Abstract

Purpose

Investigate the efficacy and pharmacodynamic effects of MK-1775, a potent Wee1 inhibitor, in both monotherapy and in combination with gemcitabine using a panel of p53-deficient and p53-wild type human pancreatic cancer xenografts.

Experimental design

Nine individual patient-derived pancreatic cancer xenografts (six with p53-deficient and three with p53-wild type status) from the PancXenoBank collection at Johns Hopkins were treated with MK-1775, gemcitabine or gemcitabine followed 24 h later by MK-1775 for 4 weeks. Tumor growth rate/regressions were calculated on day 28. Target modulation was assessed by western blot and IHC.

Results

MK-1775 treatment led to the inhibition of Wee1 kinase and reduced inhibitory phosphorylation of its substrate Cdc2. MK-1775, when dosed with gemcitabine, abrogated the checkpoint arrest to promote mitotic entry and facilitated tumor cell death as compared to control and gemcitabine treated tumors. MK-1775 monotherapy did not induce tumor regressions. However, the combination of gemcitabine with MK-1775 produced robust anti-tumor activity and remarkably enhanced tumor regression response (4.01 fold) compared to gemcitabine treatment in p53-deficient tumors. Tumor re-growth curves plotted after the drug treatment period suggest that the effect of the combination therapy is longer-lasting than that of gemcitabine. None of the agents produced tumor regressions in p53-wild type xenografts.

Conclusions

These results indicate that MK-1775 selectively synergizes with gemcitabine to achieve tumor regressions, selectively in p53-deficient pancreatic cancer xenografts.

Keywords: MK-1775, Wee1 kinase, pancreatic cancer, chemotherapy, cell cycle inhibitor

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDA) remains one of the least curable cancers, ranking fourth in cancer related deaths in the United States (1). Worldwide, PDA contributes to more than 230,000 deaths annually (2). Gemcitabine (GEM), a pyrimidine antimetabolite, is the accepted standard treatment for patients with advanced and metastatic PDA, but the benefit is small (3). The addition of other chemotherapeutics or monoclonal antibodies or radiation to GEM has not resulted any meaningful improvement in the survival of PDA patients (4–6). As the current therapies offer very limited benefit, there is significant unmet medical need to identify novel molecular targets and develop novel therapeutic strategies to treat this devastating disease (7).

Treatment efficacy of DNA damaging agents is determined not only by the amount of therapy-induced DNA damage but also by the capacity of tumor cells to repair the damaged DNA. Many of the conventional anticancer treatments including antimetabolites, ionizing radiation, alkylating agents, platinum compounds and DNA topoisomerase inhibitors exert their anti-tumor effects by damaging the DNA in tumor cells which leads to apoptosis (8). However, when cells are treated with DNA damaging agents, multiple checkpoints are activated, including G1, intra-S, and G2/M, leading to cell cycle arrest, thus providing time for the cell to repair the damage and to evade apoptosis before resuming the cell cycle (9–11). Tumor cells can exploit these repair mechanisms in response to DNA damaging chemotherapeutics, rendering tumors refractory to current therapeutic interventions. Therefore, abrogation of checkpoints function may drive tumor cells toward apoptosis and enhance the efficacy of oncotherapy. p53 is a key regulator of the G1 checkpoint and is one of the most frequently mutated genes in cancer. Since G1 checkpoint is frequently compromised due to loss-of-function mutation of p53 gene in 50–70% of all cancers, the G2/M checkpoint plays a pivotal role in preventing the programmed cell death in p53-deficient tumors (12, 13). Hence, inhibitors of the G2 checkpoint can selectively sensitize cancer cells with deficient-p53 to killing by DNA-damaging anti-cancer agents while sparing normal tissue from toxicity. The G2 DNA damage checkpoint ensures maintenance of cell viability by delaying progression into mitosis when cells have suffered DNA damage. Wee1 is a cellular protein kinase which inhibits Cdc2 activity, thereby preventing cells from proceeding through mitosis by maintaining G2 arrest (14). Wee1 reversibly arrests the cell cycle by inactivating Cdc2 through phosphorylation at Tyr-15 (15). Disruption of this phosphorylation site abrogates checkpoint-mediated regulation of Cdc2 (16). Wee1 knockdown with siRNA has been reported to abrogate the G2 DNA damage checkpoint arrest and to sensitize cancer cells to DNA damaging agents (17). Wee1 kinase inhibition is expected to potentiate the anti-tumor effect of DNA damaging chemotherapeutics by overcoming the G2 arrest and thereby promoting checkpoint bypass to facilitate the preferential killing of p53-deficient tumor cells via mitotic catastrophe.

MK-1775 is the first reported Wee1 inhibitor with high potency, selectivity and oral bioavailability in preclinical animal models and is currently being evaluated in several phase I clinical trials (18–21). Given that p53 mutations are common in pancreatic cancer (22), we sought to investigate efficacy and pharmacodynamic effects of MK-1775 alone and in combination with GEM in pancreatic cancer xenografts with p53-wild type or p53-deficient status. Our results provide compelling evidence that MK-1775 synergizes with GEM to achieve tumor regressions, selectively in p53-deficient pancreatic cancer xenografts. These results may help to frame clinical investigation of Wee1 inhibitors along with chemotherapy to benefit cancer patients whose tumor cells are devoid of functional p53 gene.

Materials and methods

Animals and establishment of xenografts model

Animal experiments were conducted following approval and accordance with Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines of Johns Hopkins University. Fresh pancreatic cancer specimens resected from patients at the time of surgery, with informed written patient consent, were implanted subcutaneously (s.c.) into the flanks of 6-week-old female nu/nu athymic mice (Harlan). The patients had not undergone chemotherapy or radiation therapy before surgery. Grafted tumors were subsequently transplanted from mouse to mouse and maintained as a live PancXenoBank according to an IRB approved protocol (23). Tumor-specific mutations of protein-coding genes (exomic sequencing) in these xenografts have been recently reported (24). Most importantly, these xenografts were not placed in culture and appear to retain most of the genetic features of the original tumor, despite serial passing across several generations of mice (25, 26).

Drugs

The Wee1 inhibitor, MK-1775, was provided by Merck Research Laboratories (Upper Gwynedd, PA). GEM (Eli Lilly, Indianapolis, IN) was purchased from pharmacy.

In vivo efficacy experiments

Nine pancreatic cancer xenografts (six with p53-deficient and 3 with p53-wild type status) from PancXenoBank were allowed to grow separately on both flanks of athymic mice. When tumors reached a volume of ~200 mm3, mice were individually identified and randomly assigned to treatment groups, with 5–6 mice (8–10 evaluable tumors) in each group: 1) control; 2) MK-1775 (30 mg/kg. p.o., once daily for 4 weeks; 3) GEM (100 mg/kg, i.p., twice weekly on days 1 and 4) for 4 weeks; 4) GEM followed 24 h later by MK-1775 in the above mentioned dose. Tumor growth was evaluated twice per week by measurement of two perpendicular diameters of tumors with a digital caliper. Individual tumor volumes were calculated as V = a × b2/2, a being the largest diameter, b the smallest. Relative tumor growth index (TGI) on day 28 was calculated using the formula: (mean tumor volume of drug-treated group/mean tumor volume of control group) × 100. Number of tumors that regressed more than 50% of its initial size in each xenograft was noted. Animals were sacrificed 1 h after the last dose of GEM or MK-1775 and tumors were harvested for analysis except three mice each from GEM and combination treatment group, which were kept longer to check tumor re-growth after the treatment. Mice kept for the re-growth study were sacrificed when the tumors reached the size of control tumors in that xenograft.

Protein extraction and western blotting

Protein extracts were prepared from tumors according to previously published method (27). Briefly, tumors (50 mg) were minced on ice in prechilled lysis buffer containing protease cocktail (Roche Molecular Biochemicals). The minced tissue was homogenized and centrifuged at 16,000 × g at 4° C for 10 min. Protein content in the supernatants was measured with the Pierce Protein Assay kit using bovine serum albumin as a standard. Protein lysates (30 μg) were boiled in Laemmli sample buffer (Bio-Rad Laboratories) resolved by electrophoresis on 4–12% Bis-Tris precast gels (Bio-Rad Laboratories), and transferred to Immobilon-P membranes (Millipore). Membranes were blocked at room temperature with 5% non fat milk (Pierce) for 1 h. Primary antibodies against Wee1, p-Wee1Ser642, Cdc2, p-Cdc2Tyr15, p-histone H3Ser10 (p-HH3Ser10), cleaved poly(ADP-ribose) polymeraseAsp214 (C-PARP Asp214), p-H2AXSer139 (γ-H2AX), cellular inhibitor of apoptosis protein-2 (cIAP2) and Cyclin B1 (Cell Signaling Technology) were diluted (1:1,000) in 5% BSA and incubated overnight at 4°C with mild rocking. Membranes were probed with secondary anti-rabbit IgG horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibody (GE Healthcare) at a final dilution of 1:2,000 for 2 h. After washing three times with TBST, bound antibodies were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence (GE Healthcare) or Supersignal West Femto (Pierce). Equal loading was verified with β-actin antibody.

Immunohistochemistry

Sections were prepared from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tumor samples. To ensure uniform handling of samples, all sections were processed simultaneously. Sections were deparaffinized by routine techniques and were quenched with 3% H2O2 for 10 min. The slides were steamed in citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for 20 minutes at 90+° C and were blocked with 10% fetal bovine serum solution (Invitrogen) for 30 min prior to incubation with primary antibodies. For the phospho-Cdc2 staining, phospho-Cdc2Tyr15 antibody (Cell Signaling Technology) was used at a dilution of 1:200 followed by 1 h incubation. For phosho-histone H3 detection, phosho-histone H3Ser10 antibody (Cell Signaling Technology) was used at a 1:250 dilution and incubated overnight at 4° C. Sections were incubated with with EnVision/HRP rabbit antibody for 30 min and diaminobenzidine (DAB+) chromogen for 10 min. The sections were counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated, and mounted. Slides were evaluated by a pathologist under 20X objective and digitized using a color camera mounted to the microscope. p-Cdc2Tyr15 and p-HH3Ser10 stained tumor cells were counted over total number of tumor cells and two sided Fisher’s exact test (GraphPad Prism 5.03 software) was used for significance calculation.

Statistical analysis

All error bars are represented as the standard error of the mean. Significance was analyzed using unpaired Student’s t-test. The differences were considered significant when P-value was < 0.05.

Results and discussion

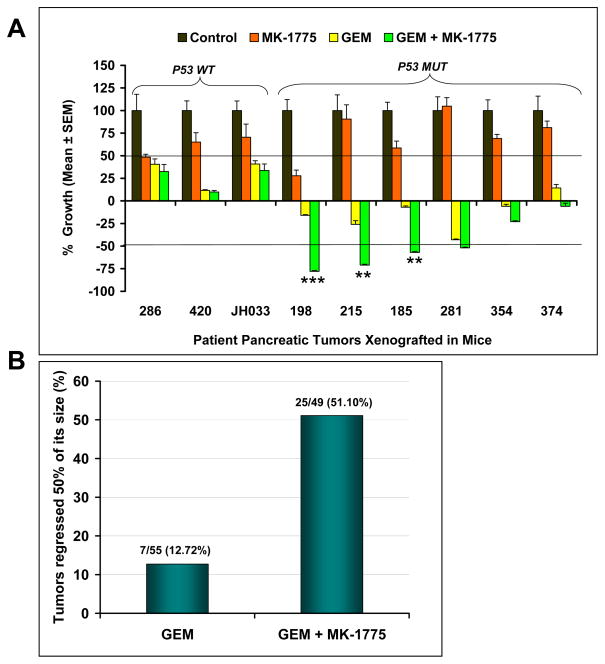

The principal aim of this study was to investigate the efficacy of MK-1775 as a single agent and in combination with GEM in PDA xenografts and to assess whether the status of the p53 gene had any role in dictating the efficacy of the treatment. We used a xenograft model which is freshly generated from the tumors taken from pancreatic cancer patients and selected nine xenografts (six xenografts with p53-deficient and three xenografts with p53-wild type status) for this study. As shown in Figure 1A, tumors in vehicle-treated animals grew rapidly. Single agent MK-1775 treatment produced greater than 50% inhibition of tumor growth in two xenografts (PANC286 and PANC198). However, five of nine xenografts treated with GEM and six of nine xenografts treated with GEM plus MK-1775 produced complete tumor growth inhibition and in fact resulted tumor shrinkage compared to control and MK-1775 treated animals (Fig. 1A). These data suggest that single agent MK-1775 is unlikely to be effective in patients with PDA but that the combination of this agent with GEM has a substantial level of activity, and should be prioritized for clinical development.

Figure 1. Combination of MK-1775 and gemcitabine potentiates the efficacy of gemcitabine in established human pancreatic cancer xenografts.

Nine individual patient-derived low passage pancreatic cancer xenografts (three with wild type-p53 (WT) and six with deficient-p53 (MUT) were implanted in athymic mice. Animals with established tumors were dosed with MK-1775, GEM or a combination of GEM with MK-1775 as mentioned in the materials and methods. Tumor size was evaluated twice per week by caliper measurements. Relative tumor growth index (TGI) was calculated by relative tumor growth of treated mice (T) divided by relative tumor growth of control mice (C) x 100. (A) Efficacy of MK-1775, GEM and MK-1775 and GEM combination on the growth inhibition of pancreatic cancer xenografts. MK-1775 treatment produced greater than 50% inhibition of tumor growth in two xenografts (286, 198) compared to control tumors. Five of nine xenografts treated with GEM and six of nine xenografts treated with combination of GEM and MK-1775 produced complete tumor growth inhibition resulting in tumor shrinkage. Combination treatment caused greater than 50% regression in tumor size in four of six xenografts with p53-deficient tumors. Error bars represent SE. *** dennotes significance (P < 0.0001), ** denotes significance (P < 0.005), compared with GEM treated tumors. (B) Combination therapy leads to tumor regression in p53-deficient tumors. Tumors that regressed greater than 50% of its size upon treatment on day 28 were calculated. Error bars represent SE

Overall, none of the xenografts with p53-deficient status in the GEM treatment group produced 50% regression of initial tumor volume (Fig. 1A). However, combination of GEM and MK-1775 resulted in greater than 50% regression of initial tumor volume in four of six xenografts (66.66%) with p53-deficient status (Fig. 1A). The number of tumors that regressed more than 50% of its initial tumor size in each xenograft upon completion of treatment is provided in Table 1. Tumors with wild type-p53 status did not regress with treatments (Table 1). Among the xenografts with p53-deficient status, GEM alone treatment induced regression in 7 of 55 tumors (12.72%), while MK-1775 in combination with GEM induced regressions in 25 of 49 tumors (51.10%) in the six xenografts. Tumor growth regressions in GEM plus MK-1775 treated mice were found to be significant in PANC198 (P < 0.0001), PANC215 (P < 0.005) and PANC185 (P < 0.005) as compared to GEM treated mice. There was an overall 4.01 fold increase in total number of tumors regressed in the combination treatment group compared to GEM alone treatment (Fig. 1B). K-ras and SMAD4 status do not influence the tumor regression pattern in the xenografts (Table 1). One limitation of preclinical studies is that the threshold of activity that translates into positive clinical outcome is not known. Often, drugs are selected for clinical development base on tumor growth inhibition in preclinical models. As our experience with freshly generated PDA models increases and more comparison data is available, we are observing that indeed only agents that result in marked tumor regressions in this model have the potential to impact patient outcome. This is illustrated by our recent work on AZD0530 and nab-paclitaxel. AZD0530, a Src kinase inhibitor, induced only modest inhibition of tumor growth in PDA xenografts and, as expected, failed in a phase II clinical trial (27, 28). In contrast, nab-paclitaxel, in combination with GEM, resulted in marked tumor regression in this model, which successfully predicted a positive phase II study (29, 30).

Table 1.

Mutational status and number of tumors regressed morethan 50% of initial size as on day 28

| Xenograft | Genetic background | GEM | GEM + MK-1775 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P53 | K-ras | SMAD4 | |||

| PANC286 | WT | MUT | WT | 0 (8) | 0 (6) |

| PANC420 | WT | WT | WT | 0 (10) | 0 (8) |

| JH033 | WT | MUT | WT | 0 (8) | 0 (9) |

| PANC198 | MUT | MUT | MUT | 1 (8) | 8 (8) |

| PANC215 | MUT | MUT | WT | 1 (9) | 5 (7) |

| PANC185 | MUT | MUT | MUT | 1 (10) | 3 (8) |

| PANC281 | MUT | MUT | MUT | 3 (10) | 8 (10) |

| PANC354 | MUT | WT | MUT | 1 (10) | 0 (8) |

| PANC374 | MUT | MUT | WT | 0 (8) | 1 (8) |

|

| |||||

| Total with p53 MUT | 7/55 (12.72%) | 25/49 (51.10%) | |||

| Total with p53 WT | 0/26 (0%) | 0/23 (0%) | |||

Animals were treated with vehicle, MK-1775, GEM or GEM + MK-1775 for 4 weeks. Tumors that regressed greater than 50% of its size on day 28 in each xenograft were counted. Numbers in parenthesis denotes total number of tumors in that xenograft. Over all, 7of 55 (12.72%) tumors with p53-deficient (MUT) status regressed in the GEM treatment group. However, 25 of 49 (51.10%) of tumors with p53 MUT status regressed in the GEM + MK-1775 group. None of the tumors with p53-wild type (WT) regressed in GEM + MK-1775 (0 of 23) or GEM (0 of 26) treatment groups. K-ras and SMAD4 status do not influence the tumor regression pattern in these xenografts.

The selective augmentation of antitumor effects in tumors with deficient-p53 was anticipated based on the mechanism of action of the agent. Mammalian cells undergo cell cycle arrest in response to DNA damage due to the existence of multiple checkpoint response mechanisms. In response to DNA damage, the cell cycle halts, preventing the propagation of cells with damaged DNA. DNA damage culminates in the enforcement of cell cycle arrest, mainly at G1 and G2 phases. Checkpoint pathways operating at the G1 phase are frequently lost in cancer cells due to mutation of the p53 tumor suppressor gene. Cells lacking functional p53 would not be anticipated to arrest at the G1 checkpoint and would depend on the G2 checkpoint to permit DNA repair prior to undergoing mitosis. Thus, G2 checkpoint abrogation should preferentially kill p53-deficient cancer cells by removing the only checkpoint that protects these cells from premature entry into mitosis in response to DNA damage. Our data strongly suggest that the clinical development of MK-1775 with GEM should be restricted to patients with p53-deficient PDA.

Cdc2 initiates mitosis, which is the ultimate target of DNA replication and repair checkpoints. Chk1, Chk2, Wee1, and Myt1 are key regulators of G2 checkpoint, which act directly or indirectly to inhibit Cdc2 activity (17, 31). Chk1 and Chk2 are downstream effectors of ataxia telangiectasia-mutated kinase (ATM) and ataxia telangiectasia and Rad3-related kinase (ATR), which induce G2/M cell cycle arrest by inactivating Cdc25 tyrosine phosphatases through phosphorylation (32). Both Chk1 and Chk2 are known to phosphorylate Cdc25 on Ser216 and this phosphorylation makes Cdc25 functionally inactive (33). Cdc25 is required for removal of inhibitory phosphotyrosines on Cdc2/cyclin B1 kinase complexes that mediate entry into mitosis. On the other hand, the inhibitory phosphorylations at Thr-14 and Tyr-15 sites of Cdc2 are mediated by Myt1 and Wee1 kinases (34, 35). Wee1 is the major kinase phosphorylating the Tyr-15 site and Wee1 dependent phosphorylation of Cdc2 maintains the Cdc2/cyclin B1 complex in an inert form. While Myt1 preferentially phosphorylates the Thr-14 site, it can also phosphorylate the Tyr-15 site. Thus either Cdc25 inactivation and/or Wee1/Myt1 activation could contribute to G2 cell cycle arrest in response to DNA damage.

Chk1/2 inhibitors are in clinical development (36–38). A recent report indicated that Chk1 is required to maintain genome integrity and cell viability, and that p53-wild type cells are no less sensitive than p53-deficient cells to Chk1 inhibition in the presence of DNA damage. Thus, combining Chk1 inhibition with DNA damaging agents does not lead to preferential killing of p53-deficient over p53-wild type cells, and inhibiting Chk1 does not appear to be a promising approach for potentiation of cancer chemotherapy (39). Here we showed that Wee1 inhibition by MK-1775 could potentiate GEM sensitivity and tumor regressions, selectively in p53-deficient pancreatic cancer xenografts.

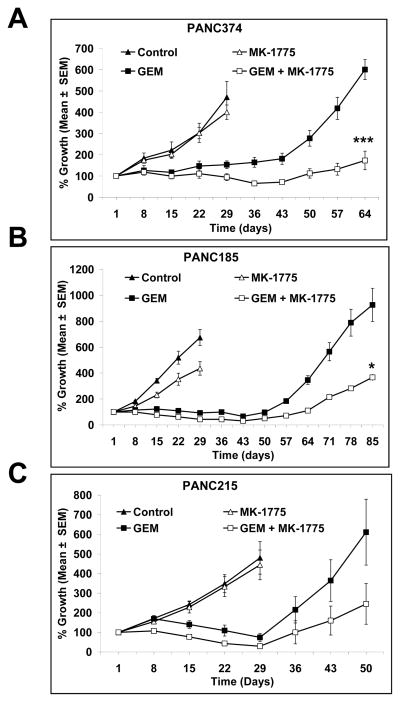

We were also interested in long-term tumor growth control and followed three xenografts after treatment for an extended period of time. Tumor re-growth data, as shown in Fig. 2 suggest that not only does the combination of GEM with MK-1775 lead to synergistic tumor growth inhibition, but the effect of the combination therapy is also longer-lasting than that seen with GEM alone (Fig. 2A, B and C). It was noteworthy, however, that tumors eventually recur, albeit at a slower pace.

Figure 2. MK-1775 synergize with gemcitabine to inhibit tumor growth of human pancreatic cancer xenografts.

Animals were dosed with MK-1775, GEM or a combination of GEM with MK-1775 for 4 weeks as mentioned in the materials and methods. Tumor growth curves of (A) PANC374, (B) PANC185 and (C) PANC215 suggest that the combination of MK-1775 and GEM lead to synergistic growth inhibition. Tumors in the vehicle and MK-1775 treated animals grew progressively and were sacrificed on day 28 due to tumor burden. Animals in the GEM and combination of GEM with MK-1775 were kept longer after the 4 week treatment. Combination of GEM with MK-1775 slowed the tumor growth progression compared to GEM alone treated animals. Points, mean (n = 8 to 10 tumors per group); bars, SE. Error bars represent SE. *** dennotes significance (P < 0.0001), * denotes significance (P < 0.01), compared with GEM treated tumors.

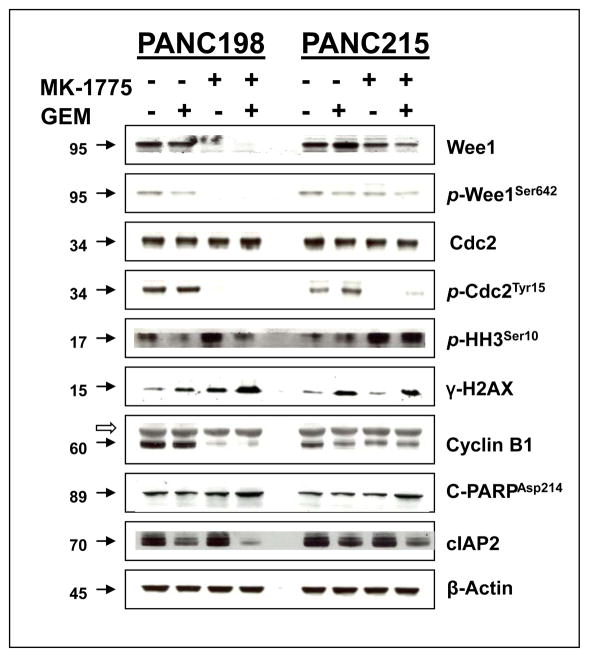

In order to determine the target modulation by MK-1775, we examined Wee1, Cdc2 and their phosphorylated forms in post treatment tumor specimens. MK-1775 treatment strongly inhibited phosphorylation of Tyr-15 of Cdc2, the primary substrate of Wee1 (Fig. 3, 4A and C), suggesting increased Cdc2 kinase activity. In addition, the Wee1 protein was consistently reduced by MK-1775 treatment as shown by western blotting (Fig. 3), likely due to degradation of Wee1 as MK-1775 treatment activates Cdc2 which in turn phosphorylates Wee1, ultimately leading to its ubiquitin-proteasome dependent destruction (40).

Figure 3. Combination of MK-1775 and gemcitabine inhibits Wee1 and attenuates Cdc2 phosphorylation to promote mitotic entry and apoptosis.

Tumor lysates collected from vehicle, GEM, MK-1775 and combination of GEM with MK-1775 treated mice were resolved in SDS-PAGE and probed with specific antibodies against indicated proteins. MK-1775 as well as combination of MK-1775 and GEM treatment strongly inhibit Wee1 and phospho Cdc2. Combination of MK-1775 and GEM treatment up-regulate the expression of p-HH3, γ-H2AX and cleaved PARP. Upon combination with GEM, MK-1775 down regulate the expression of cIAP2 as compared to GEM. MK-1775 as well as combination of MK-1775 and GEM treatment strongly inhibit the Cyclin B1 expression as compared to control and GEM treatment of PANC198. Filled arrowheads indicate the molecular weight of corresponding proteins (KD). The empty arrowhead indicates the presence of a non-specific band in Cyclin B1. β-actin was used as a loading control.

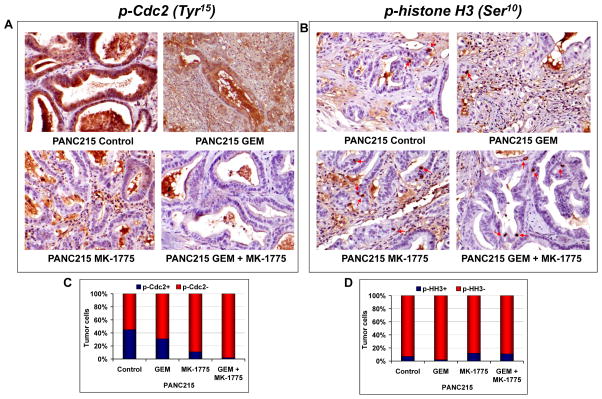

Figure 4. Immunohistochemical staining of phospho-Cdc2 and phospho-histone H3.

(A) Representative micrographs of p-Cdc2 from PANC215 showing high immunoreactivity for p-Cdc2 in the vehicle and GEM treated tumors. MK-1775 and combination treatment greatly inhibited the p-Cdc2 compared to vehicle and GEM treated tumors (left panel). There was a 45 and 31% of tumor cells were stained positive for p-Cdc2 in the control and GEM treated tumors, respectively, while only 11 (P = 0.0061 compared to GEM treated tumors) and 2% (P < 0.0001 compared to GEM treated tumors) of tumor cells were stained positive for p-Cdc2 in the MK-1775 and combination of MK-1775 and GEM treated tumors respectively. (B) Representative micrographs of p-histone H3, a marker of mitosis, from PANC215 were shown in the right panel. Number of p-histone H3 stained tumor cells were elevated in the MK-1775 and combination of MK-1775 and GEM treated tumors as compared to control and GEM treated tumors. There was a 7 and 2% of tumor cells were stained positive for p-histone H3 in the control and GEM treated tumors, respectively, while 12 (P = 0.0115 compared to GEM treated tumors) and 11% (P = 0.0201 compared to GEM treated tumors) of tumor cells were stained positive for p-histone H3 in the MK-1775 and combination of MK-1775 and GEM treated tumors respectively. (C) Histogram showing the number of positively stained p-Cdc2 tumor cells over total number of tumor cells. (D) Histogram showing the number of positively stained p-HH3 tumor cells over total number of tumor cells.

To determine whether combination therapy promotes mitotic entry, we measured the expression of phospho histone H3 by western blot as well as by immunohistochemistry. When administered in combination with GEM, MK-1775 promoted mitotic entry as measured by enhanced phospho histone H3 expression (Fig. 3, 4B and D). In addition, the combined treatment resulted in the up-regulation of C-PARP as well as down regulation of cIAP2, suggesting that combination therapy facilitates apoptotic death of tumor cells (Fig. 3). GEM, as a chain terminator, requires an active cell cycle to be effective for inhibiting tumor growth, and might induce cell cycle halt and enforce cell cycle checkpoints, which may play an important role in escalating the resistance to therapy. Thus, there is a strong rationale in combining checkpoint inhibitors with GEM as a means to enhance tumor response (41, 42). Here we showed that GEM induces G2 arrest, which correlates with an increased Cdc2 inhibitory phosphorylation at Tyr-15 and prevents mitotic entry as evidenced by decreased p-HH3Ser10 (Fig 4B and D). However, the decreased Cdc2 inhibitory phosphorylation at Tyr-15 caused by MK-1775 treatment indicates that MK-1775 has the ability to abrogate the G2 arrest induced by GEM and promote mitotic entry as demonstrated by enhanced phospho histone H3 at Ser-10 (Fig 4B and D). Cyclin B1 was examined as a marker of G2 phase (43). Expression of Cdc2 was not altered by treatments, while the expression of Cyclin B1 was strongly inhibited by MK-1775 as well as combination of MK-1775 and GEM treatment compared to control and GEM treated tumors of PANC198 (Figure 3). Loss of Cyclin B1 accumulation in the MK-1775 as well as combination of MK-1775 and GEM treated tumors indicate the exit from G2 phase arrest (Figure 3). The levels of γ-H2AX were used as a surrogate for unrepaired DNA damage (44). γ-H2AX expression was clearly elevated in the combination of MK-1775 and GEM treatment group compared to GEM treated tumors of PANC198, indicating the persistence of unrepaired DNA damage in the tumors (Figure 3). Overall, in addition to providing mechanistic support to the observations made above, the data provides important clues for potential biomarkers for clinical development of this drug combination.

In conclusion, our results provide compelling evidence that MK-1775 treatment leads to the inhibition and subsequent loss of Wee1 and activation of its substrate, Cdc2. The MK-1775 and GEM combination promoted the mitotic entry of tumor cells and eventually led to apoptotic death, and delayed the tumor progression compared to the GEM treatment. These findings have important clinical implications and raise the hope for potential therapeutic benefit to many PDA patients whose cancer cells are deficient for p53 function.

Translational Relevance.

Treatment efficacy of DNA damaging agents is determined not only by the amount of therapy-induced DNA damage but also by the capacity of tumor cells to repair the damaged DNA. The G2 DNA damage checkpoint ensures maintenance of cell viability by delaying progression into mitosis when cells have suffered DNA damage. Wee1 is a cellular protein kinase which inhibits Cdc2 activity, thereby preventing cells from proceeding through mitosis by maintaining G2 arrest. MK-1775 is the first reported Wee1 inhibitor with high potency, selectivity and oral bioavailability in preclinical animal models, and is currently being evaluated in several phase I clinical trials. Here we provide compelling evidence that MK-1775 synergizes with gemcitabine to achieve tumor regressions, selectively in p53-deficient pancreatic cancer xenografts. These results may help to frame clinical investigation of Wee1 inhibitors along with chemotherapy to benefit pancreatic cancer patients whose tumor cells are devoid of functional p53 gene.

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: Merck Research Laboratories as well as NIH Grants CA116554 and CA129963 to Manuel Hidalgo

Footnotes

Note: Presented in part at AACR-NCI- EORTC International Conference on Molecular Targets and Cancer Therapeutics: Nov 15-19, 2009, Boston, MA. (Abstract # A251).

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest: M. Hidalgo received funding from Merck Research Laboratories. J. Watters, D. Brooks, T. Demuth, SD. Shumway, S. Mizuarai, and H. Hirai are employees of Merck. The other authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2009. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59:225–49. doi: 10.3322/caac.20006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li D, Abbruzzese JL. New strategies in pancreatic cancer: emerging epidemiologic and therapeutic concepts. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:4313–8. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burris HA, 3rd, Moore MJ, Andersen J, et al. Improvements in survival and clinical benefit with gemcitabine as first-line therapy for patients with advanced pancreas cancer: a randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:2403–13. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.6.2403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moore MJ, Goldstein D, Hamm J, et al. Erlotinib plus gemcitabine compared with gemcitabine alone in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: a phase III trial of the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1960–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.9525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van Cutsem E, Vervenne WL, Bennouna J, et al. Phase III trial of bevacizumab in combination with gemcitabine and erlotinib in patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2231–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.0238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McGinn CJ, Zalupski MM, Shureiqi I, et al. Phase I trial of radiation dose escalation with concurrent weekly full-dose gemcitabine in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:4202–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.22.4202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hidalgo M. Pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1605–17. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0901557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kawabe T. G2 checkpoint abrogators as anticancer drugs. Mol Cancer Ther. 2004;3:513–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elledge SJ. Cell cycle checkpoints: preventing an identity crisis. Science. 1996;274:1664–72. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5293.1664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sancar A, Lindsey-Boltz LA, Unsal-Kacmaz K, Linn S. Molecular mechanisms of mammalian DNA repair and the DNA damage checkpoints. Annu Rev Biochem. 2004;73:39–85. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.073723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhou BB, Elledge SJ. The DNA damage response: putting checkpoints in perspective. Nature. 2000;408:433–9. doi: 10.1038/35044005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goi K, Takagi M, Iwata S, et al. DNA damage-associated dysregulation of the cell cycle and apoptosis control in cells with germ-line p53 mutation. Cancer Res. 1997;57:1895–902. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levine AJ. p53, the cellular gatekeeper for growth and division. Cell. 1997;88:323–31. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81871-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jin P, Gu Y, Morgan DO. Role of inhibitory CDC2 phosphorylation in radiation-induced G2 arrest in human cells. J Cell Biol. 1996;134:963–70. doi: 10.1083/jcb.134.4.963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McGowan CH, Russell P. Cell cycle regulation of human WEE1. Embo J. 1995;14:2166–75. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07210.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hashimoto O, Shinkawa M, Torimura T, et al. Cell cycle regulation by the Wee1 inhibitor PD0166285, pyrido [2,3-d] pyimidine, in the B16 mouse melanoma cell line. BMC Cancer. 2006;6:292. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-6-292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang Y, Decker SJ, Sebolt-Leopold J. Knockdown of Chk1, Wee1 and Myt1 by RNA interference abrogates G2 checkpoint and induces apoptosis. Cancer Biol Ther. 2004;3:305–13. doi: 10.4161/cbt.3.3.697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hirai H, Arai T, Okada M, et al. MK-1775, a small molecule Wee1 inhibitor, enhances anti-tumor efficacy of various DNA-damaging agents, including 5-fluorouracil. Cancer Biol Ther. 2010:9. doi: 10.4161/cbt.9.7.11115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hirai H, Iwasawa Y, Okada M, et al. Small-molecule inhibition of Wee1 kinase by MK-1775 selectively sensitizes p53-deficient tumor cells to DNA-damaging agents. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009;8:2992–3000. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leijen S, Beijnen JH, Schellens JH. Abrogation of the G2 checkpoint by inhibition of Wee-1 kinase results in sensitization of p53-deficient tumor cells to DNA-damaging agents. Curr Clin Pharmacol. 2010;5:186–91. doi: 10.2174/157488410791498824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mizuarai S, Yamanaka K, Itadani H, et al. Discovery of gene expression-based pharmacodynamic biomarker for a p53 context-specific anti-tumor drug Wee1 inhibitor. Mol Cancer. 2009;8:34. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-8-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Redston MS, Caldas C, Seymour AB, et al. p53 mutations in pancreatic carcinoma and evidence of common involvement of homocopolymer tracts in DNA microdeletions. Cancer Res. 1994;54:3025–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rubio-Viqueira B, Jimeno A, Cusatis G, et al. An in vivo platform for translational drug development in pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:4652–61. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jones S, Zhang X, Parsons DW, et al. Core signaling pathways in human pancreatic cancers revealed by global genomic analyses. Science. 2008;321:1801–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1164368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bankert RB, Egilmez NK, Hess SD. Human-SCID mouse chimeric models for the evaluation of anti-cancer therapies. Trends Immunol. 2001;22:386–93. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(01)01943-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rubio-Viqueira B, Hidalgo M. Direct in vivo xenograft tumor model for predicting chemotherapeutic drug response in cancer patients. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2009;85:217–21. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2008.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rajeshkumar NV, Tan AC, De Oliveira E, et al. Antitumor effects and biomarkers of activity of AZD0530, a Src inhibitor, in pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:4138–46. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-3021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nallapareddy S, Arcaroli J, Touban B, et al. A phase II trial of saracatinib (AZD0530), an oral Src inhibitor, in previously treated metastatic pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(Suppl):abstract e14515. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maitra A, Rajeshkumar NV, Rudek M, et al. nab®-paclitaxel targets tumor stroma and results, combined with gemcitabine, in high efficacy against pancreatic cancer models. 21st AACR-NCI- EORTC International Conference on Molecular Targets and Cancer Therapeutics 2009; p. abstract C246. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Von Hoff DD, Ramanathan M, Board M, et al. SPARC correlation with response to gemcitabine (G) plus nab-paclitaxel (nab-P) in patients with advanced metastatic pancreatic cancer: A phase I/II study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(Suppl):abstract 4525. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chaturvedi P, Eng WK, Zhu Y, et al. Mammalian Chk2 is a downstream effector of the ATM-dependent DNA damage checkpoint pathway. Oncogene. 1999;18:4047–54. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bartek J, Lukas J. Chk1 and Chk2 kinases in checkpoint control and cancer. Cancer Cell. 2003;3:421–9. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00110-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sanchez Y, Wong C, Thoma RS, et al. Conservation of the Chk1 checkpoint pathway in mammals: linkage of DNA damage to Cdk regulation through Cdc25. Science. 1997;277:1497–501. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5331.1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Booher RN, Holman PS, Fattaey A. Human Myt1 is a cell cycle-regulated kinase that inhibits Cdc2 but not Cdk2 activity. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:22300–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.35.22300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Parker LL, Sylvestre PJ, Byrnes MJ, 3rd, Liu F, Piwnica-Worms H. Identification of a 95-kDa WEE1-like tyrosine kinase in HeLa cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:9638–42. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.21.9638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morgan MA, Parsels LA, Zhao L, et al. Mechanism of radiosensitization by the Chk1/2 inhibitor AZD7762 involves abrogation of the G2 checkpoint and inhibition of homologous recombinational DNA repair. Cancer Res. 2010;70:4972–81. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dai Y, Grant S. New insights into checkpoint kinase 1 in the DNA damage response signaling network. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:376–83. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Perona R, Moncho-Amor V, Machado-Pinilla R, Belda-Iniesta C, Sanchez Perez I. Role of CHK2 in cancer development. Clin Transl Oncol. 2008;10:538–42. doi: 10.1007/s12094-008-0248-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zenvirt S, Kravchenko-Balasha N, Levitzki A. Status of p53 in human cancer cells does not predict efficacy of CHK1 kinase inhibitors combined with chemotherapeutic agents. Oncogene. 2010 doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Watanabe N, Arai H, Nishihara Y, Taniguchi M, Hunter T, Osada H. M-phase kinases induce phospho-dependent ubiquitination of somatic Wee1 by SCFbeta-TrCP. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:4419–24. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307700101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhou BB, Bartek J. Targeting the checkpoint kinases: chemosensitization versus chemoprotection. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:216–25. doi: 10.1038/nrc1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Matthews DJ, Yakes FM, Chen J, et al. Pharmacological abrogation of S-phase checkpoint enhances the anti-tumor activity of gemcitabine in vivo. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:104–10. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.1.3699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Scott IS, Morris LS, Rushbrook SM, et al. Immunohistochemical estimation of cell cycle entry and phase distribution in astrocytomas: applications in diagnostic neuropathology. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2005;31:455–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2005.00618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Morgan MA, Meirovitz A, Davis MA, Kollar LE, Hassan MC, Lawrence TS. Radiotherapy combined with gemcitabine and oxaliplatin in pancreatic cancer cells. Transl Oncol. 2008;1:36–43. doi: 10.1593/tlo.07106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]