Abstract

Ever since monoclonal antibodies were produced in 1975 with mouse myeloma cells there has been interest in developing human myeloma cultures for the production of monoclonal antibodies. However, despite multiple attempts, no human myeloma line suitable for hybridoma production has been described. Here we report the derivation of a hypoxanthine–aminopterin–thymidine-sensitive and ouabain-resistant human myeloma cell line (Karpas 707H) that contains unique genetic markers. We show that this line is useful for the generation of stable human hybridomas. It can easily be fused with ouabain-sensitive Epstein–Barr virus-transformed cells as well as with fresh tonsil and blood lymphocytes, giving rise to stable hybrids that continuously secrete very large quantities of human immunoglobulins. The derived hybrids do not lose immunoglobulin secretion over many months of continuous growth. The availability of this cell line should enable the in vitro immortalization of human antibody-producing B cells that are formed in vivo. The monoclonal antibodies produced may have advantages in immunotherapy.

The technique for the production of monoclonal antibodies was a culmination of a range of experimental studies with murine myeloma cell lines (1, 2). However, the mouse myelomas were not suitable for deriving human monoclonal antibodies because the heterospecific hybrids quickly lost the relevant human chromosomes. Likewise, the mouse–human heteromyelomas that have been used for fusion with human lymphocytes are often unstable (3) and secrete low levels of Ig, as do NSO mouse myeloma cells that have been transfected with human Ig genes (4).

Human myeloma cell lines have been very difficult to derive. Early on only the U266 human myeloma cell line was available, and the RPMI-8226 cell line contained a heterogeneous mixture of lymphoblastoid and plasmablast cells (5). Attempts in numerous laboratories to use those cells for the production of human monoclonal antibodies have failed despite early reports. As an alternative, the Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) has been used to immortalize antibody-producing human peripheral blood B lymphocytes. However, such cell lines tend to be unstable with respect to growth; they are low producers of antibodies, and the EBV does not preferentially immortalize lymphoblasts engaged in antibody responses (6). Over the past 20 years we have developed several human myeloma cell lines from six different patients with myeloma, and one of them has been adapted to be used as a partner for the derivation of human–human hybridomas.

Materials and Methods

Development of Cell Lines.

Karpas 707 cells.

This cell line was established from a patient with multiple myeloma (7, 8); it secretes only λ light chain. Its doubling time was over 70 h, but after continuous in vitro culture the doubling time was reduced to approximately 35 h. To obtain a hypoxanthine–aminopterin–thymidine (HAT)-sensitive subline the cells were grown in increasing concentrations of 8-azaguanine. Once the cells grew in 30 μg/ml of 8-azaguanine they were cultured in the presence of 30 μg/ml of 2-amino-6-marcaptopurine (6-thioguanine). The fastest growing clone that was sensitive to HAT was then cultured with an increasing concentration of ouabain (up to 0.03 μg/ml).

164 cells.

To optimize the conditions for hybridoma formation we decided to develop for the initial fusions an antibody-producing EBV-transformed line producing known antibody. We infected with EBV the white blood cells (WBC) from a healthy HIV-1-infected individual with the use of a standard method (6). From the EBV-immortalized B cells, we selected and cloned cells that produced IgG monoclonal antibodies to the HIV-1 gp41 (line 164).

Derivation of Karpas 707H cells.

Attempts to fuse the HAT-sensitive 707 with the 164 cells with the use of polyethylene glycol (PEG) of different molecular weights failed. Examination of viability of the PEG-treated cells revealed that the PEG was highly toxic, killing over 99% of the cells. We therefore decided to try and develop a PEG-resistant subline. The development of this cell line was achieved by treating about 107 myeloma cells with PEG (molecular weight 1,500), with the protocol used for murine hybridoma formation (9). The few viable cells that eventually grew out were treated again with PEG. We repeated such cycles of treatment more than 20 times over a period of about 18 months before a subline of the myeloma emerged where only about one-quarter of the cells were killed by the PEG treatment. However, in the process, HAT-resistant cells reappeared. The cells were therefore treated once more with 8-azaguanine and cloned. A clone was isolated that did not revert when grown in HAT medium.

Derivation of Human–Human Hybridomas.

The first fusion was between approximately 2 × 106 of the PEG-resistant myeloma cells and 5 × 106 164 cells, with the standard PEG fusion protocol (9). The cell suspension was seeded in 96-well and 24-well plates and cultured in the presence of HAT and ouabain (0.3 μg/ml). Tissue culture fluid collected from wells with active cell growth was assayed in the AIDS cell test for anti-viral antibodies (10).

Thereafter we used unfractionated WBC from 20 ml of peripheral blood of adults and tonsil cells from two children. In each of the cell mixtures we used approximately 5 × 106 myeloma cells and 107 WBC. The cell suspensions obtained after the PEG fusion were seeded in two 96-well tissue culture plates and grown in RPMI medium 1640 supplemented with 20% FBS and HAT for the first 12 days. Thereafter, the growth medium was supplemented with hypoxanthine and thymidine for 1 week. Tissue culture fluid collected from wells with active cell growth was assayed by ELISA for the presence of IgG, with the use of an ELISA test with protein A on the plastic wells to capture the IgG monoclonal antibodies produced by the newly formed hybridomas. The tissue culture fluids of 20 hybridomas that produce Ig have been screened with commercial ELISA tests (DiaSorin, Saluggia, Italy) for antibodies against EBV, cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex virus, varicella zoster virus, and mumps and measles viruses.

Karyotype Analysis and Electron Microscopy.

Chromosome analysis by the G-banding method was as described by Czepulkowski et al. (11). For the ultrastructural examination the cells were fixed in 3% glutaraldehyde, and ultrathin sections were stained in uranyl acetate and lead citrate (12).

Results

Human–Human Hybridoma Formation.

The first successful hybridoma was with the 164 cell. To monitor for antibody production we have been using the AIDS cell test (10).

Further studies of the IgG produced by the 707H/164 hybridoma, with the use of several polypeptides of the gp41, enabled us to establish that the monoclonal antibody reacted against the peptide LAVERYLKDQQLLGIWG, but it failed to react against four other peptides of the gp41 of HIV-1 (results not shown). The epitope that this monoclonal antibody recognizes seems not to be present in the African NDK strain of HIV-1 (13), inasmuch as the antibody failed to react with NDK-infected T cells but reacted not only with the Cambridge isolate of HIV-1 (14) but also with the early French LAV isolate (15). A database search (July 2000) confirms that the French (LAV) and British (CAM1) isolates of HIV-1 share the above amino acid sequence, whereas the African isolate has a lysine-to-arginine mutation.

After fusion of the myeloma with fresh lymphocytes, colony formation was observed during the 2–3 weeks after the removal of hypoxanthine and thymidine in approximately 28% of the wells when the myeloma cells were fused with tonsil cells and in about 18% the wells when the myeloma cells were fused with WBC (Table 1).

Table 1.

Frequency of hybridoma creations

| Cells | Independent fusions | Growth in wells | IgG+ wells* | Anti-EBV | Anti-HIV-1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WBC | 4 | 137/768 | 71/137 | 3/7 | 0/7 |

| Tonsils | 3 | 164/576 | 132/164 | 5/13 | 0/13 |

| 164 line | 2 | 25/120 | 5/25† | ND | 5/25 |

ND, not done.

Other clones were not systematically investigated.

The values may reflect the instability of the 164 parental cells, giving rise to variants that no longer produce the IgG.

The growth pattern of the clones was variable. The parent myeloma cells grew in a uniform pattern of adherent cells, forming an irregular mosaic that covered the plastic surface, with continuous release of cells into the culture fluid. The growth of some hybrids resembled the parent myeloma cells, but many others became more refractile and acquired a distinct morphology and growth forms. Some hybridomas adhered to the plastic surfaces and displayed numerous thick but short spindles and rectangular and triangular shapes. Others grew mainly in suspension as single cells or clusters.

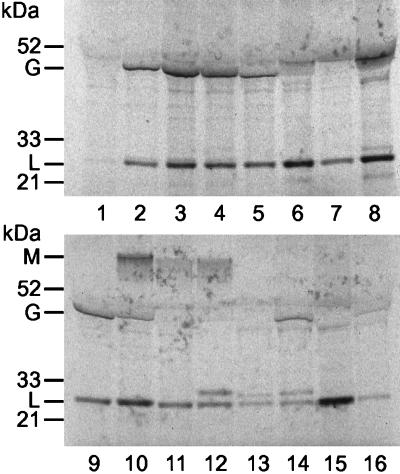

Tests for the secretion of Ig confirm that the parental cells produced a small quantity of light chain. As can be seen in Fig. 1, the fusions with the tonsil cells and blood lymphocytes produced clones that secreted IgG as well as IgM. We have now developed a large number of independent Ig-secreting hybrids by fusion with peripheral blood and tonsils lymphocytes. Most of the 40 hybridomas maintained continuously in culture have been secreting Ig during the past 5 months.

Figure 1.

Analysis of Ig secreted by the Karpas 707H cell line and hybridomas. The cells were grown at a concentration of 2 × 106 cells per milliliter in l-methionine, l-cysteine-deficient medium that was supplemented with 10% dialyzed FBS and with [35S]methionine and [35S]cysteine at 250 μCi/ml (Amersham Pharmacia). The cells were incubated for 8 h at 37°C in a CO2 incubator. After incubation, the cell suspensions were centrifuged at 1,000 × g for 5 min. The supernatant was analyzed by SDS-PAGE after total reduction with 10% Bis-Tris Gel with Mops running buffer (Invitrogen NuPage Electrophoresis system). Tracks: 1, small quantity of light chain produced by the Karpas 707H cells; 2, IgG that reacts with the gp41 HIV-1 produced by the hybrid with the EBV-infected 164 cells; 3 and 4, IgG-producing hybridoma formed with fresh WBC; 5–9 and 13–16, hybridoma formed with tonsil cells. Track 10 may contain both IgG and IgM, probably because of a mixture of two hybridomas that were formed in the same well. Tracks 11 and 12, IgM-secreting hybridomas; tracks 12–14, hybridomas that secrete two distinct light chains. This figure illustrates that in such hybridomas the secretion of the myeloma λ light chain is greatly amplified compared with the nonfused myeloma (track 1). What appears to be a single line of light chains in most hybridomas is probably due to myeloma and donor chains banding in the same position.

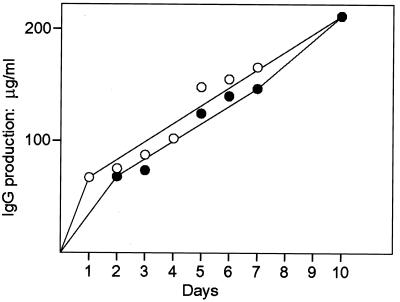

For the quantitation of IgG production the nephelometric assay kit (Dade Behring, Marburg, Germany) was used. A comparative assay for the secretion of antibodies to the gp41 of HIV-1 by the 164 cells and the hybrid (707H/164) revealed that the hybridoma produced far more antibody than the lymphoblasts after culture of an identical number of cells (106 per ml) for 4 days under the same conditions. The hybrid 707H/164 secreted 470 μg/ml of IgG, whereas the 164 cells secreted less than the assay detection level, 70 μg/ml. Thus the derived hybridomas are far more effective in antibody production. Hybridomas derived with the 164 cells and with WBC and kept over 10 days in culture without medium change revealed a gradual increase in IgG in the tissue culture fluid that continued despite the fact that the cells stopped dividing after 4 days and thereafter gradually died off (Fig. 2). This increase in IgG is similar to that in murine hybridomas that secreted IgG even after the cultures became stationary (9). The yield of IgG produced by the hybridoma secreting antibodies against the gp41 of HIV-1 and the hybridomas formed after fusion with blood lymphocytes indicate that the hybridomas that are formed secrete at least as much or even more antibody than the murine hybridomas. It correlates with the extensive rough endoplasmic reticulum (RER) in the human hybridomas (see below) as compared with the less developed RER of the murine hybrids.

Figure 2.

Quantitation of IgG secretion by two hybridomas: 707H/164 (○) and 707H/100 (●). Each hybridoma was seeded at a concentration of 3 × 105 cells per milliliter in RPMI 1640 growth medium supplemented with 10% FBS. Samples were collected at the indicated intervals for IgG quantitation by the nephelometric assay and for cell counts. After 4 days the viable cell count of the 707H/164 hybridoma reached 8 × 105 cells per milliliter, whereas that of a 707H/100 reached 6 × 105 cells per milliliter. Thereafter the number of viable cells decreased, and by the 10th day nearly all of the cells were dead when the level of IgG in the medium was at its highest, namely 210 μg/ml of IgG for both cultures.

By now, we have maintained in culture over the past 10 months the hybridoma cells from the well that had only one colony that had been giving a strong positive signal for the anti-HIV-1 antibodies. To test for the stability of antibody production we measured the titer of the anti-HIV-1 antibodies after 1, 5, and 9 months in culture. Using the AIDS cell test, we were able to show that the titer remained stable at 1:40. Furthermore, we also cloned the hybrids after 4 months in culture, plating 100 cells in a 96-well plate. In 27 wells colonies grew out and when tested 2 months later all produced the anti-HIV antibodies.

Tissue culture fluids from 5 of the 13 hybridomas formed with tonsil cells and 3 of the 7 formed with WBC contained antibodies against the viral capsid antigen of EBV (Table 2). Two of these hybridomas that were kept in culture for 3 months kept producing the anti-EBV antibodies.

Table 2.

ELISA for anti-EBV viral capsid antigen (VCA) hybridomas

| Hybridoma no. | ELISA titer, AU/ml |

| Tonsils | |

| 25 | 39 |

| 48 | 30 |

| 75 | 29 |

| 76 | 21 |

| 93 | 45 |

| WBC | |

| 110 | 29 |

| 105 | 25 |

| 200 | 23 |

| 100 | 0 |

The numbers represent arbitrary units (AU) per milliliter. Reactions for anti-VCA antibodies are considered positive when they are greater than 20 AU/ml (DiaSorin ELISA kit booklet). Thirteen hybridomas tested negative.

Karoytype Analysis.

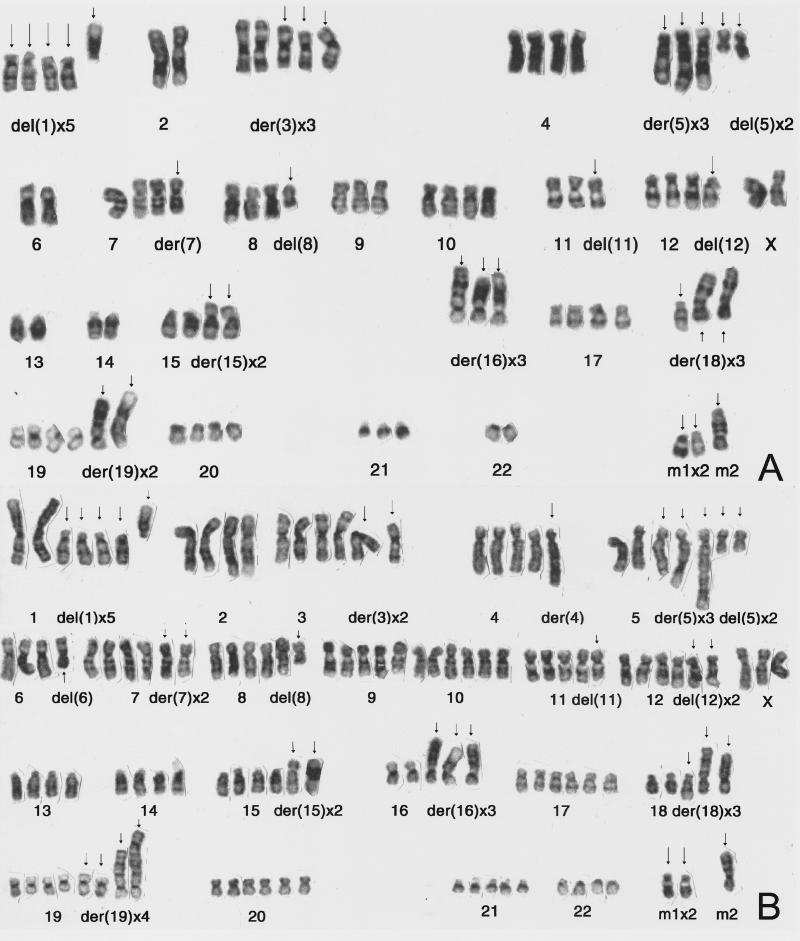

Initially the cultured cells, like the fresh patient cells, were found to be hypodiploid, with 45 chromosomes containing several chromosomal abnormalities (7). However, Karpas 707H is near-tetraploid, containing numerous and an unusually high number of gross chromosomal abnormalities (Fig. 3A). Karyotype analysis of the hybridoma 707H/164 revealed that the cells are near-hexaploid, containing the normal chromosomes from the lymphoblasts, which in the case of chromosomes no. 1 are in sharp contrast to the five abnormal chromosomes no. 1 of the myeloma (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

(A) A karyotype of the chromosomes of the Karpas 707H cell line, which are near-tetraploid. Note that chromosomes 2, 14, and 22, which contain the Ig genes, are normal and diploid. 83,XX,-X,-X,del(1)(p11p36)x4,+del(1)(q11q44),-2,-2,der(3)del(3)(p21p25)inv(3) (q23q25),+del(3)(q13q21),der(5)t(1;5)(p11;q31),der(5)t(2;5)(q21;q31), del(5)(q13q33)x2,+add(5)(q31),-6,-6,add(7)(p25),del(8)(q22q24),-9, del(11)(q23q25),-11,del(12)(p12p13),-13,-13,-14,-14,add(15)(p11)x2, der(16)t(1;16)(p11;p11),add(16)(p11)x2,-16,der(18)t(1;18)(q23;p11),add(18)(p11),add(18)(q23),-18,add(19)(q13)x2,+der(19)t(1;19)(q11;p13) +der(19)t(dup(1)(q23q44);19)(q11;p13),-21,-22,-22,+mar1 × 2,+mar2. (B) A karyotype of the hybridoma Karpas 707H/164, which is near-hexaploid, containing the normal pairs of chromosomes that are readily obvious in the case of chromosomes no. 1. 125,XXX,-X,-X,-X,del(1)(p11p36)x4,+del(1)(q11q44),-2,-2,add(3)(p25),der(3)del(3)(p21p25)inv(3)(q23q25),add(4)(q31),-4,der(5)t(1;5)(p11;q31), der(5)t(2;5)(q21;q31),del(5)(q13q33)x2,+add(5)(q31),del(6)(q21q23) -6, -6,add(7)(p25)x2,del(8)(q22q24),-9,del(11)(q23q25),-11, del(12)(p12p13)x2,-13,-13,-14,-14,add(15)(p11)x2,der(16)t(1;16)(p11;p11), add(16)(p11)x2, -16,der(18)t(1;18)(q23;p11),add(18)(p11),add(18)(q23), -18,add(19)(q13)x2,+der(19)t(1;19)(q11;p13),+der(19)t(dup(1)(q23q44);19)(q11;p13), -21,-21,-22, -22,+mar1 × 2,+mar2.

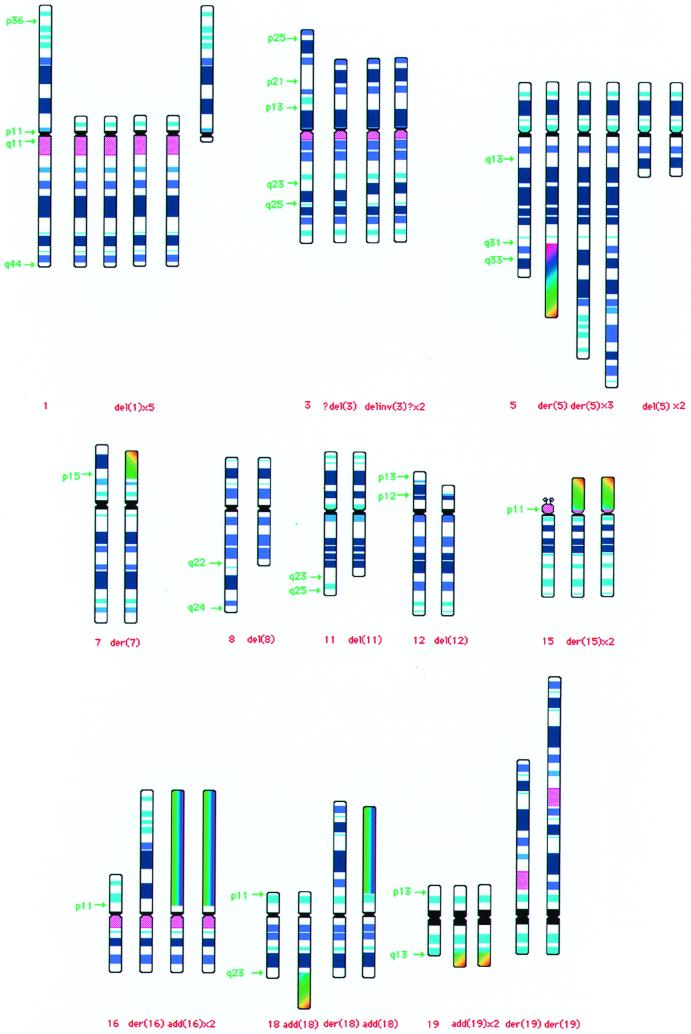

It is notable that in the 707H parental myeloma many of the chromosomes were abnormal (Fig. 4). To establish whether the repeated cycles of PEG treatment induced these karyotype abnormalities, the chromosomes of cells that were frozen before the PEG treatment were also analyzed. The analysis revealed that all of these changes were present before the PEG treatment. Hence it appears that during the continuous in vitro culture over many months and treatment with 8-azaguanine, 6-thioguanine, HAT, and ouabain, a near-tetraploid cell line emerged that had a growth advantage over the hypodiploid myeloma cells. It is interesting to note that the chromosomes 2, 14, and 22 that contain the Ig genes are normal and diploid (Fig. 3A).

Figure 4.

Diagram of the abnormal chromosomes found in the Karpas 707H myeloma and hybridoma. For comparison a normal chromosome is also illustrated with the corresponding abnormal chromosomes.

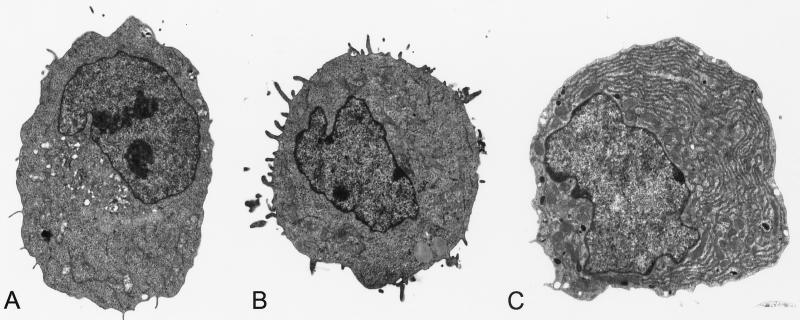

Electron Microscopy.

Ultrastructural examination of the cultured myeloma revealed that in contrast to the cells that contained large amounts RER during the first year in culture (7), after the long-term in vitro growth hardly any RER could be seen (Fig. 5A). Not surprisingly, the cytoplasm of the 164 cells contained only a few strands of RER (Fig. 5B). In contrast, examination of two hybridomas, 707H/164 (Fig. 5C) and 707H/105 (not shown), revealed that in both cases the hybrids resembled plasma cells. A large part of the cytoplasm was taken up by parallel and concentric RER. A large number of mitochondria could be seen in most sections, whereas sections through the Golgi area revealed a highly developed apparatus. Inasmuch as the ultrastructural examination of the EBV-immortalized 164 B cells revealed only a small number of short and thin strands of RER, it would not be unreasonable to suggest that the fused lymphoblast somehow activates the latent 707H myeloma RER for the increased production of Ig.

Figure 5.

Electron micrographs of the myeloma (A), 164 lymphoblast (B), and hybridoma that produces monoclonal antibodies against HIV (C). (×4,500.) The hybridoma shows extensive RER. The amount of RER in the cytoplasm of hybridoma derived with WBC was very similar to that shown in C.

Discussion

Because of past failures to develop human hybridomas, potentially useful mouse monoclonal antibodies have been modified by linking rodent variable regions and human constant regions (chimeric antibodies) or grafting the complementarity-determining region gene segments from mouse antibodies into human genes (humanized antibodies) (16). These modifications reduce the immunogenicity of the antibody, but residual immunogenicity is retained by virtue of the foreign V-region framework or the foreign complementary determining regions. Later, phage display technology was developed for the in vitro generation of human monoclonal antibodies (17). In addition, a transgenic mouse strain that contains human instead of mouse Ig genes was developed (18). This mouse strain contains human genes and produces human antibodies. The advantage of the murine–murine hybridoma procedure, possibly shared by the human–human procedure described here, over the non-hybridoma-based procedures is that it can preferentially immortalize antigen-activated B cells. However, the diversity created in a mouse strain is selected not in a human but in the mouse host, and the antibodies undergo affinity maturation in the mouse as opposed to a human environment. In addition, none of the available methods are suitable for dissecting out the human immune response to specific antigen challenges. Immortalization of B cells by EBV has been tried for this purpose. However, not only are the derived cells unstable, they also secrete very small quantities of antibodies, and their use has become rather unpopular. Therefore direct analysis of genes from heavy and light chains after PCR amplification has become the method of choice for characterizing the type of antibodies expressed by people in certain conditions.

Hence it is not unreasonable to claim that there is still an important role for a human myeloma cell line adapted to fuse with antibody-producing human lymphoblasts. The fact that we get a relatively high rate of hybridoma formation, even with a modest number of WBC, is rather encouraging. The procedure we describe should make it the one of choice for immortalizing human antibodies in pathological conditions including autoimmune diseases, infections, and other conditions, but not against some self antigens. Fusions of the myeloma with tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes may produce useful natural anti-cancer antibodies that might also uncover tumor-specific antigens. Such antigens could in turn be used as anticancer vaccines. The anti-tumor antibodies could have therapeutic advantages over antibodies produced by other methods.

We also note the stability of Ig production as well as the high yield of secreted antibodies as compared with that produced by other antibody-producing cell lines from other species. As can be seen in Fig. 2, human hybridomas can produce 210 μg of IgG per ml at a concentration of 6 × 105 cells per milliliter, that is, approximately 0.0035 μg per hybridoma cell. In contrast, hybrids derived with NSO mouse myeloma cells produce, under normal conditions, 10–20 μg/ml of IgG (9), whereas after transfection with human Ig genes, 2–24 μg/ml was secreted (4). In addition, the posttranslational modifications are likely to be identical to those made in human antibodies. Thus, in addition to hybridoma production, our human myeloma line may become a better cell for producing antibodies also derived by transfection of known antibody genes, provided we derive a λ-chain nonproducing variant.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. C. Milstein for critical reading of the manuscript and help in formulating the advantages of the human–human hybridoma. We also thank Mr. K. Burling for the quantitation of IgG, Mr. G. Gatward for help with the electron microscopy, and Dr. J Gray for the antiviral screening.

Abbreviations

- EBV

Epstein–Barr virus

- HAT

hypoxanthine–aminopterin–thymidine

- PEG

polyethylene glycol

- RER

rough endoplasmic reticulum

References

- 1.Cotton R G H, Milstein C. Nature (London) 1973;244:42–43. doi: 10.1038/244042a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Köhler G, Milstein C. Nature (London) 1975;256:495–497. doi: 10.1038/256495a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gustafsson B, Hinkula J. Hum Antibod Hybridomas. 1994;5:98–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lloyd-Evans P, Gilmour J E M. Hybridoma. 2000;19:143–149. doi: 10.1089/02724570050031185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nilsson K. Int J Cancer. 1971;7:380–396. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910070303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roder J C, Cole S P C, Kozbor D. Methods Enzymol. 1989;121:140–167. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(86)21014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karpas A, Fischer P, Swirsky D. Science. 1982;216:997–999. doi: 10.1126/science.7079750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karpas A, Fischer P, Swirsky D. Lancet. 1982;i:931–933. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(82)91933-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Galfre G, Milstein C. Methods Enzymol. 1981;73:3–46. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(81)73054-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karpas A, Gilson W, Bevan P C, Oates J K. Lancet. 1985;ii:695–697. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(85)92934-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Czepulkowski B H, Bhatt B, Rooney D E. In: Human Cytogenetics: A Practical Approach. Rooney D E, Czepulkowski B, editors. Vol. 2. Oxford: IRL; 1992. pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cawley J C, Hayhoe F G J. Ultrastructure of Hemic Cells. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ellrodt A, Le Bras Ph, Palazzo L, Brun-Vezinet F, Second P, Montagnier L, Barre-Sinoussi F, Nuqeyre M T, Rey F, Rouzioux C, et al. Lancet. 1984;i:1383–1385. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)91877-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karpas A. Mol Biol Med. 1983;1:457–459. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barré-Sinoussi F, Chermann J C, Rey F, Nugeyre M T, Chamaret S, Gruest J, Dauguet C, Axler-Blin C, Vezinet-Brun F, Rouzioux C, et al. Science. 1983;220:868–871. doi: 10.1126/science.6189183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Winter G, Milstein C. Nature (London) 1991;349:293–299. doi: 10.1038/349293a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Winter G, Griffiths A D, Hawkins R E, Hoogenboom H R. Annu Rev Immunol. 1994;12:433–455. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.002245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bruggemann M, Neuberger M S. Immunol Today. 1996;17:391–397. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(96)10025-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]