Abstract

Pressure overload is a common pathological insult to the heart and the resulting hypertrophy is an independent risk factor for sudden cardiac death. Gap junction remodeling (GJR) has been described in hypertrophied hearts; however, a detailed understanding of the remodeling process and its effects on impulse propagation is lacking. Moreover, there has been little progress developing therapeutic strategies to diminish GJR. Accordingly, transverse aortic banding (TAC) was performed in mice to determine the effects of progressive pathological hypertrophy on connexin (Cx)43 expression, posttranslational phosphorylation, gap junction assembly, and impulse propagation. Within 2 weeks after TAC, total and phospho-Cx43 abundance was reduced and incorporation of Cx43 into gap junctional plaques was markedly diminished. These molecular changes were associated with progressive slowing of impulse propagation, as determined by optical mapping with voltage-sensitive dyes. Treatment with the aldosterone receptor antagonist spironolactone, which has been shown to diminish sudden arrhythmic death in clinical trials, was examined for its effects on GJR. We found that spironolactone blunted the development of GJR and also potently reversed established GJR, both at the molecular and functional levels, without diminishing the extent of hypertrophy. These data suggest a potential mechanism for some of the salutary electrophysiological and clinical effects of mineralocorticoid antagonists in myopathic hearts.

Keywords: gap junction, spironolactone, arrhythmias, optical mapping, mouse, connexin

Hemodynamic overload is a commonly encountered pathological cardiovascular stimulus, and the associated hypertrophy has long been considered an independent risk factor for cardiac mortality, including sudden cardiac death.1-6 The effects of hypertrophic stimuli on gap junction expression and function have been studied in a number of experimental systems, including cultured neonatal myocytes, animal models, and human pathological specimens (reviewed elsewhere7,8). In neonatal cardiac myocytes, connexin (Cx)43 gap junction protein expression increases in response to acute administration of hypertrophic agents such as angiotensin II and cAMP.9,10 However, in vivo, both in experimental animals and in humans, prolonged hemodynamic overload is more commonly associated with significant downregulation of Cx43 expression, as well as lateralization of gap junctional protein away from the intercalated disks, ie, with gap junction remodeling (GJR).11-14 Interestingly, in a study of volume overload–induced hypertrophy, a transient upregulation of Cx43 was observed within hours after imposition of the hemodynamic load, followed by significant reduction in myocardial Cx43 content.15 Taken together, these in vitro and in vivo data suggest that GJR may be biphasic, although the second phase, characterized by diminished density of junctional channels, may be more clinically relevant.

In the present study, we used the well-characterized transverse aortic constriction (TAC) model to evaluate GJR and impulse propagation during progressive cardiac hypertrophy in intact hearts. Our results suggest that GJR significantly diminishes conduction velocity, although not sufficiently to support inducible arrhythmias. Altered post-translational phosphorylation of Cx43 was observed within days after imposition of TAC, suggesting that aberrant processing of this gap junctional protein is an essential element in the remodeling process. We found that treatment with the mineralocorticoid antagonist spironolactone blunts the development of pathological GJR and also potently reverses established GJR, both at the molecular and functional levels, without diminishing the extent of hypertrophy.

Materials and Methods

Animal Model

All animal procedures were carried out in accordance with Public Health Service Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and approved by the New York University School of Medicine Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. TAC was performed on C57Bl6 male mice (3 to 4 months of age) as previously described.16 Mice received either standard chow diet (AIN-76A, Research Diets, New Brunswick, NJ) or standard chow supplemented with spironolactone (50 mg/kg per day).

Echocardiography

Left ventricular dimensions and function were assessed by echocardiography as previously described using an ATL 5000CV Ultrasound System (Philips Medical, Bothell, Wash).17

Fibrosis Index

Formalin-fixed, paraffin embedded sections were stained with Masson’s trichrome and analyzed with Image-Pro Plus 5.0 software (Media Cybernetics, Bethesda, Md) as previously described.18

Western Blot Analysis

Total protein lysates and Triton X-100 insoluble pellet fractions were prepared from the apical two-thirds of the ventricle as previously described.19 Primary antibodies included rabbit polyclonal 18B, which recognizes all forms of Cx43 and is directed toward an epitope from the carboxyl terminus; mouse monoclonal Cx43NT1, which also recognizes all forms of Cx43 but is directed toward an epitope from the amino terminus; rabbit antipS325/328/330-Cx43 and rabbit antipS365-Cx43 antibodies, which recognize specific phosphorylated forms of Cx43.19-21 Equivalency of protein loading was verified by probing for vinculin for total lysates or by Ponceau staining of the membrane for Triton X-100 pellets. Signals were visualized and quantified using the Odyssey Imaging System (Li-Cor, Lincoln, Neb).

Immunohistochemistry

Staining was performed on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded hearts using either fluorescein isothiocyanate or peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies as previously described.19,22

Heart Isolation and Optical Mapping

High-resolution optical mapping experiments were performed as previously described, using either a charge-coupled device camera (Dalsa, CAD-128, Waterloo, Calif) or, in more recent experiments, a newer generation CMOS video camera (Ultima-L; SciMedia Inc).17,23 Studies were performed in the absence of any pharmacological or mechanical motion–reduction techniques. Epicardial conduction velocity (CV) measurements were obtained from the left ventricular surface, with only those pixels residing between 1 and 3 mm from the stimulation site being included in the analyses.22,24 Because of the improved robustness of the signal, we focused primarily on measurements of CVmin although CVmax values are reported as well. For studies of pharmacological gap junction uncoupling, after baseline parameters were determined, hearts were perfused with 18α-glycyrrhetinic acid (αGA) (7.5 μmol/L) for 15 minutes (Sigma-Aldrich), and CV measurements were repeated.

Programmed Electric Stimulation

Ventricular effective refractory periods (VERPs) of isolated-perfused hearts were calculated with a standard S1S2 protocol at a basic cycle length of 100 ms, with the introduction of progressively premature S2 stimuli at 2-ms intervals. The ERP was defined as the longest coupling interval that failed to capture. Following determination of VERP, arrhythmia susceptibility was assessed by provocative testing using single and double extrastimuli, as previously described.22

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as means±SEM unless otherwise indicated. Probability values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Progressive Hypertrophy With TAC

TAC resulted in an initial phase of cardiac hypertrophy followed by the development of left ventricular dilatation and deterioration in contractile function, as determined by serial echocardiographic studies. The gross appearance of the heart at 2, 4, and 8 weeks after aortic constriction is shown in Figure 1A. Progressive cellular hypertrophy was also observed; by 8 weeks after TAC, there was an increase of 31% in cell length and an increase of 56% in cell width. These data are summarized in Tables 1 and 2.

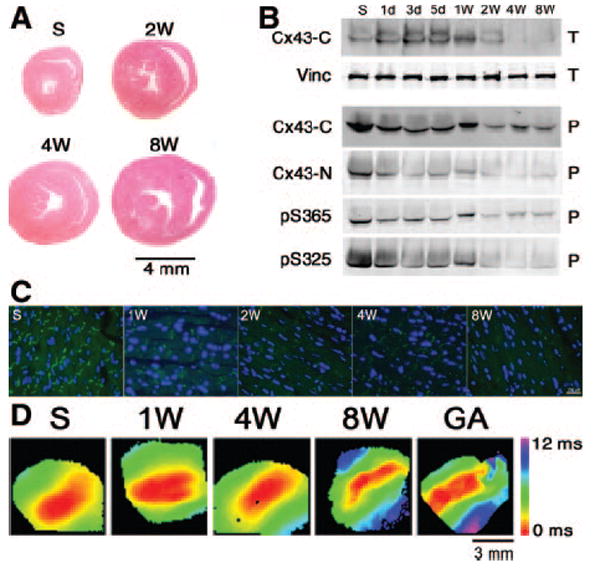

Figure 1.

Molecular and functional GJR in TAC mice. A, Representative cross-sections of hearts showing progressive hypertrophy. B, Western blot analysis demonstrating GJR. Hearts were harvested at the indicated times post-TAC and either total cellular lysates (T) or Triton X-100 insoluble pellet fractions (P) were prepared. Antibodies were directed toward the Cx43 C terminus (Cx43-C); Cx43 N terminus (Cx43-N); vinculin (Vinc); S365-phosphoCx43 (pS365); or S325/328/330-phosphoCx43 (pS325). C, Immunofluorescent staining shows progressive loss of junctional Cx43. Sections were stained with a pan-Cx43 antibody. D, Representative optical maps demonstrate progressive slowing of CV. Perfusion of 4-week post-TAC hearts with αGA resulted in additional slowing of CV. Time points include sham (S), 2 weeks (2W), 4 weeks (4W), and 8 weeks (8W) post-TAC.

Table 1.

Gross and Cellular Hypertrophy in TAC Mice

| Sham | Four Weeks | Eight Weeks | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heart weight, mg | 139±5 (12) | 282±11 (13)* | 324±9 (11)† |

| Body weight, g | 27.9±0.8 (12) | 24.1±0.9 (13) | 28.5±0.7 (11) |

| HW/BW, mg/g | 5.00±0.16 (12) | 11.81±0.55 (13)* | 11.5±0.48 (11) |

| Cell length, μm | 158±3 (55) | 192±4 (55)* | 206±5 (55)* |

| Cell width, μm | 24.7±0.7 (55) | 39.2±1.0 (55)* | 38.5±1.3 (55)* |

| Cell area, μm2 | 3934±155 (55) | 7528±237 (55) | 7873±268 (55) |

All values are means±SEM. Numbers in parentheses indicate sample size.

P<0.05 compared to sham,

P<0.05 compared to sham and 4 weeks.

Table 2.

Echocardiographic Analysis of TAC Mice

| Baseline |

Two Weeks |

Four Weeks |

Eight Weeks |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sham (21) | TAC (29) | Sham (21) | TAC (25) | Sham (21) | TAC (28) | Sham | TAC (6) | |

| LVAWd, mm | 0.92±0.03 | 0.90±0.02 | 0.89±0.04 | 1.22±0.05* | 0.89±0.03 | 1.39±0.03* | n/d | 1.37±0.06 |

| LVAWs, mm | 1.30±0.04 | 1.24±0.03 | 1.27±0.04 | 1.63±0.07* | 1.23±0.04 | 1.71±0.03* | n/d | 1.88±0.08 |

| LVPWd, mm | 0.86±0.03 | 0.82±0.02 | 0.88±0.03 | 1.21±0.06* | 0.87±0.03 | 1.44±0.05* | n/d | 1.52±0.07 |

| LVPWs, mm | 1.27±0.02 | 1.24±0.03 | 1.24±0.03 | 1.59±0.07* | 1.27±0.03 | 1.80±0.04* | n/d | 1.82±0.08 |

| LVIDd, mm | 3.86±0.06 | 3.82±0.06 | 3.84±0.07 | 3.86±0.16 | 3.91±0.06 | 4.35±0.08* | n/d | 4.33±0.08 |

| LVIDs, mm | 2.33±0.06 | 2.28±0.05 | 2.28±0.06 | 2.38±0.11 | 2.33±0.06 | 3.06±0.08* | n/d | 3.30±0.09 |

| FS, % | 39.85±0.89 | 40.26±0.96 | 40.68±0.91 | 38.66±1.74 | 40.30±1.01 | 29.22±1.09* | n/d | 23.85±1.65 |

All values are means±SEM. LVAW, LV anterior wall; LVPW, LV posterior wall; LVID, LV internal dimension; d, diastole; s, systole; FS, fractional shortening.

P<0.05 compared to age-matched sham. Numbers in parentheses indicate sample size.

GJR and Altered Cx43 Phosphorylation Status

To determine whether cardiac hypertrophy was associated with GJR, including changes in posttranslational phosphorylation state, we analyzed Cx43 expression and localization by immunoblotting and immunohistochemical staining with a panel of antibodies with defined specificities for total or phosphorylated forms of Cx43. As shown in Figure 1B, during the first 5 days after imposition of TAC, there was a transient increase in the overall abundance of Cx43 within total cardiac lysates; however, this was followed by a progressive decline, such that by 4 weeks after pressure overload, Cx43 content had fallen to 49±3.4% of control levels (n=4 each group; P<0.05). To more specifically examine the effects of TAC on Cx43 within the gap junctions, we performed Western blots on Triton X-100 insoluble fractions, which enrich for junctional membrane proteins. Both N-terminal and C-terminal pan-Cx43 antibodies demonstrated a progressive decline in junctional Cx43 abundance following TAC, diminishing to 60±2.7% of control levels 4 weeks after TAC. Moreover, phospho-specific antibodies demonstrated a substantial diminution in both pS365, as well as pS325/328/330 forms of Cx43 within a week after imposition of TAC.

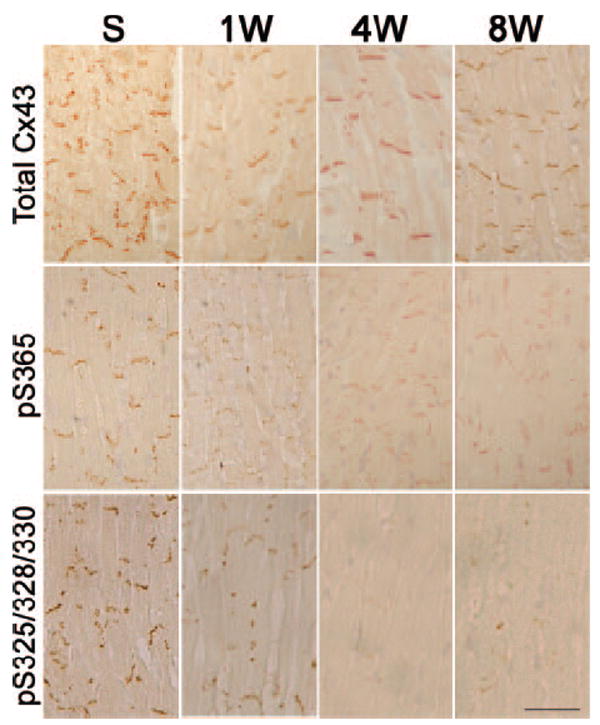

These results were confirmed and extended by immunohistochemical studies, which revealed substantial loss of Cx43 gap junctional plaques within 1 week after TAC (Figure 1C). Concordant with the Western blot studies, immunostaining with antibodies specific for pS365-Cx43 and pS325/328/330-Cx43 also demonstrated a substantial loss of these posttranslationally modified forms of Cx43, as seen in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Aberrant phosphorylation of Cx43 in TAC mice. Sections were prepared at the indicated time points and stained with antibodies recognizing all forms of Cx43 (Total Cx43), S365-phosphoCx43 (pS365), or S325/328/330-phosphoCx43 (pS325). Diminution of both phosphorylated forms of Cx43 is evident as early as 1 week post-TAC. Scale bar=50 μm.

Impulse Propagation in Hypertrophied Hearts

We next determined whether the changes in Cx43 expression were accompanied by alterations in impulse propagation, using optical mapping techniques. We observed progressive slowing of transverse conduction velocity (CVmin) following the imposition of TAC, as illustrated in Figure 1D and summarized in Table 3. As early as 1 week after TAC, CVmin had diminished significantly from 0.55±0.02 to 0.47±0.02 m/sec, and by 8 weeks after imposition of the hemodynamic overload, CVmin had fallen to 0.42±0.03 m/sec. To gain some insight into the extent of residual cell–cell coupling that existed in hypertrophied hearts, we assessed the effects of the relatively selective gap junction uncoupler αGA on impulse propagation in an additional cohort of hearts studied 4 weeks after imposition of TAC. Treatment of hypertrophied hearts with αGA depressed CV further, to 0.25±0.01 m/sec. These data suggest the presence of some degree of residual gap junction function, despite the extensive GJR that occurs in response to pressure overload.

Table 3.

Conduction Parameters in TAC Mice

| Time Course Study |

GA Study |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sham | One Week | Four Weeks | Eight Weeks | Four Weeks Without GA | Four Weeks With GA | |

| CVmin, m/sec | 0.55±0.02 (9) | 0.47±0.02 (6)* | 0.43±0.02 (9)* | 0.42±0.03 (5)* | 0.38±0.03 (5)* | 0.25±0.01 (5)† |

| CVmax, m/sec | 0.84±0.04 (9) | 0.80±0.03 (6) | 0.78±0.03 (9) | 0.61±0.04 (5)* | 0.67±0.05 (5) | 0.54±0.06 (5) |

| AR | 1.54±0.07 (9) | 1.71±0.07 (6) | 1.85±0.10 (9) | 1.76±0.10 (5) | 1.77±0.11 (5) | 2.2±0.18 (5) |

| VERP, ms | 42.7±2.7 (9) | 57.4±3.6 (9) | ||||

All values are means±SEM.

P<0.05 compared to sham,

P<0.05 compared to 4 weeks without GA. Numbers in parentheses indicate sample size.

Inasmuch as cardiac hypertrophy in many animal models is associated with action potential prolongation, we also measured ventricular effective refractory periods. VERPs in hearts from 4 week TAC animals were significantly prolonged compared to sham operated controls (57.4±3.6 ms (n=9) versus 42.7±2.7 ms (n=9); P=0.005), suggesting electric remodeling of repolarizing currents and consistent with previous reports.25

We next assessed whether hypertrophied hearts were more susceptible to the induction of ventricular arrhythmias. Somewhat surprisingly, none of the 9 hearts isolated from 4 week TAC mice developed ventricular arrhythmias in response to programmed electric stimulation.

Inhibition of Pathological GJR With Spironolactone

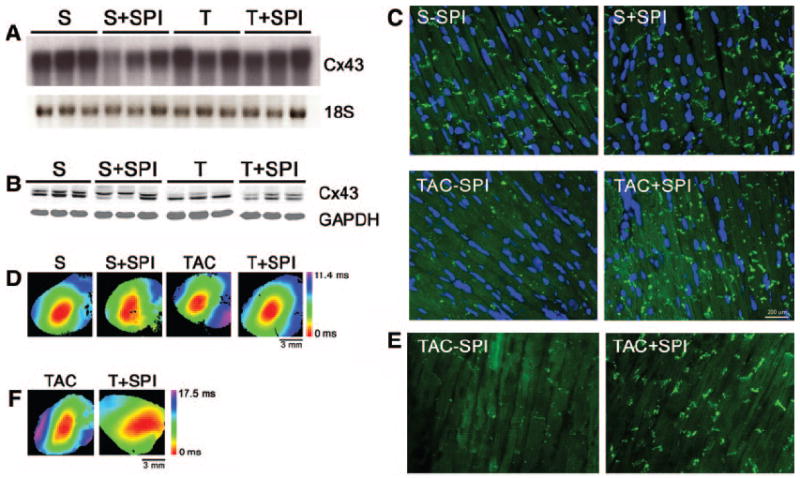

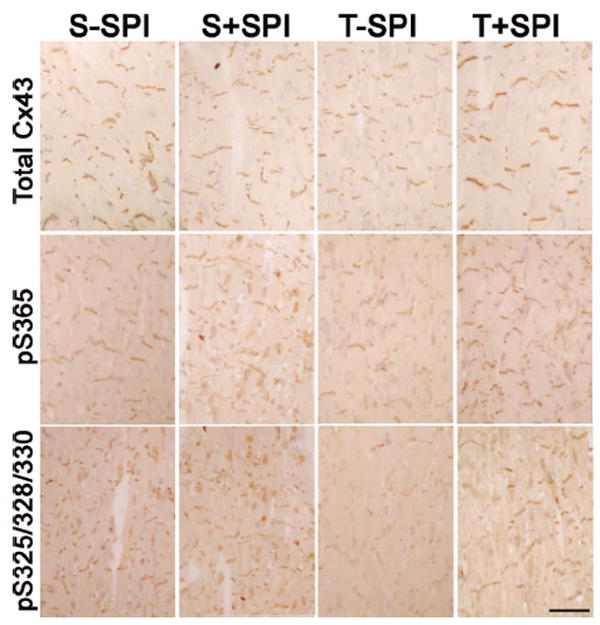

Aldosterone antagonists have been shown to reduce sudden cardiac death in clinical trials of myopathic patients. We therefore explored whether treatment with spironolactone might influence the extent of pathological GJR observed in response to pressure overload. Accordingly, we examined additional cohorts of mice subjected to either sham operation or TAC, with half of each group then randomized to receive either a normal chow diet or chow supplemented with spironolactone (50 mg/kg per day) for a period of 4 weeks. Interestingly, there was no effect of TAC or spironolactone on Cx43 mRNA expression (Figure 3A). Moreover, spironolactone did not diminish the overall hypertrophic response, although there was a demonstrable reduction in the extent of cardiac fibrosis (Table 4). However, compared to TAC mice receiving a normal chow diet, those treated with spironolactone showed a significant increase in the abundance of slower mobility, hyperphosphorylated forms of Cx43 (Figure 3B and Table 4), as well as a marked increase in typical gap junctional plaques (Figure 3C). The normalization of gap junctional appearance was also observed using antibodies specific for pS365-Cx43 and pS325/328/330-Cx43 (Figure 4). These molecular changes indicative of reverse remodeling were associated with a significant improvement in conduction velocity, as shown in Figure 3D and summarized in Table 4.

Figure 3.

Inhibition of GJR with spironolactone. Groups of mice were subjected to either sham operation (S) or TAC (T) and fed either normal chow (−SPI) or chow supplemented with spironolactone (+SPI). Analyses were performed 4 weeks after surgery. A, Northern blot analysis demonstrates no changes in Cx43 mRNA abundance. B, Western blot analysis with a panCx43 antibody demonstrates increased slow-mobility Cx43 in both S+SPI and T+SPI hearts. C, Representative immunofluorescent staining demonstrates loss of Cx43 gap junction plaques in TAC−SPI hearts but substantial improvement in mice treated with spironolactone (TAC+SPI). D, Representative optical maps from each of the 4 groups. E, Representative immunofluorescent staining in reversal experiment demonstrates improvement after 2 weeks of treatment with spironolactone. F, Representative optimal maps from reversal experiment.

Table 4.

Effects of Spironolactone in TAC Mice

| Prevention Study |

Reversal Study |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sham−SPI | Sham+SPI | TAC−SPI | TAC+SPI | TAC−SPI | TAC+SPI | |

| HW/BW, mg/g | 4.32±0.76 (13) | 3.58±0.30 (13) | 8.47±0.42 (12)* | 7.76±0.30 (13)* | 8.98±1.15 (5) | 8.10±0.73 (6) |

| Fibrosis index | 6.9±1.6 (5) | 5.3±0.8 (5) | 17.5±1.6 (5)* | 10.1±1.3 (5)† | 21.0±3.3 (3) | 17.3±4.0 (3) |

| P-Cx43, % | 100±3 (4) | 118±5% (4)* | 41±6% (4)* | 72±9 (4)† | 28±10.9 (4) | 95±31 (4)‡ |

| CVmin, m/sec | 0.44±0.02 (8) | 0.41±0.04 (7) | 0.28±0.02 (8)* | 0.36±0.01 (8)† | 0.22±0.02 (4) | 0.32±0.03 (6)‡ |

| CVmax, m/sec | 0.70±0.02 (8) | 0.60±0.07 (7) | 0.47±0.02 (8)* | 0.53±0.04 (8)* | 0.34±0.04 (4) | 0.54±0.02 (6)‡ |

| AR | 1.61±0.18 | 1.46±0.08 | 1.50±0.11 | 1.68±0.08 | 1.60±0.18 | 1.76±0.11 |

All values are means±SEM. P-Cx43 indicates hyperphosphorylated Cx43; values normalized to the sham without spironolactone (Sham−SPI) group. AR indicates anisotropic ratio.

P<0.05 compared to the Sham−SPI,

P<0.05 compared to Sham−SPI and TAC without SPI (TAC−SPI) (prevention study),

P<0.05 compared to TAC−SPI (reversal study). Numbers in parentheses indicate sample size.

Figure 4.

Enhanced Cx43 phosphorylation with spironolactone. Sections were prepared from each of the experimental groups 4 weeks after randomization and stained with antibodies recognizing all forms of Cx43 (Total Cx43), S365-phosphoCx43 (pS365), or S325/328/330-phosphoCx43 (pS325). Representative images are shown. Reduced immunoreactive Cx43 is seen in the TAC−SPI hearts with all 3 antibodies. Spironolactone treatment partially restores the appearance of the gap junctional plaques. Scale bar=50 μm.

Reversal of Pathological GJR With Spironolactone

The previous experiment established that treatment with spironolactone could blunt the development of pathological GJR. We next addressed the clinically more relevant question of whether mineralocorticoid receptor antagonism could reverse the severity of GJR in hearts with established pathology. Therefore, an additional cohort of mice was subjected to TAC. Two weeks later, at which time substantial hypertrophy was evident by echocardiography, half of the banded mice were randomly chosen to receive either a normal chow diet or chow supplemented with spironolactone (50 mg/kg per day) for an additional 2 week period. As previously observed, spironolactone treatment did not influence the extent of hypertrophy as determined by heart weight/body weight measurements (Table 4). Unlike the prevention study, in which spironolactone was given for 4 weeks, this shorter course of treatment was not associated with significant amelioration of the fibrotic response (Table 4). Nonetheless, as before, spironolactone treatment was associated with a significant increase in the slower mobility, hyperphosphorylated forms of Cx43 (Table 4), a marked increase in typical gap junction plaques (Figure 3E), as well as a significant improvement in epicardial conduction velocity (Figure 3F and Table 4).

Discussion

Impulse propagation reflects a complex interplay between structural factors and active and passive membrane properties. In the setting of pathological stressors, structural and electric remodeling occurs, leading to the formation of a substrate that may be susceptible to the initiation and maintenance of ventricular tachyarrhythmias. In this study, we evaluated the effects of pressure overload, a commonly encountered pathological stimulus, on GJR and impulse propagation. The major findings in this study include the following: (1) pressure overload hypertrophy is associated with early and progressive reduction in junctional Cx43; (2) dephosphorylation of Cx43 at serines 365 and 325/328/330 occur contemporaneously with this loss of junctional Cx43; (3) impulse propagation slows significantly during progressive hypertrophy; (4) mineralocorticoid receptor blockade blunts the development of GJR associated with pathological cardiac hypertrophy, both at the molecular and functional levels; and (5) mineralocorticoid receptor blockade potently reverses established GJR in hypertrophied hearts.

Despite evidence of substantial GJR following TAC, the hypertrophied hearts were not especially sensitive to the induction of ventricular arrhythmias. This behavior contrasts with several genetic models of uncoupling in which Cx43 expression is more profoundly reduced. At the extreme end of the spectrum are the Cx43 conditional knockout mice, in which spontaneous arrhythmias are fully penetrant17; less fulminant are the heterozygous I130T ODDD mutant mice,22 with Cx43 levels ≈10% of normal and easily inducible but without spontaneous arrhythmias. The TAC mice display an even milder phenotype, and despite evidence of substantial GJR, the incremental slowing of CV after infusion with GA suggests the presence of residual gap junction function. In addition, it is conceivable that the choice of strain used in this study reduced the arrhythmic phenotype; C57BL/6 mice are relatively resistance to induction of ventricular tachycardia.26

Our data are consistent with previous studies demonstrating aberrant posttranslational phosphorylation of Cx43 in response to pathological stimuli, including models of nonischemic heart failure in the rabbit and pacing-induced heart failure in the dog.27-30 With respect to the molecular mechanisms of GJR, through the use of phospho-specific antibodies, we identified at least 2 regions, serine 365 and a triplet of serines at 325, 328, and 330, within the Cx43 carboxyl terminus that are dephosphorylated as early as 1 week after imposition of hemodynamic overload. Phosphorylation at serine 365 causes a shift in Cx43 mobility to the P1 form and is thought to play a gatekeeper role preventing downregulation via protein kinase C phosphorylation at serine 368.25 At least one of the triplet of serines at residues 325/328/330 is phosphorylated via casein kinase I, and these sites appear to play an integral role in gap junction assembly and formation of the P2 isoform.21,31 Recent data demonstrate that phosphorylation at these sites is markedly reduced in response to cardiac ischemia.21 Taken together with the present data, we propose that casein kinase I–dependent phosphorylation of Cx43 may not only play a key role in normal Cx43 trafficking and membrane targeting but in the pathological remodeling of gap junctions as well. Indeed, we have recently generated site-specific Cx43 mutant knock-in mice to directly test this hypothesis.

Aldosterone antagonism has been shown in 2 major clinical trials to diminish mortality in patients with heart failure.32,33 The mechanisms responsible for this salutary effect are uncertain but appear to reflect, at least in part, a diminution in sudden arrhythmic death. Given this observation and the association of GJR with arrhythmogenesis, we tested whether spironolactone might influence Cx43 expression and impulse propagation in diseased myocardium. Indeed, in addition to the anticipated modest antifibrotic effects of concurrent aldosterone receptor blockade,34 the initiation of spironolactone treatment at the time of aortic banding significantly blunted the molecular and functional manifestations of GJR.

In the clinical setting, patients typically present with demonstrable heart disease. Therefore, we also examined the effects of spironolactone therapy on mice with established hypertrophy. Importantly, mice in the reversal study also demonstrated a significant enhancement of CV but without measurable diminution in the extent of fibrosis. These data argue against fibrosis playing a substantial role in the enhanced propagation. CV is also determined by inward sodium currents. However, there is evidence indicating that aldosterone enhances INa in adult mouse myocytes, suggesting that mineralocorticoid blockade with spironolactone is not likely to improve CV through an increase in sodium current density.35 Nonetheless, additional studies will be required to ascertain the relative importance of each of these contributing factors.

Interestingly, spironolactone enhanced Cx43 phosphorylation not only in TAC mice but also appeared to have some effect in sham-treated controls. These data suggest a potential role for mineralocorticoid-dependent regulation of cell–cell coupling even at baseline, not only when neurohormonal axes are activated by pathological stressors. Whether there is a signaling pathway that includes the upstream mineralocorticoid receptor and the downstream target casein kinase I will require additional study. Additionally, it is conceivable that regulation of phosphatase activity may also play a role in the GJR process, as recently suggested by Ai and Pogwizd.27

In summary, our data demonstrate that hemodynamic overload leads to substantial GJR and that spironolactone potently blunts the development of this pathological remodeling, as well as reverses, established GJR. Posttranslational phosphorylation of Cx43 appears to play an integral role in the regulation of gap junction formation as well as pathological remodeling. We suggest that modulation of gap junction regulation may represent a rational antiarrhythmic therapeutic target.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding This study was supported by NIH grants HL64757, HL82727, and HL81336 (to G.I.F.) and GM55632 (to P.D.L.); a Glorney-Raisbeck fellowship (to L.I.G.); a Sarnoff Cardiovascular Research fellowship (to F.M.V.); and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute medical student fellowship (to N.S.).

Footnotes

Disclosures None.

References

- 1.McLenachan JM, Dargie HJ. Left ventricular hypertrophy as a factor in arrhythmias and sudden death. Am J Hypertens. 1989;2:128–131. doi: 10.1093/ajh/2.2.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kannel WB. Left ventricular hypertrophy as a risk factor: the Framingham experience. J Hypertens Suppl. 1991;9:S3–S8. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199112002-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Messerli FH, Ketelhut R. Left ventricular hypertrophy: an independent risk factor. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1991;17(suppl 4):S59–S66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Messerli FH, Soria F. Hypertension, left ventricular hypertrophy, ventricular ectopy, and sudden death. Am J Med. 1992;93:21S–26S. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(92)90291-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haider AW, Larson MG, Benjamin EJ, Levy D. Increased left ventricular mass and hypertrophy are associated with increased risk for sudden death. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;32:1454–1459. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00407-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kang YJ. Cardiac hypertrophy: a risk factor for QT-prolongation and cardiac sudden death. Toxicol Pathol. 2006;34:58–66. doi: 10.1080/01926230500419421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saffitz JE, Kleber AG. Effects of mechanical forces and mediators of hypertrophy on remodeling of gap junctions in the heart. Circ Res. 2004;94:585–591. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000121575.34653.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Teunissen BE, Jongsma HJ, Bierhuizen MF. Regulation of myocardial connexins during hypertrophic remodelling. Eur Heart J. 2004;25:1979–1989. doi: 10.1016/j.ehj.2004.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dodge SM, Beardslee MA, Darrow BJ, Green KG, Beyer EC, Saffitz JE. Effects of angiotensin II on expression of the gap junction channel protein connexin43 in neonatal rat ventricular myocytes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;32:800–807. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00317-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Darrow BJ, Fast VG, Kleber AG, Beyer EC, Saffitz JE. Functional and structural assessment of intercellular communication. Increased conduction velocity and enhanced connexin expression in dibutyryl cAMP-treated cultured cardiac myocytes. Circ Res. 1996;79:174–183. doi: 10.1161/01.res.79.2.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Uzzaman M, Honjo H, Takagishi Y, Emdad L, Magee AI, Severs NJ, Kodama I. Remodeling of gap junctional coupling in hypertrophied right ventricles of rats with monocrotaline-induced pulmonary hypertension. Circ Res. 2000;86:871–878. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.8.871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Emdad L, Uzzaman M, Takagishi Y, Honjo H, Uchida T, Severs NJ, Kodama I, Murata Y. Gap junction remodeling in hypertrophied left ventricles of aortic-banded rats: prevention by angiotensin II type 1 receptor blockade. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2001;33:219–231. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2000.1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Severs NJ, Coppen SR, Dupont E, Yeh HI, Ko YS, Matsushita T. Gap junction alterations in human cardiac disease. Cardiovasc Res. 2004;62:368–377. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2003.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Severs NJ, Dupont E, Thomas N, Kaba R, Rothery S, Jain R, Sharpey K, Fry CH. Alterations in cardiac connexin expression in cardiomyopathies. Adv Cardiol. 2006;42:228–242. doi: 10.1159/000092572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Formigli L, Ibba-Manneschi L, Perna AM, Pacini A, Polidori L, Nediani C, Modesti PA, Nosi D, Tani A, Celli A, Neri-Serneri GG, Quercioli F, Zecchi-Orlandini S. Altered Cx43 expression during myocardial adaptation to acute and chronic volume overloading. Histol Histopathol. 2003;18:359–369. doi: 10.14670/HH-18.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rockman HA, Wachhorst SP, Mao L, Ross J., Jr ANG II receptor blockade prevents ventricular hypertrophy and ANF gene expression with pressure overload in mice. Am J Physiol. 1994;266:H2468–H2475. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1994.266.6.H2468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gutstein DE, Morley GE, Tamaddon H, Vaidya D, Schneider MD, Chen J, Chien KR, Stuhlmann H, Fishman GI. Conduction slowing and sudden arrhythmic death in mice with cardiac-restricted inactivation of connexin43. Circ Res. 2001;88:333–339. doi: 10.1161/01.res.88.3.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Redfern CH, Degtyarev MY, Kwa AT, Salomonis N, Cotte N, Nanevicz T, Fidelman N, Desai K, Vranizan K, Lee EK, Coward P, Shah N, Warrington JA, Fishman GI, Bernstein D, Baker AJ, Conklin BR. Conditional expression of a Gi-coupled receptor causes ventricular conduction delay and a lethal cardiomyopathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:4826–4831. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.9.4826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gutstein DE, Liu FY, Meyers MB, Choo A, Fishman GI. The organization of adherens junctions and desmosomes at the cardiac intercalated disc is independent of gap junctions. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:875–885. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Solan JL, Marquez-Rosado L, Sorgen PL, Thornton PJ, Gafken PR, Lampe PD. Phosphorylation at S365 is a gatekeeper event that changes the structure of Cx43 and prevents down-regulation by PKC. J Cell Biol. 2007;179:1301–1309. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200707060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lampe PD, Cooper CD, King TJ, Burt JM. Analysis of connexin43 phosphorylated at S325, S328 and S330 in normoxic and ischemic heart. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:3435–3442. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kalcheva N, Qu J, Sandeep N, Garcia L, Zhang J, Wang Z, Lampe PD, Suadicani SO, Spray DC, Fishman GI. Gap junction remodeling and cardiac arrhythmogenesis in a murine model of oculodentodigital dysplasia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:20512–20516. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705472105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leaf DE, Feig JE, Lader JM, Riva PL, Vasquez C, Yu C, Kontogeorgis A, Peters NS, Fisher EA, Gutstein DE, Morley GE. Connexin40 imparts conduction heterogeneity to atrial tissue. Circ Res. 2008;103:1001–1008. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.168997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gutstein DE, Morley GE, Fishman GI. Conditional gene targeting of connexin43: exploring the consequences of gap junction remodeling in the heart. Cell Commun Adhes. 2001;8:345–348. doi: 10.3109/15419060109080751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marionneau C, Brunet S, Flagg TP, Pilgram TK, Demolombe S, Nerbonne JM. Distinct cellular and molecular mechanisms underlie functional remodeling of repolarizing K+ currents with left ventricular hypertrophy. Circ Res. 2008;102:1406–1415. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.170050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maguire CT, Wakimoto H, Patel VV, Hammer PE, Gauvreau K, Berul CI. Implications of ventricular arrhythmia vulnerability during murine electrophysiology studies. Physiol Genomics. 2003;15:84–91. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00034.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ai X, Pogwizd SM. Connexin 43 downregulation and dephosphorylation in nonischemic heart failure is associated with enhanced colocalized protein phosphatase type 2A. Circ Res. 2005;96:54–63. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000152325.07495.5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Akar FG, Spragg DD, Tunin RS, Kass DA, Tomaselli GF. Mechanisms underlying conduction slowing and arrhythmogenesis in nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy. Circ Res. 2004;95:717–725. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000144125.61927.1c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Poelzing S, Akar FG, Baron E, Rosenbaum DS. Heterogeneous connexin43 expression produces electrophysiological heterogeneities across ventricular wall. Am J Physiol. 2004;286:H2001–H2009. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00987.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Akar FG, Nass RD, Hahn S, Cingolani E, Shah M, Hesketh GG, DiSilvestre D, Tunin RS, Kass DA, Tomaselli GF. Dynamic changes in conduction velocity and gap junction properties during development of pacing-induced heart failure. Am J Physiol. 2007;293:H1223–H1230. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00079.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cooper CD, Lampe PD. Casein kinase 1 regulates connexin-43 gap junction assembly. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:44962–44968. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209427200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pitt B, Zannad F, Remme WJ, Cody R, Castaigne A, Perez A, Palensky J, Wittes J. The effect of spironolactone on morbidity and mortality in patients with severe heart failure. Randomized Aldactone Evaluation Study Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:709–717. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199909023411001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pitt B, Remme W, Zannad F, Neaton J, Martinez F, Roniker B, Bittman R, Hurley S, Kleiman J, Gatlin M. Eplerenone, a selective aldosterone blocker, in patients with left ventricular dysfunction after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1309–1321. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kuster GM, Kotlyar E, Rude MK, Siwik DA, Liao R, Colucci WS, Sam F. Mineralocorticoid receptor inhibition ameliorates the transition to myocardial failure and decreases oxidative stress and inflammation in mice with chronic pressure overload. Circulation. 2005;111:420–427. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000153800.09920.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boixel C, Gavillet B, Rougier JS, Abriel H. Aldosterone increases voltage-gated sodium current in ventricular myocytes. Am J Physiol. 2006;290:H2257–H2266. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01060.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]