Abstract

Hox proteins are well known for executing highly specific functions in vivo, but our understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying gene regulation by these fascinating proteins has lagged behind. The premise of this review is that an understanding of gene regulation — by any transcription factor—requires the dissection of the cis-regulatory elements that they act upon. With this goal in mind, we review the concepts and ideas regarding gene regulation by Hox proteins and apply them to a curated list of directly regulated Hox cis-regulatory elements that have been validated in the literature. Our analysis of the Hox-binding sites within these elements suggests several emerging generalizations. We distinguish between Hox cofactors, proteins that bind DNA cooperatively with Hox proteins and thereby help with DNA-binding site selection, and Hox collaborators, proteins that bind in parallel to Hox-targeted cis-regulatory elements and dictate the sign and strength of gene regulation. Finally, we summarize insights that come from examining five X-ray crystal structures of Hox-cofactor-DNA complexes. Together, these analyses reveal an enormous amount of flexibility into how Hox proteins function to regulate gene expression, perhaps providing an explanation for why these factors have been central players in the evolution of morphological diversity in the animal kingdom.

1. An Introduction to the Problem

Hox proteins are homeodomain-containing transcription factors that have the capacity to carry out exquisitely precise functions in vivo that are critical for many aspects of animal morphogenesis. Most typically, each Hox gene is expressed in a subset of the anterior-posterior (AP) body axis, where it specifies cellular and tissue identities. Famous examples of the power that Hox genes have to sculpt animal morphogenesis include the antenna-to-leg transformation caused by the Antennapedia (Antp) mutation in Drosophila and several polydactyly syndromes in humans (Goodman, 2002; Lewis, 1978; Randazzo et al., 1991). These types of phenotypes have been a long-standing source of fascination for both biologists and lovers of science fiction.

An important and long-debated question for Hox biologists has been how these proteins achieve this apparently high degree of in vivo specificity. In this review, we summarize ideas and recent data bearing on the question of Hox specificity, with a special emphasis on what can be learned by analyzing native cis-regulatory elements that are directly bound and regulated by Hox proteins. Excellent reviews discussing the range of Hox target genes that have been identified using genome-wide and traditional approaches complement the emphasis of this chapter (Hueber and Lohmann, 2008; Pearson et al., 2005).

When Hox genes were first cloned and shown to encode homeodomain-containing proteins (Akam, 1989; Regulski et al., 1985), researchers initially speculated that Hox proteins would bind and regulate the correct subset of target genes according to the DNA recognition properties of their homeodomains. However, early work from a number of labs quickly established that homeodomains were not likely to be up to the task of dictating Hox-DNA-binding specificities on their own (Affolter et al., 1990; Desplan et al., 1988; Ekker et al., 1991, 1994; Hoey and Levine, 1988). Indeed, homeodomains, particularly the subset present in the Hox protein family, all bind to a very similar set of “AT”-rich DNA-binding sites, raising the fundamental question of how specificity is achieved. In addition to this classical problem of degenerate binding site recognition, experiments using chimeric Hox proteins—where bits of one Hox protein were replaced with homologous bits of another—highlight an additional complication. As expected, specific Hox functions required the homeodo-main. In some cases, however, specificity also required nonhomeodomain residues, in particular, those that lie immediately N- or C-terminal to the homeodomain (Chan et al., 1994; Dessain et al., 1992; Furukubo-Tokunaga et al., 1993; Gibson et al., 1990; Kuziora and McGinnis, 1989, 1990; Lin and McGinnis, 1992; Mann and Hogness, 1990; Zhao and Potter, 2001, 2002). How these nonhomeodomain residues may impact Hox specificity is just now coming into focus.

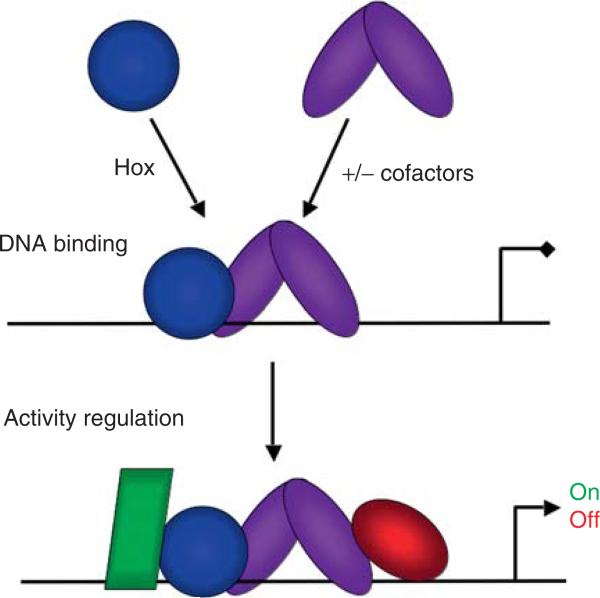

Because they are DNA-binding transcription factors, it is probably a safe bet that Hox proteins carry out the majority of their functions by binding to cis-regulatory elements (although alternative mechanisms have been proposed; Plaza et al., 2008). Because eukaryotic transcription is governed by cis-regulatory elements that typically integrate multiple inputs, each Hox-targeted element is likely to have binding sites for many transcription factors. Therefore, to understand how Hox proteins ultimately function to control target gene expression, it is necessary to consider two broad questions. First, how do Hox proteins recognize their DNA-binding sites and second, how do they interact with other transcriptional inputs that feed into the same cis-regulatory element? We suggest that it is helpful to break the problem of Hox specificity down into two conceptually separable steps (Fig. 3.1). In the first step, the question can be rephrased to ask: How do Hox proteins find the right DNA-binding sites in vivo? Many examples exist in the literature suggesting that Hox proteins solve this initial “DNA-binding specificity” step in multiple ways. As will be explored more fully below, one solution is by the use of cooperatively binding cofactors such as Extradenticle (Exd), Pbx, Homothorax (Hth), and Meis that increase Hox-DNA-binding specificities (previously reviewed by Mann and Affolter, 1998; Mann and Chan, 1996; Moens and Selleri, 2006). However, it is also increasingly clear that Hox proteins regulate many genes without the help of these cofactors. In the second step, the question is: Once bound, how do Hox proteins orchestrate a transcriptional response? As the same Hox protein can activate some target genes, and repress others, it is clear that this “activity regulation” step is also critical for how Hox proteins execute their in vivo functions. In fact, as will be described more fully below, there is now good evidence for both of the steps outlined in Fig. 3.1 playing critical roles in Hox specificity.

Figure 3.1.

Two contributing steps in Hox specificity. In principle, Hox specificity can be broken down into two separate steps. The first step is DNA binding by Hox proteins, which can occur either with or without cooperatively binding cofactors. The second step involves the recruitment of additional factors, Hox collaborators, to the cis-regulatory element. The recruitment of these factors may depend on contacts between them and the DNA and/or protein-protein contacts between them and the Hox-cofactor complex. It is the recruitment of these collaborators, which we suggest depends on the architecture of the entire cis-regulatory element (including the details of the Hox-binding site) that ultimately determines the sign of the transcriptional regulation.

2. Too Many Binding Sites, Not Enough Specificity

Because all Hox proteins have a homeodomain, understanding how Hox proteins recognize their DNA-binding sites in vivo certainly depends, at least in part, on how this 60 amino acid domain recognizes DNA sequences. The basic DNA recognition principles for homeodomains were established from biochemical and structural studies (reviewed previously by Gehring et al., 1994). These studies show that all homeodomains fold into a bundle of three alpha-helices and an unstructured “N-terminal” arm. DNA contacts are formed primarily by residues 47, 50, 51, and 54 in the third alpha-helix (the so-called recognition helix) and by an arginine in position 5 of the N-terminal arm. While these studies provided a high resolution view of how homeodomains generally bind to DNA, they did not provide much insight into the problem of Hox specificity for three reasons. First, nearly all Hox homeodomains, even those with very disparate in vivo functions, have the same residues in the DNA-contacting residues visualized in these structures (Mann, 1995). Second, although nonhomeo-domain residues were known to play a role in Hox specificity from studies of chimeric Hox proteins (see above), these domains were not present in any of the initial structural studies. Third, the DNA sequences used in these early structural studies were not in vivo binding sites. Instead, these structures used high-affinity consensus sites that would not be expected to reveal insights into homeodomain specificity.

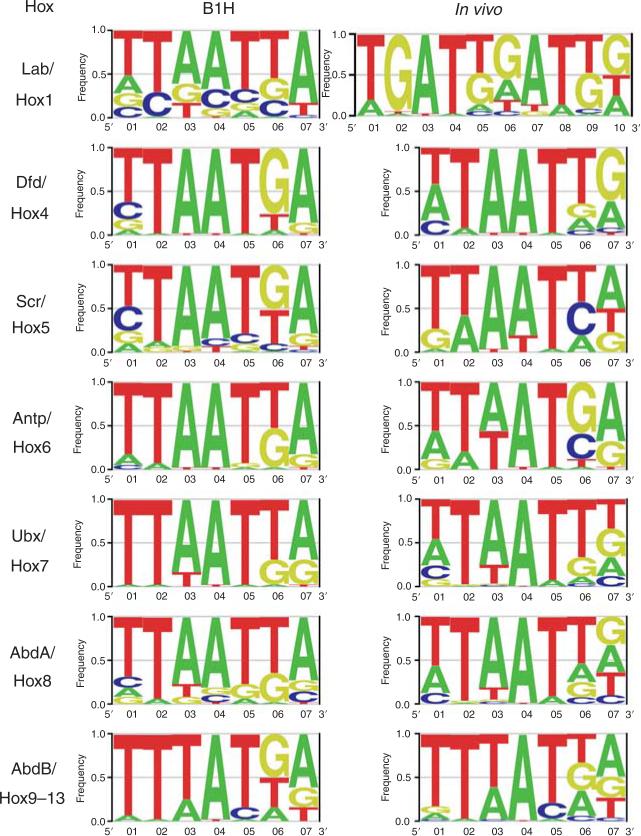

Another limitation in the early studies on homeodomain-DNA recognition was that only a small subset of homeodomain proteins were studied. Thanks to the advent of new, powerful methodologies, two large-scale studies have recently defined the individual DNA-binding specificities for nearly all homeodomains, including the subset present in the Hox proteins. One group used a bacterial one-hybrid approach (B1H) to analyze the DNA-binding preferences for all of the homeodomains encoded in the Drosophila melanogaster genome (Noyes et al., 2008) while the second group used an entirely in vitro platform, protein-binding microarrays (PBMs), to answer the same question for all mouse homeodomains (Berger et al., 2008). Although there are pros and cons for each approach (Affolter et al., 2008), these studies confirmed that Hox homeodomains like to bind “AT”-rich DNA sequences (Fig. 3.2). In particular, the so-called “Antennapedia (Antp) Group” of homeodomains, which includes all Hox homeodomains except for those of the Abdominal-B (Abd-B) class, like to bind the sequence TAAT[t/g][a/g]. There are 87,307 copies of the sequence TAATTA and 86,201 copies of the sequence TAATGA in the D. melanogaster genome, each more than five times the number of annotated protein-coding genes. Clearly, the presence of TAAT[t/g][a/g] cannot be sufficient information for Hox regulation. Moreover, as elegantly illustrated by the homeodomain-binding site survey studies (Berger et al., 2008; Noyes et al., 2008), TAAT[t/g][a/g] is readily bound by most Hox homeodomains, as well as many non-Hox homeodomains. Therefore, this and related binding sites cannot be sufficient to distinguish between Hox family members that carry out distinct functions in vivo.

Figure 3.2.

Comparison of in vitro and in vivo Hox-binding site preferences. Shown are LOGO diagrams summarizing Hox-binding site preferences for most paralogs. The column on the left lists the LOGOs generated using the binding sites identified by the bacterial 1-hybrid (B1H) method (Noyes et al., 2008). The column on the right lists the LOGOs generated using the in vivo binding sites in Table 3.1. To generate these LOGOs, we used CONSENSUS (as part of Target Explorer; http://luna.bioc.columbia.edu/Target_Explorer/) to generate position weight matrices (PWMs). PWMs that maximized alignment of an “AT” sequence were converted to Transfac format using the phiSITE conversion server (http://www.phisite.org/main/index.php?nav=home). enoLOGOS (http://chianti.ucsd.edu/cgi-bin/enologos/enologos.cgi/) was then used to generate the LOGOs using nucleotide frequency for the Y-axis. The number of binding sites used to generate each LOGO was as follows: Labial: 31 (B1H), 17 (in vivo); Dfd: 24 (B1H), 17 (in vivo); Scr: 34 (B1H), 12 (in vivo); Antp: 19 (B1H), 16 (in vivo); Ubx: 20 (B1H), 57 (in vivo; the resulting LOGO was only subtly affected if the 30 sites from the Antp-P2 element were omitted); Abd-A: 23 (B1H), 39 (in vivo); and AbdB: 21 (B1H), 49 (in vivo).

3. How Specific Do Hox Proteins Need to be?

Hox biologists can readily point to highly specific functions that are uniquely specified by individual Hox proteins. For example, in Drosophila, only the Hox gene Sex combs reduced (Scr) can orchestrate the development of a salivary gland, presumably by regulating a network of salivary gland-promoting genes (Bradley et al., 2001). The flip view that multiple Hox proteins probably share many targets is typically given less attention. We believe this discussion is highly relevant to how one thinks about Hox specificity, because it may be that only a subset of Hox targets for any particular Hox protein need be highly specific.

One example of a morphological process that is controlled by multiple Hox genes is appendage development in Drosophila. Leg development is limited to the thoracic segments due to repression of Distalless (Dll) by the abdominal Hox genes, Ultrabithorax (Ubx), abdominal-A (abd-A), and Abdominal-B (Abd-B) (Estrada and Sánchez-Herrero, 2001; Vachon et al., 1992). Moreover, Ubx and abd-A work, at least in part, through common binding sites in a Dll cis-regulatory element (Gebelein et al., 2002, 2004). Thus, Dll is a shared target for the abdominal Hox genes. Similarly, the antenna-specifying gene homothorax (hth) can be repressed by all of the trunk Hox proteins, suggesting that hth is also a shared target (Casares and Mann, 1998, 2001; Yao et al., 1999). A third example is the Drosophila head-promoting gene, optix, which is repressed by the trunk Hox genes and activated by the more anterior (head) Hox genes (Coiffier et al., 2008). For hth and optix, a limitation in this conclusion is that the Hox-binding sites in these genes (assuming the regulation is direct) have not yet been identified. Therefore, although these genes are clearly shared Hox targets by genetic criteria, it is possible that different Hox proteins use different binding sites within these genes to regulate their expression. Nevertheless, these and other examples (Greig and Akam, 1995; Hirth et al., 2001) support the idea that not all Hox functions need to be paralog-specific. If true, it follows that many bona fide Hox-binding sites may not need to discriminate between different Hox proteins.

How many Hox targets are shared and how many are paralog-specific? Although the field may be getting closer to a definitive answer to this question, by applying ChIP-chip and/or ChIP-seq methodologies to Hox proteins, the currently available data provide an interesting estimate. Using overexpression of Hoxc8 in mouse embryo fibroblasts, the expression levels of 34 genes were found to change by twofold or more (Lei et al., 2005). This relatively small number of potential Hoxc8 targets contrasts from the much larger numbers of regulated genes identified in whole embryo expression profiling experiments following the uniform (and ectopic) expression of individual Hox proteins during Drosophila embryogenesis (Hueber et al., 2007). An important strength of these experiments is that the global transcriptional response to multiple Hox proteins was analyzed in parallel, using the same experimental conditions. Remarkably, of the ~1500 genes (about 10% of all Drosophila genes) whose expression changed significantly in response to ectopic Deformed (Dfd), Scr, Antp, Ubx, Abd-A, or Abd-B expression, more than two-thirds (~69%) were regulated by only one of these six Hox proteins. About one-third (~30%) of all Hox-responsive target genes responded to multiple Hox proteins, while only ~1% responded to all six of these Hox proteins. There are, however, a few caveats to these experiments. For one, they measured responses to ectopic Hox expression, which may not always reflect accurate gene regulation in their native expression domains. Second, these experiments did not distinguish between tissue-specific responses and third, they could not unambiguously discriminate between direct and indirect effects. Nevertheless, the results from this study are remarkable because they suggest that many, and perhaps the majority of Hox target genes are paralog-specific. However, the results also support the view that a significant number of genes are targeted by multiple Hox proteins, again raising the possibility that not all Hox-binding sites need to discriminate between Hox proteins.

Developmental context is another issue that should be considered when thinking about Hox specificity. In Drosophila, for example, each embryonic segment is built using the same reiterated set of signaling pathways that provide them with a common coordinate system, known as positional information. Once this “ground plan” is established, the non-Hox regulatory inputs into a gene are largely the same from segment to segment. One way to think about the Hox genes is that they impose identity information on top of this developmental ground plan, thus providing each segment its unique characteristics. Because the other regulatory inputs are largely equivalent, a gene that is specifically expressed (or repressed) in a small subset of embryonic segments is likely to be a paralog-specific Hox target gene. For example, for salivary glands to form only in the first thoracic (T1) segment, the Hox gene Scr must activate the salivary gland program, including its directly activated target gene forkhead (fkh), in a paralog-specific manner; other Hox proteins cannot activate this target in other segments (Bradley et al., 2001). Similarly, while Dll is repressed by abdominal Hox proteins, the thoracic Hox proteins Scr and Antp must be permissive for Dll expression (Gebelein et al., 2002). Repression by the abdominal Hox proteins therefore must have specificity. However, the same is not true for tissues where the ground plan, and thus the other regulatory inputs, is different. For example, the Hox gene Ubx is expressed in all cells of the developing haltere (a balancing organ used during flight) of the fly, where it regulates the expression of many genes (Crickmore and Mann, 2007, 2008; Lewis, 1978; Weatherbee and Carroll, 1999). Other than the developing wing, where Hox genes are not expressed for most of development, no other tissue in the fly has the same ground plan as the haltere. Therefore, the cis-regulatory elements used by Ubx to regulate genes in the haltere may not need to be highly selective for Ubx: other Hox proteins never have the opportunity to regulate these genes in the haltere/wing tissue simply because they are not expressed there. Confirmation of this idea comes from the finding that other Hox proteins, when expressed in the wing, can result in haltere-like phenotypes and mimic Ubx-like regulation (Casares et al., 1996; R. S. Mann and M. Crickmore, unpublished observations). Similarly, although both Ubx and Abd-A have the potential to induce gonad development, the job is normally carried out by Abd-A simply because it is the only Hox protein that is expressed in the correct set of mesodermal progenitor cells (Greig and Akam, 1995). Finally, another remarkable example of functional redundancy among different Hox paralogs is that all of the Drosophila Hox proteins, except for Abd-B, have the ability to replace Labial in the specification of the tritocerebral neuromere in the fly's brain (Hirth et al., 2001). Like Ubx in the haltere, the ground plan for this portion of the brain may be sufficiently unique so that it does not require exquisite Hox specificity, accounting for why nearly all Hox paralogs can, at least to some degree, carry out the same functions as Labial.

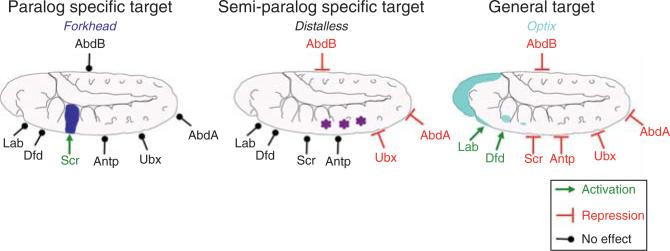

In summary, when thinking about what Hox-bindings sites may look like based on these considerations, we suggest that it is useful to distinguish between three types of Hox target genes (Fig. 3.3) (1) those that must be highly specific for one Hox paralog (“paralog-specific”; e.g., Scr → fkh), (2) those that are shared by a subset of Hox proteins (“semi-paralog-specific”; e.g., Ubx, Abd-A, and Abd-B ⊣ Dll), and (3) those that are regulated by most or all Hox genes (“general”; e.g., all of the trunk Hox genes ⊣ optix). In addition, we argue that for some Hox functions that have the appearance a of paralog specificity (e.g., Ubx dictating haltere instead of wing fates), the Hox-binding sites, themselves, do not need to be paralog-specific as long as the developmental context is sufficient to specify a unique regulatory environment.

Figure 3.3.

Three types of Hox target genes. “Paralog-specific” Hox target genes are those that are uniquely regulated by only a single Hox paralog, such as the activation of fkh by Scr. “Semi-paralog-specific” Hox target genes are those that are shared by a small subset of Hox paralogs, such as the repression of Dll by the abdominal Hox proteins Ubx, Abd-A, and Abd-B (schematized here is the Dll304 embryonic enhancer element). “General” Hox target genes are those that are regulated by most, or perhaps all, Hox paralogs, such as the control of optix in Drosophila. Ideally, this classification should apply to individual cis-regulatory elements, not entire genes, to allow for the scenario that the same gene may fall into more than one of these categories (in two different tissues or times of development). For fkh and Dll, specific cis-regulatory elements that fit the “paralog-specific” and “semi-paralog-specific” criteria have been identified. In contrast, a single cis-regulatory element that is a “general” Hox target has not yet been identified and therefore remains hypothetical.

4. Hox Cofactors

Given that some Hox functions truly require a high degree of specificity, and that Hox homeodomains, themselves, are not sufficiently discriminating to account for this specificity, how is specificity achieved? One well-established way in which Hox proteins achieve specificity in vivo is to bind DNA cooperatively with other DNA-binding cofactors. To date, the best-characterized cofactors are all TALE (three amino acid loop extension) homeodomain proteins (Mann and Chan, 1996; Moens and Selleri, 2006). In Drosophila, the known TALE Hox cofactors are Extradenticle (Exd) and Homothorax (Hth). In the mouse, there are four Exd-related proteins (Pbx1, Pbx2, Pbx3, Pbx4) and five Hth-related proteins (Meis1, Meis2, Meis3, Prep1, and Prep2). In Caenorhabditis elegans, there are three genes encoding Exd-like proteins (ceh-20, ceh-40, ceh-60) and two that encode Hth-like proteins, unc-62 and psa-2, which encodes for a truncated form that has no homeodomain (see Mukherjee and Bürglin, 2007 for a thorough description of the TALE family genes). Here, we collectively refer to Exd/Pbx/Ceh-20 as PBC proteins. These proteins all have the ability, at least on some DNA sequences, to bind with Hox proteins in a highly cooperative manner. In addition, it is important to stress that where it has been analyzed, TALE family homeodomain proteins also carry out many Hox-independent functions in vivo (Bessa et al., 2008; Casares and Mann, 1998, 2001; Jiang et al., 2008; Laurent et al., 2007; Moens and Selleri, 2006). Because they have both Hox-dependent and Hox-independent functions the genetic analysis of TALE family genes needs to be interpreted with caution, since only a subset of the observed phenotypes is due to their role as Hox cofactors.

Protein interaction domains characterized in Hox, PBC, and Hth/Meis/Prep proteins have provided many insights into how these three factors assemble when bound to DNA. PBC proteins interact with Hth/Meis/Prep family members in a DNA-independent manner via highly conserved domains present in the N-terminal regions (PBC-A of PBC and HM of Hth/Meis) of these proteins (Mann and Affolter, 1998). In several cases, the nuclear localization and/or stability of these proteins has been shown to depend on this protein-protein interaction (Arata et al., 2006; Berthelsen et al., 1999; Haller et al., 2004; Huang et al., 2003; Mann and Abu-Shaar, 1996; Ryoo and Mann, 1999; Saleh et al., 2000; Stevens and Mann, 2007). In contrast, PBC-Hox interactions appear to be more complicated—and potentially more interesting. The traditional view, which has been supported by biochemical, in vivo, and structural studies, is that a motif common to most Hox proteins—YPWM—makes direct contacts with the TALE motif in PBC homeodomains, which creates a hydrophobic pocket that binds the W in YPWM (Chan and Mann, 1996; Chang et al., 1995; Joshi et al., 2007; LaRonde-LeBlanc and Wolberger, 2003; Lu and Kamps, 1996; Neuteboom et al., 1995; Passner et al., 1999; Phelan et al., 1995; Piper et al., 1999). For those Hox proteins that do not have an obvious YPWM motif, in particular the Abd-B paralogs, there is a conserved W residue that, at least for a subset of Abd-B paralogs, plays an important role in this protein-protein interaction (Shen et al., 1997). However, more recent studies make it clear that there is more to PBC-Hox-DNA complex formation than the YPWM-TALE interaction. On the one hand, two studies have shown that mutation of the YPWM motif in Ubx fail to abolish cooperative binding with PBC proteins in vitro and some Ubx functions in vivo (Galant et al., 2002; Merabet et al., 2003; Shen et al., 1997). On the other hand, a peptide immediately following the Ubx homeodomain, termed the UbdA motif because of its similarity between Ubx and Abd-A, is playing an important, and perhaps dominant, role in the interaction between these Hox proteins and Exd on some binding sites (Merabet et al., 2007). Interestingly, consistent with the idea that the UbdA motif is playing a role in PBC-Ubx (and likely Abd-A) interactions, it contributes to Ubx functional specificity in vivo (Chan and Mann, 1993; Gebelein et al., 2002). Although the UbdA motif is not found outside of arthropods, these findings suggest the more general idea that PBC proteins may have modes of interaction with other Hox proteins that are in addition to the classical YPWM-TALE interaction. The existence of multiple PBC interaction domains in a single Hox protein such as Ubx suggest that the way in which PBC-Hox complexes assemble onto cis-regulatory elements may vary from target to target, potentially expanding their ability to recruit additional transcription factors.

In addition to TALE family homeodomain proteins, the Drosophila homeodomain protein Engrailed (En) has also been shown to be a Hox cofactor (Gebelein et al., 2004). In this case, En bound cooperatively with both Ubx and Abd-A to a regulatory element from the Dll gene, and En input is required for Dll repression in the posterior compartments of the abdominal segments (Gebelein and Mann, 2007; Gebelein et al., 2004). Unlike the TALE cofactors, which can function with Hox proteins to both activate and repress target genes, it is likely that En-Hox dimers are more typically involved in gene repression due to En's ability to directly bind the corepressor Groucho (Jiménez et al., 1997).

A subset of Zn finger-containing transcription factors, most prominently Drosophila Teashirt (Tsh), has also been suggested to be Hox cofactors (Robertson et al., 2004; Taghli-Lamallem et al., 2007). Although a very appealing idea, these factors do not seem to exhibit the same robust cooperativity that is typically observed between TALE factors and Hox proteins. And, at least in the one target where Tsh-binding sites were identified (modulo), they are not adjacent to the Hox-binding sites (Taghli-Lamallem et al., 2007). Thus, at this time we prefer to classify these Zn finger factors as Hox “collaborators,” which provide additional, essential inputs into a subset of Hox-targeted cis-regulatory elements (discussed in more detail below) (Table 3.1).

Table 3.1.

Direct Hox-DNA-binding sites

| Name (gene) | Hox | Reporter Validation | DNA Binding Site (Hox, PBC, Meis/Hth, Other) | Cooperative Cofactors | Other Factors | Target Origin: Notes | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EphA2-repeat E (EphA2/eck) | Hoxa1 Hoxb1 | Ex vivo | gcaTGATGGATGGgct | Pbx‡ | ND | Mouse | (Chen and Ruley, 1998) |

| b1-ARE (Hoxb1) | Hoxb1 Lab | In vivo | ctcAGATGGATGGgctgcgggTGATTGAAGTgTCTTTGTCATGCTAAT gcttggggggTGATGGATGGgcgctggggCTGCCAaac |

Pbx1, Prep1 | Sox2, Oct1 | Mouse: Autoregulatory element, R3 site (also known as Repeat3) functions as a Labial target in Drosophila | (Chan and Mann, 1996; Di Rocco et al., 2001; Ferretti et al., 2005; Pöpperl et al., 1995) |

| r4-Hoxa2 (Hoxa2) | Hoxb1 | In vivo | ggaTGATTTATTTgag; attTGACAGtaatgaagag TGATAGATTGctc; ggcTGATGCATTAatt |

Pbx1, Prep1 | ND | Chicken and Mouse | (Tümpel et al., 2007) |

| b2-PP2 (Hoxb2) | Hoxb1 | In vivo | gagCTGTCAgggggctaAGATTGATCGccc | Pbx1†, Prep1 | ND | Mouse | (Ferretti et al., 2000) |

| A3-PP2; A3-PhP1 (Hoxa3) | Hoxb1 | In vivo | ggtTGATTATTGacc; gagTCATAAATCTtgccc agccataaaTGACAAaaa |

Pbx1a†, Prep1 | ND | Mouse and Chicken; Mutation of Prep site did not affect reporter expression in vivo | (Manzanares et al., 2001) |

| P2b_0.38 (Phox2b) | Hoxb1 | In vivo | gcgTGATTGAATtaa; ttaTTGTCAtgt | Pbx1a†, Prep1 | ND | Mouse | (Samad et al., 2004) |

| FPB (COL5A2) | Hoxb1 | Ex vivo | gtcTGATTGATGGtaa | Pbx1a* | Prep1* | Human; Cotransfection of Prep1 increased expression ex vivo | (Penkov et al., 2000) |

| 125bpHb9 (Hb9) | Hoxb1, Hoxb3 | In vivo | agcTGATGAATTGacaaaaACTAATCA | Pbx1† | ND | Mouse | (Nakano et al., 2005) |

| EVIII (CG11339) | Lab | In vivo | tcgTGATCAATTAcagCTGACTggg | Exd, Hth | ND | Drosophila; Although the Exd half-site is required in vivo, cooperative binding of Lab/Exd dimers was not observed in vitro | (Ebner et al., 2005) |

| lab48/95 (lab) | Lab | In vivo | aatTGATGGATTGcccggcgccgaCTGTCAccg | Exd, Hth | ND | Drosophila; Autoregulatory element | (Ryoo et al., 1999) |

| enh450 (ceh-13) | CEH-13 | In vivo | aaaTGATGGATGGttc | CEH-20 | ND | C. elegans; Autoregulatory element | (Streit et al., 2002) |

| E2-A2RE (Hoxa2) | Hoxa2 | Ex vivo | cggTGATTGATGGaag | Pbx1† | ND | Mouse, Autoregulatory element | (Lampe et al., 2004) |

| HRE1.25 (Hoxa2) | Hoxa2 | In vivo | tctTGATTGATGAact | Pbx1a* | Prep1* | Mouse; Autoregulatory element, cotransfection of Prep1 increased expression ex vivo | (Lampe et al., 2008) |

| TTF-1-BS1&2 (TTF-1) | Hoxb3 | Ex vivo | cctTAATTGgct; agaTAATTAgct | ND | ND | Rat; Both sites are necessary for expression ex vivo | (Guazzi et al., 1994) |

| CR3-HS1&2 (Hoxb3, Hoxb4) | Hoxb4, Hoxd4, Hoxb5 | In vivo | agTGATTAATGGttttctgtaTAATTCtc | Exd† | ND | Mouse; Autoregulatory element; also responds to Dfd, Hoxb5, Scr, Antp. and Ubx in Drosophila | (Gould et al., 1997) |

| Rarb (Rarb) | Hoxb4, Hoxd4 | In vivo | gggTGATAAATAAtgg | Pbx# | ND | Mouse; Role of Pbx not tested | (Serpente et al., 2005) |

| Repeat 3-TA (synthetic) | Dfd | In vivo | gggTGATTAATGGgcg | Exd | ND | Synthetic; (GG->TA) mutation of Repeat3 of b1-ARE | (Chan et al., 1997) |

| DfdEAE-module E (Dfd) | Dfd | In vivo | cccTAATTGccacgCATTAGctc | ND | Exd‡ | Drosophila; Autoregulatory element, atypical Exd binding site, exd required in vivo | (Pinsonneault et al., 1997; Zeng et al., 1994) |

| rprDfd (rpr) | Dfd | In vivo | caaTAATTAccc; ctcTAATTGccc; aacTAATTGaca; tcaTAATTGagg |

Not Exd‡ | ND | Drosophila; Cooperative binding with Exd not observed | (Lohmann et al., 2002) |

| 1.28DRE (1.28) | Dfd | In vivo | gttTAATTGgtt; tctTAATAGccg; ccaCTACATTAATTATgaa; ccgCGATAATAAatc |

Not Exd‡ | ND | Drosophila; Sites not tested individually, cooperative binding with Exd not observed | (Pederson et al., 2000) |

| jkl-216-site1 (hlh-8) | LIN-39 | In vivo | agtTGAAaaATTACCgcg | CEH-20 | ND | C. elegans | (Liu and Fire, 2000) |

| egl-17 (egl-17) | LIN-39 | In vivo | ctcTGATTAATCActg | CEH-20 | ND | C. elegans | (Cui and Han, 2003) |

| egl-18/elt-6-site 1 (elg-18, elt-6) | LIN-39 | In vivo | gggTGATATATATgtt | CEH-20† | ND | C. elegans | (Koh et al., 2002) |

| Fkh250 (fkh) | Scr | In vivo | tcaAGATTAATCGcca | Exd, Hth | ND | Drosophila; Hth binding site not found | (Ryoo and Mann, 1999) |

| Lin-39-site2 (lin-39) | LIN-39 | In vivo | catTGATTTATTTttg | CEH-20† | ND | C. elegans; Autoregulatory element | (Wagmaister et al., 2006) |

| mod-84 (mod) | Scr | In vivo | acaTAATTTgttagtatgTAATATtccctg GTATTTTTCCAATGactgtcaagcagtgctg GTAAATGGCGGAACaag |

ND | Tsh | Drosophila; Although both Scr and Tsh regulate mod, a cooperative interaction was not observed | (Taghli-Lamallem et al., 2007; Taghli-Lamallem et al., 2008) |

| p53 (p53) | Hoxa5 | Ex vivo | tctTAATTCaaa | ND | ND | Human and Mouse | (Raman et al., 2000a) |

| PRP-62 (PR) | Hoxa5 | Ex vivo | cggTAATTGggg | ND | ND | Human | (Raman et al., 2000b) |

| PTN-106 (PTN) | Hoxa5 | Ex vivo | tttTAATAAgct | ND | ND | Human | (Chen et al., 2005) |

| HBE (flk1) | Hoxb5 | In vivo | tgcTGATTAATGAaaa | Pbx# | ND | Mouse; Mutation affecting reporter activity located in putative Pbx site | (Wu et al., 2003) |

| bFGF (bFGF) | Hoxb7 | Ex vivo | cgcTAATCTgg | ND | ND | Human | (Caré et al., 1996) |

| egl-1+5995 (egl-1) | MAB-5 | In vivo | cgtTGATTTATTTtta | CEH-20 | ND | C. elegans | (Liu et al., 2006) |

| apME680 (ap) | Antp | In vivo | ccaATTAtttTGATTAATGCcaa; cccATAAATAATATtaa; tttTTATGAgtt; ttgAAATGAact; tgaATTATGATTATTGCcat |

Exd† | ND | Drosophila; exd required in vivo | (Capovilla et al., 2001) |

| Tsh (tsh) | Antp, Ubx | In vivo | aacTAATGTAATTACaaa; tgaTAATTGact; cacATAAATctt; tttTAATATttt |

ND | ND | Drosophila; Cluster of Hox binding sites tested by deletion | (McCormick et al., 1995) |

| sal1.1 (sal) | Ubx | In vivo | ttaTAATgTGCCCGTCTTAATATgat | Not Exd or Hth | Mad/Med | Drosophila; exd and hth not required in vivo | (Galant et al., 2002; Walsh and Carroll, 2007) |

| knot (knot) | Ubx | In vivo | gctTAATTTg; gctTAATTCt; cacTAATTAt; gccTAATTGTAATTGTTATTATTAATTAa |

Not Exd or Hth | ND | Drosophila; Hox sites are additive, exd and hth not required in vivo | (Hersh and Carroll, 2005) |

| B3 (BTub60D) | Ubx | In vivo | ttcATAATTGcagcggccacactcCAATTAAatt | ND | ND | Drosophila | (Kremser et al., 1999) |

| CG13222-site1 (CG13222) | Ubx | In vivo | gtgTAATTTatc | Not Exd or Hth | ND | Drosophila; exd and hth not required in vivo | (Hersh et al., 2007) |

| Antp-P2 (Antp) | Ubx, AbdA | In vivo | 30 Hox binding sites | ND | ND | Drosophila; Activity lost when all 30 sites are mutated. | (Appel and Sakonju, 1993) |

| DMX-R (Dll) | Ubx, AbdA | In vivo | gcaCTATAAAaCTGTCCgcggGAATGA TTTAATTTcccaAATATTgtc |

Exd, Hth, En | Slp | Drosophila; Slp and En function as repressors | (Gebelein et al., 2004) |

| dpp-midgut enhancer (dpp) | Ubx, AbdA | In vivo | caaaTTTATTACTAATTGGGtgTGAATTGC aggcagtgcaagtgctgca tatgcagcatgcagc ATAATCGAAatgggtgCTAATTGATag |

Exd | ND | Drosophila; Atypical Exd binding site, additional Hox and Exd sites required | (Capovilla and Botas, 1998; Capovilla et al., 1994; Chan et al., 1994; Manak et al., 1994; Stultz et al., 2006; Sun et al., 1995) |

| RhoA (rho) | AbdA | In vivo | agtTCATTGATTGACATTTTTATTAtgc | Exd, Hth | Sens | Drosophila; Sens competes for binding with AbdA-Exd-Hth complexes | (Li-Kroeger et al., 2008) |

| XC-Box2 (wg) | AbdA | In vivo | gcaTAATCTAATTGcgg | Not Exd or Hth‡ | Mad, Medea, Creb | Drosophila; Exd and Hth do not form complexes with AbdA in vitro | (Grienenberger et al., 2003) |

| AH5 (Hoxa4) | Dfd, Scr, Antp, Ubx & AbdA | In vivo | ggCAATTAAATTTATGGgggcTATAATTActg | ND | ND | Mouse; Possible role for Exd, repressed by AbdA; activated by other Hox | (Haerry and Gehring, 1997) |

| FkhCON (synthetic) | Scr, Antp, Ubx, AbdA | In vivo | tcaAGATTTATGGcca | Exd, Hth | ND | Synthetic; Fkh250 binding site mutated to consensus Hox-Exd site, repressed by AbdA, activated by other Hox | (Ryoo and Mann, 1999) |

| MLC (MLC1/3) | Hoxc8, Hoxa10 | Ex vivo | cttATTAAATTAcCATGTGtga | ND | ND | Rat; Factor binding to CATGTG (E-box) not identified, Hoxc8 activates and Hoxa10 represses | (Ceccarelli et al., 1999; Houghton and Rosenthal, 1999; Rao et al., 1996) |

| SBE (OPN) | Hoxc8, Hoxa9 | Ex vivo | atgCAGTCtataaatgaaaagggtagt TAATGAcat |

ND | Smad1, Smad3, Smad4 | Mouse; Smad3 directly binds DNA site while Smad1 and Smad4 antagonize Hox binding | (Shi et al., 2001; Shi et al., 1999) |

| EphB4-1365 (EphB4) | Hoxa9 | Ex vivo | agcTTATT | ND | ND | Human | (Bruhl et al., 2004) |

| E-510 (E-selectin) | Hoxa9 | Ex vivo | atgCAATTTTATTAAtat | ND | ND | Human | (Bandyopadhyay et al., 2007) |

| N-CAM (N-CAM) | Hoxc6, Hoxb8, Hoxb9 | Ex vivo | tTAATAATtac; cctTAATCAg | ND | ND | Mouse; Hoxc6 and Hoxb9 activate while Hoxb8 represses reporter expression ex vivo | (Edelman and Jones, 1995; Jones et al., 1993; Jones et al., 1992) |

| p21A10RE (p21) | Hoxa10 | Ex vivo | tttTTATAAttt | Pbx1a*, Meis1b* | ND | Human; Cotransfection of Pbx1a and Meis1b increased reporter expression ex vivo, no direct binding sites identified | (Bromleigh and Freedman, 2000) |

| B3A (B3-integrin) | Hoxa10 | Ex vivo | aatGTTATTTtta | ND | ND | Human; Hox binding sites not confirmed by mutagenesis | (Daftary et al., 2002) |

| EMXC (Emx2) | Hoxa10 | Ex vivo | tgtTTATGTgat | Not Pbx‡ | ND | Human; Pbx did not form complexes with Hoxa10 in vitro | (Troy et al., 2003) |

| Runx2-site1 (Runx2) | Hoxa10 | Ex vivo | aggTTATAGctt | ND | ND | Rat | (Hassan et al., 2007) |

| PPE (Ren-1c) | Hoxd10 | In vivo | tgtTTCCACAct; cgcTTCCggc; cttTGATTTATTAccc | Pbx1b, Prep1* | N1IC, Ets-1 | Mouse; Homeodomain of Prep1 not necessary for activation ex vivo, Prep1 binding site not identified | (Glenn et al., 2008; Pan et al., 2005; Pan et al., 2001) |

| Six2 (Six2) | Hox11 | In vivo | gTTATCTgacccggggcctgcccgcgcca GacaatagTCGaGTCAaattaTTc |

ND | Pax2, Eya1 | Mouse | (Gong et al., 2007) |

| Enpp2 (Enpp2) | Hoxa13 | Ex vivo | TTAATTG; TTAACAT; TTTATAT | ND | ND | Mouse | (McCabe and Innis, 2005) |

| Sostdc1 (Sostdc1) | Hoxa13 | Ex vivo | 15 sites tested | ND | ND | Mouse | (Knosp et al., 2007) |

| EphA7-site 3 (EphA7) | Hoxa13 Hoxd13 | Ex vivo | ataTTATTGgag | ND | ND | Mouse | (Salsi and Zappavigna, 2006) |

| hHa2-motifs: 1, 3, 6, 11 (hHa2) | Hoxc13 | Ex vivo | aaaTTAATTAgcag; tctTTTATTGgaa; cttTTAATGAaag; catTTAATATgttg |

Not Meis/Prep | ND | Human; Meis/Prep localization cytoplasmic | (Jave-Suárez and Schweizer, 2006; Jave-Suárez et al., 2002) |

| hHa5-motifs: 2, 3, 4, 6, 9, and 13 (hHa5) | Hoxc13 | Ex vivo | actTTAATGAgga; gttTTAATAGaaa; aggTTAATGAggg; tatTTTATGAgact; tctTTTATTGgcct; cagTTAATTGgac |

Not Meis/Prep | ND | Human; Meis/Prep localization cytoplasmic | |

| hHa7-motif 2 (hHa7) | Hoxc13 | Ex vivo | gctTTAATGAgct | ND | ND | Human | |

| Foxq1 (Foxq1) | Hoxc13 | Ex vivo | accTTCATTAcaa; tccTCCATAAAaca; agcTTAATAGGgac | ND | ND | Mouse; Other Hoxc13 sites may be required | (Potter et al., 2006) |

| BE3-6 (yellow) | AbdB | In vivo | aggTCGTAAAAcgtatttttacccatttgcatgtTTATTATGcgt | ND | ND | Drosophila | (Jeong et al., 2006) |

| BabDE (bab) | AbdB | In vivo | 7 TTTAT, 7 TTTAC, 8 TTAT, and 2 ACAATGT binding sites |

ND | Dsx | Drosophila | (Williams et al., 2008) |

| i4c-S2 (psa-3) | NOB-1 | In vivo | tttTGATAGTAATttt | CEH-20 | ND | C. elegans; CEH-20 facilitates NOB-1 DNA binding independent of its own binding site | (Arata et al., 2006) |

a Tested only in vitro.

b Half-site not directly tested.

Tested ex vivo.

d PBC-binding site recognized in sequence but untested.

Targets are ordered according to Hox paralog and are derived from human, mouse, chicken, Drosophila, and C. elegans. All of these elements have been shown to require direct Hox input for activity either in vivo or ex vivo (cell culture). Colored shading in the first column indicates if the element is repressed, activated or both (red, green, and blue, respectively) by Hox input. Nonadjacent binding sites within the same enhancer are separated by semicolons. Underlined sites are shared between two proteins using the colors defined in the DNA-binding site column. ND, not determined.

Given the high degree of specificity required for some Hox functions, and that there are dozens of Hox genes in vertebrates, it is perhaps surprising how few bona fide Hox cofactors have been identified. One answer to this paradox, discussed later in this chapter, comes from a recent atomic-level resolution view of how TALE cofactors bind to DNA with Hox proteins. Another possible answer, especially in vertebrates, is that multiple Pbx and Meis/Prep genes encode for proteins with different biochemical properties and thus expand the number of Hox cofactors. Perhaps analogously, although Drosophila has a single exd-like gene and a single hth-like gene, alternative splicing of Drosophila hth also adds to the repertoire of Hox cofactors present in the fly (Noro et al., 2006). Specifically, hth encodes both homeodomain-containing and homeodomain-less (HDless) isoforms. Not only do both of these isoforms contribute to hth functions, there is a clear division of labor for these isoforms. For example, the homeodomain-containing form of Hth is not required for a large number of embryonic functions, including many (but not all) Hox-dependent functions. In contrast, the homeodomain-containing form is essential for hth to specify antennal development, which is one of its Hox-independent functions. The fact that these two Hth isoforms exist suggests the possibility that they may also be used in different ways to achieve Hox specificity. Strikingly, in C. elegans, the gene psa-3 encodes an HDless Hth/Meis ortholog (Arata et al., 2006). Thus, C. elegans produces a very similar HDless isoform, but via gene duplication and truncation, instead of by alternative splicing as in Drosophila and vertebrates. The presence of HDless isoforms of Hth/Meis in C. elegans, Drosophila, and vertebrates reinforces the idea that it carries out critical functions that are distinct from those executed by homeodomain-containing isoforms.

Although exd appears to produce only a single isoform, some of the vertebrate Pbx genes produce multiple isoforms via alternative splicing (Milech et al., 2001; Monica et al., 1991; Wagner et al., 2001). Using the yeast two-hybrid assay, some evidence exists that a subset of isoforms have distinct abilities to interact with Meis 1, Meis 2a, and Prep1 (Milech et al., 2001). Such differences may also be important for Hox specificity, and may be reflected in the arrangement of binding sites for Hox and TALE proteins in Hox-targeted cis-regulatory elements.

5. What Do In Vivo Hox-Binding Sites Look Like?

An important approach to understand how Hox proteins regulate target gene expression, and to reveal potential generalizations, is to examine the cis-regulatory elements they directly bind to in vivo. Once a set of in vivo-validated Hox-targeted cis-regulatory elements are in hand, several questions can be asked. These include: How many also require input from known cofactors? How many Hox-binding sites are present in each element?, and What other regulatory inputs are there? To provide initial answers to these questions, we have surveyed the literature with the goal of cataloging the majority of the direct Hox-binding sites that have been examined to date, in both vertebrates and invertebrates. By “direct,” we included in this survey only Hox-binding sites that have been shown by a reporter gene assay (in cell culture (ex vivo)or in vivo) to be required for the activity of a cis-regulatory element (Table 3.1). Therefore, some recent genome-wide studies fell short of these stringent criteria for validation (Ebner et al., 2005; Hueber and Lohmann, 2008; Hueber et al., 2007; McCabe and Innis, 2005). Below, we discuss the results of this survey and their implications for Hox specificity.

We found 66 cis-regulatory elements for which there is strong experimental evidence for direct and essential Hox input (Table 3.1). Of these, 29 have been shown to use PBC cofactors (Exd/Pbx/Ceh-20). Two additional elements appear, by sequence, to have PBC-Hox composite sites, making a total of 31 elements with PBC-Hox sites in this data set (Table 3.1). For seven elements, there is experimental evidence that they do not use these cofactors. The remaining 30 targets have not been directly tested for PBC input, although two of these have been shown not to use Hth/Meis or Prep proteins (Table 3.1). Finally, among the 66 targets in this list, there are 11 examples in which other direct inputs have been shown to be required for the activity of the cis-regulatory element.

Although we need to cautiously interpret this relatively small number of elements, several interesting features emerge by analyzing these examples. First, it is noteworthy that for a large fraction of the elements (29 of the 36 elements where it was examined) Hox proteins bind their binding sites cooperatively with a PBC factor (Table 3.1). This is likely an overestimate of the frequency of PBC-Hox-binding sites, because sequence gazing of the 30 elements that were untested for PBC input suggests that many do not have an obvious PBC-binding site. Nevertheless, the abundance of PBC-Hox composite-binding sites in this list underscores the widespread contribution of these cofactors to Hox-binding in vivo. Strikingly, with only two exceptions (Dll DMX and fkh250con), PBC-Hox-binding sites are used for gene activation, not repression. In contrast, the Hox sites that do not have clear PBC input are used for both repression and activation. If this overall correlation continues to hold up, it suggests that PBC-Hox complexes are, in general, more likely to recruit transcriptional coactivators rather than corepressors.

Second, there is a trend for the anterior Hox proteins (paralogs 1-5) to use PBC cofactors more than the posterior Hox proteins (paralogs 6-13) (Table 3.1). Of the 30 elements targeted by a Hox 1-5 paralog, 20 have a required PBC-Hox-binding site. In contrast, of the 36 elements targeted by a Hox 6-13 paralog, only nine have been shown to have an essential PBC-Hox-binding site.

Third, elements that do not have PBC input are more likely to have multiple Hox-binding sites than elements that have PBC input (Table 3.1). For those elements that use Hox-PBC sites, the average number of Hox-binding sites is 1.2 (ranging from 1 to 3), whereas for those elements that do not appear to use Hox-PBC sites, the average number of sites is 2.8 (ranging from 1 to 30). Thus, from this data set, it appears that Hox sites without PBC input often function in groups. If this trend holds up, it may reflect a lower affinity for non-PBC Hox sites when compared to PBC-Hox sites. Perhaps multiple non-PBC Hox sites are therefore required in an additive manner to elicit a transcriptional response.

Although many of the targets listed in Table 3.1 have Hox-binding sites that do not appear to have direct PBC input, we avoid calling them Hox “monomer” sites because it is plausible that currently unidentified factors bind with Hox proteins (cooperatively or noncooperatively) to these sites. In fact, when true Hox “monomer”-binding sites—synthetic, but high-affinity-binding sites—were used to drive a reporter gene in Drosophila embryos, they did not produce expression patterns consistent with their ability to bind dozens of homeodomain proteins (Vincent et al., 1990). This experiment, together with the analysis of in vivo Hox targets listed in Table 3.1, suggest that Hox proteins never work as monomers.

The arrangement of binding sites also varies in interesting ways within this data set. Of the 40 PBC-Hox sites (distributed among 31 elements), 33 have the PBC half-site adjacent to the Hox half-site, and the majority of these (26) have the structure nnATnnATnn (where the first and second ATs form the core of the PBC and Hox half-sites, respectively). In one case (DMX-R from Dll) the PBC-Hox site has the structure nnATnnnATnn and there is one example (in the dpp midgut element) where the Hox site precedes the PBC site (Table 3.1). It is possible that these atypical arrangements help these sites be more selective for a subset of Hox proteins. It is also possible that the unique three-dimensional architectures of the protein complexes assembled by these atypical PBC-Hox-binding sites are important for recruiting additional, element-specific transcriptional effectors. Consistent with these ideas, both in vitro Hox-binding specificity and in vivo activity of DMX-R were reduced when the spacing between the two half-sites was changed from 3 to 2 bp (Gebelein et al., 2002). Of the 40 PBC-Hox sites, eight have been shown to have a nearby Hth/Meis or Prep-binding site. Although the low number of identified Hth/Meis/Prep-binding sites may in part be because they are not always looked for, it may also reflect the fact that there are isoforms of Hth and Meis that do not have a homeodomain and thus would not be expected to make DNA contacts.

Because both PBC-Hox and Hth/Meis/Prep-binding sites have a clear orientation, four possible arrangements of these two binding sites are possible. Interestingly, of these four, only one is not observed (TGACAG...PBC-Hox, where TGACAG represents one orientation of a Hth/Meis site) (Table 3.1). That three of the potential orientations have been observed suggests an inherent flexibility in how these complexes can bind DNA. Further, because the different orientations are expected to orchestrate the assembly of protein-DNA complexes that have unique three-dimensional architectures, these observations also suggest the possibility that they have unique biochemical properties, such as their ability to recruit additional transcriptional coactivators or corepressors.

An unusual arrangement of binding sites is found in an Abd-A-targeted element from the Drosophila rhomboid (rho) gene (Table 3.1) (Li-Kroeger et al., 2008). In this element, the order of binding sites is PBC-Hth-Hox. Robust cooperative DNA binding to this element was observed between a preformed Exd-Hth dimer and Abd-A. In principle, because both Exd and Hth are TALE homeodomain proteins, they both have the ability to bind the “YPWM” motif of Abd-A, raising the question of which, if either, TALE motif Abd-A is interacting with. Interestingly, mutation of the Hth site, but not the Exd site, dramatically reduced complex formation (Li-Kroeger et al., 2008), suggesting that the Hth-binding site and, perhaps, the Hth TALE motif are more critical for complex formation. Perhaps analogously, a direct Hox-Hth interaction was also proposed to exist in the repressor element from the Dll gene (Table 3.1) (Gebelein et al., 2004). The existence of these atypical arrangements suggests that there may be additional flexibility in how Hox, PBC, and Meis/Hth/Prep proteins assemble onto target DNAs. The dissection of the rho element in particular emphasizes that carrying out careful mutagenesis and follow-up in vivo studies will be critical for identifying additional novel architectures that are used by these factors in vivo.

As discussed above, two recent reports described the in vitro binding site preferences for nearly all mouse and fly homeodomains, including all Hox homeodomains (Berger et al., 2008; Noyes et al., 2008). How do these results compare with the in vivo Hox-binding sites listed in Table 3.1? To answer this question, we generated binding site logo diagrams using the B1H-derived binding sites for the Drosophila Hox homeodomains (Noyes et al., 2008) and the in vivo Hox-binding sites listed in Table 3.1 (Fig. 3.2). The B1H-derived logos are all based on at least 19 individual binding sites, while the number of individual in vivo binding sites for each Hox protein that went into this analysis ranged from 12 (for Scr/Hox5) to 57 (for Ubx/Hox7). Side-by-side analysis of these two sets of sequences reveals some noteworthy differences (Fig. 3.2). First, consistent with the high proportion of PBC-Hox sites in the Hox1/Labial targets, the in vivo consensus sequence readily identified a PBC half-site (TGAT). In addition, while the B1H selection tended to identify TAATTA for Hox1/Labial, GGATGG is commonly observed in the in vivo data set for these Hox proteins. Other, though less dramatic, differences are also observed between the B1H and in vivo data sets for nearly all of the Hox paralogs (Fig. 3.2). These comparisons reinforce the view that the in vivo environment, due to the presence of other cofactors, collaborators, or differences in DNA and/or chromatin structure, influences Hox-binding site preferences.

6. Insights into Hox Specificity from Structural Studies

Several monomeric homeodomain-DNA structures have been solved, and all reveal a very similar mode of DNA recognition by this DNA-binding domain (Gehring et al., 1994). Briefly, the third alpha-helix, also called the recognition helix, lies in the major groove of the DNA, where it makes several direct and water-mediated contacts with specific bases and the phosphate backbone. Ile47, Gln50, Asn51, and Met54, residues that are present in all Hox homeodomains, are primarily responsible for making these contacts. In addition, the so-called N-terminal arm, which precedes the first alpha-helix, is typically observed in the minor groove. Arg5, an N-terminal arm residue present in nearly all homeodomains, is the most commonly observed residue in the minor groove.

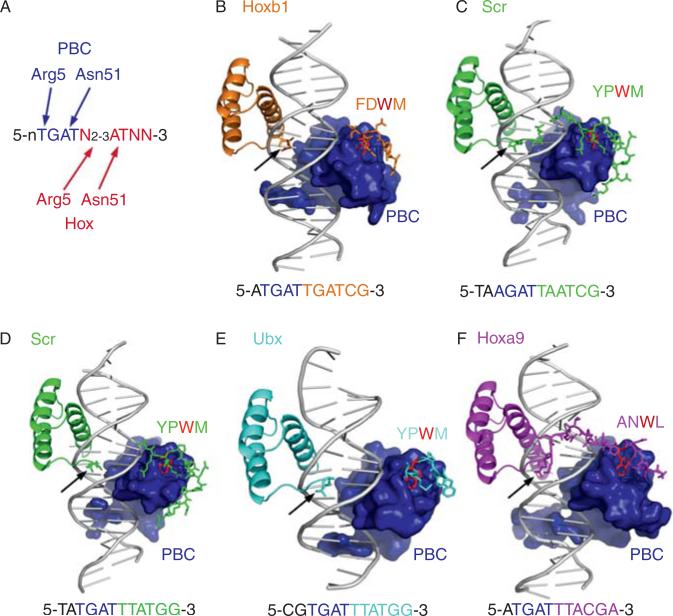

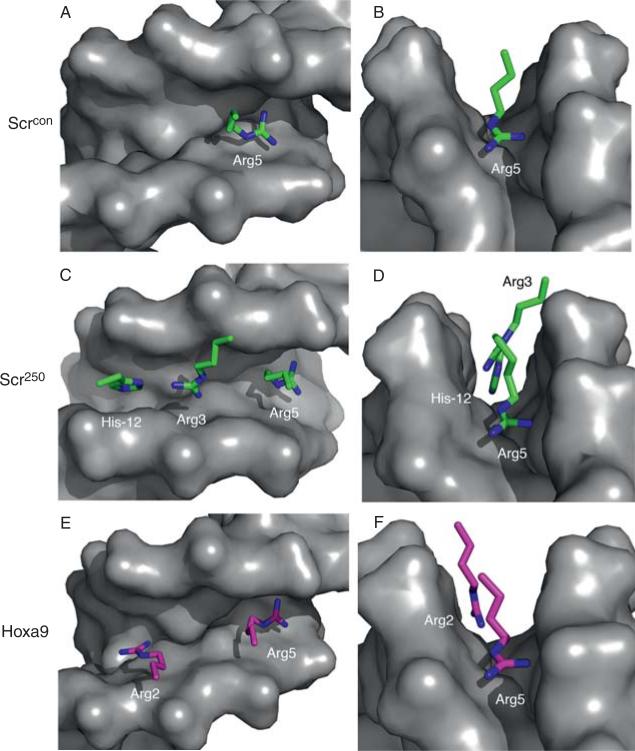

In addition to these monomeric homeodomain-DNA structures, we now have X-ray structures of five different PBC-Hox-DNA complexes (Fig. 3.4). The Hox homeodomains in these structures recognize the DNA using the same contacts that were observed in the monomeric structures, demonstrating that the presence of PBC does not grossly alter the way in which Hox homeodomains bind DNA. In all five of the PBC-Hox structures (with four different Hox proteins: Hoxb1, Scr, Ubx, and Hoxa9), the PBC and Hox homeodomains bind DNA in a head-to-tail orientation, with very similar overall arrangements. In all five structures the Hox YPWM motif binds the hydrophobic TALE pocket in the PBC home-odomain. Thus, these four Hox proteins have the capacity to bind DNA cooperatively with PBC proteins using very similar protein-protein and protein-DNA contacts. However, we note that the currently available structures provide an incomplete picture because, for some binding sites, other protein motifs, such as the UbdA motif of Ubx and Abd-A, play an important role in forming PBC-Hox-DNA complexes (Merabet et al., 2007). Currently, no structural information exists about these domains or how they contact PBC proteins.

Figure 3.4.

Common and unique features of PBC-Hox-DNA complexes. (A) Consensus PBC-Hox-binding sites have a PBC half-site (typically TGAT or AGAT, blue) and a Hox half-site (typically NNATNN, red). Minor groove (Arg5) and major groove (Asn51) contacts observed in all five of the PBC-Hox crystal structures are indicated. N2-3 reflects the observation that the PBC and Hox Asn51-contacted “AT” are usually separated by 2 bp, but 3 bp spacings have also been observed. (B)-(F) Overviews of the five existing PBC-Hox-DNA crystal structures. In all examples, the PBC protein (for most examples, just its homeodomain) is shown as a blue surface. The Hox proteins, which include the YPWM motif (which is FDWM in Hoxb1 and ANWL in Hoxa9), linker, and homeodomain, are color-coded as indicated. Only side chains around the YPWM, linker, and N-terminal arm are shown; homeodomain helices and loops are shown in cartoon format. The Trp (W) in the YPWM motif is colored red in all cases to indicate its conserved interaction with the TALE motif in the PBC homeodomain. In all cases, Arg5 of the Hox N-terminal arm is observed in the minor groove (black arrows). In only two cases (C; Exd-Scr bound to fkh250 and F; Pbx-Hoxa9 bound to a consensus sequence) are additional N-terminal arm and linker regions observed; these regions are disordered in the other three structures. The DNA sequences present in these structures are shown below the structure, with the PBC and Hox half-sites color-coded. These images were generated using PyMol; the PDB accession numbers for these structures are (B) 1B72, (C) 2R5Z, (D) 2R5Y, (E) 1B8I, and (F) 1PUF.

PBC proteins not only bind cooperatively to DNA with Hox proteins, they also increase Hox-DNA-binding selectivity. This phenomenon is best illustrated with a few examples. In the absence of cofactors, the Hox1/Labial paralog shows a preference for binding the sequence TAATTA (Fig. 3.2) (Berger et al., 2008; Noyes et al., 2008). In the presence of a PBC protein, a PBC-Hox1/Lab heterodimer prefers to bind the sequence TGAT[t/g]GATgg, where [t/g]GATgg is the Hox-binding site (base pairs with brackets indicate multiple possibilities at the same position and lowercase letters indicate only partially preferred base pairs) (Fig. 3.2). In contrast, while Ubx also prefers to bind TAATTA as a monomer, it will readily bind TGATTTATTT as a PBC-Ubx heterodimer, where TTATTT is the Hox-binding site (Berger et al., 2008; Noyes et al., 2008) (Fig. 3.2). Thus, the presence of PBC changes the DNA-binding preferences of both Labial/Hox1 and Ubx, but toward different sequences.

These observations raise the question of how the same cofactor can generate two different outcomes for these two Hox paralogs. The likely answer is that the specificity information is in the Hox protein, but is only revealed in the presence of the cofactor. Two recent crystal structures of PBC-Hox-DNA complexes support this idea (Joshi et al., 2007). In one, an Exd-Scr heterodimer is bound to a paralog-specific PBC-Hox-binding site (fkh250) from the fkh gene, an in vivo Scr target gene. A second crystal structure shows the same two proteins bound to a consensus PBC-Hox sequence (fkh250con). Importantly, additional protein-DNA contacts were observed in the Exd-Scr-fkh250 complex, but not in the Exd-Scr-fkh250con complex. These contacts are derived from the N-terminal arm of the Scr homeodomain and, surprisingly, a nonhomeodomain residue in the linker region between Scr's YPWM motif and homeodomain. Both of these side chains are inserted into the minor groove of the fkh250-binding site (Figs. 3.4 and 3.5) (Joshi et al., 2007). Two additional observations are of interest. First, the DNA minor groove where these two side chains insert is unusually narrow, and significantly narrower than the analogous region of the fkh250con-binding site (Fig. 3.5). This suggests that subtle differences in DNA structure are likely to contribute to Hox-binding specificity. Second, the residues making these minor groove contacts, which are part of a normally unstructured region of Scr, require the YPWM-Exd interaction to be positioned in close proximity to the minor groove. Thus, the paralog-specific binding of Scr to its binding site in fkh depends on three contributing features (1) an unusual DNA structure; (2) paralog-specific residues in the Scr homeodomain and linker that insert into this DNA structure; and (3) the YPWM-Exd interaction, which positions the N-terminal arm and linker region so that this normally unstructured peptide can make these contacts.

Figure 3.5.

Interactions between Hox proteins and the DNA minor groove. Shown are images from X-ray crystal structures of PBC-Hox-DNA complexes, focused only on the interaction between the minor groove (shown as the gray surfaces) and the amino acid side chains of N-terminal arm/linker residues. The left-hand images (A, C, E) look into the minor groove from the top; the right-hand images (B, D, F) look along the axis of the minor groove. (A, B) Exd-Scr bound to the fkh250con consensus-binding site. Only Arg5 from the N-terminal is observed in the minor groove. (C, D) Exd-Scr bound to the fkh250 in vivo binding site. In contrast to the fkh250con structure, Arg3 (from the N-terminal arm) and His-12 (from the linker) are observed in the minor groove, in addition to Arg5. Note also that the minor groove in the fkh250 structure appears narrower than in the fkh250con structure (compare B with D). See Joshi et al. (2007) for details. (E, F). In the Pbx-Hoxa9 structure, one additional N-terminal arm residue, Arg2, is observed, together with Arg5. The Hoxa9 linker is unusually short (four residues), and none of them are seen inserting into the minor groove. See LeRonde-LeBlanc and Wolberger (2003) for details.

Although these structures provide insights into why Exd-Scr specifically binds fkh250, they raise the question of how general these findings are. Two additional observations suggest that the underlying principles revealed by these structures may, in fact, be a general feature of PBC-Hox-DNA interactions, at least for paralog-specific and semi-paralog-specific target sites. For one, Hox N-terminal arms and linker regions are evolutionarily conserved in a paralog-specific manner (Joshi et al., 2007; Mann, 1995; Morgan et al., 2000). The two minor groove inserting residues in Scr are conserved in all Hox5 paralogs, while other Hox paralogs have different N-terminal arm and linker sequences that are also equally conserved in a paralog-specific manner. Second, another PBC-Hox structure, that of Pbx-Hoxa9, also has significant N-terminal arm-minor groove contacts (LaRonde-LeBlanc and Wolberger, 2003) (Figs. 3.4 and 3.5). Although the binding site used in the Pbx-HoxA9 structure is not from an in vivo HoxA9 target, the N-terminal arm-minor groove contacts are also dependent on the YPWM-Pbx interaction, illustrating the potential generality of DNA minor groove recognition by PBC-Hox complexes. The Pbx-Hoxa9 structure also reveals significantly more contacts with the phosphate backbone of the DNA, perhaps accounting for its higher affinity compared to other PBC-Hox complexes (LaRonde-LeBlanc and Wolberger, 2003).

Along the same lines, it is also noteworthy that linker length—and, consequently, the distance between the YPWM motif and the N-terminal arm—varies significantly among Hox proteins. Not only are there huge differences in linker lengths (ranging from >50 in Labial to <5 in Hoxa9), linker length roughly correlates with Hox paralog: anterior (3′) Hox paralogs have a much greater tendency for long linkers than more posterior (5′) Hox paralogs. In addition, Hox linkers also vary for individual paralogs due to alternative splicing; the Ubx linker, for example, ranges from 8 to 51 depending on the Ubx isoform (Kornfeld et al., 1989; O'Connor et al., 1988). Consequently, the distance between the YPWM motif and the homeodomain varies and would therefore be expected to affect how the N-terminal arm and/or linker region interacts with the DNA. These intriguing observations contribute to the idea that DNA contacts made by linker and N-terminal arm residues may be generally critical for paralog-specific and cofactor-dependent DNA binding. These observations are also consistent with the alternative idea that linker residues interact with additional proteins, although such factors have not yet been identified (Merabet et al., 2003).

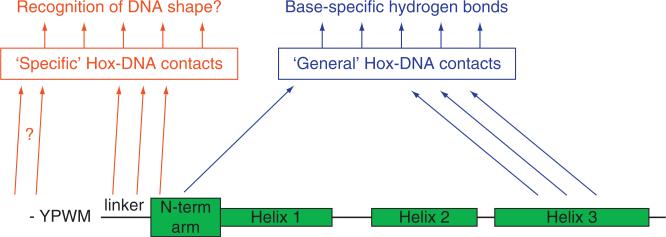

In summary, the common and unique features revealed in these five PBC-Hox-DNA structures, together with previously solved monomeric homeodomain-DNA structures, suggest that DNA recognition by Hox proteins uses two tiers of information that provide different degrees of specificity (Fig. 3.6). The first tier uses DNA-contacting residues that are common to all Hox proteins (Arg5, Ile47, Gln50, Asn51, and Met54) to promote Hox binding to “AT”-rich sequences, such as TAAT[gt][ga]. The second tier uses additional DNA-contacting side chains that come from the N-terminal arm and linker regions; these contacts are cofactor-dependent and paralog-specific (Fig. 3.6). Further, at least for the case of Exd-Scr bound to fkh250, these side chains recognize a DNA structure, rather than a specific DNA sequence. The fact that N-terminal arm and linker residues are conserved in a paralog-specific manner suggests that the two tiers of recognition may underlie the recognition of paralog-specific DNA sequences by other Hox-cofactor complexes.

Figure 3.6.

Two tiers of Hox-DNA-binding specificity. Hox proteins bind DNA using two levels of protein-DNA contacts. DNA contacts made by Arg5 (in the N-terminal arm) and Ile47, Gln50, Asn51, Met54 (in the third helix) are used by all Hox proteins to bind “AT”-rich DNA sequences (“general” Hox-DNA contacts), but are not good at distinguishing between Hox paralogs. With the help of cofactors (such as PBC proteins), paralog-specific DNA contacts are mediated by linker and N-terminal arm residues. “General” DNA contacts make hydrogen bonds in the DNA major groove. “Paralog-specific” DNA contacts may read a DNA structure, such as the narrow minor groove seen in the Exd-Scr-fkh250 structure.

7. Activity Regulation of Hox Proteins: The Role of Hox Collaborators

Although TALE family proteins clearly play an important role in DNA-binding site recognition, Hox proteins use these cofactors to both activate and repress target genes, raising the question of how gene activation versus repression is determined. Although there is currently only one example, one answer is that Hox proteins may use dedicated repressors, such as En, as Hox cofactors in gene repression (Gebelein et al., 2004). Another possibility, which will be no surprise to people used to thinking about cis-regulatory elements, is that additional factors bind to Hox-targeted elements and contribute to their activities. Given the increasing number of directly regulated Hox targets that have been characterized, several such accessory factors, which we refer to here as Hox collaborators, have been identified. We have classified a factor as a Hox collaborator if it provides a direct and essential input into a Hox-regulated element, but has not been definitively shown to bind DNA cooperatively with Hox proteins (Table 3.1). These factors include the Drosophila Forkhead domain protein Sloppy paired (Slp), which collaborates with Ubx and Abd-A to repress Dll in the Drosophila abdomen (Gebelein et al., 2004). Interestingly, recent results suggest that a vertebrate ortholog of Slp, FoxP1, collaborates with Hox proteins during the establishment of motor neuron identities in the mouse (see Chapter 1) (Dasen et al., 2008; Rousso et al., 2008). Thus, the collaboration of FoxP1/Slp (and perhaps other Forkhead domain factors) with Hox proteins appears to be evolutionarily conserved. Like En, Slp may be a dedicated transcriptional repressor due to its Groucho interaction domain, thus providing a mechanism to explain the regulatory sign of Hox-Slp-targeted genes. In addition to these cases, protein-protein interaction and genetic studies suggest that the range of potential Hox collaborators is extensive (Kataoka et al., 2001; Luo et al., 2004; Plaza et al., 2008; Prévôt et al.,2000).

Transcription factors that provide cells with identity information, like the Hox factors, have been generally referred to as Selector transcription factors, a term originally coined 40 years ago to describe common properties of the genes Ubx and en (García-Bellido, 1975; Mann and Carroll, 2002; Mann and Morata, 2000). More recently, selector proteins have been proposed to frequently, if not always, function together with effector transcription factors that are downstream of cell-cell signaling pathways (reviewed previously by Bondos and Tan, 2001; Curtiss et al., 2002; Mann and Affolter, 1998). Thus, not surprisingly, as more elements that are directly targeted by Hox proteins are dissected, signal effector transcription factors are being identified as Hox collaborators. In particular, vertebrate and Drosophila SMADs, effectors of the TGF-beta and Decapentaplegic (Dpp) pathways, have been identified as Hox collaborators in several cis-regulatory elements (Galant et al., 2002; Grienenberger et al., 2003; Shi et al., 1999, 2001; Walsh and Carroll, 2007) (Table 3.1). Although SMAD-Hox-DNA-binding cooperativity has not been described, there are several reports suggesting that SMADs and Hox proteins can directly interact with each other (Wang et al., 2006; Williams et al., 2005; Zhou et al., 2008). Such interactions may be critical for building an enhanceosome-like structure on Hox-targeted cis-regulatory elements. Although the number of examples shown to have direct inputs by signaling effectors is currently low, genetic analyses suggest that this phenomenon is likely to be a general feature of Hox-targeted cis-regulatory elements, and will probably extend to other signaling pathways, including Hedgehog (Hh), Wnts, and Notch (Arata et al., 2006; Crickmore and Mann, 2007, 2008; Hersh et al., 2007; Joulia et al., 2006; Marty et al., 2001; Merabet et al., 2005; Weatherbee and Carroll, 1999).

Like Hox cofactors, the presence of a particular Hox collaborator does not guarantee the sign of the transcriptional regulation. In the sal1.1 element, for example, Ubx collaborates with Mad/Medea to repress transcription, while in the XC midgut element from the wg gene, Mad/Medea collaborates with Abd-A to activate transcription (Grienenberger et al., 2003; Walsh and Carroll, 2007). This difference is not simply due to different Hox paralogs, because both Ubx and Abd-A can both directly repress and directly activate transcription (Table 3.1). Instead, these observations imply that additional, currently unknown, factors are being recruited to these elements to determine the sign of the transcriptional regulation.

Based on these direct examples, together with the larger number of genetically defined examples of Hox—signaling collaborations, we suggest that it may be a general feature of the multiprotein complexes that are built on Hox-targeted cis-regulatory elements. In fact, because Hox proteins work in so many different developmental contexts, it is likely that Hox collaborators will ultimately include a very large number of different types of transcription factors. Perhaps the ability of Hox proteins and PBC-Hox dimers to interact with a large number of different collaborators makes these proteins such ideal regulators of cell type and tissue identities.

Yet, despite this flexibility, it is critical to stress that the Hox factors play the central role in the function (and/or the assembly) of these multiprotein complexes, because without them, these complexes cannot function. Moreover, for paralog-specific functions, the activity and/or assembly of these complexes must depend on the correct Hox paralog and cofactors. Because of their central role, we would therefore like to coin the term “Hoxasome” to describe these multiprotein complexes, which include the Hox proteins, their cofactors, and their collaborators.

8. Insights into Hoxasome Function from cis-Regulatory Element Architecture

One straightforward view for how Hoxasomes function is that, once assembled, they recruit coactivators, corepressors, and/or chromatin remodeling complexes that ultimately carry out transcriptional regulation much like any other enhanceosome. Indeed, consistent with this view, there have been numerous reports describing direct interactions between Hox proteins and/or TALE cofactors with these more general components of the transcriptional machinery (Chariot et al., 1999; Prince et al., 2008; Saleh et al., 2000; Shen et al., 2004) and, in some cases, activation and repression domains have been mapped in Hox proteins (Rambaldi et al., 1994; Tour, 2005; Viganò et al., 1998; Zhao et al., 1996). Covalent modifications, such as phosphorylation, have also been shown to influence Hox activities in interesting ways (Berry and Gehring, 2000; Galant and Carroll, 2002; Jaffe et al., 1997; Ronshaugen et al., 2002; Taghli-Lamallem et al., 2008; reviewed elsewhere by Pearson et al., 2005).

In addition, to these mechanisms, there are some recent examples suggesting that Hoxasomes may regulate transcription—and be regulated themselves—in other, mechanistically distinct ways. One example concerns the way in which Drosophila Abd-A activates the expression of the gene rho in the peripheral nervous system (PNS). Abd-A-dependent expression of rho, which encodes a protease required for the processing of a ligand for the epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptor pathway, is necessary for abdominal-specific cell types (Brodu et al., 2002). Abd-A carries out this paralog-specific function by assembling a multiprotein complex that includes both Exd and Hth cofactors (Li-Kroeger et al., 2008). However, instead of the Abd-A Hoxasome directly activating rho transcription, it appears that it functions by competing with the binding of another transcription factor, Senseless, which is a rho repressor. Thus, the architecture of the rho cis-regulatory element is organized in a manner whereby the sequence-specific binding of an Abd-A Hoxasome permits rho expression by blocking binding of the Senseless repressor. Perhaps analogously, a zinc finger protein called ZFPIP has been shown to bind to Pbx1 and inhibit the binding of Hoxa9-Pbx1 complexes to a Hox-PBC consensus site (Laurent et al., 2007). Thus, competition in DNA binding, rather than a direct influence on transcription, may underlie other examples of gene regulation by Hox factors.

A second interesting example of the importance of cis-regulatory element architecture comes from the analysis of an element from the Drosophila bric-a-brac (bab) gene, which is a direct target of Abd-B (Williams et al., 2008). The activity of this element in the fifth and sixth abdominal segments of females—but not males—is critical for the dimorphic nature of abdominal pigmentation in male and female flies (Williams et al., 2008). As Abd-B expression is the same in male and female flies, the sex-specific activities of this element stem from the Hox collaborator, doublesex (dsx), which is a downstream effector in the sex-determination pathway (Christiansen et al., 2002). dsx encodes both male and female-specific isoforms. In males, the Dsx-M isoform collaborates with Abd-B to repress bab, while in females, the Dsx-F isoform collaborates with Abd-B to activate this bab element. In this element, there are two required Bab-binding sites, and more than 15 Abd-B-binding sites, suggesting the existence an unusually Hox-dense Hoxasome (Table 3.1). Moreover, the analysis of the same cis-regulatory element from other Drosophila species in which abdominal pigmentation pattern is the same in males and females suggests that the dimorphic activity of the D. melanogaster bab element is due to the relative orientation and specific spacing of the Dsx and Abd-B-binding sites. Mechanistically, it is currently unclear if these changes affect the stable assembly of this Hoxasome or, alternatively, its ability to recruit transcriptional coactivators.

Both of the studies highlighted above emphasize the value in characterizing bona fide Hox-targeted cis-regulatory elements at high resolution. Moreover, they also make it clear that a complete understanding of gene regulation by Hox proteins not only depends on understanding how these transcription factors bind DNA, but also how the bound factors, together with their cofactors and collaborators, assemble and regulate transcription. We suspect that the discovery of additional regulatory mechanisms will depend on similar fine-scale analysis of other Hox-targeted cis-regulatory elements.

9. Conclusions

In this review, we have summarized a wide range of mechanisms that Hox proteins employ to regulate their target genes. For one, Hox proteins often require cofactors to bind to their binding sites in paralog-specific and semi-paralog-specific target genes. Cofactors may not be as essential, however, for shared Hox functions or those executed by Hox proteins in a unique regulatory environment, such as the Drosophila haltere. Structural studies have suggested that TALE family cofactors not only increase the size of the binding site, they help to impose additional structure onto otherwise unstructured homeodomain and nonhomeodomain residues, allowing them to read additional features present in Hox-cofactor-binding sites. It will be interesting to see how generally applicable this model for Hox-DNA binding (and perhaps other homeodomain proteins) will be as more PBCHox-DNA complexes are characterized at high resolution. Finally, we have also seen that Hox-regulated cis-regulatory elements utilize a potentially large number of protein collaborators, such as effector transcription factors that are downstream of cell-cell signaling pathways. The assembly of these multiprotein-DNA complexes, which we have called Hoxasomes to emphasize the central importance of the Hox input, is essential for dictating the sign (repression or activation) of the transcriptional regulation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Matthew Slattery for comments on the manuscript and Barry Honig for discussions related to this review. This work was supported by an NIH RO1 grant awarded to R.S.M.

REFERENCES

- Affolter M, Percival-Smith A, Müller M, Leupin W, Gehring WJ. DNA binding properties of the purified Antennapedia homeodomain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1990;87:4093–4097. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.11.4093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Affolter M, Slattery M, Mann RS. A lexicon for homeodomain-DNA recognition. Cell. 2008;133:1133–1135. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akam M. Hox and HOM: homologous gene clusters in insects and vertebrates. Cell. 1989;57:347–349. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90909-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appel B, Sakonju S. Cell-type-specific mechanisms of transcriptional repression by the homeotic gene products UBX and ABD-A in Drosophila embryos. EMBO J. 1993;12:1099–1109. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05751.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arata Y, Kouike H, Zhang Y, Herman MA, Okano H, Sawa H. Wnt signaling and a Hox protein cooperatively regulate psa-3/Meis to determine daughter cell fate after asymmetric cell division in C. elegans. Dev. Cell. 2006;11:105–115. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandyopadhyay S, Ashraf MZ, Daher P, Howe PH, DiCorleto PE. HOXA9 participates in the transcriptional activation of E-selectin in endothelial cells. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007;27:4207–4216. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00052-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger MF, Badis G, Gehrke AR, Talukder S, Philippakis AA, Peña-Castillo L, Alleyne TM, Mnaimneh S, Botvinnik OB, Chan ET, Khalid F, Zhang W, et al. Variation in homeodomain DNA binding revealed by high-resolution analysis of sequence preferences. Cell. 2008;133:1266–1276. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry M, Gehring W. Phosphorylation status of the SCR homeodomain determines its functional activity: essential role for protein phosphatase 2A,B’. EMBO J. 2000;19:2946–2957. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.12.2946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berthelsen J, Kilstrup-Nielsen C, Blasi F, Mavilio F, Zappavigna V. The subcellular localization of PBX1 and EXD proteins depends on nuclear import and export signals and is modulated by association with PREP1 and HTH. Genes. Dev. 1999;13:946–953. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.8.946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bessa J, Tavares MJ, Santos J, Kikuta H, Laplante M, Becker TS, Gómez-Skarmeta JL, Casares F. meis1 regulates cyclin D1 and c-myc expression, and controls the proliferation of the multipotent cells in the early developing zebrafish eye. Development. 2008;135:799–803. doi: 10.1242/dev.011932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]