Abstract

Biological rafts were identified and isolated at 37°C and neutral pH. The strategy for isolating rafts utilized membrane tension to generate large domains. For lipid compositions that led only to microscropically unresolvable rafts in lipid bilayers, membrane tension led to the appearance of large, observable rafts. The large rafts converted back to small ones when tension was relieved. Thus, tension reversibly controls raft enlargement. For cells, application of membrane tension resulted in several types of large domains; one class of the domains was identified as rafts. Tension was generated in several ways, and all yielded raft fractions that had essentially the same composition, validating the principle of tension as a means to merge small rafts into large rafts. It was demonstrated that sphingomyelin-rich vesicles do not rise during centrifugation in sucrose gradients because they resist lysis, necessitating that, contrary to current experimental practice, membrane material be placed toward the top of a gradient for raft fractionation. Isolated raft fractions were enriched in a GPI-linked protein, alkaline phosphatase, and were poor in Na+-K+ ATPase. Sphingomyelin and gangliosides were concentrated in rafts, the expected lipid raft composition. Cholesterol, however, was distributed equally between raft and nonraft fractions, contrary to the conventional view.

INTRODUCTION

In recent years, considerable attention has been focused on small (10–200 nm in diameter) domains that form in membranes. Particular proteins are expected to be concentrated into these small domains, providing cells with an important means of regulating protein activity (1). Nanoscale nonuniformities undoubtedly exist because lipid-lipid, lipid-protein, and protein-protein interactions depend on the precise species. Nonuniformities and small domains can thus result, in principle, from condensation of lipids around proteins or from the partitioning of proteins into preformed lipid domains. One class of small domains that is actively being studied is “membrane rafts.” Rafts are thought to be rich in sphingolipids, cholesterol, and specific proteins (2,3); the lipids are in a phase state that is distinct from the surrounding membrane (4). Intense investigations proceed even though technical limitations have made it difficult to demonstrate unambiguously that biological rafts exist (5,6).

The most common procedure to isolate putative rafts is to collect detergent-resistant (i.e., insoluble) membrane fractions at 4°C (7). But the existence of a biochemically isolated fraction (or the identification of a physical phase) at a low temperature does not imply that the fraction (or phase) exists at a higher temperature, and thus, DRMs may not correspond to physiological domains. Other procedures for isolating rafts have been devised, most notably using high pH in lieu of detergents but still employing low temperature (8). There is little question that if rafts do exist in biological membranes, they are small. If small rafts could be forced to merge with each other to become large enough to be visible, methods to reliably isolate them could be developed, and rafts would be more amenable to characterization.

In model lipid bilayer membranes, small domains that have characteristics expected of biological rafts have been identified (9,10). Also, large domains (from micrometers to tens of micrometers in diameter) have been observed by fluorescence microscopy (11,12). In model systems, (SM) is used at a supersaturated concentration, and large domains are created by lowering temperature. The formation of these domains is initiated by nucleation, and domains initially enlarge by accumulating monomers from the surround (13). The domains remain submicroscopic during this growth mechanism. They become optically visible through the merger of smaller domains (14).

If biological rafts could be biochemically isolated under physiological conditions—37°C, neutral pH, and without the use of chemical reagents—the field of cell biology in general could be advanced because means to identify the lipid and protein composition of rafts under resting and activated conditions of cells would be in hand. One means to achieve this is to develop procedures in model bilayer membranes to identify rafts and their composition, procedures that could be directly extended to cellular systems. In model bilayer membranes, application of lateral tension has been shown to promote formation of large domains (15). In this study, we utilized lateral tension to induce merger of small domains into large ones and developed means to isolate large rafts, allowing us to identify the composition of biological rafts.

By osmotically swelling GUVs composed of physiological levels of SM and cholesterol, we generated lateral membrane tension, producing large domains that could be isolated. The procedure was extended, and biological rafts were isolated at physiological temperature (37°C) and neutral pH, in the absence of detergents. We found that these rafts were enriched in a GPI-linked protein and in SM and excluded Na+-K+ ATPase, a nonraft protein (16), all as expected. Contrary to expectations, these rafts were not enriched in cholesterol.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Membrane fractionation and raft isolation

CEMss cells (from three 100-mm dishes) were suspended in ice-cold PBS. Cells were washed in an ice-cold homogenizing buffer (400 mM sucrose, 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.3) and then resuspended in the same buffer and warmed to 37°C before douncing with 25 strokes in a Duall-style homogenizer (a protease inhibitor cocktail (10 μl/ml, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was included to prevent proteolysis). The homogenate was centrifuged for 10 min at ∼1000 × g, and the supernatant was collected. This material is denoted “D” for dounce (see Figs. 7 and 8). For experiments in which swollen cells were required, the cells were treated similarly as above, but they were washed in 250 mM (instead of 400 mM) sucrose and then brought to 37°C in a swelling buffer of 125 mM sucrose, 10 Tris-HCl, pH 7.3, for 15 min. After douncing and removal of debris, the supernatant was collected, and the sucrose was adjusted to 400 mM. This material is denoted “SD” for swelling followed by douncing (see Figs. 7 and 8). For experiments in which domains were induced to pinch off, cells were swollen in the above 125 mM sucrose solution and the domains sloughed off the cells by gentle vortexing for 1 min in the presence of 50 mg of PTFE powder (particle size 12 μm, Sigma-Aldrich). Cells were then spun down, the supernatant (which contains the pinched-off vesicles) was collected, and the sucrose concentration was adjusted to 400 mM (with Tris-HCl, pH 7.3). This material is denoted “S” for swelling.

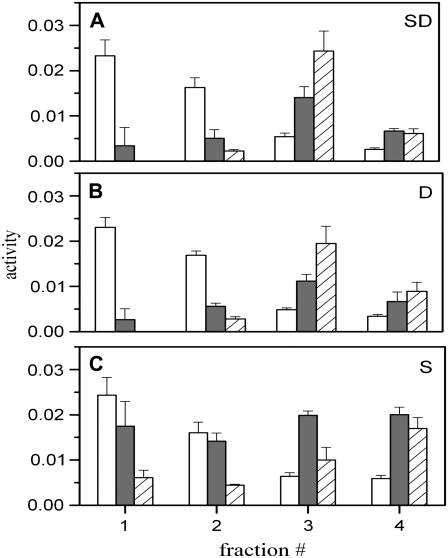

FIGURE 7.

Segregation of raft and nonraft proteins. The activity of alkaline phosphatase (open bars), alkaline diesterase (solid bars), and Na+-K+ ATPase (striped bars) in separated fractions were measured after various means of generating tension in cells. (A) Cells were swollen and then dounced (SD). (B) Cells were only dounced (D). (C) Cells were swollen and membrane domains gently sheared off (S). All activities are shown in arbitrary units.

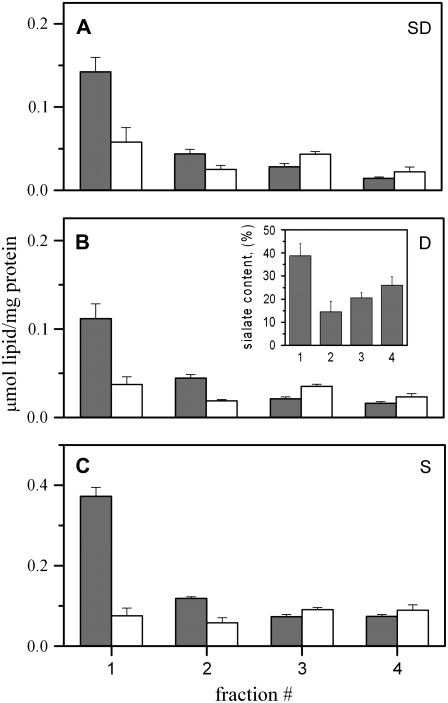

FIGURE 8.

SM and cholesterol content of isolated membrane fractions. A, B, and C are the SM and cholesterol content of each fraction of Fig. 7, normalized to its protein content. Although the normalized cholesterol concentration was the same for all fractions, we cannot unambiguously conclude that the cholesterol concentration is the same in all the fractions because protein levels are different in the various fractions. However, because both SM and cholesterol are both normalized to protein, we can be certain that SM is highly enriched in the lightest fraction relative to cholesterol. The inset in B shows the percentage of the total sialate content within each of the four fractions.

Membrane fractions were separated on a step sucrose gradient consisting of 1.6 M, 1.4 M, 1.2 M, and 0.8 M sucrose in 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.3 (1.5 ml for each step); 4 ml of a membrane preparation (in 400 mM sucrose) was layered on top of the four steps; and the tube was topped by 2 ml of 0.125 M sucrose. After a 35,000 rpm centrifugation in a SW 41 Beckman rotor for 3–4 h, bands of material were clearly visible at all interfaces. The materials at the 0.125/0.4 M, 0.4/0.8 M, 0.8/1.2 M, and 1.2/1.4 M interfaces were collected. The lower interfaces also contained material, but we did not analyze them because they are contaminated with cellular debris and heavy microsomal fractions.

Liposome flotation

All lipids and fluorescently labeled probes were used as obtained (Avanti Polar Lipids, Alabaster, AL). SUVs were prepared at 60°C in 0.5 M sucrose solution containing 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.3, by extrusion through a 100-nm-pore polycarbonate filters (LiposoFast extruder, Avestin, Ottawa, Canada). We separately made SUVs from SM/cholesterol with NBD-DPPE (1%) and 2/1 DOPC/cholesterol with Rho-DOPE (1%) and mixed these two SUV preparations together. After adjusting the external sucrose concentration to 1.7 M, we layered the liposomes at the bottom of a step gradient composed of 0.125, 0.25, 0.4, 0.8, and 1.2 M sucrose steps (10.5 ml total volume). After a 33,000 rpm centrifugation in an SW 41 Ti rotor for 2.5 h, 10 1-ml fractions were collected. The NBD and rhodamine fluorescence content of each fraction was measured with a plate reader (Victor3V, Model 1420, Perkin Elmer, Foster City, CA). Although the intrinsic density of lipid is less than that of water, neither set of SUVs floated to the very top of the gradient. But the DOPC/cholesterol vesicles (see Fig. 6 A, open bars) did rise to a higher interface than those composed of SM/cholesterol (solid bars). We also treated the combined suspension of DOPC/cholesterol and SM/cholesterol liposomes with 0.5% Triton X-100 at 4°C and subjected the resulting sample to the same centrifugation procedure described above. DOPC/cholesterol liposomes were completely dissolved by the detergent; the detergent did not affect the flotation of the SM/cholesterol liposomes (see Fig. 6 B).

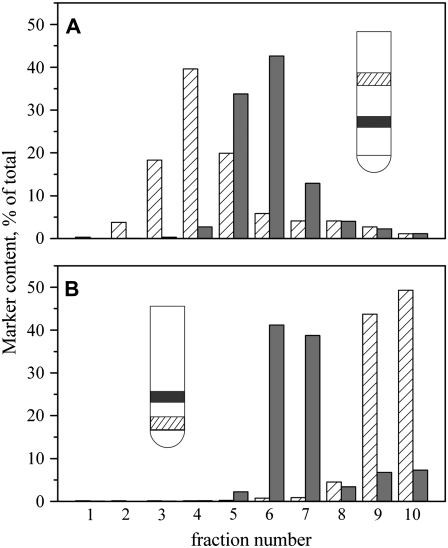

FIGURE 6.

(A) High SM content retards liposome flotation in sucrose gradients. DOPC/cholesterol liposomes 100 nm in diameter labeled by Rho-DOPE and SM/cholesterol liposomes labeled with NBD-DPPE were placed at the bottom of a sucrose gradient and allowed to come to their equilibrium positions by high-speed centrifugation. Results of a typical experiment are shown. (A) The SM-rich liposomes (solid bars) were distributed to higher densities (lower in the illustrated centrifuge tube and higher fraction number in the histogram) than the DOPC-rich liposomes (striped bars in illustrated test tube and histogram). (B) Triton X-100-treated SM/cholesterol liposomes. SM/cholesterol liposomes treated with 0.5% Triton X-100 at 4°C. In flotation experiments, preparations that were not treated with Triton (A) were concentrated at the same interface as those that were treated (B), as illustrated by the same position of the solid bar within the test tubes of panels A and B. In collecting 1-ml fractions, the relative NBD-DOPE contents (solid bars) were within one fraction of each other in panels A and B, showing that the distribution was not affected by Triton X-100. The material of DOPC/cholesterol liposomes (striped bars) remained at the position they were placed, showing that these liposomes were completely dissolved by 0.5% Triton X-100: dissolved material does not migrate during centrifugation.

Protein and lipid and assays

The activities of alkaline phosphatase (16) and Na+-K+ ATPase (17) were measured, with minor modifications, as described. Alkaline phosphodiesterase was measured using bis-(p-nitrophenyl) phosphate as a substrate, following the supplier's instructions (Sigma).

SM content was quantified by a previously described strategy (18) using an Amplex Red reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). We used a standard cholesterol oxidase-based kit to quantify the cholesterol content of membrane fractions (Invitrogen). However, we found that the cholesterol contents of SM-rich membrane fractions and SM-rich liposomes were seriously underestimated by this standard assay (see Supplementary Fig. 1 and legend). Even the presence of the small amount of detergent normally used in this assay did not render all cholesterol accessible to the oxidase. Cholesterol was accurately measured with the kit for liposomes that were not rich in SM. We solved the assay problem by sequentially partitioning cholesterol (and other nonpolar lipids) into chloroform/methanol (2:1) and then into hexane. The partitioned lipids were combined with an excess of DOPC, and liposomes were formed. A mixture of 70% DOPC and 30% cholesterol was used to obtain a standard curve for cholesterol content.

To estimate the ganglioside content of each membrane fraction, we deproteinated each fraction to obtain a total lipid extract (19). The sialic acids were liberated from the gangliosides by sialidase hydrolysis and then derivatized (20). The amount of the resulting fluorescent product was measured at 350/460-nm excitation/emission wavelengths using a plate reader. Protein content was quantified using a Pierce Micro BCA Protein Assay Kit after removing substances that would interfere with the assay (21).

Microscopy

GUVs were prepared in sucrose as previously described (22). For microscopy, GUVs were added to a glucose solution within a chamber mounted on the stage of a fluorescence microscope. The antioxidant n-propyl gallate (1 mM) was included in the solution to prevent photooxidation (22). Because the antioxidant can interact with membranes, it could shift temperatures of phase transitions by a few degrees Celsius. But we performed our microscopy experiments well below transition temperatures, and so any such shifts would not affect our findings. GUVs rapidly settled to the bottom of the chamber and were observed with a long-working-distance 63× immersion oil objective (NA 1.2, Zeiss, Jena, Germany) attached to a Nikon Diaphot inverting microscope. To generate tension in GUV membranes, the tonicity of the external glucose solution was usually adjusted to 80–90% of that of the internal sucrose solution.

Pelleted CEMss cells were suspended in PBS++ in the presence of 20 μg/ml BODIPY-FL-ouabain (Invitrogen). After 7 min at 37°C, cells were pelleted and resuspended in ouabain-free PBS++ containing 20 μg/ml AlexaFluoro555 cholera toxin subunit B. (Bound ouabain does not dissociate from ATPase on the time scale of our experiments (23).) For microscopic observations, these fluorescently labeled cells were transferred into a chamber filled with 250 mM sucrose or, when swelling was desired, into a 125 mM sucrose solution. In both cases, 0.5 mM n-propyl gallate was included in the solutions. Images of cells and GUVs were captured with a cooled charge-coupled device camera (model DV 437 BV, Andor Technology, Belfast, UK) and stored to hard disk for later analysis. All microscopy images are shown as stored to disk, without any further processing or enhancements.

Fluorimetry

SUVs were prepared in an aqueous buffer consisting of 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 50 mM Tris, pH 7.3, using a standard extrusion procedure (24). In brief, a dry lipid film adsorbed to the walls of a tube was hydrated in the buffer for 40 min at 65°C, and the tube was then extensively vortexed. This yielded a suspension of multilamellar liposomes that was passed (at 65°C) through a LiposoFast extruder (Avestin, Ottawa, Canada) fitted with a stack of two polycarbonate, 100-nm-pore filters. The resulting SUV suspension was diluted with buffer for fluorimetry measurements (Model LS50B, Perkin-Elmer) in a thermostated cuvette. Fluorescence was excited at 480 nm, and emission was set to 550 nm; the optical slit was 10 nm for excitation and emission. The cuvette temperature was routinely lowered from 58°C or greater to 20°C at a rate of ∼1–2°C/min, while fluorescence was continuously monitored. Three lipid compositions were employed for these experiments: 1), 20% 16:0 SM, 40% cholesterol, 34.9% DOPC, 5% Rho-DOPE, 0.1% NBD-DPPE; 2), 20% egg SM (eSM), 40% cholesterol, 34.9% DOPC, 5% Rho-DOPE, 0.1% NBD-DPPE; 3), 40% cholesterol, 54.9% DOPC, 5% Rho-DOPE, 0.1% NBD-DPPE.

RESULTS

Microscopically visible rafts readily form in GUVs under lateral tension

We prepared GUVs at 65°C from a lipid mixture composed of 20% eSM, 40% cholesterol, and 36% DOPC, and included NBD-DPPE (3%) and Rho-DOPE (1%) as fluorescent lipid probes. NBD-DPPE preferentially partitions into liquid-ordered (lo) rafts (25), whereas Rho-DOPE preferentially partitions into the liquid-disordered (ld) phase that surrounds the rafts (14). Temperature was lowered to 25°C, which is well below the melting temperature of the predominant species of eSM (41°C for 16:0 SM). Phase separation into microscopically observable domains does not occur for this lipid mixture as long as photooxidation of membrane lipids is prevented. If, however, photooxidation is not prevented, phase separation is observed (22). In all our experiments, care was taken to prevent photooxidation.

We osmotically swelled GUVs to generate membrane tension and observed that micrometer-sized domains emerged quickly (Fig. 1). The time before the appearance of domains was on the order of seconds, and this time was probably limited by the time it took for the hypoosmotic solution to replace the initial external solution that locally surrounded the GUVs. An internal hydrostatic pressure of a liposome will create lateral membrane tension. The relation between pressure and tension is quantitatively described by the Laplace relation, P = 2T/R where P is the internal hydrostatic pressure, T is membrane tension, and R is the liposome radius. When the membrane tension exceeds its rupture limit, ∼5–10 dyne/cm (27), lipidic pores form in the membrane; this process is commonly referred to as lysis, bursting, or rupture. The radii of GUVs are large, many microns, and so it is virtually certain that the GUVs lyse for relatively small osmotic gradients: the tension that a GUV membrane would have to withstand is orders of magnitude higher than the rupture limit. For our lipid composition, a lipidic pore should reseal because the spontaneous monolayer curvatures conferred by the lipids are not positive enough for the pore to remain open (28). (Below, we provide experimental evidence that these bilayers do, in fact, reseal.) At equilibrium, the osmotic difference between the inside and outside of the GUV is very small, and the GUV supports a membrane tension that is below the rupture limit.

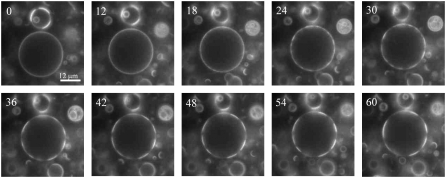

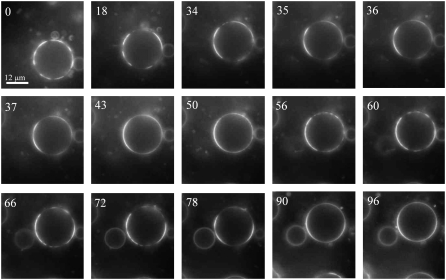

FIGURE 1.

Tension promotes large rafts in GUVs. GUVs in suspension composed of eSM/cholesterol/DOPC 1/2/2 and containing 1% Rho-DOPE and 3% NBD-DPPE as probes exhibited uniform fluorescence in isotonic 200 mM sucrose (not shown). When these GUVs were added to an external solution of 180 mM glucose, they settled, and the progression of raft formation was followed over time in the largest of the GUVs in the field of view. Times after addition of GUVs to the hypoosmotic solution are shown in seconds in each panel. Smaller rafts consolidate into larger rafts on the surface of the GUV over time. Fluorescence is shown for NBD-DPPE.

Small domains are present in the absence of lateral tension

We previously provided evidence that for the above lipid composition, small domains are present (22). This article presents additional and stronger evidence that small domains are present. We prepared unilamellar liposomes of ∼100 nm diameter from 20% 16:0 SM, 40% cholesterol, 34.9% DOPC%, 0.1% NBD-DPPE, and 5% Rho-DOPE and spectrofluometrically monitored the emission of NBD on lowering temperature from 58°C. (The term “liposomes” is used here to refer to artificial systems, and “vesicles” refers to material obtained from cell membranes.) We employed the following logic: In the absence of domains, the two fluorescent probes randomly distribute. As liquid-ordered domains form, the NBD-DPPE should preferentially partition into them. NBD fluorescence should increase because it is then not quenched by Rho-DOPE which preferentially resides in the surrounding liquid-disordered membrane phase. Experimentally, NBD fluorescence was relatively constant as temperature was lowered from 58°C to 40°C (Fig. 2, triangles). There was a distinct increase in the fluorescence at 40–45°C, which continued to increase with a constant temperature dependence when temperature was continuously lowered to 20°C. Clearly, NBD-DPPE became physically separated from Rho-DOPE when temperature was lowered from ∼40°C.

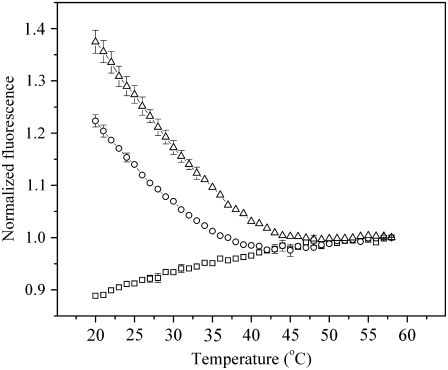

FIGURE 2.

Fluorimetric detection of formation of rafts on lowering of the temperature. Temperature was lowered from 58°C to 20°C, and the fluorescence of SUVs containing 0.1% NBD-DPPE was followed; 5% Rho-DOPE was included in the SUVs to quench NBD fluorescence. The fluorescence of SUVs composed of (in addition to the probes) either 20% 16:0 SM, 40% cholesterol, 34.9% DOPC (triangles) or 20% eSM, 40% cholesterol, 34.9% DOPC (circles) increased at 40–45°C, and the increase continued as temperature was lowered further. The increase in fluorescence indicates phase separation. The fluorescence of SUVs composed of 40% cholesterol and 54.9% DOPC never increased as temperature was lowered (squares). An absence of an error bar means that the bar is smaller that the size of the symbol. Error bars are SE, n = 3.

As a control, we performed the same experiments but used a 40% cholesterol, 54.9% DOPC lipid mixture so that phase separation would not be expected. The fluorescence of NBD-DPPE did not increase over any of the temperature range that was scanned. This shows that the increase in fluorescence observed for DOPC/SM/cholesterol bilayers was caused by phase separation and not by anomalous properties of the probes. In fact, fluorescence of the cholesterol/DOPC bilayers decreased somewhat as temperature was lowered (Fig. 2, squares). The decrease could reflect a number of processes: for instance, it could indicate that temperature-dependent lipid interactions affect the environment of the probes enough to be detected fluorimetrically or that transient NBD-DPPE clusters form (leading to a time-averaged self-quenching), and this clustering is greater at lower temperature. We also used eSM in lieu of 16:0 SM and performed the identical experiments (Fig. 2, circles). Temperature dependence manifested itself below ∼40°C, the same temperature as for 16:0 SM. However, the increase in fluorescence on lowering temperature was less, showing that NBD-DPPE segregates from Rho-DOPE to a smaller degree for eSM than for 16:0 SM. This difference must occur because eSM is somewhat heterogeneous, containing small amounts of longer-chained SMs, including 18:0, 20:0, 22:0, and 24:0 SM (catalog, Avanti Polar Lipids), that have higher melting temperatures. But specific molecular mechanisms that cause the differences in fluorescence have yet to be determined. Several groups have shown that for somewhat different lipid compositions as well, small nanoscopic domains can form and remain small, without enlarging (9,10). To be certain that the liposomes were at equilibrium for all temperatures in the fluorimetry experiments, we raised the temperature from 20 to 60°C and then lowered it back to 20°C. At every temperature, the fluorescence was independent of the direction of changing temperature (data not shown). We conclude that the large domains observed in GUVs in the presence of lateral membrane tension result from merger of visually unobservable small domains that were present in the absence of tension. Lateral tension does not create domains from a previously homogeneous membrane.

Lateral tension promotes large raft formation for thermodynamic, not kinetic, reasons

We performed experiments to test whether large raft formation was reversibly controlled by lateral tension. When a liposome ruptures, the internal pressure is relieved, and membrane tension is eliminated; water and solute flow through the pore, reducing the osmotic gradient. If membrane tension reversibly controls large raft formation, the relief of tension should cause the large rafts to disperse into small ones. When GUVs were swollen, the large rafts that formed had visually sharp boundaries. The boundaries then blurred over the time course of a few seconds, appearing to be spread out, but the central area remained bright (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Video 1; NBD-DPPE is shown for this figure and video clip, and so rafts are bright; blurring occurred by time = 35 s). The persistence of this central bright area is expected after a large raft disperses into many small domains because each domain is now smaller than optical resolution and so one overall grouping is observed. We interpret the blurring visible at the edge to be the result of slow diffusion of the small rafts. Some liposomes clearly displayed shrinkage at the time of blurring, whereas others did not. For those that did, we could be certain that the blurring was caused by relief of tension because blurring correlated in time with liposome shrinkage (Fig. 4 B). Shrinkage was observed as a small, but definite, reduction in liposome diameter (Fig. 4 A). Additional evidence for correlation between liposome rupture and blurring at the edge was the observation that some GUVs that exhibited large rafts moved over a distance of a few micrometers as raft boundaries simultaneously blurred (Supplementary Video 1). Most likely, on formation of a lipidic pore, the pressure was suddenly dissipated by expulsion of water through the pore, causing propulsion of the GUV in the opposite direction. In these cases, movement and dispersal of a large raft correlated in time. If the blurring is a result of dispersal of a large raft into small ones, large raft formation is certainly reversible.

FIGURE 3.

Large raft formation is reversible. Conditions were as in Fig. 1. Large rafts had already formed at the start of observing GUVs after they were placed in the hypotonic external solution. The sharp boundaries blurred in frames between 34 and 35 s. At 56 s, sharp boundaries once again formed. At 78 s, edges of rafts have blurred and remained blurred beyond 96 s, and eventually sharpened again (steady-state, not shown). NBD-DPPE was included in the GUVs to mark rafts as bright domains.

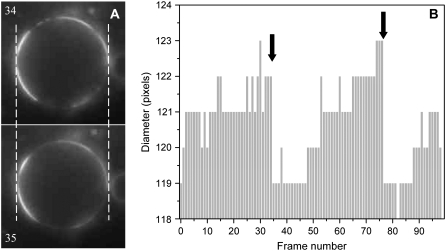

FIGURE 4.

(A) Blurring of raft boundaries occurs simultaneously with liposome shrinkage. The GUV of Fig. 3 is shown at 34 and 35 s. Raft boundaries are distinct at 34 s but diffuse at 35 s. The GUV diameter is slightly but discernibly less at 35 s than at 34 s, a difference of ∼1 μm. The most plausible explanation is that GUV rupture (i.e., formation of a lipid pore) occurred at this point; the collapse of tension caused the large rafts to break up into many small rafts, although the diffusion of all of them is observable only at the blurred boundary. (B) The diameter of the GUV (0.2 μm/pixel) is shown as a function of frame number (1 s/frame). The moments of edge blurring are marked by bold, vertical arrows. Shrinkage is observed as a sudden descrease of several pixels in GUV diameter. Reswelling is observed as stepwise increases in diameter. The momentary (one or two frames) fluctuations of one pixel in height result from the limitation of optical resolution, which corresponds to one pixel. The overall pattern of shrinkage and swelling is as expected: GUV shrinkage occurred rapidly (within one frame) and correlated in time with edge blurring (arrows). The increase in GUV diameter was slow, consistent with the time for water to enter a giant liposome. For this GUV, shrinkage occurred twice, each time followed by swelling. Each of the two blurrings (arrows) occurred at the instant of shrinkage.

If a large raft were to disperse, the resulting small rafts would continuously diffuse. This would be observed as a further and gradual spreading of the boundary of the grouped small rafts. This was indeed the observed pattern (Fig. 3). The boundary could then be seen to sharpen, and new bright regions with a sharp edge could appear (Fig. 3, time = 56 s). The sequence of smearing of the boundary followed by sharpening and formation of large rafts at new locations could repeat itself (Fig. 3, blurring at time = 78 s). At steady state, boundaries were sharp. In short, for some liposomes there was a repetitive pattern of blurring and sharpening of raft edges, and in these cases shrinkage was rapid and occurred at the same time as the blurring (Fig. 4 B). The rapid shrinkage is consistent with membrane rupture, and the slow time course of tens of seconds for the GUV to swell to its former size would correspond to the time it takes for enough water to enter and swell the GUV to its former volume (and for any pores to reseal). We surmise that GUV swelling and membrane rupture were followed by resealing of pores. After pore resealing, water movement caused a hydrostatic pressure to build. The membrane tension generated promoted merger of small rafts into large ones. A liposome would again rupture if the lytic limit was exceeded. This process repeats itself until a pressure below the lytic limit is reached, the state at equilibrium, with domains exhibiting a sharp edge. In other words, a nonzero membrane tension is present at equilibrium, and large rafts have become stable.

The finding that large rafts form with sharp boundaries followed by blurring, which then can repeat itself several times, is strong evidence that lateral tension can very rapidly induce the formation of large domains and that large raft formation is reversibly controlled by lateral tension. We conclude that the merger of small rafts into observable large ones, and their dissolution is reversibly under the control of lateral tension. Importantly, if large raft formation is reversible, it follows that such formation is determined thermodynamically rather than kinetically. If small rafts do not merge into large ones, it is not a kinetic barrier that keeps them apart. Rather, they are thermodynamically favored to remain separate.

Osmotic swelling of cells causes the formation of large domains

Having verified that lateral tension causes nanoscopic domains to merge into micrometer-sized domains in liposomes, we tested whether this is the case for plasma membranes of cultured cells as well. We selected CEMss cells, a lymphocyte cell line, for these tests because they do not express caveolin (29). This eliminates the possibility that any large domains that might be promoted by tension are caveolae. (Nomenclature is not uniform throughout the literature. Some investigators refer to all sphingolipid- and cholesterol-rich domains as rafts, whether or not they contain caveolae. We exclude caveolae when we refer to rafts.) Fluorescently labeled (with AlexaFluor555) β-subunit of cholera toxin binds GM1, and this probe was used to mark rafts (30). Fluorescently labeled (by BODIPY-FL) ouabain was used to locate Na+-K+ ATPase, which is generally thought to be a nonraft protein (16). The cell surfaces were uniformly stained by both the GM1 and ATPase probes (Fig. 5, A1 and B1).

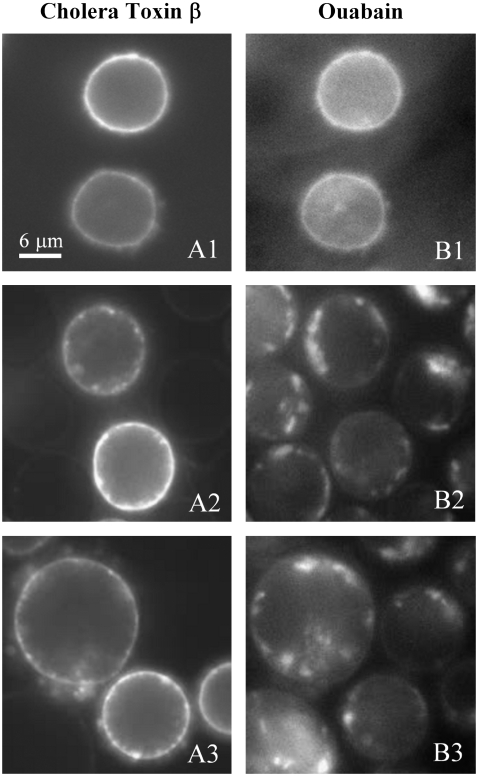

FIGURE 5.

Swelling induces large rafts in cells at 37°C. Fluorescently labeled β-subunit of cholera toxin was used to bind GM1 to mark rafts (A1, A2, and A3), and fluorescently labeled ouabain was used to bind Na+-K+ ATPase (B1, B2, and B3) to identify nonraft domains. Both probes distribute uniformly across nonswollen cells (A1 and B1). A1 and B1 are the same cells shown for the two probes. Panels 2 and 3 are different cells than panel 1, but are paired A and B. Panels 2 and 3 show cells ∼30 min after swelling. Both probes have clustered into large domains of different sizes that do not overlap with each other.

To generate tension, CEMss cells were swollen at 37°C by being placed in a sucrose solution of half tonicity. Because some of the cholera toxin subunit would have been internalized by the cells during the incubation time of swelling (data not shown), it was not added until just before microscopic observation. Ouabain was added just before cell swelling because it binds with high affinity only to phosphorylated Na+-K+ ATPase (31). After the cells were in the hypotonic medium for ∼1 min, irregularities in fluorescence from the cholera toxin subunit began to appear; distinct domains developed within ∼5 min of cell swelling. After 10–15 min, cells were more rounded, and the fluorescent cholera toxin subunit showed micrometer-sized domains. But the fluorescent ouabain had not yet unambiguously sequestered into domains. After ∼30 min of swelling, however, there were clear and profound changes in the distribution of the ouabain probe (Fig. 5, B2 and B3), showing that the Na+-K+ ATPase was now concentrated in large domains. Although the BODIPY-ouabain-labeled domains took longer to form than the GM1-enriched domains, they were larger at the 30-min point. The GM1-enriched (Fig. 5, A2 and A3) and ATPase-enriched domains (Fig. 5, B2 and B3) did not overlap (Fig. 5, A2 and B2, are the same cells ∼30 min after swelling; Fig. 5, A3 and B3, are another set of cells ∼30 min after swelling) but rather were separated, micrometers apart, by regions that were depleted of both dyes. The addition of ouabain to label the Na+-K+ ATPase should also cause cell swelling because it blocks these pumps, crucial in volume control. This cell swelling in saline was, however, more modest than that in the hypotonic solution. The cells also swelled in an isotonic sucrose solution (32), and this too led to the appearance of large domains, but over a considerably longer time period. In short, GM1 and the ATPase accumulated within distinct domains. This shows that osmotic swelling induces the formation of different types of large membrane domains in cells, including GM1-enriched raft domains. Thus, cell swelling can be used to enlarge rafts for purposes of characterization.

It was possible that osmotic swelling did not induce large rafts by creating tension but by disrupting the cytoskeleton and that the intact cytoskeleton was preventing rafts from meeting each other and merging. In control experiments, we added cytocholasin D to the cells; we could be certain that this disrupted the cytoskeleton because we observed morphological changes in the cells. But the addition of cytocholasin did not lead to the appearance of large rafts. When these cells swelled, large domains formed. In separate control experiments, we swelled cells at 4°C. This led to large domains in a manner similar to that described for swelling at 37°C. We conclude that swelling is mechanistically exerting its effect by generating lateral membrane tension. Because GM1 marked by cholera toxin subunit clustered into detectable domains after just 1 min of swelling, we further conclude that lateral tension induces small rafts to merge into large ones in a relatively short time.

Vesicles that are formed from large rafts do not migrate as expected during centrifugation

To date, rafts have typically been isolated using some combination of detergents or alkaline pH at low temperature. The temperature employed to isolate rafts is particularly important because a phase (e.g., ice) present at low temperature need not exist at higher temperature. We have used membrane tension to isolate rafts at 37°C without resorting to detergents, high pH, or chemical reagents. We performed all our manipulations at the physiological temperature of 37°C to be certain that low temperature did not cause phase separations. (We took care to prevent proteolysis.) We swelled cells to create large ( 1 μm) domains and then disrupted the cells by douncing. We removed nuclei and cellular debris, layered the remaining membrane material on a sucrose gradient, and collected the various fractions. After swelling, the domains are large, and many small (∼30–100 nm diameter) vesicles should be created solely from a single large domain during douncing. Swelling followed by douncing should thus yield a population of vesicles that is composed of only raft membranes. Other vesicle populations should be composed solely of membranes from domains that are not rafts, and still other populations should contain an assortment of membranes that are not composed of distinct domains.

1 μm) domains and then disrupted the cells by douncing. We removed nuclei and cellular debris, layered the remaining membrane material on a sucrose gradient, and collected the various fractions. After swelling, the domains are large, and many small (∼30–100 nm diameter) vesicles should be created solely from a single large domain during douncing. Swelling followed by douncing should thus yield a population of vesicles that is composed of only raft membranes. Other vesicle populations should be composed solely of membranes from domains that are not rafts, and still other populations should contain an assortment of membranes that are not composed of distinct domains.

Alkaline phosphatase, a GPI-linked membrane enzyme, was used as our protein raft marker, and Na+-K+ ATPase and alkaline diesterase, transmembrane proteins, were used as nonraft markers. Alkaline phosphatase is found in DRMs (33,34), whereas the ATPase (35,36) and alkaline diesterase are not (37). (It is universally agreed that alkaline phosphatase preferentially resides in rafts. There is, however, dispute in the literature as to whether Na+-K+ ATPase is largely excluded from rafts (38). Our microscopy experiments (Fig. 5) strongly support the claim that Na+-K+ ATPase is not a resident of rafts.) Initially standard procedure was followed, loading membrane material next to the bottom (1.4 M sucrose) portion of the gradient. As is well known, DRMs float to the top of a step gradient, and we thus expected the raft vesicles also to do so. The Na+-K+ ATPase was concentrated at an average sucrose concentration of 1 M, precisely as found by others (17). But surprisingly, an appreciable fraction of the alkaline phosphatase (the raft marker) remained at the interface between the gradient concentration in which the material was loaded and the one immediately above it, as had been reported in older, preraft literature (39). (This localization was the case even when we extended centrifugation to 16 h.) This result leads to two possibilities: 1), The membranes composed of raft domains are not, in fact, lighter than membranes composed of nonraft portions of plasma membranes, as had been thought; or 2), the internal solution of raft-containing vesicles does not equilibrate with the external sucrose solutions. If the second possibility is correct, the vesicles will not rise independent of membrane densities. We realized that the second possibility was viable because of the requirements on water movement if vesicles were to migrate upward in a gradient of decreasing sucrose: In moving upward, water must enter vesicles at each step of the gradient to maintain zero difference in tonicity between the interior and exterior of the vesicles; the vesicles must lyse if water is to continue to enter. But if the vesicular membrane can withstand sufficiently large hydrostatic pressures, pressure would build and prevent water entry. The inability of water to enter and dilute the internal sucrose content would lead to heavy vesicles even if the membrane were of low density. That is, vesicles must be able to burst if they are to rise in a sucrose gradient. If vesicles do burst, they will rise to the density set by their membranes, independent of whether they reseal. We know that SM greatly increases the tension that a membrane can withstand before lysing (E. Evans, Boston University, personal communication, 2007). It follows that the SM content of a vesicle membrane may significantly affect the vesicle equilibrium position because of its ability to withstand tension rather than as a consequence of membrane density. We tested whether high SM content of vesicles does affect vesicle ability to float in a gradient.

Liposomes do not migrate during centrifugation according to the density of their membranes

To explicitly control SM content for vesicle floatation experiments, we prepared artificial liposomes. We used a standard extrusion procedure to make 100-nm-diameter liposomes from two different lipid mixes. One contained a high level of SM, 2:1 SM/cholesterol mole ratio with NBD-DPPE (1%) as a marker, and the other was free of SM, 2:1 DOPC/cholesterol with Rho-DOPE (1%) as the marker. The two different liposome preparations, each made in 0.5 M sucrose, were mixed, and external sucrose was adjusted to 1.5 M. This suspension was layered on the bottom of a sucrose gradient consisting of 0.2, 0.4, 0.8, and 1.2 M sucrose (10.5 ml total volume). After a spin, 10 1-ml fractions were collected (in the order 1–10, top to bottom), and the amount of each fluorescent label was measured to quantify the amount of liposomes containing high SM and devoid of SM (Fig. 6 A). Although the density of a lipid is less than that of water, liposomes did not float to the very top of the gradient, independent of lipid composition. (Equilibrium positions were achieved within 1–2 h; long, 12- to 16-h runs resulted in more continuous gradients, but the positions of the liposomes were not significantly altered.) But the DOPC/cholesterol liposomes (Fig. 6 A, striped bars) rose much more than the SM/cholesterol (solid bars) liposomes. Clearly, high-SM-content liposomes have a significantly higher equilibrium density in a sucrose gradient than do liposomes devoid of SM. These experiments convincingly demonstrate that the relatively small liposomes that contain high levels of SM do not appreciably rise. The most likely explanation, by far, is that SM stabilizes liposomes against rupture by osmotic lysis. In these liposome floatation experiments, we did not explore the amounts of SM or cholesterol necessary for the liposomes to resist lysis. We have, however, experimentally demonstrated the principle that lysis is required for liposome and vesicle floatation. As a practical matter, the experiments using liposomes demonstrate that if one wants to separate vesicles formed from plasma membranes rich in SM from those that are not, the preparation should be loaded toward the top rather than the bottom of a gradient. This is opposite to the current accepted procedure.

We tested the effect of Triton X-100 on liposome flotation (Fig. 6 B) because this detergent is often used to isolate DRMs. Both the SM-containing and SM-free liposomes (∼200 μg/ml total lipid) were treated with 0.5% Triton X-100 at 4°C. The detergent completely dissolved the DOPC-cholesterol (Fig. 6 B, striped bars), but not the SM-cholesterol (solid bars), liposomes. The SM-cholesterol material did not rise to the top after centrifugation when it was loaded at the bottom of a sucrose gradient. Instead, it rose to the same position as SM-cholesterol liposomes that had not been Triton treated (Fig. 6, A and B, solid bars). These experiments suggest that SM-cholesterol liposomes become neither leaky nor susceptible to lysis when treated with 0.5% Triton X-100. But it was still possible that the detergent did in fact permeabilize the liposomes, but the liposomes resealed, reformed, or restructured in some way once they migrated upward to a fraction free of detergent because the dilution of detergent in solution could have, by mass action, caused it to entirely leave the membranes. To eliminate this possibility, we included 0.5% Triton X-100 in all fractions of the centrifuge tube and lowered the concentration of lipid (to 50 μg/ml), increasing detergent action. When the detergent was present everywhere, the SM/cholesterol liposomes rose to a somewhat higher level than when the detergent was not added to the centrifuge tube, but they did not rise to the top. The level to which the liposomes did rise was the same whether flotations were performed at 4°C or 23°C. Regardless of whether detergent was added to the entire tube or was only part of the membrane fraction, some NBD fluorescence (used to mark the liposomes) was still present at the bottom of the tube. This result is consistent with partial solubilization caused by the detergent. We conclude that liposomes of high SM content do not rise because the SM hinders permanent membrane rupture.

Raft fractions, as marked by proteins, are rich in SM but not in cholesterol

We used our osmotic swelling procedure, followed by douncing, to obtain raft material for biochemical characterization. Rafts are thought to be high in cholesterol and SM; each of these lipids is known to suppress the lysis of swollen vesicles ((40) and E. Evans, Boston University, personal communication, 2007). We therefore loaded the material containing rafts toward the top of a sucrose gradient (see Materials and Methods). Because vesicles shrink as they sink in a gradient, they do not need to burst to maintain tonicity. The distribution of enzymatic markers within the gradient after this centrifugation is shown in Fig. 7 A. The GPI-linked protein, alkaline phosphatase (open bars), accumulated in the upper parts of the gradient, precisely where the raft-derived membrane fraction was expected to reside. The Na+-K+ ATPase (striped bars), marking nonraft fractions, was concentrated in lower portions of the gradient. The alkaline diesterase (solid bars), also thought to lie outside of rafts, was more concentrated in the heavier fractions of the gradient as well. All of these protein distributions were in accord with those expected for raft and nonraft proteins. It thus appears that this procedure of osmotic swelling and placement of homogenized membrane toward the top of a sucrose gradient provides a reliable means to biochemically separate raft material from the rest of the plasma membrane. In this procedure, tension produced by swelling caused rafts to merge, and douncing presumably liberated large domains and allowed them to form their own vesicles.

Having demonstrated the merits of this procedure, we went on to devise a simpler one that would also isolate rafts. We reasoned that douncing without previously swelling the cells should in and of itself generate membrane tension (see Discussion). Because tension quickly promotes raft merger, douncing should directly lead to large domains. We therefore dounced cells without swelling and followed our loading procedure (Fig. 7 B). We found that the alkaline phosphatase, Na+-K+ ATPase, and alkaline diesterase distributed in exactly the same fractions as when cells had been swollen and dounced. This is as expected if douncing does indeed produce tension. We conclude that generating tension allows rafts to be isolated at physiological temperature without the need for detergents or alkaline pH.

It was, however, still possible that tension was irrelevant for raft isolation and that the mere addition of material to the top of the gradient was allowing the separation of rafts. We approached this question by swelling cells and adding a fine (12-μm) Teflon powder (PTFE) so that the powder would shear off budded domains (e.g., rafts) during gentle vortexing. Because line tension at boundaries of large domains induces the domains to bud (15), the product obtained after shearing was induced entirely by swelling. The cells that remained were still visually intact and did not look disrupted, showing that this shearing had minimal consequences to the cells. We collected the sheared material and loaded it to the top of a sucrose gradient. As observed for our prior procedure, alkaline phosphatase was concentrated in the buoyant fractions, whereas Na+-K+ ATPase was in the lower fractions (Fig. 7 C). This similarity in the location of the fractions and our microscopy experiments strongly indicate that generating tension is critical for our ability to isolate rafts at physiological temperature.

The distribution of markers was somewhat dependent on the precise isolation procedure we utilized. Alkaline diesterase distributed more or less uniformly over the fractions when only cell swelling was employed, and contents were greater (Fig. 7 C) than for the douncing procedures (Fig. 7, A and B). Also, note that the ATPase content was distributed somewhat differently for dounced versus nondounced material: it peaked at a higher density for the nondounced, swelling-only procedure (Fig. 7 C). Because it is likely that there are many nonraft domains on cell surfaces, the simplest explanation for our observed differences is that the Na+-K+ ATPase and alkaline diesterase do not reside in the same nonraft domains. In douncing, we collect all the plasma membrane (in the form of vesicles of different compositions) after applying tension, whereas in a pure swelling procedure we collect only domains that readily pinch off. Because higher line tension should facilitate pinching off of membrane domains, our data indicate that biological domains have a range of line tensions. Most importantly, we have shown that swelling alone (i.e., without any douncing) yields domains that can be isolated.

All gangliosides are membrane-anchored through ceramide and thus it is reasonable that they are all concentrated in rafts. This has been repeatedly demonstrated for GM1; GM2 and GM3 are probably also enriched in rafts (41). We further tested the validity of our raft isolation procedure by extracting total lipid from the various fractions of our dounced cells and measured sialate content in to order to estimate ganglioside content (Fig. 8, inset of B). The sialate level was highest in the lightest fraction, further supporting our conclusion that the lightest fraction does contain rafts.

Based on previous raft isolation methods, it has been thought that rafts are enriched in SM and cholesterol. Our results show that rafts are enriched in SM (Fig. 8, solid bars) but not in cholesterol (open bars): For all our procedures, the lightest fraction was enriched in SM; all other fractions were relatively low in SM. This agrees with the known properties of rafts. Cholesterol, however, was not enriched in the lightest fraction; instead, it distributed more or less equally across all fractions (Fig. 8, open bars). Also, we found that if the cholesterol was not extracted from the membrane, a standard cholesterol-oxidase assay underestimated cholesterol content of fractions that contained high levels of SM (Supplementary Fig. 1). This finding indicates that SM sequestered cholesterol from the oxidase for either steric or other reasons. The result that cholesterol is not enriched in the raft fraction is in distinct contrast to the conventional view, which has been based on isolating raft fractions by combining low temperature with detergents or alkaline pH.

DISCUSSION

The field of raft studies is large and burgeoning. Yet, ironically, the very existence of rafts is still disputed and the subject of some skepticism (26,30,42,43). This study demonstrates a clear behavioral link between small domain merger in liposomes and the emergence of large domains in cells by tension. This is strong evidence for the existence of submicroscopic rafts in cells. We have developed a procedure to isolate biological rafts at the physiological temperature of 37°C. This allowed us to measure their biochemical composition and show that domains rich in a GPI-linked protein are also enriched in SM. But the common supposition that rafts will be enriched in cholesterol appears to be unfounded.

We came to two key realizations that allowed us to develop our novel procedures for isolating biological rafts. First, we realized that lateral tension could be used to cause biological rafts to become large. Second, although vesicle membranes are light, we appreciated that vesicles rich in SM should not rise in sucrose gradients during centrifugation. Both of these ideas proved to be correct by experimentation.

Membrane tension should inhibit small raft formation

Rafts are liquid-ordered (lo) domains, more condensed than the liquid-disordered (ld) state of the bilayer surrounding it (44). That is, the area per molecule is less in an lo than in an ld phase. On physical grounds, tension, which stretches membranes, should therefore oppose the formation of rafts. Furthermore, according to the well-accepted theory of nucleation that is routinely used to describe phase separations (45), rafts should be initiated by nucleation of their constituent lipids. Following this theory, a nucleus becomes stable only when it exceeds a critical radius. The interactions among the constituent lipids favor nucleus growth, and this energy is proportional to the area of the nucleus. Energy is required to create the boundary between the raft and the surround, and this energy—proportional to the circumference of the nucleus—opposes the enlargement of the nucleus. On theoretical grounds, applying membrane tension increases the line tension of the raft (energy per unit length of the raft boundary) (46). Thus, application of membrane tension should increase the height of the energy barrier that must be surmounted if a stable nucleus is to form (13). Experimentally, we have demonstrated that, for the 20%/40%/40% SM/cholesterol/DOPC mixture, small rafts are present in the absence of tension in 100-nm-diameter liposomes (Fig. 2 (22)), but large rafts do not occur in GUVs of the same lipid composition (Fig. 1, time = 0). We have further shown that tension causes large rafts to appear in this GUV mixture even though tension should hinder—and certainly not induce—their formation. If tension causes large rafts to appear, it follows that these rafts were generated from the merger of smaller rafts that naturally exist in the absence of tension.

One might assume that the presence of small rafts in 100-nm liposomes would not imply that they are also present in the much larger GUVs because a difference in curvature between the two liposomes would impose different packing constraints on the lipids. But, in fact, the membranes of our small liposomes are effectively as flat as those of GUVs, and any strains or packing constraints that may be placed on the lipids are the same in the two liposome systems: the geometric curvature of the membrane of a 100-nm liposome is close to zero. To place this in another perspective, ∼10−4 kBT is required per lipid to bend a flat membrane into a sphere of 100 nm, and ∼10−8 kBT is required per lipid for a sphere the size of a GUV. This energy per lipid is much less than kBT in both cases.

Why might tension promote raft merger? There are several possibilities, but we currently favor the following thermodynamic mechanism. In merging, rafts reduce their total perimeter and thereby favorably minimize their edge energy. But the reduction in the number of rafts on merger lessens the configurational entropy (13). Consequently, line tension must be large enough for the reduction in edge energy to exceed the entropic penalty. From theoretical calculations, lateral tension causes line tension to increase (46). Thus, if line tension is naturally small, rafts will not be able to merge, but the increase in line tension during liposome swelling, cell swelling, or douncing of cells may be sufficient to make it energetically favorable for rafts to merge. On removal of lateral tension, line tension would decrease, and many small domains would be thermodynamically favored over one large domain. The large rafts would disperse, as we found experimentally.

Vesicle flotation in density gradients requires vesicle rupture

Membrane fractionation using gradient centrifugation is based on differences in the density of membranes. But vesicle density is generally more dependent on the density of aqueous contents than membrane density. For a vesicle to rise from a higher to a lower sucrose concentration during centrifugation, the vesicle must at some point lyse to allow sucrose and other soluble materials within the vesicle to diffuse out. Vesicles containing high amounts of SM are less likely to lyse than those that do not, and thus, SM-rich vesicles will equilibrate to higher densities (i.e., they will not float as high as SM-free vesicles) regardless of their membrane density. The inability of SM-rich vesicles to rise is demonstrated by our liposome flotation experiments and our finding that SM-rich liposomes rise only to the interface immediately above the level in which they were placed, regardless of the initial placement. Our finding that these liposomes did not rise to the top even when Triton treated suggests that at least some raft material is not recovered in the buoyant fraction in the standard protocol of isolating DRMs from cells. Other investigators may have tried to isolate raft material at 37°C using douncing procedures, but none has reported success. An investigator who followed the traditional method of loading material at the bottom of gradients, not appreciating the importance of vesicle lysis for flotation to occur, would not have obtained raft material in the lighter, top fractions.

An obvious disadvantage of loading and then collecting material from the top is that water-soluble proteins and other undesired material will reside there after centrifugation. In contrast, loading a sample on the bottom and collecting from the top fraction eliminates the unwanted material. But as we have now shown, loading material on the bottom also eliminates the raft membranes from floating to the top fraction. Our procedures ensure that all raft material is collected. Procedures to further purify the raft material can be developed.

The lipid and protein content of rafts

The lightest fraction of each centrifugation showed the hallmarks of a raft fraction: it was enriched in alkaline phosphatase and depleted in Na+-K+ ATPase and alkaline diesterase. This was the only fraction enriched in SM, further supporting its identification as a raft fraction. Our finding, however, that cholesterol is not enriched in this fraction, but rather is roughly the same in all fractions, is opposed to the conventional view of rafts.

FRET and other methods are used to monitor phase separation in lipid bilayers composed of cholesterol and two other components of varying percentages. These measurements have been used to map phase diagrams and to infer the tie lines that quantify coexistence of lo and ld domains. Based on this approach, the lo raft phase has been concluded to be considerably richer in cholesterol than is the surrounding ld phase. This conclusion is quite reasonable at low concentrations of cholesterol because SM interacts more strongly with SM and saturated phosphatidylcholine (PC) than unsaturated PC. But its validity is questionable for high (e.g., 40–50 mol %) cholesterol content bilayers. A fixed area of an lo phase must have limited cholesterol capacity, and any cholesterol in excess of this limit would reside in the surrounding ld domain. Thus, the mole fraction content of cholesterol can be comparable in lo and ld phases at high cholesterol concentrations even if cholesterol preferentially interacts with other raft components. In fact, cholesterol content has previously been measured in lo domains in bilayers by nonanalytical means, and it was found that for bilayers containing high amounts of cholesterol, the cholesterol distributed more or less equally between the lo and the surrounding ld membrane (12,25). Thus, both biological rafts isolated by our procedure and rafts in high-cholesterol lipid bilayer membranes are enriched in SM but do not show significantly enriched cholesterol. It may be that the composition of the lipid portion of a biological raft is similar to the composition of a pure lipid raft. If it is, it may be appropriate to apply physical principles that are applicable to lipid bilayer rafts to biological rafts.

We used CEMss cells because they do not express caveolin, and thus, our isolated rafts cannot include material derived from caveolae. Caveolae, in contrast to rafts, are relatively large and they have been unambiguously identified. Caveolae have high cholesterol content (47,48), and this probably contributes to the view that caveolin-free rafts are also rich in cholesterol. The standard procedures for biochemical isolation of rafts have been to use detergents or alkaline pH at 4°C. Protein content of rafts has been inferred, by and large, from DRM fractions. This detergent-insoluble fraction has generally been quite rich in alkaline phosphatase (16), an enrichment greater than we found. But rafts isolated at 4°C using high pH yielded alkaline phosphatase levels (16) comparable to those measured in this study.

We propose that the use of tension is a reliable means to determine whether a particular protein does indeed reside in rafts and whether this residence is affected by the state of the cell. Our procedure should not induce loss of either intrinsic or extrinsic membrane proteins. In contrast, alkaline pH should cause extrinsic membrane proteins to dissociate from membranes, and detergents could cause dissociation of some proteins that have membrane anchorage dependent on acyl chains. Our results show that standard douncing (but at 37°C rather than the usual 4°C) allows rafts to be isolated. One can be virtually certain that douncing generates membrane tension: tension is the reason douncing ruptures membranes. Because membrane rupture requires high tensions, the tensions produced by douncing should be large. The methods we have developed that isolate biological rafts at 37°C have already shown that rafts are not enriched in cholesterol and that they are similar in lipid composition to those of model bilayer membranes.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view all of the supplemental files associated with this article, visit www.biophysj.org.

Acknowledgments

We thank Sofya Brener for technical help and Dr. Yuri Chizmadzhev for a critical reading of the manuscript.

Supported by National Institutes of Health R01 GM-066837.

Abbreviations used: DRM, detergent-resistant membrane; SM, sphingomyelin; GUV, giant unilamellar vesicle; NBD-DPPE, NBD-labeled dipalmitoylphosphatidylethanolamine; Rho-DOPE, rhodamine-labeled dioleoylphosphatidylethanolamine; SUV, small unilamellar vesicle.

Editor: Joshua Zimmerberg.

References

- 1.Hess, S. T., M. Kumar, A. Verma, J. Farrington, A. Kenworthy, and J. Zimmerberg. 2005. Quantitative electron microscopy and fluorescence spectroscopy of the membrane distribution of influenza hemagglutinin. J. Cell Biol. 169:965–976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pike, L. J. 2006. Rafts defined: a report on the Keystone Symposium on Lipid Rafts and Cell Function. J. Lipid Res. 47:1597–1598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pralle, A., P. Keller, E. L. Florin, K. Simons, and J. K. Horber. 2000. Sphingolipid-cholesterol rafts diffuse as small entities in the plasma membrane of mammalian cells. J. Cell Biol. 148:997–1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jacobson, K., O. G. Mouritsen, and R. G. Anderson. 2007. Lipid rafts: at a crossroad between cell biology and physics. Nat. Cell Biol. 9:7–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hancock, J. F. 2006. Lipid rafts: contentious only from simplistic standpoints. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 7:456–462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lai, E. C. 2003. Lipid rafts make for slippery platforms. J. Cell Biol. 162:365–370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown, D. A. 2006. Lipid rafts, detergent-resistant membranes, and raft targeting signals. Physiology (Bethesda). 21:430–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Macdonald, J. L., and L. J. Pike. 2005. A simplified method for the preparation of detergent-free lipid rafts. J. Lipid Res. 46:1061–1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feigenson, G. W. 2007. Phase boundaries and biological membranes. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 33:63–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Silvius, J. R., and I. R. Nabi. 2006. Fluorescence-quenching and resonance energy transfer studies of lipid microdomains in model and biological membranes. Mol. Membr. Biol. 23:5–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dietrich, C., L. A. Bagatolli, Z. N. Volovyk, N. L. Thompson, M. Levi, K. Jacobson, and E. Gratton. 2001. Lipid rafts reconstituted in model membranes. Biophys. J. 80:1417–1428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Veatch, S. L., I. V. Polozov, K. Gawrisch, and S. L. Keller. 2004. Liquid domains in vesicles investigated by NMR and fluorescence microscopy. Biophys. J. 86:2910–2922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frolov, V. A., Y. A. Chizmadzhev, F. S. Cohen, and J. Zimmerberg. 2006. Entropic traps in the kinetics of phase separation in multicomponent membranes stabilize nanodomains. Biophys. J. 91:189–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Samsonov, A. V., I. Mihalyov, and F. S. Cohen. 2001. Characterization of cholesterol-sphingomyelin domains and their dynamics in bilayer membranes. Biophys. J. 81:1486–1500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baumgart, T., S. T. Hess, and W. W. Webb. 2003. Imaging coexisting fluid domains in biomembrane models coupling curvature and line tension. Nature. 425:821–824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eckert, G. P., U. Igbavboa, W. E. Muller, and W. G. Wood. 2003. Lipid rafts of purified mouse brain synaptosomes prepared with or without detergent reveal different lipid and protein domains. Brain Res. 962:144–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hu, Y. K., and J. H. Kaplan. 2000. Site-directed chemical labeling of extracellular loops in a membrane protein. The topology of the Na,K-ATPase alpha-subunit. J. Biol. Chem. 275:19185–19191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.He, X., F. Chen, M. M. McGovern, and E. H. Schuchman. 2002. A fluorescence-based, high-throughput sphingomyelin assay for the analysis of Niemann-Pick disease and other disorders of sphingomyelin metabolism. Anal. Biochem. 306:115–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ladisch, S., and B. Gillard. 1987. Isolation and purification of gangliosides from plasma. Methods Enzymol. 138:300–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hikita, T., K. Tadano-Aritomi, N. Iida-Tanaka, H. Toyoda, A. Suzuki, T. Toida, T. Imanari, T. Abe, Y. Yanagawa, and I. Ishizuka. 2000. Determination of N-acetyl- and N-glycolylneuraminic acids in gangliosides by combination of neuraminidase hydrolysis and fluorometric high-performance liquid chromatography using a GM3 derivative as an internal standard. Anal. Biochem. 281:193–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brown, R. E., K. L. Jarvis, and K. J. Hyland. 1989. Protein measurement using bicinchoninic acid: elimination of interfering substances. Anal. Biochem. 180:136–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ayuyan, A. G., and F. S. Cohen. 2006. Lipid peroxides promote large rafts: effects of excitation of probes in fluorescence microscopy and electrochemical reactions during vesicle formation. Biophys. J. 91:2172–2183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang, J., J. B. Velotta, A. A. McDonough, and R. A. Farley. 2001. All human Na+-K+-ATPase alpha-subunit isoforms have a similar affinity for cardiac glycosides. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 281:C1336–C1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.MacDonald, R. C., R. I. MacDonald, B. P. Menco, K. Takeshita, N. K. Subbarao, and L. R. Hu. 1991. Small-volume extrusion apparatus for preparation of large, unilamellar vesicles. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1061:297–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crane, J. M., and L. K. Tamm. 2004. Role of cholesterol in the formation and nature of lipid rafts in planar and spherical model membranes. Biophys. J. 86:2965–2979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shaw, A. S. 2006. Lipid rafts: now you see them, now you don't. Nat. Immunol. 7:1139–1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Evans, E., V. Heinrich, F. Ludwig, and W. Rawicz. 2003. Dynamic tension spectroscopy and strength of biomembranes. Biophys. J. 85:2342–2350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Melikov, K. C., V. A. Frolov, A. Shcherbakov, A. V. Samsonov, Y. A. Chizmadzhev, and L. V. Chernomordik. 2001. Voltage-induced nonconductive pre-pores and metastable single pores in unmodified planar lipid bilayer. Biophys. J. 80:1829–1836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Simmons, G., A. J. Rennekamp, N. Chai, L. H. Vandenberghe, J. L. Riley, and P. Bates. 2003. Folate receptor alpha and caveolae are not required for Ebola virus glycoprotein-mediated viral infection. J. Virol. 77:13433–13438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kenworthy, A. K., N. Petranova, and M. Edidin. 2000. High-resolution FRET microscopy of cholera toxin B-subunit and GPI-anchored proteins in cell plasma membranes. Mol. Biol. Cell. 11:1645–1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pedersen, P. A., J. R. Jorgensen, and P. L. Jorgensen. 2000. Importance of conserved alpha -subunit segment 709GDGVND for Mg2+ binding, phosphorylation, and energy transduction in Na,K-ATPase. J. Biol. Chem. 275:37588–37595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Storrie, B., and E. A. Madden. 1990. Isolation of subcellular organelles. Methods Enzymol. 182:203–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brown, D. A., and J. K. Rose. 1992. Sorting of GPI-anchored proteins to glycolipid-enriched membrane subdomains during transport to the apical cell surface. Cell. 68:533–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hanada, K., M. Nishijima, Y. Akamatsu, and R. E. Pagano. 1995. Both sphingolipids and cholesterol participate in the detergent insolubility of alkaline phosphatase, a glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored protein, in mammalian membranes. J. Biol. Chem. 270:6254–6260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bravo-Zehnder, M., P. Orio, A. Norambuena, M. Wallner, P. Meera, L. Toro, R. Latorre, and A. Gonzalez. 2000. Apical sorting of a voltage- and Ca2+-activated K+ channel alpha-subunit in Madin-Darby canine kidney cells is independent of N-glycosylation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 97:13114–13119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hansen, G. H., L. L. Niels-Christiansen, E. Thorsen, L. Immerdal, and E. M. Danielsen. 2000. Cholesterol depletion of enterocytes. Effect on the Golgi complex and apical membrane trafficking. J. Biol. Chem. 275:5136–5142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kalka, D., C. von Reitzenstein, J. Kopitz, and M. Cantz. 2001. The plasma membrane ganglioside sialidase cofractionates with markers of lipid rafts. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 283:989–993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Welker, P., B. Geist, J. H. Fruhauf, M. Salanova, D. A. Groneberg, E. Krause, and S. Bachmann. 2007. Role of lipid rafts in membrane delivery of renal epithelial Na+-K+-ATPase, thick ascending limb. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 292:R1328–R1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lin, C. W., M. Sasaki, M. L. Orcutt, H. Miyayama, and R. M. Singer. 1976. Plasma membrane localization of alkaline phosphatase in HeLa cells. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 24:659–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Needham, D., and R. S. Nunn. 1990. Elastic deformation and failure of lipid bilayer membranes containing cholesterol. Biophys. J. 58:997–1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boesze-Battaglia. 2006. Isolation of membrane rafts and signaling complexes. Methods Mol. Biol. 332:169–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Douglass, A. D., and R. D. Vale. 2005. Single-molecule microscopy reveals plasma membrane microdomains created by protein-protein networks that exclude or trap signaling molecules in T cells. Cell. 121:937–950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nichols, B. 2005. Cell biology: without a raft. Nature. 436:638–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maxfield, F. R., and I. Tabas. 2005. Role of cholesterol and lipid organization in disease. Nature. 438:612–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gunton, J. D., M. San Miguel, and P. S. Sahni. 1983. The dynamics of first-order phase transitions. In Phase transitions and critical phenomena, vol. 8. C. Domb and J. L. Lebowitz, editors. Academic Press, New York. p. 267–482.

- 46.Akimov, S. A., P. I. Kuzmin, J. Zimmerberg, and F. S. Cohen. 2007. Lateral tension increases the line tension between two domains in a lipid bilayer membrane. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlin. Soft Matter Phys. 75:011919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Smart, E. J., Y. Ying, W. C. Donzell, and R. G. Anderson. 1996. A role for caveolin in transport of cholesterol from endoplasmic reticulum to plasma membrane. J. Biol. Chem. 271:29427–29435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Smart, E. J., Y. S. Ying, P. A. Conrad, and R. G. Anderson. 1994. Caveolin moves from caveolae to the Golgi apparatus in response to cholesterol oxidation. J. Cell Biol. 127:1185–1197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]