Abstract

Retrograde transport allows proteins and lipids to leave the endocytic pathway to reach other intracellular compartments, such as TGN/Golgi membranes, the endoplasmic reticulum, and in some instances, the cytosol. Here, we have used RNA interference against the SNARE proteins syntaxin 5 and syntaxin 16 combined with recently developed quantitative trafficking assays, morphological approaches, and cell intoxication analysis to show that these SNARE proteins are not only required for efficient retrograde transport of Shiga toxin, but also for that of an endogenous cargo protein, the mannose 6-phosphate receptor, and for the productive trafficking into cells of cholera toxin and ricin. We have found that the function of syntaxin 16 was specifically required for, and restricted to the retrograde pathway. Strikingly, syntaxin 5 RNA interference protected cells particularly strongly against Shiga toxin. Since our trafficking analysis showed that apart from inhibiting retrograde endosomes-to-TGN transport, the silencing of syntaxin 5 had no additional effect on Shiga toxin endocytosis or trafficking from TGN/Golgi membranes to the endoplasmic reticulum, we hypothesize that syntaxin 5 also has trafficking-independent functions. In summary, our data demonstrate that several cellular and exogenous cargo proteins use elements of the same SNARE machinery for efficient retrograde transport between early/recycling endosomes and TGN/Golgi membranes.

Keywords: Protein toxin, Shiga toxin, cholera toxin, ricin, retrograde transport, membrane traffic, SNARE, endosome, Golgi

Introduction

Shiga toxin (STx), produced by Shigella dysenteriae, and the virtually identical Shiga-like toxins (SLTx) from enterohemorrhagic strains of Escherichia coli, are A-B toxins, in which a catalytically active A-subunit interacts with, in this case, five receptor binding B-fragments forming the homo-pentameric B-subunit (STxB). The A-subunits of these toxins have N-glycanase activity that inhibits protein synthesis through a specific depurination of the large ribosomal RNA (Endo et al., 1988). STx is associated with bacillary dysentery while the SLTx proteins have a role in the pathological manifestations of hemorrhagic colitis and haemolytic uremic syndrome, a leading causes for pediatric renal failure (Peacock et al., 2001). Other members of the A-B protein toxin family include cholera toxin (CTx), ricin, Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin, and Pseudomonas exotoxin A, which, like STx/SLTx, reach their cytosolic targets by retrotranslocation from the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (Lord et al., 2003).

STxB is responsible for high-affinity binding to the toxin's cell surface receptor globotriaosyl ceramide, Gb3/CD77 (Lingwood, 1993), and for subsequent internalization. From early/recycling endosomes (EE/RE), STxB has been described to leave the endocytic pathway (Mallard et al., 1998) and to be targeted to the ER (Johannes et al., 1997; Sandvig et al., 1992), via the Golgi apparatus (for review, see (Johannes and Decaudin, 2005; Sandvig et al., 2004; Smith et al., 2004)). For reasons such as the abundance of its cellular receptor and the possibility to synchronize its cellular uptake at the plasma membrane and the EE/RE, STxB has turned out to be a suitable marker for studying retrograde transport, and innovative quantitative and morphological tools have been developed to this end (reviewed in (Amessou et al., in press; Mallard and Johannes, 2003; Tai et al., 2005)).

The molecular machinery underlying the newly described EE/RE-to-TGN transport step is currently being identified. Retrograde sorting of STxB from EE/RE depends on clathrin (Lauvrak et al., 2004; Saint-Pol et al., 2004) and the putative clathrin adaptor epsinR (Saint-Pol et al., 2004). It also involves membrane microdomain organization (Falguières et al., 2001) and GPP130 (Natarajan and Linstedt, 2004), a Golgi protein of unknown function. Targeting and fusion of EE/RE-derived, STxB-containing transport intermediates with Golgi/TGN membranes is regulated by the small GTPase Rab6a', the putative TGN tethering molecule golgin-97 (Lu et al., 2004), and by two soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive fusion protein attachment protein receptor (SNARE) complexes that include the heavy chain tSNAREs syntaxin 16 (Mallard et al., 2002) and syntaxin 5 (Tai et al., 2004).

SNAREs are trans-membrane proteins that are essential for membrane fusion and that contribute to the specificity of this process (Chen and Scheller, 2001; Jahn and Grubmuller, 2002; Pelham and Rothman, 2000). These functions are driven by a specific pairing of four coiled coil domains contributed by a VAMP (vesicle or R-SNARE), a syntaxin (target or Qa SNARE) and one or two proteins that contribute two coiled coils (Qb-Qc SNAREs). Several SNARE proteins have been described that can be found within Golgi membranes (Chen and Scheller, 2001). These include five syntaxins: syntaxin 5 (Bennett et al., 1993; Hay et al., 1998), syntaxin 6 (Bock et al., 1996), syntaxin 10 (Tang et al., 1998b), syntaxin 11 (Valdez et al., 1999), and syntaxin 16 (Tang et al., 1998a). The two involved in retrograde transport to the TGN, syntaxin 5 (Syn5) and syntaxin 16 (Syn16), are found in different SNARE complexes: Syn16 associates with syntaxin 6 and Vti1a to form a tSNARE complex at the TGN whose physical and functional interaction with the endosomal vSNARE VAMP4, and to a lesser extent with VAMP3, regulates retrograde transport (Mallard et al., 2002). Syn5 has been described in two different molecular environments, one as part of a Syn5/GS27/Sec22/Bet1 complex at the cis-Golgi-ER interface (Hay et al., 1998), and the other as a component of a Syn5/GS28/Ykt6/GS15 complex on Golgi membranes (Hay et al., 1998; Xu et al., 2002). The latter complex has been ascribed a role in retrograde transport to the TGN (Tai et al., 2004).

The discovery of at least two SNARE complexes that are involved in retrograde transport at the EE/RE-TGN interface raises a number of questions, including whether these complexes have cargo specific functions. It has already been shown that Syn16 function is required for the retrograde trafficking of STxB, the cellular protein TGN38/46, of unknown function, and the mannose 6-phosphate receptor (MPR) that shuttles lysosomal enzymes between TGN and endosomes/lysosomes (Mallard et al., 2002; Saint-Pol et al., 2004). Syn5 functions in the retrograde trafficking of STxB (Tai et al., 2004). In the comparative study here, we have chosen to inhibit Syn5 and Syn16 functions in HeLa cells by RNA interference (RNAi) to silence their expression. Using protein sulfation methodology (Amessou et al., in press; Mallard and Johannes, 2003) in combination with cell intoxication assays and immunofluorescence, we have analyzed the retrograde traffic of the endogenous cargo protein MPR, and three exogenous cargoes, STxB, CTxB and ricin, under RNAi conditions. We report that the intracellular transport of all these proteins was similarly sensitive to an interference with Syn5 and Syn16 expression. In the case of Syn16, the RNAi effect was highly selective for retrograde transport in that transferrin recycling, transport and degradation of EGF in lysosomes, and biosynthetic/secretory VSV-G transport to the plasma membrane were not affected. Surprisingly, when cytotoxicity rather than retrograde transport was monitored, we discovered that RNAi against Syn5 disrupted intoxication most strikingly when cells were challenged with STx. RNAi against a further member of the Golgi/TGN Syn5 SNARE complex, GS15, did not produce this strong protective phenotpye. These observations suggest that knock down of Syn5 levels limits the activity of a STx-specific factor required, not for transport, but in a downstream step following initial delivery of this toxin into the ER lumen. Apart from this difference, it is clear from our study that several exogenous and endogenous markers share the same SNARE machinery for efficient retrograde transport from endosomes to Golgi/TGN membranes.

Results

Specific inhibition of retrograde transport of STxB in Syn16 RNAi conditions

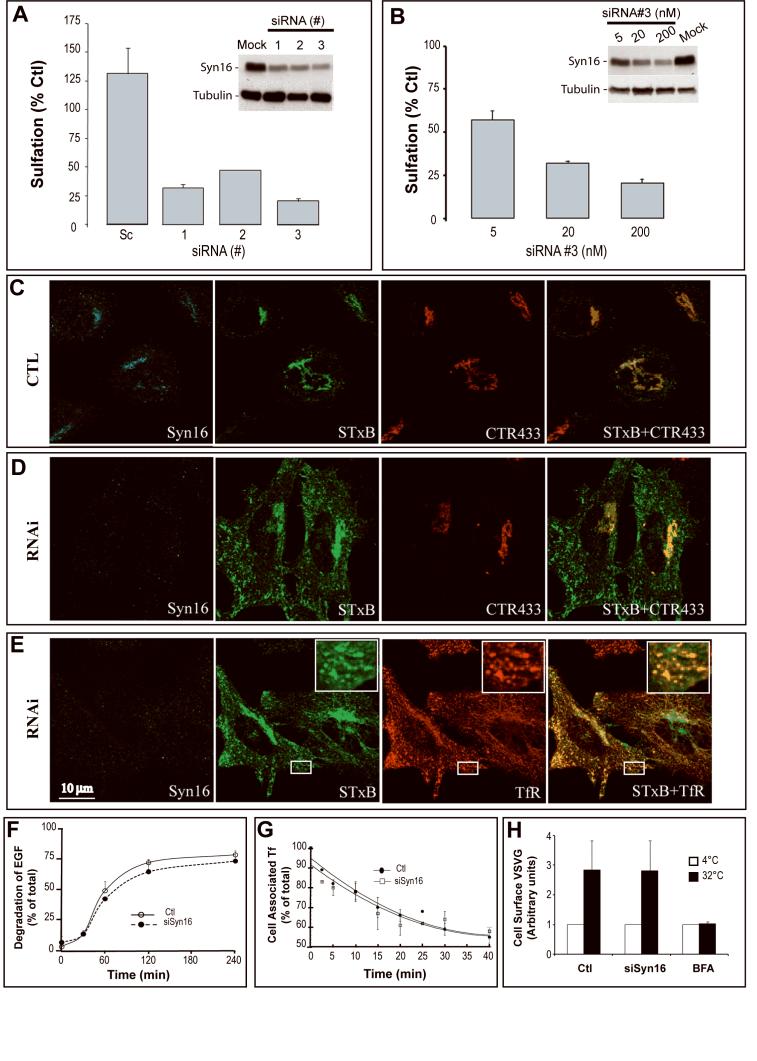

Our previous studies have implicated Syn16 in retrograde transport to the TGN as part of a SNARE complex composed of Syn16, syntaxin 6, Vti1a, and the vSNAREs VAMP4 or VAMP3 (Mallard et al., 2002). However in this earlier report, a functional requirement for Syn16 in retrograde transport was not addressed. Using RNAi, we show here that in agreement with some recent studies (Smith et al., 2006b; Wang et al., 2005), Syn16 is indeed required. Three different small interfering RNA (siRNA) duplexes down-modulated Syn16 expression (Fig. 1A, inset). We then used sulfation analysis to quantify arrival of STxB in TGN/Golgi membranes under these conditions. This assay exploits TGN-localized sulfotransferase activity ((Johannes et al., 1997; Mallard et al., 1998); detailed in (Mallard and Johannes, 2003)). Upon retrograde transport to the TGN of the sulfation site-tagged STxB variant STxB-Sulf2, tyrosyl sulfotransferase catalyzes addition of radioactive sulfate, and following immunoprecipitation, sulfated STxB-Sulf2 is detected and quantified by electrophoresis and autoradiography. Transfection of the three anti-Syn16 siRNAs led in all cases to an inhibition of retrograde transport, when compared to mock (set to 100%) or scrambled siRNA transfected control cells (Fig. 1A). The specificity of the RNAi effect was further demonstrated by showing a dose-dependency of retrograde transport inhibition, using siRNA sequence 3 (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

Specific inhibition of retrograde transport of STxB in Syn16 RNAi conditions. (A) Metabolic sulfation of internalized STxB-Sulf2 on HeLa cells over a 20 min period was visualized by immunoprecipitation from cells that had been transfected for 72 hours with three different siRNAs against Syn16 or with scrambled (Sc) siRNA (200 nM each). Data are expressed as percentages of STxB-Sulf2 sulfation for each experimental condition, using sulfation of STxB-Sulf2 on mock-transfected cells as the reference (set to 100%), and normalized for total sulfation counts (see Materials and Methods and Figures 2C). Inset: Western blotting confirmed the down-modulation of Syn16 in these conditions. Tubulin was used as a loading control. (B) Sulfation analysis as in (A) of STxB-Sulf2 applied to HeLa cells that had been transfected for 72 hours with increasing doses of anti-Syn16 siRNA #3. Inset: Western blot of Syn16 in the indicated conditions. (C-E) Immunofluorescence analysis of retrograde STxB transport in (C) mock-transfected control (CTL) and (D-E) Syn16 RNAi cells (siRNA sequence #3 at 200 nM). In all conditions fluorophore-labeled STxB (green) was internalized for 45 min at 37°C. Cells were fixed and labeled for Syn16 (blue), the Golgi marker CTR433 (red, D), or TfR (red, E). Under Syn16 RNAi conditions, STxB accumulation in the Golgi was reduced, and the protein appeared in peripheral structures where it co-distributed with the TfR. Space bar = 10 μm. (F-H) Specificity controls for the Syn16 RNAi. (F) EGF degradation. 2.5 ng/ml of iodine-labeled EGF was incubated for the indicated times with HeLa cells in the indicated conditions. Lysosomal degradation was measured by appearance of TCA-soluble counts in the culture medium (G) Tf recycling. Biotin-tagged Tf was internalized at 37°C for 40 min into HeLa cells in the indicated conditions. Cells were washed, and further incubated as shown at 37°C. Remaining cell associated Tf was determined by ELISA. In F-G, means of 3-4 independent experiments are shown. (H) VSVG transport in the biosynthetic and/or secretory pathway. The trafficking of newly synthesized VSVG-ts045 to the plasma membrane was analyzed by cell surface biotinylation after a temperature shift from 37°C to 32°C. BFA was used as a specificity control.

Immunofluorescence analysis was used to analyze the site of STxB accumulation in Syn16 RNAi cells. In control cells (Fig. 1C), STxB (green) was efficiently transported to TGN/Golgi membranes and colocalized with the Golgi cisternal marker CTR433 (red). In the same cells, immunolabeled Syn16 (blue) was readily detected in co-distribution with CTR433. By contrast, in siRNA transfected cells (Fig. 1D-E), the Syn16 signal (blue) was clearly decreased. STxB (green) was detectable in peripheral structures that were also positive for the transferrin receptor (TfR; red, Fig. 1E), a marker of EE/RE. It was noticeable that in Syn16 RNAi cells, STxB (green) also remained concentrated in a perinuclear localization close to the Golgi apparatus (CTR433; red, Fig. 1D). Whether STxB was actually in Golgi cisternae, due to incomplete inhibition of retrograde transport, or whether it accumulated close to Golgi cisternae could not be distinguised at this level of resolution. Of note in Syn16 RNAi cells, was the perinuclear localization of TfR, something normally not evident in HeLa cells (Lin et al., 2002). In addition, in some cells, TfR-positive tubules emanated from the perinuclear site, which also contained STxB (Fig. 1E).

We tested the specificity of the Syn16 RNAi effect on retrograde transport using three markers that traffic through organelles that constitute the EE/RE-TGN interface. In interaction with its receptor, epidermal growth factor (EGF) is internalized by clathrin-dependent endocytosis into EE and targeted to late endosomes/lysosomes for degradation (Wiley and Burke, 2001). We found here that degradation of this protein, as measured by the appearance of acid soluble counts in the cell culture medium (Mallard et al., 1998), was largely unaffected in Syn16 RNAi cells (Fig. 1F). This suggested that trafficking through the endocytic pathway was functionally unperturbed. Next, we observed that transferrin (Tf) recycling from EE/RE back to the plasma membrane was similar in control and Syn16 RNAi cells (Fig. 1G). Finally, a model cargo, vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein (VSVG), was used to assess the effect of Syn16 RNAi on anterograde trafficking along the biosynthetic and/or secretory pathway to the plasma membrane, via the TGN (Fig. 1H). Again, no difference in trafficking was observed. The validity of the assay was confirmed by showing that BFA could totally inhibit the transport of VSVG (Fig. 1H, right column). We also demonstrated that cell surface binding sites and apparent affinity of STxB for cells were not altered in Syn16 RNAi cells, when compared to mock-transfected control cells (Table 1). Taken together, these data demonstrate that Syn16 is specifically required for efficient retrograde STxB transport from EE/RE to the TGN.

Table 1.

Scatchard analysis on cells in the indicated control and RNAi conditions.

| Mock-transfected | siSyn5 | siSyn16 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| kd (nM) | 54 | 28 | 47 |

| Binding sites (×108) per cell | 2.8 | 3.0 | 2.9 |

HeLa cells were mock-transfected or transfected with siRNAs at 200 nM against the indicated proteins. Three days after transfection, the cells were placed on ice and Scatchard analysis was performed as described previously (Falguières et al., 2001).

Specific function of Syn5 in the EE/RE-to-TGN transport step of the retrograde pathway

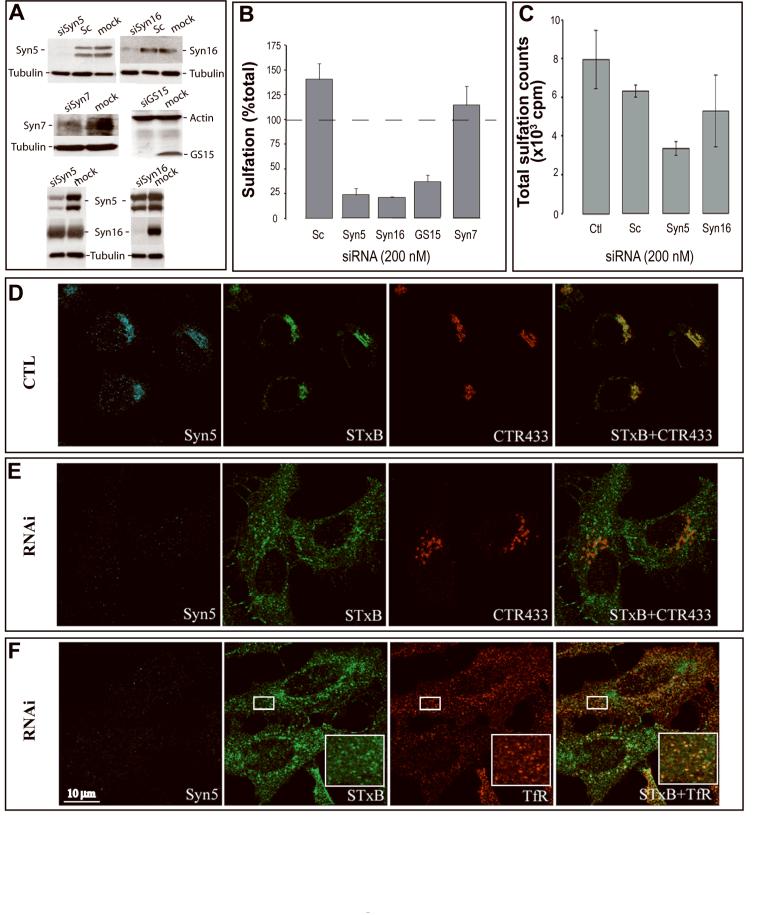

In addition to the Syn16 containing SNARE complexes (Mallard et al., 2002), Syn5 and GS15 have recently been identified as further molecular players at the EE/RE-TGN interface (Tai et al., 2004). We used siRNAs as described by Hong and colleagues (Tai et al., 2004) and developed new ones that allowed robust knock down of Syn5 and GS15 (Fig. 2A). We also showed that down-modulating Syn16 expression had no effect on Syn5, and vice versa (Fig. 2A, lower panels), suggesting that loss of one complex is not compensated by the upregulation of the other one. Monitoring sulfation, we found that Syn5 and GS15 RNAi induced a strong inhibition of retrograde transport of STxB, when compared to mock-transfected control cells (set to 100%) or scrambled siRNA transfected cells (Fig. 2B). The levels of inhibition were similar to those observed with Syn16 RNAi (Fig. 2B). To control for specificity, we showed that RNAi against the late endosomal tSNARE Syn7 did not affect retrograde transport of STxB (Fig. 2B), despite efficient down-modulation of the Syn7 target protein (Fig. 2A). Similarly, interfering with the function of the TGN-localized tSNARE Syn10 did not prevent STxB from reaching TGN membranes (Wang et al., 2005). The analysis of sulfation signals on endogenous proteins revealed that these were partially affected in the Syn5 RNAi condition (Fig. 2C), suggesting that Golgi/TGN integrity was altered under these conditions. Note that the inhibition data shown in Figure 2B were normalized to take account of the overall decrease in the endogenous sulfation capacity (see Materials and Methods).

Figure 2.

Syn5 RNAi effect on cell entry by STxB. (A) Western blot analysis of target protein expression under variable RNAi conditions. Note that for Syn5, two different isoforms of the protein were detected. Sc = scrambled. (B) Sulfation was monitored over 20 min following addition of STxB-Sulf2 to HeLa cells that had been transfected for 72 hours with 200 nM scrambled siRNA or siRNAs targeting the indicated proteins. For Syn5, two independent siRNA sequences were used that gave similar results. For Syn16, sequence #3 was used. Data are expressed as percentages of STxB-Sulf2 sulfation for each experimental condition, using sulfation of STxB-Sulf2 on mock-transfected cells as the reference (set to 100%), and normalized for total sulfation counts (see (C)). RNAi against the late endosomal Syn7 was taken as a specificity control. Means ± s.e.m. of 3-5 determinations are shown. (C) Sulfation levels on endogenous proteins under the indicated experimental conditions. (D-F) Immunofluorescence analysis of retrograde STxB transport in mock-transfected control (CTL, (D)) or Syn5 RNAi cells (E-F). In all conditions, fluorophore-labeled STxB (green) was internalized for 45 min at 37°C. Cells were fixed and labeled for Syn5 (blue), the Golgi marker CTR433 (red), or TfR (red). Under Syn5 RNAi conditions, STxB accumulation in the Golgi was reduced, and the protein appeared in peripheral structures where it codistributed with the TfR. Note that Golgi membranes were partly dispersed in Syn5 RNAi cells (CTR433). Space bar = 10 μm.

Immunofluorescence was used to study compartment integrity and STxB accumulation sites under Syn5 RNAi conditions. In mock-transfected control cells, STxB (green) colocalized with Syn5 (blue) on CTR433 (red) positive Golgi membranes after 45 min of internalization into HeLa cells at 37°C (Fig. 2D). In Syn5 RNAi cells (Fig. 2E-F; low Syn5 signal, blue), STxB (green) accumulated in peripheral structures that were distinct from Golgi cisternae (Fig. 2E, red) and co-distributed with TfR (Fig. 2F, red; see inset). In these cells, we observed a variable degree of Golgi disruption (Fig. 2E, CTR433, red), as reported in another recent study (Suga et al., 2005), that probably reflects a complex role of Syn5 in membrane trafficking from and to the Golgi cisternae (Dascher et al., 1994; Hay et al., 1997; Tai et al., 2004). However, Syn5 RNAi did not appear to influence the presence of Gb3 molecules at the cell surface, as judged from Scatchard analysis that revealed equal numbers of STxB cell surface binding sites on mock-transfected control cells and Syn5 RNAi cells (Table 1).

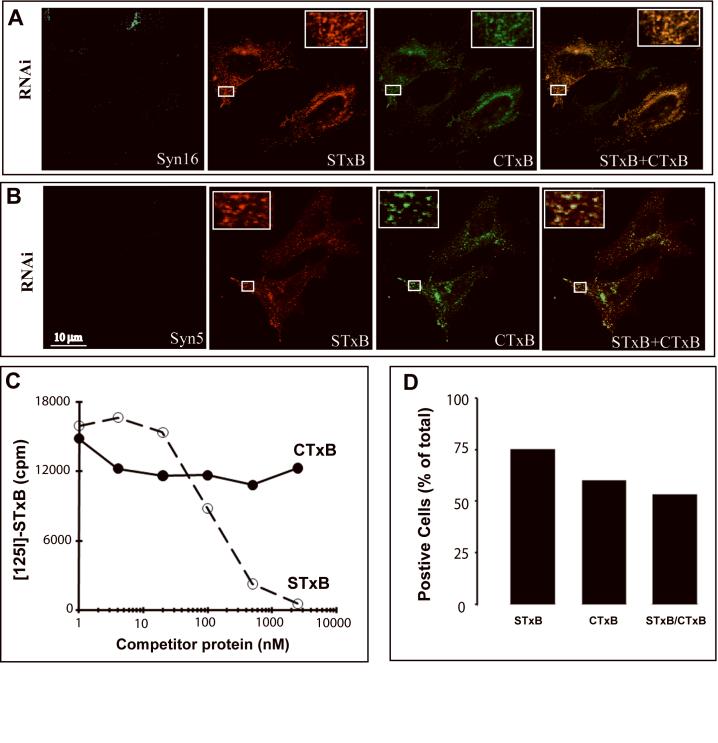

In the light of the endogenous sulfation phenotype (Fig. 2C) and the effect on Golgi morphology (Fig. 2E), we sought to have an independent confirmation of the inhibitory effect of Syn5 RNAi on retrograde STxB trafficking. For this, we used a previously developed N-glycosylation site-tagged STxB variant, which becomes modified by oligosaccharyl transferase upon arrival in the ER (Johannes et al., 1997; Mallard and Johannes, 2003). When compared to mock-transfected control cells, glycosylation was inhibited in Syn5, GS15, and Syn16 RNAi conditions (Fig. 3A), strongly suggesting that retrograde arrival in the ER was delayed in all cases. Strikingly, the level of inhibition was similar in all conditions (Fig. 3A), as seen for arrival in TGN/Golgi membranes (Fig. 2B). This suggested that of all possible retrograde transport steps, only EE/RE-to-TGN trafficking was inhibited, despite the effect on Golgi morphology that was specific for Syn5 RNAi cells. This prediction was tested directly, as shown below.

Figure 3.

Analysis of endocytosis and TGN/Golgi-to-ER transport in Syn5 RNAi cells. (A) Glycosylation analysis. Iodinated STxB-Glyc-KDEL was incubated with mock-transfected or RNAi-transfected HeLa cells for 4 hours. The percentage of glycosylated STxB-Glyc-KDEL was determined from gels, as described (Johannes et al., 1997; Mallard and Johannes, 2003). Glycosylation of STxB-Glyc-KDEL in mock-transfected cells was taken as the maximal possible (100%) value. Means ± s.e.m. of 2-3 experiments. (B-C) The endocytosis of STxB (B) and Tf (C) was determined on the same cells. The data represent the percentage of cell-surface inaccessible biotin-tagged STxB or Tf at each time point. Means ± s.e.m. of 4 experiments. (D-E) Quantitative analysis of TGN/Golgi-to-ER transport. (D) STxB-Sulf-Glyc-KDEL was internalized into mock-transfected (± tunicamycin) or siRNA-transfected HeLa cells for 2 hours in the presence of radioactive sulfate and then chased for 4 hours at 37°C. Cells were lysed, STxB-Sulf-Glyc-KDEL immunoprecipitated, and analyzed by SDS-PAGE. The uppermost band (n°1) corresponds to the glycosylation product which disappears upon tunicamycin treatment. See text for details. (E) Quantitative analysis by Phosphoimager of the mean of 2-3 experiments ± s.e.m., as shown in (D). The data express the percentages of sulfated STxB-Sulf-Glyc-KDEL that also become glycosylated in each experimental condition.

The first step of retrograde transport to the ER is endocytosis. We showed that neither the uptake of STxB (Fig. 3B) nor that of Tf (Fig. 3C) were affected in Syn5 RNAi cells. After leaving the endosome via the EE/RE-TGN interface, STxB is then transported from TGN/Golgi membranes to the ER. We used another variant of STxB, termed STxB-Sulf-Glyc-KDEL, to analyze this transport process. Treating HeLa cells with this protein in the presence of radioactive sulfate leads to its metabolic labeling in the TGN. Thereafter, glycosylation of the sulfated STxB-Sulf-Glyc-KDEL can be measured to signify arrival in the ER. Since glycosylation analysis is a relative measure — i.e. it determines the fraction of sulfated STxB-Sulf-Glyc-KDEL that is also glycosylated — it is independent of differences in sulfation efficiency between experimental conditions and can thus report on events at the TGN/Golgi-ER interface even if the preceding EE/RE-TGN interface is affected.

Under control conditions, i.e. after two hours incubation of STxB-Sulf-Glyc-KDEL with mock-transfected cells in the presence of radioactive sulfate (pulse) followed by a 4-hour chase, a complex banding pattern was observed by glycosylation analysis (Fig. 3D). The uppermost band (n°1) represents the glycosylation product, as judged from its electrophoretic mobility and the fact that it selectively disappeared upon tunicamycin treatment. The second band (n°2) corresponds to a TGN-sulfated but non-glycosylated STxB-Sulf-Glyc-KDEL. The third band (n°3) represents a proteolytic cleavage product of the TGN-sulfated STxB-SulfGlyc-KDEL still containing the glycosylation sequence. Indeed, this band became selectively intensified upon tunicamycin treatment. Bands 4-6 represent further proteolytic cleavage products on which the glycosylation sequence was removed. STxB-Sulf2 is shown on the right of Figure 3D for comparison. We observed that the banding pattern remained unchanged when Syn5 or GS15 expression was down-modulated by RNAi, even though all bands were weaker in Syn5 or GS15 RNAi conditions (Fig. 3D), reflecting the inhibition of EE/RE-to-TGN transport described above. Importantly, the quantitative analysis revealed that in all conditions, the same fraction of sulfated STxB-Sulf-Glyc-KDEL became glycosylated (Fig. 3E), strongly suggesting that ER entry following retrograde transport from TGN/Golgi membranes was not affected in all cases.

In summary, despite a profound effect on Golgi morphology, Syn5 RNAi only led to an inhibition of EE/RE-to-TGN transport of STxB, without affecting its internalization or trafficking from TGN/Golgi membranes to the ER.

A common fusion machinery in the retrograde route of several cargo proteins

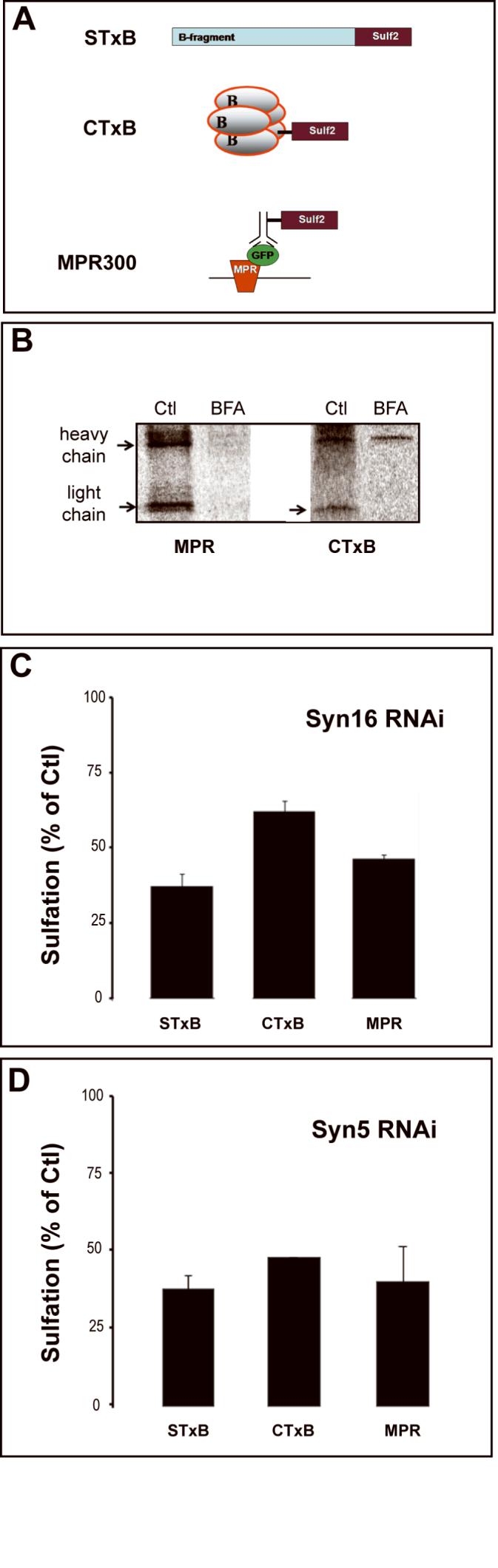

We then used the RNAi tools that we developed to address the question as to whether the same protein machinery is used for the efficient targeting of different exogenous and endogenous cargo proteins from endosomes to TGN/Golgi membranes. To address this question, we have extended the STxB-based sulfation assay to other cargo proteins, similar to what has been described for ricin (Rapak et al., 1997). Three types of sulfation site modifications were used (Fig. 4A). In the original configuration, a dimer of sulfation sites was genetically fused to STxB, yielding STxB-Sulf2 (Mallard et al., 1998). We have now developed a chemical coupling protocol of a sulfation site peptide coupling to CTxB or to an antibody directed against green fluorescent protein (GFP) (reviewed in (Amessou et al., in press)). In the latter case, sulfation analysis is performed on HeLa cells that stably express MPR300 fused to luminal oriented GFP (Waguri et al., 2003). The anti-GFP is taken up in association with GFP-MPR and undergoes retrograde transport from the plasma membrane to the TGN.

Figure 4.

Retrograde transport of different cargo proteins in Syn5 and Syn16 RNAi cells. (A) Constructs used for sulfation analysis. A genetic fusion of STxB with tandem sulfation sites was made as described (Mallard et al., 1998). For CTxB, a tandem sulfation site peptide was chemically coupled to primary amines. In the case of MPR, the tandem sulfation site peptide was chemically coupled to an anti-GFP antibody recognizing MPR-GFP protein in stably transfected HeLa cells (Waguri et al., 2003). (B) Sulfation analysis of sulfation site peptide-coupled CTxB and MPR. HeLa cells were incubated for 40 min with the indicated proteins in the presence of radioactive sulfate with or without BFA, followed by immunoprecipitation and autoradiography. For CTxB, the arrow indicates sulfated toxin B-subunit, while the upper bands that are visible with or without BFA, originate from contaminating endogenous sulfoproteins at the level of the load. (C-D) STxB-Sulf2, CTxB-Sulf2, and sulfation-site coupled anti-GFP-MPR antibody were incubated for 40 min in the presence of radioactive sulfate with HeLa cells that had been transfected with (C) Syn16 siRNA #3 or (D) Syn5 siRNA #1. Sulfated proteins were immunoprecipitated and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. Sulfation signals are expressed as normalized percentages of sulfation observed in mock-transfected control cells.

Mass spectroscopy analysis permitted estimation of the CTxB modification to approximately 2 sulfation peptides per CTxB pentamer (not shown). Because of its size, this analysis was not performed on anti-GFP antibody. Sulfation analysis revealed that CTxB and MPR constructs were indeed sulfated in HeLa cells (Fig. 4B). Due to the reduced labeling efficiency of CTxB-Sulf2 and the sulfation site peptide modified anti-GFP-MPR antibody, retrograde transport was sampled for 40 min, and not for 20 min, as above. This sulfation was inhibited by brefeldin A (BFA) (Fig. 4B), confirming that it depended on retrograde transport (Mallard et al., 1998). These experiments, like those reported below were performed on a HeLa cell clone in which the STxB receptor Gb3 is uniformly expressed throughout the cell population and which has high levels of the CTxB receptor GM1.

In experiments in which the different markers were tested in a pair-wise manner on the same cells, it was found that retrograde transport to the TGN of CTxB and MPR was inhibited to a similar extent to that of STxB in Syn16 (Fig. 4C) or Syn5 (Fig. 4D) RNAi cells. These data reveal that these different exogenous and endogenous cargo proteins share a Syn5 and Syn16-based machinery for efficient retrograde transport.

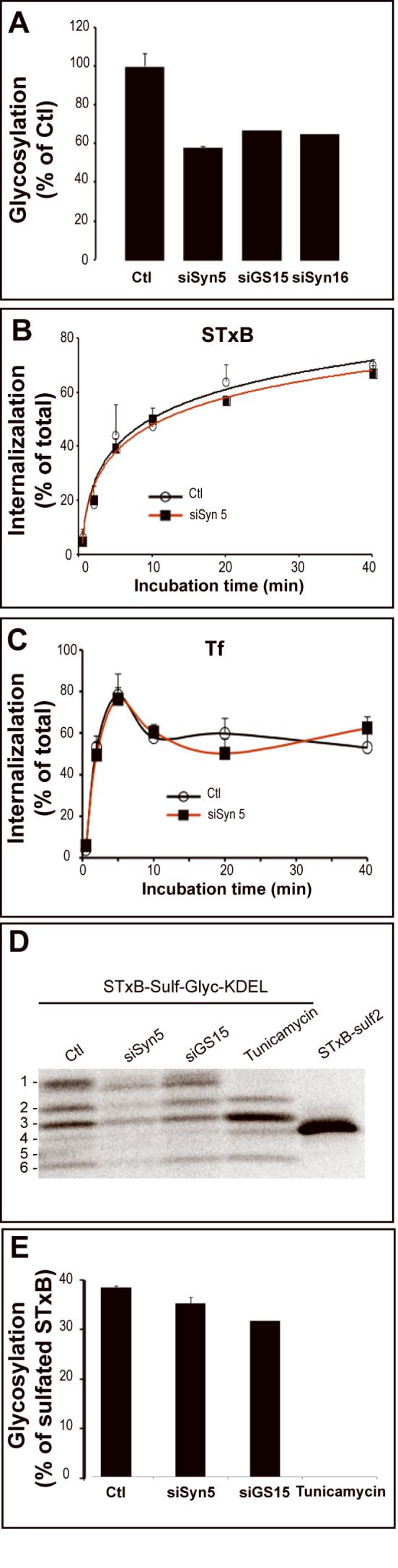

Immunofluorescence analysis showed that in Syn16 (Fig. 5A) or Syn5 (Fig. 5B) RNAi cells, STxB (red) and CTxB (green) both were blocked in perfect overlap in peripheral endosomes. These observations further support the contention that STxB and CTxB use the same route to traffic between endosomes and the TGN. Their binding to cells appears to be independent, though, as it could be shown that CTxB does not compete with radiolabeled STxB for binding to cells (Fig. 5C). As a control, the efficient competition of unlabeled STxB was demonstrated. Furthermore, the quantification of STxB and CTxB positive cells in our HeLa culture system revealed that Gb3 and GM1 expression appear to be largely independent (Fig. 5D).

Figure 5.

Co-distribution analysis of STxB and CTxB. (A-B) Immunofluorescence analysis of STxB (red) and CTxB (green) distribution in (A) Syn16 or (B) Syn5 RNAi cells after internalization for 45 min at 37°C. (C) Competition analysis. Iodinated STxB was incubated with HeLa cells in the presence of increasing concentrations of non-labeled CTxB or STxB. The amount of cell-associated radioactivity was determined in each condition. Note that CTxB did not displace the iodinated STxB from its receptor. (D) Binding analysis. HeLa cells were incubated on ice with 1 μM Alexa Fluor-488-labeled CTxB and 1 μM Cy3-labeled STxB. The cells were washed, fixed, and numbers of cells positive for one or the other marker were counted. Double-positive cells are roughly present at numbers as expected if GM1 and Gb3 expression are independent events.

Intoxication analysis under Syn5 and Syn16 RNAi conditions

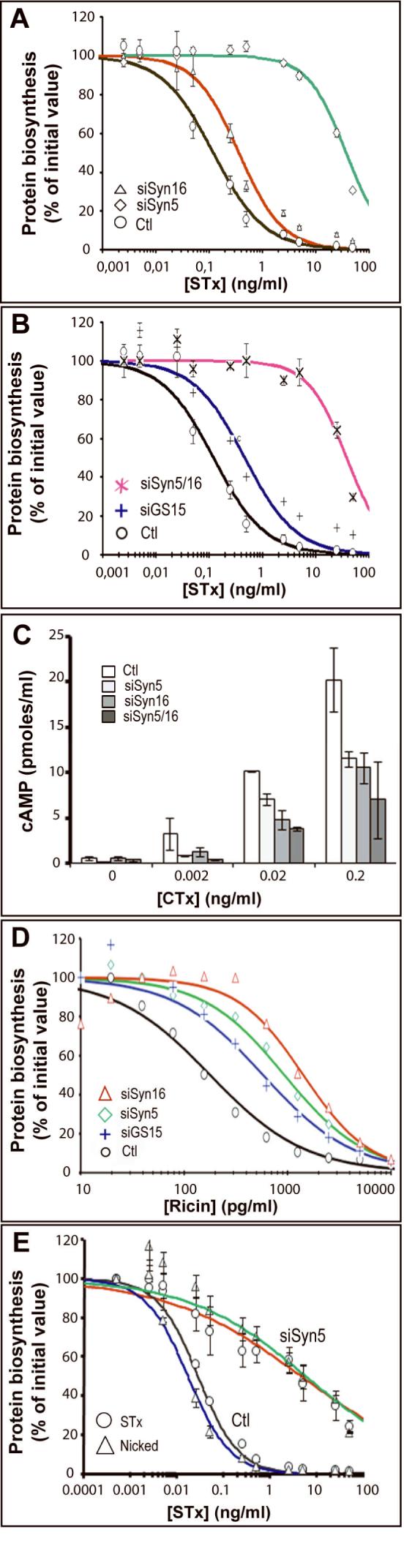

In the next experimental series, we analyzed how intoxication of cells with STx, CTx, and ricin was affected by the presence of reduced levels of Syn5 or Syn16. Under conditions of Syn16 down-modulation, HeLa cells were partly protected against intoxication by STx (Fig. 6A). In these experiments, the effect on protein synthesis of adding increasing concentrations of STx to cells was measured. It was observed that in Syn16 RNAi cells, higher doses of STx were needed to obtain the same level of protein synthesis inhibition as in mock-transfected control cells. Indeed, the IC50 was shifted from 0.12 ng/ml in mock-transfected cells to 0.37 ng/ml in Syn16 RNAi cells (3.1-fold protection). These data clearly indicate that efficient retrograde transport is required for efficient toxin arrival in the cytosol. The specificity of the effect was documented by the finding that diphtheria toxin, which translocates the membrane of early endosomes (Lemichez et al., 1997) and does not depend on the retrograde pathway to intoxicate cells (Yoshida et al., 1991), could intoxicate cells efficiently under Syn16 RNAi conditions (not shown).

Figure 6.

Syn5 and Syn16 RNAi effects on cell intoxication by STx, CTx, and ricin. (A) Mock-transfected control cells or HeLa cells transfected with the indicated siRNAs were treated for 1 hour at 37°C with the indicated doses of STx. Protein biosynthesis was then determined by measuring the incorporation of radiolabeled methionine into acid-precipitable material. Data are presented as percentages of proteins biosynthesis in the indicated conditions, when compared to non-toxin treated cells. (B) Cells were treated for 1 hour with the indicated doses of STx and analyzed as described in (A). (C) Mock-transfected or RNAi-transfetced cells were treated with increasing doses of CTx, and cAMP production was measured to detect CTx arrival in the cytosol. (D) Mock-transfected or RNAi-transfetced cells were treated for 1 hour with the indicated doses of ricin, and analyzed as described in (A). (E) Intoxication of HeLa cells by unnicked (STx) or pre-nicked STx (Nicked) in control mock-transfected control cells or Syn5 RNAi cells (siSyn5). Pre-nicking did not alter the Syn5 RNAi-mediated protection of cells against the toxin. (A-E) Means of 2-4 experiments.

Unexpectedly, we observed that Syn5 RNAi protected cells more against STx than did Syn16 RNAi (Fig. 6A), shifting the IC50 to 37.6 ng/ml for Syn5 RNAi cells (313-fold protection). This effect was specific for Syn5, since reducing the levels of GS15 resulted in an IC50 of 0.53 ng/ml (Fig. 6B; 4.4-fold protection), analogous to the outcome of lowering endogenous Syn16. When used in combination, the effect of Syn5+Syn16 RNAi (IC50 of 38.4 ng/ml, 320-fold protection; Fig. 6B) was no different to that of Syn5 RNAi alone. These observations showed that despite their similar effects on retrograde transport to TGN/Golgi membranes, as measured by the analysis of sulfation (Fig. 2B) and glycosylation (Fig. 3A), reduced levels of Syn5 and Syn16 had very different effects on cell intoxication by STx.

To further characterize the effect of Syn5 and Syn16 RNAi on the action of toxins routed via the TGN/Golgi and ER, we tested both CTx and ricin. The A1 subunit of CTx acts as an ADP-ribosyltransferase and catalyzes the transfer of an ADP-ribose to the alpha-chain of the regulatory protein Gs (De Haan and Hirst, 2004). This stabilizes the GTP bound form of Gαs, lowering its GTPase activity and thereby creating a constitutive signal for the activation of adenylyl cyclase, leading to an elevation of cellular cAMP levels. We found here that the capacity of CTx to increase cellular cAMP was reduced in Syn5 and Syn16 RNAi conditions (Fig. 6C), consistent with the need for a step mediated by these syntaxins to gain cytosolic entry. The combined use of Syn5+Syn16 RNAi had only a slight additive effect.

Ricin is another toxin known to follow the retrograde route to ER (Sandvig and van Deurs, 1999). Like STx, ricin is a ribosome inactivating protein catalyzing the same depurination of 28S rRNA (Endo et al., 1987; Endo et al., 1988). The IC50 was shifted from 0.2 ng/ml in control cells to 1.5 ng/ml in Syn16 RNAi cells (Fig. 6D), resulting in a 7.5-fold protection against the toxin. The consequence of Syn5 and GS15 knock down were very similar and close to that observed with Syn16. Indeed, the protection against this toxin was 4.5-fold and 3-fold with Syn5 and GS15 RNAi, respectively (Fig. 7D). We therefore conclude that Syn5 and Syn16 RNAi inhibited the action of all three toxins by interfering with their productive trafficking to the ER. Surprisingly, the protective effect was particularly striking in the combination of Syn5 RNAi and STx.

One possible explanation for this difference would be the displacement under Syn5 RNAi conditions of a factor specifically required for the processing of the A-subunit of STx to A1 and A2 fragments, thus explaining the selective effect on only this toxin. To test this hypothesis, inhibition of protein biosynthesis in mock-transfected and Syn5 RNAi treated cells was compared for untreated STx and a pre-nicked version thereof (Fig. 6E). However, because no difference between the toxin preparations could be detected, we exclude this possibility.

Discussion

The list of proteins and lipids that escape the endocytic pathway for targeting to TGN/Golgi membranes is increasing, but it is currently unclear how many pathways exist to link the endocytic and the biosynthetic/secretory routes and whether different cargo proteins all use the same molecular machinery for trafficking across the endosomes-TGN/Golgi interface. In this study, we have adopted the sulfation test methodology (Johannes et al., 1997; Mallard and Johannes, 2003) to study retrograde transport of several exogenous and endogenous proteins. We observed that down-modulating the expression of Syn16 and Syn5 inhibited retrograde transport and productive intoxication by three protein toxins, STx, CTx, and ricin, and the retrograde transport of MPR. The protective effect against STx action was much stronger with Syn5 RNAi than with RNAi against Syn16 or the Syn5 SNARE complex partner GS15, and the Syn5 RNAi effect was more pronounced against STx than on cells challenged with CTx or ricin. This points to an as yet unidentified, STx-specific function of this SNARE in steps downstream of initial delivery to the ER lumen.

Cargo proteins in the retrograde route

Based on the experiments described in this study, we conclude that several exogenous and endogenous cargo proteins share with STxB elements of the retrograde transport machinery for their efficient trafficking between endosomes and the TGN/Golgi. Very few studies have until now been designed to address this question directly. To a large extent, this was due to the fact that molecular inhibitors of the retrograde route and quantitative tools for its analysis have only become available relatively recently. The first quantitative tools to assess membrane traffic between endosomes and TGN/Golgi membranes were based on one endogenous protein, MPR (Goda and Pfeffer, 1988), and on exogenous STxB and ricin (Johannes et al., 1997; Rapak et al., 1997). It is therefore not surprising that most of the available comparative data were obtained with these proteins.

MPR trafficking studies allowed identification of Rab9 (Lombardi et al., 1993) and TIP47 (Diaz and Pfeffer, 1998) as molecular players at the interface between late endosomes and the TGN. More recently, it was found that MPR can also use the Syn16/Rab6a' regulated EE/RE-to-TGN pathway (Saint-Pol et al., 2004). Other studies showed that the capacity of the ER-routed Pseudomonas exotoxin A to intoxicate cells was sensitive to Rab9 RNAi (Smith et al., 2006b), while Rab9 did not appear to function in the cell entry of ricin (Iversen et al., 2001; Simpson et al., 1995). The exact interplay between the pathways of Syn16/Rab6a' and the TIP47/Rab9 still remains to be established.

A comparison of ricin and STxB reveals both differences and similarities in their trafficking between endosomes and TGN/Golgi membranes. The most notable difference was the observation that clathrin was required for retrograde transport of STxB (Lauvrak et al., 2004; Saint-Pol et al., 2004), but not for that of ricin (Iversen et al., 2001). Similarly, changes in calcium homeostasis affected ricin, but not STx (Lauvrak et al., 2002). However, for both toxins, interfering with the integrity of membrane domains of the raft type prevented retrograde transport (Falguières et al., 2001; Grimmer et al., 2000). It was also found that for both ricin and STx, overexpression of wild-type Rab11 or expression of a dominant negative Rab11 mutant moderately inhibited retrograde transport (Iversen et al., 2001; Wilcke et al., 2000). Taken together with our results that show partial protection of cells against ricin and STx intoxication under conditions of Syn5 and Syn16 knock down, it might be suggested that both toxins share a common mechanism for targeting to TGN/Golgi membranes. However, clathrin-dependent or not, they may rely on different retrograde sorting machinery on EE/RE.

For CTxB, quantitative biochemical tools to study retrograde transport have only recently become available ((Fujinaga et al., 2003) and this study). Before this, it was noted that CTxB and STxB have very similar structures, but their binding to their glycosphingolipid receptors – GM1 for CTxB and Gb3 for STxB – appears to follow different rules. Indeed, while for STxB, the affinity for one globotriose carbohydrate molecule is extremely weak (Kd values in the mM range), CTxB has μM affinity for its carbohydrate receptor in solution (see (Pina and Johannes, 2005) for a review). Cell surface binding studies have shown that stimulating the uptake of one toxin receptor, i.e. GM1 or Gb3, does not affect the presence at the cell surface of the reciprocal receptor (Schapiro et al., 1998). Despite this, both toxins share the characteristic of interacting with membrane microdomains of the raft type (Falguières et al., 2001; Katagiri et al., 1999; Kovbasnjuk et al., 2001), and fluorescence resonance energy transfer studies have indicated that both toxins can be very close together after binding to the plasma membrane (Kovbasnjuk et al., 2001). Once inside the cell, whether by clathrin-dependent or -independent endocytosis (Kirkham et al., 2005; Lauvrak et al., 2004; Saint-Pol et al., 2004; Sandvig et al., 1989), CTxB and STxB both depend on golgin-97 (Lu et al., 2004) and Syn5 and/or Syn16 (this study) functions to reach TGN/Golgi membranes.

Later steps of retrograde transport

Considering the established involvement of the Syn5 SNARE in membrane exchange between the ER and Golgi apparatus (Dascher et al., 1994; Hay et al., 1997), the description of Syn5 function at the EE/RE-TGN interface (Tai et al., 2004) came as a surprise. One possibility was that Syn5 may function in retrograde transport at several levels of the retrograde route, e.g. at the EE/RE-TGN interface and at the Golgi-ER interface. However, the observations reported in our current study clearly demonstrate that once STxB has reached TGN/Golgi membranes, Syn5 RNAi does not have an effect on further retrograde transport to the ER. This suggests that within the retrograde pathway, Syn5 function is restricted to the EE/RE-TGN interface.

Surprisingly however, although Syn5 RNAi had no effect on toxin trafficking beyond the EE/RE-to-TGN step, it significantly protected cells against STx action, considerably more (∼100 fold) than against ricin or CTx. STx and ricin have the same catalytic mechanism (Endo et al., 1987; Endo et al., 1988), and our studies show that STxB transport to the ER is not inhibited more in Syn5 RNAi cells than in Syn16 or GS15 RNAi transfected cells. Therefore, the STx-specific effect of Syn5 RNAi most likely resides at the level of the ER. Whether this effect is direct, such as a role of Syn5 in retrotranslocation or in the distribution of Shiga toxin receptors within ER microdomains (Smith et al., 2006a), or indirect, such as a requirement for ER-Golgi cycling prior to retrotranslocation, remains to be determined in later studies.

In conclusion, we have shown that several exogenous and endogenous cargo proteins share the same protein machinery for efficient retrograde transport at the EE/RE-TGN interface, which suggests the existence of limited molecular redundancy for targeting the TGN/Golgi from endosomes.

Materials and Methods

Materials, recombinant proteins and antibodies

Monoclonal antibody anti-CTR433 was from M. Bornens (Institut Curie, Paris, France), and polyclonal antibodies against Syn16 and Syn5 were from W. Hong (IMCB, Singapore). Monoclonal antibodies against TfR (Sigma), GFP (Roche), clathrin heavy chain, γ-adaptin, GS15 (BD Biosciences), polyclonal antibodies against Syn7 (Synaptic Systems), and FITC-, Cy3- and Cy5-coupled secondary antibodies (Jackson Immuno-research) were purchased from the indicated suppliers. STxB-FITC, CTxB-Cy3 and STxB-Sulf2, and monoclonal anti-STxB antibody 13C4 were prepared as previously described (Johannes et al., 1997; Mallard et al., 1998).

Cells

HeLa cells were cultured as described (Johannes et al., 1997). Hela cells stably transfected with GFP-MPR300 were from B. Hoflack (Universität Dresden, Germany) and were grown in the presence of 0.5 mg/ml of Geneticin (G418).

RNA interference

Three Synthetic siRNA duplex (21-mers) targeting human syntaxin 16 (first: ACAGCUUCACAAGGCAGAA; second: GGACCUUUGAUACUGCUGC; third: GCAGCGAUUGGUGUGACAA), two 21-mers targeting human syntaxin 5 (first: AAGTGAGGACAGAGAACCTGA; second: AAAGGAAGCGTTGGCAGCAAA), two siRNA targeting syntaxin 7 (first: ACTTCCAGAAGGTCCAGAGTT; second: GTTTTGGGCCACATTGCATT), and one scrambled siRNA (GACAAGAACCAGAACGCCATT) were designed and purchased from a commercial supplier (MWG-Biotech, Germany). Cells were transfected using oligofectAMINE (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Experiments were carried out 3 days after transfection. Except for the experiments described in Figure 1, concentrations of 200 nM of siRNA were used for transfection in the remainder of the manuscript.

Imunofluorescence analysis

Immunofluorescence analysis was performed as previously described (Mallard et al., 1998). Briefly, cells were incubated with 1 μM STxB-FITC, STxB-Cy3, or CTxB-Cy3 for 30 min at 4°C, shifted to 37°C for 45 min, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, and permeabilized with saponin. After labeling with the indicated antibodies, coverslips were mounted and analyzed by confocal microscopy (Leica Microsystems, Mannheim, Germany).

Chemical coupling

For the coupling of sulfation site peptide to CTxB or anti-GFP antibody, the following procedure was performed as described (Amessou et al., in press). Breifly, CTxB or anti-GFP antibody (50 to 100 μM in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.5) was incubated at room temperature for 30 min with 0.8-1.5 mM SATA reagent (N-Succinimidyl-S-acetylthioacetate; Pierce). Activated molecules were then incubated for 2 hours at room temperature with bromo-acetylated sulfation site peptide (Neosystem, Strasbourg, France) in presence of 500 mM hydroxylamine. The coupling reaction was then stopped by dialysis against PBS buffer.

Sulfation analysis

Sulfation analysis was performed as described before (Mallard et al., 1998). When two cargo proteins were analyzed, the following modifications were used. 1 μM of STxB-Sulf2 were simultaneously incubated with HeLa cells in the presence of 1 μM of CTxB-Sulf2 or 15 μg/ml of anti-GFP-Sulf2 antibody. After uptake in the presence of 0.4 mCi/ml radioactive sulfate (Amersham), the cells were lysed in PBS, 1% Triton X-100, and Protease Inhibitor Cocktail, and centrifuged for 10 min at 3000 rpm to remove the nuclei. 10% of the supernatant was immunprecipitated with monoclonal antibody anti-STxB antibody (13C4), while 90% of the supernatant was precipitated with either streptavidine-agarose (CTxB-Sulf2) or with protein G-Sepharose (anti-GFP-Sulf2 antibody). Sulfated cargos were analyzed by SDS-PAGE autoradiography. In parallel, the sulfation of endogenous proteins and proteoglycans was determined by TCA-precipitation from immunopreciptation supernatants and used to normalize data obtained when studying toxin sulfation in various conditions. Total sulfation counts are usually similar in all conditions, except for Syn5 RNAi (see Figure 2C).

Glycosylation analysis

Glycosylation analysis and tunicamycin treatment were performed as previously described (Johannes et al., 1997; Mallard et al., 1998).

Cytotoxicity assays

STx, DTx, and ricin cytotoxicities were measured by the ability of cells to incorporate [35S]-methionine into acid-precipitable material following toxin treatment. HeLa cells were seeded at 1.5 × 104 cells/well into flat-bottomed 96-well plates, and grown overnight. Cells were then overlaid with medium containing appropriate concentrations of toxin for 60 min. Remaining cellular protein synthesis following toxin treatment was determined from the incorporation of a 60 min pulse of 1 μCi [35S]-methionine/well into total protein. Plates were then washed three times with ice-cold 5% TCA to precipitate proteins. After 2 more washes in PBS, radioactivity was counted in Wallac Optiphase Supermix. For measuring CTx induced cAMP production, cells were detached with 2 mM EDTA in PBS and incubated with indicated concentrations of CTx for 2 hours at 37°C. After lysis in 0.1 M HCl, intracellular cAMP levels were assayed with Direct cAMP Enzyme Immunoassay kit (Sigma).

STxB and Tf internalization assays

STxB-K3 (STxB variant with three C-terminal lysines) and human diferric transferrin were biotinylated using NHS-SS-Biotin following manufacturer's instructions (Pierce). Endocytosis was measured as described recently (Amessou et al., in press). Briefly, serum-starved cells were detached from plates with 2 mM EDTA in PBS and incubated in the presence of 1 μM biotin-STxB and 200 nM biotin-Tf for 30 min on ice. After washing, cells were incubated at 37°C for the indicated times (1.5 × 105 cells per data point). The remaining biotin on cell surface-exposed STxB or transferrin was cleaved by subsequent treatment with 100 mM of the non-membrane permeable reducing agent sodium 2-mercaptoethanesulfonic acid (MESNA) on ice for 20 min. After washing, excess MESNA was quenched with 100 mM iodoacetamide for 20 min. Cells were lysed in blocking buffer (10 mM Tris [pH 7.4], 1 mM EDTA, 50 mM NaCl, 0.2% BSA, 0.1% SDS, and 1% Triton X-100) before loading on ELISA plates coated either with anti-Tf or anti-STxB antibody (13C4). Biotinylated STxB or transferrin was detected using streptavidin-HRP (Roche). The reaction was stopped with 3M sulphuric acid and plate was read at 490 nm. The percentage of internal STxB (or Tf) was determined as the ratio of signal after MESNA reduction (internal ligand) to signal without reduction (total ligand).

EGF degradation and Tf recycling assays

The assays were performed as described previously (Mallard et al., 1998; Saint-Pol et al., 2004). Briefly, Hela cells were serum starved and incubated for 30 min on ice with iodinated EGF (750 Ci/mmol; Amersham Life Sciences). Cells were washed, shifted to 37°C for the indicated times, and put back on ice. TCA-soluble counts from cells and culture medium were expressed as percentage of total cell-associated radioactivity.

VSVG-GFP anterograde transport assay

Cells were transfected with ts045-VSVG-GFPct plasmid DNA (Scales et al., 1997). Transfection was carried out with Calcium Phosphate Transfection Kit (Invitrogen) using 5 μg of plasmid per transfection. After transfection, the cells were incubated at 40°C for 20 hours. The cells were detached from plates with 20 mM EDTA in PBS, washed in PBS++ (PBS containing 0.1mM CaCl2 and 0.1 mM MgCl2, pH 7.4) and pre-incubated or not with 5 μg/ml BFA at 40°C. Cells were then incubated for 2 hours at 32°C or put on ice. Surface proteins were biotinylated with 2.5 mg/ml NHS-SS-biotin in PBS containing Ca2+ and Mg2+ for 10 min on ice. The reaction was quenched with 50 mM NH4Cl for 10 min on ice, the cells were lysed in buffer containing 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% SDS, 0.2% BSA, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 10 mM Tris pH 7.4. Cell lysates were divided in two, transferred to 96-wells ELISA plates coated with anti-VSVG antibody, and revealed by ELISA for anti-HRP-streptavidin (cell surface VSVG) or anti-GFP antibody (total VSVG protein). The latter was used for normalization.

Acknowledgements

We thank Wanjin Hong, Michel Bornens, Bernard Hoflack, and Philippe Benaroch for reagents, Wolfgang Faigle and Lucien Cabanié for technical help, and Robert Spooner and Katherine Moore for nicked and wild-type Shiga toxin. This work was supported by grants from the Ligue Nationale contre le Cancer, Association de Recherche contre le Cancer (n°5177 and 3105), Fondation de France, and Action Concertée Incitative – Jeunes chercheurs (n°5233) to CL and LJ, by a Wellcome Trust progamme gant (080566/Z/06/Z) to LMR and JML, and by fellowships from Ligue Nationale contre le Cancer and Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale to T.F. and Fondation de France for M.A.

Abbreviations

- BFA

brefeldin A

- CTx

cholera toxin

- CTxB

cholera toxin B-subunit

- EE

early endosome

- EGF

epidermal growth factor

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- MPR

mannose 6-phosphate receptor

- RE

recycling endosome

- RNAi

RNA interference

- TGN

trans-Golgi network

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

- SNARE

soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive fusion protein attachment protein receptor

- STx

Shiga toxin

- STxB

Shiga toxin B-subunit

- Tf

transferrin

- TfR

transferrin receptor

- VSVG

vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein

References

- Amessou M, Popoff V, Yelamos B, Saint-Pol A, Johannes L. Recent methods for studying retrograde transport. Curr. Protocols Cell. Biol. doi: 10.1002/0471143030.cb1510s32. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett MK, Garcia-Arraras JE, Elferink LA, Peterson K, Fleming AM, Hazuka CD, Scheller RH. The syntaxin family of vesicular transport receptors. Cell. 1993;74:863–873. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90466-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bock JB, Lin RC, Scheller RH. A new syntaxin family member implicated in targeting of intracellular transport vesicles. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:17961–17965. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.30.17961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YA, Scheller RH. SNARE-mediated membrane fusion. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2001;2:98–106. doi: 10.1038/35052017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dascher C, Matteson J, Balch WE. Syntaxin 5 regulates endoplasmic reticulum to Golgi transport. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:29363–29366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Haan L, Hirst TR. Cholera toxin: a paradigm for multi-functional engagement of cellular mechanisms. Mol. Membr. Biol. 2004;21:77–92. doi: 10.1080/09687680410001663267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz E, Pfeffer SR. TIP47: a cargo selection device for mannose 6-phosphate receptor trafficking. Cell. 1998;93:433–443. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81171-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo Y, Mitsui K, Motizuki M, Tsurugi K. The mechanism of action of ricin and related toxic lectins on eukaryotic ribosomes. The site and the characteristics of the modification in 28 S ribosomal RNA caused by the toxins. J. Biol. Chem. 1987;262:5908–5912. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo Y, Tsurugi K, Yutsudo T, Takeda Y, Ogasawara T, Igarashi K. Site of action of a Vero toxin (VT2) from Escherichia coli O157:H7 and of Shiga toxin on eukaryotic ribosomes. RNA N-glycosidase activity of the toxins. Eur. J. Biochem. 1988;171:45–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1988.tb13756.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falguières T, Mallard F, Baron CL, Hanau D, Lingwood C, Goud B, Salamero J, Johannes L. Targeting of Shiga toxin B-subunit to retrograde transport route in association with detergent resistant membranes. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2001;12:2453–2468. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.8.2453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujinaga Y, Wolf AA, Rodighiero C, Wheeler H, Tsai B, Allen L, Jobling MG, Rapoport T, Holmes RK, Lencer WI. Gangliosides that associate with lipid rafts mediate transport of cholera and related toxins from the plasma membrane to the endoplasmic reticulum. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2003;14:4783–4793. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-06-0354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goda Y, Pfeffer SR. Selective recycling of the mannose 6-phosphate/IGF-II receptor to the trans Golgi network in vitro. Cell. 1988;55:309–320. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90054-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimmer S, Iversen TG, van Deurs B, Sandvig K. Endosome to golgi transport of ricin is regulated by cholesterol. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2000;11:4205–4216. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.12.4205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay JC, Chao DS, Kuo CS, Scheller RH. Protein interactions regulating vesicle transport between the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi apparatus in mammalian cells. Cell. 1997;89:149–158. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80191-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay JC, Klumperman J, Oorschot V, Steegmaier M, Kuo CS, Scheller RH. Localization, dynamics, and protein interactions reveal distinct roles for ER and Golgi SNAREs. J. Cell Biol. 1998;141:1489–1502. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.7.1489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iversen TG, Skretting G, Llorente A, Nicoziani P, van Deurs B, Sandvig K. Endosome to golgi transport of ricin is independent of clathrin and of the Rab9 and Rab11 GTPases. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2001;12:2099–2107. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.7.2099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahn R, Grubmuller H. Membrane fusion. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2002;14:488–495. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(02)00356-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johannes L, Decaudin D. Protein toxins: intracellular trafficking for targeted therapy. Gene Ther. 2005;16:1360–1368. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johannes L, Tenza D, Antony C, Goud B. Retrograde transport of KDEL-bearing B-fragment of Shiga toxin. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:19554–19561. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.31.19554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katagiri YU, Mori T, Nakajima H, Katagiri C, Taguchi T, Takeda T, Kiyokawa N, Fujimoto J. Activation of src family kinase yes induced by shiga toxin binding to globotriaosyl ceramide (Gb3/CD77) in low density, detergent-insoluble microdomains. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:35278–35282. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.49.35278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkham M, Fujita A, Chadda R, Nixon SJ, Kurzchalia TV, Sharma DK, Pagano RE, Hancock JF, Mayor S, Parton RG. Ultrastructural identification of uncoated caveolin-independent early endocytic vehicles. J. Cell Biol. 2005;168:465–476. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200407078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovbasnjuk O, Edidin M, Donowitz M. Role of lipid rafts in Shiga toxin 1 interaction with the apical surface of Caco-2 cells. J. Cell Sci. 2001;114:4025–4031. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.22.4025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauvrak SU, Llorente A, Iversen TG, Sandvig K. Selective regulation of the Rab9-independent transport of ricin to the Golgi apparatus by calcium. J. Cell Sci. 2002;115:3449–3456. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.17.3449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauvrak SU, Torgersen ML, Sandvig K. Efficient endosome-to-Golgi transport of Shiga toxin is dependent on dynamin and clathrin. J. Cell Sci. 2004;117:2321–2331. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemichez E, Bomsel M, Devilliers G, vanderSpek J, Murphy JR, Lukianov EV, Olsnes S, Boquet P. Membrane translocation of diphtheria toxin fragment A exploits early to late endosome trafficking machinery. Mol. Microbiol. 1997;23:445–457. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1997.tb02669.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin SX, Gundersen GG, Maxfield FR. Export from pericentriolar endocytic recycling compartment to cell surface depends on stable, detyrosinated (glu) microtubules and kinesin. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2002;13:96–109. doi: 10.1091/mbc.01-05-0224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lingwood CA. Verotoxins and their glycolipid receptors. Adv. Lipid Res. 1993;25:189–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombardi D, Soldati T, Riederer MA, Goda Y, Zerial M, Pfeffer SR. Rab9 functions in transport between late endosomes and the trans Golgi network. Embo J. 1993;12:677–682. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05701.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord JM, Deeks E, Marsden CJ, Moore K, Pateman C, Smith DC, Spooner RA, Watson P, Roberts LM. Retrograde transport of toxins across the endoplasmic reticulum membrane. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2003;31:1260–1262. doi: 10.1042/bst0311260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu L, Tai G, Hong W. Autoantigen Golgin-97, an effector of Arl1 GTPase, participates in traffic from the endosome to the trans-golgi network. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2004;15:4426–4443. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-12-0872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallard F, Johannes L. Shiga toxin B-subunit as a tool to study retrograde transport. In: Philpott D, Ebel F, editors. Methods Mol. Med. Shiga Toxin Methods and Protocols. Vol. 73. 2003. pp. 209–220. Chapter 17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallard F, Tang BL, Galli T, Tenza D, Saint-Pol A, Yue X, Antony C, Hong WJ, Goud B, Johannes L. Early/recycling endosomes-to-TGN transport involves two SNARE complexes and a Rab6 isoform. J. Cell Biol. 2002;156:653–664. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200110081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallard F, Tenza D, Antony C, Salamero J, Goud B, Johannes L. Direct pathway from early/recycling endosomes to the Golgi apparatus revealed through the study of Shiga toxin B-fragment transport. J. Cell Biol. 1998;143:973–990. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.4.973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natarajan R, Linstedt AD. A cycling cis-Golgi protein mediates endosome-to-Golgi traffic. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2004;15:4798–4806. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-05-0366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peacock E, Jacob VW, Fallone SM. Escherichia coli O157:H7: etiology, clinical features, complications, and treatment. Nephrol. Nurs. J. 2001;28:547–50. 553–5; quiz 556–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelham HRB, Rothman JE. The debate about transport in the Golgi - Two sides of the same coin? Cell. 2000;102:713–719. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00060-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pina DG, Johannes L. Cholera and Shiga toxin B-subunits: thermodynamic and structural considerations for function and biomedical applications. Toxicon. 2005;45:389–393. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2004.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapak A, Falnes PO, Olsnes S. Retrograde transport of mutant ricin to the endoplasmic reticulum with subsequent translocation to cytosol. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:3783–3788. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.3783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saint-Pol A, Yélamos B, Amessou M, Mills I, Dugast M, Tenza D, Schu P, Antony C, McMahon HT, Lamaze C, et al. Clathrin adaptor epsinR is required for retrograde sorting on early endosomal membranes. Dev. Cell. 2004;6:525–538. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(04)00100-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandvig K, Garred O, Prydz K, Kozlov JV, Hansen SH, van Deurs B. Retrograde transport of endocytosed Shiga toxin to the endoplasmic reticulum. Nature. 1992;358:510–512. doi: 10.1038/358510a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandvig K, Olsnes S, Brown J, Petersen OW, van Deurs B. Endocytosis from coated pits of Shiga toxin: a glycolipid-binding protein from Shigella dysenteriae 1. J. Cell Biol. 1989;108:1331–1343. doi: 10.1083/jcb.108.4.1331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandvig K, Spilsberg B, Lauvrak SU, Torgersen ML, Iversen TG, van Deurs B. Pathways followed by protein toxins into cells. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2004;293:483–490. doi: 10.1078/1438-4221-00294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandvig K, van Deurs B. Endocytosis and intracellular transport of ricin: recent discoveries. FEBS Lett. 1999;452:67–70. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00529-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scales SJ, Pepperkok R, Kreis TE. Visualization of ER-to-Golgi transport in living cells reveals a sequential mode of action for COPII and COPI. Cell. 1997;90:1137–1148. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80379-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schapiro FB, Lingwood C, Furuya W, Grinstein S. pH-independent retrograde targeting of glycolipids to the Golgi complex. Am. J. Physiol. 1998;274:C319–C332. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.274.2.C319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson JC, Dascher C, Roberts LM, Lord JM, Balch WE. Ricin cytotoxicity is sensitive to recycling between the endoplasmic reticulum and the Golgi complex. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:20078–20083. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.34.20078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DC, Lord JM, Roberts LM, Johannes L. Glycosphingolipids as toxin receptors. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2004;15:397–408. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2004.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DC, Sillence DJ, Falguières T, Jarvis RM, Johannes L, Lord JM, Platt FM, Roberts LM. Lipid raft association of Shiga-like toxin is modulated by glycosylceramide and is an essential requirement in the endoplasmic reticulum for a cytotoxic effect. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2006a;17:1375–1387. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-11-1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DC, Spooner RA, Watson PD, Murray LJ, Hodge TW, Johannes L, Lord JM, Roberts LM. Internalized Pseudomonas exotoxin A can exploit multiple pathways to reach the endoplasmic reticulum. Traffic. 2006b;7:379–393. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2006.00391.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suga K, Hattori H, Saito A, Akagawa K. RNA interference-mediated silencing of the syntaxin 5 gene induces Golgi fragmentation but capable of transporting vesicles. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:4226–4234. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.06.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tai G, Lu L, Johannes L, Hong W. Functional analysis of Arl1 and golgin-97 in endosome-to-TGN transport using recombinant Shiga toxin B fragment. Methods Enzymol. 2005;404:442–453. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)04039-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tai G, Lu L, Wang TL, Tang BL, Goud B, Johannes L, Hong W. Participation of syntaxin 5/Ykt6/GS28/GS15 SNARE complex in transport from the early/recycling endosome to the TGN. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2004;15:4011–4022. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-12-0876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang BL, Low DY, Lee SS, Tan AE, Hong W. Molecular cloning and localization of human syntaxin 16, a member of the syntaxin family of SNARE proteins. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1998a;242:673–679. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.8029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang BL, Low DY, Tan AE, Hong W. Syntaxin 10: a member of the syntaxin family localized to the trans- Golgi network. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1998b;242:345–350. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdez AC, Cabaniols JP, Brown MJ, Roche PA. Syntaxin 11 is associated with SNAP-23 on late endosomes and the trans- Golgi network. J. Cell Sci. 1999;112:845–854. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.6.845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waguri S, Dewitte F, Le Borgne R, Rouille Y, Uchiyama Y, Dubremetz JF, Hoflack B. Visualization of TGN to endosome trafficking through fluorescently labeled MPR and AP-1 in living cells. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2003;14:142–155. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-06-0338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Tai G, Johannes L, Hong W, Tang BL. Syntaxin 10 at the trans-Golgi network can potentially interact with, but is functionally distinct from syntaxins 6 and 16. Mol. Membr. Biol. 2005;22:313–325. doi: 10.1080/09687860500143829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcke M, Johannes L, Galli T, Mayau V, Goud B, Salamero J. Rab11 regulates the compartmentalization of early endosomes required for efficient transport from early endosomes to the trans-Golgi network. J. Cell Biol. 2000;151:1207–1220. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.6.1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiley HS, Burke PM. Regulation of receptor tyrosine kinase signaling by endocytic trafficking. Traffic. 2001;2:12–18. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2001.020103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Martin S, James DE, Hong W. GS15 Forms a SNARE Complex with Syntaxin 5, GS28, and Ykt6 and Is Implicated in Traffic in the Early Cisternae of the Golgi Apparatus. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2002;13:3493–3507. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-01-0004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida T, Chen CC, Zhang MS, Wu HC. Disruption of the Golgi apparatus by brefeldin A inhibits the cytotoxicity of ricin, modeccin, and Pseudomonas toxin. Exp. Cell Res. 1991;192:389–395. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(91)90056-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]