Abstract

Aims

Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) is associated with high morbidity and mortality, and there are limited proven therapeutic strategies. Exercise has been shown to be beneficial in several studies. We aimed to evaluate the efficacy of exercise on functional, physiological, and quality-of-life measures.

Methods and results

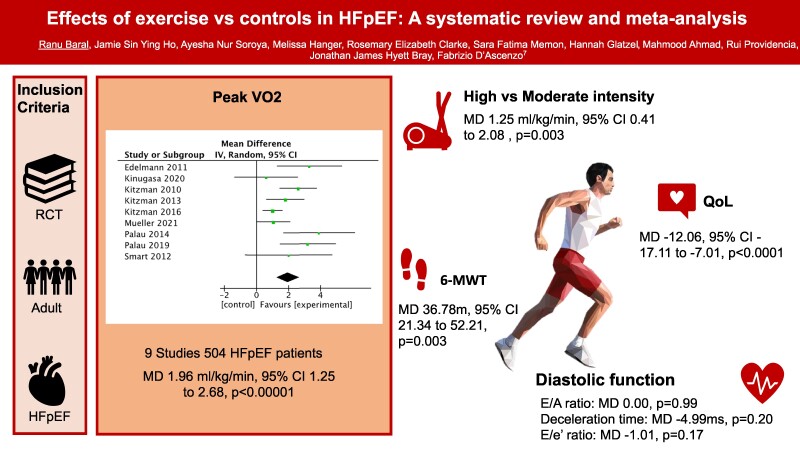

A comprehensive search of Medline and Embase was performed. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of adult HFpEF patients with data on exercise intervention were included. Using meta-analysis, we produced pooled mean difference (MD) estimates with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) with Review Manager (RevMan) software for the peak oxygen uptake (VO2), Minnesota living with heart failure (MLWHF) and, other diastolic dysfunction scores. A total of 14 studies on 629 HFpEF patients were included (63.2% female) with a mean age of 68.1 years. Exercise was associated with a significant improvement in the peak VO2 (MD 1.96 mL/kg/min, 95% CI 1.25–2.68; P < 0.00001) and MLWHF score (MD −12.06, 95% CI −17.11 to −7.01; P < 0.00001) in HFpEF. Subgroup analysis showed a small but significant improvement in peak VO2 with high-intensity interval training (HIIT) vs. medium-intensity continuous exercise (MCT; MD 1.25 mL/kg/min, 95% CI 0.41–2.08, P = 0.003).

Conclusion

Exercise increases the exercise capacity and quality of life in HFpEF patients, and high-intensity exercise is associated with a small but statistically significant improvement in exercise capacity than moderate intensity. Further studies with larger participant populations and longer follow-up are needed to confirm these findings and elucidate potential differences between high- and medium-intensity exercise.

Keywords: Exercise training, Heart failure, Meta-analysis, Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, HFpEF

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

Introduction

Heart failure is recognized as an increasing public health burden, affecting ∼920 000 people in the UK and costing $108 billion/year worldwide.1 Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) represents >50% of heart failure diagnosis in patients older than 65 years of age.2 It is increasing in prevalence3 and is also associated with high morbidity and mortality, increased re-hospitalization rates,4 and a worse quality of life.5 There has been an extensive search for novel therapeutics to improve symptom control, and exercise training is shown to have promising results.6,7

While the current European Society of Cardiology guidelines8 encourage exercise in HFpEF to improve exercise capacity, evidence for specific types or duration of exercise regimens is scarce. Several recent studies have found conflicting evidence on the relative benefit of high-intensity interval training (HIIT) and moderate-continuous training (MCT).9,10 High-intensity interval training, involving short work periods at higher intensity and high submaximal load, has been shown to be superior to continuous exercise in patients with coronary artery disease and left ventricular systolic dysfunction.10,11 Several small trials in HFpEF found that HIIT was superior to MCT,12 but the recent moderate-sized OptimEx-Clin RCT by Mueller et al.9 did not confirm these findings. Furthermore, while previous RCTs generally explored exercise regimens of several months, several RCTs of longer duration, up to 1 year, have been recently published.9,13 It is, therefore, important to further explore the optimal exercise regimen in this growing population of HFpEF patients with few treatment options, and an updated meta-analysis is warranted.

We aimed to systematically review the effect of exercise training on the cardiorespiratory function, quality of life, and diastolic function of patients with HFpEF. We also investigated the outcomes of exercise regimens of different intensities and duration in patients with HFpEF.

Methods

Search strategy

The systematic review was conducted and reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. A comprehensive literature search of Medline and Embase was conducted from inception to December 2022 using MeSH terms and keywords (see Supplementary material online, Figure S1). Reference lists of included studies and review articles were hand-searched for additional studies. Randomized controlled trials with adult HFpEF patients with data on exercise intervention, including aerobic or endurance exercise, resistance training, HIIT, inspiratory muscle training (IMT), or a combination of the above were included. Studies performed on patients with HFrEF, non-adult patients, and pre-clinical studies were excluded. Studies published in languages other than English were excluded.

Study selection and data extraction

All studies identified in our search were primarily screened using the titles and the abstracts. Each article was independently screened by at least two authors (R.B., S.F.M., A.N.S., R.E.C., M.H.) and any discrepancies were resolved by discussion and involvement of a senior author (M.A.) if necessary. Any article identified as having a potential of fulfilling our inclusion criteria underwent full-text evaluation. Among trials studying the same population with multiple publications, the trial with the maximum number of patients was included. For the included studies, relevant information such as the type of the study, characteristics of the participants, and number of patients in each group was extracted independently by two authors (S.F.M., A.N.S., R.E.C., M.H.) onto a standardized form.

Outcome measures

The primary outcomes of the study were change in the peak oxygen uptake (peak VO2) in mL/kg/min, 6 min walk test (6-MWT), Minnesota living with heart failure (MLWHF) score, and markers of diastolic function (changes in E/A ratio, E/e′ ratio, and early deceleration time).

Risk of bias assessment and publication bias

The assessment of the quality of each included studies was performed independently by two authors. The Cochrane Collaboration tool for assessing the risk of bias was used to assess the quality of included randomized studies14 and funnel plot asymmetry was used to assess publication bias when ≥10 studies were available.

Statistical analysis

The data were analysed using random effects analysis in Review Manager (RevMan) software (Version 5.3. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2014). Open Meta[Analyst] Software version 10.12 (developed by the Centre for Evidence Synthesis, Brown University, School of Public Health, Rhode Island State, USA) was used for meta-regression.15 Mean differences (MDs) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) were calculated for continuous outcomes. In studies with missing standard deviations (SDs) for change from baseline data, SD was calculated using the correlation coefficient formula.16

A subgroup analysis of studies evaluating HIIT vs. MCT, endurance training vs. non-endurance training, length, and number of sessions in exercise regimen was performed. As previous study17 has shown the achievement of more METs (metabolic equivalent of tasks), higher peak HR, and lower resting HR in a 12-week programme compared with 6 weeks and British Heart Foundation (BHF) recommends 10–12 weeks of cardiac rehabilitation,18 12 weeks were taken as the cut-off for the subgroup. For the number of sessions, a median value was calculated to divide the subgroups.

Statistical heterogeneity was evaluated by calculating I2 statistics, with the prespecified cut-offs of low heterogeneity defined as I2 value of <25%, moderate heterogeneity was 25–75%, and high heterogeneity was >75%.19 The statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05.20

Results

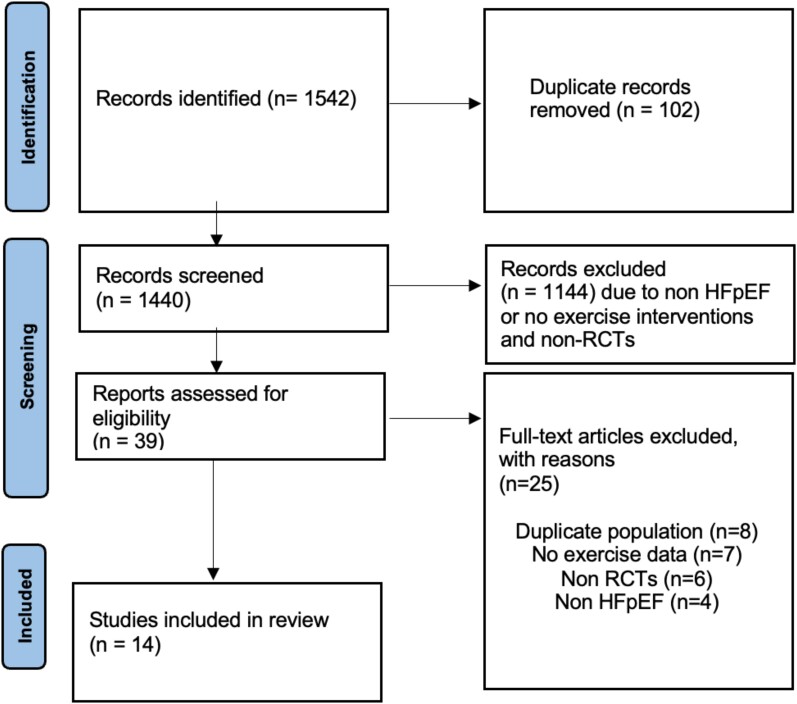

Our initial comprehensive search of the literature sources identified 1542 entries; of which, 14 articles6,7,9,12,21–30 were included in the final analysis (Figure 1). There were 629 participants in total, with a mean age of 68.1 years and 63.2% were female. All studies, except three,6,7,21 used EF >50% as the cut-off for HFpEF. Baseline characteristics of the participants are given in Table 1. The range of follow-up was 4–52 weeks. Ten studies used endurance exercise training in the intervention group vs. usual care in the control group, three studies26–28 used inspiratory muscle training, and one study29 used function electrical stimulation using direct electrical current at 25 Hz as a method of exercise training (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram of the trial selection process.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the studies included in the meta-analysis

| Author, year | n (control/exercise) | ♀ | White, % | Mean age, year | Mean BMI, kg/m2 | HTN, % | DM, % | AF, % | Exercise Type | Total sessions | Duration, weeks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | |||||||||||

| Gary et al 20046 | 13/15 | 100 | 59 | 68 ± 11 | 34 ± 7 | 88 | 31 | NR | Walking | 36 | 12 |

| Kitzman et al. 201023 | 27/26 | 75 | 70 | 69 ± 5 | 31 ± 6 | 68 | 17 | NR | Walking, cycling | 48 | 16 |

| Edelmann et al 201130 | 20/44 | 56 | NR | 65 ± 7 | 31 ± 5 | 86 | 14 | NR | Cycling, resistance training | 32 | 12 |

| Alves et al 201221 | 11/20 | 29 | NR | 63 ± 10 | 28 ± 5 | 68 | 35 | 3 | Walking, cycling | 72 | 24 |

| Smart et al 20127 | 13/12 | 48 | NR | 64 ± 6 | 32 ± 6 | 16 | 16 | NR | Cycling | 48 | 16 |

| Karavidas et al 201329 | 15/15 | 60 | NR | 69.0 ± 8.1 | NR | 100 | 47 | 40 | Functional electrical stimulation | 30 | 6 |

| Kitzman et al 201324 | 31/32 | 76 | 68 | 70 ± 7 | 32 ± 7 | 89 | 24 | NR | Walking, cycling | 48 | 16 |

| Palau et al 201426 | 12/14 | 50 | NR | NR | NR | 96 | 54 | 35 | IMT | 168 | 12 |

| Angadi et al 201522 | 6/9 | 20 | NR | 60 ± 6 | 30 ± 5 | NR | 27 | Walking | 12 | 4 | |

| Kitzman et al 201625 | 25/26 | 80 | 61 | 67 ± 5 | 40 ± 7 | 96 | 37 | 2 | Walking | 60 | 20 |

| Palau et al 201927 | 13/15 | 61 | NR | 75 ± 9 | 32 ± 5 | 96 | 36 | 54 | IMT | 168 | 12 |

| Kinugasa et al 202028 | 12/8 | 15 | NR | 76 ± 10 | NR | NR | NR | NR | IMT | 168 | 24 |

| Silveria 2020 | 9/10 | 63 | NR | 60 ± 9 | 33 ± 5 | 100 | 58 | 11 | Walking | 36 | 12 |

| Mueller et al 20219 | 60/116 | 69 | NR | 70 ± 7 | 30 ± 6 | 86 | 25 | 42 | Cycling | 156 | 52 |

DM, diabetes mellitus; AF, Atrial fibrillation; HTN, hypertension; IMT, inspiratory muscle training; NR, not reported.

Table 2.

Types of exercise

| Author, year | Exercise type |

|---|---|

| Endurance training | |

| Gary et al 20046 | Walking |

| Kitzman et al. 201023 | Walking, cycling |

| Supervised aerobic exercise training, with exercise intensity increased to 60–70% of heart rate reserve | |

| Edelmann et al 201130 | Cycling, resistance training |

| Endurance and resistance training, with a target heart rate of 50–60% of peak VO2 | |

| Alves et al 201221 | Walking, cycling |

| Interval training | |

| Smart et al 20127 | Cycling |

| Supervised, outpatient, cycle ergometer exercise training at 60 rpm, with initial intensity of 60–70% peak oxygen consumption and uptitrated by 2–5 Watts per week | |

| Kitzman et al 201324 | Walking, cycling |

| Endurance exercise training, with initially at 40–50% of heart rate, reserve and intensity increased gradually until 70% heart rate reserve | |

| Angadi et al 201522 | Walking |

| Treadmill training, with maximum 85–90% peak heart rate for HIIT | |

| Treadmill training, with maximum 70% peak heart rate for MCT | |

| Kitzman et al 201625 | Walking exercise, and intensity level was progressed as tolerated and based primarily on heart rate reserve |

| Donelli da Silveria et al 202012 | Walking |

| with 80–90% of peak VO2 and 85–95% of peak heart rate for HIIT | |

| 50–60% of peak VO2 and 60–70% of peak heart rate for MCT | |

| Mueller et al 20219 | Cycling |

| with maximum 80–90% of heart rate reserve for HIIT | |

| with maximum 35–50% of heart rate reserve for MCT | |

| Functional electrical stimulation | |

| Karavidas et al 201329 | Eight adhesive electrodes were positioned on the skin over quadriceps and gastrocnemius muscle of both legs. A direct electrical current at 25 Hz for 5 s followed by a 5 s rest. The patients were trained for 30 min a day, 5 days per week for a total of 6 weeks. |

| Inspiratory muscle training | |

| Palau et al 201426 | IMT |

| Inspiratory muscle training twice a day (20 min per session) for 12 weeks, with breathing at a resistance equal to 25–30% and modified each session according to the 25–30% of inspiratory muscle training measured | |

| Palau et al 201927 | IMT |

| Inspiratory muscle training twice daily (20 min each session) for 12 weeks, resistance equal to 25%– 30% of their maximal inspiratory pressure for 1 week and was modified each session to 25–30% of their measured maximal inspiratory pressure | |

| Kinugasa et al 202028 | Inspiratory muscle training once daily for 20 min for 24 weeks, resistance equal to 30% of their maximum inspiratory muscle pressure. |

Risk of bias assessment and publication bias

The Cochrane risk of bias assessing the quality of included studies is demonstrated in Supplementary material online, Table S1. All studies had at least two or more domains with unclear or high risk of bias. Publication bias was assessed using funnel plot asymmetry which was suggestive of small study bias (see Supplementary material online, Figure S2).

Exercise capacity

Nine studies reported data on exercise capacity at baseline and after a period of exercise training, involving 504 HFpEF patients. Exercise was associated with a significant improvement in the peak VO2 (MD 1.96 mL/kg/min, 95% CI 1.25–2.68, P < 0.00001; Figure 2), with moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 58%). We also analysed 6-MWT to assess exercise capacity. There was a significant improvement in 6-MWT in the intervention group compared with control (MD 36.78 m, 95% CI 21.34–52.21, P < 0.00001; Supplementary material online, Figure S3).

Figure 2.

Forest plot showing the effect of exercise training on peak oxygen uptake (VO2) among participants with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. CI, confidence interval; MD, mean difference.

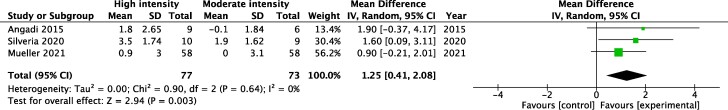

Three studies9,12,22 on 150 patients compared the effect of HIIT vs. MCT in HFpEF. The exercise regime for these studies is outlined in Table 1. Overall, MCT was progressed to 60–70% of the peak heart rate (PHR) whilst HIIT was progressed to 80–95% of PHR. The PHR was considerably lower at 35–50% in the moderate subgroup in the Mueller study. Meta-analysis showed a significant improvement in the peak VO2 with HIIT compared with MCT (MD 1.25 mL/kg/min, 95% CI 0.41–2.08, P = 0.003, Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Subgroup analysis of studies investigating high- vs. moderate-intensity exercise. Forest plot showing the effect of exercise training on peak oxygen uptake (VO2) among participants with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. CI, confidence interval; MD, mean difference.

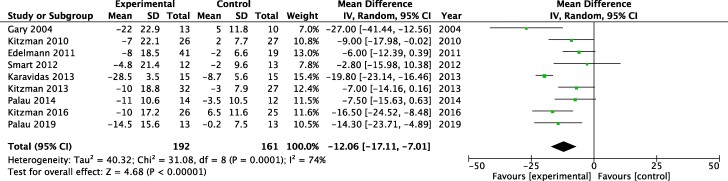

Quality of life

Nine studies reported an effect of exercise on quality of life determined using the MLWHF questionnaire. Apart from one study,21 all studies showed >5-point reduction MLWHF score, which has been denoted as a clinically meaningful improvement. Overall, there was a statistically significant improvement in the MLWHF score among exercise training group compared with controls (MD −12.06, 95% CI −17.11 to −7.01, P < 0.0001; Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Effect of exercise training on quality of life. Forest plot showing the effect of exercise training quality of life, estimated using the Minnesota living with heart failure (MLWHF) score, among participants with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. CI, confidence interval; MD, mean difference.

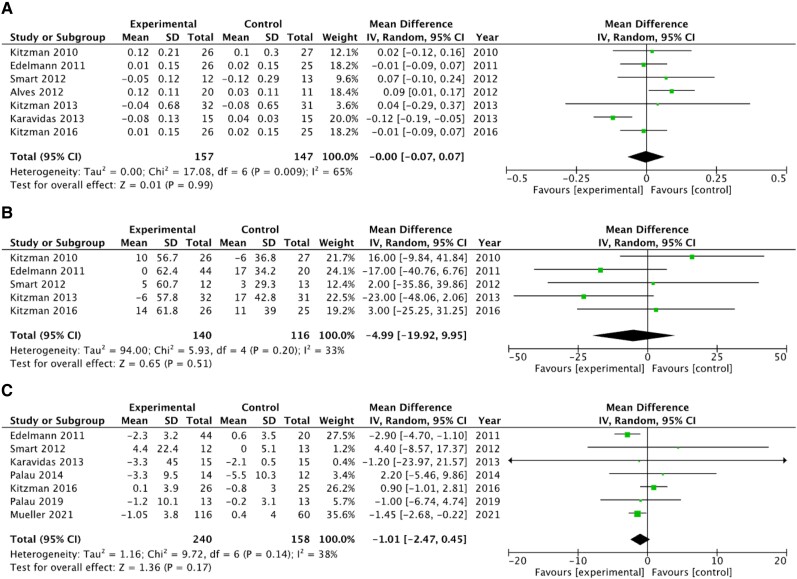

Diastolic function

Overall, in pooled analyses, exercise had no significant effect on diastolic function in HFpEF as measured by the E/A ratio (MD 0.00, 95% CI −0.07 to 0.07, P = 0.99; Figure 5A), deceleration time (MD −4.99 ms, 95% CI −19.92 to 9.95, P = 0.20; Figure 5B), and E/e′ ratio (MD −1.01, 95% CI −2.47 to 0.45, P = 0.17; Figure 5C).

Figure 5.

Effect of exercise training on diastolic function. Forest plot showing the effect of exercise training on the E/A ratio (A), deceleration time (B) on the E/e′ ratio (C) among participants with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. CI, confidence interval; MD, mean difference.

Subgroup analysis and meta-regression

To investigate the source of heterogeneity of the primary outcome analysis, we performed subgroup analysis and meta-regressions. Comparing endurance vs. non-endurance-based regimes, there was a trend for an increase in peak VO2 with non-endurance regimes (MD 1.59 mL/kg/min, 95% CI 1.19–1.98, P = 0.08, Supplementary material online, Figure S4). Additionally, our sub-analyses showed that both short (≤12 weeks) and longer programmes (≥16 weeks) improve peak VO2 (MD 3.41 vs. 1.43 mL/kg/min, P = 0.002, Supplementary material online, Figure S5) with the high heterogeneity (I2 = 89%) not allowing any clear inferences from comparison of subgroup treatment effects. The sub-analyses for the number of sessions showed benefit for programmes with ≤48 sessions and ≥60 sessions, with no significant subgroup differences observed when comparing the two groups (MD 2.34 vs. 1.7 mL/kg/min, P = 0.31, Supplementary material online, Figure S6). This was confirmed with meta-regression analysis which failed to generate significant interaction effects (co-efficient −0.053, P = 0.06; Supplementary material online, Figure S7A for duration, co-efficient 0.001, P = 0.93; Supplementary material online, Figure S7B for the number of sessions). Furthermore, sensitivity analysis without Karavidas et al.29 which applied functional electrical stimulation to assess the effect on the increase in MLWHF questionnaire showed no significant differences (see Supplementary material online, Figure S8).

Discussion

Our meta-analysis of RCTs shows that training improves exercise capacity and quality of life in patients with HFpEF.31,32 Our analysis shows a benefit of exercise training even after a short number of sessions or weeks of training. Even though we could not observe a dose–response effect, study heterogeneity and the small number of included studies do not allow any sound inferences on this respect. High-intensity interval training led to a small but significant improvement in peak VO2 when compared with medium-intensity continuous exercise.

Previous meta-analyses.33,34 Guo et al.34 analysed 16 studies to demonstrate the effects of exercise in HFpEF, but the meta-analysis included non-RCTs and mixed studies with the same population. This also extends to similar recent meta-analysis.32,35 In this study, however, we used stringent criteria to exclude studies with the same population increasing result accuracy and included recently published newer studies. Secondly, diastolic function mainly signified by E/A, deceleration time, and E/E′ remained unchanged with exercise training.

The previous meta-analyses by Pandey et al.33 and Boulmpou et al.32 both showed that exercise training improved the peak exercise VO2 across four and eight studies, respectively.31,32 In our meta-analysis of 11 RCTs, exercise training was associated with a 1.96 mL/kg/min (95% CI 1.25–2.68). However, the increase in peak VO2 did not reach the prespecified clinically significant increase of 2.5 mL/kg/min set out in the OptimEx-Clin trial.9 Interestingly, subgroup analysis of studies comparing inspiratory training vs. aerobic (2.53 vs. 1.45 mL/kg/min) showed a clinically meaningful increase in peak VO2 with the caveat that these subgroups only included three studies.

Besides, our study did not show a significant improvement in exercise capacity with longer duration of exercise regime and higher number of sessions. A similar unchanged level of peak VO2 with a longer duration was seen in the Mueller study, where the peak VO2 did not show any significant interactions between both intensities after 12 months. A possible explanation would be the low patient adherence, as, for example, ∼60% of patients completed 12 months of exercise in the OptimEx-Clin study, compared with 80% for 3 months.9 Research into strategies that improve exercise adherence suggests that provision of feedback and monitoring may be effective.36 Future trials, particularly those of longer durations, may adopt such strategies to improve patient adherence.

Nevertheless, compared with no exercise, 36 sessions of high-intensity exercise were observed to be associated with increased peak VO2 and each 1 mL/kg/min increase in peak VO2 conferred a 58% improvement in 5-year mortality.37 Exercise in HFpEF is also associated with improvements in other markers of exercise capacity such as metabolic equivalents of task (MET) scores in treadmill stress tests.38 HFpEF patients with higher MET scores and thus cardiopulmonary fitness had higher survival in a retrospective cohort study.39 Although suggested by observation studies, the clinical benefit of improved peak VO2 associated with exercise training requires further validation in RCTs.

Exercise training also improves the quality of life of patients with HFpEF.31,40 The Exercise training in Diastolic Heart Failure Pilot (Ex-DHF-P) RCT showed that endurance/resistance training was associated with improved physical functioning, bodily pain, general health, social functioning, and mental component score on the 36-item Short-form Health Survey (SF-36).40 Exercise training was also associated with reduced symptoms of depression on the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9).40 Interestingly, quality of life is shown to be inversely associated with obesity and worse physical capacity and activity levels, including peak VO2 and 6 min walking distance, but not echocardiographic markers of diastolic function.41 Similarly, we found that exercise training improved quality of life on MLWHF questionnaire, but not markers of diastolic function. This has been shown in previous studies.23,26 E/e′ is the most established marker of diastolic dysfunction, but existing data only show a modest correlation with invasive filling pressures and outcomes in HFpEF.42 This suggests that quality of life and exercise capacity are important endpoints of clinical significance, and exercise training has positive impacts on both, while the role of echocardiographic diastolic markers as exercise determinants requires further investigation.

Exercise training improves exercise capacity and quality of life, yet, how much exercise causes improvements is currently uncertain. There have been contradicting results for the effects of high vs. moderate exercise in exercise capacity in HFpEF.9,12,22 The previous meta-analysis by Boulmpou et al.32 included two studies on 34 patients that compared HIIT with aerobic exercise, and reported a significantly greater improvement in peak VO2 with HIIT. In contrast, the recently published OptimEx-Clin RCT involving 176 patients randomized to HIIT, MCT, and guideline control showed no significant differences in peak VO2 between HIIT and MCT.9 With the addition of this study by Mueller et al.9 in our meta-analysis, we found that HIIT was associated with a significant but not clinical meaningful improvement in exercise capacity when compared with MCT. In addition, these studies have highlighted the concerns regarding adherence of the participants to the training regime,9,12,22 which perhaps points to the difficulty in translating training as a therapeutic target in clinical settings.

Limitations

This meta-analysis has several limitations. First, many of the RCTs included were performed on very small trial populations, and the studies were unblinded due to the nature of the intervention. It is likely due to many challenges associated with exercise training highlighted in previous studies, for example, the difficulty with adherence and limitation of patient recruitment to those able to exercise.9,31 Secondly, the follow-up durations in these studies differed, and the mean follow-up duration was relatively short. Thirdly, the definition of HFpEF, including EF cut-off, used in the studies was different, perhaps due to the challenge of diagnosing HFpEF and evolving diagnostic criteria recommended by international guidelines.43 This is reflected in the varied baseline characteristics in the participants among the included studies. Additionally, there are no exercise data reported across baseline characteristics such as age which limits the plausibility of the results. Lastly, the result of the funnel plot for the primary outcome suggests the presence of publication bias. Considering that all the included studies, except one, had fewer than 50 subjects in each arm, studies in this field may be susceptible to small-study effects. Future studies should aim to recruit a greater number of subjects to reduce the likelihood of a small-study effect.

Conclusions

Exercise increases the exercise capacity and quality of life in HFpEF patients, and high-intensity exercise is associated with a small but significant improvement in exercise capacity than moderate intensity. There is, however, no significant improvement with longer duration and higher number of sessions. Studies with a larger participant population with longer follow-up are warranted to determine the long-term effects of high- and moderate-intensity exercise.

Exercise increases the exercise capacity and quality of life in HFpEF patients, and high-intensity exercise is associated with small but statistically significant improvement in exercise capacity than moderate intensity. The clinical significance of this observed difference is questionable and needs further attention. Additionally, there is no significant improvement with longer duration and higher number of sessions. Studies with a larger participant population with longer follow-up are warranted to determine the long-term effects of high- and moderate-intensity exercise.

Lead author biography

Ranu Baral, MBBS, MRes, graduated from Norwich Medical School in the UK with a degree in medicine and an intercalated Master of Research degree in 2019. She completed her initial training in Norwich and subsequently commenced internal medical training in South-East London. Dr Baral has a longstanding interest in heart failure and her primary research focuses on novel therapeutics in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Ranu Baral, Kings College Hospital NHS Trust, London, Denmark Hill, London SE5 9RS, UK.

Jamie Sin Ying Ho, Royal Free London NHS Foundation Trust, Pond St, London NW3 2QG, UK.

Ayesha Nur Soroya, University College London, Gower St, London WC1E 6BT, UK.

Melissa Hanger, University College London, Gower St, London WC1E 6BT, UK.

Rosemary Elizabeth Clarke, University College London, Gower St, London WC1E 6BT, UK.

Sara Fatima Memon, University College London, Gower St, London WC1E 6BT, UK.

Hannah Glatzel, Stoke Mandeville Hospital, Mandeville Rd, Aylesbury HP21 8AL, UK.

Mahmood Ahmad, Royal Free London NHS Foundation Trust, Pond St, London NW3 2QG, UK.

Rui Providencia, University College London, Gower St, London WC1E 6BT, UK; Barts Heart Centre, Barts Health NHS Trust, W Smithfield, London EC1A 7BE, UK.

Jonathan James Hyett Bray, Institute of Life Sciences-2, Swansea Bay University Health Board and Swansea University Medical School, Swansea University, Sketty, Swansea SA2 8QA, UK.

Fabrizio D’Ascenzo, Division of Cardiology, Department of Medical Science, University of Turin, Via Verdi 8, 10124 Torino, P.I. 02099550010, Italy.

Data availability

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at European Heart Journal Open online.

Ethical approval

Meta-analysis of published data, so no ethics approval was required.

Funding

RP is supported by the UCL BHF Research Accelerator AA/18/6/34223, NIHR grant NIHR129463 and UKRI/ERC/HORIZON 10103153 Aristoteles.

References

- 1. Cook C, Cole G, Asaria P, Jabbour R, Francis DP. The annual global economic burden of heart failure. Int J Cardiol 2014;171:368–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pfeffer MA, Shah AM, Borlaug BA. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction in perspective. Circ Res 2019;124:1598–1617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Golla MSG, Hajouli S, Ludhwani D. Heart failure and ejection fraction. StatPearls. 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK553115/ (10 June 2024).

- 4. Cheng RK, Cox M, Neely ML, Heidenreich PA, Bhatt DL, Eapen ZJ, Hernandez AF, Butler J, Yancy CW, Fonarow GC. Outcomes in patients with heart failure with preserved, borderline, and reduced ejection fraction in the Medicare population. Am Heart J 2014;168:721–730.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lewis EF, Lamas GA, O’Meara E, Granger CB, Dunlap ME, McKelvie RS, Probstfield JL, Young JB, Michelson EL, Halling K, Carlsson J, Olofsson B, McMurray JJV, Yusuf S, Swedberg K, Pfeffer MA. Characterization of health-related quality of life in heart failure patients with preserved versus low ejection fraction in CHARM. Eur J Heart Fail 2007;9:83–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gary RA, Sueta CA, Dougherty M, Rosenberg B, Cheek D, Preisser J, Neelon V, McMurray R. Home-based exercise improves functional performance and quality of life in women with diastolic heart failure. Heart Lung 2004;33:210–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Smart NA, Haluska B, Jeffriess L, Leung D. Exercise training in heart failure with preserved systolic function: a randomized controlled trial of the effects on cardiac function and functional capacity. Congest Heart Fail 2012;18:295–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M, Gardner RS, Baumbach A, Böhm M, Burri H, Butler J, Čelutkienė J, Chioncel O, Cleland JG. 2021 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Developed by the task force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J 2021;42:3599–3726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mueller S, Winzer EB, Duvinage A, Gevaert AB, Edelmann F, Haller B, Pieske-Kraigher E, Beckers P, Bobenko A, Hommel J, Van de Heyning CM, Esefeld K, von Korn P, Christle JW, Haykowsky MJ, Linke A, Wisløff U, Adams V, Pieske B, van Craenenbroeck EM, Halle M. Effect of high-intensity interval training, moderate continuous training, or guideline-based physical activity advice on peak oxygen consumption in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2021;325:542–551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wisløff U, Støylen A, Loennechen JP, Bruvold M, Rognmo Ø, Haram PM, Tjønna AE, Helgerud J, Slørdahl SA, Lee SJ, Videm V, Bye A, Smith GL, Najjar SM, Ellingsen Ø, Skjærpe T. Superior cardiovascular effect of aerobic interval training versus moderate continuous training in heart failure patients: a randomized study. Circulation 2007;115:3086–3094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rognmo Ø, Hetland E, Helgerud J, Hoff J, Slørdahl SA. High intensity aerobic interval exercise is superior to moderate intensity exercise for increasing aerobic capacity in patients with coronary artery disease. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 2004;11:216–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Donelli da Silveira A, Beust de Lima J, da Silva Piardi D, dos Santos Macedo D, Zanini M, Nery R, Laukkanen JA, Stein R. High-intensity interval training is effective and superior to moderate continuous training in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a randomized clinical trial. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2020;27:1733–1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hieda M, Sarma S, Hearon CM, Macnamara JP, Dias KA, Samels M, Palmer D, Livingston S, Morris M, Levine BD. One-year committed exercise training reverses abnormal left ventricular myocardial stiffness in patients with stage B heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circulation 2021;144:934–946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Blencowe NS, Boutron I, Cates CJ, Cheng H-Y, Corbett MS, Eldridge SM. Rob 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019;366:l4898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wallace BC, Dahabreh IJ, Trikalinos TA, Lau J, Trow P, Schmid CH. Closing the gap between methodologists and end-users: R as a computational back-end. J Stat Soft 2012;49:1–15. doi: 10.18637/jss.v049.i05. OpenMeta[Analyst] – CEBM @ Brown [Internet]. http://www.cebm.brown.edu/openmeta/ (13 May 2023). 510th June 2024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.4 2023. Chapter 13: Assessing risk of bias due to missing results in a synthesis. [Google Scholar]

- 17. El Missiri A, Amin SA, Tawfik IR, Shabana AM. Effect of a 6-week and 12-week cardiac rehabilitation program on heart rate recovery. Egypt Heart J 2020;72:69. doi: 10.1186/s43044-020-00107-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. British Heart Foundation . Cardiac rehabilitation [internet]. 2023. https://www.bhf.org.uk/informationsupport/support/practical-support/cardiac-rehabilitation (10 June 2024).

- 19. Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. Br Med J 2003;327:557–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.4 2023. Chapter 15: Interpreting results and drawing conclusions. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Alves AJ, Ribeiro F, Goldhammer E, Rivlin Y, Rosenschein U, Viana JL, Duarte JA, Sagiv M, Oliveira J. Exercise training improves diastolic function in heart failure patients. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2012;44:776–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Angadi SS, Mookadam F, Lee CD, Tucker WJ, Haykowsky MJ, Gaesser GA. High-intensity interval training vs. moderate-intensity continuous exercise training in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a pilot study. J Appl Physiol 2015;119:753–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kitzman DW, Brubaker PH, Morgan TM, Stewart KP, Little WC. Exercise training in older patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction: a randomized, controlled, single-blind trial. Circ Heart Fail 2010;3:659–667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kitzman DW, Brubaker PH, Herrington DM, Morgan TM, Stewart KP, Hundley WG, Abdelhamed A, Haykowsky MJ. Effect of endurance exercise training on endothelial function and arterial stiffness in older patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction: a randomized, controlled, single-blind trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;62:584–592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kitzman DW, Brubaker P, Morgan T, Haykowsky M, Hundley G, Kraus WE, Eggebeen J, Nicklas BJ. Effect of caloric restriction or aerobic exercise training on peak oxygen consumption and quality of life in obese older patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction a randomized, controlled trial. JAMA 2016;315:36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Palau P, Domínguez E, Núñez E, Schmid JP, Vergara P, Ramón JM, Mascarell B, Sanchis J, Chorro FJ, Núñez J. Effects of inspiratory muscle training in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2014;21:1465–1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Palau P, Domínguez E, López L, Ramón JM, Heredia R, González J, Santas E, Bodí V, Miñana G, Valero E, Mollar A, Bertomeu González V, Chorro FJ, Sanchis J, Lupón J, Bayés-Genís A, Núñez J. Inspiratory muscle training and functional electrical stimulation for treatment of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: the TRAINING-HF trial. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed) 2019;72:288–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kinugasa Y, Sota T, Ishiga N, Nakamura K, Kamitani H, Hirai M, Yanagihara K, Kato M, Yamamoto K. Home-based inspiratory muscle training in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction: a preliminary study. J Card Fail 2020;26:1022–1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Karavidas A, Driva M, Parissis JT, Farmakis D, Mantzaraki V, Varounis C, Paraskevaidis I, Ikonomidis I, Pirgakis V, Anastasiou-Nana M, Filippatos G. Functional electrical stimulation of peripheral muscles improves endothelial function and clinical and emotional status in heart failure patients with preserved left ventricular ejection fraction. Am Heart J 2013;166:760–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Edelmann F, Gelbrich G, Dngen HD, Fröhling S, Wachter R, Stahrenberg R, Binder L, Töpper A, Lashki DJ, Schwarz S, Herrmann-Lingen C, Löffler M, Hasenfuss G, Halle M, Pieske B. Exercise training improves exercise capacity and diastolic function in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: results of the Ex-DHF (exercise training in diastolic heart failure) pilot study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;58:1780–1791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pandey A, Parashar A, Kumbhani DJ, Agarwal S, Garg J, Kitzman D, Agarwal S, Garg J, Kitzman D, Levine BD, Drazner M, Berry JD. Exercise training in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. Circ Heart Fail 2015;8:33–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Boulmpou A, Theodorakopoulou MP, Boutou AK, Alexandrou ME, Papadopoulos CE, Bakaloudi DR, Pella E, Sarafidis P, Vassilikos V. Effects of different exercise programs on the cardiorespiratory reserve in HFpEF patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hellenic J Cardiol 2022;64:58–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pandey A, Parashar A, Kumbhani DJ, Agarwal S, Garg J, Kitzman D, Agarwal S, Garg J, Kitzman D, Levine BD, Drazner M, Berry JD. Exercise training in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction meta-analysis of randomized control trials. Circ Heart Fail 2015;8:33–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Guo Y, Xiao C, Zhao K, He Z, Liu S, Wu X, Shi S, Chen Z, Shi R. Physical exercise modalities for the management of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 2022;79:698–710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Fukuta H. Effects of exercise training on cardiac function in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Card Fail Rev 2020;6:e26. doi: 10.15420/cfr.2020.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Room J, Hannink E, Dawes H, Barker K. What interventions are used to improve exercise adherence in older people and what behavioural techniques are they based on? A systematic review. BMJ Open 2017;7:e019221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hsu CC, Fu TC, Yuan SS, Wang CH, Liu MH, Shyu YC, Cherng W-J, Wang J-S. High-intensity interval training is associated with improved long-term survival in heart failure patients. J Clin Med 2019;8:409. doi: 10.3390/jcm8030409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Orimoloye OA, Kambhampati S, Hicks AJ, Al Rifai M, Silverman MG, Whelton S, Qureshi W, Ehrman JK, Keteyian SJ, Brawner CA, Dardari Z, Al-Mallah MH, Blaha MJ. Higher cardiorespiratory fitness predicts long-term survival in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction: the Henry Ford Exercise Testing (FIT) project. Arch Med Sci 2019;15:350–358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Borlaug BA, Olson TP, Lam CSP, Flood KS, Lerman A, Johnson BD, Redfield MM. Global cardiovascular reserve dysfunction in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;56:845–854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Nolte K, Herrmann-Lingen C, Wachter R, Gelbrich G, Düngen HD, Duvinage A, Hoischen N, von Oehsen K, Schwarz S, Hasenfuss G, Halle M, Pieske B, Edelmann F. Effects of exercise training on different quality of life dimensions in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: the Ex-DHF-P trial. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2015;22:582–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Reddy YNV, Rikhi A, Obokata M, Shah SJ, Lewis GD, AbouEzzedine OF, Dunlay S, McNulty S, Chakraborty H, Stevenson LW, Redfield MM, Borlaug BA, . Quality of life in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: importance of obesity, functional capacity, and physical inactivity. Eur J Heart Fail 2020;22:1009–1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Nauta JF, Hummel YM, van der Meer P, Lam CSP, Voors AA, van Melle JP. Correlation with invasive left ventricular filling pressures and prognostic relevance of the echocardiographic diastolic parameters used in the 2016 ESC heart failure guidelines and in the 2016 ASE/EACVI recommendations: a systematic review in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail 2018;20:1303–1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Pieske B, Tschöpe C, De Boer RA, Fraser AG, Anker SD, Donal E, Edelmann F, Fu M, Guazzi M, Lam CSP, Lancellotti P, Melenovsky V, Morris DA, Nagel E, Pieske-Kraigher E, Ponikowski P, Solomon SD, Vasan RS, Rutten FH, Voors AA, Ruschitzka F, Paulus WJ, Seferovic P, Filippatos G. How to diagnose heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: the HFA-PEFF diagnostic algorithm: a consensus recommendation from the heart failure association (HFA) of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2019;40:3297–3317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.