Abstract

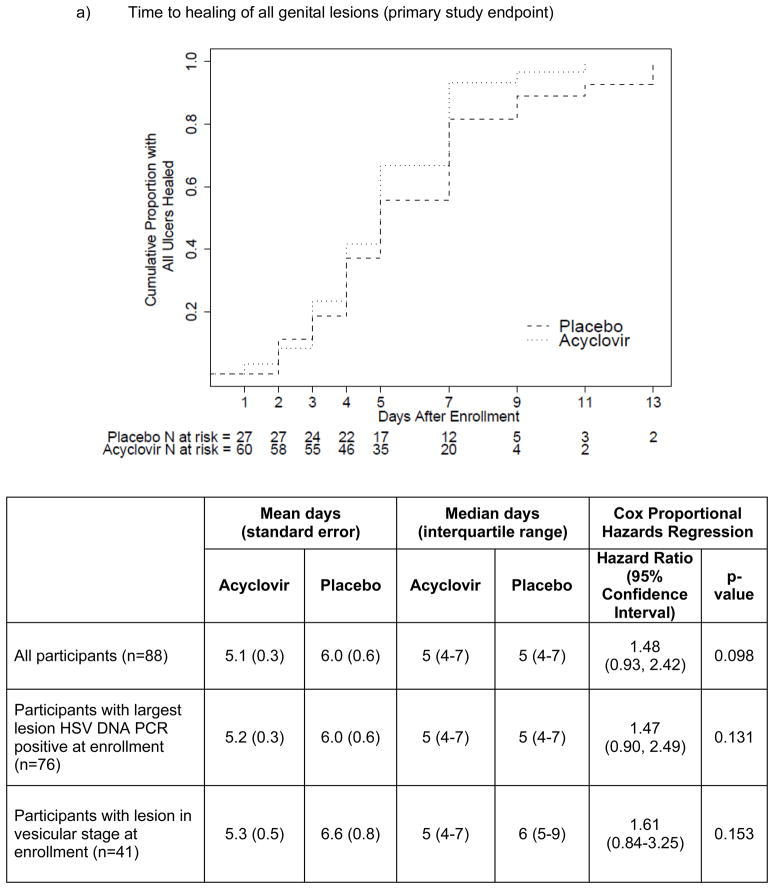

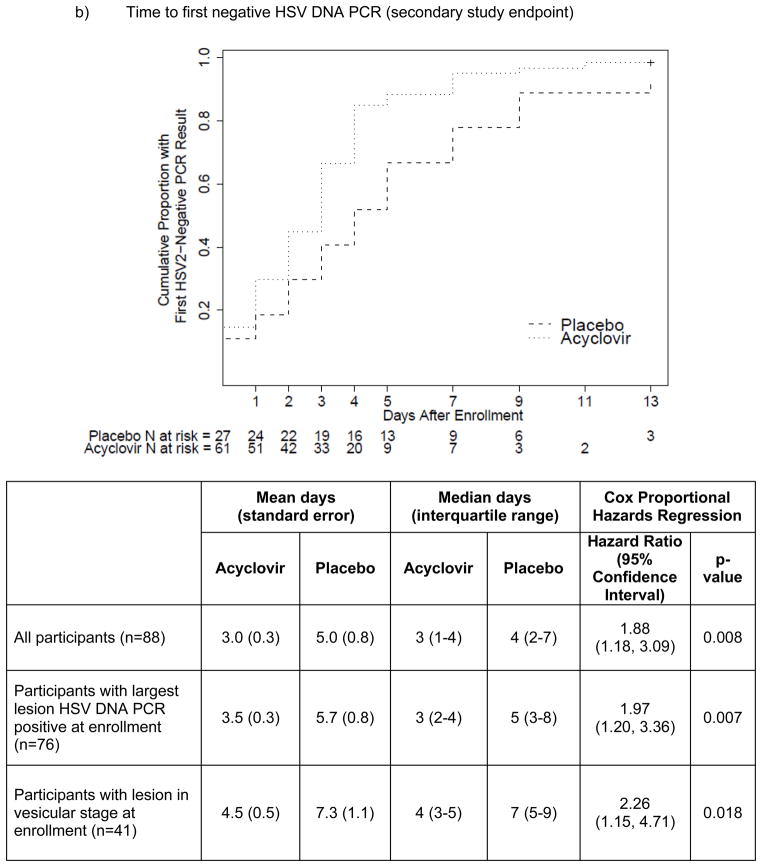

In a randomized trial among African women with recurrent genital herpes, episodic acyclovir therapy resulted in modestly greater likelihood of lesion healing (HR=1.48, p=0.098; mean 5.1 vs. 6.0 days) and cessation of HSV shedding (HR=1.88, p=0.008; mean 3.0 vs. 5.0 days) compared with placebo, similar to results from high-income countries. (ClinicalTrials.gov registration NCT00808405).

Keywords: herpes simplex virus, acyclovir, HSV shedding, women, Africa, genital herpes

The seroprevalence of herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2), the primary etiology of genital herpes, exceeds 50% in African women, and HSV-2 increases a woman’s HIV-1 acquisition risk by 3-fold 1. However, two randomized trials of acyclovir HSV-2 suppressive therapy (using a dose of 400 mg twice daily) failed to demonstrate protection against HIV-1 acquisition in high-risk, HIV-1 seronegative populations 2,3. In one of these trials (HIV Prevention Trials Network [HPTN] study 039), among HIV-1 seronegative, HSV-2 seropositive men who have sex with men from the Americas and women from Africa, acyclovir reduced recurrent genital ulcers due to HSV-2 by only 63% 3, lower than had been seen in previous studies of suppressive acyclovir from high-income settings 4, and the effect of acyclovir on frequency of genital ulcers and quantity of HSV-2 DNA in specimens collected from ulcers was less in the African participants than in those from the US 5. One potential explanation for these findings is that African women with HSV-2 have diminished response to acyclovir therapy, compared to populations from high-income settings. To test this hypothesis, we conducted a randomized, placebo-controlled trial of clinical and virologic response to episodic acyclovir therapy among HIV-1 uninfected, HSV-2 seropositive African women with recurrent genital herpes.

Study design and methods

Between January and December 2009, women from Johannesburg, South Africa and Lusaka, Zambia who had participated in HPTN 039 were invited to present to the HPTN 039 clinics if they had a new genital ulcer. These women, as well as others who had not participated in HPTN 039 but who presented with recurrent genital herpes during the recruitment period, were offered study participation. Eligible women were aged 18–50 years, HIV-1 seronegative, and HSV-2 seropositive; exclusion criteria included pregnancy or use of anti-HSV medications.

Women were randomly assigned in a 2:1 fashion to acyclovir 400 mg orally three times daily for five days or matching placebo (Carlsbad Laboratories, San Diego, USA). This dosage and duration of acyclovir therapy is recommended by WHO and CDC for treatment of recurrent genital herpes 6,7; however, episodic therapy for recurrent genital herpes had not been implemented as standard practice in South Africa or Zambia. Study clinicians and participants were blinded to treatment assignments, and participants were counseled that episodic therapy is not curative for HSV-2 and that they may have been assigned to placebo. Women returned to the study clinic daily for 5 days and then every other day for 8 days (for a total of 9 visits over 13 days of follow-up). A swab for HSV PCR from the largest lesion site was obtained at each visit. The protocol was approved by institutional review boards at the University of Washington and the collaborating study sites. Participants provided written informed consent. The trial was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT00808405).

HIV-1 serostatus was by paired rapid assay. HSV-2 serostatus was determined either by ELISA (HerpeSelect-2, Focus Technologies), performed at local laboratories and using an index value >3.4 to define a positive result 3, or, for women who had earlier participated in HPTN 039, by HSV Western blot 3. Swabs from the largest lesion site were tested in batch at the end of the study at the University of Washington by HSV DNA PCR, with a lower limit of HSV detection was 150 (2.18 log10) copies/swab 8.

The primary study endpoint was time to complete healing of all genital lesions, defined as re-epithelialization of skin. A pre-defined secondary endpoint was time to first negative HSV DNA PCR result. A sample size of 90 was estimated to provide 80% power to detect a 1.8 day difference between acyclovir and placebo in time to healing. Comparisons of acyclovir and placebo groups were calculated by an intent-to-treat approach using Cox proportional hazards regression and Kaplan-Meier estimation. Data were unblinded after all follow-up and laboratory testing were complete. Analyses were performed using SAS 9.2 and R v2.11.1.

Population and results

Eighty-eight HIV-1 negative, HSV-2 seropositive women were randomized – 61 to the acyclovir arm and 27 to the placebo arm (Table 1). An additional 7 women who had genital lesions were enrolled but were subsequently determined to be HSV-2 seronegative and were excluded from all analyses. Most women (76/88, 86.4%) had participated in HPTN 039. The median number of lesions was 1 (interquartile range [IQR] 1–3), the median duration of genital symptoms was 1 day (IQR 1–2), and >90% of lesions were in ulcerative or vesicular stages. At enrollment, 76 women (86.4%) had HSV DNA detected by PCR.

Table 1.

Participant enrollment characteristics.

| Median (IQR) or n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Acyclovir N=61 | Placebo N=27 | |

| Age, years | 38 (30–46) | 40 (28–47) |

| Study site | ||

| Johannesburg | 30 (49.2%) | 14 (51.9%) |

| Lusaka | 31 (50.8%) | 13 (48.1%) |

| Participation in HPTN 039 | ||

| Acyclovir arm | 20 (32.8%) | 11 (40.7%) |

| Placebo arm | 30 (49.2%) | 15 (55.6%) |

| Did not participate in HPTN 039 | 11 (18.0%) | 1 (3.7%) |

| Self-reported genital lesions in the 3 months prior to study | 47 (77.0%) | 20 (74.1%) |

| CHARACTERISTICS OF GENITAL LESIONS | ||

| Duration of symptoms (days) | 1 (1–2) | 1 (1–2) |

| Total number of lesions | 1 (1–2) | 1 (1–3) |

| Description of largest lesion | ||

| Erythema | 1 (1.6%) | 0 (0%) |

| Papule | 3 (4.9%) | 0 (0%) |

| Vesicle | 27 (44.3%) | 14 (51.9%) |

| Ulcer | 30 (49.2%) | 13 (48.1%) |

| Crust | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Size of largest lesion, mm | 6 (4–8) | 5 (4–7) |

| Largest lesion location | ||

| Labia/periurethral/mons/introitus | 43 (70.5%) | 17 (63.0%) |

| Buttock/perianal | 18 (29.5%) | 10 (37.0%) |

| HSV DNA detected by PCR from largest lesion | 52 (85.2%) | 24 (88.9%) |

| HSV DNA quantity (log10 copies/swab), among those with HSV DNA detected | 5.40 (3.64–6.96) | 5.17 (3.89–6.84) |

Eighty-five women (96.6%, 59 acyclovir/26 placebo) completed the 13-day follow-up, and, excluding days that participants were unable to attend because of weekend and holiday site closures, 596 of 610 (97.7%) scheduled follow-up visits were attended (410/423 [96.9%] acyclovir, 186/187 [99.5%] placebo). Three participants (2 acyclovir, 1 placebo) each reported missing one dose of study medication during the 5 days of three times daily study medication. By day 13, all participants had achieved complete healing of all genital lesions.

The time to reaching the primary (healing of all lesions) and secondary (first negative HSV DNA PCR) endpoints was shorter for those randomized to acyclovir compared with placebo (Figure 1), although the primary endpoint did not achieve statistical significance. By Cox proportional hazards analysis, acyclovir resulted in 1.48-fold (p=0.098; mean 5.1 vs. 6.0 days) greater likelihood of healing of all lesions and 1.88-fold (p=0.008; mean 3.0 vs. 5.0 days) greater likelihood of cessation of HSV shedding. The magnitude of these effects was similar among the subset of women whose genital swab was HSV DNA PCR positive at the enrollment visit and was modestly greater among those whose genital lesion was in vesicular stage at enrollment.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves, with log-rank p-values, and time-to-event analyses, for a) primary (time to healing of all genital lesions) and b) secondary (time to first negative HSV DNA PCR) study endpoints.

Conclusions

In this randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, with frequent measurements of clinical and virologic response over 13 days of follow-up, we demonstrated that a standard 5-day course of oral acyclovir modestly shortens time to lesion healing and to cessation of HSV-2 shedding among HIV-1 seronegative, HSV-2 seropositive African women with recurrent genital herpes. Our results, including a greater effect on HSV shedding than clinical healing, are consistent with findings from studies from high-income settings of treatment of recurrent genital herpes, which found that acyclovir improved healing and time to cessation of shedding by 1–2 days 9–11. The clinical and virologic course in the placebo arm was compatible with the natural history of genital herpes in other populations, and, as would be expected for an immunocompetent population, all lesions were healed by 13 days.

Our results argue that diminished virologic response to acyclovir among African women does not explain the failure of HSV-2 suppressive therapy to prevent HIV-1 acquisition in two clinical trials 2,3. Lack of adherence to acyclovir has been proposed as an alternative explanation, but adherence was high in HPTN 039 3. One intriguing hypothesis for the failure HSV-2 suppression to reduce HIV-1 risk is that HSV-2 reactivation is associated with an dense and persistent infiltration of HIV-1 receptor cells in the genital mucosa 12, suggesting that highly potent and durable HSV-2 suppressive therapies might be needed to intervene on HSV-2 to reduce HIV-1 risk.

Not all studies from Africa have found an effect of acyclovir on healing of genital herpes lesions. Potential explanations that may account for these differences include that most previous trials were primarily among HIV-1 infected persons, episodic treatment was started later (after an average of one week of symptoms) and follow-up schedules in those studies may have been too infrequent to detect the 1–2 day benefit observed in the present study 13–15. However, among South African men with HIV-1 who presented early with genital ulcers, acyclovir improved healing by a median of 3 days and reduced HIV-1 shedding 13. Most women in our study had previously participated in HPTN 039 and were aware of their HSV-2 serostatus; they presented early, with a median of one day of symptoms and >90% of lesions in vesicular or ulcerative stages. This is encouraging in terms of the value of counseling HSV-2 seropositive persons about clinical manifestations of genital herpes and the importance of early initiation of episodic acyclovir or the possibility of suppressive acyclovir, where available.

In summary, we found that HSV-2 seropositive, HIV-1 uninfected African women with recurrent genital herpes had a similar virologic and clinical response to acyclovir as was seen previously in immunocompetent populations from North America and Europe. Genital herpes accounts for the vast majority of genital ulcer disease in sub-Saharan Africa, where diagnostic tests for HSV are rarely available. Although acyclovir is available as a generic preparation, is on the WHO List of Essential Drugs for developing countries, and is recommended by WHO for syndromic management of genital ulcer disease 6, cost and availability have limited its use in Africa 16. Our results demonstrate that there are modest clinical and virologic benefits of acyclovir for recurrent genital herpes when initiated promptly after lesions develop, emphasizing its potential when included as part of first-line syndromic management of genital ulcers.

Acknowledgments

We thank the study staff for their efforts and Dr. Meei-Li Huang and the University of Washington Virology Laboratory for HSV PCR testing. We are grateful to the study participants for their time and dedication.

Sponsorship: This study was supported by the US National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (U01 AI52054 and P01 AI30731) and by the HIV Prevention Trials Network (HPTN) under Cooperative Agreement U01 AI46749, sponsored by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institute of Drug Abuse, National Institute of Mental Health, and Office of AIDS Research.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest:

LC has received consulting fees from AiCuris, which is developing treatments for HSV and cytomegalovirus infections, is listed as a coinventor on several patents describing antigens and epitopes to which T-cell responses to HSV-2 are directed (these proteins have the potential to be used in candidate vaccines against HSV), and has received fees for serving as the head of the scientific advisory board of Immune Design, including equity shares that are less than 1% ownership. AW has received consulting fees from AiCuris. AW and CC have received research grant support from GlaxoSmithKline. All other authors declare they have no known conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Freeman EE, Weiss HA, Glynn JR, et al. Herpes simplex virus 2 infection increases HIV acquisition in men and women: systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. AIDS. 2006;20:73–83. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000198081.09337.a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Watson-Jones D, Weiss HA, Rusizoka M, et al. Effect of herpes simplex suppression on incidence of HIV among women in Tanzania. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1560–71. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0800260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Celum C, Wald A, Hughes J, et al. Effect of aciclovir on HIV-1 acquisition in herpes simplex virus 2 seropositive women and men who have sex with men: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;371:2109–19. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60920-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gupta R, Wald A, Krantz E, et al. Valacyclovir and acyclovir for suppression of shedding of herpes simplex virus in the genital tract. J Infect Dis. 2004;190:1374–81. doi: 10.1086/424519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fuchs J, Celum C, Wang J, et al. Clinical and virologic efficacy of herpes simplex virus type 2 suppression by acyclovir in a multicontinent clinical trial. J Infect Dis. 2010;201:1164–8. doi: 10.1086/651381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization. Guidelines for the management of sexually transmitted infections. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines, 2006. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006;55:1–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jerome KR, Huang ML, Wald A, et al. Quantitative stability of DNA after extended storage of clinical specimens as determined by real-time PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:2609–11. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.7.2609-2611.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nilsen AE, Aasen T, Halsos AM, et al. Efficacy of oral acyclovir in the treatment of initial and recurrent genital herpes. Lancet. 1982;2:571–3. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(82)90658-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bryson YJ, Dillon M, Lovett M, et al. Treatment of first episodes of genital herpes simplex virus infection with oral acyclovir. A randomized double-blind controlled trial in normal subjects. N Engl J Med. 1983;308:916–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198304213081602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bavaro JB, Drolette L, Koelle DM, et al. One-day regimen of valacyclovir for treatment of recurrent genital herpes simplex virus 2 infection. Sex Transm Dis. 2008;35:383–6. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31815e4190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhu J, Hladik F, Woodward A, et al. Persistence of HIV-1 receptor-positive cells after HSV-2 reactivation is a potential mechanism for increased HIV-1 acquisition. Nat Med. 2009;15:886–92. doi: 10.1038/nm.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paz-Bailey G, Sternberg M, Puren AJ, et al. Improvement in healing and reduction in HIV shedding with episodic acyclovir therapy as part of syndromic management among men: a randomized, controlled trial. J Infect Dis. 2009;200:1039–49. doi: 10.1086/605647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Phiri S, Hoffman IF, Weiss HA, et al. Impact of aciclovir on ulcer healing, lesional, genital and plasma HIV-1 RNA among patients with genital ulcer disease in Malawi. Sex Transm Infect. 2010;86:345–52. doi: 10.1136/sti.2009.041814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mayaud P, Legoff J, Weiss HA, et al. Impact of acyclovir on genital and plasma HIV-1 RNA, genital herpes simplex virus type 2 DNA, and ulcer healing among HIV-1-infected African women with herpes ulcers: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. J Infect Dis. 2009;200:216–26. doi: 10.1086/599991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Corbell C, Stergachis A, Ndowa F, et al. Genital ulcer disease treatment policies and access to acyclovir in eight sub-Saharan African countries. Sex Transm Dis. 2010;37:488–93. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181e212e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]