Definitions and terms

Complementary medicine refers to a group of therapeutic and diagnostic disciplines that exist largely outside the institutions where conventional health care is taught and provided. Complementary medicine is an increasing feature of healthcare practice, but considerable confusion remains about what exactly it is and what position the disciplines included under this term should hold in relation to conventional medicine

In the 1970s and 1980s these disciplines were mainly provided as an alternative to conventional health care and hence became known collectively as “alternative medicine.” The name “complementary medicine” developed as the two systems began to be used alongside (to “complement”) each other. Over the years, “complementary” has changed from describing this relation between unconventional healthcare disciplines and conventional care to defining the group of disciplines itself. Some authorities use the term “unconventional medicine” synonymously. This changing and overlapping terminology may explain some of the confusion that surrounds the subject.

Common complementary therapies

| • Acupressure | • Chiropractic* | • Naturopathy |

| • Acupuncture* | • Cranial osteopathy | • Nutritional therapy* |

| • Alexander | • Environmental | • Osteopathy* |

| technique | medicine | • Reflexology* |

| • Applied kinesiology | • Healing | • Reiki |

| • Anthroposophic medicine | • Herbal medicine* | • Relaxation and |

| • Aromatherapy* | • Homoeopathy* | visualisation* |

| • Autogenic training | • Hypnosis* | • Shiatsu |

| • Ayurveda | • Massage* | • Therapeutic touch |

| • Meditation* | • Yoga* | |

| *Considered in detail in later articles |

Definition of complementary medicine adopted by Cochrane Collaboration

“Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) is a broad domain of healing resources that encompasses all health systems, modalities, and practices and their accompanying theories and beliefs, other than those intrinsic to the politically dominant health system of a particular society or culture in a given historical period. CAM includes all such practices and ideas self-defined by their users as preventing or treating illness or promoting health and well-being. Boundaries within CAM and between the CAM domain and that of the dominant system are not always sharp or fixed.”

We use the term complementary medicine to describe healthcare practices such as those listed in the box. We use it synonymously with the terms “complementary therapies” and “complementary and alternative medicine” found in other texts, according to the definition used by the Cochrane Collaboration.

Which disciplines are complementary?

Our list is not exhaustive, and new branches of established disciplines are continually being developed. Also, what is thought to be conventional varies between countries and changes over time. The boundary between complementary and conventional medicine is therefore blurred and constantly shifting. For example, although osteopathy and chiropractic are still generally considered complementary therapies in Britain, they are included as part of standard care in guidelines from conventional bodies such as the Royal College of General Practitioners.

Unhelpful assumptions about complementary medicine

| “Non-statutory—not provided by the NHS” | “Natural” | “Unproved” |

| • Complementary medicine is increasingly available on the NHS | • Good conventional medicine also involves rehabilitation with, say, rest, exercise, or diet | • There is a growing body of evidence that certain complementary therapies are effective in certain clinical conditions |

| • 39% of general practices provide access to complementary medicine for NHS patients | • Complementary medicine may involve unnatural practices such as injecting mistletoe or inserting needles into the skin | • Many conventional healthcare practices are not supported by the results of controlled clinical trials |

| “Unregulated—therapists not regulated by state legislation” | “Holistic—treats the whole person” | “Irrational—no scientific basis” |

| • Osteopaths and chiropractors are now state registered and regulated, and other disciplines will probably soon follow | • Many conventional healthcare professionals work in a holistic manner | • Scientific research is starting to uncover the mechanisms of some complementary therapies, such as acupuncture and hypnosis |

| • Substantial amount of complementary medicine is delivered by conventional health professionals | • Complementary therapists can be narrow and reductionist in their approach | “Harmless” |

| “Unconventional—not taught in medical schools” | • Holism relates more to outlook of practitioner than to the type of medicine practised | • There are reports of serious adverse effects associated with using complementary medicine |

| • Disciplines such as physiotherapy and chiropody are also not taught in medical schools | “Alternative” | |

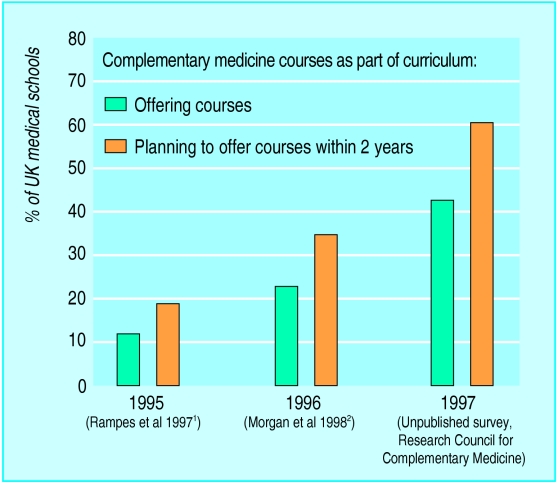

| • Some medical schools have a complementary medicine component as part of the curriculum | • Implies use instead of conventional treatment | |

| • Most users of complementary medicine seem not to have abandoned conventional medicine | ||

The wide range of disciplines classified as complementary medicine makes it difficult to find defining criteria that are common to all. Many of the assumptions made about complementary medicine are oversimplistic generalisations.

Organisational structure

Historical development

Since the inception of the NHS, the public sector has supported training, regulation, research, and practice in conventional health care. The recent development of complementary medicine has taken place largely in the private sector. Until recently, most complementary practitioners trained in small, privately funded colleges and then worked independently in relative isolation from other practitioners.

Factors limiting research in complementary medicine

Lack of funding—In 1995 only 0.08% of NHS research funds were spent on complementary medicine. Many funding bodies have been reluctant to give grants for research in complementary medicine. Pharmaceutical companies have little commercial interest in researching complementary medicine

Lack of research skills—Complementary practitioners usually have no training in critical evaluation of existing research or practical research skills

Lack of an academic infrastructure—This means limited access to computer and library facilities, statistical support, academic supervision, and university research grants

Insufficient patient numbers—Individual list sizes are small, and most practitioners have no disease “specialty” and therefore see very small numbers of patients with the same clinical condition. Recruiting patients into studies is difficult in private practice

Difficulty undertaking and interpreting systematic reviews—Many poor quality studies make interpretation of results difficult. Many publications in complementary medicine are not on standard databases such as Medline. Many different types of treatment exist within each complementary discipline (for example, formula, individualised, electro, laser, and auricular acupuncture)

Methodological issues—Responses to treatment are unpredictable and individual, and treatment is usually not standardised. Designing appropriate controls for some complementary therapies (such as acupuncture, manipulation) is difficult, as is blinding patients to treatment allocation. Allowing for the role of the therapeutic relationship also creates problems

Research

More complementary medical research exists than is commonly recognised—the Cochrane Library lists over 4000 randomised trials—but the field is still poorly researched compared with conventional medicine. There are several reasons for this, some of which also apply to conventional disciplines like occupational and speech therapy. However, complementary practitioners are increasingly aware of the value of research, and many complementary training courses now include research skills. Conventional sources of funding, such as the NHS research and development programme and major cancer charities, have become more open to complementary researchers.

Training

Although complementary practitioners (other than osteopaths and chiropractors) can legally practise without any training whatsoever, most have completed some further education in their chosen discipline.

There is great variation in the many training institutions. For the major therapies—osteopathy, chiropractic, acupuncture, herbal medicine, and homoeopathy—these tend to be highly developed, some with university affiliation, degree level exams, and external assessment. Others, particularly those teaching less invasive therapies such as reflexology and aromatherapy, tend to be small and isolated, determine curricula internally, and have idiosyncratic assessment procedures. In some courses direct clinical contact is limited. Some are not recognised by the main registering bodies in the relevant discipline. Most complementary practitioners finance their training without state support, and many train part time over several years.

Conventional healthcare practitioners such as nurses and doctors often have their own separate training courses in complementary medicine.

Regulation

Apart from osteopaths and chiropractors, complementary practitioners are not obliged to join any official register before setting up in practice. However, many practitioners are now members of appropriate registering or accrediting bodies. There are between 150 and 300 such organisations, with varying membership size and professional standards. Some complementary disciplines have as many as 50 registering organisations, all with different criteria and standards.

Recognising that this situation is unsatisfactory, many disciplines are taking steps to become unified under one regulatory body per discipline. Such bodies should, as a minimum, have published criteria for entry, established codes of conduct, complaints procedures, and disciplinary sanctions and should require members to be fully insured.

The General Osteopathic Council and General Chiropractic Council have been established by acts of parliament and have statutory self regulatory status and similar powers and functions to those of the General Medical Council. A small number of other disciplines—such as acupuncture, herbal medicine, and homoeopathy—have a single main regulatory body and are working towards statutory self regulation.

Efficient regulation of the “less invasive” complementary therapies such as massage or relaxation therapies is equally important. However, statutory regulation, with its requirements for parliamentary legislation and expensive bureaucratic procedures, may not be feasible. Legal and ethics experts argue that unified and efficient voluntary self regulatory bodies that fulfil the minimum standards listed above should be sufficient to safeguard patients. It will be some years before even this is achieved across the board.

Approaches to treatment

The approaches used by different complementary practitioners have some common features. Although they are not shared by all complementary disciplines, and some apply to conventional disciplines as well, understanding them may help to make sense of patients’ experiences of complementary medicine.

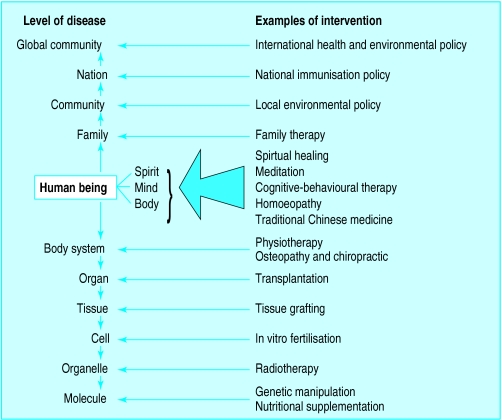

The holistic approach

Many, but not all, complementary practitioners have a multifactorial and multilevel view of human illness. Disease is thought to result from disturbances at a combination of physical, psychological, social, and spiritual levels. The body’s capacity for self repair, given appropriate conditions, is emphasised.

Example of a holistic approach—Rudolph Steiner’s central tenets of anthroposophy

Each individual is unique

Scientific, artistic, and spiritual insights may need to be applied together to restore health

Life has meaning and purpose—the loss of this sense may lead to a deterioration in health

Illness may provide opportunities for positive change and a new balance in our lives

According to most complementary practitioners, the purpose of therapeutic intervention is to restore balance and facilitate the body’s own healing responses rather than to target individual disease processes or stop troublesome symptoms. They may therefore prescribe a package of care, which could include modification of lifestyle, dietary change, and exercise as well as a specific treatment. Thus, a medical herbalist may give counselling, an exercise regimen, guidance on breathing and relaxation, dietary advice, and a herbal prescription.

It should be stressed that this holistic approach is not unique to complementary practice. Good conventional general practice, for example, follows similar principles.

Use of unfamiliar terms and ideas

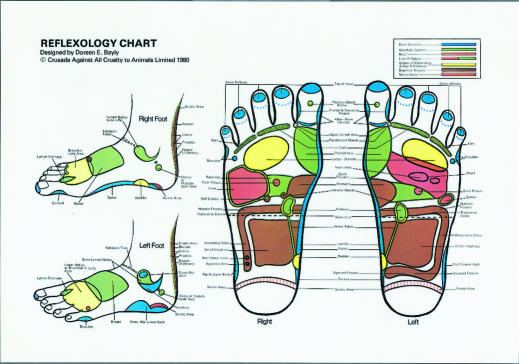

Complementary practitioners often use terms and ideas that are not easily translated into Western scientific language. For example, neither the reflex zones manipulated in reflexology nor the “Qi energy” fundamental to traditional Chinese medicine have any known anatomical or physiological correlates.

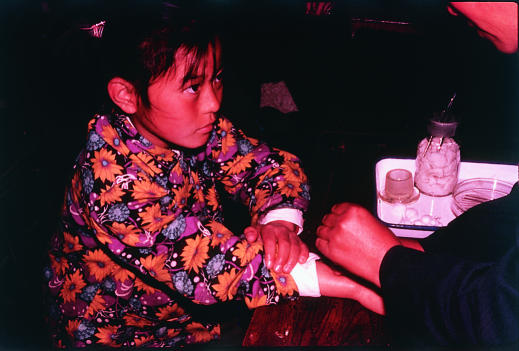

Sometimes familiar terms are used but with a different meaning: acupuncturists may talk of “taking the pulse,” but they will be assessing characteristics such as “wiriness” or “slipperiness,” which have no Western equivalent. It is important not to interpret terms used in complementary medicine too literally and to understand that they are sometimes used metaphorically or as a shorthand for signs, symptoms, and syndromes that are not recognised in conventional medicine.

Different categorisation of illness

Complementary and conventional practitioners often have very different methods of assessing and diagnosing patients. Thus, a patient’s condition may be described as “deficient liver Qi” by a traditional acupuncturist, a “pulsatilla constitution” by a homoeopath, and “a peptic ulcer” by a conventional doctor. In each case the way the problem is diagnosed determines the treatment given.

Confusingly, there is little correlation between the different diagnostic systems: some patients with deficient liver Qi do not have ulcers, and some ulcer patients do not have deficient liver Qi but another traditional Chinese diagnosis. This causes problems when comparing complementary and conventional treatments in defined patient groups.

Sources of information on healing

National Federation of Spiritual Healers (NFSH)

Largest professional registering body

Old Manor Farm Studio, Church Street, Sunbury on Thames, Middlesex TW16 6RG. Tel: 01932 783164. Fax: 01932 779648. URL: www.nfsh.org.uk

Confederation of Healing Organisations (CHO)

Umbrella organisation for registering bodies in healing

Suite J, Second Floor, The Red and White House, 113 High Street, Berkhamsted HP4 2DJ. Tel: 01442 870660

Publications

Benor D. Healing research. Vols 1-4. Deddington: Helix Editions, 1992 Review of collected research on healing

Brown C. Optimum healing. London: Rider, 1998 Description of a general practitioner’s experience and use of healing

It should be stressed that the lack of a shared world view is not necessarily a barrier to effective cooperation. For example, doctors work closely alongside hospital chaplains and social workers, each regarding the others as valued members of the healthcare team.

Approaches to learning and teaching

Complementary practitioners are not generally concerned with understanding the basic scientific mechanism of their particular therapy. Their knowledge base is often derived from a tradition of clinical observation and treatment decisions are usually empirical. Sometimes traditional teachings are handed down in a way that discourages questioning and evolution of practice, or encourages reliance on their own and others’ individual anecdotal clinical and intuitive experience.

Conclusion

It is obvious from this discussion that complementary medicine is a heterogeneous subject. It is unlikely that all complementary disciplines will have an equal impact on UK health practices. The individual complementary therapies with the most immediate relevance to the medical profession are reviewed in detail in later articles, but some disciplines are inevitably beyond the scope of this series—most notably those related to healing— and interested readers should consult texts listed in the boxes.

Further reading

Ernst E. Complementary medicine: a critical appraisal. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann, 1996

Lewith G, Kenyon J, Lewis P. Complementary medicine: an integrated approach. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996 (Oxford General Practice Series)

Vickers AJ, ed. Examining complementary medicine. Cheltenham: Stanley Thornes, 1998

Vincent C, Furnham A. Complementary medicine: a research perspective. London: Wiley, 1997

Woodham A, Peters D. An encyclopaedia of complementary medicine. London: Dorling Kindersley, 1997

Figure.

Numbers of medical schools offering or planning to offer courses on complementary medicine as part of the curriculum

Figure.

The General Osteopathic Council and General Chiropractic Council have been established by acts of parliament to regulate their respective disciplines

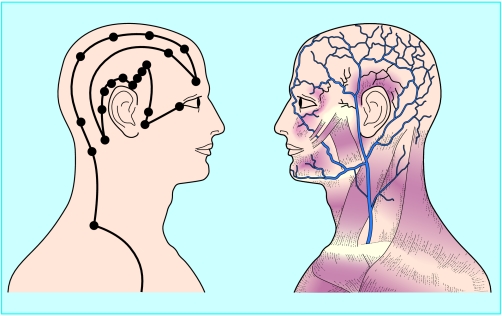

Figure.

There are multiple levels of disease and, therefore, multiple levels at which therapeutic interventions can be made

Figure.

In reflexology areas of the foot are believed to correspond to the organs or structures of the body

Figure.

Acupuncturists may “take a patient’s pulse,” but they assess characteristics such as “wiriness” or “slipperiness”

Acknowledgments

The picture of manipulative therapy is reproduced with permission of BMJ/Ulrike Preuss. The reflexology foot chart is reproduced with permission of the International Institute of Reflexology and the Crusade Against All Cruelty to Animals. The picture of a Chinese acupuncturist taking a pulse is reproduced with permission of Rex/SIPA Press.

Footnotes

The ABC of complementary medicine is edited and written by Catherine Zollman and Andrew Vickers. Catherine Zollman is a general practitioner in Bristol, and Andrew Vickers will shortly take up a post at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, New York. At the time of writing, both worked for the Research Council for Complementary Medicine, London. The series will be published as a book in Spring 2000.

References

- Rampes H, Sharples F, Maragh S, Fisher P. Introducing complementary medicine into the medical curriculum. J R Soc Med. 1997;90:19–22. doi: 10.1177/014107689709000107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan D, Glanville H, Mars S, Nathanson V. Education and training in complementary and alternative medicine: a postal survey of UK universities, medical schools and faculties of nurse education. Complementary Ther Med. 1998;6:64–70. [Google Scholar]