Abstract

Among the major antimicrobial products of macrophages are reactive intermediates of the oxidation of nitrogen (RNI) and the reduction of oxygen (ROI). Selection of recombinants in acidified nitrite led to the cloning of a novel gene, noxR1, from a pathogenic clinical isolate of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Expression of noxR1 conferred upon Escherichia coli and Mycobacterium smegmatis enhanced ability to resist RNI and ROI, whether the bacteria were exposed to exogenous compounds in medium or to endogenous products in macrophages. These studies provide the first identification of an RNI resistance mechanism in mycobacteria, point to a new mechanism for resistance to ROI, and raise the possibility that inhibition of the noxR1 pathway might enhance the ability of macrophages to control tuberculosis.

Each year, Mycobacterium tuberculosis kills nearly three million among the one-third of the world's population who are infected (1), making it the most deadly as well as one of the most successful bacterial pathogens of the human species. Tuberculosis arises in a small proportion of infected individuals in whose macrophages the bacteria replicate extensively, when, for example, malnutrition (2) or HIV (3) impede the cell-mediated immune response that normally leads to the activation of macrophages. However, in some cases, no host immune impairment is evident, and the question arises whether some disease-causing strains of M. tuberculosis have means to resist the toxic molecules produced by activated macrophages. Identification of a gene in a pathogen conferring resistance to a putative antimicrobial product of the host could be considered evidence that the host product exerts evolutionary pressure on the pathogen. Moreover, such genes may be considered virulence factors, and inhibition of their action might enhance host defense.

Two of the major antimicrobial mechanisms of activated macrophages depend on the synthesis of inorganic radical gasses by immunologically regulated flavocytochrome complexes that use NADPH to reduce molecular oxygen. When oxygen is the sole cosubstrate, the product is superoxide (O2 −; reference 4) when l-arginine is an additional cosubstrate, the product is nitric oxide (NO; reference 5).1 These radicals react with themselves, oxygen, transition metals, halides, sulfhydryls, and each other to produce a series of broadly cytotoxic products termed reactive oxygen intermediates (ROI) and reactive nitrogen intermediates (RNI), as well as at least one compound with features of both, peroxynitrite (OONO−; references 6 and 7).

M. tuberculosis resists ROI by a diversity of mechanisms. Phenolic glycolipids (8) and cyclopropanated mycolic acids (9) protect the cell wall, while catalase, alkylhydroperoxide reductase (10), and superoxide dismutase (11, 12) guard the cytosol. Moreover, M. tuberculosis may enter macrophages via complement receptors (13, 14), a pathway that fails to stimulate generation of ROI in some populations of macrophages (15). The ability of M. tuberculosis to mount such a broad defense against ROI implies that other products of the activated macrophage may be more important for tuberculostasis. Indeed, activated murine macrophages selectively deficient in production of ROI were nonetheless mycobactericidal (16).

In contrast, abundant evidence establishes the importance of RNI in the control of mycobacteria, at least in the mouse. M. tuberculosis proliferates exuberantly in mice rendered selectively deficient in nitric oxide synthase type 2 (NOS2 or iNOS; reference 17). The organism also grows rapidly in mice made deficient in components of the cell-mediated immune response that normally leads to the induction of NOS2 (for review see reference 17), as well as in mice dosed with organochemicals (for review see references 2 and 17) or glucocorticoids (17) that inhibit the action or expression of NOS2. NOS2 was recently shown to be expressed by alveolar macrophages collected from the lungs of patients with tuberculosis (18) as well as pulmonary fibrosis (19).

However, in contrast to the situation with ROI, no specific mechanisms have been identified by which mycobacteria resist RNI. There was variability in the degree to which RNI inhibited several mycobacterial strains in vitro (20, 21), and the more resistant strains of M. tuberculosis were more virulent in guinea pigs (21). M. tuberculosis strain CB3.3, a drug-susceptible clinical isolate, caused >10% of the tuberculosis cases reported in New York City between 1992 and 1993 (22) and was the most RNI resistant of those tested (23). Reasoning that RNI-resistant strains may express RNI resistance genes, we used a library from M. tuberculosis CB3.3 to clone a gene that does not resemble previously recognized antioxidants, but which protects transformed enteric and mycobacteria from both RNI and ROI.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Strains and Growth Conditions.

The following mycobacterial strains were used in this study: M. smegmatis mc2155 (24), M. tuberculosis CB3.3 (22), M. tuberculosis H37Ra (American Type Culture Collection/[ATTC, Rockville, MD] No. 25177), M. tuberculosis H37Rv (ATTC No. 25618), M. bovis (ATTC No. 19210), M. africanum (ATTC No. 25420), M. gordonae (ATTC No. 14470), M. fortuitum (ATTC No. 6841), M. avium (ATTC No. 25291), M. intracellulare (ATTC No. 13950), M. kansassi (ATTC No. 12478). Mycobacterial strains were grown in Middlebrook 7H9 broth (Difco Labs. Inc., Detroit, MI) supplemented with 2% glycerol, 0.05% Tween 80, and ADC supplement (Difco Labs. Inc.) or plated on 7H11 agar (Difco Labs. Inc.). Luria-Bertani (LB) broth or LB agar were used for Escherichia coli strains XL1-Blue (Stratagene Inc., La Jolla, CA), HB101 (ATTC), DH5α (GIBCO/BRL, Gaithersburg, MD), M15 (QIAGEN Inc., Chatsworth, CA), GC4468 and DJ109 (a soxRS mutant, provided by T. Nunoshiba and B. Demple, Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, MA; reference 25), and JTG100 and its oxyR-deficient derivative, JTG101 (26), also the gift of B. Demple. Ampicillin and hygromycin B (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) were used at 100 μg/ml and 200 μg/ml, respectively, to grow E. coli. Hygromycin B was used at 50 μg/ml to grow mycobacteria.

Plasmids.

pBluescript (pBS; Stratagene Inc.) served as a cloning vector and pQE31 (QIAGEN Inc.) as an expression vector in E. coli. The shuttle vector pOLYG (a gift from Peadar O'Gaora and D.B. Young, Department of Medical Microbiology, St. Mary's Hospital Medical School, London, UK) is a derivative of p16R (27). pSMT3 is derived from pOLYG and contains the hsp60 promoter for overexpression of genes in mycobacteria (also a gift from P. O'Gaora).

Cloning of M. tuberculosis DNA Fragment Associated with Resistance against RNI.

Chromosomal DNA was isolated from M. tuberculosis CB3.3 as previously described (28) and digested with EcoRI and BamHI. A genomic library was constructed by ligation of the DNA fragments into the E. coli vector pBS. E. coli XL1-Blue was initially tested for growth in LB at various pH and NaNO2 concentrations. At pH 6.0 and 10 mM NaNO2, its growth was completely suppressed. Therefore, the genomic library was electroporated into strain XL1-Blue and the recombinants were screened for growth in acidified sodium nitrite (ASN; LB at pH 6.0 containing 10 mM NaNO2).

Construction of pNO14.1 and its Open Reading Frame Mutant.

A HindIII–SmaI fragment of pNO14 was cloned into the HindIII and HincII sites of pBS. The resulting plasmid, pNO14.1, still contains the complete open reading frame (ORF)1. A point mutation was introduced at codon 12 of ORF1 (nucleotide 36 G → T), which created a stop codon (TGA) at that position. This mutation does not affect the amino acid sequence of the putative protein encoded by ORF2. The mutation was introduced by PCR mutagenesis. The final construct, pNO14.1-mut1, was confirmed by sequencing.

Analysis of the Resistant Phenotype.

The relative resistance to chemically generated RNI was tested by inoculating a 1:100 dilution of the overnight or log-phase culture of the strain to be tested into 3 ml of LB, pH 5.3, or 7H9, pH 5.3, containing NaNO2 (Sigma Chemical Co.) at various concentrations. Resistance to paraquat (Sigma Chemical Co.), nalidixic acid (Sigma Chemical Co.), NaOCl (Aldrich Chemical Company, Inc., Milwaukee, WI), and ethanol was measured in LB, pH 7.0. Cultures were incubated at 37°C for the indicated periods. The chosen conditions resulted in at least a 10-fold reduction in CFU of the control E. coli HB101. The number of viable bacteria was determined by plating on LB agar. Alternatively, where indicated, a microplate assay was used that detects the ability of surviving bacteria to reduce a formulation of resazurin termed AlamarBlue® (Sensititre/Alamar; AccuMed International Companies, Westlake, OH) to a fluorescent product (29).

Northern Blot Analysis and Reverse Transcriptase PCR.

RNA was isolated from 20 ml logarithmically growing mycobacterial cultures according to the FastPrep FP120 bead beater apparatus (Bio-101, La Jolla, CA) protocol. The integrity of the RNA preparation was verified by the presence of two sharp rRNA bands, 1,500 and 3,100 nucleotides in length.

Two oligonucleotides, RNA-1 (5′-gacgcgctgatcgccgatctacgcgcgcatggtggtcgg-3′) and RNA-2 (5′-cggcaacgccggtgaacaacgcgcgggcatcctcgccc-3′) were labeled with dioxigenin using the oligonucleotide tailing kit (Boehringer Mannheim Biochemicals, Indianapolis, IN) to serve as probes for the transcripts of the two open reading frames, ORF1 and ORF2, respectively. Northern blots were carried out according the GeniusTM System User's Guide For Membrane Hybridization (Boehringer Mannheim Biochemicals). Reverse transcriptase (RT)–PCR was performed using the Perkin Elmer Gene Amp RNA PCR Kit (Perkin Elmer Corp., Norwalk, CT). In brief, 0.2–1 μg total RNA was transcribed by Moloney MuLV RT into cDNA with either random hexamer primers or a specific primer for the ORF1 RNA at 42°C for 15 min. cDNA specific primers were added (Ia: 5′-ctacccgcgcgcggagtgacgctgacc-3′; Ib: 5′-cggcaacgccggtgaacaacgcgcgggcatcctcgccc-3′; IIa: 5′-ggggatggcggtgggtgcggtgtcg-3′; IIb: 5′-gacgcgctgatcgccgatctacgcgcgcatggtggtcgg-3′), and the reaction was carried out with AmpliTaq (Perkin-Elmer, Norwalk, CT) DNA polymerase in a volume of 100 μl. The combined annealing and extending reaction was done at 60°C for 30 s.

Protein Expression.

noxR1 was cloned behind an inducible T5 promoter into the expression vector pQE-31 (QIAGEN Inc.). M15 (pREP4) pQE-31-ORF1 were grown in LB containing 100 mg/l ampicillin and 25 mg/l kanamycin to an OD580 of 1.0 and induced with 1.5 mM IPTG (isopropyl-β-thiogalactopyranoside). After 4 h, bacteria were harvested and a sample of lysate was subjected to SDS-PAGE and Coomassie blue staining to check for overexpression of recombinant protein. Protein containing an NH2-terminal histidine tag was purified on Ni-NTA resin columns (QIAGEN Inc.) and analyzed by SDS-PAGE. The NH2-terminal sequence of the purified protein was established for 19 residues, sufficient to read beyond the tag and 7 residues into NoxR1 proper. The purified protein was injected in female New Zealand White rabbits (4 injections of 100 mg NoxR1, at 4 wk intervals). The resulting antiserum was used for immunoblot analysis of bacterial lysates or purified protein by standard procedures. Affinity-purified antibody was prepared as described in Results.

Studies in Macrophages.

An assay modified from that previously described (30) was used to determine the survival of M. smegmatis strains inside macrophages. Wild-type (iNOS+/+) and iNOS-deficient mice (iNOS−/−; C57BL/6x129/SvEv) (31) and wild-type and phox-91–deficient mice (C57BL6/J) (32) were injected intraperitoneally with 1.0 ml of sterile, freshly prepared 5 mM sodium periodate (Sigma Chemical Co.) in PBS 4 d before harvest. The mice were killed by cervical dislocation or CO2 inhalation. Peritoneal cells were harvested by lavage with 10 ml ice-cold sterile RPMI (Sigma Chemical Co.), pH 7.2. Cells were collected by centrifugation for 10 min at 250 g at 4°C and resuspended in RPMI medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (HyClone, Logan, UT), 1% glutamine (complete medium), and 10 μg/ml gentamicin. Viable cells were counted on a hemocytometer in the presence of trypan blue and the proportion of macrophages determined by differential count of Diff-Quik stained Cytospin (Shandon, Inc., Pittsburgh, PA) preparations. Peritoneal cells (4 × 105, ∼50% macrophages) were plated in 96-well tissue-culture plates (Corning Medical and Scientific, Medfield, MA) at 100 μl per well. In some experiments, recombinant mouse IFN-γ (Genentech, South San Francisco, CA) was added at 50 U/ml. The plates were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2, and 12–24 h later the adherent monolayers were washed twice with sterile PBS to remove gentamicin containing medium; complete removal required that the plates be emptied with a hard flick in each wash. Fresh complete medium ± mIFN-γ was added, and 24–48 h after the initial plating the cells were washed again with sterile PBS, and reconstituted with complete medium before infection.

Freshly electroporated M. smegmatis were grown to mid-log phase. Bacteria were opsonized in 10% fresh mouse serum for 30 min at 37°C, and 10 μl of the opsonized bacteria (∼2 × 105) were added to each well. The plates were centrifuged for 5 min at 250 g to synchronize the infection, and were then incubated at 37°C for 30 min to allow phagocytosis. The wells were washed three times with sterile PBS to remove free bacteria. Complete medium (100 μl) containing 10 μg/ml gentamicin was added to each well, and the plates were incubated at 37°C. Gentamicin was added to prevent extracellular replication of mycobacteria that may not have been internalized or may have escaped from dying macrophages. Samples were taken at the indicated time points from individual wells in triplicate, as follows. The medium was removed and 50-μl aliquots were saved for nitrite determination. The cell monolayer was washed twice with PBS and lysed with 100 μl 0.1% sodium deoxycholate in PBS. Appropriate dilutions of the lysates were plated onto LB plates containing 50 μg/ml hygromycin B for CFU determinations.

To monitor macrophage production of NO, we measured nitrite in the culture supernatants as an accumulating oxidation product. The Griess reaction was performed as previously described (33). M. smegmatis itself produced no detectable nitrite under the conditions of these experiments, as evidenced in cultures with iNOS−/− macrophages (see Fig. 7 B, inset).

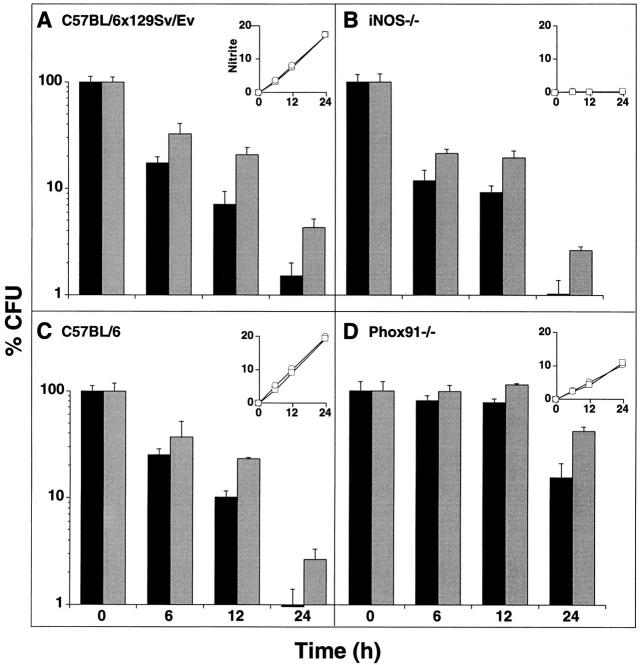

Figure 7.

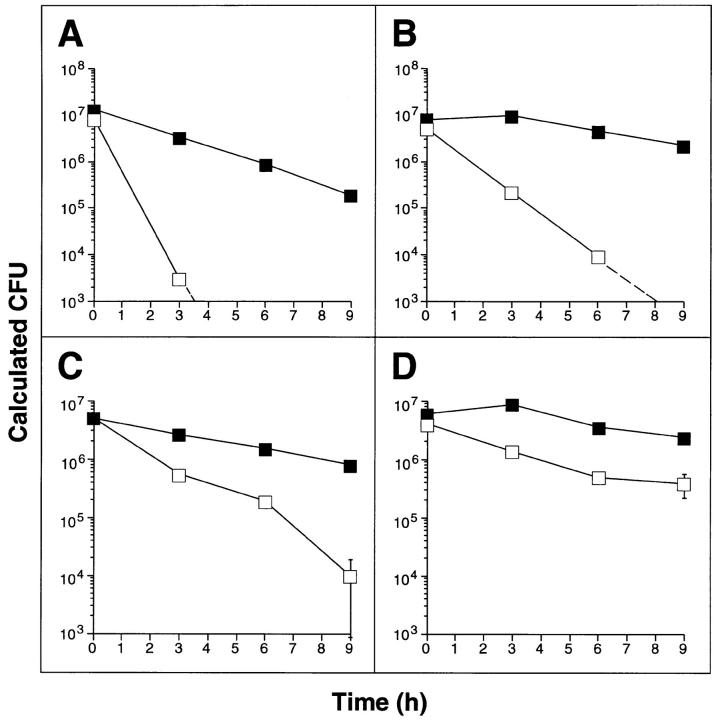

Survival of noxR1-transformed M. smegmatis in wild-type and genetically altered macrophages. Periodate-elicited peritoneal macrophages from (A) wild-type C57BL/ 6x129/SvEv, (B) iNOS−/− C57BL/6x129/ SvEv, (C) wild-type C57BL/6, or (D) phox91−/− C57BL/6 mice were pretreated or not with mouse IFN-γ and infected with M. smegmatis transformed with either pOLYG (black bars) or pOLYG–NO14 (gray bars). At indicated times, macrophages were lysed and surviving bacterial CFU were determined. Values are means ± SE for triplicate macrophage cultures as a percentage of the starting CFU, defined as the numbers of CFUs recoverable from the cells after the 30 min uptake period; the latter averaged 2 × 105/well, or ∼1/macrophage. (Insets) Nitrite accumulation (nmol/well) in the same cultures of macrophages infected with M. smegmatis–pOLYG (squares) or pOLY– NO14 (circles). Values are means ± SE; error bars fall within the symbols. One of six similar experiments (three with IFN-γ and three without).

Macrophage production of hydrogen peroxide was assessed by the horseradish peroxidase–catalyzed oxidation of fluorescent scopoletin to a nonfluorescent product, using a microplate format (34).

Decreased production of NO2 − or hydrogen peroxide and diminished bactericidal activity could not be attributed to differential loss of macrophages from the monolayers, as monitored by measurements of adherent cell protein in the same cultures (34).

Results

Cloning of an M. tuberculosis Gene Associated with Resistance to RNI.

E. coli XL1-Blue was electroporated with a genomic library of M. tuberculosis CB3.3 and exposed for 24 h to ASN (6 mM NaNO2, pH 6.0). Protonation of NaNO2 generates HNO2, whose dismutation provides NO and nitrate, and, through reaction of NO with oxygen, other RNI (35, 36). The main products of these reactions are probably dinitrogen tri- and tetra-oxides (N2O3 and N2O4) as well as S-nitrosothiols, which have profound bacteriostatic effects (37, 38, 39). ASN plays a physiologic role in the microbicidal system of the stomach (40) and the combination of RNI and low pH also mimics aspects of the intraphagolysosomal milieu of the macrophage (5, 41). The chosen conditions killed E. coli XL1-Blue efficiently (>7 log10 in 24 h). Surviving transformants were detected with a frequency of <10−6. One recombinant plasmid, called pNO14, consistently conferred upon XL1-Blue and four other E. coli hosts (DH5α, HB101, GC4468, and JTG100) as well as Salmonella typhimurium LT2 and 14028 (data not shown) an enhanced ability to resist ASN. By 12 h, transformation of HB101 with pNO14 afforded a 50-fold increase in survival above transformation of the same E. coli host with the vector alone (Fig. 1 A).

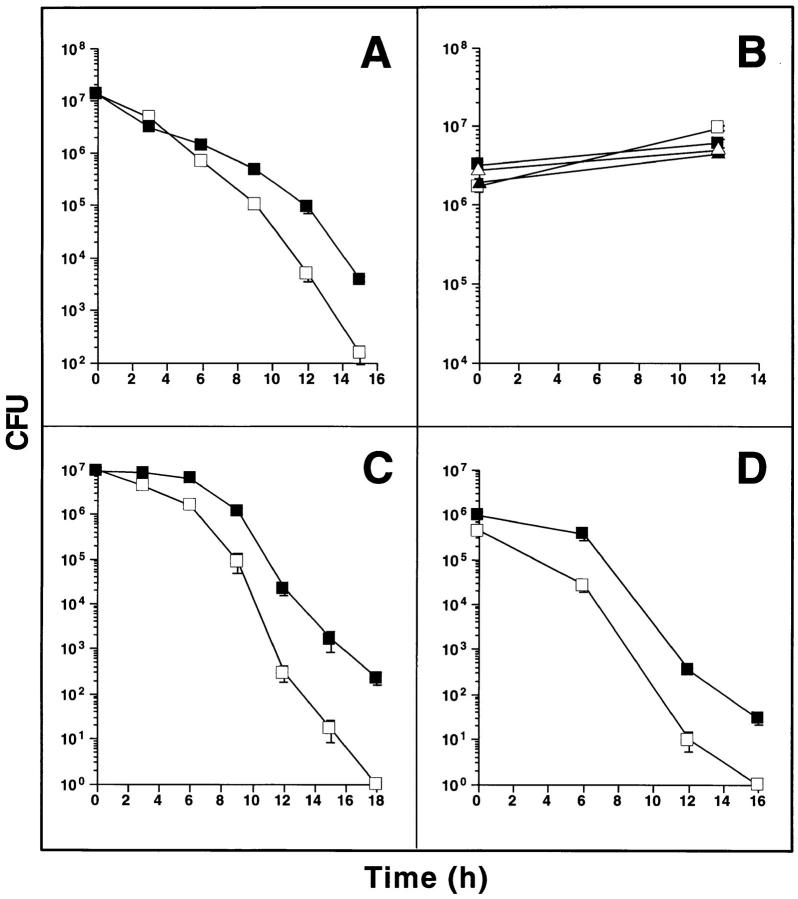

Figure 1.

Plasmid pNO14 confers enhanced survival on E. coli in ASN. (A) Survival of E. coli HB101 pBS (open squares) and HB101 pNO14 (solid squares) in ASN medium. Overnight cultures were diluted 100-fold into LB, pH 5.3, containing 10 mM NaNO2, and incubated at 37°C. CFUs were determined at indicated times by plating serial dilutions on LB agar containing ampicillin. In this and subsequent panels, results are means ± SE for triplicates; some error bars fall within the symbols. (B) Growth of M. smegmatis pOLYG (open symbols) and M. smegmatis pOLYG-NO14 (solid symbols) in 7H9 medium containing 30 mM sodium nitrite at pH 7.4 (triangles) or 30 mM sodium nitrate at pH 5.3 (squares). CFU were determined by plating on LB agar containing 50 μg/ml hygromycin, either at onset of culture or after 12 h. (C and D) Survival of M. smegmatis pOLYG (open squares) and M. smegmatis pOLYG-NO14 (solid squares) in ASN medium. Bacteria were grown to an optical density of A600 = 4.5 (stationary phase cultures, C) or to A600 = 1.5 (logarithmic phase cultures, D) and diluted 100-fold in 7H9 medium, pH 5.3, containing 30 mM NaNO2 for stationary phase cultures and 20 mM NaNO2 for logarithmic phase cultures. At indicated times CFUs were determined by plating appropriate dilutions on LB agar containing 50 μg/ml hygromycin.

Means are not yet available for the facile genetic manipulation of M. tuberculosis. As a substitute mycobacterial species in which to analyze the function of pNO14, we chose M. smegmatis; the organism is fast-growing and easily transformable, and, as shown below, lacks a chromosomal copy of the gene carried by pNO14. The 680-bp mycobacterial DNA fragment of pNO14 was cloned into the shuttle plasmid pOLYG (27) and electroporated into M. smegmatis mc2155 (24). Neither the pOLYG–NO14– nor the vector-transformed strain was killed by sodium nitrate at pH 5.3, nor by sodium nitrite at pH 7.4 (Fig. 1 B). These findings excluded a mycobactericidal effect of acid plus nitrate (the nonreactive dismutation product of HNO2), and of nitrite under conditions that disfavor the formation of NO. In contrast, when recombinant and control strains were exposed to nitrite at pH 5.3, both strains succumbed. Compared to its vector-transformed counterpart, M. smegmatis transformed with pOLYG–NO14 was increasingly less susceptible after 6 h, attaining a 100-fold relative advantage by 15 h (Fig. 1 C). Logarithmically growing M. smegmatis (Fig. 1 D) were more susceptible to ASN than those at stationary growth phase (Fig. 1 C). However, the protective effect of pOLYG–NO14 was manifest in both phases. Thus, a gene product encoded by NO14 conferred relative resistance to RNI upon both E. coli and M. smegmatis.

Expression Analyses.

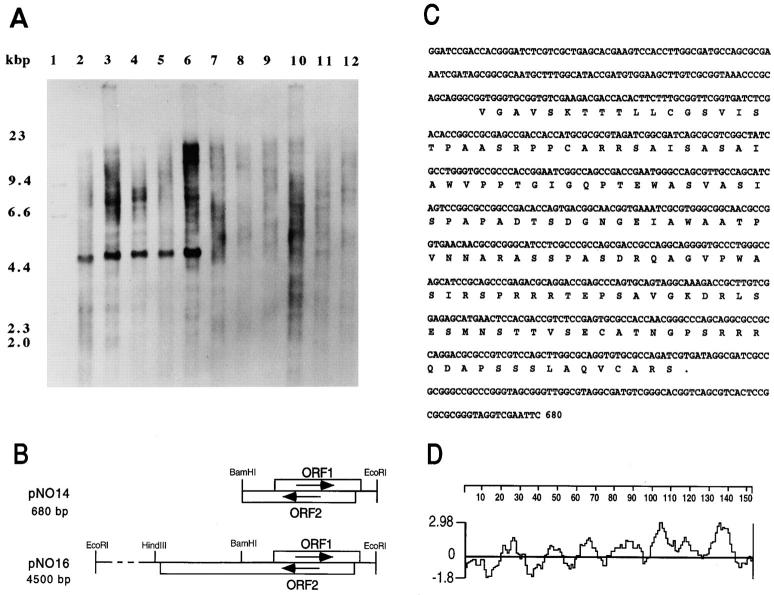

The cloned 680-bp fragment hybridized to genomes of the members of the M. tuberculosis complex. None of the other mycobacterial strains tested hybridized with this probe (Fig. 2 A). Thus, among mycobacteria, the cloned DNA appears to be specific for the members of the M. tuberculosis complex associated with human and rodent disease.

Figure 2.

Molecular analysis of the cloned DNA. (A) Presence of noxR1 in different species of mycobacteria. Chromosomal DNA (1 μg) of each strain was digested to completion with EcoRI and analyzed by Southern blotting with a digoxigenin-labeled probe corresponding to the 0.68-kb fragment from pNO14. Lane 1, Mr markers; lane 2, M. tuberculosis CB3.3; lane 3, M. tuberculosis H37Ra; lane 4, M. tuberculosis H37Rv; lane 5, M. bovis; lane 6, M. africanum; lane 7, M. gordonae; lane 8, M. fortuitum; lane 9, M. smegmatis; lane 10, M. avium; lane 11, M. intracellulare; lane 12, M. kansassi. (B) Map of the inserts in pNO14 and pNO16. (C) Nucleotide sequence of the NO14 fragment and amino acid sequence of the putative protein encoded by ORF1 (noxR1). These sequence data are available from the EMBL/GenBank/DDBJ under accession number Y08323. (D) Hydrophilicity plot of putative protein (NoxR1) encoded by ORF1.

Plasmid pNO14's 680-bp EcoRI/BamHI fragment from M. tuberculosis included two overlapping ORFs oriented in opposite directions (Fig. 2 B). ORF1 encodes a putative protein of 152 amino acids (Fig. 2 C) in an unusual pattern of alternating hydrophilic and hydrophobic segments that are shorter than typical membrane-spanning domains (Fig. 2 D). The putative protein was predicted to have an Mr of 15,514 daltons and a pI of 10.6, the basicity chiefly reflecting the relative abundance of Arg residues (9.2 mole percent). Despite the presence of four cysteines, no structural motifs were recognized, nor were there homologous sequences in the database. ORF2 did not contain a stop codon. Therefore, we isolated by colony hybridization a plasmid termed pNO16, which contained the full length ORF2, consisting of 1074 bases, from a library of M. tuberculosis CB3.3 (Fig. 2 B). The putative protein encoded in ORF2 is 40% identical to XP55, a Streptomyces lividans secretory product of unknown function (42).

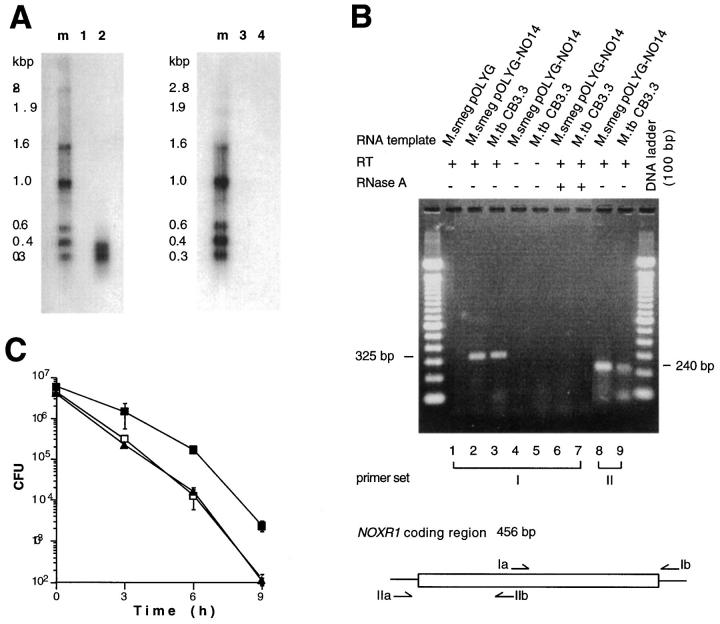

To find out which ORF was responsible for the observed phenotype, we determined which was transcribed in recombinant M. smegmatis. In Northern blots with an oligonucleotide specific for ORF1, an ∼400-bp transcript was detected in RNA purified from logarithmically growing M. smegmatis pOLYG–NO14 but not from M. smegmatis pOLYG (Fig. 3 A). In contrast, neither RNA preparation hybridized with an oligonucleotide specific for ORF2. Exposure of M. smegmatis pOLYG–NO14 and M. smegmatis pOLYG to ASN before extraction of their RNA did not alter the Northern blot results (data not shown), suggesting that ORF1 but not ORF2 was expressed during manifestation of the phenotype conferred by transformation with pOLYG–NO14. The gene corresponding to ORF1 was designated noxR1.

Figure 3.

Expression of recombinant noxR1 in M. smegmatis and native noxR1 in M. tuberculosis. (A) Northern blot. Total RNA (15 μg) from M. smegmatis pOLYG (lanes 1 and 3) and M. smegmatis pOLYG-NO14 (lanes 2 and 4) was probed with oligonucleotides specific for ORF1 (lanes 1 and 2) or ORF2 (lanes 3 and 4). (B) RT-PCR analysis. Total RNA from recombinant M. smegmatis strains (0.2 μg) and wild-type M. tuberculosis (1.0 μg) was analyzed by RT-PCR after amplification of cDNA with random hexamer primers. Primer sets I and II specific for noxR1-coding region are depicted. (C) Ablation of phenotype by introduction of stop codon in ORF1. E. coli HB101 were transformed with pBS (open squares), pNO14.1 (solid squares), or pNO14.1-mut1 (solid triangles), and the latter was mutated to introduce a stop at codon 12 in ORF1 without affecting ORF2, and all three recombinants were subjected to ASN.

Northern blots were negative when the noxR1 probe was applied to total RNA isolated from M. tuberculosis CB3.3. However, RT-PCR produced amplified products of the expected size (325 bp and 240 bp) with two different sets of primers specific for noxR1 mRNA (Fig. 3 B). Primers specific for ORF2 did not amplify any product (data not shown). No amplification occurred without RT or after adding RNAse A (Fig. 3 B), excluding the possibility that the products were amplified from genomic sequences. Thus, noxR1 is transcribed in M. tuberculosis.

To analyze the expression of NoxR1 protein, we prepared affinity-purified antibody against a recombinant fusion protein. noxR1 was cloned behind the inducible T5 promoter (pQE30–noxR1) and overexpressed in E. coli M15 pREP4 in fusion with a hexahistidine-containing tag. Attempts to force high-level expression in E. coli M15 via pQE30–noxR1 immediately led to inhibition of growth, and only a small amount of IPTG-induced product was recognizable by Coomassie blue staining of bacterial lysates separated by SDS-PAGE. Nevertheless, we were able to purify a single polypeptide by nickel column chromatography with the expected Mr (∼17 kD, based on the 15.5-kD deduced Mr of NoxR1 plus 1.1 kD for the fused tag). The purified protein was identified as NoxR1 by NH2-terminal amino acid sequencing, and no contaminating sequences were detected. The ostensibly pure NoxR1 was used to raise a rabbit antiserum. Antibody was affinity purified by subjecting chromatographically purified NoxR1 to SDS-PAGE and blotting NoxR1-containing gel slices to a nitrocellulose membrane, to which specific antibody was bound and eluted. The affinity-purified antibody did not detect any protein in E. coli HB101 dependent on transformation with pNO14. The techniques used for the immunoblot analysis may have been insufficiently sensitive to detect NoxR1 when it is expressed at low levels. Immunoblots were completely negative with M. smegmatis pOLYG-NO14 and M. tuberculosis CB3.3 (data not shown). We then tried to overexpress NoxR1 in M. smegmatis using the hsp60 promoter. As in E. coli, overexpression of the hsp60–noxR1 translational fusion impaired the growth of M. smegmatis (data not shown). Next, E. coli HB101 were transformed either with wild-type noxR1 or with a mutant in which a single bp change introduced a premature stop at codon 12 in ORF1, without affecting ORF2 (see Materials and Methods). Wild-type noxR1 encoded by pNO14.1, but not its ORF-1 mutant pNO14.1-mut1, protected the bacteria from ASN (Fig. 3 C). Thus, we have been able to detect, purify, and sequence NoxR1 protein only when a NoxR1 fusion was overexpressed in association with toxicity; we have not been able to detect NoxR1 protein under conditions where lower levels of expression were presumed and a phenotype was conferred. Nonetheless, translation of the noxR1 transcript appears to be required to confer resistance to ASN.

noxR1 also Confers Resistance to ROI and H+.

To more fully explore the phenotype afforded by expression of noxR1, we made use of a fluorescent, dye-reduction microplate assay whose results corresponded almost perfectly (correlation coefficients r2 >0.96) to the results of the more laborious colony-forming agar-plate assay after exposing bacteria to RNI in vitro or to the intraphagosomal milieu of macrophages (29). Not only was E. coli HB101 rendered far more resistant to ASN (2.5 mM NaNO2, pH 5) by expression of noxR1 (data not shown), but the bacteria also better resisted S-nitrosoglutathione (GSNO; 2 mM, pH 5.0), a physiologic and bacteriostatic (37, 43, 44) source of several RNI, including ammonia (45; Fig. 4, A and C). By 6 h, the survival advantage was close to 100-fold. GSNO was more bactericidal at pH 5.0 (Fig. 4, A and C) than at pH 7.0 (Fig. 4 E), but noxR1 conferred protection under both conditions.

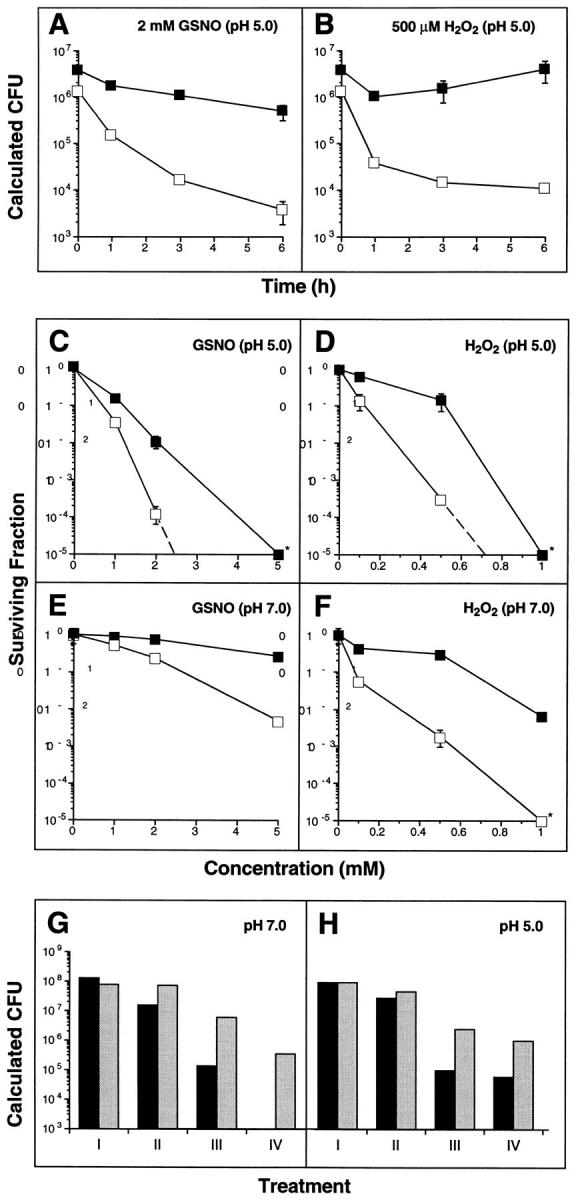

Figure 4.

Survival advantage conferred by noxR1 on E. coli cultured in GSNO and/or hydrogen peroxide. (A and B) Time course of survival of E. coli HB101 transformed with pBS (open squares) or pNO14 (solid squares) and cultured in LB at pH 5.0 with (A) 2 mM GSNO or (B) 0.5 mM H2O2, as determined by the dye reduction microplate assay. (C–F) Concentration-response curves for GSNO (C and E) and H2O2 (D and F) after 6 h incubation at a pH of 5 (C and D) or pH 7 (E and F). (G and H) Resistance to the combination of GSNO and H2O2. (Black bars) E. coli HB101 transformed with pBS. (Gray bars) E. coli HB101 transformed with pNO14. (G) pH 7.0 with the following treatments: I, none; II, H2O2 (0.1 mM); III, GSNO (5 mM); IV, H2O2 (0.05 mM) + GSNO (5 mM). (H) pH 5.0 with the following treatments: I, none; II, H2O2 (0.1 mM); III, GSNO (1 mM); IV, H2O2 (0.05 mM) + GSNO (1 mM). Data in panels A–F are means ± SE for triplicates; some error bars fall within the symbols. Data in panels G and H are means of duplicates.

Unexpectedly, noxR1 also conferred resistance to H2O2 (survival advantage, >100-fold) by 6 h, and in this case H+ also appeared to show a small synergistic effect on the killing (pH 5.0, Fig. 4, B and D; pH 7.0, Fig. 4 F). Furthermore, noxR1 protected E. coli from the synergistic cytotoxicity afforded by GSNO plus H2O2 at concentrations of each agent that were harmless singly (Fig. 4 G), and from the cytotoxicity afforded by the combination of three species likely to be simultaneously present in some phagosomes: GSNO, H2O2, and H+ (Fig. 4 H).

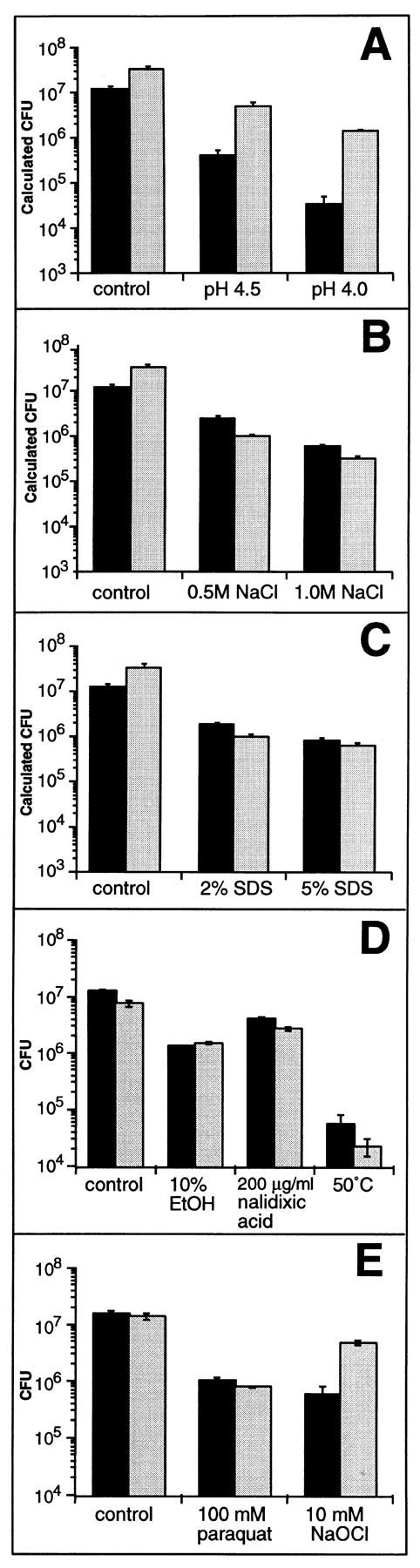

The results to this point did not allow us to distinguish whether noxR1 might protect relatively specifically against RNI and ROI, or might instead confer a general survival or repair function effective against virtually any threat to bacterial viability. The distinction can be hard to draw, since so many forms of insult, such as heat shock and ultraviolet irradiation, lead directly or indirectly to formation of ROI. Nevertheless, we subjected noxR1- and vector-transformed E. coli to several other stresses: elevated concentrations of H+, sodium chloride, detergent, ethanol, nalidixic acid, paraquat, hypochlorous acid, and heat. noxR1 did confer relative resistance to acid at pH 4.5, the lowest level reported in phagosomes (46) as well as at pH 4.0 (Fig. 5 A). At pH 5 and above, no growth inhibition was detectable (Fig. 1 B and data not shown). In addition, noxR1 protected E. coli against killing by hypochlorous acid (10 mM). In contrast, noxR1 afforded no protection against the growth-inhibiting effects of high salt, SDS, heat, ethanol, nalidixic acid, or paraquat (Fig. 5, B–E).

Figure 5.

Effect of transformation with noxR1 on resistance of E. coli to various stress conditions. Survival of E. coli HB101 transformed with pBS (black bars) or pNO14 (gray bars) after 3 or 6 h incubation in LB medium with the following treatments: (A) LB at pH 4.5 and pH 4.0 for 3 h; (B) addition of 0.5 M and 1.0 M NaCl for 3 h; (C) addition of 2 and 5% SDS for 3 h; (D) addition of 10% ethanol or 200 μg/ml nalidixic acid for 6 h or incubation at 50°C for 3 h; (E) addition of 100 mM paraquat for 6 h or 10 mM NaOCl for 3 h. Control bars reflect growth at pH 7.0. Survival was quantified by plating appropriate dilutions on LB agar or by a dye reduction microplate assay (see Materials and Methods). Results are means ± SE for triplicates.

Independence of noxR1 Effects from the oxyR and soxRS Regulons.

oxyR and soxRS are multigenic regulons (25), each of which is activated by and confers resistance to both ROI and RNI in E. coli (47–49). In M. tuberculosis, oxyR is disrupted and soxRS is undescribed (9, 10, 50, 51), whereas in E. coli neither regulon contains any sequence homologous to noxR1. Nonetheless, we wished to test whether noxR1 from M. tuberculosis might function in recombinant E. coli through activation of oxyR or soxRS. The genes controlled by these factors number at least 19, including those encoding superoxide dismutase, NADPH:ferredoxin oxidoreductase, fumarase, DNA repair endonuclease IV, catalase, alkylhydroperoxide reductase, and glutathione reductase. Accordingly, we transformed E. coli deficient in either of these two regulons and their corresponding wild-type strains with pNO14 or pBS vector alone. In all four hosts, noxR1 conferred resistance to ASN (Fig. 6). The degree of protection depended on the host cell type, but not on its expression of oxyR or soxRS. Thus, genes dependent upon oxyR or soxRS are dispensable for the function of noxR1, unless noxR1 can substitute for oxyR or soxRS to induce their expression.

Figure 6.

noxR1–mediated resistance to ASN is independent of oxyR and soxRS. Survival of the following E. coli hosts transformed with pBS (open squares) or pNO14 (solid squares) in ASN medium: (A) JTG100 (oxyR wild type); (B) JTG101 (oxyR deficient); (C) GC4468 (soxRS wild type); (D) DJ901 (soxRS deficient). Overnight cultures were diluted 100-fold into LB pH 5.0 containing 10 mM NaNO2 and incubated at 37°C. Resistance was quantified by a dye reduction microplate assay (see Materials and Methods). Results are means ± SE for triplicates; some error bars fall within the symbols.

Effect of noxR1 on Survival of M. smegmatis within Macrophages.

The observation that noxR1 protects M. smegmatis from the antibacterial effects of RNI and ROI in vitro prompted us to explore the effect of this gene on the survival of M. smegmatis inside activated macrophages, where the full complement of antibacterial mechanisms is undefined.

Macrophages were collected from the peritoneal cavity of mice 4 d after intraperitoneal injection of sodium periodate (52). Periodiate, a lymphocyte mitogen, stimulates cytokine production (53). Macrophages from periodate-injected mice have a respiratory burst capacity typical of macrophages activated by infection of the host with mycobacteria (54) or macrophages treated in vitro with cytokines (55). Periodate-elicited macrophages respond to further inductive signals, such as in vitro incubation with IFN-γ, by producing NO (33). Both properties were confirmed in wild-type macrophages in this experiment; in addition, M. smegmatis alone was sufficient to trigger NO production in periodate-elicited macrophages without exposure to exogenous cytokines in vitro (Fig. 7, insets).

To vary the genotype of the macrophages along with that of the mycobacteria, wild-type mice of C57BL/6x129/ SvEv background were matched with NOS2-deficient mice on the same background (31). Similarly, wild-type C57BL/6 mice were compared with Phox91-deficient (respiratory burst, oxidase-null) mice backcrossed to C57BL/6. As expected, H2O2 production was preserved and NO production was abolished in macrophages from NOS2-deficient mice, while the reverse was the case in macrophages from Phox91-deficient mice; neither class of knock-out macrophages overproduced the opposite product (Shiloh, M.U., unpublished data). In all settings described below, results were similar with or without addition of exogenous IFN-γ to the already activated macrophages (data not shown), and have been pooled.

On average, activated macrophages from wild-type C57BL/ 6x129/SvEv mice killed 80% of ingested pOLYG-transformed (control) M. smegmatis by 5.6 h and 97% by 24 h (Fig. 7 A; interpolation from data in Table 1). When M. smegmatis was transformed with noxR1, it took the wild-type macrophages twofold longer to kill 80% of them. Moreover, at each time point tested (6, 12, and 24 h), approximately twofold more bacteria survived (Fig. 7 A; Table 1).

Table 1.

Percentage of Survival of Vector- or noxR1-transformed M. smegmatis after the Indicated Time Periods Compared to their CFU at Time 0 in Mouse Macrophages

| Mouse genotype | Number of Exp. | Time | Surviving vector- transformed M. smegmatis * (± SE) | Surviving noxR1- transformed M. smegmatis ‡ (± SE) | P § | Fold protection‖ (± SE) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| h | ||||||||||||

| C57BL/6x | 6 | 6 | 14.2 (1.9) | 28.3 (3.7) | <.005 | 2.03 (0.21) | ||||||

| 129Sv/Ev | 12 | 9.7 (1.5) | 18.3 (2.5) | <.01 | 1.97 (0.21) | |||||||

| 24 | 2.8 (0.4) | 5.2 (0.3) | <.0001 | 2.06 (0.29) | ||||||||

| iNOS−/− | 6 | 6 | 19.0 (3.6) | 29.9 (5.3) | >.05 | 1.56 (0.08) | ||||||

| 12 | 14.0 (2.6) | 24.9 (4.5) | <.05 | 1.56 (0.14) | ||||||||

| 24 | 4.1 (0.7) | 7.0 (1.0) | <.05 | 1.71 (0.20) | ||||||||

| C57BL/6 | 6 | 6 | 32.1 (3.1) | 49.8 (3.8) | <.001 | 1.61 (0.16) | ||||||

| 12 | 21.0 (2.8) | 38.9 (4.1) | <.001 | 2.06 (0.14) | ||||||||

| 24 | 6.7 (1.2) | 15.8 (2.8) | <.01 | 2.49 (0.33) | ||||||||

| Phox91−/− | 6 | 6 | 84.2 (9.1) | 110.0 (8.3) | <.05 | 1.42 (0.18) | ||||||

| 12 | 61.9 (4.7) | 96.4 (4.2) | <.0001 | 1.67 (0.20) | ||||||||

| 24 | 22.0 (3.3) | 39.1 (3.7) | <.005 | 1.93 (0.27) |

Means ± SE for the number of independent experiments indicated, each in triplicate. The number of CFUs per well at time 0 (see Materials and Methods) was defined as 100%, and averaged 2 × 105, or ∼1/macrophage.

* M. smegmatis transformed with pOLYG vector alone.

‡ M. smegmatis transformed with pOLYG–NO14.

Two-tailed Student's t test.

The percentage of surviving M. smegmatis pOLYG–NO14 divided by the percentage of surviving M. smegmatis pOLYG at each time point was calculated for each experiment and averaged.

Macrophages that were genetically incapable of expressing NOS2 (31) were no less efficient at killing M. smegmatis than wild-type macrophages of the same genetic background. 80% of the bacteria were killed by 6 h and 96% were killed by 24 h. (Fig. 7 B; Table 1). This indicated that RNI do not play a major role in the control of M. smegmatis in vitro, in contrast to the situation with M. tuberculosis (see references 16 and 17, and the references cited therein) and M. leprae (56). Nonetheless, expression of noxR1 protected the bacteria, delaying the time of 80% killing by a factor of 2.7-fold and resulting in 1.6–1.7-fold more surviving organisms at each time point tested (Table 1). This indicated that the protective action of noxR1 is not directed exclusively against RNI, consistent with the evidence in vitro showing that noxR1 also protects against ROI.

Wild-type C57BL/6 macrophages killed wild-type (pOLYG-transformed) M. smegmatis more slowly (80% killing by 12.5 h) than did wild-type C57BL/6x129/SvEv macrophages (80% killing by 5.6 h). Nonetheless, expression of noxR1 in M. smegmatis delayed the 80% killing time by a factor of 1.75-fold and resulted in 1.6–2.5-fold more surviving organisms at each time point tested (Fig. 7 C; Table 1).

C57BL/6 macrophages deficient in Phox91 were strikingly impaired in killing wild-type M. smegmatis; within the 24 h period of observation, 80% killing was not often attained (Fig. 7 D; Table 1). This indicated that ROI play a prominent, albeit not an exclusive, role in killing M. smegmatis, in contrast to the situation with M. tuberculosis, where a minimal role for ROI was evident (16). In ROI-deficient macrophages, M. smegmatis that expressed noxR1 survived 1.4–1.9-fold better than vector-transformed M. smegmatis at each time point tested (Fig. 7 D; Table 1). These findings suggested that ROI and another product represent redundant killing mechanisms for M. smegmatis, the former more effectively than the latter; in the absence of ROI, less potent killing by RNI, H+, or another product is manifest, against which noxR1 affords protection.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study of macrophage– pathogen interactions in which both the macrophages and the pathogens have been genetically modified, such that the host cells do or do not express specific cytotoxic mechanisms, and the bacteria do or do not express a presumptive resistance pathway directed against those mechanisms. By this analysis, noxR1, a novel gene from M. tuberculosis, confers partial resistance to three of the major antimicrobial products of macrophages, the cells ultimately responsible for controlling tuberculosis. However, the greater resistance conferred on noxR1-transformed M. smegmatis in vitro than in macrophages strongly suggests that there are macrophage antimycobacterial products other than RNI, ROI, and H+, and that noxR1 protects against some physiologically relevant stresses but not others. Likewise, the relative selectivity of noxR1's protective effects in vitro and the restriction of the noxR1 gene to a subset of pathogenic mycobacterial species argue that noxR1 is neither a general stress resistance gene nor a housekeeping gene.

Cloned from a prevalent clinical isolate of M. tuberculosis, noxR1 was only identified in the genome of members of the M. tuberculosis complex. noxR1 was absent from the chromosome of mycobacteria considered nonpathogenic or opportunistically pathogenic for humans, including M. smegmatis, M. avium, and M. intracellulare. We do not know if a noxR1-like gene is present in any other organisms, nor whether noxR1 is transcribed naturally by any mycobacteria besides the M. tuberculosis strain we tested. It remains to be determined whether the natural gene may be regulated by environmental conditions, including the stresses against which it confers resistance. It would be of particular relevance to know how much NoxR1 is expressed by M. tuberculosis that resides in phagolysosomes.

A major mystery is noxR1's mechanism of action. With no homologies or motifs recognized at nucleotide or amino acid levels, the sequence afforded few clues. Because so little NoxR1 appears to be expressed, it is unlikely that its four cysteine residues merely serve to titrate ROI or RNI, as homocysteine is thought to do in Salmonella typhimurium (44), or as metallothionein may do when overexpressed in hepatocytes (57). In E. coli, the DNA-binding protein encoded by dps protects DNA from oxidative damage (58, 59), and noxR1 might work in a similar manner. Its effectiveness in a heterologous mycobacterium whose genome lacks noxR1 may argue against a role as a transcription factor, and its effectiveness in oxyR- and soxRS-deficient E. coli argues against noxR1 activating those two regulons in particular. The oxyR homolog of M. tuberculosis contains numerous deletions and frameshifts and is nonfunctional (9, 60). Perhaps NoxR1 compensates for the loss of OxyR in M. tuberculosis, similar to the suggested role of AhpC (10, 50).

If NoxR1 is an enzyme, the novelty of its sequence suggests that it may work differently than those already known to affect RNI. The latter serve to alter the proportions of various RNI in a mixture. Thus, in vitro, mammalian thioredoxin reductase can catalyze the NADPH-dependent reduction of S-nitrosoglutathione to glutathione and an NO-like species (61), whereas superoxide dismutase favors the accumulation of NO at the expense of its conversion to peroxynitrite. At present, the yield of recombinant NoxR1 has been compromised by its apparent autotoxicity upon overexpression, and this has precluded biochemical assays of hypothesized actions.

The physiologic role of NoxR1 cannot be established until it is possible to inactivate noxR1 selectively in M. tuberculosis and compare the growth of the organism in the mammalian host with the growth of isogenic M. tuberculosis to which noxR1 has been restored. Until then, the possibility remains that the actions of noxR1 observed in transformed bacteria are artefacts of over or heterologous expression. Weighing against this concern is that noxR1 conferred a protective phenotype only when expressed at low levels, and did so in diverse species and strains.

There is an urgent need for new antitubercular drugs. Almost all currently used antibacterials manifest their antibacterial activity in pure culture, and new candidates are screened on that basis. Such screens could miss compounds that inhibit a pathway which is dispensable for bacterial growth in vitro but which confers a survival advantage on the pathogen within the infected host. In this sense, inhibitors of NoxR1 may warrant investigation as possible prototypes of a new class of antiinfectious agents.

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Dinauer for phox91-deficient breeders; J. MacMicking for preliminary experiments with recombinant E. coli in macrophages; A. Nunoshiba, B. Demple, P. O'Gaora, and D.B. Young for bacterial strains; F. Fang for helpful comments; D. Schnappinger for fruitful discussions; Genentech, Inc. (South San Francisco, CA) for recombinant mouse IFN-γ; and Stuart Shuman for access to equipment.

Footnotes

This work was funded by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant HL-51967 to L.W. Riley and C. Nathan; by a German Cancer Research Center fellowship to S. Ehrt; by a Richard Lounsbery Foundation fellowship to J. Ruan; and by NIH Medical Scientist Training Program grant GM-07739(MS) to M. Shiloh. We also acknowledge financial support from the Auxiliary of the Society of the New York Hospital for computer equipment.

Abbreviations used in this paper: ASN, acidified sodium nitrite; GSNO, S-nitrosoglutathione; LB, Luria-Bertani; NADPH, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (reduced); NO, nitric oxide; NOS2, nitric oxide synthase type 2; ORF, open reading frame; pBS, pBluescript; RNI, reactive nitrogen intermediates; ROI, reactive oxygen intermediates; RT, reverse transcriptase.

C. Nathan and L.W. Riley contributed equally to this study.

References

- 1.Raviglione MC, Snider DE, Jr, Kochi A. Global epidemiology of tuberculosis. Morbidity and mortality of a worldwide epidemic. JAMA (J Am Med Assoc) 1995;273:220–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chan J, Tian Y, Tanaka KE, Tsang MS, Yu K, Salgame P, Carroll D, Kress Y, Teitelbaum R, Bloom BR. Effects of protein malnutrition on tuberculosis in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:14857–14861. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Daley CL, Small PM, Schecter GF, Schoolnik GK, McAdam RA, Jacobs WR, Jr, Hopewell PC. An outbreak of tuberculosis with accelerated progression among persons infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. An analysis using restriction-fragment-length polymorphisms. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:231–235. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199201233260404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nathan CF. Mechanisms of macrophage antimicrobial activity. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1983;77:620–630. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(83)90190-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nathan CF, Hibbs JB., Jr Role of nitric oxide synthesis in macrophage antimicrobial activity. Curr Opin Immunol. 1991;3:65–70. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(91)90079-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Butler AR, Flitney FW, Williams DL. NO, nitrosonium ions, nitroxide ions, nitrosothiols and iron-nitrosyls in biology: a chemist's perspective. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1995;16:18–22. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)88968-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Groote MA, Fang FC. NO inhibitions: antimicrobial properties of nitric oxide. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;21:162–165. doi: 10.1093/clinids/21.supplement_2.s162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neill MA, Klebanoff SJ. The effect of phenolic glycolipid-1 from Mycobacterium lepraeon the antimicrobial activity of human macrophages. J Exp Med. 1988;167:30–42. doi: 10.1084/jem.167.1.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sherman DR, Sabo PJ, Hickey MJ, Arain TM, Mahairas GG, Yuan Y, Barry CE, III, Stover CK. Disparate responses to oxidative stress in saprophytic and pathogenic mycobacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:6625–6629. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.14.6625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sherman DR, Mdluli K, Hickey MJ, Arain TM, Morris SL, Barry CE, III, Stover CK. Compensatory ahpC gene expression in isoniazid-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. . Science. 1996;272:1641–1643. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5268.1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dumarey CH, Labrousse V, Rastogi N, Vargaftig BB, Bachelet M. Selective Mycobacterium avium–induced production of nitric oxide by human monocyte-derived macrophages. J Leukocyte Biol. 1994;56:36–40. doi: 10.1002/jlb.56.1.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang Y, Garcia MJ, Lathigra R, Allen B, Moreno C, van Embden JD, Young D. Alterations in the superoxide dismutase gene of an isoniazid-resistant strain of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. . Infect Immun. 1992;60:2160–2165. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.6.2160-2165.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chan, J., and S.H.E. Kaufmann. 1994. Immune mechanisms of protection. In Tuberculosis: Pathogenesis, Protection and Control. B.R. Bloom, editor. American Society for Microbiology, Washington. 389–415.

- 14.Schlesinger LS, Bellinger-Kawahara CG, Payne NR, Horwitz MA. Phagocytosis of Mycobacterium tuberculosisis mediated by human monocyte complement receptors and complement component C3. J Immunol. 1990;144:2771–2780. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wright SD, Silverstein SC. Receptors for C3b and C3bi promote phagocytosis but not the release of toxic oxygen from human phagocytes. J Exp Med. 1983;158:2016–2023. doi: 10.1084/jem.158.6.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chan J, Xing Y, Magliozzo RS, Bloom BR. Killing of virulent Mycobacterium tuberculosisby reactive nitrogen intermediates produced by activated murine macrophages. J Exp Med. 1992;175:1111–1122. doi: 10.1084/jem.175.4.1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.MacMicking JD, North RJ, LaCourse R, Mudgett JS, Shah SK, Nathan CF. Identification of NOS2as a protective locus against tuberculosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:5243–5248. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.5243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nicholson, S., M. da G. Bonecini-Almeida, J.R. Lapa e Silva, C. Nathan, Q.W. Xie, R. Mumford, J.R. Weidner, J. Calaycay, J. Geng, N. Boechat, et al. 1996. Inducible nitric oxide synthase in pulmonary alveolar macrophages from patients with tuberculosis. J. Exp. Med. 183:2293–2302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Nozaki Y, Hasegawa Y, Ichiyama S, Nakashima I, Shimokata K. Mechanism of nitric oxide-dependent killing of Mycobacterium bovisBCG in human alveolar macrophages. Infect Immun. 1997;65:3644–3647. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.9.3644-3647.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Doi T, Ando M, Akaike T, Suga M, Sato K, Maeda H. Resistance to nitric oxide in Mycobacterium aviumcomplex and its implication in pathogenesis. Infect Immun. 1993;61:1980–1989. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.5.1980-1989.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O'Brien L, Carmichael J, Lowrie DB, Andrew PW. Strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosisdiffer in susceptibility to reactive nitrogen intermediates in vitro. Infect Immun. 1994;62:5187–5190. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.11.5187-5190.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Friedman CR, Stoeckle MY, Kreiswirth BN, Johnson WD, Jr, Manoach SM, Berger J, Sathianathan K, Hafner A, Riley LW. Transmission of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in a large urban setting. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;152:355–359. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.152.1.7599845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Friedman C, Quinn GC, Kreiswirth BN, Perlman DC, Salomon N, Schluger N, Lutfey M, Berger J, Poltoratskaia N, Riley LW. Widespread dissemination of a single drug–susceptible strain of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. . J Infect Dis. 1997;176:478–484. doi: 10.1086/514067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Snapper SB, Melton RE, Mustafa S, Kieser T, Jacobs WR., Jr Isolation and characterization of efficient plasmid transformation mutants of Mycobacterium smegmatis. . Mol Microbiol. 1990;4:1911–1919. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb02040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Greenberg JT, Monach P, Chou JH, Josephy PD, Demple B. Positive control of a global antioxidant defense regulon activated by superoxide-generating agents in Escherichia coli. . Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:6181–6185. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.16.6181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Greenberg JT, Demple B. Overproduction of peroxide-scavenging enzymes in Escherichia colisuppresses spontaneous mutagenesis and sensitivity to redox-cycling agents in oxyR-mutants. EMBO (Eur Mol Biol Organ) J. 1988;7:2611–2617. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03111.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garbe TR, Barathi J, Barnini S, Zhang Y, Abou-Zeid C, Tang D, Mukherjee R, Young DB. Transformation of mycobacterial species using hygromycin resistance as selectable marker. Microbiology (Reading) 1994;140:133–138. doi: 10.1099/13500872-140-1-133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Soolingen D, Hermans PW, de Haas PE, Soll DR, van Embden JD. Occurrence and stability of insertion sequences in Mycobacterium tuberculosiscomplex strains: evaluation of an insertion sequence-dependent DNA polymorphism as a tool in the epidemiology of tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:2578–2586. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.11.2578-2586.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shiloh MU, Ruan J, Nathan C. Evaluation of bacterial numbers and phagocyte function with a fluorescence-based microplate assay. Infect Immun. 1997;65:3193–3197. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.8.3193-3198.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Buchmeier N, Heffron F. Intracellular survival of wild-type Salmonella typhimuriumand macrophage-sensitive mutants in diverse populations of macrophages. Infect Immun. 1989;57:1–7. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.1.1-7.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.MacMicking, J.D., C. Nathan, G. Hom, N. Chartrain, D.S. Fletcher, M. Trumbauer, K. Stevens, Q.W. Xie, K. Sokol, N. Hutchinson, et al. 1995. Altered responses to bacterial infection and endotoxic shock in mice lacking inducible nitric oxide synthase. Cell. 81:641–650 (see erratum Cell. 1995. 81: 1171). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Pollock JD, Williams DA, Gifford MA, Li LL, Du X, Fisherman J, Orkin SH, Doerschuk CM, Dinauer MC. Mouse model of X-linked chronic granulomatous disease, an inherited defect in phagocyte superoxide production. Nat Genet. 1995;9:202–209. doi: 10.1038/ng0295-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ding AH, Nathan CF, Stuehr DJ. Release of reactive nitrogen intermediates and reactive oxygen intermediates from mouse peritoneal macrophages: comparison of activating cytokines and evidence for independent production. J Immunol. 1988;141:2407–2412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.De la Harpe J, Nathan CF. A semi-automated micro-assay for H2O2release by human blood monocytes and mouse peritoneal macrophages. J Immunol Methods. 1985;78:323–336. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(85)90089-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stuehr DJ, Nathan CF. Nitric oxide. A macrophage product responsible for cytostasis and respiratory inhibition in tumor target cells. J Exp Med. 1989;169:1543–1555. doi: 10.1084/jem.169.5.1543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Taylor TWJ, Wignall EW, Cowley JF. The decomposition of nitrous acid in aqueous solutions. J Chem Soc (Lond) 1927;11:1923. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morris SL, Hansen JN. Inhibition of Bacillus cereusspore outgrowth by covalent modification of a sulfhydryl group by nitrosothiol and iodoacetate. J Bacteriol. 1981;148:465–471. doi: 10.1128/jb.148.2.465-471.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stamler JS. S-nitrosothiols and bioregulatory actions of nitrogen oxides through reactions with thiol groups. Curr Topics Microbiol Immunol. 1995;196:19–36. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-79130-7_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stamler JS, Singel DJ, Loscalzo J. Biochemistry of nitric oxide and its redox-activated forms. Science. 1992;258:1898–1902. doi: 10.1126/science.1281928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dykhuizen RS, Frazer R, Duncan C, Smith CC, Golden M, Benjamin N, Leifert C. Antimicrobial effect of acidified nitrite on gut pathogens: importance of dietary nitrate in host defense. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:1422–1425. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.6.1422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sturgill-Koszycki S, Schlesinger PH, Chakraborty P, Haddix PL, Collins HL, Fok AK, Allen RD, Gluck SL, Heuser J, Russell DG. Lack of acidification in Mycobacteriumphagosomes produced by exclusion of the vesicular proton-ATPase. Science. 1994;263:678–681. doi: 10.1126/science.8303277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Burnett WV, Henner J, Eckhardt T. The nucleotide sequence of the gene coding for XP55, a major secreted protein from Streptomyces lividans. . Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15:3926. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.9.3926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.De Groote MA, Granger D, Xu Y, Campbell G, Prince R, Fang FC. Genetic and redox determinants of nitric oxide cytotoxicity in a Salmonella typhimuriummodel. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:6399–6403. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.14.6399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.De Groote MA, Testerman T, Xu Y, Stauffer G, Fang FC. Homocysteine antagonism of nitric oxide-related cytostasis in Salmonella typhimurium. . Science. 1996;272:414–417. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5260.414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lewis RS, Tamir S, Tannenbaum SR, Deen WM. Kinetic analysis of the fate of nitric oxide synthesized by macrophages in vitro. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:29350–29355. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.49.29350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ohkuma S, Poole B. Fluorescence probe measurement of the intralysosomal pH in living cells and the perturbation of pH by various agents. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1978;75:3327–3331. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.7.3327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hausladen A, Privalle CT, Keng T, Deangelo J, Stamler JS. Nitrosative stress: activation of the transcription factor OxyR. Cell. 1996;86:719–729. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80147-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nunoshiba T, DeRojas-Walker T, Tannenbaum SR, Demple B. Roles of nitric oxide in inducible resistance of Escherichia colito activated macrophages. Infect Immun. 1995;63:794–798. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.3.794-798.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nunoshiba T, DeRojas-Walker T, Wishnok JS, Tannenbaum SR, Demple B. Activation by nitric oxide of an oxidative-stress response that defends Escherichia coliagainst activated macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:9993–9997. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.21.9993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dhandayuthapani S, Zhang Y, Mudd MH, Deretic V. Oxidative stress response and its role in sensitivity to isoniazid in mycobacteria: characterization and inducibility of ahpC by peroxides in Mycobacterium smegmatis and lack of expression in M. aurum and M. tuberculosis. . J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3641–3649. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.12.3641-3649.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang Y, Dhandayuthapani S, Deretic V. Molecular basis for the exquisite sensitivity of Mycobacterium tuberculosisto isoniazid. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:13212–13216. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.23.13212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Weinberg JB, Hibbs JB., Jr In vitro modulation of macrophage tumoricidal activity: partial characterization of a macrophage-activating factor(s) in supernatants of NaIO4-treated cells. J Reticuloendothel Soc. 1979;26:283–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Novogrodsky A. Selective activation of mouse T and B lymphocytes by periodate, galactose oxidase and soybean agglutinin. Eur J Immunol. 1974;4:646–648. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830041003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nathan CF, Root RK. Hydrogen peroxide release from mouse peritoneal macrophages: dependence on sequential activation and triggering. J Exp Med. 1977;146:1648–1662. doi: 10.1084/jem.146.6.1648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nathan CF, Murray HW, Wiebe ME, Rubin BY. Identification of interferon-γ as the lymphokine that activates human macrophage oxidative metabolism and antimicrobial activity. J Exp Med. 1983;158:670–689. doi: 10.1084/jem.158.3.670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Adams LB, Franzblau SG, Vavrin Z, Hibbs JBJ, Krahenbuhl JL. l-Arginine–dependent macrophage effector functions inhibit metabolic activity of Mycobacterium leprae. . J Immunol. 1991;147:1642–1646. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schwarz MA, Lazo JS, Yalowich JC, Allen WP, Whitemore M, Bergonia HA, Tzeng E, Billiar TR, Robbins PD, Lancaster JRJ, Pitt BR. Metallothionein protects against the cytotoxic and DNA-damaging effects of nitric oxide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:4452–4456. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.10.4452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Almiron M, Link AJ, Furlong D, Kolter R. A novel DNA-binding protein with regulatory and protective roles in starved Escherichia coli. . Genes Dev. 1992;6:2646–2654. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.12b.2646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Altuvia S, Almiron M, Huisman G, Kolter R, Storz G. The dps promoter is activated by OxyR during growth and by IHF and sigma S in stationary phase. Mol Microbiol. 1994;13:265–272. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00421.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Deretic V, Philipp W, Dhandayuthapani S, Mudd MH, Curcic R, Garbe T, Heym B, Via LE, Cole ST. Mycobacterium tuberculosisis a natural mutant with an inactivated oxidative-stress regulatory gene: implications for sensitivity to isoniazid. Mol Microbiol. 1995;17:889–900. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_17050889.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nikitovic D, Holmgren A. S-nitrosogluthathione is cleaved by thioredoxin system with liberation of glutathione and redox regulating nitric oxide. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:19180–19185. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.32.19180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]