Abstract

DYRKs are kinases that self-activate in vitro by auto-phosphorylation of a YTY motif in the kinase domain, but their regulation in vivo is not well understood. In C. elegans zygotes, MBK-2/DYRK phosphorylates oocyte proteins at the end of the meiotic divisions to promote the oocyte-to-embryo transition. Here we demonstrate that MBK-2 is under both positive and negative regulation during the transition. MBK-2 is activated during oocyte maturation by CDK-1-dependent phosphorylation of Serine 68, a residue outside of the kinase domain required for full activity in vivo. The pseudo-tyrosine phosphatases EGG-4 and EGG-5 sequester activated MBK-2 until the meiotic divisions by binding to the YTY motif and inhibiting MBK-2’s kinase activity directly, using a novel mixed-inhibition mechanism that does not involve tyrosine dephosphorylation. Our findings link cell cycle progression to MBK-2/DYRK activation and the oocyte-to-embryo transition.

Introduction

Dual-specificity tyrosine-regulated kinases (DYRKs) are a conserved family of eukaryotic kinases that belong with cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) and mitogen-activated kinases (MAPKs) to the CMGC kinase superfamily (Becker and Joost, 1999). DYRK activity depends on a YTY motif located in the kinase domain in a position similar to TXY activation loop motif of MAPKs. Unlike MAPKs, DYRKs catalyze their own tyrosine phosphorylation in an intramolecular reaction (Kentrup et al., 1996; Lochhead et al., 2005). Tyrosine auto-phosphorylation is one-off reaction catalyzed by a DYRK intermediate present only during translation (Lochhead et al., 2005). Mature DYRKs are not capable of tyrosine phosphorylation, but can phosphorylate substrates on serines and threonines. Because of their ability to auto-phosphorylate in vitro, DYRKs are considered self-activating kinases and it is not well understood how DYRKs are regulated in vivo (Yoshida, 2008).

DYRKs have been identified in both single-celled and multicellular eukaryotes; C. elegans MBK-2 belongs to the DYRK2 subclass (Yoshida, 2008). Studies in cell culture using Drosophila and mammalian DYRK2s have identified several potential substrates, including chromatin remodeling factors, the transcription factors p53, NFAT and GLI2 (Yoshida, 2008), and katanin p60 (Maddika and Chen, 2009), a substrate also shared by MBK-2 in C. elegans (see below). Although DYRKs have evolved to recognize a variety of substrates in different cell types, a common function linking all DYRKs may be the coordinate regulation of cell cycle, cell growth and cell differentiation (Yoshida, 2008).

MBK-2 functions in the oocyte-to-zygote transition (Pellettieri et al., 2003). This transition transforms the specialized oocyte into a totipotent zygote in two stages: oocyte maturation and egg activation. Oocyte maturation stimulates the first meiotic division (meiosis I) and ovulation into the spermatheca. Egg activation is triggered by fertilization, which stimulates meiosis II, meiotic exit, and the switch to mitosis (McNally and McNally, 2005; (Horner and Wolfner, 2008). MBK-2’s role in the oocyte-to-zygote transition is to modify oocyte proteins whose activity and/or stability need to change after meiosis. Five MBK-2 substrates have been identified so far: MEI-1, OMA-1, OMA-2, MEX-5 and MEX-6 (Guven-Ozkan et al., 2008; Nishi and Lin, 2005; Nishi et al., 2008; Shirayama et al., 2006; Stitzel et al., 2006). MEI-1 is the homolog of katanin p60, a microtubule-severing protein essential for meiosis but toxic during mitosis (Bowerman and Kurz, 2006). Phosphorylation by MBK-2 triggers MEI-1 degradation at meiotic exit, allowing formation of the first mitotic spindle without interference from MEI-1 (Lu and Mains, 2007; Stitzel et al., 2006). OMA-1, and its redundant partner OMA-2, are required for maturation of the oocyte and for transcriptional silencing in the zygote (Detwiler et al., 2001; Guven-Ozkan et al., 2008). This second function depends on phosphorylation by MBK-2, which increases OMA-1 and OMA-2’s affinity for the transcription factor TAF-4, causing it to be retained in the cytoplasm (Guven-Ozkan et al., 2008). Phosphorylation by MBK-2 also primes OMA-1 and OMA-2 for a second phosphorylation event that targets OMA-1 and OMA-2 for degradation during mitosis (Nishi and Lin, 2005; Shirayama et al., 2006). MEX-5 and MEX-6 are two redundant maternal proteins essential for polarization of the zygote (Schubert et al., 2000). Phosphorylation by MBK-2 primes MEX-5 and MEX-6 for subsequent phosphorylation by the polo kinases PLK-1 and PLK-2, which activate the MEX-5/MEX-6 polarity function in zygotes (Nishi et al., 2008). In the absence of MBK-2, oocyte maturation and fertilization occur normally, but the zygote does not polarize (MEX-5 and MEX-6 are not active), does not turn off transcription (OMA-1 and OMA-2 cannot sequester TAF-4) and does not form a normal mitotic spindle (MEI-1 is not degraded) (Pellettieri et al., 2003) (Quintin et al., 2003) (Pang et al., 2004) (Guven-Ozkan et al., 2008; Lu and Mains, 2007). As a result, 100% of embryos derived from mothers homozygous for a deletion in mbk-2 [mbk-2(pk1427)] do not survive embryogenesis (fully penetrant maternal-effect lethality).

Antibodies specific for phosphorylated OMA-1 and MEI-1 have shown that MBK-2 phosphorylates these proteins starting in anaphase of meiosis I, with increasing levels through meiosis II, and peak levels at meiotic exit (Nishi and Lin, 2005; Stitzel et al., 2006). This timing correlates with the progressive relocalization of MBK-2 from the cortex to the cytoplasm starting in anaphase of meiosis I and continuing through meiosis II (Stitzel et al., 2007; Stitzel et al., 2006). Before the meiotic divisions, MBK-2 is maintained at the cortex by the cortical anchor EGG-3 (Maruyama et al., 2007; Stitzel et al., 2007). Starting in anaphase of meiosis I, EGG-3 moves into the cytoplasm on vesicles and is slowly turned over, releasing MBK-2 (Stitzel et al., 2007). This process depends on CDK-1, the MPF kinase required in maturing oocytes for entry into meiotic M phase, and on APC/C, the anaphase-promoting complex required for the transition from metaphase to anaphase in meiosis I. Loss of CDK-1 or APC maintains EGG-3 and MBK-2 at the cortex and blocks MEI-1 and OMA-1 degradation. Conversely, inactivation of the CDK-1 inhibitor WEE-1 causes premature cytoplasmic relocalization of EGG-3 and MBK-2, and premature degradation of MEI-1 in immature oocytes (Stitzel et al., 2007; Stitzel et al., 2006). These results have suggested that the advancing meiotic cell cycle controls MBK-2 by regulating its access to cytoplasmic substrates via the cortical anchor EGG-3 (Stitzel et al., 2007).

Analysis of the EGG-3 loss of function phenotype, however, has shown that EGG-3 cannot be the only regulator of MBK-2. In the absence of EGG-3, MBK-2 is in the cytoplasm with MEI-1 (and OMA-1/2 and MEX-5/6) throughout oocyte growth and maturation, but phosphorylates MEI-1 only after ovulation during MI (Stitzel et al., 2007). Therefore, other factors must inhibit MBK-2 activity before MI. In this study, we identify three additional MBK-2 regulators: CDK-1, which activates MBK-2 during oocyte maturation, and the pseudo-phosphatases EGG-4 and EGG-5, which inhibit MBK-2 until the meiotic divisions. Our findings demonstrate that, although self-activating in vitro, in vivo DYRKs are subject to both positive and negative regulation.

Results

CDK-1 is required for MBK-2 activity in vivo

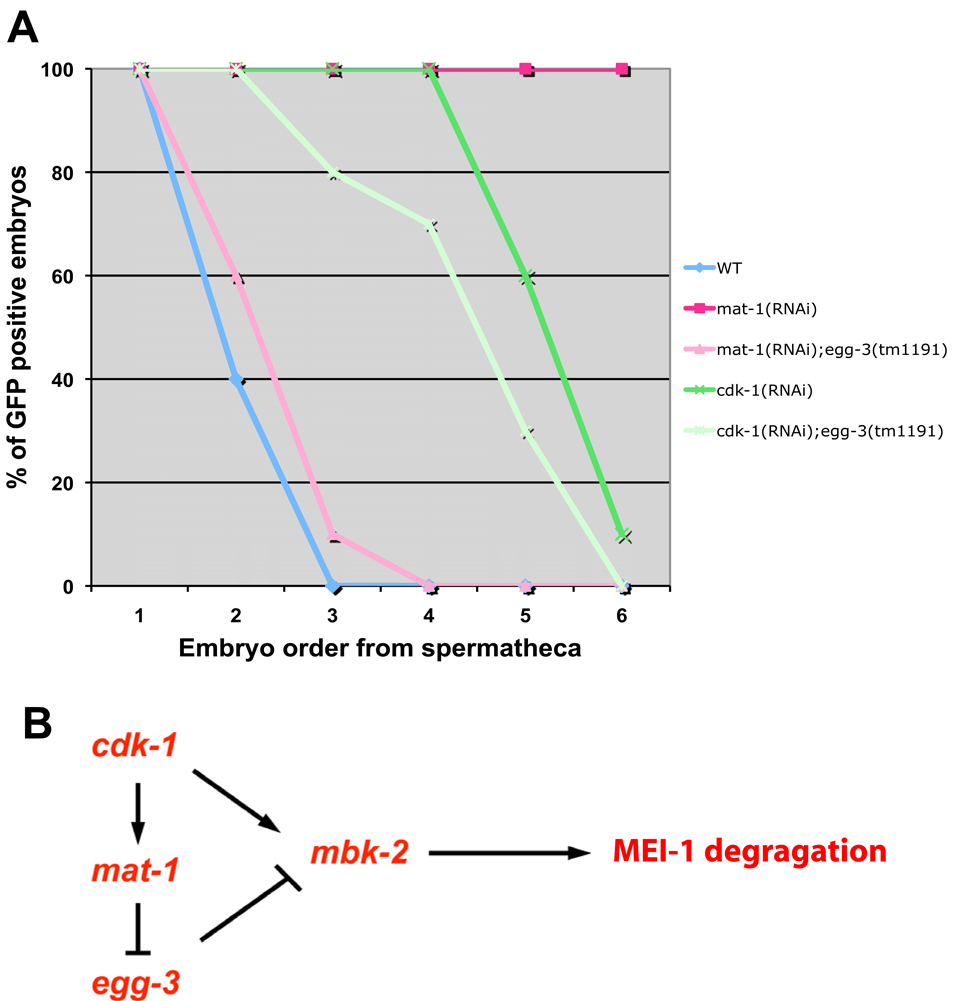

Hermaphrodites lacking cdk-1 or the APC subunit mat-1 keep MBK-2 at the cortex and delay MEI-1 degradation. Loss of the cortical anchor EGG-3 in mat-1 mutants releases MBK-2 in the cytoplasm and restores rapid MEI-1 degradation, indicating that APC’s primary role in this process is to antagonize EGG-3, likely by stimulating its degradation (Stitzel et al., 2007). To determine whether the requirement for CDK-1 also depends on EGG-3, we compared GFP:MEI-1 degradation in cdk-1(RNAi) and cdk-1(RNAi);egg-3(tm1191) hermaphrodites. GFP:MEI-1 degradation was delayed to a similar extent in both genetic backgrounds (Fig. 1A). We conclude that the requirement for CDK-1 does not depend on EGG-3, suggesting that CDK-1, unlike APC, promotes MBK-2 activity directly (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1. CDK-1 is required for MEI-1 degradation and this requirement cannot be suppressed by loss of EGG-3.

(A) Embryos in uteri of hermaphrodites of indicated genotypes were scored for GFP:MEI-1 and for position with respect to the spermatheca [from youngest (position 1) to oldest (position 6)]. In mat-1(RNAi), GFP:MEI-1 is maintained in all embryos, but degradation is restored if egg-3 is also absent. In cdk-1(RNAi), GFP:MEI-1 is maintained past the third position embryo, and this “delayed degradation” pattern is not changed significantly in the absence of egg-3. Unlike mat-1(RNAi), which efficiently maintains MBK-2 at the cortex, cdk-1(RNAi) leads to a more pleiotropic arrest with embryos eventually releasing MBK-2 into the cytoplasm, which may explain why GFP:MEI-1 is eventually degraded in cdk-1(RNAi).

(B) A genetic model describing the epistasis results obtained in A. cdk-1 is required to initiate meiotic M phase (Burrows et al., 2006), and therefore is considered formally here as an “activator” of the APC subunit mat-1.

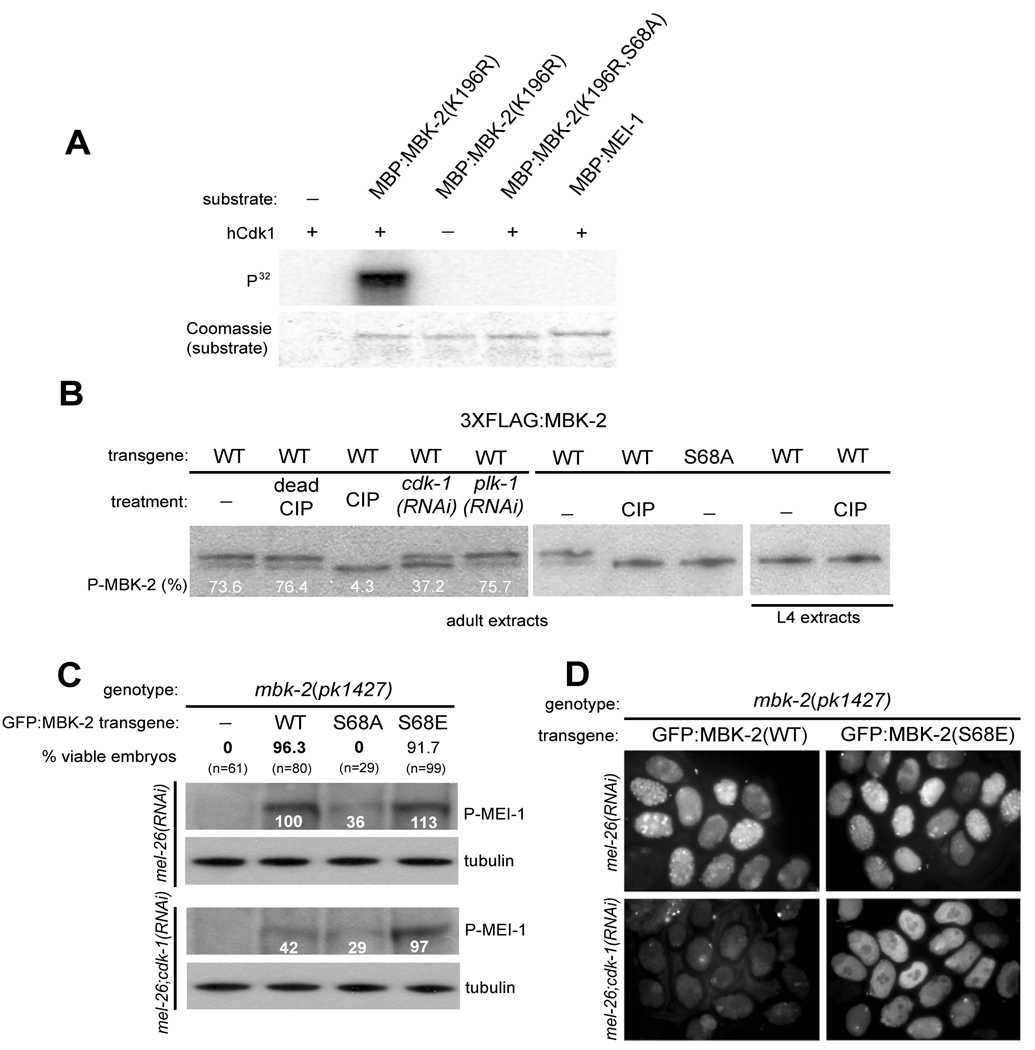

Human Cdk1 phosphorylates MBK-2 on S68 in vitro

To determine whether CDK-1 phosphorylates MBK-2, we performed a kinase assay using a commercial preparation of human Cdk1 and a MBP (maltose binding protein)-MBK-2 fusion synthesized in E. coli. To prevent auto-phosphorylation, we used a MBK-2 mutant lacking a critical residue in the ATP-binding domain [MBK-2(K196R) (Stitzel et al., 2006)]. hCdk1 could phosphorylate MBP:MBK-2(K196R), but not MBP:MEI-1 (Fig. 2A). Cyclin-dependent kinases are proline-directed serine/threonine kinases (see Discussion). The MBK-2 sequence contains two S/TP sites (S68 and T470) (Sup. Fig. 1). Alanine substitution of S68, but not of T470, eliminated phosphorylation by Cdk1 (Fig. 2A and data not shown). We conclude that MBK-2 is a substrate for hCdk1 in vitro and that S68 is the primary site of phosphorylation by hCdk1.

Fig. 2. MBK-2 is activated by CDK-1.

(A) hCdk1 phosphorylates MBK-2.

hCdk1 (New England Biolabs) was incubated with the indicated maltose-binding fusions (partially purified from E. coli) in the presence of γ-32P-ATP. Coomassie staining controls for loading of MBP fusions. We estimate that 43% of MBP:MBK-2 was phosphorylated in this assay. MBK-2(K196R) is a mutation in the ATP binding domain of MBK-2 (Sup. Fig. 1) that eliminates MBK-2’s own kinase activity (Stitzel et al., 2006).

(B) FLAG-tagged MBK-2 was immunoprecipitated from adults (hermaphrodites with 4 or more embryos) or L4 (late L4/early adults with 0–1 embryo in uterus) whole worm extracts, treated with Calf Intestinal Alkaline Phosphatase (CIP), and western blotted with anti-FLAG antibody. Numbers represent the percent of phosphorylated FLAG:MBK-2 compared to total FLAG:MBK-2.

(C) mbk-2(pk1427) hermaphrodites transformed with the indicated transgenes were 1) tested for rescue of maternal-effect lethality (% viable embryos, N= number of embryos scored) and 2) western blotted for phospho-MEI-1. Numbers underneath the phospho-MEI-1 bands indicate relative intensity with respect to that observed in mbk-2(pk1427) hermaphrodites expressing wild-type MBK-2 (set to 100%). mel-26(RNAi) is used to stabilize phospho-MEI-1. Note that cdk-1(RNAi) reduces the level of phospho-MEI-1 significantly only in hermaphrodites carrying the wild-type transgene (100 vs 42).

(D) Immunofluorescence using the anti-phospho-MEI-1 antibody on embryos derived from hermaphrodites of indicated genotype. Note that cdk-1(RNAi) eliminates staining in embryos from mothers expressing the wild-type MBK-2 transgene, but not from mothers expressing the MBK-2(S68E) transgene.

MBK-2 is phosphorylated in a CDK-1-dependent manner in vivo

To determine whether MBK-2 is phosphorylated in vivo, we examined the mobility of FLAG-tagged MBK-2 expressed in oocytes and embryos (Methods). FLAG:MBK-2 migrated as a doublet (Fig. 2B, lane 1). A truncated version of MBK-2 containing Serine 68, but lacking the kinase domain [GFP:MBK-2(1–109)], also exhibited a retarded isoform (Sup. Fig. 2). The slower migrating band accounted for most of the protein (73.6%), was sensitive to CIP treatment, and was not detected in FLAG:MBK-2(S68A), consistent with a phosphorylated isoform (Fig. 2B). Partial depletion of cdk-1 by RNAi significantly reduced the levels of the MBK-2 phospho-isoform (Fig. 2B, lane 4). Depletion of another cell cycle kinase PLK-1 had no effect (Fig. 2B, lane 5). CDK-1 becomes activated at the onset of the oocyte-to-embryo transition (Burrows et al., 2006). Consistent with this, phosphorylated MBK-2 was present in extracts from gravid adult hermaphrodites, which contain both oocytes and embryos, but was not detected in extracts from late L4/young adult hermaphrodites, which contain only oocytes and very few embryos (Fig. 2B). We conclude that MBK-2 is phosphorylated in vivo, possibly by CDK-1 or by another kinase dependent on CDK-1 for activity.

S68 is required for MBK-2 activity in vivo

To examine the function of S68 in vivo, we compared the ability of GFP:MBK-2, GFP:MBK-2(S68A), GFP:MBK-2(S68E) (a predicted phospho-mimic) to rescue the mbk-2 null mutant pk1427. Although all three GFP fusions were expressed and localized similarly (Sup. Fig. 3), only wild-type GFP:MBK-2 and GFP:MBK-2(S68E) rescued the embryonic lethality of pk1427 (Fig. 2C). To investigate whether the three fusions differ in their ability to phosphorylate MEI-1, we probed extracts from each strain with an antibody specific for phosphorylated MEI-1 (P-MEI-1) (Stitzel et al., 2006) . mel-26(RNAi) was used to stabilize P-MEI-1 (Stitzel et al., 2006). We detected high levels of P-MEI-1 in extracts from hermaphrodites expressing GFP:MBK-2(S68E) and GFP:MBK-2 transgenes, low (but above background) levels in extracts from hermaphrodites expressing GFP:MBK-2(S68A), and no P-MEI-1 hermaphrodites expressing no transgene (Fig. 2C). We conclude that phosphorylation of S68 stimulates MBK-2’s ability to phosphorylate MEI-1 in vivo.

If CDK-1 activates MBK-2 via phosphorylation at S68, loss of CDK-1 should reduce MEI-1 phosphorylation levels in the presence of wild-type MBK-2 but not in the presence of MBK-2 mutated at S68. As predicted, we found that depletion of CDK-1 by RNAi reduced P-MEI-1 in extracts from hermaphrodites expressing GFP:MBK-2, but not in extracts from hermaphrodites expressing GFP:MBK-2(S68A) or GFP:MBK-2(S68E) (Fig. 2C). This result was confirmed by immunofluorescence staining of embryos (Fig. 2D). The finding that MBK-2(S68E) bypasses the requirement for cdk-1 is strong genetic evidence for S68 being a site for CDK-1-dependent phosphorylation. We conclude that CDK-1-dependent phosphorylation of S68 stimulates MBK-2’s ability to phosphorylate MEI-1.

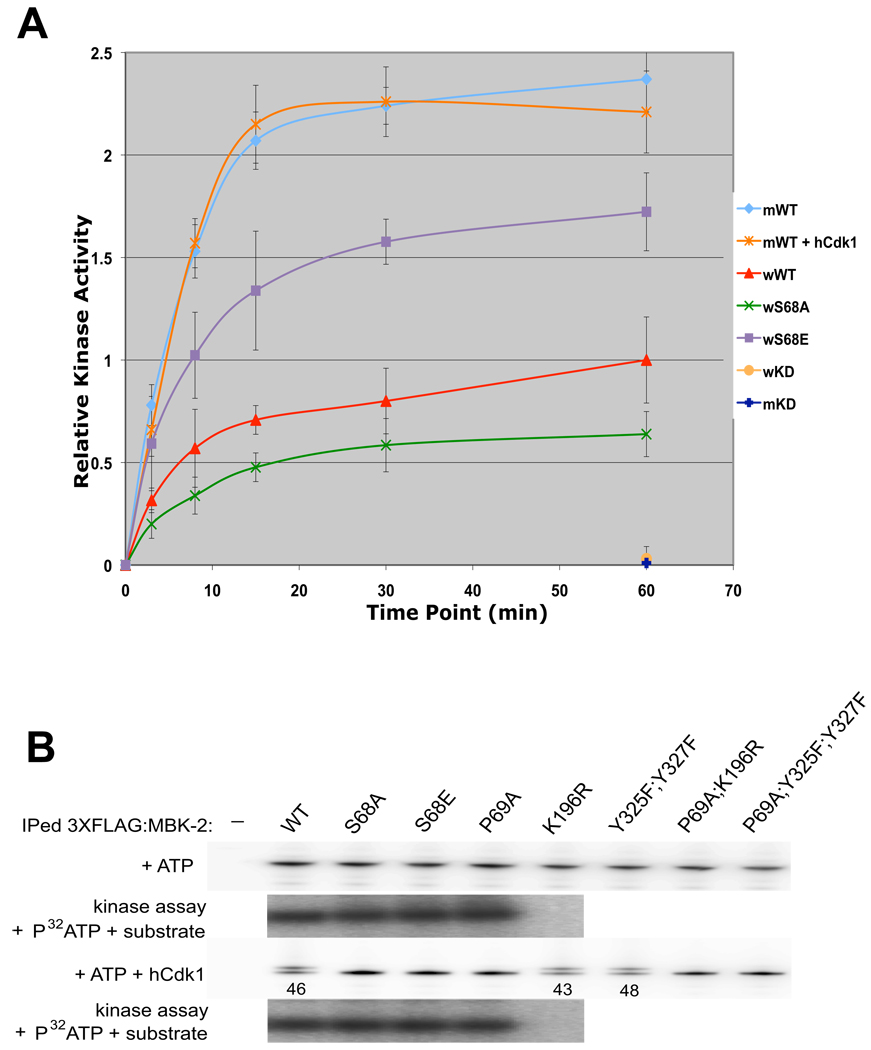

S68 modulates MBK-2 kinase activity in worms, but not in mammalian cells

S68 phosphorylation could stimulate MBK-2’s intrinsic kinase activity or MBK-2’s access to MEI-1. To distinguish between these possibilities, we compared the in vitro kinase activities of GFP:MBK-2, GFP:MBK-2(S68A) and GFP:MBK-2(S68E) immunoprecipitated from worm extracts. We found that the fusions showed three different activity levels: low (S68A), intermediate (WT), and high (S68E) (Fig. 3A). We conclude that S68 modulates MBK-2’s intrinsic kinase activity.

Fig. 3. S68 is required for full kinase activity of MBK-2 synthesized in oocytes, but not of MBK-2 synthesized in mammalian cells.

(A) MBK-2 fusions immunoprecipitated from whole worm extracts (w), or from mammalian cells (m), were treated or not treated with hCdk1, and incubated with recombinant MEI-1(a.a. 51–150) and γ-32P-ATP in kinase buffer for the time shown. Relative kinase activity was calculated by measuring 32P incorporation in MEI-1 expressed as a ratio over the signal obtained for wild-type worm MBK-2 at 60 min. Error bars represent standard deviation from 3 independent immunoprecipitation experiments.

(B) FLAG:MBK-2 fusions immunoprecipitated from mammalian cells were incubated with cold ATP and with or without hCdk1. Half of the samples were run on SDS page (note the presence of slower isoforms in lanes 1, 5 and 6) and the other half was used in a kinase assay again recombinant MEI-1(a.a. 51–150) [no change in kinase activity was detected except in K196R which is not active, as expected (Stitzel et al., 2007)]. Numbers (%) represent the relative amount of phosphorylated FLAG:MBK-2 with respect to total FLAG:MBK-2.

To determine whether S68 affects MBK-2 kinase activity directly, we asked whether MBK-2 expressed in mammalian cells also requires S68 and/or phosphorylation for full activity. FLAG:MBK-2 immunoprecipitated from HEK293 cell extracts migrates as a single isoform (Fig. 3B). Addition of ATP and hCdk1 to the immunoprecipitates caused the appearance of a slower isoform, similar to what is seen for FLAG:MBK-2 in worms (Compare Fig. 3B to Fig. 2B). Appearance of the slower isoform requires S68 and P69, but does not require MBK-2’s own kinase activity. Remarkably, we detected no difference in kinase activity among wild-type MBK-2 and the S68 and P69 mutants treated or not treated with hCdk-1 (Fig. 3A and B). We repeated these experiments with MBK-2 made as an MBP fusion in E. coli and again saw no difference between wild-type and the S68 mutants (Sup. Fig. 4). We conclude that phosphorylation of S68 does not affect kinase activity directly, but may affect it indirectly by opposing negative regulators or modifications associated with MBK-2 in worms (see Discussion). Consistent with this hypothesis, FLAG:MBK-2 immunoprecipitated from mammalian cells was 2.5X more active than GFP:MBK-2 immunoprecipitated from worms (Fig. 3A).

EGG-4/5 negatively regulates MBK-2 activity in maturing oocytes

Phosphorylation of the CDK-1 target Histone H3 has been detected in the last 2–3 oocytes, with highest levels in the oocyte nearest the spermatheca (“proximal” oocytes that have initiated maturation and are transitioning to meiotic M phase) (Burrows et al., 2006). If CDK-1 phosphorylates and activates MBK-2 with similar timing, P-MEI-1 should be present in proximal oocytes. Instead, we detect P-MEI-1 only after ovulation, in zygotes in anaphase of meiosis I (Stitzel et al., 2006). We showed previously that this timing depends in part on the cortical anchor EGG-3, which tethers MBK-2 at the cortex until anaphase I (Stitzel et al., 2007). In egg-3 mutants, P-MEI-1 appears precociously during metaphase I, but remains off in oocytes, suggesting the existence of other negative regulators (Stitzel et al., 2007). EGG-4 (T21E3.1) and EGG-5 (R12E2.10) are two oocyte proteins that like EGG-3 are required for egg activation and MBK-2 localization to the cortex (J. Parry and A. Singson, in preparation). Single deletions in egg-4 or egg-5 cause low penetrance egg lethality, but co-depletion of egg-4 and egg-5 using RNAi causes 100% lethality and causes GFP:MBK-2 to become cytoplasmic in oocytes as is observed in egg-3(RNAi) (J. Parry and A. Singson, in preparation). Consistent with functioning redundantly, egg-4 and egg-5 encode two 753-amino acid proteins that differ only by 6 amino acids (99.2% identical, Sup. Fig. 5). Like EGG-3 (Maruyama et al., 2007), EGG-4 and EGG-5 contain a predicted protein tyrosine phosphatase (PTP) domain with substitutions in active site residues (Sup. Fig. 5). “PTP-like” proteins are predicted to lack phosphatase activity, but may retain the ability to bind phosphorylated tyrosines (Hunter, 1998; Wishart and Dixon, 1998).

To investigate whether EGG-4/5 regulate MBK-2 activity, we examined the distribution of P-MEI-1 in hermaphrodites depleted for EGG-4/5 by RNAi. mel-26(RNAi) was used to stabilize P-MEI-1 (Stitzel et al., 2006). As seen in egg-3 mutants, P-MEI-1 was present in all egg-4(RNAi);egg-5(RNAi) zygotes including those in metaphase of meiosis I (Sup. Fig. 6). In addition, in 13.8% of egg-4(RNAi);egg-5(RNAi) gonads (Sup. Table 1), we detected P-MEI-1 in the two most proximal oocytes (Fig. 4A). This pattern and the low frequency suggest that MBK-2 activity in egg-4/5(RNAi) depends on oocyte maturation and activation of MBK-2 by CDK-1. If so, P-MEI-1-positive gonads should increase in egg-4/5(RNAi) hermaphrodites expressing GFP:MBK-2(S68E). As predicted, we found that 100% of egg-4/5(RNAi); GFP:MBK-2(S68E) gonads were positive for P-MEI-1 (Sup. Table 1). Furthermore, in 75% of these gonads, the pattern of P-MEI-1 was expanded to 3 or more oocytes (Fig. 4A). We also observed a (more modest) increase in P-MEI-1 in egg-4/5(RNAi) hermaphrodites expressing wild-type GFP:MBK-2 in addition to endogenous MBK-2 (Fig. 4A and Sup. Table 1). Appearance of P-MEI-1 in oocytes was strictly dependent on egg-4/5(RNAi) and on S68. No P-MEI-1 was observed in wild-type, egg-3(tm1191) or egg-3(RNAi) hermaphrodites expressing GFP:MBK-2 or GFP:MBK-2(S68E), or mbk-2(pk1427); egg-4/5(RNAi) hermaphrodites expressing GFP:MBK-2(S68A) (Fig. 4A and Sup. Table 1). We conclude that EGG-4/5 are required to inhibit CDK-1-activated MBK-2 during oocyte maturation.

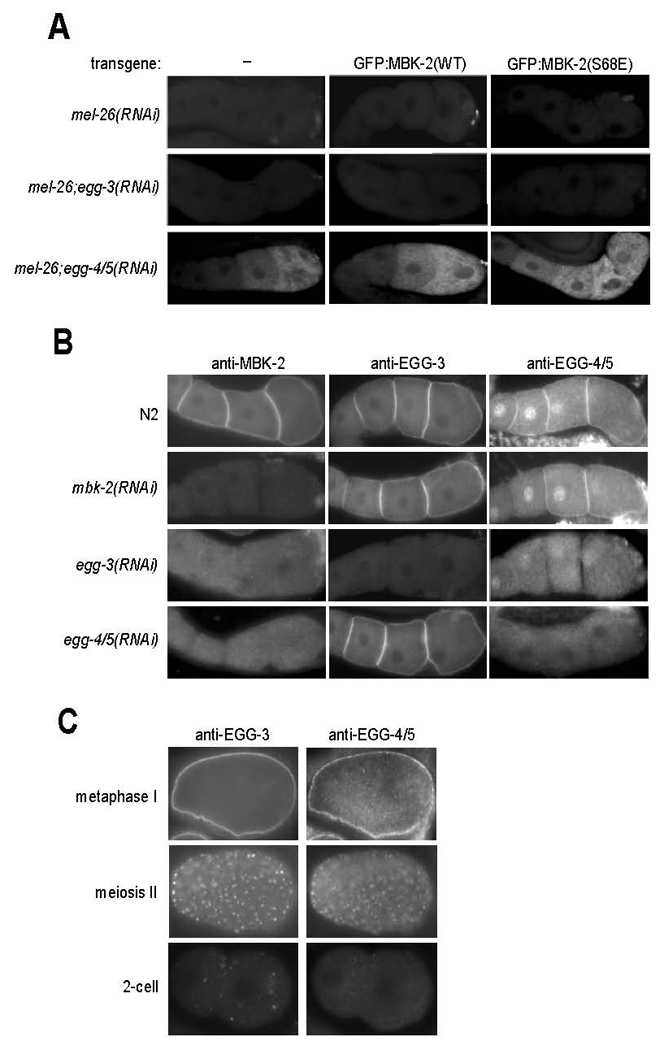

Fig. 4. EGG-4 and EGG-5 inhibit MBK-2 in oocytes and localize to the oocyte cortex.

A. Gonads from hermaphrodites with indicated genotypes were fixed and stained with anti-P-MEI-1 antibody. mel-26(RNAi) is used to stabilize P-MEI-1. Note that 1) P-MEI-1 is only seen when EGG-4 and EGG-5 are inactivated by RNAi, and 2) the pattern of P-MEI-1 correlates with oocyte maturation in gonads expressing wild-type MBK-2, and is expanded in gonads expressing MBK-2(S68E). See Sup. Table 1 for numbers and additional genotypes examined.

B. Gonads were stained with anti-MBK-2, anti-EGG-3 and anti-EGG-4/5 antibodies. Note that EGG-4/5 are detected both on the cortex and nuclei of oocytes. The patterns seen after the indicated RNAi treatments suggest that the cortical localization of 1) EGG-3 does not require EGG-4/5 or MBK-2, 2) EGG-4/5 requires EGG-3, but not MBK-2, and 2) MBK-2 requires EGG-3 and EGG-4/5.

C. Embryos co-stained with anti-EGG-3 and anti-EGG-4/5 antibodies. EGG-3 and EGG-4/5 re-localize from the cortex to sub-cortical speckles during the transition from meiosis I to meiosis II. In the 2-cell stage, occasional EGG-3-positive speckles can still be detected. By this stage, the EGG-4 signal is at background levels.

EGG-4/5 are enriched on the cortex of oocytes

To determine the distribution of EGG-4 and EGG-5, we generated a polyclonal antibody against EGG-4 and EGG-5 (Experimental Procedures). We confirmed that the antibody recognizes both proteins by western blotting of E. coli expressed EGG-4 and EGG-5 (data not shown). Like EGG-3 and MBK-2, EGG-4/5 localize to the cortex of oocytes (Fig. 4B). In addition, EGG-4/5 were also detected in oocyte nuclei. The cortical and nuclear signals were eliminated by RNAi co-depletion of EGG-4 and EGG-5, confirming that they correspond to endogenous EGG-4/5. Staining of hermaphrodites homozygous for single deletions in either EGG-4 or EGG-5 gave the same pattern as wild-type, confirming that EGG-4 and EGG-5 are both expressed in oocytes (data not shown). In zygotes in meiosis II, EGG-4/5 was enriched on sub-cortical puncta, also positive for EGG-3 (Fig. 4C). EGG-3-positive puncta invade the cytoplasm during meiosis II (Stitzel et al., 2007). EGG-4/5 puncta, in contrast, were prominent only near the cortex and around the sperm pronucleus (Sup. Fig. 6). No EGG-4/5 was detected above background in 2-cell embryos (Fig. 4C).

To examine the relationships among EGG-4/5, EGG-3 and MBK-2 localizations in vivo, we stained wild-type, egg-3(RNAi), egg-4/5(RNAi) and mbk-2(RNAi) hermaphrodites with the EGG-4/5 antibody and antibodies against EGG-3 and MBK-2 (Stitzel et al., 2007). We found that, in oocytes, 1) MBK-2 requires both EGG-3 and EGG-4/5 for cortical localization, 2) EGG-4/5 require EGG-3, but not MBK-2, and 3) EGG-3 does not require MBK-2 or EGG-4/5 (Fig. 4B). These observations are consistent with our earlier finding that EGG-3, although required for MBK-2 cortical localization, is not sufficient on its own to target MBK-2 to the cortex (Stitzel et al., 2007). In egg-3 mutants, EGG-4/5 and MBK-2 are cytoplasmic (Fig. 4B), yet MBK-2 remains inhibited in oocytes (Fig. 4A). This observation indicates that inhibition of MBK-2 by EGG-4/5 does not require EGG-3 or cortical localization, raising the possibility that EGG-4/5 inhibit MBK-2 directly.

MBK-2 binds directly to EGG-4/5 and this interaction depends on the MBK-2 activation loop

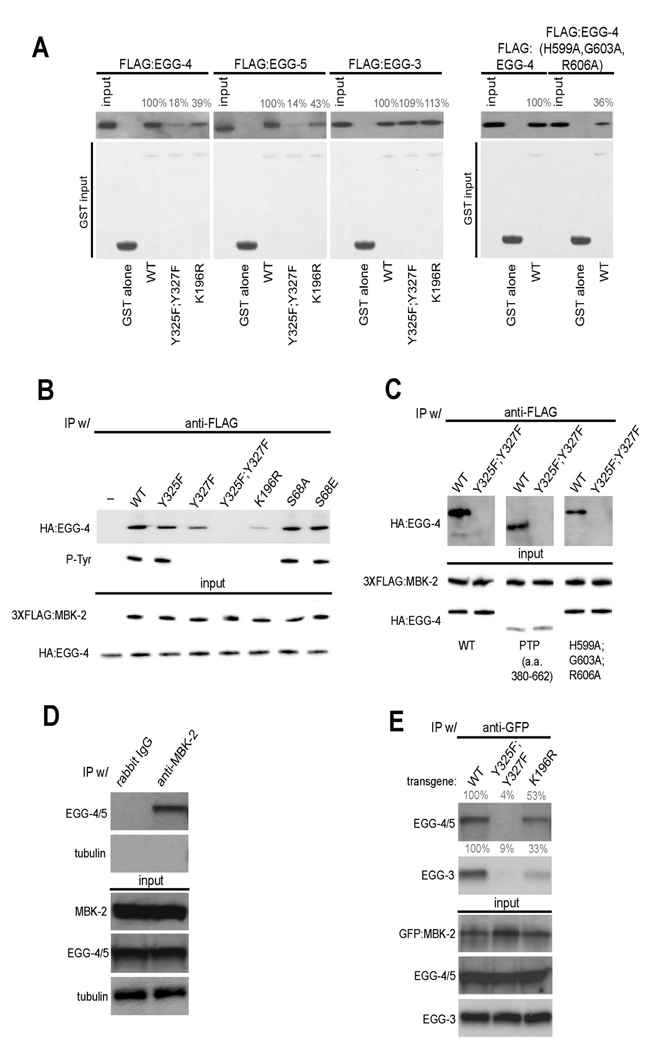

MBK-2 and EGG-3 bind directly in vitro (Stitzel et al., 2007). To test whether MBK-2 also binds to EGG-4 and EGG-5, we expressed each separately as GST and FLAG fusion proteins in E. coli. GST:MBK-2-coupled beads could pull down FLAG:EGG-4 and FLAG:EGG-5 (and FLAG:EGG-3) from E. coli extracts (Fig. 5A). Mutations in the pseudo-phosphatase active sites of EGG-4 and EGG-3 reduced binding (Fig. 5A and Sup. Fig. 7). Mutation in the ATP-binding site (K196R) similarly reduced binding to EGG-4/5, but not to EGG-3 (Fig. 5A). Mutations in the two tyrosines in the MBK-2 activation loop (Y325F, Y327F) severely reduced binding to EGG-4 and EGG-5, but not to EGG-3. Further analyses revealed that unlike EGG-4 and EGG-5, EGG-3 binds to the amino-terminus of MBK-2 (Sup. Fig. 7).

Fig. 5. EGG-4/5 interact with MBK-2 in vivo and in vitro.

(A) EGG-4/5 bind to MBK-2 in vitro. Extracts from E. coli expressing the indicated FLAG:EGG fusions were pulled down with the indicated GST:MBK-2 fusions and immunoblotted with an anti-FLAG antibody. Numbers (%) indicate signal intensity relative to wild-type. Input is 1/50th of the pull-down. EGG-4(H599A,G603A, R606A) has mutations in consensus residues in the predicted phosphatase catalytic site (see Sup. Fig. 5).

(B) EGG-4 interacts with MBK-2 in mammalian cells. HA-tagged EGG-4 and FLAG-tagged MBK-2 were co-expressed in HEK293 cells, immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG, and probed with an anti-phosphotyrosine antibody and an anti-HA antibody. Input is 1/100 of the IP.

(C) EGG-4 uses its protein tyrosine phosphatase (PTP) domain to interact with MBK-2. HA and FLAG tagged proteins were co-expressed and immunoprecipitated as in (B). EGG-4(380–662) is the PTP domain (see Sup. Fig. 5). Input is 1/100 of the IP.

(D) EGG-4/5 and MBK-2 interact in worm extracts. Anti-MBK-2 immunoprecipitates from whole worm extracts were western blotted with anti-EGG-4/5 antibody and anti-tubulin antibody (negative control). Input is 1/100th of the IP. Rabbit IgG is a negative control antibody.

(E) The EGG-4/5/MBK-2 interaction requires the MBK-2 activation loop in vivo. Anti-GFP immunoprecipitates from whole worm extracts were western blotted with anti-EGG-4/5 and anti-EGG-3 antibodies. Anti-GFP pulls down endogenous EGG-4/5 and EGG-3 from worms expressing wild-type GFP:MBK-2 or GFP:MBK-2(K196R) (kinase dead), but not from worms expressing GFP:MBK-2(Y325F,Y327F) (activation loop mutant). Numbers (%) indicate signal intensity relative to wild-type. Input is 1/100th of the IP.

To further investigate the EGG-4/MBK-2 interaction, we expressed both in HEK293 cells and monitored, in parallel, binding and MBK-2 tyrosine phosphorylation. We found that tyrosine phosphorylation requires the ATP-binding site (K196) and the second tyrosine in the activation loop (Y327) of MBK-2 (Fig. 5B), as shown previously for Drosophila DYRK2 (Lochhead et al., 2005). Mutants that lack tyrosine phosphorylation but retain at least one tyrosine [K196R and Y327F] bound weakly but still detectably to EGG-4, whereas the double mutant lacking both tyrosines (Y325F, Y327F) showed no detectable binding (Fig. 5B). The EGG-4 phosphatase domain alone was sufficient for binding, and mutations in the pseudo-phosphatase active site reduced but did not eliminate binding (Fig. 5C). We conclude that EGG-4 uses its phosphatase domain to interact with the tyrosines in the activation loop of MBK-2, and that this interaction is enhanced by, but does not absolutely require, tyrosine phosphorylation.

MBK-2 interacts with EGG-4/5 in vivo and this interaction is essential for localization to the oocyte cortex

To determine whether MBK-2 and EGG-4/5 interact in worms, we immunoprecipitated MBK-2 and probed the immunoprecipitate with the EGG-4/5 antibody. We detected EGG-4/5 in MBK-2 immunoprecipitates, but not in the immunoprecipitates of the control rabbit IgG antibody. MBK-2 immunoprecipitates did not contain tubulin, confirming the specificity of the assay (Fig. 5D).

To explore the specificity of the MBK-2/EGG-4/5 interaction further, we used GFP-tagged MBK-2 fusions and an anti-GFP antibody for immunoprecipitation. Wild-type GFP:MBK-2 immunoprecipitated endogenous EGG-4/5 (Fig. 5E). As observed in E. coli and mammalian cells, MBK-2(K196R) bound EGG-4/5 with reduced affinity, and MBK-2(Y325F, Y327F) bound even more poorly, if at all (Fig. 5E). In oocytes, GFP:MBK-2(K196R) localizes to the cortex as does wild-type MBK-2, whereas GFP:MBK-2(Y325F, Y327F) remains cytoplasmic (Sup. Fig. 3). We conclude that 1) MBK-2 and EGG-4/5 interact in vivo, 2) the MBK-2/EGG-4/5 interaction requires the activation loop tyrosines, and only partially depends on tyrosine phosphorylation (confirming the in vitro findings) and 3) the MBK-2/EGG-4/5 interaction is essential for localizing MBK-2 to the cortex.

GFP:MBK-2(K196R) and GFP:MBK-2(Y325F, Y327F) also bound poorly to EGG-3 in worm extracts (Fig. 5E), in contrast to what we observed with partially purified proteins in vitro (Fig. 5A). This observation suggests that, in oocytes, the MBK-2/EGG-3 interaction depends on MBK-2 binding to EGG-4/5. This hypothesis is consistent with the fact that EGG-3 is not sufficient to localize MBK-2 to the cortex in the absence of EGG-4/5 (Fig. 4B).

EGG-4 inhibits MBK-2 activity in vitro

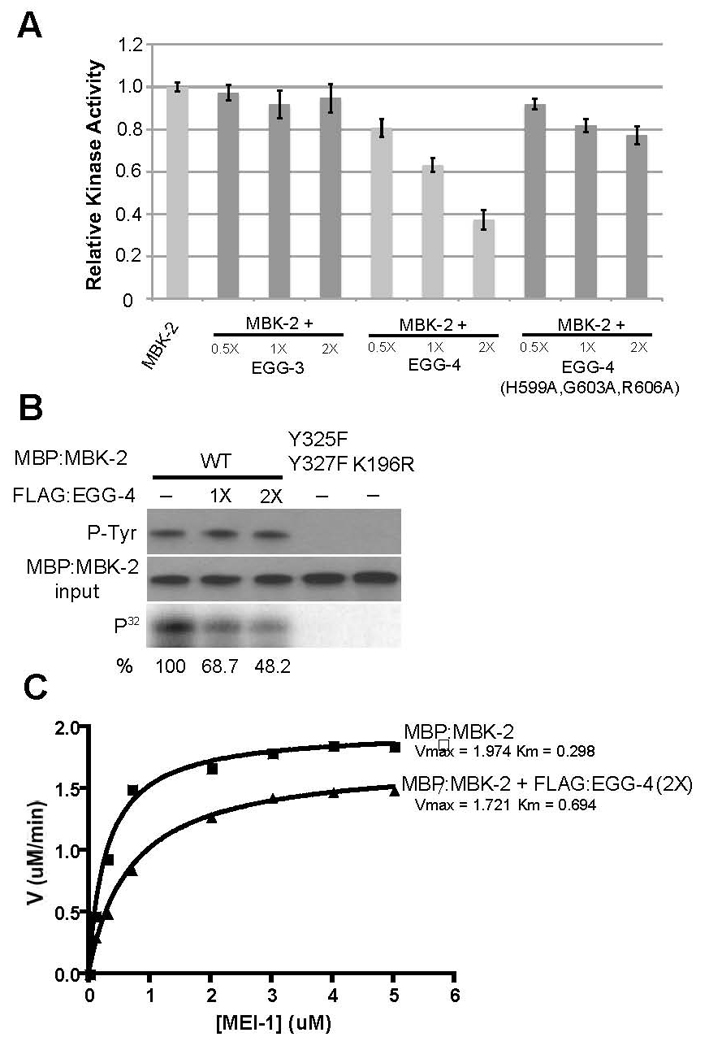

To test whether EGG-4 or EGG-3 inhibit MBK-2 activity directly, we performed an in vitro MBK-2 kinase assay in the presence of EGG-4 or EGG-3, partially purified as FLAG fusions from E. coli. We found that EGG-4 reduces MBK-2’s ability to phosphorylate the MEI-1 fragment MEI-1(51–150) in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 6A and Sup. Fig. 8). The effect was specific to EGG-4, as we observed no significant inhibition in the presence of EGG-3 (Fig. 6A and Sup. Fig. 8). Mutations in the pseudo-phosphatase active site reduced the strength of inhibition (Fig. 6A and Sup. Fig. 8). We conclude that EGG-4 inhibits MBK-2 activity directly and that this inhibition requires the phosphatase domain of EGG-4.

Fig. 6. EGG-4 inhibits MBK-2 kinase activity in vitro.

A. 0.5, 1 and 2-fold molar excess of FLAG-tagged EGG-3, EGG-4 and EGG-4(H599A,G603A, R606A) were added to MBP:MBK-2 kinase reactions and the amount of phosphorylated MEI-1 was quantified (as in Fig. 3) after 30 minutes. Levels are expressed as ratio to that observed with MBP:MBK-2 alone (first lane).

B. Same as A, but kinase reactions were split to examine amount of tyrosine-phosphorylated MBK-2 (P-Tyr), amount of MBP:MBK-2 and amount of phosphorylated MEI-1 (P32). Note that addition of EGG-4 lowers the amount of phosphorylated MEI-1 but does not affect tyrosine phosphorylation of MBK-2.

C. Michaelis-Menten plot to compare MBK-2 enzyme kinetics in the presence (2X molar excess) or absence of FLAG:EGG-4.

EGG-4 is not predicted to possess tyrosine phosphatase activity because of its non-canonical phosphatase active site (Sup. Fig. 4). To verify that EGG-4 does not dephosphorylate MBK-2, we incubated MBP:MBK-2 with EGG-4 and monitored both MBK-2 tyrosine phosphorylation and kinase activity in parallel. As expected, we observed a reduction in kinase activity, but observed no change in tyrosine phosphorylation (Fig. 6B). We conclude that EGG-4 inhibition of MBK-2 does not involve dephosphorylation of the activation loop.

Next, we compared the kinetics of MBK-2 kinase activity with and without EGG-4, and in the presence of varying amount of the substrate MEI-1(51–150). Fig. 6C shows that EGG-4 affects the Km (substrate concentration at which V= Vmax/2) and, to some extent, also the Vmax (reaction maximal velocity) of the MBK-2 kinase reaction. These results suggest that EGG-4 may function as a mixed-type inhibitor, i.e. EGG-4 interferes with substrate binding (increases the Km) and with turn-over rate (lowers the Vmax) (Berg et al., 2006).

Discussion

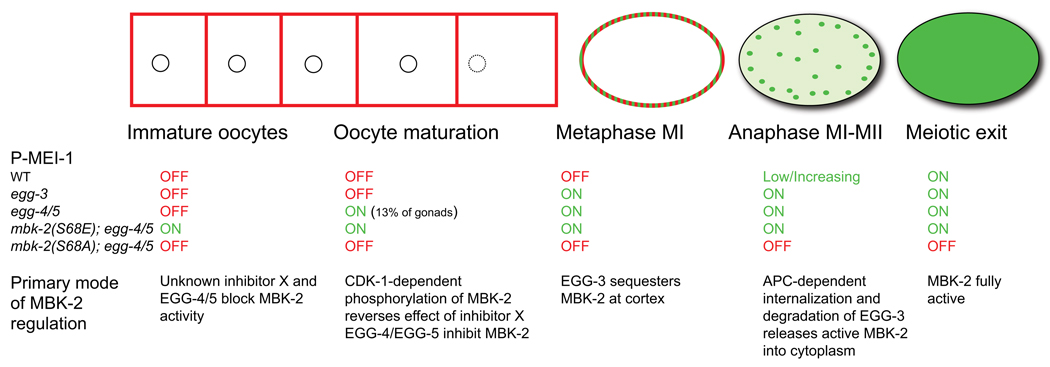

We have investigated the mechanisms that regulate MBK-2 kinase activity during the oocyte-to-zygote transition and have identified three modes of regulation: activation by CDK-1-dependent phosphorylation, inhibition by EGG-4/5, and cortical anchoring (Fig. 7). We discuss each of these in turn.

Fig. 7. Working model for MBK-2 regulation during the oocyte-to-embryo transition.

Red and green colors indicate the distribution of MBK-2 during the oocyte-to-embryo transition. MBK-2 goes from cortically-enriched to cytoplasmic during the transition (Stitzel et al., 2006) and from inactive (red) to active (green). Under each stage, we indicate 1) the pattern of P-MEI-1 observed in wild-type and in the indicated genotypes, and 2) the proposed primary mode of MBK-2 regulation for that stage.

Activation by CDK-1

The MPF kinase CDK-1 drives oocyte maturation and the meiotic divisions in all animals (Voronina and Wessel, 2003). Our results suggest that, in parallel to its cell cycle role, CDK-1 also activates MBK-2. cdk-1 is required for mbk-2 activity in vivo and promotes phosphorylation of S68 in vivo and in vitro. MBK-2(S68A) has low kinase activity; in contrast, MBK-2(S68E) has high kinase activity and bypasses the requirement for cdk-1. We conclude that phosphorylation of S68 is required for MBK-2 activation in vivo, and suggest that CDK-1 may be the kinase responsible.

The preferred consensus for Cdk1-Cyclin B in mammalian cells is a target serine or threonine, followed immediately by a proline, and an arginine or lysine residue in the +3 position ([ST]Px[KR]) (Holmes and Solomon, 1996; Songyang et al., 1994). S68 is followed by a proline, but does not have an arginine or lysine in the +3 position. A recent study reported that 39% of direct Cdk1-Cyclin B targets in HeLa cells also contain only the minimal [ST]P site (Blethrow et al., 2008). Although our data are consistent with direct phosphorylation of S68 by CDK-1, we do not exclude the possibility that a CDK-1-dependent kinase, rather than CDK-1 itself, is involved.

What is the mechanism by which phosphorylation of S68 activates MBK-2? MBK-2 synthesized in mammalian cells or in E. coli does not require S68 or CDK-1 phosphorylation for full activity, suggesting that S68 phosphorylation regulates MBK-2 indirectly, by opposing the effects of negative regulators present in oocytes. One possibility is that upon synthesis in early oogenesis, MBK-2 enters an inhibitory complex or acquires an inhibitory modification, the effect of which is reversed during oocyte maturation by phosphorylation of S68. We have identified EGG-4 and EGG-5 as inhibitors of MBK-2 during oogenesis (see below) but EGG-4/5 are unlikely to be the inhibitors opposed specifically by CDK-1 for the following reasons: 1) in the absence of EGG-4/5, MBK-2 still requires oocyte maturation and S68 to become active, 2) EGG-4/5 inhibit MBK-2(S68E) in oocytes (Sup. Table 1), and 3) MBK-2, MBK-2(S68A) and MBK-2(S68E) all bind EGG-4/5 in vivo with similar affinities (Sup. Fig. 3B). Instead, our results suggest that there is another, yet-to-be-discovered mechanism, which functions redundantly with EGG-4/5 to inhibit MBK-2 before oocyte maturation (Fig. 7).

Cell cycle-dependent upregulation of kinase activity has also been reported for Pom1p, the Schizosaccharomyces pombe DYRK homolog (Bahler and Nurse, 2001). Pom1p kinase activity is upregulated 10 or more fold after S phase, by an unknown mechanism (Bahler and Nurse, 2001). Pom1p has a long N-terminal extension, which includes a serine/threonine-rich domain (Bahler and Pringle, 1998). Deletion of the N-terminal extension disrupts Pom1p localization in vivo, but does not eliminate Pom1p kinase activity, consistent with a regulatory role. Human and Drosophila DYRK2s also contain a serine/threonine-rich region upstream of the kinase domain (Sup. Fig. 1). We suggest that the N-terminus of DYRKs may generally serve as a docking site for cellular proteins that sequester and/or inactivate DYRKs. Phosphorylation of the N-terminus by serine-threonine kinases that mediate cell cycle or developmental transitions could weaken these interactions, leading to DYRK activation. Regulation by sequestration and phosphorylation has also been proposed for Mirk/Dyrk1B (Lim et al., 2002).

Inhibition by the pseudo-phosphatases EGG-4 and EGG-5

After CDK-1-dependent activation, MBK-2 remains inhibited by the redundant (99% identical) protein tyrosine phosphatase-like (PTPL) proteins EGG-4 and EGG-5. As predicted for a PTPL (Hunter, 1998; Wishart and Dixon, 1998), EGG-4 is unable to dephosphorylate MBK-2, but recognizes the phosphorylated YTY motif in the MBK-2 activation loop. Surprisingly, EGG-4 and EGG-5 binding to MBK-2 is stimulated by, but does not absolutely depend on, tyrosine phosphorylation, suggesting that PTPLs may also recognize unphosphorylated tyrosines.

PTPLs have been proposed to function as “anti-phosphatases” protecting phosphotyrosines from dephosphorylation by “real” PTPs (Hunter, 1998; Wishart and Dixon, 1998). For example, the Arabidopsis PTPL Pasticcino2 I binds to cyclin-dependent kinase CDKA;1 phosphorylated on Tyr15. Phosphorylated CDKA is inactive and is activated by dephosphorylation by the phosphatase CDC25. In pasticcino2 mutants, CDKA;1 is dephosphorylated (presumably by CDC25) and activated (Da Costa et al., 2006). It is highly unlikely that EGG-4 and EGG-5 inhibit MBK-2 by a similar mechanism, since tyrosine-phosphorylated MBK-2 is active, and EGG-4 inhibits MBK-2 in vitro in the absence of any other proteins. For this reason, we prefer to refer to EGG-4 and EGG-5 as pseudo-phosphatases, rather than anti-phosphatases. We do not exclude the possibility, however, that in vivo EGG-4/5 also serve to protect MBK-2 from dephosphorylation. A dual inhibitor/protector role would ensure that maximal MBK-2 activity is delivered to the zygote cytoplasm upon release from the cortex.

Our enzymatic analysis suggests that EGG-4 interferes both with catalysis and substrate binding. Inhibition of kinase activity by a protein that binds to the activation loop has been observed previously (Depetris et al., 2005). The SH2 (Src homology-2) domain protein Grb14 binds to the phospho-tyrosines in the activation loop of the insulin receptor (IR). Binding of the SH2 domain positions an adjacent domain (BPS, between PH and SH2) in the substrate-binding pocket of the IR kinase domain (Depetris et al., 2005). The BPS inhibits kinase activity by acting as a pseudo-substrate (Depetris et al., 2005). EGG-4 contacts the MBK-2 activation loop using a conserved phosphatase domain; we do not know whether this domain could also function as a pseudo-substrate. Another possibility is that EGG-4 binding forces the MBK-2 activation loop, and nearby catalytic loop, into an unfavorable conformation, perhaps one resembling the unphosphorylated state.

To our knowledge, EGG-4/5 are the first PTPLs proposed to function directly as kinase inhibitors. “Mutant” PTP domains, with substitutions predicted to eliminate phosphatase activity, have been identified in all organisms examined to date and in all subclasses of the PTP family (Pils and Schultz, 2004). In the C. elegans genome, 62% of all PTP domains are predicted to be inactive (57 of 91), and in the human genome, 40% are predicted to be inactive (20 of 51) (Pils and Schultz, 2004). The majority have unknown functions. It will be important to determine which PTPLs behave primarily as phosphatase antagonists (“anti-phosphatases”), and which also have autonomous activities as we demonstrate here for EGG-4 and EGG-5.

Cortical anchoring and cell-cycle regulation of the oocyte-to-embryo transition

Binding to EGG-4 and EGG-5 not only inhibits MBK-2 activity, but also sequesters MBK-2 at the cortex away from its cytoplasmic substrates. This localization depends on EGG-3, another PTPL that binds to MBK-2 and is required for both MBK-2 and EGG-4/5 cortical localization (Maruyama et al., 2007; Stitzel et al., 2007). Although EGG-3 binds to MBK-2 directly in vitro (Stitzel et al., 2007), in vivo EGG-3 only recruits MBK-2 to the cortex in the presence of EGG-4 and EGG-5, suggesting that EGG-3 functions as an adaptor linking the EGG-4/5/MBK-2 complex to the cortex. During the meiotic divisions, EGG-3 and EGG-4/5 are internalized on sub-cortical puncta and are eventually degraded. EGG-3 degradation depends on the anaphase-promoting complex and on several destruction boxes present in EGG-3 (Stitzel et al., 2007). EGG-4/5 also require APC for cortical release (K. Cheng, unpublished) and contain 4 putative destruction boxes (RXXL) (Sup. Fig. 5). We suggest that APC-stimulated turnover of EGG-3, EGG-4 and EGG-5 releases CDK-1-activated MBK-2 into the cytoplasm of zygotes in meiosis II. We note that the egg-3 phenotype (premature phosphorylation of MEI-1 in metaphase of Meiosis I but not earlier) and the observation that egg-3 is epistatic to the APC subunit mat-1 (Stitzel et al., 2007) suggest that EGG-3-dependent sequestration becomes the primary mode of MBK-2 regulation by metaphase of meiosis I (Fig. 7). We do not know why EGG-4/5 are no longer sufficient to inhibit MBK-2 at that time. Unlike EGG-3 and MBK-2, EGG-4/5 do not persist on cytoplasmic puncta during internalization in meiosis II (Sup. Fig. 6C), raising the possibility that EGG-4/5 are degraded and/or released from the MBK-2 complex before EGG-3.

Parallel regulation of MBK-2 by CDK-1 and the APC-regulated EGG proteins ensures that MBK-2 activation and release are tightly and irreversibly linked to meiotic progression. Fertilization is not required for MBK-2 activation (Stitzel et al., 2006). Our findings illustrate how one aspect of the oocyte-to-embryo transition (the modification and degradation of oocyte proteins) is triggered cell-autonomously by the advancing meiotic cell cycle. DYRKs in other organisms have also been implicated in cellular transitions that require coordination between cell cycle and cell differentiation (Friedman, 2007). Our analysis of MBK-2 illustrates how cell cycle regulation can be imposed on a DYRK by a combination of positive and negative inputs.

Experimental Procedures

Nematode Strains

C. elegans strains (Sup. Table 2) were derived from the wild-type Bristol strain N2 and reared by standard procedures (Brenner, 1974).

Transgene Construction and Transformation

All transgenes were driven by the pie-1 promoter and 3’UTR for maternal expression (D'Agostino et al., 2006) and transformed by microparticle bombardment (Praitis et al., 2001). GFP:MBK-2 is described in (Pellettieri et al., 2003) and rescues the mbk-2 null allele (pk1427). Mutations were generated with QuickChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) and confirmed by sequencing.

RNAi

RNAi was performed using the feeding method (Timmons et al., 2001). Feeding clones were grown in LB + ampicillin (100 µg/ml) at 37°C and spread on NNGM (nematode nutritional growth medium) + Amp (100 µg/ml) + IPTG (80 µg/ml). L4 hermaphrodites were fed at 25°C for 24–30 hr before examination.

Antibodies

Anti-EGG-4/5 and anti-MBK-2 sera were generated in rabbits against the peptides CVSEKPKDEGRREDSGH and CKLVRNEKRFHRQADEEI, respectively (Covance). Both antibodies blotted against whole worm extracts identified prominent bands migrating in the expected size range (Sup. Fig. 6).

Immunofluorescence and Microscopy

Embryos and gonads were fixed on slides in −20°C methanol (15 min) and −20°C acetone (10 min). Primary antibodies were rabbit anti-MBK-2 (1:5000, Covance), rabbit anti-EGG-4/5 (1:2500, Covance), guinea pig anti-EGG-3 (1:10000, Covance), and rabbit anti-MEI-1-Ser92P (1:2000). Secondary antibodies were Cy3 goat anti-rabbit (1:600, Jackson ImmunoResearch), and Alexa 568 goat anti-guinea pig (1:600, Molecular Probes). Images were acquired with a Hamamatsu ORCA-ER digital camera attached to a Zeiss Axioplan 2, processed with IPLab software (Scanalytics, Inc.) and Photoshop CS.

Protein preparation from worm extracts and Western blotting

Staged hermaphrodites suspended in ice-cold lysis/homogenization buffer (50 mM HEPES [pH 7.4], 300 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA, 10% glycerol, 0.5 mM DTT, 0.05% NP-40, phosSTOP phosphatase inhibitor cocktail tablet [Roche], and complete Mini protease inhibitor tablet [Roche]) were frozen dropwise in liquid nitrogen, grinded by mortar and lysed by sonication. Extracts centrifuged (4°C, 14,000 rpm, 30 min) and filtered [0.22 µm filters (Millipore)] were precleared with protein A-agarose beads (Pierce) coupled to rabbit IgG (Sigma). Pre-cleared extracts were incubated with Protein A-agarose beads coupled to anti-GFP or anti-MBK-2 antibodies, or EZview red M2 beads (Sigma – for FLAG tagged fusions) at 4°C overnight and washed three times with ice-cold homogenization buffer. For phosphatase treatment, the immunoprecipitates were incubated with Calf Intestinal Alkaline Phosphatase (CIP) for 30 min at 37°C. Precipitates and input were run on 4%–12% or 7% SDS-PAGE (Invitrogen).

Preparation of Recombinant Proteins in E. coli

MBP fusions were grown in E. coli strain CAG456 and induced with 300 uM isopropyl-β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) overnight at 15°C. Bacterial pellets were washed and resuspended in ice-cold column buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, 500 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 10% glycerol), passed once through a French Press, and centrifuged (SW41 rotor at 36,000 RPM, or equivalent, for 30 min). MBP fusions were purified from cleared lysates by affinity chromatography (amylose resin, New England Biolabs) and eluted with column buffer plus 10 mM maltose. Eluates were stored at −80°C.

FLAG and GST fusions were created as amino-terminal fusions using pKC-5.02 and pDEST-15, respectively, and expressed in BL21(DE3) gold (Invitrogen). Glutathione-Sepharose 4B beads (Amersham Pharmacia) were incubated with GST-fusion extracts at 4°C for 2 hr in PBST (phosphate –buffered saline with 1% Triton X-100). EZview red M2 beads (Sigma) were incubated with FLAG-fusion extracts in binding buffer (20 mM HEPES [pH 7.6], 200 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 6% glycerol, 0.5 mM DTT, 0.1% NP-40 and complete mini protease inhibitor tablet [Roche]) at 4°C for 2 hr, and washed. Bound proteins were eluted by boiling in 2 X LDS sample buffer (Invitrogen) and subjected to 4–12% SDS-PAGE (Invitrogen) for Western blot analysis.

The MBK-2 substrate MEI-1(51–150) was cloned into pGEX-6p-1 (amino-terminal GST fusion), grown in BL21(DE3) gold (Invitrogen) induced with 500 uM IPTG at 37°C for 2 hr. Bacteria pellets were resuspended in ice-cold Lysis Buffer (phosphate-buffered saline, 10 mM EGTA, 10 mM EDTA, 0.25 M NaCl, 0.2% Tween-20, 10 mM DTT, and complete mini protease inhibitor tablet [Roche]) and sonicated. The crude extracts were centrifuged (SW41 rotor at 36,000 RPM, or equivalent, for 30 min) and incubated with Glutathione-Sepharose 4B beads (Amersham Pharmacia) at 4°C for 2 hr in Lysis Buffer. Washed beads were incubated with Prescission Protease in Cleavage Buffer (50 mM HEPES [pH 7.6], 150 mM NaCl, 1M EDTA, 0.01% Tween-20, and 1mM DTT) at 4°C overnight. Recombinant MEI-1(51–150) was eluted in Cleavage Buffer and stored at −80°C.

Preparation of Recombinant Proteins in HEK293 cells

HEK293 cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 100 units/ml penicillin and streptomycin. Cells were transfected using FuGENE 6 (Roche) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cells were rinsed with ice-cold PBS and lysed in lysis buffer (20 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 0.2 M NaCl, 0.5% Triton X-100, 5% glycerol, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, phosSTOP phophatase inhibitor cocktail tablet [Roche], 1 mM dithiothreitol, and complete Mini protease inhibitor cocktail tablet [Roche]). EZview red M2 beads (Sigma) were incubated with cell extracts at 4°C for 2 hr and washed 5 times with ice-cold lysis buffer. The FLAG-tagged precipitates were subject to 4%–12% SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis or kinase assays (see below).

Kinase Assays

hCdk1 kinase assays

hCdk-1 (20units, NEB) was incubated with MBP fusions or FLAG:fusions (on EZ view red M2 beads) in 1 X NEB protein kinase buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 10 mM MgCl2, 2 mM DTT, 1 mM EGTA, 0.01 % Brij 35) with cold or cold + 300 µCi/µmol γ-32P-ATP [Amersham Pharmacia] for 30 min. Reactions were stopped with 2 X LDS sample buffer (Invitrogen). Samples were boiled for 5 min and subject to 4–12% SDS-PAGE (Invitrogen – to measure 32P incorporation) or 7% SDS page (to observe mobility shift).

MBK-2 kinase assays

Partially purified MBP:MBK-2 (0.1uM) or immunoprecipitated GFP:MBK-2 (on Protein A beads) or FLAG:MBK-2 (on EZview red M2 beads) were incubated with MEI-1(51–150) in kinase buffer (50mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 10 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM EGTA, 0.1% beta-mercaptoethanol [BME]) with 200 µM ATP and 300 µCi/µmol γ-32P-ATP [Amersham Pharmacia] at 30°C. Reactions were stopped with 2X LDS sample buffer (Invitrogen). Samples were boiled for 5 min and subject to 4–12% SDS-PAGE (Invitrogen). MEI-1(51–150) was visualized with SimplyBlue SafeStain (Invitrogen). 32P incorporation was detected in the same gel by phosphorimager (Amersham Pharmacia). Relative kinase activity was calculated by measuring 32P incorporation with ImageQuant 5.2 (Molecular Dynamics), normalizing for the amount of MBK-2 (using anti:MBK-2 antibody for MBK-2 from mammalian cells and worms), and expressing all values as ratios compared to wild-type activity.

To analyze MBK-2 activity after phosphorylation by hCdk1, MBP:MBK-2 (0.1uM) or immunoprecipitated FLAG:MBK-2 (on EZview red M2 beads) were treated with or without 20u hCdk1 in 1 X NEB protein kinase buffer with 100uM cold ATP at 30°C for 30 min. MBP:MBK-2 was repurified on maltose beads before performing the MBK-2 kinase assay. Maltose or EZview red M2 beads were washed twice with 1Xkinase buffer and incubated with MEI-1(51–150) and 200 µM ATP and 300 µCi/µmol γ-32P-ATP (Perkin Elmer) at 30oC for 30 min. Samples were boiled and run on 4%–12% SDS-PAGE. hCdk1 does not phosphorylate MEI-1 (Fig. 2).

MBP:MBK-2 (0.1 uM), with or without FLAG:EGG-4 (0.2 uM), and with 7 concentrations of MEI-1(51–150) (0.1, 0.3, 0.7, 2, 3, 4, 5 uM) was used for Fig. 6C. The Michaelis-Menten kinetic curve was generated with Prizm 4 (GraphPad).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We gratefully thank Chih-Long Chang for hosting K. C. in 2009, Miranda Darby, Hani Zaher and Rachel Green for help and advice, J. Pellettieri for strains, and Rueyling Lin and members of the Seydoux lab for comments on the manuscript. This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health [Grants R01HD37047 (GS) and R01HD054681 (AS)] and a Johnson & Johnson Discovery Award (AS). G. Seydoux is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bahler J, Nurse P. Fission yeast Pom1p kinase activity is cell cycle regulated and essential for cellular symmetry during growth and division. EMBO J. 2001;20:1064–1073. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.5.1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahler J, Pringle JR. Pom1p, a fission yeast protein kinase that provides positional information for both polarized growth and cytokinesis. Genes Dev. 1998;12:1356–1370. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.9.1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker W, Joost HG. Structural and functional characteristics of Dyrk, a novel subfamily of protein kinases with dual specificity. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 1999;62:1–17. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60503-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg J, Tymoczko JL, Stryer L. Biochemistry. Sixth Edition. W. H. Freeman; 2006. edn. [Google Scholar]

- Blethrow JD, Glavy JS, Morgan DO, Shokat KM. Covalent capture of kinase-specific phosphopeptides reveals Cdk1-cyclin B substrates. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:1442–1447. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708966105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowerman B, Kurz T. Degrade to create: developmental requirements for ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis during early C. elegans embryogenesis. Development. 2006;133:773–784. doi: 10.1242/dev.02276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner S. The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1974;77:71–94. doi: 10.1093/genetics/77.1.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burrows AE, Sceurman BK, Kosinski ME, Richie CT, Sadler PL, Schumacher JM, Golden A. The C. elegans Myt1 ortholog is required for the proper timing of oocyte maturation. Development. 2006;133:697–709. doi: 10.1242/dev.02241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Agostino I, Merritt C, Chen PL, Seydoux G, Subramaniam K. Translational repression restricts expression of the C. elegans Nanos homolog NOS-2 to the embryonic germline. Dev Biol. 2006;292:244–252. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.11.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Da Costa M, Bach L, Landrieu I, Bellec Y, Catrice O, Brown S, De Veylder L, Lippens G, Inze D, Faure JD. Arabidopsis PASTICCINO2 is an antiphosphatase involved in regulation of cyclin-dependent kinase A. Plant Cell. 2006;18:1426–1437. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.040485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depetris RS, Hu J, Gimpelevich I, Holt LJ, Daly RJ, Hubbard SR. Structural basis for inhibition of the insulin receptor by the adaptor protein Grb14. Mol Cell. 2005;20:325–333. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Detwiler MR, Reuben M, Li X, Rogers E, Lin R. Two zinc finger proteins, OMA-1 and OMA-2, are redundantly required for oocyte maturation in C. elegans. Dev Cell. 2001;1:187–199. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(01)00026-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman E. Mirk/Dyrk1B in cancer. J Cell Biochem. 2007;102:274–279. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guven-Ozkan T, Nishi Y, Robertson SM, Lin R. Global transcriptional repression in C. elegans germline precursors by regulated sequestration of TAF-4. Cell. 2008;135:149–160. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes JK, Solomon MJ. A predictive scale for evaluating cyclin-dependent kinase substrates. A comparison of p34cdc2 and p33cdk2. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:25240–25246. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.41.25240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horner VL, Wolfner MF. Transitioning from egg to embryo: triggers and mechanisms of egg activation. Dev Dyn. 2008;237:527–544. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter T. Anti-phosphatases take the stage. Nat Genet. 1998;18:303–305. doi: 10.1038/ng0498-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kentrup H, Becker W, Heukelbach J, Wilmes A, Schurmann A, Huppertz C, Kainulainen H, Joost HG. Dyrk, a dual specificity protein kinase with unique structural features whose activity is dependent on tyrosine residues between subdomains VII and VIII. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:3488–3495. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.7.3488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim S, Zou Y, Friedman E. The transcriptional activator Mirk/Dyrk1B is sequestered by p38alpha/beta MAP kinase. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:49438–49445. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206840200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lochhead PA, Sibbet G, Morrice N, Cleghon V. Activation-loop autophosphorylation is mediated by a novel transitional intermediate form of DYRKs. Cell. 2005;121:925–936. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu C, Mains PE. The C. elegans anaphase promoting complex and MBK-2/DYRK kinase act redundantly with CUL-3/MEL-26 ubiquitin ligase to degrade MEI-1 microtubule-severing activity after meiosis. Dev Biol. 2007;302:438–447. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.09.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruyama R, Velarde NV, Klancer R, Gordon S, Kadandale P, Parry JM, Hang JS, Rubin J, Stewart-Michaelis A, Schweinsberg P, et al. EGG-3 regulates cell-surface and cortex rearrangements during egg activation in Caenorhabditis elegans. Curr Biol. 2007;17:1555–1560. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishi Y, Lin R. DYRK2 and GSK-3 phosphorylate and promote the timely degradation of OMA-1, a key regulator of the oocyte-to-embryo transition in C. elegans. Dev Biol. 2005;288:139–149. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.09.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishi Y, Rogers E, Robertson SM, Lin R. Polo kinases regulate C. elegans embryonic polarity via binding to DYRK2-primed MEX-5 and MEX-6. Development. 2008;135:687–697. doi: 10.1242/dev.013425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang KM, Ishidate T, Nakamura K, Shirayama M, Trzepacz C, Schubert CM, Priess JR, Mello CC. The minibrain kinase homolog, mbk-2, is required for spindle positioning and asymmetric cell division in early C. elegans embryos. Dev Biol. 2004;265:127–139. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2003.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellettieri J, Reinke V, Kim SK, Seydoux G. Coordinate activation of maternal protein degradation during the egg-to-embryo transition in C. elegans. Dev Cell. 2003;5:451–462. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00231-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pils B, Schultz J. Evolution of the multifunctional protein tyrosine phosphatase family. Mol Biol Evol. 2004;21:625–631. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msh055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Praitis V, Casey E, Collar D, Austin J. Creation of low-copy integrated transgenic lines in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 2001;157:1217–1226. doi: 10.1093/genetics/157.3.1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quintin S, Mains PE, Zinke A, Hyman AA. The mbk-2 kinase is required for inactivation of MEI-1/katanin in the one-cell Caenorhabditis elegans embryo. EMBO Rep. 2003;4:1175–1181. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schubert CM, Lin R, de Vries CJ, Plasterk RH, Priess JR. MEX-5 and MEX-6 function to establish soma/germline asymmetry in early C. elegans embryos. Mol Cell. 2000;5:671–682. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80246-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirayama M, Soto MC, Ishidate T, Kim S, Nakamura K, Bei Y, van den Heuvel S, Mello CC. The Conserved Kinases CDK-1, GSK-3, KIN-19, and MBK-2 Promote OMA-1 Destruction to Regulate the Oocyte-to-Embryo Transition in C. elegans. Curr Biol. 2006;16:47–55. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.11.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Songyang Z, Blechner S, Hoagland N, Hoekstra MF, Piwnica-Worms H, Cantley LC. Use of an oriented peptide library to determine the optimal substrates of protein kinases. Curr Biol. 1994;4:973–982. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00221-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stitzel ML, Cheng KC, Seydoux G. Regulation of MBK-2/Dyrk Kinase by Dynamic Cortical Anchoring during the Oocyte-to-Zygote Transition. Curr Biol. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.08.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stitzel ML, Pellettieri J, Seydoux G. The C. elegans DYRK Kinase MBK-2 Marks Oocyte Proteins for Degradation in Response to Meiotic Maturation. Curr Biol. 2006;16:56–62. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.11.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmons L, Court DL, Fire A. Ingestion of bacterially expressed dsRNAs can produce specific and potent genetic interference in Caenorhabditis elegans. Gene. 2001;263:103–112. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(00)00579-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voronina E, Wessel GM. The regulation of oocyte maturation. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2003;58:53–110. doi: 10.1016/s0070-2153(03)58003-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wishart MJ, Dixon JE. Gathering STYX: phosphatase-like form predicts functions for unique protein-interaction domains. Trends Biochem Sci. 1998;23:301–306. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(98)01241-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida K. Role for DYRK family kinases on regulation of apoptosis. Biochem Pharmacol. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2008.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.