Abstract

The use of α-synuclein immunohistochemistry has altered our concepts of the cellular pathology, anatomical distribution and prevalence of Lewy body disorders. However, the diversity of methodology between laboratories has led to some inconsistencies in the literature. Adoption of uniformly sensitive methods may resolve some of these differences. Eight different immunohistochemical methods for demonstrating α-synuclein pathology, developed in eight separate expert laboratories, were evaluated for their sensitivity for neuronal elements affected by human Lewy body disorders. Identical test sets of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded sections from subjects diagnosed neuropathologically with or without Lewy body disorders were stained with the eight methods and graded by three observers for specific and nonspecific staining. The methods did not differ significantly in terms of Lewy body counts, but varied considerably in their ability to reveal neuropil elements such as fibers and dots. One method was clearly superior for revealing these neuropil elements and the critical factor contributing to its high sensitivity was considered to be its use of proteinase K as an epitope retrieval method. Some methods, however, achieved relatively high sensitivities with optimized formic acid protocols combined with a hydrolytic step. One method was developed that allows high sensitivity with commercially available reagents.

Introduction

The discovery of a mutation in the gene for α-synuclein in familial Parkinson’s disease [42] has brought intense attention to the synucleins, and particularly α-synuclein. It was subsequently shown that α-synuclein is a major constituent of Lewy bodies [46] and glial cytoplasmic inclusions (GCIs) [45, 50], the pathognomonic microscopic lesions of Lewy body disorders and multiple system atrophy, respectively. Although normally a monomeric, unfolded protein, α-synuclein aggregates into a β-pleated sheet conformation in vitro and within Lewy bodies and GCIs [5, 23, 24, 48]. It appears likely that these insoluble aggregates eventually lead to cell death and clinically manifest disease [48]. Additionally, more recent evidence has suggested that abnormal nitration [13, 19] and/or phosphorylation [17, 43] of α-synuclein may be critical to disease development.

The relative specificity of α-synuclein immunohistochemical staining for Lewy bodies and GCIs has made this the method of choice for the neuropathological diagnosis of Lewy body disorders and multiple system atrophy [3, 34, 45]. The increasingly sensitive methods employed have revealed that, besides forming the classic Lewy bodies, α-synuclein accumulates pathologically in neuronal somata in granular or diffuse form, perhaps representing “pre-Lewy bodies” [15, 43]. Furthermore, α-synuclein is much more abundant than previously realized in neuronal processes, forming dense neuropil networks that collectively dwarf the cell body deposits [25, 43]. These improved methods have altered our concepts of the cellular and anatomical distribution as well as the prevalence of Lewy body disorders [9, 11, 15, 18, 28, 30, 31, 36, 44]. However, the diversity of methodology between laboratories has led to some inconsistencies in the literature, regarding abundance, prevalence and distribution of α-synuclein pathology [21, 22, 40, 49].

We therefore endeavored to test several different immunohistochemical methods with the objective of identifying a highly sensitive technique that might then be widely adopted by the research community, allowing both greater sensitivity and more uniform results between laboratories. Eight expert investigators were invited to participate, based on their published work using α-synuclein immunohistochemistry. The investigators were asked to stain identical sets of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded sections with their own optimized method. The host lab then adapted the best method for general use by employing all commercially available reagents. Three separate observers graded the staining in all sets using a standardized method.

Materials and methods

Human subjects

Brain tissue utilized in the study was obtained from Sun Health Research Institute (SHRI), which is part of a nonprofit, community-owned and operated health care provider located in the Sun Cities retirement communities of northwest metropolitan Phoenix, Arizona. Sun Health Research Institute and the Mayo Clinic Arizona are the principal institutional members of the Arizona Parkinson’s Disease Consortium. Brain necropsies were performed on elderly subjects who had volunteered for the SHRI Brain Donation Program. Brain Donation Program subjects are clinically characterized at SHRI with annual standardized functional, neuropsychological and neuromotor assessments. The Brain Donation Program has been approved by the Institutional Review Board of Sun Health Research Institute. Subjects were chosen by searching the Brain Donation Program Database. Two cases previously recorded as having no positive α-synuclein staining were chosen as negative controls while five cases with varying densities of synuclein pathology and varying diagnoses (Table 1) were chosen to assess the sensitivity of the methods.

Table 1.

Characteristics of subjects used for the test set of sections

| Case # | PMI (h) | Clinical Dx | Neuropath Dx | NP density | Braak NF stage | Lewy body stage (DLB consortium III) | Likelihood that dementia is due to Lewy pathology |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 05–10 | 1.5 | Normal | Normal | Zero | II | No Lewy bodies | NA |

| 05–14 | 4 | Normal | Arg grns | Zero | IV | No Lewy bodies | NA |

| 03–50 | 3.3 | Tremor | ILBD, arg grns | Sparse | III | Brainstem predominant | NA |

| 03–51 | 2.3 | PD, dementia | PD | Zero | II | Neocortical | High |

| 02–15 | 3.5 | PD, dementia | PD | Sparse | III | Neocortical | High |

| 04–25 | 1.6 | DLB, AD | AD, DLB | Moderate | V | Neocortical | Intermediate |

| 04–63 | 22.5 | AD | AD, DLB | Frequent | VI | Neocortical | Intermediate |

PD Parkinson’s disease, DLB dementia with Lewy bodies, AD Alzheimer’s disease, ILBD incidental Lewy body disease, arg grns argyrophilic grains, NP neuritic plaque, PMI postmortem interval

Preparation of test sets

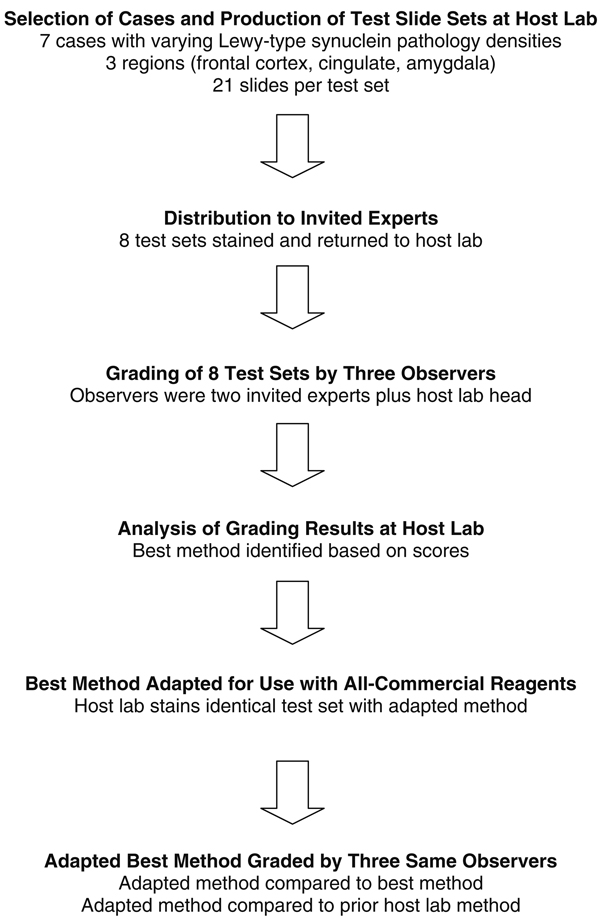

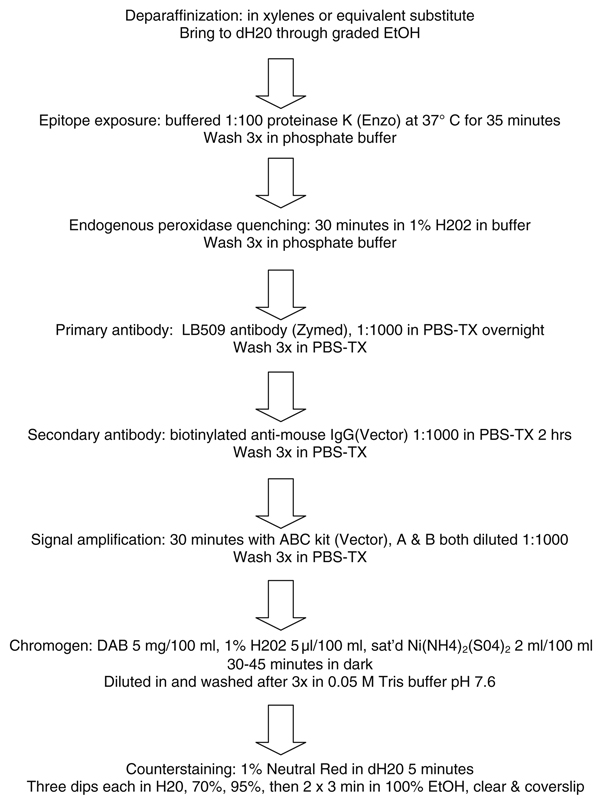

Tissue processing was done according to the standard protocol for the Brain Donation Program [7]. Tissue blocks were fixed in 10% formalin for 48 h, embedded in paraffin and cut at 6 µm. One case was fixed for 2 weeks in 10% formalin. Each investigator was issued an initial training set of unstained paraffin slides from a case with dense synucleinopathy, to optimize their method with the tissue. They were then sent a complete test set, consisting of 6 µm sections from each of three blocks from the seven chosen cases. The three blocks were from middle frontal gyrus, cingulate gyrus and amygdala. The investigators were asked to stain the sections with their optimized method and then return the slides for grading. The design of the study is depicted diagrammatically in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart depicting study design

Grading method and statistical analysis

All eight sets of test sections stained by the invited experts were graded by three observers (TGB, CLW, RLH). The two negative control cases (cases without α-synuclein pathology) were graded first. Any staining on the negative controls was defined as nonspecific, as these cases contained no Lewy-related α-synuclein pathology on the initial diagnostic work-up and this was later confirmed on all of the eight test sets.

Nonspecific staining was graded in two ways, depending on whether the nonspecifically stained elements were diffuse or discrete in nature. Diffuse nonspecific staining was defined as staining of relatively large areas of the tissue section without regard to microanatomical features. Staining limited to the section edge only, a common finding, was given grade 1, while staining that extended into the interior of the section was graded for greatest intensity using a modification of the DLB Consortium (III) criteria [34] as a gray scale, resulting in scores ranging from 0 to 3 (zero, mild, moderate and severe; grades 3 and 4 from the Consortium templates were both rated as grade 3). Diffuse nonspecific staining was graded at low magnification, using the 4× objective. A score was assigned for each brain region. Discrete nonspecific staining was defined as staining of distinctive microanatomical features, such as nuclei, lipofuscin, astrocytes and corpora amylaceae. Discrete nonspecific staining was also graded from 0 to 3 for density with the modified DLB Consortium templates, using the 20× objective at the point of maximum density. Diffuse and discrete nonspecific staining scores from each brain region were added to provide a sum total, for each observer, for each of the two negative control cases. The scores from the three observers were then averaged to provide a final nonspecific staining score for each staining method evaluated.

Positive staining was also graded in two ways, using Lewy body counts and estimates of the total density of α-synuclein-immunoreactive elements, including Lewy bodies, pre-Lewy bodies, dots and fibers. This was termed “total synuclein pathology burden score.” For the purposes of this experiment, glial staining was regarded as nonspecific, as it was only observed with some of the methods, and was only observed on negative control slides. The total synuclein pathology burden, representing all of these features, was graded from 0 to 3 (none, mild, moderate, severe) at the point of maximum intensity with the 20× objective using the modified DLB Consortium templates. For Lewy body counts, the section was first examined using the 4× or 10× objective to determine three sites where Lewy bodies appeared to be most densely clustered. The number of Lewy bodies in a single 40× objective/10× ocular field at these three sites was then counted. The highest count obtained was then recorded for that brain region. For both total synuclein pathology burden scores and Lewy body counts, the scores from all three observers were averaged to obtain single scores for each staining method and brain region. For the total synuclein pathology burden, a single overall score was also obtained by adding the scores from each area, from each observer and taking the average of these.

Differences between test sets were assessed using repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) and post-hoc paired significance testing (Tukey), with appropriate corrections for multiple comparisons.

Staining protocols evaluated

The protocols for the eight staining methods initially evaluated by the three observers are described in detail in the supplementary data section available online and are also summarized in Table 2. Also available online are the two additional host lab methods evaluated in the second stage of the study. These are the original host lab method and the host lab method after adoption of features of the best method from the original eight (Fig. 1). Methods 1 and 2 used automated immunostainers, while all others were performed manually.

Table 2.

Summary of the eight initially evaluated, expert-performed α-synuclein staining protocols (1–8), as well as the two host lab methods (9, 10)

| Method (Lab) | Epitope exposure | Primary antibody | Chromogen system |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (DWD) | 98% FA, hydrolysis | NACP98 | Labeled polymer/HRP/DAB |

| 2 (CLW) | Proteinase K, hydrolysis | LB509 | Ventana Kit/Ultravue Red |

| 3 (RLH) | Type XXIV proteinase | LB509 | ABC/DAB |

| 4 (TI) | None | PSyn#64 (phosphorylated α-syn) | ABC/DAB |

| 5 (FR) | 100% FA | BD Transduction Labs | ABC/DAB |

| 6 (JED) | 88% FA, hydrolysis | Syn 303 | ABC/DAB |

| 7 (JBL) | 88% FA | Syn 303 (oxidized α-syn) | ABC/DAB |

| 8 (MB) | 88% FA | 11A5 (phosphorylated α-syn) | ABC/DAB |

| 9 (TGB) | 80% FA | LB509 | ABC/DAB |

| 10 (TGB) | Proteinase K | LB509 | ABC/DAB |

See online supplementary data section for detailed descriptions

Initials given within parentheses in the first column are those of investigators’ contributing the methods

FA formic acid

Results

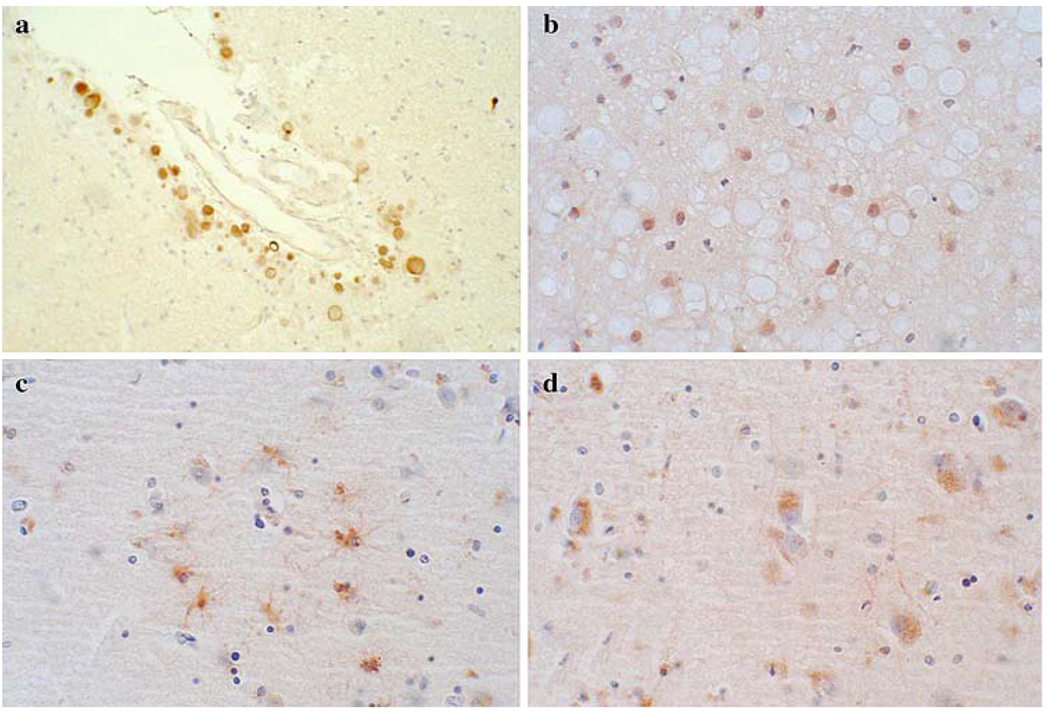

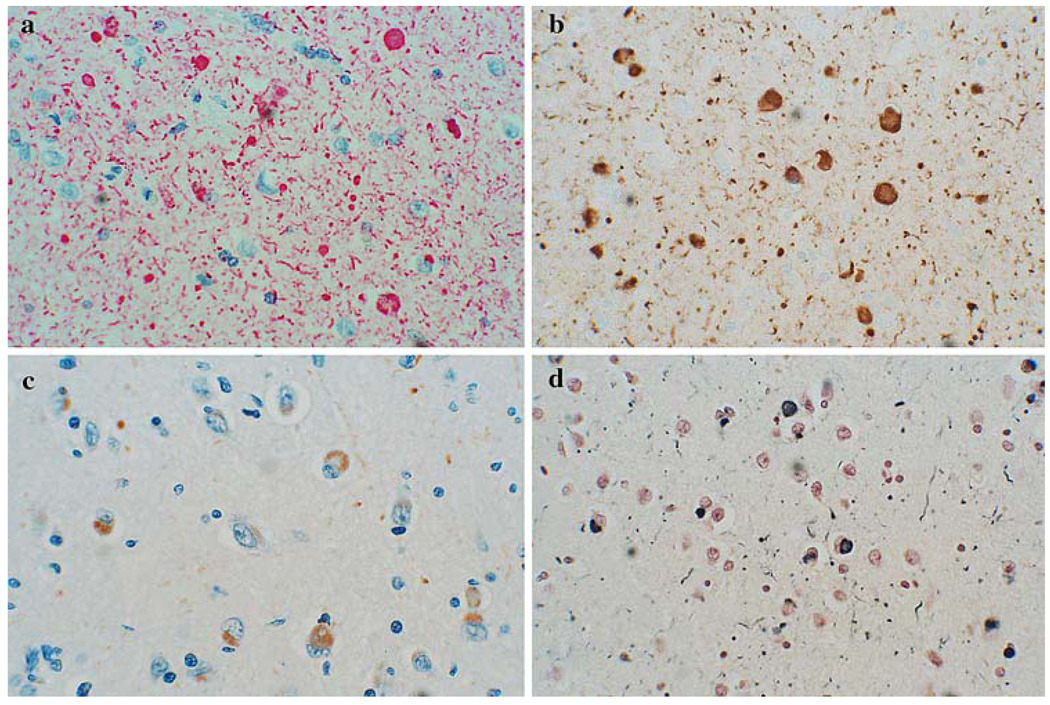

All methods had some nonspecific staining. Examples of some of the nonspecific staining are shown in the photomicrographs in Fig. 2. Both diffuse and discrete types of non-specific staining were common. Amongst discrete elements nonspecifically stained, corpora amylacea and lipofuscin were particularly common. Both of these made detection of genuine synuclein pathology much more difficult, as it was often necessary to go to high magnification to determine whether the staining represented Lewy bodies, pre-Lewy body cytoplasmic accumulations or not. Glial staining was present in only two methods and was regarded as nonspecific, since it was only seen in the negative control slides, in the absence of Lewy-type morphological features (i.e. no Lewy bodies or typical Lewy neurites). However, it is still possible that glia may be specifically involved in Lewy body disorders. This question was not specifically addressed in the present study.

Fig. 2.

Photomicrographs depicting some types of nonspecific staining seen with some of the methods. Corpora amylacea were stained in some methods, including Method 5 (a), glial nuclei were seen in some methods, including Method 4 (b), astrocytes in some methods, including Method 3 (c) and lipofuscin in several methods, including Method 3 (d)

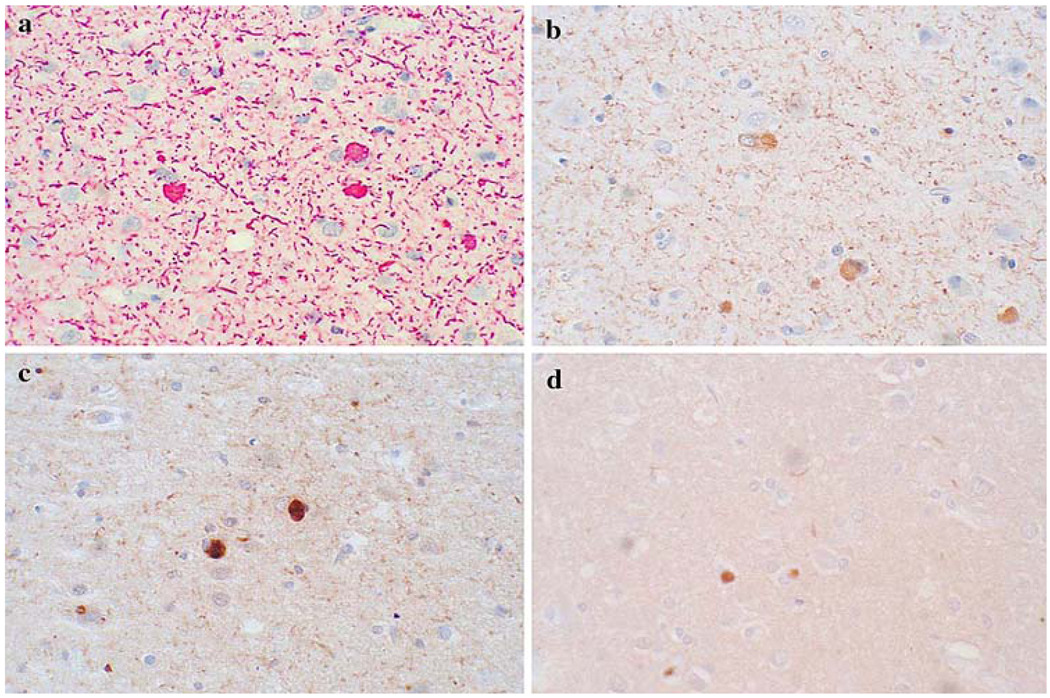

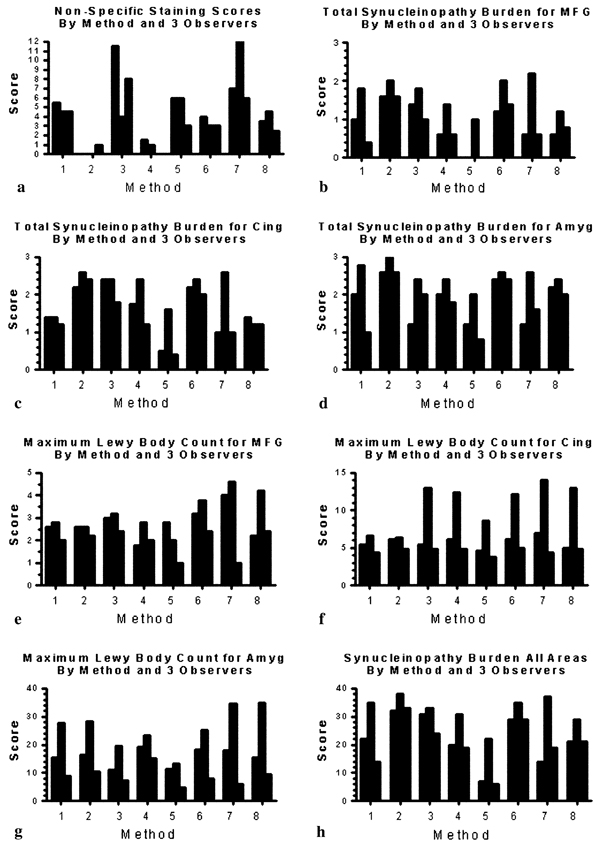

Positive or specific staining varied considerably amongst the eight methods (Fig. 3). The total synuclein pathology burden, consisting of Lewy bodies, fibers and dots (presumably neuronal axons, dendrites and presynaptic terminals, respectively, although the possibility that some of these might represent glial fibers cannot be excluded), as estimated using the modified DLB Consortium templates, difiered significantly in all three brain regions between the eight methods. The mean nonspecific and specific staining scores for each method and observer are depicted in Fig. 4 and Table 3. Scores differed significantly between methods (repeated measures ANOVA, P < 0.001, Table 3). Methods 2 and 4 had the least amounts of nonspecific staining. Where neuropil elements were scarce, such as in the middle frontal gyrus, the differences in positive staining were most marked. Method 2 had the highest mean score for total synuclein pathology burden in all three regions, with Method 6 scoring second-best in all regions (Fig. 4b–d). When the summary synuclein pathology burden scores for all three brain regions were compared (Fig. 4h), Methods 2 and 6 again were ranked first and second, respectively.

Fig. 3.

Photomicrographs from cingulate gyrus of the same case, showing the range of variation in positive or specific staining obtained by different methods. The four methods depicted represent a range of staining densities, in terms of the total α-synuclein pathology burden. Method 2 (a) was graded at 2.3, Method 3 (b) received a grade of 2.2, Method 4 (c) was graded 1.8 and Method 5 was graded 0.8, on a scale of 0–3 (none, mild, moderate, severe; see “Materials and methods” for details)

Fig. 4.

Graphs comparing nonspecific and specific staining scores obtained by the eight methods and three observers

Table 3.

Mean scores for nonspecific and specific staining by region and method

| Method 1 | Method 2 | Method 3 | Method 4 | Method 5 | Method 6 | Method 7 | Method 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-speca | 4.8 (0.7) | 0.3 (0.6) | 7.8 (3.7) | 0.8 (0.8) | 5.0 (1.7) | 3.3 (0.6) | 8.3 (0.6) | 3.5 (0.6) |

| SynMFGb | 1.1 (0.7) | 1.7 (0.2) | 1.4 (0.4) | 0.9 (0.5) | 0.3 (0.6) | 1.5 (0.4) | 1.1 (0.9) | 0.9 (0.3) |

| SynCingc | 1.3 (0.1) | 2.4 (0.2) | 2.2 (0.3) | 1.8 (0.6) | 0.8 (0.7) | 2.2 (0.2) | 1.5 (0.9) | 1.3 (0.1) |

| SynAmyd | 1.9 (0.9) | 2.7 (0.2) | 1.9 (0.6) | 2.1 (0. 3) | 1.3 (0.6) | 2.5 (0.6) | 1.8 (0.1) | 2.2 (0.2) |

| SynAlle | 23.7 (10.6) | 34.3 (3.2) | 29.3 (4.7) | 23.3 (6.7) | 16.7 (9.0) | 31 (3.5) | 23.3 (12.1) | 23.4 (4.6) |

| LBMFG | 2.5 (0.4) | 2.5 (0.2) | 2.9 (0.4) | 2.2 (0.5) | 1.9 (0.9) | 3.1 (0.7) | 3.2 (1.9) | 2.9 (1.1) |

| LBCing | 5.5 (1.1) | 5.8 (0.9) | 7.7 (4.6) | 7.8 (4.0) | 5.7 (2.6) | 7.8 (3.9) | 8.5 (5.0) | 7.6 (4.7) |

| LBAmyg | 17.4 (9.6) | 18.4 (9.2) | 12.6 (6.3) | 19.2 (4.0) | 9.9 (4.5) | 17.1 (8.8) | 19.6 (14.3) | 20.1 (13.3) |

Standard deviations are in parentheses

Nonspecific staining scores and total synuclein pathology burdens differed significantly between methods while Lewy body counts did not (see table legend for details)

Syn total synuclein pathology burden score, MFG middle frontal gyrus, Cing cingulate gyrus, Amy amygdala, non-spec non-specific staining score, SynAll mean of sum of scores from all three regions for all five cases, LB Lewy body density scores

Scores differed significantly between methods (ANOVA P < 0.001); Methods 2 and 4 had significantly lower scores than Methods 3 and 7 (Tukey P < 0.01)

Scores differed significantly between methods (ANOVA P < 0.004); Method 2 had a significantly greater score than Method 5 (Tukey P < 0.001) and Methods 4 and 8 (P < 0.05); Methods 3, 6 and 7 had significantly greater scores than Method 5 (Tukey P < 0.01)

Scores differed significantly between methods (ANOVA P < 0.001); Method 2 had significantly greater scores than Method 5 (Tukey P < 0.01) and Methods 1 and 8 (Tukey P < 0.05); Methods 2, 3 and 6 had significantly greater scores than Method 5 (Tukey P < 0.01)

Scores differed significantly between methods (ANOVA P < 0.01); Methods 2 and 6 had significantly greater scores (Tukey P < 0.01 and 0.05, respectively) than Method 5

Scores differed significantly between methods (ANOVA P < 0.0003); Method 5 had a significantly lower score than all other methods (Tukey P < 0.001 for Methods 2 and 6, P < 0.01 for Method 3, P < 0.05 for Methods 1, 4, 7 and 8)

Quantification showed considerable variability between methods in terms of maximum Lewy body counts per high-power field (Fig. 4e–g). However, statistical tests (repeated measures ANOVA) indicated that the differences were, except in the amygdala (P = 0.07), far below the significance level (Table 3). The highest Lewy body counts were obtained with Methods 6, 7 and 8.

Considering performance in both specific and nonspecific staining, Method 2 was considered to be the best, as it had the lowest scores for nonspecific staining and the highest scores for total synuclein pathology burden in all three regions. Qualitatively, all three observers agreed that Method 2 had a superior appearance. While Method 2 was only average in terms of maximizing Lewy body count, this result must be accorded less weight given that the differences between methods were not statistically significant for Lewy body counts. This may be due to less reliability in the Lewy body count data as compared with the synuclein pathology burden data, particularly in the amgydala, where the very high Lewy body density, ranging up to 93 per high-power field, made an accurate estimate difficult. It is also possible that Lewy bodies, due to their relatively large size and high α-synuclein concentrations, may be easier to detect than neuropil elements such as dots and fibers. Method 6 was clearly the second-best method, scoring second in terms of total synuclein pathology burden in all three regions and second in Lewy body counts in two regions. Interobserver correlations were high for both total synuclein pathology burden and maximum Lewy body counts (Table 4).

Table 4.

Interobserver correlations for total synuclein pathology burden scores and Lewy body counts

| Observer 1 versus 2 | Observer 2 versus 3 | Observer 1 versus 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Synuclein burden | R = 0.75 (P < 0.0001) | R = 0.77 (P < 0.0001) | R = 0.89 (P < 0.0001) |

| Lewy body counts | R = 0.83 (P < 0.0001) | R = 0.76 (P < 0.0001) | R = 0.86 (P < 0.0001) |

Methods 9 and 10 (Table 2) were conducted to compare the original host lab method (Method 9) with an adaptation of that method (Method 10), substituting proteinase K digestion (taken from Method 2) for formic acid pretreatment. Method 10 (Fig. 5) also utilized lower DAB and hydrogen peroxide concentrations (to minimize nonspecific staining), and nickel ammonium sulfate-enhancement of the DAB development. The section sets were graded for total synuclein pathology burden in the same manner and by the same three observers as for Methods 1–8. Method 9, with 80% formic acid as the pretreatment, had scores (Table 3, Table 5) that would have placed it seventh, in terms of total synuclein pathology burden, of the eight expert-performed methods initially tested. Method 10, with proteinase K and nickel ammonium sulfate DAB enhancement, had a roughly 30% greater total synuclein pathology burden score and would have placed third out of the initial eight methods. Method 9 detected only 59% of the synucleinopathy burden detected by Method 2, while for Method 10 this improved to 87%. The nonspecific staining score was decreased to near zero with Method 10, probably due to the use of lower DAB and hydrogen peroxide concentrations. Photomicrographs comparing Methods 2 (best of the initial eight methods), Method 6 (second-best of the initial eight methods), Method 9 (original host lab method) and Method 10 (adapted host lab method) are shown in Fig. 6.

Fig. 5.

Flow chart for method 10, showing high sensitivity, and performed with all commercial reagents

Table 5.

Comparison of total synuclein pathology burden scores obtained with Method 2, which had the highest score of the eight expert-performed methods, Method 9, the original host lab method, and Method 10, adapted from Methods 2 and 9, employing proteinase K pretreatment and nickel ammonium sulfate DAB enhancement

| Method 2 | Method 9 | Method 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-spec | 0.3 (0.6) | 3.17 (1.53) | 0.76 (1.32) |

| SynMFG | 1.7 (0.2) | 0.47 (0.46) | 0.87 (0.11) |

| SynCing | 2.4 (0.2) | 1.9 (0.46) | 2.2 (0.35) |

| SynAmy | 2.7 (0.2) | 2.13 (0.47) | 2.8 (0.35) |

| SynAl | 34.3 (3.2) | 20.3 (10.4) | 30.0 (5.2) |

Standard deviations are in parentheses

MFG middle frontal gyrus, Cing cingulate gyrus, Amy amygdala, syn total synuclein pathology burden score, SynAll mean of sum of scores from all three regions for all five cases

Fig. 6.

Photomicrographs comparing immunohistochemical staining for α-synuclein in amygdala from the same case, from the two highest scoring methods, Method 2 (a) and Method 6 (b), from the original host lab method (c) and the host lab method adapted by employing proteinase K pretreatment and nickel ammonium sulfate DAB enhancement (d). The total synuclein pathology scores for a–d were, respectively, 2.7, 2.5, 2.1 and 2.8, on a scale of 0–3 (none, mild, moderate, severe; see “Materials and methods” for details)

Discussion

Methods for α-synuclein immunohistochemistry have evolved over the past 10 years, based on the generation of new antibodies, new epitope retrieval methods and new signal generation systems. Also, research into pathological alterations of α-synuclein structure have brought the promise of pathology-specific antibodies, such as those directed against nitrated [13, 19] or phosphorylated forms [17, 43] of the protein as well as other antibodies that may be raised to preferentially recognize pathological α-synuclein [18]. The resultant increased sensitivity of these methods have shown that α-synuclein pathology extends far beyond the Lewy body, permeating the neuropil not only as the familiar misshapen Lewy-related neurites, but also as innumerable fine threads and dots, presumably representing pathologically affected axons, dendrites and presynaptic nerve terminals. This revelation is analogous to the earlier discovery of dense networks of neuropil threads in Alzheimer’s disease [10, 26]. New staging protocols for α-synuclein pathology in Lewy body disorders [11, 33, 34] have incorporated density estimates of neuropil pathology, and therefore, it is now essential that investigators have methods that are sensitive enough for their detection. Older staging protocols were based on Lewy body counts [35], and as a result, some investigators actually optimized their methods to suppress the staining of neuropil elements, to better see and count the Lewy bodies. While these methods may still be of use, it seems that a more complete demonstration of the full range of pathology will lead to a greater understanding of the temporal and anatomical progression of Lewy body disorders. Additionally, this investigation suggests that semiquantitative grading based on the DLB consortium templates [34] will be more reliable than Lewy body counting methods [35].

Prior publications have addressed specifically, and in more depth, the interlaboratory consistency of various α-synuclein methods [1, 12, 39]. These publications used different antibodies from the present study, except for the LB509 antibody (used in Methods 2, 3, 9 and 10 of the present study) and the BD Transduction Laboratories antibody (used in Method 5 of the present study). The BD Transduction Laboratories antibody was used in the study of Croisier et al. [12], where it was found to be the most sensitive of commercially available antibodies tested. As different rating methods were used between these studies, it is diffcult to compare results. However, it is noted that the LB509 antibody, which was used by the best method in the present study, did not perform so well in the study of Alafuzoff et al. None of these prior studies tested methods utilizing proteinase K pretreatment; formic acid was the standard pretreatment for all tested methods.

In designing the present study, it was considered important to test for both specific staining and nonspecific staining. Nonspecific staining makes it difficult for the observer to grade the density of stained structures. To define the presence of nonspecific staining, two of the cases chosen for the staining test had no Lewy-type synuclein pathology on initial workup at the host lab, that is, there were no Lewy bodies or Lewy-related neurites, based on morphological criteria, with H&E stains, thioflavine S stains or immunohistochemical staining for α-synuclein. This was subsequently confirmed after staining of the test sets by all eight of the invited experts. Therefore, we considered any staining seen in these “negative-control” slides as “nonspecific” in the sense that it was not likely to represent a Lewy-type pathological phenomenon. This is not meant to imply that staining in these sections did not represent α-synuclein immunoreactivity; in fact, it was expected, based on our own experience and from published studies, that there would be some diffuse or punctate staining of neuropil representing normal presynaptic terminals. Several methods did show such staining in the negative control slides. It was considered, however, that the ideal stain for identifying pathological α-synuclein would not stain structures containing normal synuclein, and therefore, methods that identified normal structures in the negative control slides were marked down for this. Nevertheless, the possibility still exists that α-synuclein may accumulate in astrocytes, presynaptic terminals or other normal anatomic structures as part of a pathological process, and that this might be detectable by some antibodies and not others.

The results indicate that a high level of sensitivity was obtained using several different methods, but one method clearly had the best overall performance. Method 2 [25] was qualitatively and quantitatively judged to be the single best method by all three observers. As Method 2 used one of the most commonly used, commercially available α-synuclein antibodies, LB509, the advantage of the method was considered to be due to the use of proteinase K for antigen retrieval. Proteinase K has previously been used to enhance immunoreactivity for α-synuclein [37, 47], but is not commonly used. Formic acid has become the standard epitope retrieval method used for α-synuclein immunohistochemistry, as exemplified by the current study, where five of the eight expert-performed methods used formic acid. Earlier publications used both formic acid and proteinase K to enhance α-synuclein immunoreactivity, but a detailed quantitative comparison between the two methods has not been performed [37, 47], although one earlier report has addressed this with preliminary data [25]. The results of the present study, in which this direct comparison was performed (comparing Methods 9 and 10), strongly suggest that proteinase K is superior to formic acid for the demonstration of α-synucleinopathy associated with Lewy body disorders and that most protocols could probably be improved by switching from formic acid to proteinase K. Nevertheless, optimization of methods using formic acid may result in high sensitivity, as shown by Method 6 and other reports [43].

In terms of nonspecific staining, Method 2 was again the best method, with virtually no staining on the negative control slides. This may be due to the use of proteinase K as the pretreatment, in that proteinase K may completely break down normal synuclein, sparing aggregated synuclein, analogously to the way proteinase K breaks down normal prion protein, but spares aggregated prion protein. Method 6 had some diffuse neuropil staining that may represent either normal presynaptic terminals, as has been reported previously [15], or nonspecific staining. While the Syn 303 antibody used by this method was raised against oxidized α-synuclein, it is not specific to oxidized or nitrated α-synuclein, so that the diffuse staining with this antibody is likely to be normal synaptic terminal staining. Some of the methods, however, almost certainly had nonspecific staining, as lipofuscin, nuclei and corpora amylacea probably do not have significant α-synuclein content. The staining of astrocytic cytoplasm seen with Method 3 might represent normal or pathological glial α-synuclein immunoreactivity or nonspecific staining. The possibility that some α-synuclein immunostaining protocols may stain astrocytes nonspecifically encourages the use of several α-synuclein antibodies in future investigations of α-synuclein accumulations in glial cells.

As the best (Method 2) and second-best (Method 6) of the eight expert-performed methods use proprietary or private reagents, we attempted to replicate the sensitivity of these methods using proteinase K pretreatment and all commercially available reagents. This resulted in a stain (Method 10) with high sensitivity that would be available to all investigators. Method 10 had 87% of the sensitivity of Method 2, in terms of the total synuclein pathology burden scores. In addition to proteinase K and formic acid epitope retrieval, respectively, Methods 2 and 6 both employed a hydrolytic epitope retrieval step (high-temperature aqueous buffer exposure), and therefore, the addition of a hydrolytic step to Method 10 might further increase its sensitivity. It seems probable that the chromogen used in Method 2 contributed significantly to its superior sensitivity, as the bright red color and tendency for slight spatial spreading (making fibers and dots larger) results in a striking image and there is virtually no nonspecific staining. This, however, is a proprietary compound available only to investigators who purchase a Ventana autostainer and is thus unfortunately not within the budget of many investigators. As the color development in this chromogen is based on alkaline phosphatase coupled with Fast Red, a similar result might be obtained using common commercial reagents. Those who wish to continue using DAB should be able to increase sensitivity by using nickel ammonium sulfate enhancement and should be able to reduce or eliminate nonspecific staining by developing longer with greatly reduced concentrations of DAB and hydrogen peroxide, as employed in Method 10.

Some previous investigations have suggested that different epitope specificities might underlie differing sensitivities for the demonstration of synucleinopathy [12, 14, 20, 29] or that antibodies raised against pathologically altered α-synuclein [13, 17, 19] might have greater sensitivity for the affected neural elements. This study did not systematically test antibodies based on epitope specificity but does provide limited support to an earlier suggestion [14] that antibodies that recognize epitopes nearer to the carboxyl terminus of the protein are more sensitive, as the antibody used by the most sensitive technique, Method 2, was the LB509 antibody, which recognizes amino acids 115–122. This study also did not systematically investigate whether antibodies raised against abnormally modified α-synuclein are more sensitive, but again there is limited support for this concept, as antibody Syn 303, raised against oxidized α-synuclein [13, 19], was used in Methods 3 and 6, both of which were amongst the most sensitive methods. It is likely that Method 4, which used an antibody specific for phosphorylated α-synuclein [17] without any epitope retrieval, was not adequately tested by this study, as previous publications using this antibody have demonstrated profuse neuropil networks [43].

As this study was intended to be of wide relevance for both research and diagnostic laboratories, only paraffin-embedded tissue was tested. It is recognized that neither formalin fixation (especially prolonged formalin fixation, i.e. more than 2 or 3 days) or paraffin embedding are optimal processing methods for immunohistochemistry, due to chemical and heat-induced protein crosslinkage that requires subsequent epitope retrieval [4, 8, 32, 41]. Several investigators have achieved high sensitivity using alternative fixatives, such as ethanol, and/or alternative embedding (e.g. polyethylene glycol) and sectioning methods, such as vibratome or freezing microtome [2, 6, 11, 27, 28, 38]. The best of the methods evaluated here, however, appear to have sensitivities, in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue, that are equal to those achieved with these alternative processing techniques, at least for pathologic α-synuclein elements, and therefore enable their usage by the great majority of laboratories. Adoption of uniformly sensitive methods may result in fewer inconsistencies [21, 49] between laboratories investigating α-synuclein pathology.

Supplementary Material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00401-008-0409-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Acknowledgments

The Sun Health Research Institute Brain Donation Program is supported by the National Institute on Aging (P30 AG19610 Arizona Alzheimer’s Disease Core Center), the Arizona Department of Health Services (contract 211002, Arizona Alzheimer’s Research Center), the Arizona Biomedical Research Commission (contracts 4001, 0011 and 05–901 to the Arizona Parkinson’s Disease Consortium) and the Prescott Family Initiative of the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research. Dr. Roncaroli is supported by the United Kingdom Parkinson’s Disease Society Tissue Bank. Dr. Leverenz is supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Contributor Information

Thomas G. Beach, Civin Laboratory for Neuropathology, Sun Health Research Institute, 10515 West Santa Fe Drive, Sun City, AZ 85351, USA, e-mail: thomas.beach@sunhealth.org

Charles L. White, Neuropathology Laboratory and Pathology Immunohistochemistry Laboratory, University of Texas Southwestern Medical School, Dallas, TX, USA

Ronald L. Hamilton, Department of Pathology, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, PA, USA

John E. Duda, Parkinson’s Disease Research, Education and Clinical Center, Philadelphia Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Philadelphia, PA, USA

Takeshi Iwatsubo, Department of Life-Pharmaceutics, University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan.

Dennis W. Dickson, Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathology, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL, USA

James B. Leverenz, Department of Neurology, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA; Veterans Affairs Puget Sound Health Care System, Seattle, WA, USA.

Federico Roncaroli, Department of Clinical Neuroscience, Imperial College, London, UK.

Manuel Buttini, Elan Pharmaceuticals, San Francisco, CA, USA.

Christa L. Hladik, Neuropathology Laboratory and Pathology, Immunohistochemistry Laboratory, University of Texas Southwestern Medical School, Dallas, TX, USA

Lucia I. Sue, Civin Laboratory for Neuropathology, Sun Health Research Institute, 10515 West Santa Fe Drive, Sun City, AZ 85351, USA

Joseph V. Noorigian, Parkinson's Disease Research, Education and Clinical Center, Philadelphia Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Philadelphia, PA, USA

Charles H. Adler, Department of Neurology, Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, AZ, USA

References

- 1.Alafuzoff I, Parkkinen L, Al-Sarraj S, Arzberger T, Bell J, Bodi I, Bogdanovic N, Budka H, Ferrer I, Gelpi E, Gentleman S, Giaccone G, Kamphorst W, King A, Korkolopoulou P, Kovacs GG, Larionov S, Meyronet D, Monoranu C, Morris J, Parchi P, Patsouris E, Roggendorf W, Seilhean D, Streichenberger N, Thal DR, Kretzschmar H. Assessment of alpha-synuclein pathology: a study of the BrainNet Europe Consortium. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2008;67:125–143. doi: 10.1097/nen.0b013e3181633526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arai T, Ueda K, Ikeda K, Akiyama H, Haga C, Kondo H, Kuroki N, Niizato K, Iritani S, Tsuchiya K. Argyrophilic glial inclusions in the midbrain of patients with Parkinson’s disease and diffuse Lewy body disease are immunopositive for NACP/alpha-synuclein. Neurosci Lett. 1999;259:83–86. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(98)00890-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Armstrong RA, Cairns NJ, Lantos PL. Multiple system atrophy (MSA): topographic distribution of the alpha-synuclein-associated pathological changes. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2006;12:356–362. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2006.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arnold MM, Srivastava S, Fredenburgh J, Stockard CR, Myers RB, Grizzle WE. Effects of fixation and tissue processing on immunohistochemical demonstration of specific antigens. Biotech Histochem. 1996;71:224–230. doi: 10.3109/10520299609117164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baba M, Nakajo S, Tu PH, Tomita T, Nakaya K, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ, Iwatsubo T. Aggregation of alpha-synuclein in Lewy bodies of sporadic Parkinson’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. Am J Pathol. 1998;152:879–884. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beach TG, Adler CH, Sue LI, Peirce JB, Bachalakuri J, Sing-Hernandez JE, Lue LF, Caviness JN, Connor DJ, Sabbagh MN, Walker DG. Reduced striatal tyrosine hydroxylase in incidental Lewy body disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2008;115:445–451. doi: 10.1007/s00401-007-0313-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beach TG, Sue LI, Walker DG, Roher AE, Lue L, Vedders L, Connor DJ, Sabbagh MN, Rogers J. The Sun Health Research Institute Brain Donation Program: description and experience, 1987–2007. Cell Tissue Bank. 2007 doi: 10.1007/s10561-008-9067-2. 8 November 2007 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beach TG, Tago H, Nagai T, Kimura H, McGeer PL, McGeer EG. Perfusion-fixation of the human brain for immunohistochemistry: comparison with immersion-fixation. J Neurosci Methods. 1987;19:183–192. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(87)80001-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bloch A, Probst A, Bissig H, Adams H, Tolnay M. Alpha-synuclein pathology of the spinal and peripheral autonomic nervous system in neurologically unimpaired elderly subjects. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2006;32:284–295. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2006.00727.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Braak H, Alafuzoff I, Arzberger T, Kretzschmar H, Del Tredici K. Staging of Alzheimer disease-associated neurofibrillary pathology using paraffin sections and immunocytochemistry. Acta Neuropathol. 2006;112:389–404. doi: 10.1007/s00401-006-0127-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Braak H, Del Tredici K, Bratzke H, Hamm-Clement J, Sandmann-Keil D, Rub U. Staging of the intracerebral inclusion body pathology associated with idiopathic Parkinson’s disease (preclinical and clinical stages) J Neurol. 2002;249 Suppl 3:III/1–III/5. doi: 10.1007/s00415-002-1301-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Croisier E, MRes DE, Deprez M, Goldring K, Dexter DT, Pearce RK, Graeber MB, Roncaroli F. Comparative study of commercially available anti-alpha-synuclein antibodies. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2006;32:351–356. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2006.00722.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duda JE, Giasson BI, Chen Q, Gur TL, Hurtig HI, Stern MB, Gollomp SM, Ischiropoulos H, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ. Widespread nitration of pathological inclusions in neurodegenerative synucleinopathies. Am J Pathol. 2000;157:1439–1445. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64781-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duda JE, Giasson BI, Gur TL, Montine TJ, Robertson D, Biaggioni I, Hurtig HI, Stern MB, Gollomp SM, Grossman M, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ. Immunohistochemical and biochemical studies demonstrate a distinct profile of alpha-synuclein permutations in multiple system atrophy. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2000;59:830–841. doi: 10.1093/jnen/59.9.830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duda JE, Giasson BI, Mabon ME, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ. Novel antibodies to synuclein show abundant striatal pathology in Lewy body diseases. Ann Neurol. 2002;52:205–210. doi: 10.1002/ana.10279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duda JE, Giasson BI, Mabon ME, Miller DC, Golbe LI, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ. Concurrence of alpha-synuclein and tau brain pathology in the Contursi kindred. Acta Neuropathol. 2002;104:7–11. doi: 10.1007/s00401-002-0563-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fujiwara H, Hasegawa M, Dohmae N, Kawashima A, Masliah E, Goldberg MS, Shen J, Takio K, Iwatsubo T. alpha-Synuclein is phosphorylated in synucleinopathy lesions. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:160–164. doi: 10.1038/ncb748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giasson BI, Duda JE, Forman MS, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ. Prominent perikaryal expression of alpha- and beta-synuclein in neurons of dorsal root ganglion and in medullary neurons. Exp Neurol. 2001;172:354–362. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2001.7805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giasson BI, Duda JE, Murray IV, Chen Q, Souza JM, Hurtig HI, Ischiropoulos H, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM. Oxidative damage linked to neurodegeneration by selective alpha-synuclein nitration in synucleinopathy lesions. Science. 2000;290:985–989. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5493.985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giasson BI, Jakes R, Goedert M, Duda JE, Leight S, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM. A panel of epitope-specific antibodies detects protein domains distributed throughout human alpha-synuclein in Lewy bodies of Parkinson’s disease. J Neurosci Res. 2000;59:528–533. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(20000215)59:4<528::AID-JNR8>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Halliday GM, McCann H. Human-based studies on alpha-synuclein deposition and relationship to Parkinson’s disease symptoms. Exp Neurol. 2008;209:12–21. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hamilton RL. Lewy bodies in Alzheimer’s disease: a neuro-pathological review of 145 cases using alpha-synuclein immunohistochemistry. Brain Pathol. 2000;10:378–384. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2000.tb00269.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hashimoto M, Hsu LJ, Sisk A, Xia Y, Takeda A, Sundsmo M, Masliah E. Human recombinant NACP/alpha-synuclein is aggregated and fibrillated in vitro: relevance for Lewy body disease. Brain Res. 1998;799:301–306. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00514-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hashimoto M, Masliah E. Alpha-synuclein in Lewy body disease and Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Pathol. 1999;9:707–720. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1999.tb00552.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hladik CL, White CL. Comparison of digestive enzyme and formic acid pretreatment for optimal immunohistochemical demonstration of alpha-synuclein-immunoreactive cerebral cortical Lewy neurites. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2003;62:554–554. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ihara Y. Massive somatodendritic sprouting of cortical neurons in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Res. 1988;459:138–144. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)90293-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iseki E, Marui W, Akiyama H, Ueda K, Kosaka K. Degeneration process of Lewy bodies in the brains of patients with dementia with Lewy bodies using alpha-synuclein-immunohistochemistry. Neurosci Lett. 2000;286:69–73. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(00)01090-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Iseki E, Marui W, Kosaka K, Akiyama H, Ueda K, Iwatsubo T. Degenerative terminals of the perforant pathway are human alpha-synuclein-immunoreactive in the hippocampus of patients with diffuse Lewy body disease. Neurosci Lett. 1998;258:81–84. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(98)00856-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jakes R, Crowther RA, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ, Iwatsubo T, Goedert M. Epitope mapping of LB509, a monoclonal antibody directed against human alpha-synuclein. Neurosci Lett. 1999;269:13–16. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(99)00411-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jellinger KA. Lewy body-related alpha-synucleinopathy in the aged human brain. J Neural Transm. 2004;111:1219–1235. doi: 10.1007/s00702-004-0138-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kuusisto E, Parkkinen L, Alafuzoff I. Morphogenesis of Lewy bodies: dissimilar incorporation of alpha-synuclein, ubiquitin, and p62. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2003;62:1241–1253. doi: 10.1093/jnen/62.12.1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leong AS, Gilham PN. The effects of progressive formaldehyde fixation on the preservation of tissue antigens. Pathology. 1989;21:266–268. doi: 10.3109/00313028909061071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leverenz J, Hamilton R, Tsuang DW, Schantz A, Vavrek D, Kukull W, Lopez O, Galasko D, Masliah E, Kaye J, Nixon R, Clark C, Trojanowsk JQ, Montine TJ. Empiric refinement of the pathologic assessment of Lewy-related pathology in the dementia patient. Brain Pathol. 2008;18:220–224. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2007.00117.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McKeith IG, Dickson DW, Lowe J, Emre M, O’Brien JT, Feldman H, Cummings J, Duda JE, Lippa C, Perry EK, Aarsland D, Arai H, Ballard CG, Boeve B, Burn DJ, Costa D, Del ST, Dubois B, Galasko D, Gauthier S, Goetz CG, Gomez-Tortosa E, Halliday G, Hansen LA, Hardy J, Iwatsubo T, Kalaria RN, Kaufer D, Kenny RA, Korczyn A, Kosaka K, Lee VM, Lees A, Litvan I, Londos E, Lopez OL, Minoshima S, Mizuno Y, Molina JA, Mukaetova-Ladinska EB, Pasquier F, Perry RH, Schulz JB, Trojanowski JQ, Yamada M. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: third report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology. 2005;65:1863–1872. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000187889.17253.b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McKeith IG, Galasko D, Kosaka K, Perry EK, Dickson DW, Hansen LA, Salmon DP, Lowe J, Mirra SS, Byrne EJ, Lennox G, Quinn NP, Edwardson JA, Ince PG, Bergeron C, Burns A, Miller BL, Lovestone S, Collerton D, Jansen EN, Ballard C, de Vos RA, Wilcock GK, Jellinger KA, Perry RH. Consensus guidelines for the clinical and pathologic diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB): report of the consortium on DLB international workshop. Neurology. 1996;47:1113–1124. doi: 10.1212/wnl.47.5.1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Minguez-Castellanos A, Chamorro CE, Escamilla-Sevilla F, Ortega-Moreno A, Rebollo AC, Gomez-Rio M, Concha A, Munoz DG. Do alpha-synuclein aggregates in autonomic plexuses predate Lewy body disorders?: a cohort study. Neurology. 2007;68:2012–2018. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000264429.59379.d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mori F, Piao YS, Hayashi S, Fujiwara H, Hasegawa M, Yoshimoto M, Iwatsubo T, Takahashi H, Wakabayashi K. Alpha-synuclein accumulates in Purkinje cells in Lewy body disease but not in multiple system atrophy. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2003;62:812–819. doi: 10.1093/jnen/62.8.812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mori F, Tanji K, Yoshimoto M, Takahashi H, Wakabayashi K. Demonstration of alpha-synuclein immunoreactivity in neuronal and glial cytoplasm in normal human brain tissue using proteinase K and formic acid pretreatment. Exp Neurol. 2002;176:98–104. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2002.7929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Muller CM, de Vos RA, Maurage CA, Thal DR, Tolnay M, Braak H. Staging of sporadic Parkinson disease-related alpha-synuclein pathology: inter- and intra-rater reliability. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2005;64:623–628. doi: 10.1097/01.jnen.0000171652.40083.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Parkkinen L, Soininen H, Alafuzoff I. Regional distribution of alpha-synuclein pathology in unimpaired aging and Alzheimer disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2003;62:363–367. doi: 10.1093/jnen/62.4.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pollard K, Lunny D, Holgate CS, Jackson P, Bird CC. Fixation, processing, and immunochemical reagent effects on preservation of T-lymphocyte surface membrane antigens in paraffin-embedded tissue. J Histochem Cytochem. 1987;35:1329–1338. doi: 10.1177/35.11.3309048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Polymeropoulos MH, Lavedan C, Leroy E, Ide SE, Dehejia A, Dutra A, Pike B, Root H, Rubenstein J, Boyer R, Stenroos ES, Chandrasekharappa S, Athanassiadou A, Papapetropoulos T, Johnson WG, Lazzarini AM, Duvoisin RC, Di Iorio G, Golbe LI, Nussbaum RL. Mutation in the alpha-synuclein gene identified in families with Parkinson’s disease. Science. 1997;276:2045–2047. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5321.2045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saito Y, Kawashima A, Ruberu NN, Fujiwara H, Koyama S, Sawabe M, Arai T, Nagura H, Yamanouchi H, Hasegawa M, Iwatsubo T, Murayama S. Accumulation of phosphorylated alpha-synuclein in aging human brain. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2003;62:644–654. doi: 10.1093/jnen/62.6.644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Saito Y, Ruberu NN, Sawabe M, Arai T, Kazama H, Hosoi T, Yamanouchi H, Murayama S. Lewy body-related alpha-synucleinopathy in aging. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2004;63:742–749. doi: 10.1093/jnen/63.7.742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Spillantini MG, Crowther RA, Jakes R, Cairns NJ, Lantos PL, Goedert M. Filamentous alpha-synuclein inclusions link multiple system atrophy with Parkinson’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurosci Lett. 1998;251:205–208. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(98)00504-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Spillantini MG, Schmidt ML, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ, Jakes R, Goedert M. Alpha-synuclein in Lewy bodies. Nature. 1997;388:839–840. doi: 10.1038/42166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Takeda A, Mallory M, Sundsmo M, Honer W, Hansen L, Masliah E. Abnormal accumulation of NACP/alpha-synuclein in neurodegenerative disorders. Am J Pathol. 1998;152:367–372. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM. Parkinson’s disease and related neurodegenerative synucleinopathies linked to progressive accumulations of synuclein aggregates in brain. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2001;7:247–251. doi: 10.1016/s1353-8020(00)00065-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tsuang DW, Riekse RG, Purganan KM, David AC, Montine TJ, Schellenberg GD, Steinbart EJ, Petrie EC, Bird TD. Lewy body pathology in late-onset familial Alzheimer’s disease: a clinicopathological case series. J Alzheimers Dis. 2006;9:235–242. doi: 10.3233/jad-2006-9302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tu PH, Galvin JE, Baba M, Giasson B, Tomita T, Leight S, Nakajo S, Iwatsubo T, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM. Glial cytoplasmic inclusions in white matter oligodendrocytes of multiple system atrophy brains contain insoluble alpha-synuclein. Ann Neurol. 1998;44:415–422. doi: 10.1002/ana.410440324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00401-008-0409-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.