Abstract

The small guanosine triphosphatase Rab7 regulates late endocytic trafficking. Rab7-interacting lysosomal protein (RILP) and oxysterol-binding protein–related protein 1L (ORP1L) are guanosine triphosphate (GTP)–Rab7 effectors that instigate minus end–directed microtubule transport. We demonstrate that RILP and ORP1L both interact with the group C adenovirus protein known as receptor internalization and degradation α (RIDα), which was previously shown to clear the cell surface of several membrane proteins, including the epidermal growth factor receptor and Fas (Carlin, C.R., A.E. Tollefson, H.A. Brady, B.L. Hoffman, and W.S. Wold. 1989. Cell. 57:135–144; Shisler, J., C. Yang, B. Walter, C.F. Ware, and L.R. Gooding. 1997. J. Virol. 71:8299–8306). RIDα localizes to endocytic vesicles but is not homologous to Rab7 and is not catalytically active. We show that RIDα compensates for reduced Rab7 or dominant-negative (DN) Rab7(T22N) expression. In vitro, Cu2+ binding to RIDα residues His75 and His76 facilitates the RILP interaction. Site-directed mutagenesis of these His residues results in the loss of RIDα–RILP interaction and RIDα activity in cells. Additionally, expression of the RILP DN C-terminal region hinders RIDα activity during an acute adenovirus infection. We conclude that RIDα coordinates recruitment of these GTP-Rab7 effectors to compartments that would ordinarily be perceived as early endosomes, thereby promoting the degradation of selected cargo.

Introduction

The endocytic pathway contributes to the determination of plasma membrane receptor homeostasis by maintaining a balance between cell surface recycling and intracellular redistribution to lysosomes or other organelles. Members of the Rab family of small GTPases are essential determinants of trafficking outcomes. GTP-Rabs coordinate distinct trafficking steps by recruiting specific effector proteins. Rab effectors facilitate an array of processes, including vesicle formation, motility, and target organelle tethering and fusion (Stenmark and Olkkonen, 2001; Grosshans et al., 2006). The GTPase cycle is obligatory for proper Rab function because mutants that fail to bind, hydrolyze, or exchange nucleotides generally confer dominant phenotypes (Feng et al., 1995).

Adenoviruses are nonenveloped icosahedral DNA viruses that replicate and assemble in the host cell nucleus (Ginsberg, 1999). The adenovirus genome is divided into early genes involved in DNA synthesis, transcription, transport of viral mRNAs, and immunomodulation and late genes coding for structural proteins. Proteins encoded by the early region 3 (E3) are not required for replication but contribute to the viral life cycle by altering the trafficking and function of cellular proteins involved in adaptive immunity and inflammatory responses (Lichtenstein et al., 2004b). The adenovirus receptor internalization and degradation (RID) complex encoded by E3 modulates trafficking of several cell surface receptors (Horwitz, 2004). RID is composed of two α subunits (formerly E3-13.7 or E3-10.4) and one β subunit (formerly E3-14.5). RIDα was initially discovered based on its ability to induce down-regulation of the EGF receptor (EGFR) in the absence of ligand (Carlin et al., 1989). Subsequent studies demonstrated that the RID complex (RIDα/β) mediates the cell surface removal of TNF receptor 1 (TNFR1; Fessler et al., 2004), TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand receptor 1 (TRAIL-R1; Tollefson et al., 2001), and Fas (Shisler et al., 1997; Elsing and Burgert, 1998; Tollefson et al., 1998). In conjunction with E3-6.7K, RIDα/β also reduces the cell surface expression of TRAIL-R2 (Lichtenstein et al., 2004a). The down-regulation of TNFR1, TRAIL-R1, TRAIL-R2, and Fas prevents apoptotic and inflammatory responses that normally result from exposure to the respective ligands (Tollefson et al., 1998, 2001; McNees et al., 2002; Fessler et al., 2004; Lichtenstein et al., 2004a). EGFR down-regulation may reduce cellular release of the neutrophil chemoattractant interleukin-8 (Mascia et al., 2003; and unpublished data). The combined activity of E3 proteins allows for immune evasion of adenovirus-infected cells during acute infections. Induction of the E3 promoter during T cell activation in the absence of E1A expression suggests that E3 proteins also contribute to the establishment and maintenance of persistent or latent infections (Horvath et al., 1986; Garnett et al., 2002).

Degradative endocytic trafficking is a dynamic process consisting of early and late stages that generally correlate with microtubule-dependent movement toward the interior of the cell. Early stages are regulated by Rab5, and the acquisition of Rab7 is considered to be a critical checkpoint in the determination of a degradative versus recycling fate. Late endocytic trafficking, including ligand-dependent EGFR degradation, is dependent on Rab7 (Feng et al., 1995; Vitelli et al., 1997; Ceresa and Bahr, 2006). Rab7 additionally participates in several related processes, including autophagy (Gutierrez et al., 2004), melanosome trafficking (Gomez et al., 2001), and phagosome maturation (Roberts et al., 2006). To date, the known GTP-Rab7 effector proteins are Rab7-interacting lysosomal protein (RILP; Cantalupo et al., 2001), oxysterol-binding protein–related protein 1L (ORP1L; Johansson et al., 2005), Rabring7 (Mizuno et al., 2003), the hVPS34/p150 phosphatidylinositol (PtdIns) 3-kinase complex (Stein et al., 2003), and the α-proteasome subunit XAPC7 (Dong et al., 2004). RILP and ORP1L facilitate the recruitment of minus end–directed dynein–dynactin motor complexes, resulting in microtubule-dependent retrograde transport toward the perinuclear microtubule organizing center (MTOC; Jordens et al., 2001; Johansson et al., 2005). A tripartite complex of RILP–Rab7–ORP1L has been proposed to be the functional unit that both recruits and activates motor complexes (Johansson et al., 2007). Additionally, RILP enhances the biogenesis of multivesicular body (MVB) transport intermediates, possibly through interactions with VPS22 and VPS36 components of the ESCRT (endosomal sorting complex required for transport) protein-sorting machinery (Progida et al., 2006; Wang and Hong, 2006).

Previous studies showed that RIDα postendocytically diverts the EGFR to lysosomes via MVBs and that the viral protein is localized to early endosomes and MVB-limiting membranes (Hoffman et al., 1992a; Hoffman and Carlin, 1994; Crooks et al., 2000). However, the molecular basis of RIDα- or RIDα/β-mediated degradation remains to be elucidated. RIDα lacks intrinsic catalytic activity, suggesting it alters trafficking primarily by modulating host-encoded sorting or trafficking machineries. In this study, we discovered that RIDα interacts with two of the known Rab7 effectors, RILP and ORP1L, and that in vitro interaction with RILP is facilitated by Cu2+ binding to two histidine residues in RIDα. Importantly, RIDα enhanced late endocytic trafficking and compensated for Rab7 gene silencing or dominant-negative (DN) Rab7 expression. A mutant RIDα that failed to associate with RILP was also defective in these GTP-Rab7 compensatory activities and in mediating the down-regulation of EGFR and Fas. Our results suggest that RIDα is a functional analogue of GTP-Rab7. This mimicry provides insights into the mechanism of enhanced degradation of plasma membrane receptors by adenovirus and the general cellular requirements for late endocytic trafficking.

Results

RIDα localization and its cytoplasmic tail–binding partners

RIDα is a type II integral membrane protein consisting of a short N-terminal cytosolic domain, two transmembrane domains connected by an exocytic loop, and a C-terminal cytosolic tail (Fig. 1a; Hoffman et al., 1992b). It is enriched in perinuclear vesicles that are dependent on the microtubule network for localization. FLAG-RIDα–containing vesicles are dispersed throughout the cytosol upon 30-min treatment with the microtubule-disrupting agent nocodazole but not the actin-disrupting agent cytochalasin D (Fig. 1 b). These data are consistent with previous reports that RIDα is localized to MVBs (Crooks et al., 2000) as these and other late endocytic structures undergo minus end–directed microtubule transport toward the MTOC (Gruenberg, 2001).

Figure 1.

RIDα localization and interaction with RILP. (a) Model showing known RIDα membrane topology and C-terminal tail amino acid sequence used as bait in a yeast two-hybrid screen. The loop domain in the lumen has a site for signal peptidase cleavage and disulfide bond formation (Hoffman et al., 1992b). (b) Stably expressed FLAG-RIDα in CHO cells was stained for the FLAG epitope (red) and with DAPI (blue) after treatment with vehicle or cytoskeleton-disrupting drugs. Cell peripheries (green) were traced from a phase image using MetaMorph software. (c) Schematic representation of RILP with known protein-binding domains. The RIDα-binding domain partially overlaps residues in the second α-helical regions (a1 and a2) previously identified as the GTP-Rab7–binding site (Wu et al., 2005). (d) GST fusion proteins with the progressive stop codons introduced at residues highlighted in black in panel a were purified and separated by SDS-PAGE. (e) GST fusion proteins were incubated with lysates from cells overexpressing HA-RILP. Bound proteins were detected by a Western blot for the HA epitope tag. (f) GST fusion proteins were incubated with an irrelevant HA-tagged protein and analyzed as in panel e. (g) HA-RILP immobilized on an anti-HA affinity column was incubated with purified GST or full-length GST-RIDα cytoplasmic tail. Bound proteins were detected by a Western blot for GST. Bars, 10 μm.

We performed a yeast two-hybrid screen of a HeLa cell cDNA library using bait encoding the full-length C-terminal tail of RIDα. The screen isolated cDNA regions of two GTP-Rab7 effector proteins, RILP and ORP1. The screen also identified cDNA regions of two heat-shock proteins (Hsps), Hsp60 and Hsp90. The shortest cDNA fragment of RILP isolated by the yeast two-hybrid screen corresponded to amino acids 261–308 (Fig. 1 c). We used a series of GST fusion proteins with RIDα cytoplasmic tails containing progressive stop codons (Cianciola et al., 2007) to verify the interaction and map the RILP-binding domain in RIDα (Fig. 1 d). A GST pull-down assay was performed in the presence of 75 μM Cu2+ with lysates prepared from CHO cells transiently overexpressing HA epitope–tagged RILP (HA-RILP; Fig. 1 e). This assay verified the RIDα–RILP interaction and demonstrated that the interaction was disrupted upon truncation of the RIDα cytoplasmic tail to Ala71. A nonspecific HA epitope–tagged protein did not interact with full-length GST fusion protein (Fig. 1 f). HA-RILP immobilized on an anti-HA affinity column also specifically captured purified full-length GST-RIDα cytoplasmic tail fusion protein and not purified GST (Fig. 1 g).

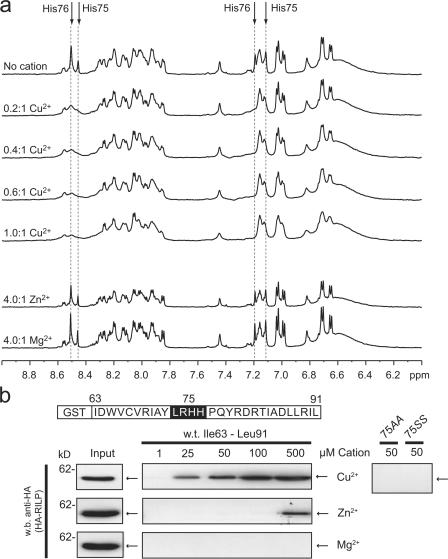

The in vitro binding of RILP with RIDα is facilitated by Cu2+

The region of RIDα required for RILP interaction harbors an LRHH motif that is also found in the fusogenic peptide B18 from the sea urchin sperm acrosomal protein bindin (Ulrich et al., 1998). The B18 histidine-rich motif is a divalent cation-coordinating site that regulates fusogenic activity by permitting the peptide to adopt different structural conformations in the presence of Zn2+ or Cu2+ (Sinz et al., 2003). To test whether the RIDα sequence interacts with divalent cations, we examined the amide-aromatic region of the one-dimensional 1H nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra of a peptide identical to amino acids 69–91 in the absence or presence of divalent cations (Fig. 2 a). The proton peaks for this region of the spectra have been previously assigned (Vinogradova et al., 1998). The addition of a 4:1 molar excess of Zn2+ or Mg2+ had no noticeable effect. However, the addition of Cu2+ resulted in a pronounced broadening of peaks corresponding to the δ2 and ɛ1 side chain protons of His75 and His76. This observation strongly suggests a specific interaction in vitro between Cu2+ and these two histidine residues.

Figure 2.

Cu2+ interacts with RIDα and enhances RIDα–RILP interaction. (a) 1D 1H NMR spectra of the amide/aromatic region of 23 C-terminal residues of RIDα illustrating the effects of metal ion (Mg2+, Zn2+, and Cu2+) binding. Aromatic side chain Hδ2 and Hɛ1 resonances of His75 and His76 (dashed lines) were previously determined (Vinogradova et al., 1998). Selective line broadening was observed for histidine side chains upon the addition of Cu2+ but not Zn+2 or Mg+2. (b) GST pull-down assays were performed as shown in Fig. 1 e with fusion proteins encoding the full-length C-terminal tail in the presence of indicated cation concentrations. Mutations of Cu2+-binding residues 75HH to 75AA or 75SS blocked in vitro interactions with RILP.

Because the RILP- and Cu2+-interacting domains of RIDα overlap, we asked whether Cu2+ specifically regulates the interaction between the full-length RIDα cytoplasmic tail GST fusion protein and HA-RILP. A dose-dependent relationship between Cu2+ concentration and the HA-RILP–GST-RIDα interaction was observed (Fig. 2 b). Furthermore, mutation of the Cu2+-binding histidine residues to a dialanine or diserine abolished the interaction between RIDα and HA-RILP (Fig. 2 b). These data suggest that the Cu2+-binding properties of His75 and His76 are critical for in vitro binding of RIDα and RILP. Whether Cu2+ serves as a bridge between the two proteins or facilitates formation of a RIDα conformation required for RILP interaction remains to be determined.

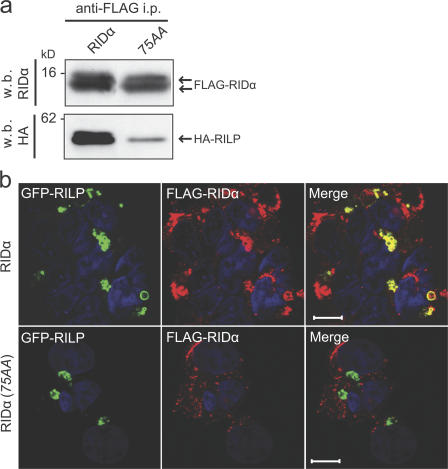

Coimmunoprecipitation and colocalization of RIDα and RILP

The inability of the GST-RIDα fusion protein harboring a 75AA mutation to interact with RILP led us to compare in vivo interactions between RILP and wild-type RIDα or RIDα with a similar mutation. Coimmunoprecipitation experiments were performed in cells stably expressing wild-type or mutant RIDα with N-terminal epitope tags and transiently expressing HA-RILP. Expression of the epitope tag had no effect on RIDα subcellular distribution (unpublished data). Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with an anti-FLAG antibody, and immune complexes were probed with antibodies to RIDα or RILP. Introduction of the 75AA mutation had no effect on the formation of both molecular weight isoforms of the RIDα protein (Fig. 3 a, top). We also found that HA-RILP was present in immune complexes with FLAG-RIDα but not FLAG-RIDα(75AA) (Fig. 3 a, bottom). To determine whether these two proteins colocalize in cells, stable cell lines transiently expressing GFP-tagged RILP (GFP-RILP) were fixed and stained for the FLAG epitope and examined by confocal microscopy. Consistent with previous studies, RILP overexpression induced formation and aggregation of perinuclear vesicles (Jordens et al., 2001; Wang et al., 2004). GFP-RILP–positive vesicles were costained with the FLAG antibody in cells expressing FLAG-RIDα but not FLAG-RIDα(75AA) (Fig. 3 b). Altogether, these studies demonstrate that both in vitro and in vivo RIDα–RILP interactions depend on RIDα residues His75 and His76. Furthermore, association between FLAG-RIDα and RILP may also regulate vesicle positioning, as FLAG-RIDα(75AA) vesicles were relatively dispersed in the cytosol compared with vesicles enriched for wild-type RIDα.

Figure 3.

Colocalization and coimmunoprecipitation of RIDα and RILP. (a) Cell lysates from GP2-293 cells stably expressing FLAG-RIDα or FLAG-RIDα(75AA) and transfected with a plasmid encoding HA-RILP were immunoprecipitated with an anti-FLAG antibody and followed by a Western blot for FLAG to detect RIDα or HA to detect coimmunoprecipitated HA-RILP. (b) GP2-293 cells transfected with a plasmid encoding GFP-RILP were fixed and stained for the FLAG epitope tag (red) and with DAPI (blue) 12 h after transfection. Confocal microscopy demonstrates partial merging of GFP-RILP signals with FLAG-RIDα but not FLAG-RIDα(75AA). Bars, 10 μm.

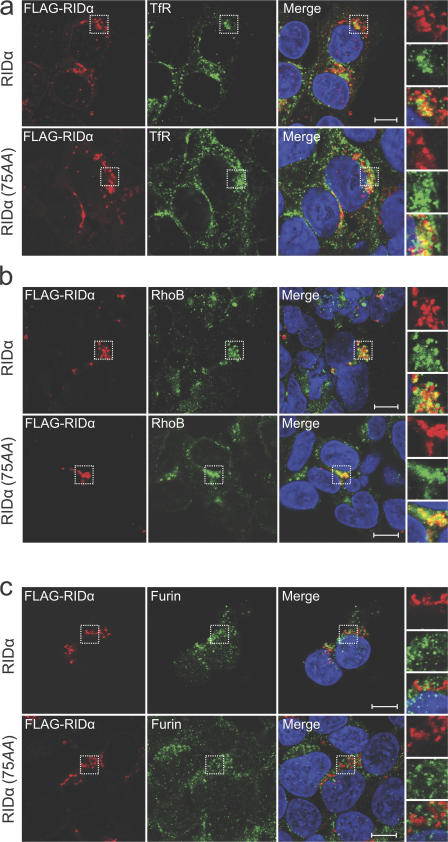

To rule out the possibility that the 75AA mutation affects RIDα targeting, we verified that FLAG-RIDα and FLAG-RIDα(75AA) both partially colocalize with two endocytic marker proteins, transferrin receptor (Fig. 4 a) and RhoB (Fig. 4 b). However, even in a previous study with acutely infected cells that reported similar results (Crooks et al., 2000), it has not been possible to identify markers that precisely overlap RIDα vesicle staining. Similar to other intracellular pathogen gene products, RIDα appears to occupy an intracellular vesicle that superficially resembles an endosome but has modified the endosome maturation process to generate a novel vesicle that benefits adenovirus survival. Additionally, FLAG-RIDα and FLAG-RIDα(75AA) both escape the TGN, as neither colocalizes with furin, a TGN marker (Fig. 4 c). Thus, 75AA does not appear to adversely affect a nearby clathrin AP-1–binding site required for targeting newly synthesized RIDα from the TGN to endosomes (Cianciola et al., 2007).

Figure 4.

Localization of RIDα with compartment-specific markers. Stable GP2-293 cell lines were stained for the FLAG epitope (red), with DAPI (blue), and for transferrin receptor (a), RhoB (b), and furin (c; green channels). Boxed areas are enlarged on the right. Bars, 10 μm.

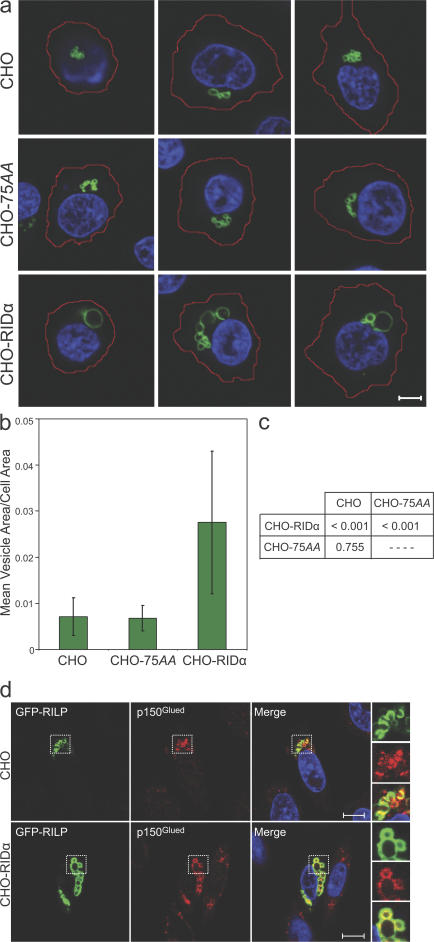

RIDα enhances the size of RILP-labeled vesicles

GFP-RILP–labeled vesicles appeared to be larger in cells expressing RIDα versus RIDα(75AA). To quantitatively address this observation, we compared cross-sectional areas of GFP-RILP–labeled vesicles in parental CHO cells and in CHO cells expressing RIDα proteins. The CHO background was chosen because of a more uniform cell size and shape within a population. Cells were fixed and stained with DAPI 12 h after transfection. Both phase and confocal serial z-section images were taken for 25 randomly selected cells, resulting in analysis of >70 vesicles for each cell type. The periphery of each cell was traced from the z-section phase image demonstrating the greatest cellular area. For each GFP-RILP–labeled vesicle, the area was determined from the confocal plane demonstrating the greatest cross-sectional area. Representative confocal images merged with the traced cell periphery are displayed in Fig. 5 a. The ratio of vesicle to cell area was determined, and the mean ratio with the SD for each cell type is presented (Fig. 5 b). A mixed effects analysis of variance (ANOVA) statistical model treatment of the data found the difference in vesicle size between CHO-RIDα versus CHO-75AA or parental CHO cells to be significant (P < 0.001; Fig. 5 c). GFP-RILP appears to retain its ability to recruit the p150Glued subunit of the dynein–dynactin motor complex in the presence of RIDα as the enlarged GFP-RILP–labeled vesicles found in CHO-RIDα cells colocalize with p150Glued (Fig. 5 d). Enlargement of GFP-RILP–labeled vesicles by RIDα but not RIDα(75AA) provides evidence for a functional interaction between RILP and RIDα in cells. However, it is not clear whether the increased size is caused by enhanced import into GFP-RILP–positive structures or decreased export out of these structures.

Figure 5.

Enlargement of GFP-RILP–labeled vesicles by RIDα. (a) CHO, CHO-RIDα, or CHO-75AA cell populations transfected with a plasmid encoding GFP-RILP were fixed and stained with DAPI (blue). Images were generated by merging of the largest traced cell periphery from a phase image plane (red) with a confocal plane representing the largest area for an individual GFP-RILP–labeled vesicle (green). Three representative images of each cell type are shown. Bar, 10 μm. (b) Ratios of vesicle to cell area for every identifiable vesicle (n > 70 for each cell type) were obtained with MetaMorph software. Data are presented as mean ratios ± SDs (error bars). (c) A mixed effects ANOVA statistical model treatment of data found the difference in vesicle size between RIDα versus RIDα(75AA) or parental CHO cells to be significant (P < 0.001). (d) GFP-RILP–transfected CHO cells were stained for p150Glued (red) and with DAPI (blue). Boxed areas are enlarged on the right. Bars, 15 μM.

RIDα compensates for Rab7

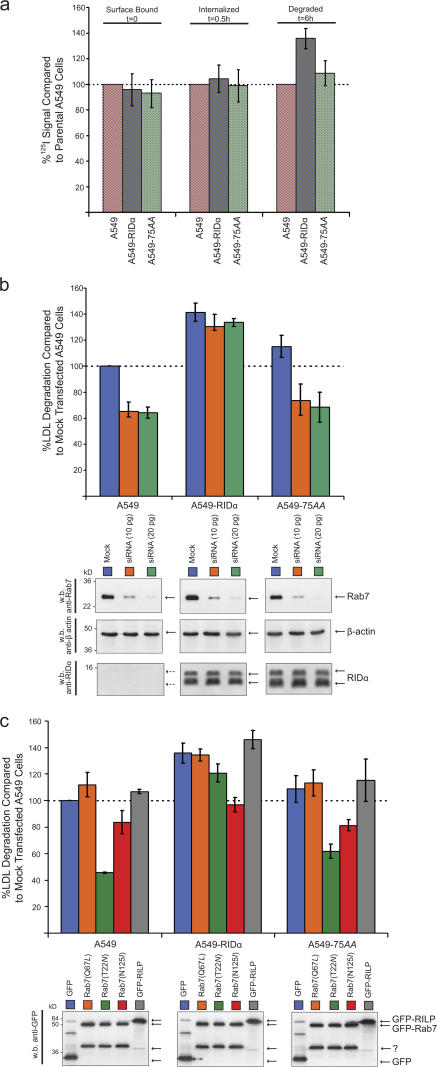

A low-density lipoprotein (LDL) degradation assay was used as a biological readout for late endocytic trafficking. In contrast to the LDL receptor that undergoes recycling, LDL is sorted toward lysosomes after ligand–receptor complexes dissociate in acidified endocytic compartments (Jeon and Blacklow, 2005). Cells incubated with 125I-LDL were assayed for the amount of radioactivity that was cell surface bound at 0 h, internalized at 0.5 h, and degraded at 6 h. Stable expression of RIDα or RIDα(75AA) in A549 cells did not alter the cell surface binding or internalization of LDL (Fig. 6 a), which is consistent with reports that only select cell surface receptors are affected by RIDα (Kuivinen et al., 1993). However, A549-RIDα cells demonstrated a significant increase (P < 0.005) over parental A549 and A549-75AA cells in LDL degradation at 6 h (Fig. 6 a), which is consistent with the idea that RIDα alters the fate of late endocytic lumenal cargo.

Figure 6.

RIDα compensates for Rab7. (a) Cells incubated with 125I-LDL were assayed for surface-bound (0 h), internalized (0.5 h), and degraded LDL in the medium (6 h). Results are presented as percentages relative to parental A549 cells. (b, top) 125I-LDL degradation assay was performed in cells transfected with Rab7-specific siRNA and incubated for 24 h. Experiments were performed in triplicate on two separate occasions. Data (mean ratios ± SDs [error bars]) are plotted as percentages of mock-transfected cells and analyzed by t test. (bottom) Equal aliquots of total cell protein were Western blotted with antibodies against Rab7, actin, and RIDα. (c, top) 125I-LDL degradation assay was performed in cells transfected with GFP or GFP-tagged Rab7 constructs. (bottom) Transient protein expression was determined by Western blotting for GFP.

It is possible that Rab7 is corecruited to RIDα vesicles through interaction with GTP-Rab7 effector proteins. To directly address the possibility of Rab7 involvement, we examined late endocytic trafficking changes initiated by RIDα under conditions of reduced Rab7 expression or during the transient expression of DN Rab7 constructs. Parental A549 cells, A549-RIDα, or A549-75AA were transfected with a Rab7-specific siRNA or Rab7 plasmids for 24 h. In all test conditions, the amount the 125I-LDL surface bound at 0 h and internalized at 0.5 h was essentially identical (unpublished data), which is consistent with previous reports that Rab7 does not directly affect LDL receptor cell surface expression or internalization (Vitelli et al., 1997). Reduced Rab7 expression led to a corresponding decrease in LDL degradation in A549 and A549-75AA cells (P < 0.005 for both comparisons) but had no effect in A549-RIDα cells (Fig. 6 b). RIDα but not RIDα(75AA) rescued the LDL degradation defect caused by reduced Rab7 expression, suggesting that the interaction between RIDα and RILP is required for RIDα-mediated effects on late endocytic trafficking.

RIDα also enhanced LDL degradation in the presence of a Rab7 DN mutant, Rab7(T22N) (Fig. 6 c). We used constructs expressing GFP fusion proteins to verify similar transfection efficiencies in all test conditions (unpublished data). GFP-Rab7(T22N) expression resulted in decreased LDL degradation in A549 and A549-RIDα(75AA) cells (P < 0.001 for both comparisons) but had no effect in A549-RIDα cells. RIDα-mediated enhanced LDL degradation circumvented the block induced by GFP-Rab7(T22N), which is preferentially bound to GDP (Li et al., 1994), in contrast to the nucleotide binding–incapable DN Rab7(N125I) (Bucci et al., 1992; Feng et al., 1995), in which there is little effect. Thus, RIDα but not RIDα(75AA) promotes a late endocytic trafficking step that bypasses the requirement for GTP-Rab7.

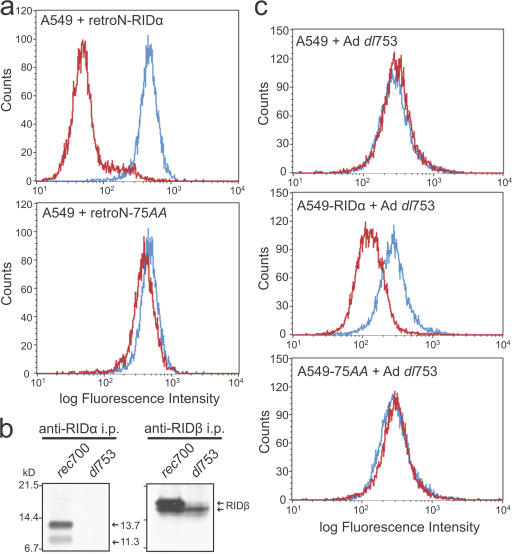

RIDα(75AA) fails to down-regulate cell surface EGFR and Fas expression

Because RIDα(75AA) failed to enhance late endocytic trafficking, we asked whether it would also be defective in the clearance of cell surface receptors previously linked to RIDα or RIDα/β expression. Our laboratory has reported that RIDα expression is necessary and sufficient to induce EGFR down- regulation (Hoffman et al., 1990). As measured by flow cytometry, we found a reduction in cell surface EGFR expression in A549 cells infected with a retrovirus expressing RIDα in contrast to the RIDα(75AA) retrovirus, which had no effect (Fig. 7 a). Similar results were obtained for Fas, which is down-regulated by the RIDα/β complex. A549, A549-RIDα, and A549-75AA cells were infected with an adenovirus (dl753) harboring a deletion in RIDα but expressing all other adenoviral proteins, notably RIDβ. As previously reported (Tollefson et al., 1990), the expression of RIDβ is reduced during dl753 infection compared with the parental wild-type adenovirus type 5/2/5 hybrid (rec700; Fig. 7 b). However, this level of RIDβ expression is sufficient to reconstitute cooperative RIDα/RIDβ activity because A549-RIDα infected with the dl753 virus exhibited reduced Fas cell surface expression. However, A549-75AA cells did not show reduced Fas cell surface expression. These results demonstrate that the association of RILP and possibly other unidentified interactions mediated by the histidine residues of RIDα are critical for the principle activity of receptor down-regulation ascribed to the RID complex.

Figure 7.

Down-regulation of cell surface EGFR and Fas. (a) A549 cells infected with retrovirus expressing RIDα or RIDα(75AA) were analyzed for EGFR surface expression by flow cytometry 24 h after infection. Data are plotted for uninfected (blue) and infected (red) cells. (b) A549 cells were infected with wild-type adenovirus (rec700) or an RIDα deletion mutant (dl753) and were metabolically labeled with [35S]Cys/Met. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with RIDα or RIDβ antibodies under nondenaturing conditions and were subjected to SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. (c) A549, A549-RIDα, or A549-RIDα(75AA) cells were infected with dl753 for 18 h, labeled with a FITC-conjugated antibody recognizing the extracellular domain of Fas, and subjected to FACS analysis. Data are plotted for uninfected (blue) and infected (red) cells. All experiments were performed on three separate occasions, and a representative experiment is presented.

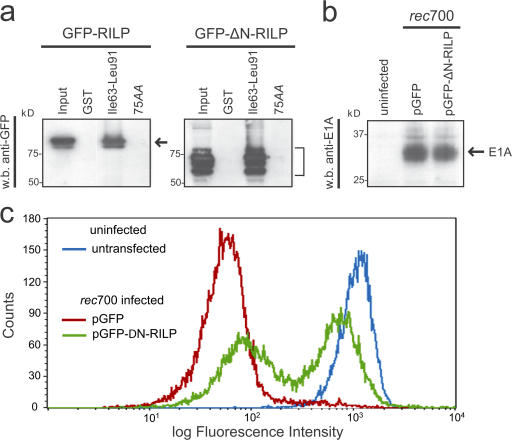

DN RILP perturbs RIDα-mediated EGFR down-regulation

Expression of only the C-terminal half of RILP (ΔN-RILP encoding amino acid residues 199–401) results in a DN phenotype (Cantalupo et al., 2001; Jordens et al., 2001), presumably because the mutant competes with endogenous RILP for GTP-Rab7 binding and fails to recruit motor complexes (Fig. 1 c). Because RIDα also binds the C-terminal region of RILP, we asked whether ΔN-RILP perturbs RIDα activity. To address this question, we examined the effect of transient ΔN-RILP expression on the adenovirus-mediated down-regulation of EGFR. To ensure measurements of only transfected cells, we used GFP-tagged ΔN-RILP. A GST pull-down assay revealed that GFP–ΔN-RILP associates with RIDα similarly to GFP-RILP (Fig. 8 a). The expression of GFP–ΔN-RILP did not appear to hinder adenovirus infection compared with control GFP transfection as measured by the expression of adenovirus E1A (Fig. 8 b) and examination of cellular size and granularity changes by flow cytometry (unpublished data). To measure the effect on EGFR surface expression, A549 cells were transiently transfected with a plasmid encoding either GFP or GFP–ΔN-RILP for 36 h, infected with wild-type rec700 adenovirus, and assayed by flow cytometry 12 h after infection (Fig. 8 c). Plots of the transfected cells represent cells gated for GFP expression, which represent 30–40% of the total cell population (unpublished data). Approximately 63% of GFP–ΔN-RILP–expressing cells failed to down-regulate the EGFR upon adenovirus infection (Fig. 8 c). The presence of native RILP and other RIDα-interacting proteins may account for the lack of complete inhibition of RIDα activity. Nonetheless, the DN effect of GFP–ΔN-RILP implicates the involvement of RILP in adenovirus-mediated EGFR down-regulation EGFR and suggests that RIDα interacts with RILP similarly to GTP-Rab7.

Figure 8.

ΔN-RILP impairs RIDα-mediated EGFR down-regulation. (a) GST fusion proteins were incubated with lysates from cells overexpressing GFP-RILP or GFP–ΔN-RILP. Bound proteins were detected by a Western blot for GFP. (b) A549 cells were transiently transfected with a plasmid encoding GFP or GFP–ΔN-RILP and infected with rec700. To ensure that RILP proteins do not interfere with infection, total cell lysates were analyzed for E1A expression by Western blotting. (c) A FACS profile is presented of the EGFR surface expression of ungated control cells (blue), GFP-transfected, rec700-infected, and GFP-gated cells (red), and GFP–ΔN-RILP–transfected, rec700-infected, and GFP-gated cells (green).

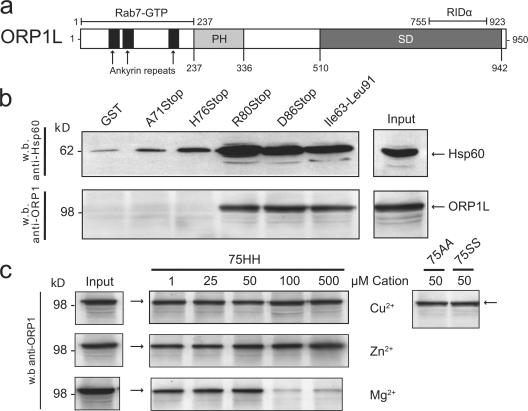

RIDα additionally interacts with ORP1L

An RILP–Rab7–ORP1L tripartite complex has recently been identified that links GTP-Rab7 to minus end–directed molecular motors (Johansson et al., 2007). The authors of this study provide evidence suggesting this complex forms in a step-wise fashion and that RILP and ORP1L bind simultaneously to GTP-Rab7 but not to each other. The initial yeast two-hybrid screen for RIDα-interactive partners also isolated a cDNA encoding ORP1. The shortest ORP1 cDNA fragment corresponded to amino acid residues 755–923, a region coded by a shared exon of both ORP1 isoforms, ORP1S and ORP1L (Fig. 9 a; Jaworski et al., 2001; Lehto et al., 2001). We elected to further explore ORP1L based on its prevalence over ORP1S in lung tissue, macrophages, and monocytes (Johansson et al., 2003) and its reported roles as a GTP-Rab7 effector and regulator of MVB morphology (Johansson et al., 2005, 2007). Using the same GST-RIDα fusion proteins shown in Fig. 1 d, we confirmed that ORP1L associated with the RIDα cytoplasmic tail downstream of His76 (Fig. 9 b). Interestingly, these results were obtained only when cell lysates were immunodepleted for Hsp60 before they were added to GST fusion protein affinity beads, suggesting that Hsp60 and ORP1L compete for binding to the same general region in the RIDα cytoplasmic tail (Fig. 9 b). The 75AA and 75SS mutations that prevent RILP binding had no effect on the RIDα–ORP1L interaction (Fig. 9 c). ORP1L binding also did not appear to be dependent on divalent cations (Fig. 9 c). Thus, similar to Rab7, RIDα has distinct binding sites for two different effector molecules that may be similarly involved in the step-wise assembly of minus end–directed molecular motors.

Figure 9.

RIDα additionally interacts with ORP1L. (a) Schematic representation of ORP1L. The shortest cDNA clone identified in our screen corresponds to amino acids 755–923 in the sterol-binding domain (SD). ORP1L also has a pleckstrin homology domain (PH) and ankyrin repeats (Lehto et al., 2001). GTP-Rab7 binding has been mapped to the N terminus (Johansson et al., 2005). (b) ORP1L and Hsp60-binding domains were mapped using the GST fusion proteins shown in Fig. 1 d. Total cell lysates were immunodepleted for Hsp60 before addition to GST fusion proteins for ORP1L mapping. (c) ORP1L binding to the full-length GST fusion protein was determined in the presence of indicated cation concentrations.

Discussion

Although RID proteins have been extensively studied for over a dozen years, there is still relatively little information regarding their molecular basis of action. Data presented in this manuscript show for the first time that the RIDα-interactive host protein RILP is required for EGFR down-regulation in adenovirus-infected cells. Although we have not directly addressed the role of RIDβ in these experiments, it seems likely that RILP is also important for its ability to down-regulate Fas in conjunction with RIDα. A deletion mutant in a region of RIDα overlapping the known RILP-binding domain has also been shown to prevent both EGFR and Fas down-regulation (Zanardi et al., 2003).

There is no appreciable amino acid sequence homology between Rab7 and RIDα, suggesting that RIDα developed novel modes of interaction with two Rab7 effectors through convergent evolution. The RIDα–RILP interaction most likely preserves the dynein–dynactin motor complex recruitment and late endosomal/lysosomal clustering properties of RILP, as indicated by the colocalization of GFP-RILP and p150Glued in RIDα-expressing cells, perinuclear aggregation and enlargement of RILP-positive vesicles in the presence of RIDα, and the DN effect of ΔN-RILP. Enlarged late endocytic structures are also generated upon the overexpression of constitutively active Rab7(Q67L) (Bucci et al., 2000), further demonstrating GTP-Rab7 mimicry by RIDα. Although it is possible that RIDα hinders RILP-mediated budding out of or into enlarged endosomes, we consider it more likely that these structures reflect an increased number of vesicles available for RILP-mediated perinuclear convergence as a result of the presence of RIDα.

RIDα residues His75 and His76 interact with Cu2+ to enhance the in vitro binding of RILP. RIDα with a substitution for the dihistidine failed to enhance LDL degradation and did not mediate cell surface receptor clearance, demonstrating the importance of RILP and other possible interactions with the Cu2+-binding region of RIDα. The in vitro use of Cu2+ may generate RIDα conformations capable of binding RILP that were attained through different means in vivo. However, Cu2+ itself may regulate the in vivo interaction between RIDα and RILP along with resultant effects on trafficking, which is similar to the Cu2+-dependent interaction between the cytosolic N terminus of the late endosome–associated copper transporter ATP7B and the dynactin subunit p62 (Lim et al., 2006). Interestingly, another E3 protein, 14.7K, binds divalent metals (Zn2+ and Co2+), and this property is also necessary for recovery of functional 14.7K from a bacterial expression system (Kim and Foster, 2002).

The ability of RIDα to enhance LDL degradation in Rab7-depleted cells or in the presence of DN Rab7(T22N) suggests that RIDα facilitates an endocytic trafficking route that bypasses a step normally regulated by Rab7. Interestingly, RILP overexpression also overcomes the blockade induced by Rab7(T22N) (Cantalupo et al., 2001), suggesting that RIDα mimics RILP overexpression by increasing the local recruitment of native RILP. RIDα may also regulate other Rab7-dependent processes such as phagosome maturation, autophagy, axonal retrograde transport, and melanosome transport.

Our yeast two-hybrid screen predicts that ORP1L may also be required for functional GTP-Rab7 mimicry by RIDα. Similar to RILP, ORP1L overexpression leads to perinuclear clustering and enlargement of late endosomes/lysosomes (Johansson et al., 2003). The overlapping phenotype is not a consequence of redundant effector protein activities but is the result of the simultaneous engagement of RILP and ORP1L by GTP-Rab7 leading to formation of a tripartite complex (Johansson et al., 2007). The coordinated activity of both effectors may be required for the formation of a functional minus end–driven dynein–dynactin motor complex. RILP interacts with the C-terminal region of the dynactin projecting arm, p150Glued, leading to the recruitment of dynein motors to RILP-containing endosomes (Johansson et al., 2007). However, this recruitment is insufficient to drive minus end transport in the absence of ORP1L. ORP1L may subsequently transfer dynein–dynactin motor complexes to βIII spectrin, which interacts with the Arp1 subunit of dynactin (De Matteis and Morrow, 2000; Holleran et al., 2001). RIDα likely mimics GTP-Rab7 by regulating the assembly of a similar RILP–RIDα–ORP1L tripartite complex.

Although Hsps are common false positives, it is conceivable that Hsp60 or Hsp90, which were also identified by our yeast two-hybrid screen, play a physiological role in RIDα function. Hsp60 may selectively preclude access of ORP1L to the RIDα cytoplasmic tail, similar to its ability to regulate interaction between the signaling adaptor MyD88 and Toll-like receptor 1 (Brown et al., 2006). A role for Hsp90 is supported by studies with the inhibitor geldanamycin that diverts ErbB2 from a recycling to a degradative pathway (Austin et al., 2004) and restores the ligand-mediated degradation of kinase domain mutant EGFRs (Yang et al., 2006). In addition, Hsp90 found on the cytosolic face of the lysosomal membrane facilitates chaperone-mediated autophagy (Agarraberes and Dice, 2001).

Potential regulation of RILP and ORP1L recruitment by Cu2+ and Hsp60, respectively, is consistent with a requirement for effector protein disengagement for continued vesicle maturation and/or extension of protein half-life. A similar mode of regulation is achieved by the GTPase cycle of Rab7. It has been demonstrated that ORP1L overexpression stabilizes GTP-Rab7 and leads to impaired TRITC-dextran transport to late endocytic compartments (Johansson et al., 2005). This excessive engagement may sequester components or preclude access to components necessary for the final stages of late endosome maturation and lysosome fusion. The short cytoplasmic tail of RIDα lacks any intrinsic GTPase or catalytic activity and, thus, must rely on alternative mechanisms to regulate effector protein engagement.

In addition to these studies, we have previously reported that RIDα is necessary and sufficient for EGFR down-regulation (Hoffman et al., 1990; Cianciola et al., 2007). However, this result is controversial, and other investigators contend that RIDβ is also necessary based on results obtained by infecting tissue culture cells simultaneously with multiple adenovirus mutants (Tollefson et al., 1991). Productive infections consist of early, intermediate, and late stages characterized by temporal expression of virally encoded gene products (Ginsberg, 1999). Viral DNA synthesis marks the onset of the intermediate phase when a majority of early gene transcripts, including E3, are shut off and the infected cell initiates transcription of late viral genes. The E3 transcript is alternatively spliced into multiple overlapping mRNAs, termed a through i, encoding at least nine proteins (Gooding and Wold, 1990). RIDα and, to some extent, RIDβ are encoded by transcript f, which accounts for ∼15% of total E3 production during a natural infection. Many genetically modified viruses used to study this region involve mutations that up-regulate production of the f transcript at the expense of other E3 transcripts. In addition to altering E3 transcript ratios, many cell culture experiments are carried with DNA synthesis inhibitors to amplify E3 gene expression by blocking the early to late transition. Thus, although many E3 functions have been identified in tissue culture, their roles in a natural infection in which they may be less abundantly expressed and expressed for relatively brief intervals remain to be determined.

Originally identified by its ability to down-regulate EGFR using a panel of group C adenovirus mutants (Carlin et al., 1989), it was subsequently shown that RIDα can form a complex with a second E3 protein, RIDβ, in infected cells after a cycloheximide-enhanced procedure to trigger a synchronous burst of E3 protein expression (Tollefson et al., 1991). However, these two proteins are enriched in different membrane compartments (Stewart et al., 1995; Crooks et al., 2000), which is consistent with the idea that they may have independent as well as cooperative functions. We also suggest that the seemingly disparate results reported by different laboratories are not necessarily in conflict (Tollefson et al., 1991). RIDβ may alleviate an inhibitory constraint in the context of an acute adenovirus infection and/or as a consequence of cycloheximide treatment that is not encountered during our gene transfer experiments.

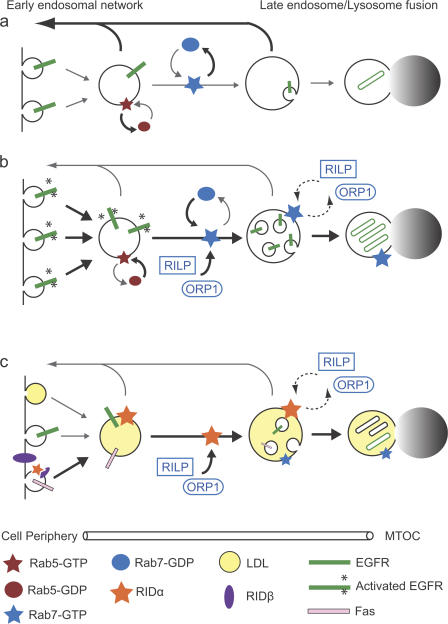

The protein interactions identified by this study account for the diversion of endocytic cargo toward degradation. However, receptor selection in early endocytic compartments and sorting into MVBs remain to be elucidated. Our laboratory has demonstrated that RIDα encodes all necessary information to select, divert, and sort EGFR. EGFR specificity is dependent on a shared LLRIL amino acid sequence identity with RIDα (Crooks et al., 2000). This sequence motif may usurp a normal cellular sorting machinery, as it is also required for ligand-dependent EGFR degradation (Kil et al., 1999). Other cargoes may require adenovirus-encoded accessory molecules to deliver specific receptors to dynamic endosomes (Fig. 10). This conjecture is consistent with the observations that RIDβ is capable of binding AP-2 (Hilgendorf et al., 2003), that AP-2 is required for TNFR1 down-regulation, and that TNFR1 coimmunoprecipitates with the RID complex (Chin and Horwitz, 2005). By engaging both the clathrin adaptor and TNFR1, RIDβ may sort TNFR1 to an endosome subsequently diverted to lysosomes by an RILP–RIDα–ORP1L complex. Additional selection measures must exist for the TRAIL receptors and Fas. The ability to mix and match different aspects of RID protein function may have evolved to allow adenoviruses to fine-tune RID activity in different cell types or during acute versus persistent infections.

Figure 10.

Role of RIDα in receptor down-regulation. Model depicting EGFR endocytic trafficking under resting conditions, after ligand stimulation, or during RIDα expression. Major trafficking routes are represented by thicker black arrows, and minor trafficking routes are indicated by thinner gray arrows. (a) During resting conditions, a majority of EGFRs internalized at a low basal rate recycle back to the cell surface. (b) During ligand stimulation, EGFR internalization rates and GTP-Rab7 recruitment to EGFR-containing vesicles are enhanced. GTP-Rab7 binds RILP and ORP1L (dashed arrows), which subsequently recruit and activate motor proteins that induce microtubule-dependent displacement toward the MTOC. (c) RIDα associates with EGFR-containing vesicles in the early endosomal network under resting conditions and recruits GTP-Rab7 effectors RILP and ORP1L, leading to microtubule-dependent displacement toward the MTOC. RIDα also enhances the degradation of LDL after its release from internalized LDL receptors and acts cooperatively with RIDβ to down-regulate Fas. Although RIDα and RIDβ are enriched in endosomes and plasma membrane, respectively, they can also form physical complexes that are important for some aspects of E3 function.

Materials and methods

Plasmids

Yeast two-hybrid plasmids were gifts from S. Brady-Kalnay (Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH). All GFP-Rab7 and GFP-RILP plasmids were gifts from C. Bucci (Università di Lecce, Lecce, Italy). ORP1L-expressing plasmid was a gift from V. Olkkonen (University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland). The GFP–ΔN-RILP plasmid encoding an N-terminal truncated form of RILP (amino acid residues 199–401) was a gift of J. Neefjes (The Netherlands Cancer Institute, Amsterdam, Netherlands). Plasmids and reagents for pantropic retrovirus generation and the pGFP plasmid were obtained from Clontech Laboratories, Inc. pExchange vector was obtained from Stratagene.

Yeast two-hybrid methods

The coding sequence for the cytoplasmic C-terminal tail (amino acids 61–91) of RIDα from adenovirus serotype 2 was cloned into pEG202 (HIS3) in frame with the LexA DNA-binding domain. The RIDα insert was PCR amplified from a previously generated expression vector using the following primers to generate 5′ BamH1 and 3′ NotI restriction sites for directional in-frame cloning: forward (5′-CTGTAGTCATCGCCTGGATCCAGTTCATTG-3′) and reverse (5′-TTCAGGTTCAGCGGCCGCTGTGGGAGGTTTTTTA-3′). The resulting bait construct was introduced into yeast strain YPH499 (MATa) harboring the pSH18-34 (URA3) reporter plasmid. The YPH499 strain transformed with bait and reporter plasmids was mated with strain EGY48 (MATα) that was previously transformed with the pJG4-5 (TRP1) HeLa cell cDNA library controlled by the GAL promoter. The EGY48 strain also contains a chromosomal copy of the LEU2 gene, in which the activating sequences of the LEU2 gene are replaced with LexA operator sequences. Potential interactions were detected by growing the mated yeast strain on minimal His-Trp-Ura-Leu dropout plates containing 2% galactose and 1% raffinose. Colonies were selected for galactose-dependent growth on His-Trp-Ura-Leu dropout medium in combination with high levels of β-galactosidase activity. Positive interactions were determined by combined library and bait plasmid expression–dependent growth. Colonies were further selected on the basis of high levels of transcriptional activation of the β-galactosidase reporter plasmid as measured by the intensity of blue staining. Lastly, isolated library plasmids were assayed for the inability to interact with nonspecific test bait. Protein interaction partners were identified by BLASTn search using library plasmid DNA sequences generated from the primer 5′-TACCGTTAAGCGCCTGAAAA-3′ that were designed to initiate sequencing ∼100 bp upstream of the fusion site.

Yeast two-hybrid results

The following proteins were identified in the yeast two-hybrid screen: RILP (amino acids 261–308), ORP1 (amino acids 755–923), Hsp60 (amino acids 434–573), and Hsp90 (amino acids 1–180).

GST fusion protein generation and purification

Methods for cloning and mutagenesis of GST fusion proteins have previously been described (Cianciola et al., 2007). BL-21 cells harboring GST fusion protein expression plasmids were lysed with 0.1 mg/ml lysozyme, and nucleic acids were digested with 40 μg/ml DNase and 20 μg/ml RNase. Sarcosyl and Triton X-100 were added to a final concentration of 1.5% and 3.0%, respectively, and cell debris was cleared by centrifugation at 14,000 g. Glutathione–Sepharose beads (GE Healthcare) were added to cleared lysates and incubated overnight at 4°C. Beads were washed nine times with 50 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 10 mM MgCl2, 1% Triton X-100, and diminishing concentrations (1.0 M to 150 mM) of NaCl. Fusion proteins were eluted from beads and dialyzed with 0.05 M Tris, pH 8.0, according to standard protocols.

GST pull-down assay

106 CHO cells were plated on 100-mm dishes and transfected with 10 μg plasmid DNA encoding either HA-RILP or ORP1L using 30 μl CHO-TransIT (MirusBio) reagent according to the manufacturer's instructions. 24 h later, cells were washed with PBS and harvested with lysis buffer (20 mM Hepes, pH 7.6, 100 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0.2 mM PMSF, and 1 μM leupeptin). Lysates were supplemented with the appropriate cation when noted. For ORP1L pull-downs, the cell lysate was additionally incubated with 10 μg anti-Hsp60 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) attached to protein A–Sepharose (Sigma-Aldrich) for 2 h before its addition to glutathione beads that were previously loaded with the appropriate GST fusion protein. Fusion proteins were incubated with cell lysates at 4°C overnight. Beads were washed four times with lysis buffer, and bound proteins were solubilized with 2× laemmli buffer (National Diagnostics). Proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting using anti-HA (Sigma-Aldrich) or anti-ORP1 (Imgenex).

Generation of stable cell lines

Previously cloned Ad2 full-length RIDα with and without an N-terminal FLAG tag was amplified by PCR using Taq polymerase and primers with 5′ NotI and 3′ BsiWI restriction site overhangs and was cloned into the TA cloning vector pCR2.1 (Invitrogen). The following primers were used to generate the insert: forward with FLAG (5′-CTCGAAATTAACCCTCACTAAAGGGAACAAAAGC-3′), forward without FLAG (5′-TTACAAGCGGCCGCACGATAAGATCATGATTCCT-3′), and reverse (5′-TCGAGGTCGACGGTATCGTACGGCTTGATATCTGAT-3′). Nucleic acids coding for the dihistidines at positions 75 and 76 were mutagenized to encode dialanines using the Quick Change Mutagenesis kit (Invitrogen) using the primers (HH75AA) forward (5′-CGTACCTCAGGGCCGCTCCGCAATACAGAGACAG-3′) and (HH75AA) reverse (5′-CTGTCTCTGTATTGCGGAGCGGCCCTGAGGTACG-3′). Wild-type and mutant RIDα constructs were then subcloned into the pQCXIN bicistronic retroviral packaging vector using the NotI and BsiWI restriction sites upstream of the IRES element and neomycin resistance gene. The plasmids were introduced into the GP2-293 cells with 293 Trans-IT (MirusBio) transfection reagent, and pantropic retroviral particles were generated upon subsequent transfection of the pVSV-G plasmid. The retroviruses were used to infect CHO or A549 cells, and populations of cells with stable wild-type or mutant RIDα expression were generated by selection in 200 μg/ml G418 (EMD)-containing medium.

Coimmunoprecipitation

Cells were lysed in a 10-mM phosphate solution, pH 7.8, supplemented with 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 0.5% Triton X-100, 1 mM PMSF, and 1 μg/ml leupeptin for 15 min on ice. Clarified supernatants were incubated with anti–FLAG-M2 agarose (Sigma-Aldrich), anti-RIDα, or anti-RIDβ overnight at 4°C. Beads were washed eight times with a 50-mM phosphate solution, pH 7.8, supplemented with 150 NaCl and 0.05% Triton X-100. Immune complexes were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose for immunoblotting or autoradiography using standard methods.

NMR measurements

A peptide corresponding to RIDα amino acids 69–91 was purchased from EZ Biolab. NMR spectra were recorded at 25°C on a spectrometer (Avance; Bruker-Biospin) operating at a 1H resonance frequency of 600 MHz and equipped with a triple resonance cryoprobe with z-axis pulsed field gradients. Spectra were recorded with 4,096 complex data points and a sweep width of 8,012.8 Hz. Solvent suppression was achieved with presaturation during the 3-s recycle delay. All free induction decays were apodized with a cosine window function and 0.5 Hz of exponential line broadening and were zero filled to 65,536 data points before Fourier transformation.

Confocal laser-scanning microscopy

Cells grown on coverslips coated with poly-l-lysine were transfected with a plasmid encoding GFP-RILP using the CHO Trans-IT or 293 Trans-IT (MirusBio) transfection reagents. All CHO cell lines had similar levels of transfection efficiency and gene expression as measured by control GFP and luciferase test transfections. Transfected cells were incubated for 12 h at 37°C. As indicated, cells were treated for 30 min with 100 μM nocodazole (Sigma-Aldrich), 40 μM cytochalasin D (Sigma-Aldrich), or DMSO vehicle. For localization experiments, cells were fixed with 3% PFA, perforated with 0.5% β-escin, stained with anti-FLAG antibody (Sigma-Aldrich), antitransferrin (Abcam), anti-RhoB (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), anti-furin (R&D Systems), or anti-p150Glued (BD Biosciences), and followed by a Rhodamine red X–conjugated secondary antibody (Jackson Immunochemicals) and DAPI. For vesicle size measurements, cells were fixed with 3% PFA and stained with DAPI. Cells were examined with a confocal microscope (TCS SP2 with AOBS; Leica) using the 405-nm wavelength line of a UV laser and the 488/568-nm lines of an argon-krypton laser. Image resolution using a 100× 1.4 NA oil immersion lens (Leica) and LCS software (Leica) was 512 × 512 pixels. Images were analyzed with MetaMorph software (MDS Analytical Technologies).

Statistical analysis

A mixed effects ANOVA model, with cell type being treated as a fixed effect and the individual cells considered random effects nested within cell type, was selected to model the data. Two responses were considered: (1) ratio of vesicle size to cell area and (2) ratio of vesicle perimeter to cell perimeter. Preliminary investigation of these responses indicated that a log transformation would be necessary to satisfy the normal error assumption of the ANOVA model. This model can be described as log(yijk) = μ + αi + bj (i) + ɛijk, where yijk denotes the kth response of the ith cell type and the jth cell within the ith cell type. The overall mean effect is given by μ; α refers to the fixed cell type effect, and b is the random cell within the cell type effect. The normal residual error of the model is denoted by ɛ.

Rab7 depletion

A549 cell transfections were performed using the Nucleofecter I system (Amaxa Biosystems) according to the protocol for solution T. Approximately 106 A549, A549-RIDα, or A549-75AA cells were transfected with 10 or 20 pg Rab7 siRNA specifically targeting human Rab7 (Dharmacon), or 2 μg of plasmid DNA encoding GFP, GFP-Rab7(Q67L), GFP-Rab7(N125I), GFP-Rab7(T22N), or GFP-RILP. Protein expression was determined with an anti-Rab7 antibody or anti-GFP antibody (Sigma-Aldrich) followed by HRP-conjugated secondary antibody and ECL substrate (GE Healthcare). We used constructs expressing GFP fusion proteins to verify similar transfection efficiencies in all test conditions.

LDL degradation

LDL was labeled with 125I using a chloramine-T–based labeling procedure. In brief, 500 μg LDL at 5 mg/ml (Athens Research and Technology) was combined with 2 mCi of free 125I in 500 μl of 250-μM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, and incubated with 150 μl of 5-mg/ml chloramine-T in phosphate buffer for 30 s. The reaction was stopped with N2S2O5 and NaI. 125I-labeled LDL was separated from free 125I by running the reaction through a Sephadex G-25 desalting column (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Transfected cells were split into a six-well plate and incubated for 24 h in media supplemented with LDL-deficient serum (Sigma-Aldrich). The degradation assay was performed as previously described (Goldstein et al., 1983; Cantalupo et al., 2001). In brief, cells were incubated with 50 μg/ml 125I-LDL for 6 h. Cell culture supernatant was collected, and the amount of degraded 125I-LDL was determined as described previously (Brown and Goldstein, 1975). Duplicate transfections were analyzed for total 125I-LDL that was surface bound 30 min after the addition of 125I-LDL on ice, and total 125I-LDL internalized at 1 h. All measurements are presented as a percentage of mock or control pGFP-transfected A549 cells. Experiments were performed in triplicate on two separate occasions and are presented as a mean of all experiments with SDs. Analysis of significance was performed with a t test.

Flow cytometry

Cells were infected at 200 MOI with adenovirus dl753 (Carlin et al., 1989), rec700, or pantropic retroviruses expressing RIDα (retroN RIDα) or RIDα(75AA) (retroN RIDα(75AA)). Cells were harvested at 20 h after infection using 0.025% EDTA in PBS. Cells were washed with PBS supplemented with 0.5% FBS (PBS-FACS) and incubated with 1% normal goat serum for 30 min to block nonspecific binding of the secondary antibody. All subsequent washes were performed with PBS-FACS. EGFR cell surface expression was determined using 1 μg/ml anti-EGFR monoclonal antibody EGFR1 followed by 1 μg/ml FITC-conjugated goat anti– mouse antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories). Fas cell surface expression was determined using a FITC-conjugated anti-Fas antibody (Novus Biologicals). Cell-associated FITC activity was determined using a flow cytometer (LSR I; BD Biosciences) and CellQuest software (BD Biosciences).

Metabolic labeling

Cells were rinsed twice and preincubated in methionine and cysteine-free medium for 1 h followed by a 3-h incubation with 1,175 Ci/mmol [35S]Express Protein Labeling Mix (New England Nuclear Research Products) diluted in the amino acid–deficient medium supplemented with 10% dialyzed FBS and 0.2% BSA. Radiolabeled cells were rinsed three times with PBS and lysed with 1% (wt/vol) Triton X-100 in 0.1 M Tris, pH 7.4, supplemented with 2 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 0.2 mM PMSF, and 1 μM leupeptin for immunoprecipitation with previously described rabbit peptide antibodies to individual RID complex components (Tollefson et al., 1990; Hoffman et al., 1992b).

Acknowledgments

We extend special thanks to Professor Stephen Ganocy for assistance with statistical analysis. We thank Dr. Cecilia Bucci, Dr. Vesa Olkkonen, Dr. Tracy Mourton, and Dr. Jim Crish for technical guidance and Dr. Song Jae Kil for helpful discussions.

This research was supported by the Flow Cytometry Core Facility of the Comprehensive Cancer Center of Case Western Reserve University and University Hospitals of Cleveland (grant P30 CA43703). This work was supported by Public Health Service grant RO1 GM64243 to C. Carlin. A.H. Shah was supported, in part, by a Cell and Molecular Biology training grant awarded through the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, and N.L. Cianciola was supported by grant T32 DK07678.

Abbreviations used in this paper: ANOVA, analysis of variance; DN, dominant negative; E3, early region 3; EGFR, EGF receptor; Hsp, heat-shock protein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; MTOC, microtubule organizing center; MVB, multivesicular body; NMR, nuclear magnetic resonance; ORP, oxysterol-binding protein–related protein; RID, receptor internalization and degradation; RILP, Rab7-interacting lysosomal protein; TNFR1, TNF receptor 1; TRAIL-R, TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand receptor.

References

- Agarraberes, F.A., and J.F. Dice. 2001. A molecular chaperone complex at the lysosomal membrane is required for protein translocation. J. Cell Sci. 114:2491–2499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin, C.D., A.M. De Maziere, P.I. Pisacane, S.M. van Dijk, C. Eigenbrot, M.X. Sliwkowski, J. Klumperman, and R.H. Scheller. 2004. Endocytosis and sorting of ErbB2 and the site of action of cancer therapeutics trastuzumab and geldanamycin. Mol. Biol. Cell. 15:5268–5282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, M.S., and J.L. Goldstein. 1975. Regulation of the activity of the low density lipoprotein receptor in human fibroblasts. Cell. 6:307–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, V., R.A. Brown, A. Ozinsky, J.R. Hesselberth, and S. Fields. 2006. Binding specificity of Toll-like receptor cytoplasmic domains. Eur. J. Immunol. 36:742–753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucci, C., R.G. Parton, I.H. Mather, H. Stunnenberg, K. Simons, B. Hoflack, and M. Zerial. 1992. The small GTPase rab5 functions as a regulatory factor in the early endocytic pathway. Cell. 70:715–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucci, C., P. Thomsen, P. Nicoziani, J. McCarthy, and B. van Deurs. 2000. Rab7: a key to lysosome biogenesis. Mol. Biol. Cell. 11:467–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantalupo, G., P. Alifano, V. Roberti, C.B. Bruni, and C. Bucci. 2001. Rab-interacting lysosomal protein (RILP): the Rab7 effector required for transport to lysosomes. EMBO J. 20:683–693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlin, C.R., A.E. Tollefson, H.A. Brady, B.L. Hoffman, and W.S. Wold. 1989. Epidermal growth factor receptor is down-regulated by a 10,400 MW protein encoded by the E3 region of adenovirus. Cell. 57:135–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceresa, B.P., and S.J. Bahr. 2006. rab7 activity affects epidermal growth factor:epidermal growth factor receptor degradation by regulating endocytic trafficking from the late endosome. J. Biol. Chem. 281:1099–1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin, Y.R., and M.S. Horwitz. 2005. Mechanism for removal of tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 from the cell surface by the adenovirus RIDalpha/beta complex. J. Virol. 79:13606–13617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cianciola, N.L., D. Crooks, A.H. Shah, and C. Carlin. 2007. A tyrosine-based signal plays a critical role in the targeting and function of adenovirus RID{alpha} protein. J. Virol. 81:10437–10450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crooks, D., S.J. Kil, J.M. McCaffery, and C. Carlin. 2000. E3-13.7 integral membrane proteins encoded by human adenoviruses alter epidermal growth factor receptor trafficking by interacting directly with receptors in early endosomes. Mol. Biol. Cell. 11:3559–3572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Matteis, M.A., and J.S. Morrow. 2000. Spectrin tethers and mesh in the biosynthetic pathway. J. Cell Sci. 113:2331–2343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong, J., W. Chen, A. Welford, and A. Wandinger-Ness. 2004. The proteasome alpha-subunit XAPC7 interacts specifically with Rab7 and late endosomes. J. Biol. Chem. 279:21334–21342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsing, A., and H.G. Burgert. 1998. The adenovirus E3/10.4K-14.5K proteins down-modulate the apoptosis receptor Fas/Apo-1 by inducing its internalization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 95:10072–10077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Y., B. Press, and A. Wandinger-Ness. 1995. Rab 7: an important regulator of late endocytic membrane traffic. J. Cell Biol. 131:1435–1452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fessler, S.P., Y.R. Chin, and M.S. Horwitz. 2004. Inhibition of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) signal transduction by the adenovirus group C RID complex involves downregulation of surface levels of TNF receptor 1. J. Virol. 78:13113–13121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garnett, C.T., D. Erdman, W. Xu, and L.R. Gooding. 2002. Prevalence and quantitation of species C adenovirus DNA in human mucosal lymphocytes. J. Virol. 76:10608–10616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginsberg, H.S. 1999. The life and times of adenoviruses. Adv. Virus Res. 54:1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein, J.L., S.K. Basu, and M.S. Brown. 1983. Receptor-mediated endocytosis of low-density lipoprotein in cultured cells. Methods Enzymol. 98:241–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez, P.F., D. Luo, K. Hirosaki, K. Shinoda, T. Yamashita, J. Suzuki, K. Otsu, K. Ishikawa, and K. Jimbow. 2001. Identification of rab7 as a melanosome-associated protein involved in the intracellular transport of tyrosinase-related protein 1. J. Invest. Dermatol. 117:81–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gooding, L.R., and W.S. Wold. 1990. Molecular mechanisms by which adenoviruses counteract antiviral immune defenses. Crit. Rev. Immunol. 10:53–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosshans, B.L., D. Ortiz, and P. Novick. 2006. Rabs and their effectors: achieving specificity in membrane traffic. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 103:11821–11827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruenberg, J. 2001. The endocytic pathway: a mosaic of domains. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2:721–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez, M.G., D.B. Munafo, W. Beron, and M.I. Colombo. 2004. Rab7 is required for the normal progression of the autophagic pathway in mammalian cells. J. Cell Sci. 117:2687–2697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilgendorf, A., J. Lindberg, Z. Ruzsics, S. Honing, A. Elsing, M. Lofqvist, H. Engelmann, and H.G. Burgert. 2003. Two distinct transport motifs in the adenovirus E3/10.4-14.5 proteins act in concert to down-modulate apoptosis receptors and the epidermal growth factor receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 278:51872–51884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, B.L., A. Ullrich, W.S. Wold, and C.R. Carlin. 1990. Retrovirus-mediated transfer of an adenovirus gene encoding an integral membrane protein is sufficient to down regulate the receptor for epidermal growth factor. Mol. Cell. Biol. 10:5521–5524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, P., and C. Carlin. 1994. Adenovirus E3 protein causes constitutively internalized epidermal growth factor receptors to accumulate in a prelysosomal compartment, resulting in enhanced degradation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14:3695–3706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, P., P. Rajakumar, B. Hoffman, R. Heuertz, W.S. Wold, and C.R. Carlin. 1992. a. Evidence for intracellular down-regulation of the epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptor during adenovirus infection by an EGF-independent mechanism. J. Virol. 66:197–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, P., M.B. Yaffe, B.L. Hoffman, S. Yei, W.S. Wold, and C. Carlin. 1992. b. Characterization of the adenovirus E3 protein that down-regulates the epidermal growth factor receptor. Evidence for intermolecular disulfide bonding and plasma membrane localization. J. Biol. Chem. 267:13480–13487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holleran, E.A., L.A. Ligon, M. Tokito, M.C. Stankewich, J.S. Morrow, and E.L.F. Holzbaur. 2001. beta III spectrin binds to the Arp1 subunit of dynactin. J. Biol. Chem. 276:36598–36605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath, J., L. Palkonyay, and J. Weber. 1986. Group C adenovirus DNA sequences in human lymphoid cells. J. Virol. 59:189–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz, M.S. 2004. Function of adenovirus E3 proteins and their interactions with immunoregulatory cell proteins. J. Gene Med. 6:S172–S183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaworski, C.J., E. Moreira, A. Li, R. Lee, and I.R. Rodriguez. 2001. A family of 12 human genes containing oxysterol-binding domains. Genomics. 78:185–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon, H., and S.C. Blacklow. 2005. Structure and physiologic function of the low-density lipoprotein receptor. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 74:535–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson, M., V. Bocher, M. Lehto, G. Chinetti, E. Kuismanen, C. Ehnholm, B. Staels, and V.M. Olkkonen. 2003. The two variants of oxysterol binding protein-related protein-1 display different tissue expression patterns, have different intracellular localization, and are functionally distinct. Mol. Biol. Cell. 14:903–915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson, M., M. Lehto, K. Tanhuanpaa, T.L. Cover, and V.M. Olkkonen. 2005. The oxysterol-binding protein homologue ORP1L interacts with Rab7 and alters functional properties of late endocytic compartments. Mol. Biol. Cell. 16:5480–5492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson, M., N. Rocha, W. Zwart, I. Jordens, L. Janssen, C. Kuijl, V.M. Olkkonen, and J. Neefjes. 2007. Activation of endosomal dynein motors by stepwise assembly of Rab7-RILP-p150Glued, ORP1L, and the receptor βlll spectrin. J. Cell Biol. 176:459–471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordens, I., M. Fernandez-Borja, M. Marsman, S. Dusseljee, L. Janssen, J. Calafat, H. Janssen, R. Wubbolts, and J. Neefjes. 2001. The Rab7 effector protein RILP controls lysosomal transport by inducing the recruitment of dynein-dynactin motors. Curr. Biol. 11:1680–1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kil, S.J., M. Hobert, and C. Carlin. 1999. A leucine-based determinant in the epidermal growth factor receptor juxtamembrane domain is required for the efficient transport of ligand-receptor complexes to lysosomes. J. Biol. Chem. 274:3141–3150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.J., and M.P. Foster. 2002. Characterization of Ad5 E3-14.7K, an adenoviral inhibitor of apoptosis: structure, oligomeric state, and metal binding. Protein Sci. 11:1117–1128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuivinen, E., B.L. Hoffman, P.A. Hoffman, and C.R. Carlin. 1993. Structurally related class I and class II receptor protein tyrosine kinases are down-regulated by the same E3 protein coded for by human group C adenoviruses. J. Cell Biol. 120:1271–1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehto, M., S. Laitinen, G. Chinetti, M. Johansson, C. Ehnholm, B. Staels, E. Ikonen, and V.M. Olkkonen. 2001. The OSBP-related protein family in humans. J. Lipid Res. 42:1203–1213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, G., M.A. Barbieri, M.I. Colombo, and P.D. Stahl. 1994. Structural features of the GTP-binding defective Rab5 mutants required for their inhibitory activity on endocytosis. J. Biol. Chem. 269:14631–14635. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenstein, D.L., K. Doronin, K. Toth, M. Kuppuswamy, W.S. Wold, and A.E. Tollefson. 2004. a. Adenovirus E3-6.7K protein is required in conjunction with the E3-RID protein complex for the internalization and degradation of TRAIL receptor 2. J. Virol. 78:12297–12307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenstein, D.L., K. Toth, K. Doronin, A.E. Tollefson, and W.S. Wold. 2004. b. Functions and mechanisms of action of the adenovirus E3 proteins. Int. Rev. Immunol. 23:75–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim, C.M., M.A. Cater, J.F. Mercer, and S. La Fontaine. 2006. Copper-dependent interaction of dynactin subunit p62 with the N terminus of ATP7B but not ATP7A. J. Biol. Chem. 281:14006–14014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mascia, F., V. Mariani, G. Girolomoni, and S. Pastore. 2003. Blockade of the EGF receptor induces a deranged chemokine expression in keratinocytes leading to enhanced skin inflammation. Am. J. Pathol. 163:303–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNees, A.L., C.T. Garnett, and L.R. Gooding. 2002. The adenovirus E3 RID complex protects some cultured human T and B lymphocytes from Fas-induced apoptosis. J. Virol. 76:9716–9723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno, K., A. Kitamura, and T. Sasaki. 2003. Rabring7, a novel Rab7 target protein with a RING finger motif. Mol. Biol. Cell. 14:3741–3752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Progida, C., M.R. Spinosa, A. De Luca, and C. Bucci. 2006. RILP interacts with the VPS22 component of the ESCRT-II complex. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 347:1074–1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, E.A., J. Chua, G.B. Kyei, and V. Deretic. 2006. Higher order Rab programming in phagolysosome biogenesis. J. Cell Biol. 174:923–929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shisler, J., C. Yang, B. Walter, C.F. Ware, and L.R. Gooding. 1997. The adenovirus E3-10.4K/14.5K complex mediates loss of cell surface Fas (CD95) and resistance to Fas-induced apoptosis. J. Virol. 71:8299–8306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinz, A., A.J. Jin, and O. Zschornig. 2003. Evaluation of the metal binding properties of a histidine-rich fusogenic peptide by electrospray ionization Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry. J. Mass Spectrom. 38:1150–1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein, M.P., Y. Feng, K.L. Cooper, A.M. Welford, and A. Wandinger-Ness. 2003. Human VPS34 and p150 are Rab7 interacting partners. Traffic. 4:754–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenmark, H., and V.M. Olkkonen. 2001. The Rab GTPase family. Genome Biol. 2:REVIEWS3007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, A.R., A.E. Tollefson, P. Krajcsi, S.P. Yei, and W.S. Wold. 1995. The adenovirus E3 10.4K and 14.5K proteins, which function to prevent cytolysis by tumor necrosis factor and to down-regulate the epidermal growth factor receptor, are localized in the plasma membrane. J. Virol. 69:172–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tollefson, A.E., P. Krajcsi, M.H. Pursley, L.R. Gooding, and W.S. Wold. 1990. A 14,500 MW protein is coded by region E3 of group C human adenoviruses. Virology. 175:19–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tollefson, A.E., A.R. Stewart, S.P. Yei, S.K. Saha, and W.S. Wold. 1991. The 10,400- and 14,500-dalton proteins encoded by region E3 of adenovirus form a complex and function together to down-regulate the epidermal growth factor receptor. J. Virol. 65:3095–3105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tollefson, A.E., T.W. Hermiston, D.L. Lichtenstein, C.F. Colle, R.A. Tripp, T. Dimitrov, K. Toth, C.E. Wells, P.C. Doherty, and W.S. Wold. 1998. Forced degradation of Fas inhibits apoptosis in adenovirus-infected cells. Nature. 392:726–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tollefson, A.E., K. Toth, K. Doronin, M. Kuppuswamy, O.A. Doronina, D.L. Lichtenstein, T.W. Hermiston, C.A. Smith, and W.S. Wold. 2001. Inhibition of TRAIL-induced apoptosis and forced internalization of TRAIL receptor 1 by adenovirus proteins. J. Virol. 75:8875–8887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich, A.S., M. Otter, C.G. Glabe, and D. Hoekstra. 1998. Membrane fusion is induced by a distinct peptide sequence of the sea urchin fertilization protein bindin. J. Biol. Chem. 273:16748–16755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinogradova, O., C. Carlin, F.D. Sonnichsen, and C.R. Sanders II. 1998. A membrane setting for the sorting motifs present in the adenovirus E3-13.7 protein which down-regulates the epidermal growth factor receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 273:17343–17350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitelli, R., M. Santillo, D. Lattero, M. Chiariello, M. Bifulco, C.B. Bruni, and C. Bucci. 1997. Role of the small GTPase Rab7 in the late endocytic pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 272:4391–4397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T., and W. Hong. 2006. RILP interacts with VPS22 and VPS36 of ESCRT-II and regulates their membrane recruitment. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 350:413–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T., K.K. Wong, and W. Hong. 2004. A unique region of RILP distinguishes it from its related proteins in its regulation of lysosomal morphology and interaction with Rab7 and Rab34. Mol. Biol. Cell. 15:815–826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, M., T. Wang, E. Loh, W. Hong, and H. Song. 2005. Structural basis for recruitment of RILP by small GTPase Rab7. EMBO J. 24:1491–1501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S., S. Qu, M. Perez-Tores, A. Sawai, N. Rosen, D.B. Solit, and C.L. Arteaga. 2006. Association with HSP90 inhibits Cbl-mediated down-regulation of mutant epidermal growth factor receptors. Cancer Res. 66:6990–6997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanardi, T.A., S. Yei, D.L. Lichtenstein, A.E. Tollefson, and W.S. Wold. 2003. Distinct domains in the adenovirus E3 RIDalpha protein are required for degradation of Fas and the epidermal growth factor receptor. J. Virol. 77:11685–11696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]