Abstract

One of the main challenges of developing an HIV-1 vaccine lies in eliciting immune responses that can overcome the antigenic variability exhibited by HIV. Most HIV vaccine development has focused on inducing immunity to conserved regions of the HIV envelope; however, new studies of the sequence-variable regions of the HIV-1 gp120 envelope glycoprotein have shown that there are conserved immunological and structural features in these regions. Recombinant immunogens that include these features may provide the means to address the antigenic diversity of HIV-1 and induce protective antibodies that can prevent infection with HIV-1.

The gp120 and gp41 glycoproteins of the HIV envelope (Env) are targets of antibodies that inhibit virus infectivity, and attempts to induce these antibodies with a prophylactic HIV vaccine have used various approaches. The failure of early gp120 protein-based vaccines to induce neutralizing antibodies1 redirected attention to the cellular arm of the immune response. The subsequent failure of a T cell-based vaccine2 left the HIV-1 vaccine field at a crossroads, with the direction forward uncertain. Recently, a dual component HIV-1 vaccine, in which priming with a recombinant canarypox vector was followed by boosts with two recombinant gp120 proteins, imparted a measure of protection from infection3. Protection in this trial may have been due to antibodies4, but the nature and specificity of the protective antibodies, and how to design immunogens that induce higher and more persistent levels of protection remains unresolved.

The difficulties of HIV-1 vaccine research are, in part, a result of its extreme antigenic variation. Conventional wisdom suggests that “constant” rather than “variable” regions of Env should be targeted to elicit broad responses against antigenically diverse HIV strains. However these regions were classified in early studies on the basis of the sequences of only a few virus strains5. Immunological and 3D structural studies of the Env of diverse strains have now revealed higher order structural features that would alter these early classifications and explain how antibodies specific for some variable regions have neutralization activity for diverse viruses. Although several epitopes that induce neutralizing antibodies have been identified in conserved regions of both the gp120 and gp41 portions of Env, inducing neutralizing antibodies that target these epitopes using rationally designed immunogens has, so far, proven difficult6–9. Moreover, although a vigorous antibody response is induced by infection, only a minority of individual HIV+ patient sera neutralize a broad spectrum of HIV strains10,11.

We believe that targeting conserved elements within the immunogenic sequence-variable Env regions (Figure 1) using rationally designed immunogens is promising, but inducing broad, cross-strain neutralizing antibodies specific for these regions is a challenge. Nevertheless, current evidence suggests that 3D visualization might identify invariant epitopes capable of inducing protective antibodies that are hidden within the sequence variable Env regions. Indeed, this perspective provides a rational basis for understanding the documented immunological cross-reactivity of many monoclonal antibodies targeting the second (V2) and third (V3) variable loops of gp120, and the quaternary neutralization epitopes (QNEs) formed by V2 and V3 (Box 1 and Table 1). In hindsight, this perspective is a logical outgrowth of classic immunochemical studies12 showing that cross-reactive antibodies recognize antigens that are related but not identical in sequence (as for example with anti-V2 monoclonal antibodies that recognize gp120 monomers derived from diverse primary isolates of HIV-113). These old but seminal studies support a new paradigm for HIV-1 immunogen design.

Figure 1.

A. Ribbon diagram of the crystallographic structure of the gp120 monomer bound to CD4. The locations on the structure are shown for the variable regions and bridging sheet (colored ribbons and color key). This gp120 monomer structure is adapted from Kwong et. al17 and represents the truncated, deglycosylated conserved core of gp120 without the variable loops. The colored regions indicate the locations of the variable regions.

B. Ribbon diagram of the crystallographic structure of the V3 loop in situ on gp120 from the crystal structure solved by Huang et. al.80 indicating the base, stem and crown regions of the V3 loop.

C. Zones of sequence variability mapped onto the β-hairpin conformation of the V3 crown (adapted from 40). The crystallographic structure of the V3 crown is shown as a ribbon diagram, with commonly occurring side chains shown in stick depiction. A multi-colored illustrative cylinder is superimposed on the structure to highlight the four zones of the V3 crown41: the arch (green), the hydrophilic face (red) and hydrophobic face (blue) of the circlet, and the band (brown). Only the hydrophilic face has high sequence variability, but the amino acids that constitute it are distributed widely in the linear protein sequence, which obscures its existence unless the 3D structural context is appreciated. Side chains bound by neutralizing monoclonal antibodies are annotated with colored lines and a color key: monoclonal antibody 268 neutralizes only a few HIV strains and engages various side chains including one in the variable hydrophilic face of V3; monoclonal antibodies 3074 and 2219 neutralize viruses from several HIV-1 subtypes37 and avoid engagement of the hydrophilic variable zone.

BOX 1 Types of Antibody-binding Epitopes.

An antigenic determinant, also called an epitope, is a region of an immunogenic molecule that is recognized by the immune system, specifically by antibodies and T cell receptors.

Linear epitopes in proteins are composed of continuous stretches of amino acids derived from the protein sequence. Although antibodies that target “linear” epitopes can react with linear peptides, they might not necessarily react with contiguous stretches of amino acids within the peptides, but rather recognize discrete residues within the peptides that fold into particular conformations. This might result in greater affinity of the antibody for the native molecule compared with the relevant peptide100. Conformation contributes to most “linear” epitopes. Examples include the epitopes recognized by many gp120 V3-41, C5-101, and gp41-specific monoclonal antibodies102,103 (Table 1).

Discontinuous epitopes are composed of amino acids that are in close proximity in the folded protein, but that are distant when unfolded. By definition, these epitopes require some, or extensive, secondary and/or tertiary protein structure. Hence, they are often referred to as “conformational” epitopes. Examples include the human recombinant antibody IgG1b12, which reacts with residues in several regions of gp120 104, and human monoclonal antibody 17b, which reacts with the CD4-induced (CD4i) epitope16,21,105 (Table 1). These can also be referred to as compound epitopes.

Quaternary epitopes are created by protein–protein interactions that occur upon multimerization. It is as a result of such reorganization that many proteins (such as enzymes and the trimeric gp120 spike of HIV-1) carry out their physiological function. An antibody that reacts with a true quaternary epitope will not interact with the individual monomeric subunits. Examples include monoclonal antibodies 2909 and PG16, which react with the trimeric form of gp120 on the surface of virions or env-transfected cells but not with monomeric gp12051,53 (Table 1). However, some antibodies that react with quaternary epitopes react weakly with the monomeric subunits, but more strongly with the trimers. This seems to be true of monoclonal antibody PG9 53. Multimerization can result in changes in quaternary structure within individual subunits or through reorientation of the subunits relative to each other, so regions contributing to the epitope can be inter-molecular (trans) or intra-molecular (cis).

Table 1.

Characteristics of human envelope-specific neutralizing monoclonal antibodies

| Epitope | mAb | Epitope on |

Region(s) Recognized |

Epitope Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD4 binding site (CD4bs) | IgG1b12 HG16 VRC01 VRC03 |

gp120 | C2, C3, C4, V5, C5 | Discontinuous |

| CD4-induced (CD4i) | 17b X5 |

gp120 | Bridging sheet | Discontinuous |

| Complex Carbohydrate | 2G12 | gp120 | Carbohydrate moieties in C2, C3, V4 | Discontinuous |

| V3 | 447/52-D 2219 3074 HGN194 |

gp120 | V3 loop | Linear (conformational) |

| Quaternary neutralizing epitopes (QNEs) | 2909 PG9 PG16 |

gp120 trimer | V2/V3 | Quaternary |

| Membrane proximal external region (MPER) | 2F5 4E10 Z13 |

gp41 | Protein & lipid | Linear (conformational) |

In this article, we synthesize data from both the biological arena (viral and immunological studies) and the physical arena (structural and bioinformatics studies) to show how structure–function relationships of Env proteins can inform the design of an effective HIV vaccine. With special emphasis on the variable regions of gp120, we highlight the relationship between 3D molecular structure, biological function and immunological cross-reactivity. This approach demonstrates the potential utility of targeting sequence-variable regions and QNEs that are formed by the interaction of sequence-variable regions in the context of the Env trimers. Because of their sequence variability, these regions were previously dismissed as vaccine targets, but we now think that they should be reassessed as potentially valuable targets.

Biological functions of the various gp120 regions

Antibodies that interfere with key biological functions of the virus are able to “neutralize” virus infectivity. Therefore, understanding the function of various parts of Env assists in targeting antibodies that should be induced by protective vaccines.

Receptor-binding sites

It is now well-established that to trigger exposure of the HIV-1 gp41 fusion domain that initiates virus–cell fusion, gp120 must first bind to two cell-surface receptors: CD4 and CXC-chemokine receptor 4 (CXCR4) or CC-chemokine receptor 5 (CCR5)14,15. The receptor-binding surfaces on gp120 form distinct structural and antigenic regions that are highly conformational and are formed by discontinuous amino acids in several regions of gp12016,17(Box 1). The CD4 binding site (CD4bs) consists of many residues in the constant regions of gp120, but, until recently, only one of many CD4bs-specific monoclonal antibodies had been described with broad neutralizing activity18. Three more have recently been selected and characterized19,20(Table 1). This suggests that the critical region within the large CD4bs may be difficult to target with vaccine constructs, a fact that is supported by disappointing attempts to induce neutralizing CD4bs-specific antibodies with various vaccine constructs 6,7,9.

The chemokine receptor-binding region of gp120 consists of the invariant β2, β3, β20 and β21 strands (the bridging sheet), the V3 loop, and the stem of the V1/V2 double loop16,17. This highly conformational, discontinuous region of gp120 is often known as the CD4-induced (CD4i) region, because, as its name implies, it is formed after gp120 has bound CD4 with high affinity. Many human monoclonal antibodies specific for CD4i have been described21–24, indicating the strong immunogenicity of this region, but CD4i, when exposed on the virus particle, is sterically protected from most CD4i-specific antibodies during the process of infection owing presumably to its close proximity to the cell membrane25. Consequently, CD4i-specific antibodies may not protect against infection by most HIV-1 strains.

The V3 loop

The V3 loop of gp120 is a component of the chemokine receptor-binding region, and is a major determinant of co-receptor usage26–31. The length of the V3 loop is essentially constant at 34–35 amino acids. Although its amino acid sequence is highly variable, except in clade C viruses where its sequence is quite conserved32, sequence variation is restricted to only ~20% of the amino acid positions, and is located primarily in the two β-strands in the crown of the V3 loop (Figure 1B and 2D). The functional importance of V3 is illustrated by the fact that deletion of V3 completely abrogates virus infectivity33. Nonetheless, the value of V3-specific antibodies in blocking virus infection has been controversial because some V3 antibodies, especially those elicited early after infection, have limited breadth34, many neutralize only the most neutralization-sensitive “Tier 1” viruses19,35, no single V3-specific monoclonal antibody neutralizes more than ~10–25% of the more resistant “Tier 2” viruses19,36,37, and the accessibility of V3 is poor on many viruses38,39. However, given its essential function in HIV infectivity, its structural conservation40,41, its strong immunogenicity42, the existence of many V3-specific monoclonal antibodies with cross-clade neutralizing activity 19,36,37,43, and the demonstration that polyclonal V3-specific antibodies can be induced that neutralize viruses from diverse HIV-1 subtypes44, the V3 region remains a potentially important target for vaccine development.

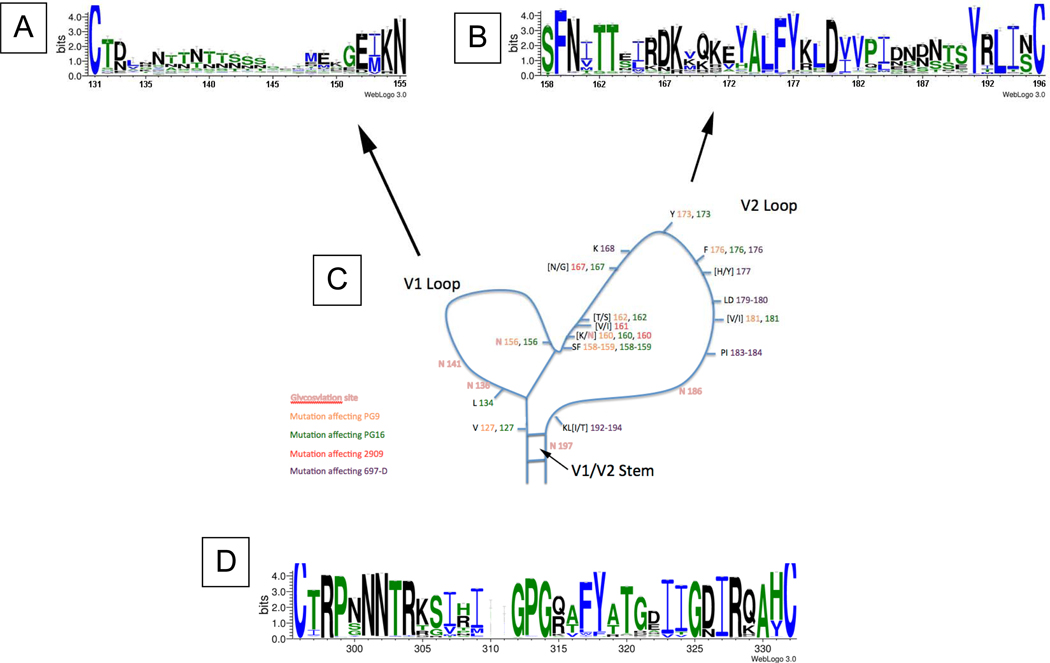

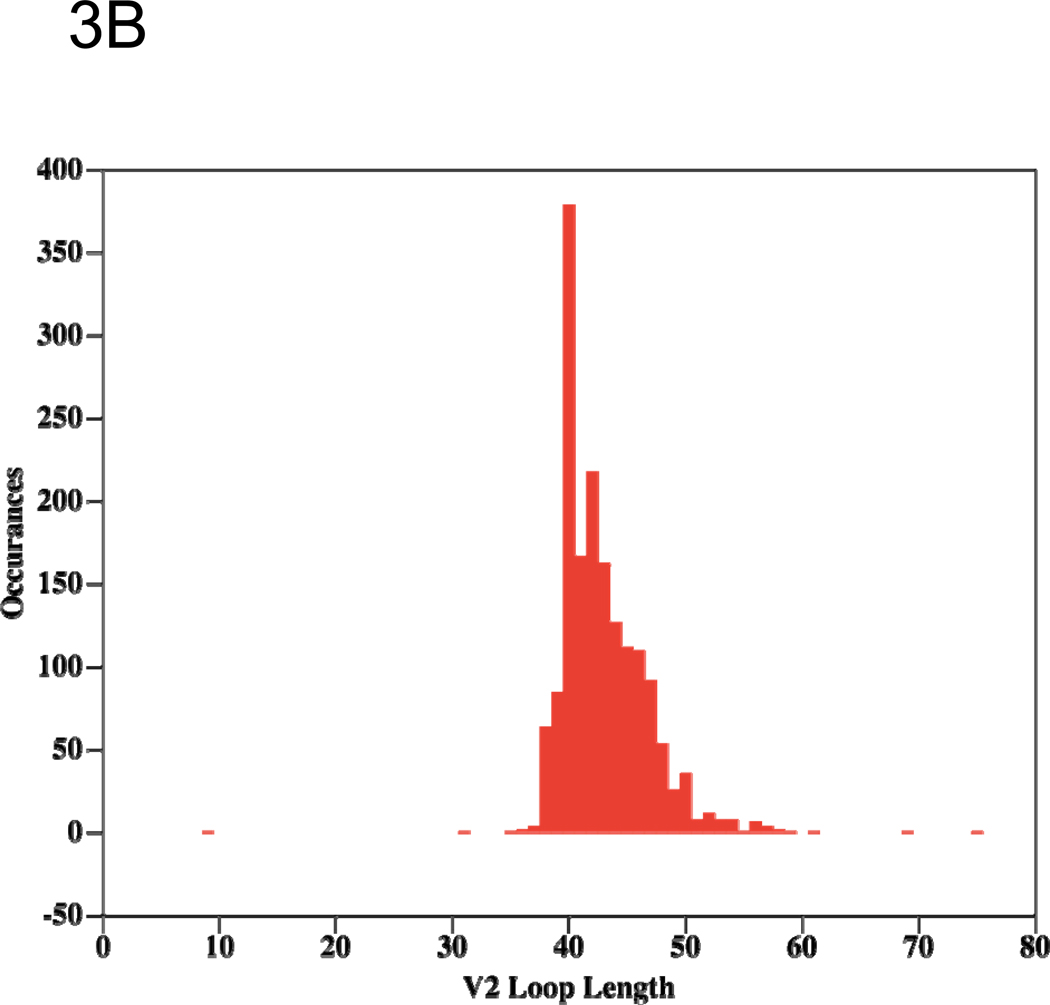

Figure 2.

Conserved and variable residues in the V1, V2, and V3 loops of gp120.

A. Sequence Logo depicting the amino acid conservation pattern across a multiple alignment of many V1 loops, each of which was selected because it has the most common V1 length depicted in Figure 3A. Data used to derive the Sequence Logo were derived from LANL, using one sequence per patient, and all HIV-1 subtypes were included. The height of the letter indicates the degree of conservation of the most common amino acid at that position. Amino acids are colored according to their chemical properties: polar amino acids (G,S,T,Y,C,Q,N) are green, basic amino acids (K,R,H) are blue, acidic amino acids (D,E) are red, and hydrophobic amino acids (A,V,L,I,P,W,F,M) are black. The few N- and C-terminal amino acids of the V1 loop show reasonable conservation, but most of the loop fades to small letters representative of no conservation except for a run of asparagines (N) and threonines (T) near the center suggesting a glycosylation region.

B. Sequence Logo depicting the amino acid conservation pattern across a multiple alignment of many V2 loops, each of which was selected from LANL (one sequence per patient, all subtypes included) because it has the most common V2 length depicted in Figure 3B. The height of the letter indicates the degree of conservation of that particular most common amino acid at that position. Although the V2 loop has many more insertions and deletions than the V3 loop, it has a degree of amino acid conservation approaching that of the V3 loop when one controls for loop length as explained above.

C. Amino acid positions and glycosylation sites that are implicated in the binding of V2-specific monoclonal antibody 697 and QNE-specific monoclonal antibodies PG9, PG16 and 2909 are mapped onto a schematic illustration of the V1/V2 loop structure. Map notations are colored according to the color key below the illustration. Brackets indicate more than one commonly occurring amino acid at a single position. The individual sites associated with each single Ab are distributed throughout the V1/V2 loop linearly, but must cluster in 3D space into one or a few overlapping epitopes. The amino acid numbering in this panel may not exactly match that in Figrues 2A and 2B due to the variation in V1 and V2 lengths.

D. Sequence Logo in the same fashion as Figures 2A and 2B depicting the amino acid conservation pattern across a multiple alignment of all V3 loops from LANL (one sequence per patient, all subtypes included)

The V2 loop

By contrast, V2 is not essential for infectivity33, which suggests that the evolutionary constraints to preserve an invariant V2 structure are less pronounced than for V3. However, V2 participates in several Env functions, providing the motif that binds to α4β7 integrin (the receptor apparently involved in the homing of the virus to gut mucosal cells)45, contributing to trimer formation 46, and participating as part of the chemokine receptor surface. V2 also plays a crucial role in masking neutralizing epitopes of gp120: changes in V2 length and glycosylation patterns allow viruses to escape from neutralization mediated by antibodies specific for V3 and the CD4bs of gp12047–50. Given these functions of the V2 loop, its newly recognized role as a component of QNEs51–54 and its partial structural conservation (see below), V2 becomes an additional target for vaccine development.

V1, V4 and V5

The functions of the other variable regions of gp120 are poorly defined. V1 may have functional significance as it can serve as a neutralizing epitope, and several potent neutralizing V1-specific monoclonal antibodies have been developed in transgenic mice55. The immunogenicity of V1 is affected by glycosylation56 and mutations in V1 can affect virus-induced syncytium formation57, but little more than this is known about its function. V4, by contrast, has no well-defined function, although it is a target for early autologous neutralizing antibodies58, and V4-specific neutralizing antibodies have been described in immunized rabbits59. V4 is involved in neutralization escape60, and undergoes extreme variation in early infection61. The V5 region, the only variable region that does not form a disulphide-linked loop, participates in forming the CD4bs surface, but no polyclonal or monoclonal neutralizing V5-specific antibodies have been described; nonetheless V5 is involved in neutralization escape, although V5 peptides were not able to block neutralizing antibody activity in sera62. Current data, therefore, do not support these variable regions as targets for HIV-1 antibody-based vaccines.

Trimeric Env spikes

Crystal structures of gp120 monomers have been available for over a decade 17, but the crystal structure of the trimeric Env spike is not available, though it has been modeled using monomer structures and cryo-electron tomography63–65. There are profound consequences to the oligomerization of the HIV-1 Env: trimer formation is a requirement for infectivity, results in the burial of neutralizing epitopes within oligomeric interfaces, and permits conformational epitope masking66–68. The QNEs that form upon trimerization of gp120 have been defined by various human and macaque monoclonal antibodies and are exceptionally potent51–54, a fact that reflects a critical function of the QNEs that have not yet been defined.

3D visualization of and antigenic conservation within the variable loops

Recently, several 3D structural studies have provided significant insights into the conserved structural elements in the variable loops of gp120, suggesting windows of opportunity for designing immunogens expressing these conserved structures.

The V3 loop

Although the V3 loop is the least variable of the HIV-1 Env variable regions because, in part, it is the only one that is essentially constant in length, its sequence varies considerably across strains, and this variability is most pronounced in its “crown”, ~14 amino acids in the middle of the V3 loop (Figure 1B). While the specificity of some V3 antibodies restricts their immunochemical and biologic function69,70, some V3-specific monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies from infected individuals are able to neutralize diverse HIV-1 strains19,36,43,71–74. Furthermore, some individual V3-specific monoclonal antibodies can neutralize ~25–50% of Tier 1 and Tier 2 HIV-1 strains in which the correct epitope is present19,37,43,72,75, polyclonal V3-specific responses to infection can neutralize Tier 1 and Tier 2 viruses from diverse clades 74, and vaccine-induced immune responses targeted to V3 can induce broader neutralizing activity than that seen in many human HIV+ sera or in mixtures of human monoclonal antibodies44.

Interestingly, crystallographic structures of the gp120 V3 loop crown from different virus strains in complex with various human monoclonal antibodies41,59,76–79, and structures of the V3 loop freely arranged in situ on the core of gp12080, all exhibit a V3 crown that forms variations of a common β-hairpin tertiary structure. Furthermore, the sequence variation of the V3 loop tends to cluster into a single continuous small zone when viewed in 3D space (Figure 1C and 40). We hypothesize that the crown of the V3 loop might be organized into a folded (albeit highly flexible) globular domain, with the majority of its surface being structurally, and therefore antigenically, invariant. This structural perspective explains both the cross-reactivity of many V3-specific antibodies, which bind the conserved surfaces of V3, and the narrow specificity of some V3-specific monoclonal antibodies, which bind the small sequence-variable zone (Figure 1C and 40,41). The discovery of conserved 3D structures in the sequence-variable V3 loop is consistent with the function of the V3 loop as a chemokine receptor-binding element: the receptor-binding surface of gp120 must be conserved to preserve virus infectivity, and these constraints apparently involve more of the V3 loop amino acid positions than they leave free to vary. This perspective of the V3 loop indicates which regions of V3 should be targeted with immunogens to elicit broadly neutralizing antibodies; it also reveals the region of V3 that induces only a strain-specific antibody response.

The V1/V2 double loop

V2 is variable in both sequence and length (Figures 2 and 3), and as a result is a profoundly more variable region than V3. V2 is immunogenic in ~20–45% of HIV-infected humans13 in contrast to V3, which induces antibodies in essentially all infected individuals42. Several human V2-specific monoclonal antibodies have been generated that cross-react with gp120 molecules from diverse HIV-1 isolates, and V2-specific monoclonal antibodies have also been produced from cells of infected chimpanzees and immunized rats81–83; this indicates that V2 might also contain some structurally conserved elements. Interestingly, many V2-specific monoclonal antibodies interact with the same amino acid residues or with overlapping regions of V2 (Figure 2C and 13,52,81,83,84). Published studies document the neutralizing activity of human and chimp V2-specific monoclonal antibodies. Although many of these antibodies have little or weak neutralizing activity, some are quite potent83,85,86.

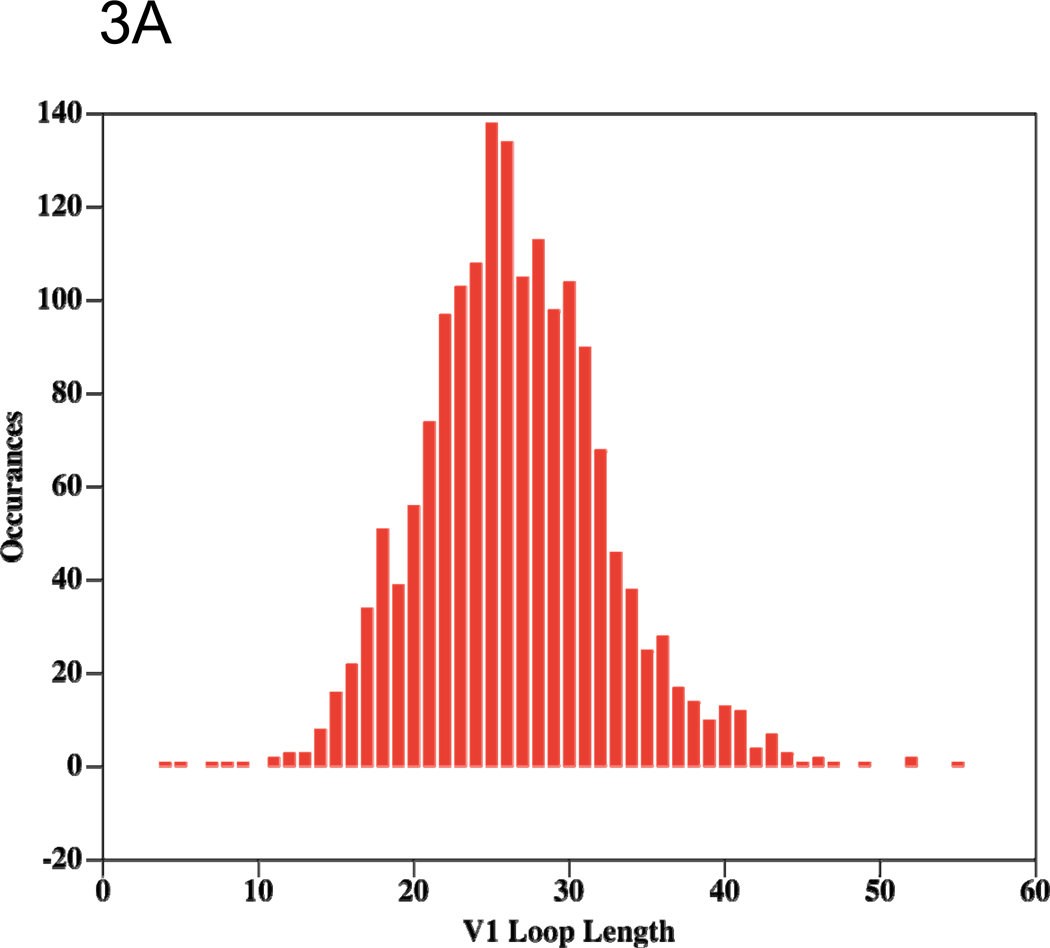

Figure 3.

Histograms showing the length distributions of the V1 (A) and V2 (B) loops from recorded HIV-1 sequences in LANL. The histograms shows the number (y-axis) of recorded viruses exhibiting each V1 or V2 length (number of amino acids, (x-axis) from zero to the maximal recorded length, so, for example, the origin shows that no viruses are recorded to have entirely deleted V1 or V2 loops (length of loop = 0).

Little is known about the 3D structure of the V2 loop, but the biologic advantage conferred by the integrin α4β7 binding motif in V2 45 may constrain at least part of the V2 structure. This receptor-binding motif occurs in a region of V2 containing alternating and periodic conserved charged and hydrophobic amino acid residues typical of a folded domain. In addition, V2 contains a well-conserved disulphide bond common in small, loosely folded domains with high sequence variation in their 3D structural folds (such as the thioredoxin fold found in many proteins with known 3D structure)87. It is also notable that the C-terminal portion of the stem of the V2 loop is located directly adjacent to the CD4bs in crystal structures of gp120 liganded to CD417,80, and that some data suggest that the presence or absence of V2 affects recognition and neutralization by the anti-CD4bs antibody IgG1b1266,88. Further structural information is derived from a comparison of the length distributions of V1 and V2 (Figures 3A and 3B). The normal distribution exhibited by V1 is typical of random sampling from multiple optional structures, and therefore suggests that V1 is likely to be a dynamic, unfolded and disordered flexible loop that flickers between many conformations. The only other structural clues available for V1 come from the presence in the mid-region sequence observed in the most common length of repetitive glycosylation motifs (NXT/S shown as V1 residues 6–14, see Figure 2A).

The differing length distributions in V1 and V2 reflect biological functions that suggest 3D structural order within V2, but, as noted, structural disorder within V1. Specifically, the V2 length distribution exhibits a sharp drop-off in length from the most frequent length to shorter lengths, but a more gradual drop-off as the length increases, suggesting a viral mechanism that affords very little tolerance of V2 lengths shorter than ~40 amino acids. This pattern of length variation is typical of either a folded globular domain, which requires a critical length below which the fold cannot assemble, or inter-monomer contacts, which require a critical length below which the loop cannot reach over from one monomer to another. In both cases, the observed length distribution requires some V2 structural order. The available structural data, together with the observed cross-reactive immunological patterns of V2 antibodies, suggest that a similar, but more challenging, approach to vaccine targeting, as envisioned for V3, might also be successful for V2, but that V1 is probably not a suitable vaccine target.

V2/V3 complexes in the envelope trimer

There is now evidence that V2 and V3 can, together, form complex epitopes comprised of contributions from both variable loops. These complex epitopes exist preferentially or exclusively in the trimeric form of the HIV Env spike, defining them as quaternary epitopes (Box 1). Antibodies specific for quaternary epitopes were first described in SHIV89.6P-infected macaques; although they were difficult to characterize in polyclonal sera, their activity seemed to map to a discontinuous epitope formed by V2 and V3 present on the virus’ Env spikes89. Similar antibodies were found in an HIV-infected chimpanzee90,91. Remarkably, these antibodies were extremely potent as neutralizing reagents. The first human QNE-specific monoclonal antibody to be described, 2909, is extremely potent (IC50 < 1.0 ng/ml) and targets both the V2 and V3 regions51. The epitope to which it binds is found only on the surface of virions and on env-transfected cells, and does not exist on the gp120 monomer or recombinant soluble Env trimers52,68, which indicates that this epitope is formed only when gp120 monomers form trimers in lipid membranes. Monoclonal antibody 2909 is highly strain-specific although it tolerates extensive amino acid sequence changes in V352. The strain-specificity is the result of a lysine, rather than the more common asparagine, at residue 160 in V2 (Figure 2C and position 3 in Figure 2B, and 52,54). So, although it is narrow in its reactivity, this monoclonal antibody defined the first quaternary epitope in the HIV-1 Env and revealed both tolerance for extensive variation in V3 and specificity constraints imposed by a single position in V2.

Recently, several QNE-specific monoclonal antibodies were generated from macaques infected with SHIVSF162P4 54. Similar to monoclonal antibody 2909, these antibodies have potent but strain-specific neutralizing activity, target V2 and V3, and are limited in breadth of reactivity by residues in V2. So, macaques and humans both make similar potent QNE-specific antibodies.

Notably, two clonally related human monoclonal antibodies (PG9 and PG16) have now been described that also target V2 and V3 and possess potent neutralizing activity (IC50 < 1.0 ng/ml for many strains)53. Both these monoclonal antibodies can be considered QNE-specific antibodies although PG9 reacts weakly with monomeric gp120 as well as with trimeric gp140 and seems to target mainly discontinuous residues in V2. Monoclonal antibody PG16, a true QNE antibody, recognizes only the trimeric form of gp120 and interacts with discontinuous residues found in V2 and the crown of V3. Unlike human monoclonal antibody 2909 and the macaque QNE-specific monoclonal antibodies, PG9 and PG16 have broad activity, neutralizing 73% and 79% of 162 diverse pseudoviruses, respectively. The crucial difference that distinguishes PG9 and PG16 from monoclonal antibody 2909, and accounts for their neutralization breadth, is their dependence on the asparagine-linked carbohydrate moiety present in most HIV-1 isolates at position 160 in V2 (Figure 2C and position 3 in Figure 2B). The neutralization breadth of PG9 and PG16 suggests that the epitopes they target are conserved and not masked in most strains of HIV-1.

The immunologic reactivity and neutralizing activity of the human QNE-specific monoclonal antibodies show that they can readily tolerate extensive amino acid changes in V352,53, and that broad or narrow activity is dependent on V2 variation. Furthermore, the broad neutralizing activity of PG9 and PG16 demonstrates that the quaternary epitopes recognized are composed of conserved elements in the V2 and V3 sequence-variable regions and are the among most accessible of all neutralizing epitopes present on the CD4-unliganded form of the trimeric Env spike. The modelled Env trimers63–65, provide clues for the visualizing the 3D structures of V2/V3 contacts, which probably occur within the many possible unliganded forms of the trimer. The resolved 3D structure(s) of trimers in QNE bound conformations should ultimately be highly informative for vaccine design.

In summary, recent data reveal conserved targets for broadly reactive antibodies in the sequence-variable V2 and V3 loops of gp120 and on quaternary structures formed by these loops in the trimeric Env. These data explain the broad immunological and functional cross-reactivity of some of the monoclonal antibodies specific for these regions and provide a framework for conceptualizing their value in vaccine design.

Epitope masking from a structural perspective

Although masking is often described in terms of the ability of glycans and other structural features to prevent or decrease the neutralizing activity of V3-specific antibodies19,34,38,47,92, epitope masking is a phenomenon common to all HIV-1 neutralizing epitopes, and is the result of a multitude of factors67. For example, the 3D structure of a particular epitope can assemble by adopting the “correct” conformation that clusters the key antibody-binding amino acid side-chains together into a single structure, but the protein may be designed to easily “flicker” out of that conformation, which would be observed as masking of the epitope from its cognate antibody. Similarly, other protein loops or glycans might “flicker” in to cover an epitope, which would also be observed immunologically as partial or complete masking. The result is that, although antibodies may be elicited by immunization targeting epitopes broadly present in circulating viruses, the effective neutralization of these antibodies in vivo is reduced to an uncertain extent by different types of masking. Masking can sometimes be overcome when particular conformations are stabilized by various molecular ligands. For example, in some strains, V3 epitope accessibility is markedly increased by the binding of CD4 and certain gp120-specific monoclonal antibodies that induce and stabilize conformational changes in gp12039,93,94. The latter data suggest that exposure of “masked” epitopes may be accomplished, and effective neutralizing activity achieved, by inducing “unmasking” antibodies along with antibodies to the “masked” epitope(s). Yet another perspective on masking is provided by some monoclonal antibodies that have differential neutralizing activities despite the fact that they target similar regions of the Env (Figure 2C). Binding of V2-, V3-, and QNE-specific antibodies to overlapping regions of V2 and V3 has different effects which may depend on the molecular dynamics of V2 and V3 loops in different conformations of the trimer and/or on the kinetics of V2 and V3 movement as they flicker between low and high-energy configurations95. Masking may, therefore, reflect the functional as well as the physical characteristics of an epitope in any of a myriad of molecular conformations. Hypothetically, residues in V2 and V3 may form the epitope(s) recognized by QNE-specific antibodies only when V2 and V3 interact in a configuration that leads to virus infectivity. In contrast, individual V2- and V3-specific antibodies may only recognize the epitopes on their respective loops when these loops occupy different space, i.e., are not in contact with one another, as in trimeric spikes that are not in an infectious conformation. The epitopes in the latter case would appear to be “masked”, since the anti-V2 and anti-V3 antibodies may not neutralize,

The conundrum of masking may, consequently, yield to further studies that can only be addressed by interdisciplinary studies that include structural as well as immunological and virological elements.

Conclusions and the way forward

Although the HIV-1 Env glycoproteins use variation, both in terms of sequence and conformation, to evade neutralization, there are nevertheless regions of structural conservation that can be targeted for vaccine design. This is supported by data showing that sequence-variable loops of HIV-1 gp120 can give rise to a spectrum of antibodies, some with very narrow specificities for only one or a few strains of HIV-1, and others with broad immunological and neutralizing activities against diverse HIV-1 strains. This is particularly true of antibodies specific for V2 and V3, and for the QNEs formed by these two regions of gp120. The immunological cross-reactivity of many of the monoclonal antibodies specific for these epitopes can now be explained by the structural conservation of 3D shapes within these sequence-variable loops and in the context of the functional requirements that limit the quality and quantity of sequence variability. This synthesis of the structural, functional, and antigenic conservation of sequence-variable regions of gp120 provides a paradigm for the rational design of recombinant immunogens: it illuminates how form must follow function, it recalls how form relates to antigenicity, and it suggests how immunogens can be rationally designed to focus the immune response towards the portions of structures that elicit broadly reactive antibodies and away from those regions that elicit antibodies with narrow reactivity. Such rationally-designed immunogens will be modelled on the detailed 3D structures of epitopes recognized by families of cross-clade and broadly neutralizing antibodies, targeting conserved structural features and eliminating or replacing those elements that narrow the antibody specificity. New techniques have led to an explosion in the number and specificities of monoclonal antibodies that can be derived from patient specimens19,20,51,53,73. Other newly discovered epitopes and as yet unidentified epitopes recognized by serum antibodies with HIV-1 neutralizing activity10,73,74,96–98 will provide additional targets beyond those that have been described here. Using structural and computational biology to rationally design recombinant epitope-scaffold immunogens based on neutralizing epitopes in the variable regions of Env has the potential of developing immunogens that elicit antibodies with greater specificity and potency than is currently achieved when various forms of gp120 and/or gp41 are used. Indeed, until recently, there has been limited success in inducing broadly reactive polyclonal neutralizing antibody responses that target selected epitopes in gp120 and gp41(6–9 and reviewed in 99). However, focusing the immune response on neutralizing epitopes through the use of epitope-scaffold vaccines designed to present conserved structural elements and to eliminate those that narrow antibody specificity is beginning to yield modest successes44. These techniques hold the promise of constructing immunogens that elicit polyclonal antibody responses specific for particular chosen epitopes with finer specificity and greater potency than is currently achieved.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to D. Almond and J. Swetnam for assistance in preparing the figures, and to C. Hioe, M. Totrov, and X.-P. Kong for contributing ideas to, and helping shape this article, which includes studies supported by grants from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the US National Institutes of Health (grants HL59725, AI36085, DP2 OD004631, and AI084119), and the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Biographies

Susan. Zolla-Pazner received her Ph. D. from the University of California, San Francisco Medical Center in Microbiology. Her doctoral research on the immunochemical analysis of antibody specificity has formed the foundation of her work, leading to studies of immunoregulation of B cells, molecular mimicry among proteins, analyses of protein structure-function relationships, and the prevention, treatment and diagnosis of human infectious diseases. She participated in the description of the immunodeficiency of the first AIDS patients in 1981. Her current work focuses on the development of an HIV vaccine that will induce protective antibodies. She is currently Professor of Pathology at New York University School of Medicine and Director of AIDS Research at the New York Veterans Affairs Medical Center.

Timothy Cardozo received his M.D. from New York University School of Medicine, and his Ph.D. in Biochemistry from New York University. After medical residency training and postdoctoral work at New York University and work as a computational structural biology consultant for Molsoft, LLC (La Jolla, CA), he became an Assistant Professor at New York University in 2005. His research includes structure-based HIV immunogen design, novel informatics approaches, novel drug discovery approaches, clinical translational research in skin diseases, and protein design.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gilbert PB, et al. Correlation between immunologic responses to a recombinant glycoprotein 120 vaccine and incidence of HIV-1 infection in a phase 3 HIV-1 preventive vaccine trial. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:666–677. doi: 10.1086/428405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buchbinder SP, et al. Efficacy assessment of a cell-mediated immunity HIV-1 vaccine (the Step Study): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, test-of-concept trial. Lancet. 2008;372:1881–1893. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61591-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rerks-Ngarm S, et al. Vaccination with ALVAC and AIDSVAX to Prevent HIV-1 Infection in Thailand. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2209–2220. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Primer V, editor. IAVI Report. 2010. Understanding Antibody FUnctions: Beyond Neutralization. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Starcich BR, et al. Identification and characterization of conserved and variable regions in the envelope gene of HTLV-III/LAV, the retrovirus of AIDS. Cell. 1986;45:637–648. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90778-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Selvarajah S, et al. Comparing antigenicity and immunogenicity of engineered gp120. J Virol. 2005;79:12148–12163. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.19.12148-12163.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Selvarajah S, et al. Focused dampening of antibody response to the immunodominant variable loops by engineered soluble gp140. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2008;24:301–314. doi: 10.1089/aid.2007.0158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Law M, Cardoso RM, Wilson IA, Burton DR. Antigenic and immunogenic study of membrane-proximal external region-grafted gp120 antigens by a DNA prime-protein boost immunization strategy. J Virol. 2007;81:4272–4285. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02536-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saphire EO, et al. Structure of a high-affinity "mimotope" peptide bound to HIV-1-neutralizing antibody b12 explains its inability to elicit gp120 cross-reactive antibodies. J Mol Biol. 2007;369:696–709. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.01.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li Y, et al. Analysis of neutralization specificities in polyclonal sera derived from human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected individuals. J Virol. 2009;83:1045–1059. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01992-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Simek MD, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 elite neutralizers: individuals with broad and potent neutralizing activity identified by using a high-throughput neutralization assay together with an analytical selection algorithm. J Virol. 2009;83:7337–7348. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00110-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kabat EA, Mayer MM. Experimental Immunochemistry. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas; 1961. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Israel ZR, Gorny MK, Palmer C, McKeating JA, Zolla-Pazner S. Prevalence of a V2 epitope in clade B primary isolates and its recognition by sera from HIV-1 infected individuals. Aids. 1997;11:128–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dalgleish AG, et al. The CD4 (T4) antigen is an essential component of the receptor for the AIDS retrovirus. Nature. 1984;312:763–767. doi: 10.1038/312763a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feng Y, Broder CC, Kennedy PE, Berger EA. HIV-1 entry cofactor: functional cDNA cloning of a seven-transmembrane, G protein-coupled receptor. Science. 1996;272:872–877. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5263.872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rizzuto CD, et al. A conserved HIV gp120 glycoprotein structure involved in chemokine receptor binding. Science. 1998;280:1949–1953. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5371.1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kwong PD, et al. Structure of an HIV gp120 envelope glycoprotein in complex with the CD4 receptor and a neutralizing human antibody. Nature. 1998;393:648–659. doi: 10.1038/31405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roben P, et al. Recognition properties of a panel of human recombinant Fab fragments to the CD4 binding site of gp120 that show differing abilities to neutralize Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1. J Virol. 1994;68:4821–4828. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.8.4821-4828.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Corti D, et al. Analysis of memory B cell responses and isolation of novel monoclonal antibodies with neutralizing breadth from HIV-1-infected individuals. PLoS One. 2010;5:e8805. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu X, et al. Rational Design of Envelopoe Surface Identifies Broadly Neutralizing Human Monoclonal Antibodies to HIV-1. Science. 2010 doi: 10.1126/science.1187659. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thali M, et al. Characterization of conserved HIV-type 1 gp120 neutralization epitopes exposed upon gp120-CD4 binding. J Virol. 1993;67:3978–3988. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.7.3978-3988.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang MY, Shu Y, Sidorov I, Dimitrov DS. Identification of a novel CD4i human monoclonal antibody Fab that neutralizes HIV-1 primary isolates from different clades. Antiviral Res. 2004;61:161–164. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2003.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moulard M, et al. Broadly cross-reactive HIV-1-neutralizing human monoclonal Fab selected for binding to gp120-CD4-CCR5 complexes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:6913–6918. doi: 10.1073/pnas.102562599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang MY, Dimitrov DS. Novel approaches for identification of broadly cross-reactive HIV-1 neutralizing human monoclonal antibodies and improvement of their potency. Curr Pharm Des. 2007;13:203–212. doi: 10.2174/138161207779313669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Labrijn AF, et al. Access of antibody molecules to the conserved coreceptor binding site on glycoprotein gp120 is sterically restricted on primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 2003;77:10557–10565. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.19.10557-10565.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shioda T, Levy JA, Cheng-Mayer C. Small amino acid changes in the V3 hypervariable region of gp120 can affect the T-cell-line and macrophage tropism of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:9434–9438. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.20.9434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Labrosse B, Treboute C, Brelot A, Alizon M. Cooperation of the V1/V2 and V3 domains of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 for interaction with the CXCR4 receptor. J Virol. 2001;75:5457–5464. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.12.5457-5464.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Trkola A, et al. CD4-dependent, antibody-sensitive interactions between HIV-1 and its co-receptor CCR-5. Nature. 1996;384:184–187. doi: 10.1038/384184a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hill CM, et al. Envelope glycoproteins from HIV-1, HIV-2 and SIV can use human CCR5 as a coreceptor for viral entry and make direct CD4-dependent interactions with this chemokine receptor. J Virol. 1997;71:6296–6304. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.9.6296-6304.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sharon M, et al. Alternative conformations of HIV-1 V3 loops mimic Β hairpins in chemokines, suggesting a mechanism for coreceptor selectivity. Structure (Camb) 2003;11:225–236. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(03)00011-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cardozo T, et al. Structural Basis of Co-Receptor Selectivity by the HIV-1 V3 Loop. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2007;23:415–426. doi: 10.1089/aid.2006.0130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gaschen B, et al. Diversity considerations in HIV-1 vaccine selection. Science. 2002;296:2354–2360. doi: 10.1126/science.1070441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cao J, et al. Replication and neutralization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 lacking the V1 and V2 variable loops of the gp120 envelope glycoprotein. J Virol. 1997;71:9808–9812. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.12.9808-9812.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Davis KL, et al. High titer HIV-1 V3-specific antibodies with broad reactivity but low neutralizing potency in acute infection and following vaccination. Virology. 2009;387:414–426. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li M, et al. Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 env Clones from Acute and Early Subtype B Infections for Standardized Assessments of Vaccine-Elicited Neutralizing Antibodies. J. Virol. 2005;79:10108–10125. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.16.10108-10125.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pantophlet R, Aguilar-Sino RO, Wrin T, Cavacini LA, Burton DR. Analysis of the neutralization breadth of the anti-V3 antibody F425-B4e8 and re-assessment of its epitope fine specificity by scanning mutagenesis. Virology. 2007;364:441–453. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hioe CE, et al. Anti-V3 monoclonal antibodies display broad neutralizing activities against multiple HIV-1 subtypes. PLoS ONE. 2010 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010254. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bou-Habib DC, et al. Cryptic nature of envelope V3 region epitopes protects primary monocytotropic human immunodeficiency virus type 1 from antibody neutralization. J Virol. 1994;68:6006–6013. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.9.6006-6013.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu X, et al. Soluble CD4 broadens neutralization of V3-directed monoclonal antibodies and guinea pig vaccine sera against HIV-1 subtype B and C reference viruses. Virology. 2008;380:285–295. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Almond D, et al. Structural Conservation Predominates over Sequence Variability in the Crown of HIV-1'S V3 Loop. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2010 doi: 10.1089/aid.2009.0254. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jiang X, et al. Conserved Structural Elements in the V3 Crown of HIV-1 GP120. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010 doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1861. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zolla-Pazner S. Improving on Nature: Focusing the Immune Response on the V3 Loop. Hum Antibodies. 2005;14:69–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gorny MK, et al. Cross-clade neutralizing activity of human anti-V3 monoclonal antibodies derived from the cells of individuals infected with non-B clades of HIV-1. J Virol. 2006;80:6865–6872. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02202-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zolla-Pazner S, et al. Cross-clade neutralizing antibodies against HIVI-1 induced in rabbits by focusing the immune response on a neutralizing epitope. Virology. 2009;392:82–93. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.05.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Arthos J, et al. HIV-1 envelope protein binds to and signals through integrin alpha4beta7, the gut mucosal homing receptor for peripheral T cells. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:301–309. doi: 10.1038/ni1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen B, et al. Structure of an unliganded simian immunodeficiency virus gp120 core. Nature. 2005;433:834–841. doi: 10.1038/nature03327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wei X, et al. Antibody neutralization and escape by HIV-1. Nature. 2003;422:307–312. doi: 10.1038/nature01470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sagar M, Wu X, Lee S, Overbaugh J. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 V1-V2 envelope loop sequences expand and add glycosylation sites over the course of infection, and these modifications affect antibody neutralization sensitivity. J Virol. 2006;80:9586–9598. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00141-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Derdeyn CA, et al. Envelope-constrained neutralization-sensitive HIV-1 after heterosexual transmission. Science. 2004;303:2019–2022. doi: 10.1126/science.1093137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ly A, Stamatatos L. V2 loop glycosylation of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 SF162 envelope facilitates interaction of this protein with CD4 and CCR5 receptors and protects the virus from neutralization by anti-V3 loop and anti-CD4 binding site antibodies. J Virol. 2000;74:6769–6776. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.15.6769-6776.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gorny MK, et al. Identification of a new quaternary neutralizing epitope on human immunodeficiency virus type 1 virus particles. J Virol. 2005;79:5232–5237. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.8.5232-5237.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Honnen WJ, et al. Type-Specific Epitopes Targeted by Monoclonal Antibodies with Exceptionally Potent Neutralizing Activities for Selected Strains of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Map to a Common Region of the V2 Domain of gp120 and Differ Only at Single Positions from the Clade B Consensus Sequence. J Virol. 2007;81:1424–1432. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02054-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Walker LM, et al. Broad and Potent Neutralizing Antibodies from an African Donor Reveal a New HIV-1 Vaccine Target. Science. 2009 doi: 10.1126/science.1178746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Robinson JE, et al. Quaternary epitope specificities of anti-HIV-1 neutralizing antibodies generated in rhesus macaques infected by the simian/human immunodeficiency virus SHIVSF162P4. J Virol. 2010;84:3443–3453. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02617-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.He Y, et al. Efficient isolation of novel human monoclonal antibodies with neutralizing activity against HIV-1 from transgenic mice expressing human Ig loci. J Immunol. 2002;169:595–605. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.1.595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Huang Z, et al. Levels of N-linked glycosylation on the V1 loop of HIV-1 Env proteins and their relationship to the antigenicity of Env from primary viral isolates. Curr HIV Res. 2008;6:296–305. doi: 10.2174/157016208785132518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sullivan N, Thali M, Furman C, Ho DD, Sodroski J. Effect of amino acid changes in the V1/V2 region of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 glycoprotein on subunit association, syncytium formation, and recognition by a neutralizing antibody. J Virol. 1993;67:3674–3679. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.6.3674-3679.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Moore PL, et al. The c3-v4 region is a major target of autologous neutralizing antibodies in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 subtype C infection. J Virol. 2008;82:1860–1869. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02187-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Burke B, et al. Neutralizing antibody responses to subtype B and C adjuvanted HIV envelope protein vaccination in rabbits. Virology. 2009;387:147–156. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dieltjens T, et al. HIV type 1 subtype A envelope genetic evolution in a slow progressing individual with consistent broadly neutralizing antibodies. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2009;25:1165–1169. doi: 10.1089/aid.2008.0161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Castro E, et al. Independent evolution of hypervariable regions of HIV-1 gp120: V4 as a swarm of N-Linked glycosylation variants. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2008;24:106–113. doi: 10.1089/aid.2007.0139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rong R, et al. Escape from autologous neutralizing antibodies in acute/early subtype C HIV-1 infection requires multiple pathways. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000594. e1000594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zanetti G, Briggs JA, Grunewald K, Sattentau QJ, Fuller SD. Cryo-Electron Tomographic Structure of an Immunodeficiency Virus Envelope Complex In Situ. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2:790–797. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhu P, et al. Distribution and three-dimensional structure of AIDS virus envelope spikes. Nature. 2006;441:847–852. doi: 10.1038/nature04817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Liu J, Bartesaghi A, Borgnia MJ, Sapiro G, Subramaniam S. Molecular architecture of native HIV-1 gp120 trimers. Nature. 2008;455:109–113. doi: 10.1038/nature07159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wyatt R, et al. The antigenic structure of the HIV gp120 envelope glycoprotein. Nature. 1998;393:705–711. doi: 10.1038/31514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kwong PD, et al. HIV-1 evades antibody-mediated neutralization through conformational masking of receptor-binding sites. Nature. 2002;420:678–682. doi: 10.1038/nature01188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kimura T, Wang XH, Williams C, Zolla-Pazner S, Gorny MK. Human monoclonal antibody 2909 binds to pseudovirions expressing trimers but not monomeric HIV-1 envelope proteins. Hum Antibodies. 2009;18:35–40. doi: 10.3233/HAB-2009-0200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gorny MK, Xu J-Y, Karwowska S, Buchbinder A, Zolla-Pazner S. Repertoire of neutralizing human monoclonal antibodies specific for the V3 domain of HIV-1 gp120. J Immunol. 1993;150:635–643. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Burke V, et al. Structural Basis of the Cross-Reactivity of Genetically Related Human Anti-HIV-1 Monoclonal Antibodies: Implications for Design of V3-based Immunogens. Structure. 2009;17:1538–1546. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2009.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Conley AJ, et al. Neutralization of primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolates by the broadly reactive anti-V3 monoclonal antibody, 447-52D. J Virol. 1994;68:6994–7000. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.11.6994-7000.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Binley JM, et al. Comprehensive cross-clade neutralization analysis of a panel of anti-human immunodeficiency virus type 1 monoclonal antibodies. J. Virol. 2004;78:13232–13252. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.23.13232-13252.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Scheid JF, et al. Broad diversity of neutralizing antibodies isolated from memory B cells in HIV-infected individuals. Nature. 2009;458:636–640. doi: 10.1038/nature07930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nandi A, et al. Epitopes for broad and potent neutralizing antibody responses during chronic infection with human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Virology. 2010;396:339–348. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.10.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pantophlet R, Wrin T, Cavacini LA, Robinson JE, Burton DR. Neutralizing activity of antibodies to the V3 loop region of HIV-1 gp120 relative to their epitope fine specificity. Virology. 2008;381:251–260. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.08.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Stanfield RL, Gorny MK, Williams C, Zolla-Pazner S, Wilson IA. Structural rationale for the broad neutralization of HIV-1 by human antibody 447-52D. Structure. 2004;12:193–204. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2004.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Stanfield RL, Gorny MK, Zolla-Pazner S, Wilson IA. Crystal structures of HIV-1 neutralizing antibody 2219 in complex with three different V3 peptides reveal a new binding mode for HIV-1 cross-reactivity. J Virol. 2006;80:6093–6105. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00205-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dhillon AK, et al. Structure determination of an anti-HIV-1 Fab 447-52D-peptide complex from an epitaxially twinned data set. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2008;64:792–802. doi: 10.1107/S0907444908013978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bell CH, et al. Structure of antibody F425-B4e8 in complex with a V3 peptide reveals a new binding mode for HIV-1 neutralization. J Mol Biology. 2008;375:969–978. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Huang CC, et al. Structure of a V3-containing HIV-1 gp120 core. Science. 2005;310:1025–1028. doi: 10.1126/science.1118398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wu Z, et al. Characterization of neutralization epitopes in the V2 region of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120: role of glycosylation in the correct folding of the V1/V2 domain. J Virol. 1995;69:2271–2278. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.4.2271-2278.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.McKeating JA, et al. Immunogenicity of full length and truncated forms of the human immunodeficiency virus type I envelope glycoprotein. Immunol Letters. 1996;51:101–105. doi: 10.1016/0165-2478(96)02562-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gorny MK, et al. Human anti-V2 monoclonal antibody that neutralizes primary but not laboratory isolates of HIV-1. J Virol. 1994;68:8312–8320. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.12.8312-8320.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Moore JP, et al. Probing the structure of the V2 domain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 surface glycoprotein gp120 with a panel of eight monoclonal antibodies: human immune response to the V1 and V2 domains. J Virol. 1993;67:6136–6151. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.10.6136-6151.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Warrier SV, et al. A novel, glycan-dependent epitope in the V2 domain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 is recognized by a highly potent, neutralizing chimpanzee monoclonal antibody. J Virol. 1994;68:4636–4642. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.7.4636-4642.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Pinter A, et al. The V1/V2 domain of gp120 is a global regulator of sensitivity of primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolates to neutralization by antibodies commonly induced upon infection. J Virol. 2004;78:5205–5215. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.10.5205-5215.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Atkinson HJ, Babbitt PC. An atlas of the thioredoxin fold class reveals the complexity of function-enabling adaptations. PLoS Comput Biol. 2009;5 doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000541. e1000541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Stamatatos L, Cheng-Mayer C. An envelope modification that renders a primary, neutralization-resistant clade B human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolate highly susceptible to neutralization by sera from other clades. J Virol. 1998;72:7840–7845. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.10.7840-7845.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Etemad-Moghadam B, et al. Characterization of simian-human immunodeficiency virus envelope glycoprotein epitopes recognized by neutralizing antibodies from infected monkeys. J Virol. 1998;72:8437–8445. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.10.8437-8445.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Chen CH, Jin L, Zhu C, Holz-Smith S, Matthews TJ. Induction and characterization of neutralizing antibodies against a human immunodeficiency virus type 1 primary isolate. J Virol. 2001;75:6700–6704. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.14.6700-6704.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Cho MW, Lee MK, Chen CH, Matthews T, Martin MA. Identification of gp120 regions targeted by a highly potent neutralizing antiserum elicited in a chimpanzee inoculated with a primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolate. J Virol. 2000;74:9749–9754. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.20.9749-9754.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Krachmarov C, et al. Factors determining the breadth and potency of neutralization by V3-specific human monoclonal antibodies derived from subjects infected with clade A or clade B strains of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 2006;80:7127–7135. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02619-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Mbah HA, et al. Effect of soluble CD4 on exposure of epitopes on primary, intact, native human immunodeficiency virus type 1 virions of different genetic clades. J Virol. 2001;75:7785–7788. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.16.7785-7788.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hioe CE, et al. The use of immune complex vaccines to enhance antibody responses against neutralizing epitopes on HIV-1 envelope gp120. Vaccine. 2009;28:352–360. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.10.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Hsu ST, Bonvin AM. Atomic insight into the CD4 binding-induced conformational changes in HIV-1 gp120. Proteins. 2004;55:582–593. doi: 10.1002/prot.20061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Guan Y, et al. Discordant memory B cell and circulating anti-Env antibody responses in HIV-1 infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:3952–3957. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813392106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Binley JM, et al. Profiling the specificity of neutralizing antibodies in a large panel of plasmas from patients chronically infected with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 subtypes B and C. J Virol. 2008;82:11651–11668. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01762-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Sather DN, et al. Factors associated with the development of cross-reactive neutralizing antibodies during human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J Virol. 2009;83:757–769. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02036-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Arnold GF, et al. Broad neutralization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) elicited from human rhinoviruses that display the HIV-1 gp41 ELDKWA epitope. J Virol. 2009;83:5087–5100. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00184-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Gorny MK, et al. Neutralization of diverse HIV-1 variants by an anti-V3 human monoclonal antibody. J Virol. 1992;66:7538–7542. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.12.7538-7542.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Hochleitner EO, Gorny MK, Zolla-Pazner S, Tomer KB. Mass spectrometric characterization of a discontinuous epitope of the HIV envelope protein HIV-gp120 recognized by the human monoclonal antibody 1331A. J Immunol. 2000;164:4156–4161. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.8.4156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Robinson WE, Jr, Gorny MK, Xu JY, Mitchell WM, Zolla-Pazner S. Two immunodominant domains of gp41 bind antibodies which enhance HIV-1 infection in vitro. J Virol. 1991;65:4169–4176. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.8.4169-4176.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Gorny MK, Zolla-Pazner S. Recognition of free and complexed peptides representing the prefusogenic and fusogenic forms of HIV-1 gp41 by human monoclonal antibodies. J Virol. 2000;74:6186–6192. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.13.6186-6192.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Zhou T, et al. Structural definition of a conserved neutralization epitope on HIV-1 gp120. Nature. 2007;445:732–737. doi: 10.1038/nature05580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Moore JP, Sodroski J. Antibody cross-competition analysis of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 exterior envelope glycoprotein. J Virol. 1996;70:1863–1872. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.3.1863-1872.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]