Abstract

In the diabetic eye, the increased accumulation of sorbitol in the retina has been implicated in the pathogenesis of diabetic retinopathy. Neurodegeneration is an important component of diabetic retinopathy as demonstrated by increased neural apoptosis in the retina during experimental and human diabetes. Insulin receptor (IR) activation has been shown to rescue retinal neurons from apoptosis through a phosphoinositide 3-kinase and protein kinase B (Akt) survival cascade. In this study we examined the IR signaling in sorbitol-induced hyperosmotic stressed retinas.

INTRODUCTION

Sorbitol is a sugar substitute often used in diet foods (including diet drinks and ice cream) and sugar-free chewing gums. It also occurs naturally in many stone fruits and berries from trees of the genus Sorbus. Ingesting large amounts of sorbtiol can lead to some abdominal pain, gas and mild to severe diarrhea. Sorbitol can also aggravate irritable bowl syndrome and fructose malabsorption. Sorbitol can be used as a non-stimulant laxative as either an oral suspension or suppository. The drug works by drawing water into the large intestine, thereby stimulating bowl movements (Lederle, 1995). Even in the absence of dietary sorbitol, cells can produce sorbitol naturally. When too much sorbitol is produced inside the cells, it can cause damage (Lorenzi, 2007). Diabetic retinopathy and neuropathy may be related to excess sorbitol in the cells of the eyes and nerves (Asnaghi et al., 2003;Lorenzi, 2007;Gabbay, 1973a). The source of this sorbitol in diabetes is excess glucose, which goes through the polyol pathway.

The polyol pathway of glucose metabolism is active when the intercellular glucose levels are elevated in the cell (Gabbay, 1973b). Aldose reductase (AR), the first and the rate limiting enzyme in the pathway reduces glucose to sorbitol using NADPH as a cofactor (Lorenzi, 2007). Sorbitol is then metabolized to fructose by sorbitol dehydrogenase (SDH) that used NAD+ as cofactor (Lorenzi, 2007). Sorbitol is an alcohol that is polyhydroxylated, and strongly hydrophilic and does not diffuse readily through cell membranes and accumulates intracellularly with possible osmotic consequences (Gabbay, 1973b). The fructose produced by the polyol pathway can get phosphorylated to fructose 3-phosphate (Szwergold et al., 1990), which can be further broken down to 3-deoxyglucosone, and both these compounds can be very powerful glycosylating agents that can result in the formation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) (Szwergold et al., 1990). The usage of NADPH by AR may result in less cofactor becoming available to glutathione reductase, which is critical for the maintenance of the intracellular pools of reduced glutathione (GSH) (Lorenzi, 2007). This reduces the capability of cells to respond to oxidative stress (Barnett et al., 1986). Compensatory increased activity of the glucose monophosphate shunt, the principle supplier of cellular NADPH may occur (Barnett et al., 1986). The usage of NAD by SDH leads to an increased ratio of NADH/NAD+ which has been termed “pseudohypoxia” and linked to a multitude of metabolic and signaling changes known to alter cell function (Williamson et al., 1993). Excess NADH serves as a substrate for NADH oxidase and this could be a mechanism for the generation of intracellular oxidant species (Lorenzi, 2007). Thus activation of polyol pathway, by altering the intracellular homeostasis, generating AGEs, and exposing cells to oxidant stress due to decreased antioxidant defense mechanism and generation of oxidant species can initiate several mechanisms of cellular damage.

Accumulation of sorbitol and fructose and the generation or enhancement of oxidative stress has been reported in the whole retina of diabetic animals (Gabbay, 1975;Dagher et al., 2004;Lorenzi, 2007). The retinas of experimentally derived diabetic rats show increased lipid peroxidation (Obrosova et al., 2003), increased nitrotyrosine formation (Obrosova et al., 2005) and depletion of antioxidant enzymes (Obrosova et al., 2003). These abnormalities are prevented by drugs that inhibit AR (Dahlin et al., 1987;Tomlinson et al., 1992;Narayanan, 1993;Tomlinson et al., 1994;Obrosova et al., 2003;Lorenzi, 2007). Retinas from diabetic patients with retinopathy show more abundant AR immunoreactivity in ganglion cells, nerve fibers, and Muller cells than retinas from nondiabetic individuals (Vinores et al., 1988). It has also been shown that human retinas from nondiabetic eye donors exposed to high glucose levels in organ cultures accumulate sorbitol to the same extent as similarly incubated retinas of nondiabetic rats (Dagher et al., 2004). Retinal ganglion cells, Muller glia, vascular pericytes and endothelial cells are endowed with AR in all species (Dagher et al., 2004) and these cells are known to be damaged in diabetes (Lorenzi and Gerhardinger, 2001). The retinal vessels of diabetic rats treated with sorbinill, an AR inhibitor for the 9 months duration of diabetes, showed prevention of early complement activation, decreased levels of complement inhibitors, microvascular cell apoptosis and acellular capillaries (Dagher et al., 2004). Based on the data from the animal models, there is evidence for the concept that polyol pathway activation is a sufficient mechanism for the retinal abnormalities induced by diabetes in rats.

Neurodegeneration is an important component of diabetic retinopathy as demonstrated by increased neural apoptosis in the retina during experimental and human diabetes (Barber et al., 1998). IR activation has been shown to rescue retinal neurons from apoptosis through a phosphoinositide 3-kinase and protein kinase B (Akt) survival cascade. A significant decrease of retinal IR kinase activity has been reported after 4 weeks of hyperglycemia in STZ treated rats (Reiter et al., 2006). Hyperosmotic-stress responses interact with the insulin signaling pathways at several levels (Ouwens et al., 2001). Sorbitol has been previously shown to induce the tyrosine phosphorylation of IR (Ouwens et al., 2001).

In the present study we examined the retinal insulin receptor signaling in sorbitol-treated retinas ex vivo and show that sorbitol activates both the IR and IGF-1R tyrosine kinases, which results in activation of the receptor’s direct downstream targets. This receptor activation leads to the activation of PI3K and Akt survival pathway in the retina. With the advent of phospho-site-specific antibody microarry, we observed either increased or decreased phosphorylation of several tyrosine, serine/threonine kinases and cytoskeletal proteins which are downstream effector molecules of IR and IGF-1R signaling pathways.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Human insulin R (rDNA origin) was obtained from Eli Lilly & Co. (Indianapolis, IN). The actin antibody was obtained from Affinity BioReagents (Golden, CO). Polyclonal anti-IRß, polyclonal anti-Cbl and monoclonal anti-PY-99 antibodies were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Polyclonal anti-Gab1 antibody was obtained from Upstate Biotechnology (Lake Placid, NY). Sorbitol, BAPTA and SB 203580 were obtained from Sigma (St Louis, MO). LY294002, anti-pAkt (S473), anti-Akt, anti-p38 and anti-phospho-p38 antibodies were obtained from Cell Signaling (Beverly, MA). Genestin, HNMP3, PP1, PP2 and PP3 were obtained from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA). Actin antibody was obtained from Affinity BioReagents (Golden, CO). All other reagents were of analytical grade and from Sigma (St. Louis, MO).

Animals

All animal work was done in strict accordance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology on the Use of Animals in Vision Research. All protocols were approved by the IACUC at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center and the Dean McGee Eye Institute. In all experiments, rats were killed by asphyxiation with carbon dioxide before the retinas were removed.

Retinal organ cultures

Retinal organ cultures were carried out as previously described (Rajala et al., 2004;Rajala et al., 2007). Retinas were removed from Sprague-Dawley albino rats that were born and raised in dim cyclic light (5 lux; 12 h ON: 12 h OFF), and incubated for either 5 min (insulin) or 30 min (sorbitol) at 37 °C in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s (DMEM) medium (Gibco BRL) in the presence of either insulin or sorbitol. Control cultures were carried out in the absence of additives. At the indicated times, retinas were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80 °C until analyzed. The retinas were lysed in lysis buffer [1% NP 40, 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), and 2 mM EDTA] containing phosphatase inhibitors (100 mM NaF, 10 mM Na4P2O7, 1 mM NaVO3 and 1 mM molybdate) and protease inhibitors (10 μM leupeptin, 10 μg/ml aprotinin, and 1 mM PMSF), and kept on ice for 10 min followed by centrifugation at 4 °C for 20 min.

Preparation of rat rod outer segments

Retinas in culture were stimulated with either 1 μM insulin or 1 M sorbitol for 30 min at 37 °C. After treatment, the rod outer segments (ROS) were prepared using a discontinuous sucrose gradient as previously described (Rajala et al., 2002). Retinas were homogenized in 4.0 ml of ice-cold 47% sucrose solution containing buffer A [100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM NaVO3, 1 mM PMSF and 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4)]. Retinal homogenates were transferred to 15-ml centrifuge tubes and sequentially overlaid with 3.0 ml of 42%, 3.0 ml of 37% and 4.0 ml of 32% sucrose dissolved in buffer A. The gradients were spun in a swinging bucket rotor at 82,000 x g for 1 h at 4 °C. The 32/37% interfacial sucrose band, containing the ROS membranes, was harvested and diluted with 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) containing 100 mM NaCl and 1 mM EDTA. The band solution was then centrifuged at 27,000 x g for 30 min at 4 °C. The ROS pellets were resuspended in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) containing 100 mM NaCl and 1 mM EDTA, and stored at -20 °C. The non-ROS band designated Band II (37/42%) was also saved for comparison with the ROS fraction. All protein concentrations were determined by BCA reagent (Pierce, Rockford, IL) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Cloning, expression and purification of protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B

Retinal PTP1B was obtained by PCR after reverse transcribing mouse retinal RNA and using PTP1B primers (sense: GAA TTC ATG GAG ATG GAG AAG GAG TTC GAG; antisense: GTC GAC TCA GTG AAA ACA CAC CCG GTA GC). The PCR product was verified by DNA sequencing, digested with EcoR1 and Sal1, and cloned into GST fusion vector, pGEX-4T1. Site-directed mutagenesis was carried out according to methods described earlier (Rajala et al., 2004). Mutant PTP1B-D181A was amplified using primers, (sense: ACC ACA TGG CCT GCC TTT GGA GTC CCC; antisense: GGG GAC TCC AAA GGC AGG CCA TGT GGT). The PCR products were cloned into TOPO vector (Invitrogen) and both the WT and mutant sequences were verified by DNA sequencing. The WT and mutant cDNAs were later excised from the sequencing vector as EcoRI/SalI fragments and cloned into GST fusion vector, pGEX-4T1. An overnight culture of E.coli BL21 (DE3) (pGEX-PTP1Bor pGEX-PTP1B-D181A) was diluted 1:10 with 100μg/ml ampicillin per ml, grown for 1 hr at 37 °C, and induced for another hour by addition of IPTG to 1 mM. Bacteria were sonicated three times for 20 s each time in lysis buffer containing 10 mM imidazole-HCl (pH7.2), 1 mM EDTA, 100 mM NaCl, 1mM dithiothreitol, and 1% Triton X-100. Lysates were clarified by centrifugation, and the supernatants were incubated with 500 μl of 50% glutathione-coupled beads (Amersham Pharmacia) for 30 min at 4 °C. The GST-PTP1B fusion proteins were washed in lysis buffer and eluted twice with 1 ml of 5 mM reduced glutathione (Sigma) in phosphatase buffer [20 mM Tris (pH 7.4), 5% glycerol, 0.05% Trion X-100, 2.5 mM MgCl2, aprotinin (2 μg/ml) and leupeptin (5 μg/ml)]. Glycerol was added to a final concentration of 33% (vol/vol), and aliquots of enzyme were stored at -20 °C.

PI3-kinase assay

Enzyme assays were carried out as previously described (Rajala et al., 2007). Briefly, assays were performed directly on either IRβ or Cbl immunoprecipitates of retinal lysates prepared from sorbitol treated or untreated lysates in 50 μl of reaction mixture containing 0.2 mg/ml PI-4,5-P2, 50 μM ATP, 10 μCi [γ32P]ATP, 5 mM MgCl2, and 10 mM HEPES buffer (pH 7.5). The reactions were carried out for 30 min at room temperature and stopped by the addition of 100 μl of 1 N HCl followed by 200 μl of chloroform/methanol (1/1, v/v). Lipids were extracted and resolved on oxalate-coated TLC plates (silica gel 60) with a solvent system of 2-propanol/2 M acetic acid (65/35, v/v). The plates were coated in 1% (w/v) potassium oxalate in 50% (v/v) methanol and then baked in an oven at 100 °C for 1 hr prior to use. TLC plates were exposed to X-ray film overnight at -70 °C and radioactive lipids were scraped and quantified by liquid scintillation counting.

Phosphatase activity assay

The sorbitol-treated or untreated retinas were lysed in buffer containing 10 mM imidazole-HCl (pH7.2), 1 mM EDTA, 100 mM NaCl, 1mM dithiothreitol, and 1% Triton X-100. The assays were performed (Takai and Mieskes, 1991) directly on retinal lysates in 80 μl of reaction mixture containing assay buffer [25 mM HEPES (pH 7.2), 50 mM NaCl, 5 mM dithiothritol, 2.5 mM EDTA], 5 μl of 5% BSA and either test or positive control sample. The reactions were pre-incubated at 37 °C for 15 min, followed by the addition of 120 μl of pNPP (1.5 mg/ml) and incubated for 5-15 min at 37 °C. The reactions were stopped by the addition of 20 μl of 13% K2HPO4 and the absorbance read at 405 nm. One unit of enzyme activity was equivalent to 1 nmol PNPP hydrolyzed per minute and the extinction coefficient for pNPP at A405 = 1.78 × 104 M-1 cm-1.

Dephosphorylation of tyrosine phosphorylated proteins by PTP1B in vitro

Sorbitol treated or untreated retinal proteins were incubated in the presence of catalytically active or inactive PTP1B for 30 min at 30 °C. At the end of the incubation period, the reaction products were subjected to Western blot analysis with anti-PY99 antibody.

Antibody Microarry

Control and sorbitol-treated retinas in culture were lysed in lysis buffer [1% NP 40, 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 2 mM EDTA and 1 mM dithiothreitol] containing phosphatase inhibitors (100 mM NaF, 10 mM Na4P2O7, 1 mM NaVO3 and 1 mM molybdate) and protease inhibitors (10 μM leupeptin, 10 μg/ml aprotinin, and 1 mM PMSF), and kept on ice for 10 min followed by centrifugation at 4 °C for 20 min. The protein samples were then subjected to screening using antibody microarry containing 377 pan-specific and 273 phospho-site-specific antibodies (Kinexus Services, Vancouver, Canada).

Immunoprecipitation

Retinal lysates were prepared as previously described (Li et al., 2007). Insoluble material was removed by centrifugation at 17,000 x g for 20 min at 4 °C, and the solubilized proteins were pre-cleared by incubation with 40 μl of protein A-Sepharose for 1 h at 4 °C with mixing. The supernatant was incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C and subsequently with 40 μl of protein A-Sepharose for 2 h at 4 °C. Following centrifugation at 17,000 x g for 1 min at 4 °C, immune complexes were washed three times with ice-cold wash buffer [50 mM HEPES (pH 7.4) 118 mM NaCl, 100 mM NaF, 2 mM NaVO3, 0.1% (w/v) SDS and 1% (v/v) Triton X-100]. The immunoprecipitates were either subjected to Western blotting analysis or used to measure the PI3K activity.

SDS-PAGE and Western blotting

Proteins were resolved by 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes. The blots were washed twice for 10 min with TTBS [20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 100 mM NaCl, and 0.1% Tween-20] and blocked with either 5% bovine serum albumin or non-fat dry milk powder (Bio-Rad) in TTBS for 1 h at room temperature. Blots were then incubated with anti-PY99 (1:1000), anti-Cbl (1:1000), anti-pAkt (1:1000), anti-Akt (1:1000), or anti-Akt1 (1:1000) or anti-Akt2 (1:1000) or anti-Akt3 (1:1000) or anti-IRß or anti-IGF 1R (1:1000) or anti-actin (1:1000) antibodies overnight at 4 °C. Following primary antibody incubations, immunoblots were incubated with HRP-linked secondary antibodies (either anti-rabbit or anti-mouse) and developed by ECL according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

RESULTS

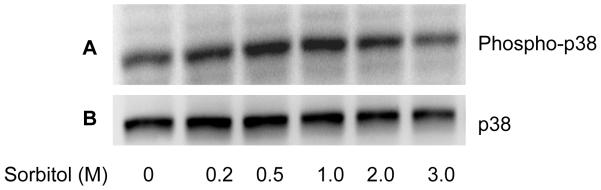

Sorbitol-induced activation of p38MAP kinase

The p38MAP kinase is known to be activated in stress (Cheng et al., 2002). To determine if sorbitol induces the activation of p38MAP kinase, we subjected the sorbitol-treated retinal proteins to western blot analysis with anti-phospho-p38 and total p38 antibodies. The results indicate a gradual increase in p38 phosphorylation between 0.2 and 1.0 M sorbitol compared to control (Fig. 1A). The total p38 levels were unchanged in the presence of varying concentrations of sorbitol (Fig. 1B). These results suggested that sorbitiol induces the activation of p38MAP kinase and the organotypic cultures were mimicking the in vivo stress condition.

Figure 1.

Concentration dependent Sorbitol-induced activation of p38 MAP kinase. Various concentrations of sorbitol treated retinal samples were subjected to Western blot analysis with anti-phospho-p38MAP kinase (A) and anti-p38 MAP kinase (B) antibodies.

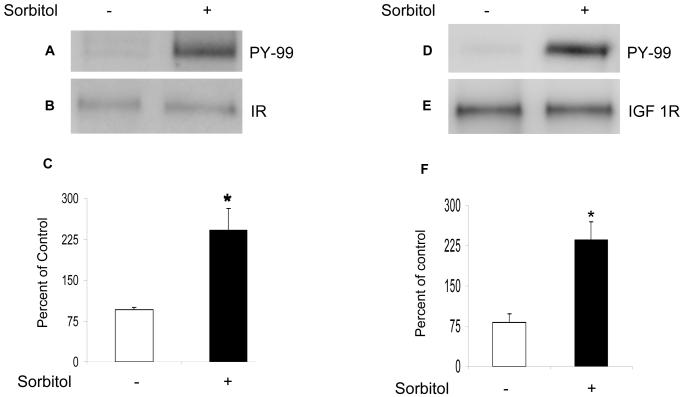

Sorbitol-induced activation of insulin- and insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor

To determine the sorbitol-induced activation of IR and IGF-1 receptors, we immunoprecipitated retinal lysates from control and sorbitol-treated organotypic cultures with anti-IRß (Fig. 2B) and anti-IGF 1R (Fig. 2E) antibodies followed by Western blot analysis with anti-PY99 antibody. The results indicated the activation of IR (Fig. 2A and 2C) and IGF 1R (Fig. 2D and 2F) in response to sorbitol-induced stress.

Figure 2.

Sorbitol-induced activation of IR and IGF-1R. Retinal proteins from control and 1.0 M sorbitol-treated organotypic cultures were immunoprecipitated with anti-IRß antibody followed by Western blot analysis with anti-PY99 antibody (A). The blots were stripped and reprobed with anti-IRß antibody to ensure equal amounts of IR in each immunoprecipitate (B). Densities were calculated from the immunoblots and the results are expressed as percentage of PY99/IR. Absence of sorbitol was taken as 100 percent (C). Data mean ± SD, n=3, *p<0.001. Sorbitol-induced activation of IGF 1R. Retinal proteins from the control and 1.0 M sorbitol-treated organotypic cultures were immunoprecipitated with anti-IGF 1R antibody followed by Western blot analysis with anti-PY99 antibody (D). The blots were stripped and reprobed with anti-IGF 1R antibody to ensure equal amount of IGF 1R in each immunoprecipitate (E). Densities were calculated from the immunoblots and the results are expressed as percentage of PY99/IR. Absence of sorbitol was taken as 100 percent (F). Data mean ± SD, n=3, *p<0.001.

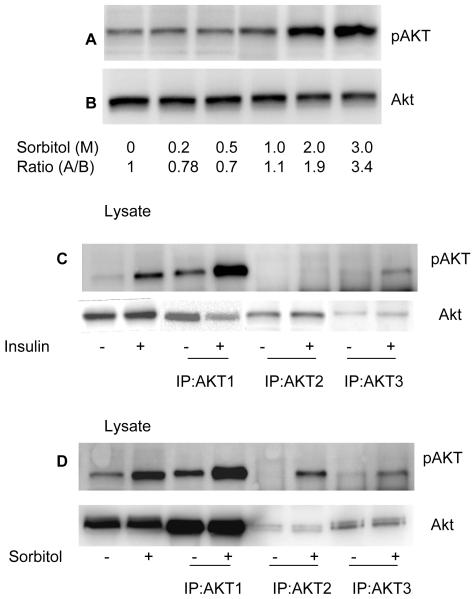

Sorbitol-induced activation of Akt

To determine if sorbitol-induced the activation of Akt, we incubated rat retinas in organotypic cultures for 30 min in the presence of varying concentrations of sorbitol (0, 0.2, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0 and 3.0 M). At the end of the incubation, the retinas were lysed and subjected to Western blot analysis with anti-pAkt (S473) and anti-total Akt antibodies. The results indicated a gradual increase in Akt phosphorylation from 1.0 to 3.0 M sorbitol (Fig. 3A). The total Akt levels did not change in response to sorbitol treatment (Fig. 3B). These results suggested that sorbitol induced the activation of Akt.

Figure 3.

Sorbitol-induced activation of Akt isoforms. Various concentrations of sorbitol treated retinal samples were subjected to Western blot analysis with anti-pAkt (S473) (A) and anti-Akt (B) antibodies. Retinas were incubated in culture and treated with either insulin (1 μM) or sorbitol (3M). Retinas were lysed and the proteins were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-Akt1, anti-Akt2 and Anti-Akt3 antibodies followed by Western blot analysis with anti-pAkt (S473) (C and D) antibody. Input, 30 μg of retina lysates stimulated with either presence or absence of insulin or sorbitol.

Sorbitol-induced activation of Akt2

Akt exist in three isoforms, all of which are expressed in the retina (Reiter et al., 2003). To determine if sorbitol stress activated a specific Akt isoform, we immunoprecipitated retinal lysates from non stimulated control, insulin-stimulated and the sorbitol-treated organotypic cultures with anti-Akt1, anti-Akt2 and anti-Akt3 antibodies. The immune complexes were subjected to Western blot analysis with anti-pAkt antibody. The results indicated that insulin activated the Akt1 and the Akt3 isoforms, but not Akt2 (Fig. 3C). Sorbitol treatment, however, resulted in the activation of all three isoforms of Akt (Fig. 3D). These results suggested that the activation of Akt2 isoform may be stress-dependent.

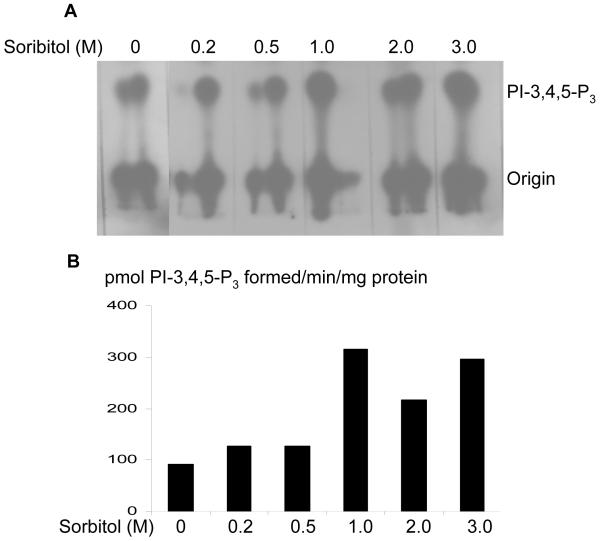

Sorbitol induced activation of insulin receptor associated PI3K activity—Stress-induced activation of PI3K

We have previously reported the activation of PI3K through tyrosine phosphorylated IR in the retina (Rajala et al., 2007). To determine whether the activation of PI3K is regulated through IR, we have immunoprecipitated IR from retinal lysates that were prepared from non stimulated control and sorbitol-treated (0-3.0 M) organotypic cultures, and measured the PI3K activity. The results indicated an increased PI3K activity with IR from sorbitol-treated retinas (Fig. 4). These results suggested that sorbitol-induced activation of PI3K occurs via activation of the IR.

Figure 4.

Sorbitol-induced activation insulin receptor associated PI3K activity. Retinas were cultured in DMEM and treated with various concentrations of sorbitol (0-3 M) for 30 min at 37 °C. TLC autoradiogram of PI3K activity measured in anti-IRβ immunoprecipitates of retinas using PI-4,5-P2 and [γ32P]ATP as substrates (A). The radioactive spots of PI-3,4,5-P3 were scraped from the TLC plate and counted (B).

PI3K-independent activation of Akt

To determine whether sorbitol also induced the activation of Akt independent of PI3K, we incubated the retinas in the presence of the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 for 30 min before sorbitol or insulin treatment. Retinal proteins were subjected to Western blot analysis with anti-pAkt and total Akt antibodies. The results indicated that LY294002 failed to inhibit the sorbitol-induced activation of Akt, but LY294002 inhibited the insulin-induced activation of Akt (Fig. 5A-C), suggesting that Akt activation in hyperosomotic stress can also occur without PI3K activation.

Figure 5.

PI3K-independent activation of Akt. Rat retinas were pre-incubated in DMEM medium with or without the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 (50 μM) for 30 min prior to either 1μM insulin or 3 M sorbitol. Thirty micrograms of retina lysate were subjected to Western blot analysis with anti-phospho-Akt (Ser 473) (A). The blot was stripped and reprobed with anti-Akt (B) and anti-actin (C) antibodies. PI3K activation is independent of p38 MAP kinase activation. Rat retinas were pre-incubated in DMEM medium with or without the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 (50 μM) or MAP kinase inhibitor SB203580 (50 μM) for 30 min prior to the treatment of either 1μM insulin or 3 M sorbitol. Thirty micrograms of retina lysates were subjected to Western blot analysis with anti-phospho-p38 MAP kinase(D). The blot was stripped and reprobed with anti-p38 MAP kinase (E) and anti-actin (F) antibodies.

p38MAP kinase activation is independent of PI3K activation

To determine if PI3K activation regulates the p38MAP kinase pathway, we pre-incubated the retinas in the presence of either the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 or the MAP kinase inhibitor SB203580 followed by sorbitol treatment. The retinal proteins were subjected to Western blot analysis with anti-phospho-p38 and anti-p38 antibodies. The results indicated that phosphorylation of p38 may be inhibited by the MAP kinase inhibitor SB203580 (Fig. 5), whereas the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 failed to inhibit the sorbitol-induced activation of p38 MAP kinase (Fig. 5). These results suggested that MAP kinase activation is independent of PI3K activation during hyperosomotic stress.

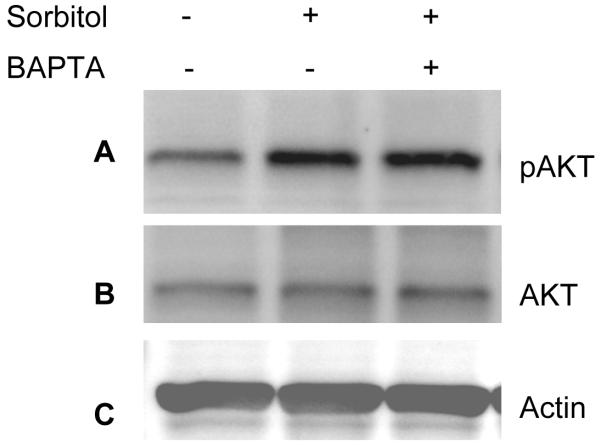

Role of calcium in sorbitol-induced Akt activation

It has been shown that hyperosomotic stress evokes an increase in the cytosolic calcium concentration and triggers calcium signaling (Marchenko and Sage, 2000;Pritchard et al., 2002). To determine whether the sorbitol-induced activation of Akt is calcium dependent, we pre-incubated the retinas in organotypic cultures in the presence of the calcium specific chelator BAPTA followed by 1.0 M sorbitol treatment. The retinas were lysed and the proteins were subjected to Western blot analysis with anti-pAkt, anti-Akt, anti-actin, and anti-PY99 antibodies. The results indicated that BAPTA failed to reduce the activation of Akt and that the levels of Akt activation were similar to the levels seen in the sorbitol treatment (Fig. 6A). The blot was stripped and reprobed with total Akt (Fig. 6B) and actin (Fig. 6C) to ensure that equal amounts of protein were loaded. These results suggested that under our experimental conditions, calcium has no role in the activation of Akt.

Figure 6.

Sorbitol-induced activation of Akt is calcium-independent. Rat retinas were pre-incubated in DMEM medium with or without 15 μM BAPTA for 30 min prior to the treatment of 1 M sorbitol for additional 30 min. Thirty micrograms of retina lysates were subjected to Western blot analysis with anti-pAkt (S473) (A) anti-Akt (B), anti-actin (C) and anti-PY99 (D) antibodies.

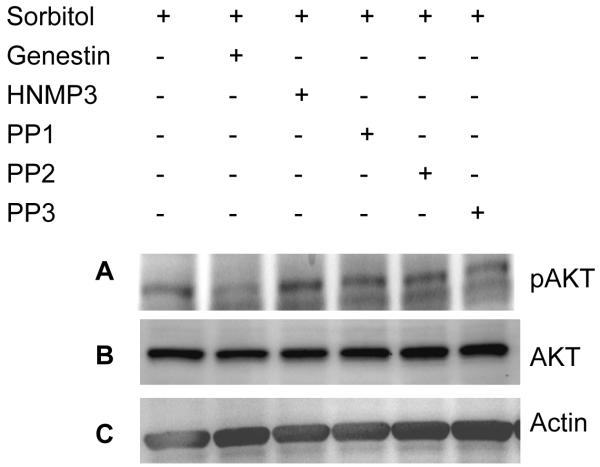

Tyrosine kinase induced-activation of Akt

To determine the pathway by which Akt undergoes activation in sorbitol stress, we have incubated the retinas in organotypic cultures in the presence of tyrosine kinase inhibitors such as genestin (inhibitor of tyrosine kinases), HNMP3 (inhibitor of IR kinase activity), PP1 (src kinase inhibitor), PP2 (src kinase inhibitor) and PP3 (a negative control for the src family protein tyrosine kinase inhibitor PP2) followed by sorbitol treatment. Retinas were lysed, and the proteins were subjected to Western blot analysis with anti-pAkt, anti-Akt and anti-PY99 antibodies. The results indicated that genestin blocked the activation of Akt, but all other tyrosine kinase and non-receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors failed to block the activation of Akt (Fig. 7A). These results suggested that stress-induced activation of Akt is not under the regulation of non-receptor src family tyrosine kinase(s). Collectively these experiments suggested that the activation of Akt in osmotic stress could be through tyrosine kinase activation.

Figure 7.

Tyrosine kinase induced-activation of Akt. Rat retinas were pre-incubated in DMEM medium with or without 100 μM genestin or HNMP3 or PP1 or PP2 or PP3 for 30 min prior to the treatment of 1 M sorbitol for 30 min. Thirty micrograms of retina lysates were subjected to Western blot analysis with anti-pAkt (S473) (A) anti-Akt (B) and anti-actin (C) antibodies.

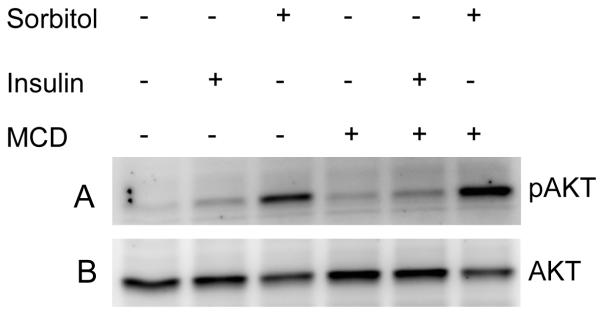

Cholesterol depletion results in the sorbitol-induced activation of Akt

Localization of insulin receptor in caveolae of adipocyte plasma membrane has been reported and cholesterol depletion attenuates insulin receptor signaling (Gustavsson et al., 1999). To examine the role of lipid rafts on Akt activation in sorbitol induced stress, we stimulated retinas in organ cultures with either insulin or sorbitol in the presence or absence of cholesterol-sequestering agent, MCD, a treatment that disrupts cholesterol-rich DRMs. MCD treatment resulted in a dramatic increase in sorbitol-induced activation of Akt compared to retinas treated with sorbitol in the absence of MCD (Fig. 8). Insulin effect on the activation of Akt is significantly lower then either sorbitol or sorbitol in the presence of MCD (Fig. 8). These results clearly suggested that disruption of lipid rafts in sorbitol induced stress, which resulted in the activation of Akt.

Figure 8.

Cholesterol-depletion results in the activation of Akt. Rat retinas were incubated in DMEM medium with or without MCD prior to the treatment of 1 M sorbitol for 30 min. Thirty micrograms of retina lysates were subjected to Western blot analysis with anti-pAkt (S473) (A) and anti-Akt (B) antibodies.

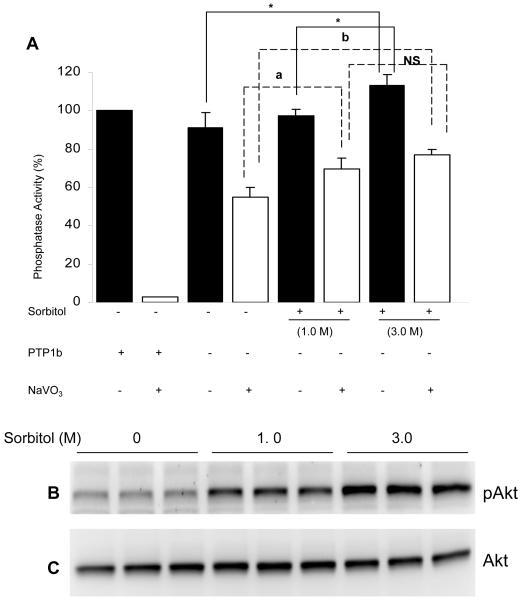

Sorbitol-induced activation of protein phosphatase (PA) activity

To determine whether sorbitol induced the activation of PA, we did phosphatase assays, using p-Nitrophenyl Phosphate (pNPP) as the substrate. The results indicated a significant increase in the PA activity in 3.0 M treated retinas compared to untreated retinas (Fig. 9A). The results suggested that hyperosmotic stress increased the activation of PA activity. The total PA activity we measured did not differentiate serine/threonine phosphatase activity from protein tyrosine phosphatase activity (PTP). To differentiate between the two activities, we measured PA activity in the presence of sodium vanadate to inhibit the PTPase activity. The results indicated a significant increase in serine/threonine PA activity in sorbitol treated retinas compared to untreated retinas (Fig. 9A). Purified PTP1b, a protein tyrosine phosphatase was used as control for the sodium vanadate experiment. The results indicated the complete inhibition of PTP1B activity in the presence of sodium vanadate (Fig. 9A). The protein samples used for the PA activity were used to examine the phosphorylation of Akt and the results indicated an increased phosphorylation of Akt in 3.0 M sorbitol treated retinas (Fig. 9B). The blot were then stripped and reprobed with total Akt to ensure equal amounts of protein were loaded (Fig. 9B). Collectively, these results suggested that the observed activation of Akt in hyperosmotic stress is not due to the inhibition of phosphatase activity by sorbitol.

Figure 9.

Sorbitol-induced activation of phosphatase activity. Retinal proteins from control and sorbitol-treated (1.0 or 3.0 M) or untreated organotypic cultures were subjected to either Western blotting analysis with anti-pAkt (B) and anti-Akt (C) antibodies or measured the phosphatase activity using pNPP as substrate (A). Open bars represent the activity in the presence of 1mM sodium vanadate. Purified GST-PTP1B (5μg) was used as positive control. Data are Data mean ± SD, n= three independent experiments 3, *p<0.001.

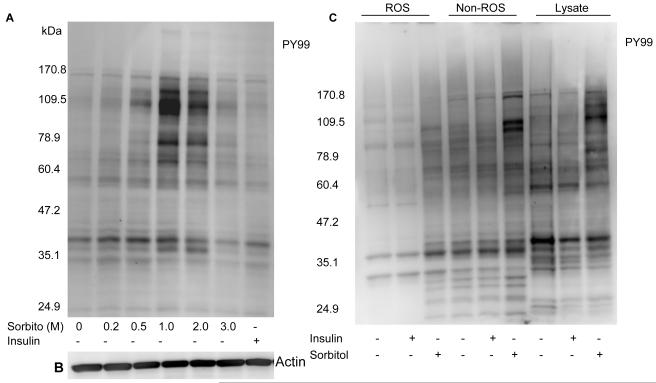

Sorbitol-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of several retinal proteins

The PI3K-independent activation of Akt in the sorbitol-treated retinas prompted us to investigate the pathway by which Akt undergoes activation. Retinal proteins were either stressed with sorbitol or stimulated with insulin and subjected to Western blot analysis with the anti-PY99 antibody. The results indicated a significantly increased level of tyrosine phosphorylation in the retinal proteins in the 1.0 and 2.0 M sorbitol treatment compared to the insulin-stimulated retinas (Fig. 10A). We observed the tyrosine phosphorylation of several retinal proteins, with apparent molecular weights of 170, 130, 115, 79, 70 and 41 kDa.

Figure 10.

Sorbitol-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of several retinal proteins. Retinas were cultured in DMEM in the presence or the absence of either 1 μM insulin or various concentrations of sorbitol for 30 min at 37 °C. Thirty micrograms of retinal proteins were subjected to Western blot analysis with anti-PY 99 antibody (A). The blot was reprobed with the anti-actin antibody to ensure equal amount of protein in each lane (B). ROS and non-ROS proteins were subjected to Western blot analysis with the anti-PY99 antibody (C).

To determine whether the stress-induced tyrosine phosphorylated proteins are localized to the ROS or other retinal membranes, we probed the ROS and the non-ROS fractions with the anti-PY99 antibody. The results indicated a much greater tyrosine phosphorylation in the non-ROS fraction compared to the ROS (Fig. 10B). These results also suggested that stress response induces a significant tyrosine phosphorylation in inner segment and other retinal cell membranes.

To determine the global changes in the phosphorylation (tyrosine and serine/threonine) of retinal proteins, we examined the phosphorylation state of retinal proteins by antibody microarray. Of 273 phospho-site-specific antibodies 33 proteins were found to exhibit either increased or decreased phosphorylation (data not shown). These proteins include serine/threonine and tyrosine kinases and mainly proteins involved in the cytoskeletal organization. These results clearly suggest that hyperosmotic stress-induces the activation of several protein kinases which may in turn regulate the cytoskeletal reorganization.

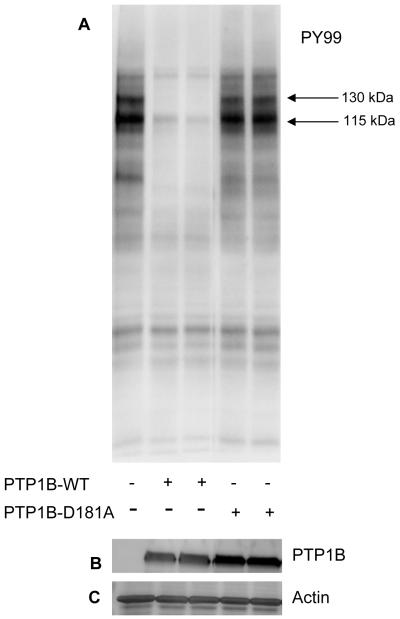

Sorbitol-induced tyrosine phosphorylated proteins are the substrates of protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B (PTP1B) in vitro

Sorbitol treated retinal proteins were subjected to in vitro phosphatase assays in the presence of either catalytically active or inactive PTP1B enzyme. After incubation, the reaction products were subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by Western blot analysis with anti-PY99 antibody. The results indicated that PTP1B dephosphorylates the major 130 and 115 kDa tyrosine phosphorylated proteins in sorbitol-induced stress (Fig. 11).

Figure 11.

PTP1B dephosphorylates the sorbitol-induced tyrosine phosphorylated proteins in vitro. Sorbitol-treated retinal proteins were incubated with either wild type PTP1B or catalytically inactive PTP1B (D181A) for 15 min at 37 °C. At the end of the reaction, proteins were subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by Western blot analysis with anti-PY99 antibody (A). The blot was reprobed with anti-GST (B) and anti-actin (C) antibodies.

Interaction of retinal Cbl with p85 subunit of PI3K under hyperosmotic conditions

To determine the physical interaction between Cbl and p85 subunit of PI3K, we subjected sorbitol-treated or untreated retinal lysates to GST-pull down experiments with GST-p85 full length fusion protein followed by Western blot analysis with anti-Cbl antibody. The results showed the binding of Cbl to p85 subunit of PI3K (Fig. 12A). To further determine whether the binding is phosphorylation dependent, we immunoprecipitated Cbl from sorbitol-treated or untreated retinal lysates followed by either Western blot analysis with anti-PY 99 antibody (Fig. 12B) or directly measured the Cbl associated PI3K activity (Fig. 12C). The results clearly indicated that sorbitol-induced the phopshorylation of Cbl (Fig.12B) and that the phosphorylated Cbl was able to associate with the PI3K activity (Fig. 12C). In addition to being an adaptor protein, Cbl has been characterized as an E3 ubiquitin ligase that interacts with PI3K and mediates its ubiquitination and proteasome degradation (Fang et al., 2001). This interaction is phosphorylation-independent and it is established through binding of the SH3 domain of p85 with the proline-rich region of Cbl (Fang et al., 2001). In order to identify the ubiquitination state of p85 in sorbitol treated and untreated retinas, immunoblots of anti-Ub IPs were probed with anti-p85 antibody. The results indicated a decrease in p85 polyubiquitination in sorbitol-treated retinas compared to the untreated ones (Fig. 12D). This finding suggests that, phosphorylation of Cbl during hyperosmotic stress may act as a ‘switch’ changing the function of Cbl from a E3 ubiquitin ligase to an adaptor function and thereby regulate the activity of PI3K.

Figure 12.

Interaction of Cbl with p85 subunit of PI3K. Sorbitol (1.0 M) treated or untreated retinal lysates were subjected to GST-pull down assay with GST-p85 full-length fusion protein followed by Western blot analysis with anti-Cbl antibody (A). Sorbitol treated and untreated retinal lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-Cbl antibody followed by either Western blot analysis with anti-PY99 antibody (B) or measured the Cbl associated PI3K activity (C). Sorbitol treated and untreated retinal lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-ubiquitin antibody followed by Western blot analysis with anti-p85 subunit of PI3K antibody (D).

DISCUSSION

Our studies clearly indicate that both Akt and MAP kinase pathway are activated in response to sorbitol stress. It has been shown previously that MAPKs acts as glucose transducers for diabetic complications (Tomlinson, 1999). The sorbitol pathway, non-enzymatic glycation of proteins and increased oxidative stress are known to activate protein kinase C which is an effective activator of MAPKs (Tomlinson, 1999). These kinases phosphorylate transcription factors, which in turn alter the balance of gene expression and promote the development of diabetic nephropathy, retinopathy and neuropathy (Tomlinson, 1999). The normal retinal IR exhibits high constitutive activity that is reduced in diabetes (Reiter et al., 2006). The diabetic rat retina further shows loss of PI3K, Akt1 and Akt-3, mTOR and p70S6K activities and increased GSK3β activity (Reiter and Gardner, 2003). Elevated levels of sorbitol have been shown to be implicated in the pathogenesis of diabetic retinopathy (Mizutani et al., 1998;Lorenzi and Gerhardinger, 2001;Asnaghi et al., 2003;Dagher et al., 2004;Lorenzi, 2007). The rate limiting step in the pathway, aldose reductase which reduces the glucose to sorbitol is the major therapeutic target for diabetic retinopathy (Dvornik et al., 1973;Kinoshita et al., 1979;Dahlin et al., 1987;Tomlinson et al., 1992;Chandra et al., 2002;Obrosova et al., 2003;Obrosova et al., 2005;Lorenzi, 2007). In this study, like insulin, sorbitol was found to induce tyrosine phosphorylation of IR and IGF-1R. It was reported previously that insertion of IR into the plasma membrane is necessary for sorbitol-induced IR activation (Ouwens et al., 2001). Consistent with these observation we reported that IRs in rod outer segments of retinas are localized to plasma membrane (Rajala et al., 2007). Further studies, however, are required to understand how the IR kinase activity gets reduced in diabetes.

The organotypic culture system has been successfully used to study protein phosphorylation and provides access to the retina for the addition of exogenous modulators of cellular function(Rajala et al., 2004) We used this system to study the activation of IR, IGF-1, PI3K, Akt and MAP kinase activation under hyperosmotic stress. Inactivation and dephosphorylation of Akt have been reported during hyperosmotic stress (Meier et al., 1998) These studies were done in cell culture with 0.5 M sorbitol and at this concentration, sorbitol activated the MAP kinase but not Akt kinase pathway (Meier et al., 1998) Another independent study also failed to demonstrate the activation of Akt in 3T3L1 adipocytes under hyperosmotic stress using 0.6 M sorbitol (Chen et al., 1997) In agreement with these studies, we did not observe activation of Akt at 0.5 M sorbitol in our ex vivo retinal organ cultures. However, Akt was activated between 1.0 and 3.0 M sorbitol with the maximum being at 3.0 M. These concentrations are higher than those reported previously (Chen et al., 1997;Meier et al., 1998), but provide the same degree of activation we found in vivo light stress (Li et al., 2007), suggesting that sorbitol-induced hyperosmotic stress may mimic the in vivo light-stress model. Hyperosmotic-stress has been related to the pathogenesis of retinal detachment in diabetic retinopathy (Quintyn and Brasseur, 2004;Marmor et al., 1980;Ola et al., 2006) and the sorbitol-induced ex vivo cultures may be useful to study the molecular signaling pathway(s) involved in diabetic retinopathy..

In our study, we observed that 3.0 M sorbitol induced the activation of Akt. Inactivation and dephosphorylation of Akt have been reported during hyperosmotic stress (Meier et al., 1998). Our observation of Akt activation suggests that 3.0 M sorbitol could inhibit the protein phosphatase(s) which results in the activation of Akt. To address whether sorbitol could activate Akt signaling or inhibition of phosphatase(s) which indirectly block the dephosphorylation of Akt, we measured the phosphatase activity in hyperosmotic stress. Our results indicate a significant increase in the total phosphatase activity in hyperosomotic stress. To distinguish the activity of serine/threonine phosphatase activity from protein tyrosine phosphatase (PTP), we used sodium vanadate to inhibit the PTPase activity and the results still indicate a significant increase in serine/threonine phosphatase activity. These studies clearly suggest that the observed activation of Akt in hyperosmotic stress is not due to the inhibition of phosphatase(s).

In the present study, in response to sorbitol, we have observed increased activation of PI3K through IR activation. In some neuronal cell types, such as cerebellar granular neurons (59) and PC-12 cells (60), receptor activation of PI3K has been shown to protect these cells from stress-induced neurodegeneration. Further, IR activation has been shown to rescue retinal neurons from apoptosis through a phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) cascade (Barber et al., 2001;Barber et al., 1998). We have previously reported that under physiological conditions, light-induced the tyrosine phosphorylation of retinal IR which leads to the activation of PI3K (Rajala et al., 2002). The earlier studies along with the results from the present study clearly suggests that sorbitol also induces the activation of PI3K associated with the tyrosine phosphorylated IR.

In hyperosomotic stress we have observed both PI3K-dependent and independent activation of Akt. The PI3K inhibitor LY294002 was found to inhibit the insulin-induced activation of Akt but the same inhibitor failed to inhibit the sorbitol-induced activation of Akt. Activation of PI3K/Akt pathway contributes to cell survival (Datta et al., 1999), however, it has been shown that dopamine induced the PI3K-indepndent activation of Akt in striated neurons (Brami-Cherrier et al., 2002). These results suggest that sorbitol-induced activation of Akt might also be regulated through PI3K-independent mechanism. Consistent with this hypothesis, we have observed an increased tyrosine phosphorylation of several proteins in the retina under hyperosmotic stress. Further, HNMP3, an inhibitor of IR kinase activity has no effect on sorbitol-induced Akt activation. However, genestin, a global tyrosine kinase inhibitor was found to block the sorbitol-induced activation of Akt. It appears from this data that sorbitol-induced Akt activation is mediated through a receptor tyrosine kinase(s), but not IR. The observed Akt activation is not mediated through Src family non-receptor tyrosine kinases due to the fact that inhibitors of this family failed to block the sorbitol-induced Akt activation. Increased protein tyrosine phosphorylation in the retina after ischemic-reperfusion injury and genestin, ameliorates retinal degeneration after ischemia-reperfusion injury in rats (Hayashi et al., 1997;Hayashi et al., 1996). These results further support our findings that Akt activation could be trigged in response to stress and retinal injury.

The ability of osmotic shock to directly stimulate tyrosine phosphorylation events was confirmed by phosphotyrosine immunoblotting. Several discrete tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins in the range of 115-170 kDa and 41-79 kDa were clearly induced by osmotic shock treatment. Previous studies have also reported the activation of tyrosine phosphorylation in response to hyperosmotic stress (Chen et al., 1997;Hresko and Mueckler, 2000;Janez et al., 2000). We have probed the phosphotyrosine immunoblots with known tyrosine phosphorylated proteins such as PYK2, FAK, Na+ K+ ATPase, EGFR, JAK2, TYK2 PDE6beta, HSP90, cSrc and Grb2-associated binder 1 (Gab-1). Under our experimental conditions, except Gab1, all other proteins were not tyrosine phosphorylated in sorbitol-induced stress conditions. The Grb2 associated binder Gab-1 is shown to be tyrosine phosphorylated following sorbitol stimulation (Janez et al., 2000). We found that Gab1 is rapidly tyrosine phosphorylated immediately after sorbitol treatment and after 5 min, the phosphorylation was greatly diminished (data not shown). We have also demonstrated in this study that genestin completely blocks the Akt activation; which suggests that Akt activation may be signaled through Gab1. Gab-1 is phosphorylated on tyrosine after stimulation with insulin and several growth factors (Rocchi et al., 1998;Janez et al., 2000). It possesses 16 potential phosphotyrosine sites, some of which could serve as binding sites for SH2 domains of the p85 regulatory subunit of PI3K, Grb2, phospholipase C-γ, Nck, and SHP-2 (Schlessinger and Lemmon, 2003;Liu and Rohrschneider, 2002;Gual et al., 2000;Rocchi et al., 1998). It has been shown previously that Gab-1 mediates the neurite outgrowth, DNA synthesis, and survival in PC12 cells (Korhonen et al., 1999). Further, overexpression of Gab-1 has shown to inhibit apoptosis in PC12 cells (Holgado-Madruga et al., 1997). Therefore, it is tempting to speculate that decreased phosphorylation of Gab1 could be a contributory factor for diabetic retinopathy

In this study, we report the specific activation of Akt2 in response to hyperosmotic stress. Consistent with this hypothesis is our earlier finding that Akt2 knockout mice exhibit a greater sensitivity to light-induced retinal degeneration, but not Akt1 knockout mice (Li et al., 2007). Further, mice lacking Akt2 have defects in glucose metabolism that ultimately lead to hyperglycemia and hyperinsulinemia (Cho et al., 2001b; Garofalo et al., 2003). These studies clearly suggest the importance of Akt2 in both light-induced retinal degeneration and sorbitol-induced stress.

In the current study, we observed that sorbitol-induced the tyrosine phosphorylation of Cbl and this activation leads to the binding of p85 subunit of PI3K, as we observed an increased Cbl associated PI3K activity in ex vivo retinal organ cultures. Although a small fraction of Cbl is constitutively phosphorylated and associated with PI3K, it appears that a more significant fraction of Cbl could potentially negatively regulate p85 by polyubiquitination and degradation as demonstrated in our sorbitol untreated control retinas.

Cbl is a ubiquitously expressed cytosolic protein characterized as both, an adaptor protein and an E3 ubiquitin ligase. Cbl protein has a tyrosine kinase binding (TKB) domain, proline-rich region and five tyrosine phosphorylation sites; Cbl is able to bind to protein tyrosine kinases (PTK), SH3 and SH2 domain containing proteins, respectively (Swaminathan et al., 2007;Swaminathan and Tsygankov, 2006;Meisner et al., 1995);Meisner, 1995 1543 /id;Fukazawa, 1995 3 /id}. Cbl also contains the RING finger domain and a ubiquitin-associated domain which allow for ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of activated PTK (Levkowitz et al., 1999;Meisner et al., 1997). Stress, extracellular stimuli, growth factors and hormones stimulate tyrosine phosphorylation of Cbl. Under certain cellular conditions phosphorylated Cbl acts as an adaptor protein and binds to SH2 domain-containing proteins such as Vav guanine nucleotide exchange factor, p85 subunit of PI3K, and Crk proteins to propagate downstream signaling (Miyake et al., 1997;Feshchenko et al., 1998). However, previous findings showed that tyrosine phosphorylation of both Cbl and EGFR tyrosine kinase were necessary for binding, ubiquitination and degradation of an activated receptor (Levkowitz et al., 1999).

Interaction between p85 subunit of PI3K and Cbl is phosphorylation-dependent and independent. Phosphorylation of Tyr-731 of Cbl is essential for its binding to SH2 domains of p85 (Feshchenko et al., 1998;Swaminathan et al., 2007). . Tyrosine phosphorylation significantly increase p85-Cbl binding in membrane fractions when compared to the cytosolic fractions of v-Abl-transformed 3T3 fibroblasts and thus further facilitating PI3K/Rho downstream cytoskeletal effects (Swaminathan et al., 2007). . Another study has shown that the two SH2 domains of p85 were dispensable for p85 and Cbl interaction, subsequent ubiquitination and proteasome degradation therefore suggesting phosphorylation-independent binding (Fang et al., 2001). The same study proved that in Jurkat T cell line, the SH3 domain of p85 and the proline-rich region of Cbl were necessary for the binding of the two proteins and further ubiquitination of p85 by the RING finger domain of Cbl.

Diabetic model studies have shown that chronic and increased sorbitol secretion by the cells establishes a hyperosmotic environment fatal to cell survival and viability. The elevated erythrocyte sorbitol levels were found in diabetic patients with developing diabetic retinopathy (DR), a leading cause of blindness (Reddy et al., 2008). Both insulin and sorbitol-induced hyperosmotic shock increased intrinsic tyrosine kinase activity of insulin receptor (IR) followed by transient tyrosine phosphorylation of insulin-receptor substrate-1 (IRS-1) and Cbl (Rajala and Anderson, 2001;Ahmed et al., 2000).. Tyrosine phosphorylated IRS-1 and Cbl harbor signaling proteins involved in activation of PI3K/Akt survival pathway and F-actin polymerization, respectively (Strawbridge et al., 2006). Previous studies have shown that type 2 diabetes, obesity, metabolic syndrome X and age related insulin resistance were characterized by elevated levels of vasoactive peptide endothelin-1 (ET-1) (Sayama et al., 1999;Ferri et al., 1995;Ferri et al., 1997).. ET-1 peptide induced defects in lipid membrane, impaired PI3K signaling, reduced tyrosine phosphorylation of Cbl and F-actin polymerization as well as GLUT4 trafficking when added to insulin- or sorbitol-incubation conditions; thus, ET-1 challenges and overwrites protective role of Cbl (Strawbridge et al., 2006). Taken together, previous and our current findings suggest that under normal conditions Cbl negatively regulates p85 whereby it potentially minimizes the available PI3K pool utilized for basal signaling by RTK and non-RTK. In our in vitro hyperosmolarity stress model, Cbl becomes tyrosine phosphorylated and takes on a role of an adaptor protein aiding to maximize and recruit PI3K necessary for execution of downstream survival pathways. In addition, our laboratory findings show an increase IR tyrosine activity and PI3K/Akt survival signals under the same conditions. Further studies will help us elucidate the function of Cbl as a neuroprotector involved in maintaining cell integrity and viability under the compromising hyperosmotic conditions characteristic of diabetic models.

ACKNOWLEDGEMNTS

The project described was supported by grants from the National Eye Institute (R01EY016507) and the National Center for Research Resources (P20RR17703). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Research Resources, the National Eye Institute, or the National Institutes of Health. The authors thank Dr. Yogita Kanan for reading this manuscript.

ABBREVIATIONS

- IR

insulin receptor

- PI3K

phosphoinositide 3-kinase

- IRβ

IR beta subunit

- IGF 1R

insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor

- SDS-PAGE

sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- ROS

rod outer segments

- IPs

immunoprecipitates

- Grb2

growth factor receptor-bound protein 2

- Gab-1

Grb2-assoicated binder 1

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahmed Z, Smith BJ, Pillay TS. The APS adapter protein couples the insulin receptor to the phosphorylation of c-Cbl and facilitates ligand-stimulated ubiquitination of the insulin receptor. FEBS Lett. 2000;475:31–34. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01621-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asnaghi V, Gerhardinger C, Hoehn T, Adeboje A, Lorenzi M. A role for the polyol pathway in the early neuroretinal apoptosis and glial changes induced by diabetes in the rat. Diabetes. 2003;52:506–511. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.2.506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barber AJ, Lieth E, Khin SA, Antonetti DA, Buchanan AG, Gardner TW. Neural apoptosis in the retina during experimental and human diabetes. Early onset and effect of insulin. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:783–791. doi: 10.1172/JCI2425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barber AJ, Nakamura M, Wolpert EB, Reiter CE, Seigel GM, Antonetti DA, Gardner TW. Insulin rescues retinal neurons from apoptosis by a phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt-mediated mechanism that reduces the activation of caspase-3. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:32814–32821. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104738200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barnett PA, Gonzalez RG, Chylack LT, Jr., Cheng HM. The effect of oxidation on sorbitol pathway kinetics. Diabetes. 1986;35:426–432. doi: 10.2337/diab.35.4.426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brami-Cherrier K, Valjent E, Garcia M, Pages C, Hipskind RA, Caboche J. Dopamine induces a PI3-kinase-independent activation of Akt in striatal neurons: a new route to cAMP response element-binding protein phosphorylation. J Neurosci. 2002;22:8911–8921. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-20-08911.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chandra D, Jackson EB, Ramana KV, Kelley R, Srivastava SK, Bhatnagar A. Nitric oxide prevents aldose reductase activation and sorbitol accumulation during diabetes. Diabetes. 2002;51:3095–3101. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.10.3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen D, Elmendorf JS, Olson AL, Li X, Earp HS, Pessin JE. Osmotic shock stimulates GLUT4 translocation in 3T3L1 adipocytes by a novel tyrosine kinase pathway. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:27401–27410. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.43.27401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng H, Kartenbeck J, Kabsch K, Mao X, Marques M, Alonso A. Stress kinase p38 mediates EGFR transactivation by hyperosmolar concentrations of sorbitol. J Cell Physiol. 2002;192:234–243. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dagher Z, Park YS, Asnaghi V, Hoehn T, Gerhardinger C, Lorenzi M. Studies of rat and human retinas predict a role for the polyol pathway in human diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes. 2004;53:2404–2411. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.9.2404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dahlin LB, Archer DR, McLean WG. Treatment with an aldose reductase inhibitor can reduce the susceptibility of fast axonal transport following nerve compression in the streptozotocin-diabetic rat. Diabetologia. 1987;30:414–418. doi: 10.1007/BF00292544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Datta SR, Brunet A, Greenberg ME. Cellular survival: a play in three Akts. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2905–2927. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.22.2905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dvornik E, Simard-Duquesne N, Krami M, Sestanj K, Gabbay KH, Kinoshita JH, Varma SD, Merola LO. Polyol accumulation in galactosemic and diabetic rats: control by an aldose reductase inhibitor. Science. 1973;182:1146–1148. doi: 10.1126/science.182.4117.1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fang D, Wang HY, Fang N, Altman Y, Elly C, Liu YC. Cbl-b, a RING-type E3 ubiquitin ligase, targets phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase for ubiquitination in T cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:4872–4878. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008901200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferri C, Bellini C, Desideri G, Baldoncini R, Properzi G, Santucci A, De Mattia G. Circulating endothelin-1 levels in obese patients with the metabolic syndrome. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 1997;105(Suppl 2):38–40. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1211794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferri C, Bellini C, Desideri G, Di Francesco L, Baldoncini R, Santucci A, De Mattia G. Plasma endothelin-1 levels in obese hypertensive and normotensive men. Diabetes. 1995;44:431–436. doi: 10.2337/diab.44.4.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feshchenko EA, Langdon WY, Tsygankov AY. Fyn, Yes, and Syk phosphorylation sites in c-Cbl map to the same tyrosine residues that become phosphorylated in activated T cells. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:8323–8331. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.14.8323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gabbay KH. Role of sorbitol pathway in neuropathy. Adv Metab Disord. 1973a;2(Suppl32) doi: 10.1016/b978-0-12-027362-1.50049-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gabbay KH. The sorbitol pathway and the complications of diabetes. N Engl J Med. 1973b;288:831–836. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197304192881609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gabbay KH. Hyperglycemia, polyol metabolism, and complications of diabetes mellitus. Annu Rev Med. 1975;26:521–536. doi: 10.1146/annurev.me.26.020175.002513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gual P, Giordano S, Williams TA, Rocchi S, Van Obberghen E, Comoglio PM. Sustained recruitment of phospholipase C-gamma to Gab1 is required for HGF-induced branching tubulogenesis. Oncogene. 2000;19:1509–1518. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gustavsson J, Parpal S, Karlsson M, Ramsing C, Thorn H, Borg M, Lindroth M, Peterson KH, Magnusson KE, Stralfors P. Localization of the insulin receptor in caveolae of adipocyte plasma membrane. FASEB J. 1999;13:1961–1971. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hayashi A, Koroma BM, Imai K, de Juan E., Jr Increase of protein tyrosine phosphorylation in rat retina after ischemia-reperfusion injury. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1996;37:2146–2156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hayashi A, Weinberger AW, Kim HC, de Juan E., Jr Genistein, a protein tyrosine kinase inhibitor, ameliorates retinal degeneration after ischemia-reperfusion injury in rat. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1997;38:1193–1202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holgado-Madruga M, Moscatello DK, Emlet DR, Dieterich R, Wong AJ. Grb2-associated binder-1 mediates phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase activation and the promotion of cell survival by nerve growth factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:12419–12424. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.23.12419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hresko RC, Mueckler M. A novel 68-kDa adipocyte protein phosphorylated on tyrosine in response to insulin and osmotic shock. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:18114–18120. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001937200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Janez A, Worrall DS, Imamura T, Sharma PM, Olefsky JM. The osmotic shock-induced glucose transport pathway in 3T3-L1 adipocytes is mediated by gab-1 and requires Gab-1-associated phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase activity for full activation. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:26870–26876. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001654200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kinoshita JH, Fukushi S, Kador P, Merola LO. Aldose reductase in diabetic complications of the eye. Metabolism. 1979;28:462–469. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(79)90057-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Korhonen JM, Said FA, Wong AJ, Kaplan DR. Gab1 mediates neurite outgrowth, DNA synthesis, and survival in PC12 cells. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:37307–37314. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.52.37307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lederle FA. Epidemiology of constipation in elderly patients. Drug utilisation and cost-containment strategies. Drugs Aging. 1995;6:465–469. doi: 10.2165/00002512-199506060-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Levkowitz G, Waterman H, Ettenberg SA, Katz M, Tsygankov AY, Alroy I, Lavi S, Iwai K, Reiss Y, Ciechanover A, Lipkowitz S, Yarden Y. Ubiquitin ligase activity and tyrosine phosphorylation underlie suppression of growth factor signaling by c-Cbl/Sli-1. Mol Cell. 1999;4:1029–1040. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80231-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li G, Anderson RE, Tomita H, Adler R, Liu X, Zack DJ, Rajala RV. Nonredundant role of Akt2 for neuroprotection of rod photoreceptor cells from light-induced cell death. J Neurosci. 2007;27:203–211. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0445-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu Y, Rohrschneider LR. The gift of Gab. FEBS Lett. 2002;515:1–7. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)02425-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lorenzi M. The polyol pathway as a mechanism for diabetic retinopathy: attractive, elusive, and resilient. Exp Diabetes Res. 2007;2007:61038. doi: 10.1155/2007/61038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lorenzi M, Gerhardinger C. Early cellular and molecular changes induced by diabetes in the retina. Diabetologia. 2001;44:791–804. doi: 10.1007/s001250100544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marchenko SM, Sage SO. Hyperosmotic but not hyposmotic stress evokes a rise in cytosolic Ca2+ concentration in endothelium of intact rat aorta. Exp Physiol. 2000;85:151–157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marmor MF, Martin LJ, Tharpe S. Osmotically induced retinal detachment in the rabbit and primate. Electron miscoscopy of the pigment epithelium. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1980;19:1016–1029. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Meier R, Thelen M, Hemmings BA. Inactivation and dephosphorylation of protein kinase Balpha (PKBalpha) promoted by hyperosmotic stress. EMBO J. 1998;17:7294–7303. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.24.7294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meisner H, Conway BR, Hartley D, Czech MP. Interactions of Cbl with Grb2 and phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase in activated Jurkat cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:3571–3578. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.7.3571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meisner H, Daga A, Buxton J, Fernandez B, Chawla A, Banerjee U, Czech MP. Interactions of Drosophila Cbl with epidermal growth factor receptors and role of Cbl in R7 photoreceptor cell development. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:2217–2225. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.4.2217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miyake S, Lupher ML, Jr., Andoniou CE, Lill NL, Ota S, Douillard P, Rao N, Band H. The Cbl protooncogene product: from an enigmatic oncogene to center stage of signal transduction. Crit Rev Oncog. 1997;8:189–218. doi: 10.1615/critrevoncog.v8.i2-3.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mizutani M, Gerhardinger C, Lorenzi M. Muller cell changes in human diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes. 1998;47:445–449. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.47.3.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Narayanan S. Aldose reductase and its inhibition in the control of diabetic complications. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 1993;23:148–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Obrosova IG, Minchenko AG, Vasupuram R, White L, Abatan OI, Kumagai AK, Frank RN, Stevens MJ. Aldose reductase inhibitor fidarestat prevents retinal oxidative stress and vascular endothelial growth factor overexpression in streptozotocin-diabetic rats. Diabetes. 2003;52:864–871. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.3.864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Obrosova IG, Pacher P, Szabo C, Zsengeller Z, Hirooka H, Stevens MJ, Yorek MA. Aldose reductase inhibition counteracts oxidative-nitrosative stress and poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase activation in tissue sites for diabetes complications. Diabetes. 2005;54:234–242. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.1.234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ola MS, Berkich DA, Xu Y, King MT, Gardner TW, Simpson I, LaNoue KF. Analysis of glucose metabolism in diabetic rat retinas. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2006;290:E1057–E1067. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00323.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ouwens DM, Gomes de Mesquita DS, Dekker J, Maassen JA. Hyperosmotic stress activates the insulin receptor in CHO cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2001;1540:97–106. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(01)00126-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pritchard S, Erickson GR, Guilak F. Hyperosmotically induced volume change and calcium signaling in intervertebral disk cells: the role of the actin cytoskeleton. Biophys J. 2002;83:2502–2510. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75261-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Quintyn JC, Brasseur G. Subretinal fluid in primary rhegmatogenous retinal detachment: physiopathology and composition. Surv Ophthalmol. 2004;49:96–108. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2003.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rajala A, Anderson RE, Ma JX, Lem J, Al Ubaidi MR, Rajala RV. G-protein-coupled Receptor Rhodopsin Regulates the Phosphorylation of Retinal Insulin Receptor. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:9865–9873. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608845200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rajala RV, Anderson RE. Interaction of the insulin receptor beta-subunit with phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase in bovine ROS. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42:3110–3117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rajala RV, McClellan ME, Ash JD, Anderson RE. In vivo regulation of phosphoinositide 3-kinase in retina through light-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of the insulin receptor beta-subunit. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:43319–43326. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206355200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rajala RV, McClellan ME, Chan MD, Tsiokas L, Anderson RE. Interaction of the Retinal Insulin Receptor beta-Subunit with the P85 Subunit of Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase. Biochemistry. 2004;43:5637–5650. doi: 10.1021/bi035913v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Reddy GB, Satyanarayana A, Balakrishna N, Ayyagari R, Padma M, Viswanath K, Petrash JM. Erythrocyte aldose reductase activity and sorbitol levels in diabetic retinopathy. Mol Vis. 2008;14:593–601. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Reiter CE, Gardner TW. Functions of insulin and insulin receptor signaling in retina: possible implications for diabetic retinopathy. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2003;22:545–562. doi: 10.1016/s1350-9462(03)00035-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Reiter CE, Sandirasegarane L, Wolpert EB, Klinger M, Simpson IA, Barber AJ, Antonetti DA, Kester M, Gardner TW. Characterization of insulin signaling in rat retina in vivo and ex vivo. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2003;285:E763–E774. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00507.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Reiter CE, Wu X, Sandirasegarane L, Nakamura M, Gilbert KA, Singh RS, Fort PE, Antonetti DA, Gardner TW. Diabetes reduces basal retinal insulin receptor signaling: reversal with systemic and local insulin. Diabetes. 2006;55:1148–1156. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.55.04.06.db05-0744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rocchi S, Tartare-Deckert S, Murdaca J, Holgado-Madruga M, Wong AJ, Van Obberghen E. Determination of Gab1 (Grb2-associated binder-1) interaction with insulin receptor-signaling molecules. Mol Endocrinol. 1998;12:914–923. doi: 10.1210/mend.12.7.0141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sayama H, Nakamura Y, Saito N, Konoshita M. Does the plasma endothelin-1 concentration reflect atherosclerosis in the elderly? Gerontology. 1999;45:312–316. doi: 10.1159/000022111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schlessinger J, Lemmon MA. SH2 and PTB domains in tyrosine kinase signaling. Sci STKE. 2003;2003:RE12. doi: 10.1126/stke.2003.191.re12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Strawbridge AB, Elmendorf JS, Mather KJ. Interactions of endothelin and insulin: expanding parameters of insulin resistance. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2006;2:317–327. doi: 10.2174/157339906777950642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Swaminathan G, Feshchenko EA, Tsygankov AY. c-Cbl-facilitated cytoskeletal effects in v-Abl-transformed fibroblasts are regulated by membrane association of c-Cbl. Oncogene. 2007;26:4095–4105. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Swaminathan G, Tsygankov AY. The Cbl family proteins: ring leaders in regulation of cell signaling. J Cell Physiol. 2006;209:21–43. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Szwergold BS, Kappler F, Brown TR. Identification of fructose 3-phosphate in the lens of diabetic rats. Science. 1990;247:451–454. doi: 10.1126/science.2300805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Takai A, Mieskes G. Inhibitory effect of okadaic acid on the p-nitrophenyl phosphate phosphatase activity of protein phosphatases. Biochem J. 1991;275(Pt 1):233–239. doi: 10.1042/bj2750233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tomlinson DR. Mitogen-activated protein kinases as glucose transducers for diabetic complications. Diabetologia. 1999;42:1271–1281. doi: 10.1007/s001250051439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tomlinson DR, Stevens EJ, Diemel LT. Aldose reductase inhibitors and their potential for the treatment of diabetic complications. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1994;15:293–297. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(94)90010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tomlinson DR, Willars GB, Carrington AL. Aldose reductase inhibitors and diabetic complications. Pharmacol Ther. 1992;54:151–194. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(92)90031-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Vinores SA, Campochiaro PA, Williams EH, May EE, Green WR, Sorenson RL. Aldose reductase expression in human diabetic retina and retinal pigment epithelium. Diabetes. 1988;37:1658–1664. doi: 10.2337/diab.37.12.1658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Williamson JR, Chang K, Frangos M, Hasan KS, Ido Y, Kawamura T, Nyengaard JR, van den EM, Kilo C, Tilton RG. Hyperglycemic pseudohypoxia and diabetic complications. Diabetes. 1993;42:801–813. doi: 10.2337/diab.42.6.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]