Abstract

Xenogeneic sources of collagen type I remain a common choice for regenerative medicine applications due to ease of availability. Human and animal sources have some similarities, but small variations in amino acid composition can influence the physical properties of collagen, cellular response, and tissue remodeling. The goal of this work is to compare human collagen type I-based hydrogels versus animal-derived collagen type I-based hydrogels, generated from commercially available products, for their physico-chemical properties and for tissue engineering and regenerative medicine applications. Specifically, we evaluated whether the native human skin type I collagen could be used in the three most common research applications of this protein: as a substrate for attachment and proliferation of conventional 2D cell culture; as a source of matrix for a 3D cell culture; and as a source of matrix for tissue engineering. Results showed that species and tissue specific variations of collagen sources significantly impact the physical, chemical, and biological properties of collagen hydrogels including gelation kinetics, swelling ratio, collagen fiber morphology, compressive modulus, stability, and metabolic activity of hMSCs. Tumor constructs formulated with human skin collagen showed a differential response to chemotherapy agents compared to rat tail collagen. Human skin collagen performed comparably to rat tail collagen and enabled assembly of perfused human vessels in vivo. Despite differences in collagen manufacturing methods and supplied forms, the results suggest that commercially available human collagen can be used in lieu of xenogeneic sources to create functional scaffolds, but not all sources of human collagen behave similarly. These factors must be considered in the development of 3D tissues for drug screening and regenerative medicine applications.

Keywords: 3D construct, cancer modeling, collagen type I, hydrogel, xeno

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Tissue engineering, whether to create three-dimensional model systems such as organoids or generate replacement organs for transplantation, involves the use of isolated cell types and extracellular matrix (ECM) components.1 Collagen type I, the major protein constituent of most ECM, is a common choice in regenerative medicine research and often isolated from tendon, cartilage, bone, or skin tissues.2,3 Currently, most applications start with commercially available products and most commercially available sources of collagen type I for both research and clinical applications are derived from animal tissues which include bovine, porcine, rat, and fish. While only a few studies have investigated the inherent chemical and physical differences of collagen type I across different tissue sources, reports have shown that species-specific differences in amino acid composition of collagen may influence its chemical and physical properties and ultimately influence, or even impair, tissue/organ function.4–6 Collagen type I derived from different tissue sources have been shown to present unique polymerization kinetics profiles which are dependent on age, species, tissue source, and collagen isolation process.7,8 Similar studies have also shown that the amino acid and peptide composition, glycosaminoglycan content, and thermal behavior of bird, frog, and shark collagen are significantly different from land and domestic animals.4 Moreover, clinical experience with tissues comprised of bovine collagen has shown that these products may elicit a host immune response to the engineered tissue and raise the prospect of breaking immune tolerance to endogenous collagen, leading to autoimmunity.9,10

Human and other sources of collagen can be extracted by acid or enzymatic hydrolysis of discarded tissues. Most of the commercially available sources of collagen type I are available in a solution form with concentrations below 10 mg/ml, which can limit the optimization of different therapies. In search for a xeno-free collagen source, recombinant human collagen type I has been proposed as an alternative to animal collagen; however, its widespread application has been limited due to the low yield, high cost, and lengthy production process for commercial applications, as well as lack of enzymes and cofactors that are critical to induce efficient fibrillogenesis to form collagen hydrogels.11 Engineering tissues with human collagen type I have the potential to overcome many of the aforementioned limitations of xenogeneic collagen.

The goal of this study is to provide a systemic comparison of the structural and functional differences of various commercially available human sources of collagen type I with each other and with two of the most commonly used commercially available nonhuman sources. Specifically we compare three human collagen type I products extracted from human skin, placenta, or matrix produced by cultured human fibroblasts with commercial xenogeneic sources (bovine hide and rat tail). We evaluate the physical properties of hydrogels formulated with these products including gelation kinetics, swelling ratio, degradation, and compressive moduli. We then evaluate the use of these materials in three common research applications of collagen type I including 2D and 3D cell culture and matrix source for tissue engineering applications. We find that the source of collagen type I not only influenced hydrogels mechanical properties, but also impacted cell metabolic activities and cell responses to chemotherapy agents in a drug screening assay performed in an in vitro 3D construct with tumor cells. Finally, human collagen was found to support the generation of hydrogels that can both support self-assembly of human endothelial networks in vitro and formation of perfused human vessels in vivo.

2 |. METHODS

2.1 |. Overall experimental approach

As our goal was to compare human collagen-based hydrogels versus animal-derived collagen-based hydrogels, generated from commercially available products, in a broad sense for tissue engineering and regenerative medicine applications, we chose several distinct scenarios in which to test these hydrogel biomaterials. First, we performed a comprehensive set of material characterization studies to compare the material and mechanical properties of human versus animal collagen hydrogels. Next, we employed hMSCs to evaluate collagen hydrogel impact on cell proliferation and viability. Subsequently, we employed two very different application areas to assess the utility of human-based collagen hydrogels versus animal-derived collagen hydrogels. First, to assess these matrices’ utility in a purely in vitro application, 3D tumor constructs–in this case colorectal cancer cells encapsulated in volumes of the hydrogels–were employed in a drug screening study. Second, in a more classical tissue engineering application, these matrices’ capability to support self-assembly of human microvascular networks in vitro and formation of perfused human vessels in vivo was investigated. These different application areas, paired with MSC studies and material characterizations were designed to challenge each hydrogel system in a variety of distinct ways.

2.2 |. Materials

Bovine collagen type I derived from hides (Purecol®), collagen type I derived from rat tail (RatCol®), and human collagen type I derived from neo-natal fibroblasts (Vitrocol®) were purchased from Advanced BioMatrix (San Diego, CA). Human skin-derived collagen type I (HumaDerm) was obtained from Humabiologics Inc (Phoenix, AZ). Human Placenta collagen type I was purchased from Corning (Corning, NY). The source, extraction method and concentration of the different types of commercial collagen are shown in Table 1. Other reagents were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Watham, CA) unless stated otherwise.

TABLE 1.

Source, extraction method, and concentration of different types of commercial collagen

| Collagen | Supplier | Species source | Extraction method | Type | Supplied form | Initial collagen concentration | Final hydrogel concentration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PureCol | Advanced BioMatrix | Bovine hide | Enzyme | Atelo | Solution 3.1 mg/ml | 3.1 mg/ml | 2.48 mg/ml |

| RatCol | Advanced BioMatrix | Rat tail | Acid | Telo | Solution 4.1 mg/ml | 3.1 mg/ml | 2.79 mg/ml |

| VitroCol | Advanced BioMatrix | Human neo-natal dermal fibroblasts | Enzyme | Atelo | Solution 3.1 mg/ml | 3.1 mg/ml | 2.48 mg/ml |

| Corning, Collagen I | Corning | Human placenta | Unknown | Unknown | Solution 3.3 mg/ml | 3.1 mg/ml | 2.79 mg/ml |

| HumaDerm | Humabiologics | Human skin | Enzyme | Atelo | Lyophilized | 3.1 mg/ml | 2.48 mg/ml |

2.3 |. Cell culture

2.3.1 |. 2D culture assays

Human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (Lonza; PT-2501; hMSC; 23-year-old female) were expanded in low glucose-DMEM growth medium supplemented with 10% (FBS) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin in 5% CO2 at 37°C.

2.3.2 |. 3D tumor construct assay

Human colorectal adenocarcinoma cells, Caco-2 (ATCC, Manassas, VA) were cultured in DMEM with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% penicillin streptomycin, and 1% L-glutamine.

2.3.3 |. Isolation and culture of primary cells for microvessel assembly in vivo

Endothelial cell (EC) cultures were established from human endothelial colony forming cells (HECFCs) present in human umbilical cord blood by culturing whole cord blood mononuclear cells from discarded umbilical cords of deidentified donors in EGM-2MV medium (Lonza) on gelatincoated plates as previously described.12 EC colonies spontaneously arose as “late outgrowth cells” by day 14, allowed to reach confluence and then serially passaged in the same medium. Human microvascular placenta PCs were isolated from discarded and deidentified placentas as explant-outgrowth cells, also as previously described.13 Dermal FBs were isolated from freshly discarded human foreskin samples according to previously published protocols.14 As the properties of primary human cell cultures may differ among donors, different human donor tissues were used as sources for the various cell types in different experiments. All tissues were obtained at Yale under protocols approved by the Yale University Institutional Review Board. PCs and FBs were serially cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Atlanta Biologics), 1% Pen/Strep (Gibco). All primary cells were used between subculture 3–7.

2.4 |. Preparation of collagen type I and tissue-derived ECM hydrogels for mechanical characterization in vitro

The initial concentration for different sources of collagen type I was set to 3.1 mg/ml by dissolving (lyophilized solid) or diluting (solubilized liquid) in appropriate acid (i.e., HCl or acetic acid). Collagen hydrogels were synthesized by following the manufacturer’s recommendations. Briefly, bovine, human fibroblasts-derived and human skin-derived collagen type I hydrogels were prepared by mixing eight parts of acid-soluble collagen with one part of 10× PBS and one part of 0.1 N NaOH (pH ~ 7.4), whereas rat tail collagen type I hydrogels were prepared by mixing nine parts of acid-soluble collagen with one part of neutralization solution (pH ~ 7.4), and human placenta collagen hydrogels were prepared by mixing nine parts of acid-soluble collagen with one part of 10× PBS (pH ~ 7.4). Following this step, the neutralized collagen solution was incubated at 37°C for 45 min to induce gelation.

2.5 |. Gelation kinetics

A gelation kinetics assay was performed to determine the fibrillogenesis rate of different sources of collagen type I. Briefly, 100 μl of chilled neutralized collagen solution was casted into individual wells of a 96-well plate at 4°C (N = 4/group) and inserted into M2e Spectramax plate reader (Molecular Devices) preheated at 37°C. Gelation kinetics was determined by measuring the absorbance at 312 nm every 2 min for 120 min. Increase in absorbance value corresponds to increase in the turbidity of the solution during the formation of the hydrogel. All the values were normalized between 0 and 1 by employing a ‘min-max’ normalization technique for each sample of collagen species by using the following equation:

where X–set of absorbance values of x, X’–normalized value of X, min (X)–minimum value in X, max (X)–maximum value in X.

Polymerization rate was calculated by taking the slope of the linear region of the gelation kinetics curve. Polymerization half time was defined as the time needed to reach 50% of the maximum absorbance value.

2.6 |. Swelling and degradation studies

A swelling study was performed to evaluate the water absorption capability of hydrogels prepared using different sources of collagen by following a previously published protocol.15,16 At first, collagen hydrogels were vacuum dried for 24 h and weighed to measure the initial dry weight of the hydrogel (N = 4/group). Following this step, the hydrogels were incubated in 500 μl of 1× PBS at room temperature for 24 h and weighed again to determine the wet weight of the hydrogels. Swelling ratio was calculated by using the following equation:

The stability of collagen hydrogels (N = 4/group) was assessed by performing an in vitro collagenase degradation assay.17 Hydrogels were prepared using different sources of collagen and kept in ultrapure water for 30 min. The hydrogels were gently blotted using a Kimwipe to remove the excess water and weighed to determine the initial weight of the hydrogel. Each hydrogel was then incubated in individual microcentrifuge tubes containing 500 μl of collagenase solution (5 U/ml collagenase in 0.1 M Tris–HCl buffer and 5 mM CaCl2; pH 7.4) at 37°C. At periodic intervals, each hydrogel was removed from the collagenase solution, gently blotted on a Kimwipe, and weighed until the hydrogel was fully degraded. The percent residual mass of the hydrogel was calculated using the following equation:

2.7 |. Compression testing

The compressive modulus of different hydrogels (N = 5/group) was assessed using an MT G2 MicroTester (CellScale, Canada). Briefly, hydrogels (diameter 7.5 mm, thickness 2.5 mm) were placed on an acrylic platform in wet condition within the testing chamber and compressed using a tungsten cantilever beam (0.4 mm diameter) equipped with a stainless-steel platen at a rate of 10 μm/s until a displacement of 20% of the hydrogel thickness. Compressive strain was computed by taking the ratio of the platen displacement to the original thickness of the hydrogel. The compression force was calculated using Euler-Bernoulli beam theory.6 Compressive stress was determined by normalizing the compressive force with the area of the platen. Since the diameter of the hydrogels (7.5 mm) was greater than the area of the platen (3 mm × mm), the average force calculated from beam theory will be overestimated due to nonuniform stress distribution on the hydrogel surrounding the platen. To correct this overestimation, an in-house computer simulation was performed by modulating the hydrogel diameter for a fixed platen geometry. An indentation depth dependent overestimation correction factor of 2.10 (for 10% strain) was applied to obtain the final compressive stress data. Stress–strain curves were generated, and compressive modulus of each hydrogel was determined by calculating the slope of the 0%–10% region of the stress–strain curve.

2.8 |. Scanning electron microscopy

SEM was performed to assess the fibril microstructure of different collagen type I sources (N = 3/group). To maintain the microstructural features of hydrogels, a rigorous sample preparation protocol was followed as described previously.6,18 Briefly, the hydrogels were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde solution (in 1× PBS) overnight at 4°C. Following fixation, hydrogels were washed in 1× PBS and dehydrated in a graded series of ethanol solution (20%, 50%, 75%, 90%) for 15 min each step and twice with 100% ethanol for 1 h. The hydrogels were then subjected to critical point drying using Denton DCP-1 dryer, sputter coated with gold, and observed at 5000 × magnification under SEM (JEOL JSM-6380LV).

2.9 |. Cell viability analysis

2.9.1 |. 2D culture

Collagen type I hydrogels were prepared by adding 200 μl of sterile neutralized collagen solution into each well of a 48-well plate (Corning) and incubating the solution at 37°C for 60 min. Next, hMSCs were seeded on top of hydrogels at a density of 2500 cells/cm2 and cultured in 200 μl of alpha-MEM culture medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin for 14 days. Culture medium was replaced every 3 days. To assess cell viability (N = 4/group/timepoint), hydrogels were washed with 1× PBS on day 7 and day 14 and stained with Calcein AM and ethidium homodimer (Live/dead staining kit, Life Technologies) for 15 min at 37°C. Stained cells were imaged using a fluorescence microscope (Zeiss). The images were analyzed using ImageJ software and the cell viability percentage was measured by counting live (green) and dead (red) cells. The cell number/mm2 was assessed by manually counting the number of cells in each frame and dividing it by the size of the frame area. Measurements were obtained from four images per hydrogel for a total of 16 images per group.

2.9.2 |. 3D culture

For the live/dead cell staining of 3D tumor constructs (N = 3), a 50/50 solution of phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and DMEM was prepared to which calcein AM and ethidium homodimer-1 were added at 0.5 μl/ml and 2 μl/ml, respectively. Next, 300 μl aliquots of the prepared solution was added to each well and 3D tumor constructs were incubated for 30 min at 37°C. 3D tumor constructs were then washed in PBS and imaged using an EVOS M5000 microscope with GFP (470/525 nm) and RFP (531/593 nm) light cubes.

2.10 |. Cell metabolic activity analysis

The metabolic activity of hMSCs was assessed by performing alamarBlue™ assay (N = 8/group/timepoint). At periodic intervals, hydrogels were incubated in 10% alamarBlue™ reagent in a culture medium at 37°C for 2 h. Following incubation, 100 μl aliquots from each well were transferred to a 96-well plate (Greiner) in duplicates and fluorescence was measured at an excitation wavelength of 555 nm and an emission wavelength of 595 nm using an M2e Spectramax plate reader (Molecular Devices). Relative fluorescence units (RFU) are reported as a measure of cell metabolic activity on the hydrogels. Passage-5 cells were used in these experiments.

2.11 |. 3D tumor construct formation

At 80% confluency Caco-2 cells were harvested using 0.05% trypsin and aliquoted into 1.5 ml Eppendorf tubes. Tubes were then centrifuged followed by the supernatant removal and the addition and homogenization of hydrogel components to achieve a cell concentration of 3.0 × 106 cells/ml. Hydrogels were prepared as described above, but with the protein concentrations of 6.0 mg/ml and 3.0 mg/ml for human skin-derived collagen type I and rat tail collagen type I, respectively. After suspending cells in the hydrogel components, 10 μl aliquots (about 30,000 cells) were pipetted into polydimethylsiloxane coated 48-well plates. Following a gelation period of 30–45 min at 37C, 200 μl of DMEM with 10% FBS and 1% Pen/Strep were added to the individual wells.

2.12 |. Chemotherapy screening

Regorafenib (Selleckchem, Houston, TX) and 5-fluorouracil (5-FU; Millipore-Sigma, Burlington, MA) were initially dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide to a stock concentration of 10 mM. Both compounds were serially diluted in DMEM to final concentrations of 1, 10, and 100 μm. After 24 h following 3D tumor construct formation, the media was aspirated from the wells and 500 μl of regorafenib or 5-FU containing media was added into wells separated into six treatment groups. Tumor constructs maintained in drug-free media were used as a control group.

2.13 |. Drug response evaluation by ATP activity quantification

Luminescent ATP activity detection (N = 4) was carried out before adding regorafenib and 5-FU, and at days 1, 4, and 7 after adding the compounds. For ATP activity quantification, spent media was aspirated and a 50/50 solution of the CellTiterGlo 3D kit reagent (Promega, Madison, Wisconsin) and DMEM was added to the 3D tumor constructs. Well plates were covered in aluminum foil and mixed on a shaker plate for 5 min. The assay reaction was allowed to progress for 25 min at room temperature. Solutions were transferred into 96-well white bottom plate wells and the luminescence in each well was quantified with a plate reader (BioTek Cytation 5).

2.14 |. Synthetic microvessel formation and in vivo implantation

Human endothelial cells (ECs), pericytes (PCs) and fibroblasts (FBs) were embedded in a collagen/hyaluronic acid/fibronectin gel and implanted subcutaneously in the abdominal wall of 6- to 8-week-old female C.B-17 SCID/bg mice. Hydrogels were prepared by suspending 3×106 ECs, 1.5 × 106 PCs and 1.5 × 106 FBs in a volume of 550 μl of either rat tail type I collagen (final concentration 1.65 mg/ml) or human skin-derived collagen type I (final concentration: 4.95 mg/ml) supplemented with 100 μl human plasma fibronectin (final concentration: 0.1 mg/ml, EMD Millipore), 100 μl hyaluronic acid (final concentration: 0.5 mg/ml, Sigma), 50 μl of AB human serum (Sigma), 100 μl of 10× pH reconstitution buffer (0.05 M NaOH, 2.2% NaHCO3, and 200 mM HEPES), and 100 μl of 10× HAM-F12 medium (Gibco). In three independent experiments, three replicate gels were prepared for each condition by dispensing 300 μl of each solution in a 48-well plate and allowed to spontaneously gel at 37°C for 15–20 min. After gelation, 500 μl of EGM2-MV medium was added to each well and incubated for approximately 18 h. Each gel was subcutaneously implanted into the abdominal wall of a SCID/bg mouse (6 animals per experiment). In this study, 18 animals were evaluated to observe statistical significance. Percentage of gel weight reduction was calculated as follows: gel weight before implantation subtracted by gel weight after harvesting divided by gel weight before implantation multiplied by 100.

2.15 |. Assessment of in vivo perfusion by injection of fluorescein UEA-I

Fourteen days after implantation, a solution of Fluorescein UEA I (Vector Laboratories), which labels perfused human vessels, was prepared in a 1:1 ratio with saline solution. Two-hundred microliters were injected per mouse via tail vein or retro-orbitally and allowed to circulate for 30 min before harvesting gels. Mice were euthanized and gels were harvested and fixed in 10% buffered formalin for paraffinembedding or embedded in OCT, frozen, and cryosectioned (10 μm thick).

2.16 |. Morphological characterization of gel implants

Frozen sections of gel implants were analyzed by H&E, immunofluorescence, and immunohistochemical staining. For immunofluorescence analysis, tissue sections were immersed in cold acetone for 10 min and blocked for 1 h with 10% normal goat serum in PBS. Slides were then incubated overnight at 4°C, in a humid chamber, with primary antibodies against human collagen IV (mouse; 1:200, clone 1043, Novus Biologicals), mouse F4/80 (rat, 1:50, clone BM8; eBioscience™, a marker of mouse macrophages), rhodamine Ulex Europaeus Agglutinin I (UEA-1; 1:200; Vector Laboratories, a marker of human endothelial cells), NG2-Alexa Fluor 488 (mouse, 1:200, clone 9.2.27, ThermoFisher Scientific, a marker of pericytes), and mouse CD31 (rat, clone SZ31, 1:100, ScyTek Laboratories, a marker of mouse endothelial cells). Slides were then washed with PBS (3×) and incubated for 1 h at room temperature with anti-mouse or anti-rat IgG H&L secondary antibodies conjugated with Alexa Fluor™ 488 or Alexa Fluor 568 (goat, 1:500; Abcam). Slides were mounted with VECTASHIELD antifade mounting medium containing DAPI (Vector Labs) for nuclear staining and imaged on Leica DM6000 inverted fluorescence microscope (Leica Microsystems). Immunohistochemical analysis of mouse macrophages (F4/80) was performed with donkey anti-rat Biotin-SP AffiniPure IgG (H + L) antibody. Substrate to the secondary antibody was included in the VECTASTAIN ABC Peroxidase Kit and AEC Peroxidase Substrate Kit (Vector Laboratories).

2.17 |. Quantification of perfused human vessels and macrophage infiltration

Microscope images of stained tissue sections were taken using a Leica DMI6000 inverted fluorescence microscope. Eight to twelve randomly selected sections sampling all parts of the tissue block were evaluated. Whole sections were imaged using a 4× or 20× objective, with an image pixel size of 0.444 μm. ImageJ software was used to quantify infused fluorescein ulex+, or F4/80+ area in each 4× or 20× field section, respectively. To quantify infused fluorescein ulex+ area, each green channel image was binarized by defining a threshold equally applied to all images. The human perfused vessel area was defined as the number of infused fluorescein ulex+ (nonzero) pixels in the resulting image multiplied by the squared pixel size. To quantify murine macrophage area, the number of red colored pixels were quantified by defining a color threshold and creating a binarized image of the IHC F4/80 stain. The macrophage area was then defined by the number of nonzero pixels in the resulting image multiplied by the squared pixel size. The calculated average from randomly selected sections for each animal was plotted as a single data point in Figure 5B,D.

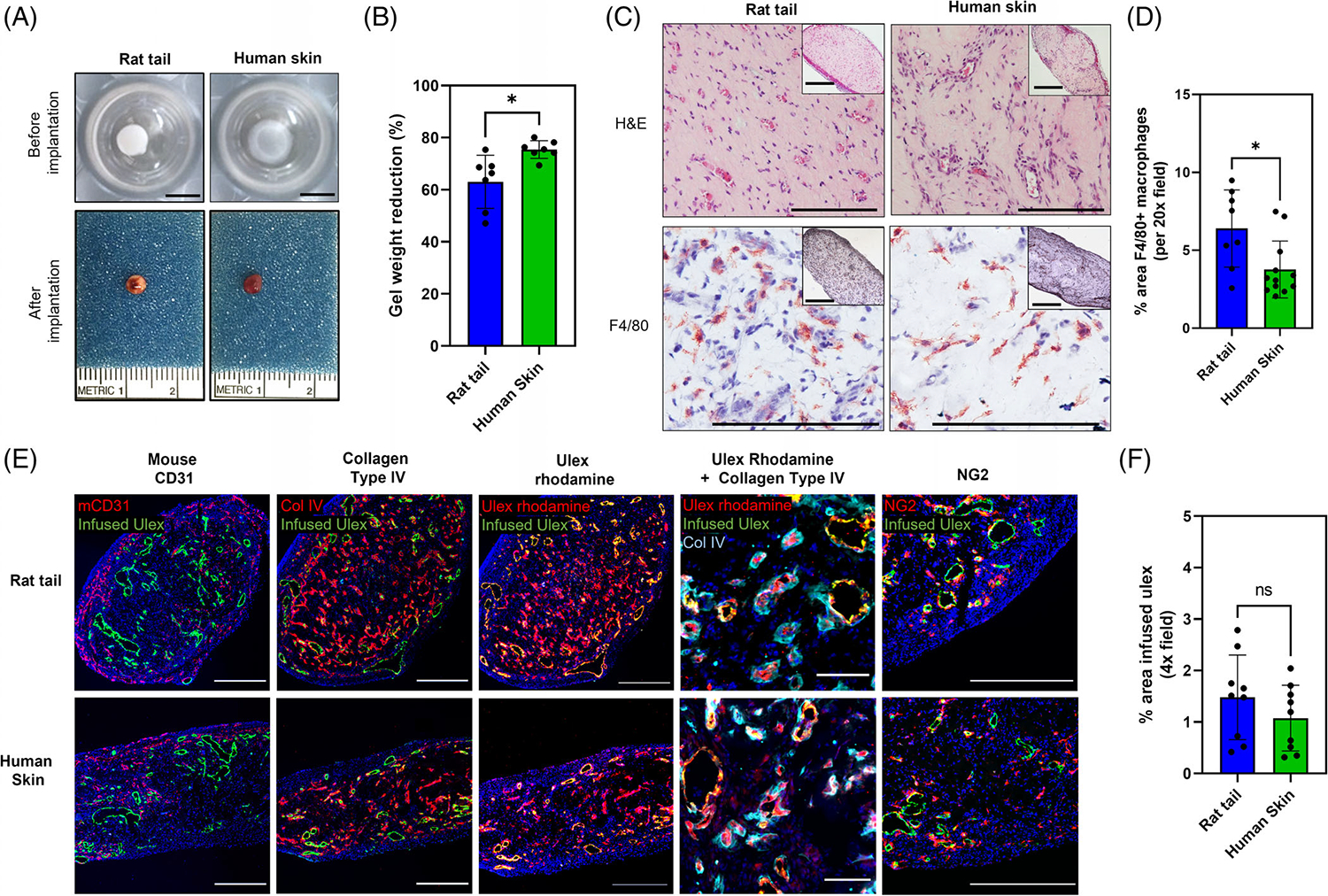

FIGURE 5.

Effects of rat tail collagen type I and human skin-derived collagen type I containing hydrogels on human vessel formation in vivo. (A) Photographs of hydrogels prior and 14 days post-implantation into the abdominal wall of a SCID/bg mouse model. Scale bar: 5 mm. (B) Assessment of gel contraction by measurements of hydrogel weight at the time of implantation and after explant. Data are shown with standard error of mean (SEM) (n = 3; p < .05). (C) Representative H&E images of hydrogels 14 days post-implantation, showing that rat tail and human skin-derived collagen type I containing hydrogels support vessel formation in vivo. Immunohistochemical analysis of F4/80 expression shows different degrees of infiltration of murine macrophages. Inset images represent low magnification views of hydrogel crosssections. Scale bar: 500 μm. (D) Quantification of area of F4/80+ staining shows that degree of infiltration is particularly higher in hydrogels containing human skin-derived collagen type I (* indicates p < .05). (E) Hydrogels formulated with rat tail and human-skin derived collagen type I contain vascular structures 14 days post-implantation. Presence of mouse microvessels and basement membrane deposition was assessed by staining with mouse CD31 and human collagen IV antibodies, respectively. To demonstrate that human EC-lined vessels were perfused, fluorescein ulex was injected 30 min before explant. Staining shows that several human vessels have anastomosed with mouse vessels and became perfused in vivo in rat tail and human skin-derived collagen type I hydrogels. Post-harvest staining with rhodamine ulex shows a significant higher number of human EC-lined vessels in the center of these hydrogels that were not perfused at the time of fluorescein ulex infusion. Scale bar: 500 μm (high magnification images: 100 μm). (F) Quantification of area of infused ulex shows no significant difference in the number of perfused human EClined vessels between conditions. (ns indicates p > .05).

2.18 |. Statistical analyses

Results are expressed as mean ± SD. Statistical analysis for material characterization studies was performed using one-way ANOVA method with Tukey post hoc comparisons. Data for alamarBlue™ assay was combined from two separate experimental runs by normalizing the data from each experimental run with human skin-derived collagen type I (HumaDerm) at day 1 for comparison of different collagen sources. Normalized datapoints from both experiments were then multiplied by the mean value of human skin collagen type I hydrogels at day 1 across experiments and analyzed using two-way ANOVA method with Tukey post hoc comparisons. In studies with 3D tumor constructs and implanted collagen gels in vivo, the significant differences between the means were determined using Studenťs t tests with confidence intervals of 95% or p value<.05. All analyses were conducted with GraphPad Prism v7.0.

3 |. RESULTS

3.1 |. Quantification of gelation kinetics, swelling ratio, degradation and compressive modulus of collagen type I hydrogels

To assess gelation kinetics of different collagen type I sources, hydrogels were prepared according to manufacturer’s recommendations. Gelation kinetics curves showed a sigmoidal shape for all collagen hydrogels (Figure 1A). The polymerization rate (slope of the linear region of the gelation kinetics curve) was significantly higher for rat tail collagen type I, followed by human fibroblasts-derived collagen type I, and human placenta collagen type I hydrogels (p < .05; Figure 1B). Polymerization rates of bovine collagen type I and human skin-derived collagen type I hydrogels were comparable, but significantly slower than other sources of collagen (p < .05). Rat tail collagen type I had the shortest polymerization half time (12 min), followed by human placenta collagen type I (20.5 min) and human fibroblasts-derived collagen type I (25 min). The polymerization half time of bovine and human skin-derived collagen type I were the longest, at approximately 30 min. Together, these results suggest that variations in tissue source, species, and extraction method have a significant impact on the rate of polymerization of collagen hydrogels

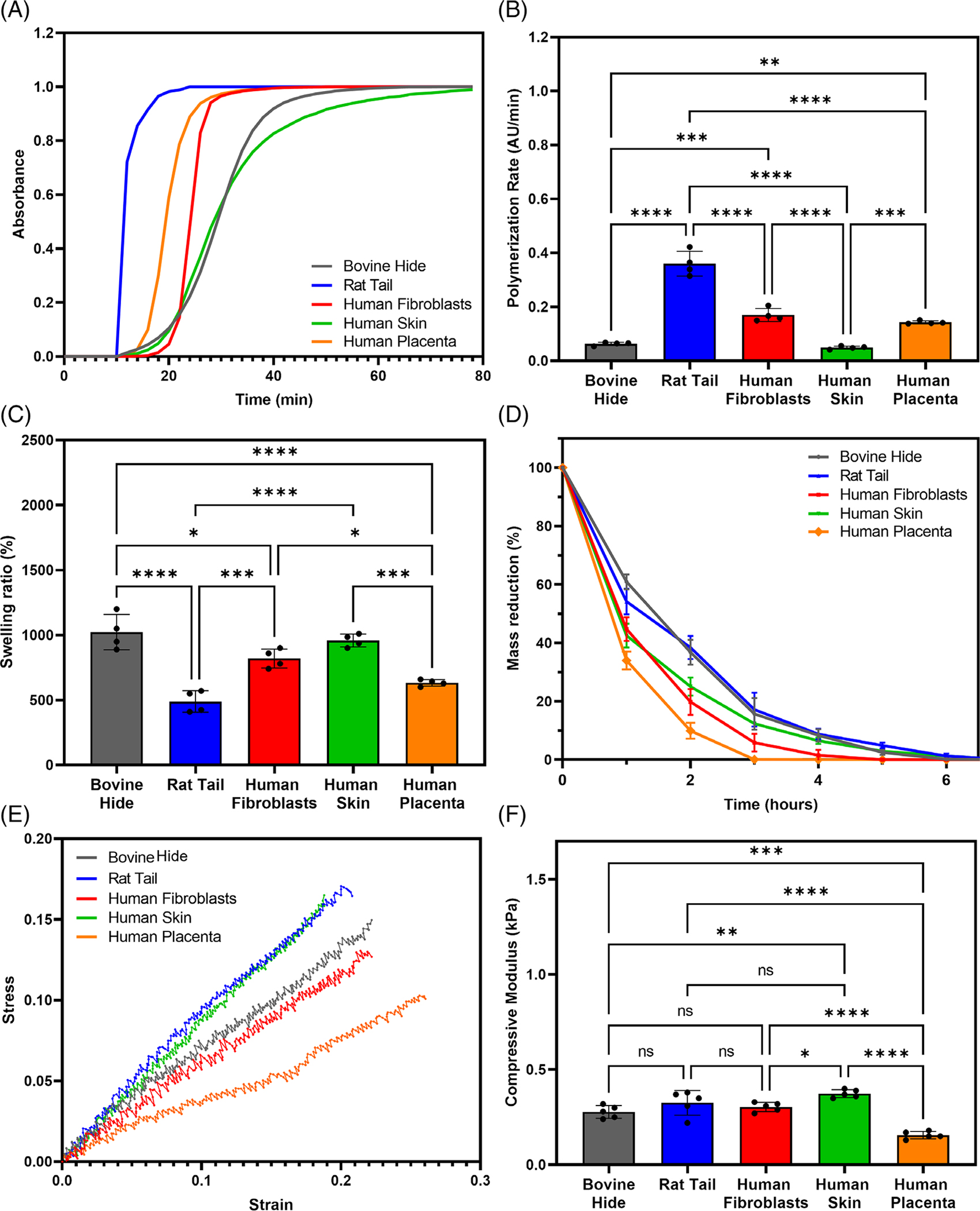

FIGURE 1.

Variation in tissue source, species, and isolation technique has a significant impact on the physical properties of collagen type I (A) Gelation kinetics, (B) polymerization rate determined by linear regression,(C) swelling ratio, (D) in-vitro collagenase degradation with time, (E) representative stress-strain curves, and (F) compressive modulus of different collagen type I hydrogels. (* indicates p < .05, ** indicates p < .01, *** indicates p < .001, **** indicates p < .0001).

The swelling ability of hydrogels is an important feature that has been shown to directly impact cell behavior and it determines the diffusivity of oxygen and nutrients into the scaffold and removal of toxic metabolites. We conducted a swelling analysis and compared the respective swelling ratios between dry and hydrated hydrogels across the different collagen type I sources. The swelling ratios of rat tail and human placenta collagen type I were the lowest of all collagen hydrogels, while the swelling ratios of human skin-derived and bovine collagen type were the highest (p < .05; Figure 1C). Lastly, bovine collagen type I showed a significantly higher swelling ratio compared to human fibroblasts derived - collagen type I (p < .05).

Hydrogel-based scaffolds are often designed to degrade within the body following implantation at a rate similar to the rate of tissue formation. Hydrogel degradation at physiological conditions is often an advantage as it allows for the scaffold to remodel as the new cell-mediated ECM is being deposited. However, if hydrogels are to be used in long-term implants, then their stability and susceptibility to degradation need to be controlled. We performed an in vitro enzymatic degradation of collagen type I hydrogels from different sources using collagenase. Human placenta collagen type I hydrogels completely degraded in 3 h (p < .05), followed by human fibroblasts-derived collagen type I (Figure 1D). Hydrogels synthesized using bovine, rat tail, or human skin-derived collagen type I showed the highest resistance to enzymatic degradation, taking approximately 7 h to completely degrade (p < .05). Together, these results indicate that bovine and human skin-derived human collagen type I yield more stable hydrogels, while human placenta and fibroblasts-derived collagen type I are less resistant to enzymatic degradation.

Micro-compression tests were performed to evaluate the stiffness of collagen hydrogels. Figure 1E depicts the typical stress–strain curves for all collagen type I hydrogels. The compressive modulus of bovine, human fibroblast-derived and rat tail collagen type I were comparable: 0.28, 0.3, 0.33 kPa, respectively, (p > .05). Hydrogels comprised of human placenta collagen type I showed a compressive modulus of 0.15 kPa, the lowest of all hydrogels (p < .05). Lastly, the compressive modulus of human skin-derived collagen type I was 0.37 kPa which was comparable to rat tail collagen type I hydrogels, but significantly higher (p < .05) than bovine and human fibroblast-derived collagen type I hydrogels, and two-fold greater than human collagen type I derived from placenta tissue. Together, these results show that human skin-derived collagen type I hydrogels have comparable stiffness to xenogeneic-derived collagen sources.

3.2 |. Analysis of fibril microstructure, cell viability and metabolic activity in vitro

SEM imaging was performed to qualitatively assess the fibrous organization of collagen type I hydrogels. Bovine, human fibroblasts-derived, and rat tail collagen type I hydrogels exhibited a similar morphology of thin and loosely packed fibers (Figure 2A upper row). In contrast, human skin-derived collagen type I displayed a unique morphology of highly dense collagen fibers, while human placenta collagen type I hydrogels showed lower density but thicker fibers. Overall, these results confirm that the organization of collagen fibers in collagen type I hydrogels largely differs between species, tissue source, and extraction method

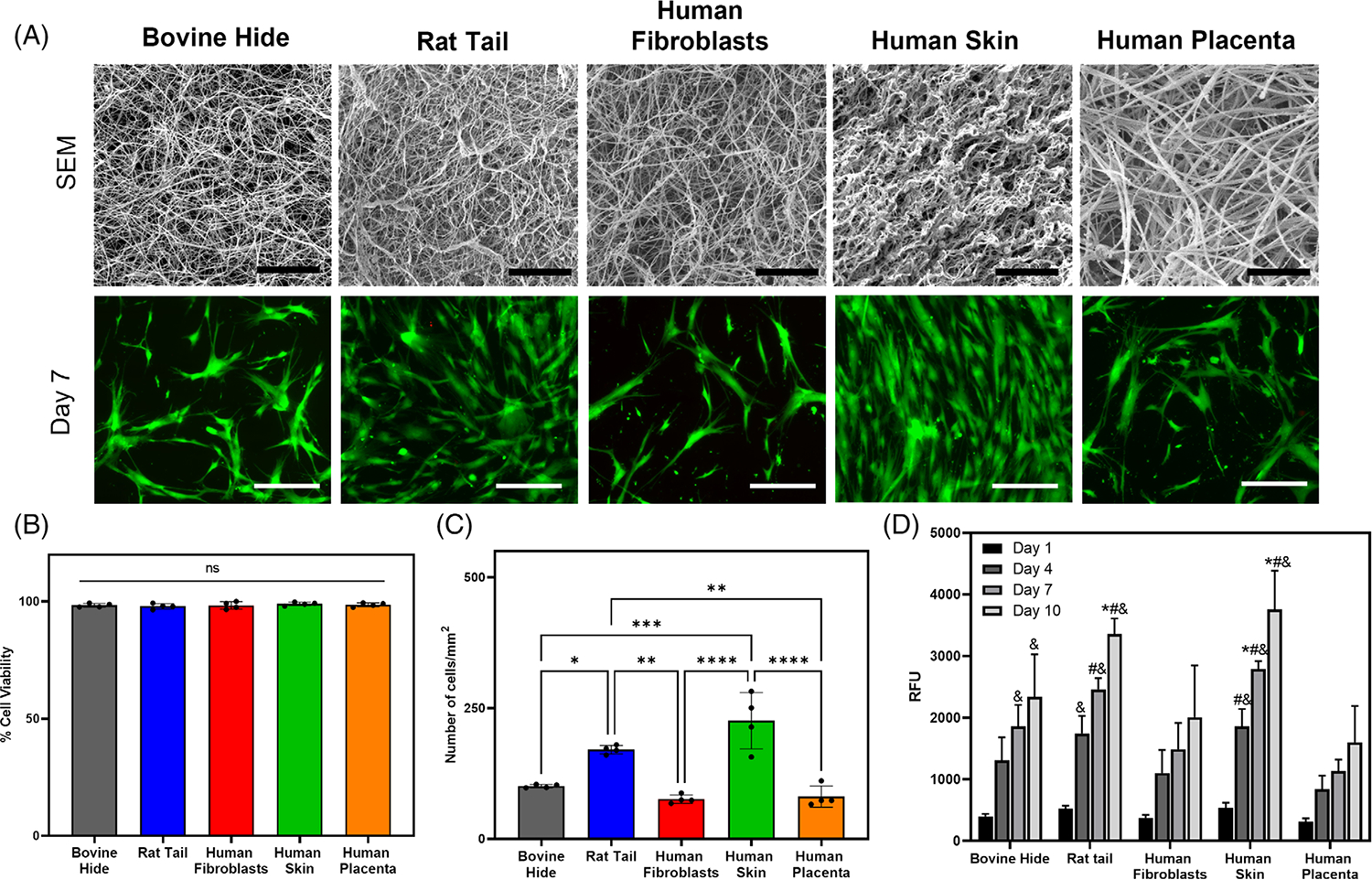

FIGURE 2.

SEM imaging of hydrogels shows differences in collagen fiber morphology due to variation in tissue source, species, and extraction methods. LIVE/DEAD imaging indicates that hMSCs remain viable over time on collagen type I hydrogels. AlamarBlue assay revealed enhanced cell metabolic activity on rat tail and human skin derived collagen type I hydrogels. (A) SEM and Live/Dead assay to assess cell viability. Scale bar: 5 μm - SEM images; 200 μm - Live/Dead staining images. (B) Quantification of cell viability. (C) Quantification of cell number per surface area. (D) Quantification of cell metabolic activity on collagen type I hydrogels using alamarBlue assay–(* indicates p < .05 when comparing with bovine collagen at the same time point, # indicates p < .05 when comparing with human fibroblasts collagen at the same time point, & indicates p < .05 when comparing with human placenta collagen at the same time point).

The viability of human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) seeded on top of collagen type I hydrogels was assessed by live-dead staining assay. Results showed high cell viability in all conditions tested (Figure 2A lower row). Quantitative analyses of the live-dead images revealed cell viability was greater than 95% in all hydrogels ay day 7 (Figure 2B). Quantification of cell number displayed the comparable number of cells/mm2 on bovine, human fibroblasts-derived, and human placenta collagen type I hydrogels (Figure 2C; p > .05). Hydrogels synthesized using rat tail and human skin showed significantly higher cell number than bovine, human fibroblasts-derived, and human placenta collagen type I hydrogels (p < .05)

An alamarBlue™ assay was carried out for fluorometric detection of cell metabolic activity on different hydrogels from day 1 to day 10 (Figure 2D). Results showed that cell metabolic activity increased over time on all hydrogels. Specifically, hMSCs seeded on top of rat tail and human skin-derived collagen type I hydrogels showed a significantly higher metabolic activity than cells cultured on other hydrogels at day 10 (p < .05). At earlier time points, hMSCs metabolic activity on human skin-derived collagen type I was significantly higher than cells cultured on human fibroblasts-derived and placenta collagen type I hydrogels at days 4 and 7 (p < .05). Similarly, cells cultured on rat tail collagen type I hydrogels showed significantly higher cell metabolic activity compared to cells cultured on human fibroblasts-derived and human placenta collagen type I at day 7, and human placenta collagen type I only at day 4. In addition, hMSCs metabolic activity on bovine collagen type I hydrogels was significantly higher than on human placenta collagen type I hydrogels at day 7 and day 10 (p < .05). Higher cell number on rat tail and human skin hydrogels (Figure 2A) suggests that the increase in cell metabolic activity over time may be due to greater cell proliferation on these hydrogels. These results show that hMSCs exhibit highest metabolic activity on rat tail and human-skin derived collagen type I hydrogels.

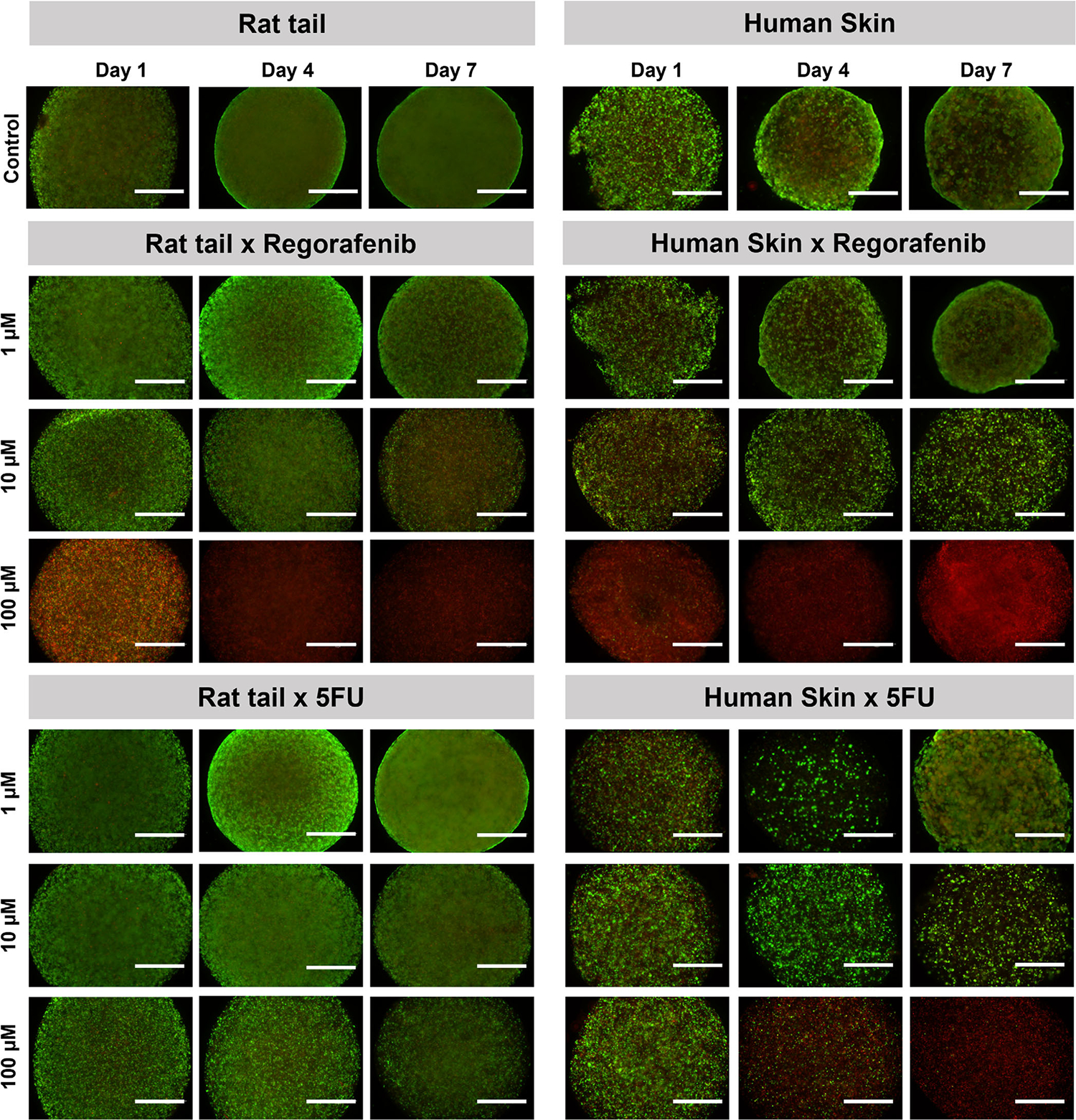

3.3 |. Three-dimensional hydrogel supported tumor constructs respond consistently to chemotherapy

To test compatibility of the various matrices for use in three-dimensional culture applications and drug screening assays, 3D tumor constructs were fabricated, in a manner as we have described for a variety of cell lines and patient-derived tumor cells,19–21 by encapsulating Caco-2 colorectal cancer cells in hydrogel matrices (rat tail collagen type I, and human-skin derived collagen type I). Rat tail type I collagen was chosen as it is commonly used for cancer organoids formation and drug screening research. 3D tumor constructs were exposed to multiple concentrations of the chemotherapy agents 5-fluorouracil (5FU), a thymidylate synthase inhibitor that interrupts DNA replication, and Regorafenib, a tyrosine kinase receptor inhibitor that inhibits multiple receptor tyrosine kinases, including epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2). Both drugs are commonly used and clinically approved chemotherapeutic compounds to treat colorectal cancer. ATP activity quantification and live/dead staining of tumor constructs were performed on days 0, 1, 4, and 7. 3D constructs under control conditions (no drug exposure) maintained a consistent ATP activity over the 7-day period in all four hydrogels tested. In agreement, fluorescent microscopy images of control conditions showed consistent expression of calcein AM-positive cells (viable cells), with minor and non-incremental amounts of ethidium homodimer-1-positive cells (dead cells). Conversely, increasing concentrations of Regorafenib or 5FU in treatment groups resulted in dose dependent reduction in ATP activity over time (Figure 3). Interestingly, 3D tumor constructs treated with 100 μm Regorafenib and formulated with rat tail collagen type I, initially showed the highest ATP activity among all hydrogels, however it rapidly declined to comparable levels by day 4. In agreement with these data, live/dead staining images of regorafenib-treated 3D tumor constructs appear to contain more dead cells at later time points. By day 7, all constructs exposed to 100 μm Regorafenib appear to exclusively contain dead cells.

FIGURE 3.

ATP quantification demonstrates that matrix-supported colorectal 3D tumor constructs largely respond in a dose dependent manner to chemotherapy agents Regorafenib and 5-fluorouracil. ATP luminescence readings of colorectal cancer Caco-2 3D constructs on days 1, 4, and 7 following drug administration at concentrations of 1, 10, and 100 μm (n=4). Conditions include Regorafenib- (Top) and 5- fluorouracil- (Bottom) treated rat tail collagen type I and human skin collagen type I 3D tumor constructs. Statistical significance: †, * and # - p < .05 between different drug concentrations at a given timepoint; ‡ - p < .05 between timepoints at a given concentration.

5FU-treated 3D tumor constructs exhibited a similar trend, although less significant. Moreover, while 3D tumor constructs treated with 10 and 100 μm Regorafenib or 5FU showed an expected decline in ATP activity, constructs exposed to 1 μm show little to no decrease in ATP activity (Figure 3). Live/dead staining was consistent with ATP activity data, showing that 3D tumor constructs exposed to 1 μm Regorafenib or 5FU had increasing ATP activity and calcein AM-positive cells over time, while higher concentrations followed an opposing trend (Figure 4). It is likely that a 1 μm dosage may have not been sufficient to effectively kill all cells contained in the construct. Together these results suggest that 3D tumor constructs formulated with collagen type I of different species may respond differently to various dosages of chemotherapy agents. Of note, 3D tumor constructs formulated with human skin tissue-derived collagen type I have shown the most significant differences in ATP activity and cell viability in response to Regorafenib versus 5FU. These differences may determine potential success or failure in the development of 3D tumor models, in drug screening applications, that can faithfully recapitulate in vivo responses.

FIGURE 4.

LIVE/DEAD visualization of colorectal cancer 3D constructs qualitatively corroborates quantitative data indicating that 3D tumor constructs largely respond in a dose dependent manner to chemotherapy agents. Fluorescent microscope images of colorectal cancer Caco-2 3D constructs stained with calcein AM (green) and ethidium homodimer-1 (red) at days 1, 4, and 7 following drug administration at concentrations of 1, 10, and 100 μm (n = 3). Conditions include Regorafenib- (Top) and 5-fluorouracil- (Bottom) treated rat tail collagen type I and human skin collagen type I 3D tumor constructs. Green–viable cells stained with calcein AM; Red–dead cells stained with ethidium homodimer-1. Scale bar: 100 μm.

3.4 |. Comparisons of type I collagen sources for formation of vascularized hydrogels in vitro and in vivo

Cultured human endothelial cells isolated from an umbilical vein (HUVECs) or differentiated in vitro from umbilical cord blood human endothelial colony forming cells (HECFCs) will spontaneously organize into cords that lumenize to form tubes when suspended in hydrogels based on a mixture of rat tail type I collagen and human plasma fibronectin. Inclusion of human dermal fibroblasts in the gel sustains the viability of the endothelial cells (ECs) and inclusion of human placenta pericytes (PCs) stabilizes and constrains the luminal diameter of the tubes. When implanted in a subcutaneous pocket formed by blunt dissection in the abdominal wall superficial to the abdominal musculature of an immunodeficient C.B-17 SCID/bg mouse, these tubular structures spontaneously anastomose at the border of the gel with mouse microvessels in the wound bed and become perfused. The hydrogel may contract overtime which can be reduced by including hyaluronic acid in the gel. Mouse vessels typically do not invade the gel beyond the region beyond the point of interaction with the human EC-lined vessels. Furthermore, such gels do not elicit a significant foreign body reaction and very few mouse macrophages are found within the gel. Here we aimed to determine if the rat tail collagen type I could be replaced by human collagen to eliminate a potential source of xenoantigenicity as part of a program to bioengineer microvascular constructs for clinical use. In a preliminary screening, several sources of collagen type I were tested, as provided by manufacturers, for their ability to promote self-assembly of endothelial networks in vitro. Gelation rate at the time of preparation and hydrogel contraction over a 5-day period were also assessed. With the exception of rat tail collagen type I, hydrogels prepared with collagen products with a final concentration below 3 mg/ml took a longer period of time to complete polymerization, resulting in cells settling by gravity at the bottom of the well. Although all conditions tested were able to support self-assembly of endothelial networks in vitro, the rapid loss of the initial 3-dimensional cell distribution proved to be inadequate for potential tissue engineering applications (Figure S2). These differences allowed us to compare the ability of human and nonhuman type I collagens to promote in vivo formation and perfusion of human vessels in a SCID/bg mouse model. By gross examination at the time of explant, rat tail or human skin-derived collagen type I-containing hydrogels appeared to be highly vascularized (Figure 5A lower row). Measurement of hydrogels weights before implantation and after explant showed that human skin-derived collagen type I-containing gels showed significantly higher weight reduction over the period of 14 days compared to rat tail collagen type I (p < .05), which is a potential indicator of a lower water retention capacity (Figure 5B). H&E staining of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections of hydrogels confirmed the findings of gross examination and revealed a substantial number of microvessels at 14 days post-implantation in both rat tail or human collagen type I- containing hydrogels (Figure 5C upper row). Quantification of F4/80-stained sections indicated significantly higher infiltration of mouse macrophages in rat tail type I-containing hydrogels compared to human skin-derived collagen type I-containing hydrogels (Figure 5C lower row, 5D). Fluorescein ulex injection 30 min before explant labeled human ECs was used to assess perfusion of human EC-lined vessel segments. Immunofluorescence analysis confirmed that rat tail or human collagen type I-containing hydrogels displayed human CD31+ vessels with many surrounded by a secondary layer of human pericytes (NG2-positive cells) and collagen IV, a major component of the microvessel basement membrane. Some microvessels were lined by mouse ECs, suggesting some degree of host angiogenesis (Figure 5E). No significant differences in the number of perfused human vessels were observed between conditions. (Figure 5F). To assess if all human EC-lined had become perfused 14 days after implantation, we stained tissue sections post-harvest with rhodamine ulex. As excepted, all fluorescein ulex-positive vessels co-localized with rhodamine fluorescein ulex staining, however nonperfused EC-lined segments surrounded by collagen IV were also observed, consistent with incomplete perfusion.

4 |. DISCUSSION

The overall goal of this study was to compare the physical, chemical, and biological properties of different sources of commercially available collagen type I and determine if commercial sources of human type I collagen could be used instead of non-human sourced collagens in a variety of regenerative medicine applications. While all the different sources of collagen showed similar SDS-PAGE profiles, consisting of two α1 and one α2 chain (Figure S1), the results from the current study confirm that the physical and chemical properties of collagen hydrogels may differ across the collagen sources.

Gelation kinetics results (Figure 1) from the current study are in agreement with previous studies that showed that pepsin-treated collagen (atelocollagen) exhibits longer polymerization half times compared to acid-extracted collagen.22,23 This is explained by the retention of telopeptide regions in rat tail collagen (telocollagen), which are lacking in the other collagen products tested, that are vital for the initiation phase, fibril formation phase, and fibril stabilization phase.24 In addition, variation in the number and type of crosslinks and oligomers within the species of collagen molecules can result in different polymerization kinetics.25 While shorter polymerization rate might be preferable in some applications such as bioprinting, all collagen sources polymerized within 60 min. One approach to improve the polymerization rate of collagen is to chemically modify the collagen structure via addition of methacrylate groups and thereby enable the formation of collagen hydrogels via a UV crosslinking approach. Photochemical crosslinking can also help improve the mechanical properties of collagen hydrogels.26 Although rat tail collagen showed the shortest polymerization rate among all different collagen sources, interestingly, it showed the lowest swelling ratio and comparable compressive modulus to most other collagen sources. However, the polymerization rate of the collagen hydrogels did not directly correlate with swelling ratio and compressive modulus. For example, when comparing atelocollagen from same species but different tissue source, human type I collagen from placenta polymerized faster, but showed lower swelling ratio (Figure 1C) and weaker mechanical properties compared to human type I collagen from skin (Figure 1F). On the other hand, bovine type I collagen had similar polymerization rate and swelling ratio to human type I skin collagen, but lower compressive modulus. Higher compressive modulus of human type I skin collagen compared to other atelocollagen sources may be attributed to the high packing density of the collagen fibers as observed by SEM (Figure 2A upper row). Together, these data suggest that differences in the extraction method, tissue source and species can significantly impact the physical properties of collagen hydrogels.

While the current study did not assess the amino acid composition of source-specific collagen, other studies have shown that differences in amino acid composition across different sources of collagen can result in different chemical structure and may play a role in the stabilization of the triple helix structure of collagen.27 The amino acid sequences in collagen have been shown to be crucial to the intra- and intermolecular crosslinking of collagen and directly related to thermostability.6,28 These differences may have significant biological consequences. For example, we showed here that hMSCs seeded on human-skin derived collagen type I hydrogels exhibited improved proliferation compared to other human collagen sources and comparable proliferation to rat tail collagen type I hydrogels (Figure 2B). These differences may be attributed to differences observed in hydrogel mechanical properties which have previously shown to significantly impact cellular responses.29,30 Our SEM analysis of different collagen sources showed different orientation and density of collagen fibers (Figure 2A upper row). These variances in the nature of the collagen fibers can be because of differences in the temperature, phosphate ion concentration, ionic strength, and structural features of collagen molecules. Collagen fiber orientation and structure play an important role for maintaining mechanical strength and interaction with growth factors and provides signal for growth, differentiation, migration, and apoptosis of cells.31 Moreover, collagen has been shown to modulate cell behavior and function either on its own or through integrins interaction with growth factor-mediated mitogenic pathway.32

In recent years, bioengineered 3D tumor construct systems have emerged as important tools for the assessment of drug efficacy and toxicity.33 While 2D culture systems have facilitated significant advances in our understanding of cell biology and disease, they are a relatively simplistic approach to modeling biology, and growing evidence now shows that cells cultured in 2D fail to closely mimic in vivo behavior of tissues or tumors.34–36 Animal derived ECM products such as Matrigel and Rat tail collagen type I and other animal derived ECM products such as Matrigel have been leveraged in a nearly ubiquitous manner to generate and maintain both cell line and patientderived organoids. However, the murine sarcoma producťs undefined composition and rat tail can render these materials invalid for clinical scenarios, including disease modeling in clinical diagnostic settings. Towards this end, the realization of human collagen biomaterials could offer alternatives of equal biological potency to researchers, while ameliorating many of the concerns that animal tumor-derived ECMs have. As a first step and an initial evaluation of comparable human and animal-derived collagen hydrogels, we generated colorectal cancer 3D constructs using the common Caco2 cell line.

Our drug screening assay using 3D tumor constructs, uses differences in protein concentration between rat tail collagen type 1 and human skin derived collagen. Due to the faster polymerization rate of rat tail collagen type 1 (Figure 1B), this protein variation allows us to maintain consistent gelation times. While it is true that differences in characteristics between hydrogels can play a role in cell viability, this aspect of the tumor constructs remained high for both hydrogel conditions based on our LIVE/DEAD images and ATP data (Figures 3 and 4), resulting in similar baseline levels. Nonetheless, we showed that two clinically approved chemotherapy agents, 5-fluorouracil (5FU) and Regorafenib, initially appeared to be effective in inducing cell death, but a subpopulation of tumor cells survived and continued to proliferate (Figure 4). While this assay only lasted 7 days, this phenomenon of tumor escape is indicative of real clinical scenarios.37 We observed a few significant differences in ATP activity and cell viability between drug treatments (Figure 3).38,39 Interestingly, in our study these four different majority collagen-based hydrogel biomaterials serve as a toolbox of sorts to begin to evaluate how differences in these ECM properties influence tumor cells, and more specifically their response to chemotherapy. Lastly, while we recognize the limitations of using a cell line, this is the first study comparing these biomaterials in a 3D tumor construct format. Ongoing studies include the use of more malignant tumor cell lines and the use of patient-derived tumor cells in these ECM biomaterials, which will build on the data described herein.

We investigated if rat tail collagen type I could be replaced by human skin-derived collagen type I to eliminate a potential source of antigenicity to bioengineer microvascular constructs for clinical use. We found that at the time of explant, rat tail or human skin-derived collagen type I-containing hydrogels appeared to be highly vascularized (Figure 5). This result is clinically relevant as 3D culture systems have the potential to be used to regenerate or replace tissues and organs.40,41 The fabrication of complex living constructs that can mimic tissue anatomy and function will not only require the inclusion of vascular networks to support tissue survival in vivo; but will likely require the substitution of animal components which are not clinically and physiologically relevant and have shown to induce strong immune responses when used clinically.42

5 |. CONCLUSIONS

We observed that various sources of commercially available collagen type I tested in the study have different mechanical, biochemical, and biological properties which should be taken into consideration when developing regenerative medicine therapies. Although further investigation is warranted to understand implication of the properties of different collagen and ECM sources, our data suggests that human skin collagen type I, which is physiologically and clinically relevant, can be used as an alternative to animal sources to develop regenerative medicine therapies.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Jordan S. Pober was supported by NIH grants R01-HL085416 and R21-AI159580. Vipuil Kishore would like to acknowledge support by NIH grant R15-AR071102. Tânia Baltazar was supported by the PhRMA Foundation’s Postdoctoral Fellowship in Translational Medicine. Marco Rodriguez, Srija Chakraborty, and Aleksander Skardal acknowledge support from the Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center, the College of Engineering at the Ohio State University, and the Pelotonia organization.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: Mohammad Z. Albanna is a founding member of Humabiologics, a start-up developing human-derived biomaterials for tissue engineering, which provided the HumaDerm products tested in this study. Mohammad Z. Albanna had no role in data collection. The other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of the article at the publisher’s website.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1.Shafiee A, Atala A. Tissue engineering: toward a new era of medicine. Annu Rev Med. 2017;68:102715. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-102715-092331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.León-López A, Morales-Peñaloza A, Martínez-Juárez VM, Vargas-Torres A, Zeugolis DI, Aguirre-Álvarez G. Hydrolyzed collagen-sources and applications. Molecules. 2019;24:4031. doi: 10.3390/molecules24224031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Silvipriya KS, Kumar KK, Bhat AR, et al. Collagen: animal sources and biomedical application. J Appl Pharm Sci. 2015;5:123–127. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Angele P, Abke J, Kujat R, et al. Influence of different collagen species on physico-chemical properties of crosslinked collagen matrices. Biomaterials. 2004;25:2831–2841. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.09.066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lin YK, Liu DC. Comparison of physical–chemical properties of type I collagen from different species. Food Chem. 2006;99:244–251. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2005.06.053 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schmitt T, Kajave N, Cai HH, Gu L, Albanna M, Kishore V. In vitro characterization of xeno-free clinically relevant human collagen and its applicability in cell-laden 3D bioprinting. J Biomater Appl. 2021;35:912–923. doi: 10.1177/0885328220959162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chandrakasan G, Torchia DA, Piez KA. Preparation of intact monomeric collagen from rat tail tendon and skin and the structure of the nonhelical ends in solution. J Biol Chem. 1976;251:6062–6067. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9258(17)33059-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shanmugasundaram N, Ravikumar T, Babu M. Comparative Physicochemical and in vitro properties of fibrillated collagen scaffolds from different sources. J Biomater Appl. 2004;18:247–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aamodt JM, Grainger DW. Extracellular matrix-based biomaterial scaffolds and the host response. Biomaterials. 2016;86:68–82. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.02.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anderson JM, Rodriguez A, Chang DT. Foreign body reaction to biomaterials. Semin Immunol. 2008;20:86–100. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2007.11.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olsen D, Yang C, Bodo M, et al. Recombinant collagen and gelatin for drug delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2003;55:1547–1567. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2003.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shepherd BR, Enis DR, Wang F, et al. Vascularization and engraftment of a human skin substitute using circulating progenitor cell-derived endothelial cells. FASEB J. 2006;20:1739–1741. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-5682fje [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maier CL, Shepherd BR, Yi T, Pober JS. Explant outgrowth, propagation and characterization of human pericytes. Microcirculation. 2010; 17:367–380. doi: 10.1111/j.1549-8719.2010.00038.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baltazar T, Merola J, Catarino C, et al. Three dimensional bioprinting of a vascularized and Perfusable skin graft using human keratinocytes, fibroblasts, Pericytes, and endothelial cells. Tissue Eng Part A. 2020;26:227–238. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEA.2019.0201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim SJ, Park SJ, Kim SI. Swelling behavior of interpenetrating polymer network hydrogels composed of poly(vinyl alcohol) and chitosan. React Funct Polym. 2003;55:53–59. doi: 10.1016/S1381-5148 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nazemi K, Moztarzadeh F, Jalali N et al. (2014). Synthesis and characterization of poly ( lactic-co-glycolic ) acid nanoparticles-loaded chitosan/bioactive glass scaffolds as a localized delivery system in the bone defects [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Ahn J-I, Kuffova L, Merrett K, et al. Crosslinked collagen hydrogels as corneal implants: effects of sterically bulky vs. non-bulky carbodiimides as crosslinkers. Acta Biomater. 2013;9:7796–7805. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2013.04.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Du X, Liu Y, Wang X, et al. Injectable hydrogel composed of hydrophobically modified chitosan/oxidized-dextran for wound healing. Mater Sci Eng C. 2019;104:109930. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2019.109930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Forsythe S, Mehta N, Devarasetty M, et al. Development of a colorectal cancer 3D micro-tumor construct platform from cell lines and patient tumor biospecimens for standard-of-care and experimental drug screening. Ann Biomed Eng. 2020;48:940–952. doi: 10.1007/s10439-019-02269-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maloney E, Clark C, Sivakumar H, et al. Immersion bioprinting of tumor organoids in multi-well plates for increasing chemotherapy screening throughput. Micromachines. 2020;11:208. doi: 10.3390/mi11020208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Votanopoulos KI, Forsythe S, Sivakumar H, et al. Model of patient-specific immune-enhanced organoids for immunotherapy screening: feasibility study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2020;27:1956–1967. doi: 10.1245/s10434-019-08143-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Condell RA, Hanko VP, Larenas EA, Wallace G, Mccullough KA. Analysis of native collagen monomers and oligomers by size-exclusion high-performance liquid chromatography and its application. Anal Bio chem. 1993;212:436–445. doi: 10.1006/abio.1993.1352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gelman RA, Poppke DC, Piez KA. Collagen fibril formation in vitro. The role of the nonhelical terminal regions. J Biol Chem. 1979;254: 11741–11745. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9258(19)86545-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kreger ST, Bell BJ, Bailey J, et al. Polymerization and matrix physical properties as important design considerations for soluble collagen formulations. Biopolymers. 2010;93:690–707. doi: 10.1002/bip.21431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eyre DR, Wu J-J. Collagen cross-links. In: Brinckmann J, Notbohm H, eds. Collagen. Topics in Current Chemistry. Springer; 2005:207–229. doi: 10.1007/b103828 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nguyen T, Watkins KE and Kishore V (2019). Photochemically crosslinked cell-laden methacrylated collagen hydrogels with high cell viability and functionality, 1–10. 10.1002/jbm.a.36668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Josse J, Harrington WF. Role of pyrrolidine residues in the structure and stabilization of collagen. J Mol Biol. 1964;9:269–287. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosenbloom J, Harsch M, Jimenez S. Hydroxyproline content determines the denaturation temperature of chick tendon collagen. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1973;158:478–484. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Voytik-Harbin SL, Roeder BA, Sturgis JE, Kokini K, Robinson JP. Simultaneous mechanical loading and confocal reflection microscopy for three-dimensional microbiomechanical analysis of biomaterials and tissue constructs. Microsc Microanal. 2003;9:74–85. doi: 10.1017/S1431927603030046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Williams BR, Gelman RA, Poppke DC, Piez KA. Collagen fibril formation. J Biol Chem. 1978;253:6578–6585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu C-Y, Matsusaki M, Akashi M. Cell effects on the formation of collagen triple helix fibers inside collagen gels or on cell surfaces. Polym J. 2015;47:391–399. doi: 10.1038/pj.2015.2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koohestani F, Braundmeier AG, Mahdian A, Seo J, Bi JJ, Nowak RA. Extracellular matrix collagen alters cell proliferation and cell cycle progression of human uterine leiomyoma smooth muscle cells. PLoS One. 2013;8:e75844. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Devarasetty M, Mazzocchi AR, Skardal A. Applications of bioengineered 3D tissue and tumor organoids in drug development and precision medicine: current and future. BioDrugs. 2018;32:53–68. doi: 10.1007/s40259-017-0258-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mazzocchi A, Devarasetty M, Herberg S, et al. Pleural effusion aspirate for use in 3D lung cancer modeling and chemotherapy screening. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 2019;5:1937–1943. doi: 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.8b01356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Skardal A, Aleman J, Forsythe S, et al. Drug compound screening in single and integrated multi-organoid body-on-a-chip systems. Biofabrication. 2020;12:25017. doi: 10.1088/1758-5090/ab6d36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Skardal A, Devarasetty M, Forsythe S, Atala A, Soker S. A reductionist metastasis-on-a-chip platform for in vitro tumor progression modeling and drug screening. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2016;113:2020–2032. doi: 10.1002/bit.25950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boumahdi S, de Sauvage FJ. The great escape: tumour cell plasticity in resistance to targeted therapy. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2020;19:39–56. doi: 10.1038/s41573-019-0044-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kuczek DE, Larsen AMH, Thorseth M-L, et al. Collagen density regulates the activity of tumor-infiltrating T cells. J Immunother Cancer. 2019;7:68. doi: 10.1186/s40425-019-0556-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Devarasetty M, Skardal A, Cowdrick K, Marini F, Soker S. Bioengineered submucosal organoids for in vitro modeling of colorectal cancer. Tissue Eng Part A. 2017;23:1026–1041. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2017.0397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bajaj P, Schweller RM, Khademhosseini A, West JL, Bashir R. 3D biofabrication strategies for tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2014;16:247–276. doi: 10.1146/annurev-bioeng-071813-105155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oliveira SM, Reis RL, Mano JF. Towards the design of 3D multiscale instructive tissue engineering constructs: current approaches and trends. Biotechnol Adv. 2015;33:842–855. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2015.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sadtler K, Singh A, Wolf MT, Wang X, Pardoll DM, Elisseeff JH. Design, clinical translation and immunological response of biomaterials in regenerative medicine. Nat Rev Mater. 2016;1:16040. doi: 10.1038/natrevmats.2016.40 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.