Abstract

The deeper part of neocortical layer VI is dominated by nonpyramidal neurons, which lack a prominent vertically ascending dendrite and predominantly establish corticocortical connections. These neurons were studied in rat neocortical slices using patch-clamp, single-cell reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction, and biocytin labeling. The majority of these neurons expressed the vesicular glutamate transporter but not glutamic acid decarboxylase, suggesting that a high proportion of layer VI nonpyramidal neurons are glutamatergic. Indeed, they exhibited numerous dendritic spines and established asymmetrical synapses. Our sample of glutamatergic nonpyramidal neurons displayed a wide variety of somatodendritic morphologies and a subset of these cells expressed the Nurr1 mRNA, a marker for ipsilateral, but not commissural corticocortical projection neurons in layer VI. Comparison with spiny stellate and pyramidal neurons from other layers showed that glutamatergic neurons consistently exhibited a low occurrence of GABAergic interneuron markers and regular spiking firing patterns. Analysis of electrophysiological diversity using unsupervised clustering disclosed three groups of cells. Layer V pyramidal neurons were segregated into a first group, whereas a second group consisted of a subpopulation of layer VI neurons exhibiting tonic firing. A third heterogeneous cluster comprised spiny stellate, layer II/III pyramidal, and layer VI neurons exhibiting adaptive firing. The segregation of layer VI neurons in two different clusters did not correlate either with their somatodendritic morphologies or with Nurr1 expression. Our results suggest that electrophysiological similarities between neocortical glutamatergic neurons extend beyond layer positioning, somatodendritic morphology, and projection specificity.

INTRODUCTION

Neurons of the mammalian neocortex are commonly classified as pyramidal or nonpyramidal according to their morphology (Fairén et al. 1984; Peters and Jones 1984). Pyramidal neurons are excitatory projection neurons. They exhibit a high density of dendritic spines, form asymmetrical synapses, and express the vesicular glutamate transporter VGluT1 (Gallopin et al. 2006; Hill et al. 2007), which largely predominates over other vesicular glutamate transporters in the neocortex (Fremeau Jr et al. 2001; Fujiyama et al. 2001; Herzog et al. 2001, 2004) and determines the glutamatergic phenotype in neurons (Takamori et al. 2000). On the other hand, most nonpyramidal-shaped neurons express glutamic acid decarboxylase (Houser et al. 1983) and are inhibitory interneurons, which project locally. Throughout this study, the use of the term pyramidal neurons will be restricted to “typical” pyramidal cells, characterized by a prominent apical dendrite extending vertically from a conical soma toward the pial surface (Peters and Jones 1984). In addition to pyramidal cells, the neocortex contains at least two other morphological types of excitatory neurons, the star pyramidal and the spiny stellate neurons (Jones 1975; Lund 1984), the latter being nonpyramidal cells with multipolar somatodendritic morphology that mainly project locally. These excitatory neurons exhibit a high density of dendritic spines, form asymmetrical synapses, and their glutamatergic nature has been functionally assessed (Feldmeyer et al. 1999; Lübke et al. 2000; Schubert et al. 2003; Staiger et al. 2004).

The neocortex can be partitioned into six cytoarchitecturally distinct horizontal layers, among which layers II/III and V contain a high density of pyramidal neurons. Layer VI contains many pyramidal cells in its upper part, whereas its deeper part is dominated by polymorphic nonpyramidal neurons (reviewed in Tömböl 1984). A significant proportion of layer VI nonpyramidal neurons is immunoreactive for the main glutamate synthesizing enzyme, phosphate-activated glutaminase (van der Gucht et al. 2003), suggesting that layer VI contains a large population of excitatory nonpyramidal neurons. Indeed, diverse morphological types of layer VI nonpyramidal neurons exhibit a high density of dendritic spines (Tömböl 1984). These neurons predominantly project corticocortically toward ipsilateral or contralateral targets (Prieto and Winer 1999; Zhang and Deschênes 1997), a projection pattern associated with expression of the orphan nuclear receptor Nurr1. Nurr1 is expressed in layer VI neurons projecting to the ipsilateral cortex, but not those projecting to contralateral cortical regions (Arimatsu et al. 2003). Although functional studies have established the existence of excitatory nonpyramidal spiny neurons in layer VI (Mercer et al. 2005), the proportion of polymorphic layer VI nonpyramidal neurons displaying a glutamatergic phenotype has not been thoroughly investigated. Furthermore, relatively few reports describe the electrophysiological properties of layer VI spiny nonpyramidal neurons (Brumberg et al. 2003; Karayannis et al. 2007; Mercer et al. 2005; van Brederode and Snyder 1992).

Here, we studied layer VI nonpyramidal neurons in rat neocortical acute slices using patch-clamp, single-cell reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (scPCR; Lambolez et al. 1992), and histochemical labeling of biocytin-filled neurons. The combined electrophysiological, molecular, and morphological analysis showed that layer VI nonpyramidal neurons are predominantly glutamatergic. Comparison of these neurons with pyramidal and spiny stellate cells from other layers showed that all glutamatergic neuron exhibit a low occurrence of GABAergic interneuron markers. Unsupervised cluster analysis of the electrophysiological diversity of neocortical glutamatergic neurons aggregated a subgroup of layer VI neurons with spiny stellate and layer II/III pyramidal cells, whereas the remaining layer VI neurons formed a distinct cluster.

METHODS

Slice preparation

All experiments were carried out in accordance with the guidelines published in the European Communities Council Directive of 24 November 1986 (86/609/EEC). Young Wistar rats (18 ± 2 days old, range 14–21) were decapitated and brains were quickly removed and placed into cold (∼4°C) oxygenated artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) containing (in mM): 126 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 26 NaHCO3, 20 glucose, 5 pyruvate, and 1 kynurenic acid (nonspecific glutamate receptor antagonist; Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Parasagittal 300-μm-thick sections of cerebral sensorimotor cortex were prepared as described previously (Cauli et al. 1997). Slices were collected and subsequently transferred to a holding chamber containing ACSF saturated with 95% O2-5% CO2 and held at room temperature. Slices were allowed to equilibrate for 1 h before recordings.

Whole cell recordings

Individual slices were then transferred to a recording chamber placed under a microscope (Olympus BX51WI). Slices were maintained immersed and continuously superfused at 1–2 ml/min with oxygenated ACSF at room temperature. Patch micropipettes (3–5 MΩ) were pulled from borosilicate glass capillaries (OD, 1.5 mm; ID, 0.86 mm; Harvard Apparatus, Les Ulis, France) on a Brown-Flaming micropipette puller (Model PP-83, Narishige, Tokyo, Japan). Electrodes were filled with 8 μl of internal solution containing (in mM): 144 K-gluconate, 3 MgCl2, 0.5 EGTA, and 10 HEPES plus 2 mg/ml biocytin (Sigma). The pH was adjusted to 7.2 and osmolarity to 285/295 mOsm. Whole cell recordings were made from neocortical neurons selected under infrared video microscopy (Stuart et al. 1993) using a patch-clamp amplifier (Multiclamp 700B, Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) connected to a Digidata 1322A interface board (Molecular Devices). Signals were amplified and collected using the data-acquisition software pClamp 9.2 (Molecular Devices). Resting membrane potential was measured just after passing in whole cell configuration and only cells with a resting membrane potential more hyperpolarized than −50 mV were analyzed. Membrane potentials were not corrected for junction potential. Cells were maintained at a holding potential of −60 mV by continuous current injection and their firing behavior was tested by applying depolarizing current pulses. Signals were filtered at 5 kHz, digitized at 10 kHz, saved to a personal computer, and analyzed off-line with Clampfit 9.2 software (Molecular Devices).

Twelve electrophysiological parameters were determined for each neuron. Membrane resistance was measured by applying a hyperpolarizing current pulse (amplitude −50 pA, duration 800 ms). On injection of hyperpolarizing current pulses a “sag,” indicative of a hyperpolarization-activated cationic current (“Ih”), followed the initial hyperpolarization peak. The amplitude of the sag was quantified as a decrease in membrane resistance. Thus membrane resistance was measured when the sag conductance was active (R-sag) and inactive (R-hyp). R-sag was measured as the slope of the linear portion of a current–voltage (I–V) plot, where V was determined at the end of an 800-ms hyperpolarizing current pulse and R-hyp as the slope of the linear portion of an I–V plot, where V was determined as the maximal negative potential during the 800-ms hyperpolarizing pulse. The sag (% membrane resistance decrease) was calculated according to (R-hyp − R-sag)/R-hyp.

Analysis of the waveforms of the first two spikes was performed on action potential (AP) discharges elicited by pulses of depolarizing current in the 50- to 150-pA range. The amplitude of the first two APs (A1 and A2) was measured from the threshold to the peak of the spike. Their duration (D1 and D2) was measured at half-amplitude. The amplitude reduction and the duration increase were calculated according to (A1 − A2)/A1 and (D2 − D1)/D1, respectively. Amplitudes of the afterhyperpolarization (AHP) of the first and the second spikes were measured between the spike threshold and the peak of the AHP. The frequency adaptation parameters were also measured on discharges elicited by application of 800-ms depolarizing current pulses (sampling rate 10 kHz). The instantaneous discharge frequency was determined all along the discharge and plotted as a function of time at all stimulation intensities tested. The instantaneous discharge frequencies between the first two spikes (finitial), 200 ms after the beginning of the discharge (f200) and at the end of the stimulation (ffinal), were then measured. Early and late accommodations were calculated according to (finitial − f200)/finitial and (f200 − ffinal)/f200, respectively. Statistical analysis of adaptation parameters (early and late adaptation) was performed on the values corresponding to an evoked discharge with an initial firing frequency of 50 Hz.

Statistical analyses

Unsupervised cluster analysis was used to classify sampled neocortical neurons without a priori knowledge of the number of groups (Cauli et al. 2000) by combining the 12 electrophysiological variables described earlier. After centering and reducing the data, cluster analysis was performed using squared Euclidean distances and Ward's linkage rules (Ward 1963). A Thorndike critical threshold procedure was used to suggest the number of different clusters in the data set (Thorndike 1953). Descriptive statistics and cluster analysis were calculated with Statistica v 6.0 (StatSoft France, Paris).

The comparison of occurrence of a given molecular marker between populations of VGluT+/GAD− neurons was made according to

|

(1) |

where pa, pb, na, and nb represent the percentage of occurrence (p) and the number of individuals (n) in two populations a and b; p is the percentage of occurrence in the overall population with q = 1 − p; |ɛ| was compared with a normal distribution for statistical significance (Fisher and Yates 1946).

Comparison of the mean numbers of GABAergic interneuron markers expressed per cell in different populations was performed using a Mann–Whitney U test.

Single-cell reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction

At the end of the recording, the cell cytoplasm was aspirated into the recording pipette while maintaining a tight seal. Then, the pipette was removed delicately to allow outside-out patch formation. Next, the content of the pipette was expelled into a test tube and reverse transcription (RT) was performed in a final volume of 10 μl as described previously (Lambolez et al. 1992). Next, two steps of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) were performed essentially as described previously (Cauli et al. 1997). The cDNAs present in 10 μl of the RT reaction first were amplified simultaneously using the primer pairs described in Table 1 (for each primer pair the sense and antisense primers were positioned on two different exons). Taq polymerase (2.5 U; Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and 20 pmol of each primer were added to the buffer supplied by the manufacturer (final volume, 100 μl), and 21 cycles (94°C for 30 s, 60°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s) of PCR were run. Second rounds of PCR were performed using 2 μl of the first PCR product as template. In this second round, each cDNA was amplified individually with a second set of primer pair internal to the primer pair used in the first PCR (nested primers; see Table 1) and positioned on two different exons. Thirty-five PCR cycles were performed (as described earlier). Then 10 μl of each individual PCR were run on a 2% agarose gel, with ΦX174 digested by Hae III as a molecular weight marker and stained with ethidium bromide. The RT-PCR protocol was tested on 500 pg of total RNA purified from rat neocortex. All the transcripts were detected from 500 pg of neocortical RNA. Sizes of the PCR-generated fragments were as predicted by the mRNA sequences (see Table 1). A control for mRNA contamination from surrounding tissue was performed by placing a patch pipette into the slice without establishing a seal. Positive pressure was then interrupted and, following the removal of the pipette, its content was processed as described. No PCR product was obtained using this protocol (n = 20).

TABLE 1.

PCR primers

| Gene | First PCR Primers | Size | Second PCR Nested Primers | Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VGluT1 | cSense, 361: GGCTCCTTTTTCTGGGGGTAC | 259 | cSense, 373: TGGGGGTACATTGTCACTCAGA | 201 |

| #U07609 | cAntisense, 600: CCAGCCGACTCCGTTCTAAG | cAntisense, 553: ATGGCAAGCAGGGTATGTGAC | ||

| GAD65 | aSense, 713: TCTTTTCTCCTGGTGGTGCC | 391 | cSense, 743: TGTACGCCATGCTCATTGCC | 312 |

| #M72422 | aAntisense, 1085: CCCCAAGCAGCATCCACAT | cAntisense, 1032: CAGCTACAGCCAAGAGAGGATCA | ||

| GAD67 | bSense, 529: TACGGGGTTCGCACAGGTC | 600 | cSense, 581: TGGATATCATTGGTTTAGCTGGC | 509 |

| #M76177 | bAntisense, 1110: CCCCAAGCAGCATCCACAT | cAntisense, 1066: TCACATATGTCTGCAATCTCCTGG | ||

| CR | bSense, 142: CTGGAGAAGGCAAGGAAAGGT | 309 | cSense, 157: AAAGGTTCTGGCATGATGTCC | 265 |

| #X66974 | bAntisense, 429: AGGTTCATCATAGGGACGGTTG | cAntisense, 401: TCAGGAGGTCGGACAGAAATC | ||

| CaB | bSense, 134: AGGCACGAAAGAAGGCTGGAT | 432 | cSense, 165: CCTGAGATGAAAACCTTTGTGG | 249 |

| #M27839 | bAntisense, 544: TCCCACACATTTTGATTCCCTG | cAntisense, 391: CACGGTCTTGTTTGCTTTCTCTA | ||

| PV | bSense, 115: AAGAGTGCGGATGATGTGAAGA | 388 | Sense, 151: CTGGACAAAGACAAAAGTGGCT | 244 |

| #M12725 | bAntisense, 480: ATTGTTTCTCCAGCATTTTCCAG | Antisense, 376: AGAAGGGCTGAGATGGGGC | ||

| NPY | bSense, 46: GCCCAGAGCAGAGCACCC | 359 | cSense, 22: CAGAGACCACAGCCCGCC | 303 |

| #M15880 | bAntisense, 292: CAAGTTTCATTTCCCATCACCA | cAntisense, 261: TCTTCAAGCTTGTTCTGGGG | ||

| VIP | bSense, 167: TGCCTTAGCGGAGAATGACA | 286 | cSense, 186: ACGCCCTATTATGATGTGTCCAG | 214 |

| #X02341 | bAntisense, 434: CCTCACTGCTCCTCTTCCCA | cAntisense, 380: TTTGCTTTCTAAGGCGGGTG | ||

| CCK | bSense, 177: CGCACTGCTAGCCCGATACA | 216 | cSense, 192: ATACATCCAGCAGGTCCGCA | 151 |

| #K01259 | bAntisense, 373: TTTCTfCATTCCGCCTCCTCC | cAntisense, 320: TGGGTATTCGTAGTCCTCAGCAC | ||

| SOM | bSense, 43: ATCGTCCTGGCTTTGGGC | 209 | cSense, 75: GCCCTCGGACCCCAGACT | 150 |

| #K02248 | bAntisense, 231: GCCTCATCTCGTCCTGCTCA | cAntisense, 207: TGGGGCAAATCCTCAGGC | ||

| Nurr1 | Sense, 1038: TCAAAACCGAAGAGCCCACA | 250 | Sense, 1061: TCCCTCTCCCCCCTCACC | 204 |

| #M019328 | Antisense, 1268: GGTCAGCAAAGCCAGGAATC | Antisense, 1245: TCTGCCCACCCTCTGATGAT |

Note: Position 1, first base of the start codon.

Bochet et al. (1994);

Cauli et al. (1997),

Gallopin et al. (2006).

Intracellular labeling

Slices containing the recorded neurons filled with biocytin were fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at 4°C. The morphology of the recorded neurons was investigated by histochemical labeling of intracellular biocytin, with Streptavidin Alexafluor 568 (Invitrogen, Cergy Pontoise, France) or diaminobenzidine (DAB).

For Alexafluor 568 staining, slices were washed six times in 0.1 M phosphate buffer for 10 min, rinsed three times in 0.1 M PBS gelatin (0.2%) Triton (0.25%) for 10 min, and incubated with Streptavidin Alexafluor 568 for 4 h. Slices were washed four times in 0.1 M PBS for 10 min and mounted in Vectashield (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Images of labeled cells were captured with a digital camera (Cool Snap Photometrics, Roper Scientific, Ottobrunn, Germany) mounted on a microscope (Leica DMR HC, Wetzlar, Germany) or reconstructed by confocal microscopy (Leica DMI Simil SP5) with excitation at 561 nm and emission at 566–700 nm.

For DAB staining, biocytin-filled neurons were labeled using the avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex (ABC) method (ABC Elite kit; Vector Laboratories). After blocking endogenous peroxidase with 3% H2O2 for 15–30 min, slices were rinsed five times in PBS for 10 min, permeabilized in 2% Triton in PBS for 1 h, and incubated in ABC for 2 h. Incubated slices were washed eight times in 0.1 M PBS for 10 min before immersion in a solution containing 0.05% of 3,3′-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (Sigma) in 0.1 M PBS and 0.02% H2O2. Visualization of DAB staining was monitored under the dissecting microscope and stopped by rinsing the slices five times in PBS for 10 min. The slices were then mounted in aqueous medium (Moviol) and images of the neurons were captured with a digital camera (Qicam from QImaging, Surrey, BC, Canada) mounted on a microscope (Leica DMR HC, Leica Microsystems, Rueil-Malmaison, France). Reconstructions and morphological analysis of representative neurons were made with the Neurolucida tracing system (Microbrightfield Europe, Magdeburg, Germany) attached to a Leica DMR HC microscope using a ×100 oil-immersion objective.

For correlated light- and electron microscopy, slices containing the recorded neurons filled with biocytin were fixed in 2.5% paraformaldehyde, 1.25% glutaraldehyde, and 15% (vol/vol) saturated picric acid in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). Visualization of biocytin was performed as described (Tamás et al. 1997). Three-dimensional light microscopic reconstructions were carried out using Neurolucida with ×100 objective. Correlated light- and electron microscopy was performed as described earlier (Szabadics et al. 2001; Tamás et al. 1997).

RESULTS

Characterization of VGluT+/GAD+ nonpyramidal neurons from layer VI

Nonpyramidal neurons from neocortical layer VI (n = 114), identified under infrared videomicroscopy as lacking a prominent apical dendrite, were electrophysiologically characterized and subsequently analyzed by scPCR (see methods). The nonpyramidal morphology of the recorded neurons was confirmed by histochemical labeling of intracellular biocytin (see methods). Twelve electrophysiological parameters were determined for each neuron and the scPCR protocol was designed to detect the expression of mRNAs encoding the vesicular glutamate transporter (VGluT1) and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA)–synthesizing enzymes (glutamic acid decarboxylase, GAD 65 and GAD 67), in addition to the following markers of GABAergic interneuron diversity (Cauli et al. 1997; Kubota et al. 1994): calcium binding proteins calretinin (CR), calbindin (CaB), and parvalbumin (PV); and neuropeptides vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP), somatostatin (SOM), cholecystokinin (CCK), and neuropeptide Y (NPY). Expression of the Nurr1 mRNA was additionally tested in a subset of 24 neurons.

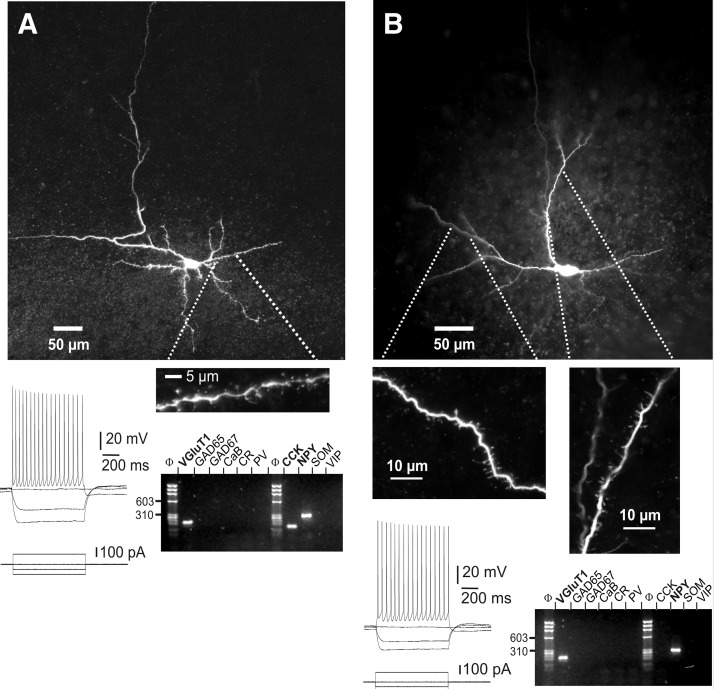

We found that the majority of layer VI nonpyramidal neurons (n = 71 of 114, 62%) were negative for GAD 65 and GAD 67 (GAD−), but VGluT1 positive (VGluT+) on scPCR analysis. The 43 remaining cells were GAD 65 and/or GAD 67 positive and were discarded from the present study. The nonpyramidal morphology was confirmed for 34 of the 71 VGluT+/GAD− neurons following biocytin labeling. All lacked the prominent apical dendrite typical of pyramidal neurons and their somata were localized in layer VI at a maximum of 350 μm from the white matter. Numerous dendritic spines were observed on all VGluT+/GAD− neurons analyzed with confocal microscopy (n = 8). This indicates that deep layer VI contains a high proportion of putative glutamatergic nonpyramidal neurons. Figure 1 displays two examples of the morphological, electrophysiological, and molecular analysis of VGluT+/GAD− nonpyramidal neurons from layer VI. Both cells, located in deep layer VI close to the white matter, lacked a prominent apical dendrite. Consistent with their identification as putative glutamatergic neurons, numerous spines were observed on the dendrites of both neurons. Analysis of AP firing patterns showed that both neurons exhibited long-duration APs, relatively small AHP, and decrease of their AP amplitude and frequency along the discharge. These electrophysiological properties define the broad class of regular-spiking neurons (RS), to which glutamatergic neurons from other layers also belong (Connors and Gutnick 1990; see also Figs. 5 and 6). Molecular analysis showed that both nonpyramidal neurons expressed the VGluT1 mRNA. None of the GABAergic interneuron markers was detected in these neurons except the NPY and CCK mRNAs. Thus the electrophysiological and molecular properties of these spiny neurons are consistent with their identification as putative glutamatergic neurons.

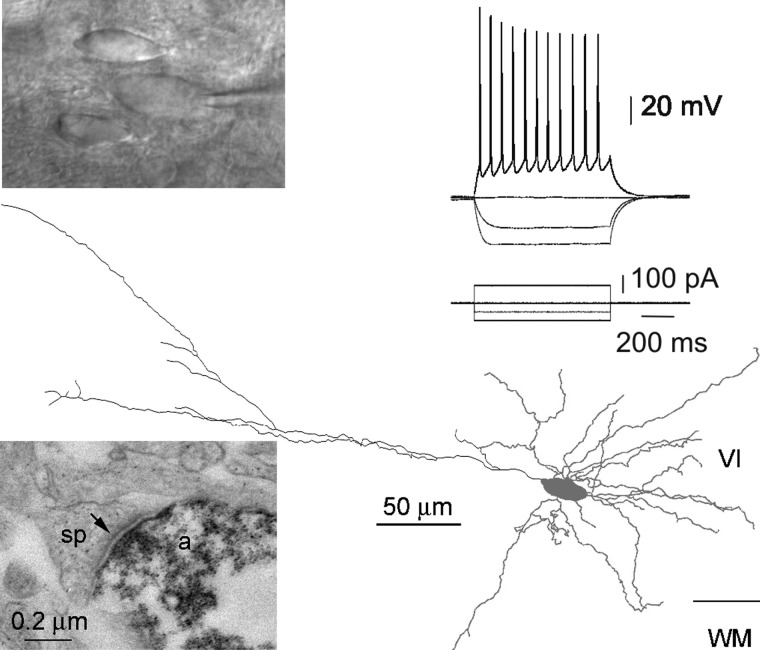

FIG. 1.

Morphological, electrophysiological, and molecular analysis of layer VI vesicular glutamate transporter positive/glutamic acid decarboxylase negative (VGluT+/GAD−) nonpyramidal neurons. A, top: confocal reconstruction of a nonpyramidal neuron analyzed by patch-clamp, single-cell reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (scPCR), and biocytin labeling. This neuron, located in deeper layer VI at the border of the white matter (pial surface is upward), extended a main dendrite tangential to the white matter, short descending dendrites inside the white matter, and exhibited dendritic spines. Bottom left: current-clamp recordings of this cell's responses to depolarizing and hyperpolarizing current steps. The spike discharge showed moderate frequency adaptation and amplitude accommodation. Bottom right: agarose gel analysis of the scPCR products from the same cell, which expressed VGluT1, cholecystokinin (CCK), and neuropeptide Y (NPY) mRNAs. B: the same analysis was conducted on another neuron, exhibiting spiny dendrites originating bilaterally from a horizontally extended fusiform soma (top panels, pial surface is upward). This neuron fired spikes with moderate frequency adaptation and amplitude accommodation and expressed VGluT1 and NPY mRNAs (bottom panels).

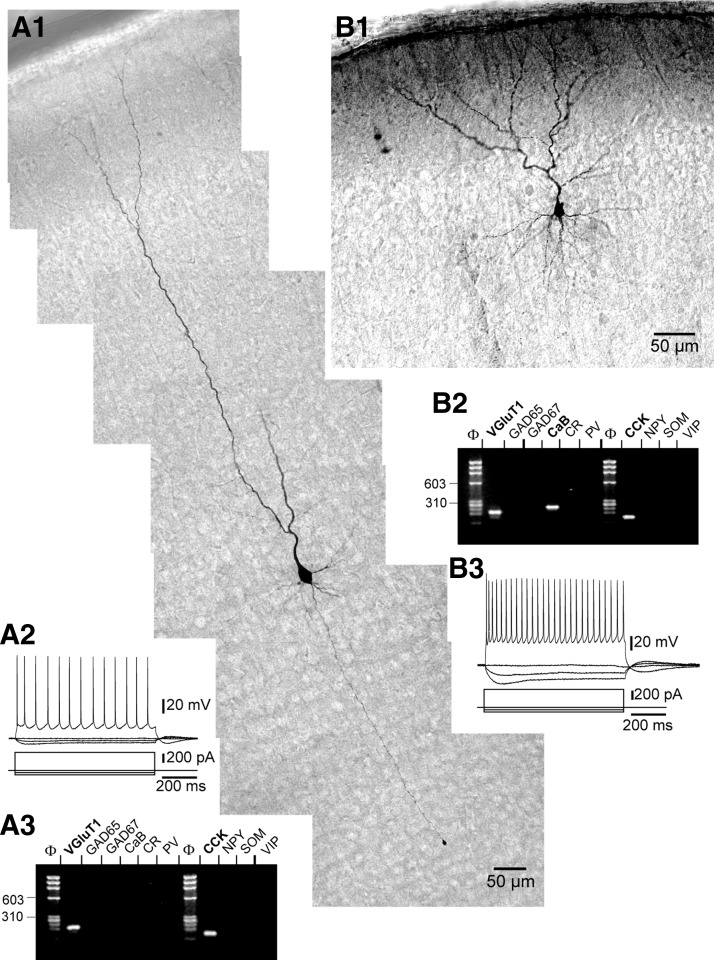

FIG. 5.

Morphological, electrophysiological, and molecular analysis of a spiny stellate neuron. Top panels show the regular pentagonal shape of the soma as visualized by (from left to right) infrared videomicroscopy (in contact with the tip of the recording electrode), camera lucida drawing, and micrograph of biocytin labeling (pial surface is upward). The descending axon (gray, at the center of the figure) sent ascending and horizontal collaterals. This neuron exhibited an RS firing pattern and LTS surmounted by APs following hyperpolarizing current steps. None of the GABAergic interneuron markers was detected in this VGluT+ neuron.

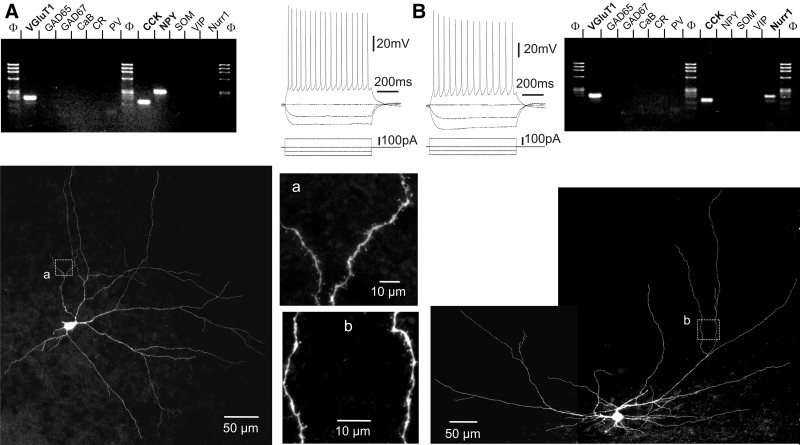

FIG. 6.

Morphological, electrophysiological, and molecular analysis of layers II/III and V pyramidal neurons. A1: photoreconstruction of a layer V pyramidal cell showing a prominent apical dendrite with a ramifying tuft in layer I (pial surface is visible on the top left), thinner basal dendrites, and axon projecting toward the white matter. This neuron exhibited an RS firing pattern (A2) and expressed VGluT1 and CCK mRNAs (A3). The layer II/III pyramidal neuron shown in B1 exhibited an RS firing pattern (B3) and expressed VGluT1, CaB, and CCK mRNAs.

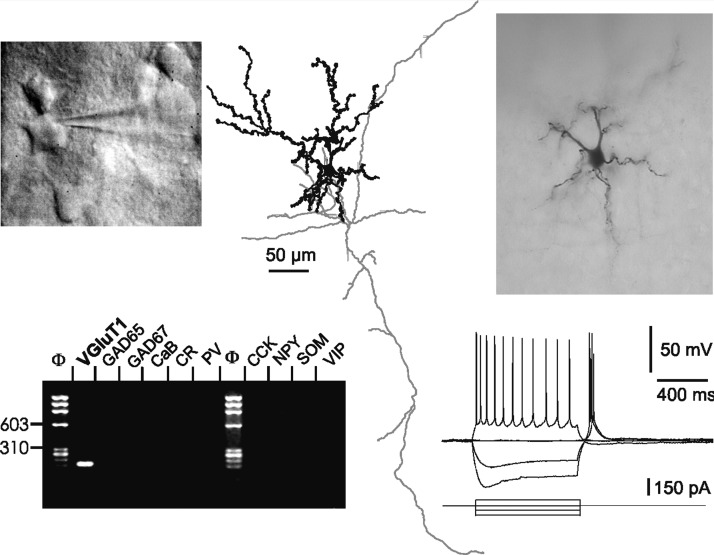

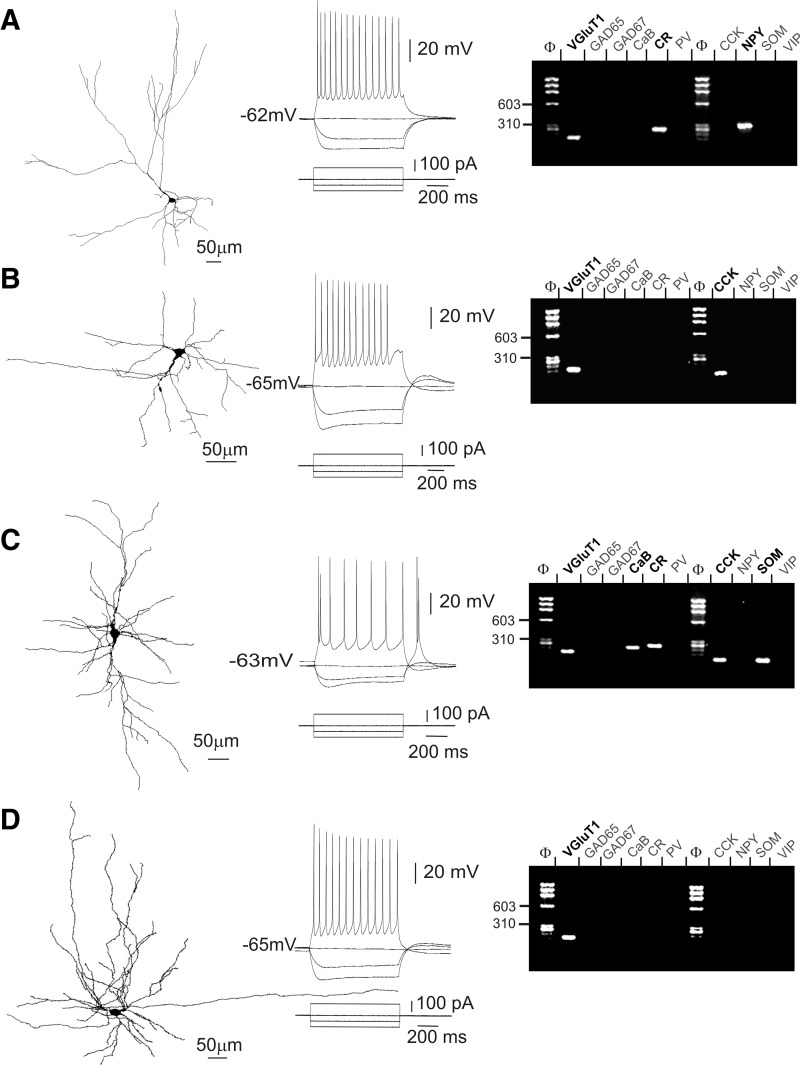

Of the 14 VGluT+/GAD− neurons additionally probed for Nurr1 expression, 5 (36%) expressed the Nurr1 mRNA, consistent with a previous report showing Nurr1 expression in half of layer VI putative glutamatergic neurons (Arimatsu et al. 2003). This suggests that both corticocortical ipsilateral (Nurr1-positive) and commissural (Nurr1-negative) projecting neurons were present in our sample of VGluT+/GAD− layer VI nonpyramidal neurons. Figure 2 displays examples of a Nurr1-positive and a Nurr1-negative neuron. Both cells lacked a prominent apical dendrite and numerous spines were observed on their dendrites. Both neurons exhibited an RS firing pattern with reduction of AP amplitude and frequency along the discharge. Finally, both cells expressed CCK mRNA, and one expressed NPY mRNA, in addition to VGluT1.

FIG. 2.

Layer VI contains Nurr1-positive and Nurr1-negative VGluT+/GAD− nonpyramidal neurons. A: this Nurr1-negative neuron expressed VGluT1, CCK, and NPY mRNAs (top left) and exhibited a regular-spiking (RS) firing pattern (top right). This neuron, located in deeper layer VI (pial surface is upward), extended a main dendrite tangential to the white matter and exhibited dendritic spines (bottom panels). B: this Nurr1-positive neuron additionally expressed the VGluT1 and CCK mRNAs (top right) and exhibited an RS firing pattern (top left). This neuron, located in deep layer VI adjacent to the white matter, exhibited a multipolar morphology with spiny dendrites (bottom panels).

The glutamatergic nature of layer VI spiny nonpyramidal neurons was assessed by examining the morphology of local synaptic contacts made by four such neurons using electron microscopy (see example in Fig. 3). These neurons were located in deep layer VI close to the white matter and exhibited RS firing patterns. The axons made horizontal collaterals in layer VI (n = 2) and/or vertical collaterals running across all cortical layers (n = 3). All synapses (n = 21) examined from the four axons were asymmetrical, as visible in Fig. 3, where a labeled axon terminal of the recorded neuron makes a synapse with an unlabeled dendritic spine exhibiting a postsynaptic density. These results confirm that layer VI spiny nonpyramidal neurons are glutamatergic excitatory neurons.

FIG. 3.

Layer VI nonpyramidal spiny neurons form asymmetrical synapses. Top panels: infrared video microscopy image of a nonpyramidal neuron with a horizontally extended fusiform soma (in contact with the tip of the recording electrode), whose firing pattern exhibited a decrease in spike amplitude and frequency along the discharge. In the bottom part of the figure, reconstruction following biocytin labeling shows the somatodendritic morphology of this neuron (gray) and the course of its axon (black). Examination at the electron microscopic level revealed that this axon made asymmetrical synapses, as shown in the bottom left micrograph where a labeled axon terminal (a) synapses with an unlabeled dendritic spine (sp) exhibiting a postsynaptic density (arrow).

The morphological diversity observed in our sample of VGluT+/GAD− layer VI nonpyramidal neurons is further illustrated in Fig. 4 and was tentatively assigned to morphological subgroups of spiny neurons previously described in layer VI (Prieto and Winer 1999; Tömböl 1984; Zhang and Deschênes 1997). Neurons shown in Figs. 1A, 2A, and 4A fell into the category of “tangential pyramidal” neurons due to the presence of a main dendrite extending obliquely and the general asymmetry of the dendritic tree. This tangential pyramidal morphology was observed in 13 of 34 biocytin-labeled neurons. Figure 4B shows an example of “inverted pyramidal” morphology also reported for layer VI spiny neurons, which we observed in a total of 3 neurons. In addition, 4 neurons exhibiting a vertically extended fusiform soma with two dendritic tufts emerging from its upper and lower poles (Fig. 4C) appeared similar to earlier described “fusiform vertical” spiny neurons. The excitatory nature of layer VI inverted pyramidal and fusiform vertical spiny neurons has been earlier assessed (Mercer et al. 2005). Finally, the neurons shown in Figs. 1B and 3 exhibiting horizontal fusiform somata, but markedly different dendritic trees, and the multipolar neurons shown in Figs. 2B and 4D provide examples of the 14 VGluT+/GAD− nonpyramidal neurons that we could not assign to morphological groups of layer VI spiny neurons earlier defined.

FIG. 4.

Diversity of layer VI VGluT+/GAD− nonpyramidal neurons analyzed by patch-clamp, scPCR, and biocytin labeling. Neurolucida reconstructions on left panels show the nonpyramidal morphology of 4 neurons following biocytin labeling. The pial surface is upward. Current-clamp recordings of responses of these neurons to depolarizing and hyperpolarizing current steps (middle panels) and agarose gel analyses of their scPCR products (right panels). A: this neuron, located at the border of the white matter, exhibited a tangential pyramidal morphology with a main oblique dendrite giving rise to horizontal and vertical secondary branches and short dendrites projecting toward the white matter. This neuron exhibited an RS firing pattern and expressed VGluT1, calretinin (CR), and NPY mRNAs. B: this inverted pyramidal neuron showed an RS firing pattern and expressed the VGluT1 and CCK mRNAs. C: this neuron showing a vertically extended bitufted dendritic tree was classified as fusiform vertical. This RS neuron exhibited a spike doublet at the onset of the action potential (AP) discharge and a low-threshold spike (LTS) following the 100-pA hyperpolarizing current step. In addition to VGluT1, this fusiform vertical neuron expressed calbindin (CaB), CR, CCK, and NPY mRNAs. D: this multipolar VGluT+/GAD− neuron showing an RS firing pattern was not morphologically classified. None of the GABAergic interneuron markers was detected in this neuron. A–D: note that firing patterns displayed in A–C showed an abrupt decrease of AP amplitude and/or frequency at the beginning of the discharge, whereas that displayed in D showed smooth variations of AP amplitude and frequency. Note also the variability of sag amplitude observed in these neurons following the initial peak response to hyperpolarizing current pulses.

Analysis of AP firing patterns showed that, regardless of their morphological features, all VGluT+/GAD− nonpyramidal neurons were RS cells, exhibiting long-duration APs, relatively small AHPs and decreasing AP amplitude and frequency (Figs. 1–4 and Table 2). On injection of hyperpolarizing current pulses, a “sag” indicative of a hyperpolarization-activated cationic current (Ih), followed the initial hyperpolarization peak. The variability of sag amplitudes observed among layer VI VGluT+/GAD− nonpyramidal neurons (see Figs. 1–3) could not be correlated with cellular morphology. In some neurons, application of a hyperpolarizing current pulse was followed by a marked depolarizing rebound, or low-threshold spike (LTS), which triggered APs (see example in Fig. 4C). LTS was observed in 17% (n = 12 of 71) of layer VI VGluT+/GAD− nonpyramidal neurons, including all morphologically identified fusiform vertical neurons (n = 4). However, the presence of the LTS was not specific to this morphological type, in agreement with previous observations (van Brederode and Snyder 1992). These electrophysiological properties are consistent with those reported earlier for layer VI spiny nonpyramidal neurons (van Brederode and Snyder 1992). Mean values of 12 electrophysiological parameters obtained for the 71 VGluT+/GAD− layer VI nonpyramidal neurons are given in Table 2. Comparison between subgroups of morphologically identified layer VI nonpyramidal neurons (tangential pyramidal, n = 13; fusiform vertical, n = 4; and inverted pyramidal, n = 3) revealed significant differences in only 4 of these 12 electrophysiological parameters. Tangential neurons had larger (P ≤ 0.05) first- and second-spike amplitudes (94 ± 8 and 91.4 ± 9.1, respectively) than those of fusiform vertical (82.3 ± 1.7 and 76.3 ± 7.3, respectively) and inverted pyramidal neurons (82.4 ± 4.3 and 75.7 ± 4.3, respectively). Fusiform vertical neurons had greater (P ≤ 0.05) spike amplitude reduction than that of tangential neurons (73.3 ± 6.3 and 2.8 ± 3, respectively). Finally, early adaptation was greater in fusiform vertical neurons (68.7 ± 17.3) than that in inverted pyramidal neurons (48.7 ± 4.3, P ≤ 0.05) and in tangential neurons (46.9 ± 6.8, P ≤ 0.01).

TABLE 2.

Electrophysiological properties of neocortical glutamatergic neurons

| Property | Nonpyramidal VGluT1+ Layer VI (L6, n = 71) | Spiny Stellate Layer IV (St, n = 10) | Pyramidal Layer V (L5, n = 33) | Pyramidal Layers II/III (L2/3, n = 28) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Input resistance, MΩ | 385.30 ± 122.3 | 451.2 ± 158.4 | 159.7 ± 72.5 | 316.6 ± 77.6 |

| St –L6 > L2/3 ≫ L5 | ||||

| Sag, membrane resistance decrease, % | 10.10 ± 6.3 | 16.6 ± 7.0 | 25.7 ± 5.5 | 16.4 ± 6.3 |

| L5 ≫ St –L2/3; L5 ≫ L6; St > L6 | ||||

| First spike amplitude, mV | 91.20 ± 8.6 | 85.9 ± 17.1 | 96.5 ± 4.9 | 84.7 ± 8.2 |

| L5 ≫ L6 –St; L6 ≫ L2/3; St –L2/3 | ||||

| Second spike amplitude, mV | 87.60 ± 10.3 | 77.2 ± 17.3 | 93.9 ± 5.1 | 81.8 ± 9.1 |

| L5 ≫ L6 ≫ L2/3 –St | ||||

| Amplitude reduction, % | 4.07 ± 4.3 | 9.8 ± 5.6 | 2.6 ± 1.9 | 3.5 ± 4.2 |

| St ≫ L6 –L2/3 –L5 | ||||

| First spike duration, ms | 1.90 ± 0.3 | 1.4 ± 0.4 | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 1.3 ± 0.3 |

| L6 ≫ L2/3 –L5 –St | ||||

| Second spike duration, ms | 2.20 ± 0.5 | 1.9 ± 0.6 | 1.7 ± 0.4 | 1.6 ± 0.4 |

| L6 ≫ L2/3 –L5; L6 –St; St > L2/3 –L5 | ||||

| Duration increase, % | 15.30 ± 11.5 | 36.4 ± 15.5 | 13.8 ± 10.6 | 23.4 ± 13.8 |

| St > L2/3 ≫ L6 –L5 | ||||

| First AHP, mV | −13.20 ± 4.1 | −6.2 ± 5.9 | −9.0 ± 3.5 | −9.6 ± 2.9 |

| L6 ≫ L2/3 –L5 > St | ||||

| Second AHP, mV | −15.20 ± 3.3 | −11.7 ± 4.8 | −13.0 ± 2.0 | −13.4 ± 2.0 |

| L6 ≫ L2/3 –L5 –St | ||||

| Early adaptation, % | 48.70 ± 12.6 | 65.8 ± 18.3 | 59.5 ± 9.4 | 57.6 ± 10.0 |

| L2/3 –L5 ≫ L6; L2/3 –L5 –St; St > L6 | ||||

| Late adaptation, % | 17.50 ± 9.4 | 24.4 ± 9.9 | 11.5 ± 8.3 | 20.1 ± 10.3 |

| St –L2/3 –L6 ≫ L5 | ||||

Values are means ± SD; n is the number of cells; > significantly greater with P ≤ 0.005; ≫ significantly greater with P ≤ 0.001; –not significantly different. Statistically significant differences were determined using the Mann–Whitney U test. Electrophysiological parameters were measured as described in methods.

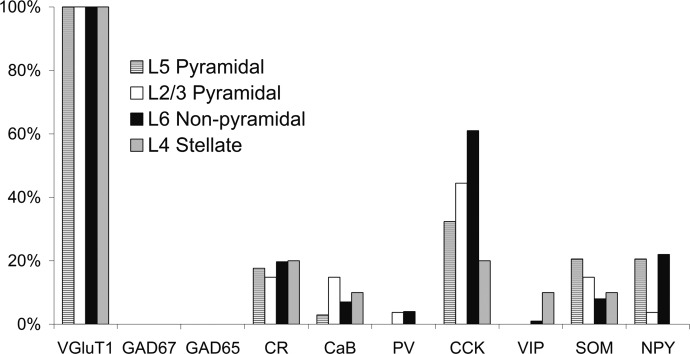

Molecular analysis of VGluT+/GAD− nonpyramidal neurons revealed variable expression patterns of GABAergic interneuron marker mRNAs, with some cells coexpressing up to four markers (see example in Fig. 4C), whereas none of the markers was detected in other neurons (see example in Fig. 4D). In our sample of 71 VGluT+/GAD− layer VI nonpyramidal neurons, the mean occurrence of interneuron marker expression detected was 1.3 ± 1 per cell, with CCK showing the highest occurrence (61%), followed by NPY (23%), CR (20%), and SOM (8%). CaB, PV, and VIP were detected in only five cells, three cells, and one cell, respectively. These results are summarized in Fig. 7. The occasional occurrence of CaB and PV in putative glutamatergic nonpyramidal neurons from layer VI was previously described (van der Gucht et al. 2003).

FIG. 7.

Expression of molecular markers in 4 subgroups of neocortical glutamatergic neurons. All subgroups of glutamatergic neurons were VGluT+/GAD− and exhibited a low occurrence of GABAergic interneuron markers, among which CCK was the most frequently detected.

Thus our combined morphological, electrophysiological, and molecular data support the existence of a large population of glutamatergic nonpyramidal neurons in layer VI exhibiting extensive morphological diversity.

Glutamatergic neurons from other layers

To compare layer VI glutamatergic nonpyramidal neurons with well-established subgroups of neocortical glutamatergic neurons, we next collected spiny stellate neurons and pyramidal cells.

Spiny stellate nonpyramidal neurons from layer IV (n = 10), identified under infrared videomicroscopy from the regular polygonal shape of their soma (Fig. 5), were electrophysiologically characterized and analyzed by scPCR. Morphological examination of 8 of these neurons following biocytin staining confirmed their identification as spiny stellate cells, with multiple primary dendrites arising from the cell body, the presence of numerous dendritic spines, and the absence of a prominent apical dendrite (Fig. 5). Consistent with earlier reports (Connors and Gutnick 1990; Schubert et al. 2003; Staiger et al. 2004), spiny stellate neurons exhibited RS firing patterns with long-duration APs, small AHPs and adaptation of AP amplitude and frequency along the discharge (Fig. 5 and Table 2). In addition, an LTS was frequently observed in our sample of stellate neurons (n = 8 of 10; see Fig. 5). Molecular analysis showed that all spiny stellate neurons were VGluT+/GAD− (Figs. 5 and 7), consistent with their established glutamatergic phenotype (Feldmeyer et al. 1999; Lübke et al. 2000; Schubert et al. 2003; Staiger et al. 2004). The mean occurrence of GABAergic interneuron marker detected per spiny stellate cell was low (0.7 ± 0.7), with four cells expressing none of these markers and one cell coexpressing a maximum of two markers. CCK and CR were detected twice, whereas VIP, CaB, and SOM were detected only once in our sample of 10 spiny stellate neurons (Fig. 7).

Pyramidal neurons from layer II/III (n = 28) and layer V (n = 33), identified under infrared videomicroscopy by their pyramidal-shaped soma and prominent apical dendrite, were electrophysiologically characterized and analyzed by scPCR. On morphological examination of 8 layer II/III and 12 layer V pyramidal neurons, all cells demonstrated a prominent apical dendrite ramifying in layer I and basal lateral dendrites (see examples in Fig. 6). All pyramidal neurons exhibited RS firing patterns with long-duration APs, small AHPs, and adaptation of AP amplitude and frequency (Fig. 6 and Table 2). None of the pyramidal neurons collected from either layer II/III or layer V exhibited an LTS. Pyramidal neurons were VGluT+/GAD− (Figs. 6 and 7) and the mean occurrence of GABAergic interneuron marker detected per cell was low in both layer II/III (1.0 ± 0.9) and layer V (0.9 ± 0.9) pyramidal neurons. We found that in addition to CCK, detected in 44% of layer II/III and 32% of layer V cells, CR, CaB, NPY, and SOM were detected in some pyramidal neurons (Figs. 6 and 7), in good agreement with previous reports (Burgunder and Young 3rd 1990; Cauli et al. 2000; Celio 1990; Gallopin et al. 2006; Hill et al. 2007; Kubota et al. 1994; Morino et al. 1994; Ong et al. 1994; Schiffmann and Vanderhaeghen 1991).

Comparison between subgroups of neocortical glutamatergic neurons

All neurons from each of the four glutamatergic subgroups (i.e., layer II/III pyramidal, layer IV stellate, layer V pyramidal, and layer VI spiny nonpyramidal neurons) were VGluT+/GAD− and showed a low mean occurrence of GABAergic interneuron marker per cell. Although layer VI nonpyramidal neurons expressed slightly more GABAergic interneuron markers per cell (1.2 ± 1) than stellate (0.7 ± 0.7), layer II/III (1.0 ± 0.9), and layer V (0.9 ± 0.9) pyramidal neurons, these differences were not statistically significant. The marker showing the highest occurrence in all subgroups was CCK (Fig. 7). The occurrence of CCK was significantly higher in layer VI nonpyramidal neurons (61%) than in stellate (20%, P ≤ 0.05) and layer V (32%, P ≤ 0.01) pyramidal neurons. The only other significant molecular difference between the subgroups was the more frequent occurrence of NPY in layer VI nonpyramidal neurons (23%) compared with layer II/III pyramidal neurons (3.7%, P ≤ 0.05). Thus the present subgroups of glutamatergic neurons exhibited only minor differences in GABAergic interneuron marker expression profiles.

Although all glutamatergic neurons collected in the present study exhibited RS firing patterns, neuronal subgroups exhibited significantly different mean electrophysiological properties (Table 2). Layer VI nonpyramidal neurons were characterized by a smaller sag, longer-duration APs, larger AHPs, and smaller early adaptation compared with the same parameters of all other subgroups. The long-duration APs and small sag of these neurons have been noted in a previous study of layer VI spiny neurons (van Brederode and Snyder 1992). Layer V pyramidal neurons exhibited a smaller input resistance, larger sag, larger AP amplitudes, and smaller late adaptation compared with identical parameters of all other subgroups. The mean AP amplitude reduction and duration increase were larger for stellate neurons than that for all other subgroups. Finally, mean values obtained for layer II/III pyramidal neurons generally corresponded to a midrange value in the data spread across the other three groups.

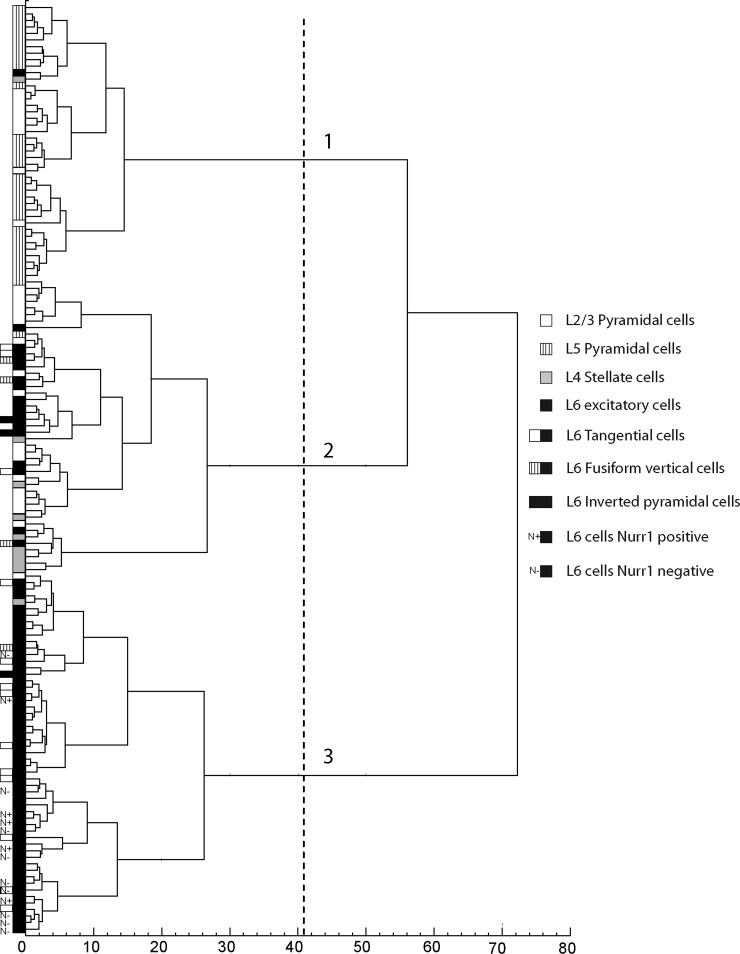

In spite of their distinctive mean properties, each neuron subgroup showed a large interindividual variability for all electrophysiological parameters considered. Because these subgroups were defined a priori based on morphological and/or layer specificity, we investigated whether an unsupervised cluster analysis (see methods) combining all electrophysiological parameters would segregate subgroups of glutamatergic neurons. Molecular parameters that demonstrated a very low occurrence and/or showed only minor differences between neuron subgroups were excluded from the analysis. The unsupervised cluster analysis segregated neurons into three clusters (Fig. 8), suggested by the Thorndike threshold (dotted line). Almost all layer V pyramidal neurons from our sample were assigned to cluster 1 (94%, n = 31 of 33). These layer V pyramidal neurons comprised 72% of cluster 1, which additionally included 9 layer II/III pyramidal, 1 stellate, and 1 layer VI neuron. Cluster 2 in contrast was heterogeneous, comprising not only the majority of layer II/III pyramidal (64%, n = 18 out 28) and stellate neurons (n = 8 of 10), but also part of our sample of layer VI neurons (24%, n = 17 of 71) and 2 layer V pyramidal cells. These findings suggest that subpopulations of stellate, layer II/III pyramidal, and layer VI nonpyramidal glutamatergic neurons share similar electrophysiological properties. Finally, cluster 3 was composed almost exclusively of layer VI excitatory cells (96%) and contained the majority of layer VI neurons in our sample (75%, n = 53 of 71). Thus this layer VI neuronal subpopulation exhibited a distinctive electrophysiological signature. Accordingly, layer VI neurons grouped in cluster 2 differed significantly from those in cluster 3 for most electrophysiological parameters (Table 3). The firing patterns of cluster 2 and of cluster 3 layer VI neurons resembled those of previously reported phasic–tonic and tonic cells, respectively (van Brederode and Snyder 1992). Phasic–tonic cells showed an abrupt decrease of AP amplitude and/or frequency at the beginning of the discharge, often associated with a spike doublet (see Fig. 4, A–C), whereas Figs. 1, 2, and 4D display examples of tonic cells showing little or smooth variations of AP and AHP amplitudes and of AP frequency. The distribution of layer VI neurons in two different clusters did not correlate with their somatodendritic morphologies (as noted previously by van Brederode and Snyder 1992) or projection specificity. Indeed, both clusters contained tangential, inverted pyramidal, and fusiform vertical layer VI glutamatergic neurons and, in cluster 3, corticocortical Nurr1-positive ipsilateral neurons were not segregated from Nurr1-negative commissural neurons.

FIG. 8.

Cluster analysis of neocortical glutamatergic neurons based on electrophysiological properties. The x-axis represents the individual cells and the y-axis the average within-cluster linkage distance. This analysis, applied to layer II/III pyramidal (n = 28), layer V pyramidal (n = 33), layer IV spiny stellate (n = 10), and layer VI nonpyramidal (n = 71) cells aggregated neurons into 3 clusters. Dotted line indicates the limits between clusters as suggested by the Thorndike procedure.

TABLE 3.

Electrophysiological properties of unsupervised neuron clusters

| Property | Cluster 2 (C2, n = 45) | Cluster 3 (C3, n = 55) | Cluster 2 L6 (C2 L6, n = 173) | Cluster 3 L6 (C3 L6, n = 53) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Input resistance, MΩ | 390.7 ± 159.5 | 375.0 ± 109.4 | 429.9 ± 142.8 | 374.6 ± 111.3 |

| C2 –C3 | C2 L6 –C3 L6 | |||

| Sag, membrane resistance decrease, % | 13.8 ± 5.6 | 9.6 ± 6.5 | 11.8 ± 4.7 | 9.4 ± 6.5 |

| C2 ≫ C3 | C2 L6 > C3 L6 | |||

| First spike amplitude, mV | 82.9 ± 7.0 | 93.6 ± 6.8 | 82.8 ± 8.8 | 93.8 ± 6.8 |

| C3 ≫ C2 | C3 L6 ≫ C2 L6 | |||

| Second spike amplitude, mV | 76.9 ± 7.6 | 91.1 ± 7.2 | 75.6 ± 9.5 | 91.4 ± 7.2 |

| C3 ≫ C2 | C3 L6 ≫ C2 L6 | |||

| Amplitude reduction, % | 7.1 ± 6.0 | 2.6 ± 2.3 | 8.7 ± 5.8 | 2.6 ± 2.2 |

| C2 ≫ C3 | C2 L6 ≫ C3 L6 | |||

| First spike duration, ms | 1.5 ± 0.3 | 2.0 ± 0.4 | 1.7 ± 0.2 | 2.0 ± 0.4 |

| C3 ≫ C2 | C3 L6 ≫ C2 L6 | |||

| Second spike duration, ms | 1.9 ± 0.5 | 2.3 ± 0.5 | 2.2 ± 0.4 | 2.3 ± 0.5 |

| C3 ≫ C2 | C2 L6 –C3 L6 | |||

| Duration increase, % | 27.9 ± 15.9 | 12.4 ± 7.7 | 24.3 ± 16.5 | 12.4 ± 7.7 |

| C2 ≫ C3 | C2 L6 ≫ C3 L6 | |||

| First AHP, mV | −8.4 ± 3.7 | −14.5 ± 3.3 | −9.4 ± 3.8 | −14.6 ± 3.3 |

| C3 ≫ C2 | C3 L6 ≫ C2 L6 | |||

| Second AHP, mV | −13.6 ± 3.2 | −15.1 ± 3.3 | −15.5 ± 3.3 | −15.1 ± 3.4 |

| C3 > C2 | C2 L6 –C3 L6 | |||

| Early adaptation, % | 62.1 ± 13.0 | 43.9 ± 7.0 | 60.9 ± 14.7 | 44.0 ± 6.9 |

| C2 ≫ C3 | C2 L6 ≫ C3 L6 | |||

| Late adaptation, % | 17.5 ± 12.8 | 19.4 ± 7.6 | 11.5 ± 11.9 | 19.6 ± 7.6 |

| C2 –C3 | C3 L6 > C2 L6 | |||

Values are means ± SD; n is the number of cells; > significantly greater with P ≤ 0.005; ≫ significantly greater with P ≤ 0.001; –not significantly different. Statistically significant differences were determined using the Mann–Whitney U test. Electrophysiological parameters were measured as described in methods. Cluster 2 L6 and cluster 3 L6 correspond to layer VI neurons from clusters 2 and 3, respectively.

DISCUSSION

We observed a large, morphologically diverse population of glutamatergic nonpyramidal neurons in neocortical layer VI. A comparison of these neurons with spiny stellate and pyramidal glutamatergic neurons from other layers showed a similarly low occurrence of GABAergic interneuron markers, but differences in electrophysiological properties. Unsupervised clustering of neocortical glutamatergic neurons based on electrophysiological properties disclosed three groups of cells: one corresponded to layer V pyramidal neurons, another consisted of a subpopulation of layer VI neurons, whereas the third cluster was heterogeneous and comprised spiny stellate and layer II/III pyramidal and layer VI neurons. The distribution of layer VI neurons in two different clusters did not correlate with their somatodendritic morphologies or projection specificity.

Layer VI glutamatergic nonpyramidal neurons

The present results show that a large proportion of layer VI nonpyramidal neurons are glutamatergic, in contrast with the situation generally found in other layers. The presence of VGluT1 and the absence of GAD indicate that these neurons are excitatory and use glutamate as their main neurotransmitter. Indeed, examination at the electron microscopic level showed that these neurons formed asymmetrical excitatory synapses. Although a subset of GABAergic interneurons possesses dendritic spines (Kawaguchi and Kubota 1993; McCormick et al. 1985; Thomson et al. 1996), a high spine density is generally considered to be a good criterion to identify excitatory neurons (Connors and Gutnick 1990). The presence of numerous dendritic spines on all VGluT+/GAD− neurons examined in the present study shows that this criterion applies to morphological subgroups of spiny nonpyramidal neurons previously defined in layer VI (Prieto and Winer 1999; Tömböl 1984; Zhang and Deschênes 1997). All VGluT+/GAD− layer VI nonpyramidal neurons exhibited RS firing patterns. In the neocortex, RS firing patterns are observed not only for glutamatergic neurons, but also for several GABAergic interneuron subtypes (Cauli et al. 1997, 2000; Kawaguchi 1995). In contrast with pyramidal neurons that, based solely on their electrophysiological properties, are completely segregated from RS GABAergic interneurons following cluster analysis (Cauli et al. 2000), layer VI glutamatergic nonpyramidal neurons exhibited both pyramidal-like and interneuron-like AP firing features. Although the long AP duration of layer VI neurons was typical of glutamatergic neurons in the neocortex, their AHP amplitude and the adaptation of their AP amplitude and frequency were clearly in the range of those we previously reported for RS GABAergic interneurons under similar experimental conditions (Cauli et al. 1997, 2000; Gallopin et al. 2006). The present results thus expand the range of electrophysiological properties associated with glutamatergic neurons, which appear to overlap substantially those of GABAergic interneurons.

Anatomical and electrophysiological diversity of layer VI glutamatergic neurons

The diversity of somatodendritic morphologies of layer VI nonpyramidal glutamatergic neurons extends beyond the three morphological types we identified in our sample of biocytin-labeled nonpyramidal cells, which also comprised neurons we were unable to classify (n = 14 of 34, 41%). Layer VI further contains stellate and star pyramidal spiny neurons (Kaneko and Mizuno 1996; Tömböl 1984) whose glutamatergic nature is well established (Feldmeyer et al. 1999; Lübke et al. 2000; Schubert et al. 2003; Staiger et al. 2004), as well as classical pyramidal cells. However, in contrast with these latter morphological types that are also numerous in other cortical layers, the present glutamatergic nonpyramidal neurons seem to be preferentially localized in layer VI. This is reportedly the case for tangential pyramidal neurons (Tömböl 1984), whereas somatodendritic morphologies of inverted pyramidal and vertical fusiform cells generally correspond to GABAergic interneurons in other cortical layers. For instance, interneurons expressing nitric oxide synthase, which coexpress GAD in all cortical layers, often exhibit inverted pyramidal morphology (Gabbott and Bacon 1995; Gabbott et al. 1997). Vertical fusiform neurons (i.e., showing a vertical bipolar/bitufted dendritic arborization) have been recognized as inhibitory interneurons based on their symmetrical synapses (Somogyi and Cowey 1981). It is noteworthy, however, that the existence of bipolar/bitufted neurons forming asymmetrical synapses (Peters and Harriman 1988; Peters and Kimerer 1981) and of inverted pyramidal cells with high spine density (Miller 1988) has also been reported in layers II–V. Nonetheless, although glutamatergic nonpyramidal neurons appear to be present in all cortical layers, the present results suggest that layer VI contains a higher proportion of morphologically diverse glutamatergic nonpyramidal neurons than that of other layers.

Layer VI nonpyramidal spiny neurons form corticocortical projections but, in contrast with pyramidal neurons of the same layer, send little or no projection to the thalamus (Prieto and Winer 1999). Among the morphological types of layer VI spiny nonpyramidal neurons presently studied, all send both ipsilateral and commissural corticocortical projections (Prieto and Winer 1999). Nonetheless, ipsilateral and commissural projection neurons form distinct populations differentiated by the selective expression of Nurr1 in ipsilateral neurons (Arimatsu et al. 2003). The present observation that both Nurr1-positive and Nurr1-negative cells were collected in this study suggests that both populations of ipsilateral and commissural projection neurons are represented in our sample of VGluT+/GAD− layer VI nonpyramidal neurons.

Unsupervised analysis of electrophysiological diversity segregated layer VI glutamatergic nonpyramidal neurons into two clusters, which corresponded to earlier described phasic–tonic and tonic layer VI spiny (presumably glutamatergic) neurons (van Brederode and Snyder 1992). Consistent with this previous report, we found that electrophysiological classes did not correlate with somatodendritic morphological subgroups. Similarly, the distribution of layer VI neurons in two different clusters did not correlate with their ipsilateral or commissural projection specificity.

Subgroups of glutamatergic neocortical neurons

All subgroups of neocortical glutamatergic neurons were VGluT+/GAD−, which appears to be a reliable criterion for the identification of glutamatergic excitatory neurons in the neocortex. Comparison of layer VI nonpyramidal neurons with other subgroups indicates that, independent of their broad morphological diversity, neocortical glutamatergic neurons share a number of common properties.

At the molecular level, both pyramidal and nonpyramidal glutamatergic neurons showed a low occurrence of GABAergic interneuron markers. This demonstrates that these markers are preferentially associated with the GABAergic phenotype but not with the nonpyramidal morphology. Occasional expression of CCK, CaB, CR, NPY, and SOM, previously reported in pyramidal neurons (Burgunder and Young 3rd 1990; Celio 1990; Gallopin et al. 2006; Hill et al. 2007; Kubota et al. 1994; Morino et al. 1994; Ong et al. 1994; Schiffmann and Vanderhaeghen 1991), was also observed in our sample of nonpyramidal glutamatergic neurons. Among these markers, CCK showed the highest abundance, especially in layer VI where it was detected in 61% of the neurons, and a widespread expression in all subgroups of neocortical glutamatergic neurons. In contrast, NPY was found almost exclusively in layers V and VI glutamatergic neurons, indicating that its expression in upper neocortical layers (Hendry 1984; Kuljis and Rakic 1989a,b) is restricted to GABAergic interneurons.

At the electrophysiological level, all glutamatergic neurons collected exhibited RS firing patterns. Some glutamatergic neurons fire bursts of APs and form the class of intrinsically bursting neurons (Connors and Gutnick 1990) comprising subpopulations of pyramidal, stellate, and star pyramidal glutamatergic neurons (Connors and Gutnick 1990; Schubert et al. 2003; Staiger et al. 2004). Since this phenotype is uncovered in otherwise RS neurons following deep anesthesia (Christophe et al. 2005), it is likely that our sample of glutamatergic neurons contained a proportion of intrinsically bursting neurons, whose burst firing was hidden in our experimental conditions. Nonetheless, the four glutamatergic neuron subgroups of the present study exhibited differences in the electrophysiological properties considered and neurons within each subgroup showed substantial interindividual variability.

Analysis of the electrophysiological diversity of our entire sample of glutamatergic cells by unsupervised clustering aggregated neurons into three clusters showing morphological heterogeneity. Indeed, cluster 1 comprised one third of our layer II/III pyramidal cells sample in addition to layer V pyramidal neurons, cluster 2 contained layer II/III pyramidal neurons together with stellate and layer VI neurons, and cluster 3 contained morphologically diverse layer VI neurons. This indicates that electrophysiological similarities between neocortical glutamatergic neurons extend beyond the borders of subgroups defined by somatodendritic morphologies and layer position. A similar conclusion was drawn by Staiger et al. (2004) from comparison of layer IV star pyramidal, stellate, and pyramidal neurons. A well-documented correlate to electrophysiological heterogeneity within subgroups of glutamatergic neurons is the projection target (for layer V pyramidal cells, see reviews by Hattox and Nelson 2007; Molnar and Cheung 2006; and for layer VI neurons, see Brumberg et al. 2003; Kumar and Ohana 2008). Although layer II/III pyramidal and layer VI nonpyramidal neurons are major sources of both ipsilateral and commissural corticocortical projections (Code and Winer 1985; Innocenti 1986; Prieto and Winer 1999; Winguth and Winer 1986), spiny stellate neurons predominantly project locally (Lund 1984) and layer V pyramidal neurons form the main contingent of corticofugal projections (Molnar and Cheung 2006). Here, the grouping of layer II/III and layer V pyramidal neurons (cluster 1); of layer II/III pyramidal, stellate, and layer VI neurons (cluster 2); and of ipsilateral and contralateral layer VI neurons (cluster 3) did not correlate with projection target specificity. Thus our results suggest that electrophysiological similarities between neocortical glutamatergic neurons extend beyond anatomically defined subgroups.

GRANTS

S. Andjelic was the recipient of a Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale fellowship. G. Tamás was supported by European Young Investigator Awards; National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Grant NS-35915; Hungarian Academy of Sciences National Office for Research and Technology Grants KFKT-1-2006-009 and RET008/2004; Hungarian Scientific Research Fund Grants T049535 and TS049868; and Howard Hughes Medical Institute Grant 55005625. B. Cauli was supported by Human Frontier Science Program Young Investigator Award RGY0070.

Acknowledgments

We thank H. Geoffroy, L. Tricoire, and the IFR83 Cell Imaging Facility for valuable assistance and E. Toth for technical assistance.

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. The article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

- Arimatsu et al. 2003.Arimatsu Y, Ishida M, Kaneko T, Ichinose S, Omori A. Organization and development of corticocortical associative neurons expressing the orphan nuclear receptor Nurr1. J Comp Neurol 466: 180–196, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bochet et al. 1994.Bochet P, Audinat E, Lambolez B, Crépel F, Rossier J, Iino M, Tsuzuki K, Ozawa S. Subunit composition at the single-cell level explains functional properties of a glutamate-gated channel. Neuron 12: 383–388, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brumberg et al. 2003.Brumberg JC, Hamzei-Sichani F, Yuste R. Morphological and physiological characterization of layer VI corticofugal neurons of mouse primary visual cortex. J Neurophysiol 89: 2854–2867, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgunder and Young 1990.Burgunder JM, Young WS 3rd. Cortical neurons expressing the cholecystokinin gene in the rat: distribution in the adult brain, ontogeny, and some of their projections. J Comp Neurol 300: 26–46, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cauli et al. 1997.Cauli B, Audinat E, Lambolez B, Angulo MC, Ropert N, Tsuzuki K, Hestrin S, Rossier J. Molecular and physiological diversity of cortical nonpyramidal cells. J Neurosci 17: 3894–3906, 1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cauli et al. 2000.Cauli B, Porter JT, Tsuzuki K, Lambolez B, Rossier J, Quenet B, Audinat E. Classification of fusiform neocortical interneurons based on unsupervised clustering. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 6144–6149, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celio 1990.Celio MR Calbindin D-28k and parvalbumin in the rat nervous system. Neuroscience 35: 375–475, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christophe et al. 2005.Christophe E, Doerflinger N, Lavery DJ, Molnár Z, Charpak S, Audinat E. Two populations of layer v pyramidal cells of the mouse neocortex: development and sensitivity to anesthetics. J Neurophysiol 94: 3357–3367, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Code and Winer 1985.Code RA, Winer JA. Commissural neurons in layer III of cat primary auditory cortex (AI): pyramidal and non-pyramidal cell input. J Comp Neurol 242: 485–510, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connors and Gutnick 1990.Connors BW, Gutnick MJ. Intrinsic firing patterns of diverse neocortical neurons. Trends Neurosci 13: 99–104, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairén et al. 1984.Fairén A, DeFelipe J, Regidor J. Nonpyramidal neurons. In. Cerebral Cortex: Cellular Components of the Cerebral Cortex, edited by Peters A, Jones EG. New York: Plenum, 1984, vol. 1, p. 2019–253.

- Feldmeyer et al. 1999.Feldmeyer D, Egger V, Lubke J, Sakmann B. Reliable synaptic connections between pairs of excitatory layer 4 neurones within a single “barrel” of developing rat somatosensory cortex. J Physiol 521: 169–190, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher and Yates 1946.Fisher RA, Yates F. Statistical Tables for Biological, Agricultural, and Medical Research (6th ed.). Edinburgh, UK: Oliver & Boyd, 1946.

- Fremeau et al. 2001.Fremeau RT, Troyer MD, Pahner I, Nygaard GO, Tran CH, Reimer RJ, Bellocchio EE, Fortin D, Storm-Mathisen J, Edwards RH. The expression of vesicular glutamate transporters defines two classes of excitatory synapse. Neuron 31: 247–260, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujiyama et al. 2001.Fujiyama F, Furuta T, Kaneko T. Immunocytochemical localization of candidates for vesicular glutamate transporters in the rat cerebral cortex. J Comp Neurol 435: 379–387, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabbott and Bacon 1995.Gabbott PL, Bacon SJ. Co-localisation of NADPH diaphorase activity and GABA immunoreactivity in local circuit neurones in the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) of the rat. Brain Res 699: 321–328, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabbott et al. 1997.Gabbott PL, Dickie BG, Vaid RR, Headlam AJ, Bacon SJ. Local-circuit neurones in the medial prefrontal cortex (areas 25, 32 and 24b) in the rat: morphology and quantitative distribution. J Comp Neurol 377: 465–499, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallopin et al. 2006.Gallopin T, Geoffroy H, Rossier J, Lambolez B. Cortical sources of CRF, NKB, and CCK and their effects on pyramidal cells in the neocortex. Cereb Cortex 10: 1440–1452, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hattox and Nelson 2007.Hattox AM, Nelson SB. Layer V neurons in mouse cortex projecting to different targets have distinct physiological properties. J Neurophysiol 98: 3330–3340, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendry et al. 1984.Hendry SH, Jones EG, Emson PC. Morphology, distribution, and synaptic relations of somatostatin- and neuropeptide Y-immunoreactive neurons in rat and monkey neocortex. J Neurosci 4: 2497–2517, 1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzog et al. 2001.Herzog E, Bellenchi GC, Gras C, Bernard V, Ravassard P, Bedet C, Gasnier B, Giros B, El Mestikawy S. The existence of a second vesicular glutamate transporter specifies subpopulations of glutamatergic neurons. J Neurosci 21: RC181, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzog et al. 2004.Herzog E, Gilchrist J, Gras C, Muzerelle A, Ravassard P, Giros B, Gaspar P, El Mestikawy S. Localization of VGLUT3, the vesicular glutamate transporter type 3, in the rat brain. Neuroscience 123: 983–1002, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill et al. 2007.Hill EL, Gallopin T, Férézou I, Cauli B, Rossier J, Schweitzer P, Lambolez B. Functional CB1 receptors are broadly expressed in neocortical GABAergic and glutamatergic neurons. J Neurophysiol 4: 2580–2589, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houser et al. 1983.Houser CR, Hendry SHC, Jones EG, Vaughn JE. Morphological diversity of immunocytochemically identified GABA neurons in the monkey sensory-motor cortex. J Neurocytol 12: 617–638, 1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Innocenti 1986.Innocenti GM General organization of callosal connections in the cerebral cortex. In: Cerebral Cortex: Sensory-Motor Areas and Aspects of Cortical Connectivity, edited by Peters A, Jones EG. New York: Plenum, 1986, vol. 5, p. 291–353.

- Jones 1975.Jones EG Varieties and distribution of non-pyramidal cells in the somatic sensory cortex of the squirrel monkey. J Comp Neurol 160: 205–267, 1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko and Mizuno 1988.Kaneko T, Mizuno N. Immunohistochemical study of glutaminase-containing neurons in the cerebral cortex and thalamus of the rat. J Comp Neurol 267: 590–602, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko and Mizuno 1996.Kaneko T, Mizuno N. Spiny stellate neurones in layer VI of the rat cerebral cortex. Neuroreport 7: 2331–2335, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang et al. 1999.Kang Y, Endo K, Araki T, Kaneko T. Trans-synaptically induced bursts in regular spiking non-pyramidal cells in deep layers of the cat motor cortex. Cereb Cortex 9: 77–89, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karayannis et al. 2007.Karayannis T, Huerta-Ocampo I, Capogna M. GABAergic and pyramidal neurons of deep cortical layers directly receive and differently integrate callosal input. Cereb Cortex 17: 1213–1226, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaguchi 1995.Kawaguchi Y Physiological subgroups of nonpyramidal cells with specific morphological characteristics in layer II/III of rat frontal cortex. J Neurosci 15: 2638–2655, 1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaguchi and Kubota 1993.Kawaguchi Y, Kubota Y. Correlation of physiological subgroupings of nonpyramidal cells with parvalbumin- and calbindin-D28k immunoreactive neurons in layer V of rat frontal cortex. J Neurophysiol 70: 387–396, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubota et al. 1994.Kubota Y, Hattori R, Yui Y. Three distinct subpopulations of GABAergic neurons in rat frontal agranular cortex. Brain Res 649: 159–173, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuljis and Rakic 1989a.Kuljis RO, Rakic P. Distribution of neuropeptide Y-containing perikarya and axons in various neocortical areas in the macaque monkey. J Comp Neurol 280: 383–392, 1989a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuljis and Rakic 1989b.Kuljis RO, Rakic P. Multiple types of neuropeptide Y-containing neurons in primate neocortex. J Comp Neurol 280: 393–409, 1989b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar and Ohana 2008.Kumar P, Ohana O. Inter- and intralaminar subcircuits of excitatory and inhibitory neurons in layer 6a of the rat barrel cortex. J Neurophysiol 100: 1909–1922, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambolez et al. 1992.Lambolez B, Audinat E, Bochet P, Crepel F, Rossier J. AMPA receptor subunits expressed by single Purkinje cells. Neuron 9: 247–258, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lübke et al. 2000.Lübke J, Egger V, Sakmann B, Feldmeyer D. Columnar organization of dendrites and axons of single and synaptically coupled excitatory spiny neurons in layer 4 of the rat barrel cortex. J Neurosci 20: 5300–5311, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund 1984.Lund JS Spiny stellate neurons. In: Cerebral Cortex: Cellular Components of the Cerebral Cortex, edited by Peters A, Jones EG. New York: Plenum, 1984, vol. 1, p. 255–308.

- McCormick et al. 1985.McCormick DA, Connors BW, Lighthall JW, Prince DA. Comparative electrophysiology of pyramidal and sparsely spiny stellate neurons of the neocortex. J Neurophysiol 54: 782–806, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercer et al. 2005.Mercer A, West DC, Morris OT, Kirchhecker S, Kerkhoff JE, Thomson AM. Excitatory connections made by presynaptic cortico-cortical pyramidal cells in layer 6 of the neocortex. Cereb Cortex 15: 1485–1496, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller 1988.Miller MW Maturation of rat visual cortex: IV. The generation, migration, morphogenesis, and connectivity of atypically oriented pyramidal neurons. J Comp Neurol 274: 387–405, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molnar and Cheung 2006.Molnar Z, Cheung AFP. Towards the classification of subpopulations of layer V pyramidal projection neurons. Neurosci Res 55: 105–115, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morino et al. 1994.Morino P, Herrera-Marschitz M, Castel MN, Ungerstedt U, Varro A, Dockray G, Hokfelt T. Cholecystokinin in cortico-striatal neurons in the rat: immunohistochemical studies at the light and electron microscopical level. Eur J Neurosci 6: 681–692, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong et al. 1994.Ong WY, Garey LJ, Sumi Y. Distribution of preprosomatostatin mRNA in the rat parietal and temporal cortex. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 23: 151–156, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters and Harriman 1988.Peters A, Harriman KM. Enigmatic bipolar cell of rat visual cortex. J Comp Neurol 267: 409–432, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters and Jones 1981.Peters A, Jones EG.Classification of cortical neurons. In: Cerebral Cortex: Cellular Components of the Cerebral Cortex, edited by Peters A, Jones EG. New York: Plenum, 1984, vol. 1, p. 107–121.

- Peters and Kimerer 1981.Peters A, Kimerer LM. Bipolar neurons in rat visual cortex: a combined Golgi-electron microscopy study. J Neurocytol 10: 921–946, 1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prieto and Winer 1999.Prieto JJ, Winer JA. Layer VI in cat primary auditory cortex: Golgi study and sublaminar origins of projection neurons. J Comp Neurol 404: 332–358, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiffmann and Vanderhaeghen 1991.Schiffmann SN, Vanderhaeghen JJ. Distribution of cells containing mRNA encoding cholecystokinin in the rat central nervous system. J Comp Neurol 304: 219–233, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schubert et al. 2003.Schubert D, Kötter R, Zilles K, Luhmann HJ, Staiger JF. Cell type-specific circuits of cortical layer IV spiny neurons. J Neurosci 23: 2961–2970, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somogyi and Cowey 1981.Somogyi P, Cowey A. Combined Golgi and electron microscopic study on the synapses formed by double bouquet cells in the visual cortex of the cat and monkey. J Comp Neurol 195: 547–566, 1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staiger et al. 2004.Staiger JF, Flagmeyer I, Schubert D, Zilles K, Kötter R, Luhmann HJ. Functional diversity of layer IV spiny neurons in rat somatosensory cortex: quantitative morphology of electrophysiologically characterized and biocytin labeled cells. Cereb Cortex 14: 690–701, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart et al. 1993.Stuart GJ, Dodt HU, Sakmann B. Patch-clamp recordings from the soma and dendrites of neurons in brain slices using infrared video microscopy. Pflügers Arch 423: 511–518, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabadics et al. 2001.Szabadics J, Lorincz A, Tamás G. Beta and gamma frequency synchronization by dendritic gabaergic synapses and gap junctions in a network of cortical interneurons. J Neurosci 21: 5824–5831, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takamori et al. 2000.Takamori S, Rhee JS, Rosenmund C, Jahn R. Identification of a vesicular glutamate transporter that defines a glutamatergic phenotype in neurons. Nature 407: 189–194, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamás et al. 1997.Tamás G, Buhl EH, Somogyi P. Fast IPSPs elicited via multiple synaptic release sites by different types of GABAergic neurone in the cat visual cortex. J Physiol 500: 715–738, 1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson et al. 1996.Thomson AM, West DC, Hahn J, Deuchars J. Single axon IPSPs elicited in pyramidal cells by three classes of interneurones in slices of rat neocortex. J Physiol 496: 81–102, 1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorndike 1953.Thorndike RL Who belongs in a family? Psychometrika 18: 267–276, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Tömböl 1992.Tömböl T. Layer VI cells. In: Cerebral Cortex: Cellular Components of the Cerebral Cortex, edited by Peters A, Jones EG. New York: Plenum Press, 1984, vol. 1, p. 479–519.

- van Brederode and Snyder 1992.van Brederode JFM, Snyder GL. A comparison of the electrophysiological properties of morphologically identified cells in layer 5B and 6 of the rat neocortex. Neuroscience 50: 315–337, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Gucht et al. 2003.van der Gucht E, Jacobs S, Kaneko T, Vandesande F, Arckens L. Distribution and morphological characterization of phosphate-activated glutaminase-immunoreactive neurons in cat visual cortex. Brain Res 988: 29–42, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward 1963.Ward JH Hierarchical grouping to optimize an objective function. J Am Stat Assoc 58: 236–244, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Winguth and Winer 1986.Winguth SD, Winer JA. Corticocortical connections of cat primary auditory cortex (AI): laminar organization and identification of supragranular neurons projecting to area AII. J Comp Neurol 248: 36–56, 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang and Deschênes 1997.Zhang ZW, Deschênes M. Intracortical axonal projections of lamina VI cells of the primary somatosensory cortex in the rat: a single-cell labeling study. J Neurosci 17: 6365–6379, 1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]