Abstract

Objective

To investigate whether genome-wide association study (GWAS)–validated and GWAS-promising candidate loci influence magnetic resonance imaging measures and clinical Alzheimer’s disease (AD) status.

Design

Multicenter case-control study of genetic and neuroimaging data from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative.

Setting

Multicenter GWAS.

Patients

A total of 168 individuals with probable AD, 357 with mild cognitive impairment, and 215 cognitively normal control individuals recruited from more than 50 Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative centers in the United States and Canada. All study participants had APOE and genome-wide genetic data available.

Main Outcome Measures

We investigated the influence of GWAS-validated and GWAS-promising novel AD loci on hippocampal volume, amygdala volume, white matter lesion volume, entorhinal cortex thickness, parahippocampal gyrus thickness, and temporal pole cortex thickness.

Results

Markers at the APOE locus were associated with all phenotypes except white matter lesion volume (all false discovery rate–corrected P values < .001). Novel and established AD loci identified by prior GWASs showed a significant cumulative score–based effect (false discovery rate P=.04) on all analyzed neuroimaging measures. The GWAS-validated variants at the CR1 and PICALM loci and markers at 2 novel loci (BIN1 and CNTN5) showed association with multiple magnetic resonance imaging characteristics (false discovery rate P <.05).

Conclusions

Loci associated with AD also influence neuroimaging correlates of this disease. Furthermore, neuroimaging analysis identified 2 additional loci of high interest for further study.

Late-onset alzheimer disease (AD) is the most common cause of dementia and the fifth leading cause of death in Americans older than 65 years.1 The mechanisms underlying AD onset and progression remain largely unexplained. A study of twins2 has demonstrated a significant role for genetics in late-onset AD, with heritability estimates of 60% to 80%. Until recently, the only genetic variant consistently shown to influence AD risk and age at onset was APOE (OMIM 107741).3 New findings from genome-wide association studies (GWASs) identified 3 additional loci conferring risk for AD: CLU (OMIM 185430), PICALM (OMIM 603025), and CR1 (OMIM 120620).4,5 Other promising loci were also reported in these GWASs but did not achieve P values sufficient for genome-wide significance.

Multiple neuroimaging measures correlate with AD risk and progression. These measures also appear to have genetic under-pinnings, with heritability estimates ranging from 40% to 80%,6 and have been proposed as surrogate end points in biological research and clinical trials in AD.7,8 The demonstration that recently discovered genetic risk factors for AD also influence these neuroimaging traits would provide important confirmation of a role for these genetic variants and suggest mechanisms through which they might be acting.

We therefore investigated the genetics of AD-related neuroimaging measures using data collected as part of the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI). We investigated whether GWAS-validated and GWAS-promising candidate loci influence magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) measures and clinical status (cognitively normal, mild cognitive impairment [MCI] without progression to probable AD, MCI with progression to probable AD, and probable AD). Because of limitations in sample size and hence study power, we performed individual single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP)–based analyses and cumulative score–based analysis, which incorporated information from a collection of candidate SNPs.

METHODS

ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE NEUROIMAGING INITIATIVE

Participants were selected from the ADNI database (http://www.loni.ucla.edu/ADNI). The ADNI is a large, multisite, collaborative effort launched in 2003 by the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, the US Food and Drug Administration, private pharmaceutical companies, and nonprofit organizations as a public-private partnership aimed at testing whether serial MRI, positron emission tomography, other biological markers, and clinical and neuropsychological assessment can be combined to measure the progression of MCI and early AD. The principal investigator of ADNI is Michael Weiner, MD. ADNI is the product of many coinvestigators from a broad range of academic institutions and private corporations, with patients recruited from more than 50 sites across the United States and Canada. For more information, see http://www.adni-info.org. Data from the ADNI cohort were not used in either of the prior AD GWASs.4,5

STUDY PARTICIPANTS

Participants were screened, enrolled, and followed up prospectively according to the ADNI study protocol described in detail elsewhere.9 The degree of clinical severity for each participant was evaluated by an annual semistructured interview. This interview generated an overall Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) score and the CDR Sum of Boxes.10 The Mini-Mental State Examination11 and a neuropsychological battery were also conducted.

Participants were selected from the ADNI database if they were classified at baseline as (1) cognitively normal control individuals with a CDRscore of 0; (2) patients with MCI with Mini-Mental State Examination scores between 24 and 30, a subjective memory complaint verified by an informant, objective memory loss as measured by education-adjusted performance on the Logical Memory II subscale (delayed paragraph recall) of the Wechsler Memory Scale–Revised,12 a CDR score of 0.5, absence of significant levels of impairment in other cognitive domains, essentially preserved activities of daily living, an absence of dementia at the time of the baseline MRI scan, and classified as having the amnestic subtype of MCI based on the revised MCI criteria13; and (3) patients with AD who met criteria for probable AD14 (CDR score of 1).

Among 746 study participants who fulfilled quality control criteria for genotype data, 171 qualified for an AD diagnosis at baseline, 364 had MCI, and 205 were cognitively normal controls. Among 364 with baseline MCI, longitudinal follow-up identified 140 who converted to an AD diagnosis and 217 who did not. Three AD cases reverted to MCI status and 18 MCI cases reverted to control status. Removal of these individuals whose disease status reverted did not alter the presented results.

GENOTYPE DATA

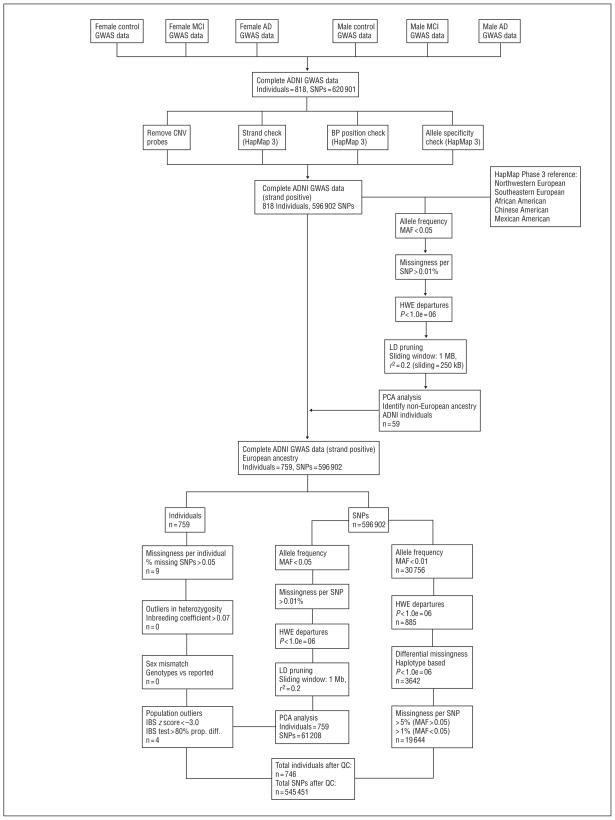

Individual-level genotype data in the ADNI database15 were downloaded and merged to form a single data set containing genome-wide information for 818 individuals. Genetic analyses were performed using PLINK version 1.07 (http://pngu.mgh.harvard.edu/~purcell/plink/). Filtering criteria applied to individuals and SNPs are shown in the Figure.

Figure.

Genotype data quality control for the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) genome-wide association study (GWAS) data set.

Single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNPs) may have met multiple filtering criteria. AD indicates Alzheimer disease; BP, blood pressure; CNV, copy number variation; HWE, Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium; IBS, identity by state; LD, linkage disequilibrium; MAF, minor allele frequency; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; PCA, principal component analysis; prop. diff., proportional between-individuals difference as determined by identity by state; and QC, quality control.

Population structure was assessed by performing principal component analysis on a subset of all SNPs selected using multiple criteria (Figure). We assigned genotype-determined ancestry by comparing ADNI patients and reference populations from HapMap Phase 3 data. To control for population stratification, only individuals clustering with European HapMap samples were retained for analysis.

Quality control of genotype data for analyzed individuals included filters for missingness, heterozygosity, and concordance between genotype-determined and reported sex. The SNP quality control included filters for minor allele frequency (MAF), missingness, Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium, and differential missingness by case-control status. A total of 746 individuals passing quality control criteria were reclustered by performing principal component analysis.

MRI DATA

The ADNI MRIs were acquired at multiple sites using a GE Health-care (Buckinghamshire, England), Siemens Medical Solutions USA (Atlanta, Georgia), or Philips Electronics 1.5 T system (Philips Electronics North America; Sunnyvale, California). Two high-resolution T1-weighted volumetric magnetization-prepared 180° radiofrequency pulses and rapid gradient-echo scans were collected for each study participant, and the raw Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine images were downloaded from the public ADNI site (http://www.loni.ucla.edu/ADNI/Data/index.shtml). Parameter values can be found at http://www.loni.ucla.edu/ADNI/Research/Cores/.

All MRIs were processed according to previously published methods.8 Briefly, all MRIs were processed using the Free Surfer version 4.1.0 software package (http://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu). A single magnetization-prepared 180° radiofrequency and rapid gradient-echo acquisition for each participant was normalized for intensity in homogeneities, nonbrain tissue removed, and subcortical white matter and deep gray matter volumetric structures segmented.16,17 Intensity gradients were followed outward from the white matter surface to find the gray matter surface (gray–cerebrospinal fluid boundary).18,19 Cortical thickness measurements were then obtained by calculating the distance between the gray and white matter surfaces at each point (per hemisphere) across the entire cortical surface.19 In our analyses, the cortical thickness and right-brain/left-brain volumes were averaged. To account for differences in head size, the total volume for each subcortical region of interest was corrected using a previously validated estimate of the total intracranial volume.19,20

SNP SELECTION

Four GWAS-validated AD loci were selected for analysis: APOE, CLU, PICALM, and CR1. Genotypes of APOE were separately obtained via targeted genotyping, whereas SNPs showing the strongest degree of association in published GWASs4,5 were selected for analysis: rs11136000 at CLU, rs3851179 at PICALM, and rs1408077 at CR1. We selected for additional analysis all GWAS-promising SNPs with P < 1 × 10−5 in the prior GWASs.4,5 When multiple variants in moderate to high linkage disequilibrium at 1 locus (r2 > 0.6) were reported to be associated with AD, only the SNP with the lowest P value was selected for analysis in the present study. Sixteen SNPs were chosen based on these criteria (Table 1).

Table 1.

Prior GWASs and Current Study (Ordinal Logistic Regression) Results for Analyzed SNPsa

| SNP | Gene | GWAS OR | Included in Score? | Score Weight | Ordinal Logistic Regression (ADNI) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI)FDR-Corrected | P Value | |||||

| rs11136000 | CLU | 0.84 | Yes | −0.1744 | 0.97 (0.80–1.17) | .76 |

| rs3851179 | PICALM | 0.85 | Yes | −0.1625 | 0.99 (0.81–1.20) | .88 |

| rs1408077 | CR1 | 1.17 | Yes | 0.1570 | 1.27 (1.03–1.63) | .02 |

| rs9384428 | ARID1B | 1.14 | No | NA | 0.93 (0.77–1.14) | .49 |

| rs1539053 | DAB1 | 0.88 | No | NA | 0.95 (0.76–1.16) | .51 |

| rs1157242 | KCNU1 | 1.17 | No | NA | 0.98 (0.75–1.25) | .89 |

| rs676309 | MS4A4E | 1.14 | No | NA | 1.07 (0.88–1.31) | .50 |

| rs662196 | MS4A6A | 0.88 | No | NA | 0.94 (0.76–1.14) | .48 |

| rs7561528 | BIN1 | 1.17 | Yes | 0.1570 | 1.29 (1.03–1.62) | .03 |

| rs9446432 | C6orf155 | 1.28 | No | NA | 0.97 (0.68–1.38) | .86 |

| rs10501927 | CNTN5 | 1.18 | Yes | 0.1655 | 1.25 (1.03–1.62) | .03 |

| rs11894266 | SSB | 0.86 | No | NA | 0.97 (0.81–1.17) | .77 |

| rs11952762 | DTWD2 | 1.18 | No | NA | 1.12 (0.70–1.83) | .62 |

| rs12201301 | C6orf205 | 0.83 | No | NA | 1.02 (0.63–1.63) | .95 |

| rs10499889 | SEMA3D | 1.15 | No | NA | 1.05 (0.87–1.27) | .63 |

| rs8055533 | KIAA0350 | 0.89 | No | NA | 1.02 (0.83–1.25) | .84 |

NEUROIMAGING MEASURE SELECTION

Six neuroimaging measures were chosen for analysis on the basis of their established role in predicting AD risk and progression: hippocampal volume, amygdala volume, white matter lesion (WML) volume, entorhinal cortex thickness (ECT), parahippocampal gyrus thickness, and temporal pole cortex thickness (TPT).21–25 All analyzed neuroimaging measures were highly associated with AD in case-control analysis (P < 1 × 10−4 for all). However, correlation matrix analysis (Table 2) revealed limited association between measures (correlation coefficient range, −0.38 to 0.75), suggesting that independent analysis was needed for association with genetic variants.

Table 2.

Correlation Matrix for Analyzed Neuroimaging MRI Measuresa

| Hippocampal Volume | Amygdala Volume | WML Volume | Entorhinal Cortex Thickness | Parahippocampal Gyrus Thickness | Temporal Pole Thickness | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hippocampal volume | P < .001 | P < .001 | P < .001 | P < .001 | P < .001 | |

| Amygdala volume | 0.7501 | P < .001 | P < .001 | P < .001 | P < .001 | |

| WML volume | −0.3830 | −0.2312 | P < .001 | P < .001 | P < .001 | |

| Entorhinal cortex thickness | 0.6509 | 0.6348 | −0.3083 | P <.001 | P <.001 | |

| Parahippocampal gyrus thickness | 0.4866 | 0.4355 | −0.3264 | 0.5401 | P <.001 | |

| Temporal pole thickness | 0.5330 | 0.5274 | −0.2931 | 0.7183 | 0.4555 |

Abbreviations: MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; WML, white matter lesion.

Correlation coefficients (Spearman) and corresponding P values for comparison of analyzed MRI measures are shown.

GENETIC ASSOCIATION ANALYSIS

Genotype data were analyzed using an additive model, with odds ratios (ORs) or regression coefficients expressing the effect of each copy of the reference allele. Analyses of diagnostic categories (AD, MCI converters, MCI nonconverters, and controls) used an ordinal logistic regression model. Analyses of neuroimaging measures used linear regression. Continuous measures with skewed distributions were log transformed. All analyses included age, sex, history of hypertension, APOE genotype (number of ε2 and ε4 copies), alcohol abuse (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders [Fourth Edition]26 criteria), and smoking status (ever smoker) as covariates. Education level was adjusted for according to number of school years attended (<13, 13–16, or >16 years). Population stratification was adjusted for by incorporating the first 2 principal components as covariates. Neuroimaging analysis was performed independent of diagnostic category. Because Bonferroni correction was inappropriate owing to the nonindependence of tests, we used the false discovery rate (FDR) according to the method developed by Hochberg and Benjamini27 to control for multiple hypothesis testing. Statistical significance was defined for FDR-corrected P < .05.

POWER CALCULATIONS FOR NEUROIMAGING ANALYSIS

We determined statistical power for identification of the association between analyzed variants and neuroimaging measures at a conservative α = .001. To do so, we used the Genetic Power Calculator (http://pngu.mgh.harvard.edu/~purcell/gpc/).28

SCORE-BASED ANALYSIS

Combined effects of non-APOE candidate SNPs were evaluated using a cumulative score–based method that was previously used to assess the cumulative effect of loci affecting lipid levels,29 risk of myocardial infarction,30 and blood pressure.31 Under this model each individual is assigned a score determined by multiplying the number of allele copies for SNPs of interest by a prespecified score weight. Score weights were based on β-coefficients extracted from case-control results from published GWAS reports4,5 (Table 1). Contributors to the genetic risk score included previously validated loci from GWASs (CLU, PICALM, and CR1) and those SNPs achieving adjusted significance (FDR-corrected P < .05) in our ordinal logistic regression analysis (BIN1 and CNTN5). Score analysis performed without BIN1 and CNTN5 (data not shown) did not alter the results. Contributions from individual SNPs were summed to obtain a single genetic risk score, which was divided into quartiles for normalization. Single-SNP and score-based ordinal logistic regression results were analyzed using a maximum-likelihood method to compare predictive power for disease status.

RESULTS

GENETIC DATA QUALITY CONTROL

A total of 818 individuals enrolled had genotype data available for analysis. Of these, 72 were excluded by quality control filters (Figure), whereas our image-processing tools failed to produce good-quality results on the MRIs of 6 individuals. Therefore, we analyzed 740 individuals with genotype and MRI data that met filtering criteria (Table 3). Filtering of genome-wide data generated a final analyzed data set that included 545 451 SNPs (Figure). Population stratification was assessed by computing genomic inflation factors for all phenotypes (diagnosis and neuroimaging measurements): all values were lower than 1.005 after correction for principal components.

Table 3.

Baseline Demographic, Clinical, and Neuroimaging Characteristics of Study Participantsa

| Characteristic | All Participants (N=740) | Cognitively Normal Controls (n=215) | MCI Nonconverters (n=217) | MCI Converters (n=140) | Patients With Alzheimer Disease (n=168) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prospective follow-up time, median (IQR), mo | 12 (6–24) | 12 (6–24) | 12 (6–24) | 18 (6–24) | 12 (6–24) |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 75.3 (6.9) | 75.9 (5.5) | 75.3 (7.4) | 74.6 (6.8) | 75.5 (7.7) |

| Male sex, No. (%) | 303 (40.9) | 97 (45.1) | 74 (34.1) | 55 (39.3) | 81 (48.2) |

| Education level, median (IQR), y | 16 (14–18) | 16 (14–18) | 16 (13–18) | 16 (14–18) | 16 (12–17) |

| History of hypertension, No. (%) | 348 (47.0) | 97 (45.1) | 102 (47.0) | 69 (49.3) | 86 (51.2) |

| Smoking, No. (%) | 289 (39.0) | 78 (36.3) | 91 (41.9) | 55 (39.3) | 67 (39.9) |

| Alcohol abuse, No. (%) | 30 (4.1) | 5 (2.3) | 8 (3.7) | 7 (5.0) | 10 (5.9) |

| APOE ε2, minor allele frequency | 0.042 | 0.070 | 0.039 | 0.021 | 0.027 |

| APOE ε4, minor allele frequency | 0.367 | 0.142 | 0.290 | 0.432 | 0.430 |

| GDS score, median (IQR) | 1 (0–2) | 0 (0–1) | 1 (0–2) | 1 (1–2) | 1 (1–2) |

| ADAS-COG score, median (IQR) | 10.7 (6.8–15.0) | 6.0 (4.0–8.0) | 10.7 (7.3–13.0) | 13.0 (10.7–15.5) | 18.0 (14.2–22.2) |

| Mini-Mental State Examination score, median (IQR) | 27 (25–29) | 29 (29–30) | 28 (26–29) | 27 (25–28) | 23 (22–25) |

| Clinical Dementia Rating Sum of Boxes, median (IQR) | 1.5 (0.0–3.0) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 1.5 (1.0–2.0) | 2.0 (1.0–2.5) | 4.0 (3.5–5.0) |

| White matter lesion volume, median (IQR), cm3 | 4.7 (3.2–7.4) | 4.0 (2.9–5.9) | 4.4 (3.1–7.5) | 5.1 (3.7–7.0) | 5.9 (4.1–10.2) |

| Amygdala volume, mean (SD), cm3 | 1.25 (0.22) | 1.38 (0.19) | 1.28 (0.20) | 1.16 (0.19) | 1.11 (0.18) |

| Hippocampal volume, mean (SD), cm3 | 3.23 (0.59) | 3.66 (0.50) | 3.28 (0.52) | 2.95 (0.48) | 2.85 (0.49) |

| Parahippocampal gyrus cortical thickness, mean (SD), mm | 2.34 (0.32) | 2.49 (0.28) | 2.36 (0.33) | 2.27 (0.27) | 2.18 (0.32) |

| Temporal pole cortical thickness, mean (SD), cm3 | 3.48 (0.13) | 3.66 (0.26) | 3.52 (0.32) | 3.37 (0.36) | 3.29 (0.39) |

| Entorhinal cortical thickness, mean (SD), mm | 3.09 (0.47) | 3.40 (0.30) | 3.16 (0.45) | 2.93 (0.43) | 2.73 (0.43) |

Abbreviations: ADAS-COG, Alzheimer Disease Assessment Scale Cognitive Subscale; GDS, Geriatric Depression Scale; IQR, interquartile range; MCI, mild cognitive impairment.

All reported values (except follow-up time) refer to baseline ascertainment procedures. All volumetric measurements were adjusted to intracranial volume. Reported follow-up times were assessed on December 1, 2009.

STATISTICAL POWER

We had more than 0.95 power for discovery of associations between APOE and neuroimaging traits (effect size, 5% of variance; MAF, 0.37). Power for discovery of associations with individual non-APOE loci was below 0.30 (effect size, 1% of variance; MAF range, 0.10–0.40). We therefore chose to pool genetic effects using a validated score-based model.28–30 Statistical power for the score-based analyses was approximately 0.80 (effect size, 3% of variance).

GENETIC RISK FACTORS FOR AD

We sought to extend known associations of APOE, CLU, PICALM, and CR1 with AD using a logistic regression model across 4 diagnostic categories: disease-free controls, MCI nonconverters, MCI converters, and AD patients (Table 4). The strongest association with clinical diagnosis was shown by APOE (OR, 2.07; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.67–2.56; FDR-corrected P< 1 × 10−6). Of the 3 previously confirmed non-APOE AD loci, only CR1 was replicated in the ADNI data set, with SNP rs1408077 showing a significant association (OR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.03–1.63; FDR-corrected P=.02). Among GWAS-promising SNPs with adjusted P < 1 × 10−5 in GWASs, 2 variants showed significant association in our analysis: rs10501927 at CNTN5 (OR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.02–1.53; FDR-corrected P=.03) and rs7561528 at BIN1 (1.29; 1.03–1.62; FDR-corrected P=.03).

Table 4.

| SNP | Gene | OR (95% CI) | P Value | FDR-Corrected P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| APOE locus ε4 | APOE (ε4) | 2.07 (1.67–2.56) | <1 × 10−6 | <1 × 10−6 |

| Validated loci | ||||

| rs11136000 | CLU | 0.97 (0.80–1.17) | .75 | .76 |

| rs3851179 | PICALM | 0.99 (0.81–1.20) | .87 | .88 |

| rs1408077 | CR1 | 1.27 (1.03–1.63) | .02 | .02 |

| Novel candidate loci | ||||

| rs10501927 | CNTN5 | 1.25 (1.02–1.53) | .03 | .03 |

| rs7561528 | BIN1 | 1.29 (1.03–1.62) | .03 | .03 |

| Genetic risk score (cumulative effect) | ||||

| Genetic risk score quartiles | 1.14 (1.04–1.25) | .001 | .001 | |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; FDR, false discovery rate; OR, odds ratio; SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism.

SNPs were selected based on results of prior genome-wide association studies4,5 with P < 1 × 10−5. Results are not shown for 11 SNPs at novel candidate loci with P > .05. The genetic risk score includes all (5 of 16) SNPs outside the APOE locus achieving P < .05 in ordinal logistic regression. All analyses are adjusted for age, sex, history of hypertension, education level (<13, 13–16, or >16 years), alcohol abuse, smoking (ever smoker status), and principal components 1 and 2. Analyses for SNPs outside the APOE locus were also adjusted for APOE genotypes (number of ε2 and ε4 copies).

Clinical diagnosis defined as cognitively normal controls, mild cognitive impairment not converted to Alzheimer disease, mild cognitive impairment conversion to Alzheimer disease, and Alzheimer disease.

The genetic risk score included the following SNPs: rs11136000 (CLU), rs3851179 (PICALM), rs1408077 (CR1), rs10501927 (CNTN5), and rs7561528 (BIN1). Ordinal logistic regression revealed an association between risk score quartiles and diagnostic status (OR, 1.14; 95% CI, 1.04–1.25; FDR-corrected P=.001). Comparison of predictive performance between score-based analysis and individual SNP analyses favored the cumulative effects model (P=.03). To account for the possible heterogeneity in genetic and imaging risk profiles within the group whose cases did not convert to MCI, we repeated all analyses after removal of these individuals and observed similar results (data not shown).

GENETIC RISK FACTORS FOR MRI MEASURES

We investigated the influence of APOE genotype and genetic risk score profile on each MRI measure (Table 5). The APOE ε4 allele was strongly associated with all measures except WML volume (P=.44). Genetic risk score quartiles predicted increasing severity of all MRI measures (FDR-corrected P = .04). On analyzing score-contributing SNPs individually, we identified associations for the GWAS-validated SNPs rs1408077 at CR1 with ECT (FDR-corrected P=.03) and rs3851179 at PICALM with hippocampal volume and ECT (FDR-corrected P=.05 and FDR-corrected P=.01, respectively). Furthermore, we identified associations for GWAS-promising SNPs rs10501927 at CNTN5 with WML volume, parahippocampal gyrus thickness, TPT, and ECT (FDR-corrected P =.002, P =.05, P =.02, and P =.02, respectively) and for rs7561528 at BIN1 with TPT and ECT (FDR-corrected P=.03 and P =.01, respectively).

Table 5.

Influence of Single SNPs and Cumulative Genetic Risk Score on Neuroimaging Measuresa

| SNP | Gene | Coefficient (SE) | P Value | FDR-Corrected P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White matter lesion volume | ||||

| ε4 | APOE | 0.025 (0.033) | .44 | .44 |

| rs11136000 | CLU | −0.030 (0.031) | .31 | .32 |

| rs3851179 | PICALM | −0.005 (0.032) | .97 | .98 |

| rs1408077 | CR1 | 0.028 (0.039) | .45 | .46 |

| rs10501927 | CNTN5 | 0.119 (0.037) | .002 | .002 |

| rs7561528 | BIN1 | 0.017 (0.032) | .50 | .51 |

| Genetic risk score quartiles | 0.043 (0.015) | .04 | .04 | |

| Hippocampal volume | ||||

| ε4 | APOE | −0.240 (0.030) | 0.9 × 10−14 | 1.3 × 10−14 |

| rs11136000 | CLU | −0.019 (0.030) | .78 | .79 |

| rs3851179 | PICALM | 0.061 (0.029) | .04 | .05 |

| rs1408077 | CR1 | −0.037 (0.038) | .32 | .32 |

| rs10501927 | CNTN5 | −0.046 (0.036) | .17 | .19 |

| rs7561528 | BIN1 | −0.055 (0.031) | .06 | .08 |

| Genetic risk score quartiles | −0.099 (0.014) | .001 | .002 | |

| Amygdala volume | ||||

| ε4 | APOE | −0.079 (0.012) | 3.6 × 10−11 | 3.9 × 10−11 |

| rs11136000 | CLU | −0.018 (0.012) | .11 | .12 |

| rs3851179 | PICALM | 0.009 (0.012) | .47 | .47 |

| rs1408077 | CR1 | −0.017 (0.014) | .21 | .22 |

| rs10501927 | CNTN5 | −0.018 (0.013) | .19 | .19 |

| rs7561528 | BIN1 | −0.020 (0.012) | .09 | .10 |

| Genetic risk score quartiles | 0.043 (0.015) | .02 | .02 | |

| Entorhinal cortex thickness | ||||

| ε4 | APOE | −0.127 (0.026) | 8.7 × 10−7 | 9.1 × 10−7 |

| rs11136000 | CLU | −0.011 (0.025) | .65 | .67 |

| rs3851179 | PICALM | 0.066 (0.021) | .01 | .01 |

| rs1408077 | CR1 | −0.067 (0.031) | .03 | .03 |

| rs10501927 | CNTN5 | −0.067 (0.025) | .02 | .02 |

| rs7561528 | BIN1 | −0.121 (0.025) | .004 | .01 |

| Genetic risk score quartiles | −0.048 (0.011) | 7.9 × 10−4 | 8.4 × 10−4 | |

| Parahippocampal gyrus cortex thickness | ||||

| ε4 | APOE | −0.063 (0.017) | 3.3 × 10−4 | 3.8 × 10−4 |

| rs11136000 | CLU | 0.007 (0.017) | .66 | .67 |

| rs3851179 | PICALM | 0.014 (0.017) | .29 | .30 |

| rs1408077 | CR1 | 0.0004 (0.021) | .98 | .98 |

| rs10501927 | CNTN5 | −0.040 (0.019) | .05 | .05 |

| rs7561528 | BIN1 | −0.019 (0.017) | .24 | .24 |

| Genetic risk score quartiles | −0.022 (0.010) | .04 | .04 | |

| Temporal pole cortex thickness | ||||

| ε4 | APOE | −0.061 (0.019) | .002 | .004 |

| rs11136000 | CLU | −0.011 (0.018) | .50 | .51 |

| rs3851179 | PICALM | 0.033 (0.017) | .06 | .06 |

| rs1408077 | CR1 | −0.031 (0.024) | .12 | .14 |

| rs10501927 | CNTN5 | −0.051 (0.022) | .02 | .02 |

| rs7561528 | BIN1 | −0.041 (0.019) | .02 | .03 |

| Genetic risk score quartiles | −0.025 (0.009) | 8.2 × 10−4 | .001 | |

Abbreviations: FDR, false discovery rate; SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism.

SNPs were selected based on results of prior genome-wide association studies4,5 with P < .001. Results are not shown for 11 SNPs at novel candidate loci with P > .05. The genetic risk score includes all (5 of 16) SNPs outside the APOE locus achieving P < .05 in ordinal logistic regression. All analyses are adjusted for age, sex, history of hypertension, education level (<13, 13–16, or >16 years), alcohol abuse, smoking (ever smoker status), and principal components 1 and 2. Analyses for SNPs outside the APOE locus were also adjusted for APOE genotypes (number of ε2 and ε4 copies).

COMMENT

Our results indicate that APOE and other previously validated loci for AD affect clinical diagnosis of AD and neuroimaging measures associated with disease. These findings suggest that sequence variants that modulate AD risk in recent GWASs may act through their influence on neuroimaging measures. Furthermore, our genetic analysis of neuroimaging traits identified BIN1 and CNTN5 as genes of heightened interest for their relationship with AD, prioritizing these targets for further study.

Among non-APOE AD loci that have emerged from GWASs, only the CR1 locus was significantly associated with disease status. Failure to extend previous findings for CLU and PICALM is likely because of the limited sample size of the ADNI cohort. Nonetheless, our genetic risk score was associated in a dose-dependent manner with clinical diagnosis and clearly outperformed individual SNP models. This finding is consistent with a biological role for at least some, if not all, of the incorporated loci. Interestingly, the inclusion of previously un-validated loci at BIN1 and CNTN5 (albeit supported by P < 1 × 10−5 in the previous GWASs) did not degrade the performance of the genetic score, further supporting a role for these loci in AD.

The genetic risk score quartiles correlated with every examined neuroimaging trait, consistent with the underlying hypothesis that these traits are, at least in part, determined by genome sequence at these loci. This finding offers parallel evidence that the included genes influence biological processes underlying development of AD.

Among GWAS-validated loci, APOE, PICALM, and CR1 genotypes influenced neuroimaging measures, whereas CLU did not. The robust effect of APOE was seen across all measures except WML volume, whereas the effect of PICALM was restricted to hippocampal volume and ECT, and the effect of CR1 was restricted to ECT. These findings raise the possibility that the biological effects of these genes may be relatively confined to 1 neuroimaging trait and hence may offer clues to the mechanisms through which particular genetic variants might influence AD risk.

Two loci, identified as GWAS-promising in previous AD studies, showed association with neuroimaging measures. CNTN5 variation was associated with WML, ECT, parahippocampal gyrus thickness, and TPT, whereas BIN1 was associated with ECT and TPT. These genes encode proteins involved in neurite growth,32 presynaptic cyto-skeleton structure integrity,31 and fission of synaptic vesicles.33 Brain-specific isoforms and expression patterns have been reported for BIN34 and CNTN5.35 Although our results for these loci can only be considered preliminary, they may help prioritize targets for future genetic studies and GWASs in AD, particularly given their association with neuroimaging correlates of AD and disease status.

The crucial limitations of our study arise from its small sample size. Because of restricted power, we were forced to constrain our analysis to SNPs and loci with high prior probabilities of association with AD and imaging traits, based on their status as either validated (APOE, CLU, PICALM, and CR1) or promising (CNTN5 and BIN1) genetic risk factors. Our power also limits the conclusions we can draw about observed differential genetic effects on neuroimaging traits. For example, although the absence of an effect of CR1 on hippocampal volume may reflect important biology, it is also possible that an effect could be detected with increased power.

In summary, we have shown that established and candidate AD genes have a role in 6 neuroimaging traits linked to AD. Furthermore, 2 promising genes from prior AD GWASs, CNTN5 and BIN1, are also associated with these neuroimaging measures, which heightens their interest as novel AD loci. These genes may act selectively, influencing only 1 or a few established AD-related MRI measures. Future studies are required to replicate and expand these findings.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: Data collection and sharing for this project was funded by the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (grant U01 AG024904). The ADNI is funded by the National Institute on Aging (NIA), the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, and through generous contributions from the following: Abbott Laboratories, AstraZeneca AB, Bayer Schering Pharma AG, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eisai Global Clinical Development, Elan Corporation Plc, Genentech Inc, GE Health-care, GlaxoSmithKline, Innogenetics, Johnson and Johnson Services Inc, Eli Lilly and Company, Medpace Inc, Merck and Co Inc, Novartis International AG, Pfizer Inc, F. Hoffman-La Roche Ltd, Schering-Plough Corporation, CCBR-SYNARC Inc, and Wyeth Pharmaceuticals, as well as nonprofit partners the Alzheimer’s Association and Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation, with participation from the US Food and Drug Administration. Private sector contributions to the ADNI are facilitated by the Foundation for the NIH. The grantee organization is the Northern California Institute for Research and Education Inc, and the study is coordinated by the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study at the University of California, San Diego. The ADNI data are disseminated by the Laboratory for Neuro Imaging at the University of California, Los Angeles. This research was also supported by the NIH (grants P30 AG010129 and K01 AG030514) and the Dana Foundation. Drs Biffi and Anderson receive research support from the American Heart Association/Bugher Foundation Centers for Stroke Prevention Research (grant 0775010N). Dr Desikan receives research support from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR) (grant P41-RR14075), the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (grant R01 EB006758), the NIA (grant AG02238), and the National Institute for Neurological Disorders and Stroke (grant R01 NS052585-01). Dr Sabuncu receives research support from the NCRR (grant P41-RR14075), the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (grant R01EB006758), the NIA (grant AG02238), and the National Institute for Neurological Disorders and Stroke (grant R01 NS052585-01). Mr Schmansky receives research support from the NCRR (grant P41-RR14075), the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (grant R01EB006758), the NIA (grant AG02238), the National Institute for Neurological Disorders and Stroke (grant R01 NS052585-01), and The Autism and Dyslexia Project, funded by the Ellison Medical Foundation. Dr Salat is funded by and receives research support from the NIH (grants R01 AG028676-01A1, R01 NS042861-06A1, 5P41 RR14075-11, R21 DA026104, and R01 AG026484-02). Dr Rosand is funded by the NIH (grants R01 NS052585 and R01 NS059727), the American Heart Association/Bugher Foundation Centers for Stroke Prevention Research (grant 0775010N), the Deane Institute for Integrative Study of Atrial Fibrillation and Stroke, and the NCRR (grant U54 RR020278). This work was supported by the National Center for Research Resources (grants P41-RR14075 and R01 RR 16594-01A1); the NCRR Biomedical Informatics Research Network Morphometric Project (grants BIRN002 and U24 RR021382); the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (grant R01 EB001550); the Mental Illness and Neuroscience Discovery Institute; and the NIA (grants P50 AG05681, P01AG03991, and AG021910). Data collection and sharing for this project were funded by the the ADNI/NIH (principal investigator: Michael Weiner; grant U01 AG024904]) and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (Open Access Series of Imaging Studies project). The ADNI is funded by the NIA, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, and through generous contributions from the following: Pfizer Inc, Wyeth Research, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly and Company, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck & Co Inc, Astra-Zeneca AB, Novartis International AG, Alzheimer’s Association, Eisai Global Clinical Development, Elan Corporation Plc, Forest Laboratories Inc, and the Institute for the Study of Aging, with participation from the US Food and Drug Administration. Industry partnerships are coordinated through the Foundation for the NIH. The grantee organization is the Northern California Institute for Research and Education, and the study is coordinated by the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study at the University of California, San Diego. ADNI data are disseminated by the Laboratory of Neuro Imaging at the University of California, Los Angeles. This research was also supported by the American Heart Association/Bugher Foundation Centers for Stroke Prevention Research (grant 0774010N); the Deane Institute for Integrative Study of Atrial Fibrillation and Stroke (grant P41-RR14075); the National Center for Research Resources; the National Institute for Biomedical Imaging and Bio-engineering (grant R01 EB006758); the NIA (grant AG02238); and the National Institute for Neurological Disorders and Stroke (grants R01 NS052585-01 and R01 NS059727).

Footnotes

Group Information: A list of the ADNI investigators appears at http://www.loni.ucla.edu/ADNI/Collaboration/ADNI_Manuscript_Citations.pdf.

Financial Disclosure: None reported.

Additional Information: As such, the investigators within the ADNI contributed to the design and implementation of the ADNI and/or provided data but did not participate in analysis or writing of this report.

Author Contributions: Drs Biffi and Anderson contributed equally to this article. Drs Biffi, Anderson, Desikan, Sabuncu, and Rosand had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Study concept and design: Biffi, Anderson, Desikan, Sabuncu, Cortellini, Salat, and Rosand. Acquisition of data: Biffi, Anderson, and Salat. Analysis and interpretation of data: Biffi, Anderson, Desikan, Sabuncu, Schmansky, and Salat. Drafting of the manuscript: Biffi, Anderson, and Salat. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Biffi, Anderson, Desikan, Sabuncu, Cortellini, Schmansky, Salat, and Rosand. Statistical analysis: Biffi, Anderson, Desikan, and Sabuncu. Obtained funding: Rosand. Administrative, technical, and material support: Cortellini, Schmansky, Salat, and Rosand. Study supervision: Desikan, Cortellini, Salat, and Rosand.

Additional Contributions: We thank Steven M. Greenberg, MD, PhD, for additional critical review of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Alzheimer’s Association. 2009 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2009;5(3):234–270. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ertekin-Taner N. Genetics of Alzheimer’s disease: a centennial review. Neurol Clin. 2007;25(3):611–667. v. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2007.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim J, Basak JM, Holtzman DM. The role of apolipoprotein E in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron. 2009;63(3):287–303. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.06.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harold D, Abraham R, Hollingworth P, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies variants at CLU and PICALM associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Genet. 2009;41(10):1088–1093. doi: 10.1038/ng.440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lambert J-C, Heath S, Even G, et al. European Alzheimer’s Disease Initiative Investigators. Genome-wide association study identifies variants at CLU and CR1 associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Genet. 2009;41(10):1094–1099. doi: 10.1038/ng.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peper JS, Brouwer RM, Boomsma DI, Kahn RS, Hulshoff Pol HE. Genetic influences on human brain structure: a review of brain imaging studies in twins. Hum Brain Mapp. 2007;28(6):464–473. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hill D. Neuroimaging to assess safety and efficacy of AD therapies. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2010;19(1):23–26. doi: 10.1517/13543780903381320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Desikan RS, Cabral HJ, Fischl B, et al. Temporoparietal MR imaging measures of atrophy in subjects with mild cognitive impairment that predict subsequent diagnosis of Alzheimer disease. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2009;30(3):532–538. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Petersen RC, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, et al. Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI): clinical characterization. Neurology. 2010;74(3):201–209. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181cb3e25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993;43(11):2412–2414. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.11.2412-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wechsler D. Wechsler Memory Scale—Revised. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Petersen RC. Mild cognitive impairment as a diagnostic entity. J Intern Med. 2004;256(3):183–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein MF, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force. Neurology. 1984;34(7):939–944. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Potkin SG, Guffanti G, Lakatos A, et al. Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Hippocampal atrophy as a quantitative trait in a genome-wide association study identifying novel susceptibility genes for Alzheimer’s disease. [Accessed March 26, 2010.];PLoS One. 2009 4(8):e6501. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006501. http://www.plosone.org/article/info:doi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0006501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Dale AM, Fischl B, Sereno MI. Cortical surface-based analysis, I: segmentation and surface reconstruction. Neuroimage. 1999;9(2):179–194. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1998.0395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fischl B, Sereno MI, Dale AM. Cortical surface-based analysis, II: inflation, flattening, and a surface-based coordinate system. Neuroimage. 1999;9(2):195–207. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1998.0396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fischl B, Salat DH, Busa E, et al. Whole brain segmentation: automated labeling of neuroanatomical structures in the human brain. Neuron. 2002;33(3):341–355. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00569-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fischl B, Dale AM. Measuring the thickness of the human cerebral cortex from magnetic resonance images. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(20):11050–11055. doi: 10.1073/pnas.200033797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buckner RL, Head D, Parker J, et al. A unified approach for morphometric and functional data analysis in young, old, and demented adults using automated atlas-based head size normalization: reliability and validation against manual measurement of total intracranial volume. Neuroimage. 2004;23(2):724–738. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karas GB, Burton EJ, Rombouts SA, et al. A comprehensive study of gray matter loss in patients with Alzheimer’s disease using optimized voxel-based morphometry. Neuroimage. 2003;18(4):895–907. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(03)00041-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Appel J, Potter E, Bhatia N, et al. Association of white matter hyperintensity measurements on brain MR imaging with cognitive status, medial temporal atrophy, and cardiovascular risk factors. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2009;30(10):1870–1876. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guo X, Wang Z, Li K, et al. Voxel-based assessment of gray and white matter volumes in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurosci Lett. 2010;468(2):146–150. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.10.086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Henneman WJ, Sluimer JD, Barnes J, et al. Hippocampal atrophy rates in Alzheimer disease: added value over whole brain volume measures. Neurology. 2009;72(11):999–1007. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000344568.09360.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Raji CA, Lopez OL, Kuller LH, Carmichael OT, Becker JT. Age, Alzheimer disease, and brain structure. Neurology. 2009;73(22):1899–1905. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181c3f293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hochberg Y, Benjamini Y. More powerful procedures for multiple significance testing. Stat Med. 1990;9(7):811–818. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780090710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Purcell S, Cherny SS, Sham PC. Genetic Power Calculator: design of linkage and association genetic mapping studies of complex traits. Bioinformatics. 2003;19(1):149–150. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/19.1.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kathiresan S, Willer CJ, Peloso GM, et al. Common variants at 30 loci contribute to polygenic dyslipidemia. Nat Genet. 2009;41(1):56–65. doi: 10.1038/ng.291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kathiresan S, Voight BF, Purcell S, et al. Myocardial Infarction Genetics Consortium; Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium. Genome-wide association of early-onset myocardial infarction with single nucleotide polymorphisms and copy number variants. Nat Genet. 2009;41(3):334–341. doi: 10.1038/ng.327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Newton-Cheh C, Johnson T, Gateva V, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies eight loci associated with blood pressure. Nat Genet. 2009;41:666–676. doi: 10.1038/ng.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Butler MH, David C, Ochoa GC, et al. Amphiphysin II (SH3P9; BIN1), a member of the amphiphysin/Rvs family, is concentrated in the cortical cytomatrix of axon initial segments and nodes of ranvier in brain and around T tubules in skeletal muscle. J Cell Biol. 1997;137(6):1355–1367. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.6.1355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ren G, Vajjhala P, Lee JS, Winsor B, Munn AL. The BAR domain proteins: molding membranes in fission, fusion, and phagy. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2006;70(1):37–120. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.70.1.37-120.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wechsler-Reya R, Sakamuro D, Zhang J, et al. Structural analysis of the human BIN1 gene: evidence for tissue-specific transcriptional regulation and alternate RNA splicing. Biol Chem. 1997;272(50):31453–31458. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.50.31453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kamei Y, Takeda Y, Teramoto K, Tsutsumi O, Taketani Y, Watanabe K. Human NB-2 of the contactin subgroup molecules: chromosomal localization of the gene (CNTN5) and distinct expression pattern from other subgroup members. Genomics. 2000;69(1):113–119. doi: 10.1006/geno.2000.6310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]