Abstract

We previously reported that attachment of atrial myocytes to the extracellular matrix protein laminin (LMN), decreases adenylate cyclase (AC)/cAMP and increases β2-adrenergic receptor (AR) stimulation of L-type Ca2+ current (ICa,L). This study therefore sought to determine whether LMN enhances β2-AR signalling via a cAMP-independent mechanism, i.e. cytosolic phospholipase A2 (cPLA2) signalling. Studies were performed on acutely isolated atrial myocytes plated on uncoated coverslips (−LMN) or coverslips coated with LMN (+LMN). As previously reported, 0.1 μm zinterol (zint-β2-AR) stimulation of ICa,L was larger in +LMN than −LMN myocytes. In +LMN myocytes, zint-β2-AR stimulation of ICa,L was inhibited by inhibition of cPLA2 by arachidonyltrifluoromethyl ketone (AACOCF3; 10 μm), inhibition of Gi by pertussis toxin and chelation of intracellular Ca2+ by 10 μm BAPTA-AM. In contrast to zinterol, stimulation of ICa,L by fenoterol (fen-β2-AR), a β2-AR agonist that acts exclusively via Gs signalling, was smaller in +LMN than −LMN myocytes. Arachidonic acid (AA; 5 μm) stimulated ICa,L to a similar extent in −LMN and +LMN myocytes. Inhibition of cAMP-dependent protein kinase A (cAMP/PKA) by either 5 μm H−89 or 1 μm KT5720 in −LMN myocytes mimicked the effects of +LMN myocytes to enhance zint-β2-AR stimulation of ICa,L, which was blocked by 10 μm AACOCF3. In contrast, H−89 inhibited fen-β2-AR stimulation of ICa,L, which was unchanged by AACOCF3. Inhibition of ERK1/2 by 1 μm U0126 inhibited zint-β2-AR stimulation of ICa,L in +LMN myocytes and −LMN myocytes in which cAMP/PKA was inhibited by KT5720. In −LMN myocytes, cytochalasin D prevented inhibition of cAMP/PKA from enhancing zint-β2-AR stimulation of ICa,L. We conclude that LMN enhances zint-β2-AR stimulation of ICa,L via Gi/ERK1/2/cPLA2/AA signalling which is activated by concomitant inhibition of cAMP/PKA signalling and dependent on the actin cytoskeleton. These findings provide new insight into the cellular mechanisms by which the extracellular matrix can remodel β2-AR signalling in atrial muscle.

Introduction

In cardiac muscle both β1-adrenergic receptor (AR) and β2-AR signalling regulates L-type Ca2+ current (ICa,L), with β1-ARs being the predominant signalling mechanism. In general, β1-ARs are coupled exclusively to Gs/adenylate cyclase (AC)/cAMP-dependent PKA (cAMP/PKA) signalling whereas β2-ARs are coupled to both Gs and Gi signalling pathways. β2-ARs act via Gs to stimulate AC/cAMP/PKA signalling and via Gi to stimulate a variety of signalling pathways including cytosolic phospholipase A2 (cPLA2)/arachidonic acid (AA) signalling (Pavoine et al. 1999).

The extracellular matrix (ECM) is composed of a variety of proteins including laminin, fibronectin and collagen. Adult cardiomyocytes primarily attach to laminin (LMN) via low-affinity cell surface receptors known as integrins (Terracio et al. 1991). Along with its role in cell attachment, the ECM–β-integrin complex is an important modulator of intracellular signalling, i.e. so-called ‘outside-in’ signalling (Hynes, 1992; Schwartz et al. 1995; Dedhar, 1999). Atrial disease is commonly associated with atrial fibrosis, i.e. structural remodelling, which is associated with increases in ECM proteins.

We previously reported that attachment of atrial myocytes to LMN acts via β1-integrin receptors to decrease β1-AR and increase β2-AR stimulation of ICa,L (Wang et al. 2000b). These changes in β-AR are similar to those that occur during remodelling of the failing heart in humans (Bristow et al. 1986) and experimental animals (Kiuchi et al. 1993). In addition, we reported that LMN decreases β1-AR stimulation via inhibition of Gs/AC/cAMP signalling (Wang et al. 2009). The fact that LMN inhibits Gs/AC/cAMP signalling and yet increases β2-AR signalling suggests that LMN stimulates β2-AR signalling through a mechanism independent of Gs/AC/cAMP signalling. In this regard, Pavoine et al. (1999) reported that β2-AR activation of cPLA2 signalling may compensate for depressed AC/cAMP signalling. Therefore, the present study sought to determine whether atrial cell attachment to LMN enhances β2-AR signalling via cPLA2 signalling and whether this mechanism is activated by concomitant inhibition of cAMP/PKA signalling. The present findings provide new insights into the potential role of the ECM to remodel β2-AR signalling in atrial muscle.

Methods

Adult cats of either sex were anaesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (50 mg kg−1, i.p.). Once fully anaesthetized, a bilateral thoracotomy was performed, and the heart was rapidly excised and mounted on a Langendorff perfusion apparatus. After enzyme (collagenase; type II, Worthington Biochemical) digestion, atrial myocytes were isolated as previously reported (Wang et al. 2000a). The animal and experimental protocols used in this study were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood, IL, USA. IACUC prescribed the rules for the animal care and supervised their enforcement. This study required 34 animals.

Electrophysiological recordings from myocytes were performed in the perforated (nystatin) patch whole-cell configuration at room temperature, as previously described (Wang et al. 2000a). L-type Ca2+ current (ICa,L) was activated by depolarizing pulses from a holding potential of −40 mV to 0 mV for 200 ms every 5 s and measured in relation to steady-state current. β2-AR stimulation was achieved by 0.1 μm zinterol (zint-β2-AR), a specific β2-AR agonist that activates both Gi and Gs signalling (Wang et al. 2002). β2-AR stimulation also was achieved by 0.1 μm fenoterol (fen-β2-AR), a specific β2-AR agonist that acts exclusively via Gs signalling (Dedkova et al. 2002). β1-AR stimulation was achieved by 0.1 μm isoproterenol (isoprenaline; ISO-β1-AR) plus 0.01 μm ICI 118,551, a specific β2-AR antagonist. Each agonist was applied for approximately 4 min and the effects of each agonist on peak ICa,L amplitude was recorded at the maximum steady-state response. Generally, we compared two groups of freshly isolated atrial myocytes obtained from the same hearts: control cells plated on uncoated glass coverslips (−LMN), and test cells plated on glass coverslips coated with LMN (+LMN; 40 μg ml−1) for at least 2 h, as previously described (Wang et al. 2000a). Control experiments have shown that atrial myocytes plated on poly-l-lysine, a non-specific substrate for cell attachment, fail to show changes in β-AR signalling similar to cells attached to LMN (Wang et al. 2000b). It is also important to note that freshly isolated cardiomyocytes retain LMN on their cell surface (Lundgren et al. 1988). Moreover, freshly isolated cardiomyocytes exhibit responses to cholinergic and β-AR stimulation which are similar to multicellular cardiac preparations. For example, freshly isolated atrial myocytes, like all cardiac muscle, exhibit predominantly β1-AR over β2-AR signalling (Wang et al. 2000b). Cell attachment to LMN decreases the β1-/β2-AR signalling ratio resulting in predominantly β2-AR over β1-AR signalling (Wang et al. 2000b). Therefore, atrial cell attachment to LMN is not restoring LMN-mediated signalling somehow lost during the cell isolation procedure. Our findings are consistent with the idea that LMN activates additional integrin receptors on atrial myocytes which alters normal β−AR function.

Drugs used in this study include: zinterol; arachidonyltrifluoromethyl ketone (AACOCF3); H-89; KT5720; pertussis toxin (PTX); fenoterol; isoproterenol; ICI 118,551; 1,2-bis-(o-aminophenoxy)-ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid, tetraacetoxymethyl ester (BAPTA-AM); cytochalasin D; U0126 (all from Sigma Chemical); arachidonic acid (AA) (Biomol).

Data are mean ± standard error of the mean (s.e.m.). Measurements were analysed using either Student's paired or unpaired t test for significance at P < 0.05. Multiple comparisons were performed by ANOVA followed by a Student–Newman–Keuls test with significance at P < 0.05.

Results

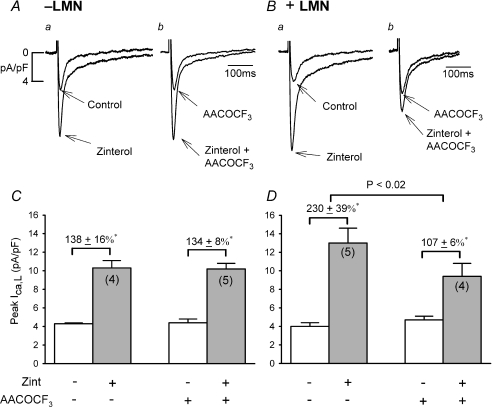

Figure 1A–B shows original traces of ICa,L recorded from −LMN (A) and +LMN (B) atrial myocytes and the effects of 0.1 μm zinterol (zint) in the absence and presence of 10 μm AACOCF3, a selective inhibitor of cPLA2 (Riendeau et al. 1994). The bar graphs (C and D) summarize the data. First, control zint-β2-AR stimulation of ICa,L was significantly greater in +LMN (Ba and D; 230 ± 39%, N= 5) compared to −LMN (Aa and C; 138 ± 16%, N= 4) atrial myocytes (P < 0.05), confirming our previous report (Wang et al. 2000b). In −LMN myocytes AACOCF3 had no significant effects on basal ICa,L amplitude (C; compare open bars) or zint-β2-AR stimulation of ICa,L (Ab and C; 134 ± 8%, N= 5). In +LMN myocytes AACOCF3 also had no significant effect on basal ICa,L amplitude (D; compare open bars), although AACOCF3 significantly inhibited zint-β2-AR stimulation of ICa,L (Bb and D; 107 ± 6%, N= 4, P < 0.02). As summarized in panels C and D, inhibition of cPLA2 had no effect on β2-AR stimulation in −LMN myocytes (C) while it significantly decreased β2-AR stimulation in +LMN myocytes (D). These findings suggest that cPLA2 plays little role in β2-AR regulation of ICa,L in freshly isolated cat atrial myocytes. However, in atrial myocytes attached to LMN, β2-AR signalling may be enhanced via activation of cPLA2 signalling.

Figure 1. Effects of 10 μm AACOCF3 on zint-β2-AR stimulation of ICa,L in −LMN and +LMN atrial myocytes.

A and B, original recordings of ICa,L in −LMN (A) and +LMN (B) atrial myocytes. In −LMN myocytes, zint-induced stimulation of ICa,L was similar in the absence (Aa) and presence (Ab) of AACOCF3. Control zint-β2-AR stimulation of ICa,L was greater on +LMN (Ba) than −LMN (Aa) myocytes. In +LMN myocytes, zint-β2-AR stimulation of ICa,L was inhibited by AACOCF3 (Bb) compared to control (Ba). C and D, bar graphs summarizing the data show that AACOCF3 had no effect on zint-β2-AR stimulation of ICa,L in −LMN myocytes (C) and AACOCF3 significantly decreased zint-β2-AR stimulation of ICa,L in +LMN myocytes (D). Bar graphs in each figure (Figs 1–7) show peak current densities of basal ICa,L (open bars) and agonist-stimulated ICa,L (shaded bars). Numbers in parentheses indicate the number of cells studied. *P < 0.05.

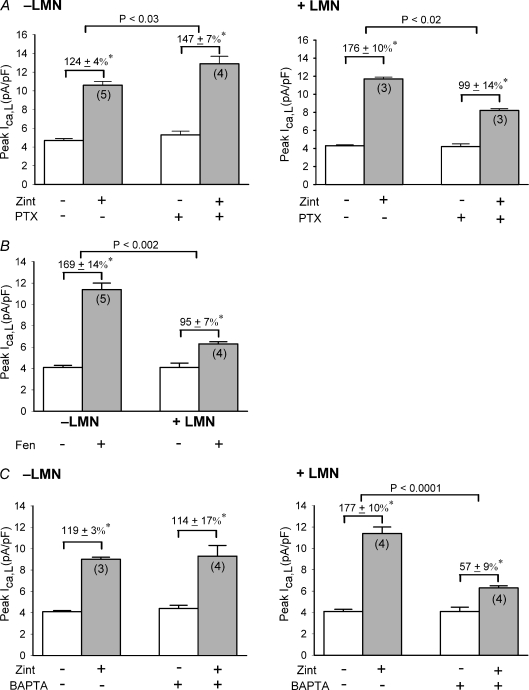

In atrial muscle, β2-ARs are coupled to both Gs and Gi signalling (Kilts et al. 2000; Wang et al. 2002) and cPLA2 signalling is coupled to β2-ARs via pertussis toxin (PTX)-sensitive Gi (Pavoine et al. 1999). We therefore determined the effects of zint-β2-AR stimulation of ICa,L in −LMN and +LMN atrial myocytes either untreated (control) or treated with PTX (5 μg ml−1 for 3 h at 36°C). Figure 2A shows that in −LMN myocytes zint-β2-AR stimulation of ICa,L was significantly larger in cells pre-treated with PTX compared to control (control, 124 ± 4%, N= 5 vs. PTX, 147 ± 7%, N= 4; P < 0.05), consistent with an inhibitory influence of Gi on β2-AR/Gs signalling. In contrast, in +LMN myocytes zint-β2-AR stimulation of ICa,L was significantly smaller in cells pre-treated with PTX compared to control (control, 176 ± 10%, N= 3 vs. PTX, 99 ± 13%, N= 3; P < 0.02). These findings indicate that LMN enhances β2-AR stimulation via a Gi signalling mechanism, consistent with cPLA2 activation.

Figure 2. Zint-β2-AR stimulation of ICa,L via cPLA2 signaling is mediated via PTX-sensitive Gi-signaling and reqiures intracellular Ca2+ release.

A, effects of pertussis toxin (PTX) on zint-β2-AR stimulation of ICa,L in −LMN and +LMN atrial myocytes. In −LMN myocytes, PTX significantly increased zint-β2-AR stimulation of ICa,L. In +LMN myocytes, PTX significantly decreased zint-β2-AR stimulation of ICa,L. B, effects of 0.1 μm fenoterol (Fen) β2-AR stimulation of ICa,L in −LMN and +LMN atrial myocytes. Fen-β2-AR stimulation of ICa,L was significantly smaller in +LMN than −LMN myocytes. C, effects of 10 μm BAPTA-AM on zint-β2-AR stimulation of ICa,L in −LMN and +LMN atrial myocytes. In −LMN myocytes, zint-β2-AR stimulation was unchanged by BAPTA. In +LMN myocytes, BAPTA significantly decreased zint-β2-AR stimulation of ICa,L compared to control responses. *P < 0.05.

Another way of testing whether LMN enhances β2-AR signalling through a Gi-coupled signalling pathway is to determine the effects of fenoterol (fen), a specific β2-AR agonist that acts exclusively via Gs signalling (Dedkova et al. 2002). If LMN enhances β2-AR signalling through a Gi-mediated pathway, then LMN should inhibit rather than enhance fen-β2-AR stimulation of ICa,L. In fact, as shown in Fig. 2B, 0.1 μm fen-β2-AR stimulation of ICa,L was significantly smaller in +LMN than in −LMN atrial myocytes (−LMN, 169 ± 14%, N= 5 vs.+LMN, 95 ± 7%, N= 4; P < 0.002). These findings are consistent with our previous reports that LMN decreases Gs/AC/cAMP activity (Wang et al. 2000a, 2009) and strongly supports the idea that LMN enhances β2-AR signalling via a Gi-coupled signalling pathway, consistent with cPLA2 signalling.

Activation of cPLA2 is Ca2+ dependent (Leslie, 2004). Therefore, if LMN is enhancing β2-AR stimulation via cPLA2 signalling then chelation of intracellular Ca2+ should prevent the effects of LMN to enhance zint-β2-AR signalling. As shown in Fig. 2C, we determined the effects of zint-β2-AR stimulation of ICa,L in −LMN and +LMN myocytes in control and test cells pre-treated with 10 μm BAPTA-AM (15 min), a cell-permeable Ca2+ chelator. In −LMN myocytes, basal ICa,L was slightly but not statistically larger in BAPTA-treated cells compared to control (open bars) and zint-β2-AR stimulation of ICa,L was unaffected by BAPTA (control; 119 ± 3%, N= 3 vs. BAPTA; 114 ± 17%; N= 4). In +LMN myocytes, basal ICa,L was unaffected by BAPTA (open bars). However, zint-β2-AR stimulation of ICa,L was significantly inhibited in BAPTA-treated cells compared to control responses (control; 177 ± 10%; N= 4 vs. BAPTA; 57 ± 9%, N= 4, P < 0.0001). In other words, chelation of intracellular Ca2+ prevented the effects of LMN from enhancing β2-AR signalling. Additional experiments measuring intracellular [Ca2+] confirmed that 15 min exposure to BAPTA-AM abolished electrically stimulated Ca2+ transients (authors’ unpublished observations). These findings support the idea that Ca2+-dependent cPLA2 plays no role in −LMN myocytes (see Fig. 1) and that LMN enhances zint-β2-AR signalling via Ca2+-dependent cPLA2 signalling.

Cytosolic PLA2 hydrolyzes the sn-2 fatty acyl ester bonds of membranous phospholipids, leading to the release of arachidonic acid (AA). We therefore determined whether 5 μm AA stimulates ICa,L in −LMN and +LMN atrial myocytes. AA stimulated ICa,L to a similar extent in −LMN (57 ± 10%) and +LMN (65 ± 12%) myocytes (N= 8). These findings indicate that AA stimulates ICa,L in atrial myocytes and that LMN does not enhance β2-AR signalling by increasing the sensitivity of ICa,L channels to AA.

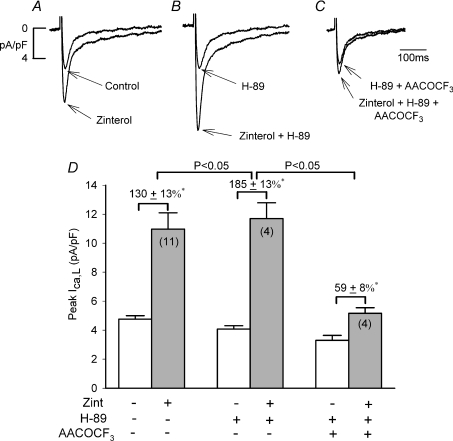

Our previous work indicates that LMN-mediated enhancement of β2-AR signalling is accompanied by inhibition of cAMP signalling (Wang et al. 2000a,b;). The following experiments were designed to determine whether β2-AR/cPLA2 signalling is activated by inhibition of cAMP/PKA. In other words, does pharmacological inhibition of cAMP/PKA in −LMN myocytes mimic the effects of +LMN myocytes to enhance β2-AR signalling. As shown in Fig. 3A–C and summarized in panel D, we determined the effects of zint-β2-AR stimulation in −LMN myocytes in the absence and presence of 5 μm H-89, an inhibitor of cAMP/PKA (Chijiwa et al. 1990). In control cells (A) zint-β2-AR stimulation significantly increased ICa,L (D; 130 ± 13%; N= 11). In another group of −LMN myocytes from the same hearts (B), 5 μm H-89 decreased basal ICa,L by −21 ± 2% (D; open bar, N= 4, P < 0.01), consistent with inhibition of basal cAMP/PKA activity. Interestingly, in the presence of H-89 (B), zint-β2-AR stimulation of ICa,L (D, 185 ± 13%; N= 4) was significantly enhanced compared to control zint-β2-AR stimulation (130 ± 13%, P < 0.05). In a third group of −LMN myocytes (C), 10 μm AACOCF3 plus H-89 decreased basal ICa,L by −31 ± 3% (D; open bar, N= 4; P < 0.01) and significantly inhibited zint-β2-AR stimulation of ICa,L (D; 59 ± 8%, N= 4) compared to either zinterol alone or zinterol plus H-89. These findings are in contrast to those in −LMN myocytes in the absence of H-89, in which AACOCF3 had no effect on zint-β2-AR stimulation of ICa,L (Fig. 1).

Figure 3. Effects of 5 μm H-89 on zint-β2-AR stimulation of ICa,L in the absence and presence of 10 μm AACOCF3.

A–C, original recordings of ICa,L from −LMN atrial myocytes. D, bar graphs summarize data obtained in A–C. Compared to control (A), 5 μm H-89 decreased basal ICa,L and enhanced zint-β2-AR stimulation of ICa,L (B). Zint-β2-AR stimulation of ICa,L was inhibited by the addition of 10 μm AACOCF3 (+ H-89) (C) compared to either control (A) or H-89 alone (B). D, summary graph indicates that zint-β2-AR stimulation of ICa,L was significantly increased by H-89 and significantly inhibited by AACOCF3 (+ H-89) compared to H-89 alone. *P < 0.05.

Similar results were obtained with KT5720 (KT), another cAMP/PKA inhibitor (Kase et al. 1987). As shown in Fig. 4A–C and summarized in panel D, in control (A), zint-β2-AR stimulation significantly increased ICa,L (D; 107 ± 8%, N = 5). In another group of cells from the same hearts (B), 1 μm KT decreased basal ICa,L by 21 ± 2% (D; open bar; N= 6; P < 0.01) and in the presence of KT (B), zint-β2-AR stimulation of ICa,L (D, 220 ± 11%, N= 6) was significantly enhanced compared to control zint-β2-AR stimulation (107 ± 8%, P < 0.05). In a third group of −LMN myocytes (C), 10 μm AACOCF3 plus KT decreased basal ICa,L by −16 ± 1% (D; open bar, N= 4; P < 0.005) and significantly inhibited zint-β2-AR stimulation of ICa,L (D; 67 ± 12%, N= 4) compared to either zinterol alone or zinterol plus KT. Again, these findings are in contrast to those in −LMN myocytes in the absence of KT, in which AACOCF3 had no effect on zint-β2-AR stimulation of ICa,L (Fig. 1). Together, these results indicate that pharmacological inhibition of cAMP/PKA mimics the effects of +LMN myocytes to enhance β2-AR stimulation of ICa,L via activation of cPLA2 signalling.

Figure 4. Effects of 1 μm KT5720 (KT) on zint-β2-AR stimulation of ICa,L in the absence and presence of 10 μm AACOCF3.

A–C, original recordings of ICa,L from −LMN atrial myocytes. D, bar graphs summarize data obtained in A–C. Compared to control (A), KT decreased basal ICa,L and enhanced zint-β2-AR stimulation of ICa,L (B). Zint-β2-AR stimulation of ICa,L was inhibited by the addition of 10 μm AACOCF3 (+ KT) (C) compared to either control (A) or H-89 alone (B). D, summary graph indicates that zint-β2-AR stimulation of ICa,L was significantly increased by KT and significantly inhibited by AACOCF3 (+ KT) compared to KT alone. *P < 0.05.

To confirm that H-89 was acting to inhibit cAMP/PKA activity, we determined the effect of H-89 on β1-AR stimulation (see Methods) which is mediated exclusively through cAMP/PKA. In −LMN cells, 5 μm H-89 decreased basal ICa,L by 22 ± 4% (N= 3). In the presence of H-89, ISO-β1-AR stimulation of ICa,L was almost completely blocked (control, 206 ± 25, N= 4 vs. H-89, 37 ± 3%, N= 3; P < 0.005).

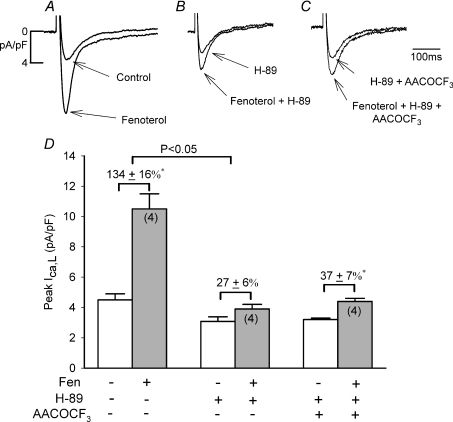

If inhibiting cAMP/PKA activity enhances β2-AR/Gi/cPLA2 signalling then fen-β2-AR stimulation, which acts exclusively via Gs/cAMP/PKA signalling, should not be enhanced by inhibition of cAMP/PKA. As shown in Fig. 5A–C and summarized in panel D, in control −LMN myocytes (A) fen-β2-AR stimulation significantly increased ICa,L (D; 134 ± 16%, N= 4). In another group of −LMN myocytes from the same hearts (B), 5 μm H-89 decreased basal ICa,L by −31 ± 4% (D, open bar), consistent with inhibition of basal cAMP/PKA. In contrast to zint-β2-AR stimulation, H-89 almost abolished fen-β2-AR stimulation of ICa,L (D; 27 ± 6%, N= 4). This finding is similar to the effects of H-89 to block ISO-β1-AR stimulation, which also is mediated exclusively via Gs/cAMP/PKA signalling. In a third group of −LMN myocytes (C), the addition of AACOCF3 plus H-89 had no significant additional effect on basal ICa,L (D; open bar) or fen-β2-AR stimulation of ICa,L (D; 37 ± 7%, N= 4). These experiments further confirm that H-89 acts to block cAMP/PKA and support the conclusion that inhibition of cAMP/PKA enhances zint-β2-AR stimulation through Gi-mediated cPLA2 signalling.

Figure 5. Effects of 5 μm H-89 on fenoterol (Fen)-β2-AR stimulation of ICa,L in the absence and presence of 10 μm AACOCF3.

A–C, original recordings of ICa,L from −LMN atrial myocytes. D, bar graphs summarize data obtained in A–C. In control, fen-β2-AR stimulation increased ICa,L. H-89 decreased basal ICa,L and significantly inhibited fen-β2-AR stimulation of ICa,L. Addition of AACOCF3 (+ H-89) had no additional inhibitory effect on fen-β2-AR stimulation of ICa,L compared to H-89 alone. *P < 0.05.

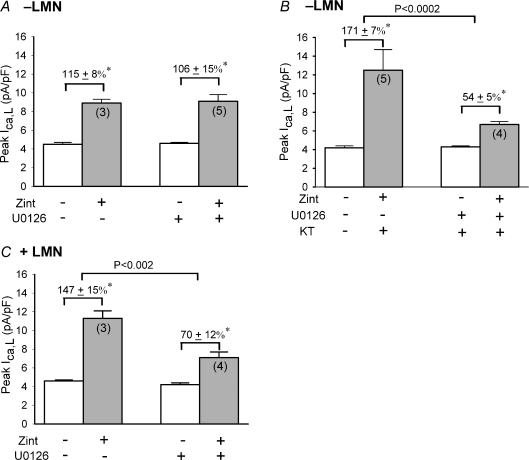

How does inhibition of cAMP/PKA enhance zint-β2-AR/cPLA2 signalling? Phosphorylation of cPLA2 by mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) contributes to the activation of cPLA2 (see Gijon & Leslie, 1999). In addition, cAMP/PKA can inhibit MAPKs ERK1/2 signalling (see Gerits et al. 2008). Therefore, inhibition of the inhibitory influence of cAMP/PKA may enhance zint-β2-AR/cPLA2 via activation of ERK1/2 signalling. In Fig. 6A and B we therefore determined whether inhibition of ERK1/2 could prevent the effect of cAMP/PKA inhibition from enhancing zint-β2-AR stimulation in −LMN myocytes. ERK1/2 was inhibited by U0126, a potent and selective inhibitor of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase (MEK1/2) (Favata et al. 1998). MEK1/2 is the immediate upstream activator of ERK1/2. As shown in Fig. 6A and B, U0126 was tested in control −LMN myocytes (A) and −LMN myocytes in which cAMP/PKA was inhibited by 1 μm KT5720 (KT) (B). Cells were exposed to U0126 for at least 15 min before recordings were obtained. U0126 had no significant effects on basal ICa,L amplitude (control, 4.2 ± 0.1 pA pF−1; N= 7 vs. U0126, 4.6 ± 0.1 pA pF−1; N= 9). As shown in Fig. 6A, in control −LMN myocytes zint-β2-AR stimulation of ICa,L was not significantly affected by U0126 (control, 115 ± 8%; N= 3 vs. U0126, 106 ± 15%; N= 5). However, as shown in Fig. 6B, U0126 significantly inhibited the effect of cAMP/PKA inhibition (KT) from enhancing zint-β2-AR stimulation of ICa,L (KT, 171 ± 7%; N= 5 vs. KT + U0126, 54 ± 5%; N= 4, P < 0.0002). As shown in Fig. 6C, U0126 also prevented +LMN myocytes from enhancing zint-β2-AR stimulation of ICa,L (control, 147 ± 15%; N= 3 vs. U0126, 70 ± 12%; N= 4, P < 0.002). These findings indicate that LMN-mediated inhibition of cAMP/PKA acts, at least in part, via activation of ERK1/2 to enhance zint-β2-AR signalling.

Figure 6. Effects of 1 μm U0126 on zint-β2-AR stimulation of ICa,L.

A, in −LMN myocytes, U0126 had no significant effects on zint-β2-AR stimulation of ICa,L. B, in −LMN myocytes, U0126 significantly inhibited the effect of 1 μm KT5720 (KT) to enhance zint-β2-AR stimulation of ICa,L. C, in +LMN myocytes, U0126 also significantly inhibited zint-β2-AR stimulation of ICa,L. *P < 0.05.

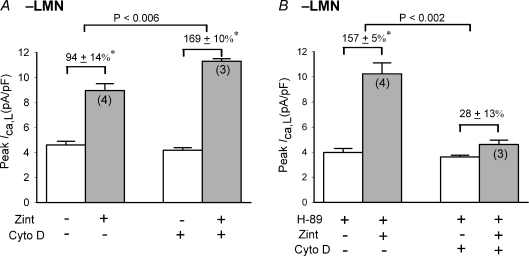

We previously reported in atrial myocytes that inhibition of actin polymerization by cytochalasin D prevents LMN-mediated changes in β-AR signalling (Wang et al. 2000b). If our current hypothesis is correct, then inhibition of actin polymerization also should prevent the enhancement of β2-AR signalling induced by pharmacological inhibition of cAMP/PKA in −LMN myocytes. We therefore determined the effects of cytochalasin D (cyto D), an agent that prevents actin polymerization (Carter, 1967), on zint-β2-AR stimulation of ICa,L in the absence (Fig. 7A) and presence (B) of 5 μm H-89 in −LMN myocytes. As shown in Fig. 7A, in control −LMN myocytes zint-β2-AR stimulation significantly increased ICa,L (94 ± 13%, N= 4). In −LMN myocytes treated with 10 μm cyto D (30 min), basal ICa,L was slightly reduced (–6 ± 1%; open bar, N= 3) and zint-β2-AR stimulation of ICa,L was significantly enhanced (169 ± 10%, N= 3) compared with control responses (94 ± 13%, P < 0.006). This is consistent with the idea that in cardiac myocytes, actin filaments restrict G-protein-coupled receptor-activated AC/cAMP formation (Head et al. 2006). In Fig. 7B we repeated the experiment in −LMN myocytes exposed to 5 μm H-89. As expected, H-89 decreased basal ICa,L by 21 ± 2% (N= 3) and enhanced zint-β2-AR stimulation of ICa,L (157 ± 5%, N= 4) compared to control responses in the absence of H-89 (A; 94 ± 13%, N= 4; P < 0.01). In −LMN myocytes pre-treated with cyto D (B), exposure to H-89 produced a typical inhibition of basal ICa,L by 20 ± 5% (N= 3). However, in cyto D-treated cells H-89 inhibited (rather than enhanced) zint-β2-AR stimulation of ICa,L (B; 28 ± 13%, N= 3) compared to control responses in the presence of H-89 alone (B; 157 ± 5%; P < 0.002). In other words, cyto D prevented inhibition of cAMP/PKA (H-89) from enhancing zint-β2-AR stimulation of ICa,L, suggesting that β2-AR/cPLA2 signalling is dependent on the organization of the actin cytoskeleton. Moreover, the fact that H-89 blocked the effects of cyto D to enhance zint-β2-AR stimulation of ICa,L indicates that the effects of cyto D to enhance zint-β2-AR stimulation were, in fact, mediated via cAMP/PKA activity.

Figure 7. Effects of 10 μm cytochalasin D on zint-β2-AR stimulation of ICa,L in −LMN atrial myocytes.

A, zint-β2-AR stimulation of ICa,L was significantly greater in cells treated with cytochalasin D compared with control cells. B, H-89 (5 μm) enhanced zint-β2-AR stimulation of ICa,L compared to control responses in the absence of H-89 (A). In −LMN myocytes treated with cytochalasin D, H-89 failed to enhance zint-β2-AR stimulation of ICa,L. *P < 0.05.

Discussion

Our previous work indicates that attachment of atrial myocytes to LMN inhibits β1-AR/Gs/AC/cAMP signalling (Wang et al. 2000a, 2009) and at the same time enhances β2-AR signalling (Wang et al. 2000b). This implies that LMN is enhancing β2-AR signalling through a cAMP-independent pathway that is receptor coupled to Gi. In fact, the present study indicates that LMN acts via inhibition of cAMP/PKA to enhance β2-AR stimulation of ICa,L via activation of Gi/ERK1/2/cPLA2/AA signalling.

The present study shows that PTX significantly inhibited zint-β2-AR stimulation of ICa,L in +LMN myocytes, consistent with the coupling of β2-ARs via Gi to cPLA2 signalling (Pavoine et al. 1999). Moreover, in contrast to zint-β2-AR stimulation, cell attachment to LMN decreased fen-β2-AR stimulation of ICa,L, which is similar to the effects of LMN to decrease β1-AR signalling (Wang et al. 2000b, 2009). This is consistent with the fact that fen-β2-AR and β1-AR signalling are both coupled exclusively via Gs and lends strong support to the idea that LMN enhances β2-AR signalling via a Gi-mediated mechanism. It seems unlikely that LMN is enhancing Gi because LMN does not enhance muscarinic receptor/Gi-mediated inhibition of basal ICa,L in atrial myocytes (Wang et al. 2000a). The role of cPLA2 is further supported by the present finding that inhibition of cPLA2 by AACOCF3 (Riendeau et al. 1994) prevented LMN-mediated enhancement of zint-β2-AR signalling. In contrast, AACOCF3 had no effect on zint-β2-AR stimulation in −LMN myocytes, indicating that cPLA2 plays little role in β2-AR signalling in freshly isolated atrial myocytes (Fig. 1). The present study also shows that AA stimulates ICa,L, consistent with the stimulatory effects of zint-β2-ARs acting via cPLA2 signalling. Moreover, the stimulatory effects of AA were similar in −LMN and +LMN myocytes, indicating that the effects of LMN to enhance zint-β2-AR signalling are not due to changes in the sensitivity of the ICa,L channel to AA. AA also stimulates ICa,L in guinea pig ventricular myocytes (Huang et al. 1992) and Ca2+ transients in embryonic chick ventricular myocytes (Pavoine et al. 1999), but AA inhibits ICa,L and intracellular Ca2+ release in rat ventricular myocytes (Xiao et al. 1997). Finally, chelation of intracellular [Ca2+] by BAPTA had no significant effects on zint-β2-AR signalling in −LMN myocytes but in +LMN myocytes BAPTA significantly inhibited zint-β2-AR stimulation, consistent with the Ca2+ dependence of cPLA2 (Leslie, 2004). The fact that BAPTA abolished electrically stimulated elevation of intracellular [Ca2+], i.e. Ca2+ transients (authors’ unpublished observations), but had no affect on basal Ca2+ influx via ICa,L (Fig. 2), suggests that cPLA2 activation in atrial myocytes is primarily dependent on intracellular Ca2+ release rather than Ca2+ influx.

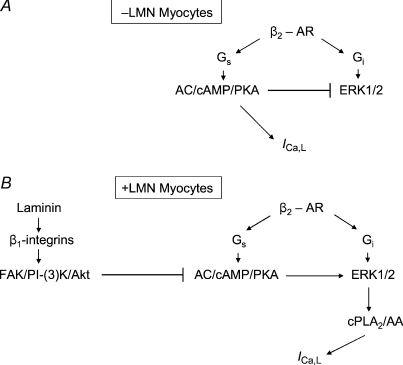

The present experiments also indicate that cell attachment to LMN enhances β2-AR signalling via a mechanism activated by inhibition of cAMP/PKA signalling. Indeed, inhibition of cAMP/PKA by two different pharmacological agents enhanced zint-β2-AR stimulation of ICa,L via cPLA2 in −LMN myocytes, much the same as cell attachment to LMN. The finding that fen-β2-AR stimulation of ICa,L was significantly inhibited (rather than enhanced) by inhibition of cAMP/PKA (H-89) also confirms that inhibition of cAMP/PKA enhances a Gi-coupled β2-AR signalling mechanism. The fact that pharmacological inhibition of cAMP/PKA activates β2-AR/cPLA2 signalling is consistent with our previous findings that LMN acts via phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase (PI-(3)K) signalling to inhibit AC/cAMP signalling (Wang et al. 2009) and elicits a concomitant increase in β2-AR signalling (Wang et al. 2000b). In embryonic chick ventricular myocytes (Pavoine et al. 1999) and rat ventricular myocytes (Ait-Mamar et al. 2005), β2-AR stimulation activates cPLA2 signalling. Moreover, β1-AR/cAMP signalling exerts a negative constraint on β2-AR/cPLA2 signalling leading to the idea that activation of β2-AR/cPLA2 may potentially compensate for depressed cAMP signalling (Pavoine et al. 1999). This idea is entirely consistent with the present results and may explain the present finding that cPLA2 plays no role in freshly isolated atrial myocytes, which exhibit significant endogenous cAMP synthesis (Wang et al. 2000a). Interestingly, in the studies of Pavoine et al. (1999) and Ait-Mamar et al. (2005) myocytes were cultured on LMN, raising the possibility that LMN may have activated β2-AR/cPLA2 signalling via a concomitant decrease in cAMP/PKA. This suggests that experimental design may contribute importantly to the results reported in different studies of cPLA2 signalling. The present study also indicates that inhibition of cAMP/PKA may enhance β2-AR/cPLA2 signalling by activation of ERK1/2 signalling. This finding is consistent with the fact that cAMP/PKA typically inhibits ERK1/2 signalling (see Gerits et al. 2008) and therefore inhibition of cAMP/PKA removes this inhibitory control, resulting in the activation of ERK1/2 signalling. Moreover, ERK1/2 contributes, along with other signalling mechanisms, to activation of cPLA2 (see Hirabayashi et al. 2004). In embryonic chick cardiomyocytes (cultured on LMN) β2-AR stimulation acts via ERK1/2 to stimulate cPLA2 (Magne et al. 2001). Therefore, the schematic diagram in Fig. 8A and B summarizes our previous (Wang et al. 2000a, 2009) and present results. Zinterol stimulates β2-ARs coupled to both Gs and Gi signalling pathways. Panel A shows that in −LMN myocytes, zint-β2-ARs act via Gs/AC/cAMP/PKA to stimulate ICa,L. In addition, stimulation of cAMP/PKA inhibits ERK1/2 and thereby prevents activation of cPLA2 signalling. Panel B shows that in +LMN myocytes, laminin binding to β1-integrins acts via focal adhesion kinase (FAK)/PI-(3)K/protein kinase B (Akt) signalling to inhibit AC/cAMP/PKA (Wang et al. 2009). As discussed above, the inhibition of cAMP/PKA activates ERK1/2 and thereby enhances β2-AR stimulation of ICa,L via Gi-coupled cPLA2/AA signalling.

Figure 8. Schematic diagram showing the proposed signalling mechanisms responsible for the effects of laminin to enhance β2-AR stimulation of ICa,L in atrial myocytes.

Zinterol stimulates β2-ARs coupled to both Gs and Gi signalling pathways. A, in −LMN myocytes β2-ARs act via Gs/AC/cAMP/PKA to stimulate ICa,L. Stimulation of cAMP/PKA also inhibits ERK1/2 signalling preventing activation of cPLA2. B, in +LMN myocytes laminin binding to β1-integrins activates focal adhesion kinase (FAK)/phosphatidylinositol-3′ kinase (PI-(3)K)/protein kinase B (Akt) signalling which inhibits AC/cAMP/PKA activity. Inhibition of cAMP/PKA stimulates ERK1/2 which enhances β2-AR stimulation of ICa,L via activation of Gi-coupled cPLA2/AA signalling.

We previously reported that cytochalasin D prevents the effects of LMN to both inhibit AC/cAMP (Wang et al. 2000a) and enhance β2-AR signalling (Wang et al. 2000b). In the present experiments cytochalasin D also prevented activation of β2-AR/cPLA2 signalling induced by pharmacological inhibition of cAMP/PKA in −LMN cells. The fact that cytochalasin D similarly affected β2-AR signalling enhanced by either LMN or inhibition of cAMP/PKA further supports a causal relationship between inhibition of cAMP/PKA (either by LMN or pharmacological agents) and activation of β2-AR/cPLA2 signalling. In addition, these findings indicate that activation of β2-AR/cPLA2 by inhibition of cAMP/PKA (either by LMN or pharmacological agents) is dependent on an intact actin cytoskeleton in atrial myocytes. In endothelial cells the cAMP/PKA pathway is regulated by integrin-mediated cell adhesion, and inhibition of cAMP/PKA signalling enhances actin synthesis and stress fibre formation (Whelan & Senger, 2003; Howe, 2004). Moreover, in vascular smooth muscle cells intact actin filaments are required for cPLA2 translocation (Fatima et al. 2005). We therefore speculate that LMN-mediated inhibition of cAMP/PKA alters the actin architecture to facilitate the translocation of cPLA2 to intracellular membrane sites (Gijon & Leslie, 1999). Furthermore, the fact that β2-ARs are localized within caveolae (Rybin et al. 2000) suggests that the actin cytoskeleton may facilitate cPLA2 translocation to caveolae membranes. In fact, in rat ventricular myocytes (cultured on LMN) zinterol induces translocation of cPLA2 to caveolin-3-enriched membrane fractions associated with β2-AR signalling components (Ait-Mamar et al. 2005). We therefore conclude that β2-AR/cPLA2 signalling is dependent on the actin cytoskeleton, which may facilitate the translocation of cPLA2 to β2-AR-containing caveolae. We have previously reported electron micrographs showing prominent subsarcolemmal caveolae in cat atrial myocytes (Wang et al. 2005).

In the failing heart, the ratio of β1-/β2-AR signalling decreases primarily as a result of a decrease in β1-AR signalling (Bristow et al. 1986). The heart therefore becomes more dependent on β2-AR signalling. The present results suggest that increases in extracellular matrix protein, as in fibrosis and/or hypertrophy, may enhance β2-AR signalling such that β2-AR signalling relies less on Gs/AC/cAMP/PKA and more on Gi/cPLA2/AA signalling. In this regard, β2-AR stimulation activates cPLA2 signalling in human diseased left ventricular biopsies and right atrial appendages, and this signalling mechanism is favoured in those tissues with altered AC activity (Pavoine et al. 2003). Based on the present findings, fibrosis of these diseased tissues may act via integrin-mediated signalling to inhibit cAMP/PKA and enhance β2-AR/cPLA2 signalling. It remains to be determined whether LMN-mediated changes in β2-AR signalling are beneficial or deleterious. β1-AR and β2-AR signalling exert opposing effects on cardiac cell survival where chronic stimulation of β1-ARs promote and β2-ARs inhibit cell apoptosis (Communal et al. 1999; Chesley et al. 2000). The anti-apoptotic effects of β2-AR stimulation are mediated via Gi/PI−(3)K/Akt signalling (Kennedy et al. 1997). In the present study, β2-AR/Gi activates cPLA2/AA signalling, which is involved in numerous physiological and pathophysiological mechanisms (Hirabayashi et al. 2004). In terms of pathology, cPLA2/AA signalling is associated with membrane degradation and inflammatory responses, and metabolites of AA can cause vasoconstriction, and hence compromise tissue blood flow (Bonventre, 1999). We therefore propose that in the setting of atrial fibrosis, chronic β2-AR/cPLA2 signalling may lead to atrial cell damage and inflammation. In fact, AA is reported to slow atrial conduction and has been implicated in the development of postoperative atrial fibrillation (Tselentakis et al. 2006).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant HL079038 (S.L.L.) and a grant to the Cardiovascular Institute from the Ralph and Marian Falk Trust for Medical Research (A.M.S.).

Glossary

Abbreviations

- AA

arachidonic acid

- AACOCF3

arachidonyltrifluoromethyl ketone

- AC

adenylate cyclase

- AR

adrenergic receptor

- cAMP/PKA

cAMP-dependent PKA

- BAPTA-AM

1,2-bis-(o-aminophenoxy)-ethane-N,N,N′,N′tetraacetic acid, tetraacetoxymethyl ester

- cPLA2

cytosolic phospholipase A2

- cyto D

cytochalasin D

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- fen-β2-AR

fenoterol

- FAK

focal adhesion kinase

- ICa,L

L-type Ca2+ current

- KT

KT5720

- LMN

laminin

- PI-(3)K

phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase

- PTX

pertussis toxin

- PKA

protein kinase A

- zint-β2-AR

zinterol.

Author contributions

All experiments were performed in the Department of Physiology, Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood, IL 60153. Conception and design of Experiments: M.R.P., A.M.S. & S.L.L. Collection, analysis and interpretation of data: M.R.P., X.J., A.M.S. & S.L.L. Drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content: M.R.P., A.M.S. & S.L.L. All authors approved the final version to be published.

References

- Ait-Mamar B, Cailleret M, Rucker-Martin C, Bouabdallah A, Candiani G, Adamy D, Duvaldestin P, Pecker F, Defer N, Pavoine C. The cytosolic phospholipase A2 pathway, a safeguard of β2-adrenergic cardiac effects in rat. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:18881–18890. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410305200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonventre JV. The 85-kD cytosolic phospholipase A2 knockout mouse; a new tool for physiology and cell biology. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10:404–412. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V102404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bristow MR, Ginsberg R, Umans V, Fowler M, Minobe W, Rasmussen R, Zera P, Menlove R, Shah P, Jamieson S, Stinson EB. β1- and β2-adrenergic-receptor subpopulation in nonfailing and failing human ventricular myocardium: coupling of both receptor subtypes to muscle contraction and selective β1-receptor down-regulation in heart failure. Circ Res. 1986;59:297–309. doi: 10.1161/01.res.59.3.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter SB. Effects of cytochalasins on mammalian cells. Nature. 1967;213:261–264. doi: 10.1038/213261a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesley A, Lundberg MS, Asai T, Xiao R-P, Ohtani S, Lakatta EG, Crow MT. The β2-adrenergic receptor delivers an antiapoptotic signal to cardiac myocytes through Gi-dependent coupling to phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase. Circ Res. 2000;87:1172–1179. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.12.1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chijiwa T, Mishima A, Hagiwara M, Sano M, Hayashi K, Inoue T, Naito K, Toshioka T, Hidaka H. Inhibition of forskolin-induced neurite outgrowth and protein phosphorylation by a newly synthesized selective inhibitor of cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase, N-[2-(p-bromocinnamylamino)ethyl]-5-isoquinoline sulfonamide (H-89), of PC12D pheochromocytoma cells. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:5267–5272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Communal C, Singh K, Sawyer DB, Colucci WS. Opposing effects of β1- and β2-adrenergic receptors on cardiac myocyte apoptosis: role of a pertussis toxin-sensitive G protein. Circ. 1999;100:2210–2212. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.22.2210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dedhar S. Integrins and signal transduction. Curr Opin Hematol. 1999;6:37–43. doi: 10.1097/00062752-199901000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dedkova EN, Wang YG, Blatter LA, Lipsius SL. Nitric oxide signalling by selective β2-adrenoceptor stimulation prevents ACh-induced inhibition of β2-stimulated Ca2+ current in cat atrial myocytes. J Physiol. 2002;542:711–723. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.023341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatima S, Yaghini FA, Pavicevic S, Kalyankrishna S, Jafari N, Luong E, Estes A, Malik KU. Intact actin filaments are required for cytosolic phospholipase A2 translocation but not for its activation by norepinephrine in vascular smooth muscle cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;313:1017–1026. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.081992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favata MF, Horiuchi KY, Manos EJ, Daulerio AJ, Stradley DA, Feeser WS, Van Dyk DE, Pitts WJ, Earl RA, Hobbs F, Copeland RA, Magolda RL, Scherle PA, Trzaskos JM. Identification of a novel inhibitor of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase. J Biol Chem. 1998;17:18623–18632. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.29.18623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerits N, Kostenko S, Shiryaev A, Johannessen M, Moens U. Relations between the mitogen-activated protein kinase and the cAMP-dependent protein kinase pathways: comradeship and hostility. Cell Signalling. 2008;20:1592–1607. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2008.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gijon MA, Leslie CC. Regulation of arachidonic acid release and cytosolic phospholipase A2 activation. J Leukocyte Biol. 1999;65:330–336. doi: 10.1002/jlb.65.3.330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Head BP, Patel HH, Roth DM, Murray F, Swaney JS, Niesman IR, Farquhar MG, Insel PA. Microtubules and actin microfilaments regulate lipid raft/caveolae localization of adenylyl cyclase signalling components. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:26391–26399. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602577200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirabayashi T, Murayama T, Shimizu T. Regulatory mechanism and physiological role of cytosolic phospholipase A2. Biol Pharm Bull. 2004;27:1168–1173. doi: 10.1248/bpb.27.1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe AK. Regulation of actin-based cell migration by cAMP/PKA. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1692:159–174. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2004.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang JM, Xian H, Bacaner M. Long-chain fatty acids activate calcium channels in ventricular myocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:6452–6456. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.14.6452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynes RO. Integrins: versatility, modulation, and signalling in cell adhesion. Cell. 1992;69:11–25. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90115-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kase H, Iwahashi K, Nakanishi D, Matsuda Y, Yamada K, Takahashi M, Murakata C, Sato A, Kaneko M. K-252 compounds, novel and potent inhibitors of protein kinase C and cyclic nucleotide-dependent protein kinases. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 1987;142:436–440. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(87)90293-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy SG, Wagner AJ, Conzen SD, Jordan J, Bellacosa A, Tsichlis PN, Hay N. The PI 3-kinase/Akt signalling pathway delivers an anti-apoptotic signal. Genes Dev. 1997;11:701–713. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.6.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilts JD, Gerhardt MA, Richardson MD, Sreeram G, Mackensen GB, Grocott HP, White WD, Davis RD, Newman MF, Reves JG, Schwinn DA, Kwatra MM. β2-adrenergic and several other G protein-coupled receptors in human atrial membranes activate both Gs and Gi. Circ Res. 2000;87:705–709. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.8.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiuchi K, Shannon RP, Komamura K, Cohen DJ, Bianchi C, Homcy CJ, Vatner SF, Vatner DE. Myocardial β-adrenergic receptor function during the development of pacing-induced heart failure. J Clin Invest. 1993;91:907–914. doi: 10.1172/JCI116312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leslie CC. Regulation of the specific release of arachidonic acid by cytosolic phospholipase A2. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2004;70:373–376. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2003.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magne S, Couchie D, Pecker F, Pavoine C. β2-adrenergic receptor agonists increase intracellular free Ca2+ concentration cycling in ventricular cardiomyocytes through p38 and p42/44 MAPK-mediated cytosolic phospholipase A2 activation. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:39539–39548. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100954200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundgren E, Gullberg D, Rubin K, Borg TK, Terracio MJ, Terracio L. In vitro studies on adult cardiac myocytes:attachment and biosynthesis of collagen type IV and laminin. J Cell Physiol. 1988;136:43–53. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041360106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavoine C, Behforouz N, Gauthier C, LeGouvello S, Roudot-Thoraval F, Martin CR, Pawlak A, Feral C, Defer N, Houel R, Magne S, Amadou A, Loisance D, Duvaldestin P, Pecker F. β2-adrenergic signalling in human heart: shift from the cyclic AMP to the arachidonic acid pathway. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;64:1117–1125. doi: 10.1124/mol.64.5.1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavoine C, Magne S, Sauvadet A, Pecker F. Evidence for a β2-adrenergic/arachidonic acid pathway in ventricular cardiomyocytes. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:628–637. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.2.628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riendeau D, Guay J, Weech PK, Laliberte F, Yergey J, Li C, Desmarais S, Perrier H, Liu S, Nicoll-Griffith D. Arachidonyl trifluoromethylketone, a potent inhibitor of 85-kDa phospholipase A2, blocks production of arachidonate and 12-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid by calcium ionophore-challenged platelets. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:15619–15624. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rybin VO, Xu X, Lisanti MP, Steinberg SF. Differential targeting of β-adrenergic receptor subtypes and adenylyl cyclase to cardiomyocyte caveolae. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:41447–41457. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006951200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz MA, Schaller MD, Ginsberg MH. Integrins: emerging paradigms of signal transduction. Ann Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1995;11:549–599. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.11.110195.003001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terracio L, Rubin K, Gullberg D, Balog E, Carver W, Jyring R, Borg TK. Expression of collagen binding integrins during cardiac development and hypertrophy. Circ Res. 1991;68:734–744. doi: 10.1161/01.res.68.3.734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tselentakis EV, Woodford E, Chandy J, Gaudette GR, Saltman AE. Inflammation effects on the electrical properties of atrial tissue and inducibility of postoperative atrial fibrillation. J Surg Res. 2006;135:68–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2006.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang YG, Dedkova EN, Ji X, Blatter LA, Lipsius SL. Phenylephrine acts via IP3-dependent NO release to stimulate L-type Ca2+ current in atrial myocytes. J Physiol. 2005;567:143–157. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.090035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang YG, Dedkova EN, Steinberg SF, Blatter LA, Lipsius SL. β2-adrenergic receptor signalling acts via NO release to mediate ACh-induced activation of ATP-sensitive K+ current in cat atrial myocytes. J Gen Physiol. 2002;119:69–82. doi: 10.1085/jgp.119.1.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang YG, Ji X, Pabbidi M, Samarel AM, Lipsius SL. Laminin acts via focal adhesion kinase/phosphotidyinositol-3′ kinase/protein kinase B to down-regulate β1-adrenergic receptor signalling in cat atrial myocytes. J Physiol. 2009;587:541–550. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.163824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang YG, Samarel AM, Lipsius SL. Laminin acts via β1 integrin signalling to alter cholinergic regulation of L-type Ca2+ current in cat atrial myocytes. J Physiol. 2000a;526:57–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-1-00057.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang YG, Samarel AM, Lipsius SL. Laminin binding to β1-integrins selectively alters β1- and β2-adrenoceptor signalling in cat atrial myocytes. J Physiol. 2000b;527:3–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-2-00003.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whelan MC, Senger DR. Collagen I initiates endothelial cell morphogenesis by inducing actin polymerization through suppression of cyclic AMP and protein kinase A. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:327–334. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207554200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao Y-F, Gomez AM, Morgan JP, Lederer WJ, Leaf A. Suppression of voltage-gated L-type Ca2+ currents by polyunsaturated fatty acids in adult and neonatal rat ventricular myocytes. Proc Nat Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:4182–4187. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.4182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]