Abstract

The mammalian protein PSF contains a DNA-binding domain (DBD) that coordinately represses multiple oncogenic genes in human cell lines, indicating a role for PSF as a human tumor-suppressor protein. PSF also contains two RNA-binding domains (RBD) that form a complex with a noncoding VL30 retroelement RNA, releasing PSF from a gene and reversing repression. Thus, the DBD and RBD in PSF are linked by a mechanism of reversible gene regulation involving a noncoding RNA. This mechanism also could apply to other regulatory proteins that contain both DBD and RBD. The mouse genome has multiple copies of VL30 retroelements that are developmentally regulated, and mouse cells contain VL30 RNAs that have normal and pathological roles in gene regulation. Human chromosome 11 has a VL30 retroelement, and a VL30 EST was identified in human blastocyst cells, indicating that the PSF-VL30 RNA regulatory mechanism also could function in human cells.

Keywords: retroelement RNA, tumor suppressor protein

PSF was originally identified as a protein component of spliceosomes, suggesting a role in RNA splicing mediated by the RNA-binding domains (RBD) of the molecule (1). It was shown subsequently that the DNA-binding domain (DBD) of PSF binds to the regulatory region of the P450ssc gene, which initiates the steroidogenic pathway, repressing transcription of the gene and suppressing steroidogenesis (2, 3). We reported that PSF also represses oncogenic genes (OG), and that retro-viral-mediated transfection of VL30 retroelement RNA into a human nonmetastatic tumor line formed a PSF-VL30 RNA complex that reversed repression by PSF and promoted metastasis (4, 5). This mechanism of reversible gene regulation appears to be involved in normal functions such as steroidogenesis and in pathological functions such as oncogenesis (5). Here, we analyze the role of the PSF DBD in tumor suppression and the roles of the PSF RBD and VL30 RNA in tumor promotion.

Materials and Methods

Cell Lines. The human melanoma cell lines Th, yusac, and A2058, breast cancer cell line MCF7, adrenal tumor line NCI-H295R, cervical carcinoma cell line HeLa, pancreatic cancer cell line colo357, and the normal fibroblast line BJ were maintained as described in ref. 5. The MCF7-PSF line was cloned from MCF7 transfected with a PSF expression plasmid (provided by R. J. Urban, University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, TX). The MCF7-DBD line was cloned from MCF7 transfected with plasmid encoding a fragment of the PSF gene from positions 1 to 994.

Microarray Analysis. RNA probes from MCF7 and MCF7-PSF cells were hybridized with the human HG-U133_Plus_2 Gene-Chip (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA) at the Yale W. M. Keck facility. The transcripts that showed at least a 4-fold increase or decrease of intensity in the MCF7-PSF cells relative to the MCF7 cells were analyzed by using netaffx, a web interface program from Affymetrix. Several of the microarray results were confirmed by semiquantitative RT-PCR assay.

Soft-Agar Colony Assay. MCF7 or MCF7-PSF cells (3 × 103) were suspended in 1 ml of 0.3% melted agar in MEM medium with 10% FBS and plated in 35-mm dishes containing a solidified layer of 0.5% agar in the same medium. After 3 weeks, 400 μl of PBS containing 0.5 mg of nitro blue tetrazolium was added to the dishes, and 1 day later, the colonies were scanned with an Epson Perfection 3200 scanner.

Semiquantitative RT-PCR. To detect the effect of PSF on GAGE6 expression in tumor lines, the cells were transiently transfected with a control plasmid pCDNA3.1 or the plasmid encoding PSF by using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). After 48 h, semiquantitative RT-PCR was performed as described in ref. 5. GAPDH mRNA was used to normalize the amounts of RNA in the samples. To detect the inhibitory effect of VL30 RNA on the binding of PSF to GAGE6 promoter DNA, the cells were transfected with a plasmid containing the 318-bp VL30 cDNA fragment that contains the pbt sequences that bind to PSF protein. After 48 h, semiquantitative RT-PCR was performed to detect the expression level of GAGE6 and PSF transcripts. GAGE6 primers, 5′-GCCTCCTGAAGTGATTGGGCCTA-3′ and 5′-CAGGCGTTTT CACCTCCTCTGGA-3′; PSF primers, 5′-ATGTCTCGGGATCGGTTCCGGA-3′ and 5′-CCAACAAACAACCGACATCGCTG-3′; and GAPDH primers, 5′-ACCACAGTCCAT GCCATCAC-3′ and 5′-TCCACCAC CCTGTTGCTGTA-3′.

Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assays (EMSA) and UV Cross-Linking. Fifty nanograms of recombinant PSF protein, DBD of PSF, RBD of PSF, or the nuclear lysates containing 2 μg of total protein were mixed with 5 ng of 32P-labeled RNA or DNA fragments. EMSA was performed as described in ref. 5.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) Assay. MCF7, MCF7-PSF, and MCF7-DBD cells were transfected with a plasmid encoding the 318-bp VL30 cDNA fragment, which contains the pbt sequences that bind to PSF protein. After 48 h, cells were cross-linked and processed for ChIP analyses by following the instruction of ChIP assay kit (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY). The polyclonal antibody for PSF, provided by J. Patton (Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN), was used to immunoprecipitate DNA. To analyze the PSF antibody-bound GAGE6 promoter DNA fragment, semiquantitative PCR was performed by using the following primers: GCCTTCTGCAAAGAAGTCTTGCGC and ATGCGAATTCGAGGCTGAGGCAGAC AAT.

Results

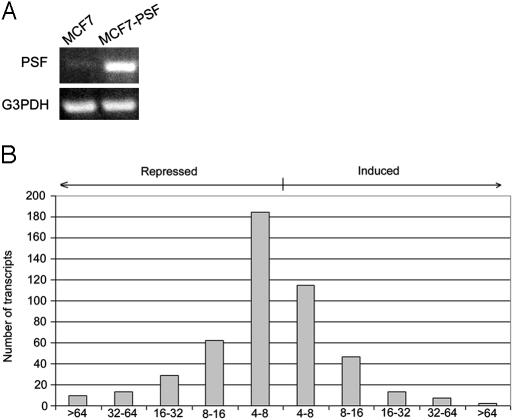

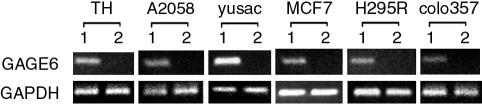

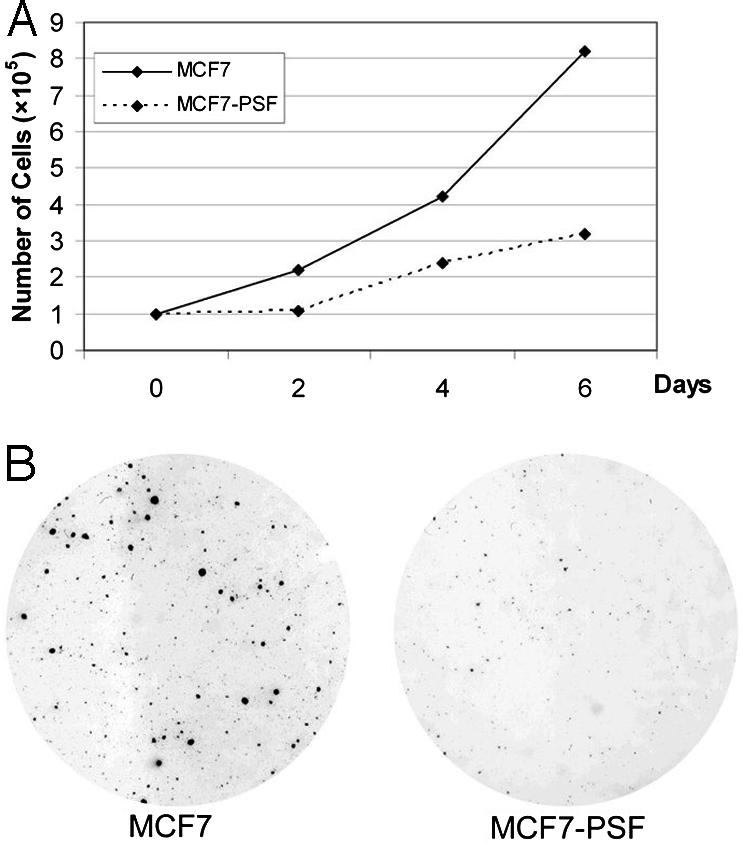

PSF-Mediated Repression of OG and Inhibition of Oncogenesis. The transcription patterns of the human breast tumor lines MCF7 that expresses a low level of PSF and MCF7-PSF that expresses a higher level of PSF, but otherwise are isogenic, were compared by microarray analyses (Fig. 1 A and B). The comparison identified 298 transcripts repressed by factors of 4-776 and 184 transcripts induced by factors of 4-147 in the MCF7-PSF line relative to the MCF7 line. Several of the microarray results were confirmed by semiquantitative RT-PCR. Most of the genes repressed by a factor of at least 32 (18 of 28) but none of the genes induced by a factor of at least 32 (0 of 14) have been characterized as OG (Table 1, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). Because PSF is known to function only as a repressor, induction could result from repression of genes that encode repressors of the induced genes. MCF7-PSF cells proliferated at a slower rate and produced fewer and smaller colonies in soft agar than MCF7 cells (Fig. 2 A and B), indicating that increased expression of PSF inhibits two basic properties of tumor cells, namely proliferation and colonization. PSF also represses the OG GAGE6 in several human tumor lines (Fig. 3). Thus, PSF appears to function as a human tumor-suppressor protein that coordinately represses transcription of multiple OG and inhibits oncogenesis.

Fig. 1.

Effect of PSF expression in MCF7 cells on gene transcription. (A) Transcription of PSF. The MCF7 (low PSF) and MCF7-PSF (high PSF) cells were assayed for PSF transcription by semiquantitative RT-PCR. (B) Microarray analysis. The transcription profiles of the MCF7 and MCF7-PSF cells were analyzed on Affymetrix microarray chips. Each bar in the figure indicates the number of transcripts repressed or induced in MCF7-PSF cells by a factor of 4-8, 8-16, 16-32, 32-64, and >64.

Fig. 2.

Effect of PSF expression in MCF7 cells on cell proliferation and colony formation. (A) Cell proliferation. Cells were grown in small flasks at 37°C as attached monolayers in MEM medium containing 10% FBS. Samples were recovered from three flasks every second day by treatment with trypsin, and the number of viable cells was counted. Each point is the average of three samples that agreed within ± 5%. (B) Colony formation. Single-cell suspensions were plated in soft agar, and the plates were incubated at 37°C for 19 days and photographed.

Fig. 3.

Effect of PSF on transcription of GAGE6 in human tumor lines. Each line was transiently transfected either with a control plasmid (lane 1) or with the same plasmid encoding PSF (lane 2). Semiquantitative RT-PCR assays were used to determine the transcription levels of GAGE6 and also of GAPDH to equalize the amount of mRNA in each pair. Cell lines: Th, A2058, and yusac are melanoma lines; MCF7 is a breast tumor line; H295R is an adrenal tumor line; and colo357 is a pancreatic tumor line.

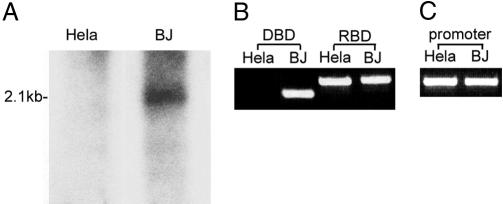

Tumor suppressor genes are frequently mutated in tumor cells, inactivating or deleting the encoded tumor suppressor protein (6). Human PSF is located on 1p34, a region frequently associated with loss of heterozygosity in human tumors (7). Among 10 tumor lines tested for deletions of the PSF gene, we found one line with a deletion of the PSF gene, the cervical tumor line HeLa showed a short deletion of the DBD that did not extend either to the PSF promoter at the 5′ end or the RBD at the 3′ end (Fig. 4 A and B). Another mutation of the PSF gene, which is frequently detected in human papillary renal cell carcinomas, involves a translocation that fuses part of the PSF gene with the TFE3 gene, inactivating the normal function of the PSF protein (8, 9).

Fig. 4.

A deletion in the PSF DBD region of the HeLa cell line. (A) Southern blot analysis. The genomic DNA isolated from HeLa (human cervical tumor) and BJ (human normal fibroblast) cell lines were hybridized with a 32P-labeled PSF DNA probe spanning positions -32 to +154 of the PSF gene. The same amount of genomic DNA was added to each lane. (B) RT-PCR analysis. DBD amd RBD of PSF transcripts were amplified by RT-PCR. (C) PCR analysis. Promoter region of PSF (-422 to -546) was amplified by PCR.

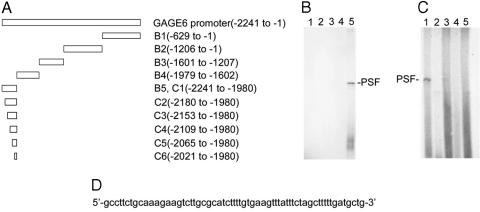

Mapping the Binding of PSF Protein to GAGE6 Promoter DNA. The PSF-regulated gene GAGE6 was used as a model human OG for the remaining experiments. The GAGE6 regulatory DNA probably maps in the 2,241 bp region located between the 5′ end of GAGE6-coding DNA and the 3′ end of the closest flanking gene. Enzymatic digestion of this DNA segment generated five DNA fragments (Fig. 5A). Each fragment was 32P-labeled, incubated with PSF protein, irradiated with UV, and analyzed by SDS/PAGE (Fig. 5B). The PSF protein bound only to the 262-bp fragment spanning positions -2241 to -1980. Finer mapping of this fragment localized the PSF binding site to a 61-bp region spanning positions -2241 to -2181 (Fig. 5 C and D).

Fig. 5.

Mapping the PSF-binding site in GAGE6. (A) Map of GAGE6 promoter fragments. The fragments were generated in the region -1to -2241 flanking the 5′ end of the GAGE6 coding region. (B and C) Binding of PSF to GAGE6 promoter fragments. 32P-labeled DNA fragments were mixed with PSF, irradiated with UV, and separated on 7.5% SDS/PAGE. (B) Lanes: 1 (-629 to -1);2(-1206 to -630); 3 (-1601 to -1207); 4 (-1979 to -1602); 5 (-2241 to -1980). (C) Lanes: 1(-2241 to -1980); 2 (-2180 to -1980); 3 (-2153 to -1980); 4 (-2109 to -1980); 5 (-2065 to -1980); 6 (-2021 to -1980). (D) Sequence of the fragment from -2241 to -2181, containing the PSF-binding site.

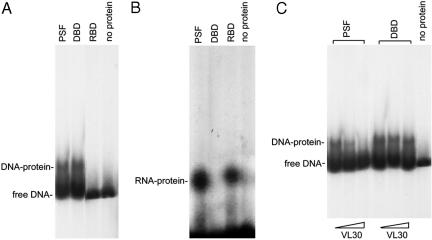

Binding of PSF Protein, DBD, and RBD to GAGE6 Promoter DNA and hVL30 RNA in Vitro. The DBD (region 1-994) and RBD (region 995-2124) domains were uncoupled on two PSF fragments, and the fragments were tested for binding to GAGE6 promoter DNA and VL30 RNA in an EMSA. Binding to the DNA occurred with the DBD fragment but not with the RBD fragment (Fig. 6A), whereas binding to hVL30 RNA occurred with the RBD fragment but not with the DBD fragment (Fig. 6B). Addition of a VL30 RNA fragment containing the PSF-binding pbt tracts (5) inhibited binding of the PSF protein but not the DBD fragment to GAGE6 promoter DNA (Fig. 6C). These results demonstrate the separate roles of the DBD and RBD in the dual functions of PSF, as a DNA-binding tumor suppressor and a RNA-binding tumor promoter.

Fig. 6.

Binding specificities of the DBD and RBD. (A) Binding of PSF protein, DBD, and RBD to GAGE6 promoter DNA. 32P-labeled GAGE6 DNA (-2241 to -1980), containing the PSF-binding site was mixed with intact PSF protein or a fragment containing the DBD or RBD, and the samples were analyzed by EMSA. (B) Binding of PSF protein, DBD, and RBD to VL30 RNA. 32P-labeled VL30 RNA was substituted for GAGE6 DNA, and the samples were analyzed as described in (A). (C) Effect of VL30 RNA on binding of PSF protein and DBD to GAGE6 promoter DNA. Unlabeled VL30 RNA was added to samples containing 32P-labeled GAGE6 DNA and mixed with PSF protein or DBD fragment. The molar ratio of VL30 RNA to GAGE6 promoter DNA was 0 in lanes 1 and 4, 10 in lanes 2 and 5, and 100 in lanes 3 and 6. The samples were analyzed by EMSA.

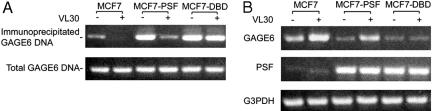

Binding of PSF Protein, DBD, and RBD to GAGE6 Promoter DNA and VL30 RNA in Vivo. An anti-PSF antibody was used to immunoprecipitate PSF from human breast tumor cells expressing a low level of PSF (MCF7 line), a high level of PSF (MCF7-PSF line), and a high level of the DBD fragment (MCF7-DBD line). The amount of GAGE6 promoter DNA coprecipitated with PSF was low in MCF7 cells and high in MCF7-PSF and MCF7-DBD cells. Transfection of VL30 cDNA encoding the pbt tracts resulted in a strong reduction of coprecipitated GAGE6 promoter DNA in MCF7 and MCF7-PSF cells and only a slight reduction in MCF-DBD cells (Fig. 7A). These results demonstrate that PSF protein and the DBD fragment bind to GAGE6 promoter DNA in vivo and that VL30 RNA binds to the RBD fragment, releasing PSF but not the DBD fragment from the DNA.

Fig. 7.

Inhibition of PSF activity in vivo by VL30 RNA. (A) Binding of PSF protein and DBD to GAGE6 promoter DNA in vivo and the effect of VL30 RNA. An anti-PSF antibody was used to immunoprecipitate PSF from human breast tumor lines expressing a low level of PSF (MCF7), a higher level of PSF (MCF7-PSF), or a high level of the DBD fragment (MCF7-DBD). The amount of GAGE6 promoter DNA coprecipitated with PSF was assayed by PCR. VL30 cDNA was transfected into cells in lanes 2, 4, and 6 but not in lanes 1, 3, and 5. (B) Effect of PSF protein, DBD fragment, and VL30 RNA on GAGE6 transcription in vivo. The cell lines were the same as in A. Transcription of GAGE6, PSF, and VL30 was assayed by semiquantitative RT-PCR. VL30 cDNA was transfected into the cells analyzed in lanes 2, 4, and 6 but not in lanes 1, 3, and 5.

Effect of PSF Protein, DBD, and VL30 RNA on GAGE6 Transcription in Vivo. GAGE6 is strongly transcribed in MCF7 cells and repressed in MCF7-PSF and MCF7-DBD cells (Fig. 7B). Transfection of VL30 cDNA encoding the pbt sequences increased GAGE6 transcription in MCF7 and MCF7-PSF cells but not in MCF7-DBD cells, consistent with the binding of VL30 RNA to the RBD but not to the DBD.

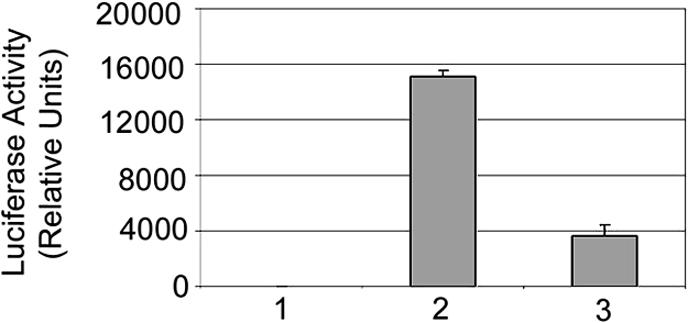

Effect of PSF Protein on Promoter Function. To determine the effect of binding PSF to the CMV promoter that lacks a PSF-binding site, the 61-bp fragment from the GAGE6 promoter, which contains the PSF-binding site, was ligated to the 5′ end of the CMV promoter. The CMV promoter with the PSF-binding site or the normal CMV promoter was ligated to the 5′ end of a luciferase reporter gene that lacked a promoter. Each luciferase construct was transiently transfected into MCF7-PSF cells, and luciferase activity was assayed after 48 h. The luciferase activity was lower in the cells transfected with the hybrid CMV-luciferase construct than with the normal CMV-luciferase construct (Fig. 8), indicating that binding of PSF to a strong promoter represses transcription of the associated gene.

Fig. 8.

The effect of PSF on CMV-regulated expression of a luciferase reporter gene. MCF7-PSF cells were transfected with a plasmid carrying a luciferase reporter gene either without a promoter (bar 1), with a wild-type CMV promoter (bar 2), or with a CMV promoter containing a PSF-binding site (Bar 3). The values for luciferase activity are the means ± SE for three experiments.

Discussion

Gene expression is a dynamic process involving selective regulation of gene transcription throughout the lifespan of an organism. We described earlier a novel mechanism for reversible gene transcription mediated by PSF protein and noncoding VL30 retroelement RNA (4, 5): PSF represses transcription of a gene by binding to the promoter, and VL30 RNA forms a complex with PSF that dissociates from the gene, activating transcription. Here, we show that the DBD and RBD of PSF can function independently: a PSF fragment containing only the DBD binds to a promoter and represses transcription but does not bind to VL30 RNA, whereas a PSF fragment containing only the RBD binds to VL30 RNA but not to a promoter (Figs. 6 and 7). Linking the DBD and RBD in the PSF molecule allows the RNA to reverse the binding of PSF to a promoter, probably by generating a conformational change through the RBD that disrupts the binding of the DBD. This mechanism proposes a major role for RNA in the regulation of gene transcription and also could account for the presence of both DBD and RBD in other regulatory proteins such as SAFB1 (10, 11).

PSF is associated with various functions, including RNA splicing, virus replication, genetic recombination, and cancer (12). Here, we showed that PSF is a human tumor-suppressor protein that coordinately represses transcription of multiple oncogenic genes (OGs) in a human tumor line and inhibits proliferation and colonization of the tumor cells (Figs. 1 and 2). Repression involves binding of the DBD in PSF to a binding site in the promoter of an OG (Fig. 5) and ligating a DBD-binding site to a promoter that does not bind PSF sensitizes a gene regulated by the promoter to repression by PSF (Fig. 8). An essential step of normal development is the switch from cell proliferation during early development to postmitotic terminal differentiation, which depends on stopping transcription of multiple genes that drive proliferation, including OG. A protein such as PSF could coordinate repression of the genes and stabilize the differentiated state. Transformation of a normal differentiated cell into a tumor cell could involve PSF in several ways, including mutations of the PSF gene that reduce the amount or activity of PSF protein (refs. 8 and 9; Fig. 4), mutations of the PSF-binding site in OG, and induced synthesis of VL30 retroelement RNA or other RNA that contain a PSF-binding sequence.

The mouse genome contains multiple copies of mVL30 retroelements that are developmentally regulated, and mouse cells contain mVL30 RNA that appear to have normal and pathological roles in gene regulation. A normal role for mVL30 RNA in mouse steroidogenesis is indicated by three findings, as follows. (i) PSF represses P450scc, the first gene in the steroidogenic pathway, by binding to the promoter region of the gene (2, 3). (ii) VL30 RNA reverses repression of P450scc by forming a complex with PSF protein (5). (iii) Pituitary-derived hormones concomitantly induce synthesis of mVL30 RNA and steroids in mouse steroidogenic cells (13). A plausible explanation for these findings is that the initial step in mouse steroidogenesis involves induced synthesis of mVL30 RNA by pituitary-derived hormones, followed by reversal of PSF-mediated repression of P450scc and activation of the steroidogenic pathway. In addition to a normal role for mVL30 RNA, there is evidence for a pathological role in oncogenesis: expression of mVL30 RNA is induced by various substances associated with oncogenesis and is elevated in transformed mouse cells (14-18). Human chromosome 11 contains a complete hVL30 retroelement with extensive sequence identity to mVL30 retroelements, and a 742-bp EST with extensive sequence identity to mVL30 RNA, including the pbt sequences that bind to PSF protein, was detected in human blastocyst cells (Data Set 1, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site), suggesting that hVL30 RNA has a role in human cells similar to the role of mVL30 RNA in mouse cells.

The association of retroelements such as VL30 with oncogenesis usually is attributed to cis effects on gene regulation and function, caused by insertional mutagenesis after reverse transcription of retroelement RNA. We showed that VL30 RNA also acts in trans by binding to PSF and reversing PSF-mediated gene repression. The ras family of oncogenic viruses contains VL30 sequences flanking the ras coding region (19). Deletion of the VL30 segments strongly reduces the oncogenic potential of a ras virus (20), and infection by a ras virus induces synthesis of VL30 RNA in the infected cells (21). These findings support a transacting role for VL30 RNA in ras-mediated transformation, possibly involving reversal of PSF-mediated repression of OG.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. James Patton for providing anti-PSF antibody and Dr. Randall Urban for providing the plasmid encoding human PSF. We thank Aiwei Sui, Ying Liu, and Henry Park for their technical assistance. Partial support was provided by a gift account for Dr. Alan Garen's laboratory.

Author contributions: X.S. and A.G. designed research; X.S. and Y.S. performed research; X.S. and A.G. analyzed data; and X.S. and A.G. wrote the paper.

Abbreviations: DBD, DNA-binding domain; OG, oncogenic gene; RBD, RNA-binding domain.

References

- 1.Patton, J. G., Porro, E. B., Galceran, J., Tempst, P. & Nadalginard, B. (1993) Genes Dev. 7, 393-406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Urban, R. J., Bodenburg, Y., Kurosky, A., Wood, T. G. & Gasic, S. (2000) Mol. Endocrinol. 14, 774-782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Urban, R. J., Bodenburg, Y. H. & Wood, T. G. (2002) Am. J. Physiol. 283, E423-E427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Song, X., Wang, B. Y., Bromberg, M., Hu, Z. W., Konigsberg, W. & Garen, A. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 6269-6273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Song, X., Sui, A. W. & Garen, A. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 621-626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hanahan, D. & Weinberg, R. A. (2000) Cell 100, 57-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benn, D. E., Dwight, T., Richardson, A. L., Delbridge, L., Bambach, C. P., Stowasser, M., Gordon, R. D., Marsh, D. J. & Robinson, B. G. (2000) Cancer Res. 60, 7048-7051. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clark, J., Lu, Y. J., Sidhar, S. K., Parker, C., Gill, S., Smedley, D., Hamoudi, R., Linehan, W. M., Shipley, J. & Cooper, C. S. (1997) Oncogene 15, 2233-2239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mathur, M., Das, S. & Samuels, H. H. (2003) Oncogene 22, 5031-5044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ivanova, M., Dobrzycka, K. M., Jiang, S., Michaelis, K., Meyer, R., Kang, K., Adkins, B., Barski, O. A., Zubairy, S., Divisova, J., Lee, A. V. & Oesterreich, S. (2005) Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 2995-3006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Townson, S. M., Kang, K., Lee, A. V. & Oesterreich, S. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 26074-26081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shav-Tal, Y. & Zipori, D. (2002) FEBS Lett. 531, 109-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bohm, S., Bakke, M., Nilsson, M., Zanger, U. M., Spyrou, G. & Lund, J. (1993) J. Biol. Chem. 268, 3952-3963. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eaton, L. & Norton, J. D. (1990) Nucleic Acids Res. 18, 2069-2077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singh, K., Saragosti, S. & Botchan, M. (1985) Mol. Cell. Biol. 5, 2590-2598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anderson, G. R., Stoler, D. L. & Scarcello, L. A. (1989) J. Biol. Chem. 264, 14885-14892. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tzavaras, T., Eftaxia, S., Tavoulari, S., Hatzi, P. & Angelidis, C. (2003) Int. J. Oncol. 23, 1237-1243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anderson, G. R. & Stoler, D. L. (1993) Bioessays 15, 265-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roop, D. R., Lowy, D. R., Tambourin, P. E., Strickland, J., Harper, J. R., Balaschak, M., Spangler, E. F. & Yuspa, S. H. (1986) Nature 323, 822-824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Velu, T. J., Vass, W. C., Lowy, D. R. & Tambourin, P. E. (1989) J. Virol. 63, 1384-1392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Owen, R. D., Bortner, D. M. & Ostrowski, M. C. (1990) Mol. Cell. Biol. 10, 1-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.