gram-positive bacteria, but no activity against Gram-negative bacteria. SF-2487 exhibited in vitro antiviral activity against influenza virus. The LD50 value of SF-2487 was 25 mg/kg by injection in mice [104].

Figure 68.

Structure of SF-2487.

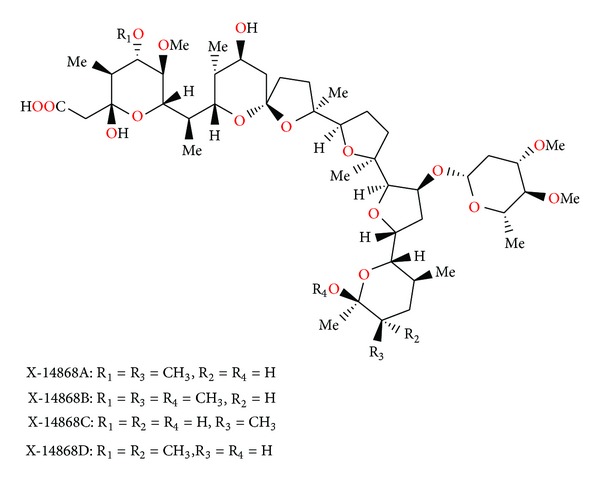

2.26. X-14868A, X-14868B, X-14868C, and X-14868D

Four polyether antibiotics (Figure 69) were isolated from a culture of Nocardia (strain X-14868A, X-14868B, X-14868C, and X-14868D). Crystal structures of each of these antibiotics were determined by X-ray analysis [105]. All four compounds were active against Gram-positive bacteria and exhibited no activity against Gram-negative bacteria and fungi. Antibiotic X-14868A was also active against Treponema hyodysenteriae [105].

Figure 69.

Structures of X-14868A, X-14868B, X-14868C, and X-14868D.

2.27. CP-80219

Cp-80219 (Figure 70) was isolated from Streptomyces hygroscopicus. Its crystal structure was determined by X-ray analysis of its rubidium salt [106]. CP-80219 sodium salt showed good activity against Gram-positive bacteria as well as the spirochete Treponema hyodysenteriae. No activity was observed against Gram-negative bacteria including Escherichia coli. It afforded anticoccidial activity between 30 and 120 mg/kg in feed against Eimeria tenella in chickens [106].

Figure 70.

Structure of CP-80219.

2.28. Moyukamycin

Moyukamycin (Figure 71) was isolated from Streptomyces hygroscopicus. It showed activity against a wide range of Gram-positive bacteria, while no activity against Gram-negative bacteria [107].

Figure 71.

Structure of moyukamycin.

2.29. X-14931A

X-14931 (Figure 72) was isolated from a culture of Streptomyces sp. X-14931. Its crystal structure was determined by X-ray analysis of its silver salt [108]. Antibiotic X-14931A showed in vitro activity against Gram-positive microorganisms and yeasts. It was also active against mixed Eimeria infection in chickens at 50 μg/g in feed. The antibiotic also exhibited activity in the rumen growth promotant test [108].

Figure 72.

Structure of X-14931A.

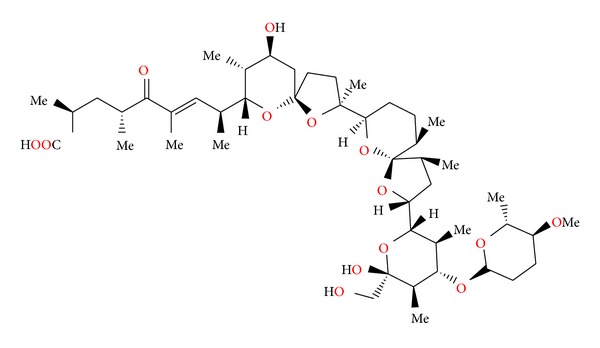

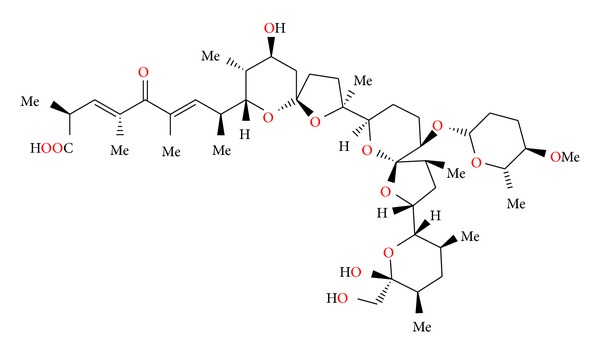

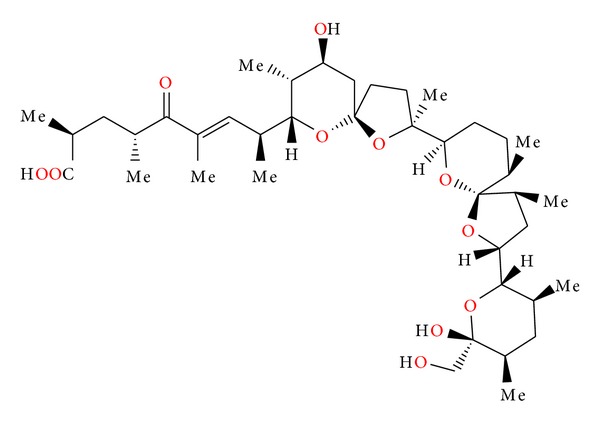

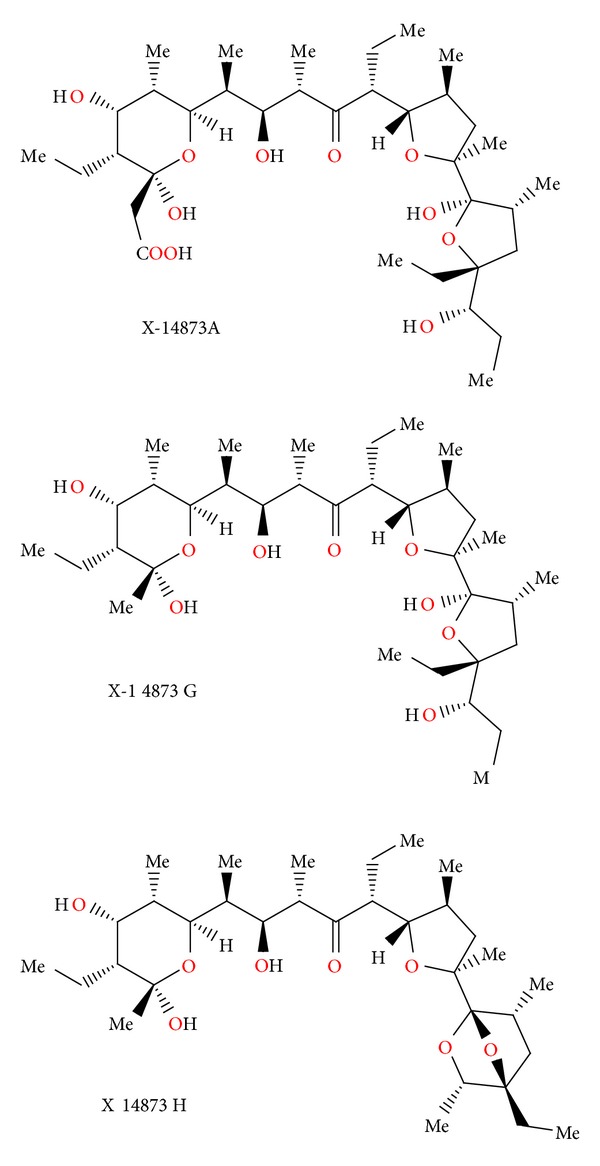

2.30. X-14873A, X-14873G, and X-14873H

Three polyether ionophores: X-14873A, X-14873G, and X-14873H (Figure 73) were isolated from the fermentation of Streptomyces sp. X-14873 (ATCC31679). Crystal structures of X-14873A and X-14873H were reported [109]. Antibiotic X-14873A was mainly active against Gram-positive bacteria and exhibited no activity against Gram-negative bacteria. It was interesting to note that X-14873H, the descarboxyl derivative of X-14873A, was also active against Gram-positive bacteria, while the other descarboxyl derivative, X-14873G, was practically inactive. These results indicated that the carboxylic function of the polyether antibiotic molecule was not required for the antimicrobial activity, even though the ionized carboxylic group played an important role in complexation of cations by carboxylic acid polyether ionophores [110]. Antibiotic X-14873A also induced a change in the proportion of volatile fatty acids (acetate, propionate, and butyrate) produced in the rumen by increasing the molar proportion of propionate in the rumen fluid [110].

Figure 73.

Structures of X-14873A, X-14873G, and X-14873H.

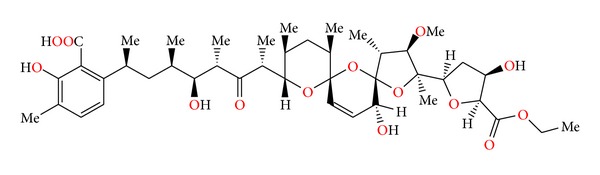

2.31. Noboritomycin

Noboritomycin (Figure 74) was isolated from Streptomyces noboritoensis. Crystal structure was determined by X-ray analysis of its silver salt. Noboritomycin was the first polyether ionophore possessing two carboxylic acid functions on the carbon backbone, namely, a free acid and an additional carboxylic acid ethyl ester group [111]. Noboritomycin was active against a wide range of Gram-positive bacteria, but was inactive against Gram-negative bacteria and yeasts. It exhibited only weak anticoccidial activity (Eimeria tenella) in chicken [111].

Figure 74.

Structure of noboritomycin.

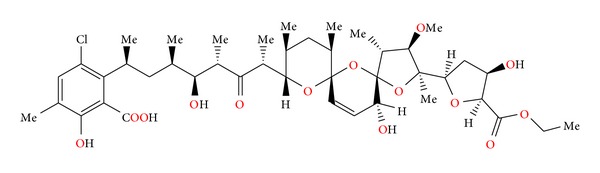

2.32. 6-chloronoboritomycin

6-chloronoboritomycin (Figure 75) was isolated from Streptomyces malachitofuscus [112]. Its crystal structure was determined by X-ray analysis of its thallium and rubidium salts [113]. This antibiotic is able to complex and transport monovalent as well as divalent metal cations. 6-chloronoboritomycin is active against Gram-positive bacteria and some anaerobes. In addition, it exhibits in vitro activity against several strains of Treponema hyodysenteriae, a causal agent of swine dysentery [112].

Figure 75.

Structure of 6-chloronoboritomycin.

2.33. CP-82009

CP-82009 (Figure 76) was isolated by solvent extraction from the fermentation broth of Actinomadura sp. ATCC 53676. Its crystal structure was determined by X-ray analysis of its rubidium salt. CP-82009 exhibited activity against Gram-positive bacteria, as well as the spirochete Treponema hyodysenteriae. No activity was observed against Escherichia coli [114].

Figure 76.

Structure of CP-82009.

2.34. Abierixin

Abierixin (Figure 77) was isolated from Streptomyces albus. It exhibited weak activity against Gram-positive bacteria. The acute toxicity of abierixin in mice was examined. The LD50 value was 80–100 mg/kg. The anticoccidial evaluation of abrexin was carried out with chickens infected with Eimeria tenella. Abierixin, at 40 ppm, was effective in reducing the mortality of chickens and in increasing the average body weight of treated infected chickens compared to untreated infected controls [115].

Figure 77.

Structure of abierixin.

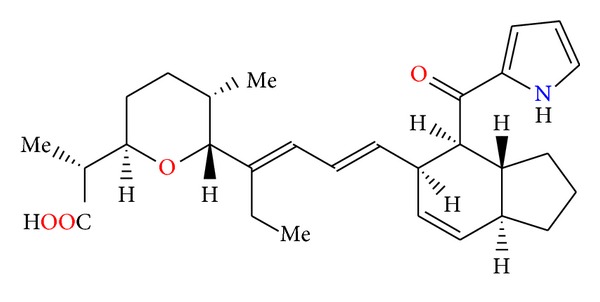

2.35. A-83094A

A-83094A (Figure 78) was isolated from the strain of Streptomyces setonii. The antibiotic is active against Gram-positive bacteria. At a concentration of 0.31 μg/mL, it completely inhibits the development of Eimeria tenella. However, the compound showed no efficacy in vivo when chicks infected with Eimeria tenella or Eimeria acervulina were fed a diet containing 200 μg/g A-83094A [116].

Figure 78.

Structure of A-83094A.

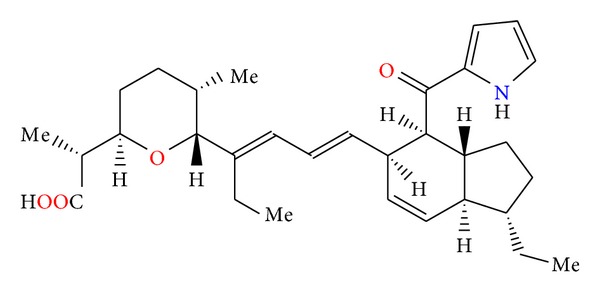

2.36. Indanomycin

Indianomycin (Figure 79) was isolated from the strain of Streptomyces antibioticus [117]. Its crystal structure was determined by X-ray analysis of its bromophenethylamine salt [118]. Indianomycin was active in vitro against Gram-positive bacteria. It is also effective as a growth promotant for ruminants, increasing feed utilization by these animals [117].

Figure 79.

Structure of indanomycin.

3. Conclusion

Polyether ionophores are generally active against Gram-positive bacteria. These compounds are able to form complexes with metal cations and transport them across lipid bilayer. In consequence, the whole process leads to changes in the osmotic pressure inside the cell, causing death of the bacteria cell. Some of them also show anticoccidial activity. Recently, it has been shown that several ionophores exhibit anticancer activities (monensin, salinomycin, and laidlomycin). Results of many studies have shown that both cancer stem cells (CSCs) and multidrug-resistant cancer cells (MDR) are effectively killed by polyether ionophores particularly by salinomycin. Polyether ionophores are currently well-recognized candidates to be clinically tested as anticancer drug candidates. The activity of these compounds should be further studied in vitro to specify their mechanisms of action and in vivo to assess their activities and tolerance in the different types of cancer. The studies performed so far have shown that these compounds affect cancer cells in a special way by increasing their sensitivity to chemotherapy (monensin, salinomycin, inostamycin) and reverse multidrug resistance (laidlomycin and monensin) in human carcinoma. Furthermore, these compounds have been found to be cytotoxic to the human carcinoma multidrug-resistant cells (monensin and salinomycin). Ionophore antibiotics also inhibit chemoresistant cancer cells by increasing apoptosis, but up to now, only salinomycin has been successfully able to kill human cancer stem cells (CSCs). Therefore, polyether antibiotics should be considered as new anticancer drugs for cancer prevention and cancer therapy, and the mechanism of their anticancer activity should be studied in detail.

References

- 1.Dutton CJ, Banks BJ, Cooper CB. Polyether ionophores. Natural Product Reports. 1995;12(2):165–181. doi: 10.1039/np9951200165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Callaway TR, Edrington TS, Rychlik JL, et al. Ionophores: their use as ruminant growth promotants and impact on food safety. Current Issues in Intestinal Microbiology. 2003;4(2):43–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rochefeuille S, Jimenez C, Tingry S, Seta P, Desfours JP. Mixed Langmuir-Blodgett monolayers containing carboxylic ionophores. Application to Na+ and Ca2+ ISFET-based sensors. Materials Science and Engineering C. 2002;21(1-2):43–46. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gabrielli C, Hemery P, Letellier P, et al. Investigation of ion-selective electrodes with neutral ionophores and ionic sites by EIS. II. Application to K+ detection. Journal of Electroanalytical Chemistry. 2004;570(2):291–304. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dobler M. Natural cation-binding agents. In: Gokel GW, editor. Comprehensive Supramolecular Chemistry: Molecular Recognition: Receptors for Cationic Guests. Vol. 1. New York, NY, USA: Pergamon; 2004. pp. 267–313. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mollenhauer HH, Morre DJ, Rowe LD. Alteration of intracellular traffic by monensin; mechanism, specificity and relationship to toxicity. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1990;1031(2):225–246. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(90)90008-Z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pressman BC. Antibiotics and Their Complexes. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lindoy LF. Outer-sphere and inner-sphere complexation of cations by the natural ionophore lasalocid A. Coordination Chemistry Reviews. 1996;148:349–368. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Inabayashi M, Miyauchi S, Kamo N, Jin T. Conductance change in phospholipid bilayer membrane by an electroneutral ionophore, monensin. Biochemistry. 1995;34(10):3455–3460. doi: 10.1021/bi00010a038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsukube H, Takagi K, Higashiyama T, Iwachido T, Hayama N. Biomimetic membrane transport: interesting ionophore functions of naturally occurring polyether antibiotics toward unusual metal cations and amino acid ester salts. Inorganic Chemistry. 1994;33(13):2984–2987. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ahmed S, Booth IR. Quantitative measurements of the proton-motive force and its relation to steady state lactose accumulation in Escherichia coli . Biochemical Journal. 1981;200(3):573–581. doi: 10.1042/bj2000573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuhn M, King HD. Belgian Patent, 839355, 1976.

- 13.Allèaume M, Busetta B, Farges C, Gachon P, Kergomard A, Staron T. X-Ray structure of alborixin, a new antibiotic ionophore. Journal of the Chemical Society, Chemical Communications. 1975;(11):411–412. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Roey P, Duax WL, Strong PD, Smith GD. Israel Journal of Chemistry. 1984;24:p. 283. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gachon P, Farges C, Kergomard A. Alborixin, a new antibiotic ionophore: isolation, structure, physical and chemical properties. Journal of Antibiotics. 1976;29(6):603–610. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.29.603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kusakabe Y, Mitsuoka S, Omuro Y, Seino A. Antibiotic No. 6016, a polyether antibiotic. Journal of Antibiotics. 1980;33(12):1437–1442. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.33.1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Otake N, Ogita T, Nakayama H, Miyamae H, Sato S, Saito Y. X-Ray crystal structure of the thallium salt of antibiotic-6016, a new polyether ionophore. Journal of the Chemical Society, Chemical Communications. 1978;(20):875–876. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gale RM, Higgens CE, Hoehn MM. US Patent, 3923823, 1975.

- 19.Smith GD, Duax WL. Crystal and molecular structure of the calcium ion complex of A23187. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1976;98(6):1578–1580. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alleaume M, Barrans Y. Crystal structure of the magnesium complex of calcimycin. Canadian Journal of Chemistry. 1985;63(12):3482–3485. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Akkurt M, Melhaoui A, Ben Hadda T, Mimouni M, Öztürk Yíldírím S, McKeec V. Synthesis and crystal structure of the bis-calcimycin anion-Ni2+ complex. Arkivoc. 2008;2008(11):154–164. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vila S, Canet I, Guyot J, Jeminet G, Toupet L. Unusual structure of the dimeric 4-bromocalcimycin-Zn2+ complex. Chemical Communications. 2003;9(4):516–517. doi: 10.1039/b210280n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grenier G, Van Sande J, Glick D, Dumont JE. Effect of ionophore A23187 on thyroid secretion. FEBS Letters. 1974;49(1):96–99. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(74)80640-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karl RC, Zawalich WS, Ferrendelli JA, Matschinsky FM. The role of Ca2+ and cyclic adenosine 3′ : 5′ monophosphate in insulin release induced in vitro by the divalent cation ionophore A23187. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1975;250(12):4575–4579. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Case GD, Vanderkooi JM, Scarpa A. Physical properties of biological membranes determined by the fluorescence of the calcium ionophore A23187. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 1974;162(1):174–185. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(74)90116-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guyot J, Jeminet G, Prudhomme M, Sancelme M, Meiniel R. Interaction of the calcium ionophore A.23187 (calcimycin) with Bacillus cereus and Escherichia coli . Letters in Applied Microbiology. 1993;16(4):192–195. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klika KD, Haansuu JP, Ovcharenko VV, et al. Frankiamide: a structural revision to demethyl (C-11) cezomycin. Zeitschrift für Naturforschung. 2003;58(12):1210–1215. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Westley JW, Liu CM, Blount JF. Isolation and characterization of a novel polyether antibiotic of the pyrrolether class, antibiotic X-14885A. Journal of Antibiotics. 1983;36(10):1275–1278. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.36.1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sakurai T, Kobayashi K, Nakamura G, Isono K. Structure of the thallium salt of cationomycin. Acta Crystallographica Section B. 1982;38(9):2471–2473. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ubukata M, Hamazaki Y, Isono K. Chemical modification of cationomycin and its structure-activity relationship. Agricultural and Biological Chemistry. 1986;50(5):1153–1160. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ubukata M, Akama T, Isono K. Aromatic side chain analogs of cationomycin and their biological activities. Agricultural and Biological Chemistry. 1988;52(7):1637–1641. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Delort AM, Jeminet G, Sareth S, Riddle FG. Ionophore properties of cationomycin in large unilamellar vesicles studied by 23Na- and 39K-NMR. Chemical and Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 1998;46(10):1618–1620. doi: 10.1248/cpb.46.1618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oscarson JR, Bordner J, Celmer WD, et al. Endusamycin, a novel polycyclic ether antibiotic produced by a strain of Streptomyces endus subsp. aureus . Journal of Antibiotics. 1989;42(1):37–48. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.42.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fehr T, King HD, Kuhn M. Mutalomycin, a new polyether antibiotic. Taxonomy, fermentation, isolation and characterization. Journal of Antibiotics. 1977;30(11):903–907. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.30.903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fehr T, Kuhn M, Loosli HR, Ponelle M, Boelsterli JJ, Walkinshaw MD. 2-Epimutalomycin and 28-epimutalomycin, two new polyether antibiotics from Streptomyces mutabilis. Derivatization of mutalomycin and the structure elucidation of two minor metabolites. Journal of Antibiotics. 1989;42(6):897–902. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.42.897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu CM, Hermann TE. Characterization of ionomycin as a calcium ionophore. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1978;253(17):5892–5894. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gao Z, Li Y, Cooksey JP, et al. A synthesis of an ionomycin calcium complex. Angewandte Chemie—International Edition. 2009;48(27):5022–5025. doi: 10.1002/anie.200901608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu WC, Smith-Slusarczyk D, Astle G, Trejo WH, Brown WE, Meyers E. Ionomycin, a new polyether antibiotic. Journal of Antibiotics. 1978;31(9):815–819. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.31.815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tsuji N, Nagashima K, Kobayashi M, et al. Two new antibiotics, A 218 and K 41 isolation and characterization. Journal of Antibiotics. 1976;29(1):10–14. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.29.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shiro M, Nakai H, Nagashima K, Tsuji N. X-Ray determination of the structure of the polyether antibiotic K-41. Journal of the Chemical Society, Chemical Communications. 1978;(16):682–683. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Otoguro K, Ishiyama A, Ui H, et al. In vitro and in vivo antimalarial activities of the monoglycoside polyether antibiotic, K-41 against drug resistant strains of Plasmodia. Journal of Antibiotics. 2002;55(9):832–834. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.55.832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Takahashi Y, Nakamura H, Ogata R, et al. Kijimicin, a polyether antibiotic. Journal of Antibiotics. 1990;43(4):441–443. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.43.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yamauchi T, Nakamura M, Honma H, Ikeda M, Kawashima K, Ohno T. Mechanistic effects of Kijimicin on inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus replication. Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry. 1993;119(1-2):35–41. doi: 10.1007/BF00926851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Berger J, Rachlin AI, Scott WE, Sternbach LH, Goldberg MW. The isolation of three new crystalline antibiotics from Streptomyces . Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1951;73(11):5295–5298. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Johnson SM, Herrin J, Liu SJ, Paul IC. Crystal structure of a barium complex of antibiotic X-537A, Ba(C34H53O8)2 · H2O. Journal of the Chemical Society D. 1970;(2):72–73. doi: 10.1021/ja00717a047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Suh IH, Aoki K, Yamazaki H. Crystal structure of a silver salt of the antibiotic lasalocid A: a dimer having an exact 2-fold symmetry. Inorganic Chemistry. 1989;28(2):358–362. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Akkurt M, Öztürk Yildirim S, Khardli FZ, Mimouni M, McKee V, Ben Haddab T. Crystal structure of a new polymeric thallium-lasalocid complex: iasalocide anion-thallium(I) containing aryl-Tl interactions. Arkivoc. 2008;2008(15):121–132. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Westley JW, Benz W, Donahue J. Biosynthesis of lasalocid. III Isolation and structure determination of four homologs of lasalocid A. Journal of Antibiotics. 1974;27(10):744–753. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.27.744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Coffen DA, Katonak DA. Chemical degradation of lasalocid: (A) The Mannich reaction (B) Bayer-Villiger oxidation of the retro-aldol ketone. Helvetica Chimica Acta. 1981;64(5):1645–1652. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Huczyński A, Paluch I, Ratajczak-Sitarz M, et al. Spectroscopic studies, crystal structures and antimicrobial activities of a new lasalocid 1-naphthylmethyl ester. Journal of Molecular Structure. 2008;891(1–3):481–490. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Huczyński A, Paluch I, Ratajczak-Sitarz M, Katrusiak A, Brzezinski B, Bartl F. Structural and spectroscopic studies of a new 2-naphthylmethyl ester of lasalocid acid. Journal of Molecular Structure. 2009;918(1–3):108–115. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Huczyński A, Pospieszny T, Wawrzyn R, et al. Structural and spectroscopic studies of new o-, m- and p-nitrobenzyl esters of lasalocid acid. Journal of Molecular Structure. 2008;877(1–3):105–114. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Huczyński A, Ratajczak-Sitarz M, Katrusiak A, Brzezinski B. X-ray, spectroscopic and semiempirical investigation of the structure of lasalocid 6-bromohexyl ester and its complexes with alkali metal cations. Journal of Molecular Structure. 2011;998(1–3):206–215. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Huczyński A, Janczak J, Rutkowski J, et al. Lasalocid acid as a lipophilic carrier ionophore for allylamine: spectroscopic, crystallographic and microbiological investigation. Journal of Molecular Structure. 2009;936(1–3):92–98. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Huczyński A, Janczak J, Stefańska J, Rutkowski J, Brzezinski B. X-ray, spectroscopic and antibacterial activity studies of the 1 : 1 complex of lasalocid acid with 1,1,3,3-tetramethylguanidine. Journal of Molecular Structure. 2010;977(1–3):51–55. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Huczyński A, Pospieszny T, Ratajczak-Sitarz M, Katrusiak A, Brzezinski B. Structural and spectroscopic studies of the 1 : 1 complex of lasalocid acid with 1,5,7-triazabicyclo[4.4.0]dec-5-ene. Journal of Molecular Structure. 2008;875(1–3):501–508. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Huczynski A, Rutkowski J, Wietrzyk J, et al. X-Ray crystallographic, FT-IR and NMR studies as well as anticancer and antibacterial activity of the salt formed between ionophor antibiotic Lasalocid acid and amines. Journal of Molecular Structure. 2012;1032:69–77. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tynan EJ, Nelson TH, Davies RA, Wernau WC. The production of semduramicin by direct fermentation. Journal of Antibiotics. 1992;45(5):813–815. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.45.813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ricketts AP, Glazer EA, Migaki TT, Olson JA. Anticoccidial efficacy of semduramicin in battery studies with laboratory isolates of coccidia. Poultry Science. 1992;71(1):98–103. doi: 10.3382/ps.0710098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dirlam JP, Bordner J, Chang SP, et al. The isolation and structure of CP-120,509, a new polyether antibiotic related to semduramicin and produced by mutants of Actinomadura roseorufa . Journal of Antibiotics. 1992;45(9):1544–1548. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.45.1544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Davies DH, Snape EW, Suter PJ, King TJ, Falshaw CP. Structure of antibiotic M139603; x-ray crystal structure of the 4-bromo-3,5-dinitrobenzoyl derivative. Journal of the Chemical Society, Chemical Communications. 1981;(20):1073–1074. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Newbold CJ, Wallace RJ, Watt ND, Richardson AJ. Effect of the novel ionophore tetronasin (ICI 139603) on ruminal microorganisms. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 1988;54(2):544–547. doi: 10.1128/aem.54.2.544-547.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Brooks HA, Gardner D, Pyser JP, King TJ. The structure and absolute stereochemistry of zincophorin (antibiotic M144255): a monobasic carboxylic acid ionophore having a remarkable specificity for divalent cations. Journal of Antibiotics. 1984;37(11):1501–1504. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.37.1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dirlam JP, Belton AM, Shang SP, et al. CP-78,545, a new monocarboxylic acid ionophore antibiotic related to zincophorin and produced by a Streptomyces . Journal of Antibiotics. 1989;42(8):1213–1220. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.42.1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kinashi H, Otake N, Yonehara H. The structure of salinomycin, a new member of the polyether antibiotics. Tetrahedron Letters. 1973;49:4955–4958. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Westley JW, Blount JF, Evans RH, Liu CM. C-17 epimers of deoxy-(O-8)-salinomycin from Streptomyces albus (ATCC 21838) Journal of Antibiotics. 1977;30(7):610–612. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.30.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Miyazaki Y, Shibata A, Yahagi T, et al. Japanese Patent, 61247398, 1986.

- 68.Paulus EF, Vértesy L. Crystal structure of the antibiotic SY-1 (20-deoxy-salinomycin): sodium 2-(6-[2-(5-ethyl-5-hydroxy-6-methyl-tetrahydro-pyran-2-yl)-2,10,12-trimethyl-1, 6,8-trioxa-dispiro[4.1.5.3]pentadec-13-en-9-yl]-2-hydroxy-1,3-dimethyl-4-oxo- heptyl-5-methyl-tetrahydro-pyran-2-yl)-butyrate—methanol solvate (1 : 0.69), C42H69NaO10 · 0.69CH3OH. Zeitschrift für Kristallographie. 2003;218(4):575–577. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Paulus EF, Vértesy L. Crystal structure of 2-(6-[2-(5-ethyl-5-hydroxy-6-methyl-tetrahydro-pyran2- yl)-15-oxo-2,10,12-trimethyl-1,6,8-trioxa-dispiro[4.1.5.3]pentadec-13-en-9-yl] -2-hydroxy-1,3-dimethyl-4-oxo-heptyl-5-methyl-tetrahydro-pyran-2-yl)-butyrate sodium, Na(C42H67O11), SY-9—antibiotic 20-oxo-salinomycin. Zeitschrift für Kristallographie. 2004;219(2):184–186. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Huczyński A, Janczak J, Antoszczak M, Stefanska J, Brzezinski B. X-ray, FT-IR, NMR and PM5 structural studies and antibacterial activity of unexpectedly stable salinomycin-benzotriazole intermediate ester. Journal of Molecular Structure. 2012;1022:197–203. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Huczyński A, Janczak J, Stefanska J, Antoszczak M, Brzezinski B. Synthesis and antimicrobial activity of amide derivatives of polyether antibiotic—salinomycin. Bioorganic and Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 2012;22(14):4697–4702. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.05.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mitani M, Yamanishi T, Miyazaki Y. Salinomycin: a new monovalent cation ionophore. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1975;66(4):1231–1236. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(75)90490-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Myiazaki Y, Shibuya M, Sugawara H, et al. Salinomycin, a new polyether antibiotic. Journal of Antibiotics. 1974;27(11):814–821. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.27.814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Huczyński A. Salinomycin—a new cancer drug candidate. Chemical Biology and Drug Design. 2012;79(3):235–238. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2011.01287.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Agtarap A, Chamberlin JW, Pinkerton M, Steinrauf L. The structure of monensic acid, A new biologically active compound. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1967;89(22):5737–5739. doi: 10.1021/ja00998a062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Huczyński A, Ratajczak-Sitarz M, Katrusiak A, Brzezinski B. Molecular structure of the 1 : 1 inclusion complex of monensin A sodium salt with acetonitrile. Journal of Molecular Structure. 2007;832(1–3):84–89. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Huczyński A, Janczak J, Łowicki D, Brzezinski B. Monensin a acid complexes as a model of electrogenic transport of sodium cation. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1818;(9):2108–2119. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2012.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Huczyński A, Ratajczak-Sitarz M, Katrusiak A, Brzezinski B. Molecular structure of the 1 : 1 inclusion complex of monensin A lithium salt with acetonitrile. Journal of Molecular Structure. 2007;871(1–3):92–97. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Huczyński A, Ratajczak-Sitarz M, Katrusiak A, Brzezinski B. Molecular structure of rubidium six-coordinated dihydrate complex with monensin A. Journal of Molecular Structure. 2008;888(1–3):224–229. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Pantcheva IN, Zhorova R, Mitewa M, Simova S, Mayer-Figge H, Sheldrick WS. First solid state alkaline-earth complexes of monensic acid A (MonH): crystal structure of [M(Mon)2(H2O)2] (M = Mg, Ca), spectral properties and cytotoxicity against aerobic Gram-positive bacteria. BioMetals. 2010;23(1):59–70. doi: 10.1007/s10534-009-9269-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Pantcheva IN, Ivanova J, Zhorova R, et al. Nickel(II) and zinc(II) dimonensinates: single crystal X-ray structure, spectral properties and bactericidal activity. Inorganica Chimica Acta. 2010;363(8):1879–1886. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Dorkov P, Pantcheva IN, Sheldrick WS, Mayer-Figge H, Petrova R, Mitewa M. Synthesis, structure and antimicrobial activity of manganese(II) and cobalt(II) complexes of the polyether ionophore antibiotic Sodium Monensin A. Journal of Inorganic Biochemistry. 2008;102(1):26–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2007.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Pantcheva IN, Dorkov P, Atanasov VN, et al. Crystal structure and properties of the copper(II) complex of sodium monensin A. Journal of Inorganic Biochemistry. 2009;103(10):1419–1424. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2009.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ivanova J, Pantcheva IN, Mitewa M, Simova S, Mayer-Figge H, Sheldrick WS. Crystal structures and spectral properties of new Cd(II) and Hg(II) complexes of monensic acid with different coordination modes of the ligand. Central European Journal of Chemistry. 2010;8(4):852–860. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Pantcheva IN, Mitewa MI, Sheldrick WS, Oppel IM, Zhorova R, Dorkov P. First divalent metal complexes of the polyether ionophore monensin A: x-ray structures of [Co(Mon)2(H2O)2] and [Mn(Mon)2(H2O)2] and their bactericidal properties. Current Drug Discovery Technologies. 2008;5(2):154–161. doi: 10.2174/157016308784746247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Huczyński A, Łowicki D, Ratajczak-Sitarz M, Katrusiak A, Brzezinski B. Structural investigation of a new complex of N-allylamide of Monensin A with strontium perchlorate using X-ray, FT-IR, ESI MS and semiempirical methods. Journal of Molecular Structure. 2011;995(1–3):20–28. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Huczyński A, Janczak J, Brzezinski B. Crystal structure and FT-IR study of aqualithium 1-naphthylmethyl ester of monensin A perchlorate. Journal of Molecular Structure. 2011;985(1):70–74. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Huczyński A, Ratajczak-Sitarz M, Stefańska J, Katrusiak A, Brzezinski B, Bartl F. Reinvestigation of the structure of monensin A phenylurethane sodium salt based on X-ray crystallographic and spectroscopic studies, and its activity against hospital strains of methicillin-resistant S. epidermidis and S. aureus . Journal of Antibiotics. 2011;64(3):249–256. doi: 10.1038/ja.2010.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Huczyński A, Stefańska J, Przybylski P, Brzezinski B, Bartl F. Synthesis and antimicrobial properties of Monensin A esters. Bioorganic and Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 2008;18(8):2585–2589. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Iacoangeli A, Melucci-Vigo G, Risuleo G. The ionophore monensin inhibits mouse polyomavirus DNA replication and destabilizes viral early mRNAs. Biochimie. 2000;82(1):35–39. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(00)00358-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kusakabe Y, Mizuno T, Kawabata S. Ferensimycins A and B, two polyether antibiotics. Journal of Antibiotics. 1982;35(9):1119–1129. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.35.1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Dirlam JP, Bordner J, Cullen WP, Jefferson MT, Presseau-Linabury L. The structure of CP-96,797, polyether antibiotic related to K-41A and produced by Streptomyces sp . Journal of Antibiotics. 1992;45(7):1187–1189. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.45.1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Funayama S, Nozoe S. Isolation and structure of a new polyether antibiotic, octacyclomycin. Journal of Antibiotics. 1992;45(10):1686–1691. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.45.1686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Dirlam JP, Cullen WP, Huang LH, et al. CP-91,243 and CP-91,244, novel diglycosine polyether antibiotics related to UK-58,852 and produced by mutants of Actinomadura roseorufa . Journal of Antibiotics. 1991;44(11):1262–1266. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.44.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Wehbie RS, Runsheng C, Lardy HA. The antibiotic W341C, its ion transport properties and inhibitory effects on mitochondrial substrate oxidation. Journal of Antibiotics. 1987;40(6):887–893. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.40.887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kitame F, Utsushikawa K, Kohama T. Laidlomycin, a new antimycoplasmal polyether antibiotic. Journal of Antibiotics. 1974;27(11):884–888. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.27.884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Dirlam JP, Belton AM, Bordner J, et al. CP-84,657, a potent polyether anticoccidial related to portmicin and produced by Actinomadura sp . Journal of Antibiotics. 1990;43(6):668–679. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.43.668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Gachon P, Kergomard A, Staron T, Esteve C. Grisorixin, an ionophorous antibiotic of the nigericin group. I. Fermentation, isolation, biological properties and structure. Journal of Antibiotics. 1975;28(5):345–350. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.28.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Alleaume M, Hickel D. The crystal structure of grisorixin silver salt. Journal of the Chemical Society D. 1970;(21):1422–1423. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Alleaume M, Hickel D. Crystal structure of the thallium salt of the antibiotic grisorixin. Journal of the Chemical Society, Chemical Communications. 1972:175–176. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Mouslim J, Cuer A, David L, Tabet JC. Epigrisorixin, a new polyether carboxylic antibiotic. Journal of Antibiotics. 1993;46(1):201–203. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.46.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Cullen WP, Celmer WD, Chappel LR, et al. CP-54,883 a novel chlorine-containing polyether antibiotic produced by a new species of Actinomadura: taxonomy of the producing culture, fermentation, physico-chemical and biological properties of the antibiotic. Journal of Antibiotics. 1987;40(11):1490–1495. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.40.1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Bordner J, Watts PC, Whipple EB. Structure of the natural antibiotic ionophore CP-54,883. Journal of Antibiotics. 1987;40(11):1496–1505. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.40.1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Hatsu M, Sasaki T, Miyadoh S, et al. SF2487, a new polyether antibiotic produced by Actinomadura . Journal of Antibiotics. 1990;43(3):259–266. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.43.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Liu CM, Hermann TE, Downey A. Novel polyether antibiotics X-14868A, B, C, and D produced by a Nocardia. Discovery, fermentation, biological as well as ionophore properties and taxonomy of the producing culture. Journal of Antibiotics. 1983;36(4):343–350. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.36.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Dirlam JP, Presseau-Linabury L, Koss DA. The structure of CP-80,219, a new polyether antibiotic related to dianemycin. Journal of Antibiotics. 1990;43(6):727–730. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.43.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Nakayama H, Seto H, Otake N. Studies on the ionophorous antibiotics. XXVIII. Moyukamycin, a new glycosylated polyether antibiotic. Journal of Antibiotics. 1985;38(10):1433–1436. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.38.1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Westley JW, Chao-Min Liu, Sello LH. Isolation and characterization of antibiotic X-14931A, the naturally occurring 19-deoxyaglycone of dianemycin. Journal of Antibiotics. 1984;37(7):813–815. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.37.813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Westley JW, Liu CM, Blount JF. Isolation and characterization of three novel polyether antibiotics and three novel actinomycins as cometabolites of the same Streptomyces sp. X-14873, ATCC 31679. Journal of Antibiotics. 1986;39(12):1704–1711. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.39.1704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Liu CM, Westley JW, Hermann TE. Novel polyether antibiotics X-14873A, G and H produced by a Streptomyces: taxonomy of the producing culture, fermentation, biological and ionophorous properties of the antibiotics. Journal of Antibiotics. 1986;39(12):1712–1718. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.39.1712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Keller-Juslen C, King HD, Kuhn M. Noboritomycins A and B, new polyether antibiotics. Journal of Antibiotics. 1978;31(9):820–828. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.31.820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Liu C, Hermann TE, La Prosser TB. X-14766A, a halogen containing polyether antibiotic produced by Streptomyces malachitofuscus subsp. downeyi ATCC 31547. Discovery, fermentation, biological properties and taxonomy of the producing culture. Journal of Antibiotics. 1981;34(2):133–138. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.34.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Westley JW, Evans RH, Sello LH. Isolation and characterization of the first halogen containing polyether antibiotic X-14766A, a product of Streptomyces malachitofuscus subsp. downeyi. Journal of Antibiotics. 1981;34(2):139–147. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.34.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Dirlam JP, Belton AM, Bordner J, et al. CP-82,009, a potent polyether anticoccidial related to septamycin and produced by Actinonladura sp . Journal of Antibiotics. 1992;45(3):331–340. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.45.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.David L, Ayala HL, Tabet JC. Abierixin, a new polyether antibiotic. Production, structural determination and biological activities. Journal of Antibiotics. 1985;38(12):1655–1663. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.38.1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Larsen SH, Boeck LVD, Mertz FP, Paschal JW, Occolowitz JL. 16-Deethylindanomycin (A83094A), a novel pyrrole-ether antibiotic produced by a strain of Streptomyces setonii. Taxonomy, fermentation, isolation and characterization. Journal of Antibiotics. 1988;41(9):1170–1177. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.41.1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Liu CM, Hermann TE, Liu M. X-14547A, a new ionophorous antibiotic produced by Streptomyces antibioticus NRRL 8167. Discovery, fermentation, biological properties and taxonomy of the producing culture. Journal of Antibiotics. 1979;32(2):95–99. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.32.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Westley JW, Evans RH, Sello LH. Isolation and characterization of antibiotic X-14547A, a novel monocarboxylic acid ionophore produced by Streptomyces antibioticus NRRL 8167. Journal of Antibiotics. 1979;32(2):100–107. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.32.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]