Abstract

Rinderpest virus is a morbillivirus and the causative agent of an important disease of cattle and wild bovids. The P genes of all morbilliviruses give rise to two proteins in addition to the P protein itself: use of an alternate start translation site, in a second open reading frame, gives rise to the C protein, while cotranscriptional insertion of an extra base gives rise to the V protein, a fusion of the amino-terminal half of P to a short, highly conserved, cysteine-rich zinc binding domain. Little is known about the function of either of these two proteins in the rinderpest virus life cycle. We have constructed recombinant rinderpest viruses in which the expression of these proteins has been suppressed, individually and together, and studied the replication of these viruses in tissue culture. We show that the absence of the V protein has little effect on the replication rate of the virus but does lead to an increase in synthesis of genome and antigenome RNAs and a change in cytopathic effect to a more syncytium-forming phenotype. Virus that does not express the C protein, on the other hand, is clearly defective in growth in all cell lines tested, and this defect appears to be related to a decreased transcription of mRNA from viral genes. The phenotypes of both individual mutant virus types are both expressed in the double mutant expressing neither V nor C.

Rinderpest virus (RPV) belongs to the Morbillivirus genus of the family Paramyxoviridae and is thus related to Measles virus (MV), Canine and Phocid (seal) distemper viruses, the cetacean morbillivirus, and Peste des petits ruminants virus. The disease it causes (rinderpest) has for decades been one of the most widespread and economically important diseases affecting cattle in Africa, the Middle East, and the Indian subcontinent. It has been eliminated from most of these areas in recent years, largely through the efforts of the European Union- and Food and Agriculture Organization-backed EMPRES program, with the aim of global eradication by 2010 (22). Like all of the morbilliviruses, there is only one serotype of RPV, yet wide variation can be found in the pathogenicity of field isolates, from those causing essentially 100% mortality to others in which infection causes barely detectable clinical signs (58, 64). The molecular basis of this variation is unknown.

All of the Paramyxoviridae have single-stranded RNA genomes of negative sense, with six viral genes, which are transcribed in order from a single promoter at the 3′ end of the genome. From the second of those genes (the P gene), through utilization of more than one translation initiation codon and/or the introduction of one or more nontemplated residues to allow access to alternate reading frames, more than one protein is always produced, though the exact number and type of extra proteins vary both between and within genera. The expression of other proteins from overlapping reading frames was first shown in Sendai virus (SeV) (26, 55). SeV (15, 29), and Human parainfluenza virus type 1 (hPIV1) (8) express a set of four carboxy-coterminal proteins (C′, C, Y1, and Y2), whereas the morbilliviruses express only a single C protein (6), and the rubulaviruses (e.g., Mumps virus and Simian virus 5 [SV5]), with the possible exception of La-Piedad-Michoacan-Mexico virus (7), do not express a C protein at all. The C proteins of MV (6) and SeV (67) have been reported to associate with the N and P proteins in infected cells, and the SeV C is found in purified virions (67). Other reports have suggested that neither C nor V of MV associates with other viral proteins (45). In vitro studies suggested that the SeV C protein specifically decreases transcription from the genome promoter (i.e., mRNA and antigenome synthesis) (9, 57), possibly through interaction with the L protein (33). Recombinant SeVs lacking expression of either C′ or C are viable, grow as well as the wild type, and show the expected increase in viral mRNA levels (41); however, the double mutant grows more slowly (39, 41), and abrogation of expression of all four C/Y proteins results in a virus that is very severely disabled (39). An SeV mutation in the C protein has been reported to abolish pathogenicity in mice (25). MV lacking its one C protein grows normally in tissue culture lines (53) but not in peripheral blood leukocytes (21). The expression of the P protein and the V protein from viral mRNAs differing only by insertion of nontemplated bases was first shown for SV5 (59); in this group of viruses the genome codes for the V protein, while insertion of two G's is required to produce a mRNA from which the P protein is translated. Similar editing was subsequently shown in MV (10) and SeV (61) and shown to be a virus-encoded activity (61), possibly resulting from polymerase stuttering on the genome template during mRNA transcription (62). In SeV and the morbilliviruses, the P gene encodes the P protein directly, and insertion of a single extra G is required to produce a V-encoding mRNA. The V protein always shares the amino-terminal half of the P protein. In V, this is followed by a highly conserved motif containing seven cysteines which has been shown to bind zinc (44, 51) and also to be required for interaction of the V protein with damage-specific DNA binding protein (43). The V proteins of mumps and SV5 are found in virions (51, 56), but those of MV (27) and SeV (14) are not. This difference may be due to differences in the P proteins (which are not conserved as to sequence between these two groups of viruses); the N-terminal domain common to P and V proteins has been shown, in SeV (34) and SV5 (54), to interact with free N protein, i.e., protein that has not been incorporated into nucleocapsids, while SV5 V protein has also been shown to bind to nucleocapsids (50, 59). Both immunofluorescence (65) and biochemical (27) studies of MV V protein have shown it to be distributed throughout the cytoplasm, as is that of SeV (14), whereas the V proteins of hPIV2 (66) and SV5 (51, 52) contain nuclear localization signals.

Studies in vitro have shown that the SeV V protein inhibits genome replication but not mRNA transcription (13, 17, 33); recombinant SeVs that do not express the V protein show higher rates of genome synthesis, though only in some cell types (18, 19, 35, 36). In MV, on the other hand, the major effects of abrogating V expression were an increase in viral mRNA transcription and protein synthesis (60). In all cases, viruses lacking V protein appear to grow well in tissue culture but are defective in growth in animals (35, 60).

We have recently developed techniques to create recombinant RPV (rRPV) based on the most commonly used vaccine strain (1) and have used these techniques to study the utility of recombinant morbilliviruses as immunizing agents (2, 63), as well as creating chimeric viruses containing elements of RPV and other morbilliviruses (S. C. Das, M. D. Baron, and T. Barrett, unpublished data). Since the C and V proteins clearly have important roles in regulating viral replication and pathogenicity, we have also investigated the roles of the C and V proteins in RPV replication by creating viruses in which the expression of one or both of these proteins has been abolished. We report here the effects of these changes on the growth of the resultant mutant RPVs in tissue culture.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and virus.

Cells were maintained and virus stocks were grown and titered as described elsewhere (1). Rescue of rRPV from cDNA was performed as previously described (1) except that transfection was performed using FuGENE6 (Roche Biologicals) or Transfast (Promega), as described by the manufacturer, and using a ratio of 6 μl of reagent per μg of plasmid DNA for both reagents. For measuring viral growth rate, B95a cells (2 × 106 per 35-mm-diameter well), Vero cells, or primary bovine skin fibroblasts (5 × 105 per well) were infected with rRPV at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.005 to 0.04 (depending on the experiment) for 1 h. The inoculum was removed, the cells were washed twice with medium, and 2 ml of medium was added to each well. Samples were taken immediately and at various times thereafter and stored at −70°C. After thawing and clarifying at 2,500 rpm for 10 min, the 50% tissue culture infective dose (TCID50) of released virus was quantitated by standard methods. All results were normalized to an initial infection with 104 TCID50 per well.

For observation of individual foci of infection, B95a cells were plated at 2 × 106 cells per well 2 days before use. Virus at 10 to 100 TCID50 per well was added and allowed to adsorb for 1 h, after which the cells were washed once with medium and then overlaid with Eagle's medium containing 4% fetal calf serum and 1% (wt/vol) carboxymethyl cellulose. After 5 to 6 days, most of the covering medium was removed and the cells were overlaid with undiluted Giemsa's stain (Merck) for 30 min at room temperature. The stain and the remaining carboxymethyl cellulose were washed off with water, and the stained foci were photographed.

Molecular biology and assays.

Except where indicated, all DNA manipulation was by standard methods. Plasmids were cloned and grown in Escherichia coli JM109 or DH5α and purified on CsCl gradients or using Qiagen columns. The change of the C open reading frame (ORF) initiation codon was introduced into pKSP (1) by using unique site elimination mutagenesis (20). The XmaI-XmaI fragment containing the mutation was swapped with the corresponding fragment from pMDBNP (1) to give pMDBNPCE, to which were added the M and F genes from pKSMF (1). The ClaI-SunI fragment containing the whole N, P, and M genes and most of the F gene was then swapped for the corresponding segment from the full genome cDNA clone in pMDBRPV. The change to editing site was performed by using the Quick-Change mutagenesis protocol (Stratagene) on pMDBNP; the sequenced ApaI-KpnI fragment was then used to replace the same section in pMDBNP (to give pMDBNPVE) or pMDBNPCE (to give pMDBNPVCE), and the single and double mutations were assembled into the full-length genome as described above. The introduction of stop codons in the C ORF was done by using two-stage overlap PCR (33), modified by using the proofreading DNA polymerase Pfu (Stratagene) instead of Taq DNA polymerase. The template was either pMDBNPCE or pMDBNPVE, and the XhoI-KpnI fragments containing the mutations were removed from these plasmids and inserted into pMDBNP-PacSbf, a version of pMDBNP where PacI and SbfI sites have been introduced at the ends of the N and P ORFs, respectively. The ClaI and SbfI sites at the beginning of the N gene and end of the P gene were then used to transfer the mutations into pMDBRPV2C, a version of pMDBRPV containing the same restriction sites (which have been found to have no effect on virus growth in vitro).

RNA from RPV-infected cells was prepared using Trizol (Life Technologies), and reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) was performed as previously described (4). PCR products were sequenced directly using T7 DNA polymerase (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) after treatment with shrimp alkaline phosphatase and exonuclease I (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). Primer extension analysis was performed essentially as described previously (30), except that the primer used was 5′-GGTCGATTTCACGTCTGT-3′ and the stopping nucleotide was ddA rather than ddG.

Semiquantitative RT-PCR was performed essentially like ordinary RT-PCR except that specific primers, rather than random hexamers, were used for the RT step. Total RNA (1.2 μg) was transcribed with 10 pmol of RPV primer or 100 μg of oligo(dT)15 (Promega) in a final volume of 20 μl; all samples from one set of time courses (two of each type of virus, four virus types, and four time points) were transcribed at the same time with aliquots of the same master mix of RT enzyme, deoxynucleotide triphosphates, and buffer. For strand-specific priming of the RT reaction, the primers used were 5′-GTAGGCTGGTGAGTAATCT-3′ (primes on genome positions 309 to 291) and 5′-TGATTCCCCGG-ATAGCC-3′ (primes on antigenome positions 201 to 185). For PCRs, 5 μl of RT reaction product was used in a reaction volume of 50 μl. The program was 95°C for 1.5 min followed by the indicated number of cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 50°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 20 s. Genome-specific PCR used primers 5′-GTAATCTCAAGTCTGGATACC-3′ (primes on genome positions 297 to 277) and 5′-AGGATCGGGAAGCAGACA-3′ (corresponds to genome positions 83 to 100). Antigenome-specific PCR primers were 5′-ACCAGACAAAGCTGGGTAAGGA-3′ (corresponds to antigenome positions 1 to 22) and 5′-GCGCCTCGAGCCTGTGCCCTAAGCCT-3′ (primes on antigenome positions 181 to 165). P-gene-specific primers were 5′-CCCAGTGTGATCCGTTC-3′ (corresponds to antigenome positions 3187 to 3203) and 5′-CCTGCAGGAGATCAGCTATGTTGT (primes on antigenome positions 3338 to 3356), and H-gene-specific primers were 5′-CCCGTGGGACCGCAAACT-3′ (corresponds to antigenome positions 8971 to 8988) and 5′-GGCCCTGGTTTATAA-3′ (primes on antigenome positions 9112 to 9126). The actin control primers were BA1 and BA2 (23). Five-microliter samples from each PCR were analyzed in 1.3% agarose gels using 1× Tris-borate-EDTA buffer; gel and buffer contained 0.05 μg of ethidium bromide per ml. The fluorescence of the ethidium bromide-stained DNA was recorded using a Bio-Rad Chemi Doc system, and the peak area for each band (average pixel density per row of pixels multiplied by the number of rows), determined using the QuantityOne software (Bio-Rad), was taken as a measure of the relative amount of PCR product. Where no DNA was visible, the pixel density in the equivalent region was determined. The Chemi Doc system consists of a charge-coupled device camera coupled to a digitizing board, the limited spatial resolution of which accounts for the grainy quality of the resulting images.

Antibodies and immunoprecipitation.

Rabbit antisera recognizing the RPV C protein were raised against bacterially expressed glutathione S-transferase fusion proteins, using the pGEX vector. The rabbit anti-V antiserum was the kind gift of D. Briedis, Department of Microbiology and Immunology, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada. Mouse monoclonal antibody 2-1 recognizing the RPV P protein was the kind gift of M. Sugiyama, Department of Veterinary Public Health, Faculty of Agriculture, Gifu University, Gifu, Japan. For immunoprecipitation studies, cells in six-well plates were infected with rRPV for 2 days, incubated for 1 h in Eagle's medium without methionine or cysteine, and then incubated for 2 h in 0.5 ml of the same medium containing 5 to 10 μCi of PROMIX (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech), a mixture of amino acids containing [35S]methionine and [35S]cysteine. The medium was removed, and the cells were lysed in 0.5 ml of lysis buffer (1% [vol/vol], Nonidet P-40, 50 mM Tris-Cl [pH 7.5], 0.5 M NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 2.5 mM iodoacetamide, 100 ng each of leupeptin, pepstatin, antipain, and chymostatin per ml). The lysate was incubated first with nonimmune rabbit serum and protein A-Sepharose (Amersham-Pharmacia) for 1 to 2 h at 4°C, centrifuged to remove the protein A-Sepharose, and then incubated with the specific antiserum and protein A-Sepharose overnight at 4°C. Immunoprecipitation of P protein was routinely from one-fifth the amount of lysate used from which to immunoprecipitate V or C. Where the primary antibody was a mouse monoclonal antibody, 0.5 μl of rabbit anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (Dakopatts) was added in addition to bind the mouse antibody more efficiently to the protein A. Sepharose pellets were washed, and samples were prepared for sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) as described elsewhere (3). SDS-PAGE was performed using the buffer system of Laemmli (40); gels were fluorographed using sodium salicylate (12).

Digital image processing.

Original gel pictures (autoradiographs or fluorographs) or photomicroscopy transparencies were photographed using a Kodak DCS420 digital camera or scanned with a Linotype-Hell Saphir, transferred to a PowerMac 7500, converted to grey scale and clipped in Adobe Photoshop, laid out and labeled in QuarkXPress, and printed on a Kodak XLS 8600 printer. Gel images from the Chemi Doc system were exported as TIFF files, cropped to the appropriate region, and imported to ClarisDraw for labeling and printing as described above.

RESULTS

Introduction of mutations to abolish the expression of C or V protein.

The three P gene ORFs that are utilized by the virus are illustrated in Fig. 1a. The AUG initiator codon for the P and V proteins has a suboptimal context (C at −3, rather than the preferred A or G [38]); the C ORF starts at the next AUG, 20 bases downstream (Fig. 1b). To abolish C expression, we first changed this latter AUG codon to ACG, this being the only change to that codon that would be silent in the P protein (Fig. 1b). Although the rescued viruses containing this mutation [RPV(CE) and RPV(VCE)] did not express C protein (see below), we were concerned that a reversion could occur through a single point mutation, and RNA viruses have a relatively high mutation rate, making such a reversion possible. In addition, ACG is used as the C′ protein start codon in SeV (15, 29), and so it was possible that some C protein might be expressed from this ACG, even though the next base after the ACG codon in our mutant (C) is the least conducive to such usage (28). We therefore introduced two stop codons into the C ORF (again, with no change to the P protein), in addition to the change in the initiation codon (Fig. 1b), giving rise to recombinant viruses RPV C− and RPV VC−. In fact, no difference was seen in the behavior of viruses with the single change or with both changes to the C ORF, and data on their growth rates in tissue culture were pooled.

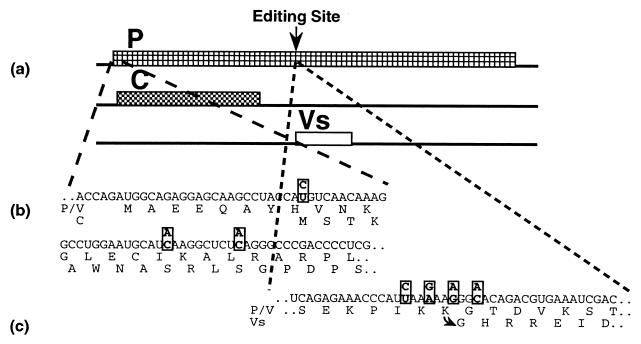

FIG. 1.

Mutations introduced into the P gene of RPV. (a) ORFs used in the RPV P gene. Positions of the ORFs for the P and C proteins are shown, as well as the V protein-specific (Vs) motif accessed by the cotranscriptional insertion of a nontemplated G residue at the editing site (marked). (b) Elimination of expression of the C protein. Sequences of P gene transcripts at the start of the ORFs for the P and V proteins (P/V) and the C protein (C) are shown, along with sequences of the start of the P/V and C proteins. The highlighted bases were changed to the base above, as described in the text. (c) Elimination of cotranscriptional editing and hence expression of the V protein. Sequences of P gene transcripts at the editing site are shown; all four highlighted bases were changed to the base above.

Expression of the RPV V protein requires the nontemplated insertion of an extra G base in the sequence UUAAAAAGGGCACAGA, extending the run of G's from three to four. Although the minimal sequence required for editing has been mapped to only a 24-base section of SeV (49), it is generally assumed that the run of purines followed by the three G's is essential. Four changes were made simultaneously to this motif (Fig. 1c) to ensure that no editing should occur, that no V protein should be made, and that no single mutation could restore V expression. All of the changes were silent in the P ORF.

All of the mutations were made first in a cDNA clone of the P gene, and the C− and V− mutations were combined to make the VC− P gene. The different versions of the P gene were then incorporated into the full-length clone of the RPV genome for rescue into live virus (see Materials and Methods for details). All mutant viruses were rescued without major difficulty, although the double (VCE or VC−) mutants could not be rescued until we had improved the efficiency of our transfection system by changing the transfection reagent from Lipofectin/LipofectACE (1) to FuGENE6 or Transfast (see Materials and Methods), which gave a 12- or 20-fold increase in transfection efficiency. RT-PCR was used to amplify viral RNA from specific regions of the genomes of mutant viruses, and the PCR products were sequenced to confirm the presence of the appropriate mutation. All of the studies reported here were performed on two separately isolated clones of the virus type in question. In addition, although the B95a lymphoblastoid cell line that we used for most of the studies reported here seems to be the best line so far discovered for growing RPV (37), allowing direct culture of wild viruses without adaptation by blind passage, we have noticed that repeated passage of viruses in B95as does increase the rate of replication of RPV in these cells (normally noticeable by about passage 6), and therefore we performed all studies on virus stocks of passage 2 or 3.

Expression of C and V proteins by mutant viruses.

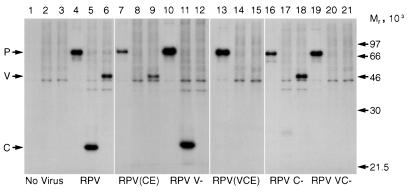

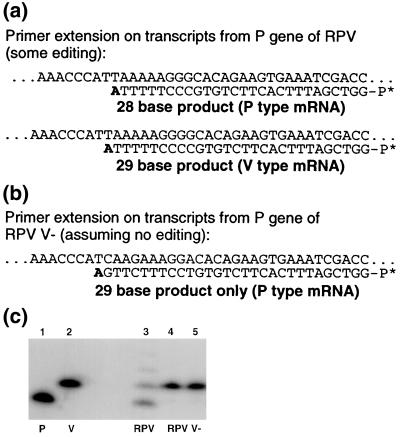

The effectiveness of the introduced mutations in preventing the expression of the C or V protein was assessed by immunoprecipitation of 35S-labeled proteins from lysates of labeled infected cells. As can be seen in Fig. 2, all three P-gene-derived proteins were made in cells infected with ordinary RPV. No C protein was found in cells infected with RPV CE, VCE, C−, or VC−, and no V protein was found in cells infected with RPV V−, VCE, or VC−. To determine if the mutations that we had introduced into the editing site of the P gene had abolished nontemplated base insertion completely, we used a modification of the primer extension technique that we had used previously to examine P gene editing in different strains of the virus (30), in which a labeled primer is extended on isolated mRNA, or PCR products derived from mRNA, until the first A residue is incorporated. As the only source of adenine is ddATP, this terminates extension after only 10 to 12 bases. This technique should show one band for the normal unmodified P gene transcript, with an additional band for transcripts containing an additional base (Fig. 3a). Further bands will be seen for transcripts containing two or more nontemplated bases: such editing events are normally seen, to various extents, in morbilliviruses (5, 10, 30). Due to the mutations introduced into the P gene in order to abolish editing, the predicted size of the primer extension product from the unedited P(V−) gene transcript is one base longer than that from the P gene of the unmutated virus (Fig. 3b). Although editing of transcripts from the P gene of normal RPV could easily be seen (including +2 and +3 bases), there was clearly no editing in viruses containing the V− mutation (Fig. 3c), the single primer extension product being 29 bases long, the same length as the product from the V mRNA cDNA clone.

FIG. 2.

Immunoprecipitation of P, V, and C proteins from B95a cells infected with RPVs. Lysates of labeled infected cells were prepared as described in Materials and Methods from cells infected as indicated at the bottom. Samples of lysates were immunoextracted with mouse monoclonal anti-P protein (lanes 1, 4, 7, 10, 13, 16, and 19), rabbit polyclonal anti-C protein (lanes 2, 5, 8, 11, 14, 17, and 20), or rabbit polyclonal anti-V protein (lanes 3, 6, 9, 12, 15, 18, and 21). Immunoprecipitated proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE on 12% gels, and fluorographs of the gels are shown.

FIG. 3.

Primer extension analysis of editing events in P gene mRNA transcripts. (a) Illustration of how the primer is extended on transcripts from a normal P gene, which will contain three G residues for an exact copy or four (or more) G's if an editing event takes place. P* shows the 5′ label (32P) on the primer. The incorporated ddA base that terminates primer extension is highlighted in bold. (b) As for panel a, but for transcripts from the mutated (V−) P gene. Note that because of a T→C change in the mutated mRNA sequence, the first A is incorporated one base later, so the minimum product from unedited mRNAs is 29 bases. (c) Results from experimental primer extension. Templates used: lane 1, cDNA clone from P type mRNA; lane 2, cDNA clone from V type mRNA; lane 3, RT-PCR product from RPV mRNA; lanes 4 and 5, RT-PCR products from two separate isolates of RPV V−.

Growth of mutant viruses in tissue culture cells.

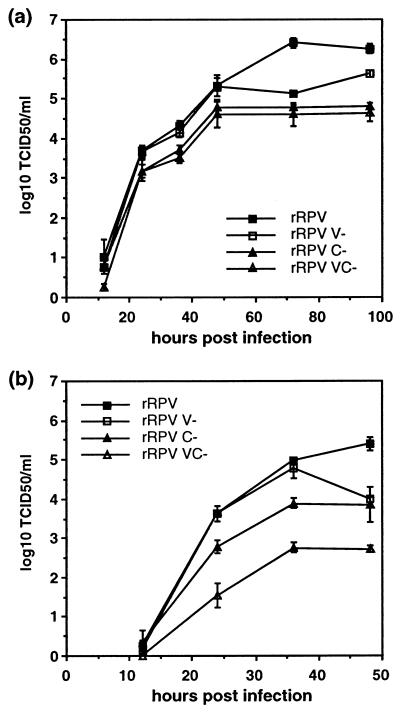

We examined the replication rates of all four virus types in tissue culture using B95a cells, the monkey kidney-derived Vero cell line, or primary bovine skin fibroblasts. Although unmodified RPV could be grown to titers of 106 to 107 TCID50/ml after only a few passages, we found that none of the mutants could be grown in large-scale culture to greater than 105 TCID50/ml, and the double mutant could barely be grown to 104 TCID50/ml. All growth curves therefore had to be multistep, with an initial infection at an MOI of approximately 0.01 to enable all viruses to be used at the same (or nearly the same) infectious dose. In B95as, we found that the initial growth rate of the virus was unaffected by the absence of the V protein, but there was a decrease in the final titer reached (Fig. 4a). In contrast, the initial growth rate of viruses lacking the C protein (RPV C− or RPV VC−) was significantly lower (Fig. 4a). Since the final titer reached is dependent on the relative rates of viral replication and decay (RPV is not particularly stable at 37°C, and newly made virus particles lose infectivity during subsequent culture of the infected cells), it is not surprising that the more slowly growing RPV C− mutants also grew to a lower final titer. Identical results were seen in Vero cells (not shown). In bovine skin fibroblasts, the main difference observed (Fig. 4b) was that the double mutant grew more slowly than that lacking only the C protein, while the RPV V− mutant continued to grow almost identically to the normal RPV. In these cells, it appears that the absence of the V protein is somehow more deleterious to viral replication in the absence of the C protein than in its presence.

FIG. 4.

Growth of mutant viruses in tissue culture. Growth rates of mutant viruses were determined under multistep growth conditions (MOI of ∼0.01) for normal rRPV and the three mutant virus types in B95a cells (a) or primary bovine skin fibroblasts (b). The results from four (a) or two (b) experiments, each with two separate isolates of each virus type, are plotted.

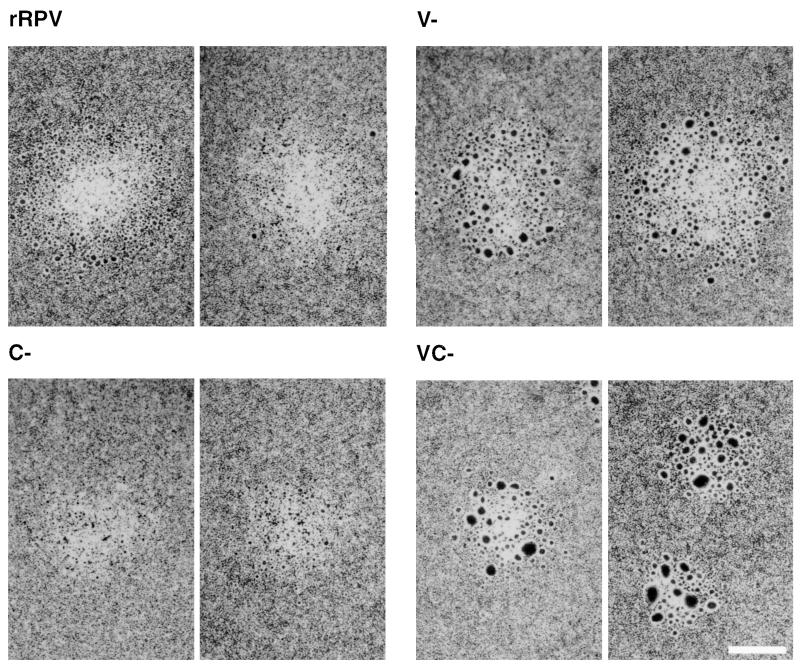

Although the RBOK vaccine strain of RPV is not particularly lytic in cell culture and does not form good plaques, we have found that we can observe the morphology of individual foci of infection by overlaying infected cells with carboxymethyl cellulose and fixing and staining the cells after 5 to 6 days using Giemsa's stain (see Materials and Methods). Examples of the viral foci observed for the four types of virus are shown in Fig. 5: clear differences were seen due to the presence or absence of the individual V or C proteins. Normal RPV shows large areas mostly cleared of cells, with several small syncytia in each infected focus. RPV V− developed similar-size plaques but with many more and larger syncytia, while RPV C− developed plaques similar to those formed by RPV only much smaller, as might be expected from its lower growth rate. The foci of growth of RPV VC− showed both changes, being smaller than normal RPV and having the increased syncytium-forming tendency of RPV V−. The effects of lack of the individual V or C proteins are thus clearly distinct and additive, as both phenotypes are combined when the mutations are combined.

FIG. 5.

Plaque morphology. B95a cells infected with normal RPV or each of the mutant virus types were grown under carboxymethyl cellulose and stained as described in Materials and Methods; individual foci of infection were photographed. Two representative foci of each virus type are shown. Bar = 200 μm.

Effects of defects in V or C expression on synthesis of viral RNAs.

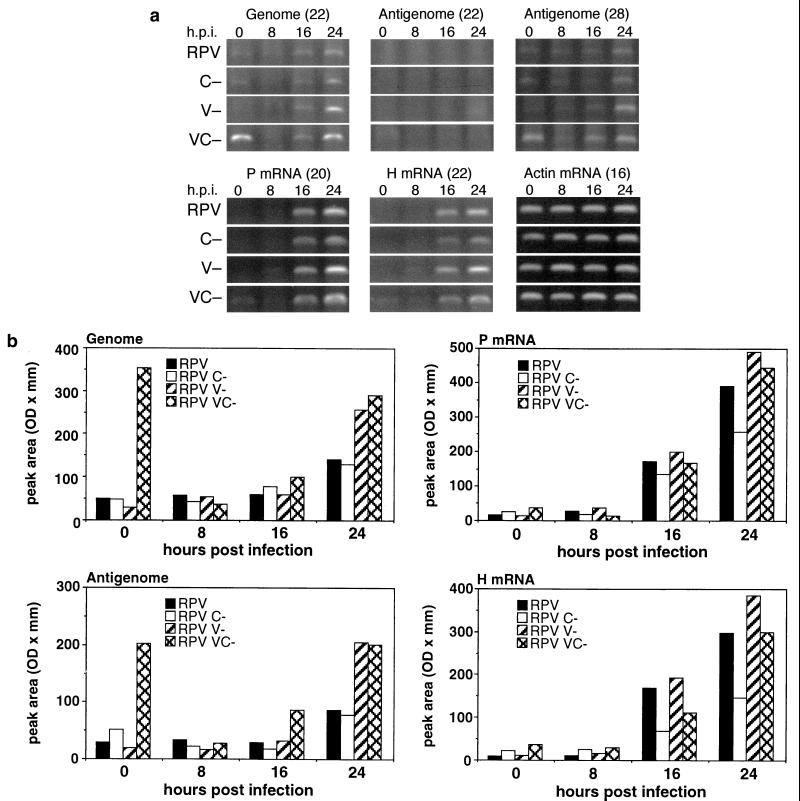

Although the V− mutation had no detectable effect on viral growth rate in tissue culture, it was clear from the above results that this mutation did change the way the virus replicated, inasmuch as the balance between virus-induced cytopathic effect and viral protein-induced cell-cell fusion was altered in viruses carrying this mutation. As we were unable to grow virus to high titer and hence unable to infect at high MOI, we were unable to generate sufficiently strong signals in Northern blots to study the synthesis of viral RNAs at early time points (0 to 24 h postinfection [hpi]) when viral replication is still effectively in single-step mode (growth curves show that new virus is released from cells only at 20 to 24 hpi). We therefore used semiquantitative RT-PCR (35) to compare the four virus types with each other. Initial experiments showed that the amount of PCR product was proportional to the input RNA over a range of about 50-fold, though the optimum number of cycles depended on the maximum and minimum of the range of input RNA concentrations. RNA was isolated from cells infected at an MOI of approximately 0.005 at various times postinfection, and RT reactions were performed with primers specific for mRNA [oligo(dT)], genome sense RNA, or antigenome sense RNA. Primer pairs for PCR amplification of antigenome sequences included one primer from a promoter (non-mRNA) region. The results of these studies are shown in Fig. 6. We used the amplification of actin mRNA as an internal control to show that RNA from the same number of cells was included in each reaction mixture. The actin signal was in the linear range after 15 or 16 cycles, similar to the results found for cells infected with SeV at high MOI (35). To detect the RPV genome, however, 20 to 22 cycles were required, while antigenome amplification required about 28 cycles (Fig. 6). We consistently found less antigenome than genome in infected cells (compare the amounts of PCR product found for genome and antigenome at 22 cycles in Fig. 6a). The number of cycles required for detecting viral mRNAs depended on the gene, since RPV, like all members of the order Mononegavirales, shows a transcription gradient along its genome, with most transcription taking place from the N gene (the nearest to the genome promoter), followed in decreasing amounts by the P, M, F, H, and L genes, in order along the genome (3′ to 5′) (11). This arises, it is thought, because primary interaction of the viral polymerase with the genome can occur only at the genome promoter, and the polymerase has only a finite probability of initiating transcription from any one gene after it has finished transcribing and polyadenylating the previous one. Transcription from either the P gene or the H gene was clearly depressed in the absence of the C protein (compare P or H gene mRNA from RPV with RPV C− and RPV V− with RPV VC in Fig. 6), suggesting that the initiation or extension of viral mRNA transcripts was decreased in these mutants and that the C protein of RPV has a role in these processes.

FIG. 6.

Semiquantitative RT-PCR of viral RNAs. RNA was purified from B95a cells infected with 103.5 TCID50 of normal RPV or the three mutant virus types (C−, V−, and VC−) for 0, 8, 16, and 24 h. Semiquantitative RT-PCR was carried out as described in Materials and Methods for 16 cycles (actin mRNA), 20 cycles (P mRNA), 22 cycles (genome and antigenome RNAs and H mRNA), or 28 cycles (antigenome RNA). The PCR products were analyzed on 1.3% agarose gels, and the amount of PCR product for the viral RNAs was determined by imaging the gels on a Bio-Rad Chemi Doc system. (a) Gel images; (b) quantitation of PCR product for genome, antigenome (from the 28-cycle data), P mRNA, and H mRNA from the images in panel a. The area under a notional plot of fluorescence signal was calculated for each PCR product band after removal of the lane background, and this value was plotted for each time point.

In contrast, levels of genome and antigenome in RPV and RPV C− were indistinguishable (Fig. 6), while mutants lacking the V protein (RPV V− and RPV VC−) clearly showed higher levels of such transcripts at 24 hpi, suggesting either an earlier onset or more rapid rate of replicative transcription in the absence of the V protein. Given these higher amounts of genome RNA, the template for transcription of viral mRNAs, one would expect the V− and VC− mutants to show a correspondingly greater amount of viral mRNAs as well, which is what is observed. However, the increase in mRNA levels seen in the mutants lacking the V protein is less than the corresponding increase in genome RNA levels. The V protein may therefore cause an increase in the general efficiency of mRNA transcription from the viral genome, although it is not clear whether it does so by inhibiting replicative transcription or promoting that of message.

We also observed that most of the time zero samples contained detectable amounts of both genome and antigenome RNAs, presumably derived from the initial inoculum; the time zero samples from RPV VC−-infected cells always contained much more genome and antigenome than any of the others. Given that all experimental wells were infected with the same dose of infectious virus (as measured by TCID50), this suggests that preparations of RPV VC− had far higher amounts of viral RNA, either as intact virus or unenveloped nucleocapsid, per infectious unit than was the case for the other virus types, suggesting in turn a greatly decreased efficiency of incorporation of viral genomes into infectious particles.

DISCUSSION

The V-specific domain of the V protein is conserved among almost all of the paramyxoviruses, although it is not universally expressed, being absent from hPIV1 and hPIV3 (24, 46). This domain has been shown to bind zinc in MV and SV5 (and hence probably in other V proteins) (44, 51) and is responsible for interaction of the MV V protein with several host cell proteins (45); the V proteins of SV5, MV, and hPIV2 (but not SeV) interact with damage-specific DNA binding protein and require this Zn binding domain to be intact in order to do so (43). The P protein itself, on the other hand, especially its amino-terminal half, is poorly conserved (5). Nevertheless, the amino-terminal part of the P protein has been shown to interact specifically with monomeric nucleocapsid protein in SV5 (54), SeV (17, 34), and MV (31), and this property is shared by the V protein. In SeV and the morbilliviruses, insertion of two G's at the editing site gives rise to a third protein called W or R, which is the P protein amino-terminal domain without the V protein zinc binding motif and which also is able to bind monomeric N protein. As can be seen in Fig. 3, a small but detectable amount of R-encoding mRNA is normally produced in RPV. In vitro studies have shown that V protein (or W/R) inhibits viral replication, but not mRNA transcription (13, 17, 34), at least in SeV. The binding of these proteins to N appears to prevent its interaction with the P protein (34), making the N protein unavailable for encapsidation; if one thinks of replication as being divisible into transcription plus encapsidation (13), an increase in available N should increase replication of the genome and antigenome or bring forward the point in the virus replication cycle where sufficient N protein accumulates in the infected cell to allow replicative rather than mRNA transcription to occur. As predicted from these observations, SeV that does not edit its P gene transcripts shows increased genome and antigenome synthesis (35), though this appears to occur only in some cell lines (19, 35). Similarly, increased antigenome accumulation is observed in glioblastoma cells infected with MV V− (though genome levels were not determined in those experiments) (60), and we have shown here that RPV V− (with or without the C protein) shows increased production of both genome and antigenome, i.e., increased transcription of the encapsidated viral RNAs. Although the increased replicative transcription will decrease the transcription of mRNA from any one genome, this may be offset, or more than offset, by the increase in the number of genome templates available. Exactly what final effect there will be on viral mRNA levels and hence on viral protein levels will depend on how efficiently the virus can utilize these templates, which will depend in turn on the general replication machinery of that strain of virus, and also possibly on the availability of host cell proteins necessary for viral transcription, and so on the host cell itself. Hence, a normally virulent strain of SeV shows a large increase in mRNA levels in the absence of V protein (35), while modified versions of the Edmonston vaccine strain of MV (60) and the RBOK vaccine strain of RPV (work presented here) show only a slight increase in mRNA levels when V protein is not expressed. However, given the increased level of genomes observed in our own studies, there is probably a decrease in mRNA production per genome template in RPV V− and RPV VC−. MV V− (in glioblastoma cells) and RPV V− (in lymphoblastoid cells) both show an increase in syncytium formation. This is unlikely to be due simply to a rise in expression of viral glycoproteins due to an increase in viral mRNAs, since the increases seen are small in both cases, but may reflect an additional change in the total cytopathic effect caused by the absence of the V protein which alters the balance among viral assembly, cell death, and cell-cell fusion. This balance is also cell type dependent, as we see syncytium formation easily in RPV-infected B95a cells but rarely in Vero cells.

Both SeV V− and MV V− have been shown to be defective in replication in infected animals (35, 60). This effect has been seen most markedly in the SeV studies (35), since the parental SeV is virulent in mice but the V− form is avirulent, being rapidly cleared from the lungs of infected mice. The RPV strain that is the parent for all of our recombinants is itself avirulent, and so no major effect of the V− mutation would be apparent unless the virus became so attenuated as to no longer form an effective vaccine. However, cattle infected with RPV V− are effectively immunized against lethal challenge (unpublished observations), indicating that any change in in vivo phenotype caused by the absence of V protein expression is masked by the preexisting attenuation of the virus.

The C proteins of the Sendai group of paramyxoviruses and those of the morbilliviruses are not conserved as to sequence and therefore cannot be assumed to have the same function in the viral life cycle. SeV C proteins have been shown to suppress mRNA transcription (16), and in general transcription from the genome promoter (9), possibly through the interaction of the C protein with the viral L protein (33). As predicted, SeV defective in expression of either of the first C proteins (C′ or C) showed increased viral mRNA levels (41); however, abolition of expression of both C′ and C leads to a slow-growing virus with decreased viral RNA levels (39, 41). SeV that expresses no proteins from the C ORF (no C′, C, Y1, or Y2) is almost nonviable (39).

Much less is known about the morbillivirus C protein. Like the SeV C proteins (67), it colocalizes with viral N, P, and L proteins in infected cells (6; M. D. Baron, unpublished data), suggesting that it is involved in some way with viral RNA transcription. MV and RPV which express no C protein are reasonably viable in most cell lines tested (references 21 and 53 and work presented here), unlike SeV. MV C− grows normally in Vero cells but very poorly in peripheral blood leukocytes (21, 53); in the latter, levels of MV viral genome and N mRNA are both reduced in the absence of the C protein. RPV C− is defective in growth in B95a, Vero, and primary bovine skin fibroblasts; genome and antigenome accumulation are like that of the parental virus, but there is a clear effect of the absence of the C protein on mRNA transcription, suggesting that the C protein may play a role in initiation, extension, or termination of mRNA transcription.

A noticeable feature of the data obtained with some of the new recombinant paramyxoviruses is how dependent the phenotype of mutations is on the host cell involved. In primary bovine skin fibroblasts, we found that the double mutant (VC−) grew more slowly than RPV C−, although both virus types grew at the same rate in Vero and B95a cells. The fibroblasts are slightly poorer hosts for RPV than Vero cells, as judged by the titer that RPV grows to in these cells (Fig. 4), and it may be that they lack some necessary host cell protein or have an excess of some inhibitory protein that particularly exacerbates the problems caused by the great overproduction of viral genomes relative to viral envelope proteins in the VC− virus type. The role of host cell proteins in morbillivirus replication remains relatively unexplored. In vitro, tubulin has been shown to be required for MV transcription (47), and a number of host cell proteins have been shown to bind to the MV V and C proteins (45), including the binding of damage-specific DNA binding protein to the V protein (43). One of the heat shock proteins (hsp72) appears to be a necessary part of the replication complex in canine distemper virus (48), and yet other host cell proteins have been shown to bind specifically to the promoter regions of MV (42). Clearly further information as to the nature of these host cell proteins and their distribution and availability in different cell types will be required in order to interpret the cell-type-specific phenotypes of various virus mutations.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baron M D, Barrett T. Rescue of rinderpest virus from cloned cDNA. J Virol. 1997;71:1265–1271. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.2.1265-1271.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baron M D, Foster-Cuevas M, Baron J, Barrett T. Expression in cattle of epitopes of a heterologous virus using a recombinant rinderpest virus. J Gen Virol. 1999;80:2031–2039. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-8-2031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baron M D, Garoff H. Mannosidase II and the 135kDa Golgi-specific antigen recognised by monoclonal antibody 53FC3 are the same dimeric protein. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:19928–19931. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baron M D, Goatley L, Barrett T. Cloning and sequence analysis of the matrix (M) protein gene of rinderpest virus and evidence for another bovine morbillivirus. Virology. 1994;200:121–129. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baron M D, Shaila M S, Barrett T. Cloning and sequence analysis of the phosphoprotein gene of rinderpest virus. J Gen Virol. 1993;74:299–304. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-74-2-299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bellini W J, Englund G, Rozenblatt S, Arnheiter H, Richardson C D. Measles virus P gene codes for two proteins. J Virol. 1985;53:908–919. doi: 10.1128/jvi.53.3.908-919.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berg M, Hjertner B, Moreno-Lopez J, Linné T. The P gene of the porcine paramyxovirus LPMV encodes three possible polypeptides P, V and C: the P protein mRNA is edited. J Gen Virol. 1992;73:1195–1200. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-73-5-1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boeck R, Curran J, Matsuoka Y, Compans R, Kolakofsky D. The parainfluenza virus type 1 P/C gene uses a very efficient GUG codon to start its C′ protein. J Virol. 1992;66:1765–1768. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.3.1765-1768.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cadd T, Garcin D, Tapparel C, Itoh M, Homma M, Roux L, Curran J, Kolakofsky D. The Sendai paramyxovirus accessory C proteins inhibit viral genome amplification in a promoter-specific fashion. J Virol. 1996;70:5067–5074. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.8.5067-5074.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cattaneo R, Kaelin K, Baczko K, Billeter M A. Measles virus editing provides an additional cysteine-rich protein. Cell. 1989;56:759–764. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90679-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cattaneo R, Rebmann G, Schmid A, Bazko K, Meulen V T, Billeter M. Altered transcription of a defective measles virus genome derived from a diseased human brain. EMBO J. 1987;6:681–688. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb04808.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chamberlain J P. Fluorographic detection of radioactivity in polyacrylamide gels with water-soluble fluor, sodium salicylate. Anal Biochem. 1979;98:132–135. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(79)90716-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Curran J, Boeck R, Kolakofsky D. The Sendai virus P gene expresses both an essential protein and an inhibitor of RNA synthesis by shuffling modules via mRNA editing. EMBO J. 1991;10:3079–3085. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07860.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Curran J, de Melo M, Moyer S, Kolakofsky D. Characterisation of the Sendai virus V protein with an anti-peptide antiserum. Virology. 1991;184:108–116. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90827-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Curran J, Kolakofsky D. Ribosomal initiation from an ACG codon in the Sendai virus P/C mRNA. EMBO J. 1988;10:3079–3085. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb02806.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Curran J, Marq J B, Kolakofsky D. The Sendai virus nonstructural C proteins specifically inhibit viral messenger-RNA synthesis. Virology. 1992;189:647–656. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90588-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Curran J, Pelet T, Kolakofsky D. An acidic activation-like domain of the Sendai virus P protein is required for RNA synthesis and encapsidation. Virology. 1994;202:875–884. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Delenda C, Hausmann S, Garcin D, Kolakofsky D. Normal cellular replication of Sendai virus without the trans-frame, nonstructural V protein. Virology. 1997;228:55–62. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.8354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Delenda C, Taylor G, Hausmann S, Garcin D, Kolakofsky D. Sendai viruses with altered P, V, and W protein expression. Virology. 1998;242:237–337. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Deng W P, Nickoloff J A. Site-directed mutagenesis of virtually any plasmid by eliminating a unique site. Anal Biochem. 1992;200:81–88. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(92)90280-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Escoffier C, Manié S, Vincent S, Muller C P, Billeter M A, Gerlier D. Nonstructural C protein is required for efficient measles virus replication in human peripheral blood cells. J Virol. 1999;73:1695–1698. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.2.1695-1698.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Food and Agriculture Organization. Prevention and control of transboundary animal diseases. Report of the FAO expert consultation on the emergency prevention system (EMPRES) for transboundary animal and plant pests and diseases (livestock diseases programme) including the blueproint for global rinderpest eradication. FAO Animal Products Health Paper 133. Rome, Italy: Food and Agriculture Organization; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Forsyth M A, Barrett T. Evaluation of polymerase chain reaction for the detection and characterization of rinderpest and peste des petits ruminants viruses for epidemiologic studies. Virus Res. 1995;39:151–163. doi: 10.1016/0168-1702(95)00076-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Galinski M S, Troy R M, Banerjee A K. RNA editing in the phosphoprotein gene of the human parainfluenza virus type 3. Virology. 1992;186:543–550. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90020-P. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garcin D, Itoh M, Kolakofsky D. A point mutation in the Sendai virus accessory C proteins attenuates virulence for mice, but not virus growth in cell culture. Virology. 1997;238:424–431. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Giorgi C, Blumberg B M, Kolakofsky D. Sendai virus contains overlapping genes expressed from a single mRNA. Cell. 1983;35:829–836. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90115-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gombart A F, Hirano A, Wong T W. Expression and properties of the V protein in acute measles virus and subacute sclerosing panencephalitis virus strains. Virus Res. 1992;25:63–78. doi: 10.1016/0168-1702(92)90100-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grünert S, Jackson R J. The immediate downstream codon strongly influences the efficiency of utilization of eukaryotic translation initiation codons. EMBO J. 1994;13:3618–3630. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06669.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gupta K C, Patwardhan S. ACG, the initiator codon for Sendai virus C protein. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:8553–8556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haas L, Baron M D, Liess B, Barrett T. Editing of morbillivirus P gene transcripts in infected animals. Vet Microbiol. 1995;44:299–306. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(95)00024-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harty R N, Palese P. Measles virus phosphoprotein (P) requires the NH2-terminal and COOH-terminal domains for interactions with the nucleoprotein (N) but only the COOH terminus for interactions with itself. J Gen Virol. 1995;76:2863–2867. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-76-11-2863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Higuchi R, Krummel B, Saiki R K. A general method of in vitro preparation and specific mutagenesis of DNA fragments: study of protein and DNA interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:7351–7367. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.15.7351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Horikami S M, Hector R E, Smallwood S, Moyer S A. The Sendai virus C protein binds the L polymerase protein to inhibit viral RNA synthesis. Virology. 1997;235:261–270. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Horikami S M, Smallwood S, Moyer S A. The Sendai virus V protein interacts with the NP protein to regulate viral genome RNA replication. Virology. 1996;222:383–390. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kato A, Kiyotani K, Sakai Y, Yoshida T, Nagai Y. The paramyxovirus, Sendai virus, V protein encodes a luxury function required for viral pathogenesis. EMBO J. 1997;16:578–587. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.3.578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kato A, Kiyotani K, Sakai Y, Yoshida T, Shioda T, Nagai Y. Importance of the cysteine-rich carboxyl-terminal half of V protein for Sendai virus pathogenesis. J Virol. 1997;71:7266–7272. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.10.7266-7272.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kobune F, Sakata H, Sugiyama M, Sugiura A. B95a, a marmoset lymphoblastoid cell line, as a sensitive host for rinderpest virus. J Gen Virol. 1991;72:687–692. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-72-3-687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kozak M. Compilation and analysis of sequences upstream from the translational start site in eukaryotic mRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:857–72. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.2.857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kurotani A, Kiyotani K, Kato A, Shioda T, Sakai Y, Mizumoto K, Yoshida T, Nagai Y. Sendai virus C proteins are categorically nonessential gene products but silencing their expression severely impairs viral replication and pathogenesis. Genes Cell. 1998;3:111–124. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.1998.00170.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Latorre P, Cadd T, Itoh M, Curran J, Kolakofsky D. The various Sendai virus C proteins are not functionally equivalent and exert both positive and negative effects on viral RNA accumulation during the course of infection. J Virol. 1998;72:5984–5993. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.7.5984-5993.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Leopardi R, Hukkanen V, Vainionpaa R, Salmi A A. Cell proteins bind to sites within the 3′ noncoding region and the positive-strand leader sequence of measles virus RNA. J Virol. 1993;67:785–790. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.2.785-790.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lin G Y, Paterson R G, Richardson C D, Lamb R A. The V protein of paramyxovirus SV5 interacts with damage-specific DNA binding protein. Virology. 1998;249:189–200. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liston P, Briedis D J. Measles virus V protein binds zinc. Virology. 1994;198:399–404. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liston P, Diflumeri C, Briedis D J. Protein interactions entered into by the measles virus P proteins, V proteins, and C proteins. Virus Res. 1995;38:241–259. doi: 10.1016/0168-1702(95)00067-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Matsuoka Y, Curran J, Pelet T, Kolakofsky D, Ray R, Compans R W. The P gene of human parainfluenza virus type 1 encodes P and C proteins but not a cyteine-rich V protein. J Virol. 1991;65:3406–3410. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.6.3406-3410.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moyer S A, Baker S C, Horikami S M. Host cell proteins required for measles virus reproduction. J Gen Virol. 1990;71:775–783. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-71-4-775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Oglesbee M J, Liu Z, Kenney H, Brooks C L. The highly inducible member of the 70kDa family of heat shock proteins increases canine distemper virus polymerase activity. J Gen Virol. 1996;77:2125–2135. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-77-9-2125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Park K H, Krystal M. In vivo model for pseudo-templated transcription in Sendai virus. J Virol. 1992;66:7033–7039. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.12.7033-7039.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Paterson R G, Lamb R A. RNA editing by G-nucleotide insertion in mumps virus P-gene mRNA transcripts. J Virol. 1990;64:4137–4145. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.9.4137-4145.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Paterson R G, Leser G P, Shaughnessy M A, Lamb R A. The paramyxovirus SV5 V protein binds two atoms of zinc and is a structural component of virions. Virology. 1995;208:121–131. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Precious B, Young D F, Bermingham A, Fearns R, Ryan M, Randall R E. Inducible expression of the P, V, and NP genes of the paramyxovirus simian virus 5 in cell lines and an examination of NP-P and NP-V interactions. J Virol. 1995;69:8001–8010. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.12.8001-8010.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Radecke F, Billeter M A. The nonstructural C protein is not essential for multiplication of Edmonston B strain measles virus in cultured cells. Virology. 1996;217:418–421. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Randall R E, Bermingham A. NP:P and NP:V interactions of the paramyxovirus simian virus 5 examined using a novel protein:protein capture assay. Virology. 1996;224:121–129. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shioda T, Hidaka Y, Kanda T, Shibuta H, Nomoto A, Iwasaki K. Sequence of 3,687 nucleotides from the 3′ end of Sendai virus genome RNA and the predicted amino acid sequences of viral ND protein, P protein and C protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 1983;11:7317–7330. doi: 10.1093/nar/11.21.7317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Takeuchi K, Tanabayashi K, Hishiyama M, Yamada Y K, Yamada A, Sugiura A. Detection and characterization of mumps virus V protein. Virology. 1990;178:247–253. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90400-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tapparel C, Hausmann S, Pelet T, Curran J, Kolakofsky D, Roux L. Inhibition of Sendai virus genome replication due to promoter-increased selectivity: a possible role for the accessory C proteins. J Virol. 1997;71:9588–9599. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.12.9588-9599.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Taylor W P. Epidemiology and control of rinderpest. Rev Sci Tech Off Int Epizoot. 1986;5:407–410. doi: 10.20506/rst.5.2.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Thomas S M, Lamb R A, Paterson R G. Two mRNAs that differ by two nontemplated nucleotides encode the amino coterminal proteins P and V of the paramyxovirus SV5. Cell. 1988;54:891–902. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(88)91285-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tober C, Seufert M, Schneider H, Billeter M A, Johnston I C D, Niewiesk S, ter Meulen V, Schneider-Schaulies S. Expression of measles virus V protein is associated with pathogenicity and control of viral RNA synthesis. J Virol. 1998;72:8124–8132. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.10.8124-8132.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vidal S, Curran J, Kolakofsky D. Editing of the Sendai virus P/C mRNA by G insertion occurs during mRNA synthesis via a virus-encoded activity. J Virol. 1990;64:239–246. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.1.239-246.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Vidal S, Curran J, Kolakofsky D. A stuttering model for paramyxovirus P mRNA editing. EMBO J. 1990;9:2017–2022. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08330.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Walsh, E. P., M. D. Baron, J. Anderson, and T. Barrett. Development of a genetically marked recombinant rinderpest vaccine expressing green fluorescent protein J. Gen. Virol., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 64.Wamwayi H, Fleming M, Barrett T. Characterisation of African isolates of rinderpest virus. Vet Microbiol. 1995;44:151–163. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(95)00008-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wardrop E A, Briedis D J. Characterization of V protein in measles virus-infected cells. J Virol. 1991;65:3421–3428. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.7.3421-3428.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Watanabe N, Kawano M, Tsurudome M, Kusagawa S, Nishio M, Komada H, Shima T, Ito Y. Identification of the sequences responsible for the nuclear targeting of the V protein of human parainfluenza virus type 2. J Gen Virol. 1996;77:327–338. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-77-2-327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yamada H, Hayata S, Omata-Yamada T, Taira H, Mizumoto K, Iwasaki K. Association of the Sendai virus C protein with nucleocapsids. Arch Virol. 1990;113:245–253. doi: 10.1007/BF01316677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]