Abstract

Summary Background Data:

Axillary dissection, an invasive procedure that may adversely affect quality of life, used to obtain prognostic information in breast cancer, is being supplanted by sentinel node biopsy. In older women with early breast cancer and no palpable axillary nodes, it may be safe to give no axillary treatment. We addressed this issue in a randomized trial comparing axillary dissection with no axillary dissection in older patients with T1N0 breast cancer.

Methods:

From 1996 to 2000, 219 women, 65 to 80 years of age, with early breast cancer and clinically negative axillary nodes were randomized to conservative breast surgery with or without axillary dissection. Tamoxifen was prescribed to all patients for 5 years. The primary endpoints were axillary events in the no axillary dissection arm, comparison of overall mortality (by log rank test), breast cancer mortality, and breast events (by Gray test).

Results:

Considering a follow-up of 60 months, there were no significant differences in overall or breast cancer mortality, or crude cumulative incidence of breast events, between the 2 groups. Only 2 patients in the no axillary dissection arm (8 and 40 months after surgery) developed overt axillary involvement during follow-up.

Conclusions:

Older patients with T1N0 breast cancer can be treated by conservative breast surgery and no axillary dissection without adversely affecting breast cancer mortality or overall survival. The very low cumulative incidence of axillary events suggests that even sentinel node biopsy is unnecessary in these patients. Axillary dissection should be reserved for the small proportion of patients who later develop overt axillary disease.

Reported is a 5-year outcomes in 219 older women with early breast cancer and clinically negative axillary nodes, treated by quadrantectomy and tamoxifen, and prospectively randomized to axillary dissection or not. Breast cancer mortality and overall survival did not differ between arms; axillary dissection can thus be avoided in such patients.

For many years, axillary dissection was part of the standard treatment of breast cancer following the pioneering studies by Halsted, early in the 20th century, which indicated that surgical clearance of the axilla resulted in better locoregional control and improved overall survival for the disease.1 Fisher et al2 were the first to publish data supporting the hypothesis that the resection of metastatic axillary nodes does not have a controlling influence on survival but may provide an indication of possible metastatic spread. Subsequent studies supported this hypothesis.3 Axillary dissection and more recently sentinel node biopsy4 are still considered important, not as treatments for breast cancer, but as a means of obtaining prognostic information for planning postsurgical systemic therapy.

The affirmation of mammographic screening, resulting in increased detection of T1 cancers and a decrease in the proportion of cases with axillary lymph node involvement,5 strengthened the idea that axillary surgery may be safety omitted in most patients with early breast cancer. Furthermore, the prognostic role of axillary dissection is considered to have been superseded by biologic profiling of the primary tumor,6–8 which provides sufficiently reliable information for deciding if and what systemic treatments are necessary.

In the elderly, the role of axillary dissection remains controversial, mainly because of a lack of data: high mortality for competing events, shorter life expectancy, and high response rate to hormone therapy have made it difficult to conduct appropriately powered randomized studies. Our previous prospective nonrandomized trial9 provided evidence that elderly patients with early stage breast cancer and no clinically evident axillary involvement can be effectively treated by quadrantectomy alone and tamoxifen: we found very low rates of locoregional failure in patients so treated, and no adverse effect on breast cancer mortality or overall survival.

The present paper reports the results of a prospective randomized clinical trial on older patients with early stage breast cancer and clinically negative axillary nodes. Because of difficulties in recruiting older patients to clinical trials, we decided to randomize all eligible patients who consented to take part in the study over a 5-year study period. The main aim was to determine whether, in patients who received conservative breast surgery plus tamoxifen only, outcomes differed from those who also received axillary dissection. An additional aim was to estimate the incidence of axillary relapse in patients treated with surgery without axillary clearance.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Eligibility and Randomization

Between January 1996 and May 2000, we recruited women with operable primary invasive breast cancer not exceeding 2 cm in mammographic diameter, a clinically negative axilla, and age 65 to 80 years. Patients with synchronous bilateral breast carcinoma, distant metastases at diagnosis, or history of malignancy at another site (except basal cell carcinoma and intraepithelial cervical neoplasia) were excluded. The study was approved by our institute's scientific and ethical committees, and written informed consent was obtained from all patients. The women were randomized by calling the data manager at the study coordination center. After the inclusion and exclusion criteria had been checked, eligible women were assigned to axillary dissection or no axillary treatment using a randomization list.

A total of 238 patients were randomized. However, 5 of these were ineligible and should not have been recruited; in addition, there were protocol violations in a further 14 patients. These 19 patients were excluded from the analysis, which was performed on 219 patients (109 in the axillary dissection group and 110 in the no axillary dissection group).

Treatment

Quadrantectomy with axillary dissection was performed under general anesthesia; quadrantectomy alone was generally performed under local anesthesia. Quadrantectomy is an extensive excision that removed at least 2 cm of normal breast tissue around the tumor plus the corresponding portion of overlying skin. In upper-outer quadrantectomy, axillary lymph nodes are never removed. In all cases, the margins of the resected specimen were free of involvement on pathologic examination.

Postoperative radiotherapy to the residual breast was initiated within 4 weeks of surgery. Axillary, supraclavicular, and internal mammary nodes were not irradiated. A cobalt-60 unit or 6 MeV linear electron accelerator was used to deliver 50 Gray (Gy) to the operated breast in 2 opposing tangential fields over 5 weeks. A supplemental boost of 10 Gy was given to the tumor bed. Although postoperative breast radiotherapy did not specifically irradiate the axilla, the tangential portals used typically included the lower part of level I of the axilla.

Regardless of hormone receptor status, all women were prescribed 10 mg tamoxifen twice daily from surgery for 5 consecutive years.

Histologic Grade and Hormone Receptor Status

Histologic grade was assessed according to Elston and Ellis.10 Hormone receptors were determined on representative 2-μm-thick, formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded sections by immunoperoxidase phenotyping. Prior to incubation with primary antibodies (Abs), the sections, in 0.005 mL/L citrate buffer, pH 6, were heated at 95°C for 6 minutes in an autoclave. The primary Abs were mouse monoclonal against estrogen receptor (DAKO, clone 1D5, diluted 1:100) and mouse monoclonal against progesterone receptor (DAKO, clone 636, diluted 1:100). Diaminobenzidine was used as chromogen. Positive and negative controls were examined concurrently; for negative controls, primary Ab was omitted. Receptor status was considered positive if more than 10% of the tumor cell nuclei were immunostained.

Follow-up

Patients were followed at our outpatient department, with checks programmed every 4 months in the first 3 years, every 6 months in the 2 subsequent years, and annually thereafter. Because all patients received tamoxifen, twice-yearly gynecological examinations were also programmed, with colposcopy and pelvic ultrasonography via transvaginal probe. Endometrial samples were always taken if the endometrial rima exceeded 10 mm in thickness. Mammography and chest x-ray were performed yearly and bone scans every 2 years.

Statistical Methods

The 95% confidence interval (CI) for axillary relapse rate in the no axillary dissection arm was estimated by an exact method based on the Poisson distribution.11 To compare the 2 surgical treatments, the following endpoints were considered: overall mortality, breast cancer mortality, and breast events (ipsilateral breast tumor recurrence [IBTR], contralateral breast cancer, and distant metastases).

Events were calculated from the date of randomization to the date of first unfavorable breast event or date of last clinical contact in the event of death.

Median follow-up was 60 months (range, 50–88 months) in the axillary dissection group and 62 months (range, 52–89 months) in the no axillary dissection group. We decided to perform the analysis at 5 years of follow-up when 80% of patients were still in observation.

Curves for overall survival (defined from time of randomization, a short time before surgery, to death for any cause) were estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method and compared using the log rank test.

Crude cumulative incidence curves for breast cancer mortality and breast events were obtained taking account of competing effects of deaths from second primary malignancies and noncancer causes.12 Gray's test13 was used to compare the incidence curves in the 2 groups. The incidence probabilities over 5 years for each breast cancer event, for breast cancer mortality, second primary malignancy, and mortality from noncancer causes were calculated from the corresponding crude cumulative incidence curves.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

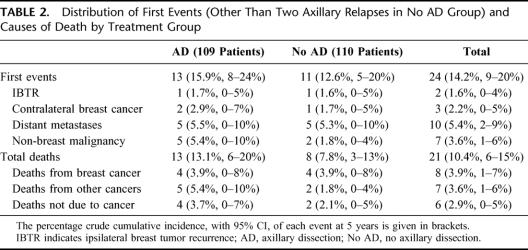

Patient characteristics according to treatment group are shown in Table 1. Median age was 70 years (range, 65–80 years). In 8 patients in each group, pathologic evaluation showed the tumor to be T2. Ninety-one percent of patients had G1 or G2 tumors. Most patients were ER positive, PgR positive, or both: 25 (12%) cases were both ER and PgR negative. Eleven patients (5%) had an unfavorable prognostic profile defined as ER negative, PgR negative, and G3.

TABLE 1. Patient Characteristics

Twenty-three percent of the 109 patients who received axillary dissection had metastatic axillary lymph nodes; of these, 72% had one positive axillary node and 24% had more than 3 positive nodes.

Because of side effect (usually hot flashes, nausea, and gastrointestinal distress), 33 (15%) of patients took tamoxifen discontinuously. Four patients stopped tamoxifen definitively following thromboembolic events in superficial or deep veins of the lower limbs.

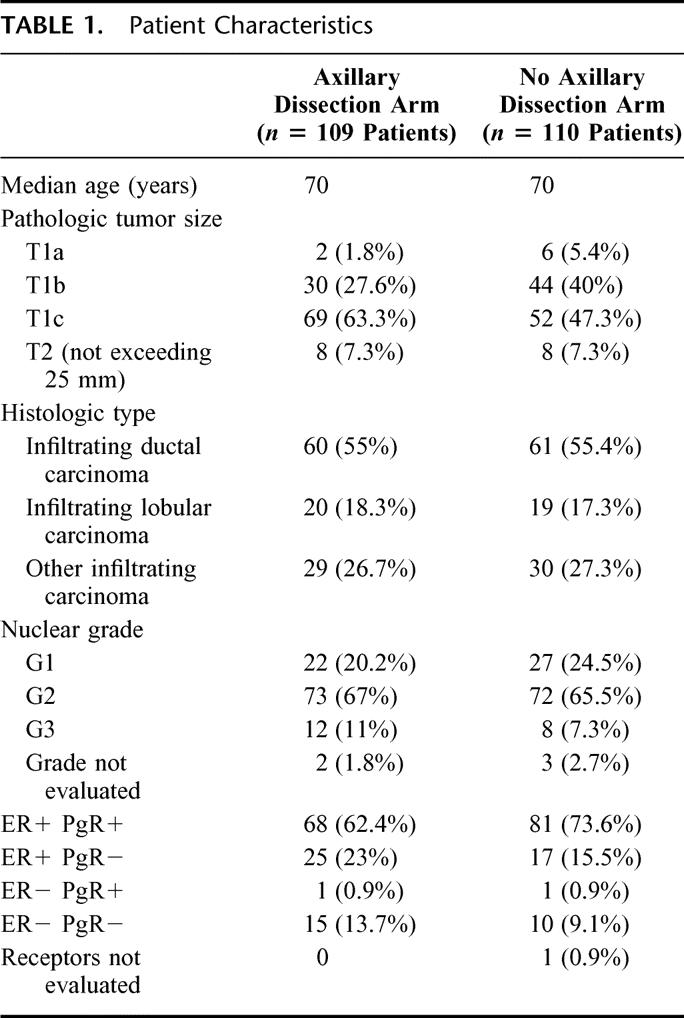

Site of First Recurrence

First events and causes of death are shown in Table 2. Two patients (1.8%) (95% CI, 0–7) in the no axillary dissection arm developed overt ipsilateral axillary disease, 8 and 40 months after surgery. The corresponding ipsilateral axillary disease rate was 0 to 0.013 events per women per year (0.013=7/544, where 544 is the total time in months of exposure to risk). Both patients received complete axillary dissection; 1 developed distant metastases and died of her disease.

TABLE 2. Distribution of First Events (Other Than Two Axillary Relapses in No AD Group) and Causes of Death by Treatment Group

Two patients, one in each arm, developed IBTR, in each case rescued by wide resection; both patients were disease-free at latest check-up. The probability of IBTR was 1.7% over 5 years in the axillary dissection arm and 1.6% in the no axillary dissection arm.

Five patients in each arm developed distant metastases; the probabilities of distant metastases of 5 years were 5.5% in the axillary dissection arm and 5.3% in the no axillary dissection arm. All patients with distant metastases received second-line hormone treatment. Sixty percent of distant metastases were in bone, and radiotherapy was administered to prevent pathologic bone fractures.

There were 5 new nonbreast malignancies as first events in the axillary dissection arm (3 gastrointestinal cancers, 2 lung cancers) and 2 in the no axillary dissection arm (both gastrointestinal cancers). No patient developed endometrial cancer. Mortality from nonbreast cancer was higher in the axillary dissection arm than in the no axillary dissection arm (incidence probabilities over 5 years: 5.4% and 1.8%, respectively). Mortality from all noncancer causes was also higher in the axillary dissection arm than in the no axillary dissection arm (incidence probabilities over 5 years: 3.7% and 2.1%, respectively). Cardiovascular or cerebrovascular events accounted for most noncancer deaths, although no patient died of thromboembolic complications.

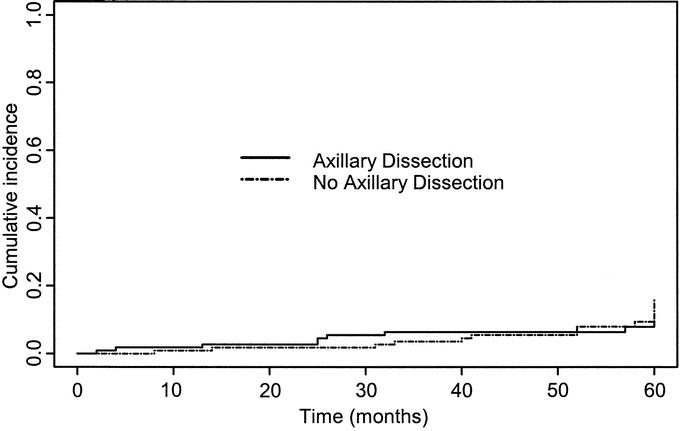

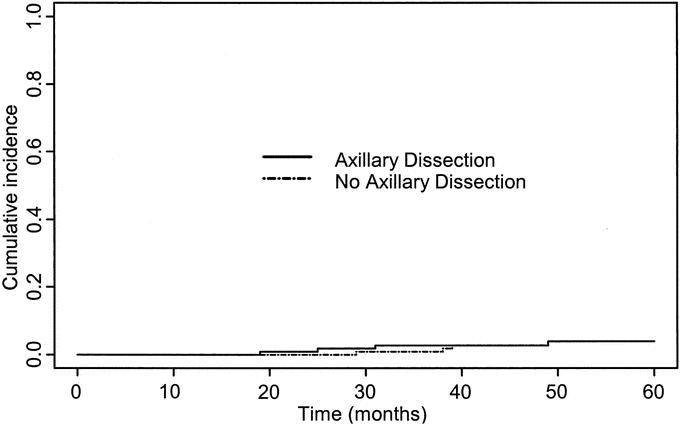

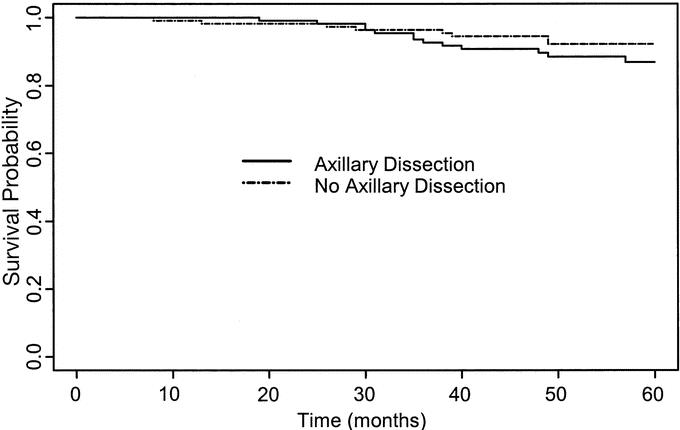

The probability of breast cancer death over 5 years was closely similar in the 2 arms (3.95% in the axillary dissection arm and 3.93% for the no axillary dissection arm). There was no significant difference between the 2 arms for cumulative incidence of breast events (Gray's test: χ2 0.58; P = 0.45) (Fig. 1). Similarly, there were no significant differences between the 2 groups in terms of crude cumulative incidence of breast carcinoma mortality (Gray's test: χ2 = 0.001; P =0.97) (Fig. 2) or overall survival (log rank test: χ2 = 1.23; P =0.25) (Fig. 3). The estimated difference in breast cancer mortality between the 2 arms was insignificant (0.2%; 95% CI, −5.4% to 5.4%). The estimated difference in overall mortality between the 2 arms was 5.3% in favor of the no axillary dissection arm (95% CI, −3.3% to 13.9%).

FIGURE 1. Crude cumulative incidence curves of breast events in two treatment groups.

FIGURE 2. Crude cumulative incidence curves of breast cancer mortality in the two treatment groups.

FIGURE 3. Overall survival curves in the two treatment groups.

Among the 27 patients with ER-negative cancers, there were 6 (22%) first events and 4 (14.8%) deaths from breast cancer; these percentages are considerably higher than the corresponding 4.7% first events and 2% breast cancer deaths among the 191 patients who were ER positive. Among the 20 patients with G3 tumors, there were 3 (15%) breast events and 1 (5%) breast cancer death compared with 12 (6.2%) breast cancer events and 7 (3.6%) breast cancer deaths among the 194 patients with G1 or G2 tumors. Of the 11 patients with an unfavorable biologic profile (ER negative, PgR negative, and G3), 1 developed distant metastases and died of her disease, 1 developed a local relapse, and 1 developed contralateral breast cancer (both treated by wide resection).

DISCUSSION

We found no significant differences in breast cancer mortality, crude cumulative incidence of breast events, or overall survival between the 2 treatment groups. Equally important was our finding that only 2 patients (1.8%) of the 110 in the no axillary dissection arm developed axillary relapse during a median follow-up of 60 months and required delayed axillary dissection.

These findings are in full accord with those of our recently published nonrandomized trial,9 which found no advantage, in terms of overall survival or breast cancer mortality, for axillary dissection after quadrantectomy and tamoxifen in elderly patients with early stage breast cancer and clinically negative nodes.

Fisher et al14 were the first to show that axillary dissection had no significant effect on overall survival and distant recurrence-free survival in a large series of women of all ages who received radical mastectomy or total mastectomy without axillary dissection. Furthermore, while about 40% of the patients who did not receive axillary dissection were expected to have axillary node metastases, over 25 years of follow-up only 18% subsequently developed overt axillary disease.

Zurrida et al15 also reported a very low rate of axillary recurrence in clinically node-negative breast cancer patients treated with breast-conserving surgery without axillary dissection in tumors up to 1.2 cm. Only 0.5% of patients in the no axillary dissection arm required delayed axillary dissection for the development of clinically positive nodes over a median follow-up of 42 months.

In the present study, 23% of patients who received axillary dissection had metastatic axillary lymph nodes on pathologic examination, all of whom were node negative on clinical examination. We expected that a similar percentage in the no axillary dissection arm would develop axillary metastases during follow-up. However, only 1.8% of patients required delayed axillary dissection for overt axillary disease. These findings suggest that not all metastases in the axilla will become biologically active.

Some studies16,17 suggest better local control in the axilla if, in absence of axillary dissection, postoperative breast irradiation is administered, since tangential radiotherapy to the whole breast generally also irradiates the lower part of the axilla. However, a recent prospective Italian study18 showed that the first axillary level does not receive a therapeutic dose when the treatment plan aims to irradiate the residual breast only. Furthermore, in our previous prospective nonrandomized study19 on 321 consecutive elderly breast cancer patients who underwent conservative surgery without axillary dissection and without postoperative radiotherapy (all of whom received adjuvant tamoxifen), the axillary recurrence rate was still low (4%) after a median follow-up of 72 months. We therefore think that the contribution of tangential breast radiotherapy in reducing axillary relapse in older breast cancer patients not subjected to axillary clearance is minimal.

By contrast, there is good evidence that prolonged administration of tamoxifen extends time to treatment failure by many years, particularly in patients whose cancers express high levels of estrogen receptor.20,21 We suggest that one reason for the low rate of overt axillary disease (and indeed of treatment failure in general) in our series is that all were prescribed tamoxifen.

Well-known severe complications of tamoxifen use are thromboembolic events and endometrial cancer.22,23 In the present study, no patient developed endometrial cancer after a follow-up of 60 months. However, 4 patients had thromboembolic events (superficial thrombophlebitis in 2, deep venous thrombosis in 1, and pulmonary embolism secondary to thrombophlebitis in another). No patient died of thromboembolic complications. Results of the recent ATAC trial24 suggest that new generation aromatase inhibitors may be superior to tamoxifen, not only in terms of breast cancer outcomes but also in terms of reduced risk of thromboembolic events.

We did not perform a statistical analysis of breast events in relation to tumor grade and receptor status because there were too few patients in some of the categories. However, our numerical data suggest that patients with ER-negative tumors had more unfavorable events (mainly distant metastases) and higher breast cancer mortality than ER-positive patients, whereas those with high grade tumors had more unfavorable locoregional events than those with lower grade tumors with no adverse affect on breast cancer mortality.

Although our study was not designed to address the use of sentinel node biopsy in older women with breast cancer, we think that the very low cumulative incidence of overt axillary disease in the no axillary dissection arm after 5 years of follow-up indicates that there is no need for any intervention, not even minimally invasive sentinel node biopsy25 to a clinically uninvolved axilla in these women.

We also suggest that the remarkably low rate of local relapses in our series bears upon the question as to whether postoperative radiotherapy to the residual breast is really necessary in older patients with small cancers. Our prospective nonrandomized study9 and the Veronesi et al26 randomized trial, which specifically addressed the issue of radiotherapy, also showed satisfactorily low rates of local relapse in older patients with T1 breast cancer treated by conservative surgery (quadrantectomy) without radiotherapy, in all cases followed by adjuvant tamoxifen. Similarly, the study of Gruenberger et al27 showed no difference in local relapse rate in older breast cancer patients treated by conservative surgery with or without radiotherapy. Two ongoing randomized trials28,29 are expected to resolve this issue definitively.

CONCLUSION

The results of this study show that axillary dissection may be safety omitted in older patients with early stage breast cancer and no palpable axillary nodes since its omission has no discernible effect on breast cancer mortality or overall survival. Axillary dissection should be reserved for the small proportion of patients who later develop overt axillary disease. Even sentinel lymph node biopsy seems unnecessary in view of the very low cumulative incidence of axillary relapse in the patients without axillary clearance in our study. This conservative therapeutic strategy has the additional merit of sparing older women the complications of axillary dissection (lymphedema and impaired shoulder function), thereby ensuring a consistent positive impact on quality of life.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Nadia Crose for database management and Don Ward for help with the English.

Footnotes

Supported by the Italian Association for Cancer Research (AIRC).

Reprints: Gabriele Martelli, MD, Unit of Diagnostic Oncology and Out-Patient Clinic, Istituto Nazionale Tumori, Via Venezian 1, 20133 Milan, Italy. E-mail: gabriele.martelli@istitutotumori.mi.it.

REFERENCES

- 1.Halsted WS. The results of radical operations for the cure of cancer of the breast. Ann Surg. 1907;46:1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fisher B, Redmond C, Fisher ER, et al. Ten-year results of a randomized clinical trial comparing radical mastectomy and total mastectomy with or without radiation. N Engl J Med. 1985;312:674–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gervasoni JE Jr, Taneja C, Chung MA, et al. Axillary dissection in the context of the biology of lymph node metastases. Am J Surg. 2000;180:278–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Veronesi U, Paganelli G, Viale G, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy and axillary dissection in breast cancer: results in a large series. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:368–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tabar L, Smith RA, Vitak B, et al. Mammographic screening: a key factor in the control of breast cancer. Cancer J. 2003;9:15–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Menard S, Bufalino R, Rilke F, et al. Prognosis based on primary breast carcinoma instead of pathological nodal status. Br J Cancer. 1994;70:709–712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Laurentiis M, Gallo C, De Placido S, et al. A predictive index of axillary nodal involvement in operable breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 1996;73:1241–1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ravdin PM, De Laurentiis M, Vendely T, et al. Prediction of axillary lymph node status in breast cancer patients by use of prognostic indicators. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1994;86:1171–1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martelli G, Miceli R, De Palo G, et al. Is axillary dissection necessary in elderly patients with breast carcinoma who have a clinically uninvolved axilla? Cancer. 2003;97:1156–1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elston CW, Ellis IO. Pathological prognostic factors in breast cancer: I. The value of histological grade in breast cancer: experience from a large study with long-term follow-up. Histopathology. 1991;19:403–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cytel Software Corporation. StatXact5-User Manual, Release 5. 0.2, Part III: Inference for Categorical Data. 2001:431–445.

- 12.Marubini E, Valsecchi MG. Analysing Survival Data From Clinical Trials and Observational Studies. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gray RJ. A class of K-sample tests for comparing the cumulative incidence of a competing risk. Ann Stat. 1988;16:1140–1154. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fisher B, Jeong JH, Anderson S, et al. Twenty-five-year follow-up of a randomized trial comparing radical mastectomy, total mastectomy, and total mastectomy followed by irradiation. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:567–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zurrida S, Orecchia R, Galimberti V, et al. Axillary radiotherapy instead of axillary dissection: a randomized trial. Ann Surg Oncol. 2002;9:156–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wong JS, Recht A, Beard CJ, et al. Treatment outcome after tangential radiation therapy without axillary dissection in patients with early-stage breast cancer and clinically-negative axillary nodes. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1997;39:915–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuznetsova M, Graybill JC, Zusag TW, et al. Omission of axillary lymph node dissection in early-stage breast cancer: effect on treatment outcome. Radiology. 1995;197:507–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aristei C, Chionne F, Marsella AR, et al. Evaluation of level I and II axillary nodes included in the standard breast tangential field and calculation of the administered dose: results of a prospective study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001;51:69–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martelli G, De Palo G, Rossi N, et al. Long-term follow-up of elderly patients with operable breast cancer treated with surgery without axillary dissection plus adjuvant tamoxifen. Br J Cancer. 1995;72:1251–1255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cummings FJ, Gray R, Tormey DC, et al. Adjuvant tamoxifen versus placebo in elderly women with node-positive breast cancer: long-term follow-up and causes of death. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:29–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fisher B, Costantino J, Redmond C, et al. A randomized clinical trial evaluating tamoxifen in the treatment of patients with node-negative breast cancer who have estrogen-receptor-positive tumors. N Engl J Med. 1989;320:479–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saphner T, Tormey DC, Gray R. Venous and arterial thrombosis in patients who received adjuvant therapy for breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1991;9:286–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fisher B, Costantino JP, Redmond CK, et al. Endometrial cancer in tamoxifen-treated breast cancer patients: findings from the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP) B-14. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1994;86:527–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baum M, Buzdar A, Cuzick J, et al. Anastrozole alone or in combination with tamoxifen versus tamoxifen alone for adjuvant treatment of postmenopausal women with early-stage breast cancer: results of the ATAC trial efficacy and safety update analyses. Cancer. 2003;98:1802–1810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Veronesi U, Paganelli G, Viale G, et al. A randomized comparison of sentinel-node biopsy with routine axillary dissection in breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:546–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Veronesi U, Marubini E, Mariani L, et al. Radiotherapy after breast-conserving surgery in small breast carcinoma: long-term results of a randomized trial. Ann Oncol. 2001;12:997–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gruenberger T, Gorlitzer M, Soliman T, et al. It is possible to omit postoperative irradiation in a highly selected group of elderly breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1998;50:37–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hughes KS, Schnaper L, Berry D, et al. Comparison of lumpectomy plus tamoxifen with and without radiotherapy (RT) in women 70 years of age or older who have clinical stage I, estrogen receptor positive (ER+) breast carcinoma [Abstract]. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2001;20:93. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fyles A, McCready D, Manchul L, et al. Preliminary results of a randomized study of tamoxifen +/− breast irradiation in T1/2 N0 disease in women over 50 years of age [Abstract]. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2001;20:92. [Google Scholar]