Abstract

A strict temporal order of maternal mRNA translation is essential for meiotic cell cycle progression in oocytes of the frog Xenopus laevis. The molecular mechanisms controlling the ordered pattern of mRNA translational activation have not been elucidated. We report a novel role for the neural stem cell regulatory protein, Musashi, in controlling the translational activation of the mRNA encoding the Mos proto-oncogene during meiotic cell cycle progression. We demonstrate that Musashi interacts specifically with the polyadenylation response element in the 3′ untranslated region of the Mos mRNA and that this interaction is necessary for early Mos mRNA translational activation. A dominant inhibitory form of Musashi blocks maternal mRNA cytoplasmic polyadenylation and meiotic cell cycle progression. Our data suggest that Musashi is a target of the initiating progesterone signaling pathway and reveal that late cytoplasmic polyadenylation element-directed mRNA translation requires early, Musashi-dependent mRNA translation. These findings indicate that Musashi function is necessary to establish the temporal order of maternal mRNA translation during Xenopus meiotic cell cycle progression.

Keywords: cell cycle, cytoplasmic polyadenylation, Mos, Xenopus

Introduction

Regulated mRNA translation is emerging as a key mechanism to control temporal and spatial gene expression during numerous cellular and developmental processes including sex determination, anterior–posterior specification of the embryonic body axis, neuronal synaptic plasticity, neural stem cell self-renewal and control of vertebrate oocyte maturation (Kuersten and Goodwin, 2003). Regulatory elements within the 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions (UTRs) of target mRNAs are recognized by sequence-specific RNA protein complexes to mediate translational control (Wilkie et al, 2003; Colegrove-Otero et al, 2005; de Moor et al, 2005). Distinct mRNA translational regulatory pathways may function interdependently to coordinate and effect cellular and developmental decisions (Kuersten and Goodwin, 2003). The molecular mechanisms that effect these precise temporal and/or spatial changes in mRNA translation in response to cellular signal transduction pathways have not been well characterized.

Hormonally induced maturation in oocytes of the frog Xenopus laevis requires the temporally regulated translation of maternally derived mRNAs for meiotic cell cycle progression. The translational induction of the mRNA encoding the Mos proto-oncogene is necessary for meiotic cell cycle progression (Sagata et al, 1988, 1989; Furuno et al, 1994; Sheets et al, 1995; Dupre et al, 2002) and occurs soon (2–3 h) after exposure to the maturation stimulus, progesterone. In the absence of early Mos mRNA translation and subsequent activation of mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase signaling, oocytes exhibit delayed germinal vesicle breakdown (GVBD), meiosis I and fail to transition to meiosis II (Furuno et al, 1994; Gross et al, 2000; Dupre et al, 2002). By contrast, translational induction of the mRNA encoding the Wee1 protein tyrosine kinase occurs later in maturation, coincident with completion of GVBD (Kobayashi et al, 1991; Murakami and Vande Woude, 1998; Charlesworth et al, 2000). Inappropriate early translation of the Wee1 mRNA blocks activation of maturation promoting factor (MPF) and prevents meiotic cell cycle progression (Murakami and Vande Woude, 1998; Howard et al, 1999; Nakajo et al, 2000).

It has been recently recognized that the differential timing of Xenopus maternal mRNA translation is controlled through distinct 3′ UTR regulatory elements that direct the cytoplasmic polyadenylation of the target mRNAs (Charlesworth et al, 2002). The late polyadenylation and translational activation of the Wee1 mRNA is enforced by 3′ UTR cytoplasmic polyadenylation element (CPE) sequences (Charlesworth et al, 2000). By contrast, the early polyadenylation and translation of the Mos mRNA is controlled by a 3′ UTR polyadenylation response element (PRE) in a CPE-independent manner (Charlesworth et al, 2002). The PRE has been shown to be responsive to MAP kinase signaling (Charlesworth et al, 2002), whereas the CPE is responsive to MPF signaling (Paris et al, 1991; de Moor and Richter, 1997; Howard et al, 1999; Charlesworth et al, 2002). As progesterone-stimulated MAP kinase activation precedes MPF activation, the differential responsiveness of the 3′ UTR regulatory elements to these signaling pathways would effect temporal discrimination of maternal mRNA selection (Howard et al, 1999; Charlesworth et al, 2002).

In contrast to the MAP kinase-dependent feedback (Matten et al, 1996; Roy et al, 1996; Howard et al, 1999; Charlesworth et al, 2002), initial Mos mRNA translation is induced in a MAP kinase-independent manner (Gross et al, 2000) and is a prerequisite for progesterone-stimulated Xenopus p42 MAP kinase activation (Roy et al, 1996; Dupre et al, 2002). Progesterone stimulation leads to a rapid decrease in oocyte cAMP levels (reviewed in Smith, 1989) and PKA activity (Wang and Liu, 2004). Initiation of Mos mRNA translational activation has been shown to be downstream of progesterone-mediated PKA inhibition (Daar et al, 1993; Qian et al, 2001). The mediators of the progesterone ‘trigger' signaling pathway leading to Mos mRNA translational activation have not been elucidated, but presumably regulate a trans-acting factor that binds to the PRE in the Mos 3′ UTR. The identity of the trans-acting factor controlling early PRE-dependent mRNA translational activation has not been determined.

In this study, we demonstrate that Xenopus Musashi is a trans-acting PRE binding protein that is necessary for maternal mRNA translational activation in Xenopus oocytes. Musashi has been previously shown to be essential for asymmetric cell divisions of Drosophila neural progenitor cell populations and in mammalian neural stem cell self-renewal, where it appears to function as an mRNA translational repressor (Okano et al, 2002, 2005). Our findings reveal a novel role for Musashi in mediating mRNA translational activation during Xenopus oocyte maturation. Inhibition of Musashi function through expression of a dominant inhibitory form of Musashi specifically attenuated maternal mRNA translational activation and oocyte meiotic cell cycle progression in response to progesterone stimulation. We report that Musashi-mediated mRNA translational activation is a prerequisite for the subsequent translation of CPE-dependent mRNAs, indicating a critical role for Musashi in controlling the temporal order of maternal mRNA translational activation.

Results

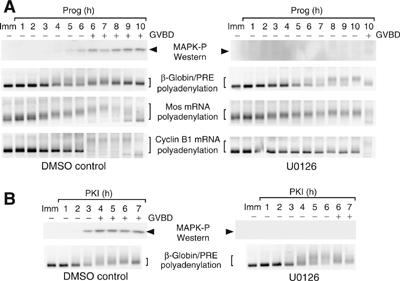

The Mos PRE is a target of the progesterone ‘trigger' signaling pathway

To determine if the Mos PRE was a direct target of the MAP kinase-independent progesterone trigger pathway, oocytes were treated with the MAP kinase pathway inhibitor U0126. U0126 significantly attenuated the rate of oocyte maturation (a 4 h delay to GVBD50; Figure 1A) and abolished progesterone-stimulated MAP kinase activation, as previously reported (Gross et al, 2000). However, the initiation of endogenous Mos mRNA polyadenylation occurred with similar kinetics in the presence or absence of U0126, although the length of the poly[A] tail extension was reduced in U0126-treated oocytes. By contrast, CPE-directed polyadenylation of the endogenous cyclin B1 mRNA was significantly delayed in the U0126-treated oocytes, occurring coincident with GVBD. As the β-globin 3′ UTR does not undergo any significant polyadenylation (Charlesworth et al, 2002, 2004), the Mos PRE was inserted into the β-globin 3′ UTR to directly determine if the PRE was sufficient to direct MAP kinase-independent polyadenylation. Initiation of PRE-directed polyadenylation of the β-globin 3′ UTR occurred with similar kinetics in the presence or absence of U0126 (Figure 1A), although some differences in overall length of poly[A] tail extension can be seen between the two treatments. Injection of the PKA inhibitor (PKI) has been shown to induce progesterone-independent oocyte maturation (Huchon et al, 1981; Davidson, 1986). To determine if the PRE was downstream of PKA inhibition, we analyzed PRE-directed polyadenylation following injection of PKI. PKI induced PRE-directed polyadenylation of the β-globin 3′ UTR reporter mRNA, even in the presence of U0126 (Figure 1B). These findings indicate that the Mos PRE is downstream of PKA inhibition and is a target of the MAP kinase-independent progesterone trigger signaling pathway.

Figure 1.

The Mos PRE is responsive to a MAP kinase-independent trigger pathway. (A) Immature oocytes were injected with RNA encoding the GST coding region fused to the β-globin 3′ UTR containing the Mos PRE (β-globin/PRE). Oocytes were pretreated where indicated with U0126 and then stimulated with progesterone. Protein and RNA were extracted from the same pools of oocytes at the specified times. Progression of maturation is indicated by whether the oocytes had (+) or had not (−) undergone GVBD. Top panel is a Western blot for active (phosphorylated) MAP kinase (arrowhead). Lysates from DMSO- and UO126-treated oocytes were processed and analyzed in parallel. Lower panels show polyadenylation (brackets) of the endogenous Mos and cyclin B1 mRNAs and the injected synthetic β-globin/PRE reporter mRNA, as assayed by RNA ligation-coupled RT–PCR from the same cDNA preparation. Retardation of the PCR products is indicative of polyadenylation. (B) Immature oocytes were injected with the β-globin/PRE reporter. Oocytes were pretreated where indicated with U0126 and then stimulated by injection of recombinant PKI protein. Top panel is a Western blot for active (phosphorylated) MAP kinase (arrowhead). Lysates from DMSO-and UO126-treated oocytes were processed and analyzed in parallel. Lower panels show polyadenylation of the injected synthetic β-globin/PRE reporter (brackets).

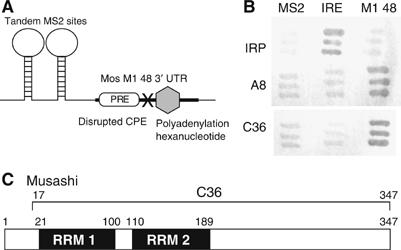

Xenopus Musashi is a Mos 3′ UTR interacting protein

We next sought to identify potential RNA sequence-specific binding proteins that control PRE function. The yeast three-hybrid system (SenGupta et al, 1996, 1999; Zhang et al, 1999; Bernstein et al, 2002) was used to screen a X. laevis pACT2 unfertilized egg cDNA library (Clontech) for proteins that specifically interact with a CPE-disrupted Mos UTR (Mos M1 48; Figure 2A). The CPE sequence was disrupted to prevent possible recovery of the CPE binding protein (CPEB1) in the library screen. In total, 1.3 × 107 initial yeast transformants were screened (Supplementary Table I) and two distinct cDNAs (designated A8 and C36) were recovered and shown to reconstitute specific RNA interaction with the Mos 3′ UTR (Figure 2B, M1 48). The protein encoded by the A8 cDNA interacts specifically with the Mos 3′ UTR but does not interact with the PRE sequence and will be described elsewhere (Charlesworth and MacNicol, in preparation).

Figure 2.

Identification of Mos UTR-specific binding proteins by yeast three-hybrid analyses. (A) Diagram of the RNA hybrid in the pIIIA/MS2 vector that was used to screen the Xenopus oocyte library. The last 48 nt of the Mos 3′ UTR (M1 48, bold line) containing the PRE (open rectangle), the canonical polyadenylation hexanucleotide (gray hexagon) and a disrupted CPE (‘X', UUUUAU to UUUggU) were placed 3′ of the MS2 sites. (B) Clones A8 and C36 specifically bind to the Mos M1 48 hybrid RNA. pACT2 plasmids encoding A8 and C36 clones and IRP (iron response protein) hybrid proteins were co-transformed with pIIIA/MS2 plasmids specifying MS2 (empty vector), IRE/MS2 (IRE: iron response element) and MS2/M1 48 (M1 48) hybrid RNAs. Dark gray shows activation of the LacZ reporter, indicating interaction between protein and RNA. (C) Schematic of the Xenopus Musashi protein. The black boxes represent the RNA recognition motifs (RRM) of Musashi. Amino-acid position of the motifs and the fragment of Musashi (C36) that was recovered from the screen are indicated.

The pACT2 C36 cDNA was identical to amino acids 17–347 of nervous system-specific RNP protein 1b (Nrp-1b), more recently identified as the Xenopus homolog of the Drosophila Musashi gene (Good et al, 1993, 1998). Xenopus Musashi has two RNA recognition motifs in the N-terminal region (Figure 2C) that are highly conserved (87% amino-acid identity) with the mammalian Musashi1 protein. The Xenopus Musashi protein localizes to the cytoplasm of the oocyte (Good et al, 1993), consistent with a potential role in the regulation of cytoplasmic mRNA translation.

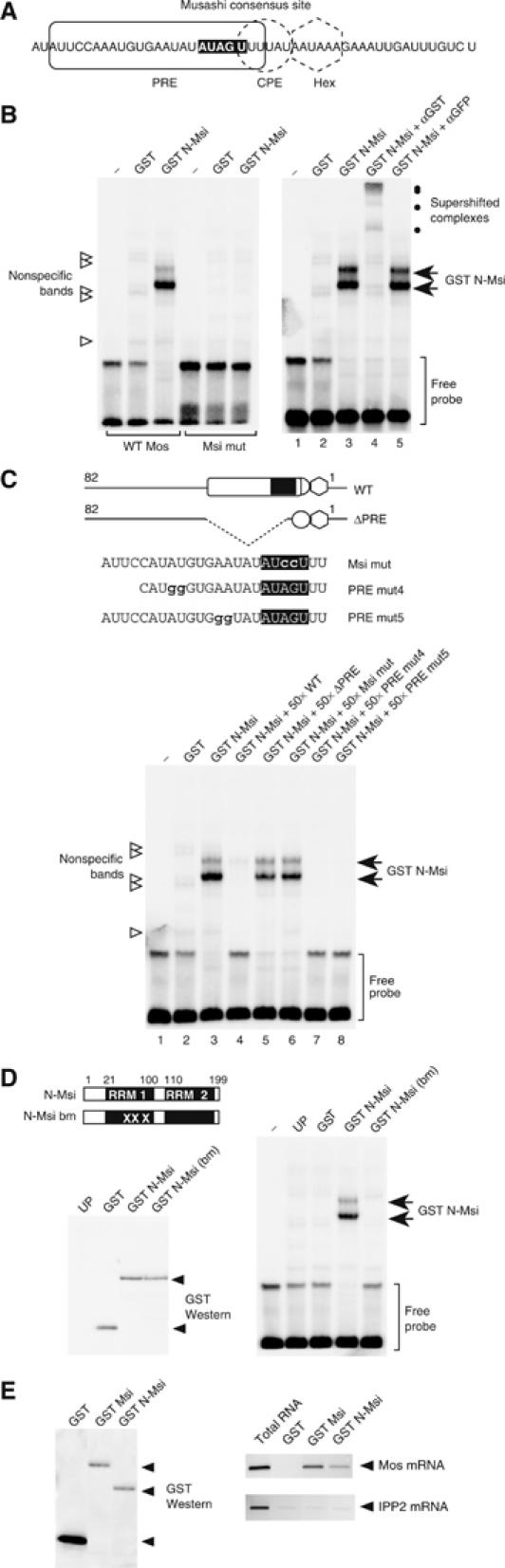

Musashi binds specifically to the PRE in the Mos 3′ UTR

The 24-nt Xenopus Mos PRE (Charlesworth et al, 2002) contained a match to the SELEX-derived murine Musashi RNA binding consensus sequence (G/AU1−3AGU) (Imai et al, 2001), and included a 3′ U residue essential for PRE function (Charlesworth et al, 2002) (Figure 3A, white nucleotides). Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) were performed to verify that Musashi interacts specifically with the Mos 3′ UTR. GST-tagged N-terminal Musashi (GST N-Msi), but not the GST moiety alone or unprogrammed reticulocyte lysate, formed specific complexes with the wild-type Mos UTR probe (Figure 3B, left panel). Musashi did not form a complex with the Mos UTR when the Musashi binding site was disrupted (AUAGU to AUccU; Figure 3B, right panel). Moreover, the Musashi-specific complexes formed with GST N-Msi could be supershifted with GST antisera, but not GFP antisera (Figure 3B, right panel). To delineate the Musashi target sequence within the PRE, we performed a competition experiment using 50-fold molar excess of unlabeled wild-type Mos UTR probe or unlabeled mutant Mos UTRs (Figure 3C). Whereas Musashi-specific binding to the wild-type Mos UTR probe was competed by unlabeled wild-type Mos UTR, Musashi-specific complex formation was not competed with a Mos UTR carrying a disruption in the Musashi binding site (Msi mut) or a Mos UTR lacking the 24-nt PRE (ΔPRE). Two additional RNAs encoding PRE mutations 5′ of the Musashi binding site effectively competed Musashi complex formation (Figure 3C). These findings indicate that Musashi does not bind to the 5′ region of the PRE, although our data do not exclude a role for the 5′ region of the PRE in facilitating Musashi function. Musashi-specific complex formation with the wild-type Mos UTR was not observed with the RNA binding-deficient form of the truncated Musashi protein (N-Msi-bm; Figure 3D), which encodes three amino-acid substitutions in the first RRM domain (Imai et al, 2001). Taken together, these results demonstrate that Xenopus Musashi interacts specifically with the consensus Musashi binding site within the Mos PRE sequence. As an additional demonstration of specific RNA binding, the full-length Musashi (Msi) and N-Msi proteins were able to interact with the endogenous Mos mRNA but not with the IPP2 mRNA that lacks a consensus Musashi binding site in the 3′ UTR (Figure 3E). No association of either Mos or IPP2 mRNAs was detected with the GST moiety alone.

Figure 3.

Musashi binds to the PRE in the Mos 3′ UTR. (A) Schematic showing regulatory element composition within the last 50 nt of the Mos 3′ UTR. The Musashi consensus binding site is indicated by white nucleotides. (B) Left panel: Wild-type (WT Mos) or Musashi binding site mutant (Msi mut) Mos UTR probes were analyzed for interaction with the GST-tagged, N-terminal domain of Xenopus Musashi (GST N-Msi) by RNA EMSA. Specific Musashi binding complexes were only detected with the wild-type Mos UTR probe. Right panel: Musashi-specific complex formation with the wild-type Mos UTR probe can be supershifted with antisera to the GST epitope tag and not with GFP antisera. (C) Musashi-specific complex formation with the wild-type Mos UTR probe can be competed with a 50-fold excess unlabeled wild-type, PRE mut4 and PRE mut5 Mos UTR RNA. No competition is observed with a Mos UTR lacking the entire PRE (ΔPRE) or a Musashi binding site mutant (Msi mut) Mos UTR. (D) Disruption of the first RRM in Musashi (GST N-Msi-bm) prevents Musashi-specific complex formation with the wild-type Mos UTR probe (right panel). Equivalent levels of each GST fusion protein were expressed in the reticulocyte lysates (left panel). UP, unprogrammed lysate. (E) The full-length (GST Msi) and N-terminal domain of Musashi (GST N-Msi) interact with the endogenous Mos mRNA. Left panel: GST Western blot showing recovery of exogenously expressed GST fusion proteins using glutathione Sepharose beads. Equivalent levels of GST Msi and GST N-Msi and higher levels of the GST moiety were recovered in the pulldown. Right panel: RT–PCR of Mos and IPP2 mRNA from RNA extracted from the indicated GST fusion proteins shown in the left panel. GST-Msi and GST-N-Msi interact with the Mos mRNA but do not interact with the IPP2 mRNA. The GST moiety alone fails to interact with either Mos or IPP2 mRNAs. RT–PCR from total oocyte RNA was used as a positive control to indicate the relative position of the expected PCR products in the pulldown lanes.

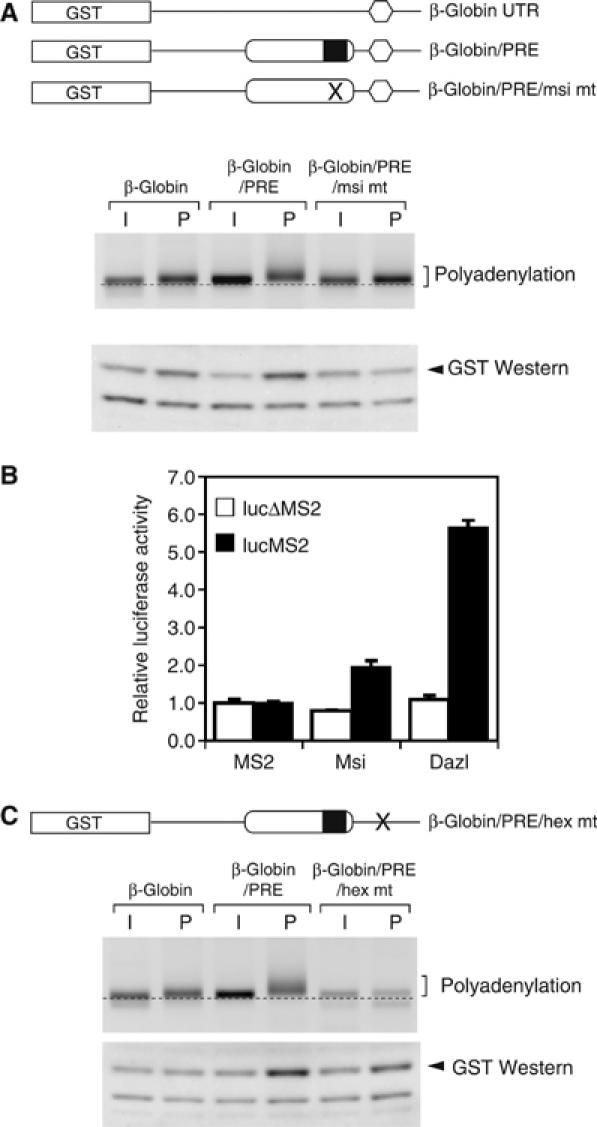

Musashi interaction with the Mos 3′ UTR is necessary for early translational activation

To determine whether the Musashi consensus site was necessary for early, CPE-independent mRNA translational activation directed by the Mos PRE (Charlesworth et al, 2002, 2004), disruptive nucleotide substitutions were introduced into the Musashi consensus sequence (AUAGU to AUccU) and the polyadenylation and translation of reporter mRNAs analyzed. Insertion of the Mos PRE into the heterologous β-globin 3′ UTR confers progesterone-dependent polyadenylation and translational activation (two- to three-fold above β-globin alone; Figure 4A), whereas disruption of the Musashi binding site (PRE/msi mt) abolished this regulation (Figure 4A). These findings indicate that the integrity of the Musashi consensus site is critical for the translational activation directed by the Mos PRE. A role for the Musashi protein in mRNA translational activation in Xenopus oocytes was independently confirmed through the use of the MS2 tethered assay (Gray et al, 2000; Minshall et al, 2001; Collier et al, 2005). As can be seen in Figure 4B, fusion of Musashi to the MS2 RNA binding domain directed a two-fold stimulation of a firefly luciferase reporter mRNA containing 3′ UTR MS2 binding sites. No induction of the luciferase reporter mRNA was observed with the MS2 RNA binding domain alone, nor with a luciferase reporter mRNA lacking MS2 binding sites (ΔMS2; Figure 4B). In these experiments, the MS2-Dazl fusion protein serves as a positive control for translational induction (Collier et al, 2005). The firefly luciferase reporter mRNAs used in the tethered assay lack a consensus polyadenylation hexanucleotide, suggesting that tethering of Musashi can direct translation independently of polyadenylation. To test this directly, the polyadenylation hexanucleotide in the GST β-globin/PRE reporter mRNA was disrupted (AAUAAA to AAgAAA; Fox et al, 1989) to generate GST β-globin/PRE/hex mt. While eliminating progesterone-dependent polyadenylation, disruption of the polyadenylation hexanucleotide reduced, but did not eliminate, PRE-directed mRNA translation (approximately 1.5-fold above β-globin alone; Figure 4C). These findings suggest that the Musashi binding site in the Mos PRE directs both polyadenylation and translation in response to progesterone, but that polyadenylation is not obligatory for PRE-directed mRNA translation.

Figure 4.

Musashi directs mRNA translational activation. (A) Upper panel: Schematic representation of the reporter mRNAs analyzed. The GST open reading frame (box) was fused to the β-globin 3′ UTR, or β-globin 3′ UTRs containing either the wild-type (PRE) or Musashi binding site mutant (PRE/msi mt) Mos PRE sequences. Middle panel: Polyadenylation of the indicated reporter mRNAs was assessed by RNA ligation-coupled PCR from time-matched immature (I) or progesterone-stimulated (P) oocytes taken at GVBD50 from oocytes without white spots. Retarded migration of PCR products above the dotted line is indicative of polyadenylation. Lower panel: Western blot showing GST accumulation from time-matched immature or progesterone-stimulated oocytes taken at GVBD100. (B) Tethered assay demonstrating the ability of MS2-Msi and MS2-Dazl fusion proteins to induce firefly luciferase expression. Open and solid bars represent luciferase reporters lacking or containing MS2 binding sites in the 3′ UTR, respectively. Luciferase activity was determined in triplicate and normalized to expression of the coinjected Renilla luciferase mRNA. Error bars represent standard deviation of the mean. The experiment was repeated three times with similar results. (C) Oocytes were injected with GST reporter mRNAs fused to the β-globin 3′ UTR, the β-globin 3′ UTR containing the Mos PRE (PRE) or the β-globin 3′ UTR containing the Mos PRE (PRE) and a disrupted polyadenylation hexanucleotide (hex mt). The polyadenylation and translation of GST reporter mRNAs were analyzed as described in (A).

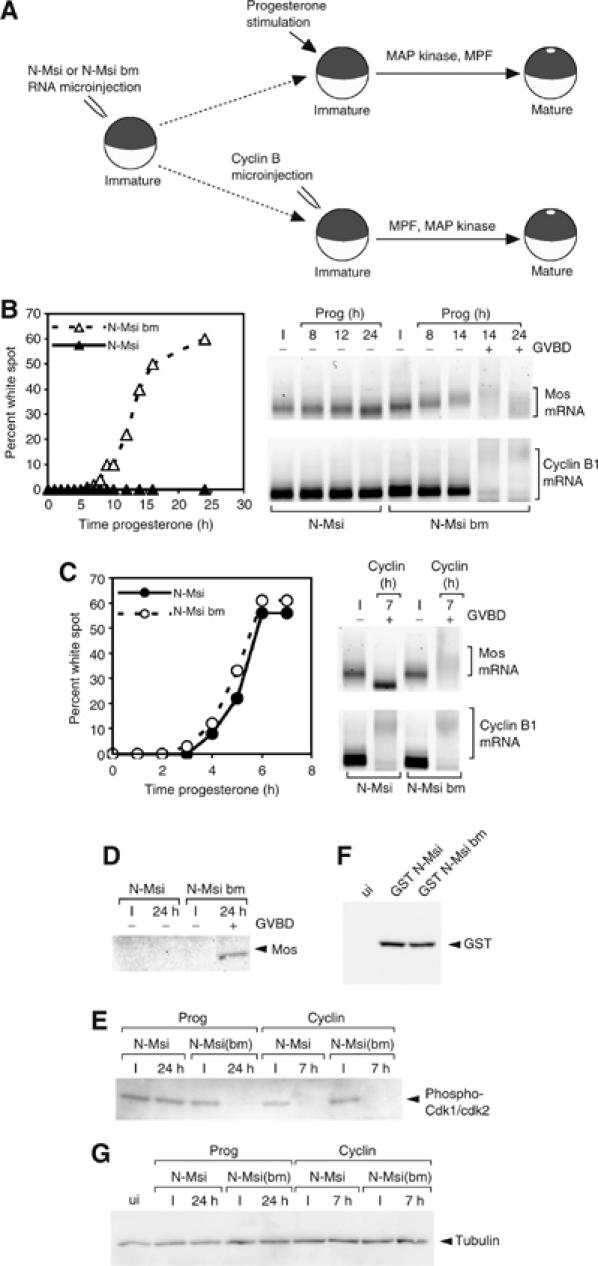

A truncated form of Musashi blocks Xenopus oocyte meiotic cell cycle progression

We reasoned that expression of a truncated form of Musashi encompassing only the RNA binding domain (N-Msi, aa 1–199) may function in a dominant inhibitory manner to block early Mos mRNA polyadenylation and translational activation in response to progesterone stimulation. Immature oocytes were injected with mRNA encoding either N-Msi or the RNA binding-deficient N-Msi-bm (Figure 3D). Compared to the N-Msi-bm-expressing oocytes, expression of N-Msi dramatically attenuated progesterone-stimulated oocyte maturation (Figure 5B, left panel). To determine the molecular basis for the block to oocyte maturation exerted by N-Msi, oocytes were analyzed for endogenous Mos and cyclin B1 mRNA polyadenylation. In contrast to the polyadenylation of the Mos mRNA in N-Msi-bm-expressing oocytes, Mos mRNA polyadenylation was attenuated in oocytes expressing N-Msi at all time points analyzed (Figure 5B, upper right panel). The polyadenylation of the cyclin B1 mRNA is a late event in progesterone-stimulated maturation and occurs coincident with oocyte GVBD (Sheets et al, 1994; Ballantyne et al, 1997; de Moor and Richter, 1997; Charlesworth et al, 2004). In N-Msi-bm-expressing oocytes, cyclin B1 mRNA polyadenylation occurred coincident with GVBD as expected, whereas expression of N-Msi protein prevented progesterone-stimulated GVBD and ablated cyclin B1 polyadenylation, even at late time points (Figure 5B, lower right panel). Two possible explanations could account for the inhibitory effect of N-Msi on cyclin B1 polyadenylation. First, N-Msi may exert an inhibitory effect by directly binding to the cyclin B1 3′ UTR and blocking CPE-dependent cytoplasmic polyadenylation. Alternatively, the effect of N-Msi may be indirect and occur through inhibition of Musashi-dependent mRNA translation events required for GVBD and/or the activation of CPE-dependent mRNA polyadenylation. To distinguish between these possibilities, oocytes were microinjected with cyclin B1 protein to induce activation of MPF independently of progesterone stimulation (Freeman et al, 1991) and reverse the relative order of MAP kinase and MPF activation (Figure 5A; Charlesworth et al, 2002). N-Msi did not block cyclin B protein-induced maturation and the kinetics of maturation were indistinguishable between N-Msi- and N-Msi-bm-expressing oocytes (Figure 5C, left panel). Cyclin B protein induced the polyadenylation of the endogenous cyclin B1 mRNA in both N-Msi- and N-Msi-bm-expressing oocytes (Figure 5C, right panel). These results indicate that CPE-dependent polyadenylation of the cyclin B1 mRNA can occur in oocytes expressing dominant-negative Musashi if MPF is activated independently of progesterone-triggered early signaling effectors. By contrast, cyclin B-induced Mos mRNA polyadenylation was abrogated in N-Msi-, but not N-Msi-bm-, expressing oocytes (Figure 5C, right panel) demonstrating the specificity of N-Msi-mediated inhibition on PRE-regulated mRNAs irrespective of initiating signal. Mos mRNA deadenylation was observed in the N-Msi-expressing oocytes after GVBD. We conclude that the dominant-negative Musashi specifically blocks early progesterone effector pathways (including Mos mRNA translational activation) and the inhibition of CPE-dependent mRNA polyadenylation is an indirect consequence of a block to upstream Musashi-regulated mRNA translation events. Consistent with a block to Mos mRNA polyadenylation, progesterone-stimulated Mos protein accumulation was abrogated in N-Msi (but not N-Msi-bm)-expressing oocytes (Figure 5D). N-Msi, but not N-Msi-bm, also prevented progesterone-dependent activation of MPF (Figure 5E). In these experiments, the N-Msi and N-Msi-bm mutant proteins were expressed to comparable levels (Figure 5F). Although we cannot exclude additional effects of the truncated Musashi protein (N-Msi) on processes upstream of mRNA polyadenylation and translational activation, the inability of an RNA binding-deficient form of the truncated protein (N-Msi-bm) to block progesterone-stimulated cytoplasmic polyadenylation or cell cycle progression indicates that effect of the dominant inhibitory Musashi is primarily due to interaction with mRNA targets. Taken together, our data provide compelling evidence that Musashi regulates maternal mRNA translation and MPF activation during progesterone-stimulated meiotic cell cycle progression.

Figure 5.

Dominant inhibitory Musashi blocks oocyte maturation and specifically prevents Mos polyadenylation and translation. (A) Schematic of experimental design. RNA encoding GST-tagged N-Msi or N-Msi-bm was injected into immature oocytes, which were left for 36 h to express the protein. Oocytes were then stimulated to mature either by addition of progesterone or injection of cyclin B protein. (B) Progesterone-stimulated maturation was scored by the appearance of a white spot at the animal pole and indicated by whether the oocytes had (+) or had not (−) undergone GVBD. The polyadenylation of endogenous Mos (upper panels) and cyclin B1 (lower panels) mRNAs was assessed by RNA ligation-coupled RT–PCR (brackets). In this experiment, progesterone-stimulated N-Msi-bm-expressing oocytes reached GVBD50 at 14 h. (C) Oocytes were injected with cyclin B1 protein and the effect on maturation and mRNA polyadenylation was assessed as in (B). (D) The expression of Mos protein in immature (I) or progesterone-stimulated (24 h) oocytes from experiment B was determined by Western blot. (E) The activation status of MPF in lysates prepared from experiments B and C was assessed using antisera specific to inactive CDK1 and CDK2. (F) Western blot showing equivalent levels of GST-tagged N-Msi or N-Msi-bm expressed in oocytes used for experiments B and C. ui, uninjected lysate. (G) Tubulin Western blot showing equal protein loading in lysates analyzed in panels D–F.

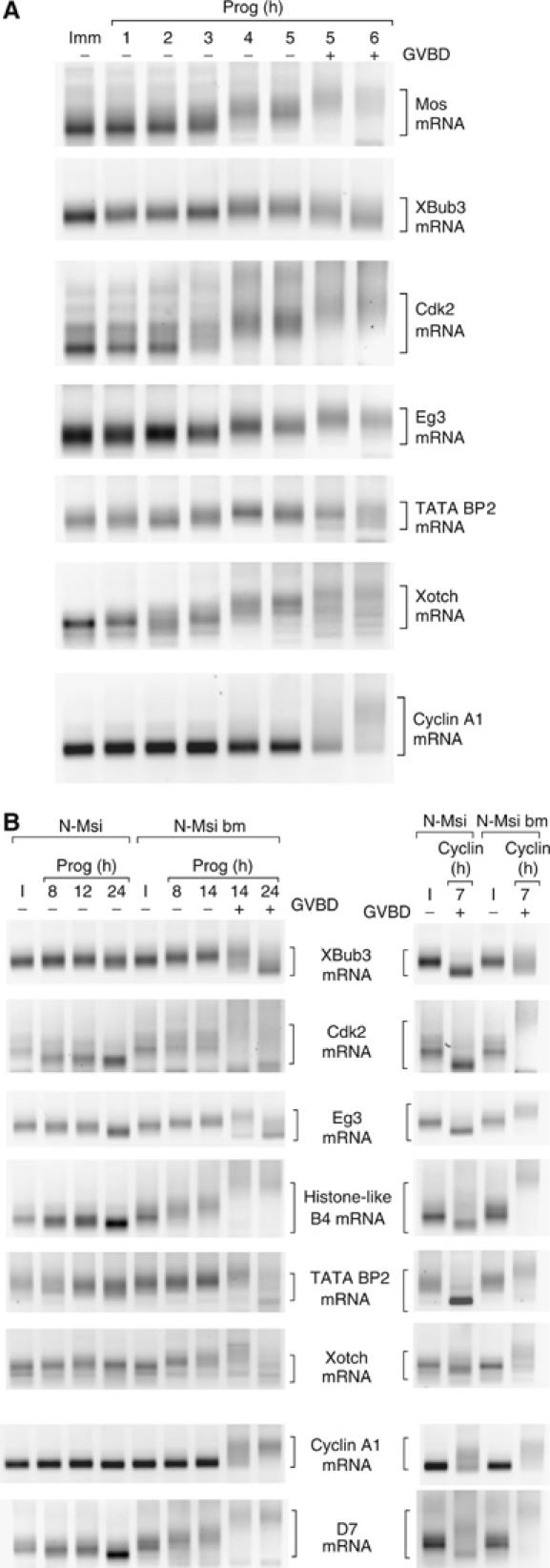

Musashi regulates polyadenylation of multiple Xenopus mRNAs

We next determined if Musashi could regulate additional Xenopus mRNAs. The mammalian Musashi consensus sequence (A/G)U1−3AGU (Imai et al, 2001) was identified in 9.4% of Xenopus mRNA in the 3′ UTR database (Mignone et al, 2005). Musashi binding sites were found in the previously characterized early class mRNAs Mos, Aurora A/Eg2, D7 and FGF receptor 1 (Charlesworth et al, 2002, 2004), as well as in the late class cyclin B1 and cyclin A1 mRNAs. In addition, the Eg1/CDK2, Eg3, Xotch (Xenopus Notch), Bub3, and TATA binding protein 2 mRNAs were identified as having a Musashi site within the last 150 nt of the 3′ UTR. Consistent with Musashi- and PRE-directed regulation, the Eg1/CDK2, Eg3, Xotch (Xenopus Notch), Bub3 and TATA binding protein 2 mRNAs were polyadenylated in an early manner, before oocyte GVBD (Figure 6A). The length of the poly[A] tail extension varied between the different mRNAs but was not obviously correlated with position or sequence of the Musashi binding site within the 3′ UTRs. In contrast to the early mRNAs, polyadenylation of the CPE-dependent cyclin A1 mRNA occurred later, coincident with oocyte GVBD.

Figure 6.

Musashi regulates progesterone-dependent polyadenylation of multiple mRNAs. (A) Time course of polyadenylation of endogenous mRNAs was assayed from the same cDNA preparation using appropriate gene-specific forward primers. Brackets indicate the extent of mRNA polyadenylation. Progression of maturation is indicated by whether the oocytes have (+) or have not (−) undergone GVBD. In this experiment, progesterone-stimulated N-Msi-bm-expressing oocytes reached GVBD50 at 14 h. (B) Polyadenylation of the indicated endogenous mRNAs was assessed following progesterone stimulation (left panel) or cyclin B1 protein injection (right panel) as described in Figure 5. Cyclin B1 protein-stimulated polyadenylation of the mRNAs in the six upper panels is prevented by N-Msi. Cyclin B1 protein-stimulated polyadenylation of the mRNAs in the lower two panels is not prevented by N-Msi. Brackets indicate the extent of mRNA polyadenylation or deadenylation.

The progesterone-stimulated polyadenylation of the mRNAs analyzed in Figure 6A was ablated in oocytes expressing the dominant inhibitory N-Msi, but not the N-Msi-bm, protein (Figure 6B, left panels). As the PCR products of the early class mRNAs were reduced at late time points in progesterone-stimulated oocytes expressing N-Msi, our data suggest that these mRNAs become deadenylated. No apparent deadenylation of the late class cyclin A1 mRNA was observed in N-Msi-expressing oocytes. Active PRE-directed polyadenylation may normally preclude access of deadenylation factors or directly oppose deadenylation of early class mRNAs in maturing oocytes. The presence of a polyadenylation hexanucleotide-overlapping CPE, common to both the cyclin A1 and cyclin B1 3′ UTRs, may protect the late class mRNAs from deadenylation (see also Figure 5). With the exception of D7 and cyclin A1, mRNA polyadenylation was abrogated in N-Msi-, but not N-Msi-bm-, expressing oocytes injected with cyclin B protein. Cyclin B protein induced polyadenylation of the D7 and cyclin A1 mRNAs in the presence of N-Msi, suggesting that the CPE sequences in these 3′ UTRs were responsive to MPF signaling. These findings indicate that Musashi regulates the translational activation of multiple maternal mRNAs during progesterone-stimulated Xenopus oocyte meiotic cell cycle progression.

Discussion

Our previous studies have identified the cis-acting PRE element as a determinant of MAP kinase-dependent mRNA translational regulation during Xenopus meiotic cell cycle progression (Charlesworth et al, 2002, 2004). In this study, we show that the PRE is also a target of the MAP kinase-independent progesterone ‘trigger' pathway. Furthermore, we have identified Xenopus Musashi as a regulator of PRE-directed Mos mRNA translational activation. Our results position Musashi as a mediator of the progesterone-stimulated ‘trigger' signaling pathway that is necessary for initiation of maternal mRNA translational activation and cell cycle progression. The identification of Musashi as a regulator of PRE function was defined by a combination of yeast three-hybrid analyses, in vitro EMSA experiments and functional tests in vivo. In addition to blocking Mos mRNA translation, expression of a dominant-negative Musashi protein abolished CPE-dependent mRNA translational activation in response to progesterone stimulation. The dominant-negative form of Musashi did not block cytoplasmic polyadenylation of CPE-dependent mRNAs following cyclin B1 protein injection (Figure 5), indicating that Musashi-mediated mRNA translation normally precedes, and is necessary for, CPE-dependent mRNA translational activation in response to progesterone stimulation. These findings extend prior studies, which have demonstrated an inherent dependence of late class mRNA translational activation on prior translation of early class mRNAs (Ballantyne et al, 1997; de Moor and Richter, 1997).

Expression of the dominant inhibitory form of Musashi abolished progesterone-stimulated MPF activation and meiotic cell cycle progression (Figure 5). This catastrophic block to cell cycle progression is unlikely to simply reflect inhibition of Mos mRNA translation. Indeed, the inhibition of cell cycle progression exerted by the dominant-negative form of Musashi is different from the effects observed as a result of the inhibition of Mos mRNA translation by antisense Mos morpholino oligonucleotides (Dupre et al, 2002) or pharmacological inhibition of Mos-mediated MAP kinase signaling (Gross et al, 2000), which result in a delay, rather than a block, to GVBD. Our findings suggest that Musashi-dependent translational activation regulates a more comprehensive range of mRNA targets that contribute to induction of MPF and progression to GVBD in response to progesterone stimulation.

The identity of all potential Musashi-regulated mRNAs that contribute to oocyte cell cycle progression has not been established. We have utilized the mammalian Musashi SELEX-derived consensus binding sequence to identify new early class maternal mRNAs that display Musashi-dependent cytoplasmic polyadenylation (Figure 6). However, some Musashi consensus site-containing mRNAs do not exhibit early class polyadenylation (e.g. cyclin B1 and cyclin A1; Figures 5 and 6). Several possibilities may explain these observations including mRNA secondary structure considerations (Imai et al, 2001) or potential inhibitory influences exerted by other regulatory elements in the same 3′ UTR. Consistent with the latter possibility, the cyclin B1 and cyclin A1 3′ UTRs have a CPE that overlaps the polyadenylation hexanucleotide, which may prevent cytoplasmic polyadenylation until the MPF-dependent degradation of bound CPEB1 at GVBD (Mendez et al, 2002).

PRE-like sequences have been identified in the early class mRNAs encoding D7, G10, histone-like B4, Eg2/Aurora A and FGF receptor 1 mRNA 3′ UTRs (Charlesworth et al, 2004). It has not been determined if these PRE-like sequences are equivalent to the Mos PRE or if they represent distinct regulatory elements with similar functional properties. Unlike the Mos PRE, the identified PRE-like sequences lack a consensus Musashi binding site. Nonetheless, Musashi function is necessary for polyadenylation of the PRE-like sequences-containing mRNAs (Figure 6), suggesting that either PRE-like sequences represent additional non-consensus Musashi binding sites or PRE-like function is indirectly controlled through upstream Musashi-dependent mRNA translation events. It is interesting to note that although full Musashi-directed mRNA translation requires polyadenylation in response to progesterone stimulation, Musashi can nonetheless direct a lower level of polyadenylation-independent translation (Figure 4). We are continuing to examine the requirements for Musashi RNA binding, 3′ UTR regulatory element composition and secondary structure to further elucidate the determinants of Musashi-dependent mRNA translational activation.

Musashi has been previously proposed to repress translation of target mRNAs in Drosophila neural progenitor cells, as well as mammalian neural stem cell populations (Imai et al, 2001; Okabe et al, 2001; Battelli et al, 2006). We now report that Musashi is required for Xenopus maternal mRNA translational activation and meiotic cell cycle progression (Figures 4 and 5). The role of Musashi in these different cell types appears to be contradictory. However, despite exerting opposing effects on target mRNA translational regulation, the outcome of Musashi action in each situation is to promote cell cycle progression. It is possible that the differential regulation of target mRNA translation in oocytes and neural stem cells may be exerted through the expression of specific partner proteins or regulators that can differentially enforce Musashi-mediated mRNA repression or translational activation. Given the importance of Musashi function in stem cell self-renewal (Okano et al, 2005) and the possible implications of aberrant Musashi expression in tumors (Kanemura et al, 2001; Toda et al, 2001; Hemmati et al, 2003; Potten et al, 2003; Yokota et al, 2004) and neurodegenerative disorders (Lovell and Markesbery, 2005), it is now critical to understand the molecular mechanisms that control Musashi-mediated mRNA translation. A characterization of the role and regulation of Musashi function during Xenopus oocyte maturation will not only enhance our understanding of this key aspect of reproductive biology but may also provide insight into the mechanisms contributing to stem cell self-renewal.

Materials and methods

Plasmid construction

A detailed methodology of construction of all plasmids used in this study is provided as Supplementary data.

Yeast three-hybrid screen

The yeast three-hybrid screen was performed as described (SenGupta et al, 1996) in the yeast strain YBZ-1 (Bernstein et al, 2002) using the X. laevis oocyte Matchmaker cDNA Library (Clontech). Initial transformants were plated in the presence of 0.5 mM 3-AT to reduce false positives. A summary of the screen is provided in Supplementary Table 1. To investigate binding specificity by mating, the R40 coat strain, transformed with an empty vector (pIIIA MS2-2.1), a negative control plasmid (pIIIA IRE (iron response element)) or pIIIA MS2-2.1 M1 48 was used. The orientation of the Mos UTR relative to the MS2 sites in the hybrid RNA was critical for the success of the screen.

RNA electrophoretic mobility shift assays

GST fusion proteins were in vitro transcribed/translated using TNT SP6-coupled Reticulocyte Lysate System (Promega). 5′ biotin-labeled RNA oligonucleotide probes were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies. An 80 fmol portion of labeled probe was incubated with 1 μl of reticulocyte lysate in binding buffer (50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 20 mM KCl, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EGTA, 0.05% NP-40, 6 mM DTT, 8 U RNase OUT; Okabe et al, 2001) in a final volume of 20 μl. Unlabeled competitor RNA was added to 4 pmol (50-fold molar excess). The binding reaction was incubated at room temperature for 20 min and then 0.5 μl of 200 mg/ml heparin was added and incubated for a further 20 min. For supershift analysis, 1 μl of anti-GST antibody (Santa Cruz) or anti-GFP antibody (Molecular Probes) was added 10 min before the end of the incubation. A 5 μl volume of the binding reaction was run on a 6% DNA retardation gel (Invitrogen) and transferred to Biodyne B membranes (Pierce) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Biotinylated RNA was detected using Chemiluminescent Nucleic Acid Detection Module (Pierce) according to the manufacturer's directions, with the modification that incubation with the streptavidin-HRP conjugate was for 40 min. Image collection was performed using an AlphaInnotech ChemiImager.

Tethered assay

Oocytes were injected with 23 ng of appropriate MS2 fusion protein mRNA, 0.1 ng of firefly luciferase mRNA, 0.35 pg of Renilla luciferase control mRNA and incubated for 20 h. Three pools of five oocytes were harvested for each experimental point and lysed in 50 μl of Passive Lysis Buffer (Promega) per oocyte. A 10 μl portion of lysate was analyzed for Renilla and firefly luciferase activity using the Dual-Luciferase Assay System (Promega) on a TD-20/20 Turner Designs luminometer. Mean values and standard deviation were determined for each experimental point, with the ratio of firefly to Renilla luciferase normalized to 1.0 for the MS2 protein. MS2 fusion protein expression was comparable as assessed by Western blot (MS2 antibodies generously provided by Mike Kiledjian).

Oocyte isolation, culture, microinjection and lysate preparation

Xenopus oocyte isolation and culture has been described (Machaca and Haun, 2002). Where indicated, oocytes were pretreated with 50 μM U0126 (Promega) and 0.5% DMSO for 1 h before stimulation. Oocytes were induced to mature with 2 μg/ml progesterone, cyclin B protein (Howard et al, 1999) or by injection of approximately 0.04 U of recombinant rabbit PKI-α (Calbiochem). GVBD was used as an indicator of maturation and assessed by the presence of a white spot on the animal pole. Where indicated, oocytes were segregated at the time when 50% of the oocyte population had reached GVBD (GVBD50) based on whether they had (+) or had not (−) completed GVBD. A 250 ng portion of RNA encoding GST N-Msi or GST N-Msi-bm was injected per oocyte and left for 36 h for protein expression and equilibration with endogenous Musashi. The oocyte culture medium was changed after about 18 h. RNA and protein were extracted from the same pool of oocytes as previously described (Charlesworth et al, 2002). MPF activation was assessed using phospho-CDK1/CDK2 antisera (Cell Signaling). MAP kinase activation as well as Mos and GST protein accumulation was assessed as previously described (Howard et al, 1999).

Polyadenylation assays

RNA ligation-coupled RT–PCR was performed as described previously (Charlesworth et al, 2004). To analyze polyadenylation of reporter constructs, primers to the GST region were used (Charlesworth et al, 2004). The primers used to analyze the novel mRNAs are described in Supplementary data.

mRNA co-association assay

A 25 ng portion of RNA encoding the indicated GST fusion protein was injected into immature oocytes and cultured for 24 h to allow GST fusion protein expression. Pools of 25 oocytes were lysed in 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% NP-40, 6 mM DTT, protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma), PMSF, 10 mM ribonucleoside vanadyl complex (NEB) and 400 U/ml RNase OUT (Invitrogen) and centrifuged to remove cell debris. GST-tagged proteins were affinity purified with glutathione Sepharose for 30 min and washed 5 × 1 ml with the same buffer. RNA was extracted using STAT-60 and analyzed by RNA ligation-coupled RT–PCR.

GST reporter mRNA translation assays

Analyses of wild-type and mutant 3′ UTRs on GST reporter mRNA translation were performed using 0.2 ng reporter RNA as previously described (Charlesworth et al, 2000, 2002).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data

Supplementary Table 1

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Marv Wickens for providing the yeast strains and the empty and control plasmids for the three-hybrid screen; Niki Gray for the MS2 fusion expression plasmid and plasmids encoding firefly luciferase reporter mRNAs; and Nancy Standart for the plasmid encoding the Renilla luciferase reporter mRNA. We thank Melanie MacNicol for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (HD35688) to AMM.

References

- Ballantyne S, Daniel DL, Wickens M (1997) A dependent pathway of cytoplasmic polyadenylation reactions linked to cell cycle control by c-mos and Cdk1 activation. Mol Biol Cell 8: 1633–1648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battelli C, Nikopoulos GN, Mitchell JG, Verdi JM (2006) The RNA-binding protein Musashi-1 regulates neural development through the translational repression of p21(WAF-1). Mol Cell Neurosci 31: 85–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DS, Buter N, Stumpf C, Wickens M (2002) Analyzing mRNA–protein complexes using a yeast three-hybrid system. Methods 26: 123–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlesworth A, Cox LL, MacNicol AM (2004) Cytoplasmic polyadenylation element (CPE)- and CPE-binding protein (CPEB)-independent mechanisms regulate early class maternal mRNA translational activation in Xenopus oocytes. J Biol Chem 279: 17650–17659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlesworth A, Ridge JA, King LA, MacNicol MC, MacNicol AM (2002) A novel regulatory element determines the timing of Mos mRNA translation during Xenopus oocyte maturation. EMBO J 21: 2798–2806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlesworth A, Welk J, MacNicol A (2000) The temporal control of Wee1 mRNA translation during Xenopus oocyte maturation is regulated by cytoplasmic polyadenylation elements within the 3′ untranslated region. Dev Biol 227: 706–719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colegrove-Otero LJ, Minshall N, Standart N (2005) RNA-binding proteins in early development. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol 40: 21–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collier B, Gorgoni B, Loveridge C, Cooke HJ, Gray NK (2005) The DAZL family proteins are PABP-binding proteins that regulate translation in germ cells. EMBO J 24: 2656–2666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daar I, Yew N, Vande Woude GF (1993) Inhibition of mos-induced oocyte maturation by protein kinase A. J Cell Biol 120: 1197–1202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson EH (1986) Gene Activity in Early Development. London: Academic Press [Google Scholar]

- de Moor CH, Meijer H, Lissenden S (2005) Mechanisms of translational control by the 3′ UTR in development and differentiation. Semin Cell Dev Biol 16: 49–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Moor CH, Richter JD (1997) The Mos pathway regulates cytoplasmic polyadenylation in Xenopus oocytes. Mol Cell Biol 17: 6419–6426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupre A, Jessus C, Ozon R, Haccard O (2002) Mos is not required for the initiation of meiotic maturation in Xenopus oocytes. EMBO J 21: 4026–4036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox CA, Sheets MD, Wickens MP (1989) Poly(A) addition during maturation of frog oocytes: distinct nuclear and cytoplasmic activities and regulation by the sequence UUUUUAU. Genes Dev 3: 2151–2162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman RS, Ballantyne SM, Donoghue DJ (1991) Meiotic induction by Xenopus cyclin B is accelerated by coexpression with mosXe. Mol Cell Biol 11: 1713–1717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuno N, Nishizawa M, Okazaki K, Tanaka H, Iwashita J, Nakajo N, Ogawa Y, Sagata N (1994) Suppression of DNA replication via Mos function during meiotic divisions in Xenopus oocytes. EMBO J 13: 2399–2410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Good P, Yoda A, Sakakibara S, Yamamoto A, Imai T, Sawa H, Ikeuchi T, Tsuji S, Satoh H, Okano H (1998) The human Musashi homolog 1 (MSI1) gene encoding the homologue of Musashi/Nrp-1, a neural RNA-binding protein putatively expressed in CNS stem cells and neural progenitor cells. Genomics 52: 382–384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Good PJ, Rebbert ML, Dawid IB (1993) Three new members of the RNP protein family in Xenopus. Nucleic Acids Res 21: 999–1006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray NK, Coller JM, Dickson KS, Wickens M (2000) Multiple portions of poly(A)-binding protein stimulate translation in vivo. EMBO J 19: 4723–4733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross SD, Schwab MS, Taieb FE, Lewellyn AL, Qian YW, Maller JL (2000) The critical role of the MAP kinase pathway in meiosis II in Xenopus oocytes is mediated by p90(Rsk). Curr Biol 10: 430–438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemmati HD, Nakano I, Lazareff JA, Masterman-Smith M, Geschwind DH, Bronner-Fraser M, Kornblum HI (2003) Cancerous stem cells can arise from pediatric brain tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 15178–15183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard EL, Charlesworth A, Welk J, MacNicol AM (1999) The mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway stimulates mos mRNA cytoplasmic polyadenylation during Xenopus oocyte maturation. Mol Cell Biol 19: 1990–1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huchon D, Ozon R, Fischer EH, Demaille JG (1981) The pure inhibitor of cAMP-dependent protein kinase initiates Xenopus laevis meiotic maturation. A 4-step scheme for meiotic maturation. Mol Cell Endocrinol 22: 211–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai T, Tokunaga A, Yoshida T, Hashimoto M, Mikoshiba K, Weinmaster G, Nakafuku M, Okano H (2001) The neural RNA-binding protein Musashi1 translationally regulates mammalian numb gene expression by interacting with its mRNA. Mol Cell Biol 21: 3888–3900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanemura Y, Mori K, Sakakibara S, Fujikawa H, Hayashi H, Nakano A, Matsumoto T, Tamura K, Imai T, Ohnishi T, Fushiki S, Nakamura Y, Yamasaki M, Okano H, Arita N (2001) Musashi1, an evolutionarily conserved neural RNA-binding protein, is a versatile marker of human glioma cells in determining their cellular origin, malignancy, and proliferative activity. Differentiation 68: 141–152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi H, Minshull J, Ford C, Golsteyn R, Poon R, Hunt T (1991) On the synthesis and destruction of A- and B-type cyclins during oogenesis and meiotic maturation in Xenopus laevis. J Cell Biol 114: 755–765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuersten S, Goodwin EB (2003) The power of the 3′ UTR: translational control and development. Nat Rev Genet 4: 626–637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovell MA, Markesbery WR (2005) Ectopic expression of Musashi-1 in Alzheimer disease and Pick disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 64: 675–680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machaca K, Haun S (2002) Induction of maturation-promoting factor during Xenopus oocyte maturation uncouples Ca(2+) store depletion from store-operated Ca(2+) entry. J Cell Biol 156: 75–85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matten WT, Copeland TD, Ahn NG, Vande Woude GF (1996) Positive feedback between MAP kinase and Mos during Xenopus oocyte maturation. Dev Biol 179: 485–492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez R, Barnard D, Richter JD (2002) Differential mRNA translation and meiotic progression require Cdc2-mediated CPEB destruction. EMBO J 21: 1833–1844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mignone F, Grillo G, Licciulli F, Iacono M, Liuni S, Kersey PJ, Duarte J, Saccone C, Pesole G (2005) UTRdb and UTRsite: a collection of sequences and regulatory motifs of the untranslated regions of eukaryotic mRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res 33: D141–D146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minshall N, Thom G, Standart N (2001) A conserved role of a DEAD box helicase in mRNA masking. RNA 7: 1728–1742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami MS, Vande Woude GF (1998) Analysis of the early embryonic cell cycles of Xenopus; regulation of cell cycle length by Xe-wee1 and Mos. Development 125: 237–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajo N, Yoshitome S, Iwashita J, Iida M, Uto K, Ueno S, Okamoto K, Sagata N (2000) Absence of wee1 ensures the meiotic cell cycle in Xenopus oocytes. Genes Dev 14: 328–338 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okabe M, Imai T, Kurusu M, Hiromi Y, Okano H (2001) Translational repression determines a neuronal potential in Drosophila asymmetric cell division. Nature 411: 94–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okano H, Imai T, Okabe M (2002) Musashi: a translational regulator of cell fate. J Cell Sci 115: 1355–1359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okano H, Kawahara H, Toriya M, Nakao K, Shibata S, Imai T (2005) Function of RNA-binding protein Musashi-1 in stem cells. Exp Cell Res 306: 349–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paris J, Swenson K, Piwnica WH, Richter JD (1991) Maturation-specific polyadenylation: in vitro activation by p34cdc2 and phosphorylation of a 58-kD CPE-binding protein. Genes Dev 5: 1697–1708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potten CS, Booth C, Tudor GL, Booth D, Brady G, Hurley P, Ashton G, Clarke R, Sakakibara S, Okano H (2003) Identification of a putative intestinal stem cell and early lineage marker; musashi-1. Differentiation 71: 28–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian YW, Erikson E, Taieb FE, Maller JL (2001) The polo-like kinase Plx1 is required for activation of the phosphatase Cdc25C and cyclin B–dc2 in Xenopus oocytes. Mol Biol Cell 12: 1791–1799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy LM, Haccard O, Izumi T, Lattes BG, Lewellyn AL, Maller JL (1996) Mos proto-oncogene function during oocyte maturation in Xenopus. Oncogene 12: 2203–2211 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagata N, Daar I, Oskarsson M, Showalter SD, Vande Woude GF (1989) The product of the mos proto-oncogene as a candidate initiator for oocyte maturation. Science 245: 643–646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagata N, Oskarsson M, Copeland T, Brumbaugh J, Vande Woude GF (1988) Function of c-mos proto-oncogene product in meiotic maturation in Xenopus oocytes. Nature 335: 519–525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SenGupta DJ, Wickens M, Fields S (1999) Identification of RNAs that bind to a specific protein using the yeast three-hybrid system. RNA 5: 596–601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SenGupta DJ, Zhang B, Kraemer B, Pochart P, Fields S, Wickens M (1996) A three-hybrid system to detect RNA–rotein interactions in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93: 8496–8501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheets MD, Fox CA, Hunt T, Vande Woude G, Wickens M (1994) The 3′-untranslated regions of c-mos and cyclin mRNAs stimulate translation by regulating cytoplasmic polyadenylation. Genes Dev 8: 926–938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheets MD, Wu M, Wickens M (1995) Polyadenylation of c-mos mRNA as a control point in Xenopus meiotic maturation. Nature 374: 511–516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith LD (1989) The induction of oocyte maturation: transmembrane signaling events and regulation of the cell cycle. Development 107: 685–699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toda M, Iizuka Y, Yu W, Imai T, Ikeda E, Yoshida K, Kawase T, Kawakami Y, Okano H, Uyemura K (2001) Expression of the neural RNA-binding protein Musashi1 in human gliomas. Glia 34: 1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Liu XJ (2004) Progesterone inhibits protein kinase A (PKA) in Xenopus oocytes: demonstration of endogenous PKA activities using an expressed substrate. J Cell Sci 117: 5107–5116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkie GS, Dickson KS, Gray NK (2003) Regulation of mRNA translation by 5′- and 3′-UTR-binding factors. Trends Biochem Sci 28: 182–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokota N, Mainprize TG, Taylor MD, Kohata T, Loreto M, Ueda S, Dura W, Grajkowska W, Kuo JS, Rutka JT (2004) Identification of differentially expressed and developmentally regulated genes in medulloblastoma using suppression subtraction hybridization. Oncogene 23: 3444–3453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B, Kraemer B, SenGupta D, Fields S, Wickens M (1999) Yeast three-hybrid system to detect and analyze interactions between RNA and protein. Methods Enzymol 306: 93–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary data

Supplementary Table 1