Abstract

Background

Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is an aggressive skin cancer with a mortality of 33%. Advanced disease at diagnosis is a poor prognostic factor, suggesting that earlier detection may improve outcome. No systematic analysis has been published to define the clinical features that are characteristic of MCC.

Objective

To define the clinical characteristics present at diagnosis in order to identify features that may aid clinicians in recognizing MCC.

Methods

Cohort study of 195 patients diagnosed with MCC between 1980 and 2007. Data were collected prospectively in the majority of cases, and medical records were reviewed.

Results

An important finding was that 88% of MCCs were asymptomatic (nontender) despite rapid growth in the prior 3 months (63% of lesions) and being red or pink (56%). A majority of MCC lesions (56%) were presumed to be benign, with a cyst/acneiform lesion being the single most common diagnosis (32%) given at biopsy. The median delay from lesion appearance to biopsy was 3 months (range 1–54 months), and median tumor diameter was 1.8 cm. Similar to prior studies, 81% of primary MCCs occurred on UV-exposed sites, and our cohort was elderly (90% over age 50), predominantly Caucasian (98%), and often profoundly immune suppressed (7.8%). An additional novel finding was that chronic lymphocytic leukemia was more than 30-fold over-represented among MCC patients.

Limitations

The study was limited to patients seen at a tertiary care center. Complete clinical data could not be obtained on all patients. This study could not assess the specificity of the clinical characteristics of MCC.

Conclusions

This study is the first to define clinical features that may serve as clues in the diagnosis of MCC. The most significant features can be summarized in an acronym: AEIOU -Asymptomatic/lack of tenderness, Expanding rapidly, Immune suppression, Older than age 50, and UV-exposed site on a person with fair skin. In our series, 89% of primary MCCs had three or more of these findings. Although MCC is uncommon, when present in combination, these features may indicate a concerning process that would warrant biopsy. In particular, a lesion that is red and expanding rapidly yet asymptomatic should be of concern.

Introduction

Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is a highly aggressive skin cancer with a mortality of approximately 33% at 3 years1, higher than that of melanoma (approximately 15%). Data from Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) show a three-fold increase in MCC from 0.15 to 0.44 per 100,000 annually from the years 1986 to 20012. This trend is continuing, and approximately 1000–1500 new cases will be diagnosed in the United States in 20073, 4. Several factors likely contribute to this including an aging population, increased aggregate sun exposure and a higher number of immune suppressed individuals. Furthermore, the advent of the immunohistochemical marker cytokeratin-20 (CK-20) improved recognition of this disease. In the era before widespread CK-20 immunohistochemistry, laborious electron microscopy was required to make an accurate MCC diagnosis. Indeed, 66% of MCC cases in one series would have been misdiagnosed (as metastatic small cell lung cancer, basal cell carcinoma, lymphoma or other metastatic carcinoma) if electron microscopy had not been performed demonstrating the characteristic “neurosecretory granules within cytoplasmic extensions”5.

Management of MCC is controversial. To date there have been no controlled therapeutic trials in this disease. In most cases, surgical excision with sentinel lymph node biopsy1, 6 followed by radiation7, 8 is indicated. Conventional adjuvant chemotherapy lacks evidence of survival benefit and may in fact be associated with poorer outcomes1, 9. A consensus treatment algorithm has been developed by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network10.

MCC prognosis is highly associated with the extent of disease at presentation. Disease-specific survival rates for local disease are greater than 90%, falling to 52% with nodal involvement3. If distant metastatic disease is present, expected survival is typically less than 10% at three years1. As delay in diagnosis could allow disease progression, early detection and clinician recognition of this disease may improve survival rates. At present, a detailed description of the clinical characteristics of MCC at the time of diagnosis has not been published. Specifically, a PubMed search of “Merkel cell carcinoma clinical features” (performed on 10/24/07) yielded 87 studies, none of which described the clinician’s presumptive diagnosis, the color or symptomatic nature of the lesion, or the time to biopsy after lesion appearance.

The purpose of this study is to identify key clinical features that may assist the clinician in recognizing this aggressive skin cancer at an earlier and potentially more curable point.

Patients and Methods

Institutional review board approval was obtained from each institution. Tumor registry data and prospective patient identification (beginning in 2003) were used to identify 195 patients from 3 medical centers in Boston (Dana Farber Cancer Institute, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Massachusetts General Hospital) and 2 medical centers in Seattle (Seattle Cancer Care Alliance, and University of Washington Medical Center). The study included patients with a pathologic diagnosis of MCC between 1980 and 2007.

Patient characteristics, clinical features of the lesion (i.e. site, tenderness, color, growing time, diameter), stage at presentation, interval from appearance to biopsy and the clinician’s impression at the time of biopsy were reviewed. The initial clinical impression was that recorded by the physician in either the clinical notes or on the pathology requisition. Presumptive diagnoses were listed in 106 patients. Of these, 78 had a single diagnosis while 28 had multiple clinical impressions reported; each of the 141 impressions was considered independently. The clinical impressions were stratified into benign, malignant and indeterminate lesions.

Estimation of age-adjusted chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) prevalence in the US was determined for the 50–69 and ≥70 year old age groups using the SEER11 database (2004 data; 30,465, and 51,579 cases, respectively) and dividing this by the US Census Bureau12 2004 population estimate for those age groups (60,489,662, and 26,653,288 persons, respectively). For solid organ transplant patient prevalence, a specific query was submitted to UNOS13 (United Network for Organ Sharing) which provided data regarding all living solid organ transplant recipients engrafted between 10/1/1986 and 6/30/2006 who have not had a reported graft failure (223,307 cases). This total number was divided by the 2006 US Census Bureau’s12 estimated total US population (299,398,484 persons).

Results

Patient characteristics

As shown in Table I, the median age at diagnosis was 69 years, with 90% of patients being over age 50. There was a slight male predominance with a ratio of 1.4:1 (58.5% males and 41.5% females). The vast majority of patients were Caucasian (98%), with only 4 patients being non-white (3 Asian and 1 Black). Profound immunosuppression including HIV (3 patients), CLL (8 patients) or solid organ transplant (4 patients) was noted in 7.8% of patients. The mean age of presentation of the immunosuppressed patients in this series was comparable to that of the immunocompetent group, 65 vs. 67 years respectively.

Table I.

Patient Characteristics at Diagnosis

| No. | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs) (Median 69, Range 34–97) | ||

| <50 | 20 | 10.3% |

| 50–70 | 92 | 47.1% |

| >70 | 83 | 42.6% |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 114 | 58.5% |

| Female | 81 | 41.5% |

| Race | ||

| White | 191 | 97.9% |

| Black | 1 | 0.5% |

| Asian | 3 | 1.5% |

| Immunosuppression (n=193) | ||

| HIV | 3 | 1.6% |

| Solid organ transplant | 4 | 2.1% |

| Chronic lymphocytic leukemia | 8 | 4.1% |

| TOTAL | 15 | 7.8%‡ |

| Extent of Disease (n=187) | ||

| Local only (< 2cm diameter) | 68 | 36.4% |

| Local only (≥ 2cm diameter) | 38 | 20.3% |

| Nodal | 70 | 37.4%T |

| Distant Metastatic | 11 | 5.9% |

| Interval from Appearance to Biopsy (n=144) | ||

| Median: 3 months | ||

| Mean: 5.3 months | ||

| Range: 1–54 months | ||

N=195 except when otherwise noted.

16-fold over-representation of immunosuppression as compared to the general US population based on estimated prevalences of: chronic lymphocytic leukemia 0.029%, HIV 0.4% and living solid organ transplant recipients with viable grafts 0.075%

Nodal disease assessed by palpation or histologic evaluation (when performed).

One hundred and six patients (57%) presented with local disease. Seventy patients (37%) presented with nodal disease; of these, 27 (14% of the total patients) had nodal presentation with no identified primary. Eleven patients (6%) presented with metastatic disease. Information regarding the time from lesion appearance to biopsy was available in 144 patients with a primary lesion. The median time to biopsy was 3 months (mean 5.3 months, range 1–54 months).

Tumor characteristics

Examples of MCC presentation which include lesions that initially were thought to be a cyst or other benign process are shown in Figure I. As outlined in Table II, the diameter of the primary tumor was <1 cm in 32 patients (21.3%), 1–2cm in 65 patients (43.3%) and >2 cm in 53 patients (35.3%). The most common color of the primary lesion was red/pink, seen in 56% of patients, followed by blue/violaceous noted in 26%. Most (88%) of the lesions were asymptomatic. Sixty-three percent of patients reported rapid growth of their tumor within 3 months. Only a minority (11%) reported no changes in the size of their primary lesion.

Figure I. Clinical examples of MCC.

A. An eyelid lesion that was thought to be a rapidly growing chalazion.

B. A non-tender MCC that arose on the buttock of a patient with HIV. The MCC diagnosis was markedly delayed because of a history of multiple prior epidermoid cysts.

C. A finger lesion that was clinically suggestive of a pyogenic granuloma or amelanotic melanoma.

D. A MCC that arose on a sun-exposed area of the arm in a man with fair skin (photo courtesy of http://www.merkelcell.co.uk, used with permission).

Table II.

Merkel Cell Carcinoma Primary Tumor Characteristics

| No. | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Size (N=150) | ||

| <1 cm | 32 | 21.3% |

| 1–2 cm | 65 | 43.3% |

| >2 cm | 53 | 35.3% |

| Color (N=81) | ||

| Red/Pink | 45 | 55.6% |

| Blue/Violaceous | 21 | 25.9% |

| Skin colored | 13 | 16.0% |

| Yellowish/White | 2 | 2.5% |

| Asymptomatic (N=89) | ||

| Yes | 78 | 87.6% |

| No | 11 | 12.4% |

| Expansion Rate (n=91) | ||

| Rapid (≤3 months) | 57 | 62.6% |

| Slowly (>3 months) | 24 | 25.4% |

| No changes noted | 10 | 11.0% |

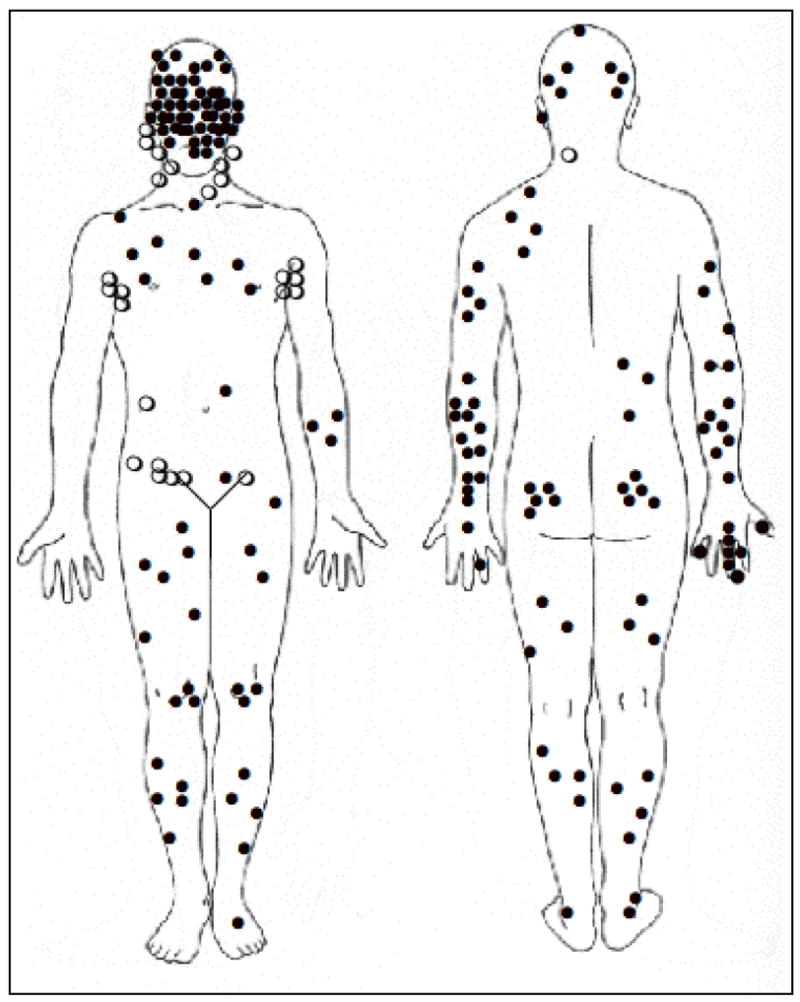

Figure II shows the distribution of primary MCC tumors as well as those that presented in the lymph node without a known primary. Most lesions appeared on sun-exposed skin; however, 19% presented on the buttock or other minimally sun-exposed areas. The most common anatomic site of the primary lesion was the head and neck (29%), followed by the lower limbs (24%) and upper extremities (21%). Nodal disease in the setting of no identified primary tumor was diagnosed in 27 patients (14%). (Table III)

Figure II. Distribution of MCC at Presentation in 195 Patients.

A primary skin lesion (solid circle ●) was seen in 168 patients (86%). Twenty-seven (14%) presented with nodal involvement and no known primary (open circles ○).

Table III.

Presenting Anatomic Location

| No. | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Prmary Skin Lesion | 168 | 85% |

| Head and Neck | 56 | 29% |

| Lower Limb | 46 | 24% |

| Upper Limb | 40 | 21% |

| Trunk | 16 | 8% |

| Buttock | 9 | 5% |

| Vulva | 1 | 0.5% |

| No Known Primary (nodal presentation) | 27 | 14% |

Among the group of 106 patients for whom a presumed clinical diagnosis was reported, the majority (56%) of clinical impressions were benign (Table IV). A cyst or acneiform lesion was the single most common presumptive diagnosis (32%), followed by lipoma (6%), dermatofibroma or fibroma (4%) and vascular lesion (4%). Malignant diagnoses comprised an additional 36% of the clinical impressions, with non-melanoma skin cancer being the most common of these (19%), followed by lymphoma (6%), metastatic carcinoma (2%) and sarcoma (2%). The correct clinical diagnosis of MCC was made presumptively in only two cases (1%).

Table IV.

Clinician’s Impression of Primary Lesion at the Time of Biopsy‡

| Clinical Diagnosis | No. | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Benign | 79 | 56% |

| Cyst/Acneiform Lesion | 45 | 32% |

| Lipoma | 9 | 6% |

| Dermatofibroma/Fibroma | 6 | 4% |

| Vascular | 5 | 4% |

| Insect Bite | 4 | 3% |

| Other+ | 10 | 7% |

| Malignant | 51 | 36% |

| Non-Melanoma Skin Cancer | 27 | 19% |

| Lymphoma | 9 | 6% |

| Metastatic Carcinoma | 3 | 2% |

| Sarcoma | 3 | 2% |

| MCC | 2 | 1% |

| Other+ | 7 | 5% |

| Indeterminate | 11 | 8% |

| Nodule/Mass | 8 | 6% |

| Other+ | 3 | 2% |

Clinical impression listed in 106 patients with a total of 141 independent presumed diagnoses.

21 patients had 2 presumed diagnoses listed, 6 had 6, and 1 had 4: each was included independently.

Other+

Benign: Pyogenic granuloma, eccrine spiradenoma, scar, neurofibroma, sweets syndrome, “inflammatory”, “benign lesion”

Malignant: melanoma, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. atypical fibroxanthoma, “aplastic lesion”

Indeterminate: appendageal tumor, neural tumor, lymphocytic infiltrate

The five most common clinical features were used to create an acronym: AEIOU (Asymptomatic/lack of tenderness, Expanding rapidly ( ≤ 3 months), Immunosuppression, Older than age 50, and location on a UV-exposed site (Table V)). All five of these data points were known in 62 patients. Eighty-nine percent of patients met 3 or more criteria, 52% met 4 or more criteria and 7% met all 5 criteria.

Table V.

AEIOU Features of MCC

| AEIOU Parameter | No. | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Asymptomatic | 78/79 | 88% |

| Expanding Rapidly | 57/91 | 63% |

| Immune Suppressed | 15/193 | 7.8%‡ |

| Older than Age 50 | 157/195 | 90% |

| UV exposed | 136/168 | 81% |

| Fair Skin | 191/165 | 98% |

| Criteria Met by MCC | ||

| Primary Lesions* | ||

| ≥ 3 criteria | 55 | 89% |

| ≥ 4 criteria | 20 | 32% |

| 5 criteria | 4 | 7% |

16-fold over-representation of immunosuppression

N=62 for which all five criteria are known

Discussion

This study of 195 patients was conducted to identify key features of MCC that may aid clinicians in recognizing when a biopsy may be warranted. The basic demographic profile of our cohort is similar to that described in other studies: mostly elderly, Caucasian and with a slight male predominance.

The anatomic distribution of the tumors seen in our study further supports sun-exposure as a risk factor for the development of MCC, consistent with prior studies. Agelli et al. used SEER Registry data to demonstrate a positive association between geographic UV-B radiation indices and age-adjusted MCC incidence among White patients in a variety of US cities3. In patients receiving PUVA (psoralen + UV-A) for psoriasis, Lunder and Stern reported the incidence of MCC to be approximately 100 times that expected in the general population14. In our series, 81% of cases presented on UV-exposed skin. While sun exposure is strongly associated with MCC, as in melanoma, MCC can arise in the absence of significant UV exposure. Importantly, 5% of patients had tumors on highly sun-protected sites (buttock or vulva), and 14% had tumors arise on partially protected sites (abdomen, thighs and hair-bearing scalp).

Profound immunosuppression also appears to be an important risk factor for MCC. Indeed, 7.8% of our patients had some form of immunosuppression, including HIV, CLL, or iatrogenic suppression secondary to solid organ transplantation. This frequency is a 16-fold over-representation of that expected in the general US population, in which the estimated prevalences are 0.4% for HIV15, 0.029% for CLL11, 12, and 0.075%12, 13 for solid organ transplantation.

An association of MCC with HIV and solid organ transplantation is documented in the literature. Miller et al. reported a roughly ten-fold increase in MCC after solid organ transplantation16, and Engels found a 13-fold increase among HIV-positive patients17. Further highlighting the importance of immune function in MCC, Friedlaender et al. described regression of MCC metastases after discontinuation of cyclosporine in a kidney transplant patient18.

Among our immunosuppressed patients, CLL was particularly over-represented (4.1%). The age-adjusted incidence of CLL in our cohort was 2.4% for 50–69 year olds and and 6.5% for ≤ 70 year olds, representing a respective 48-fold and 34-fold increase above that expected in the US population for those age groups. MCC arising in the setting of CLL has been described19–23, but to the best of our knowledge, this is the first quantitation of the degree to which MCC is over-represented in this disease. We acknowledge the potential for referral bias in our series because immune suppressed patients may be more likely to be seen in tertiary medical centers. However, in 3 of the 15 cases, MCC was diagnosed first, and the immune suppressed state (HIV or CLL) was discovered as part of the MCC workup. This finding also supports the need for practitioners to consider further workup for immunosuppression in patients presenting with MCC.

In agreement with a prior study of transplant patients, we observed more advanced disease at time of presentation in the immunosuppressed group; ten of the fifteen (67%) immunocompromised patients presented with either nodal or distant metastatic disease as compared to 42% in the immunocompetent group (difference not statistically significant). In contrast to reports of organ transplant recipients and HIV positive patients developing MCC at an earlier age17, 24, 25, we did not find a difference in the mean ages of immunosuppressed and immunocompetent MCC patients. This likely reflects the inclusion of 8 patients with CLL, a disease with a mean age of 65.

Clinicians thought most lesions were benign prior to biopsy, which may have contributed to a delay in the diagnosis. Although not quantified, many of our patients reported they had been reassured by a physician about the benign nature of their lesion. Indeed, several of the characteristic MCC features were present at that earlier visit. It is hoped that publicizing the clinical characteristics of MCC may result in an earlier diagnosis in some cases.

We identified several tumor characteristics that may aid a clinician in suspecting MCC, summarized as AEIOU (Table V). Of particular note, we consider lack of tenderness an important feature in MCC as many other lesions that are rapidly growing and red or pink (such as an inflamed cyst, the most common presumed diagnosis) would likely be tender.

Here we describe the first systematic analysis of the clinical features of Merkel cell carcinoma. We have identified several characteristics that in combination are highly sensitive for the diagnosis of MCC. While we do not have data to address the specificity of these features, it is likely to be low given the rarity of MCC. Among lesions encountered in routine clinical practice that display multiple of these features, only a few may be MCC while others, such as squamous cell carcinoma or keratoacanthoma, would also have required a biopsy. Thus, the use of these criteria to aid in the decision to perform a biopsy may be appropriate. Given the correlation between survival and stage at presentation1, identifying patients at an earlier and potentially more curable point is highly desirable for Merkel cell carcinoma.

Acknowledgments

We thank those who have donated to the University of Washington Merkel Cell Carcinoma Research Fund. We appreciate the critical review of this manuscript by Stephanie Lee, MD.

Funding sources: Harvard/NCI Skin Cancer SPORE, University of Washington Merkel Cell Carcinoma Research Fund, NIH K02-AR050993, American Cancer Society Jerry Wachter Fund

Abbreviations

- CLL

chronic lymphocytic leukemia

- HIV

Human Immunodeficiency Virus

- MCC

Merkel cell carcinoma

Acronym

- AEIOU

Asymptomatic/lack of tenderness, Expanding rapidly, Immune suppression, Older than age 50, UV-exposed/fair skin

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None

Statement of prior presentation: Selected and limited preliminary descriptive results presented in abstract form at the 2007 Annual Meeting of the Society for Investigative Dermatology, Los Angeles, CA, May 12, 2007.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Allen PJ, Bowne WB, Jaques DP, Brennan MF, Busam K, Coit DG. Merkel cell carcinoma: prognosis and treatment of patients from a single institution. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(10):2300–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hodgson NC. Merkel cell carcinoma: changing incidence trends. J Surg Oncol. 2005;89(1):1–4. doi: 10.1002/jso.20167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agelli M, Clegg LX. Epidemiology of primary Merkel cell carcinoma in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49(5):832–41. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(03)02108-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lemos B, Nghiem P. Merkel cell carcinoma: more deaths but still no pathway to blame. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127(9):2100–3. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goepfert H, Remmler D, Silva E, Wheeler B. Merkel cell carcinoma (endocrine carcinoma of the skin) of the head and neck. Arch Otolaryngol. 1984;110(11):707–12. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1984.00800370009002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gupta SG, Wang LC, Penas PF, Gellenthin M, Lee SJ, Nghiem P. Sentinel lymph node biopsy for evaluation and treatment of patients with Merkel cell carcinoma: The Dana-Farber experience and meta-analysis of the literature. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142(6):685–90. doi: 10.1001/archderm.142.6.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lewis KG, Weinstock MA, Weaver AL, Otley CC. Adjuvant local irradiation for Merkel cell carcinoma. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142(6):693–700. doi: 10.1001/archderm.142.6.693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mojica P, Smith D, Ellenhorn JD. Adjuvant radiation therapy is associated with improved survival in Merkel cell carcinoma of the skin. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(9):1043–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.9319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garneski KM, Nghiem P. Merkel cell carcinoma adjuvant therapy: Current data support radiation but not chemotherapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Worda M, Sreevidya CS, Ananthaswamy HN, Cerroni L, Kerl H, Wolf P. T1796A BRAF mutation is absent in Merkel cell carcinoma. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153(1):229–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06713.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Watkins DN, Berman DM, Baylin SB. Hedgehog signaling: progenitor phenotype in small-cell lung cancer. Cell Cycle. 2003;2(3):196–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Watkins DN, Berman DM, Burkholder SG, Wang B, Beachy PA, Baylin SB. Hedgehog signalling within airway epithelial progenitors and in small-cell lung cancer. Nature. 2003;422(6929):313–7. doi: 10.1038/nature01493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wong DJ, Chang HY. Learning more from microarrays: insights from modules and networks. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;125(2):175–82. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2005.23827.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lunder EJ, Stern RS. Merkel-cell carcinomas in patients treated with methoxsalen and ultraviolet A radiation. N Engl J Med. 1998;339(17):1247–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199810223391715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.UNAIDS/WHO Global HIV/AIDS Online Database. HIV/AIDS estimates, United States of America. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller RW, Rabkin CS. Merkel cell carcinoma and melanoma: etiological similarities and differences. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1999;8(2):153–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Engels EA, Frisch M, Goedert JJ, Biggar RJ, Miller RW. Merkel cell carcinoma and HIV infection. Lancet. 2002;359(9305):497–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07668-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Friedlaender MM, Rubinger D, Rosenbaum E, Amir G, Siguencia E. Temporary regression of Merkel cell carcinoma metastases after cessation of cyclosporine. Transplantation. 2002;73(11):1849–50. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200206150-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barroeta JE, Farkas T. Merkel cell carcinoma and chronic lymphocytic leukemia (collision tumor) of the arm: a diagnosis by fine-needle aspiration biopsy. Diagn Cytopathol. 2007;35(5):293–5. doi: 10.1002/dc.20616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pandey U, Naraynan M, Karnik U, Sinha B. Carcinoma metastasis to unexpected synchronous lymphoproliferative disorder: report of three cases and review of literature. J Clin Pathol. 2003;56(12):970–1. doi: 10.1136/jcp.56.12.970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Papageorgiou KI, Kaniorou-Larai MG. A case report of Merkel cell carcinoma on chronic lymphocytic leukemia: differential diagnosis of coexisting lymphadenopathy and indications for early aggressive treatment. BMC Cancer. 2005;5:106. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-5-106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vlad R, Woodlock TJ. Merkel cell carcinoma after chronic lymphocytic leukemia: case report and literature review. Am J Clin Oncol. 2003;26(6):531–4. doi: 10.1097/01.coc.0000037108.86294.5E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ziprin P, Smith S, Salerno G, Rosin RD. Two cases of merkel cell tumour arising in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142(3):525–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Buell JF, Trofe J, Hanaway MJ, et al. Immunosuppression and Merkel cell cancer. Transplant Proc. 2002;34(5):1780–1. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(02)03065-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Penn I, First MR. Merkel’s cell carcinoma in organ recipients: report of 41 cases. Transplantation. 1999;68(11):1717–21. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199912150-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]