Abstract

Herpes simplex virus infection is a major cause of vision loss in humans. Eye damaging consequences are often driven by inflammatory cells as a result of an immune response to the virus. In the present report, we have compared the effect of inhibiting energy metabolism with etomoxir (Etox), which acts on the fatty acid oxidation pathway and 2-Deoxy-D-glucose (2DG), which acts on glycolysis for their inhibitory effects on herpetic ocular lesions. Both drugs showed similar protective effects when therapy was started on the day of infection, but some 2DG recipients succumbed to encephalitis. In contrast, all Etox recipients remained healthy. Both drugs were compared for effects on inflammatory reactions in the trigeminal ganglion (TG), where virus replicates and then establishes latency. Results indicate that 2DG significantly reduced CD8 and CD4 Th1 T cells in the TG, whereas Etox had minimal or no effect on such cells, perhaps explaining why encephalitis occurred only in 2DG recipients. Unlike treatment with 2DG, Etox therapy was largely ineffective when started at the time of lesion expression. Reasons for the differential effects were discussed as was the relevance of combining metabolic reprogramming approaches to combat viral inflammatory lesions.

Keywords: 2DG, etomoxir, FAO, HSV, immunometabolism, immunopathogenesis

1. Introduction

Damage to host tissues resulting from a viral infection is oftentimes in large part the consequence of a host immune response to the infection. Control of such lesions requires the use of drugs and biologicals that counteract the immune-mediated inflammatory process. Currently, several anti-inflammatory drugs are used for this purpose, but most have side effects, especially when used for prolonged periods. In the search for alternative control measures, an approach finding favor in the cancer and autoimmune field is to reprogram one or more metabolic pathways used by cells that are principally involved in the inflammatory events [1]. It is often the case that the activity of immune cells that orchestrate the inflammatory reactions have a high and rapid need for glucose metabolism, which is mainly provided by the glycolysis pathway [2]. Accordingly, inhibiting this pathway, as can be achieved with the drug 2DG, can control lesion severity [3]. We reported previously that inflammatory reactions in the eye caused by infection with herpes simplex virus (HSV) can be controlled using 2DG therapy [4]. However, there were potential problems when using 2DG to control herpetic lesions, since HSV is a virus that can on occasion disseminate to the brain causing encephalitis [4, 5]. We observed that herpetic encephalitis became a common occurrence if 2DG therapy was used when replicating virus was still present in the cornea [5]. Consequently, if viral lesions are to be controlled using procedures that influence metabolism, it will be necessary to identify inhibitory approaches which can compromise overt inflammation, but have minimal or no damaging side effects [6]. The urgency of this objective was recently emphasized with the realization that the severe often lethal consequences of Covid-19 in the lung primarily represent host inflammatory reactions to the infection with these lesions needing to be managed with anti-inflammatory procedures [7]. Several other virus infections can also cause tissue damage primarily because of a host response against the infection and these also may be candidate diseases to be controlled by using metabolic reprogramming approaches [8]. In the present report, we have evaluated the benefits of using the drug etomoxir (Etox), which acts by inhibiting the production of ATP generated by the fatty acid oxidation (FAO) pathway [9] comparing it to 2DG. Etox has not to our knowledge been evaluated as a means to control viral immunoinflammatory lesions, but has been used to counteract such lesions in some cancers and autoimmune diseases [10, 11].

Our results show that administering Etox from the onset of HSV ocular infection resulted in a marked reduction in corneal lesions with significantly reduced numbers of both innate cells and T cell responses, particularly Th17 T cells in the lesions. Notably, all Etox-treated recipients survived and showed no sign of encephalitis as did occur in several animals that received therapy with 2DG, as was also shown in previous studies [4]. The explanation for the different outcomes correlated with different effects of Etox and 2DG on inflammatory cells in the local TG. Thus, Etox had minimal effects on inflammatory T cells in the TG, whereas 2DG markedly reduced the T cell response, especially CD8 cells thought mainly involved at preventing HSV from spreading to the central nervous system (CNS) [12].

Etox was also evaluated as a therapeutic drug starting at the time of lesion onset. The outcome was variable and the difference to untreated controls not significant. However, in animals that showed diminished lesions, an analysis of the ocular lesions revealed that the major effect of Etox therapy was to reduce the numbers of neutrophils and macrophages with the effect on T cell subset numbers usually not evident. Accordingly, Etox therapy was a valuable approach to control the severity of herpetic inflammatory lesions if used early after infection and the therapy avoided the complication of herpetic encephalitis. However, Etox was of limited value if treatment was begun once lesions were already underway.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animals

Animal studies were performed on seven to eight-week-old C57BL/6 female mice (Envigo, US). Ocular infections and tissue harvesting studies were performed in a pathogen-free ABSL-2 facility according to animal protocols which have been approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, University of Tennessee Knoxville. Veterinary and animal husbandry care were provided by the Animal Facility and Office of Laboratory Animal Care. Ocular virus infection procedures were done in accordance with the regulations recommended by The Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology. Animals were inspected daily by responsible researchers and facility staff members. Animals exhibiting severe clinical symptoms were given diet gel for support. Animals were euthanized immediately if they were severely lethargic or encephalitic.

2.2. Virus and Cells

HSV-1 RE strain (obtained from Robert Hendricks, University of Pittsburgh, PA, US) was used in all ocular eye infection studies in C57BL/6 mice. Virus was cultured and propagated in Vero cells (ATCC, CCL81). Virus stocks were kept in −80°C. To quantify virus titer, a plaque assay was performed as described before [5].

2.3. Ocular HSV-1 Infection

This was performed exactly as described previously [13]. In brief 3×104 PFU of HSV-1 RE was applied to the scarified cornea of anaesthetized mice (1.25%, 0.02 ml/g; 2,2,2-Tribromoethanol, Acros Organics, AC421430100, USA) and lesion severity, measured as described in detail elsewhere [14]. The health status was recorded daily.

2.4. Drug treatment and clinical scoring

The FAO inhibitor (Etomoxir sodium salt; Cayman Chemical, 828934-41-4) and glycolysis inhibitor (2DG; TCI, D0051) were dissolved in sterile PBS (Corning, 21–031-CV). A group of mice (n=4, repeated twice) received 250 mg/Kg 2DG or 15 mg/Kg etomoxir [15], via IP twice a day starting from the day of infection until studies were terminated on 14 dpi. For therapy, a group of mice (n=4, repeated twice) received 15 mg/Kg etomoxir via IP, twice a day, starting at day 6 PI for 9 days and studies were terminated at day 14 pi. In each experimental design, a control group (n=4, repeated twice) was included that received sterile PBS, IP (0.2 ml).

Slit-lamp eye microscopic examination (Kowa Company, Nagoya, Japan) was performed for all groups to record levels of angiogenesis and stromal keratitis, as described in our previous study [14]. Studies were terminated for those mice that showed severe central nervous symptoms, such as inability to stand and unable to move or lethargic upon notice given by ABSL-2 facility veterinarians.

2.5. Tissue harvesting and flow cytometry analysis

To enumerate and quantify immune cells, cornea and TG samples were collected from mice when studies were terminated on day 14 pi. To compare the cellular immune events between treated and untreated groups in the eye, corneal samples and TGs were collected from mice showing positive eye lesions equal to or greater than 2 stromal keratitis (SK) eye scoring. Individual corneas and TG tissue samples were processed to recover cells as described in detail elsewhere [13]. In brief, co individual corneas and TGs were enzymatically dissociated using liberase (1.5 mg/ml; Roche Diagnostics, 5401020001) and tissue grinding meshes (Fisherbrand, 22363547). Cells were resuspended in complete RPMI-1640 media (Corning, 10041CV; 10% FBS, 1% Antibiotic mix; Corning™ 30004CI) enumerated and identified by cytometry analysis. Immune cells collected from cornea and TGs were divided into two parts and half processed for T cells (total CD4 T cells, Th1, Th17, Treg, and total CD8 T cells) while other half processed for innate cells (total leukocytes, neutrophils and macrophages). Individual cell types were identified as described previously [13]. Cell staining was performed using U-bottom 96 well plate (Corning, 3799). To identify surface and intracellular expressions, innate and T cells staining performed exactly as described previously [13]. Cells were fixed in 1% paraformaldehyde containing FACS buffer (2% FBS containing PBS) before running flow cytometry. Cell analysis was done using FlowJo (Tree Star, Ashland, OR) as described previously [13].

2.6. Statistical analysis

To evaluate the statistical significance between treated and untreated groups, a statistical software (GraphPad Prism 7) was used. Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test was performed for percent survival analysis. To identify significance levels in multiple groups, one-way ANOVA test was performed. To compare significance levels between two groups, Mann-Whitney test was chosen. The level of significance was considered as follows: *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; and ****, p < 0.0001. Dots are representing individual values and the length of error bars are representing the standard deviation.

3. Results

3.1. Early treatment with Etox diminishes the severity of stromal keratitis lesions

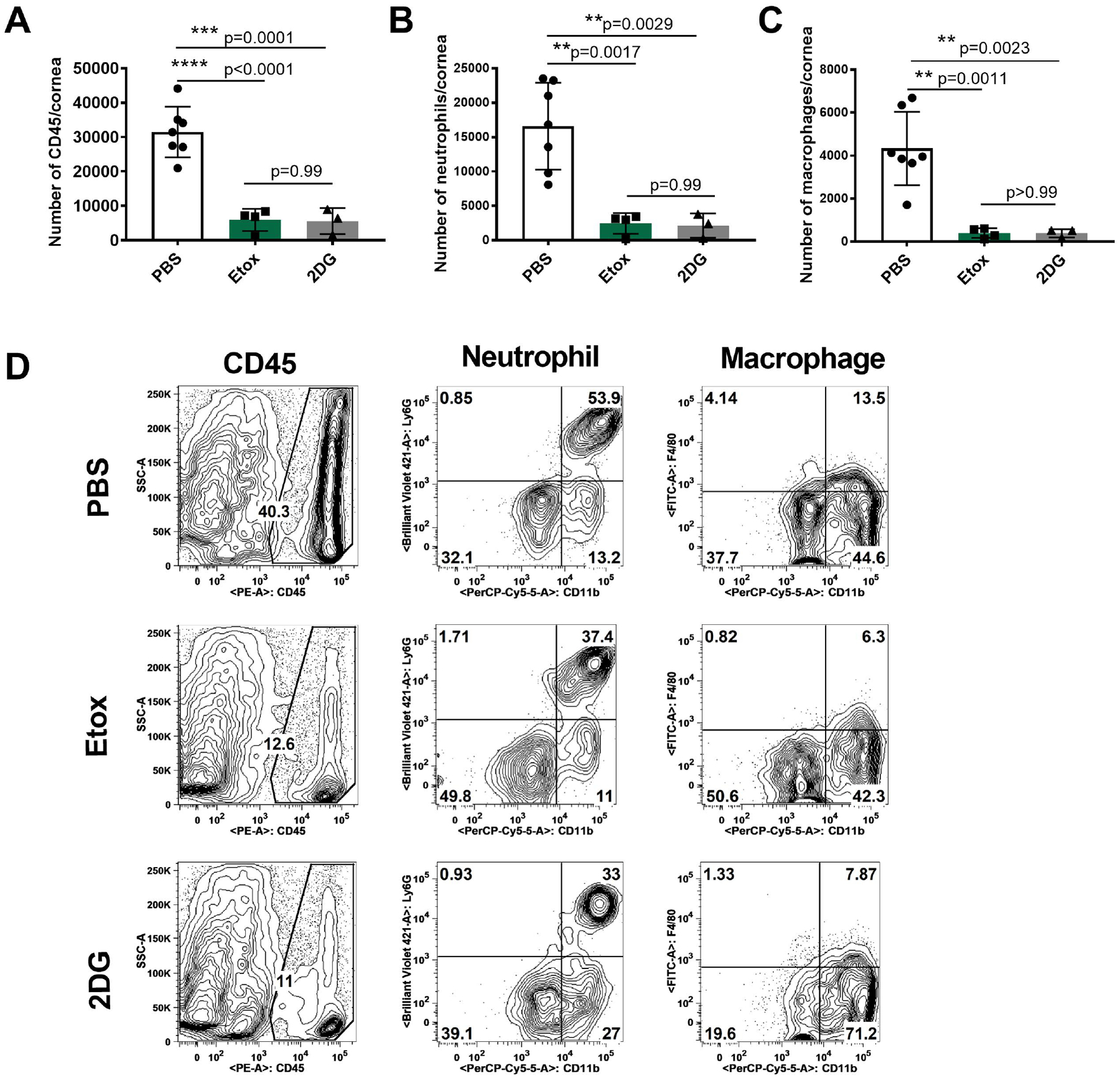

Ocular infections with HSV were performed in young C57BL/6 mice and some animals were treated daily with either Etox (15 mg/kg), 2DG (250 mg/Kg) or PBS. Animals were observed daily for neurological signs as well as for ocular lesions. Each experimental group involved 8 eyes and 3 experiments of the same design were performed. The results in Fig. 1A–C record the ocular disease severity in surviving animals on day 14 when the experiments were terminated. All animals in the control and Etox-treated group survived showing no signs of encephalitis. But, in the experiment shown 38% of the 2DG group developed neurological signs and were terminated (Fig. 1A). Animals in both the Etox and 2DG groups showed reduced ocular disease compared to the control group (Fig. 1B and C). Ocular samples from surviving animals with 2+ or more lesions were collected on day 14 from all groups and the inflammatory cells isolated from individual corneas were identified and quantified. The results shown in Fig. 2A–D indicate that total leukocytes (CD45) were diminished in corneas to a comparable level of around 5-fold in both Etox (****p<0.0001) and 2DG-treated animals (***p=0.0001) compared to PBS controls (Fig. 2A). On average, neutrophils were reduced by 6.7-fold (**p=0.0017) and 7.8-fold (**p=0.0029) in Etox and 2DG groups respectively compared to PBS controls (Fig. 2B). Proinflammatory macrophages were also decreased in numbers on average around 10-fold (**p = 0.0011) and 11-fold (**p=0.0023) in Etox and 2DG-treated mice, respectively, compared to controls (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 1.

Comparison of ocular HSV disease survival and lesion severity. C57BL/6 mice (n=8) were infected with HSV-1 RE (3×104PFU) and treated daily with Etox (15 mg/kg) or 2DG (250 mg/kg). Controls received PBS only. Fig. 1A shows the percentage of survival and log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test results. Fig.1B shows the extent of angiogenesis and Fig. 1C the severity of SK recorded on 14 days pi. Studies were performed three times and data collected from two independent studies. To compare eye lesions in treated and untreated groups, one-way ANOVA performed with the mean SD. The level of significance was represented as follows; *p<0.05.

Fig. 2.

Comparison of proinflammatory innate cell responses in the corneas at 14 days pi in Etox and 2DG treated and control animals that showed ocular lesions (2+ or greater). Fig. 2A shows total leukocytes (CD45), Fig. 2B shows neutrophil cell numbers (CD45, CD11b, CDLy6G) and Fig. 2C shows macrophage cell numbers (CD45, CD11b, F4/80). Fig. 2D shows flow plots representing the average cell frequencies from PBS, Etox and 2DG-treated animals. Studies were performed three times and data represent two independent studies (n=7 for PBS, n=4 for Etox, n=3 for 2DG). To compare the effects of two drugs, one-way ANOVA test was performed with the mean SD. The levels of significance as follows; **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001. SSC-A, side scatter A.

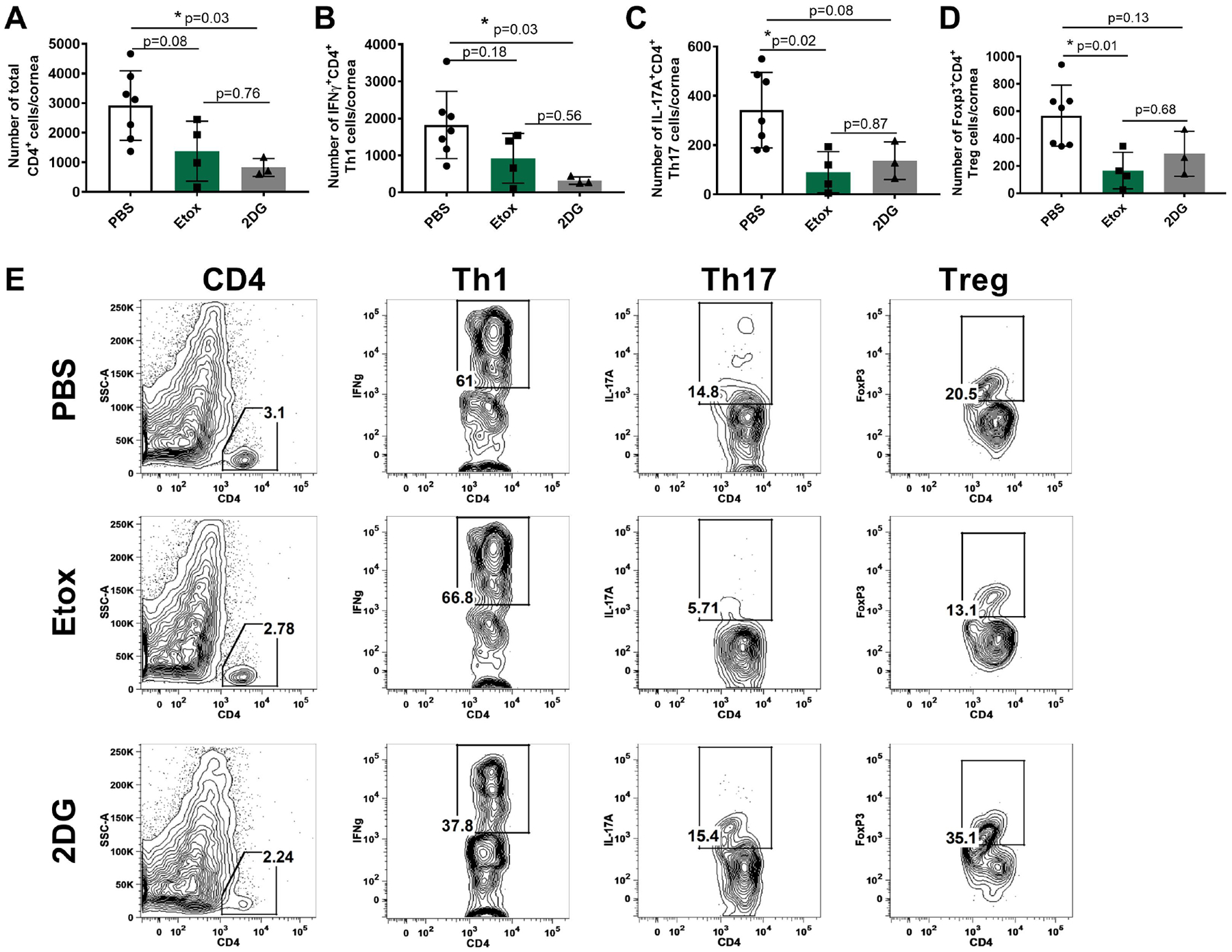

Fig. 3 records the average T cell response in the same cornea samples from different groups. The responses were diminished in both the Etox and 2DG groups compared to PBS controls. In addition, and the pattern of changes in the Etox and 2DG groups was different (Fig. 3A–E). The average number of total CD4 T cells in the Etox and 2DG recipients was reduced by 2.1-fold and 3.5-fold respectively (Fig. 3A) compared to controls. With regard to the treatment effects on different subsets of T cells, 2DG was more inhibitory to Th1 cells than was Etox (Fig. 3B). Thus, 2DG reduced the Th1 response by approximately 5-fold, but Etox less than 2-fold (Fig. 3B) compared to controls. Etox had a greater inhibitory effect on Th17 cells (average 3.8-fold) compared to 2DG (average 2.5-fold) (Fig. 3C). The effect on Treg responses of the two drugs was also measured and compared to controls. Etox reduced the Treg response 3.4-fold while 2DG reduced Treg cell numbers 2-fold compared to controls (Fig. 3D).

Fig. 3.

Comparison of T cell responses in the corneas of surviving mice on day 14 pi in Etox and 2DG treated and controls with positive ocular lesions (2+ or greater). Cells were isolated and stimulated with PMA/Iono for intracellular cytokine expression. Fig. 3A shows total CD4 T cell numbers, Fig. 3B shows Th1 cell numbers (CD4, IFNγ), Fig. 3C shows Th17 cell numbers (CD4, IL-17A), Fig. 3D shows Treg cell numbers (CD4, Foxp3). Fig. 3E shows flow plots representing the average cell frequencies from PBS, Etox and 2DG-treated animals. Studies were performed three times and data represent of two independent studies (n=7 for PBS, n=4 for Etox, n=3 for 2DG). To compare the effects of two drugs, one-way ANOVA test was performed with the mean SD. The level of significance as follows; *p<0.05. SSC-A, side scatter A.

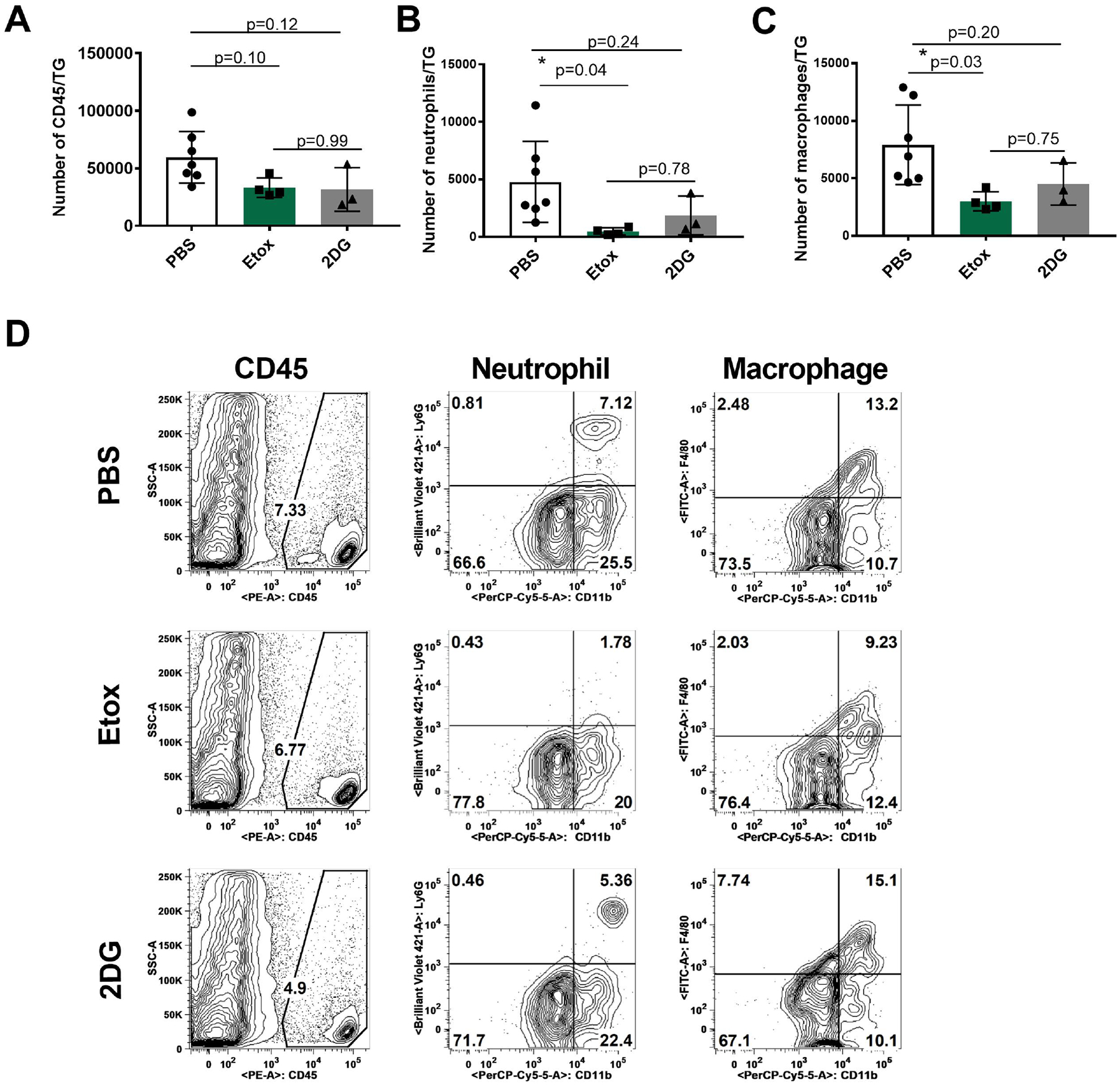

As observed, a proportion of the 2DG-treated animals succumbed to encephalitis, which we have advocated might be explained by 2DG affecting the inflammatory response in the TG to which virus disseminates and, if not constrained, spreads to the brain to cause encephalitis [5]. In consequence, we also compared the inflammatory cell response in the TG of surviving animals that had developed positive eye lesions on day 14 when experiments were terminated. The results are shown in figures 4 and 5 and these show a differential response pattern in the three groups. Compared to controls, the magnitude of the TG inflammatory response following both Etox and 2 DG therapy was reduced (Fig. 4A–D). In addition, the pattern of responsiveness in Etox and 2DG recipients also showed differences. As shown in Fig. 4A, the total inflammatory cell numbers were reduced in both Etox (p=0.10) and 2DG (p=0.12) recipients by about 2-fold, but the results were not significant. However, neutrophils were reduced by 10-fold (*p=0.04) and 2.6-fold (p=0.24) on average in Etox and 2DG groups, respectively, compared to PBS controls (Fig. 4B). On average, the numbers of proinflammatory macrophages were also decreased around 2.6-fold (*p=0.03) and 1.8-fold (p=0.20) in Etox and 2DG-treated animals, respectively, compared to PBS controls (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4.

Comparison of innate cell responses in the TGs of surviving mice on day 14 pi in Etox and 2DG treated and controls (2+ or greater eye lesions). Fig. 4A shows total leukocytes (CD45), Fig. 4B shows neutrophils (CD45, CD11b, CDLy6G) and Fig. 4C shows macrophages (CD45, CD11b, F4/80). Fig. 4D shows flow plots representing the average cell frequencies from PBS, Etox and 2DG-treated animals. Studies were performed three times and data represent of two independent studies (n=7 for PBS, n=4 for Etox, n=3 for 2DG). To compare the effects of two drugs, one-way ANOVA test was performed with the mean SD. The level of significance as follows *p<0.05. SSC-A, side scatter A.

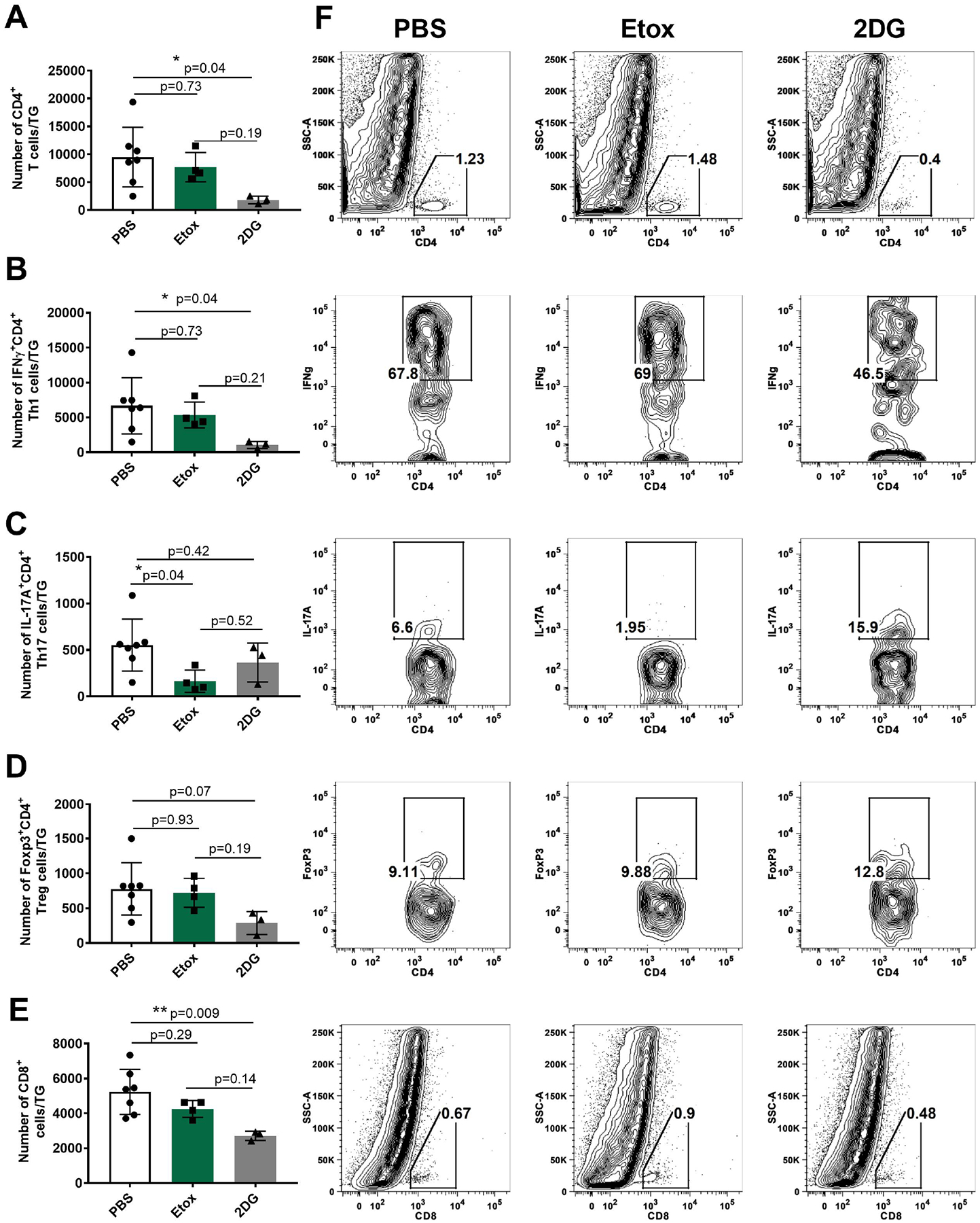

Fig. 5.

Comparison of T cell responses in the TGs of surviving mice on day 14 pi in Etox and 2DG treated animals and controls (2+ or greater eye lesions). Cells were isolated and stimulated with PMA/Iono for intracellular cytokine expression. Fig. 5A shows total CD4 T cell numbers, Fig. 5B shows Th1 cell numbers (CD4, IFNγ). Fig. 5C shows Th17 cell numbers (CD4, IL-17A). Fig. 5D shows Treg cell numbers (CD4, Foxp3). Fig. 5E shows total CD8 T cell numbers in treated and PBS controls. Fig. 5F flow plots representing the average cell frequencies from PBS, Etox and 2DG-treated animals. Studies were performed three times and data represent of two independent studies (n=7 for PBS, n=4 for Etox, n=3 for 2DG). To compare the effects of two drugs, one-way ANOVA test was performed with the mean SD. The level of significance as follows; *p<0.05, **p<0.01. SSC-A, side scatter A.

The results of the treatment effects on the average TG T cell responses is shown in Fig. 5. The total CD4 T cell response was significantly reduced with 2DG therapy (5.4 fold, *p=0.04), but not by Etox (p=0.73) (Fig. 5A). In these same samples, the Th1 response was reduced by 8-fold (*p=0.04) on average, but in Etox recipients, the reduction of the Th1 cells was not significant (Fig. 5B). In contrast, Etox therapy did cause a significant reduction in the Th17 response (*p=0.04), which was not apparent with 2DG therapy (Fig. 5C). The effects of two drugs on Treg responses were also recorded and compared to PBS controls. As shown in Fig. 5D, treatment with 2DG reduced the Treg response by 3.2-fold (p=0.07) on average compared to PBS controls, whereas Etox did not show inhibitory effect on Treg (p=0.93) when compared to PBS controls. The effect of the two therapies on the TG CD8 response is shown in Fig. 5E. As is evident, 2DG was significantly suppressive to the CD8 response (**p=0.009), but Etox failed to significantly affect the CD8 T cell response (Fig. 5E).

3.2. Effect of Etox therapy on the inflammatory response to HSV when therapy commenced on day 6

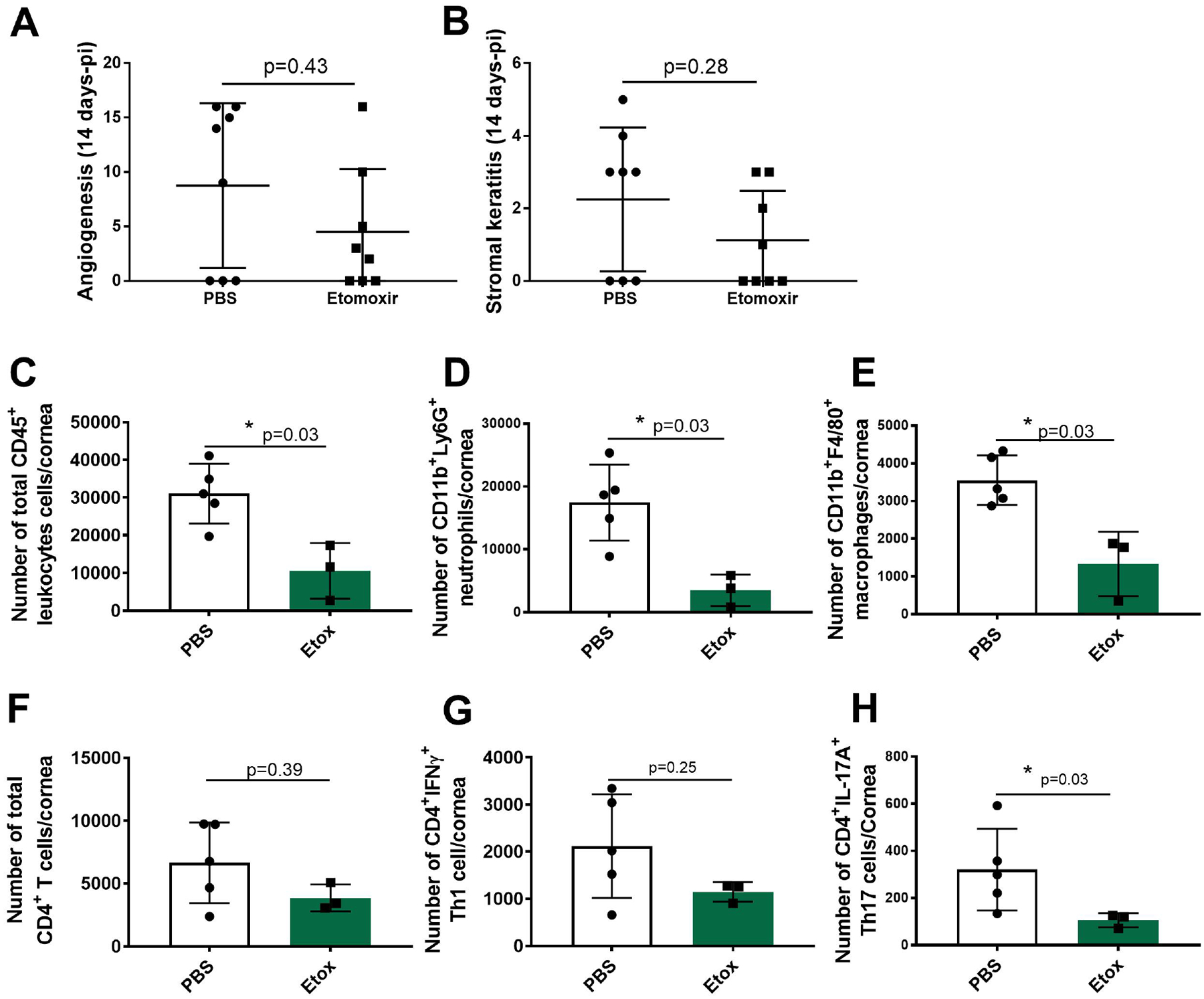

Experiments were performed where animals were ocularly infected with HSV and 6 days later either treated daily with Etox or given PBS and eyes recorded for signs of angiogenesis and SK. Three such experiments using 8 animals per group were performed and the results of one experiment is shown in Fig. 6A and B. In the control group, 5 of 8 eyes showed positive SK lesions and 4 of 8 Etox recipients. The average severity of SK lesions in animals with positive lesions was reduced by 2-fold by Etox therapy but this difference was not significant. On day 14, corneas were collected from all animals with positive lesions and the numbers of inflammatory cells present were identified and enumerated (Fig. 6C–H). The results shown in Fig. 6C indicate that Etox therapy reduced the total leucocytes (CD45) on average by 3-fold (*p=0.03) compared to PBS controls (Fig. 6C). Proinflammatory neutrophils were reduced in Etox recipients by 5-fold (*p=0.03) and macrophages by 2.6-fold (*p=0.03) compared to PBS controls (Fig. 6D and E, respectively). The effect of Etox therapy on T cell numbers was on average only 1.7-fold (Fig. 6F) and this difference was not significant (p=0.39). As shown in Fig. 6G, Etox reduced Th1 response by 1.8-fold (p=0.25). The most evident effect of Etox was to reduce the CD4 Th17 response (Fig. 6H). Here, the average reduction was 3-fold and did reach statistical significance (*p=0.03).

Fig. 6.

Therapeutic effects of Etox on ocular HSV disease severity and proinflammatory immune response in treated and untreated animals on day 14 pi. C57BL/6 mice (n=8) infected with HSV-1 RE (3×104PFU) and treated daily with Etox (15 mg/kg) starting from day 6 PI. Controls received PBS only (n=8). Fig. 6A shows angiogenesis and Fig. 6B shows SK. Studies were performed three times and data collected from two independent studies. Fig. 6C shows total leukocyte cell numbers (CD45). Fig. 6D shows neutrophil (CD45, CD11b, CDLy6G) cell numbers and Fig. 6E shows macrophage (CD45, CD11b, F4/80) cell numbers. One half of the cornea samples were stimulated with PMA/Iono for intracellular cytokine expression. Fig. 6F shows total CD4 T cell numbers. Fig. 6G shows Th1 (CD4, IFNγ) cell numbers and Fig. 6H shows Th17 (CD4, IL-17A) cell numbers. Studies were performed three times and data represent of two independent studies (n=5 for PBS, n=3 for Etox). To compare eye lesions and proinflammatory response in treated and untreated groups, Mann-Whitney test was performed with the mean SD. The level of significance as follows; *p<0.05. SSC-A.

4. Discussion

The present report evaluates a novel therapeutic approach to control the tissue-damaging consequences of ocular infection with HSV, a major cause of vision loss in humans [12]. As shown by numerous investigators [16, 17], the major damage to the cornea is the consequence of an inflammatory reaction to the infection composed of both innate and adaptive inflammatory cells with the latter orchestrating the lesions [18]. Such lesions can be controlled by rebalancing the participation of different cells in the reaction as we advocate can be achieved by exploiting metabolic differences between proinflammatory and regulatory cells involved in the responses [8]. In this report, we have evaluated the benefits of using the drug Etox, which acts by inhibiting the production of ATP generated by the FAO pathway that occurs in the mitochondrion [9]. This approach has not, to our knowledge, been evaluated previously as a means to control viral immunoinflammatory lesions, but has been used to counteract inflammatory lesions in some cancers and autoimmune diseases [10, 11]. Our results show that administering Etox from the onset of HSV ocular infection resulted in a marked reduction in corneal lesions with significantly reduced numbers of both innate cells and T cell responses, particularly Th17 T cells in the lesions. Notably, all Etox-treated recipients survived and showed no sign of encephalitis, as was the fate in several animals that received therapy with 2DG, as was also reported in a previous study [4]. The explanation for the different outcomes correlated with different effects of Etox and 2DG on inflammatory cells in the local TG. Thus, Etox had minimal effects on inflammatory T cells in the TG, whereas 2DG markedly reduced the T cell response, especially CD8 cells thought mainly involved at preventing HSV from spreading to the CNS [5]. We could also show that Etox therapy had minimal success to control lesions once they had already become manifest.

Using metabolic reprogramming to control inflammatory lesions caused by virus infections has so far received minimal evaluation. The common approach to control such reactions is to use anti-inflammatory drugs, particularly steroids, that often have problematic side effects [19]. In a previous study, we explored the use of 2DG to control ocular lesions set off by HSV infection and this was an effective therapy [4]. However, unacceptable consequences occurred in many animals that received 2DG when virus was still actively replicating in the eye. In several animals, virus disseminated to the CNS and animals developed encephalitis. The drug 2DG is known to act by inhibiting the high energy needs of inflammatory cells provided by glycolysis [2]. We chose to use Etox since this drug also inhibits energy metabolism, but targets a different metabolic pathway, namely FAO which occurs in mitochondria. We could show that when therapy was started early after infection, Etox was comparably effective to 2DG to suppress ocular angiogenesis and inflammatory lesions and did so without any animals developing any signs of encephalitis. It is well known that HSV, a virus that can spread to the CNS and cause encephalitis in both its natural host, mankind, but especially in related primates and experimentally infected rodents, which is usually fatal, if untreated [20].

The exact route by which virus disseminates to the brain is still debated, but our own previous studies with the model used in this report provided evidence that spread from the TG could be a major step in the pathogenesis [5]. We advocated that the inflammatory reaction in the TG, which always follows infection of the eye and face with HSV [21], may act to stop virus from passing up the nerve to the CNS. CD8 T cells are critical among the cell types that constrain viral spread [22], but it is likely that other cells are also involved that include CD4 effector cells as well as innate aspects of immunity [23–25]. We showed previously that 2DG was notably damaging to CD8 T cells, particularly those actively functioning by producing cytokines [5]. The present studies add support for those ideas and demonstrated that unlike 2DG, Etox had minimal effects on the TG T cell response and when inhibitory effects were detected these mainly involved the neutrophil and macrophage innate responses.

Whereas Etox would appear to be a more acceptable therapy than 2DG to control ocular herpetic lesion development if used early in the infection process, the therapy was usually ineffective once lesions were becoming evident. This was likely the case because actively developing SK lesions mainly involve CD4 Th1 cells [26] and Etox had limited inhibitory effects against such cells. In fact, the activity of Etox seemed most evident against innate inflammatory cells that are more relevant in early lesions [26]. Curiously, Etox did have significant inhibitory effects against Th17 cells, which are only a minor components in SK lesions, except late in the syndrome [27]. It is conceivable that in those autoimmune diseases such as multiple sclerosis [28] where Etox is an effective therapy such lesions are organized principally by Th17 cells [15].

Conceivably, controlling viral inflammatory lesions using metabolic reprogramming procedures might be a more effective approach if a combination of drugs was used, perhaps started each drug at different time during lesion development. To this end, we are exploring the outcome of early therapy with Etox followed by the later use of 2DG, with the hope of completely controlling SK lesion development. The concept of combining drugs to achieve better and less toxic therapy is a well- trodden path in pharmacology [29].

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health, United States grant R01EY005093.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of competing interest

There is no competing interest exist.

References

- [1].Pålsson-McDermott EM, O’Neill LAJ. Targeting immunometabolism as an anti-inflammatory strategy. Cell Res 2020;30:300–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].McGettrick AF, O’Neill LAJ. How metabolism generates signals during innate immunity and inflammation. J Biol Chem 2013;288:22893–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Zhang D, Li J, Wang F, Hu J, Wang S, Sun Y. 2-Deoxy-D-glucose targeting of glucose metabolism in cancer cells as a potential therapy. Cancer Lett 2014;355:176–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Varanasi SK, Donohoe D, Jaggi U, Rouse BT. Manipulating Glucose Metabolism during Different Stages of Viral Pathogenesis Can Have either Detrimental or Beneficial Effects. J Immunol 2017;199:1748–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Berber E, Sumbria D, Newkirk KM, Rouse BT. Inhibiting glucose metabolism results in herpes simplex encephalitis. J Immunol 2021;207:1824–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Sumbria D, Berber E, Mathayan M, Rouse BT. Virus infections and host metabolism—can we manage the interactions? Front immunol 2021;11:594963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Ayres JS. A metabolic handbook for the COVID-19 pandemic. Nat Metab 2020;2:572–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Sumbria D, Berber E, Rouse BT. Factors affecting the tissue damaging consequences of viral infections. Front Microbiol 2019;10:2314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Pike LS, Smift AL, Croteau NJ, Ferrick DA, Wu M. Inhibition of fatty acid oxidation by etomoxir impairs NADPH production and increases reactive oxygen species resulting in ATP depletion and cell death in human glioblastoma cells. Biochim Biophys Acta Bioenerg 2011;1807:726–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Mørkholt AS, Oklinski MK, Larsen A, Bockermann R, Issazadeh-Navikas S, Nieland JGK, et al. Pharmacological inhibition of carnitine palmitoyl transferase 1 inhibits and reverses experimental autoimmune encephalitis in rodents. PLoS One 2020;15:e0234493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Cheng S, Wang G, Wang Y, Cai L, Qian K, Ju L, et al. Fatty acid oxidation inhibitor etomoxir suppresses tumor progression and induces cell cycle arrest via PPARγ-mediated pathway in bladder cancer. Clin Sci 2019;133:1745–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Rouse BT, Schmid DS. Fraternal twins: The enigmatic role of the immune system in alphaherpesvirus pathogenesis and latency and its impacts on vaccine efficacy. Viruses 2022;14:862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Berber E, Rouse BT. Controlling herpes simplex virus-induced immunoinflammatory lesions using metabolic therapy: A comparison of 2-Deoxy-d-Glucose with metformin. Virol J 2022;96:e00688–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Jaggi U, Varanasi SK, Bhela S, Rouse BT. On the role of retinoic acid in virus induced inflammatory response in cornea. Microbes Infect 2018;20:337–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Shriver LP, Manchester M. Inhibition of fatty acid metabolism ameliorates disease activity in an animal model of multiple sclerosis. Sci Rep 2011;1:79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Streilein JW, Dana MR, Ksander BR. Immunity causing blindness: five different paths to herpes stromal keratitis. Immunol Today 1997;18:443–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Rowe AM, St. Leger AJ, Jeon S, Dhaliwal DK, Knickelbein JE, Hendricks RL. Herpes keratitis. Prog Retin Eye Res 2013;32:88–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Thomas J, Rouse BT. Immunopathogenesis of herpetic ocular disease. Immunol Res 1997;16:375–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].McGee S, Hirschmann J. Use of corticosteroids in treating infectious diseases. Arch Intern Med 2008;168:1034–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Whitley RJ, Gnann JW. Viral encephalitis: familiar infections and emerging pathogens. Lancet 2002;359:507–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Koyuncu Orkide O, Hogue Ian B, Enquist Lynn W. Virus infections in the nervous system. Cell Host Microbe 2013;13:379–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Liu T, Khanna KM, Chen X, Fink DJ, Hendricks RL. CD8+ T cells can block herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) reactivation from latency in sensory neurons. J Exp Med 2000;191:1459–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Kurt-Jones EA, Orzalli MH, Knipe DM. Innate immune mechanisms and herpes simplex virus infection and disease. Adv Anat Embryol Cell Biol 2017;223:49–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Herman M, Ciancanelli M, Ou Y-H, Lorenzo L, Klaudel-Dreszler M, Pauwels E, et al. Heterozygous TBK1 mutations impair TLR3 immunity and underlie herpes simplex encephalitis of childhood. J Exp Med 2012;209:1567–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Frank GM, Lepisto AJ, Freeman ML, Sheridan BS, Cherpes TL, Hendricks RL. Early CD4+T cell help prevents partial CD8+ Tcell exhaustion and promotes maintenance of herpes simplex virus 1 latency. J Immunol 2009;184:277–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Biswas PS, Rouse BT. Early events in HSV keratitis—setting the stage for a blinding disease. Microbes Infect 2005;7:799–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Suryawanshi A, Veiga-Parga T, Rajasagi NK, Reddy PBJ, Sehrawat S, Sharma S, et al. Role of IL-17 and Th17 Cells in Herpes Simplex Virus-Induced Corneal Immunopathology. J Immunol 2011;187:1919–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Jadidi-Niaragh F, Mirshafiey A. Th17 cell, the new player of neuroinflammatory process in multiple sclerosis. Scand J Immunol 2011;74:1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Yin Y, Choi S-C, Xu Z, Perry DJ, Seay H, Croker BP, et al. Normalization of CD4+ T cell metabolism reverses lupus. Sci Transl Med 2015;7:274ra18–ra18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]