Abstract

The only established genetic determinant of non-Mendelian forms of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the ε4 allele of the apolipoprotein E gene (APOE). Recently, it has been reported that the P86L polymorphism of the calcium homeostasis modulator 1 gene (CALHM1) is associated with the risk of developing AD. In order to independently assess this association, we performed a meta-analysis of 7,873 AD cases and 13,274 controls of Caucasian origin (from a total of 24 centres in Belgium, Finland, France, Italy, Spain, Sweden, the UK and the USA). Our results indicate that the CALHM1 P86L polymorphism is likely not a genetic determinant of AD but may modulate age at onset by interacting with the effect of the ε4 allele of the APOE gene.

INTRODUCTION

Although Alzheimer's disease (AD) is the most common cause of dementia in the elderly, its aetiology is still not fully understood. The characterisation of causative factors is thus important for better defining the pathophysiological processes involved. Hereditary, early-onset forms of AD have been linked to disease-causing mutations in three different genes: the amyloidprecursor protein (APP) gene on chromosome 21, the presenilin1 (PSEN1) gene on chromosome 14 and the presenilin 2 (PSEN2)gene on chromosome 1 (1). However, the known mutations in these three genes account for less than 1% of all AD cases (2). Most forms of AD develop after the age of 65 and are considered to be sporadic because they lack an obvious familial aggregation. The term “sporadic” has, however, been gradually replaced by the concept of non-Mendelian (i.e. genetically complex) transmission. Although the importance of the genetic component of these non-Mendelian forms has long been debated, there is now a large body of evidence suggesting that genetic variation plays the major role in determining risk for this form of AD as well. This evidence is largely based on twin studies which have shown that the heritability of AD in general is high (between 60 and 80%) (3). This latter study has also shown that age at onset (AAO) is significantly more consistent for pairs of monozygotic twins than for dizygotic twins indicating that genetic variants also explain a substantial proportion of AAO variation across AD cases (3). While these observations highlight the importance of genetic factors in the risk for developing AD, at present, only the ε4 allele of the apolipoprotein E (APOE) gene has been unequivocally identified as a major determinant for the non-Mendelian forms of AD (4–6). In addition, currently more than two dozen loci show significant risk effects in meta-analyses synthesizing the available data from all published studies in the field. (http://www.alzgene.org) (7).

We recently reported that the gene coding for the newly characterised calcium homeostasis modulator 1 (CALHM1) channel may be a potential genetic risk factor for non-Mendelian forms of AD. The less common allele (L) of a non-synonymous polymorphism (P86L or rs2986017) within this gene was found to be associated with an increased risk for developing AD. Further it was shown that the underlying amino-acid substitution from proline to leucine leads to a loss of Ca2+ permeability, modulation of APP metabolism and, ultimately, to an increase in Aβ peptide secretion (8). However, although CALHM1's biological properties make it a plausible AD risk factor (8,9), most of the currently published follow-up studies in Caucasian populations were unable to confirm the association between the P86L polymorphism and the risk of developing AD (10–14) at the exception of one report (15). Despite this contradictory data using affection status as phenotype, three studies, in addition to the original report, showed association between an earlier AAO and homozygosity of the L allele and a marker in the CALHM1 vicinity (11,15,16).

In this study, we assessed the question whether or not CALHM1 is a genetic susceptibility factor for non-Mendelian AD, we genotyped a total of 9,662 individuals (2,249 cases and 7,413 controls) not previously tested for CALHM1 and performed a meta-analysis synthesizing these data with previously published genotypes in a total sample of 7,873AD cases and 13,274 controls of Caucasian origin.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Case-control samples were obtained from centres in Belgium (1 study) (12,17), Finland (1 study) (10) France (3 studies) (8,18), Italy (10 studies) (14,17), Spain (4 studies) (15,17), Sweden (1 studies) (10), the UK (1 study) (9) and the USA (3 studies) (8,11,13). The main characteristics of the different populations in each country are described in Supplementary Table 3. Clinical diagnoses of probable AD were all established according to the DSM-III-R and NINCDS-ADRDA criteria (19). Controls were defined as subjects not meeting the DMS-III-R dementia criteria and with intact cognitive functions (mini mental status examination score>25). Written informed consent to participation was provided by all subjects or, in cases of substantial cognitive impairment, a caregiver, legal guardian or other proxy. The study protocols for all populations were reviewed and approved by the appropriate institutional review boards in each country. Depending on the centre, a broad range panel of technologies were used to genotype the rs2986017 SNP (8,10–15).

Univariate analysis was performed using Pearson’s χ2 test. Review Manager software release 5.0 (http://www.cc-ims.net/RevMan/) was used to estimate the overall effect (random effect odds ratio). For multivariate analysis, SAS software release 9.1 was used (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and inter-population homogeneity between was tested using Breslow-Day computation (20). The association of the P86L polymorphism with the risk of developing AD was assessed by a multiple logistic regression model adjusted for age, gender, APOE status and centre or country (see Supplementary Table 3 for description of AAO per country). The association between the P86L polymorphism and AAO was assessed using a mixed model adjusted for gender and using the centre as a random variable. Similar results were obtained when using the country as a random variable (data not shown). The presence or absence of an interaction between APOE status and the P86L polymorphism was systematically assessed in all logistic regression or mixed models.

RESULTS

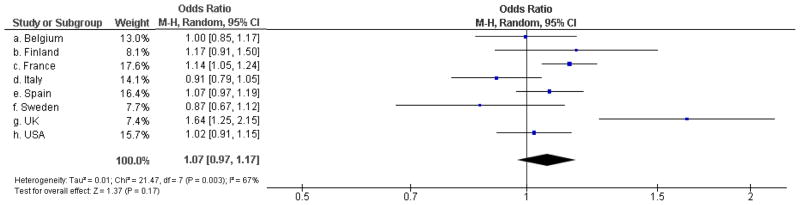

Upon combining all available case-control genotype data for the P86L SNP in allele-based effects meta-analyses, we observed that the population-specific ORs showed significant evidence for heterogeneity across datasets (p=0.003). We thus calculated the summary OR using a random-effects model, where the overall P86L association appeared to be not significant (OR=1.07; 95% confidence interval (CI) [0.97–1.17]; p=0.17; Figure 1). Upon exclusion of the five initial case-control datasets (all part of the initial, positive study)8, the heterogeneity across population-specific ORs was substantially reduced (p=0.29), but neither meta-analysis showed significant results (OR=1.01; 95% CI [0.95–1.08]; p=0.76).

Figure 1.

Association between the P86L L allele and the risk of developing AD in the different case-control studies, according to the country of origin.

As we had access to subject-level genotype and phenotype data for all samples, we also tested for association between P86L and AD risk by pooling data across studies and adjusting for age, gender, APOE ε4 status, and centre using an additive logistic regression model. This model is equivalent to the allelic association approach when the conditions for Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium are met (21), which was true for the combined sample (Supplementary Table 1). In this model, the L allele of the P86L polymorphism was weakly associated with AD (OR=1.09; 95% CI [1.03–1.15]; p=0.002). However, this association was mainly driven by the initial case-control datasets of the original report, and was no longer significant after exclusion of these samples (OR=1.02; 95% CI [0.95–1.08], adjusted for age, gender, APOE status and centre; p=0.66).

Finally, we assessed the association of the P86L polymorphism with AAO using a mixed model with centre of origin as a random variable. As previously reported (8,11,15), patients bearing the LL genotype displayed an earlier AAO than carriers of the LP and PP genotype (71.8 ± 8.9 vs. 73.0 ± 8.9 years of age, respectively; p=8×10−4; Table 1 and supplementary Table 2). This association was still observed after exclusion of the initial samples (73.2 ± 8.2 vs. 74.3 ± 8.2 years of age, respectively; p=0.001). Following the detection of an interaction between the P86L, APOE ε2/ε3/ε4 polymorphisms and AAO (p=0.04), we stratified the data according to APOE status and observed that the association of the LL genotype with AAO was the strongest in ε4 carriers (70.2 ± 8.5 vs. 72.0 ± 8.2 years; p = 4×10−5 (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 2). Again, this association was still observed after exclusion of the initial samples (71.9 ± 7.4 vs. 73.2 ± 7.5 years of age, respectively; p=0.002).

Table 1.

Association between the CALHM1 P86L polymorphism and age at onset (in years ± SD) for all AD cases and for ε4 or non-ε4 AD cases.

| Whole | e4 bearers | non e4 bearers | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | age at onset | n | age at onset | n | age at onset | |

| GG | 3658 | 73.0 ± 8.9 | 1969 | 72.0 ± 7.9 | 1673 | 74.2 ± 9.8 |

| AG | 2761 | 73.1 ± 8.9 | 1473 | 71.9 ± 8.3 | 1277 | 74.4 ± 9.5 |

| AA | 588 | 71.8 ± 8,9 | 316 | 70.2 ± 8.2 | 271 | 73.6 ± 9.3 |

| p1 | 0.004 | 2×10−4 | 0.78 | |||

| Δ (AA versus AG+GG)2 | −1.2 | −1.8 | −0.7 | |||

| p3 | 8×10−4 | 4×10−5 | 0.54 | |||

mixed model adjusted for gender and using centre as a random variable

Δ, the difference in AAO between LL and PL + PP carriers (in years).

the difference in AAO between LL and PL + PP carriers, using a mixed model adjusted for gender and with centre as a random variable.

When taking into account the well characterised APOEε4 allele dose effect on AAO, we observed that the P86L LL genotype was systematically associated with a decrease in AAO in ε3/ε4 and ε4/ε4 carriers (Table 2). Comparison of likelihood ratio between a mixed model including only APOE genotype and a mixed model including both APOE and CALHM1 genotypes indicated that addition of the CALHM1 P86L polymorphism was more informative to explain the AAO variability than the APOE ε4 allele alone (p=1×10−10).

Table 2.

Association between the APOEε4 allele alone and in combination with the P86L polymorphism with age at onset (in years ± SD).

| APOE | n | age at onset1 | APOE | rs2986017 | n | age at onset2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ε4−/ε4− | 3223 | 74.2 ± 9.6 | ε4−/ε4− | AG+GG | 2952 | 74.3 ± 9.7 |

| AA | 271 | 73.6 ± 9.3 | ||||

| ε4−/ε4+ | 3027 | 72.5 ± 8.1 | ε4−/ε4+ | AG+GG | 2774 | 72.6 ± 8.1 |

| AA | 253 | 70.9 ± 8.3 | ||||

| ε4+/ε4+ | 736 | 68.4 ± 7.5 | ε4+/ε4+ | AG+GG | 671 | 69.0 ± 7.5 |

| AA | 65 | 67.2 ± 7.0 |

p=1.1×10−31 (mixed model adjusted for gender and using centre as a random variable)

p=2.6×10−31 (mixed model adjusted for gender and using centre as a random variable)

DISCUSSION

Using both novel and previously published genotype data, we performed meta-analyses of 7,873 AD cases and 13,274 controls from 24 centres assessing the potential association between the P86L polymorphism in CALHM1 and risk for AD, but were unable to replicate the initial findings. The discrepancy of risk effects between the independent follow-up data and the data first published by Dreses-Werringloer et al. (8), may indicates a false-positive finding in the initial report, a situation commonly observed in genetically complex diseases and referred to as “proteus phenomenon” or to as the “winner's curse phenomenon” (22). In addition to chance variation and technical artifacts, this may be caused by population substructure across cases and controls included in the affected association studies. Indeed, this type of difference can lead to spurious associations between diseases and genetic markers (23–26), particularly when low increases in risk are involved (27). This observation may be particularly relevant for the P86L L allele, since its frequency appears to be highly variable (even ranging from 20 to 31% for Caucasian populations) and its association with AD risk was categorized as moderate in the initial report (8).

However, even though our meta-analysis results rather unequivocally refute the initial findings suggesting that CALHM1 is a genetic risk factor for AD, the present work suggests that the CALHM1 P86L polymorphism could modulate AAO and more specifically the APOE ε4 allele's dose effect on this phenotype. Interestingly, several studies have shown that AAO in AD is highly heritable (28,29), and (in addition to the strong association of the ε4 allele with AAO) it has been suggested that genes such as GTS1 or GTS2 may have a specific effects on AAO without necessarily modifying the risk for developing AD (30–32), although these findings have not been independently replicated to date. In this context, it is worth noting that AAO data are difficult to acquire reliably reducing the power of such analyses. Although the large overall sample size analyzed in the present study should help to decrease the likelihood of a false-negative outcome, additional genetic studies will be required to further characterize the association between the P86L polymorphism and AAO in ε4-carriers. However, it appeared that the association of the P86L polymorphism with AAO was still observed after exclusion of the initial samples, this supporting a real impact of CALHM1 on disease progression. It is also worth noting that factors affecting AAO tends to be spuriously associated with disease susceptibility (and the younger the cases the stronger this artefactual association may be) and this confounding effect may explain in part positive results in cross-sectional studies (33).

Furthermore, it would be of particular interest to extend the association analyses to non-Caucasian populations, such as those of South-East Asian (for which conflicting results have already been reported (34–36), or African descent. However, since the P86L L allele frequency is lower in Asian populations than Caucasian populations, particularly large sample sizes will be needed to detect significant risk or AAO effects.

Given that the P86L L allele has been associated with an increase in Aβ production in vitro (8), confirmation of this association with AAO may indicate that a variation in Aβ production can modulate AD progression without increasing the AD risk. Interestingly, biological evidence suggests that both the APOE gene and the genetic determinants characterised in two recent genome-wide association studies (GWASs) in AD may be primarily involved in Aβ peptide clearance (17,37). Combination of these genetic results and physiopathological data may thus indicate that whereas familial, early-onset forms of AD are mainly linked to genes that are involved in Aβ overproduction, genetic variants of APOE and the GWAS-defined loci may influence susceptibility to late-onset forms of the disease via a role in Aβ clearance (38). In this context, we could hypothesize that the moderate over-production of Aβ peptides associated with the P86L L allele only modifies the AD process when there is a failure in Aβ clearance - a failure that is likely to be particularly exacerbated in ε4 carriers.

In conclusion, the present meta-analysis does not support the notion that CALHM1 is a genetic risk factor for AD. However, we found a significant association between the P86L L-allele and earlier onset for AD, particularly in carriers of the APOE ε4-allele. Therefore, further studies are warranted aimed at investigating whether or not genetic variation at CALHM1 may modify some of the pathophysiological processes involving Ca2+ homeostasis and leading to AD (39–41), in particular in carriers of the APOE ε4 allele.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The work was made possible by the generous participation of the control subjects, the patients, and their families. We thank Dr. Anne Boland (CNG) for her technical help in preparing the DNA samples for analyses. This work was supported by the National Foundation for Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders, the Institut Pasteur de Lille and the Centre National de Génotypage. The Three-City Study was performed as part of a collaboration between the Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale (Inserm), the Victor Segalen Bordeaux II University and Sanofi-Synthélabo. The Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale funded the preparation and initiation of the study. The 3C Study was also funded by the Caisse Nationale d’assurance des Maladie des Travailleurs Salariés, Direction Générale de la Santé, MGEN, Institut de la Longévité,Agence Française de Sécurité Sanitaire des Produits de Santé, the Aquitaine and Bourgogne Regional Councils, Fondation de France and the joint French Ministry of Research/INSERM“Cohortes et collections de données biologiques” programme. Lille Génopôle received an unconditional grant from Eisai.

Belgium sample collection : the Antwerp site (CVB) was in part supported by the VIB Genetic Service Facility (http://www.vibgeneticservicefacility.be/) and the Biobank of the Institute Born-Bunge; the Special Research Fund of the University of Antwerp; the Fund for Scientific Research-Flanders (FWO-V); the Foundation for Alzheimer Research (SAOFRMA), the Interuniversity Attraction Poles (IAP) program P6/43 of the Belgian Federal Science Policy Office; Belgium; K.S. is a postdoctoral fellow and K.B. a PhD fellow of the FWO-V.

Finish sample collection : Financial support for this project was provided by the Health Research Council of the Academy of Finland, EVO grant 5772708 of Kuopio University Hospital, and the Nordic Centre of Excellence in Neurodegeneration. Italian sample collections : the Bologna site (FL) obtained funds from the Italian Ministry of research and University as well as Carimonte Foundation. The Florence site was supported by a grant from the Italian ministry of Health (RFPS-2006-7-334858). The Milan site was supported by grants from the “Fondazione Monzino” and the Italian Ministry of Health. We thank the expert contribution of Mr. Carmelo Romano. This work was performed in the frame of AMBISEN Center, High Technology Center for the study of the Environmental Damage of Endocrine and Nervous System, University of Pisa. We thank Dr. A. LoGerfo for the preparation of the DNA collection. The Cagliari site was partly supported by a grant from the Italian Ministry of Health (Progetti di Ricerca Finalizzati).

Spanish sample collection : the Madrid site (MB) was supported by grants of the Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia and the Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo (Instituto de Salud CarlosIII), and an institutional grant of the Fundación Ramón Areces to the CBMSO. We thank I.Sastre and Dr. A Martínez-García for the preparation and control of the DNA collection, and Drs. P. Gil and P. Coria for their cooperation in the cases/controls recruitment. We are grateful to the Asociación de Familiares de Alzheimer de Madrid (AFAL) for continuous encouragement and help. The Neocodex centre thanks the staff of the Memory Clinic of Fundació ACE. Institut Català de Neurociències Aplicades (Barcelona,Spain), Ana Mauleón, Maitée Rosende-Roca, Pablo Martínez-Lage, Montserrat Alegret, Susana Ruíz and Lluís Tárraga. We are indebted to the Unidad de Demencias, Hospital Universitario Virgen de la Arrixaca (Murcia, Spain), Juan Marin, and to the Memory Unit of the Hospital Universitario La Paz-Cantoblanco (Madrid, Spain). This study has been partially funded by Fundación Alzheimur (Murcia) and the Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia (Gobierno de España)(PCT-010000-2007-18).

US sample collections. The study was partly supported by USA National Institute on Aging (NIA) grant AG030653, AG20135, AG19757), by National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NS31153), the Alzheimer’s Association, and the Louis D. Scientific Award of the Institut de France.

References

- 1.Hardy J. Amyloid, the presenilins and Alzheimer's disease. Trends Neurosci. 1997;20:154–159. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(96)01030-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Campion D, Dumanchin C, Hannequin D, Dubois B, Belliard S, Puel M, et al. Early-onset autosomal dominant Alzheimer disease: prevalence, genetic heterogeneity, and mutation spectrum. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;65:664–670. doi: 10.1086/302553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gatz M, Reynolds CA, Fratiglioni L, Johansson B, Mortimer JA, Berg S, et al. Role of genes and environments for explaining Alzheimer disease. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:168–174. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.2.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Farrer LA, Cupples LA, Haines JL, Hyman B, Kukull WA, Mayeux R, et al. Effects of age, sex, and ethnicity on the association between apolipoprotein E genotype and Alzheimer disease. A meta-analysis. APOE and Alzheimer Disease Meta Analysis Consortium. JAMA. 1997;278:1349–1356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bertram L, Tanzi RE. Thirty years of Alzheimer's disease genetics: the implications of systematic meta-analyses. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:768–778. doi: 10.1038/nrn2494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lambert J-C, Amouyel P. Genetic heterogeneity of Alzheimer's disease: complexity and advances. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2007;32:S62–70. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2007.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bertram L, McQueen MB, Mullin K, Blacker D, Tanzi RE. Systematic meta-analyses of Alzheimer disease genetic association studies: the AlzGene database. Nat Genet. 2007;39:17–23. doi: 10.1038/ng1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dreses-Werringloer U, Lambert J-C, Vingtdeux V, Zhao H, Vais H, Siebert A, et al. A polymorphism in CALHM1 influences Ca2+ homeostasis, Abeta levels, and Alzheimer's disease risk. Cell. 2008;133:1149–1161. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.05.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moreno-Ortega AJ, Ruiz-Nuño A, García AG, Cano-Abad MF. Mitochondria sense with different kinetics the calcium entering into HeLa cells through calcium channels CALHM1 and mutated P86L-CALHM1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;391:722–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.11.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bertram L, Schjeide BM, Hooli B, Mullin K, Hiltunen M, Soininen H, et al. No association between CALHM1 and Alzheimer's disease risk. Cell. 2008;135:993–994. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.11.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Minster RL, Demirci FY, DeKosky ST, Kamboh MI. No association between CALHM1 variation and risk of Alzheimer disease. Hum Mutat. 2009;30:E566–569. doi: 10.1002/humu.20989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sleegers K, Brouwers N, Bettens K, Engelborghs S, van Miegroet H, De Deyn PP, et al. No association between CALHM1 and risk for Alzheimer dementia in a Belgian population. Hum Mutat. 2009;30:E570–574. doi: 10.1002/humu.20990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beecham GW, Schnetz-Boutaud N, Haines JL, Pericak-Vance MA. CALHM1 polymorphism is not associated with late-onset Alzheimer disease. Ann Hum Genet. 2009;73:379–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.2009.00509.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nacmias B, Tedde A, Bagnoli S, Cellini E, Piaceri I, Guarnieri BM, et al. Lack of implication for CALHM1 P86L common variation in Italian patients with early and late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. J alzheimers Dis. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-1345. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boada M, Antunez C, Lopez-Arrieta J, Galan JJ, Moron FJ, Hernandez I, et al. CALHM1 P86L polymorphism is associated with late-onset Alzheimer’s disease in a recessive model. J alzheimers Dis. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-1357. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li H, Wetten S, Li L, St Jean PL, Upmanyu R, Surh L, et al. Candidate single-nucleotide polymorphisms from a genomewide association study of Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2008;65:45–53. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2007.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lambert J-C, Heath S, Even G, Campion D, Sleegers K, Hiltunnen M, et al. Genome wide association indentifies variants at CLU and CR1 associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Genet. 2009;41 :1094–1099. doi: 10.1038/ng.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chapuis J, Hot D, Hansmannel F, Kerdraon O, Ferreira S, Hubans C, et al. Transcriptomic and genetic studies identify IL-33 as a candidate gene for Alzheimer's disease. Mol Psychiatry. 2009;14:1004–16. doi: 10.1038/mp.2009.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1984;34:939–944. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Breslow NE, Day NE, Halvorsen KT, Prentice RL, Sabai C. Estimation of multiple relative risk functions in matched case-control studies. Am J Epidemiol. 1978;108:299–307. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schaid DJ, Jacobsen SJ. Biased tests of association: comparisons of allele frequencies when departing from Hardy-Weinberg proportions. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;149:706–711. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kraft P. Curses--winner's and otherwise--in genetic epidemiology. Epidemiology. 2008;19:649–51. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e318181b865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Freedman ML, Reich D, Penney KL, McDonald GJ, Mignault AA, Patterson N, et al. Assessing the impact of population stratification on genetic association studies. Nat Genet. 2004;36:388–393. doi: 10.1038/ng1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marchini J, Cardon LR, Phillips MS, Donnelly P. The effects of human population structure on large genetic association studies. Nat Genet. 2004;36:512–517. doi: 10.1038/ng1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clayton DG, Walker NM, Smyth DJ, Pask R, Cooper JD, Maier LM, et al. Population structure, differential bias and genomic control in a large-scale, case-control association study. Nat Genet. 2005;37:1243–1246. doi: 10.1038/ng1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heath SC, Gut IG, Brennan P, McKay JD, Bencko V, Fabianova E, et al. Investigation of the fine structure of European populations with applications to disease association studies. Eur J Hum Genet. 2008;16:1413–1429. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2008.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ioannidis JP, Boffetta P, Little J, O'Brien TR, Uitterlinden AG, Vineis P, et al. Assessment of cumulative evidence on genetic associations: interim guidelines. Int J Epidemiol. 2008;37:120–132. doi: 10.1093/ije/dym159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Daw EW, Heath SC, Wijsman EM. Multipoint oligogenic analysis of age-at-onset data with applications to Alzheimer disease pedigrees. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;64:839–851. doi: 10.1086/302276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li YJ, Scott WK, Hedges DJ, Zhang F, Gaskell PC, Nance MA, et al. Age at onset in two common neurodegenerative diseases is genetically controlled. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;70:985–993. doi: 10.1086/339815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li YJ, Oliveira SA, Xu P, Martin ER, Stenger JE, Scherzer CR, et al. Glutathione S-transferase omega-1 modifies age-at-onset of Alzheimer disease and Parkinson disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:3259–3267. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kölsch H, Linnebank M, Lütjohann D, Jessen F, Wüllner U, Harbrecht U, et al. Polymorphisms in glutathione S-transferase omega-1 and AD, vascular dementia, and stroke. Neurology. 2004;63:2255–2260. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000147294.29309.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li YJ, Scott WK, Zhang L, Lin PI, Oliveira SA, Skelly T, et al. Revealing the role of glutathione S-transferase omega in age-at-onset of Alzheimer and Parkinson diseases. Neurobiol Aging. 2006;27:1087–1093. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dartigues JF, Letenneur L. Genetic epidemiology of Alzheimer's disease. Curr Opin Neurol. 2000;13:385–9. doi: 10.1097/00019052-200008000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tan EK, Ho P, Cheng SY, Yih Y, Li HH, Fook-Chong S, Lee WL, Zhao Y. CALHM1 variant is not associated with Alzheimer's disease among Asians. Neurobiol Aging. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2009.05.008. (In press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Inoue K, Tanaka N, Yamashita F, Sawano Y, Asada T, Goto YI. The P86L common allele of CALHM1 does not influence risk for Alzheimer disease in Japanese cohorts. Am J Med Genet. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.31014. (In press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cui PJ, Zheng L, Cao L, Wang Y, Deng YL, Wang G, et al. CALHM1 P86L polymorphism is a risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease in the Chinese population. J Alzeimers Dis. 2010;19:31–35. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Harold D, Abraham R, Hollingworth P, Sims R, Gerrish A, Hamshere M, et al. Genome wide association indentifies variants at CLU and PICALM associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1088–1093. doi: 10.1038/ng.440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Holtzman DM. In vivo effects of ApoE and clusterin on amyloid-beta metabolism and neuropathology. J Mol Neurosci. 2004;23:247–54. doi: 10.1385/JMN:23:3:247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Small DH. Dysregulation of calcium homeostasis in Alzheimer's disease. Neurochem Res. 2009;34:1824–9. doi: 10.1007/s11064-009-9960-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marambaud P, Dreses-Werringloer U, Vingtdeux V. Calcium signaling in neurodegeneration. Mol Neurodegener. 2009;4:20. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-4-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lambert J-C, Grenier-Boley B, Chouraki V, Heath S, Zelenika D, Fievet N, et al. Implication of the immune system in Alzheimer's disease: evidence from Genome-wide pathway analysis. J Alzheimers Dis. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-100018. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.